Introduction

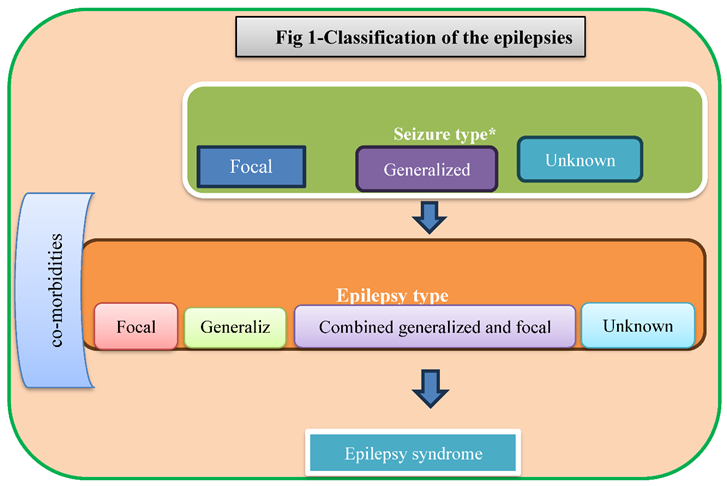

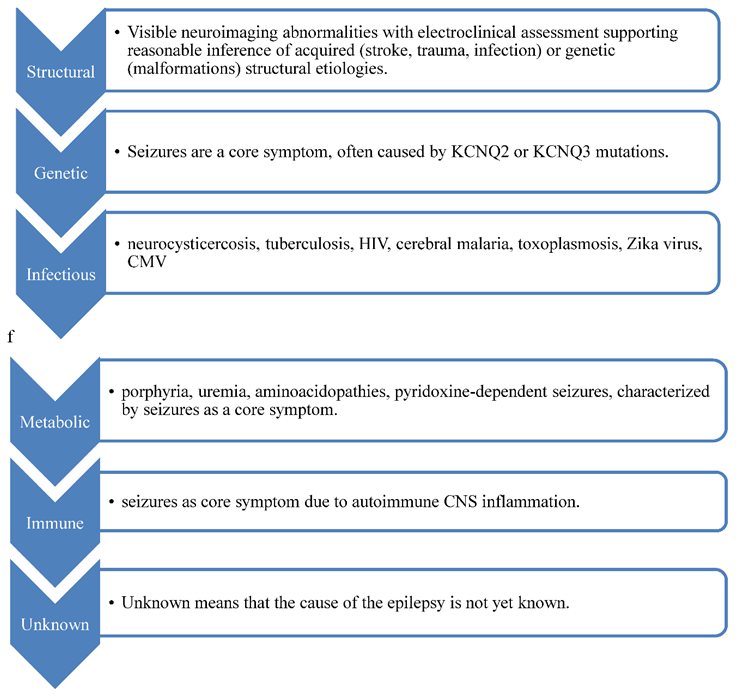

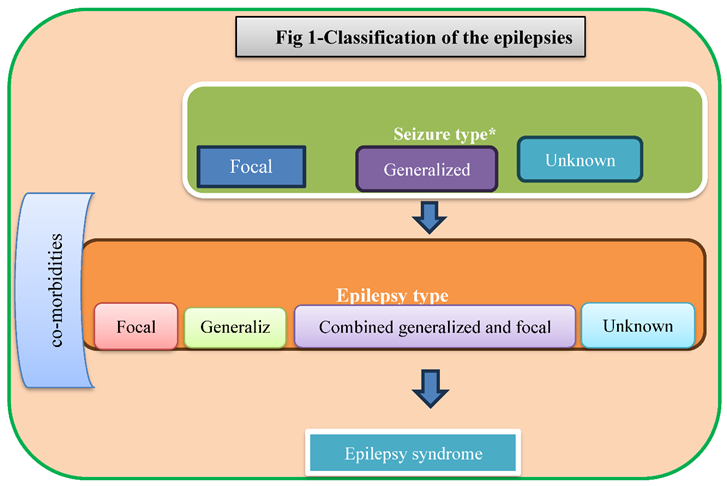

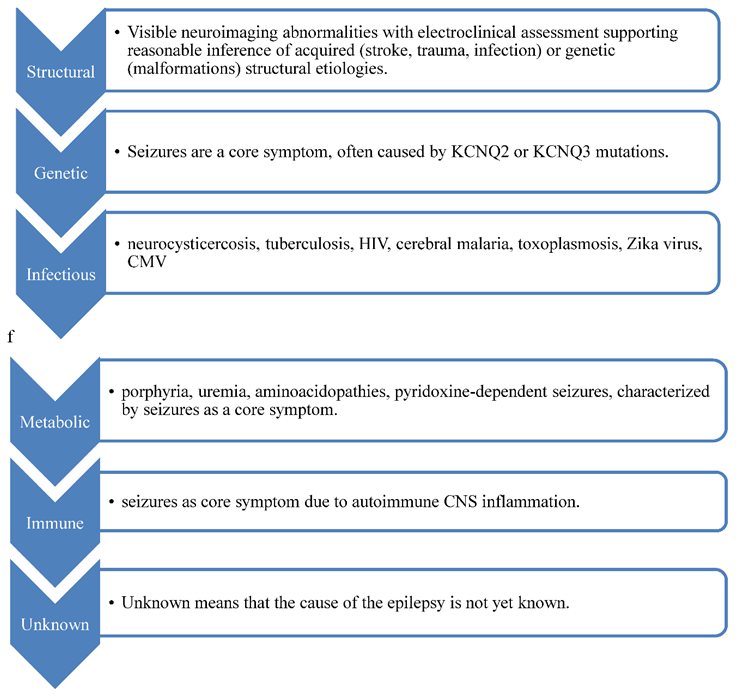

Definitions in epilepsy have always been problematic. The disorder is characterized by seizures but not all seizures result from epilepsy or are brought on by drugs (1). The new Classification of the Epilepsies is a multilevel classification, designed to cater to classifying epilepsy in different clinical environments (Figure 1) Electroencephalogram (EEG), video and Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies are mostly use for diagnosis of epilepsy (2).

Genetic, infectious, metabolic, immune, and unknown. Tuberous sclerosis has both structural and genetic etiologies, impacting surgery, counseling, and targeted therapies like mtor inhibitors.

The market's supply of antiepileptic drugs (AED) continues to rise. When selecting a medication for patients with epilepsy, patients should consider the drug's range of efficacy in various seizure types, adverse effects profile, pharmacokinetic characteristics, susceptibility to cause or be a target of clinically significant drug-drug interactions, ease of use, and cost. When choosing a medication, it's also crucial to consider the availability of kid-friendly formulations and any possible benefits for co-morbid diseases. Numerous AEDs are highly effective and often used for different disorders, such as mental illnesses, migraine, neuropathic pain, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and many more. Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind AED actions has improved recently. (3).

Method

The focus of the current review is on following recommendations for antiepileptic medication usage in pregnant epileptic patients. The following search terms were used to access the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science databases: Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) OR drugs during pregnancy AND epilepsy. Other drugs not included except recommendations for pregnant epileptic patients using medication. This review's storyline articles that discuss the many types of epilepsy, their causes, how to diagnose them with antiepileptic drugs, and how to treat pregnant epilepsy patients. English-language articles were among those included. The publications were chosen based on their applicability to pharmacological usage in patients with pregnancy-related epilepsy. For analytical purposes, all articles published at any time were included.

Result

Table 1 shows List of antiepileptic drug use in pregnancy with mechanism of action.(3,4).

Literature Finding

There is evidence from several research that some antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are teratogenic and raise the incidence of congenital abnormalities. Given that many epilepsy patients continue to use these drugs throughout pregnancy, it is essential to give them comprehensive information about the possible risks associated with AED usage. The risk of malformation has been reported to be particularly high for the following AEDs: carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, topiramate, and valproate. Lamotrigine usage does not, however, seem to increase the chance of severe abnormalities. No elevated risk has been connected to other AEDs such as gabapentin, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, primidone, and zonisamide. When compared to other AEDs, phenobarbital exposure has been connected to greater rates of several malformations, notably cardiac malformations, while valproate exposure has been linked to abnormalities of the neural tube, the heart, the oro-facial/craniofacial system, the skeleton, and the limbs (4).

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are known to increase the risk of congenital malformations (CMs), according to a systematic review and Bayesian random-effects network meta-analysis comparing the risk of CMs and prenatal outcomes in infants and children exposed to AEDs in utero. In terms of main CMs, ethosuximide, valproate, topiramate, phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and polytherapy all shown considerable damage. However, neither lamotrigine nor levetiracetam showed a noticeably elevated risk when compared to the control (5).

As long as valproate and topiramate are avoided, employing combinations of antiepileptic medications during pregnancy can be advantageous for the mother and fetus. Combinations like lamotrigine and levetiracetam offer the chance to manage seizures and guarantee fetal safety (6).

Pregnant women with epilepsy (PWWE) were included in the Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) experiment; 259 (73.8%) of them got monotherapy, 77 (21.9%) received polytherapy, and 15 (4.3%) had no AEDs at all. The most common AED monotherapy regimens included lamotrigine (42.1%), levetiracetam (37.5%), carbamazepine (5.4%), zonisamide (5.0%), oxcarbazepine (4.6%), and topiramate (3.1%). Each of the other one-on-one treatments costs less than 1%. The majority of AED polytherapies (41.9%) consisted of lamotrigine and levetiracetam, followed by lacosamide and levetiracetam (6.5%) and lamotrigine and zonisamide (5.2%). (7).

The IQ decline in children exposed to sodium valproate (VPA) during pregnancy is the most significant discovery. This large IQ loss has the potential to have an effect on the children's future academic and professional success. The developmental quotient (DQ) was poorer in children exposed to CBZ, VPA, and other medicines, even if the IQ of children exposed to carbamazepine or lamotrigine did not change significantly from control groups. Children exposed to CBZ had IQ scores that were equivalent to those exposed to phenytoin. (8).

A number of variables, such as age, length of usage, monotherapy versus polytherapy, pregnant status, and possible drug interactions, should be taken into account when prescription antiseizure drugs (ASMs). ASM prescriptions were given to around 15% of women of reproductive age in 2019; this frequency persisted throughout the research period. The most often used ASMs were pregabalin, valproate, topiramate, and levetiracetam, with utilization rates ranging from 22.3% to 13.1%. prescriptions for valproate fell 10% from 2010 levels. Levetiracetam (16.6%) and lamotrigine (16.6%) were the most often given drugs for pregnant women needing ASMs (9).

Both focal and widespread epilepsies are frequently treated with topiramate. For oral therapy, it is marketed as tablets and sprinkles capsules. Idiopathic generalized epileptic pregnant lady who had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure in the third trimester due to low TPM levels related to pregnancy, followed by recurrent lengthy absences (10).

Non-pharmacological therapies are crucial in treating pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Potential therapeutic targets include neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, metabolic dysregulation, and electrophysiological abnormalities. Vitamins with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties can be beneficial in epilepsy therapy, aiding in the management of the condition (11).

All age groups saw a decline in valproate and carbamazepine prescriptions. Options for levetiracetam, topiramate, and lamotrigine rose while oxcarbazepine prescriptions fell. For women aged 19 to 34, these improvements were statistically significant. Girls between the ages of 12 and 14 showed noticeable changes in valproate and carbamazepine, and women between the ages of 19 and 34 had the lowest valproate prescription rates (12).

After receiving commercial authorisation, pregnant women have started using more modern anti-seizure drugs (ASMs), including Lacosamide, Eslicarbazepine, and Brivaracetam. There were no increased risks of major birth defects or spontaneous abortion in the 55 prospectively and 10 retrospectively examined pregnancies exposed to lacosamide, according to the research. Lacosamide exposure during pregnancy, however, may result in bradycardia in babies. The increasing use of these modern ASMs during pregnancy highlights the need for more preconception counseling studies, particularly with reference to Lacosamide, Eslicarbazepine, and Brivaracetam (13).

Pregnant women with epilepsy have particular difficulties in managing their illness since both the ailment and antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) carry potential risks for both the mother and fetus. There are known teratogenic consequences of traditional AEDs such valproate (VPA) and phenytoin (PHT). Newer AEDs, however, are thought to be less teratogenic, such as levetiracetam and lamotrigine. Thus, earlier AEDs (VPA, PHT, phenobarbitone, and carbamazepine) have been used less widely globally than newer AEDs (LEV, LTG, zonisamide, clobazam, clonazepam, and oxcarbazepine) (14).

Conclusion

The use of AEDs during pregnancy is dependent on the risk-benefit ratio. Medication selection, preconception planning, frequent prenatal care, and folic acid supplements are all factors to consider when prescribing drugs to patients. The majority of AEDs that cause fetal congenital malformations (CMs) include ethosuximide, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, topiramate, and valproate, however there was no increased risk of substantial deformity with lamotrigine. Pregnant women can safely utilize gabapentin, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, primidone, zonisamide, oxcarbazepine, lacosamide, eslicarbazepine, and brivaracetam.

References

- Manford M. Recent advances in epilepsy. J Neurol. 2017 Aug;264(8):1811–24.

- Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, Connolly MB, French J, Guilhoto L, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia [Internet]. 2017 Apr [cited 2023 May 17];58(4):512–21. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Perucca E. An Introduction to Antiepileptic Drugs: INTRODUCTION TO ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS. Epilepsia [Internet]. 2005 Jun 6 [cited 2023 May 17];46:31–7. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Weston J, Bromley R, Jackson CF, Adab N, Clayton-Smith J, Greenhalgh J, et al. Monotherapy treatment of epilepsy in pregnancy: congenital malformation outcomes in the child. Cochrane Epilepsy Group, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2016 Nov 7 [cited 2023 May 14];2017(4). Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Veroniki AA, Cogo E, Rios P, Straus SE, Finkelstein Y, Kealey R, et al. Comparative safety of anti-epileptic drugs during pregnancy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of congenital malformations and prenatal outcomes. BMC Med. 2017 May 5;15(1):95. [CrossRef]

- Vajda FJE, O’Brien TJ, Graham JE, Hitchcock AA, Lander CM, Eadie MJ. Antiepileptic drug polytherapy in pregnant women with epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018 Aug;138(2):115–21. [CrossRef]

- Meador KJ, Pennell PB, May RC, Gerard E, Kalayjian L, Velez-Ruiz N, et al. Changes in antiepileptic drug-prescribing patterns in pregnant women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018 Jul;84:10–4. [CrossRef]

- Bromley R, Weston J, Adab N, Greenhalgh J, Sanniti A, McKay AJ, et al. Treatment for epilepsy in pregnancy: neurodevelopmental outcomes in the child. Cochrane Epilepsy Group, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2014 Oct 30 [cited 2023 May 14];2020(6). Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Avachat C, Birnbaum AK. Women of childbearing age: What antiseizure medications are they taking? Brit J Clinical Pharma [Internet]. 2023 Jan [cited 2023 May 14];89(1):46–8. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Apostolakopoulou L, Bosque Varela P, Rossini F, O’Sullivan C, Löscher W, Kuchukhidze G, et al. Intravenous topiramate for seizure emergencies – First in human case report. Epilepsy & Behavior [Internet]. 2023 May [cited 2023 May 14];142:109158. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Yang MT, Chou IC, Wang HS. Role of vitamins in epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior [Internet]. 2023 Feb [cited 2023 May 14];139:109062. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Wójcik K, Franciszek Kołek M, Dec-Ćwiek M, Słowik A, Bosak M. Trends in antiseizure medications utilization among women of childbearing age with epilepsy in Poland between 2015 and 2019. Epilepsy & Behavior [Internet]. 2023 Feb [cited 2023 May 14];139:109091. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Hoeltzenbein M, Slimi S, Fietz AK, Stegherr R, Onken M, Beyersmann J, et al. Increasing use of newer antiseizure medication during pregnancy: An observational study with special focus on lacosamide. Seizure [Internet]. 2023 Apr [cited 2023 May 14];107:107–13. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Bansal R, Suri V, Chopra S, Aggarwal N, Sikka P, Saha SC, et al. Change in antiepileptic drug prescription patterns for pregnant women with epilepsy over the years: Impact on pregnancy and fetal outcomes. Indian J Pharmacol. 2019;51(2):93–7. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

caption.

| Drugs |

Blockade of voltage dependent sodium channels |

Increase in brain

or synaptic

GABA levels |

Selective potentiation

of GABAA-mediated

responses |

Direct facilitation

of chloride

ion influx |

Blockade of calcium channels |

Other actions |

| Felbamate |

✓✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

× |

✓ (L-type) |

✓ |

| Gabapentin |

? |

? |

× |

× |

✓✓ (N-, P/Q-type) |

? |

| Lamotrigine |

✓✓ |

✓ |

× |

✓✓ |

✓✓ (N-, P/Q-, R-, T-type) |

✓ |

| Levetiracetam |

× |

? |

✓ |

× |

✓ (N-type) |

✓✓ |

| Oxcarbazepine |

✓✓ |

? |

× |

× |

✓ (N- and P-type) |

✓ |

| Pregabalin |

× |

× |

× |

× |

✓✓ (N-, P/Q-type) |

× |

| Tiagabine |

× |

✓✓ |

× |

× |

× |

× |

| Vigabatrin |

× |

✓✓ |

× |

× |

× |

× |

| Zonisamide |

✓✓ |

? |

× |

× |

✓✓ (N-,P-,T-type) |

✓ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).