Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Micropollutants in Aquatic Ecosystems

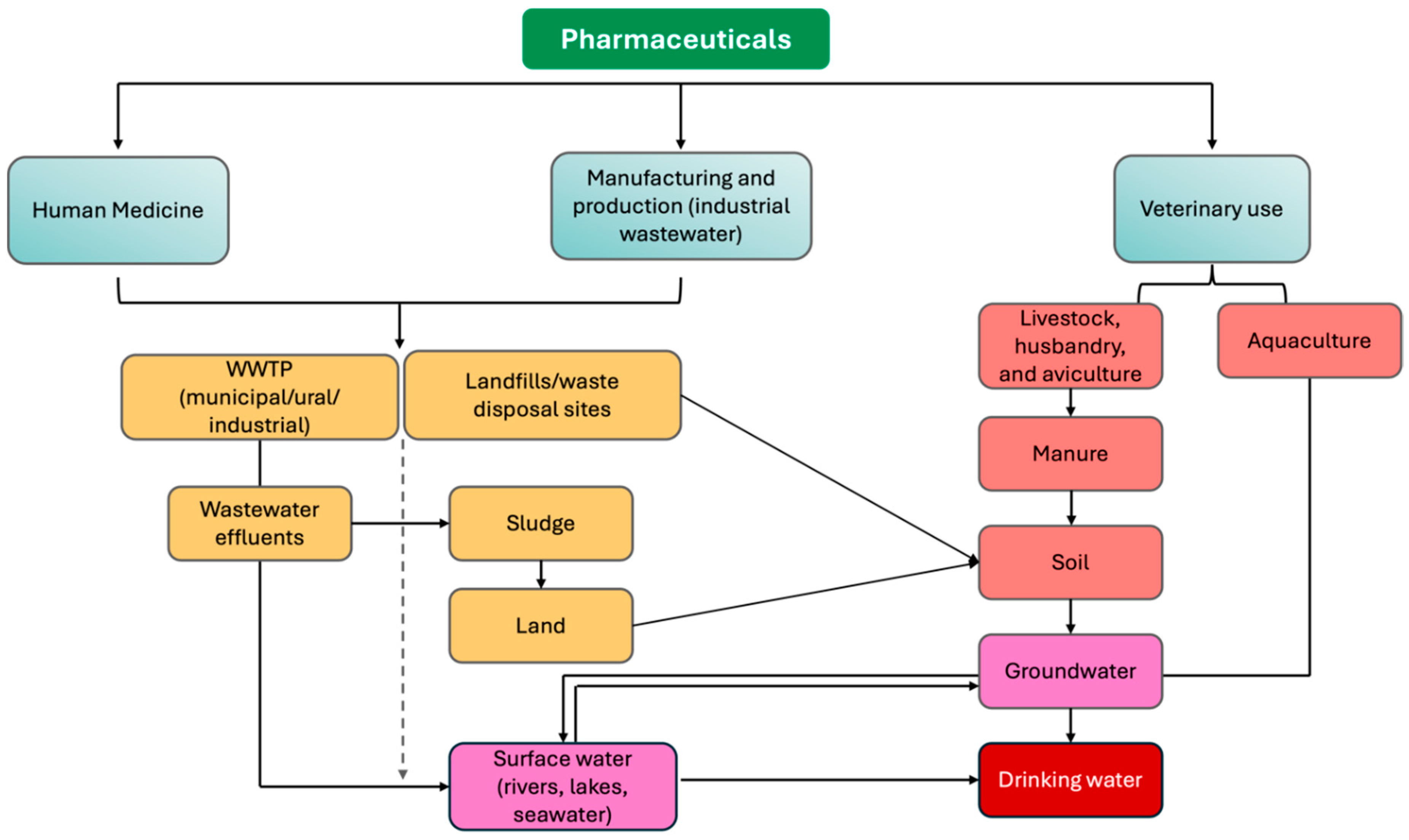

2.1. Sources of Micropollutants

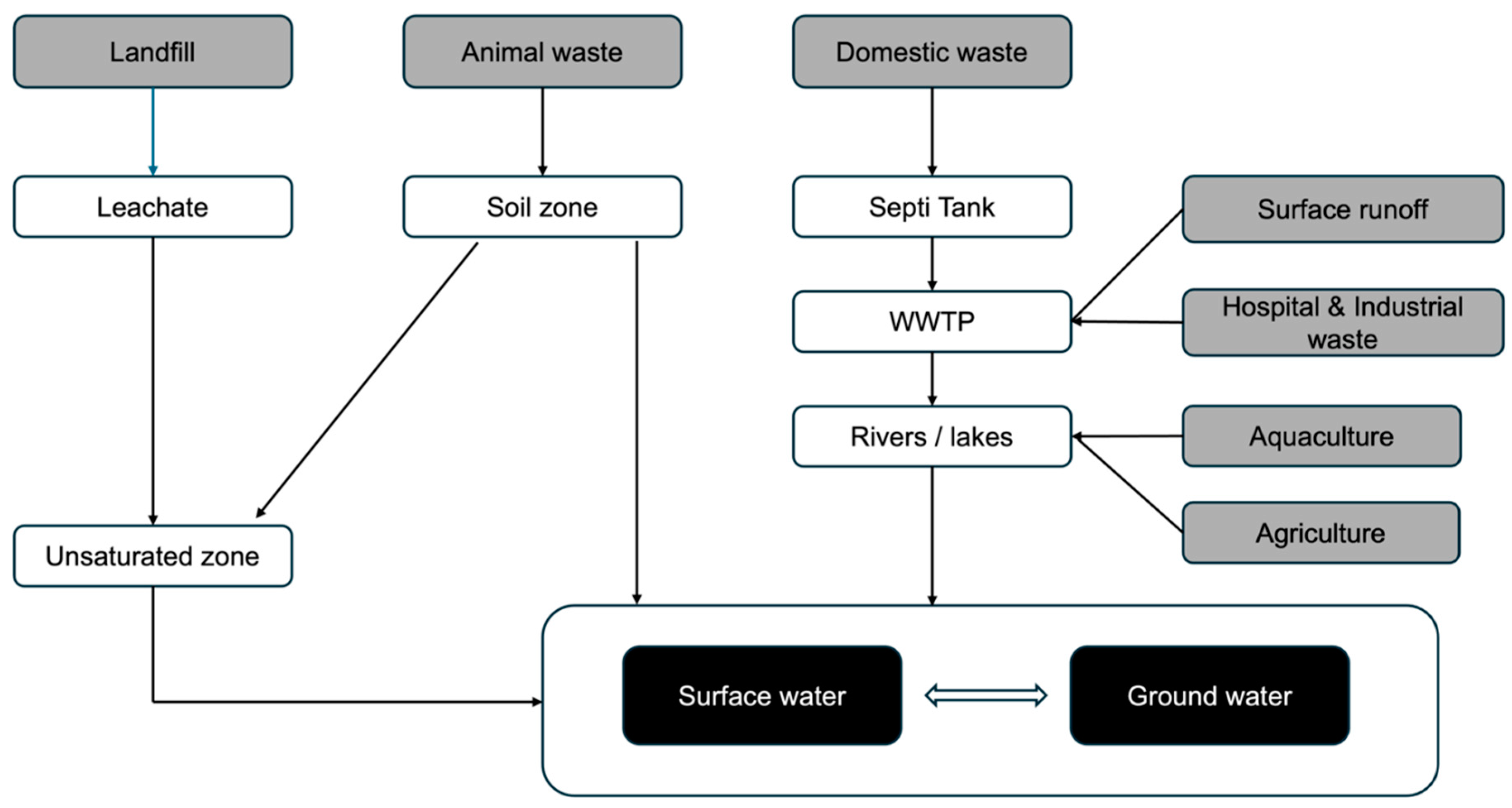

2.2. Routes of Micropollutants in the Environment

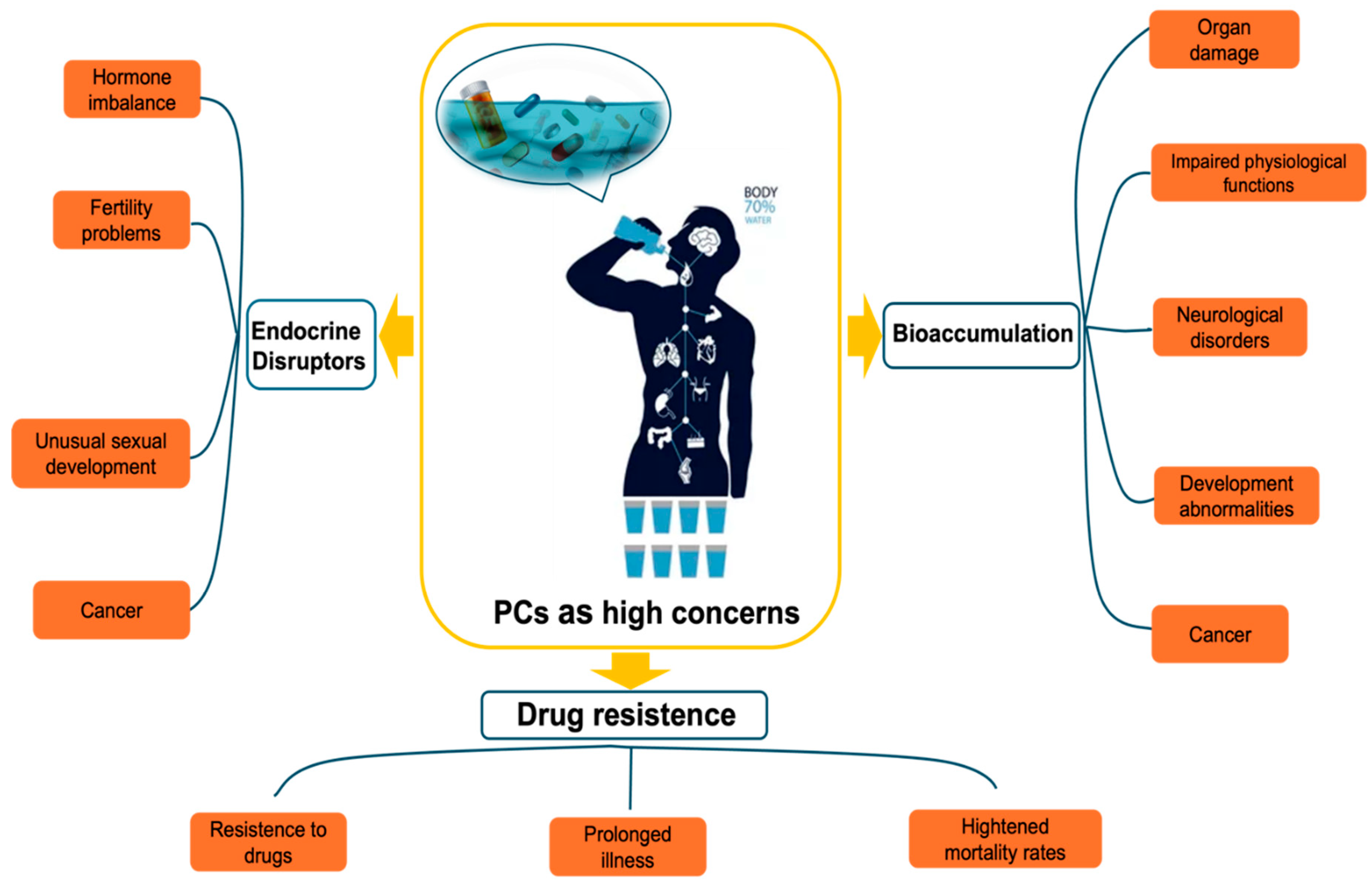

2.3. Impact of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PhACs) in Water on Human Health and Ecosystems

2.3.1. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

2.3.2. Antibiotics

2.3.3. Antidepressants

3. Presence of Micropollutants in the Aquatic Environment

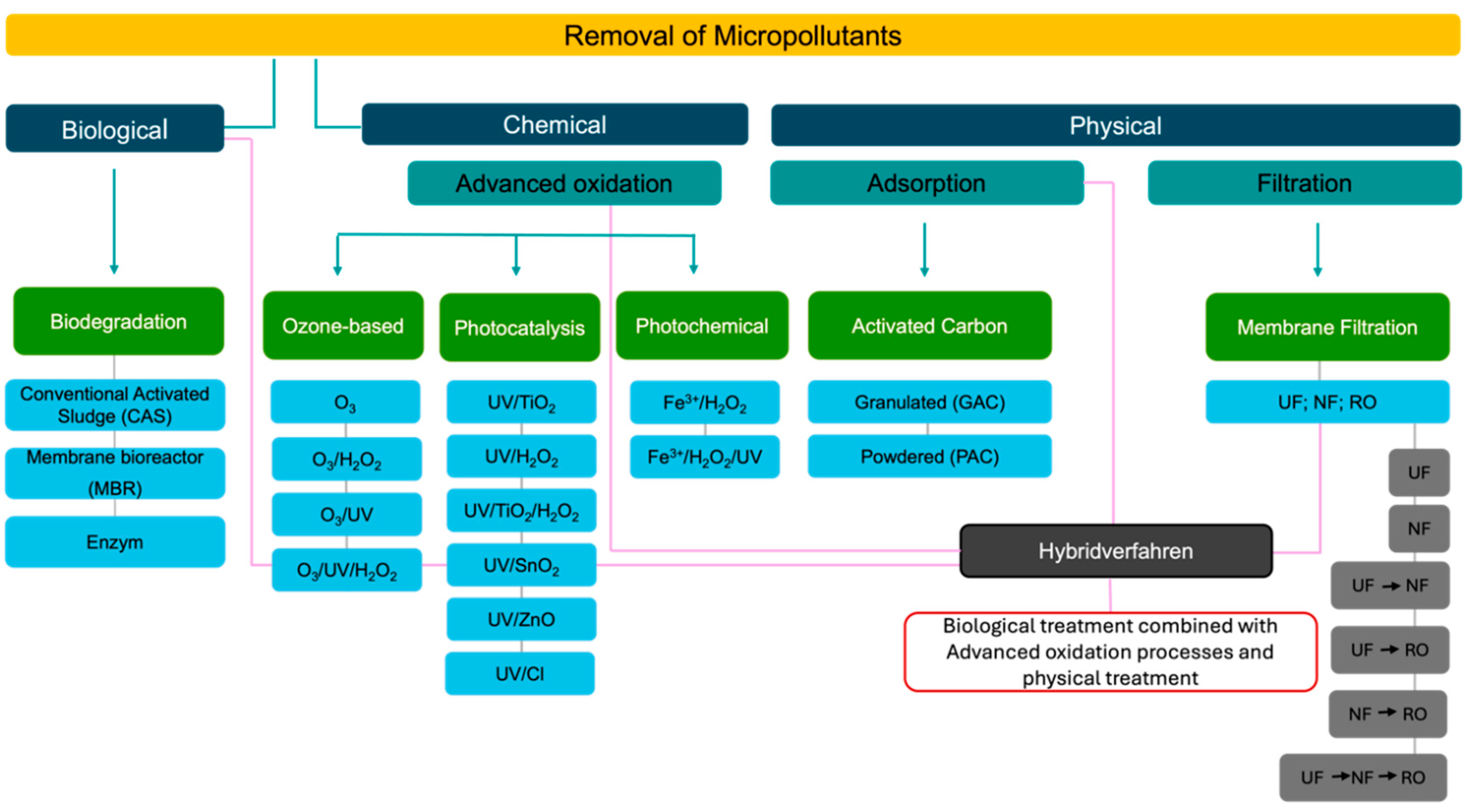

4. Techniques for the Removal of Pharmaceutical Contaminants

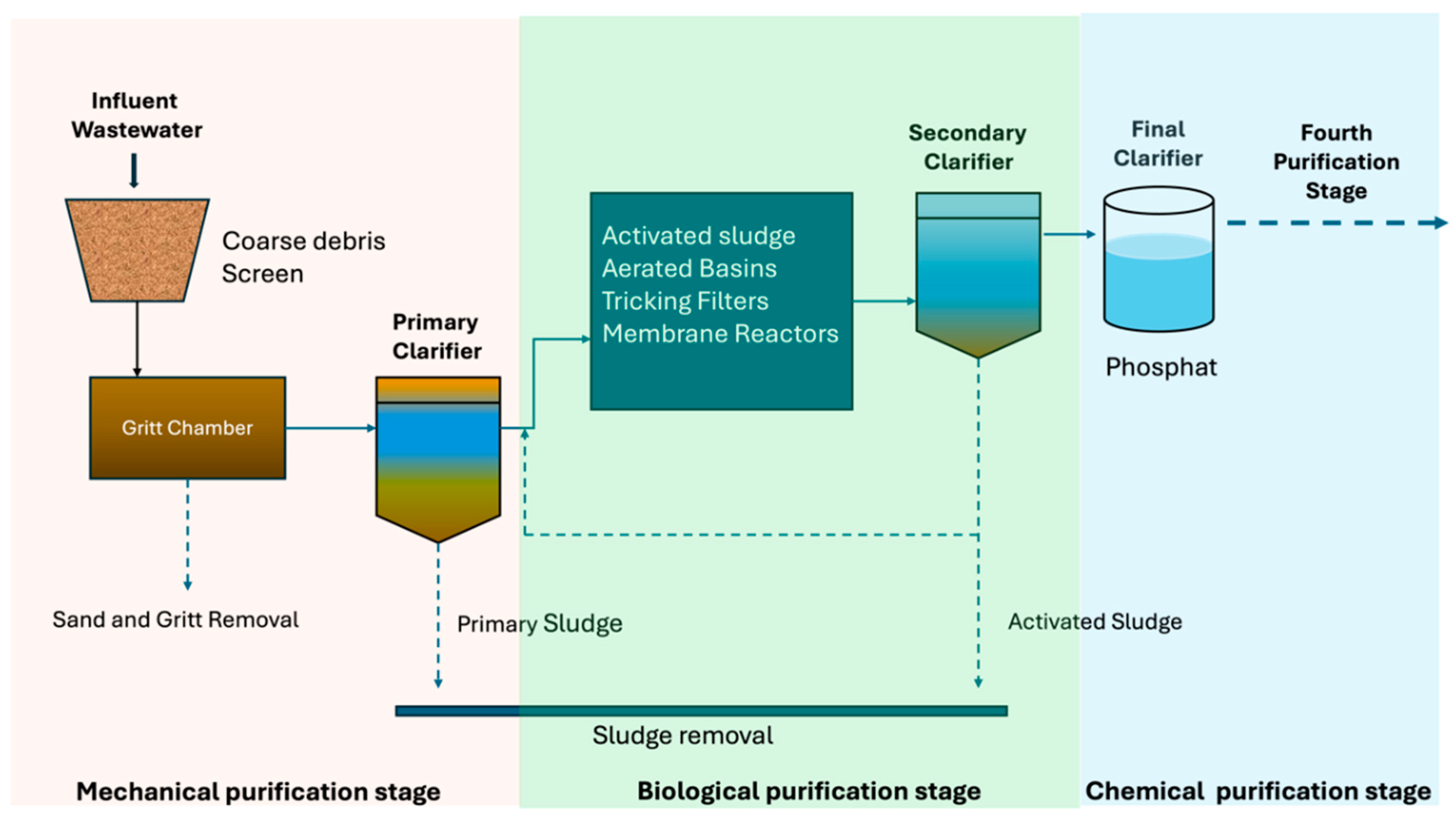

4.1. WWTPs Today

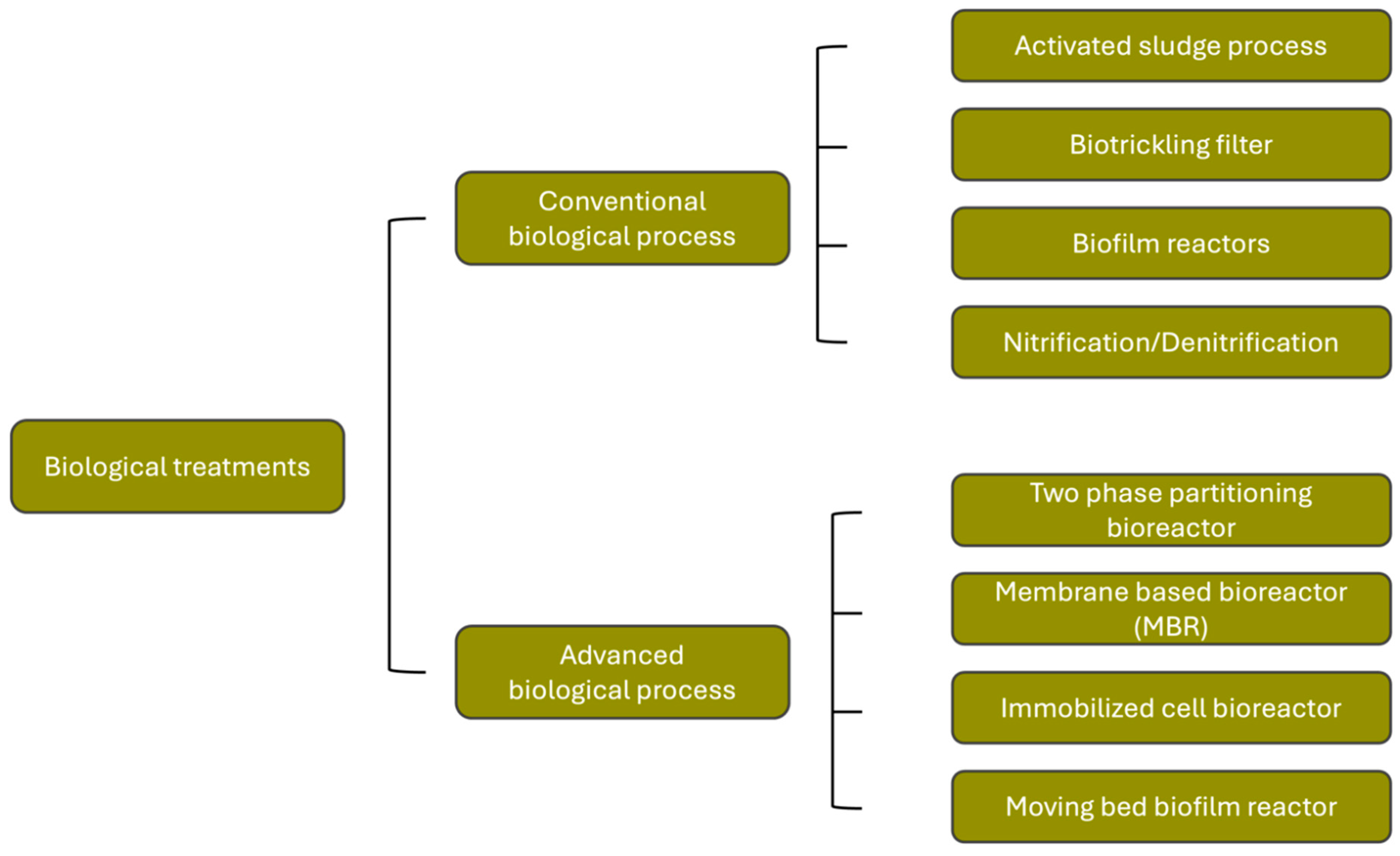

4.2. Biological Treatment Technologies

4.2.1. Conventional Biological Processes

4.2.1.1. Activated Sludge

4.2.2. Advanced Biological Processes

4.2.2.1. Membrane Bioreactor

4.3. Adsorptive Treatment Technologies

4.3.1. Activated Carbon Adsorption

4.4. Physical Treatments Technologies

4.4.1. Membrane Technology

4.4.1.1. Removal Mechanism of PCs by Membrane Separation Processes

4.4.1.2. MF and UF

4.4.1.3. NF and RO

4.5. Chemical Treatment Technologies

4.5.1. Oxidative Treatment Technologies for Pharmaceutical Contaminants

4.5.1.1. Ozonation

4.5.1.2. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs)

4.5. Hybrid Technologies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Activated Carbon |

| AnMBRs | Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactors |

| AOP | Advanced Oxidation Products |

| BEMRs | Bio-electrochemical Membrane Bioreactors |

| CAFOs | Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations |

| CAS | Conventional Activated Sludge |

| ECs | Emerging Contaminants |

| EDCs | Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals |

| FO | Forward Osmosis |

| GAC | Granular Activated Carbon |

| HRMBRs | High Retention Membrane Bioreactors |

| HRMBRs | High Retention Membrane Bioreactors |

| KOW | Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient |

| MBR | Membrane Bioreactor |

| MD | Membrane Distillation |

| MF | Microfiltration |

| MIPs | Molecular Imprinted Polymers |

| MLSS | Mixed Liquor Suspended Solids |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| MWCO | Molecular Weight Cut-Off |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| NSAIDs | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| OMBRs | Osmotic Membrane Bioreactors |

| PCs | Pharmaceuticals Contaminants |

| PAC | Powdered Activated Carbon |

| PhACs | Pharmaceutically Active Compounds |

| PPCPs | Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products |

| PCPs | Personal Care Products |

| PKa | The Acid Dissociation Constant |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| SRT | Sludge Retention Time |

| TMP | Transmembrane Pressure |

| TrOCs | Trace Organic Contaminants |

| UF | Ultrafiltration |

| WWTPs | Wastewater Treatment Plants |

References

- Khanzada, N.K.; Farid, M.U.; Kharraz, J.A.; Choi, J.; Tang, C.Y.; Nghiem, L.D.; Am Jang; An, A. K. Removal of organic micropollutants using advanced membrane-based water and wastewater treatment: A review. Journal of Membrane Science 2020, 598, 117672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H.; Nghiem, L.D.; Hai, F.I.; Zhang, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.C. A review on the occurrence of micropollutants in the aquatic environment and their fate and removal during wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 473-474, 619–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojajuni, O.; Saroj, D.; Cavalli, G. Removal of organic micropollutants using membrane-assisted processes: a review of recent progress. Environmental Technology Reviews 2015, 4, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naushad, M.; Govarthanan, M.; Iqbal, J.; Alfadul, S.M. Emerging contaminants of high concern for the environment: Current trends and future research. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Shen, X.; Jiang, W.; Xi, Y.; Li, S. Comprehensive review of emerging contaminants: Detection technologies, environmental impact, and management strategies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M.; Demnerová, K.; Aamand, J.; Agathos, S.; Fava, F. Emerging pollutants in the environment: present and future challenges in biomonitoring, ecological risks and bioremediation. N. Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, N.A.; Shahid, S.U.; Majid, M.; Tahir, A. Introduction to environmental micropollutants. Environmental Micropollutants; Elsevier, 2022; pp 1–12, ISBN 9780323905558.

- Silva, L.L.S.; Moreira, C.G.; Curzio, B.A.; da Fonseca, F.V. Micropollutant Removal from Water by Membrane and Advanced Oxidation Processes—A Review. JWARP 2017, 09, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bila, D.M.; Dezotti, M. Desreguladores endócrinos no meio ambiente: efeitos e conseqüências. Quím. Nova 2007, 30, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bila, D.M.; Dezotti, M. Fármacos no meio ambiente. Quím. Nova 2003, 26, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhaya; Raychoudhury, T.; Prajapati, S.K. Bioremediation of Pharmaceuticals in Water and Wastewater. In Microbial Bioremediation & Biodegradation; Shah, M.P., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp 425–446, ISBN 978-981-15-1811-9.

- Kim, M.-K.; Zoh, K.-D. Occurrence and removals of micropollutants in water environment. Environmental Engineering Research 2016, 21, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, F.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Farooq, U.; Rehman, Z.U.; Hmeed, M.U.; Batool, R.; Pongpiachan, S. Nanotechnology to treat the environmental micropollutants. Environmental Micropollutants; Elsevier, 2022; pp 407–441, ISBN 9780323905558.

- Fent, K.; Weston, A.A.; Caminada, D. Ecotoxicology of human pharmaceuticals. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006, 76, 122–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruden, A.; Pei, R.; Storteboom, H.; Carlson, K.H. Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants: studies in northern Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 7445–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive - 2000/60 - EN - Water Framework Directive - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj/eng (accessed on 27 January 2025.849Z).

- Richtlinie - 2008/105 - EN - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?qid=1579847753838&uri=CELEX:32008L0105 (accessed on 27 January 2025.022Z).

- Dosis, I.; Ricci, M.; Majoros, L.; Lava, R.; Emteborg, H.; Held, A.; Emons, H. Addressing Analytical Challenges of the Environmental Monitoring for the Water Framework Directive: ERM-CE100, a New Biota Certified Reference Material. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2514–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhaus, T. Commentary on the EU Commission’s proposal for amending the Water Framework Directive, the Groundwater Directive, and the Directive on Environmental Quality Standards. Environ Sci Eur 2023, 35, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive - 2013/39 - EN - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2013/39/oj (accessed on 27 January 2025.613Z).

- M. Ahting, F. Brauer, A. Duffek, I. Ebert, A. Eckhardt, E. Hassold, M. Helmecke, I. Kirst, B. Krause, P. Lepom, S. Leuthold, C. Mathan,V. Mohaupt, J.F. Moltmann, A. Müller, I. Nöh,C. Pickl, U. Pirntke, K. Pohl, J. Rechenberg, M. SuhrC. Thierbach, L. Tietjen, P. Von der Ohe, C. Winde. Recommendations for reducing micropollutants in waters 2017.

- Barbosa, M.O.; Moreira, N.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Silva, A.M.T. Occurrence and removal of organic micropollutants: An overview of the watch list of EU Decision 2015/495. Water Res. 2016, 94, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M. de; Atalla, A.A.; Frihling, B.E.F.; Cavalheri, P.S.; Migliolo, L.; Filho, F.J.C.M. Ibuprofen and caffeine removal in vertical flow and free-floating macrophyte constructed wetlands with Heliconia rostrata and Eichornia crassipes. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 373, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Zambello, E. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in urban wastewater: removal, mass load and environmental risk after a secondary treatment--a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margot, J.; Rossi, L.; Barry, D.A.; Holliger, C. A review of the fate of micropollutants in wastewater treatment plants. WIREs Water 2015, 2, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamta; Bhushan, S.; Rana, M.S.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Simsek, H.; Prajapati, S.K. Algae- and bacteria-driven technologies for pharmaceutical remediation in wastewater. Removal of Toxic Pollutants Through Microbiological and Tertiary Treatment; Elsevier, 2020; pp 373–408, ISBN 9780128210147.

- Gil, A.; García, A.M.; Fernández, M.; Vicente, M.A.; González-Rodríguez, B.; Rives, V.; Korili, S.A. Effect of dopants on the structure of titanium oxide used as a photocatalyst for the removal of emergent contaminants. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2017, 53, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Q.; Cho, S.J.; Li, Y.; Venkatesh, S. Prediction of aqueous solubility of organic compounds using a quantitative structure-property relationship. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002, 91, 1838–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleuvers, M. Mixture toxicity of the anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and acetylsalicylic acid. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2004, 59, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aherne, G.W.; Briggs, R. The relevance of the presence of certain synthetic steroids in the aquatic environment. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1989, 41, 735–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feier, B.; Gui, A.; Cristea, C.; Săndulescu, R. Electrochemical determination of cephalosporins using a bare boron-doped diamond electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 976, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CARMICHAEL, W. The Cyanotoxins. Incorporating in Plant Pathology - Classic Papers; Elsevier, 1997; pp 211–256, ISBN 9780120059270.

- Costanzo, S.D.; Murby, J.; Bates, J. Ecosystem response to antibiotics entering the aquatic environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 51, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulrazaq Yahaya*, Friday, J. Sale and Umar M. Salehdeen. Analytical Methods for Determination of Regulated and Unregulated Disinfection By- Products in Drinking Water: A Review. 2019, 25–36. [CrossRef]

- Samal, K.; Mahapatra, S.; Hibzur Ali, M. Pharmaceutical wastewater as Emerging Contaminants (EC): Treatment technologies, impact on environment and human health. Energy Nexus 2022, 6, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooty, J.M.; Srinivasulu, M.; Mosquera, J.A.N.; Llaguno, S.N.S. Occurrence and fate of micropollutants in surface waters. Environmental Micropollutants; Elsevier, 2022; pp 233–269, ISBN 9780323905558.

- Tiwari, B.; Sellamuthu, B.; Ouarda, Y.; Drogui, P.; Tyagi, R.D.; Buelna, G. Review on fate and mechanism of removal of pharmaceutical pollutants from wastewater using biological approach. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 224, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Esposito, G.; Oturan, M.A. Removal of residual anti-inflammatory and analgesic pharmaceuticals from aqueous systems by electrochemical advanced oxidation processes. A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2013, 228, 944–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheran, M.; Brar, S.K.; Verma, M.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Zhang, T.C.; Valero, J.R. Membrane processes for removal of pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) from water and wastewaters. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 547, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-L.; Wong, M.-H. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs): a review on environmental contamination in China. Environ. Int. 2013, 59, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esplugas, S.; Bila, D.M.; Krause, L.G.T.; Dezotti, M. Ozonation and advanced oxidation technologies to remove endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in water effluents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 149, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.; Nghiem, L.; Hai, F.; Zhang, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, X. A review on the occurrence of micropollutants in the aquatic environment and their fate and removal during wastewater treatment. 2014, 473-474, 619–641. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fourcade, F.; Amrane, A.; Geneste, F. Removal of Iodine-Containing X-ray Contrast Media from Environment: The Challenge of a Total Mineralization. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.H.; Rahman, A.u.; Zuljalal, F.; Saeed, T.; Aziz, S.; Ilyas, M. Food additives as environmental micropollutants. Environmental Micropollutants; Elsevier, 2022; pp 63–79, ISBN 9780323905558.

- Panda, B.P.; Majhi, B.K.; Parida, S.P. Occurrence and fate of micropollutants in water bodies. Environmental Micropollutants; Elsevier, 2022; pp 271–293, ISBN 9780323905558.

- Stefanakis, A.I.; Becker, J.A. A Review of Emerging Contaminants in Water. In Waste Management; Management Association, I.R., Ed.; IGI Global, 2020; pp 177–202, ISBN 9781799812104.

- Lamastra, L.; Balderacchi, M.; Trevisan, M. Inclusion of emerging organic contaminants in groundwater monitoring plans. MethodsX 2016, 3, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ternes, T.; Joss, A. Human Pharmaceuticals, Hormones and Fragrances - The Challenge of Micropollutants in Urban Water Management. Water Intelligence Online 2006, 5, 9781780402468–9781780402468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besse, J.-P.; Kausch-Barreto, C.; Garric, J. Exposure Assessment of Pharmaceuticals and Their Metabolites in the Aquatic Environment: Application to the French Situation and Preliminary Prioritization. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 2008, 14, 665–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz de García, S.; Pinto Pinto, G.; García Encina, P.; Irusta Mata, R. Consumption and occurrence of pharmaceutical and personal care products in the aquatic environment in Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 444, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küster, A.; Adler, N. Pharmaceuticals in the environment: scientific evidence of risks and its regulation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikehata, K.; Jodeiri Naghashkar, N.; Gamal El-Din, M. Degradation of Aqueous Pharmaceuticals by Ozonation and Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Review. Ozone: Science & Engineering 2006, 28, 353–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, A.; Mazumder, P.; Tyagi, V.K.; Tushara Chaminda, G.G.; An, A.K.; Kumar, M. Occurrence and fate of emerging contaminants in water environment: A review. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2018, 6, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-Q.; Zhou, Z.; Sharma, V.K. Occurrence, transportation, monitoring and treatment of emerging micro-pollutants in waste water — A review from global views. Microchemical Journal 2013, 110, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdeville, M.J.; Budzinski, H. Trace-level analysis of organic contaminants in drinking waters and groundwaters. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2011, 329, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, O.F.S.; Palaniandy, P.; Aziz, H.A. Fate of common pharmaceuticals in the environment. The Treatment of Pharmaceutical Wastewater; Elsevier, 2023; pp 69–148, ISBN 9780323991605.

- Pereira, A.; Silva, L.; Laranjeiro, C.; Lino, C.; Pena, A. Selected Pharmaceuticals in Different Aquatic Compartments: Part I-Source, Fate and Occurrence. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, P.H.; Thomas, K.V. The occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters of the lower Tyne catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 356, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gros, M.; Petrović, M.; Ginebreda, A.; Barceló, D. Removal of pharmaceuticals during wastewater treatment and environmental risk assessment using hazard indexes. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortúzar, M.; Esterhuizen, M.; Olicón-Hernández, D.R.; González-López, J.; Aranda, E. Pharmaceutical Pollution in Aquatic Environments: A Concise Review of Environmental Impacts and Bioremediation Systems. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 869332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, L.; Chang, A.C. Seasonal variation of endocrine disrupting compounds, pharmaceuticals and personal care products in wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 442, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Lin, W.; Gao, Z.; Ren, Y. Use of selected NSAIDs in Guangzhou and other cities in the world as identified by wastewater analysis. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Jaimes, J.A.; Postigo, C.; Melgoza-Alemán, R.M.; Aceña, J.; Barceló, D.; López de Alda, M. Study of pharmaceuticals in surface and wastewater from Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico: Occurrence and environmental risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613-614, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Rønning, H.T.; Alarif, W.; Kallenborn, R.; Al-Lihaibi, S.S. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in effluent-dominated Saudi Arabian coastal waters of the Red Sea. Chemosphere 2017, 175, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.D.S.; Maranho, L.A.; Cortez, F.S.; Pusceddu, F.H.; Santos, A.R.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Cesar, A.; Guimarães, L.L. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and cocaine in a Brazilian coastal zone. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 548-549, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, A.; Manzoor, M.; Gul, I.; Zafar, R.; Jamil, H.I.; Niazi, A.K.; Ali, M.A.; Park, T.J.; Arshad, M. Phytotoxicity of different antibiotics to rice and stress alleviation upon application of organic amendments. Chemosphere 2020, 258, 127353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, R.; Bashir, S.; Nabi, D.; Arshad, M. Occurrence and quantification of prevalent antibiotics in wastewater samples from Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.-Q.; Ying, G.-G.; Pan, C.-G.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zhao, J.-L. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China: source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 6772–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, M.; Chu, L.M. Fate of antibiotics in soil and their uptake by edible crops. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599-600, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, N.; Sun, P.; Sun, Q.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Ji, X.; Zou, H.; Ottoson, J.; Nilsson, L.E.; Berglund, B.; et al. Presence of antibiotic residues in various environmental compartments of Shandong province in eastern China: Its potential for resistance development and ecological and human risk. Environ. Int. 2018, 114, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, O.; Porcher, J.-M.; Sanchez, W. Factory-discharged pharmaceuticals could be a relevant source of aquatic environment contamination: review of evidence and need for knowledge. Chemosphere 2014, 115, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combalbert, S.; Bellet, V.; Dabert, P.; Bernet, N.; Balaguer, P.; Hernandez-Raquet, G. Fate of steroid hormones and endocrine activities in swine manure disposal and treatment facilities. Water Res. 2012, 46, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantziaras, I.; Boyen, F.; Callens, B.; Dewulf, J. Correlation between veterinary antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in food-producing animals: a report on seven countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, R.S.; Sibley, P.K. Human health risk assessment of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in plant tissue due to biosolids and manure amendments, and wastewater irrigation. Environ. Int. 2015, 75, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghrir, R.; Drogui, P. Tetracycline antibiotics in the environment: a review. Environ Chem Lett 2013, 11, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, A.H.; Tomova, A.; López, A.; Maldonado, M.A.; Henríquez, L.A.; Ivanova, L.; Moy, F.; Godfrey, H.P.; Cabello, F.C. Salmon aquaculture and antimicrobial resistance in the marine environment. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, F.C.; Godfrey, H.P.; Tomova, A.; Ivanova, L.; Dölz, H.; Millanao, A.; Buschmann, A.H. Antimicrobial use in aquaculture re-examined: its relevance to antimicrobial resistance and to animal and human health. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 1917–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Tang, J.; Zhang, G. Occurrence and distribution of antibiotics in the Beibu Gulf, China: impacts of river discharge and aquaculture activities. Mar. Environ. Res. 2012, 78, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Wang, Z.; Nie, X.; Yang, Y.; Pan, D.; Leung, A.O.W.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, K. Residues of fluoroquinolones in marine aquaculture environment of the Pearl River Delta, South China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2012, 34, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, A.; Phu, T.M.; Satapornvanit, K.; Min, J.; Shahabuddin, A.M.; Henriksson, P.J.G.; Murray, F.J.; Little, D.C.; Dalsgaard, A.; van den Brink, P.J. Use of veterinary medicines, feed additives and probiotics in four major internationally traded aquaculture species farmed in Asia. Aquaculture 2013, 412-413, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Liu, W. Occurrence, fate, and ecotoxicity of antibiotics in agro-ecosystems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, A.; Nebot, C.; Miranda, J.M.; Vázquez, B.I.; Cepeda, A. Detection and quantitative analysis of 21 veterinary drugs in river water using high-pressure liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2012, 19, 3235–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowieson, A.J.; Kluenter, A.M. Contribution of exogenous enzymes to potentiate the removal of antibiotic growth promoters in poultry production. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2019, 250, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.Y.; van Boeckel, T.P.; Martinez, E.M.; Pant, S.; Gandra, S.; Levin, S.A.; Goossens, H.; Laxminarayan, R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E3463–E3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, I.T.; Santos, L. Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: A review of the European scenario. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 736–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilurdoz, M.S. de; Sadhwani, J.J.; Reboso, J.V. Antibiotic removal processes from water & wastewater for the protection of the aquatic environment - a review. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 45, 102474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obimakinde, S.; Fatoki, O.; Opeolu, B.; Olatunji, O. Veterinary pharmaceuticals in aqueous systems and associated effects: an update. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 3274–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Choi, K. Comparison of regulatory frameworks of environmental risk assessments for human pharmaceuticals in EU, USA, and Canada. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 671, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, P.N.; Phung, V.-D.; Nguyen, T.B.H. Recent advances and future trends in metal oxide photocatalysts for removal of pharmaceutical pollutants from wastewater: a comprehensive review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Nuzhat, S.; Chowdhury, A.T.; Rafa, N.; Uddin, M.A.; Inayat, A.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Ong, H.C.; Chia, W.Y.; et al. Recent developments in physical, biological, chemical, and hybrid treatment techniques for removing emerging contaminants from wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillette, L.J.; Gross, T.S.; Masson, G.R.; Matter, J.M.; Percival, H.F.; Woodward, A.R. Developmental abnormalities of the gonad and abnormal sex hormone concentrations in juvenile alligators from contaminated and control lakes in Florida. Environ. Health Perspect. 1994, 102, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdom, C.E.; Hardiman, P.A.; Bye, V.V.J.; Eno, N.C.; Tyler, C.R.; Sumpter, J.P. Estrogenic Effects of Effluents from Sewage Treatment Works. Chemistry and Ecology 1994, 8, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Ali, M.H.; Samal, K. Assessment of compost maturity-stability indices and recent development of composting bin. Energy Nexus 2022, 6, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaider, L.A.; Rudel, R.A.; Ackerman, J.M.; Dunagan, S.C.; Brody, J.G. Pharmaceuticals, perfluorosurfactants, and other organic wastewater compounds in public drinking water wells in a shallow sand and gravel aquifer. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468-469, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S.; Ternes, T.; Gibert, M.; Olejniczak, K. Indirect human exposure to pharmaceuticals via drinking water. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 142, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiener, C. Occurrence and analysis of pharmaceuticals and their transformation products in drinking water treatment. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 1159–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, N.Z.; Salmiati, S.; Aris, A.; Salim, M.R.; Nazifa, T.H.; Muhamad, M.S.; Marpongahtun, M. A Review on Emerging Pollutants in the Water Environment: Existences, Health Effects and Treatment Processes. Water 2021, 13, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyumina, E.A.; Bazhutin, G.A.; Cartagena Gómez, A.d.P.; Ivshina, I.B. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs as Emerging Contaminants. Microbiology 2020, 89, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selderslaghs, I.W.T.; Blust, R.; Witters, H.E. Feasibility study of the zebrafish assay as an alternative method to screen for developmental toxicity and embryotoxicity using a training set of 27 compounds. Reprod. Toxicol. 2012, 33, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolliver, H.; Gupta, S. Antibiotic losses in leaching and surface runoff from manure-amended agricultural land. J. Environ. Qual. 2008, 37, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajeunesse, A.; Smyth, S.A.; Barclay, K.; Sauvé, S.; Gagnon, C. Distribution of antidepressant residues in wastewater and biosolids following different treatment processes by municipal wastewater treatment plants in Canada. Water Res. 2012, 46, 5600–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.D.; Chu, S.; Judt, C.; Li, H.; Oakes, K.D.; Servos, M.R.; Andrews, D.M. Antidepressants and their metabolites in municipal wastewater, and downstream exposure in an urban watershed. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, M.; Sharma, V. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. CMAJ 2017, 189, E747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Lader, M. A review of the management of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 5, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.; Locoro, G.; Contini, S. Occurrence of polar organic contaminants in the dissolved water phase of the Danube River and its major tributaries using SPE-LC-MS(2) analysis. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2325–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matamoros, V.; Arias, C.A.; Nguyen, L.X.; Salvadó, V.; Brix, H. Occurrence and behavior of emerging contaminants in surface water and a restored wetland. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Park, C.K.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, P. Seasonal variations of several pharmaceutical residues in surface water and sewage treatment plants of Han River, Korea. Science of The Total Environment 2008, 405, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, F.; Meng, F.; Xie, Y.; Chen, H.; Young, K.; Luo, W.; Ye, T.; Fu, W. Occurrence and fate of PPCPs and correlations with water quality parameters in urban riverine waters of the Pearl River Delta, South China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2013, 20, 5864–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, M.J.; Thomas, K.V. Determination of selected human pharmaceutical compounds in effluent and surface water samples by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 1015, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björklund, E.; Svahn, O. Total Release of 21 Indicator Pharmaceuticals Listed by the Swedish Medical Products Agency from Wastewater Treatment Plants to Surface Water Bodies in the 1.3 Million Populated County Skåne (Scania), Sweden. Molecules 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.D.; Cho, J.; Kim, I.S.; Vanderford, B.J.; Snyder, S.A. Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals and endocrine disruptors in South Korean surface, drinking, and waste waters. Water Res. 2007, 41, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-L.; Ying, G.-G.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.-F.; Yang, X.-B.; Yang, L.-H.; Li, X. Determination of phenolic endocrine disrupting chemicals and acidic pharmaceuticals in surface water of the Pearl Rivers in South China by gas chromatography-negative chemical ionization-mass spectrometry. Science of The Total Environment 2009, 407, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benotti, M.J.; Trenholm, R.A.; Vanderford, B.J.; Holady, J.C.; Stanford, B.D.; Snyder, S.A. Pharmaceuticals and endocrine disrupting compounds in U.S. drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, M.D.; Heath, E.; Petrovic, M.; Barceló, D. Trace-level determination of pharmaceutical residues by LC-MS/MS in natural and treated waters. A pilot-survey study. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 385, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Kumar, D. Ibuprofen as an emerging organic contaminant in environment, distribution and remediation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendz, D.; Paxéus, N.A.; Ginn, T.R.; Loge, F.J. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceutically active compounds in the environment, a case study: Höje River in Sweden. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 122, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, C.; van der Hoeven, N.; Clark, K.; Mihaich, E.; Woelz, J.; Hentges, S. Distributions of concentrations of bisphenol A in North American and European surface waters and sediments determined from 19 years of monitoring data. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.; Ryu, J.; Oh, J.; Choi, B.-G.; Snyder, S.A. Occurrence of endocrine disrupting compounds, pharmaceuticals, and personal care products in the Han River (Seoul, South Korea). Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wen, J.; He, B.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, J. Occurrence of caffeine in the freshwater environment: Implications for ecopharmacovigilance. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglioni, S.; Davoli, E.; Riva, F.; Palmiotto, M.; Camporini, P.; Manenti, A.; Zuccato, E. Mass balance of emerging contaminants in the water cycle of a highly urbanized and industrialized area of Italy. Water Res. 2018, 131, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, R.; Halden, R. Pharmaceuticals in the Built and Natural Water Environment of the United States. Water 2013, 5, 1346–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fram, M.S.; Belitz, K. Occurrence and concentrations of pharmaceutical compounds in groundwater used for public drinking-water supply in California. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 3409–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careghini, A.; Mastorgio, A.F.; Saponaro, S.; Sezenna, E. Bisphenol A, nonylphenols, benzophenones, and benzotriazoles in soils, groundwater, surface water, sediments, and food: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 5711–5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrull, J.; Colom, A.; Fabregas, J.; Borrull, F.; Pocurull, E. Presence, behaviour and removal of selected organic micropollutants through drinking water treatment. Chemosphere 2021, 276, 130023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröger, R.; Klöckner, P.; Ahrens, L.; Wiberg, K. Micropollutants in drinking water from source to tap - Method development and application of a multiresidue screening method. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 1404–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.-W.; Jo, B.-I.; Yoon, Y.; Zoh, K.-D. Occurrence and removal of selected micropollutants in a water treatment plant. Chemosphere 2014, 95, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayman, Z.; Işık, M. Pharmaceutically active compounds in water, Aksaray, Turkey. CLEAN Soil Air Water 2015, 43, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomat, Y.; Grischek, T. Occurrence, fate and potential risks of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in Elbe river water during water treatment in Dresden, Germany. Environmental Challenges 2024, 15, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simazaki, D.; Kubota, R.; Suzuki, T.; Akiba, M.; Nishimura, T.; Kunikane, S. Occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals at drinking water purification plants in Japan and implications for human health. Water Res. 2015, 76, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathishkumar, P.; Meena, R.A.A.; Palanisami, T.; Ashokkumar, V.; Palvannan, T.; Gu, F.L. Occurrence, interactive effects and ecological risk of diclofenac in environmental compartments and biota - a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulliet, E.; Cren-Olivé, C. Screening of pharmaceuticals and hormones at the regional scale, in surface and groundwaters intended to human consumption. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2929–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.; Carvalho, R.; António, D.C.; Comero, S.; Locoro, G.; Tavazzi, S.; Paracchini, B.; Ghiani, M.; Lettieri, T.; Blaha, L.; et al. EU-wide monitoring survey on emerging polar organic contaminants in wastewater treatment plant effluents. Water Res. 2013, 47, 6475–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, S.K.; Kim, H.W.; Oh, J.-E.; Park, H.-S. Occurrence and removal of antibiotics, hormones and several other pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment plants of the largest industrial city of Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4351–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben, W.; Zhu, B.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Qiang, Z. Occurrence, removal and risk of organic micropollutants in wastewater treatment plants across China: Comparison of wastewater treatment processes. Water Res. 2018, 130, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Tarigan, M.; Schmitz, O.; Schütz, S.; Gießelmann, S.; Czermak, P. Ceramic Membranes for the Efficient Separation of Organic Micropollutants from Aqueous Solutions Using the Example of Pharmaceutical Agents. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2023, 95, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, B.d.O.; Leite, L.d.S.; Daniel, L.A. Chlorine and peracetic acid in decentralized wastewater treatment: Disinfection, oxidation and odor control. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2021, 146, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albolafio, S.; Marín, A.; Allende, A.; García, F.; Simón-Andreu, P.J.; Soler, M.A.; Gil, M.I. Strategies for mitigating chlorinated disinfection byproducts in wastewater treatment plants. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, M.; Wirtz, A.; Hoffmann-Jacobsen, K.; Jaeger, M. Prior art for the development of a fourth purification stage in wastewater treatment plant for the elimination of anthropogenic micropollutants-a short-review. AIMS Environmental Science 2020, 7, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Ramísio, P.J.; Puga, H. A Comprehensive Review on Various Phases of Wastewater Technologies: Trends and Future Perspectives. Eng 2024, 5, 2633–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelic, A.; Gros, M.; Ginebreda, A.; Cespedes-Sánchez, R.; Ventura, F.; Petrovic, M.; Barcelo, D. Occurrence, partition and removal of pharmaceuticals in sewage water and sludge during wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel-Maeso, M.; Baena-Nogueras, R.M.; Corada-Fernández, C.; Lara-Martín, P.A. Occurrence, distribution and environmental risk of pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) in coastal and ocean waters from the Gulf of Cadiz (SW Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, R.; Yunesian, M.; Nasseri, S.; Gholami, M.; Jalilzadeh, E.; Shoeibi, S.; Mesdaghinia, A. Occurrence and fate of most prescribed antibiotics in different water environments of Tehran, Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619-620, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, L.; Omil, F.; Lema, J.M.; Carballa, M. What happens with organic micropollutants during UV disinfection in WWTPs? A global perspective from laboratory to full-scale. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 342, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostich, M.S.; Batt, A.L.; Lazorchak, J.M. Concentrations of prioritized pharmaceuticals in effluents from 50 large wastewater treatment plants in the US and implications for risk estimation. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 184, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C.E.; Marco-Urrea, E.; Caminal, G. Degradation of naproxen and carbamazepine in spiked sludge by slurry and solid-phase Trametes versicolor systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 2259–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodarte-Morales, A.I.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T.; Lema, J.M. Degradation of selected pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) by white-rot fungi. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 27, 1839–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Sánchez-Polo, M.; Ferro-García, M.Á.; Prados-Joya, G.; Ocampo-Pérez, R. Pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants and their removal from water. A review. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1268–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oulton, R.L.; Kohn, T.; Cwiertny, D.M. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in effluent matrices: A survey of transformation and removal during wastewater treatment and implications for wastewater management. J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 1956–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedeken, E.J.; Tahar, A.; McHugh, B.; Rowan, N.J. Monitoring, sources, receptors, and control measures for three European Union watch list substances of emerging concern in receiving waters - A 20year systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 1140–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rout, P.R.; Zhang, T.C.; Bhunia, P.; Surampalli, R.Y. Treatment technologies for emerging contaminants in wastewater treatment plants: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 141990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derco, J.; Žgajnar Gotvajn, A.; Guľašová, P.; Šoltýsová, N.; Kassai, A. Selected Micropollutant Removal from Municipal Wastewater. Processes 2024, 12, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestakova, M.; Sillanpää, M. Removal of dichloromethane from ground and wastewater: a review. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Qi, P.S.; Liu, Y.Z. A Review on Advanced Treatment of Pharmaceutical Wastewater. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 63, 12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadipelly, C.; Pérez-González, A.; Yadav, G.D.; Ortiz, I.; Ibáñez, R.; Rathod, V.K.; Marathe, K.V. Pharmaceutical Industry Wastewater: Review of the Technologies for Water Treatment and Reuse. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 11571–11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, M.E.; Chhetri, R.K.; Ooi, G.; Hansen, K.M.S.; Litty, K.; Christensson, M.; Kragelund, C.; Andersen, H.R.; Bester, K. Biodegradation of pharmaceuticals in hospital wastewater by staged Moving Bed Biofilm Reactors (MBBR). Water Res. 2015, 83, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M.; Grillini, V.; Mutavdžić Pavlović, D.; Verlicchi, P. Activated carbon coupled with advanced biological wastewater treatment: A review of the enhancement in micropollutant removal. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.A.; Varjani, S.; Taherzadeh, M.J. A Critical Review on the Ubiquitous Role of Filamentous Fungi in Pollution Mitigation. Curr Pollution Rep 2020, 6, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoon, B.L.; Ong, C.C.; Mohamed Saheed, M.S.; Show, P.-L.; Chang, J.-S.; Ling, T.C.; Lam, S.S.; Juan, J.C. Conventional and emerging technologies for removal of antibiotics from wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 122961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, I.; Rizzo, L.; McArdell, C.S.; Manaia, C.M.; Merlin, C.; Schwartz, T.; Dagot, C.; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for the release of antibiotics in the environment: a review. Water Res. 2013, 47, 957–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paździor, K.; Bilińska, L.; Ledakowicz, S. A review of the existing and emerging technologies in the combination of AOPs and biological processes in industrial textile wastewater treatment. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 376, 120597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W. Adsorptive removal of antibiotics from water and wastewater: Progress and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 532, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, F.; Al-Hindi, M.; Yahfoufi, R.; Ayoub, G.M.; Ahmad, M.N. The use of activated carbon for the removal of pharmaceuticals from aqueous solutions: a review. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2018, 17, 109–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benstoem, F.; Nahrstedt, A.; Boehler, M.; Knopp, G.; Montag, D.; Siegrist, H.; Pinnekamp, J. Performance of granular activated carbon to remove micropollutants from municipal wastewater-A meta-analysis of pilot- and large-scale studies. Chemosphere 2017, 185, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, S.A.; Adham, S.; Redding, A.M.; Cannon, F.S.; DeCarolis, J.; Oppenheimer, J.; Wert, E.C.; Yoon, Y. Role of membranes and activated carbon in the removal of endocrine disruptors and pharmaceuticals. Desalination 2007, 202, 156–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cabassud, C.; Guigui, C. Evaluation of membrane bioreactor on removal of pharmaceutical micropollutants: a review. Desalination and Water Treatment 2015, 55, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madondo, N.I.; Tetteh, E.K.; Rathilal, S.; Bakare, B.F. Synergistic Effect of Magnetite and Bioelectrochemical Systems on Anaerobic Digestion. Bioengineering (Basel) 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, P.; Suresh, S.; Balasubramain, B.; Gangwar, J.; Raj, A.S.; Aarathy, U.L.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Pappuswamy, M.; Sebastian, J.K. Biological treatment solutions using bioreactors for environmental contaminants from industrial waste water. J.Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appll. Sci. 2023, 20, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sravan, J.S.; Matsakas, L.; Sarkar, O. Advances in Biological Wastewater Treatment Processes: Focus on Low-Carbon Energy and Resource Recovery in Biorefinery Context. Bioengineering (Basel) 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Lei, D.; Zhao, X.; Hu, Y.; Yao, S.; Lin, K.; Wang, Z.; Cui, C. Antibiotic residue and toxicity assessment of wastewater during the pharmaceutical production processes. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miège, C.; Choubert, J.M.; Ribeiro, L.; Eusèbe, M.; Coquery, M. Removal efficiency of pharmaceuticals and personal care products with varying wastewater treatment processes and operating conditions - conception of a database and first results. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 57, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Yamashita, N.; Park, C.; Shimono, T.; Takeuchi, D.M.; Tanaka, H. Removal characteristics of pharmaceuticals and personal care products: Comparison between membrane bioreactor and various biological treatment processes. Chemosphere 2017, 179, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, S.; Lema, J.M.; Omil, F. Removal of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) under nitrifying and denitrifying conditions. Water Res. 2010, 44, 3214–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Yin, F.; Xu, G. Characterizing the removal routes of seven pharmaceuticals in the activated sludge process. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2437–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosal, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Perdigón-Melón, J.A.; Petre, A.; García-Calvo, E.; Gómez, M.J.; Agüera, A.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Occurrence of emerging pollutants in urban wastewater and their removal through biological treatment followed by ozonation. Water Res. 2010, 44, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, S.; Bagnati, R.; Fanelli, R.; Pomati, F.; Calamari, D.; Zuccato, E. Removal of pharmaceuticals in sewage treatment plants in Italy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, T.A. Occurrence of drugs in German sewage treatment plants and rivers. Water Res. 1998, 32, 3245–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Geissen, S.-U.; Gal, C. Carbamazepine and diclofenac: removal in wastewater treatment plants and occurrence in water bodies. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, W.-J.; Lee, J.-W.; Oh, J.-E. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment plants and rivers in Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clara, M.; Strenn, B.; Gans, O.; Martinez, E.; Kreuzinger, N.; Kroiss, H. Removal of selected pharmaceuticals, fragrances and endocrine disrupting compounds in a membrane bioreactor and conventional wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2005, 39, 4797–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwiener, C.; Frimmel, F.H. Short-term tests with a pilot sewage plant and biofilm reactors for the biological degradation of the pharmaceutical compounds clofibric acid, ibuprofen, and diclofenac. Science of The Total Environment 2003, 309, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Li, W.; Wei, Z.; Spinney, R.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Seo, Y.; Tang, C.-J.; Li, Q.; Xiao, R. Sorption and biodegradation of pharmaceuticals in aerobic activated sludge system: A combined experimental and theoretical mechanistic study. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 342, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yu, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lichtfouse, E.; Marmier, N. The Effect Review of Various Biological, Physical and Chemical Methods on the Removal of Antibiotics. Water 2022, 14, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, M.; Flowers, R.; McAvoy, D.; Dickenson, E. Biotransformation of trace organic compounds by activated sludge from a biological nutrient removal treatment system. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 216, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Chen, H.; Reinhard, M.; Mao, F.; Gin, K.Y.-H. Occurrence and removal of multiple classes of antibiotics and antimicrobial agents in biological wastewater treatment processes. Water Res. 2016, 104, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagle, J.; Porter, A.W.; Murdoch, R.W.; Rivera-Cancel, G.; Hay, A.G. Biodegradation of pharmaceutical and personal care products. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 67, 65–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso-Muniozguren, P.; Serna-Galvis, E.A.; Bussemaker, M.; Torres-Palma, R.A.; Lee, J. A review on pharmaceuticals removal from waters by single and combined biological, membrane filtration and ultrasound systems. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Ni, B.-J. Biotransformation of pharmaceuticals by ammonia oxidizing bacteria in wastewater treatment processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566-567, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nghiem, L.D.; Nguyen, L.N.; Phan, H.V.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Hai, F. Aerobic membrane bioreactors and micropollutant removal. Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier, 2020; pp 147–162, ISBN 9780128198094.

- Al-Asheh, S.; Bagheri, M.; Aidan, A. Membrane bioreactor for wastewater treatment: A review. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2021, 4, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaz, M.; Wickramasinghe, S.R.; Eswaranandam, S.; Zhang, W.; Jones, S.M.; Watts, M.J.; Qian, X. Investigation into Micropollutant Removal from Wastewaters by a Membrane Bioreactor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriaga, S.; Jonge, N. de; Nielsen, M.L.; Andersen, H.R.; Borregaard, V.; Jewel, K.; Ternes, T.A.; Nielsen, J.L. Evaluation of a membrane bioreactor system as post-treatment in waste water treatment for better removal of micropollutants. Water Res. 2016, 107, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mert, B.K.; Ozengin, N.; Dogan, E.C.; Aydıner, C. Efficient Removal Approach of Micropollutants in Wastewater Using Membrane Bioreactor. In Wastewater and Water Quality; Yonar, T., Ed.; InTech, 2018, ISBN 978-1-78923-620-0.

- Tadkaew, N.; Hai, F.I.; McDonald, J.A.; Khan, S.J.; Nghiem, L.D. Removal of trace organics by MBR treatment: the role of molecular properties. Water Res. 2011, 45, 2439–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blandin, G.; Gautier, C.; Sauchelli Toran, M.; Monclús, H.; Rodriguez-Roda, I.; Comas, J. Retrofitting membrane bioreactor (MBR) into osmotic membrane bioreactor (OMBR): A pilot scale study. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 339, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, H.; Nurgirisia, N.; Qiu, G.; Ting, Y.-P.; Wenten, I.G. Membrane distillation for wastewater treatment: Current trends, challenges and prospects of dense membrane distillation. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 46, 102615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-K.; Sheng, G.-P.; Shi, B.-J.; Li, W.-W.; Yu, H.-Q. A novel electrochemical membrane bioreactor as a potential net energy producer for sustainable wastewater treatment. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; van Tran, H.; Merenda, A.; Johir, M.A.H.; Phuntsho, S.; Shon, H. Removal of Organic Micro-Pollutants by Conventional Membrane Bioreactors and High-Retention Membrane Bioreactors. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Luo, W.; McDonald, J.; Khan, S.J.; Hai, F.I.; Price, W.E.; Nghiem, L.D. An anaerobic membrane bioreactor - membrane distillation hybrid system for energy recovery and water reuse: Removal performance of organic carbon, nutrients, and trace organic contaminants. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628-629, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, E.R.; Harmsen, D.; Beerendonk, E.F.; Qin, J.J.; Oo, H.; Korte, K.F. de; Kappelhof, J.W.M.N. The innovative osmotic membrane bioreactor (OMBR) for reuse of wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 63, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.N.; Hai, F.I.; Kang, J.; Price, W.E.; Nghiem, L.D. Removal of emerging trace organic contaminants by MBR-based hybrid treatment processes. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2013, 85, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Kumar, R.; Kishor, K.; Mlsna, T.; Pittman, C.U.; Mohan, D. Pharmaceuticals of Emerging Concern in Aquatic Systems: Chemistry, Occurrence, Effects, and Removal Methods. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 3510–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nageeb, M. Adsorption Technique for the Removal of Organic Pollutants from Water and Wastewater. In Organic Pollutants - Monitoring, Risk and Treatment; Rashed, M.N., Ed.; InTech, 2013, ISBN 978-953-51-0948-8.

- Dhangar, K.; Kumar, M. Tricks and tracks in removal of emerging contaminants from the wastewater through hybrid treatment systems: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 140320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mansouri, N.-E.; Yuan, Q.; Huang, F. Synthesis and characterization of kraft lignin-based epoxy resins. BioRes 2011, 6, 2492–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, H.; Koumaki, E.; Hoslett, J.; Malamis, S.; Katsou, E.; Barcelo, D.; Jouhara, H. Insights into current physical, chemical and hybrid technologies used for the treatment of wastewater contaminated with pharmaceuticals. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 361, 132079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Narvaez, O.M.; Peralta-Hernandez, J.M.; Goonetilleke, A.; Bandala, E.R. Treatment technologies for emerging contaminants in water: A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 323, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Castilla, C. Adsorption of organic molecules from aqueous solutions on carbon materials. Carbon 2004, 42, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, M.; Giampietro, G.; Mazyck, D.; Rodriguez, R. Activated Carbon for Pharmaceutical Removal at Point-of-Entry. Processes 2021, 9, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostvall, A.; Zhang, W.; Dürig, W.; Renman, G.; Wiberg, K.; Ahrens, L.; Gago-Ferrero, P. Removal of pharmaceuticals, perfluoroalkyl substances and other micropollutants from wastewater using lignite, Xylit, sand, granular activated carbon (GAC) and GAC+Polonite® in column tests - Role of physicochemical properties. Water Res. 2018, 137, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.D.G. de; Murniati; Budianta, W.; Rivera, K.K.P.; Arazo, R.O. Removal of sodium diclofenac from aqueous solution by adsorbents derived from cocoa pod husks. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2017, 5, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.; Ghaffari, E.; Aminzadeh, B. Removal of carbamazepine from municipal wastewater effluent using optimally synthesized magnetic activated carbon: Adsorption and sedimentation kinetic studies. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2016, 4, 3309–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlbay, Z.; Şahin, S.; Kerkez, Ö.; Bayazit, Ş.S. Isolation of naproxen from wastewater using carbon-based magnetic adsorbents. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 12, 3541–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Wang, J. Regeneration of sulfamethoxazole-saturated activated carbon using gamma irradiation. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2017, 130, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, Z.; Tunç, Ö. Application of biosorption for penicillin G removal: comparison with activated carbon. Process Biochemistry 2005, 40, 831–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, N.K.; Del Vecchio, P.; Marcilio, N.R.; Féris, L.A. Removal of atenolol by adsorption – Study of kinetics and equilibrium. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 154, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benstoem, F.; Pinnekamp, J. Characteristic numbers of granular activated carbon for the elimination of micropollutants from effluents of municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2017, 76, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, M.T.; Myers, E.; Schober, D.; Thege, C.; Korzin, A.; Schuhen, K. Adaptable Process Design as a Key for Sustainability Upgrades in Wastewater Treatment: Comparative Study on the Removal of Micropollutants by Advanced Oxidation and Granular Activated Carbon Processing at a German Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, P. Activated carbon from lignocellulosics precursors: A review of the synthesis methods, characterization techniques and applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 82, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margot, J.; Kienle, C.; Magnet, A.; Weil, M.; Rossi, L.; Alencastro, L.F. de; Abegglen, C.; Thonney, D.; Chèvre, N.; Schärer, M.; et al. Treatment of micropollutants in municipal wastewater: ozone or powdered activated carbon? Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 461-462, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailler, R.; Gasperi, J.; Coquet, Y.; Deshayes, S.; Zedek, S.; Cren-Olivé, C.; Cartiser, N.; Eudes, V.; Bressy, A.; Caupos, E.; et al. Study of a large scale powdered activated carbon pilot: Removals of a wide range of emerging and priority micropollutants from wastewater treatment plant effluents. Water Res. 2015, 72, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altmann, J.; Ruhl, A.S.; Zietzschmann, F.; Jekel, M. Direct comparison of ozonation and adsorption onto powdered activated carbon for micropollutant removal in advanced wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2014, 55, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issaoui, M.; Jellali, S.; Zorpas, A.A.; Dutournie, P. Membrane technology for sustainable water resources management: Challenges and future projections. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2022, 25, 100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharupaneedi, S.P.; Nataraj, S.K.; Nadagouda, M.; Reddy, K.R.; Shukla, S.S.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Membrane-based separation of potential emerging pollutants. Separation and Purification Technology 2019, 210, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, B.; Buscio, V.; Odabasi, S.U.; Buyukgungor, H. A study on behavior, interaction and rejection of Paracetamol, Diclofenac and Ibuprofen (PhACs) from wastewater by nanofiltration membranes. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2020, 18, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ali, J.; Jamil, S.U.U.; Zahra, N.; Tayaba, T.B.; Iqbal, M.J.; Waseem, H. Removal of micropollutants. Environmental Micropollutants; Elsevier, 2022; pp 443–461, ISBN 9780323905558.

- Sui, Q.; Huang, J.; Deng, S.; Yu, G.; Fan, Q. Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals, caffeine and DEET in wastewater treatment plants of Beijing, China. Water Res. 2010, 44, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellona, C.; Drewes, J.E.; Xu, P.; Amy, G. Factors affecting the rejection of organic solutes during NF/RO treatment--a literature review. Water Res. 2004, 38, 2795–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Nghiem, L.D.; Le-Clech, P.; Khan, S.J.; Drewes, J.E. Effects of membrane degradation on the removal of pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) by NF/RO filtration processes. Journal of Membrane Science 2009, 340, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmuganathan, S.; Johir, M.A.H.; Nguyen, T.V.; Kandasamy, J.; Vigneswaran, S. Experimental evaluation of microfiltration–granular activated carbon (MF–GAC)/nano filter hybrid system in high quality water reuse. Journal of Membrane Science 2015, 476, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licona, K.P.M.; Geaquinto, L.d.O.R.; Nicolini, J.V.; Figueiredo, N.G.; Chiapetta, S.C.; Habert, A.C.; Yokoyama, L. Assessing potential of nanofiltration and reverse osmosis for removal of toxic pharmaceuticals from water. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2018, 25, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albergamo, V.; Blankert, B.; Cornelissen, E.R.; Hofs, B.; Knibbe, W.-J.; van der Meer, W.; Voogt, P. de. Removal of polar organic micropollutants by pilot-scale reverse osmosis drinking water treatment. Water Res. 2019, 148, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comerton, A.M.; Andrews, R.C.; Bagley, D.M.; Yang, P. Membrane adsorption of endocrine disrupting compounds and pharmaceutically active compounds. Journal of Membrane Science 2007, 303, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, J.L.; Benitez, F.J.; Teva, F.; Leal, A.I. Retention of emerging micropollutants from UP water and a municipal secondary effluent by ultrafiltration and nanofiltration. Chemical Engineering Journal 2010, 163, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermann, D.; Pronk, W.; Boller, M.; Schäfer, A.I. The role of NOM fouling for the retention of estradiol and ibuprofen during ultrafiltration. Journal of Membrane Science 2009, 329, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolar, D.; Košutić, K. Removal of Pharmaceuticals by Ultrafiltration (UF), Nanofiltration (NF), and Reverse Osmosis (RO). Analysis, Removal, Effects and Risk of Pharmaceuticals in the Water Cycle - Occurrence and Transformation in the Environment; Elsevier, 2013; pp 319–344, ISBN 9780444626578.

- Yoon, Y.; Westerhoff, P.; Snyder, S.A.; Wert, E.C. Nanofiltration and ultrafiltration of endocrine disrupting compounds, pharmaceuticals and personal care products. Journal of Membrane Science 2006, 270, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangali Quintanilla, V.A. Rejection of Emerging Organic Contaminants by Nanofiltration and Reverse Osmosis Membranes; CRC Press, 2010, ISBN 9780429063107.

- Ghaffour, N.; Missimer, T.M.; Amy, G.L. Technical review and evaluation of the economics of water desalination: Current and future challenges for better water supply sustainability. Desalination 2013, 309, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellona, C.; Marts, M.; Drewes, J.E. The effect of organic membrane fouling on the properties and rejection characteristics of nanofiltration membranes. Separation and Purification Technology 2010, 74, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, A.A.; Tadkaew, N.; McDonald, J.A.; Khan, S.J.; Price, W.E.; Nghiem, L.D. Combining MBR and NF/RO membrane filtration for the removal of trace organics in indirect potable water reuse applications. Journal of Membrane Science 2010, 365, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaïs, A.; Mendret, J.; Gassara, S.; Petit, E.; Deratani, A.; Brosillon, S. Nanofiltration for wastewater reuse: Counteractive effects of fouling and matrice on the rejection of pharmaceutical active compounds. Separation and Purification Technology 2014, 133, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergili, I. Application of nanofiltration for the removal of carbamazepine, diclofenac and ibuprofen from drinking water sources. J. Environ. Manage. 2013, 127, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wavhal, D.S.; Fisher, E.R. Hydrophilic modification of polyethersulfone membranes by low temperature plasma-induced graft polymerization. Journal of Membrane Science 2002, 209, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Snyder, S.A. Attenuation of contaminants of emerging concerns by nanofiltration membrane: rejection mechanism and application in water reuse. Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Water and Wastewater; Elsevier, 2020; pp 177–206, ISBN 9780128135617.

- Fujioka, T.; Khan, S.J.; McDonald, J.A.; Nghiem, L.D. Nanofiltration of trace organic chemicals: A comparison between ceramic and polymeric membranes. Separation and Purification Technology 2014, 136, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-y.; Wang, X.-m.; Yang, H.-w.; Xie, Y.-f.F. Effects of organic fouling and cleaning on the retention of pharmaceutically active compounds by ceramic nanofiltration membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2018, 563, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva, J.; Roth, A.G.; Göbbert, C.; Niestroj-Pahl, R.; Dähne, L.; Wolfram, A.; Wiese, J. Hybrid Ceramic Membranes for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals from Aqueous Solutions. Membranes (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullayev, A.; Bekheet, M.F.; Hanaor, D.A.H.; Gurlo, A. Materials and Applications for Low-Cost Ceramic Membranes. Membranes (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testolin, R.C.; Mater, L.; Sanches-Simões, E.; Dal Conti-Lampert, A.; Corrêa, A.X.R.; Groth, M.L.; Oliveira-Carneiro, M.; Radetski, C.M. Comparison of the mineralization and biodegradation efficiency of the Fenton reaction and Ozone in the treatment of crude petroleum-contaminated water. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2020, 8, 104265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.M.d.; Jardim, W.F. Trends and strategies of ozone application in environmental problems. Quím. Nova 2006, 29, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalova, L.; Siegrist, H.; Gunten, U. von; Eugster, J.; Hagenbuch, M.; Wittmer, A.; Moser, R.; McArdell, C.S. Elimination of micropollutants during post-treatment of hospital wastewater with powdered activated carbon, ozone, and UV. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7899–7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Gerrity, D.; Lee, M.; Bogeat, A.E.; Salhi, E.; Gamage, S.; Trenholm, R.A.; Wert, E.C.; Snyder, S.A.; Gunten, U. von. Prediction of micropollutant elimination during ozonation of municipal wastewater effluents: use of kinetic and water specific information. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5872–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgin, M.; Beck, B.; Boehler, M.; Borowska, E.; Fleiner, J.; Salhi, E.; Teichler, R.; Gunten, U. von; Siegrist, H.; McArdell, C.S. Evaluation of a full-scale wastewater treatment plant upgraded with ozonation and biological post-treatments: Abatement of micropollutants, formation of transformation products and oxidation by-products. Water Res. 2018, 129, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, H.; Loganathan, K.; Saththasivam, J.; McKay, G. Ozone and ozone/hydrogen peroxide treatment to remove gemfibrozil and ibuprofen from treated sewage effluent: Factors influencing bromate formation. Emerging Contaminants 2020, 6, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, S. de; González-Rodríguez, J.; Conde, J.J.; Moreira, M.T. Benchmarking tertiary water treatments for the removal of micropollutants and pathogens based on operational and sustainability criteria. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 46, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östman, M.; Björlenius, B.; Fick, J.; Tysklind, M. Effect of full-scale ozonation and pilot-scale granular activated carbon on the removal of biocides, antimycotics and antibiotics in a sewage treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polińska, W.; Kotowska, U.; Kiejza, D.; Karpińska, J. Insights into the Use of Phytoremediation Processes for the Removal of Organic Micropollutants from Water and Wastewater; A Review. Water 2021, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Liao, G.-Y. Degradation of antibiotic tetracycline by ultrafine-bubble ozonation process. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2020, 37, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Majumder, A.; Saidulu, D.; Bhattacharya, A.; Bhatnagar, A.; Gupta, A.K. Oxidative treatment of micropollutants present in wastewater: A special emphasis on transformation products, their toxicity, detection, and field-scale investigations. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 354, 120339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutterbeck, C.A.; Wilde, M.L.; Baginska, E.; Leder, C.; Machado, Ê.L.; Kümmerer, K. Degradation of 5-FU by means of advanced (photo)oxidation processes: UV/H2O2, UV/Fe2+/H2O2 and UV/TiO2--Comparison of transformation products, ready biodegradability and toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 527-528, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-García, N.; Suárez, S.; Sánchez, B.; Coronado, J.M.; Malato, S.; Maldonado, M.I. Photocatalytic degradation of emerging contaminants in municipal wastewater treatment plant effluents using immobilized TiO2 in a solar pilot plant. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2011, 103, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Sutton, N.B.; Rijnaarts, H.H.H.; Langenhoff, A.A.M. Degradation of pharmaceuticals in wastewater using immobilized TiO 2 photocatalysis under simulated solar irradiation. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2016, 182, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, S.; Schnabel, T.; Dutschke, M.; Londong, J. Floating immobilized TiO2 catalyst for the solar photocatalytic treatment of micro-pollutants within the secondary effluent of wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cruz, N. de; Giménez, J.; Esplugas, S.; Grandjean, D.; Alencastro, L.F. de; Pulgarín, C. Degradation of 32 emergent contaminants by UV and neutral photo-fenton in domestic wastewater effluent previously treated by activated sludge. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Qu, S.; Li, R.; Huo, Z.-Y.; Gao, Y.; Luo, Y. Degradation of antibiotics by electrochemical advanced oxidation processes (EAOPs): Performance, mechanisms, and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, C.-H.; Leung, K.S.-Y. Removing acesulfame with the peroxone process: Transformation products, pathways and toxicity. Chemosphere 2019, 221, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlesi Jara, C.; Fino, D.; Specchia, V.; Saracco, G.; Spinelli, P. Electrochemical removal of antibiotics from wastewaters. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2007, 70, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahrouei, A.E.; Vakili, S.; Zandifar, A.; Pourebrahimi, S. From wastewater to clean water: Recent advances on the removal of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and sulfamethoxazole antibiotics from water through adsorption and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 119029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, P.; Kandasamy, J.; Ratnaweera, H.; Vigneswaran, S. Submerged membrane/adsorption hybrid process in water reclamation and concentrate management-a mini review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 42738–42752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baresel, C.; Harding, M.; Fång, J. Ultrafiltration/Granulated Active Carbon-Biofilter: Efficient Removal of a Broad Range of Micropollutants. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoquart, C.; Servais, P.; Bérubé, P.R.; Barbeau, B. Hybrid Membrane Processes using activated carbon treatment for drinking water: A review. Journal of Membrane Science 2012, 411-412, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmuganathan, S.; Loganathan, P.; Kazner, C.; Johir, M.A.H.; Vigneswaran, S. Submerged membrane filtration adsorption hybrid system for the removal of organic micropollutants from a water reclamation plant reverse osmosis concentrate. Desalination 2017, 401, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, T. Research on the current situation of ultrafiltration combined process in treatment of micro-polluted surface water. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 194, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneswaran, S.; Chaudhary, D.S.; Ngo, H.H.; Shim, W.G.; Moon, H. Application of a PAC-Membrane Hybrid System for Removal of Organics from Secondary Sewage Effluent: Experiments and Modelling. Separation Science and Technology 2003, 38, 2183–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Nakayama, A.; Matsui, Y.; Matsushita, T.; Shirasaki, N. Desorption of micropollutant from superfine and normal powdered activated carbon in submerged-membrane system due to influent concentration change in the presence of natural organic matter: Experiments and two-component branched-pore kinetic model. Water Res. 2022, 208, 117872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, S.; Loganathan, P.; Khan, S.J.; McDonald, J.A.; Kandasamy, J.; Vigneswaran, S. Enhanced nanofiltration rejection of inorganic and organic compounds from a wastewater-reclamation plant’s micro-filtered water using adsorption pre-treatment. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 260, 118207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbardella, L.; Comas, J.; Fenu, A.; Rodriguez-Roda, I.; Weemaes, M. Advanced biological activated carbon filter for removing pharmaceutically active compounds from treated wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Peng, S. The change of NOM in a submerged UF membrane with three different pretreatment processes compared to an individual UF membrane. Desalination 2015, 360, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, Y.; Yuasa, A.; Ariga, K. Removal of a synthetic organic chemical by PAC-UF systems--I: Theory and modeling. Water Res. 2001, 35, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeyink, V.L.; Campos, C.; Mariñas, B.J. Design and performance of powdered activated carbon/ultrafiltration systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2000, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo Alonso, V.; Kaiser, T.; Babist, R.; Fundneider, T.; Lackner, S. A multi-component model for granular activated carbon filters combining biofilm and adsorption kinetics. Water Res. 2021, 197, 117079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolar, D.; Gros, M.; Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Moreno, J.; Comas, J.; Rodriguez-Roda, I.; Barceló, D. Removal of emerging contaminants from municipal wastewater with an integrated membrane system, MBR-RO. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 239-240, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangali-Quintanilla, V.; Sadmani, A.; McConville, M.; Kennedy, M.; Amy, G. A QSAR model for predicting rejection of emerging contaminants (pharmaceuticals, endocrine disruptors) by nanofiltration membranes. Water Res. 2010, 44, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Guimarães, A.; Torner-Morales, F.J.; Durán-Álvarez, J.C.; Jiménez-Cisneros, B.E. Removal and fate of emerging contaminants combining biological, flocculation and membrane treatments. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 67, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asheghmoalla, M.; Mehrvar, M. Integrated and Hybrid Processes for the Treatment of Actual Wastewaters Containing Micropollutants: A Review on Recent Advances. Processes 2024, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Key Subcategories | Primary Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals | NSAIDs, lipid regulators, antibiotics, β-blockers, contrast media, and anticonvulsants | Domestic sewage (from human excretion), Effluents from hospitals, Waste from animal farming and aquaculture |

|

| Personal care products | Fragrances, disinfectants, UV filters, and insect repellents | Household sewage (from bathing, shaving, and spraying) | |

| Endocrine disrupting chemicals | Estrogens | Human excreta-derived domestic wastewater Livestock production and aquaculture activities |

|

| Pesticides | Insecticides, herbicides and fungicides | Domestic wastewater originating from inadequate cleaning practices and garden runoff | |

| Industrial chemicals | Plasticizers, fire retardants | Domestic wastewater generated through the leaching of materials | |

| Microplastics | Microfibers, plastic pellets, synthetic fibers | Domestic wastewater resulting from urban runoff |

| Pharmaceutical Categories | Pharmaceutical pollutants | Chemical formulas | Mass (gmol-1) |

pKa | Log Kow | Ionization State at pH 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics and Anti-inflammatories | Aspirin | C9H8O4 | 280 | 3.5 | 1.2 | Negative |

| Diclofenac | C14H11Cl2NO2 | 296.2 | 4.91 | 4.51 | Negative | |

| Ibuprofen | C13H18O2 | 206.3 | 4.15 | 4.51 | Negative | |

| Paracetamol | C8H9NO2 | 151.2 | 9.38 | 0.46 | Neutral | |

| Naproxen | C14H14O3 | 230.3 | 4.15 | 3.18 | Negative | |

| Antibiotics | Sulfamethoxazole | C10H11N3O3S | 253.279 | 5.6- 5.7 | 0.89 | Negative |

| Erythromycin | C37H67NO13 | 733.93 | 8.88 | 2-48 | Neutral | |

| Trimethoprim | C14H18N4O3 | 290.32 | 7.12 | 0.73 | Neutral | |

| Anticonvulsants | primidone | C12H14N2O2 | 218 | -1;12.2 | 0.91 | Negative |

| Carbamazepine | C15H12N2O | 236.27 | 13 | 2.45 | Neutral | |

| ß-blockers | Propranolol | C16H21NO2 | 259.34 | 9.6 | 3.48 | Neutral |

| Metoprolol | C15H25NO3 | 276.37 | 9.49 | 1.88 | Positive | |

| Contrast media | Iopromide | C18H24I3N3O8 | 790.0 | 2;13 | -2.10 | Neutral |

| Iopamidol | C17H22I3N3O8 | 777.1 | 10.7 | -2.42 | Neutral | |

| Iohexol | C19H26I3N3O9 | 821.1 | 11.7 | -3.05 | Neutral | |

| Blood lipid regulators | Clofibric acid | C10H11ClO3 | 214.65 | 3.35 | 2.57 | Negative |

| Gemfibrozil | C15H22O3 | 250.34 | 4.45 | 4.77 | Negative | |

| Bezafibrate | C19H20ClNO4 | 361.82 | 3.44 | 4.25 | Negative | |

| Pravastatin | C23H36O7 | 24.53 | 4.2 | 3.1 | Negative |

| Water Type | Micropollutants | Countries | Concentration [ng/L] | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Water |

Caffeine Diclofenac Carbamazepine Ibuprofen Naproxen Bisphenol A |

Germany Denmark Korea China UK Sweden Korea China USA Korea Germany Korea China Germany Sweden Korea China Europe USA Korea |

65 – 6,798 65 - 382 268.7 865 20 – 91 680 8,8 – 127 < 147 6.8 5 - 36 60 – 152 11 - 38 1417000 70 90 – 250 20 – 483 < 118 10 81 4.5 - 61 |

[105] [106] [107] [108] [109,110] [110] [111] [112] [113] [107] [114] [107] [115] [114] [116] [107] [115] [117] [117] [118] |

| Ground Water |

Caffeine Ibuprofen Carbamazepine Atrazine Bisphenol A |

USA Germany China Italy USA Europe Europe USA Europe Europe USA |

290 102 42.5 84 - 683 3,110 3 - 395 12 - 390 42 8 – 253 79 – 2299 4.1 – 1990 |

[119] [119] [119] [120] [121] [115] [105] [122] [105] [105] [123] |

| Drinking Water | Caffeine Diclofenac Carbamazepine Ibuprofen Naproxen Metoprolol Bisphenol A |

Spain Sweden USA Korea Turkey Germany Japan Spain Sweden France Japan France Japan France Germany France France Germany |

9.10 5.50 52.3 34.3 - 95.5 3390 611 16 25 8 56 25 41,6 6 14 244 6 1 72 |

[124] [125] [119] [126] [127,128] [128] [129] [130] [125] [131] [129] [131] [129] [131] [128] [131] [131] [128] |

| WWTP Effluent | Caffeine Diclofenac Carbamazepine Ibuprofen Atrazine Bisphenol A |

Europe Korea Europe Korea Europe Korea China Europe Korea Europe Europe China |

3002 60 174 49 4609 74 55 2129 75 36.6 200 623.6 |

[132] [133] [132] [133] [132] [133] [132] [132] [133] [132] [134] [134] |

| Treatment Processes | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional biological treatment |

- Reduced initial investment - Versatile and straightforward technology - Environmentally sustainable |

- Inefficient removal of low-biodegradable pharmaceutical contaminants - Generation of toxic metabolites - Inability to target specific pharmaceutical contaminants - High sludge production |

[152,153,154] |

| Advanced biological treatment |

- Focused removal of contaminants - High adaptability to diverse wastewater characteristics - Space-efficient design - Improved removal of pharmaceutical contaminants - Effective operation at elevated suspended solids concentrations |

- High energy and initial investment costs - Membrane fouling issues - Challenges in degrading persistent PCs - Necessitate effective strategies for managing microbial activity |

[155,156,157] |