1. Introduction

Pneumonia is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in under-five children causing the deaths of about 700,000 under 5 children every year, or about 2,000 every day [

1], [

2]. According to the Cause of Death Statistics report of Registrar General India 2017–19, pneumonia emerged as one of the main causes of death for under-five children, accounting for 17.5% of fatalities in India [

3]. A number of studies have brought to fore that Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcal pneumoniae) is the leading cause of pneumonia and it also causes a wide spectrum of diseases including both fatal invasive diseases (meningitis and sepsis) and non-invasive diseases (otitis media and sinusitis) [

4,

5,

6].

Considering the large burden of disease and the vaccine preventable nature of pneumococcal diseases, the World Health Organisation (WHO) (2012) released a position paper on Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV10 and PCV13) endorsing them as a safe and effective tool to prevent pneumococcal diseases [

7]. In India, the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (NTAGI) suggested the introduction of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) in the Universal Immunization Program (UIP) in 2015 [

8]. Following this, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India (GoI) decided to introduce PCV under UIP in 2017 [

9].

India embarked on its journey to introduce PCV in a phased manner, commencing with five high-burden states in May 2017 [

10]. This first phase included the following states; Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh. Later in 2021, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) announced a rapid pan India expansion of PCV [

11]. Needless to mention, introducing a new vaccine was a comprehensive task involving multiple processes spread over 4 years, multiple phases and 36 states/UTs. This especially became challenging during the pan-India expansion phase when the country was struck by the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic [

12,

13]. The unprecedented challenges such as personnel travel restrictions, social distancing posed by the pandemic made the nationwide scale-up more difficult, necessitating the development of various innovative tools, approaches, and processes to successfully roll out the vaccine.

The present study aims to chronicle the journey of PCV introduction in India from its introduction to its pan India expansion along with a brief overview of the impact of the introduction and future research implications.

2. Methodology

The present study deploys comprehensive desk review of available published and unpublished literature to document the journey of PCV introduction in India. For published literature, databases such as Google Scholar and PubMed were used. Grey literature included, but was not limited to, reports, newsletters, blogs, government documents, and speeches available in the public domain. Government documents included the PCV operational guidelines, meeting minutes, and training materials available in the public domain. Additionally, the authors—including the National EPI Manager from the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, donors from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Program Managers and Programme Officers from the lead technical agency, John Snow India—collaborated to share insights and reflect on their experiences with the introduction and expansion of PCV.

3. The Journey

3.1. Pre-Introduction

3.1.1. Evidence Generation and Synthesis:

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) were developed to overcome the shortcomings of capsular polysaccharide-based pneumococcal vaccines, which were less efficacious for children under the age of two, the age when invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) is most likely to cause death [

14]. A number of national and international studies analyzing the effectiveness of PCVs helped generate evidence to support the introduction of PCV in India.

Systematic reviews across high income, low- and middle-income countries presented the effectiveness of PCV on reducing invasive pneumococcal diseases in the under 5 years age group [

15,

16,

17]. Another meta-analysis reported that the efficacy of PCV in the reduction of invasive pneumococcal disease was 89%. Additionally, PCV has shown effectiveness against pneumonia, meningitis, bacteraemia/ sepsis, sinusitis, bronchitis, and otitis media [

18,

19]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of impact studies brought to fore that 3 years after onset of a 2+1 dose schedule of PCV with coverage of ≥80% throughout the ascertainment period, 98% reduction in the incidence rates of IPD was reported [

20]. Another study reported the effectiveness of PCV in reducing invasive pneumococcal disease and early effects of meningitis in children under the age of five [

21].

A large body of evidence was also generated for the Indian context. A study suggested that children exposed to PCV13 had a considerably lower chance of developing primary end-point pneumonia with or without other infiltrates (PEP±OI) in cases of severe community-acquired pneumonia [

22]. A number studies showcased the immunogenicity and safety of PCV in the Indian population [

23,

24,

25,

26].

3.1.2. Decision-Making Process:

The National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (NTAGI) recommended phased introduction of PCV under the UIP in August 2015. This recommendation was based on study findings of pneumococcal disease burden, prevalence of serotype, and antibiotic resistance in India which were highlighted in the minute recommendation by NTAGI [

27,

28]. The recommendations of the NTAGI were approved by the Empowered Program Committee (EPC) and subsequently by the Mission Steering Group (MSG) of National Health Mission (NHM).

The National Pneumococcal Vaccine Expert Committee was constituted by the GOI to guide the introduction of pneumococcal vaccine in the country. The committee recommended PCV13, a WHO prequalified vaccine, as the preferred vaccine type for introduction in the UIP based on the available information on product specifications and operational feasibility including multi-dose presentation and compliance with open vial policy [

29]. For the PCV-13 introduction under UIP, a dosing schedule of 2 primary doses at 6 weeks and 14 weeks followed by a booster dose at 9 months was recommended [

29]. This dosing schedule was in line with the existing UIP schedule. Subsequently, in May 2016, the Expert Committee Group recommended the introduction of PCV in the country under UIP [

28,

29]. By providing it through the UIP, the Government of India guaranteed fair access of PCV to the most vulnerable, the disadvantaged, and the underserved population of India which earlier was restricted to the private sector [

30]

.

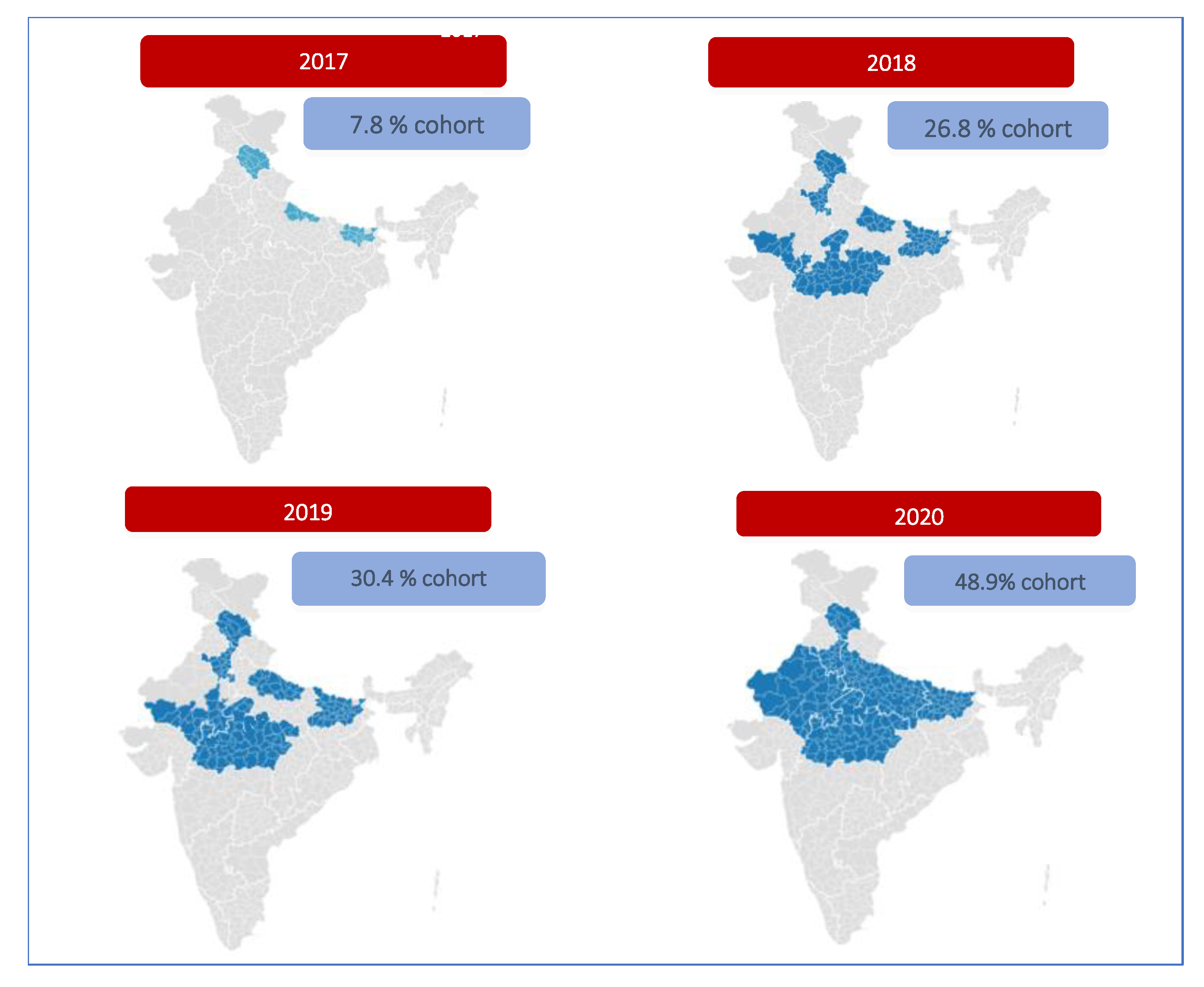

3.2. PCV Phase I introduction (2017-2020):

PCV was initially introduced in 5 high burden states, namely Himachal Pradesh, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan. It was launched on May 13, 2017 by the then Union Health Minister at Mandi, Himachal Pradesh. In the first year (2017), the cohort identified for vaccination included 2.1 million children, 100% of the districts in Himachal Pradesh, 50% of Bihar, and 10% of Uttar Pradesh.

This was followed by introduction in all districts of Madhya Pradesh and 25% of Rajasthan, 50% remaining districts in Bihar and 20% more districts in Uttar Pradesh in the next year. In 2019, 25% more districts in Rajasthan and 30% more districts in Uttar Pradesh was covered [

10]. By 2020, the entire state of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh was covered making PCV accessible to all the five states. As recommended by the Expert Committee Group, the available PCV-13 product was used in the selected geographies during this phase of introduction [

28,

29].

As with previous new vaccine introductions, the PCV was rolled out in a similar manner across the identified geographies. Commencing with a comprehensive preparedness assessment which is required at the national, state and district level prior to the new vaccine introduction. This was undertaken in the traditional paper-based format to ensure smooth planning of processes [

28].

This was followed by cascade training, starting with a pool of national level training of trainers (ToT) to state, district, and sub-district level trainings [

31]. To establish a team of master trainers at the national level, a national ToT was held. It was attended by immunization partners, including officials from identified states and partner organizations (WHO, UNICEF, UNDP, JSI, ITSU, and NCCVMRC). This was followed by in-person classroom training from State to District to the Block (Administrative unit) level. Detailed operational guidelines and frequently asked questions (FAQs) were developed and circulated in print among frontline health workers and program managers [

31].

For demand generation, standard procedures of IEC materials development and dissemination through mass media and social/digital media were undertaken. Media sensitization workshops were organised at the state level to provide an overview of the universal immunisation program, pneumococcal disease burden and importance of PCV [

32].

As part of the preparation for the PCV introduction in the selected states, it was ensured that sufficient cold chain space was made available. Also, proper functioning of the cold chain is essential to transport and store vaccines under strict controlled-temperature, without compromising their quality [

31,

32].

In its first year (2017) of introduction, PCV was rolled out in 100% of the districts of Himachal Pradesh, 50% of the districts of Bihar, and 10% of the districts of Uttar Pradesh. In 2018, the remaining 50% of districts in Bihar, the entire state of Madhya Pradesh, 25% of districts in Rajasthan, and an additional 20% of districts in Uttar Pradesh were covered. In 2019, PCV was made available in 25% more districts in Rajasthan and 30% more districts in Uttar Pradesh. By 2020, PCV was introduced in all the remaining districts of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, making PCV accessible to every child in these five states. Thus, by the mid of 2020, PCV was scaled up to the five high-burden states (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Himachal Pradesh), catering to 48.9% of the national cohort [

10,

32].

The geographic extent of PCV introduction from 2017 to 2020 is shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

District-wise geographic extent of PCV introduction 2017-2020.

Figure 1.

District-wise geographic extent of PCV introduction 2017-2020.

3.3. PCV Pan India Rapid Expansion (2020-21)

In 2019, Pneumosil, an indigenous 10-valent PCV product, received pre-qualification from the World Health Organisation, deeming it

safe and effective for use [

33]. Consequently, Pneumosil was licensed for use in India in 2020 following which it was launched as a PCV product by the then Union Health Minister on 28th December 2020 [

34,

35].

With the availability of a WHO pre-qualified indigenous affordable vaccine, the Government of India announced the nationwide expansion of PCV under UIP in the 2021-22 budget [

36]. In response to the budget speech, MoHFW undertook the pan India PCV rapid expansion in the remaining 31 states/UTs in 2021 [

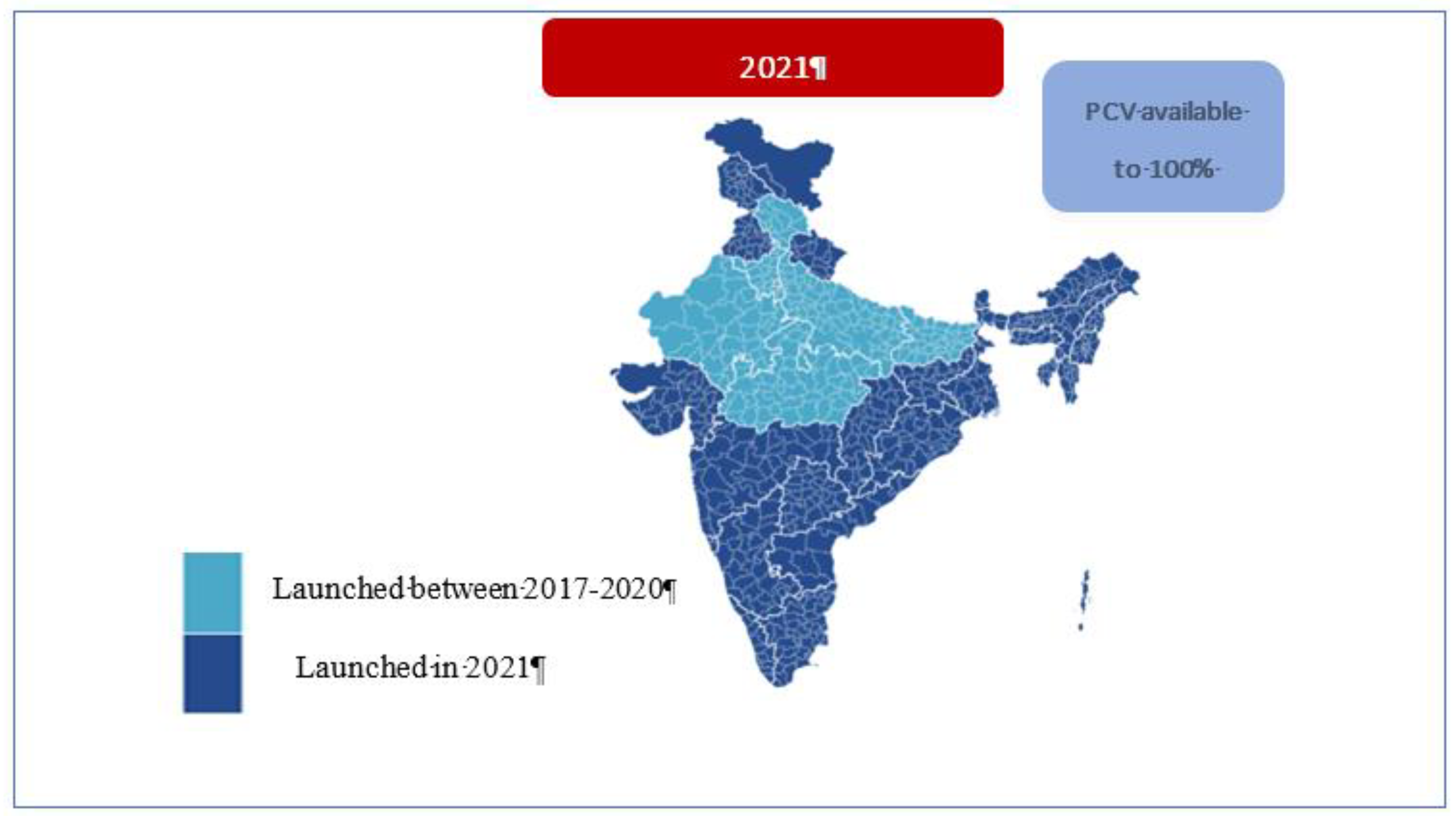

37]. It was intended that all 36 states/UTs will be covered culminating in 27 million children with access to PCV. Considering that the expansion coincided with the on-going COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, several novel approaches were applied to each step of new vaccine introduction mentioned below:

3.3.1. Preparedness Assessment

Due to the unprecedented challenge put forth by the pandemic, the process of traditional paper-based manual preparedness assessment involving intensive documentation and supervisory visits was not possible [

38]. The lockdown enforced travel and social restrictions necessitated an alternative approach to achieve the task [

12]. As a result, an innovative, interactive, efficient, and user-friendly digital tool, PCV Roll Out Monitoring and Preparedness Tool (PROMPT) was developed to execute the process. It was a technology-driven solution created to carry out the preparedness assessment before the pan-India PCV expansion. This automated PROMPT tool was designed to eliminate the intensive manual documentation and reduce time needed to complete the task. The interactive, user-friendly dashboard interface and real-time monitoring of assessment status made the preparedness assessment exercise more efficient, time bound and trackable [

38]. Preparedness assessment was conducted in all 31 states on time to match the stipulated timeline for PCV expansion [

31,

39].

3.3.2. Training:

Since the service delivery of the entire UIP rests on the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and Auxiliary Nurse-Midwives (ANMs), the timely and effective training of these personnel is imperative. For the rapid scale up across 31 states, hybrid mode (combination of online and classroom training) of training was utilized for all levels of health functionaries to overcome the disruption posed by the pandemic [

40,

41].

Online mode of training facilitated the training of a large cohort of health workers within a short span of time. FAQs and detailed operational guidelines were drafted and disseminated using soft copies in addition to print-outs to overcome COVID-19 restrictions. This was an unprecedented process of training deployed given the circumstances. However, to supplement the online trainings, five animated videos based on the PCV FAQs were developed in 13 languages including Hindi and English [

42,

43]. These were widely circulated among health workers through messaging platforms like WhatsApp. The translation of these videos into regional languages made communication, training, and understanding of the operational aspects of PCV introduction much simpler.

3.3.3. Community Mobilization:

Awareness generation measures were undertaken using traditional media (radio spots, posters, banners, hoardings, leaflets), mass media (TV spots, newspaper advertisements), social/digital media (WhatsApp videos and messages) [

41,

44]. The major regional electronic media aired the live launch of the PCV followed by a media workshop and a Q&A session with the media.

Celebrities, politicians, and other prominent public figures were engaged for community mobilization. Radio jingles were deployed for awareness generation about the availability of PCV under UIP. During the pandemic, a great deal of awareness was generated and imbued in the community about respiratory pathogens, hand hygiene, social distancing, and the importance of wearing masks, which helped create awareness and generate demand during PCV expansion through social media, mass media and conventional methods including flyers [

40,

45,

46,

47].

3.3.4. Logistics and Cold Chain Space Management:

Before the pan India expansion of PCV, assessment of cold chain space and equipment was done to ensure sufficient space for vaccine storage. If there were non-functional deep freezers or ice-lined refrigerators (ILR), the State was notified, and they were repaired or replaced with new ones. Augmentation of cold chain space during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout ensured sufficient cold chain space for PCV expansion [

39,

40].

3.3.5. Monitoring and Supervision:

Monitoring and supervision are required to track the status of programme implementation, ensure accountability, and plan necessary corrective actions wherever needed. Following the pan-India PCV expansion, simultaneous rapid field monitoring was carried out to identify bottlenecks and provide feedback for immediate improvements. For this, standardized data collection formats were developed, covering all components of routine immunization. Rapid monitoring was undertaken by Government staff and immunization partner at the block and session level. A mobile application was used to allow ease of data collection, collation, and visualization [

48].

In 2021, PCV expansion to 31 states was completed within eight months of the budget announcement amidst the pandemic, demonstrating the strength and resilience of India’s healthcare delivery system [

11]. It was a remarkable achievement for all stakeholders involved in the PCV introduction (

Figure 2 & 3).

3.4. Post Introduction:

3.4.1. PCV Coverage

Since the pan India expansion of PCV in 2021, national level PCV coverage has shown a steady upward trend. The steady increase in PCV booster (Indicating completion of PCV dose schedule) coverage has been further corroborated in the recent WHO/UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage (WUENIC) as elaborated in

Figure 4 [

49]. Furthermore, in contrast to other low-and-middle-income countries, PCV-B in India has been consistently above the 80% mark since the last one year [

50,

51].

Figure 4.

PCV B coverage reported as per WUENIC in 2024.

Figure 4.

PCV B coverage reported as per WUENIC in 2024.

Figure 5 showcases the narrowing gap between the PCV B coverage and the proportion of birth cohort to whom PCV is available. As per the WUENIC data, the gap between the PCV coverage and the cohort to whom PCV is available has been consistently reducing since 2021.

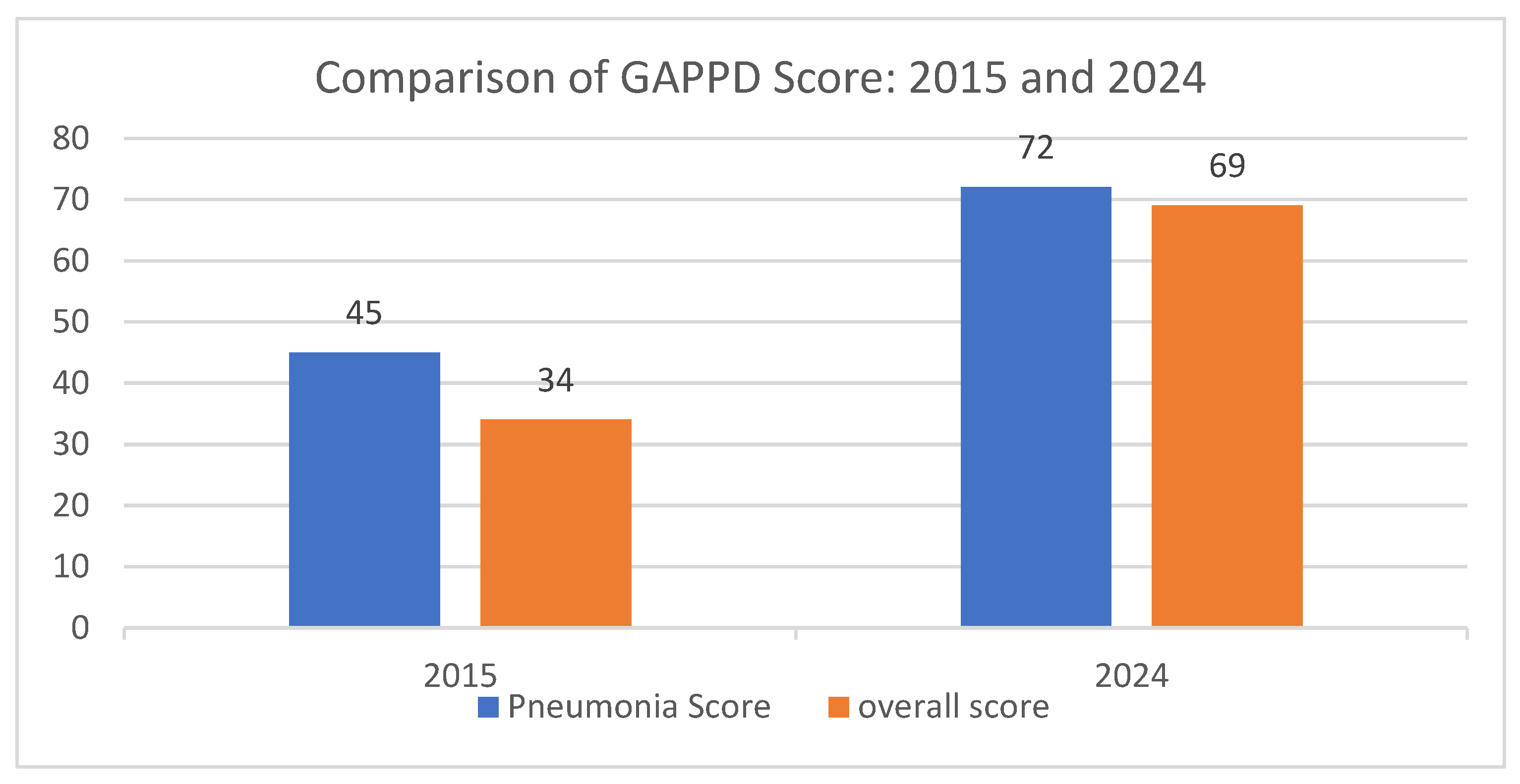

3.4.2. Potential Impact:

The Integrated Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD), launched by the WHO and UNICEF in 2009 and updated in 2013, lays out a comprehensive package of interventions aimed at ending preventable pneumonia and diarrhoea child deaths by 2025. Each year analysis of GAPPD scores based upon 10 key indicators to track global progress toward GAPPD targets are done. The increasing coverage of PCV has contributed to the improvement in both the pneumonia and overall GAPPD scores for India [

52,

53] (

Figure 6). As per the improvement of GAPPD score from 2015 to 2024, it is evident that the introduction of PCV in India has had a profound impact on child health, significantly reducing mortality among children under five years old. One of the most striking effects has been the reduction in pneumonia and diarrhoea-related deaths, which declined by 54.39% between 2016 and 2024. The number of deaths from these causes fell from 260,990 in 2016 to 119,012 in 2024, indicating the vaccine's effectiveness in preventing severe pneumococcal infections, a leading cause of childhood pneumonia. Furthermore, the overall under-five mortality rate has also seen a notable decline, decreasing from 41.06 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2016 to 29.06 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2022. This significant reduction has contributed to saving approximately 334,800 lives annually in the under-five age group, suggesting the critical contributory role of PCV in strengthening child survival efforts. By contributing to the averting of an estimated 334,800 deaths in this age group, the vaccine has probably played a pivotal role in improving child health outcomes in India, reinforcing the importance of sustained immunization programs to further enhance child survival rates [

54,

55,

56].

However, future large-scale population-based surveillance studies would be required to quantify the impact of PCV on the under-5 mortality and overall mortality and morbidity associated with pneumococcal diseases. This has been done in other LMICs to establish the impact of PCV introduction and support introduction in other countries [

57,

58,

59].

3.4.3. Product Switch:

PCV 13 (PREVNAR) was the first to be introduced in UIP in the country in 2017. This was followed by the introduction of PCV 10 (PNEUMOSIL) in 2021, the first indigenous PCV. In 2024, another PCV product was licensed for use under the UIP- PCV14 (PNEUBEVAX 14™). This is the second indigenous PCV product by a domestic manufacturer. Currently, two PCV products—PCV10 and PCV14—are available under the UIP. Both PCV 10 and PCV 14 offer defence against the most prevalent strains that cause pneumococcal illness [

60,

61].

4. Learnings and Future Research Implications

The introduction and rapid expansion of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) in India offer significant learnings and highlight key areas for future research. One of the major successes of the PCV rollout has been the ability to leverage existing immunization infrastructure to ensure widespread coverage. The phased approach allowed for systematic implementation, and innovative tools such as the PCV Roll Out Monitoring and Preparedness Tool (PROMPT) facilitated efficient monitoring despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, hybrid training models incorporating digital platforms enabled timely capacity-building among healthcare workers, ensuring the vaccine's smooth integration into the UIP.

While these achievements are commendable, continuous research and surveillance are necessary to optimize the impact of PCV in India. Future studies should focus on evaluating the long-term effectiveness of PCV in reducing under-five mortality and morbidity associated with pneumococcal diseases. Large-scale population-based surveillance is essential to quantify the impact of PCV introduction, as demonstrated in other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [

4,

62]. A study conducted in Kenya showed the effects of different PCV products (PCV10, PCV13, and the recently introduced PCV14) on reduction of the pneumococcal disease burden. Similar assessment should be done to determine the most effective vaccine formulation for the Indian context [

63].

Another crucial area for research is the effect of PCV introduction on antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Several studies have shown that PCVs contribute to reducing antibiotic use and AMR by preventing bacterial infections that would otherwise require antibiotic treatment [

64,

65]. Evaluating the impact of PCV on AMR in India could provide valuable insights into broader public health benefits beyond direct disease prevention. Furthermore, serotype replacement and the emergence of non-vaccine serotypes remain concerns following PCV introduction. Continuous monitoring of pneumococcal serotype distribution and invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) patterns will help guide vaccine policy decisions and the potential need for next-generation PCVs [

66,

67].

Additionally, cost-effectiveness studies assessing the economic benefits of PCV introduction should be conducted to provide policymakers with evidence to support sustained funding and vaccine procurement decisions [

68,

69]. While PCV introduction in UIP has significantly increased access, research should explore equity in vaccine coverage, particularly among marginalized and underserved populations. Understanding barriers to vaccine uptake and designing targeted interventions will help ensure equitable immunization access across all socio-economic groups [

69].

Furthermore, the role of PCV in preventing pneumonia-related hospitalizations and outpatient visits warrants detailed investigation. Studies assessing healthcare utilization trends pre- and post-PCV introduction can provide a clearer picture of the vaccine’s impact on overall healthcare burden. Such data would be instrumental in refining health system strategies and resource allocation to maximize public health benefits.

While India's PCV introduction journey has been a remarkable public health achievement, continued research is essential to maximize its impact. Key areas of future investigation include long-term effectiveness, serotype surveillance, AMR implications, cost-effectiveness, vaccine equity, and healthcare utilization. Strengthening surveillance systems and conducting robust epidemiological studies will provide critical evidence to inform future vaccine policy and enhance child health outcomes in India.

5. Conclusions

Pneumococcal pneumonia is one of the leading causes of lower respiratory diseases and death among under-five children in India. To bring down the burden of pneumonia, the MoHFW decided to launch PCV in a phased manner. With the introduction of PCV in UIP, millions of children receive protection against the leading cause of pneumonia. It was introduced initially in five high-burden states, following which pan-India expansion was completed in 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic coinciding with the PCV expansion posed multiple challenges, necessitating innovative approaches to ensure the smooth rollout of PCV across the remaining 31 states/UTs of India. The careful and intricate planning and meticulous execution by MoHFW, with the support of development partners and other stakeholders, allowed a successful rollout of PCV in tandem with the largest COVID-19 vaccination drive in the world.

Since the pan-India expansion of the PCV in 2021, its national-level coverage has steadily increased. PCV booster coverage—an indicator of completion of PCV doses—has been consistently above 80% in India over the past year, outperforming other low- and middle-income countries. The WUENIC data highlights this upward trend, with PCV contributing positively to the WHO and UNICEF’s Integrated Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD) scores. However, future population-based studies will be required to document PCV’s impact on reducing child mortality and morbidity in India.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Dr Abida Sultana, Dr Rhythm Hora, Dr Rashmi Mehra and Dr Arup Deb Roy; Methodology: Dr Rhythm Hora, Dr Rashmi Mehra, Dr Amrita Kumari; Validation: Dr Pawan Kumar, Dr Rhythm Hora, Dr Rashmi Mehra, Dr Amanjot Kaur and Dr Arup Deb Roy; Resources: Dr Arup Deb Roy, Dr Amrita Kumari and Dr Arindam Ray; Data Curation: Ms. Seema Singh Koshal, Mr. Shyam Kumar Singh and Dr Syed F Quadri; Writing: Dr Abida Sultana, Dr Rhythm Hora, and Dr Rashmi Mehra; Original Draft Preparation: Dr Abida Sultana, Dr Rhythm Hora and Dr Rashmi Mehra; Writing – Review & Editing: Dr Pawan Kumar, Dr Arindam Ray, Dr Arup Deb Roy, Dr Kapil Singh and Dr Amrita Kumari; Visualization: Dr Kapil Singh, Dr Pawan Kumar, Mr Shyam Kumar Singh, Dr Abida Sultana, Dr Amanjot Kaur and Dr Rhythm Hora; Supervision: Dr Pawan Kumar, Dr Arup Deb Roy, Dr Amrita Kumari and Dr Arindam Ray; Project Administration: Dr Arup Deb Roy and Dr Arindam Ray; Funding Acquisition: NA.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCV |

Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine |

| MoHFW |

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare |

| NTAGI |

National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization |

| GAPPD |

Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea |

| PROMPT |

PCV Roll Out Monitoring and Preparedness Tool |

References

- Hogan DR, Gretchen AS, Ahmad RH, Ties B. Monitoring universal health coverage within the sustainable development goals: development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. Lancet Global Health. 2018, 6, 152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. (2024. November). A child dies of pneumonia every 43 seconds. Available at https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/pneumonia.

- Ram, S.V.D, Suman A.K. (2023). PREVENTION FROM PNEUMONIA. GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE. https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/1714/AU1004.pdf?source=pqals.

- O'Brien, K. L. , Wolfson, L. J., Watt, J. P., Henkle, E., Deloria-Knoll, M., McCall, N., Lee, E., Mulholland, K., Levine, O. S., Cherian, T., & Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet (London, England) 2009, 374, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, N. , Singh, M., Thumburu, K. K., Bharti, B., Agarwal, A., Kumar, A.,... & Chadha, N. Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease in children aged 1 month to 12 years living in South Asia: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014, 9, e96282. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, R. , Pradhan, S., Nagarathna, S., Wasiulla, R., & Chandramuki, A. Bacteriological profile of community acquired acute bacterial meningitis: a ten-year retrospective study in a tertiary neurocare centre in South India. Indian journal of medical microbiology 2007, 25, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2012). Pneumococcal vaccines WHO position paper – 2012. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WER8714_129-144.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. (2015. August 25). MEETING OF THE NATIONAL TECHNICAL ADVISORY GROUP ON IMMUNIZATION. Available at: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/29914318411467722384.pdf.

- Chaudhuri, P. (2017). India introducing routine pneumococcal vaccine.

- Sachdeva, A. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction in India’s universal immunization program. Indian pediatrics 2017, 54, 445–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINISTER OF FINANCE. (2021. February 1). Budget 2021-2022. Government of India. Available at: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2021-22/doc/Budget_Speech.pdf.

- Ranjan, R., Sharma, A., & Verma, M. K. Characterization of the Second Wave of COVID-19 in India. MedRxiv 2021, 2021-04.

- Lancet, T. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet (London, England) 2020, 395, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A. , & Taneja, D. K. Conjugate pneumococcal vaccines: Need and choice in India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine 2013, 38, 189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, J. D. , Conklin, L., Fleming-Dutra, K. E., Knoll, M. D., Park, D. E., Kirk, J.,... & Whitney, C. G. Systematic review of the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine dosing schedules on prevention of pneumonia. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 2014, 33, S140–S151. [Google Scholar]

- Conklin, L. , Loo, J. D., Kirk, J., Fleming-Dutra, K. E., Knoll, M. D., Park, D. E.,... & Whitney, C. G. Systematic review of the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine dosing schedules on vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease among young children. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 2014, 33, S109–S118. [Google Scholar]

- van de Vooren, K. , Duranti, S., Curto, A., & Garattini, L. Cost effectiveness of the new pneumococcal vaccines: a systematic review of European studies. Pharmacoeconomics 2014, 32, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pavia, M. , Bianco, A., Nobile, C. G., Marinelli, P., & Angelillo, I. F. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in children younger than 24 months: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e1103–e1110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghia, C. J. , Horn, E. K., Rambhad, G., Perdrizet, J., Chitale, R., & Wasserman, M. D. Estimating the Public Health and Economic Impact of Introducing the 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine or 10-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines into State Immunization Programs in India. Infectious Diseases and Therapy 2021, 10, 2271–2288. [Google Scholar]

- Schönberger, K. , Kirchgässner, K., Riedel, C., & von Kries, R. Effectiveness of 2+ 1 PCV7 vaccination schedules in children under 2 years: a meta-analysis of impact studies. Vaccine 2013, 31, 5948–5952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berman-Rosa, M. , O’Donnell, S., Barker, M., & Quach, C. Efficacy and effectiveness of the PCV-10 and PCV-13 vaccines against invasive pneumococcal disease. Pediatrics 2020, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, S. , Kohli, N., Agarwal, M., Pandey, C. M., Rastogi, T., Pandey, A. K.,... & Shukla, R. C. Effectiveness of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on radiological primary end-point pneumonia among cases of severe community acquired pneumonia in children: A prospective multi-site hospital-based test-negative study in Northern India. Plos one 2022, 17, e0276911. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj, K. , Chinnakali, P., Majumdar, A., & Krishnan, I. S. Acute respiratory infections among under-5 children in India: A situational analysis. Journal of natural science, biology, and medicine 2014, 5, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Amdekar, Y. K. , Lalwani, S. K., Bavdekar, A., Balasubramanian, S., Chhatwal, J., Bhat, S. R.,... & Scott, D. A. Immunogenicity and safety of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy infants and toddlers given with routine vaccines in India. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 2013, 32, 509–516. [Google Scholar]

- Lalwani, S. K. , Ramanan, P. V., Sapru, A., Sundaram, B., Shah, B. H., Kaul, D.,... & Lockhart, S. P. Safety and immunogenicity of a multidose vial formulation of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine administered with routine pediatric vaccines in healthy infants in India: A phase 4, randomized, open-label study. Vaccine 2021, 39, 6787–6795. [Google Scholar]

- Lalwani, S. , Chatterjee, S., Chhatwal, J., Verghese, V. P., Mehta, S., Shafi, F.,... & Schuerman, L. Immunogenicity, safety and reactogenicity of the 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) when co-administered with the DTPw-HBV/Hib vaccine in Indian infants: a single-blind, randomized, controlled study. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2012, 8, 612–622. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. (2015, August 25). Meeting of the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization. Available from: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/29914318411467722384.pdf.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. (2017). National Operational Guidelines Introduction of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV). Available at: http://www.nccmis.org/document/PCV%20operational%20guidelines.pdf.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Government of India. (2017). Pneumococcal Vaccine Introduction Plan. Available at: https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/temp/gavi_1570473800/India-PCV-2017/PCV%20Introduction%20Plan%20-%20India.pdf.

- Zodpey, S. , Farooqui, H. H., Chokshi, M., Kumar, B. R., & Thacker, N. Pediatricians' perspectives on pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: An exploratory study in the private sector. Indian Journal of Public Health 2015, 59, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Koshal, S. S. , Ray, A., Hora, R., Kaur, A., Quadri, S. F., Mehra, R.,... & Roy, A. D. Critical factors in the successful expansion of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine: X 2023, 14, 100328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. (2017). Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan (cMYP) 2018—22. Universal Immunization Programme. REACHING EVERY CHILD. Available at: https://itsu.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/cMYP_2018-22.

- Alderson, M. R. , Sethna, V., Newhouse, L. C., Lamola, S., & Dhere, R. Development strategy and lessons learned for a 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PNEUMOSIL®). Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2021, 17, 2670–2677. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2020, December 28). Indigenous Vaccine also a step towards Atmanirbhar Bharat, being Vocal for Local. Available at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx.

- Press Information Bureau (PIB). (2021). Dr Mansukh Mandaviya launches Nationwide expansion of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) under the Universal Immunization Programme (UIP) [Internet]. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1767478#:~:text=Mansukh%20Mandaviya%20today%20launched%20the,to%20create%20widespread%20mass%20awareness.

- MINISTER OF FINANCE. Government of India. (2021. February 1). Budget 2021-2022. Available at: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2021-22/doc/Budget_Speech.pdf.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (2022. January 2). INITIATIVES & ACHIEVEMENTS-2021. Available at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1787361.

- Kaur, A. , Ray, A., Hora, R., Koshal, S. S., Quadri, S. F., …& Roy, A. D. (2023). Novel Digitization of Preparedness Assessment for Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Introduction in Immunization Programme: Experience from India. EC Paediatrics 2023, 12, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. (2021. January). National Operational Guidelines Introduction of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV). Available at: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/PCV_Operational%20Guidelines_Jan%20%202021.pdf.

- Hora, R. , Ray, A., Mehra, R., Priya, T., Koshal, S. S., Agrawal, P.,... & Deb Roy, A. Enablers and barriers to the scaling up of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in India during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Health services insights 2023, 16, 11786329231189407. [Google Scholar]

- Linked Immunisation Action Network. (2021). Training health workers virtually during COVID-19. Available from: https://www.linkedimmunisation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Training-health-workers-virtually-during-COVID-19-slidedeck.pdf.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2021). PCV FAQ Animated video. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yTnE84KDkLE.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2021). PCV FAQ Animated video. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZEA9p82ptw0.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2021 October 21). Dr Mansukh Mandaviya launches Nationwide expansion of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) under the Universal Immunization Programme (UIP). Available at: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1767478.

- Times of India. (2021 September 19). West Bengal may roll out children pneumonia vaccine from civic clinics in October. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/west-bengal-may-roll-out-children-pneumonia-vaccine-from-civic-clinics-in-october/articleshow/86335510.cms.

- Times of India. (2021. July 12). Newborns to get pneumococcal vaccine free of cost this week [Internet]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/nagpur/newborns-to-get-pneumococcal-vaccine-free-of-cost-this-week/articleshow/84328266.cms.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. New Delhi. Government of India. (2021). Facts about PCV. Available from: https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Leaflet%20English%20PCV.pdf.

- Sharda, S. , Kshtriya, P., Agrawal, P. K., Singh, P., Trakroo, A., Joshi, A.,... & Prinja, S. Digital supportive supervision (DiSS) of maternal health, child health and nutrition (MCHN) service delivery in Rajasthan, India: study protocol for impact evaluation and cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ open 2024, 14, e086956. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2024. July 15). Immunization 2024 India country profile. UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage-2023 revision. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/immunization-2024-india-country-profile.

- Assefa, A. , Kiros, T., Erkihun, M., Abebaw, A., Berhan, A., & Almaw, A. Determinants of pneumococcal vaccination dropout among children aged 12–23 months in Ethiopia: a secondary analysis from the 2019 mini demographic and health survey. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12, 1362900. [Google Scholar]

- Oboh, J. I., Osagie, R. N., Ayobami, A. A., Okijiola, S. O., & Ayinde, A. O. ASSESSMENT OF IMMUNIZATION COVERAGE AND FACTORS THAT DETERMINE DROPOUT RATE AMONG CHILDREN 0-23 MONTHS OF AGE, IN ESAN CENTRAL LGA, EDO STATE, NIGERIA.

- WHO-UNICEF. (2013). End Preventable Deaths: Global Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea. World Health Organization/The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/the integrated global action plan for prevention and control of pneumonia and diarrhoea (gappd).

- International Vaccine Access Center. (2024. November 12). Tracking Progress Toward Pneumonia and Diarrhea Control. Available at: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/ivac/tracking-progress-toward-pneumonia-and-diarrhea-control.

- International Vaccine Access Center. (2018). Pneumonia & Diarrhea Progress Report 2018. Available from: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2024-02/pneumonia-and-diarrhea-progress-report-2018-1ax.pdf.

- International Vaccine Access Center. (2024). Pneumonia & Diarrhea Progress Report Card 2024. Available from: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2024-10/IVAC-report_2024_final.pdf.

- UNICEF Data. Under-five mortality rate, India. [Internet]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL_DATAFLOW&ver=1.0&dq=IND.CME_MRY0T4._T&startPeriod=1970&endPeriod=2024.

- Lekhuleni, C. , Ndlangisa, K., Gladstone, R. A., Chochua, S., Metcalf, B. J., Li, Y.,... & du Plessis, M. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on invasive pneumococcal disease-causing lineages among South African children. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 8401. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck-Paim, C. , Taylor, R. J., Alonso, W. J., Weinberger, D. M., & Simonsen, L. Effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction on childhood pneumonia mortality in Brazil: a retrospective observational study. The Lancet Global Health 2019, 7, e249–e256. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, G. A. , Hill, P. C., Jeffries, D. J., Hossain, I., Uchendu, U., Ameh, D.,... & Corrah, T. Effect of the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease in The Gambia: a population-based surveillance study. The Lancet infectious diseases 2016, 16, 703–711. [Google Scholar]

- The Times of India. (2022. September 1). Bharadwaj S. SEC recommends Bio E’s 14-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine PCV14 for infants. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/sec-recommends-bio-es-14-valent-pneumococcal-conjugate-vaccine-pcv14-for-infants/articleshow/93927494.cms.

- Matur, R. V. , Thuluva, S., Gunneri, S., Yerroju, V., reddy Mogulla, R., Thammireddy, K.,... & Narayan, J. P. Immunogenicity and safety of a 14-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (PNEUBEVAX 14™) administered to 6–8 weeks old healthy Indian Infants: A single blind, randomized, active-controlled, Phase-III study. Vaccine 2024, 42, 3157–3165. [Google Scholar]

- Gessner BD, Jiang Q, Van Beneden C, et al. The impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia: a systematic review of high-income and low-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018, 18, 339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Klugman, K. P. , & Rodgers, G. L. Population versus individual protection by pneumococcal conjugate vaccination. Lancet (London, England) 2019, 393, 2102–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagan, R. , & Klugman, K. P. Impact of conjugate pneumococcal vaccines on antibiotic resistance. The Lancet infectious diseases 2008, 8, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laxminarayan, R. , Matsoso, P., Pant, S., Brower, C., Røttingen, J. A., Klugman, K., & Davies, S. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. The Lancet 2016, 387, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, D. M. , Malley, R., & Lipsitch, M. Serotype replacement in disease after pneumococcal vaccination. The Lancet 2011, 378, 1962–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Feikin, D. R. , Kagucia, E. W., Loo, J. D., Link-Gelles, R., Puhan, M. A., Cherian, T.,... & Serotype Replacement Study Group. Serotype-specific changes in invasive pneumococcal disease after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction: a pooled analysis of multiple surveillance sites. PLoS medicine 2013, 10, e1001517. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Sweet S, Chang J, et al. Economic evaluation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in India. BMC Public Health. 2019, 19, 1542. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo-Méndez, M. C. , Barros, A. J., Wong, K. L., Johnson, H. L., Pariyo, G., França, G. V., Wehrmeister, F. C., & Victora, C. G. Inequalities in full immunization coverage: trends in low- and middle-income countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2016, 94, 794–805B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).