1. Introduction

The pericardium is a double-layered membranous structure surrounding the heart, comprising two avascular layers, an outer parietal layer and an inner visceral layer, adherent to epicardium. The pericardial cavity, containing serous fluid, minimizes friction during cardiac motion. It anchors the heart within the thoracic cavity, restricts excessive dilation, and provides mechanical protection. The pericardium also serves as an immunological barrier and maintains optimal cardiac geometry and function. These properties ensure smooth cardiac dynamics and support physiological homeostasis while preventing external damage or pathological overexpansion [

1]. Pericardial adhesions are defined as the formation of fibrous connections between the pericardial layers resulting from inflammation, fibrosis, or other pathological changes within the pericardial cavity. These adhesions can restrict the heart's movement and surrounding structures, leading to the blurring of anatomical layers [

2]. This pathology may increase the risk and complexity of cardiac surgery by hindering intraoperative exposure and compromising the surgeon's ability to visualize the operative field clearly [

3], unanticipated pericardial adhesions encountered during minimally invasive cardiac surgery may compel the surgeon to modify the planned approach, potentially converting it to a more invasive or open procedure, thereby increasing surgical trauma and risk. Additionally, during epicardial catheter ablation, pericardial adhesions can limit catheter maneuverability within the epicardial region, reducing the precision of ablation and potentially prolonging the procedure; this may decrease the short-term success of the intervention [

4]. The primary causes of pericardial adhesions include a history of pericarditis, prior cardiac surgery, and radiation therapy [

5]. However, adhesions have also been observed in patients without these risk factors, with an incidence ranging from 8% to 14.7% [

6], highlighting the importance of preoperative evaluation.

Slippage between the visceral and parietal pericardium is observed in healthy individuals, while the absence of this slippage characterizes those with anatomical pericardial adhesions [

7]. Echocardiography remains the first-line imaging modality for diagnosing most pericardial diseases, while cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) is valuable for its high tissue and temporal resolution [

8]; meanwhile, recent studies have reported favorable outcomes in the evaluation of preoperative pericardial adhesions using the invasive technique of epicardial carbon dioxide insufflation (EpiCO2) [

9]. However, echocardiography is limited by the need for an adequate imaging window and its inability to characterize tissues fully. While providing detailed images, CMR has limitations, including longer acquisition times, higher costs, and potential interference with intracardiac metal implants [

10]. Computed tomography (CT) is particularly effective in visualizing cardiac structures, pericardial thickening, calcification, and generating cardiac motion sequences-4-dimensional computed tomography (4D CT) [

11]. However, there is a lack of methods for quantitatively dynamic analyzing pericardial adhesions using CT.

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is defined as fat located between the myocardium and the visceral pericardium, in direct contact with the pericardium. It is categorized into pericoronary EAT (surrounding the coronary arteries) and myocardial EAT (overlying the myocardium). EAT covers approximately 80% of the heart's surface and can be quantitatively measured using cardiac imaging techniques [

12]. Given the close anatomical relationship between EAT and the pericardium, this study aims to develop a novel, noninvasive, and quantifiable method for assessing pericardial adhesions by analyzing the relative motion between EAT and the pericardium using preoperative CT datasets, with preliminary validation of the method's feasibility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Imaging

This study included 20 patients who underwent multiphase reconstructive computed tomography angiography (CTA) before surgery. Of these, 13 patients were undergoing their first cardiac surgery, with a mean age of 53.2 years, and 12 were male. The remaining seven patients were undergoing redo cardiac surgery (with autologous pericardial suturing during the first procedure), with a mean age of 55.5 years, 6 of whom were male.The patient demographics are summarized in

Table 1.

Operative reports confirmed the presence of extensive pericardial adhesions in all patients undergoing redo surgery and the absence of adhesions in all patients undergoing first-time surgery. Data processors were blinded to the pericardial adhesion status of the patients throughout the study. The Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of the Chinese People's Liberation Army accepted this protocol(S2024-580), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Table 1.

Patient demographic data.

Table 1.

Patient demographic data.

| Patient No. |

Age (y) |

Sex |

BMI |

Present

operation |

Previous

operation |

Interval (y) |

| 1 |

48 |

M |

22 |

Vegetation Removal |

Morrow +MVR+CABG |

1 |

| 2 |

58 |

F |

23.4 |

MVR |

ASDR |

7 |

| 3 |

51 |

M |

27.3 |

TVR |

AVSDR |

35 |

| 4 |

50 |

M |

24.6 |

MVR |

MVP |

31 |

| 5 |

46 |

M |

25.9 |

MVR |

AVSDR |

37 |

| 6 |

43 |

M |

25.1 |

AVR |

AVR |

0.3 |

| 7 |

77 |

M |

24.2 |

TVP |

DVR |

11 |

| 8 |

48 |

M |

24.8 |

AVR |

- |

- |

| 9 |

48 |

M |

30.1 |

CABG |

- |

- |

| 10 |

54 |

M |

29.1 |

CABG |

- |

- |

| 11 |

39 |

M |

22.7 |

MVR+CABG |

- |

|

| 12 |

48 |

M |

28.1 |

CABG |

- |

- |

| 13 |

43 |

M |

29.5 |

MVR |

- |

- |

| 14 |

57 |

M |

24.4 |

AVR |

- |

- |

| 15 |

39 |

M |

25.8 |

CABG |

- |

- |

| 16 |

61 |

M |

29.5 |

CABG |

- |

- |

| 17 |

55 |

M |

28 |

CABG |

- |

- |

| 18 |

65 |

F |

30.8 |

CABG |

- |

- |

| 19 |

45 |

M |

27.7 |

CABG |

- |

- |

| 20 |

62 |

M |

26.6 |

CABG |

- |

- |

CT images were obtained using a GE APEX CT scanner (Revolution Apex, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, MI) in sinus rhythm and during end-expiratory breath-hold. The images were reconstructed in 11 temporal phases, with each assigned an R-R value ranging from -5 to 106%. The in-plane resolution was 0.23 x 0.23 mm, and the slice thickness was 0.625 mm in increments of 0.625 mm. 10.49 mSv was the mean effective dose determined using the European criteria for multilayer CT.

2.2. Pericardial-EAT Motion Analysis Methodology

The workflow consists of four main stages, as shown in

Figure 1: (1) Input Data: cardiac CT images from nine phases (10-90%) are registered to the 50% reference phase, where transformations are applied to the reference pericardial region, followed by cardiac cycle sequence generation and EAT segmentation in deformed regions; (2) Motion Analysis: generation of 3D displacement fields for both pericardium and EAT motion tracking; (3) Motion Disparity: calculation of differential motion within a cylindrical ROI around the left anterior descending (LAD); and (4) Adhesions Analysis: normalization of motion parameters and determination of the optimal cardiac phase with maximum motion disparity. Colored blocks represent different processing stages: input (blue), motion processing (orange), disparity analysis (green), and final output (red).

Figure 1.

Overview of the cardiac motion analysis pipeline for EAT and pericardium.

Figure 1.

Overview of the cardiac motion analysis pipeline for EAT and pericardium.

2.2.1. Pericardial and EAT Segmentation Pipeline

The pericardium was segmented using 3D-Slicer v5.2.2 by an expert with over five years of experience in CTA image interpretation. The reference phase, selected during the end-diastolic phase when myocardial motion is minimal, provided optimal image quality for pericardial boundary delineation. A systematic slice-by-slice segmentation protocol was implemented, with the region of interest (ROI) defined between the diaphragm (inferior boundary) and the pulmonary artery bifurcations (superior boundary). The segmentation workflow was initiated in the axial plane, where the expert initially delineated the pericardial contours on the central slice of the image volume, subsequently proceeding at three-slice intervals in both superior and inferior directions. Coronal and sagittal reconstructions were utilized as reference planes to enhance segmentation accuracy. In regions with ambiguous pericardial boundaries, the expert employed interpolation based on adjacent annotated slices and anatomical knowledge to ensure precise delineation. Following manual contour delineation, automated image interpolation was applied to complete the intermediate unannotated slices, followed by median filtering for contour smoothing. A 3D annotated label map was generated to facilitate comprehensive expert review and refinement of any potential segmentation inconsistencies.

Subsequently, nine cardiac phases (10-90%) were imported and registered to the reference 50% phase using the symmetric diffeomorphic algorithm proposed by Avants et al [

13]. This registration process generated a sequence of transformations represented by a time-varying 3D displacement field. The pericardial region at the reference phase, denoted as

was deformed according to the sequence of transformations to generate a complete cardiac-cycle series of pericardial regions. Specifically, let

denote the transformation at cardiac phase

, where

. The deformed pericardial region at each phase

can be expressed as:

.

Figure 2.

EAT segmentation workflow. (a) Coronary CTA image showing pericardium as a thin white line. (b) Manual segmentation of pericardial region (green). (c) Threshold-based segmentation of adipose tissue within pericardial mask (yellow). (d) 3D reconstructed surfaces of pericardium and EAT.

Figure 2.

EAT segmentation workflow. (a) Coronary CTA image showing pericardium as a thin white line. (b) Manual segmentation of pericardial region (green). (c) Threshold-based segmentation of adipose tissue within pericardial mask (yellow). (d) 3D reconstructed surfaces of pericardium and EAT.

Each transformed region inherits the spatial resolution and topological properties of

, while capturing the phase-specific anatomical deformation. Within each deformed pericardial region

, EAT denoted as

was segmented using a threshold-based approach. Specifically, contiguous voxels with Hounsfield units ranging from −190 to −30 were identified and classified as EAT [

14]. Based on established radiodensity characteristics of adipose tissue, this segmentation method enables precise quantification of the EAT distribution across all cardiac phases, as depicted in

Figure 2.

2.2.2. Motion Field Computation and Point Correspondence

Initially, the displacement fields of the dynamic pericardium and EAT were calculated separately for each cardiac phase. The displacement vectors, denoted as

and

for pericardium and EAT respectively, were computed at each spatial position

and temporal phase

, where

represents the spatial domain. For any given normalized time point

, the displacement vector

was defined as:

where

represents the spatial coordinates of pericardium points at the normalized phase

and

represents the normalized time interval between consecutive frames. Similarly, the displacement vector

for EAT was calculated following the same formulation, with

representing the spatial coordinates of EAT points. To ensure cyclic cardiac motion, the displacement at

was calculated using the first and last phases, creating a cyclic representation of cardiac motion. For each phase, we established point correspondences between the EAT and pericardium by implementing a nearest-point mapping. Specifically, for any point

, its corresponding point on the pericardium

was determined by minimizing the Euclidean distance:

where

denotes the Euclidean norm,

represents the spatial domain of EAT, and

represents the spatial domain of the pericardium.

2.2.3. Motion Disparity Analysis and ROI Definition

The motion difference between corresponding points was quantified by computing the displacement vector difference between each EAT point and its nearest pericardial point. For each corresponding point pair

, the relative displacement difference

was calculated as:

where

represents the local motion disparity at time

. The magnitude of this difference

provides a scalar measure of the motion inconsistency between the pericardium and EAT, with larger values indicating greater motion disparity between the two tissues.

Quantitative analysis of pericardial adhesions in the region adjacent to the coronary arteries required a standardized selection of the assessment range to ensure consistency across all 21 datasets while maintaining reproducibility and anatomical accuracy. Due to the complexity of coronary lesions in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), some patients had occlusion of the right coronary artery, which was not visible on CTA images. Additionally, some patients with a history of secondary surgery had a metallic prosthetic mechanical valve implanted in the mitral position, resulting in the absence of visualization of the left circumflex. The LAD, as the most critical coronary vessel, traverses the anterior interventricular groove where pericoronary adhesions frequently occur. While the proximal LAD, deeply embedded in EAT, is relatively protected from injury and potentially influenced by aortic motion, we focused our quantitative assessment on the mid and distal segments of LAD. This ROI selection ensures more reliable motion analysis and better reflects the interaction between the coronary vessel and surrounding tissues. The ROI was extracted from

along the mid and distal segments of the LAD. Specifically, we defined a cylindrical assessment volume centered on the LAD centerline, formulated as:

where

represents the LAD centerline parameterized by arc length

,

and

denote the starting points of mid and distal segments respectively, and

is the cylinder radius. This

encompasses all epicardial adipose tissue points within the cylindrical volume, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the pericoronary region while maintaining anatomical relevance.

2.2.4. Motion Disparity Quantification and Normalization

For each patient, we first identified the maximum motion difference magnitude across all cardiac phases and point pairs:

The motion difference magnitudes were then normalized to the range [0,1]:

Subsequently, the total motion disparity

at each cardiac phase

was computed by integrating the normalized displacement differences across all corresponding EAT-pericardium point pairs within the defined ROI:

This normalization step ensures standardized comparison across different patients and cardiac phases, while preserving the relative motion patterns between EAT and pericardium. The optimal phase

exhibiting the maximum motion disparity was then determined by:

where

represents the cardiac phase at which the cumulative motion difference between the pericardium and EAT reaches its peak value. This phase-specific analysis enables the identification of the temporal instance where the motion inconsistency between the two tissues is most pronounced, providing a crucial time point for subsequent clinical assessment and visualization.

3. Results

Firstly, we validated the reliability of our motion analysis and its conformity with standard cardiac motion patterns, which is essential for ensuring accurate results; early systole was identified as the phase with the greatest difference in motion. Next, we conducted a quantitative analysis comparing cases with and without pericardial adhesions, our proposed metrics effectively quantify the pericoronary motion differences and establish their reliability for adhesion pattern analysis.

3.1. Reliability Validation of Cardiac Motion Analysis

Since the pericardium exhibits no active motion, the motion difference between the pericardium and the heart is primarily driven by cardiac motion. During systole, relative motion is more pronounced due to active contraction and rapid volume changes, while during diastole, motion is less pronounced due to the heart's predominantly passive dilation, and the entire cardiac cycle exhibits a continuum of changes [

15]. To evaluate the quality and temporal variation of motion differences, we analyzed the distribution characteristics across cardiac phases using the two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test. For each phase pair (

), we computed the KS test statistic:

where

and

represent the empirical distribution functions of motion difference magnitudes at phases

and

, respectively. This analysis yielded a KS statistics matrix and its corresponding p-value matrix, quantifying the dissimilarity between distributions at different phases. The KS statistics and P-value matrices provide strong validation for our chosen motion difference magnitude metric. The KS matrix (range 0-0.2) reveals distinct phase-dependent patterns with appropriate diagonal consistency, while the P-value matrix (range 0.2-1.0) confirms the statistical significance of these variations. The observed gradual transitions between adjacent phases and significant differences between distinct phases (P<0.5) align with expected cardiac motion patterns(

Figure 3-c,d). These results demonstrate that our proposed metric effectively quantifies motion disparity across cardiac phases, establishing its reliability for cardiac motion analysis.

Additionally, we observed that the most significant relative motion difference occurred in the early phases of cardiac contraction, which aligns with the principles of cardiac motion(

Figure 3-a,b). This finding allowed us to identify specific phases for the subsequent quantitative analysis of the ROI.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Motion Disparity Across Cardiac Phases in ROI Surrounding the LAD. (a) Visualization of EAT-pericardium motion differences. The motion difference magnitude is color-coded on the EAT surface, with cooler colors indicating larger displacement differences between corresponding EAT and pericardial points. The greatest relative motion difference occurs during early systole (b) Histograms show the distribution of motion difference magnitude at each cardiac phase. The red curve represents the phase with maximum motion disparity, while the blue curves show other phases. X-axis: normalized displacement differences (range 0.0-1.0); Y-axis: frequency count. (c) KS statistics matrix (d) corresponding P-value matrix computed from pairwise Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests across nine cardiac phases.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Motion Disparity Across Cardiac Phases in ROI Surrounding the LAD. (a) Visualization of EAT-pericardium motion differences. The motion difference magnitude is color-coded on the EAT surface, with cooler colors indicating larger displacement differences between corresponding EAT and pericardial points. The greatest relative motion difference occurs during early systole (b) Histograms show the distribution of motion difference magnitude at each cardiac phase. The red curve represents the phase with maximum motion disparity, while the blue curves show other phases. X-axis: normalized displacement differences (range 0.0-1.0); Y-axis: frequency count. (c) KS statistics matrix (d) corresponding P-value matrix computed from pairwise Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests across nine cardiac phases.

3.2. Quantitative Comparative Analysis of Pericardial Adhesions

The reduced relative motion observed in cases of pericardial adhesions is consistent with intraoperative findings(

Figure 4). All raw data analyzed in this study are available in the

Supplementary Material.

Figure 4.

Visualization of EAT-pericardium motion differences in patients with pericardial adhesion. (a) The spatial distribution of EAT-pericardium motion differences was visualized across the entire epicardial fat region. The phase with maximum motion disparity (marked by a red dashed box) was selected based on normalized displacement differences, with a magnified display focusing on the ROI surrounding the LAD for detailed examination. (b) Intraoperative photographs were obtained to document the actual surgical field during the procedure.

Figure 4.

Visualization of EAT-pericardium motion differences in patients with pericardial adhesion. (a) The spatial distribution of EAT-pericardium motion differences was visualized across the entire epicardial fat region. The phase with maximum motion disparity (marked by a red dashed box) was selected based on normalized displacement differences, with a magnified display focusing on the ROI surrounding the LAD for detailed examination. (b) Intraoperative photographs were obtained to document the actual surgical field during the procedure.

To evaluate the distributional characteristics of pericoronary motion differences between EAT and pericardium, we propose a comprehensive quantitative framework based on novel statistical metrics.

The Peak Ratio (PR) is defined as:

where

represents the maximum frequency value of normalized motion differences and

denotes the frequency value at the α-percentile bin (empirically set to 25th percentile in this study). This metric effectively captures the steepness and decay characteristics of the motion difference distribution along the LAD segments. Additionally, we introduce the Distribution Width Index (DWI), expressed as:

where

represents the count of non-zero frequency bins and

denotes the total number of bins within the defined cylindrical ROI around the LAD centerline.

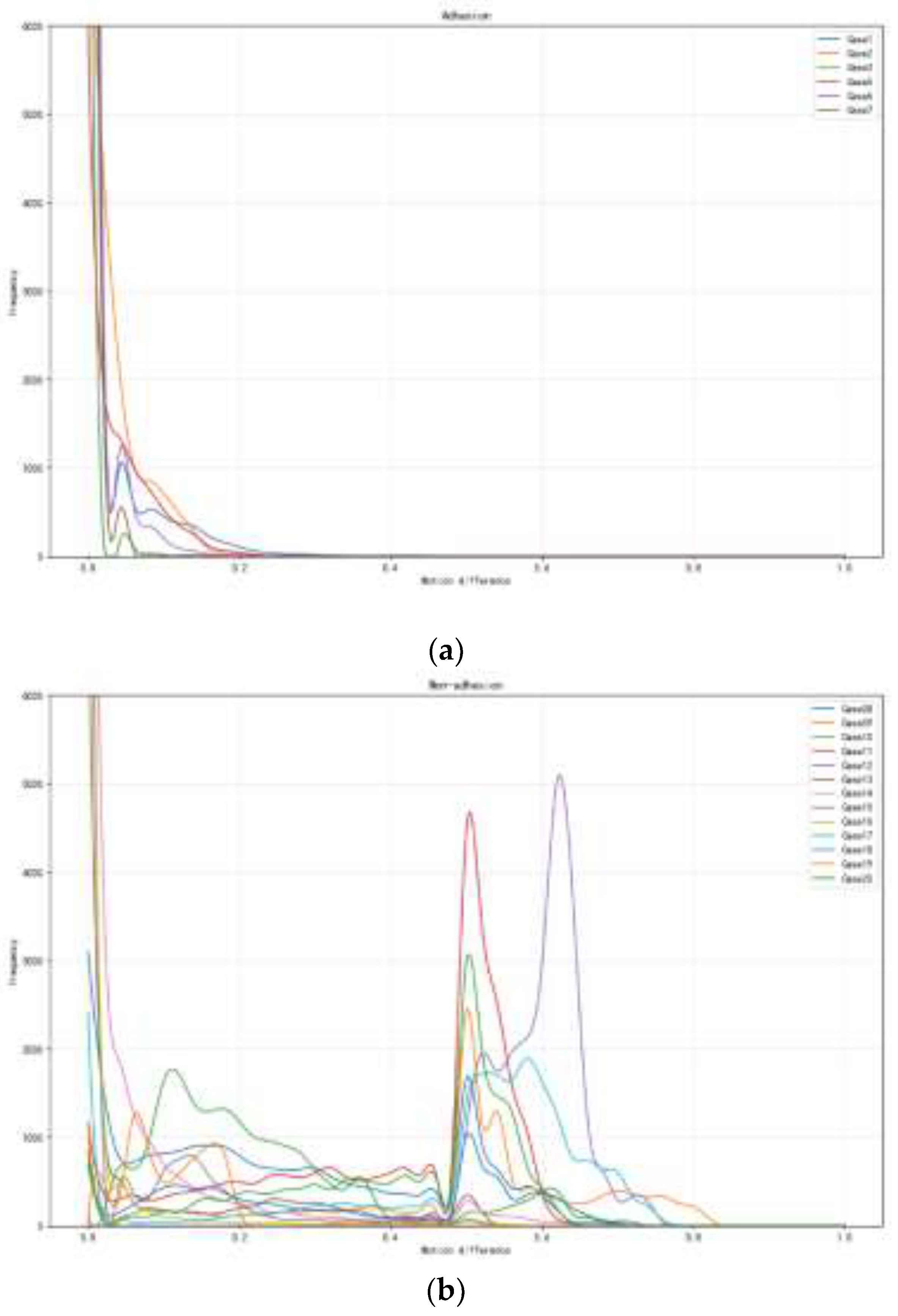

Statistical analysis reveals distinct patterns between adhesion and non-adhesion groups. The adhesion group demonstrates high PR values (>100) coupled with low DWI values (<0.3), indicating highly concentrated motion differences with rapid decay, suggesting restricted relative movement between EAT and pericardium. In contrast, the non-adhesion group exhibits moderate PR values (<50) and higher DWI values (>0.4), reflecting broader distributional patterns with multiple peaks, indicating more natural tissue mobility.

We conducted comprehensive statistical testing to validate these metrics across the standardized ROI along mid and distal LAD segments. The results demonstrate statistically significant differences between the groups (p < 0.01). The PR matrix (range 100-150 for the adhesion group, 20-50 for the non-adhesion group) shows clear group-specific patterns, while the DWI values (range 0.2-0.3 for the adhesion group, 0.4-0.6 for the non-adhesion group) further confirm the distinct motion characteristics(

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Frequency distribution analysis of adhesion and non-adhesion patterns under varying motion differences. (a) The frequency distribution of adhesion patterns for seven experimental cases (Case1-Case7) shows exponential decay with increasing motion difference and peak frequencies near zero motion. (b) Frequency distribution of non-adhesion patterns for 13 experimental cases (Case08-Case20), demonstrating distinct peaks at motion differences between 0.5-0.6, with Case15 exhibiting the highest frequency (~5000). Both analyses reveal contrasting behavioral patterns in adhesion and non-adhesion characteristics across different motion ranges (0-1.0).

Figure 5.

Frequency distribution analysis of adhesion and non-adhesion patterns under varying motion differences. (a) The frequency distribution of adhesion patterns for seven experimental cases (Case1-Case7) shows exponential decay with increasing motion difference and peak frequencies near zero motion. (b) Frequency distribution of non-adhesion patterns for 13 experimental cases (Case08-Case20), demonstrating distinct peaks at motion differences between 0.5-0.6, with Case15 exhibiting the highest frequency (~5000). Both analyses reveal contrasting behavioral patterns in adhesion and non-adhesion characteristics across different motion ranges (0-1.0).

These findings demonstrate that our proposed metrics effectively quantify the pericoronary motion differences, establishing their reliability for adhesion pattern analysis. The combination of PR and DWI provides a robust framework that captures complementary aspects of the tissue motion characteristics while maintaining computational efficiency and anatomical relevance.

4. Discussion

Studies have shown that pericardial thickening or calcification observed on CT images alone is insufficient to rule out the presence of pericardial adhesions. Conversely, these features alone are also inadequate to confirm the diagnosis of pericardial adhesions [

16]. The primary principle in assessing pericardial adhesions should be the relative motion between the pericardium and the heart, making dynamic evaluation essential. The framework proposed in this study assesses pericardial adhesions by dynamically reconstructing the heart's pericardium and the outermost layer, the EAT. In recent years, EAT has been extensively studied due to its strong association with the development of various cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation [

17]. CT has become a standardized imaging tool for evaluating epicardial fat, with mature and increasingly standardized methods for its segmentation and quantification [

18]. Our findings affirmed the reliability and robustness of both the EAT segmentation approach and the proposed motion analysis method: the KS statistics matrix (ranging from 0 to 0.2) revealed distinct, phase-dependent motion patterns with high consistency, while the p-value matrix (ranging from 0.2 to 1.0) confirmed the statistical significance of phase transitions. Gradual changes between adjacent phases and significant differences between distinct phases (P < 0.05) validated the reliability of the proposed motion difference metric. Meanwhile, the study demonstrated that the relative motion differences between EAT and the pericardium were most pronounced during early systole. This insight establishes a reliable phase reference for further quantitative assessments of pericardial adhesion severity.

The multimodal imaging and diagnosis of pericardial adhesions have garnered significant interest, and ultrasound and cardiac MRI can also be dynamically assessed as well as 4DCT [

19]. While high-frequency ultrasound can detect pericardial thickening and its relative motion [

20], it requires a suitable imaging window and has limited tissue characterization capabilities. Cardiac MRI provides a detailed depiction of pericardial thickness and dynamic features. Some studies have defined pericardial adhesions and performed subjective evaluations by observing the sliding motion between the pericardium and the heart, but quantitative assessment methods remain lacking [

21]. Unlike previous studies that often relied on two-dimensional observations, the method proposed in this study enables a comprehensive three-dimensional assessment of pericardial adhesions across different cardiac regions. Through 3D observation, the surgeon can clearly correspond the adhesions to the cardiac structures, providing more spatial location information for reference in developing the surgical plan. Meanwhile, this approach not only allows for more accurate visualization of adhesion patterns but also facilitates quantitative analysis of specific ROI. By incorporating metrics such as PR and DWI, the method provides a robust framework for identifying localized adhesions, as localized adhesions have also been reported [

22]. Since we can measure the specific values of relative motion for any region of interest, we plan to collect additional cases in the future to determine the relative motion values associated with different levels of adhesion. This will allow us to establish quantitative grading indices for varying adhesion conditions, providing more accurate references for clinical decision-making.

Study Limitations

In patients with low volumes of EAT, the area available for assessment may be reduced. Additionally, in cases where pericardial labeling is not feasible—such as in patients undergoing their first surgery without pericardial closure or those with congenital pericardial defects—this method cannot be applied for evaluation.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a novel, noninvasive approach to quantifying pericardial adhesions using 4D CT imaging. By analyzing the relative motion between EAT and the pericardium, we assessed pericardial adhesions by two new metrics (PR and DWI) and demonstrated early systole as the optimal phase for adhesion analysis. The method's ability to quantify adhesion characteristics across any ROI and allow 3D observation highlights its clinical versatility. Future studies aim to expand this framework by incorporating larger datasets to define motion thresholds, thereby providing more precise guidance for clinical decision-making.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Raw processing data for all patients were included in the supplemental material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W. and T.R.; methodology, S.W. and L.Z.; software, S.W.; validation, T.R., N.C. , M.-L.L. and R.W.; formal analysis, S.W. and M.-L.L.; investigation, Z.-K.F.,T.R. and M.-L.L.; resources, Z.-K.F.,N.C. ,R.W., S.W. and L.Z.; data curation, Z.-K.F.,T.R. and S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R. and S.W.; writing—review and editing, N.C.,R.W. and L.Z.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, N.C.,R.W. and L.Z.; funding acquisition, N.C.,R.W. and L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key R&D Plan(2022YFB4700800), National Natural Science Foundation of China(62031020), National Natural Science Foundation of China(62476286), Beijing Science and Technology Plan Project(Z231100005923039).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of the Chinese People's Liberation Army, which accepted this protocol(protocol code: S2024-580).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in thearticle/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| CTA |

Computed tomography angiography |

| 4D CT |

4-Dimensional computed tomography |

| EAT |

Epicardial adipose tissue |

| CMR |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| ROI |

Region of interest |

| CABG |

Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| LAD |

Left anterior descending |

| KS test |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test |

| PR |

Peak ratio |

| DWI |

Distribution width index |

References

- Fatehi Hassanabad, A.; Zarzycki, A.; Deniset, J.F.; Fedak, P.W. An Overview of Human Pericardial Space and Pericardial Fluid. Cardiovascular Pathology 2021, 53, 107346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohal, S.; Mathai, S.V.; Lipat, K.; Kaur, A.; Visveswaran, G.; Cohen, M.; Waxman, S.; Tiwari, N.; Vucic, E. Multimodality Imaging of Constrictive Pericarditis: Pathophysiology and New Concepts. Curr Cardiol Rep 2022, 24, 1439–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbadawi, A.; Hamed, M.; Elgendy, I.Y.; Omer, M.A.; Ogunbayo, G.O.; Megaly, M.; Denktas, A.; Ghanta, R.; Jimenez, E.; Brilakis, E.; et al. Outcomes of Reoperative Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc 2020, 9, e016282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Buch, E.; Boyle, N.G.; Shivkumar, K.; Bradfield, J.S. Incidence and Significance of Adhesions Encountered during Epicardial Mapping and Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Patients with No History of Prior Cardiac Surgery or Pericarditis. Heart Rhythm 2018, 15, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talreja, D.R.; Edwards, W.D.; Danielson, G.K.; Schaff, H.V.; Tajik, A.J.; Tazelaar, H.D.; Breen, J.F.; Oh, J.K. Constrictive Pericarditis in 26 Patients with Histologically Normal Pericardial Thickness. Circulation 2003, 108, 1852–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá, J.; Manoharan, K.; Mann, I.; McCready, J.; Muthurajah, J.; Silberbauer, J. Assessment of Pericardial Adhesions by Means of the EpiCO2 Technique: Brighton Adhesion Classification. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 2187–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.A.; Thompson, D.V.; Rayarao, G.; Doyle, M.; Biederman, R.W.W. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Radiofrequency Tissue Tagging for Diagnosis of Constrictive Pericarditis: A Proof of Concept Study. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2016, 151, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.K.M.; Klein, A.L. Multi-Modality Cardiac Imaging for Pericardial Diseases: A Contemporary Review. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2022, 23, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumont, C.; Oraii, A.; Garcia, F.C.; Supple, G.E.; Santangeli, P.; Kumareswaran, R.; Dixit, S.; Markman, T.M.; Schaller, R.D.; Zado, E.S.; et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Epicardial Carbon Dioxide Insufflation Compared With Conventional Epicardial Access. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology 2024, 10, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, B.; Roobottom, C.; Morgan-Hughes, G. Assessment of the Myocardium with Cardiac Computed Tomography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014, 15, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, Y.; Mel, A.O.; Wheeler, G.; Troupis, J.M. Four-Dimensional Computed Tomography (4DCT): A Review of the Current Status and Applications. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology 2015, 59, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Tan, Y.; Deng, M.; Shan, W.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, B.; Cui, J.; Feng, L.; Shi, L.; Zhang, M.; et al. Epicardial Adipose Tissue, Metabolic Disorders, and Cardiovascular Diseases: Recent Advances Classified by Research Methodologies. MedComm 2023, 4, e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bb, A.; Nj, T.; G, S.; Pa, C.; A, K.; Jc, G. A Reproducible Evaluation of ANTs Similarity Metric Performance in Brain Image Registration. NeuroImage 2011, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Xu, L.; Greenwald, S.E.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; You, H.; Yang, B. Automatic Quantification of Epicardial Adipose Tissue Volume. Medical Physics 2021, 48, 4279–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Markl, M.; Föll, D.; Hennig, J. Investigating Myocardial Motion by MRI Using Tissue Phase Mapping. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006, 29, S150–S157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajaji, W.; Xu, B.; Sripariwuth, A.; Menon, V.; Kumar, A.; Schleicher, M.; Isma’eel, H.; Cremer, P.C.; Bolen, M.A.; Klein, A.L. Noninvasive Multimodality Imaging for the Diagnosis of Constrictive Pericarditis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 2018, 11, e007878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, G. Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Contemporary Cardiology. Nature Reviews. Cardiology 2022, 19, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y, L.; S, S.; Y, S.; N, B.; B, Y.; L, X. Segmentation and Volume Quantification of Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Computed Tomography Images. Medical physics 2022, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.L.; Wang, T.K.M.; Cremer, P.C.; Abbate, A.; Adler, Y.; Asher, C.; Brucato, A.; Chetrit, M.; Hoit, B.; Jellis, C.L.; et al. Pericardial Diseases: International Position Statement on New Concepts and Advances in Multimodality Cardiac Imaging. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2024, 17, 937–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, M.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Z.; Lin, F.; Yang, X.; Xi, D.; Chen, Y.; et al. Evaluation of Pericardial Thickening and Adhesion Using High-Frequency Ultrasound. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2023, 36, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.A.; Thompson, D.V.; Rayarao, G.; Doyle, M.; Biederman, R.W.W. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Radiofrequency Tissue Tagging for Diagnosis of Constrictive Pericarditis: A Proof of Concept Study. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2016, 151, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Q.; Yun, L.; Xu, R.; Li, G.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. A Rare Chronic Constrictive Pericarditis with Localized Adherent Visceral Pericardium and Normal Parietal Pericardium: A Case Report. Front. Med. 2016, 10, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).