1. Introduction

1.1. MRI, Cartesian and Non-Cartesian

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a crucial diagnostic tool in modern medicine, capable of providing detailed images of anatomical structures [

1]. MRI data is collected in k-space, where signals are recorded based on their spatial frequency and phase information [

2]. This k-space data is then transformed into the spatial domain through the Fourier transform [

3]. The resulting images provide high-resolution, contrast-rich views of anatomical structures, aiding in accurate diagnosis and treatment planning. The Cartesian trajectory of k-space corresponds to a sampling scheme in which data is collected along regular grid lines. While such fully sampled images are ideal, some degree of undersampling is required to reduce scan times and minimize patient discomfort [

4]. Non-Cartesian trajectories, such as radial or spiral paths, yield improved image quality compared to Cartesian undersampling, allowing faster MRI acquisition via efficient k-space coverage [

5].

1.2. Cartesian k-Space MRI Reconstruction Methods

Traditional Cartesian reconstruction methods involve the direct application of the inverse Fast Fourier Transform (IFFT) to uniformly sampled k-space data [

6]. Despite its widespread use, standard FFT-based reconstruction is prone to artifacts from motion and undersampling. Compressed sensing has emerged as a key alternative, exploiting the sparsity of undersampled data to reconstruct images by solving an optimization problem that enforces sparsity constraints, leading to high-quality reconstructions with reduced scan times [

7]. Compressed sensing is often used in conjunction with parallel imaging, the combination being abbreviated as PICS. Parallel imaging techniques, such as Sensitivity Encoding (SENSE) and Generalized Autocalibrating Partially Parallel Acquisitions (GRAPPA), leverage the spatial sensitivity profiles of multiple receiver coils to accelerate MRI acquisitions [

8].

Deep learning methods have had success in reconstructing undersampled Cartesian MRI [

9,

10,

11,

12], improving upon classical techniques at high accelerations by allowing greater complexity in the employed model [

13] and extracting complex mappings from training data [

14]. Architectures such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Generative Adversarial Networks have been employed to restore missing or corrupted k-space data, leveraging large datasets to enhance reconstruction speed and accuracy [

15,

16].

1.3. Non-Cartesian k-Space MRI Reconstruction Methods

Reconstructing high-quality images from non-Cartesian data is challenging, as traditional Fourier-based methods struggle to handle the irregularity and gaps in the sampling pattern [

17]. Standard non-Cartesian reconstruction methods typically involve arranging the data onto a Cartesian grid before applying the FFT, a process known as gridding [

18]. The sparsity of non-Cartesian data also makes it a suitable candidate for compressed sensing, Non-Cartesian GRAPPA, and SENSE [

5]. Methods such as Compressed Sensing overcome the limitations of Fourier techniques by balancing fidelity to acquired data with the assumption of sparsity in the image domain [

8].

Deep neural networks gained traction in this problem [

19] due to their ability to handle non-Cartesian data without the need for regridding. Hammernik et al. [

15] employed VarNet for the reconstruction of complex multi-channel MR data, leveraging its ability to seamlessly combine variational inference techniques with deep learning to achieve impressive performance in reconstruction tasks [

20]. Aggarwal et al. introduced MoDL [

21], an integration of model-based and deep learning approaches. MoDL’s application of iterative unrolling of optimization algorithms within a deep learning framework yields a powerful architecture that captures both data-driven and model-driven insights, enabling accurate and efficient reconstructions. Vision Transformers have also demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in non-Cartesian MRI reconstruction [

22]. Unlike traditional CNNs, which rely on convolutional kernels to process spatial information, ViTs decompose the input data into a sequence of patches and apply transformer models to learn complex representations [

23], which is effective in handling the structure of non-Cartesian k-space data.

Table 1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of the reconstruction techniques discussed. It should be noted that Non-Cartesian reconstruction with deep neural networks can require specialized algorithms and additional preprocessing [

24]. These limitations, combined with the need for domain-specific expertise to implement and optimize non-Cartesian deep learning techniques, present challenges to their practical application. Despite these difficulties, deep learning methods have achieved success in the reconstruction of undersampled MRI [

19,

25]. This is particularly relevant for accelerated acquisition scenarios, which are essential for further reducing scan times while maintaining high image quality.

1.4. The Rosette Trajectory

The Rosette trajectory, a non-Cartesian trajectory which traces a petal-like path through k-space, provides particularly effective k-space coverage [

26]. The efficient sampling pattern of the Rosette trajectory can yield a higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) compared to spiral or radial trajectories for MRI acquisition under high acceleration factors [

27]. Standard reconstruction techniques for rosette k-space involve adapting traditional gridding methods to handle the unique structure of the trajectory, including the development of dedicated density compensation functions (DCF) to account for the varying sampling density [

28].

Rosette has been shown to work well alongside CS and high acceleration factors [

26,

29]. Mahmud et al. achieve good performance with an acceleration factor of 6 in 7 Tesla CS Rosette spinal cord imaging [

30]. Li et al. use Rosette and CS to achieve 10 percent better results than radial and spiral trajectories at and acceleration factor of 10 [

27]. Alcicek et al. use a novel Rosette trajectory with CS to accomplish patient-friendly and high resolution magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging [

31]. While the Rosette trajectory is a promising candidate for high-acceleration reconstruction, training on raw MRI data is computationally expensive. In order to achieve flexible high accuracy reconstruction for accelerated Rosette imaging with good runtime performance, we utilize the direct Fourier transform to approximate the final result and the ViT network to transform this approximation into the expected image. The addition of a convolutional layer improves the reconstructed image by removing artifacts that arise from the pure ViT network. This hybrid approach promises to enhance the reconstruction of Rosette trajectory MRI, making it not only faster but also more adaptable to diverse imaging scenarios. As a benchmark, we apply VarNet [

15] and MoDL [

21].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method Overview

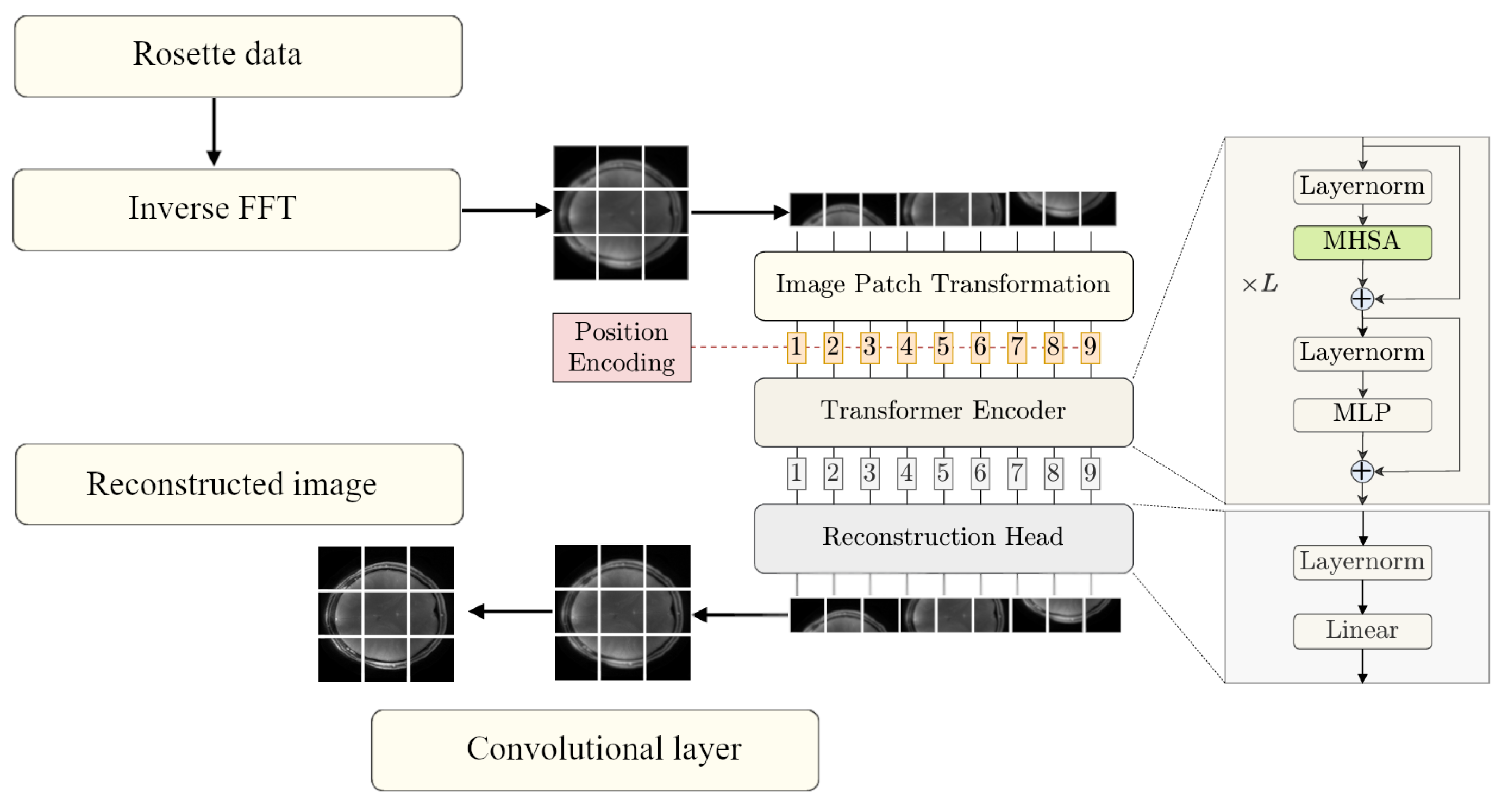

The method proposed in this work utilizes a strategy that combines traditional and modern deep learning techniques. The pipeline, shown in

Figure 1, operates in two key phases: an initial approximation phase and a refinement phase. During the initial approximation phase, the IFFT is applied to multi-coil Rosette-sampled k-space data, after which the resulting coil images are combined through root square sum to produce a rough image. This step, though computationally simple, introduces imprecision and noise due to the undersampled and non-uniform nature of the k-space trajectory. In the refinement phase, the rough image is passed to the ViT network, which has been trained with our data to predict the PICS reconstruction. The second stage effectively deals with artifacts, reduces noise, and produces a final image that closely approximates the reference. The ViT is particularly well-suited for this task due to its ability to model long-range dependencies and capture complex spatial patterns in the data that traditional methods may miss.

2.2. Vision Transformer

The network architecture of the employed ViT is based on the accelerated MRI reconstruction work by Lin and Heckel [

22] , repurposed for approximating the compressed sensing algorithm for MRI reconstruction. Their model is based on the ViT, originally proposed by Dosovitskiy et al. [

32] for image classification tasks. The ViT in turn applies the Transformer encoder, originally intended for sequential data, to visual data. This is accomplished by processing the input image as a sequence of patches. A trainable linear transformation maps each patch to a d-dimensional feature vector known as a patch embedding. To compensate for the lack of positional information, learnable position embeddings are used to encode the absolute position. Finally, a classification token is added to the beginning of the sequence. The encoder consists of N encoder layers, each containing a Multi-Head Self-Attention block and a multilayer perceptron block that transforms each feature vector independently. Layer normalization is applied before each block, and residual connections are added after each block for stable training. The output representation of the classification token is used for the final classification of the input image.

The ViT architecture by Lin and Heckel adapts this system for image reconstruction by removing the classification token and replacing the classification head with a reconstruction head tailored for mapping the transformer output back to a visual image [

22] . Unlike previous approaches that combine Transformers with convolutions [

33], this architecture uses only the standard Transformer encoder.

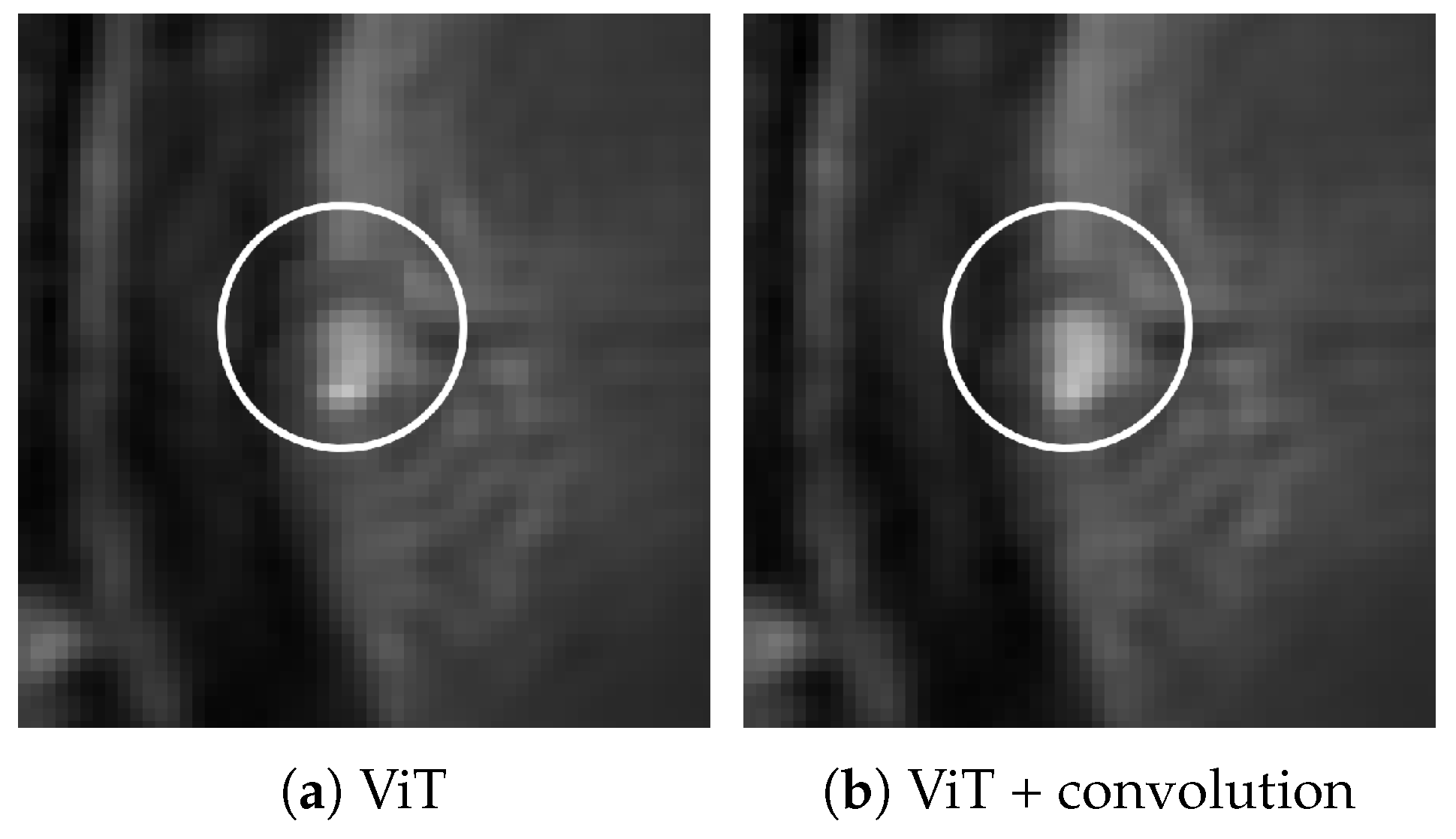

The ViT by itself produces significant artifacts in the form of miscolored patches with defined boundaries at regions of high contrast, irrespective of training augmentation. The inclusion of the convolutional layer corrects this issue.

Figure 2 shows the improvement granted by the addition of the layer.

2.3. Dataset and Pre-Processing

The experimental dataset comprises 6 sets (two for each patient) of 500 T1-weighted time series axial brain MRI scans acquired using the Rosette k-space trajectory, with a resolution of 512x512 pixels. The acquisition details are as follows:

Repetition Time (TR): 2.4 seconds

Echo Time (TE) (dual): 1 and 9 milliseconds:

Acceleration factor: 4

Number of petals: 189

Nominal in-plane resolution: 0.468 millimeters

Slice thickness: 2 millimeters

Flip angle: 7 degrees

Number of slices: 1

We employed both augmented and non-augmented datasets for Vision Transformer training and evaluation. Reference images for comparison were generated using a PICS algorithm implemented through the Berkeley Advanced Reconstruction Toolbox (BART) [

34]. The k-space data was converted to an initial approximation of the final image using the IFFT. These intermediate images are then used to train the network to minimize the difference between such inputs and the CS reference.

4 training sets were used for training and one set was used for validation, with 500 scans in each set. For singly augmented ViT, this results in 4000 inputs, and for triple augmentation this number becomes 8000.

The augmentations used for ViT training data include:

Random Horizontal Flip, probability=0.5

Random Vertical Flip, probability=0.5

Random Rotation, 0 to 180 degrees

Color Jitter, brightness/contrast/saturation, range= 0.8 to 1.2

Random Resized Crop, scale= 0.3 to 1.1

By simulating various imaging conditions during training, the network learns to extract meaningful features while remaining robust to variations in patient anatomies, imaging conditions, and acquisition scenarios.

2.4. Evaluation Methods

Reeconstruction performance was assessed using several image similarity metrics.

Table 2 shows the respective formulae. The metrics are applied to 6 randomly generated 50x50 pixel patches (biased towards the center to avoid empty space) and averaged to generate the final metric score.

The Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) measures image similarity between a reference image and a processed image. Higher scores are preferred.

Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE) is the root mean squared error between the images normalized by the sum of the observed values. Lower error is preferred.

Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) is a normalized Mutual Information (MI) score, where the scale between no mutual information and full correlation is given as 0 to 1.

Relative contrast is the ratio between the difference in maximum and minimum intensity and the sum of the same values.

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) measures the ratio between the maximum possible pixel value and the noise power. Higher PSNR values indicate better image quality.

2.5. Visualization

The reconstructed images were bias field corrected with the open source Advanced Normalization Tools toolbox (

https://github.com/ANTsX).

2.6. Training Procedure

The ViT training was completed using the PyTorch framework on an Nvidia A6000 GPU. For gradient descent, the Adam optimizer [

35] was used with a maximum learning rate of 0.0003. The "1cycle" learning rate scheduler [

36] was used alongside Adam to adjust the learning rate. A patch size of 10x10 pixels was used, defining the size of the square segments into which the input image is divided. The depth of the sequential layers of self-attention and feedforward networks was set as 10, while the number of attention heads were set at 16. The embedding dimension was set at 80, partly due to memory concerns. The convolutional layer is set at a kernel size of 3 and stride of 1 to preserve the output image dimension. The small kernel size preserves the quality of the image while correcting boundary artifacts generated by the ViT. The networks converged in 15 to 20 epochs, at which point the training was stopped. Ground truth is defined as the PICS reconstruction. The benchmark VarNet and MoDL networks are used with a setup informed by Blumenthal et al. [

34], with batch size set at 20.

3. Results

3.1. Image Scores

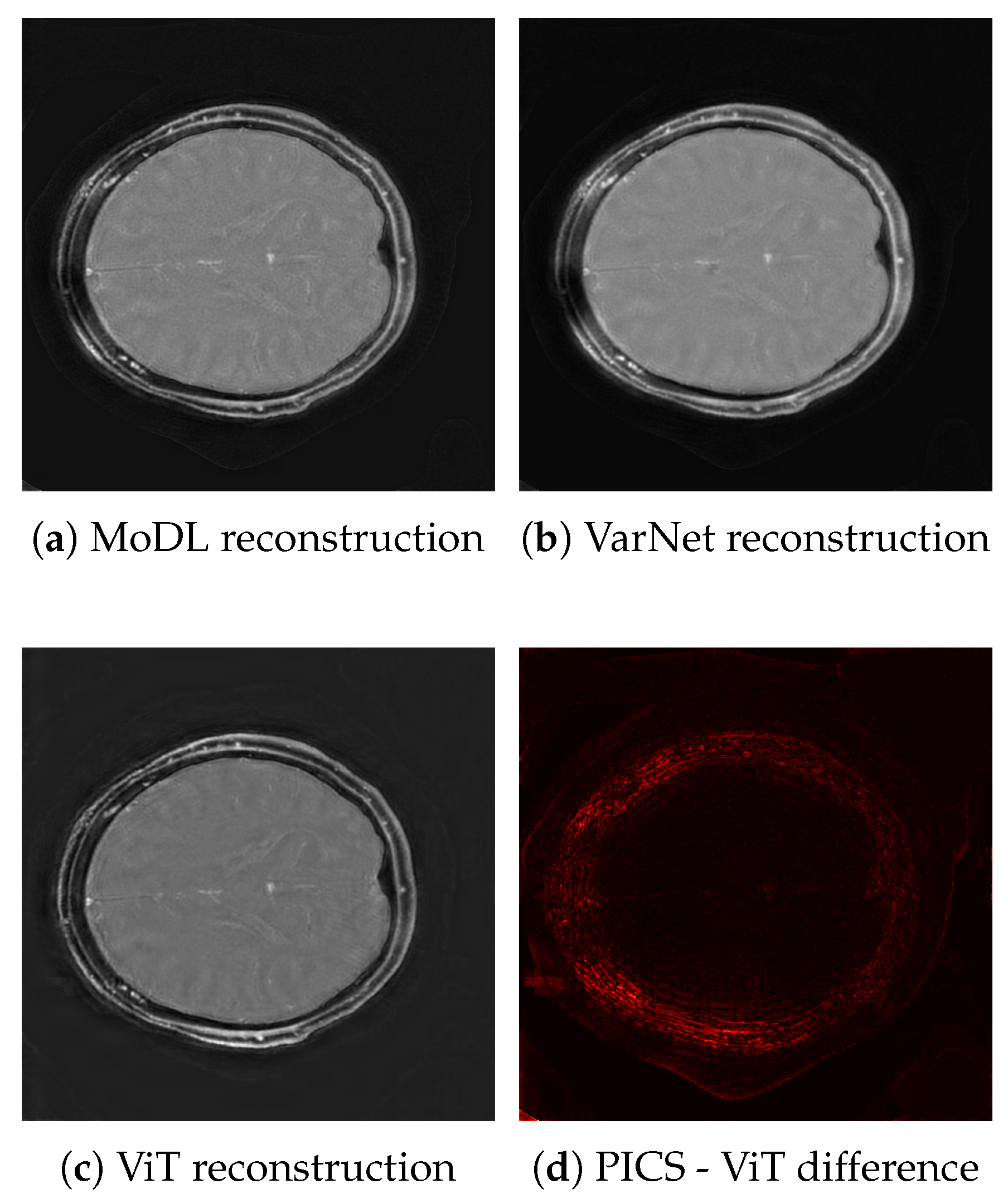

Table 3 shows various image quality metric results for the ViT pipeline against VarNet and ModL. The highest SSIM score is achieved by MoDL and the triply augmented ViT. The best NRMSE and PSNR scores are achieved by the ViT For NMI, the MoDL score is the highest. Notably, the ViT results have better NRMSE and PSNR scores even with little or no augmentation to the training data.

The image quality scores in

Table 3 demonstrate the advantages of the ViT pipeline across multiple metrics. The triply augmented ViT achieves comparable SSIM scores to MoDL while outperforming both VarNet and MoDL in terms of NRMSE and PSNR. The improvements in PSNR and NRMSE suggest that the ViT excels at preserving pixel intensity fidelity and reducing reconstruction noise. However, the lower NMI score indicates room for improvement in capturing fine inter-pixel relationships, particularly in regions of high structural complexity. Augmentation improves performance, as shown in the triply augmented model’s metrics, with higher PSNR values demonstrating reduced noise and enhanced clarity.

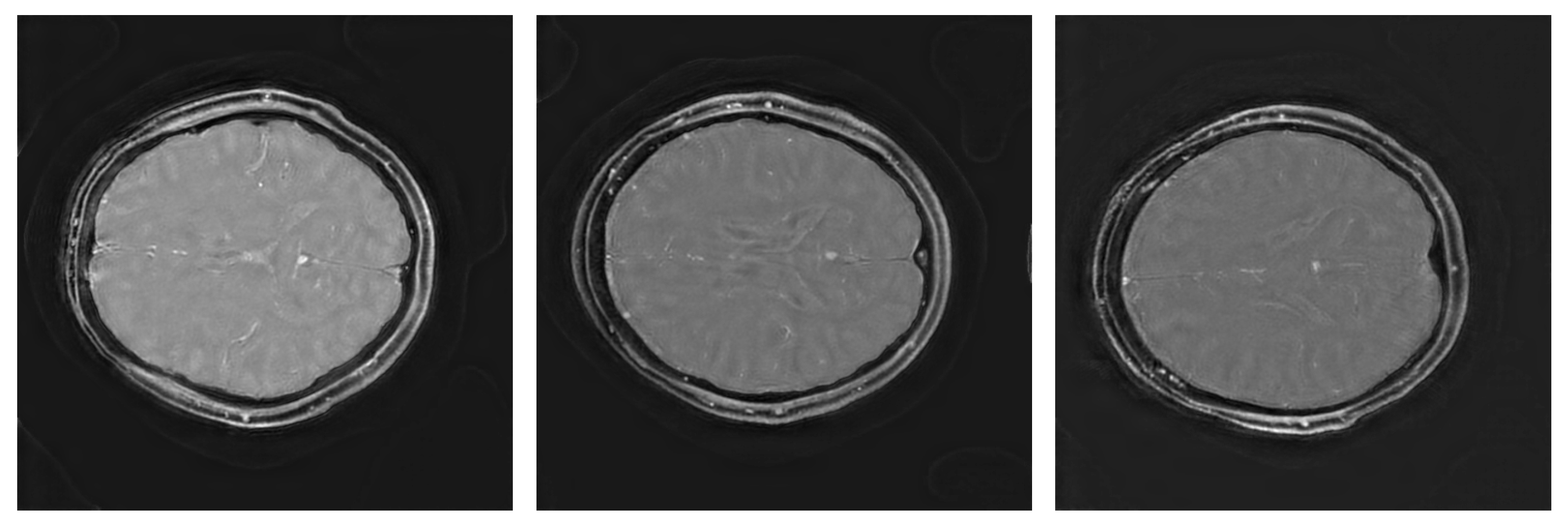

Figure 3 illustrates sample triply augmented ViT results from the network.

Figure 4 shows the same image reconstructed by VarNet, MoDL, and the ViT pipeline; the final subfigure shows the amplified difference between the PICS and the ViT reconstructions.

3.2. Network Runtime Performance

Table 4 highlights significant differences in runtime and resource efficiency among the models. The ViT pipeline demonstrates a marked advantage in processing speed, requiring 45 seconds per 10 images, compared to VarNet and MoDL, which take approximately 7 minutes each. This efficiency arises from the network’s strategy of refining an already approximate reconstruction rather than computing directly from raw k-space data.

The GPU memory footprint of the ViT pipeline lies between VarNet and MoDL. While its resource requirements (4895 MB) exceed those of VarNet, it remains significantly lower than MoDL’s usage.

4. Discussion

The results of this study illustrate the potential of using a Vision Transformer pipeline for the reconstruction of Rosette trajectory MRI data. The superior NRMSE and PSNR scores achieved by this method in comparison to methods such as VarNet and MoDL, even with low data augmentation, suggest that this approach is effective in preserving image fidelity (NRMSE, PSNR) and reducing noise (PSNR). The competitive results achieved with minimal or no augmentation highlight the ViT’s ability to generalize well from approximations and small datasets, which is crucial in medical imaging where large, well-annotated datasets are not always available. The SSIM and NMI scores indicate that while the method excels in certain metrics, there may be room for improvement in capturing fine structural details or maintaining overall structural integrity. Transformers, by nature, rely heavily on global contextual relationships, opening up the possibility to incorporate local attention mechanisms or CNN based strategies to capture finer details.

The increased runtime efficiency of the ViT framework suggests its suitability for real-time clinical applications, such as dynamic or 4D MRI, where processing speed is critical. Finally, further optimization of the network’s architecture could potentially reduce memory usage without compromising accuracy.

Investigating advanced augmentation techniques and more diverse datasets could improve the model’s robustness and generalization capabilities. The augmentation methods used, although simple (flipping, rotating, and color jitter), appear to have bolstered the model’s ability to generalize across different types of k-space data, as seen from the improved PSNR and NRMSE scores. Future work could investigate the impact of more complex augmentations, such as elastic transformations or non-uniform intensity scaling, which might further increase the robustness of the model in more diverse clinical scenarios.

While the results demonstrate strong performance on axial brain images, the generalizability of these findings to other MRI protocols (such as differing field strengths, acquisition times, or anatomical features) remains to be explored. Additionally, evaluating the ViT’s performance across different k-space trajectories, such as radial or spiral acquisitions, would further validate its robustness across diverse MRI applications. Incorporating more sophisticated initial approximations or iterative refinement steps within the ViT framework may also yield improvements. Finally, extending the evaluation of these methods to different types of MRI data, including dynamic and functional MRI, and assessing their performance in real-time applications will be crucial for translating these advancements into practical clinical tools. This approach could be particularly advantageous in exploring 3D or 4D MRI applications, as the transformer self-attention capability can naturally extend to higher dimensions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.E. and U.B.; methodology, U.E., U.B., and M.Y.; software, U.E. and M.Y.; validation, M.Y.; formal analysis, M.Y.; investigation, M.Y.; resources, C.O, U.E., O.O, and U.B.; data curation, U.E., O.O, and M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.O., U.E, U.B; visualization, M.Y.; supervision, C.O., U.E, and U.B.; project administration, C.O.; funding acquisition, C.O, O.O., U.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The MRI data used in this study are not available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by TÜBİTAK (Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye) and the TÜBİTAK 2244-118C129 fellowship program sponsored by Onur Ozyurt and the Telemed Company. The authors would like to acknowledge valuable support from the Wellcome Trust Collaborative Award (223131/Z/21/Z) awarded to Uzay Emir and Onur Ozyurt, computational resources generously allowed by the Ulas Bagci AI Group Machine and Hybrid Intelligence Lab and the Quest High-Performance Computing Cluster at Northwestern University, the Bogazici University Department of Biomedical Engineering, and the Bogazici University Life Sciences and Technologies Application and Research Center.

References

- Geethanath, S.; Vaughan Jr, J.T. Accessible magnetic resonance imaging: A review. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2019, 49, e65–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moratal, D.; Vallés-Luch, A.; Martí-Bonmatí, L.; Brummer, M.E. k-Space tutorial: an MRI educational tool for a better understanding of k-space. Biomedical imaging and intervention journal 2008, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, T.A.; Nemeth, A.J.; Hacein-Bey, L. An introduction to the Fourier transform: relationship to MRI. American journal of roentgenology 2008, 190, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, K.G. Reducing acquisition time in clinical MRI by data undersampling and compressed sensing reconstruction. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2015, 60, R297. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, K.L.; Hamilton, J.I.; Griswold, M.A.; Gulani, V.; Seiberlich, N. Non-Cartesian parallel imaging reconstruction. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2014, 40, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.J.; Johnson, P.M.; Knoll, F.; Lui, Y.W. Artificial Intelligence for MR Image Reconstruction: An Overview for Clinicians. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2021, 53, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geethanath, S.; Reddy, R.; Konar, A.S.; Imam, S.; Sundaresan, R.; R. , R.B.D.; Venkatesan, R. Compressed Sensing MRI: A Review. Critical Reviews™ in Biomedical Engineering 2013, 41, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.C. Compressed sensing MRI: a review from signal processing perspective. BMC Biomedical Engineering 2019, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Rathi, Y. A review and experimental evaluation of deep learning methods for MRI reconstruction. The journal of machine learning for biomedical imaging 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Dong, B. A review on deep learning in medical image reconstruction. Journal of the Operations Research Society of China 2020, 8, 311–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Schönlieb, C.B.; Liò, P.; Leiner, T.; Dragotti, P.L.; Wang, G.; Rueckert, D.; Firmin, D.; Yang, G. AI-based reconstruction for fast MRI—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Proceedings of the IEEE 2022, 110, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Cheng, J.; Ke, Z.; Ying, L. Deep magnetic resonance image reconstruction: Inverse problems meet neural networks. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2020, 37, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.S.; Bran Lorenzana, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Bollmann, S.; Crozier, S. Deep learning in magnetic resonance image reconstruction. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology 2021, 65, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalt-Tordera, J.; Muthurangu, V.; Hauptmann, A.; Steeden, J.A. Machine learning in magnetic resonance imaging: image reconstruction. Physica Medica 2021, 83, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammernik, K.; Klatzer, T.; Kobler, E.; Recht, M.P.; Sodickson, D.K.; Pock, T.; Knoll, F. Learning a variational network for reconstruction of accelerated MRI data. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2018, 79, 3055–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhu, J.; Yang, G. Which GAN? A comparative study of generative adversarial network-based fast MRI reconstruction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2021, 379, 20200203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Schlemper, J.; Dey, N.; Salehi, S.S.M.; Sheth, K.; Liu, C.; Duncan, J.S.; Sofka, M. Dual-domain self-supervised learning for accelerated non-Cartesian MRI reconstruction. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 81, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, J.A. On NUFFT-based gridding for non-Cartesian MRI. Journal of magnetic resonance 2007, 188, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xiao, T.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, H. Deep learning for fast MR imaging: A review for learning reconstruction from incomplete k-space data. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 68, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, A.; Zbontar, J.; Murrell, T.; Defazio, A.; Zitnick, C.L.; Yakubova, N.; Knoll, F.; Johnson, P. End-to-end variational networks for accelerated MRI reconstruction. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2020: 23rd International Conference, Lima, Peru, 2020, Proceedings, Part II 23. Springer, 2020, October 4–8; pp. 64–73.

- Aggarwal, H.K.; Mani, M.P.; Jacob, M. MoDL: Model-based deep learning architecture for inverse problems. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2018, 38, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Heckel, R. Vision Transformers Enable Fast and Robust Accelerated MRI. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The 5th International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning; Konukoglu, E.; Menze, B.; Venkataraman, A.; Baumgartner, C.; Dou, Q.; Albarqouni, S., Eds. PMLR, 06–08 Jul 2022, Vol. 172, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp.

- Parvaiz, A.; Khalid, M.A.; Zafar, R.; Ameer, H.; Ali, M.; Fraz, M.M. Vision Transformers in medical computer vision—A contemplative retrospection. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 122, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, D.; Christodoulou, A.G. Data-consistent non-Cartesian deep subspace learning for efficient dynamic MR image reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Monga, A.; de Moura, H.L.; Zhang, X.; Zibetti, M.V.; Regatte, R.R. Emerging trends in fast MRI using deep-learning reconstruction on undersampled k-space data: a systematic review. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Özen, A.C.; Sunjar, A.; Ilbey, S.; Sawiak, S.; Shi, R.; Chiew, M.; Emir, U. Ultra-short T2 components imaging of the whole brain using 3D dual-echo UTE MRI with rosette k-space pattern. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2023, 89, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Jia, S.; Zhou, Z. Analysis of generalized rosette trajectory for compressed sensing MRI. Medical physics 2015, 42, 5530–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholz, E.K.; Song, J.; Johnson, G.A.; Hancu, I. Multispectral imaging with three-dimensional rosette trajectories. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2008, 59, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Özen, A.C.; Sunjar, A.; Ilbey, S.; Shi, R.; Chiew, M.; Emir, U. Myelin Imaging Using Dual-echo 3D Ultra-short Echo Time MRI with Rosette k-Space Pattern. bioRxiv, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, S.Z.; Denney, T.S.; Bashir, A. Feasibility of spinal cord imaging at 7 T using rosette trajectory with magnetization transfer preparation and compressed sensing. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 8777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcicek, S.; Craig-Craven, A.R.; Shen, X.; Chiew, M.; Ozen, A.; Sawiak, S.; Pilatus, U.; emir, u. Multi-site ultrashort echo time 3D phosphorous MRSI repeatability using novel rosette trajectory (PETALUTE). bioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929, arXiv:2010.11929 2020.

- Zhang, C.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, C. Transformer and CNN hybrid deep neural network for semantic segmentation of very-high-resolution remote sensing imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, M.; Luo, G.; Schilling, M.; Holme, H.C.M.; Uecker, M. Deep, deep learning with BART. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2023, 89, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980, arXiv:1412.6980 2014.

- Smith, L.N.; Topin, N. Super-convergence: Very fast training of neural networks using large learning rates. In Proceedings of the Artificial intelligence and machine learning for multi-domain operations applications. SPIE, Vol. 11006; 2019; pp. 369–386. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).