Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Lipoprotein(a): Structure and Pathophysiology

3.2. Screening

3.3. Treatment Options

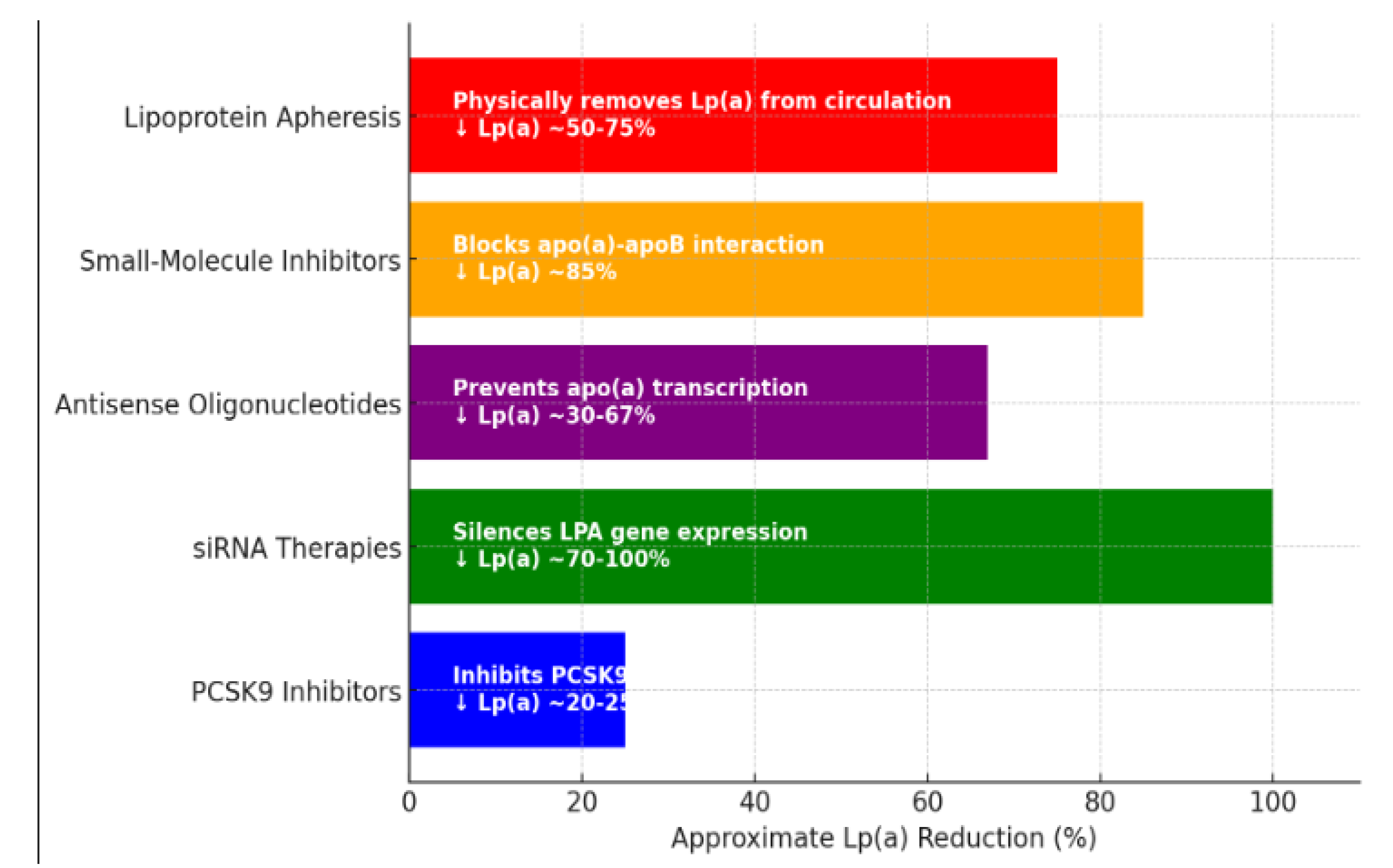

| Therapy | Mechanism of action | Reduction in Lp(a) | Duration of effect | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCSK9-i | Increase clearance via LDLR upregulation | 20-25% | short-term, frequent dosing | Moderate effect on Lp(a) reduction |

| ASOs (Pelacarsen) | Inhibits apo(a) mRNA translation | 29–67% | Long-term, monthly dosing | Not yet widely available |

| siRNA (Olpasiran) | Blocks apo(a) mRNA translation | 68.5–100% | Long-term, quarterly dosing | Not yet widely available |

| Apheresis | Physically removes Lp(a) from circulation | up to 73% | Immediate, but transient | Invasive, expensive |

| Small-molecule inhibitors (Muvalaplin) | Disrupts Lp(a) assembly | up to 85.8% | Oral, daily dosing | Early-stage development |

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nedkoff, L.; Briffa, T.; Zemedikun, D.; Herrington, S.; Wright, F.L. Global Trends in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Clinical Therapeutics 2023, 45, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyngbakken, M.N.; Myhre, P.L.; Røsjø, H.; Omland, T. Novel Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease: Applications in Clinical Practice. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 2019, 56, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geovanini, G.R.; Libby, P. Atherosclerosis and Inflammation: Overview and Updates. Clinical Science 2018, 132, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasdighi, E.; Adhikari, R.; Almaadawy, O.; Leucker, T.M.; Blaha, M.J. LP(a): Structure, Genetics, Associated Cardiovascular Risk, and Emerging Therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2024, 64, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | New England Journal of Medicine Available online:. Available online: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1801174 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Malick, W.A.; Goonewardena, S.N.; Koenig, W.; Rosenson, R.S. Clinical Trial Design for Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering Therapies: JACC Focus Seminar 2/3. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Wolski, K.; Cho, L.; Nicholls, S.J.; Kastelein, J.; Leitersdorf, E.; Landmesser, U.; Blaha, M.; Lincoff, A.M.; Morishita, R.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Levels in a Global Population with Established Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Open Heart 2022, 9, e002060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catapano, A.L.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Banach, M.; Gazzotti, M.; Olmastroni, E.; Casula, M.; Ray, K.K. ; Lipid Clinics Network Group Evaluation of Lipoprotein(a) in the Prevention and Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Survey among the Lipid Clinics Network. Atherosclerosis 2023, 370, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, M.B. Beyond Fibrinolysis: The Confounding Role of Lp(a) in Thrombosis. Atherosclerosis 2022, 349, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.; Watts, G.F.; Schneider, W.J.; Tsimikas, S.; Kovanen, P.T. Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Elevated Lipoprotein(a): Double Heritable Risk and New Therapeutic Opportunities. J Intern Med 2020, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Lau, F.; Giugliano, R.P. Lipoprotein(a) and Its Significance in Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. JAMA Cardiology 2022, 7, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, F.; Mora, S.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Ference, B.A.; Arsenault, B.J.; Berglund, L.; Dweck, M.R.; Koschinsky, M.; Lambert, G.; Mach, F.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and Aortic Stenosis: A European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Statement. Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 3925–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipoprotein(a) as a Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Diseases: Pathophysiology and Treatment Perspectives Available online:. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/18/6721 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Kronenberg, F. Lipoprotein(a). In Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerosis: Improving State-of-the-Art Management and Search for Novel Targets; von Eckardstein, A., Binder, C.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham (CH), 2022 ISBN 978-3-030-86075-2.

- Coassin, S.; Kronenberg, F. Lipoprotein(a) beyond the Kringle IV Repeat Polymorphism: The Complexity of Genetic Variation in the LPA Gene. Atherosclerosis 2022, 349, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enkhmaa, B.; Anuurad, E.; Berglund, L. Lipoprotein (a): Impact by Ethnicity and Environmental and Medical Conditions. J Lipid Res 2016, 57, 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, K.; Mahmoud, A.K.; Abbas, M.T.; Alsidawi, S.; Ayoub, C.; Arsanjani, R.; Farina, J.M. Intra-Individual Variability in Lipoprotein(a) Levels: Findings from a Large Academic Health System Population. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2024, zwae341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, B.G.; Langsted, A. Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Disease. The Lancet 2024, 404, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsó, E.; Schmitz, G. Lipoprotein(a) and Its Role in Inflammation, Atherosclerosis and Malignancies. Clin Res Cardiol Suppl 2017, 12, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labudovic, D.; Kostovska, I.; Tosheska Trajkovska, K.; Cekovska, S.; Brezovska Kavrakova, J.; Topuzovska, S. Lipoprotein(a) - Link between Atherogenesis and Thrombosis. Prague Med Rep 2019, 120, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugovšek, S.; Šebeštjen, M. Lipoprotein(a)—The Crossroads of Atherosclerosis, Atherothrombosis and Inflammation. Biomolecules 2021, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enas, E.A.; Varkey, B.; Dharmarajan, T.S.; Pare, G.; Bahl, V.K. Lipoprotein(a): An Independent, Genetic, and Causal Factor for Cardiovascular Disease and Acute Myocardial Infarction. Indian Heart J 2019, 71, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.-L.; Yuan, H.-H.; Xie, L.-L.; Guo, M.-H.; Liao, D.-F.; Zheng, X.-L. New Dawn for Atherosclerosis: Vascular Endothelial Cell Senescence and Death. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdin, C.A.; Khera, A.V.; Natarajan, P.; Klarin, D.; Won, H.-H.; Peloso, G.M.; Stitziel, N.O.; Nomura, A.; Zekavat, S.M.; Bick, A.G.; et al. Phenotypic Characterization of Genetically Lowered Human Lipoprotein(a) Levels. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 68, 2761–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamstrup, P.R.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Elevated Lipoprotein(a) Levels, LPA Risk Genotypes, and Increased Risk of Heart Failure in the General Population. JACC: Heart Failure 2016, 4, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, C.M.; Kamstrup, P.R.; Langsted, A.; Varbo, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering by 50 Mg/dL (105 Nmol/L) May Be Needed to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease 20% in Secondary Prevention. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2020, 40, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurmohamed, N.S.; Moriarty, P.M.; Stroes, E.S. Considerations for Routinely Testing for High Lipoprotein(a). Current Opinion in Lipidology 2023, 34, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willeit, P.; Ridker, P.M.; Nestel, P.J.; Simes, J.; Tonkin, A.M.; Pedersen, T.R.; Schwartz, G.G.; Olsson, A.G.; Colhoun, H.M.; Kronenberg, F.; et al. Baseline and On-Statin Treatment Lipoprotein(a) Levels for Prediction of Cardiovascular Events: Individual Patient-Data Meta-Analysis of Statin Outcome Trials. Lancet 2018, 392, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minelli, S.; Minelli, P.; Montinari, M.R. Reflections on Atherosclerosis: Lesson from the Past and Future Research Directions. J Multidiscip Healthc 2020, 13, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, S.; Tan, J.; Wei, L.; Wu, D.; Gao, S.; Weng, Y.; Chen, J. Recent Advance in Treatment of Atherosclerosis: Key Targets and Plaque-Positioned Delivery Strategies. J Tissue Eng 2022, 13, 20417314221088509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirillo, A.; Bonacina, F.; Norata, G.D.; Catapano, A.L. The Interplay of Lipids, Lipoproteins, and Immunity in Atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Leyte, D.J.; Zepeda-García, O.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; González-Garrido, A.; Villarreal-Molina, T.; Jacobo-Albavera, L. Endothelial Dysfunction, Inflammation and Coronary Artery Disease: Potential Biomarkers and Promising Therapeutical Approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Glynn, R.J.; Bradwin, G.; Hasan, A.A.; Rifai, N. Comparison of Interleukin-6, C-Reactive Protein, and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol as Biomarkers of Residual Risk in Contemporary Practice: Secondary Analyses from the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 2952–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljubasic, N.; Akkerhuis, K.M.; Cheng, J.M.; Oemrawsingh, R.M.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; de Boer, S.P.M.; Regar, E.; van Geuns, R.-J.M.; Serruys, P.W.J.C.; Boersma, E.; et al. Fibrinogen in Relation to Degree and Composition of Coronary Plaque on Intravascular Ultrasound in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography. Coronary Artery Disease 2017, 28, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.; Lu, Q.; Zhu, W.-J.; Wang, T.-Z.; Du, Y.; Bai, L. Correlations of Degree of Coronary Artery Stenosis with Blood Lipid, CRP, Hcy, GGT, SCD36 and Fibrinogen Levels in Elderly Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 9582–9589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shridas, P.; Tannock, L.R. Role of Serum Amyloid A in Atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 2019, 30, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inflammatory Cytokines and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: New Prospective Study and Updated Meta-Analysis - PMC Available online:. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3938862/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- A Comprehensive 1000 Genomes-Based Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis of Coronary Artery Disease - PMC Available online:. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4589895/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Holmes, M.V.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Palmer, T.M.; Drenos, F.; Lanktree, M.B.; Nelson, C.P.; Dale, C.E.; Padmanabhan, S.; Finan, C.; Swerdlow, D.I.; et al. Mendelian Randomization of Blood Lipids for Coronary Heart Disease. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.G.; Ference, B.A.; Im, K.; Wiviott, S.D.; Giugliano, R.P.; Grundy, S.M.; Braunwald, E.; Sabatine, M.S. Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration Efficacy and Safety of More Intensive Lowering of LDL Cholesterol: A Meta-Analysis of Data from 170 000 Participants in 26 Randomised Trials. Lancet 2010, 376, 1670–1681. [CrossRef]

- Marcovina, S.M.; Koschinsky, M.L.; Albers, J.J.; Skarlatos, S. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop on Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Disease: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Clinical Chemistry 2003, 49, 1785–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcovina, S.M.; Albers, J.J.; Scanu, A.M.; Kennedy, H.; Giaculli, F.; Berg, K.; Couderc, R.; Dati, F.; Rifai, N.; Sakurabayashi, I.; et al. Use of a Reference Material Proposed by the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine to Evaluate Analytical Methods for the Determination of Plasma Lipoprotein(a). Clin Chem 2000, 46, 1956–1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lampsas, S.; Xenou, M.; Oikonomou, E.; Pantelidis, P.; Lysandrou, A.; Sarantos, S.; Goliopoulou, A.; Kalogeras, K.; Tsigkou, V.; Kalpis, A.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) in Atherosclerotic Diseases: From Pathophysiology to Diagnosis and Treatment. Molecules 2023, 28, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegla, J.; France, M.; Marcovina, S.M.; Neely, R.D.G. Lp(a): When and How to Measure It. Ann Clin Biochem 2021, 58, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borque, L.; Rus, A.; del Cura, J.; Maside, C.; Escanero, J. Automated Latex Nephelometric Immunoassay for the Measurement of Serum Lipoprotein (a). J Clin Lab Anal 1993, 7, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari, M.; Rezayi, M.; Ruscica, M.; Jpamialahamdi, T.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. The Ins and Outs of Lipoprotein(a) Assay Methods. Arch Med Sci Atheroscler Dis 2023, 8, e128–e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szarek, M.; Reijnders, E.; Jukema, J.W.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Diaz, R.; Fazio, S.; Garon, G.; Goodman, S.G.; Harrington, R.A.; et al. Relating Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations to Cardiovascular Event Risk After Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Comparison of 3 Tests. Circulation 2024, 149, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamstrup, P.R. Lipoprotein(a) and Cardiovascular Disease. Clinical Chemistry 2021, 67, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjehan, R.D.; Sharma, S.; Bhutta, B.S. Coronary Artery Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Rosenson, R.S.; Gencer, B.; López, J.A.G.; Lepor, N.E.; Baum, S.J.; Stout, E.; Gaudet, D.; Knusel, B.; Kuder, J.F.; et al. Small Interfering RNA to Reduce Lipoprotein(a) in Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.C.; Watts, G.F. The Promise of PCSK9 and Lipoprotein(a) as Targets for Gene Silencing Therapies. Clin Ther 2023, 45, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: Lipid Modification to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk | European Heart Journal | Oxford Academic Available online:. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/1/111/5556353 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Lampsas, S.; Xenou, M.; Oikonomou, E.; Pantelidis, P.; Lysandrou, A.; Sarantos, S.; Goliopoulou, A.; Kalogeras, K.; Tsigkou, V.; Kalpis, A.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) in Atherosclerotic Diseases: From Pathophysiology to Diagnosis and Treatment. Molecules 2023, 28, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, S.; Ž, R.; Le, S.-M.; G, F.; Af, C. Effect of Extended-Release Niacin on Plasma Lipoprotein(a) Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. Metabolism: clinical and experimental 2016, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Ballantyne, C.M. Existing and Emerging Strategies to Lower Lipoprotein(a). Atherosclerosis 2022, 349, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaban, G. Statins and Lipoprotein(a); Facing the Residual Risk. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2022, 29, 777–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, L.M.; Oorthuys, A.O.J.; Wiegman, A.; Langendam, M.W.; Kroon, J.; Spijker, R.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Hutten, B.A. Statin Therapy and Lipoprotein(a) Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2022, 29, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safarova, M.S.; Moriarty, P.M. Lipoprotein Apheresis: Current Recommendations for Treating Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Elevated Lipoprotein(a). Curr Atheroscler Rep 2023, 25, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Víšek, J.; Bláha, M.; Bláha, V.; Lášticová, M.; Lánska, M.; Andrýs, C.; Tebbens, J.D.; Igreja e Sá, I.C.; Tripská, K.; Vicen, M.; et al. Monitoring of up to 15 Years Effects of Lipoprotein Apheresis on Lipids, Biomarkers of Inflammation, and Soluble Endoglin in Familial Hypercholesterolemia Patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2021, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, A.; Connelly-Smith, L.; Aqui, N.; Balogun, R.A.; Klingel, R.; Meyer, E.; Pham, H.P.; Schneiderman, J.; Witt, V.; Wu, Y.; et al. Guidelines on the Use of Therapeutic Apheresis in Clinical Practice - Evidence-Based Approach from the Writing Committee of the American Society for Apheresis: The Eighth Special Issue. J Clin Apher 2019, 34, 171–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, G.R. The Scientific Basis and Future of Lipoprotein Apheresis. Ther Apher Dial 2022, 26, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, A.K.; Gray, J.V.; Gorby, L.K.; Moriarty, P.M. Lipoprotein Apheresis: First FDA Indicated Treatment for Elevated Lipoprotein(a). J Clin Cardiol 2020, Volume 1, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, T.S.; Karsten, V.; Chan, A.; Chiesa, J.; Boyce, M.; Bettencourt, B.R.; Hutabarat, R.; Nochur, S.; Vaishnaw, A.; Gollob, J. Clinical Proof of Concept for a Novel Hepatocyte-Targeting GalNAc-siRNA Conjugate. Mol Ther 2017, 25, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, C.; Sirtori, C.R.; Corsini, A.; Santos, R.D.; Watts, G.F.; Ruscica, M. A New Dawn for Managing Dyslipidemias: The Era of Rna-Based Therapies. Pharmacol Res 2019, 150, 104413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Poller, W.; Tsimikas, S.; Most, P.; Paneni, F.; Lüscher, T.F. From Traditional Pharmacological towards Nucleic Acid-Based Therapies for Cardiovascular Diseases. European Heart Journal 2020, 41, 3884–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzmann, J.L.; Packard, C.J.; Chapman, M.J.; Katzmann, I.; Laufs, U. Targeting RNA With Antisense Oligonucleotides and Small Interfering RNA: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeang, C.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Su, F.; Dinh, B.; Xia, S.; Witztum, J.L.; Tsimikas, S. Effect of Pelacarsen on Lipoprotein(a) Cholesterol and Corrected Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals A Randomized Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Trial Assessing the Impact of Lipoprotein (a) Lowering With Pelacarsen (TQJ230) on Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Established Cardiovascular Disease; clinicaltrials. 2025.

- Katsiki, N.; Vrablik, M.; Banach, M.; Gouni-Berthold, I. Inclisiran, Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Lipoprotein (a). Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Wasserman, S.M.; et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Rosenson, R.S.; Gencer, B.; López, J.A.G.; Lepor, N.E.; Baum, S.J.; Stout, E.; Gaudet, D.; Knusel, B.; Kuder, J.F.; et al. Small Interfering RNA to Reduce Lipoprotein(a) in Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eli Lilly and Company A Phase 2, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Investigate the Efficacy and Safety of LY3819469 in Adults With Elevated Lipoprotein(a); clinicaltrials. 2025.

- Nissen, S.E.; Linnebjerg, H.; Shen, X.; Wolski, K.; Ma, X.; Lim, S.; Michael, L.F.; Ruotolo, G.; Gribble, G.; Navar, A.M.; et al. Lepodisiran, an Extended-Duration Short Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a). JAMA 2023, 330, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, A.J.; Fernando, P.M.S.; Burnett, J.R. Potential of Muvalaplin as a Lipoprotein(a) Inhibitor. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2024, 33, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Ni, W.; Rhodes, G.M.; Nissen, S.E.; Navar, A.M.; Michael, L.F.; Haupt, A.; Krege, J.H. Oral Muvalaplin for Lowering of Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCORE2-OP Risk Prediction Algorithms: Estimating Incident Cardiovascular Event Risk in Older Persons in Four Geographical Risk Regions. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 2455–2467. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).