1. Introduction

1.1. The Museum Between Map and Territory

Territories and ’meta-territories’ of the cultural objects are variuos: the place in which, or for which, they were created, or a new space, different from the original one, in which they are displayed to the public, as a museum. A non-place, the latter, an abstract, metaphysical space in which the logical connections among objects are divorced from their original reasons for being. On the other hand, the museum is also a new territory, a living space, crossed by people that, hopefully, want not only to look at objects but also to experience them, understand them and get excited by entering their stories. Multiple contexts therefore intertwine. The past life of the objects and their present life establish a relationship with the experience of those approaching them [

1].

Therefore, the process of contextualization of the cultural object and attribution of meaning is diachronic, evolving through different cycles of interaction, through variations and redundancies, and differ from era to era, from person to person.

The virtual dropped into the real museum should foster a less hurried and consumerist, more profound comprehension of the cultural heritage, but also a creative approach, capable of soliciting the individual on multiple perceptual, cognitive and emotional levels.

So, thanks to multimedia and phygital realities, museums can become active workshops of cultural experiences that build bridges between lives/cultures of the past and our time.

1.2. Structure of the Paper

This paper focuses on the topic of multisensory museums and the design of effective hybrid realities applied to cultural heritage, that is cultural experiences were real and digital are combined and integrated, aiming at representing and transmitting cultural heritage to the public in an innovative and engaging way, considering both tangible and intangible values. The impact of multisensory communication in museums, empowered by technological innovation, will also be considered in relation to the sense of authenticity of the cultural message perceived by the public entering in contact with such “extended” museum contents. Which are the criteria to design a deep, useful and rich cultural experience? How can we stimulate in the audience involvement, understanding, memorization, imagination and creative elaboration?

Considerations expressed in the article come from the author’s academic background in preservation and valorisation of cultural heritage, art-history and museology [

2] and from her 25 years’ research activity and experience, in the field of digital innovation in cultural venues and virtual museums. They are corroborated by the results of several surveys carried out on thousands of visitors approaching digital contents in Italian and European Museums.

Section 1, the introduction, presents the main concepts and topics, the purposes and the privileged target of this contribution. It introduces the concept of extended reality and phygital experience and the reasons for their use in museums and cultural venues. The state of the art of multisensory experiences in museums is discussed in relation to ethical issues, as accessibility, richness and reliability of contents, sense of authenticity, connection with the territory, inclusivity, and considering the new frontiers disclosed by artificial intelligence (AI), NFT, metaverse and by the consequent new value chains. Then the user-centered approach in communication is introduced, where perception, action, motivation, emotion and cognition are addressed at creating involving and memorable experiences, according to logics other than fast cultural consumerism.

Section 2, Material and Methods, presents the basic principles of multisensory museums: narration, interaction, progressive immersion and understanding of contents, mixed reality, tactile interfaces, media combination and hybridisation, individual and social dimensions, sense of wonder, soundscape, embodiment. An important discussion develops around the sense of authenticity, which is connected to a multiplicity of rational, emotional, individual, and social factors. Essential preconditions are the good quality of digitisation and the reliability of virtual reconstructions of lost or fragmented contexts, whose criteria are shortly summarized by the author. Besides, the user-centered approach is closely connected to target audience profiling, where traditional methods are complemented and exponentially enhanced by artificial intelligence which is revolutionising the field of cultural marketing. The Use of AI in the Cultural Heritage and in Museums Sector are discussed, considering a wide range of activities and applications, including a reflection on opportunities, threats and ethical issues.

Section 3, Results, presents some case studies in whose development the author was actively involved. They have been chosen to concretely exemplify principles and methods discussed in the previous section. Purposes, target, processes and technologies applied to each of them are shortly presented in their most meaningful aspects.

Section 4 discusses, in the light of the previous sections, how the museum should be considered as a dynamic place of evolving narration, where the visitor can live perceptual experiences that are unique and not equally repeatable outside the museum, beyond the opportunities offered by smartphone which people commonly use in their daily life to reach every kind of contents. Emphasis is placed on the design of the museum experience which must be rooted on effective integration of real collections, digital content and exhibition layout: real and digital should dialogue, to polarise the visitor’s attention and emotion on the place in which he/she is currently immersed.

Section 5, the conclusion, summaries the main content and the emerging values of this work, opening perspectives on future desirable developments and directions.

1.3. Museum, Virtual Heritage and Extended Reality

Today in most museums we can approach the objects on display almost exclusively with the aid of sight: we can look at the artifacts but we cannot touch them, not listen to the voices or sounds they hold back (think about textual or musical contents of manuscripts, or epigraphs, that remain totally unexpressed to the public, as in most cases their language or writing are difficult to decode today), we cannot perceive their smells, nor we can be aware of the artisanal processes that produced them. In most cases our approach to cultural object is still formal, tassonomic, abstract.

Nowadays, thanks to social media, the museum promotes itself as a potential centre of open cultural production, dialoguing with its audience. This phenomenon must be managed according to an open but authorial strategy, in which the museum, as a cultural and educational institution, welcomes instances and ‘stories’ proposed by its public but manages and directs them while maintaining a guiding role, envisioning and evolving new perspectives, including but not chasing the demands of its users.

The digital life of the museum cannot be exclusively linked to social media. The layered paradigms of the virtual museum [

3] can help in implementing a new digital curatorship, based on high audio-visual quality of content, aesthetic enjoyment, the creation of a continuum between the experience of the real and the virtual contents, structured storytelling, virtual and mixed reality, sensory immersion and a sense of presence within stories and environments. Multisensory solicitation can evoke, around objects or lost contexts of life, the sensorial, perceptive and symbolic dimension, which would otherwise be completely unexpressed. Through the virtual dimension lost relations between objects, ages, stories, contexts can be restored, represented and experienced. What is mostly important, in the virtual dimension, is not the objective description, the digital replica of the real artifact, but the interaction processes that can be activated, that are open, personal, and diversified [

4]. Thanks to the digital “extension”, objects and places can be usefully perceived and understood in their:

shape, eventually digitally restored;

context, through virtual reconstructions or mixed reality;

technical processes, symbolic values and social attribution of meanings, through storytelling.

A virtual heritage network is therefore a multidisciplinary and multidimensional network connecting objects, places, authors, contents, users, real worlds and virtual dimensions. Extended reality is a “continuum” where real and virtual co-exist and are combined, enhance and validate reciprocally. Multisensory communication is instrumental in increasing the accessibility to museum content as it conveys contents through multiple perceptual channels, and it can solicit inclusive, participatory, and creative audience engagement through the stimulation of ideas and emotions. Making the space alive allows to break down the isolation of the objects from the public, increase the sense of fear and wonder [

5], astonishment and empathy and ultimately encourage exchange and dialogue between people [

6]. Audio-visual, tactile, even olfactory or gustatory narration, if guided by criteria of truthfulness and historical plausibility, allow the public to feel embodied in the experience and delve deeper into a interconnection of meanings, tangible materials and symbolic values.

Storytelling is another key element in the processes of engagement and immersion in the cognitive experience. It should shape the museum space and the way of organizing and approaching the collections, fostering both intimate reflection and interactive collaborative experiences, through a variation of audiovisual languages, interaction levels, and technologies chosen to convey stories [

2].

As a public place of education and culture, the museum is inclined to favour collective communication, social sharing and exchange. The various forms of content representation, languages and technologies are usually chosen to engage groups of people. But on the other side museum should foster also intimate reflection and self-awareness. It is increasingly common to find, in the museum, a space with few seats where users can enjoy an individual experience of immersive virtual reality (VR) wearing head mounted displays, but the quality and the integration of this kind of experience into the museum pathways is still not fully convincing. If museums will be able to usefully take advantage of the challenges offered by creative languages and innovative technologies, favoring quality instead of quantity, they can become privileged guides and interprets of social demands, especially of the young generations. Therefore, privileged recipients of this contribution are museum and cultural venues curators, involved in preserving, enhancing, and protecting cultural heritage, as well as university and school students, cultural and creative industries, and in general all those people aiming at creating culturally useful, accessible, participatory experiences that generate a sense of well-being in the individual and the community.

1.4. State of the Art

The visit to the museum must offer a unique experience based on the richness and depth of the contents: collections, high quality audio-visual narration, interaction, multi-sensory immersion, embodiment, emotion, are essential elements in the creation of an experience and are the paradigms of virtual museums. But where are we now?

In Prague, on 24 August 2022, the Extraordinary General Assembly of ICOM has approved the new museum definition with 92,41%: “

A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.” [

7]. This is a more up-to-date definition of “museum”- coherent with current times and the ever-changing dynamics of the world of Culture, in comparison with the previous definition dating back to 2007: “

A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment”.

In the new definition, ethical concepts such as accessibility, inclusiveness, diversity, sustainability and community participation are underlined. The part in which the vision and the intellectual mission of museums are explained remains unchanged, understood as places of conservation, research, exhibition of artifacts.

Besides, a resolution by the 31th General Assembly of ICOM in 3-9 July 2016 in Milan, disciplined the responsibility of museums towards landscape [

8]: “

Museums are part of the landscape. They collect tangible and intangible testimonials linked to the environment. The collections forming part of their heritage cannot be explained without the landscape. Museums have a particular responsibility towards the landscape that surrounds them, urban or rural[…] The concept of Cultural Landscape incorporates not only the physical size of a territory, but also a wide range of intangible factors - from language to lifestyle; from religious belief to the different forms of social life; from technology to ways of life and production, as well as to power relations and exchanges between generations. […] Such concept encompasses soundscapes, olfactory, sensory and mental landscapes, and also the landscapes of memory and of conflict, often incorporated in places, objects, documents and images, endlessly expanding opportunities for museums to take action on cultural landscapes”. It is clear the interdisciplinary approach that museums need to adopt in their curatorial practices and multidimensional interconnection, where the link with the digital is an essential part to create global and local dimensions, new real and virtual communities.

Currently, museums and cultural venues are embracing the digital challenge with increasing confidence, but real and virtual are mostly juxtaposed in the cultural offer, separately, they do not really interact with collections. In many cases digital content offer an accessory experience, introducing the main topic of the exhibition at the beginning of the visit path or they offer additional contents like for instance interviews to the experts or documentation of contemporary artists, in the form of non-interactive movie (most of time with subtitles and without audio). Multimedia rarely is used to present simulations, tell stories and attribute meanings to the exhibited artifacts along the path of visit. The connection with the territory and the cultural landscape is still very poor. Similarly, they are rarely used to encourage interaction or stimulate creativity, astonishment in the public, or a deep contact with us ourselves, or with the artist’s concept (a part some exhibitions of contemporary art). Dialogue and interaction among users take place on social media but not in the museum space. Increasingly, museums adopt supports and arrangements to make cultural content accessible to people with physical and perceptive impairments, but these are still partial interventions.

Since 2005 the importance of the relation between heritage and human rights and democracy, as a condition for the social, cultural and economic growth of the communities, was empathized by the Convention on Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention) [

9]. In the following years many initiatives followed, in line with the Faro Convention, at international European and national levels, with an increasing attention to

accessibility. In 2019 the International Council of Museums (ICOM) presented at the 25th General Conference in Kyoto, in accordance with the Italian Ministry of Culture, the guidelines regarding accessibility [

10], inclusion and usability in museums )[

11,

12], encouraging the opportunity of creating an International Committee on Accessibility (motor, sensory and cognitive disabilities, social fragility, etc.); therefore many governments are recently supporting this issue. In December 2019 a new version of the European guideline “Accessibility requirements for Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) products and services”(EN 301549) [

13] was published, to specify functional accessibility requirements applicable to ICT products and services, to be used in public procurement in Europe. In line with these principles, in 2024 Italian National Research Council, in collaboration with the Italian Ministry of Culture and the Italian National Radio-Television (RAI), published the “Design manual for accessibility and expanded enjoyment of cultural heritage. From the functioning of the person to the functioning of cultural places” [

14]. More than thirty experts representing diverse backgrounds contributed to this work, which offers targeted guidance for the functional design of cultural venues, practical cases, and with a reasoned legal summary. The manual presents a cross-cutting design for all heritage places, which include libraries, archives, museums, monuments, and archaeological areas. The focus is on the removal of architectural, cultural, sense-perceptual and cognitive barriers in cultural places, and on the functioning of cultural places rather than on the mere analysis of the characteristics of the users attending such sites. In this context multisensory and multichannel approach in communication is recommended as essential strategy, in relation to the Universal Design principles [

15].

In museums, in particular, there is still a reluctance to combine real and virtual contents in the same experiential “frame,” probably the worry is that the contribution of the virtual might shatter the absolute meaning of the object on display, its authenticity, assaulting it with ephemeral values.

In the last years the concept of “authenticity”, as perceived in museums, has been investigated by some projects and articles [

16,

17]. Among these initiatives the PERCEIVE European project (Perceptive Enhanced Realities of Coloured Collections through AI and Virtual Experiences [

18] has studied and detailed the concept of authenticity of the experience, rather than of the authenticity of the artifact itself, with the goal to improve the design of digital applications in the field of cultural heritage. It has been evidenced as authenticity encompasses various dimensions beyond mere realism: the “Self”, the “Others” and the “World” [

19].

According to [

20,

21,

22], perception of authenticity arises when extraneous and impersonal subjects transform into something personal, intimate, touching our sphere of emotions, memories, or beliefs, and therefore involve us. In this sense authenticity is related to “identity” and genuine self-perception, at cognitive, emotional, and sensory levels. According to [

23] authenticity emerges and evolves alongside the person, growing in depth along the time. Therefore, an authentic experience is perceived as deeply personal and unique to everyone, changing over time. Vannini and Franzese in 2009 [

20] discuss how the “self” is intrinsically connected to the “others” by mean of explicit or implicit communication, external or internal, in presence or in remote, synchronous or asynchronous, what matters is the feeling to be part of a common thinking. Sharing the same system of symbolic values, or social practices, enhances the sense of belonging and therefore the sense of truthiness and authenticity.

The “world” is the external environment, the context in which the “self” is included, in this case the museum, or the cyberspace, or an extended reality made of a combination of real and digital entities. The perception of authenticity in this case is produced by the accessibility, the credibility, the realism of contents and their validation. Validation is often taken for granted and implicit when people trust the notoriety and scientific credibility of the author of the contents, or of the cultural institution that presents them, even in the absence of tangible and reasoned evidence of their origin. But validation can, and should, be also explicit, especially in the case of virtual objects and digitally reconstructed environments, as largely discussed in literature, especially in relation to virtual archaeology, virtual restoration and virtual reconstruction in cultural heritage [

17].

Multimedia productions for cultural places have greatly evolved in the last ten to fifteen years in terms of aesthetics, resolution and accuracy of graphical representations, multisensory solicitation and sensors integration. This has been made possible by the progress of methodological research and technology that have implemented hardware and software solutions that are increasingly integrated, powerful and accessible. And there is no doubt that museum managers and curators have shown a gradual openness to the potentialities of digital, partly overcoming initial resistance. Laboratories and creative industries working in these areas have therefore increased in number exponentially, but unfortunately the economic models of sustainability are still highly deficient, especially in the medium and long term. Strategies and investments in maintenance, reuse, updating of content and modernization of technologies are lacking in most part of museums.

For this reason, museums are often prudent in incorporating permanently digital technologies into their exhibitions and educational programs. Most of the initiatives are temporary and their sustainability is guaranteed in the short term. Museums often join partnerships for experimental projects led by ICT institutions or industries, mostly focused on technological aims.

In the last years new frontiers in the domain of digital metaphors, services or virtual experiences have opened to the wide public, as marketing automation, artificial intelligence (AI), metaverse, NFT, Block Chain, which further condition the perception of authenticity, generating new value chain. For instance the Artemisia project, carried out in 2022-2023 by the Italian National Research Council; Digilab - Sapienza University of Rome, and the company iComfort, and financed by Lazio Region in Italy, [

24], had the purpose to analyse the experience of visiting a museum by means of motion sensors and AI algorithms to understand the dynamics of users behaviour in relation to cultural content and architectural, organisational and didactic elements. It was a pilot study carried out in two rooms of the Museum of Rome in Palazzo Braschi, (Rome, Italy), recently renewed. Visitors’ movements, head orientation, gender, were captured in real time, by motion sensors, in a totally anonymous form. Data were processed by AI algorithms to extract paths, and the idea was to address results to cultural marketing strategies. In fact, the final aim of the project was to study the impact of the visit with respect to cognitive learning, customer satisfaction and accessibility, to provide a grid of indices for the improvement of future museum visits and an advanced cultural profiling model. The project remains in the research domain, given its experimental nature, with no application in the museum at present.

In 2018 the British Museum, the first national public museum born in the world in 1753, announced to enter the Metaverse via The Sandbox [

25], a virtual 3D world with a its own economy based on Ethereum [

26], a decentralized global software platform powered by blockchain technology. In the Sandbox the British Museum creates and offers Non-Fungible Token [

27] objects that reflect the breadth and depth of the museum’s collections and that can be acquired and collected by investors through cryptocurrency. The British Museum announced also to create its own immersive space within the online game world, to explore “new and innovative ways of sharing its collection and reaching new audiences” [

28].

Besides, the emergence of new social media and paradigms enhancing cultural interactions among people induce the creation of specific social platforms for Cultural Heritage that encourage an active participation of many stakeholders. There is an increasing request of digital frameworks open to the communities for the accessibility, study, participatory and sustainable management of cultural resources and assets.

Therefore, the user experience design in a museum, as well as the study of museum visitors, are fundamental to understand how the museum can affect people’s life and to let people feel involved, intimately and collectively, through a plurality of channels, in order to nurture a perception of authenticity. Personal expectations, intimate reactions, group identity, meaning making processes, memories enter in the experience, extending in space and time, beyond the on-site visit of the museum [

29].

We could say that today the main challenge to be faced is to create a closer synergy and interconnection between four ’actors’: the actual collections, the digital collections, the narrative and the public interactions, including different audience profiles, to create new scenarios of cultural experience that can last and evolve over time.

1.5. Key Factors of Multisensory Museums

An artwork is an artifact created by man, using any material, endowed with aesthetic characteristics, and imitating the natural or the spiritual reality. Every cultural artifact consists of a combination of materials, colors and shapes (aesthetic consistency) and in a convergence of expressive values, functions, and meanings (historical values) [

30,

31]. Art generates beauty and can arouse emotions, sensations and feelings, pervading our souls, bringing a feeling of harmony and happiness, shared by many people. However, there are many artistic languages and paradigms, and there is not a unique code of interpretation. Each artwork reflects the artist’s opinions in the social, moral, cultural, ethical or religious context of his historical period, that today can be lost or difficult to understand. The reconstruction of sensory and symbolic dimensions that are “beyond” the object’s appearance can take the visitor into the middle of a lively and powerful experience. How can this be done? Undoubtedly, multimedia technologies are the best means to convey contents related to cultural heritage, especially audio-visual, because they solicit a similar process of perception, elaboration and learning. Mixed and virtual environments allow the users to learn from experience, joining sensory-motor and interpretative faculties, perceiving, acting, even in contexts that are no longer (or not yet) materially accessible today. The alternation and the coexistence between real and virtual contents produces a cognitive anacyclosis; redundancies and differences that reinforce learning [

32]. Virtual contexts can be variously assembled, dismantled and mounted again, to understand their deeper relations; they can be desynchronized, becoming scenarios of different simulations.

The user centered approach makes the concept of “experience”, and therefore the user experience design, one of the main issues to be pursued in museums, together with content curation. Marc Hassenzahl [

33,

34] describes the user experience as a merger of perception, action, motivation and cognition, assuming close connection between actions, thoughts and emotions. In fact, he defines the experience as “an episode, a chunk of time that one went through [...] sights and sounds, feelings and thoughts, motives and actions [...] closely knitted together, stored in memory, labelled, relived and communicated to others. An experience is a story, emerging from the dialogue of a person with her or his world through action”. An experience is thus subjective, holistic, situated, dynamic, and worthwhile. It follows that contents that should be experienced must be accessible and usable, useful and original, credible and desirable, they must satisfy a need and move emotions.

Several neuroscience studies published in recent decades [

35] suggest that dreams are a form of continuous stimulation of long-term memory, throughout the course of life. A recent study of the New York University, led by the Hungarian neuroscientist György Buzsáki [

36], found that the conversion of everyday experiences into permanent memories occurs for a significant part when we sleep. Sleep therefore acts on the brain as a kind of memory wipe, useful in determining which thoughts to retain as long-term memories and which to discard. The brain reacts to certain experiences with ripples in the brain waves that are then reactivated during breaks or sleep, fixing them in memory. This research further explains the importance of the stimulation of multisensory dimension and emotions. The dream is in fact a psychic phenomenon linked to sleep and characterised by the perception of images and sounds recognised as apparently real by the dreaming subject. It is a kind of nocturnal thinking in which the utilitarian and rational pragmatism of waking life is suspended [

37,

38].

Human beings open their mind to the world through intuitive experience; sensing and emotions are fundamental in the life experience and in the self-identification process, they are the engine of knowledge and development of the individuals [

39]. Every important moment in our lives, fixed in our memory, has been marked by emotions. “Sensing” a cultural context means also the capacity to enter in contact with those elements that let us “recognize” something and move our emotions. W. Shakespeare himself said: “We are made of the same substance as dreams, and in the space and time of a dream is gathered our short life” (W. Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act IV, Scene I, 1623), [

40]. When we are embodied in a mixed reality or a virtual environment, engaged in audiovisual storytelling, maybe adopting gamification metaphors, dealing with spaces, ages and stories distant from our everyday life, we live an imaginative status.

But which are the key elements to be promoted in a multisensory museum to create a credible and deep experience? According to the author’s experience, these key elements can be summarised as follows.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Narration

Usually museum curators prefer to be “neutral” regarding the artifacts, and they avoid telling stories or suggesting the visitors anything else beyond the pure evidence.

In the field of Cultural Heritage, visualization usually aims at analyzing what is still existing and observable. Unfortunately, avoiding interpretations of lacking context is not a neutral choice: if a visitor is left alone, without interpretation and “reconstruction”, even if hypothetical, he/she will deduce even false and erroneous significance.

Learning does not arise simply from our reasoning, but also through curiosity, engagement, interest and attention; in one word, through motivation. In this process emotions play a crucial role, stimulating a feeling of self-identification, appropriation and elaboration of the meaning. Indeed, many surveys on user experience in museums [

41,

42], especially referred to the use of interactive digital applications characterized by technological innovation, have evidenced the crucial role of narration in this process. Narration, in fact, is more powerful than pure description. When using narration, evocation or even dramatization, objects become the occasional points where history “coagulates”, creating an expectation in the visitors. Narration emphasises relationships, individual perspectives, variations, liveliness, empathy, and emotions connecting elements within the story, even in unpredictable ways and it draws up a specific space-time dimension [

43,

44]. Storytelling can stimulate the ability to reflect and bring out new thoughts, e.g., through reference to personal, family or popular facts, it can activate unexpected stimuli, provocations, or playful dynamics.

In a multisensory museum narration is not limited to a written or an oral text. It is referred to an expressive unity where many factors converge: oral performance/recitation, layout, visual mood, soundscape, camera movements, lighting, rhythms, smell and taste (although the latter two senses are not yet highly represented in cultural venues and in digital media in general). It is evident how important languages are in generating emotion, involvement and well-being.

In the creation of a narrative, certain and circumstantial contents regarding the artifact will be combined with plausible and probable ones, pertinent to its cultural context. Usually, the story construction is a long and collective process carried out by curators and creatives, which continues to be improved and reshaped until the final production: once the historical or archaeological information has been acquired, a process of synthesis begins, aimed at distilling the essence. Some messages are made explicit, others implicit or subliminal [

45]. Through storytelling museums can propose a “visual drama” beyond what we can see, becoming scenarios of different simulations [

46].

2.2. Interaction

If the objective is to convey educational, scientifically correct and plausible content, while at the same time arousing a strong conceptual and emotional involvement in visitors, interaction also assumes a role of great importance in making the user feel decisive in the development of the experience and in the construction of the story. As early as the late 1960s, the American pedagogue Edgar Dale demonstrated that content acquired through interactive experiences settles in our minds to a much greater extent than content of which we are passive recipients [

47].

Interactions in a museum are multiple: between the user and the space, between people, between the user and the collections, between the user and technological devices, between the user and the digital content. This complex frame translates into many behaviours and cognitive dimensions that determine actions and emotions. It is therefore necessary to find a good balance between free interaction and guided experience, to optimise the effectiveness of cultural transmission and both personal and collective stimuli.

Interaction can be active or passive. It is active when it is explicit, e.g., verbal with other users, or when technological devices must be used to activate content or events, or when people act together and co-create a common experience within a real or digital scenario. On the other hand, interaction is passive when one’s mind and feelings are stimulated by a suggestive story or situation, the vision of a beautiful picture or the listening to an evocative sound, which trigger associations of ideas, cognitive excitement. This applies to each of our five senses. Clearly, all perceptions and interactions are open to subjective interpretation and therefore the experience differs from person to person. To make the perceptual and interactive experience positive for most people, it is necessary to make use of usability principles recognised as shared by psychologists and neuroscientists [

48] and good practices in user experience design [

49]. Therefore, interaction implies a good visual design and physical affordances. Thus, the concept of “affordance” is fundamental because it leads us towards the attribution of functionalities to real and digital artefacts. The psychologist Gibson [

50,

51] defined “affordances” all the “action possibilities” latent in the environment, objectively measurable and independent from the individual’s ability to recognize them, but always in relation to agents and therefore dependent on their capabilities. According to Gibson what we perceive when we look at objects are mainly their affordances, not their dimensions and properties because the physical aspect of objects allows us to understand the principles of their functionalities. Consequently, the concept of affordance is related to the concepts of perception, usability, design, interface, interaction, shape, colour, interpretation, embodiment.

In the case of digital content and applications, active interaction should not be unnecessary and strenuous for users; instead, it should be calibrated for various types of users, confident or not with interactive technologies and interfaces. To achieve the greatest naturalness of behaviour and emotional involvement, interaction interfaces should be as close as possible to those of the real world, engaging primarily sensorimotor skills. A positive impact has indeed been observed in the applications of gesture-based interaction [

52,

53] in which the visitor must perform actual actions with the body (pointing, running, jumping, grasping...) and not symbolic actions such as those performed through a device–based system, like a joystick or a game console. Several surveys conducted on museum audiences have shown that the interaction with a digital application through the body gestures, in which the user finds himself/herself at the centre of a ’performative’ space, immediately generates in him/her (and in the passive onlookers as well) the impression of being involved in a playful situation, unusual within a museum. The experience is therefore mostly undertaken and lived with enthusiasm, and even difficulties do not generate excessive frustration [

46,

54].

2.3. Progressive Focus on Content

With the mind and senses human beings try to approximate the reality behind the visible appearance of things. The interior of the images transforms with the interest of the perceiver: attribution of meanings grows, and memories and personal creative dimensions are associated with them [. The experience gradually becomes deeper and more authentic. In the extended reality of multisensory museums, the digital content associated with an object (or a group of objects) can intensify and evolve as the user retains and focuses his/her attention on it, as if to penetrate it with his/her mind and feeling.

The evolution of the contents will proceed through various steps, depending on the time of interaction, passive or active, of the user with the object. In the case of passive interaction, the persistence of the user’s position in proximity of the object, or the placing of his/her hand on a sensitive surface, or the exploratory movement of the pupil with respect to the image space, will be sufficient to make the object react: this persistence of attention leads the object to manifest itself in the progressive levels of interiority.

These levels can be for instance:

the object is identified and made readable, e.g., through the virtual restoration of the form, if it is compromised;

the object is shown in its original context (built or natural), as well as the landscape associated to its original location;

the object’s practical or symbolic use is represented, its meaning and the message it conveyed;

the constituent material and the execution techniques are shown, in a possible journey from macro to micro;

the invisible contents, hidden beneath its surface, are revealed, as censures, preparatory traits, pentimenti;

the economic and symbolic value of the object is highlighted, its uniqueness compared to other similar objects;

the contexts, territories, and cultures it came into contact with, during its journey in time and space, are revealed, the different meanings and values with which it was invested;

the signs and traumas that the passage of time has imprinted on the object are highlighted, its state of preservation and the events that have occurred;

the literary, prosaic, epic, poetic or dramaturgical memories related to the object are evoked;

other objects presenting parallels and similarities in form, meaning or value, are shown, also belonging to other cultures.

In a multisensory museum, the insight of content is expressed in audio-visual form, through the evolution of multimedia or virtual events, but also through the changing of environmental parameters, such as the intensity and colour of the light illuminating the object, olfactory stimuli, coherently with the content that is gradually manifested.

Sound participates in this progression by becoming from descriptive to evocative, gradually delving deeper into timbres and transforming or distorting harmonies.

Images and narratives for each level should be very concise and essential, the message is conveyed in evocative manner. Content develops vertically through the depth levels of which the exhibited object stays on the top, rather than being developed horizontally with too much information on one level. This approach can help the visitor to keep the attention alive and at the same time it keeps duration of the experience limited.

The object becomes alive, multi-sensory, multi-modal. It activates in the visitor/traveler an inner psychic experience, arousing thoughts, memories, fears, dreams, a sense of wonder. Thus, understanding and remembrance are strengthened.

Multimedia content can thus be used to reconfigure the map of the museum in which they are inserted in terms of attractiveness of objects, rooms, and paths. In fact, they can influence dwell times, the degree of collectivity of the experience and the level of interaction and social exchange.

2.4. Media Convergence and Combination

The attempt to reconcile traditionally linear storytelling and interaction, real and digital content in museum spaces, free exploration and guided experience, motivating and involving the public, necessarily involves a convergence of languages. Virtual reality meets with theatre and cinema, with the paradigms of video games, with holographic techniques, mixed reality, psychoacoustics and acoustic studies. Thus, the hybridisation of media is an exciting and constantly evolving domain of experimentation.

During the museum visit digital media should dialogue with the real spaces as far as possible: even when applying gamification techniques for public engagement, the game tasks should encourage players to search for the solution in the museum spaces and among the collections (as it happens, for instance, in the classic treasure hunt) and not confine the game’s dynamics and actions solely to the digital environment.

2.5. Social and Intimate Dimensions

Dialogue is a key component in the perception of authenticity and commonly the museum communication is addressed to a community of persons.

The desire to share expectations, thoughts, emotions and reaction with other persons, before, during and after the visit, contributes to the community building process.

However, dialogue can be also intimate with oneself, and it can determine in the desire to experience personal choices, actions, being true to oneself and independently from societal conditioning. For this reason, alongside the social dimension, it is important that the cultural venue succeeds in conveying moments of intimate and personal reflection, of deep contact with the artwork. Spaces must support the transition to this dimension of recollection. The alternation between intimate and collective dimensions also implies a variation of the optimal duration of multimedia contents dislocated in the museum. Of course, the duration of an application characterized by active interaction also varies according to the level of technological ability of the user. Especially for multimedia content provided in presence of the collections, along the visiting paths, it is convenient to keep the duration short and the active interaction very low, to avoid bottlenecks that could impede the visitor’s flow. Even technological devices can be light, as for instance personal mobile devices, tablet, screen or projection mapping beside or onto the exhibited object. The holographic showcase, as implemented in the CEMEC (Connecting Early Medieval European Collections) European project, as a mixed reality environment containing the real artifact inside [

55], proved to be excellent solution to make the museum object alive and capture the visitor’s attention and enjoyment, especially if storytelling is evocative and not purely descriptive. But in the meantime, it is useful to create a spatial and thematic connection among the different multimedia stations, so to enrich the perception of the development of the story linking the different artifacts.

On the other side, solitary, intimate and reflective experiences can benefit of a dedicated space where the user can stop without pressure. In this case interaction, active or passive, can be more sophisticated and challenging.

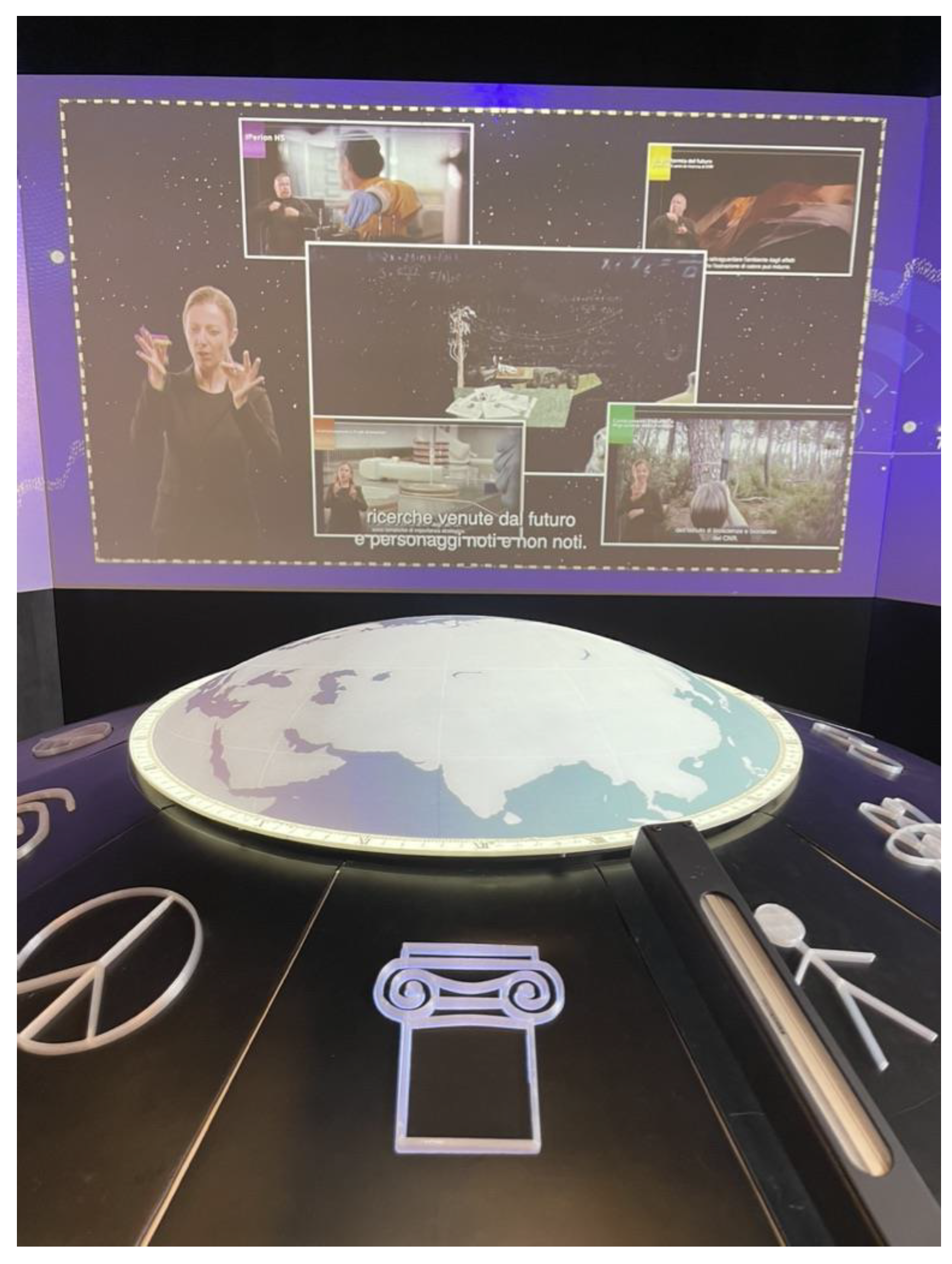

Technologies that foster solipsistic, embodied and multisensory experience of perception will be preferred. For instance, the user can enter an immersive virtual environment, can use tangible interface to interact with smart objects integrating sensors that activate stories or multimedia events projected in the space around. Cave, head mounted display, powered exoskeleton can make contents more powerful and memorable, enhancing the sense of fear and wonder.

2.6. Mixed Reality

Mixed reality and phygital experiences are the most powerful and the most difficult to implement in a museum because they potentially bring communication at its fullest expression, not only resorting to visual media but potentially involving all senses, like sound, touch, smell, taste, even if in museums these latter two are still absent.

However, they require a respectful, credible and efficacious balance between real collections and virtual contents.

Extended reality is understood here in a broad sense, as the coexistence of real and digital content in the same experiential space. The objects in the collection, the stories and values they express, are made explicit and enriched through digital applications; conversely, the virtual contents are substantiated and reinforced by the presence of the original objects, in a reciprocal dialogue. This alternation, or combination, produces a cognitive anacyclosis that enriches and consolidates understanding and knowledge. The term ’extended reality’ therefore does not necessarily refer to systems in which the virtual content is mapped precisely onto the real content, as is the case with augmented reality or mixed reality.

Mixed reality (MR) is intended as not only a combination, but as and overlapping and collimation of real and digital content in the same ’scenic’ space, so to produce a new phygital environment where real and virtual interact coherently in the space (also in real time) and are perceived as a “continuum”. According to Milgram and Kishino [

56], MR includes both “augmented reality”, where digital information and virtual objects give more meaning to real-world scenarios, and “augmented virtuality”, where real objects augment the content of artificial computer-generated scenarios.

In a MR environment, the accuracy and consistency of the overlap between real and virtual content is a crucial condition to make the perception understandable and credible. A mismatch or latency would be immediately perceived by the user as disorienting and annoying. For this reason, it is not possible to disregard a preliminary topographical and volumetric survey of the real object on which the digital superimposition will intervene, to produce a 3D model on which the virtual contents will be built, to obtain a perfect correspondence of real and virtual contents in the MR scene [

55]. Obviously, the urgency of such a need depends on the type of virtual content to projected on the real objects. If it consists of textual labels, the superposition can be less rigorous than when virtual reconstructive elements are used to complete a fragmentary real object/context [

57].

There are various technologies, and technical and methodological approaches to MR. Some viewers allow the user to see through the real world (

See-through AR Display and

Monitor based AR Display). It is also possible to enjoy virtual content superimposed on reality without the use of any device that comes between the user and the physical world, as in the case of video-projection mapping [

56,

57,

58]. The choice of the device (for instance tablet or head-mounted display) influences not only the multisensory perception, the rendering quality, the interaction and embodiment but also the duration of the experience, the interface, the kind of media, the structure of contents, and the style of the narration. For instance, if the user is stationary in a fixed place along the path of visit, just rotating his/her gaze around him, a simpler technology with an efficient geo-localization and orientation system is sufficient. Along the path of visit, a good solution is to mark fixed points of interest in the real space where the visitor can stop and enjoy short mixed reality experiences. Storytelling should be very concise to make the experience meaningful without being redundant and forcing the user to take time out, as the mind is active on many tasks, but also to avoid queues of visitors.

If the augmented or mixed reality experience takes place on the move, the user will plausibly not use an immersive viewer but will live the experience through a ‘window’-monitor display, for instance a smartphone or a tablet. Motion tracking applied to immersive devices, is an option that can enrich the sense of immersion and presence, but, along the main path of visit in a museum, it can be difficult to manage. Moreover, not all users who wear immersive such devices react positively to the solicitation of motion tracking – it also depends on the technical efficiency with which it is implemented – and for some of them it could even determine disturbance and vertigo. Hand controllers are often difficult to be used for common visitors and a support from the museum staff is necessary. Immersive devices implementing motion tracking require the user a longer adaptation time and therefore they can be used, more comfortably, in dedicated spaces. On the move, tracking the exact correspondence between real and virtual content is much more complex to manage also in terms of technological and technical implementation. The domain of cutting-edge immersive technologies of MR is very challenging from a research point of view, but not easily sustainable in museums, especially if they are proposed as permanent technological infrastructure. In fact, most people are not able to use them autonomously and often need the museum staff support, and even the powerful technological apparatus need a daily maintenance that usually the museums are still not able to guarantee.

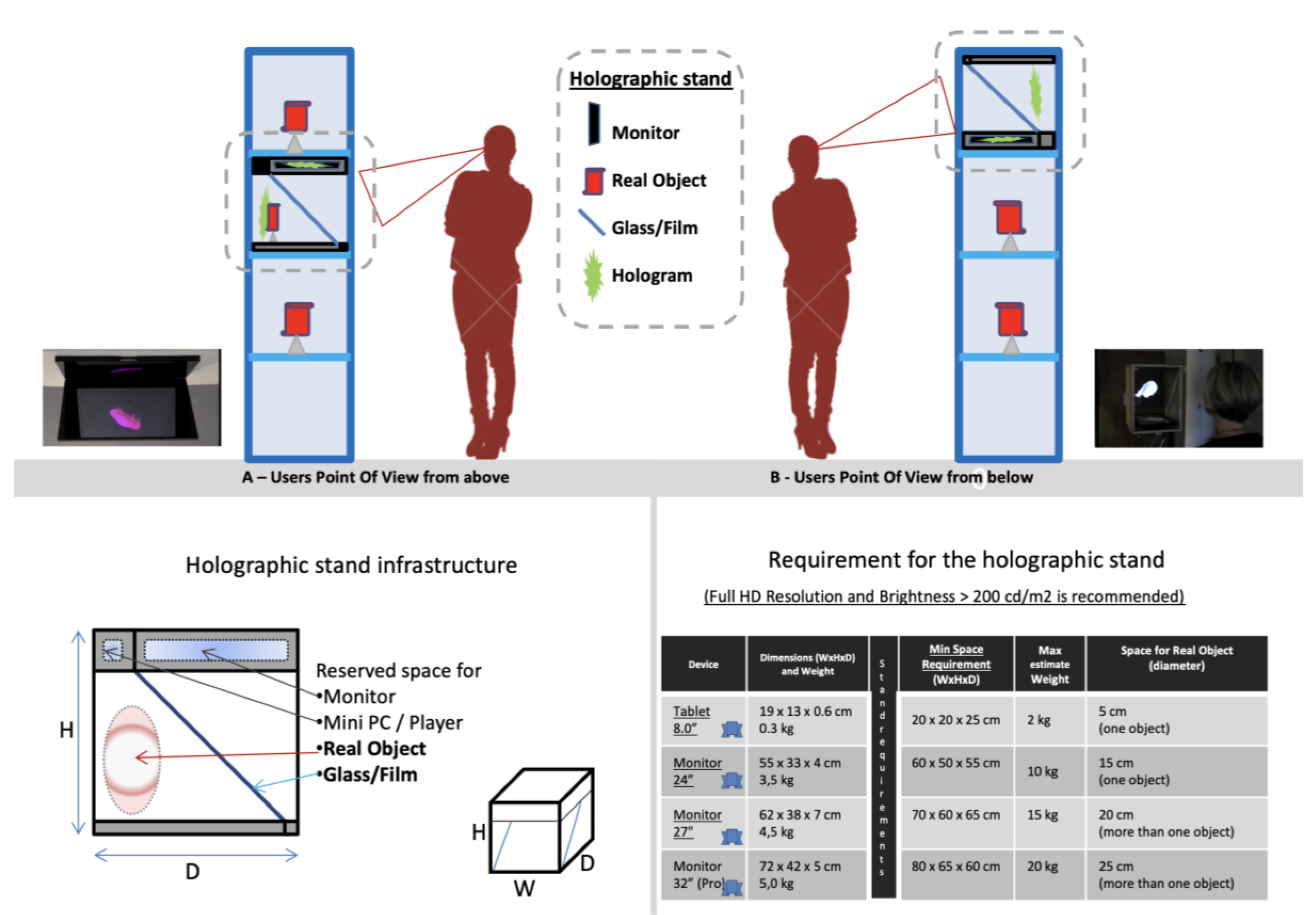

The holographic showcase (

Figure 1) is an example of non-immersive “see-through AR display”. These systems are equipped with semi-transparent displays that allow a direct view of the world around them. The holographic showcase usually proposed in museums is based on the Pepper’s Ghost effect [

59], whereby the augmented content, enriching the real object exhibited inside, is projected by an ’invisible’ device (a monitor or a projector) placed above the object and reflected by a transparent panel tilted at 45° [

55].

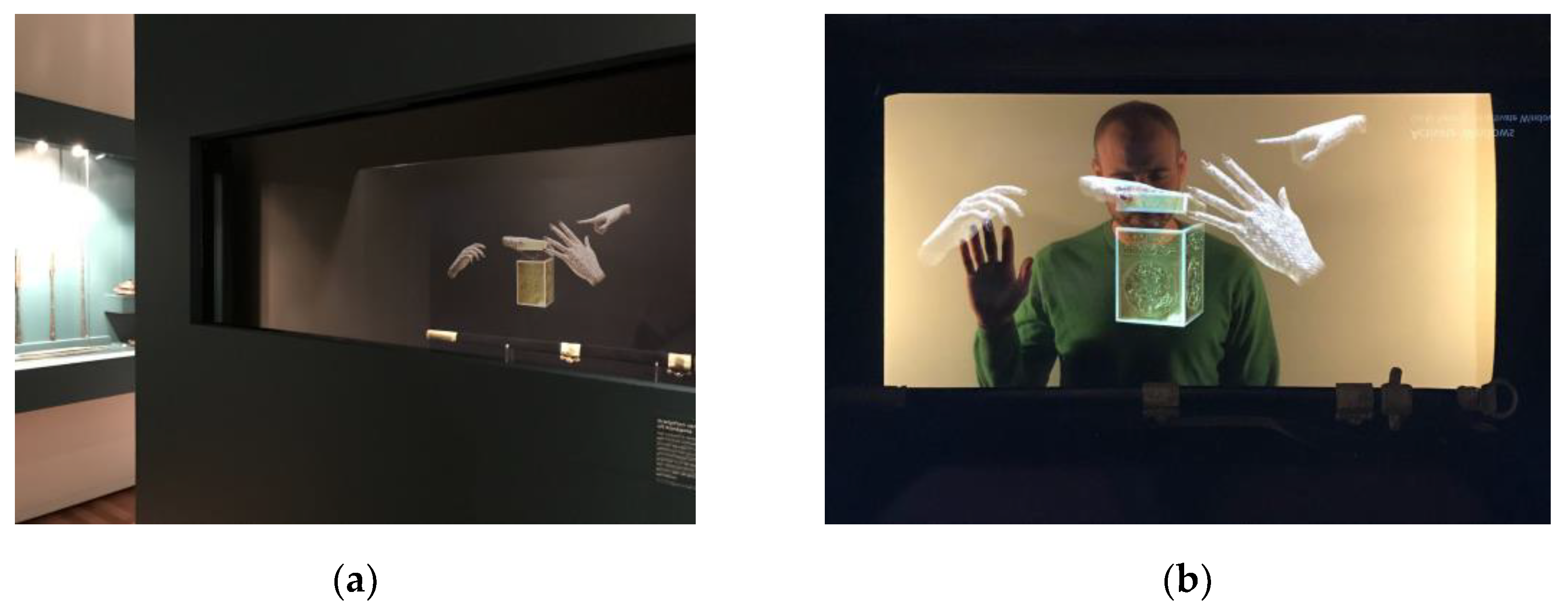

A large holographic showcase gives a small group of people the opportunity to stand comfortably in front of it. A smaller one encourages the intimate experience of the individual user. Furthermore, the holographic showcase based on the Pepper’s Ghost effect, if closed on the back by a transparent glass or plexiglass panel, allows the visitor to view the object from the rear, without perceiving the holographic effect (

Figure 2). In this way, the installation performs a dual function: it is a holographic showcase on the front side and a canonical showcase on the back side. In terms of attractiveness and educational impact, the holographic showcase is an efficacious, easy and robust technology, sustainable in museums in the long term.

Finally, in the case of projection mapping (projector-based augmented reality), lights, images ore videos projected directly onto architectural structures or objects. This technique proved to be very effective in terms of both contextual understanding and spectacular impact. In this case, the audience does not have to wear anything and does not have to physically interact with technological devices. Usability is therefore maximised. The equipment used are professional projectors, with good brightness and resistance, whose number depends on the extension of the surfaces to be mapped. The sustainability of these technologies must be carefully evaluated, especially in the case of installations designed for repeated and prolonged use.

2.7. Authenticity and Languages

The sense of authenticity is generated by the utility and credibility, progressive deepening of content, by the evolution that ensues in the mind and feeling of the user, in relation with a self-identification process. Factors determining the sense of authenticity also include expectation and, later, sharing of the received impression.

Languages used in communication have a very significant impact on the sense of credibility and authenticity perceived by the visitors. For conformism, impersonal academic languages are traditionally associated to reliability. Descriptions with technical information do not raise any discussion, as they are considered serious and objective, even if they may not meet the criteria of full comprehensibility and contextualization. On the contrary if the same cultural message is conveyed through artistic strategies or gamification techniques, people are more inclined to doubt about its certainty and they may consider it questionable, partial, perhaps childish. Of course, the artistic or evocative approach in the communication of cultural heritage, especially within museums, contains elements of risk, as it solicits differently the tastes, expectations and educational background of the audience. Examples of such different reactions and behaviours, from the sides of both curators and visitors, were observed in the case of holographic showcase mentioned above, experimented during the CEMEC project in five European National Museums. It was a mixed reality installation based on the Pepper’s Ghost technique and containing the original object inside, where storytelling resorted to dramaturgical style to solicit sense of wonder and evoke the sensory dimensions beyond the pure formal aspect of the object. In that case storytelling used the same information given through the traditionally considered “scientific” supports (catalogues, panels and so on) and in fact it was realized together with the museum curatorial staff. However, they were told in first person, representing “spots” of real life, with characters performing actions and expressing emotions. In that case, most visitors remembered the contents transmitted in the holographic showcase by correctly answering the questions of the questionnaire provided after the experience, but a small minority expressed doubts about their credibility, judging them to be playful and childlike [

42]. It has been observed that such a difference in the public reaction depends also on the geographical location of the museum and the cultural education or attitude of visitors. It was very interesting to observe that museum curators in Centre and North Europe were more flexible and inclined to accept evoking and imaginative languages to transmit cultural meanings, while visitors demonstrated a more conservative attitude. On the contrary museum curators of South Europe seemed to be more resistant, while the visitors enthusiastically welcomed a more original and exciting language and, in all cases, they felt emotionally and cognitively involved [

42].

Authenticity, however, is not related only to contents but also to the whole experience and adopted languages. Can an experience be perceived as authentic even if one is aware that the proposed contents, or part of the contents, are imaginary or uncertain? Of course, this is possible because there is authenticity in the emotions that the story can elicit, and there is authenticity in the progressive understanding that our cognition is approaching a truth greater than the single uncertain element. In fact, an imaginary content can be used as a metaphor, as a tracker to another authentic content or concept. Living the experience alone or with others can also alter the perception of authenticity [

19].

2.8. Sense of Wonder

As mentioned above, emotional impact and a sense of presence are fundamental in the perception of authenticity, and this is true in both real and digital experiences; unpredictable and unexpected events, emotions such as surprise, sense of wonder, involvement and happiness also generate a deep sense of authenticity. The beauty of the layout, of the soundscape, the atmosphere of the surrounding environment, the evocative style of the script, or an engaging interaction offer us the opportunity to feel alive, partakers of the magic and wondering dimension that is ongoing. Triggers of the sense of wonder can be:

The unexpected, the unpredictable, the surprise

The narrative that goes beyond the boundaries of simple standardised description, both in terms of language and content and in their metaphorical presentation

Unexpected movement

Looking with eyes other than those of everyday life

The rediscovery of the poetic meaning of things and actions, beyond daily utilitarian and pragmatic attributions of meaning

Multisensory dimensions, the extended reality, phygital worlds

The sense of immanence, feeling immersed with body and mind in a real or imaginary place (embodied sensing)

The feeling of the connection among all beings and elements surrounding us

The feeling to be part of the whole

The empathy

The sense of fear

The unexpected sharing of a feeling with other persons or lives.

There are many situations that can arouse the sense of wonder, such as walking through an ancient forest; entering a bare medieval church modelled by light and flooded by the sound of an organ; being overwhelmed by the richness of colours and shapes of a surrounding pictorial decoration; entering a dark cave; listening to the call of birds; exploring the seabed; travelling back in time; looking at a historical village and being able to grasp the intangible plots of real and imaginary lives that are hidden behind marble, stone, and concrete.

In a museum, the sense of wonder springs from the development of connections with the various levels of one’s own mind, with other people, with objects, with time and territory, as if the veil that keeps things separate were to fall and their unbroken continuity were to be revealed.

It is clear how important languages and forms of representation are.

Historically the sense of wonder is considered as an important aspect of human nature, being particularly related to curiosity and the drive for intellectual exploration. Moreover, wonder can ignite an interest that goes beyond the specific experience and becomes a reason for deeper knowledge of a given reality [

60]. Wonder, according to Plato [

61] and Aristotle [

62], is at the origin of wisdom and thus philosophy.

2.9. Sound and Soundscape

Acoustic design in a multisensory museum is another key factor. Sound plays a central role in the formation and development of individual and social cultural identity; therefore, sound communication is a powerful vehicle for the representation and transmission of knowledge, for experiential involvement, on both unconscious and rational level. According to Schafer, the sound environment is the result of the interaction between sound, space, and time [

63]. But sound is also intrinsically linked to place, a cultural context, a body and mind, an emotion [

64]. Sound is therefore essential to increase the cognitive and emotional involvement of visitors. Soundscape can evoke the cultural identity and life dimension of the contexts to which the museum objects refer, providing acoustic verisimilitude to the simulated spaces (e.g., by conveying meaningful sounds, music, timbres and harmonies of traditional instruments or songs, vocal techniques), in connection with the original places where they were practiced. Such sound compositions may be the result of the application of psycho-acoustic principles (as it happens for example in cultural video games or cinema) or scientific simulations of acoustic spaces obtained through mathematical models [

65].

Various disciplines, such as archaeology, art history, anthropology, musicology, acoustemology, ethnomusicology, acoustics, architectural acoustics and archaeoacoustics are intertwined and combined in the study of sounds from the past, as shown by the interesting studies published in 2020 in the special issue of the journal Acoustics “Historical Acoustics: Relationships between People and Sound over Time”, edited by Francesco Aletta and Jian Kang [

66]. In addition, acoustic design in museums can also enhance the sense of authenticity because it strengthens the collective dimension of the experience, fostering in the audience a process of perceptual and emotional synchronisation towards the content, a common vibration, a sense of cohesion and shared meaning [

67].

All this implies that the sounds are well recorded, and that the museum is equipped with good technology for high quality audio reproduction and management. In the author’s experience, a bad audio quality immediately betrays the unprofessionalism of the audiovisual product, more so than the imperfection of image. Of course, if the audio is derived from an original historical recording, the authenticity value of the source prevails.

Unfortunately, within museums there is still resistance and a lack of attention towards audio technology. Sound and music have always been considered of minor importance, if not disturbing. Insufficient attention is paid to sound technologies for single or collective listening, and their day-to-day management. Few professionals, few investments, few infrastructures have been introduced in museums, and little research has been conducted into the acoustic design of museum spaces and sonic heritage [

68] Yet audio formats and technological solutions are manifold and can meet all the needs of audiences and curators, even with the help of sensors to control their activity and pervasiveness: stereo, dolby digital surround, mono, directional sound, and binaural. An article published in 2021 by the same author of this contribution [

65], includes a deep discussion about methodological approaches and sound technologies for museums.

Of course, the acoustic properties of the museum space, and consequently the sound design, must facilitate sense-perceptive processes, considering also the need of people with visual or hearing limited abilities, as recommended by the European guidelines “Accessibility Requirements for ICT Products and Services. EN 301549”, In this regard, to be as much inclusive as possible, audio contents should follow some basic rules: orally recited texts should be accompanied by subtitles and translations in the sign language, that users should be able to activate autonomously. Besides, audio description of visual contents should be accessible for visually impaired persons, activated by the user on a predefined specific audio channel of the device, and avoiding interference with other audio solicitations.

2.10. Tangible User Interfaces (TUI)

Tangible user interfaces, 3D prints for tactile exploration, and capacitive and tactile sensors can facilitate accessibility and engagement, and they can enrich the multisensory cultural experience. TUIs are based on the tactile perception and exploration of an object to grasp the physical properties of its surface (such as material, elasticity, viscosity, flexibility), volume, form and understand its function and meaning. The use of a replica of an original object (printed in 3D from a digital reproduction or handcrafted) is particularly useful for blind people that cannot otherwise perceive the original object, which is untouchable in most cases [

69,

70]. From many years, the National Tactile Museum Omero in Ancona (Italy), has been promoting the “the beauty of touching, of establishing an emotional relationship with things and the pleasure of contact with different materials, the joy of discovering sensory nuances, possible uses and combinations. A beauty that can be touched, a beauty that overturns all the canons of the purely visual approach to art, to rediscover a new yet primordial relationship with nature” [

71,

72,

73].

When linked to multimedia events, the tactile interface is usually equipped with sensors which recognize the user’s touch and determine a status change in the system, allowing multimedia content to be started.

The tangible interface can also consist of three-dimensional interpretation of two-dimensional pictorial works, where high, medium and low reliefs correspond to foreground and background elements in the 2D image. In the HELP European project, carried out in 2003 by the CNR in collaboration with the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa [

74], this solution was experimented to help blind users to perceive and interact with a 2D painting. The audio comment was triggered by the contact of a miniaturised three-dimensional tracer that the blind user wore on his/her finger, which tactilely ‘explored’ the form, enabling the user to mentally reconstruct the work. The audio contents were of two types: 1) sounds corresponding to the colour of the painting in that point (according to synaesthetic principles), 2) very short audio descriptions of the touched element.

However tangible interfaces are not necessarily replicas of real objects. They can also derive from creative design, as several examples of interactive installation proposed in museums can demonstrate [

75,

76,

77,

78,

79].

The technology supporting the interaction with a TUI can use two different types of sensors:

conductive paint and/or piezoelectric sensors: This electrical method involves direct contact with the object by the user. It is based on the conductivity of certain materials/pigments of which paints are made, and on so-called ‘capacitive’ sensors that can detect touch on their surface by generating a change in electrical capacitance. These solutions require a computer, a programmable input-output electronic boards equipped with microcontrollers such as Arduino or Raspberry PI [

80,

81], capacitive sensors and/or conductive paint. Objects are electrically wired to the board’s connectors to detect their capacitance. The advantage of this technique is the high sensitivity to touch, ease of operation and simultaneous use by several hands; the disadvantage is the alteration of the physical surface properties of the paint-treated object and the decay of the conductive properties of the paint over time.

Computer vision: this method [

82,

83] allows the user’s action to be intercepted even without direct contact with interactive surfaces, for example by recognising the action of a hand in a specific area. For these solutions, a computer (with higher performance than in the electrical method) and a camera equipped with an infrared depth sensor (such as Kinect, Leap Motion) are required. The advantage of this technique is that it does not alter the surface physical properties of the object, the disadvantage is the accuracy of the input, which might be slightly lower.

The result of active stimulation by the user is the reproduction of audiovisual contents, for which a monitor (or video projector), audio speakers and a scenic lighting system are required. In general, users should be facilitated by lights, lines or colours, patterns in relief circumscribing the interactive areas within which they must operate and focus their attention, making it easier for them to identify objects and interfaces.

TUIs should also be located at an appropriate height and should be easily accessible for users on wheelchair.

Information on the TUI, such as captions describing the different elements, should also be translated in Braille.

2.11. Digitisation

The sense of authenticity, in museums, is particularly relevant when dealing with digital 3D representations of real objects, in both their today and past possible appearance. In the first case an accurate and validated digitisation procedure is needed, in the second case it is important to respect criteria of reliability, truthfulness, transparency of sources and of interpretation processes that supported virtual restorations and virtual reconstructions [

84,

85].

A digital object, considered as a reproduction of a real object, represents an approximation of its form and appearance, and makes it possible to preserve its knowledge and memory even if the original gets lost, provided that this digital object is obtained through a rigorous methodology, as accurate, detailed, faithful, neutral and complete as possible.

In addition, through 3D printing techniques, a material replica can be obtained from the digital one, which can represent some of the properties of the lost original object and can be manipulated or relocated to restore a fragmented or missing context.

However, as mentioned above, by virtue of its immateriality, digitisation should not be limited to the formal approximation of an object as such. It is useful to extend the concept of digital object to that of “digital content”, i.e., an expressive unit endowed with form and meaning, that can communicate both the function, context and cultural value of the object and the information necessary to understand how the digitisation process was carried out (metadata, paradata).

The realisation of a digital model following such criteria of objectivity and truthfulness makes it possible to associate reliable integrations of form (virtual restoration), contextualisation in relation to the original place for which it was conceived (virtual reconstruction), values and meanings attributed to it throughout history (semantic characterisation, narration).

The digital twin is even more: it is a virtual simulation of a physical entity including not only the appearance and meaning but also the behaviors of the object in relation to the ecosystem. This is made possible using sensors, actuators, an internet connection and software control allowing to exchange information between the virtual (cybernetic) and physical components, to make tests, monitoring, maintenance in real time [

86]. Heritage Digital Twins are understood also as digital replicas of CH objects linked to all associated knowledge, interpretative levels, attributions of meaning, relations with other items, interactive processes and digital documentation [

87]. Digital twins can integrate the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, machine learning and data analysis. They can create digital simulation models that update and change when their physical counterparts change [

88].

These actions are highly desirable to foster in-depth knowledge and understanding of the cultural asset, useful for prevention and protection, and for valorisation addressed to the public. Digital content can thus be the starting point for learning scenarios aiming at diverse audiences. A new economy could develop thanks to shared and conscious digitisation practices, such as the creation of digital libraries and services.

The digital object, accompanied by the necessary information, can thus become part of virtual collections, enriched by storytelling, following procedures of ’loans’ between museums. Virtual collections can complement real collections already on display, complete them in cases where apparatuses or contexts are physically dismembered and scattered in several places, establish connections or comparisons among objects of various provenance but linked by a common theme.

The digital model should hopefully adopt the principle of open science, especially when the digital resource or its derivative is used for non-commercial purpose, such as study and scientific research. Digitised data could be released, even for a fee, by governmental institutions for profit purpose, for the benefit of creative cultural industries.

This scenario requires an improved curatorship able to manage the continuous renewal of the museum communication strategy.

Finally, the application of FAIR principles [

89,

90] to digital cultural heritage, shared and promoted at European level, is an essential condition for sustainable life cycle of digital resources, capable of generating new cultural, social and economic value. Data, in fact, should not only be produced, but also updated over time, shared, properly re-used, feeding the creation of new cultural content. According to this perspective, the adoption of FAIR principles is at the basis of the creation and maintenance of quality data, capable of guaranteeing an easier interaction between the actors that, in different ways, play an active and creative role in the transmission of cultural heritage.

2.12. Representing the Invisible

Digital documentation, representation and valorisation of museum artifacts of particular interest, could include both visible content and elements that are not visible, hidden in the structure or in the sub-surface levels of the artifact. This can be the case of the preparatory drawing of a painting, or elements that served to the execution process and remained incorporated in the structure, materials coming from a restoration work, or alterations resulting from censorships. The characterisation of the chemical–physical–biological nature of the materials at the different stratigraphic levels can reveal interesting information related the execution technique, the conservation history and the present state of conservation, and it helps to understand the material value of the object [

91]. This approach could be innovative, aimed at creating a multidisciplinary experience with the artifact and its production context, craft skills and workshops. All these data could be integrated in a multidimensional model of the object (a 3D model to which the fourth dimension of depth can be added and explored), taking into consideration tangible and intangible values.

For such a multidimensional model, superficial information of an artifact can be captured via laser scanner, or via photo cameras and then elaborated through structure from motion and photogrammetric techniques. Instead, invisible content associated with the sub-superficial layers can be acquired through non-invasive diagnostic techniques and sensors, such as 1) pulsed thermography, which produces images in the medium infrared range, able to reveal hidden elements or detachments beneath the surface, 2) X-ray fluorescence, 3) Raman spectroscopies, 4) hyperspectral imaging, and multi-band imaging techniques as ultraviolet, 5) Vis-NIR reflectance, 6) reflectography [

92]. These techniques are chosen and combined according to the material aspects to be investigated. Then, all the relevant information can be mapped onto the 4D model as “annotations” and as informative/semantic spots. Data interpretation and interrelations can help in the reconstruction of the complex story of the artefact. The annotated multidimensional model can then be explored through interactive installations of virtual reality or mixed reality [

92].

2.13. Virtual Reconstructions and Authenticity

A virtual reconstruction in archaeology entails a digital restitution of an artefact at the time of its creation or at its successive phases of use. However, in this domain, virtual reconstructions are approximations, tools for better understanding the past and not statements of reality [

93]. Usually they are possible reconstructions, especially when dealing with lost ancient contexts. Virtual models are just simplifications, resulting from a selection of information, useful for interpretations [

94]. A virtual reconstruction, in fact, can help scholars to understand structural solutions, working as a verification tool, and it can always be updated in the light of new discoveries.

Again, in archaeology, a virtual reconstruction is usually the result of an integration of bottom up and top down approaches: the first one refers to the digital documentation and analysis of what is still remaining on the site; se second one consists of the collection, study and interpretation of historical, iconographic, literary sources, architectural rules and proportion theories, including comparison with similar case studies [

93]. Virtual reconstructions let the public better imagine and understand the original context of the exhibited artifact, its function, value and properties, giving concreteness to abstraction. As it was assumed at the beginning of this contribution, the final goal of virtual heritage is the interaction process, the semantic value and the cognitive incitement that develop from this interaction.

Rendering techniques, contents and metadata, visualization technologies, user interface and investigation tools depend on the different audiences they are addressed to, even if they should always follow scientific consolidated criteria. The experience will be more analytical, with a focus on the structure and its elements, construction materials or executive techniques, with connection to related databases, in the case of an expert audience [

95]. On the contrary it will be more dramatised, sensory, narrative or playful, in the case of a non-expert public that must be introduced to the cultural context, the way it was used, life dimension, and historical background. In this case holistic approach and embodiment prevail over analysis, exploration tools and metaphors will be calibrated accordingly, while maintaining continuity and coherence between scientific source, knowledge and communication [

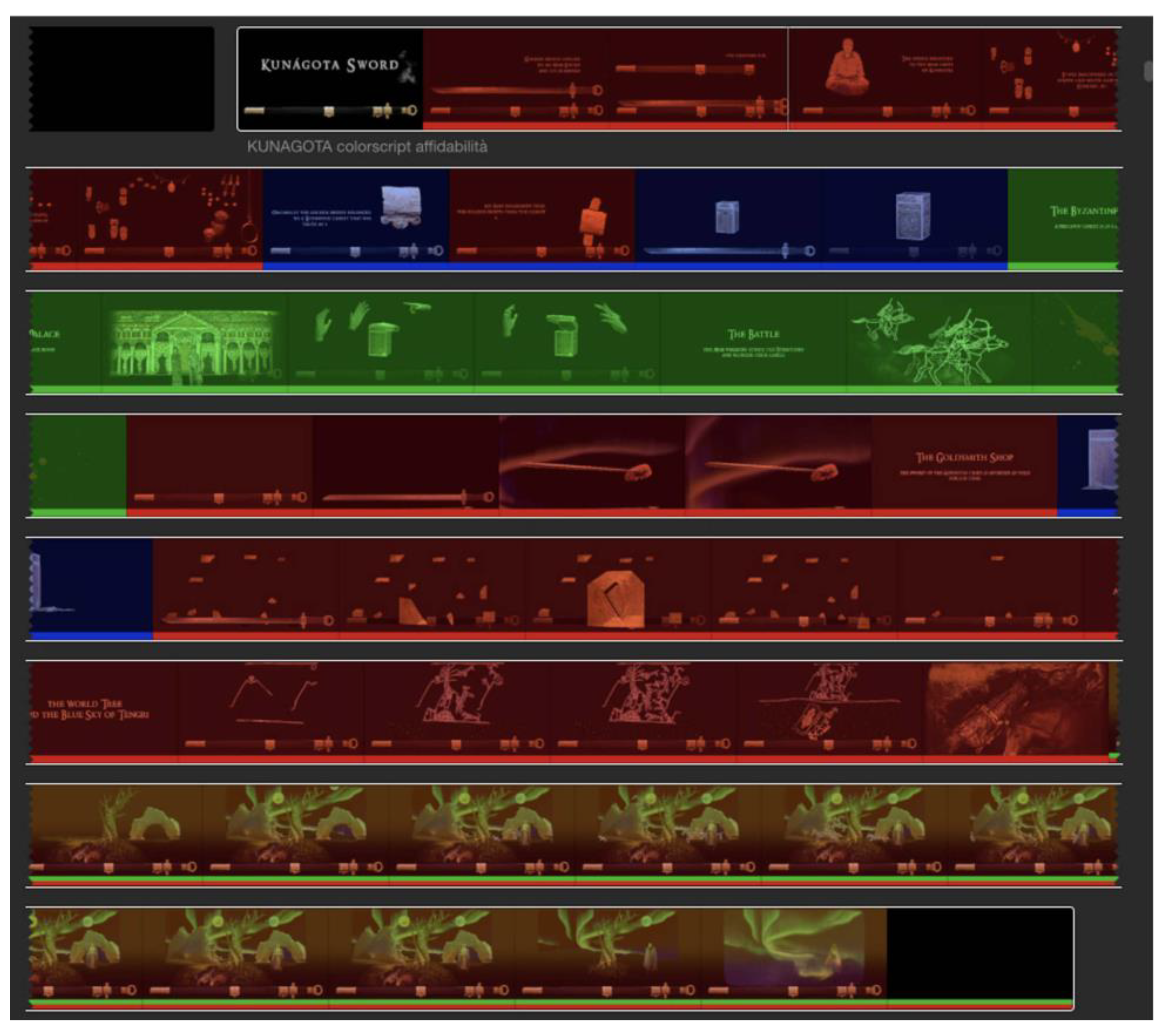

96].