Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Organization of the Paper

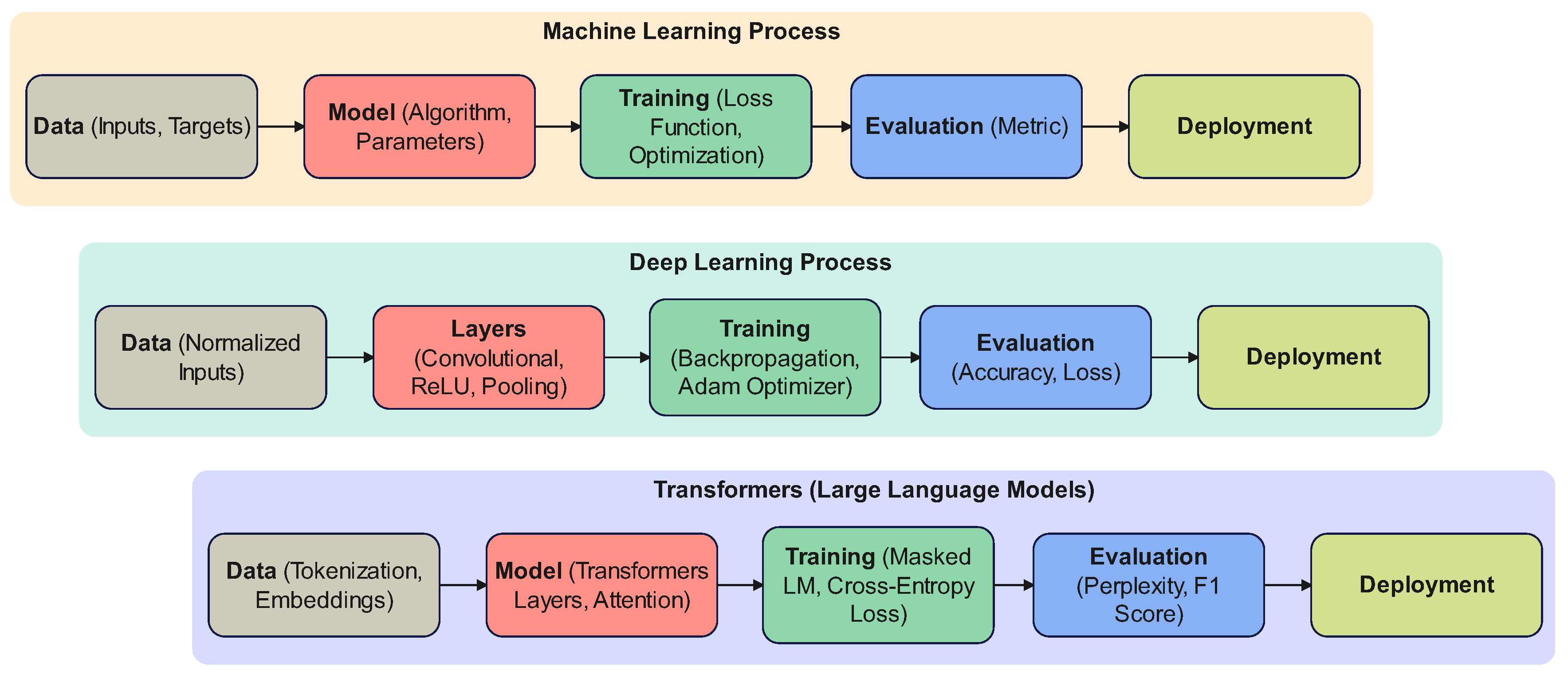

2. Machine Learning Models

2.1. Supervised Learning

2.1.1. Linear Regression

2.1.2. Logistic Regression

2.1.3. Decision Trees

2.1.4. Support Vector Machines (SVM)

2.1.5. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

2.1.6. Naive Bayes

2.1.7. Ridge Regression

2.1.8. Lasso Regression

2.1.9. Elastic Net

2.1.10. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)

2.1.11. Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA)

2.1.12. Bayesian Networks

2.1.13. Least Squares Support Vector Machines (LS-SVM)

2.2. Ensemble Learning

2.2.1. Random Forest

| Name of the Algorithm | Popularity | Mathematical Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different than Other Classifier | Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | High | A statistical method for modeling the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. | Simple to implement and interpret, good for linear relationships. | Not suitable for non-linear data, sensitive to outliers. | Directly models the relationship between variables. | Effective for linear relationships, widely used in many fields. | |

| Logistic Regression | High | Used for binary classification, predicts the probability of the default class. | Probabilistic framework, interpretable coefficients. | Assumes linear relationship between variables and log-odds, not suitable for non-linear problems. | Outputs probabilities, not just class labels. | Widely used for binary classification tasks, performs well with linear decision boundaries. | |

| Decision Trees | High | Tree-like model for decision making, splits data into subsets based on feature values. | Easy to interpret and visualize, handles non-linear relationships. | Prone to overfitting, sensitive to noisy data. | Simple and interpretable model structure. | Effective for both classification and regression tasks, popular in many applications. | |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | High | Finds the hyperplane that best separates the classes in the feature space. | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, robust to overfitting. | Computationally intensive, requires careful parameter tuning. | Maximizes margin between classes. | High accuracy in various classification tasks, especially with clear margin of separation. | |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Moderate | Classifies a sample based on the majority class among its k-nearest neighbors. | Simple and intuitive, no training phase. | Computationally expensive during prediction, sensitive to irrelevant features. | Non-parametric, makes few assumptions about the data. | Performs well with sufficient and relevant data, used in various domains. | |

| Naive Bayes | High | Probabilistic classifier based on Bayes’ theorem, assumes feature independence. | Simple and fast, works well with high-dimensional data. | Assumes independence among features, which is often not true. | Works well with small data sets and high-dimensional data. | Effective in text classification and spam detection, performs surprisingly well despite simplicity. | |

| Ridge Regression | Moderate | Extension of linear regression with L2 regularization to prevent overfitting. | Reduces model complexity, handles multicollinearity. | Can still be affected by outliers. | Regularization helps prevent overfitting. | Useful in situations with many correlated features, often performs better than linear regression. | |

| Lasso Regression | Moderate | Linear regression with L1 regularization, encourages sparsity in coefficients. | Performs feature selection, reduces model complexity. | Can discard important features if not tuned properly. | Can perform automatic feature selection. | Effective for datasets with many features, especially when some are irrelevant. | |

| Elastic Net | Moderate | Combines L1 and L2 regularization, balances between ridge and lasso regression. | Handles multicollinearity, performs feature selection. | Complex tuning process due to two regularization parameters. | Combines benefits of ridge and lasso regression. | Often outperforms both ridge and lasso when dealing with correlated features. | |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) | High | Finds a linear combination of features that best separates two or more classes. | Simple and computationally efficient, works well with normally distributed data. | Assumes normal distribution of features, equal covariance among classes. | Maximizes separation between classes. | Effective for low-dimensional data, commonly used for classification problems. | |

| Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA) | Moderate | Extension of LDA, allows for different covariance matrices for each class. | More flexible than LDA, can model more complex boundaries. | Requires more data to estimate separate covariance matrices accurately. | Allows for quadratic decision boundaries. | Effective for datasets where classes have different covariance structures. | |

| Bayesian Networks | Moderate | Probabilistic graphical model that represents a set of variables and their conditional dependencies. | Handles uncertainty, incorporates prior knowledge. | Computationally intensive for large networks. | Represents complex relationships between variables. | Effective for reasoning under uncertainty, used in various fields including bioinformatics and diagnostics. | |

| Least Squares Support Vector Machines (LS-SVM) | Moderate | Variant of SVM that uses least squares cost function, simplifies computation. | Computationally efficient, handles non-linear relationships. | Requires careful tuning of parameters. | Simplifies the quadratic optimization problem of SVM. | Comparable performance to traditional SVM, often faster to train. |

2.2.2. Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM)

2.2.3. XGBoost

2.2.4. LightGBM

2.2.5. CatBoost

2.3. AdaBoost

2.3.1. Bagging

2.3.2. Stacking

2.3.3. Voting Classifier

2.3.4. Bootstrap Aggregating (Bagging)

2.4. Unsupervised Learning

2.4.1. K-Means Clustering

2.4.2. Hierarchical Clustering

| Algo | Popularity | Math Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different than Other Classifier | Combining Algos |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | High | An ensemble of decision trees, each trained on a different subset of the data using bagging. | Reduces overfitting, handles large datasets well. | Can be computationally intensive, requires significant memory. | Uses averaging to reduce variance. | Decision Trees | |

| Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) | High | Sequentially builds models, each correcting errors of the previous one. | High predictive accuracy, handles complex data well. | Prone to overfitting if not properly tuned, requires careful parameter tuning. | Sequentially reduces errors from previous models. | Decision Trees | |

| XGBoost | High | An optimized implementation of gradient boosting with additional regularization. | Fast, efficient, and scalable, handles sparse data well. | Complex implementation, can be prone to overfitting. | Includes regularization to prevent overfitting. | Decision Trees | |

| Name of the Algorithm | Popularity | Mathematical Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different than Other Classifier | Combining Algorithm |

| LightGBM | High | A gradient boosting framework that uses tree-based learning algorithms. | Faster training, lower memory usage. | Sensitive to parameter tuning, can be less accurate if not properly tuned. | Uses histogram-based methods for efficiency. | Decision Trees | |

| CatBoost | Moderate | A gradient boosting algorithm that handles categorical features automatically. | Handles categorical data well, reduces overfitting. | Can be slower than other implementations, requires careful parameter tuning. | Automatically handles categorical variables. | Decision Trees | |

| AdaBoost | High | Combines weak learners into a strong classifier by focusing on misclassified instances. | Simple and effective, reduces bias. | Sensitive to noisy data and outliers. | Adjusts weights to focus on difficult cases. | Weak Learners (e.g., Decision Trees) | |

| Bagging | Moderate | Trains multiple models on different subsets of the data and averages their predictions. | Reduces variance and overfitting. | Can be computationally intensive, requires significant memory. | Uses bootstrapped datasets to train models. | Any Base Learner (commonly Decision Trees) | |

| Stacking | Moderate | Combines multiple models using a meta-learner to improve predictive performance. | Can achieve high predictive performance, flexible. | Complex to implement, risk of overfitting. | Uses a meta-learner to combine base models. | Multiple Base Learners (e.g., Decision Trees, SVMs, Neural Networks) | |

| Voting Classifier | Moderate | Combines predictions from multiple models using majority voting for classification. | Simple to implement, can improve performance. | May not always outperform the best individual model. | Uses majority voting for final prediction. | Multiple Base Learners | |

| Bootstrap Aggregating (Bagging) | Moderate | Trains multiple models on different bootstrapped subsets of the data. | Reduces variance and overfitting. | Can be computationally intensive, requires significant memory. | Uses bootstrapped datasets to train models. | Any Base Learner (commonly Decision Trees) |

2.4.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.4.4. Independent Component Analysis (ICA)

2.4.5. Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM)

2.4.6. Self-Organizing Maps (SOMs)

2.5. Reinforcement Learning

2.5.1. Q-Learning

| Name of the Algorithm | Popularity | Mathematical Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different than Other Methods | Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Means Clustering | High | Partitions data into k clusters, where each data point belongs to the cluster with the nearest mean. | Simple and fast, easy to understand. | Requires specifying the number of clusters, sensitive to initial seed selection. | Iteratively minimizes the variance within clusters. | Widely used for clustering tasks, performs well with large datasets. | |

| Hierarchical Clustering | Moderate | N/A | Builds a hierarchy of clusters using either a top-down (divisive) or bottom-up (agglomerative) approach. | Does not require specifying the number of clusters, produces a dendrogram for visualization. | Computationally intensive for large datasets, sensitive to noise. | Creates a nested hierarchy of clusters. | Effective for smaller datasets, commonly used in bioinformatics. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | High | Reduces dimensionality by projecting data onto the directions (principal components) that maximize variance. | Reduces complexity, helps in visualization. | Assumes linear relationships, can lose interpretability. | Finds the directions of maximum variance in the data. | Widely used for dimensionality reduction, feature extraction. | |

| Name of the Algorithm | Popularity | Mathematical Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different than Other Methods | Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Moderate | Separates a multivariate signal into additive, independent components. | Effective for blind source separation, identifies underlying factors. | Requires the number of components to be specified, assumes components are statistically independent. | Separates mixed signals into independent sources. | Effective in signal processing, notably used in EEG data analysis. | |

| Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) | Moderate | Assumes data is generated from a mixture of several Gaussian distributions. | Can model complex distributions, soft clustering. | Can be computationally intensive, sensitive to initialization. | Uses probabilistic approach to assign data points to clusters. | Effective for clustering and density estimation, performs well with flexible cluster shapes. | |

| Self-Organizing Maps (SOMs) | Low | N/A | Projects high-dimensional data onto a lower-dimensional grid while preserving the topological structure. | Good for visualization, handles non-linear relationships. | Requires careful tuning of parameters, can be slow to train. | Preserves the topological properties of the input space. | Used for visualization and clustering, effective for exploratory data analysis. |

2.5.2. Deep Q-Networks (DQN)

- Experience Replay: Transitions are stored in a replay buffer and sampled randomly during training, breaking the temporal correlation between consecutive transitions.

- Target Network: A separate target network with fixed parameters is used to compute the target , reducing the risk of divergence.

2.5.3. Policy Gradient Methods

2.5.4. Policy Gradient Methods

| Algo | Popularity | Math Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different than Other Methods | Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q-Learning | High | Model-free reinforcement learning algorithm that aims to learn the value of an action in a particular state. | Simple and effective for small state spaces. | Can be slow to converge, especially in large state spaces. | Learns optimal policy directly, without needing a model of the environment. | Widely used in various applications, performs well for discrete action spaces. | |

| Deep Q-Networks (DQN) | High | Combines Q-learning with deep neural networks to handle large state spaces. | Can handle high-dimensional input spaces, like images. | Requires large amounts of data and computational resources, can be unstable. | Uses experience replay and target networks to stabilize training. | Achieved state-of-the-art performance in many Atari games, widely adopted in deep reinforcement learning research. | |

| Policy Gradient Methods | Moderate | Directly optimizes the policy by gradient ascent, suitable for continuous action spaces. | Can learn stochastic policies, useful for environments with continuous actions. | High variance in gradient estimates, requires careful tuning of hyperparameters. | Optimizes the policy directly rather than estimating value functions. | Effective in continuous control tasks, widely used in robotics and game playing. | |

| Name of the Algorithm | Popularity | Mathematical Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different than Other Methods | Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

| Actor-Critic Methods | Moderate | Combines policy gradient (actor) with value function approximation (critic) to reduce variance. | Reduces variance in gradient estimates, leading to more stable training. | Can be complex to implement and tune, still sensitive to hyperparameters. | Uses separate models for policy and value function, leveraging their strengths. | Widely used in deep reinforcement learning, performs well in a variety of tasks, including continuous control and discrete action spaces. |

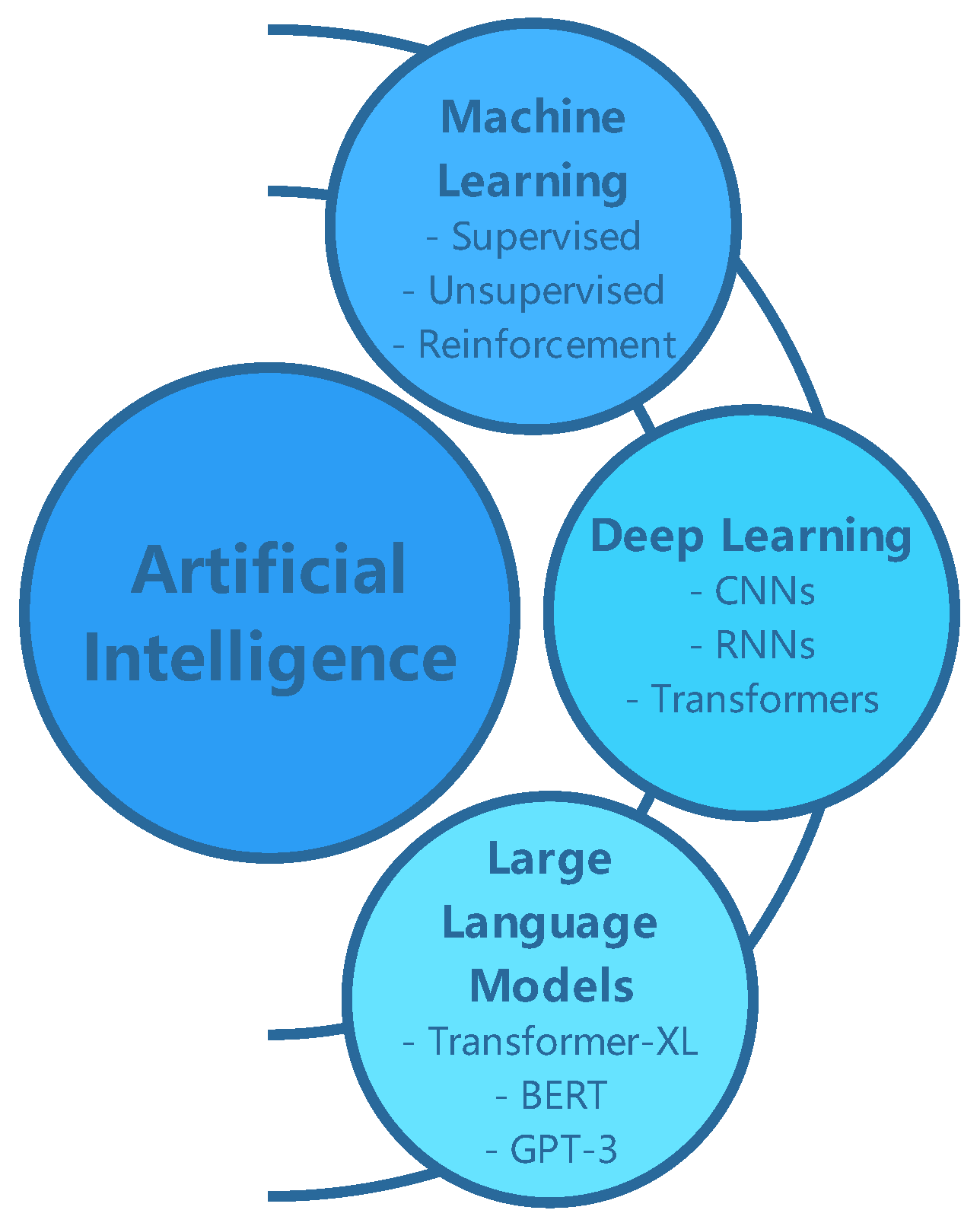

3. Deep Learning Models

3.1. Feedforward Neural Network (FFNN)

3.1.1. Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP)

3.2. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

3.2.1. LeNet

3.2.2. AlexNet

3.2.3. VGGNet

3.2.4. GoogLeNet

3.2.5. ResNet

3.2.6. DenseNet

3.3. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN)

3.3.1. Vanilla RNN

3.3.2. Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM)

3.3.3. Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)

3.4. Transformers

3.4.1. BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers)

3.4.2. GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer)

3.4.3. T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer)

3.4.4. XLNet

3.4.5. PaLM (Pathways Language Model)

3.5. Multi-Modal Transformers

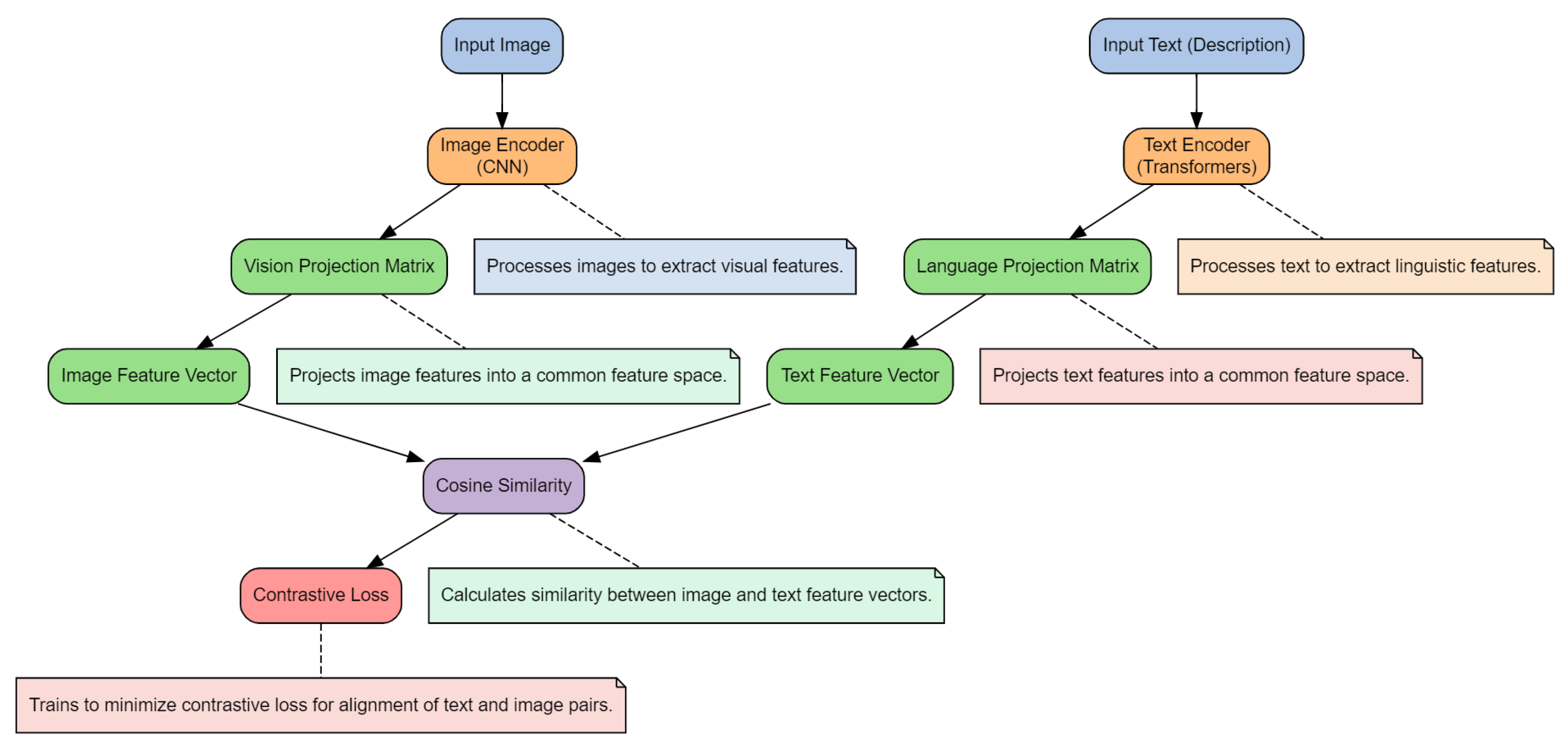

3.5.1. CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pretraining)

3.5.2. DALL-E

3.5.3. VisualBERT

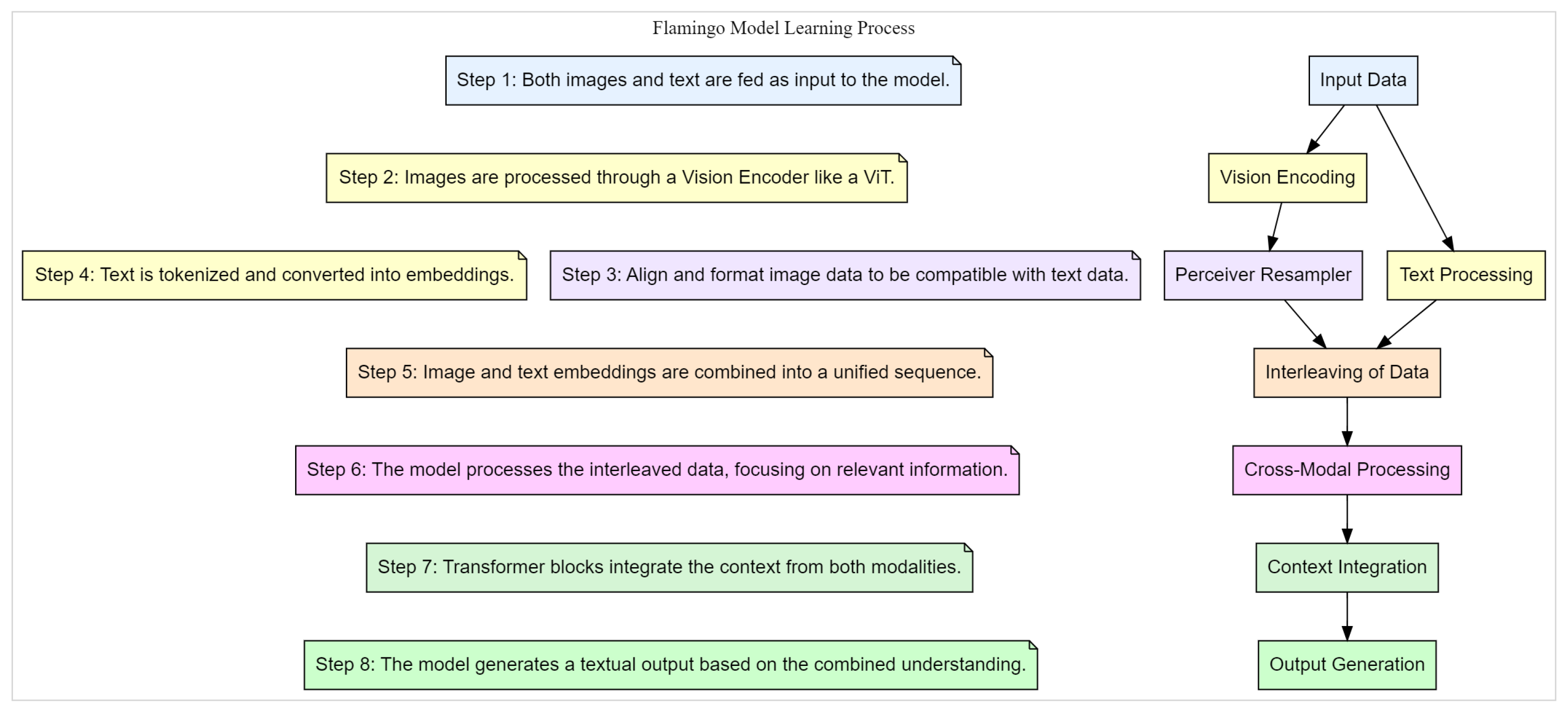

3.5.4. Flamingo

3.5.5. FLAVA (A Foundational Model for Language and Vision)

3.6. Generative Models

3.6.1. Autoencoders

3.6.2. Variational Autoencoders (VAE)

3.6.3. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

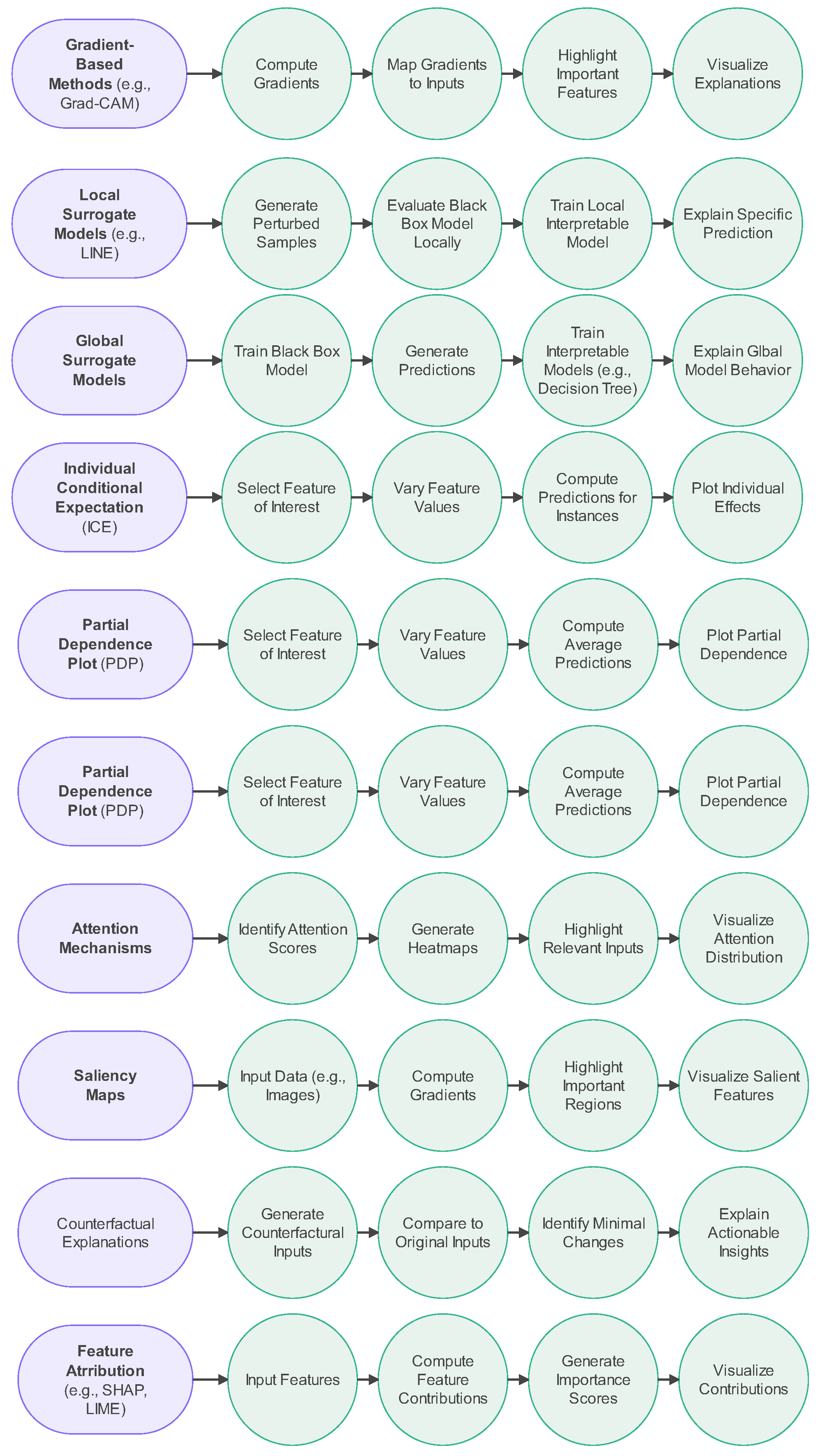

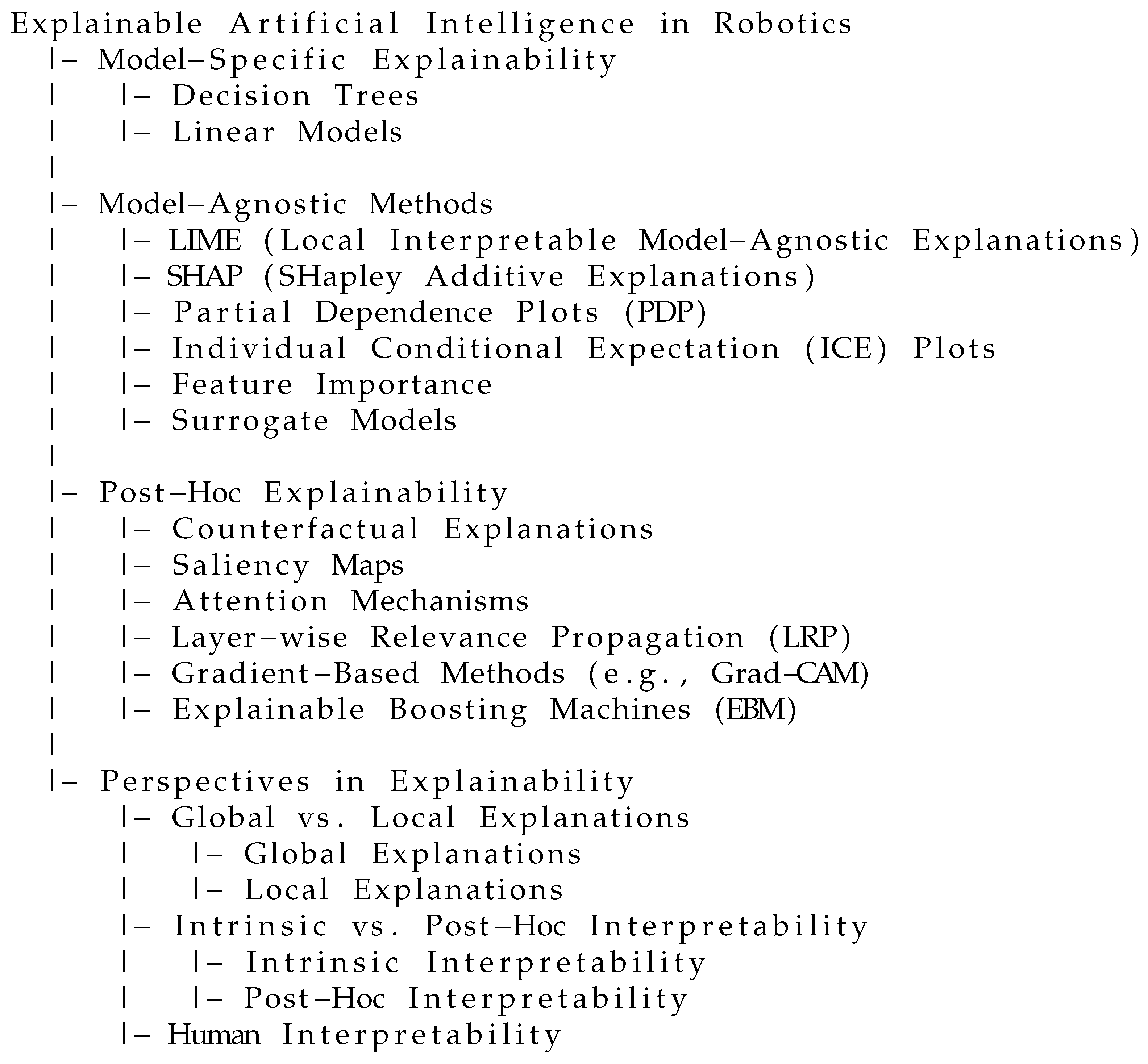

4. Explainable AI Techniques

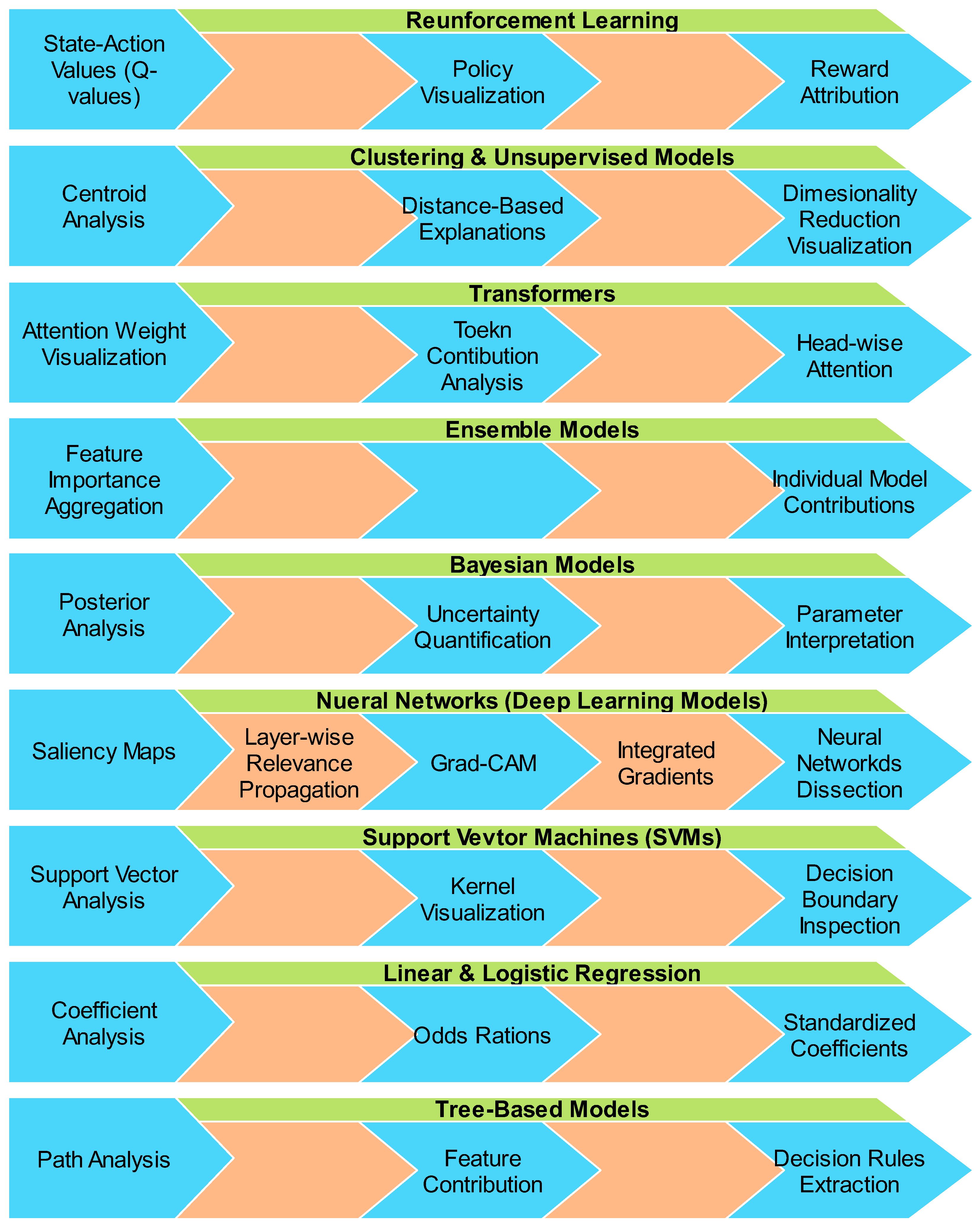

4.1. Model-Specific Explainability

- Decision Trees: Decision trees are inherently interpretable models that work by breaking down data into simple decision rules, leading to a final outcome. Each path from the root to a leaf represents a series of decisions, making it easy for users to follow and understand the reasoning behind a prediction. However, decision trees may overfit to training data, which can reduce their reliability on unseen data [4].

- Linear Models: Linear models are straightforward, as they quantify the relationship between input variables and the output through coefficients. The size of the coefficient indicates how much influence each variable has on the outcome. While linear models are easy to interpret, they assume linear relationships and may miss complex, nonlinear patterns [2].

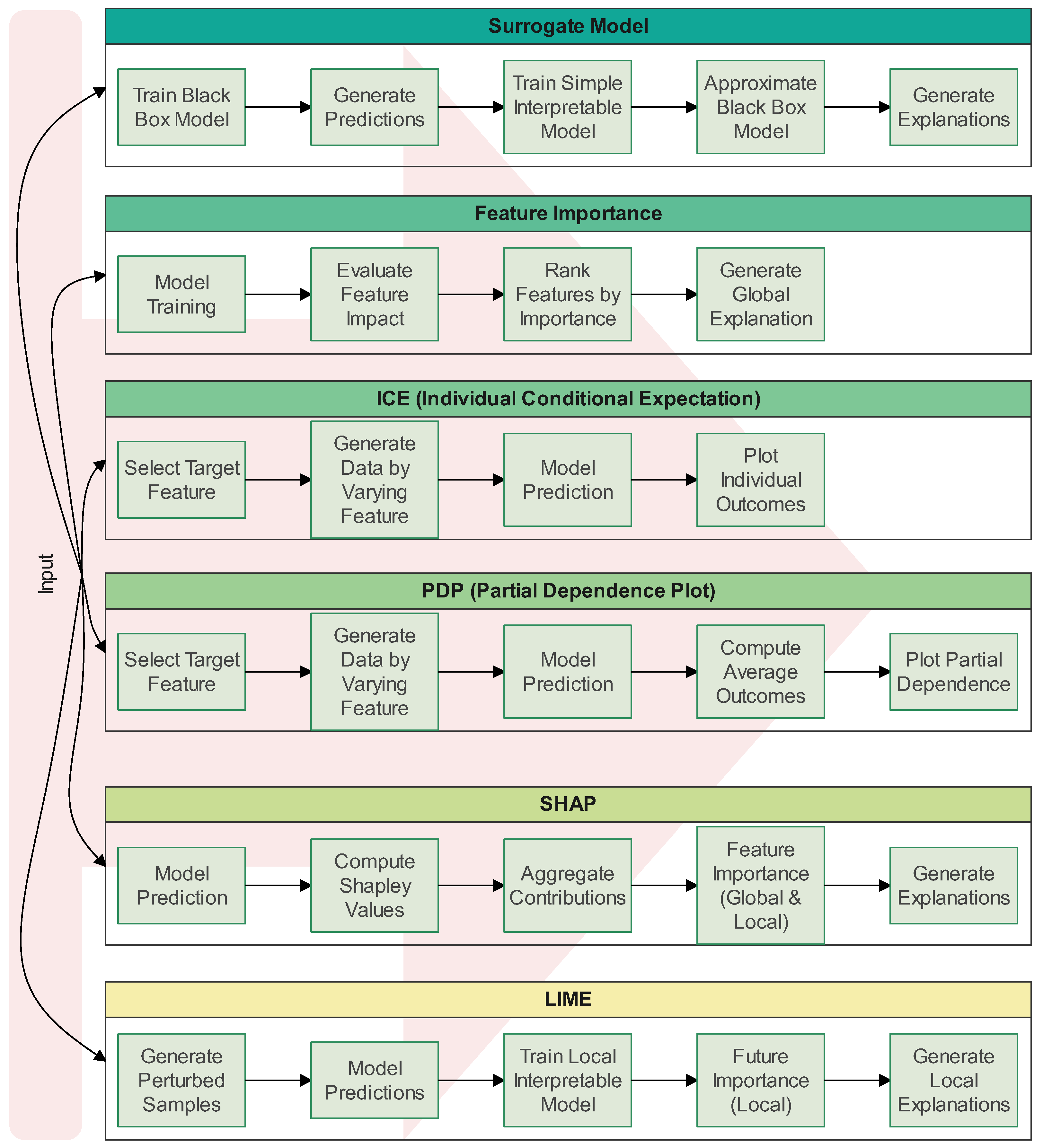

4.2. Model-Agnostic Methods

- LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations): LIME explains individual predictions by building a simpler, interpretable model around a specific prediction. This method works with any machine learning model and helps users understand the factors that contributed to a particular decision. However, LIME only provides local explanations, which may not generalize to the model’s overall behavior [59].

- SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations): SHAP uses game theory to distribute the contribution of each feature fairly in a prediction. It offers consistent and clear explanations but can be computationally intensive, especially for large datasets or complex models [60].

- Partial Dependence Plots (PDP): PDPs illustrate the relationship between a feature and the predicted outcome, helping users understand whether a feature has a linear or nonlinear effect on the outcome. However, PDPs may provide misleading interpretations if features are highly correlated [29].

- Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) Plots: ICE plots are similar to PDPs but focus on individual predictions, showing how changes in a feature affect each data point’s prediction. ICE plots offer more detailed insights but can become difficult to interpret with large datasets [61].

- Feature Importance: This method assigns a score to each feature based on its contribution to the model’s prediction accuracy. Feature importance helps identify which features are most influential, but the results can vary if the features are interdependent [28].

- Surrogate Models: Surrogate models create simplified approximations of complex systems, making predictions more interpretable. However, while surrogate models reduce computational costs, they may not capture the full complexity of the original model [62].

4.3. Post-Hoc Explainability

- Counterfactual Explanations: Counterfactual explanations describe how changes to certain inputs would have led to different outcomes. For example, in credit applications, a counterfactual explanation could indicate that a loan would have been approved if the applicant had a higher income. Generating realistic counterfactuals can be challenging, but they provide actionable insights for users [63].

- Saliency Maps: Saliency maps are typically used in image-based models to highlight which parts of an image were most important for the model’s decision. Although they provide a visual explanation, saliency maps can be inconsistent across different models and datasets [64].

- Attention Mechanisms: Attention mechanisms, often used in neural networks, focus on the most relevant parts of the input, improving both model performance and interpretability. However, using attention mechanisms may increase the computational complexity of the model [65].

- Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP): LRP explains predictions by tracing them back through the layers of a neural network, identifying which input features contributed most to the output. While LRP offers detailed insights, it can be time-consuming and difficult to apply to very deep networks [66].

- Gradient-Based Methods (e.g., Grad-CAM): These methods use gradients to identify which parts of an image influenced the model’s prediction. Gradient-based methods are commonly used in deep learning applications but may overlook finer details in the data [67].

- Explainable Boosting Machines (EBM): EBMs are an interpretable machine learning technique that combines boosting with transparency, making them both accurate and understandable. However, as the number of features increases, EBMs can become more complex [68].

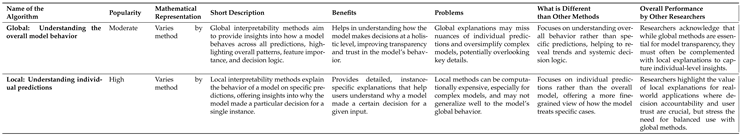

4.4. Perspectives in Explainability

- Global vs. Local Explanations: Global explanations aim to provide insights into how a model behaves across all data points, while local explanations focus on explaining individual predictions. Both approaches offer valuable perspectives, depending on whether the goal is to understand the overall behavior of the model or specific decisions. Table 8 provides a comparison of global and local interpretability approaches in machine learning models.

|

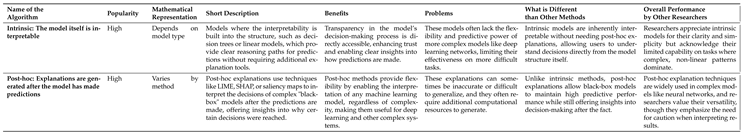

- Intrinsic vs. Post-Hoc: Intrinsic interpretability refers to models that are naturally transparent, such as decision trees and linear models. Post-hoc interpretability involves explaining black-box models after predictions have been made, using techniques like LIME or SHAP. Table 9 presents a comparison of intrinsic and post-hoc interpretability methods.

|

- Human Interpretability: Human interpretability measures how easily a human can understand the explanations provided by a model. This is critical for ensuring trust and usability in AI systems. Table 10 presents an evaluation of model interpretability based on human understanding of the explanations.

|

5. Explainable AI in Robotics

5.1. Explainable Robotics for Human-Robot Interaction

- Saliency Maps: Saliency maps visually highlight the regions of an image that most significantly influence the robot’s decision-making process. This technique provides a visual explanation for deep learning models and is useful for tasks such as image recognition. However, saliency maps can sometimes produce noisy results and may be difficult to interpret reliably [64].

- Attention Mechanisms: Attention mechanisms allow the robot to focus on the most relevant parts of input data by assigning different levels of importance to different features. This approach enhances both performance and interpretability, especially in tasks such as machine translation and image captioning [65].

- Natural Language Explanations: Natural language explanations enable robots to articulate their decision-making processes in plain, everyday language, bridging the gap between complex AI decisions and human understanding. This makes AI systems more accessible and transparent to non-expert users [73].

5.2. Transparency in Autonomous Robots

- LIME: Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) generates locally interpretable models around specific predictions, allowing users to understand why a particular decision was made by a robot. While LIME is useful for building trust, it may not capture the full complexity of the global model [59].

- SHAP: SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) use game theory to attribute the contribution of each feature to a robot’s decision. SHAP provides consistent and clear explanations but can be computationally expensive for complex models [60].

- Rule-Based Explanations: Rule-based explanations offer straightforward decision paths using IF-THEN rules. While these are easy to understand, they may be too rigid to capture the nuances present in more complex AI models [75].

| Name of Algorithm | Popularity | Description | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIME | High | LIME explains machine learning predictions by creating a simple model around specific predictions. |

Helps users understand why a model made a particular prediction, which builds trust in complex models. |

May miss some of the complex factors in the original model. |

| SHAP | High | SHAP assigns importance scores to each feature of a prediction using game theory. |

Provides consistent explanations for how features impact predictions, using a sound mathematical framework. |

Can be slow and resource-heavy for complex models. |

| Rule-based Explanations | Low | Uses IF-THEN rules to explain decisions step-by-step. |

Easy to understand, showing clearly how decisions are made. |

Too rigid for complex AI, may miss important nuances. |

5.3. Interpretable Learning for Robotic Control

- Policy Summaries: Policy summaries focus on learning the underlying reward function from a robot’s behavior. This is particularly useful in cases where specifying explicit rewards is challenging, though it can be difficult to infer the true objective from limited demonstrations [77].

- Visualizing Learned Behaviors: Visualizing learned behaviors helps to understand the robot’s actions during reinforcement learning. Although this technique aids in interpreting learning outcomes, it can be challenging to implement in complex environments [78].

- Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL): HRL breaks complex tasks into smaller subtasks, enabling robots to learn efficiently. However, poorly structured subtasks can hinder learning efficiency and overall performance [79].

| Name of Algorithm | Popularity | Description | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Summaries (Inverse Reinforcement Learning) | High | Focuses on learning the reward function from an agent’s behavior instead of knowing it beforehand, like in standard reinforcement learning. |

Allows us to learn from demonstrations without needing an explicit reward function, useful for tasks where it is difficult to define the reward in advance. |

It can be hard to figure out the true reward from limited demonstrations, as different rewards can lead to the same behavior. |

| Visualizing Learned Behaviors (Deep Q-networks) | High | A deep learning-based reinforcement learning algorithm that learns optimal actions by interacting with the environment. |

Can learn directly from high-dimensional input, such as images from video games, without needing pre-defined features. |

Difficult to train, especially in complex environments or when rewards are sparse, leading to unstable results. |

| Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL) | Moderate | Divides complex tasks into smaller, manageable subtasks, improving learning efficiency. |

By breaking down the task, HRL agents can learn faster and achieve better results compared to standard RL approaches. |

Poorly designed subtasks can lead to suboptimal learning, limiting the agent’s overall performance. |

5.4. Explainable AI in Collaborative Robotics

- Predictive Explanations: These models provide transparent decision-making processes, which can help users understand predictions, although simpler models may sometimes sacrifice accuracy [80].

- User Feedback Integration: User feedback integration enables robots to refine their behaviors through active user input, ensuring models are aligned with real-world needs. Designing intuitive and efficient feedback systems is crucial for success [81].

- Context-Aware Explanations: Context-aware explanations tailor responses based on the user’s current task or situation, improving relevance and trust. However, accurately identifying the relevant context can be challenging [59].

| Name of Algorithm | Popularity | Description | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Explanations (Interpretable Machine Learning) | Moderate | Builds models that are easy for humans to understand. The structure and decision-making process are clear and transparent. |

Allows people to see why a model made a certain prediction, building trust, especially in fields like healthcare or finance. |

Simple models may not be as accurate as complex models, especially for tasks that require finding complex patterns. |

| User Feedback Integration | High | Focuses on getting human feedback to improve machine learning models. Humans actively participate in refining models to make them more useful. |

Leads to models that are more user- friendly and aligned with real-world needs by incorporating human expertise. |

Designing easy ways for humans to give feedback without overwhelming them is crucial for success. |

| Context-Aware Explanations | Low | Provides explanations that are tailored to the user’s specific situation or task, considering their background and needs. |

Users find the explanations more relevant and easier to understand, which builds trust in the AI system. |

It can be challenging to identify the right context and adjust explanations effectively. |

5.5. Explainable AI for Safety in Robotics

- Anomaly Detection: Anomaly detection identifies unusual patterns in robot behavior, aiding in the detection of system failures or operational anomalies. However, balancing the detection of true anomalies while minimizing false alarms can be difficult [83].

- Counterfactual Explanations: These explanations illustrate how changing specific conditions could have altered the robot’s actions. While helpful for understanding potential future adjustments, generating realistic counterfactuals can be complex [63].

- Risk Assessment Models: Risk assessment models identify potential harms associated with AI systems. Although useful for promoting safety, they do not inherently guarantee bias-free operation [84].

| Name of Algorithm | Popularity | Description | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anomaly Detection | High | Detects unusual patterns in data that differ from normal behavior, often used for identifying system failures, fraud, or other critical events. |

Can detect unknown threats or issues without prior knowledge, making it useful for identifying new forms of attacks or unexpected situations. |

Balancing accurate detection of anomalies with minimizing false alarms is challenging. |

| Counterfactual Explanations | High | Explains decisions by showing how outcomes could change if specific conditions were different, like how a higher income could lead to loan approval. |

Helps users understand how to change future outcomes, without needing detailed technical knowledge of the decision process. |

Ensuring these explanations are realistic and achievable in the real world can be difficult. |

| Risk Assessment Models | High | Identify potential harms in AI systems, helping to manage risks from design to deployment. |

Ensures AI is accurate, trustworthy, and transparent by assessing risks related to explainability, which helps build user trust. |

Overreliance on explanations may lead to a false sense of safety or fairness, even though explanations alone don’t guarantee bias-free AI systems. |

5.6. Explainable AI for Adaptive Robotics

- Interactive Learning: Interactive learning allows robots to acquire new information through interactions with their environment, enhancing learning efficiency. However, designing effective strategies for interaction remains a challenge [85].

- User-Guided Adjustments: User-guided adjustments permit users to modify the robot’s behavior based on their expertise, improving model accuracy. However, user biases may affect fairness and generalization [81].

- Adaptive Models with Feedback Loops: These models adjust dynamically based on real-time data, improving performance in dynamic environments. However, they are sensitive to noisy feedback, which can degrade overall performance [86].

| Name of Algorithm | Popularity | Description | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactive Learning (Lifelong Learning) | Moderate | Algorithms that actively learn by interacting with their environment or users, unlike traditional methods where data is passively received. |

Increases learning efficiency by allowing the algorithm to ask for needed data, making it more adaptable. |

Designing effective interaction strategies is complex. |

| User-Guided Adjustments | Moderate to High | Users can adjust or refine a model’s behavior through an interface, adding expertise to improve results. |

Lets users improve the model, making it more accurate and trustworthy, especially when data is biased. |

User bias can affect fairness if adjustments are poorly designed. |

| Adaptive Models with Feedback Loops | Moderate | Models adjust settings based on real-time feedback, used in dynamic environments like finance or autonomous vehicles. |

Constant learning from real-time data improves accuracy and performance in changing environments. |

Sensitive to noisy feedback, which may reduce performance. |

5.7. Ethical and Trustworthy Robotics through Explainable AI

- Ethical Rule Enforcement: This approach ensures that robots adhere to ethical guidelines, reducing bias and promoting fairness. However, defining universal ethical rules can be subjective and context-dependent [88].

- Explainable Decision-Making Frameworks: These frameworks provide transparency in decision-making, building user trust. Balancing the simplicity of explanations with model accuracy can be challenging [89].

- Compliance Auditing: Compliance auditing ensures that robots comply with regulatory and ethical standards, minimizing risk and enhancing operational credibility. Keeping up with changing regulations presents a challenge [90].

| Name of Algorithm | Popularity | Description | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Rule Enforcement | Moderate | Implements rules to make sure AI systems follow ethical standards. |

Reduces harm, bias, and promotes fairness and accountability. |

Hard to define universal ethics, as rules can be subjective. |

| Explainable Decision-Making | High | Makes AI decisions clear and understandable to users. |

Builds trust by explaining how decisions are made. |

Difficult to balance simplicity with accuracy in complex models. |

| Compliance Auditing | High | Checks if organizations follow laws and internal policies. |

Reduces risks, improves efficiency, and enhances credibility. |

Keeping up with changing laws is a challenge. |

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Artificial Intelligence Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Solution, By Technology, By End Use, By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2022 - 2030. Grand View Research 2022.

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer, 2001.

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer, 2006.

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of Decision Trees. Machine Learning 1986, 1, 81–106.

- Lloyd, S.P. Least Squares Quantization in PCM. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1982, 28, 129–137.

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis; Springer, 2002.

- Watkins, C.J.; Dayan, P. Q-Learning. Machine Learning 1992, 8, 279–292.

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; et al. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [CrossRef]

- Elman, J.L. Finding structure in time. Cognitive Science 1990, 14, 179–211.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2012, pp. 1097–1105.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition 2016. pp. 770–778.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; et al. Attention Is All You Need 2017. pp. 5998–6008.

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. "Why Should I Trust You?" Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier 2016. pp. 1135–1144.

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions 2017. pp. 4765–4774.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision 2021.

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; et al. Flamingo: A Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.14198 2022.

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning 1995, 20, 273–297.

- Cover, T.; Hart, P. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1967, 13, 21–27.

- Rish, I. An empirical study of the naive Bayes classifier. In Proceedings of the IJCAI 2001 Workshop on Empirical Methods in AI, 2001, Vol. 3, pp. 41–46.

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67.

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1996, 58, 267–288.

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2005, 67, 301–320.

- Fisher, R.A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Annals of Eugenics 1936, 7, 179–188. [CrossRef]

- Duda, R.O.; Hart, P.E.; Stork, D.G. Pattern Classification; Wiley-Interscience, 2001.

- Pearl, J. Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems: Networks of Plausible Inference; Morgan Kaufmann, 1988.

- Suykens, J.A.; Vandewalle, J. Least squares support vector machine classifiers. Neural Processing Letters 1999, 9, 293–300. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32.

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics 2001, pp. 1189–1232. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. ACM, 2016, pp. 785–794.

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, pp. 3149–3157.

- Dorogush, A.; Ershov, V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Gradient boosting with categorical features support. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018, pp. 6638–6648.

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 1997, 55, 119–139.

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Machine Learning 1996, 24, 123–140.

- Wolpert, D.H. Stacked generalization. In Proceedings of the Neural Networks. Elsevier, 1992, Vol. 5, pp. 241–259.

- Kuncheva, L.I. Combining Pattern Classifiers: Methods and Algorithms; Wiley-Interscience, 2004.

- Johnson, S.C. Hierarchical clustering schemes. Psychometrika 1967, 32, 241–254. [CrossRef]

- Hyvärinen, A.; Oja, E. Independent component analysis: Algorithms and applications. Neural Networks 2000, 13, 411–430. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D.A. Gaussian Mixture Models. In Proceedings of the Encyclopedia of Biometrics. Springer, 2009, pp. 659–663.

- Kohonen, T. The self-organizing map. Proceedings of the IEEE 1990, 78, 1464–1480.

- Sutton, R.S.; McAllester, D.A.; Singh, S.P.; Mansour, Y. Policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning with function approximation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2000, pp. 1057–1063.

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 2014.

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2015, pp. 1–9.

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2017, pp. 4700–4708.

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780.

- Cho, K.; Van Merrienboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2014, pp. 1724–1734.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. OpenAI Blog 2018, 1, 1–12.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2020, pp. 3376–3387.

- Yang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Le, Q.V. XLNet: Generalized autoregressive pretraining for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019, pp. 5753–5763.

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023, 24, 1–113.

- Ramesh, A.; Pavlov, M.; Goh, G.; Gray, S.; Voss, C.; Radford, A.; Chen, M.; Sutskever, I. Zero-shot text-to-image generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.12092 2021.

- Li, L.H.; Luo, H.; Shuster, K.; Piramuthu, R.; Ueffing, N.; Berg, A.C.; Baldridge, J. VisualBERT: A simple and performant baseline for vision and language. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 4189–4202.

- Singh, A.; Hu, R.; Adcock, A.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Lee, S.; Berg, T.L.; Baldridge, J. FLAVA: A foundational language and vision alignment model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2022, pp. 16734–16751.

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2014.

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2014, pp. 2672–2680.

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. "Why should I trust you?": Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. ACM, 2016, pp. 1135–1144.

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30.

- Goldstein, A.; Kapelner, A.; Bleich, J.; Pitkin, E. Peeking inside the black box: Visualizing statistical learning with plots of individual conditional expectation. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 2015, 24, 44–65. [CrossRef]

- Craven, M.W.; Shavlik, J.W. Extracting tree-structured representations of trained networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 1996, pp. 24–30.

- Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Russell, C. Counterfactual explanations without opening the black box: Automated decisions and the GDPR. Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 2018, 31, 841–887.

- Simonyan, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6034 2013.

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2015.

- Bach, S.; Binder, A.; Montavon, G.; Klauschen, F.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. Pixel-wise explanations for non-linear classifier decisions by layer-wise relevance propagation. PloS one 2015, 10, e0130140. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2017, pp. 618–626.

- Caruana, R.; Lou, Y.; Gehrke, J.; Koch, P.; Sturm, M.; Elhadad, N. Intelligible models for healthcare: Predicting pneumonia risk and hospital 30-day readmission. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2015, pp. 1721–1730.

- Sanneman, L.; Shah, J.A. Trust considerations for explainable robots: A human factors perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.05940 2020.

- Liao, Q.V.; Sundar, S.S. Designing for responsible trust in AI systems: A communication perspective. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2022, pp. 1257–1268.

- De Graaf, M.M.; Dragan, A.; Malle, B.F.; Ziemke, T. Introduction to the special issue on explainable robotic systems, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Bhatia, K.; Abbeel, P.; Dragan, A.D. Establishing appropriate trust via critical states. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 3929–3936.

- Ehsan, U.; Harrison, B.; Chan, L.; Riedl, M.O. Rationalization: A neural machine translation approach to generating natural language explanations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018, pp. 81–92.

- Papagni, G.; Koeszegi, S. Understandable and trustworthy explainable robots: A sensemaking perspective. Paladyn, Journal of Behavioral Robotics 2020, 12, 13–30. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.; Diederich, J.; Tickle, A.B. A survey and critique of techniques for extracting rules from trained artificial neural networks. Knowledge-Based Systems 1995, 8, 373–389. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F.; Dazeley, R.; Vamplew, P.; Moreira, I. Explainable robotic systems: Understanding goal-driven actions in a reinforcement learning scenario. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 18113–18130. [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.Y.; Russell, S.J. Algorithms for inverse reinforcement learning. Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) 2000, pp. 663–670.

- Zahavy, T.; Ben-Zrihem, N.; Mannor, S. Graying the black box: Understanding DQNs. Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) 2016, pp. 1899–1908.

- Dietterich, T.G. Hierarchical reinforcement learning with the MAXQ value function decomposition. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2000, 13, 227–303. [CrossRef]

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608 2017.

- Amershi, S.; Cakmak, M.; Knox, W.B.; Kulesza, T. Power to the people: The role of humans in interactive machine learning. AI Magazine 2014, 35, 105–120. [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Zhao, S.; Kuck, J.; Ivanovic, B.; Savarese, S.; Schmerling, E.; Pavone, M. Sample-efficient safety assurances using conformal prediction. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2024, 43, 1409–1424. [CrossRef]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2009, 41, 1–58.

- Miller, T. Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artificial Intelligence 2019, 267, 1–38.

- Thrun, S.; Pratt, L. Lifelong Learning Algorithms; Springer, 1995.

- Dean, T.; Boros, E. Inferring personalization factors from user interactions in hybrid data retrieval systems. ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS) 2017, 35, 1–40.

- Alufaisan, Y.; Marusich, L.R.; Bakdash, J.Z.; Zhou, Y.; Kantarcioglu, M. Does explainable artificial intelligence improve human decision-making? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 6618–6626.

- Arvan, M.; O’Reilly, U.M. Towards accountable and ethical AI: A systematic survey. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society 2018, 3, 1–15.

- Gunning, D.; Aha, D. DARPA’s explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) program. AI Magazine 2019, 40, 44–58.

- Lepri, B.; Oliver, N.; Letouzé, E.; Pentland, A.; Vinck, P. Fair, transparent, and accountable algorithmic decision-making processes: The premise, the proposed solutions, and the open challenges. Philosophy & Technology 2017, 31, 611–627.

| Name of the Algorithm | Popularity | Mathematical Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different from Other Methods | Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Trees: Intrinsically interpretable | High | N/A | Decision Trees are popular machine learning models due to their ease of interpretability. The tree-like structure provides a clear decision path from root to leaf, making the decision-making process easily understandable. | The main advantage is the transparency of their decisions, which aids in building trust, explaining the model, and identifying biases. | Decision trees can overfit to training data, leading to poor generalization on new data. They are also sensitive to small changes in data, which can result in different tree structures, causing instability. | Unlike black-box models like neural networks, decision trees are fully interpretable, allowing users to trace the decision path directly from root to leaf, showing how each feature impacts the prediction. | Decision trees perform well in simple cases but may not achieve the same level of accuracy as more complex models (e.g., random forests, deep learning) in tasks with higher complexity. |

| Linear Models: Coefficients provide direct interpretability | Moderate | N/A | Linear models offer a simple way to model relationships between variables by quantifying the impact of each predictor on the response variable through coefficients. This makes them highly interpretable and suitable for applications requiring clear insights into data patterns. | The ability to clearly quantify and explain the influence of each predictor variable on the outcome simplifies understanding and interpretation of relationships in the data. | Linear models assume linear relationships between variables, which may not always capture the true complexity of non-linear relationships in real-world data, limiting their applicability to more complex tasks. | Linear models differ from others in their explicit representation of predictor variables through easily interpretable coefficients, making them highly transparent and easy to understand. | Researchers appreciate their simplicity, transparency, and ease of interpretation, though their performance may vary depending on the complexity of the data. They are often used in cases where interpretability is crucial. |

| Name of the Algorithm | Popularity | Mathematical Representation | Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different from Other Methods | Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | High | N/A | LIME is used to explain predictions from black-box machine learning models. It approximates complex models locally around a specific prediction using simpler models, enabling users to understand key factors driving predictions. | It is model-agnostic, meaning it works with any machine learning model. It is versatile and can explain opaque models, providing insights otherwise inaccessible. | LIME offers local explanations, which means it explains individual predictions without offering a global view of the model’s behavior. This can lead to misleading conclusions about overall model behavior. | LIME approximates black-box models by creating simple, interpretable models (e.g., linear models) locally around specific predictions, rather than interpreting the entire model globally. | LIME is widely regarded as a valuable tool for explaining individual predictions, but researchers caution that its local nature may not represent the model’s global behavior accurately. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | High | N/A | SHAP uses game theory to fairly distribute the contribution of each feature to a prediction, offering insights into feature importance and model behavior. | SHAP provides a theoretically sound, unified approach to explaining predictions, improving upon prior methods that lacked consistency. | Calculating exact SHAP values can be computationally expensive, especially for large datasets and complex models, although approximations can help. | SHAP unifies various feature importance methods by providing a solid theoretical foundation, which clarifies and connects other techniques in the field of model interpretability. | SHAP is highly regarded for its theoretical grounding and practical application, although the computational cost remains a challenge, especially for complex models. |

| Partial Dependence Plots (PDP) | High | N/A | PDPs visualize the marginal effect of one or two features on a predicted outcome, showing if the relationship between a feature and the target is linear, complex, or non-existent. | PDPs effectively illustrate the marginal effect of features, providing clear visual insights into model behavior. | PDPs can be misleading when predictor variables are correlated, which may distort the interpretation of individual feature effects. | PDPs visualize the average effect of features on outcomes, marginalizing the effects of other features, offering insights into model behavior in a simplified form. | Researchers find PDPs useful but emphasize caution, especially with complex datasets that have feature dependencies. They should not be used in isolation. |

| Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) Plots | Moderate | N/A | ICE plots visualize the relationship between a feature and the model’s prediction for individual observations, offering instance-level insights. | ICE plots illustrate how predictions for individual observations change as a feature varies, while keeping other features constant, offering granular insights. | ICE plots can become visually cluttered with large datasets, obscuring overall trends, making them difficult to interpret when many observations are involved. | ICE plots show feature dependency on an individual basis, differing from PDPs which show average effects across the dataset. | ICE plots are recognized for offering detailed individual-level insights, but researchers caution against visual clutter and difficulty in interpreting plots with many observations. |

| Feature Importance | High | N/A | Assigns scores to features based on their contribution to the model’s prediction accuracy, offering insights into which features are most influential. | Feature importance helps in understanding which features drive predictions, guiding feature selection and improving model interpretability. | Different feature importance methods can yield inconsistent rankings, making it challenging to determine the true importance of features. | Feature importance accounts for feature interactions and non-linear relationships, offering a comprehensive view of feature influence. | While feature importance is valuable for model understanding, researchers note that results can be misleading due to feature correlations and model instability. |

| Surrogate Models | Moderate | N/A | Surrogate models are simplified approximations of complex systems or simulations, reducing computational costs for prediction and analysis. | Surrogate models significantly reduce computational time and costs, making tasks like optimization and uncertainty quantification more feasible. | Surrogates are only approximations and may not fully capture the complexities of the original system, potentially leading to inaccuracies. | Surrogate models replace complex simulations with faster, data-driven approximations, making them useful for handling expensive evaluations. | Surrogate models show good agreement with detailed simulations but depend heavily on model type, training data quality, and application, influencing their effectiveness. |

| Name of the Algorithm |

Popularity | Mathematical Representation |

Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different from Other Methods |

Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counterfactual Explanations | High | N/A | Counterfactual explanations provide what-if scenarios to show how changing specific input features would alter a model’s prediction. | Helps users understand which input variables are most influential and how to achieve desired outcomes by adjusting certain features. | It can be difficult to generate realistic counterfactuals, especially for complex models, making practical application challenging. | Focuses on explaining how an outcome can be changed rather than why the current decision was made. | More research is needed to improve the feasibility and practicality of using counterfactual explanations across diverse applications. |

| Saliency Maps | High | N/A | Visual representations that highlight important pixels in an image, showing which parts of an image contribute most to a deep learning model’s prediction. | Provides insights into convolutional neural networks’ decision-making process by focusing on the most relevant image areas. | Sensitive to noise and can produce inconsistent explanations without standardized evaluation metrics. | Offers pixel-level visual explanations for image-based models, providing intuitive insights that distinguish it from other methods. | Researchers recognize their value but emphasize caution in interpretation and the need for more robust evaluation metrics. |

| Attention Mechanisms in Neural Networks | High | N/A | Inspired by human visual attention, attention mechanisms allow networks to focus selectively on important parts of the input data, improving performance. | Enhances neural network performance by concentrating on the most relevant input features for better efficiency and prediction accuracy. | Increased computational cost due to the additional complexity introduced by attention mechanisms, especially in large datasets. | Enables neural networks to process input more efficiently by focusing on relevant data rather than treating all inputs equally. | Researchers widely agree that attention mechanisms improve performance significantly, especially in tasks involving sequential data. |

| Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) | Moderate | N/A | Decomposes neural network outputs back to input features to interpret decisions, showing which input parts contribute most to a prediction. | Enhances interpretability by revealing which parts of the input are most relevant for a model’s decision, applicable across various types of neural networks. | High computational complexity for large models, and explanations may not always align with human intuition. | Provides layer-specific, detailed explanations by backpropagating relevance scores, offering more granular insights than other methods. | Researchers appreciate its ability to provide intuitive explanations but highlight the need for improvements in computational efficiency and interpretability. |

| Gradient-Based Methods (e.g., Grad-CAM) | High | N/A | Use gradients flowing into convolutional neural networks to visualize which image regions are important for a particular prediction. | Provides visual explanations that make convolutional neural networks more transparent and interpretable, particularly for image-based tasks. | Can lack fine-grained detail, highlighting broad regions but missing subtle image features that may also influence decisions. | Broadly applicable across different CNN architectures without requiring retraining, making it versatile for understanding various models. | Researchers view Gradient-Based Methods like Grad-CAM as valuable for explaining CNNs, although improvements in detail are still needed. |

| Explainable Boosting Machines (EBM) | High | N/A | Combines boosting techniques with generalized additive models, balancing accuracy and interpretability by providing high-quality predictions while remaining understandable. | High accuracy with clear interpretability, allowing users to understand how predictions are made without sacrificing prediction performance. | Model complexity increases significantly with high-dimensional data, potentially challenging the interpretability of EBMs. | Balances accuracy and interpretability, unlike many models that prioritize one over the other (e.g., neural networks for accuracy or decision trees for simplicity). | Researchers report state-of-the-art accuracy comparable to less interpretable models like Gradient Boosting Machines while maintaining ease of understanding. |

| Name of the Algorithm |

Popularity | Mathematical Representation |

Short Description | Benefits | Problems | What is Different than Other Methods |

Overall Performance by Other Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saliency maps | High | Saliency maps calculate the magnitude of the gradient of a model’s output with respect to each input pixel, highlighting areas with higher influence on the output. | They highlight the important regions in an image for a deep learning model’s prediction, enhancing interpretability in image-based tasks. | Can be noisy and difficult to interpret. Sometimes highlight irrelevant features and may not fully reflect the model’s decision-making process. | Rely on back-propagation gradients and are specific to the model, often used for CNN-based image models. | Despite improvements in speed and accuracy, saliency maps are still outperformed by models designed specifically for salient object detection. | |

| Attention mechanisms | High | N/A | Attention mechanisms enable models to focus on specific parts of the input by assigning different weights to parts of the data, highlighting the most relevant information. | Improve both the effectiveness and interpretability of models, especially in tasks like machine translation and image captioning. | High computational cost, sensitivity to input ordering, and difficulty in training. Can still be considered a "black box." | Dynamically prioritize information, leading to improved performance in various deep learning tasks, especially with sequential data. | Researchers consistently report positive results, with attention mechanisms significantly improving the performance of models across many applications. |

| Natural language explanations | Moderate | N/A | Provide human-understandable explanations by expressing the AI’s decision-making process in natural language, similar to explaining reasoning to a human colleague. | Help bridge the gap between AI decision-making and human understanding, making AI systems more accessible and transparent. | Challenges include generating accurate, contextually relevant explanations that balance clarity and technical depth. | Unlike other methods that rely on visualizations or rule-based explanations, this approach uses everyday language to communicate reasoning. | This is an evolving area, with more research needed to improve the quality of explanations and assess its practical adoption across various fields. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).