1. Introduction

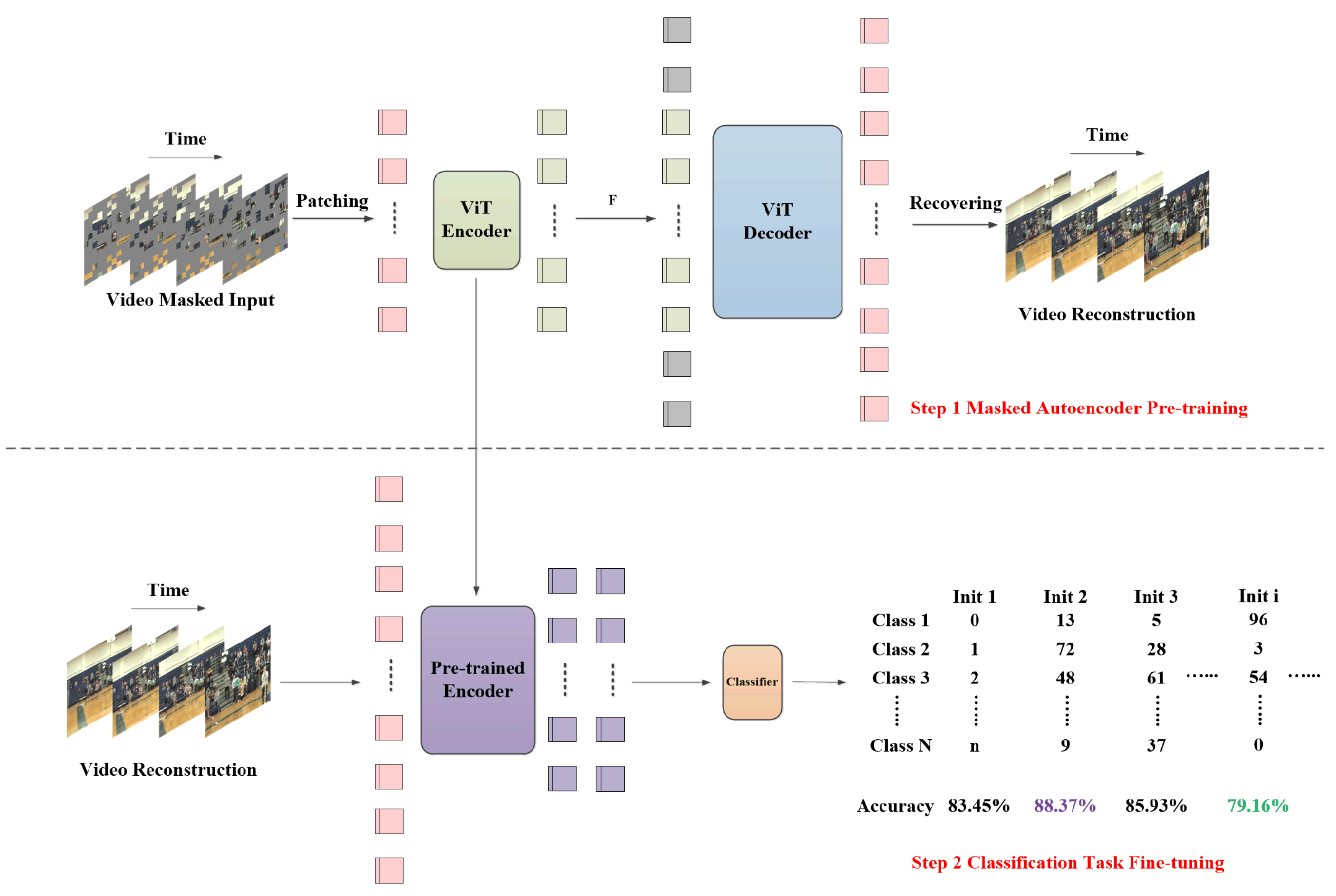

In the past few months, we have observed some intriguing phenomena while applying visual masked self-supervised pre-trained models, including ImageMAE [

1], VideoMAE [

2], MAE-ST [

3], and MultiMAE [

4], to various downstream classification tasks. When performing downstream classification tasks using the same dataset allocation strategy, we found that different randomly initialized unique encoding of classification labels led to significant variations in results when the pre-trained models were trained with fully supervised fine-tuning, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

In other words, during each fine-tuning process, we strictly maintained the downstream dataset partitioning strategy and the initial parameters of the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model unchanged. The only variable was the method of randomly initializing the unique position encoding of the classification labels in the downstream task. Surprisingly, we found that despite the consistency of input data and pre-trained weight parameters, different random initializations of label position encoding led to significantly different fine-tuned outcomes. In some experiments, the final performance deviation of the fine-tuned models reached as high as 10%. This phenomenon suggests that the unique encoding of classification labels plays a crucial role during fine-tuning and may profoundly impact the model’s optimization trajectory, gradient distribution, and even its final generalization ability. Therefore, we hypothesize that the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model might have an inherent preference for certain label encoding or positional arrangements. This study aims to explore the underlying nature of this phenomenon and analyze its potential impact on model fine-tuning optimization, with the goal of providing new theoretical insights and practical guidance for downstream applications of self-supervised learning.

To address these challenges, various solutions have been proposed across different domains to mitigate the impact of label randomness on model optimization. In the field of natural language processing, researchers have introduced semantic-aware label embeddings [

5] to overcome the limitations of traditional one-hot encoding, which ignores semantic relationships between categories. This approach provides continuous, semantically relevant representations for class labels, thereby reducing the influence of label randomness on the optimization trajectory. However, its effectiveness relies on the presence of semantic associations among categories. For completely unrelated classes, its impact may be limited. Particularly in computer vision tasks, where semantic relationships between different categories are far less pronounced than in textual tasks, the advantages of semantic-aware label embeddings may not be fully realized. Additionally, some researchers have employed consistency regularization [

6] and class-invariance constraints [

7], leveraging adversarial or contrastive learning strategies to introduce perturbations to the label encoding during training. These approaches enable the model to become invariant to encode randomness, thereby enhancing robustness. However, they also significantly increase computational costs, potentially limiting their applicability in large-scale tasks.

Therefore, we compared the results of training the Vanilla Vision Transformer (ViT) [

8] from scratch with fine-tuning visual masked self-supervised pre-trained models, such as ImageMAE [

1] and VideoMAE [

2]. We explored the potential inherent preference of the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model for label position or encoding methods during downstream classification fine-tuning. To address this, we proposed a classification label position ranking algorithm, Label Ranker. It is based on unsupervised feature clustering using Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [

9] and Euclidean distance. This approach aims to reduce instability caused by random label initialization, thereby enhancing the robustness of fine-tuning across different label position encoding methods. Through experiments on CIFAR-100 [

10], UCF101 [

11], and HMDB51 [

12], we validated the effectiveness of Label Ranker in stabilizing label position encoding and improving fine-tuned performance for the visual self-supervised model. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

Revealing inherent preferences of the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model for classification label position encoding methods, providing new research directions for future fine-tuning strategies.

Proposing a computationally efficient unsupervised label position ranking method, offering a novel optimization strategy for downstream transfer in self-supervised learning.

Advancing stability research in self-supervised learning for downstream tasks, providing theoretical support and practical guidelines for more efficient and robust fine-tuning methods.

Conducting extensive experiments on ImageMAE [

1] and VideoMAE [

2] pre-trained models, covering CIFAR-100 [

10], UCF101 [

11], and HMDB51 [

12] public datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method in stabilizing label position encoding and improving fine-tuned performance for visual self-supervised models.

2. Related Work

2.1. Self-Supervised Learning

In recent years, self-supervised learning [

13] has achieved remarkable progress in computer vision tasks. The core idea is to pre-training the model on unlabeled data to learn general feature representations, which can then be fine-tuned with a small amount of labeled data to enhance performance on downstream tasks. In particular, visual masked self-supervised pre-trained models (e.g., ImageMAE [

1] and VideoMAE [

2]) leverage the masked reconstruction task to learn both global and local features. After pre-training on large-scale unlabeled datasets, these models exhibit superior generalization capabilities in tasks such as image and video classification. When transferring to downstream classification tasks, fully supervised fine-tuning is usually adopted, that is, where the pre-trained model is optimized using labeled data.

However, despite keeping the pre-trained model’s initial weights unchanged, the different position encoding schemes of classification label can still influence the final fine-tuned results. Previous studies [

5] have indicated that the representation of label position can impact the optimization trajectory, thereby affecting the model’s final performance. Nonetheless, most current research in self-supervised learning [

13] primarily focuses on improving the pre-training phase, with relatively little attention given to how label encoding impacts fine-tuning. This gap presents a new research direction that our study aims to explore.

2.2. Label Position Encoding

During the training of deep neural networks, classification labels are typically represented using one-hot encoding, where each class is assigned a unique fixed index. Although one-hot encoding itself does not explicitly encode relationships between categories, its assigned order may influence the optimization process and final model performance to some extent. Previous studies [

7] have shown that in classification tasks, the ranking of label position can affect the gradient propagation path, thereby impacting optimization convergence and stability. This effect may be even more pronounced when visual masked self-supervised pre-trained models (e.g., ImageMAE [

1] and VideoMAE [

2]) are transferred to downstream tasks. Since the feature representations learned by the self-supervised model are not explicitly tied to fixed classification labels, the initialization encoding method of classification label position during fine-tuning may influence the optimization trajectory differently, potentially leading to significant performance fluctuations. For instance, when fine-tuning on the same dataset with different one-hot encoding orders, the final classification accuracy can vary by more than 10%, suggesting that the model may have an inherent preference for label position ranking. However, current research primarily focuses on model architectures and optimization algorithms, with limited systematic exploration of how label position encoding affects model transferability.

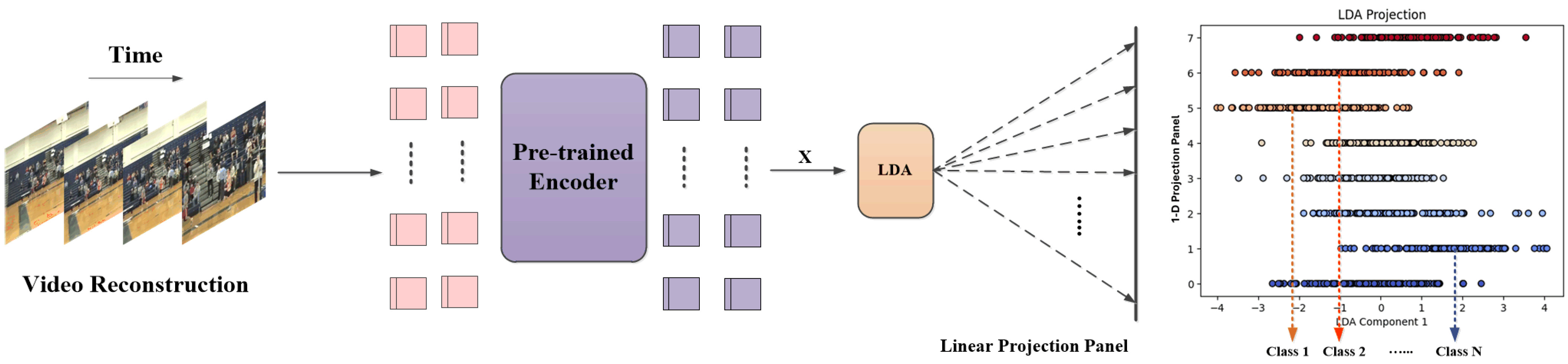

Figure 2.

Label Ranker Processing: LDA [

9] is used to reduce the dimension of features into 1-D and map them to the linear projection panel.

Figure 2.

Label Ranker Processing: LDA [

9] is used to reduce the dimension of features into 1-D and map them to the linear projection panel.

2.3. Linear Discriminant Analysis

LDA [

9] is a classic dimensionality reduction and classification method widely used in pattern recognition, data analysis, and feature extraction tasks. The core idea is to maximize between-class variance while minimizing within-class variance to learn an optimal projection direction, thereby enhancing the separability between different classes. In many computer vision tasks, LDA [

9] has been employed for dimensionality reduction, feature extraction, and data visualization, improving the model’s understanding of class distributions. In this study, we leverage LDA [

9] for 1-D feature clustering and propose a novel label ranking method to mitigate the impact of randomly initialized label position encoding on the optimization trajectory during fine-tuning. Since the self-supervised pre-trained model may exhibit an inherent preference for certain label position arrangements when fine-tuned on downstream tasks, traditional one-hot encoding can lead to significant performance fluctuations when the same dataset is fine-tuned under different experimental label position settings. To stabilize label position encoding, we project data features using LDA [

9] and calculate the similarity of categories based on Euclidean distance. This enables a more structured label ranking, ensuring that similar classes are positioned closer together in the encoding space.

3. METHOD

3.1. Problem Definition

In both supervised learning and self-supervised learning fine-tuning stages, classification tasks typically represent class labels using one-hot encoding. For a dataset with

N classes, each class

y is encoded as the

N-dimensional one-hot vector

where the

y-th position is set to 1, while all other positions are 0:

Where 1 appears only at the index corresponding to class y.

However, during actual training, the index positions of class labels are not fixed but are randomly assigned at the beginning of each experiment. For example, for the same training dataset, class A may be encoded as in one training session but as in another. This phenomenon, known as Label Assignment Randomization, means that across different experiments, the label index position assigned to the same class may vary, leading to changes in label encoding order.

While different label assignments do not alter the actual data distribution, they may impact the optimization process during deep neural network training. Since the model learns mapping relationship between features and labels through gradient-based optimization, variations in label assignment may lead to changes in optimization trajectories, differences in model parameter convergence, and fluctuations in model performance.

3.2. LDA Projection

To effectively address the instability issues brought by label assignment randomization during model fine-tuning, this study proposes a classification label position ranking method based on LDA [

9], Label Ranker. This method leverages the dimensionality reduction and class discriminative capabilities of LDA [

9] to achieve reasonable label ordering through 1-D feature clustering, optimizing label position encoding and reducing the impact of random label initialization on the optimization trajectory and model performance. As shown in

Figure 2, the input data is transformed into

feature tokens

X using the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model. The LDA [

9] algorithm is then employed to reduce the dimensionality of the feature map onto the linear projection plane, forming 1-D data feature points

for each class.

The main steps of LDA [

9] involve calculating the within-class scatter matrix

and the between-class scatter matrix

, as well as determining the optimal projection matrix

w that maximizes class separability. The mathematical expressions for these calculations are as follows:

Where

N is the total number of classes,

represents the feature sample set of the

i-th class,

x is the feature point belonging to class

,

is the mean feature vector of the

i-th class,

is the global mean feature vector, and

is the number of feature samples in class

.

|

Algorithm 1:Label Ranker Algorithm |

|

Input: X

Parameter: N

Output: Y

- 1:

Calculate the within-class scatter matrix

- 2:

Calculate the between-class scatter matrix

- 3:

Solve for the optimal projection matrix w

- 4:

Project to the optimal direction

- 5:

Select minimum feature mean class as

- 6:

while do

- 7:

Calculate the Euclidean distance

- 8:

end while - 9:

Label position similarity ranking Y

- 10:

returnY

|

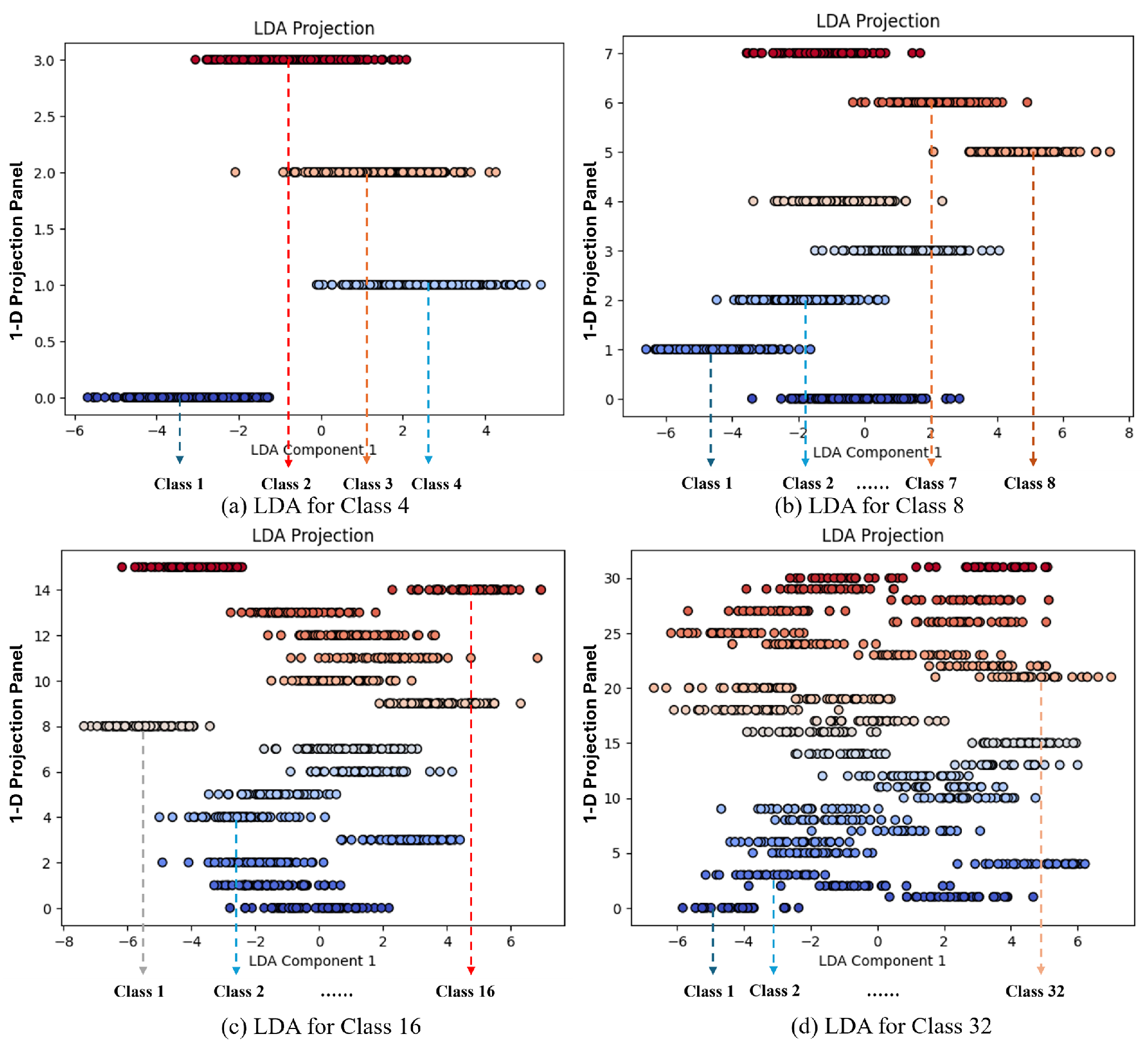

3.3. Similarity Ranking

In this study, the Euclidean distance

is used to measure the similarity between different categories and serves as the basis for label position ranking. By computing the feature representations of categories after LDA [

9] projection, we quantify the similarity between each class using the Euclidean distance. Specifically, we calculate the Euclidean distance between the projected feature vectors of each class, where more similar classes should exhibit smaller distances in the label space. Based on the computed class similarities, we adopt an unsupervised sorting method to reorder the label position according to their similarity scores, denoted as

Y. Through this structured ranking, the label assignment becomes more systematic and stable, ensuring that similar classes are assigned to adjacent positions. This approach mitigates the instability introduced by random label position initialization, enhancing the robustness of fine-tuning. The Label Ranker procedure is outlined in Algorithm 1.

Finally, the Euclidean distance is employed to measure the distance between different class feature vectors in the LDA [

9] projected space. The higher the similarity between two classes, the smaller the Euclidean distance between their feature vectors; conversely, the greater the difference between classes, the larger the Euclidean distance. Based on the calculated Euclidean distance

, the class similarity ranking yields

Y. Classes with smaller distances are considered more similar in the LDA [

9] space and are therefore assigned closer positions in the label encoding space. Following the similarity ranking, label positions are sorted in ascending order based on Euclidean distance, as illustrated in

Figure 3. Consequently, labels of similar classes are assigned adjacent positions, while dissimilar classes are placed further apart. The mathematical formulation for similarity calculation is as follows:

Where,

and

are the feature vectors of the classes

and

in the LDA [

9] space, and

m is the dimension in the LDA [

9] space, that is, the number of samples in each class.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. CIFAR-100 [10]

It is a widely used image classification dataset, playing a significant role in image classification, feature extraction, and deep learning model evaluation, particularly in the field of computer vision. Released by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), this dataset consists of 100 distinct classes, making it suitable for various vision tasks such as image classification and object recognition. The dataset contains 60,000 color images with a resolution of 32×32 pixels, which are evenly distributed across 100 classes. Each class includes 600 images, with the dataset being split into 50,000 training images and 10,000 test images.

Figure 3.

Classification Label Sequence. Calculate the centroid and Euclidean distance of various one-dimensional feature points for position ranking.

Figure 3.

Classification Label Sequence. Calculate the centroid and Euclidean distance of various one-dimensional feature points for position ranking.

4.1.2. UCF101 [11]

It is a video dataset widely used for action recognition tasks, released by the University of Central Florida. It comprises 101 distinct action classes, covering a diverse range of daily activities such as sports, dancing, and social interactions. As a benchmark dataset in action recognition, UCF101 [

11] is extensively utilized for evaluating video analysis, feature learning, and deep learning models. The dataset consists of 13,320 video clips, categorized into 101 different action classes. Each class contains multiple video clips, which are divided into training and testing sets. The duration of each video clip typically ranges from a few seconds to several minutes. The videos are provided at a resolution of 320×240 pixels with a fixed frame rate of 25 Frames Per Second (FPS).

4.1.3. HMDB51 [12]

It is a widely used video dataset for human action recognition research, released by Brown University of Providence. It comprises 51 action classes, encompassing a diverse range of daily activities and complex motion types. The extensive use of the HMDB51 [

12] dataset has significantly contributed to advancements in video understanding, action recognition, and computer vision. Notably, it serves as a benchmark dataset for evaluating video classification models, particularly in deep learning and self-supervised learning research. The dataset consists of 6,766 video clips, categorized into 51 distinct action classes, with each class containing approximately 100 video clips. The dataset is split into training and testing sets. The videos are provided at a resolution of 320×240 pixels, with a typical frame rate of 30 FPS. The duration of each video clip ranges from a few seconds to several tens of seconds. The video clips originate from various public sources, including movies, TV shows, YouTube videos, and other online platforms.

4.2. Implementation Details

4.2.1. Pre-Training

In this experiment, we fine-tuned the pre-trained models based on ImageMAE-Base-ImageNet-1k [

1] and VideoMAE-Base-K400 [

2], which were pre-trained using masked visual self-supervised learning on the ImageNet-1k [

14] and Kinetics 400 [

15] datasets. ImageNet-1k [

14] is a large-scale image dataset containing 1,000 object classes, while Kinetics 400 [

15] is a large-scale video dataset covering 400 human action classes. These datasets encompass a diverse range of real-world object classes and human activities, making them widely used for vision tasks such as semantic segmentation, video understanding, and action recognition. ImageMAE [

1] and VideoMAE [

2], as visual masked self-supervised pre-training methods, enable models to learn effective representations from unlabeled data, making them well-suited for fine-tuning in downstream tasks.

4.2.2. Fine-Tuning

During the fine-tuning phase, we conducted downstream classification tasks on the CIFAR-100 [

10], UCF101 [

11], and HMDB51 [

12] datasets. The fine-tuning process was performed using Google’s V2-8 TPU with high memory configuration, with the batch size of 64 and the initial learning rate of 5e-4. The learning rate schedule followed a combination of Warm-Up and Cosine Annealing [

16], where the total number of training epochs was 100, and the Warm-Up phase lasted for 5 epochs. We utilized the AdamW [

17] optimizer with the weight decay of 0.05. The loss function employed was Sparse Categorical Crossentropy, and the evaluation metric used was Sparse Categorical Accuracy.

4.2.3. Algorithm Strategy

The objective of this experiment is to investigate the impact of random label position initialization on fine-tuning results and to validate whether our proposed classification label position ranking method, based on the unsupervised feature clustering using LDA [

9] and Euclidean distance, can effectively mitigate the influence of label randomness on the optimization path, thereby enhancing the stability and performance of fine-tuning. By comparing the results of the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model trained from scratch and fine-tuned visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model, we aim to analyze the potential effect of label position order on the fine-tuning performance of the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model and evaluate whether our proposed Label Ranker method can effectively address this issue.

Table 1.

Compare the results of the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model trained from scratch and the ImageMAE [

1] pre-trained model fine-tuned on CIFAR-100 [

10].

Table 1.

Compare the results of the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model trained from scratch and the ImageMAE [

1] pre-trained model fine-tuned on CIFAR-100 [

10].

| Model |

from scratch |

Pre-trained Data |

Label State |

Accuracy |

| Vanilla ViT-B [8] |

✓ |

− |

Sequence |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| Avg. |

− |

− |

− |

|

| ImageMAE [1] |

× |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Sequence |

|

| × |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Random |

|

| × |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Random |

|

| × |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Random |

|

| × |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Random |

|

| × |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Random |

|

| × |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Random |

|

| × |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Random |

|

| Avg. |

− |

− |

− |

|

| |

× |

ImageNet-1k [14] |

Label Ranker |

|

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Ablation Study

In this experiment, as presented in Table 1, we compared the results of training the Vanilla ViT [

8] model from scratch with the fine-tuning results of the ImageMAE [

1] pre-trained model on the CIFAR-100 [

10] dataset to evaluate the impact of label position initialization randomness on fine-tuning performance. We conducted one experiment with letter sequential label position and seven experiments with random label position, testing the model’s performance under different initialization label position conditions. The performance of the ImageMAE [

1] model during fine-tuning was found to be unstable after pre-trained. Specifically, under the conditions of pre-training on the ImageNet-1K [

14] dataset, we observed that label position random initialization significantly affected the fine-tuning outcomes. For instance, in these eight trials, the accuracy of the ImageMAE [

1] model fluctuated between 78.35% and 91.59%, indicating that random label position initialization has a substantial impact on the optimization trajectory and final performance. Different random initializations may lead the model to converge to different local optima, resulting in considerable variations in fine-tuned outcomes.

In contrast, the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model demonstrated more stable performance when training from scratch. The Vanilla ViT-B [

8] without pre-training maintained a stable average performance around 50.24% on CIFAR-100 [

10]. The accuracy fluctuated between 50.22% and 50.25% across the eight random trials. To mitigate the self-awareness preference introduced by the ImageMAE [

1] pre-trained model, we employed our proposed label position ranking scheme to preferentially order the label position, resulting in a higher and more stable fine-tuning outcome of 90.82%. This result exceeds the average accuracy 84.88% of the random label position trials by 5.94%, demonstrating that the proposed method effectively mitigates the substantial fluctuations in fine-tuning results of the pre-trained model.

Tables 2 and 3 present the results of training the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] from scratch and fine-tuning VideoMAE [

2] pre-trained model on the UCF101 [

11] and HMDB51 [

12] datasets. We observed that fine-tuning the VideoMAE [

2] pre-trained model after ranking the classification label position using the Label Ranker algorithm yielded more stable results, with outperforms the average accuracy of random label position by 3.48% (86.02% vs. 89.50%) and 1.4% (59.78% vs. 61.18%) respectively. The LDA [

9] method enhances the separability between classes, resulting in a more organized distribution of labels in the feature space. Compared to randomly assigned label position, the LDA [

9] ranking facilitates a more compact class distribution in the label space, contributing to the stability of the optimization process. The unsupervised nature of LDA [

9] allows it to rank label positions based on input features without relying on labeled data. Therefore, the Label Ranker provides a structured ranking method during random label position initialization, mitigating the negative effects of label ranking randomization.

Table 2.

Compare the results of the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model trained from scratch and the VideoMAE [

2] pre-trained model fine-tuned on UCF101 [

11].

Table 2.

Compare the results of the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model trained from scratch and the VideoMAE [

2] pre-trained model fine-tuned on UCF101 [

11].

| Model |

from scratch |

Pre-trained Data |

Label State |

Accuracy |

| Vanilla ViT-B [8] |

✓ |

− |

Sequence |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| Avg. |

− |

− |

− |

|

| VideoMAE [2] |

× |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Sequence |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| Avg. |

− |

− |

− |

|

| |

× |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Label Ranker |

|

On the other hand, the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model exhibited stable performance on the UCF101 [

11] and HMDB51 [

12] datasets compared to the fine-tuning results of the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model. The results on UCF101 [

11] fluctuated between 51.38% and 51.43%, while the performance on HMDB51 [

12] ranged from 18.09% to 18.13%, both indicating minimal performance variation. In contrast, the performance fluctuations of the VideoMAE [

2] pre-trained model with random label ranking fine-tuning were 6.64% (81.68% vs. 88.32%) and 8.24% (55.88% vs. 64.12%) respectively.

Table 3.

Compare the results of the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model trained from scratch and the VideoMAE [

2] pre-trained model fine-tuned on HMDB51 [

12].

Table 3.

Compare the results of the Vanilla ViT-B [

8] model trained from scratch and the VideoMAE [

2] pre-trained model fine-tuned on HMDB51 [

12].

| Model |

from scratch |

Pre-trained Data |

Label State |

Accuracy |

| Vanilla ViT-B [8] |

✓ |

− |

Sequence |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| ✓ |

− |

Random |

|

| Avg. |

− |

− |

− |

|

| VideoMAE [2] |

× |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Sequence |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| × |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Random |

|

| Avg. |

− |

− |

− |

|

| |

× |

Kinetics 400 [15] |

Label Ranker |

|

4.3.2. Performance Analysis and Limitations

Based on the analysis of the experiments presented above, the Label Ranker method exhibits lower computational complexity compared to techniques such as adversarial training [

6] or consistency regularization [

7], making it suitable for large-scale datasets. LDA [

9] primarily performs feature transformation through matrix operations, which incurs significantly less computational burden than other methods. By optimizing label ranking, the Label Ranker enhances the stability of model performance during the fine-tuning phase, reducing fluctuations caused by label position randomization. Additionally, the Label Ranker improves the generalization capability of the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model in downstream tasks, thereby increasing the fine-tuned accuracy.

However, while the Label Ranker offers an effective label ranking methodology, it also has certain limitations. The performance of the Label Ranker relies on linear relationships between features, and in the context of complex nonlinear data distributions, it may not adequately capture the nonlinear relationships between classes. Therefore, future research could explore the integration of nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques such as t-SNE [

18], PCA [

19], or deep learning methods to further enhance the performance of the Label Ranker in high-dimensional complex data.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Conclusions

This study investigates the impact of classification label position encoding on the fine-tuning process of the visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model, particularly focusing on the effects of random label position initialization on fine-tuning outcomes. Through experiments conducted on datasets such as CIFAR-100 [

10], UCF101 [

11], and HMDB51 [

12], the results demonstrate that random initialization of label positions significantly affects the fine-tuning results of the pre-trained model. Label ranking randomization leads to instability in the model’s optimization path, resulting in performance fluctuations. To address the instability issues arising from label position randomization, we propose a classification label position ranking algorithm based on LDA [

9] and Euclidean distance, Label Ranker. Experimental results validate that this approach effectively mitigates the impact of label ranking randomness on the optimization path, further enhancing the stability and fine-tuning performance of the model. This not only confirms the self-awareness preference of visual masked self-supervised pre-trained model towards the label position but also indicates that maintaining consistency in preferences can contribute to performance improvements.

5.2. Future Work

While the Label Ranker method effectively reduces the randomness associated with label initialization, there remains significant potential to explore more efficient label ranking strategies. Specifically, in large-scale multi-class tasks, a crucial direction for future research will be how to further stabilize label position encoding while ensuring computational efficiency. The label position random initialization previously employed still relies on one-hot encoding. Future work could consider introducing more sophisticated label encoding methods based on task characteristics, such as semantic-aware label embeddings including Word2Vec [

20], GloVe [

21], to enhance the model’s sensitivity to label positioning and minimize interference during the fine-tuning process.

References

- He, Kaiming, et al. "Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners." Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2022.

- Tong, Zhan, et al. "Videomae: Masked autoencoders are data-efficient learners for self-supervised video pre-training." Advances in neural information processing systems 35 (2022): 10078-10093.

- Feichtenhofer, Christoph, Yanghao Li, and Kaiming He. "Masked autoencoders as spatiotemporal learners." Advances in neural information processing systems 35 (2022): 35946-35958.

- Bachmann, Roman, et al. "Multimae: Multi-modal multi-task masked autoencoders." European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022.

- Xu, Suping, Lin Shang, and Furao Shen. "Latent Semantics Encoding for Label Distribution Learning." IJCAI. 2019.

- Miyato, Takeru, et al. "Virtual adversarial training: a regularization method for supervised and semi-supervised learning." IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 41.8 (2018): 1979-1993. [CrossRef]

- Kingma, Durk P., et al. "Semi-supervised learning with deep generative models." Advances in neural information processing systems 27 (2014).

- Dosovitskiy, Alexey. "An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

- Xanthopoulos, Petros, et al. "Linear discriminant analysis." Robust data mining (2013): 27-33.

- Krizhevsky, Alex, and Geoffrey Hinton. "Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images." (2009): 7.

- Soomro, K. "UCF101: A dataset of 101 human actions classes from videos in the wild. arXiv:1212.0402 (2012).

- Kuehne, Hildegard, et al. "HMDB: a large video database for human motion recognition." 2011 International conference on computer vision. IEEE, 2011.

- Jaiswal, Ashish, et al. "A survey on contrastive self-supervised learning." Technologies 9.1 (2020): 2. [CrossRef]

- Russakovsky, Olga, et al. "Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge." International journal of computer vision 115 (2015): 211-252.

- Kay, Will, et al. "The kinetics human action video dataset. arXiv:1705.06950 (2017).

- Loshchilov, Ilya, and Frank Hutter. "Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv:1608.03983 (2016).

- Loshchilov, I. "Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv:1711.05101 (2017).

- Van der Maaten, Laurens, and Geoffrey Hinton. "Visualizing data using t-SNE." Journal of machine learning research 9.11 (2008).

- Abdi, Hervé, and Lynne J. Williams. "Principal component analysis." Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: computational statistics 2.4 (2010): 433-459.

- Rong, Xin. "word2vec parameter learning explained. arXiv:1411.2738 (2014).

- Pennington, Jeffrey, Richard Socher, and Christopher D. Manning. "Glove: Global vectors for word representation." Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP). 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).