Results and Discussion

In his obituary on the death of the eminent American geographer and geomorphologist William Morris Davis (1850-1934), Isaiah Bowman (1934) wrote:

P.180. “To Professor Davis is due the organization of the Association of American Geographers in 1904, at a meeting in his native Philadelphia. He immediately urged that the Association "publish or perish." "If it's worth doing it's worth printing," was his advice to students. He believed that one should be schooled to criticism early in his career as an offset to egotism, provincialism, lazy acceptance of one's self in a routine job”. He hated the "stuffed shirt" of officialdom, whether in government or in scientific institutions”.

The full text of the issue of The Geographical Review in which Isaiah Bowman's obituary was published was found by us by searching The General Index for the term "publish or perish". It was digitised by the Internet Archive on 2021-09-27. This extract, without the first sentence, was found by searching Google Books for the term 'publish or perish', which makes it impossible to identify the author of the thoughts it contains. This issue of The Geographical Review, held by the University of California Library, was digitised by Google Books on 2019-04-30. Much earlier, the obituary in question was digitised by the JSTOR digital library (

https://www.jstor.org/stable/208785), but only the first page of this obituary is publicly available (Preview).

As we noted earlier, the first to track down this obituary was G. Cabanac (2018), but he does not quote the above extract.

We can't distrust the words of Isaiah Bowman (1878-1950) who, like W.M. Davis, was a well-known geographer and knew him well. Note that he became the first director of the American Geographical Society in 1915. That the phrase "publish or perish" belonged to W.M. Davis was written in the same years by Professor Robert Speight (1867-1949).

R. Speight (1935) published an inaugural address given at the founding of the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1934. On page 402 of this address is the following extract:

P.402. “The main activities have been in the direction of encouraging scientific work by providing means for publication, and this is after all, a most important function of such a body as the Institute. The opportunity to publish the results of work is a most real form of encouragement. One of the aphorisms of Professor W.M. Davis, “Publish or Perish”. Davis applied the remark to individuals, for he went on to say, " If it is worth doing, it is worth printing!”. No opportunity to print is afforded, then the well of inspiration dries up. It may also be applied to societies, for this generally dis considered function of such a society as this as really the main stimulus to a vigorous existence”.

Here we are talking about the publishing activities of the New Zealand Institute, founded in 1867 and renamed the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1934.

Both I. Bowman (1934) and R. Speight (1935) refer to the aphorisms of Professor W. M. Davis "publish or perish". They are both paying tribute to this man who died in February 1934.

As we can see from the two extracts above, W. M. Davis saw his aphorism in a positive sense, believing that new knowledge must be published or it will perish. Note that I. Bowman (1938), in his later article, was convinced of the need to follow this principle:

P.465. “We have too often let records of experience take the place of experience. ‘‘Read or barbarise,’’ says a humanist, and a scientist seconds the motion by adding ‘‘publish or perish.’’ These are natural reactions in view of the importance of records in expanding human powers. Armies, governments, institutions are now generally administered on paper. Civilization is to a surprising degree based on records”.

The above works by R. Speight (1935) and I. Bowman (1938) were found by searching The General Index for the term "publish or perish". Note that the snippet from the Bulletin of the Association of American Colleges (1938) found in I.A. Moosa (2018) corresponds to the work of I. Bowman (1938).

The above works by R. Speight (1935) and I. Bowman (1938) were found by searching The General Index for the term "publish or perish". Note that the excerpt from the Bulletin of the Association of American Colleges (1938) found in I.A. Moosa (2018) corresponds to the work of I. Bowman (1938).

As we know from Wikipedia and from I.A. Moosa (2018) in a non-academic context, the phrase appears in Harrold Jefferson Coolidge and Robert Howard Lord (1932), where it is stated that "the Council must publish or perish" (p. 308). This reference came to light when this book was digitised by Google Books at the University of Michigan Library on 13 June 2006. However, the 6-word excerpt above does not make it clear in what context the phrase "publish or perish" is used and which Council is referred to. Our more detailed search for this book on the Internet revealed the full text of this book on the HathiTrust website. In "Chapter XVII. The Council on Foreign Relations and Foreign Affairs, 1922-1928" on page 308 the following excerpt is given:

P.308.“The name of the Council on Foreign Relations was adopted, and it was decided to sponsor a magazine, for as one of the Directors remarked, The Council must publish or perish. The men in control were a strong lot, as the Directorate for 1922* shows, and besides the governing body, most of whom took an active interest in the management…

*John W. Davis, President;…, Dr. Isaiah Bowman,…”

And, as we already know, the geographer Isaiah Bowman (1934) wrote that at the founding meeting of the Association of American Geographers in 1904, William Morris Davis urged the Association to “publish or perish”. Isaiah Bowman's participation on the Directorate of the Council on Foreign Relations and Foreign Affairs in 1922 suggests that by the 1920s the slogan "publish or perish" was well known in the academic environment of Anglophone countries.

Later, Joseph Kraft (1958), writing about the activities of the Council on Foreign Relations, noted that the Council had pursued a "publish or perish" policy from its inception. He also noted that the Council had started the quarterly journal Foreign Affairs in 1922.

In a positive sense, the term "publish or perish" was used by Logan Wilson (1941) of the University of Maryland. On page 353 of his article you can read:

P. 353. “It is essential that results be brought to light in the form of publication, for in the academic scheme of things, results unpublished are little better than those never achieved. The prevailing pragmatism enforced upon the academic group is that one must write something and get it into print. Situational imperatives dictate a "publish or perish" credo within the ranks, and numerous media furnish outlets, so that any new formulation or discovery may without further ado be added to the total sum of knowledge”.

This article is not in the public domain. Part of this excerpt "The prevailing pragmatism... within the rank..." by Logan Wilson (1942) was discovered at the request of Eugene Garfield (1996) by Fred Shapiro, librarian at Yale University Law School and editor of the Oxford Dictionary of American Legal Quotations. To review this article, we ordered it from Hein Online.

Alan C. Lloyd's (1947) interpretation of the term "publish or perish" is ambiguous. At the very beginning of his article, he wrote:

P.21. “Have you ever heard that neat little slogan, “Publish or perish”? It has a double meaning. To college teachers it is a cliche that describes an irksome policy of their institutions: before winning a promotion in professorial rank candidates for chairs must demonstrate their ability to contribute to the professional thought of their fields. This means speaking or writing; so a large proportion of the ideas we hear at conventions and read in magazines come from college folks. To editors, however, the “publish or perish” admonition has a different meaning: that ideas which are not published soon perish”.

From this excerpt we can see that for the career development of teachers it is necessary to publish more, to the detriment of the quality of education of students; at the same time it is important for editors to have more publications, because unpublished knowledge dies, as Professor W. M. Davis said at the beginning of the 20th century. The first page of the above article is available in Open Access on Taylor & Francis Online.

Let us ask ourselves: when did W.M. Davis's aphorism acquire a negative connotation? We cited via Google Books in 2015 (Moskovkin, 2015) an extensive excerpt from the journal Sociology and Social Research (1927. Vol. 12. P. 325), which was digitised by Google Books specialists at the University of California Library on 8 January 2007. However, the author and title of the article could not be identified at that time.

The full bibliographic description of this article, as we noted earlier, could be ascertained by G. Cabanac (2018), who found the above reference from Google Books in Wikipedia (published there on 18 August 2016). He then requested a copy from a university library in Strasbourg and updated the incomplete Wikipedia reference (Case, 1927-1928). However, he provided a very small 2-line snippet that does not allow us to understand the context in which the phrase "publish or perish" is used.

To understand this context, we provide a larger excerpt from the above article by Clarence Marsh Case (1874-1946), then at the University of Southern California.

P. 325. “If it be true that, for the time being at least, the quality of American sociological writing is in inverse ratio to its quantity, the reason is to be sought, among other things, in the fact, first, that the system of promotion used in our universities amounts to the warning, “Publish or perish!” In the second place, publication in general is more easy than formerly; and in the third place, there is an insistent demand for sociological text-books on the part of the great publishing houses, many of whom are busily creating what they call “Social Science Series,” in which they and their respective corps of authors are industriously duplicating one another’s output”.

We found the full text of this article by searching The General Index for the term "publish or perish". It shows that the article was published in the March-April 1928 issue of the journal, so there is no question of a double year (1927-1928) as C.M. Case pointed out.

A sociologist from Southern Illinois University, Edward C. McDonagh (1943), wrote about the situation in the academic environment of leading American sociologists 15 years after the publication of C.M. Case's work in 1928. He reviewed the publication records of 21 past Presidents of the American Sociological Society and concluded that:

P. 95. “Most of us can point to several contemporary sociologists who are great teachers of the discipline but who have not found the energy, time, nor inclination for active writing programs. In our field the popular dictum, “publish or perish”, apparently still holds true. The most prolific writer among the group studied has written of 27 books and the least prolific, 2”

Comparing these two works, we see that while S.M. Case writes about how the slogan "publish or perish" negatively affects the quality of scientific publications, E.C. McDonagh draws attention to the negative impact of this slogan, which has already become a dictate, on the quality of education.

The full text of the issue of the American Sociological Review in which E.C. McDonagh's article was published has been digitised and is available at the Internet Archive on 2021-02-18.

Whether S.M. Case's article (1928) is the earliest to mention the slogan "publish or perish" remains an open question.

The origins of the general negative attitude towards this slogan should be sought in the activities of James Bryant Conant (1893-1978) as President of Harvard University (1933-1953). As we have noted, there is ample evidence in the literature that the Harvard slogan "publish or perish" came from J.B. Conant and was not just a slogan but a dictum.

If for W.M. Davis, as we have already learned, the slogan "publish or perish" was a wish for all scientists to publish their works, because new knowledge that is not published simply dies, then for J.B. Conant it was a dictum that was elevated to the rank of university policy. In the Wikipedia article on him, we read that "his longest and most bitter battle was over tenure reform, shifting to an "up or out" policy, under which scholars who were not promoted were terminated”. This extract is with reference to Pauld Bartlett (1983) who also wrote:

P. 98. “At Harvard, Conant is remembered for a number of important innovations. In the pursuit of excellence in selection of the faculty, he insisted on the sharp definition of tenure so that an assistant professor who was not promoted at the end of his stated term was automatically terminated as a member of the faculty. The adoption of this practice by other universities has been slow but steady”.

We do not know whether J.B. Conant knew the slogan "publish or perish" from W.M. Davis or from his followers, but we must assume that he had an inner conviction to follow this slogan, since he was a very prolific author himself. According to Martin D. Saltzman (2003), Conant and his co-authors published 36 papers from 1919-1925 and 55 papers from 1928-1933.

The most notorious case of faculty dismissal at Harvard University under Conant's presidency was described by Irwin Ross (1940). It was the story of the dismissal from Harvard University of economics instructors J. Raymond Walsh and Alan R. Sweezy, which began in April 1937. A few industrious souls formed a protest committee and began publishing reports in Boston newspapers. As Irwin Ross notes, the motive for these publications was that academic freedom had been violated and that the two economists had been dismissed because of their political Marxist views. However, it was officially announced that "teaching capacity and scholarly ability" were the only reasons for their dismissal, despite the testimony of professors and students to the contrary. Irwin Ross went on to write:

P.545. “Perhaps, the student committee hinted, Walsh and Sweezy were being victimized by Harvard’s prime sacred cow: the imperative “Publish or Perish.” These men preferred devoting the bulk of their energies to their students rather than to the methodical production of scholarly treatises”.

But more importantly, the introduction of the "publish or perish" dictum may have been linked to the Great Depression, when there was a huge surplus of graduate students and young faculty seeking assistant professorships. As Irwin Ross writes, during the Great Depression "countless young people saw academic life as a safe and pleasant refuge from the economic storm".

But in the end, President Conant was blamed for the infamous event, and it had lasting consequences.

Note that editor and writer Irwin Ross (1919-2005) received a Bachelor of Art degree from Harvard in 1940, the year he published his article in the prestigious Harper's magazine, which had been published since 1850. We found this article by searching The General Index for the term "publish or perish", and the snippet we found in 2015 (Harper's Magazine. 1940. Vol. 181. p. 545) corresponds to this article.

Below we provide a few more references to show Conant's important role in introducing the "publish or perish" dictum at Harvard, from where it spread to other universities in the United States and Britain.

Searching for the term "publish or perish" in Google Books, we found a snippet from The Fortnightly Review (1939, Vol. 146, Vol. 152, p. 211) in 2015, which is not clear from the volume number:

P. 211. “… this principle survives, there is a danger that professors will become mere back-workers. Let it not thought that the old gentlemanly institutions are free from this tendency. President Conant of Harvard, who is himself a highly cultured person, has introduced the principle of “publish or perish " with a vengeance into America's oldest university. Indeed, English universities, even Oxford and Cambridge, which have been most scornful towards these German - American methods, are adopting them rather ...”

Currently researching the archives of The Fortnightly Review on the HathiTrust website we have found that this journal began publication in 1865 and that volume 152 corresponds to 1939. The article itself is not Open Access, nor is the content of this volume of the journal, and we are unable to identify the title and author of the article. But what strikes us in the excerpt itself is that following the principle discussed above runs the risk of turning professors into mere back-workers.

We found another reference to Conant when we searched for the term "publish or perish" using The General Index. This was a book by Charles A. Wagner (1950) entitled "Harvard: Four Centuries and Freedoms”. On page 274 of this book there is an ironic expression:

P. 274. “He has written twenty-two large books to date, and if the alleged Conant admonition to the faculty “publish or perish” has any meaning, he should be around Littauer for a few centuries at least”.

They are Seymour Edwin Harris (1897-1974), an American academic and professor of economics at Harvard University who served as John F. Kennedy's economic adviser, and Lucius Nathan Littauer (1859-1944), an American politician, businessman and college football coach. In 1936, Littauer's donation of $2 million helped establish Harvard's Graduate School of Public Administration, later renamed the Harvard Kennedy School. We have taken this information from Wikipedia.

In the above extract from The Fortnightly Review (1939), the reference to German - American methods in the context of the "publish or perish" phenomenon is very interesting. This suggests that traces of this phenomenon should also be sought in Europe. In this regard, we found that when translating this expression into German, "veröffentlichen oder untergehen", there are no publications in German-language literature using this expression. This was confirmed by searching for this German-language term in Google Books or NGram Viewer. We found, however, that the German-language literature exclusively uses the English term "publish or perish" when dealing with the above phenomenon.

Testing this term in the German-language corpus of books on Google Books and the period 1920-1950, we found the fifth volume of books by Swiss historian Werner Kaegi (1901 - 1979): "Jacob Burckhardt: 5. Das neuere Europa und das Erlebnis der Gegenwart" (Kaegi, 1973). Note that Google Books gives 1947 as the year of publication of the first volume of this book.

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (1818 - 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields.

Google Books gives the following snippet on page 269 of this volume:

P.269. “Burckhardt war zuweilen nicht sehr weit davon entfernt, des Schlagwort fur den Wissenschaftsbetrieb des 20. Jahrhunderts zu ahnem: “Publish or perish!” Burckhardt leitet dies alles nicht aus « Entwicklungen » und « wirt- schaftlichen Notwendigkeiten » her, sondern aus der « Wut des schnellen Reichwerdens » . Er, der durch seine tägliche Arbeit zu beweisen…”,

which translates into English as:

P. 269. “At times, Burckhardt was not very far off the mark when he surmised the catchphrase for the academic world of the 20th century: "Publish or perish!" Burckhardt does not derive all this from "developments" and "economic necessities", but from the "rage of getting rich quick". He, who has to prove through his daily work…”.

Since Jacob Burckhardt died in 1897, the literary reference to the slogan "publish or perish" should be dated from the early 20th century (W.M. Davis' mention of this slogan in 1904) to at least the late 19th century. It would be interesting to initiate historical and archival research, using Jacob Burckhardt's memoirs and the works of his biographers, in order to find more detailed information on the description of this phenomenon.

Since book printing and the first scientific journals originated in Europe, and these events are key to the progress of open research publishing (Tennant et al., 2016), the origins of the slogan "publish or perish" seem to be found there. The fact that there is no Latin phrase "publish aut perire" on the Internet does not mean that it did not exist, as the percentage of digitised manuscripts and books in Latin is still very small, and far from all of them are being studied.

For example, David Bamman and David Smith (2012) estimate that the Internet Archive has placed 27,014 works catalogued as Latin in Open Access. And more generally, at the 2010 level, out of 130 million unique books, Google Books has placed about 10 million books in Open Access. So there is a wide range of possibilities for the ultimate resolution of the question posed by Eugene Garfield, as well as many other related questions.

We believe that in the table of major historical milestones in the progress of open research publishing (Tennant et al., 2016), the approximate date of origin of the "publish or perish" phenomenon (late 19th - early 20th century) should occupy a worthy place.

That the meaning of this phenomenon is close to the idea of Open Access can be seen in the words of Robert K. Merton (1942, p.122):

“The institutional conception of science as part of the public domain is linked with the imperative for communication of findings. Secrecy is the antithesis of this norm;full an open communication its enactment. The pressure for diffusion of results is reenforced by the institutional goal of ‘advancing the boundaries of knowledge’ and by the incentive of recognition which is, of course, contingent upon publication.”

This phrase is quoted by G. Cabanac (2018) in the context of the above table by J.P. Tennant et al. (2016), who believes that the origin of the Open Access concept should be found in this very phrase. Moreover, we believe that R. K. Merton's statement is fully consistent with both the Open Access concept and the phenomenon of "publish or perish" in its original sense.

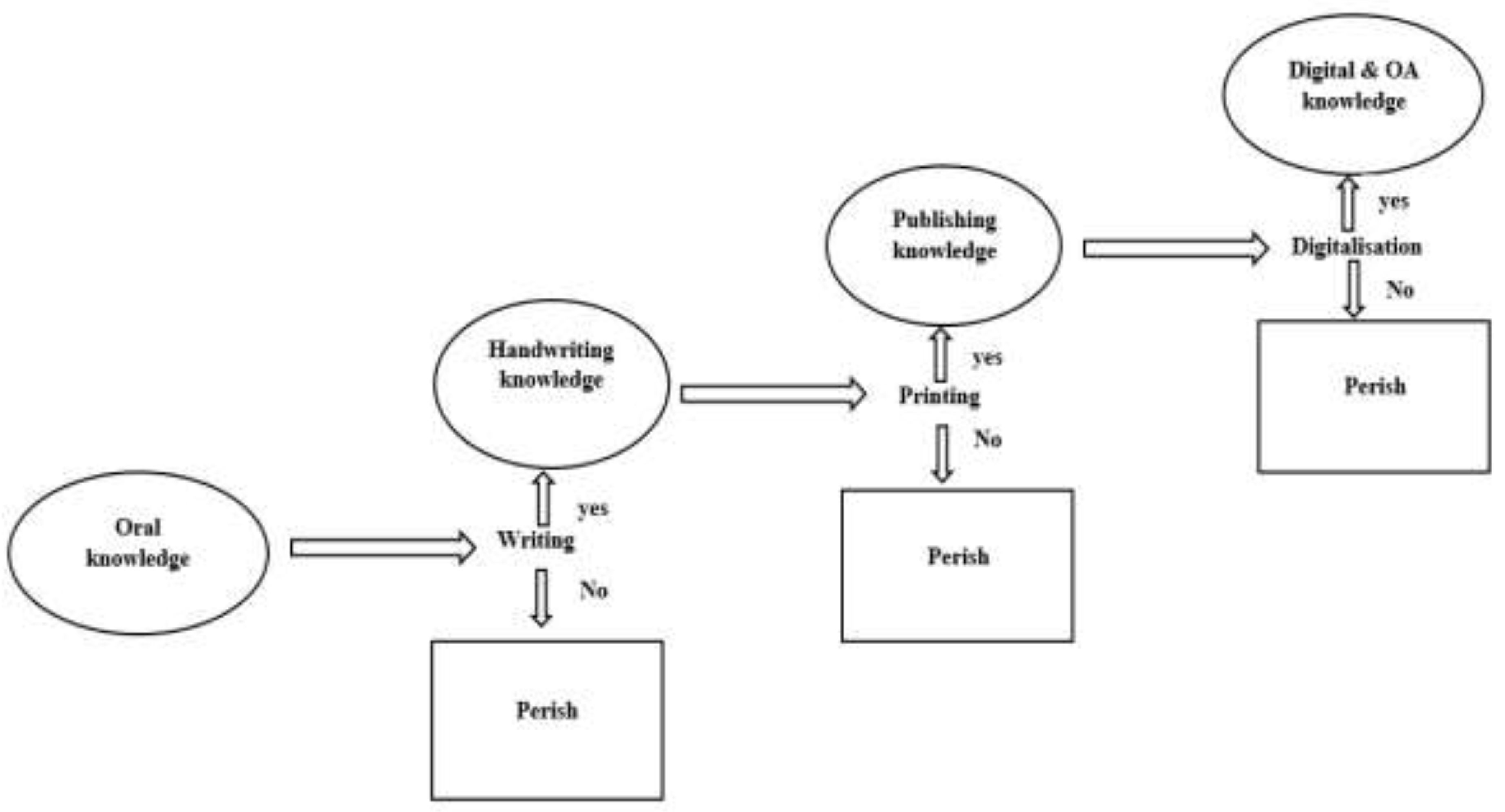

Reflecting on the slogan "publish or perish" in its positive sense, as seen by W.M. Davis (Bowman, 1934; Speight, 1935), as well as on the phrase of I. Bowman (1938) that "civilisation is to a surprising extent based on records", we arrived at a cyclical pattern of creation and death of knowledge (

Figure 1). It shows that oral knowledge dies if it is not put on paper, handwritten knowledge dies if it is not printed, published knowledge dies if it is not digitised and made openly accessible.

Figure 1.

Stages in the evolution of knowledge.

Figure 1.

Stages in the evolution of knowledge.

Published knowledge dies in the long run not only because paper wears out and burns, but also because a new generation of people simply refuses to read material on paper, its representatives believing that what is not on the Internet does not exist in nature.

What the new cycle of death and birth of knowledge will look like is impossible to predict now. What is clear is that the existence of digital and Open Access knowledge will depend on the reliability of its preservation.

But here the situation is very bad. Martin Eve (2024) showed that 32.9% of Crossref members (n = 6982) do not provide adequate digital preservation, contrary to the recommendations of the Digital Preservation Coalition, and Dorothea Strecker et al. (2023) found that 6.2% of all repositories listed in re3data at the end of 2023 (n = 191) were closed.

Therefore, in addition to developing technologies for the secure storage of digital scholarly data, we believe that a limited number of paper copies of Open Access journals should be placed in existing library repositories for legal deposit.

It is also possible to create a separate repository for Open Access journals, to which individual paper copies of these journals would be sent. However, we recognize that these measures are difficult to implement.