Submitted:

19 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment

2.2. Clinical and Laboratory Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

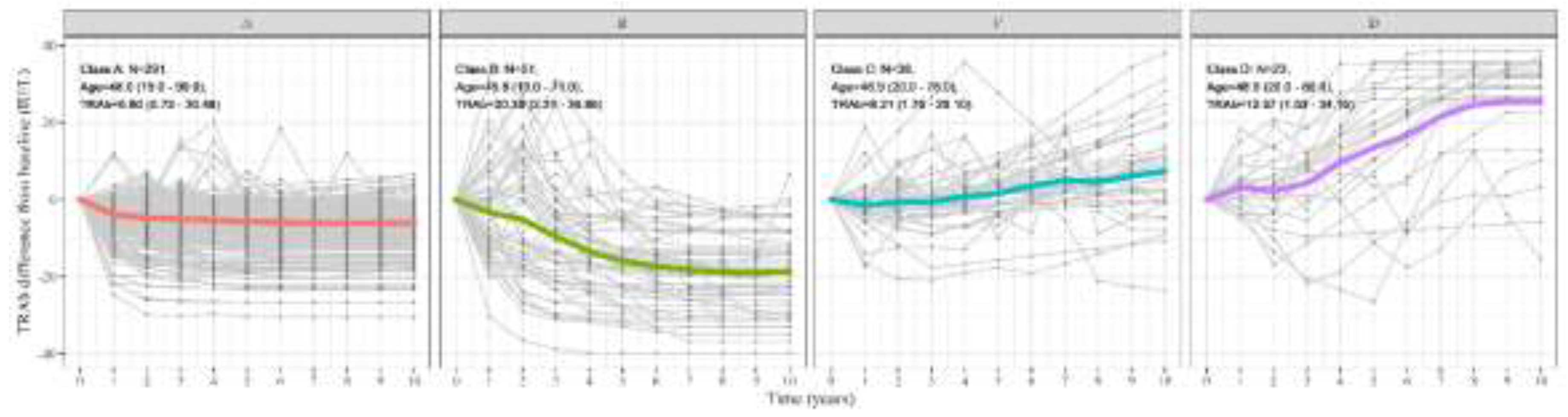

3.1. Patterns of TRAb Over Time and Overall Clinical Information

3.2. Two Main Patterns Based on Normalization Rate

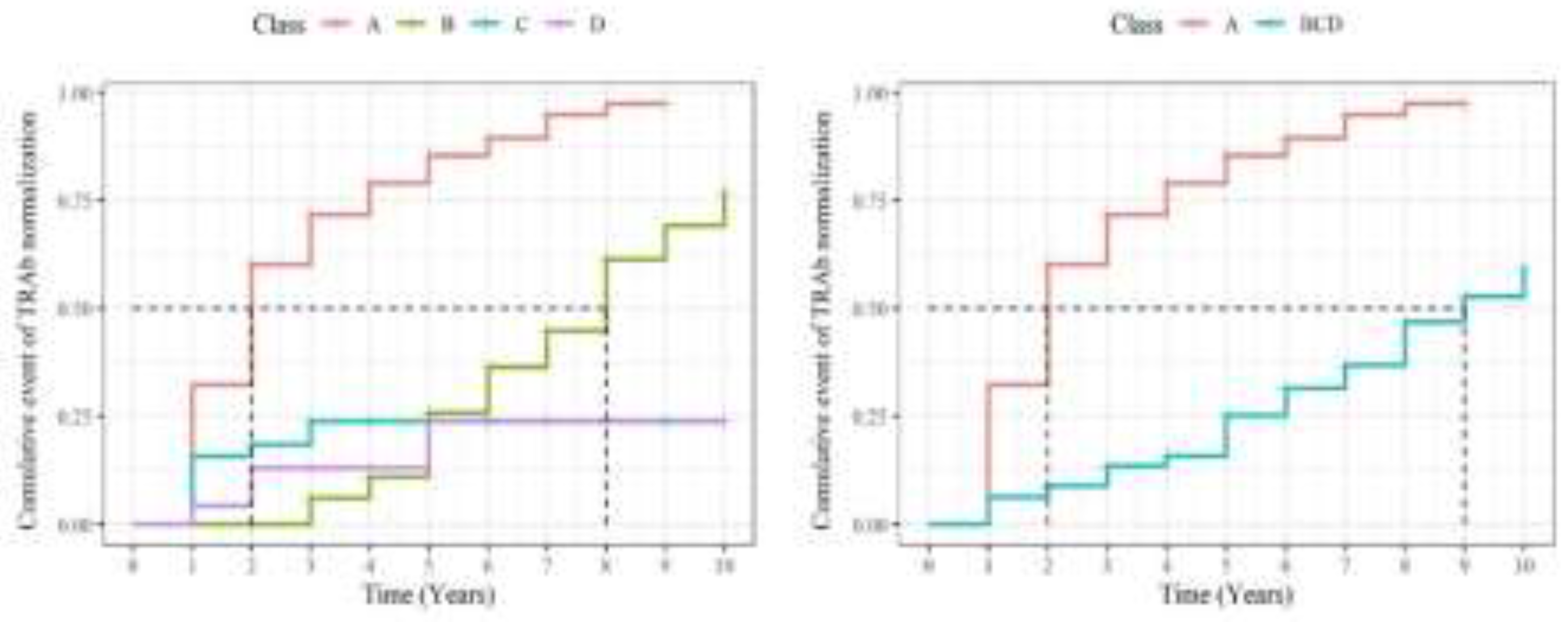

3.3. Survival Analysis of TRAb

3.4. Prognostic Factors Associated with Patterns

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, D. Pathogenesis of the Hyperthyroidism of Graves's Disease. British medical journal 1965, 1, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozzoli, R.; Bagnasco, M.; Giavarina, D.; Bizzaro, N. TSH receptor autoantibody immunoassay in patients with Graves' disease: improvement of diagnostic accuracy over different generations of methods. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmunity reviews 2012, 12, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurberg, P.; Wallin, G.; Tallstedt, L.; Abraham-Nordling, M.; Lundell, G.; Tørring, O. TSH-receptor autoimmunity in Graves' disease after therapy with anti-thyroid drugs, surgery, or radioiodine: a 5-year prospective randomized study. European Journal of Endocrinology 2008, 158, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamura, Y.; Nakano, K.; Uruno, T.; Ito, Y.; Miya, A.; Kobayashi, K.; et al. Changes in serum TSH receptor antibody (TRAb) values in patients with Graves' disease after total or subtotal thyroidectomy. Endocrine journal 2003, 50, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Du, W.-H.; Zhang, C.-X.; Zhao, S.-X.; Song, H.-D.; Gao, G.-Q.; et al. The effect of radioiodine treatment on the characteristics of TRAb in Graves’ disease. BMC Endocrine disorders 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesarghatta Shyamasunder, A.; Abraham, P. Measuring TSH receptor antibody to influence treatment choices in Graves’ disease. Clinical endocrinology 2017, 86, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.S.; Burch, H.B.; Cooper, D.S.; Greenlee, M.C.; Laurberg, P.; Maia, A.L.; et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association guidelines for diagnosis and management of hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1343–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.S.; Choi, H.-Y. Prognostic significance of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies in moderate-to-severe graves’ orbitopathy. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 14, 1153312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Bahn, R. Immunopathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy: the role of the TSH receptor. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2012, 26, 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein, A.; Esser, J.; Mann, K.; Schott, M. Clinical value of TSH receptor antibodies measurement in patients with Graves' orbitopathy. Pediatric endocrinology reviews: PER 2010, 7, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Shiber, S.; Stiebel-Kalish, H.; Shimon, I.; Grossman, A.; Robenshtok, E. Glucocorticoid regimens for prevention of Graves' ophthalmopathy progression following radioiodine treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 2014, 24, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Choi, M.S.; Park, J.; Park, H.; Jang, H.W.; Choe, J.-H.; et al. Changes in thyrotropin receptor antibody levels following total thyroidectomy or radioiodine therapy in patients with refractory Graves' disease. Thyroid 2021, 31, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbesino, G.; Tomer, Y. Clinical utility of TSH receptor antibodies. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013, 98, 2247–2255. [Google Scholar]

- Genolini, C.; Falissard, B. KmL: k-means for longitudinal data. Computational Statistics 2010, 25, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genolini, C.; Falissard, B. KmL: A package to cluster longitudinal data. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2011, 104, e112–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Bartalena, L.; Hegedüs, L.; Leenhardt, L.; Poppe, K.; Pearce, S.H. 2018 European Thyroid Association guideline for the management of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. European thyroid journal 2018, 7, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitti, P.; Rago, T.; Chiovato, L.; Pallini, S.; Santini, F.; Fiore, E.; et al. Clinical features of patients with Graves' disease undergoing remission after antithyroid drug treatment. Thyroid 1997, 7, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, N.N.Z.; Beckett, G.; Zammitt, N.N.; Strachan, M.W.; Seckl, J.R.; Gibb, F.W. Thyrotropin receptor antibody levels at diagnosis and after thionamide course predict Graves' disease relapse. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, B.H.; Kim, M.; Hong, A.R.; Park, J.; Park, H.; et al. The longer the antithyroid drug is used, the lower the relapse rate in Graves’ disease: a retrospective multicenter cohort study in Korea. Endocrine 2021, 74, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyrotoxicosis ATAaAAoCEToHaOCo, Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Garber JR, Greenlee MC, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid 2011, 21, 593–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereidoun, Azizi., Miralireza, Takyar., Elham, Madreseh., Elham, Madreseh., Atieh, Amouzegar. (2019). 4. Treatment of Toxic Multinodular Goiter: Comparison of Radioiodine and Long-Term Methimazole Treatment. Thyroid.

- Kiminori, Sugino., Takashi, Mimura., Osamu, Ozaki., Hiroyuki, Iwasaki., Nobuyuki, Wada., Akihiko, Matsumoto., Kunihiko, Ito. (1996). 3. Preoperative Change of Thyroid Stimulating Hormone Receptor Antibody Level: Possible Marker for Predicting Recurrent Hyperthyroidism in Patients with Graves’ Disease after Subtotal Thyroidectomy. World Journal of Surgery.

- Villagelin, D.; Romaldini, J.H.; Santos, R.B.; Milkos, A.B.; Ward, L.S. Outcomes in relapsed Graves' disease patients following radioiodine or prolonged low dose of methimazole treatment. Thyroid 2015, 25, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelli, C.; Gandossi, E.; Castellano, M.; Pizzocaro, C.; Agosti, B.; Delbarba, A.; et al. Prognostic value of thyrotropin receptor antibodies (TRAb) in Graves' disease: a 120 months prospective study. Endocrine journal 2007, 54, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivangi, Dwivedi., Tejas, Kalaria., Harit, Buch. (2022). 1. Thyroid autoantibodies. Journal of Clinical Pathology.

- Nalla, P.; Young, S.; Sanders, J.; Carter, J.; Adlan, M.A.; Kabelis, K.; et al. Thyrotrophin receptor antibody concentration and activity, several years after treatment for Graves’ disease. Clinical Endocrinology 2019, 90, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, M.H. Serum TSH Receptor Antibodies Fall Gradually and Only Rarely Switch Functional Activity in Treated Graves’ Disease. Clinical Thyroidology 2019, 31, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, F.; Abdi, H.; Mehran, L.; Perros, P.; Masoumi, S.; Amouzegar, A. Long-term follow-up of graves orbitopathy after treatment with short-or long-term methimazole or radioactive iodine. Endocrine Practice 2023, 29, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanda, M.; Piantanida, E.; Liparulo, L.; Veronesi, G.; Lai, A.; Sassi, L.; et al. Prevalence and natural history of Graves' orbitopathy in a large series of patients with newly diagnosed graves' hyperthyroidism seen at a single center. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013, 98, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, N.; Noh, J.Y.; Yoshimura, R.; Mikura, K.; Kinoshita, A.; Suzuki, A.; et al. Does age or sex relate to severity or treatment prognosis in Graves' disease? Thyroid 2021, 31, 1409–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, M.; Gough, S. Unravelling the genetic complexity of autoimmune thyroid disease: HLA, CTLA-4 and beyond. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 2004, 136, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

| Overall | A | B | C | D | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 403 | 291 (72.2) | 51 (12.6) | 38 (9.4) | 23 (5.7) | |

| Follow up duration (year) | 4.88 (2.33) | 4.68 (2.30) | 5.84 (2.44) | 5.21 (2.18) | 4.74 (2.12) | 0.006 |

| Age (year) | 47.65 (15.58) | 47.96 (15.10) | 45.80 (15.49) | 46.95 (17.92) | 48.96 (18.25) | 0.837 |

| Sex (male: female) | 111 : 292 | 78 : 213 | 11:40 | 13:25 | 9:14 | 0.336 |

| Disease duration (year) | 0.49 (0.86) | 0.39 (0.69) | 1.02 (1.48) | 0.46 (0.70) | 0.55 (0.81) | 0.018 |

| Graves' orbitopathy comorbidity (N (%)) | 63 (16%) | 47 (16%) | 8 (16%) | 4 (11%) | 4 (17%) | 0.876 |

| Methimazole | 359 (89%) | 257 (88%) | 46 (90%) | 36 (95%) | 20 (87%) | 0.697 |

| Methimazole prescription (day) | 1,320 (993) | 1,118 (910) | 1,858 (1,078) | 1,815 (944) | 1,792 (1,027) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 40 (9.9%) | 32 (11%) | 4 (7.8%) | 2 (5.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.759 |

| Radioactive iodine treatment | 47 (12%) | 16 (5.5%) | 18 (35%) | 6 (16%) | 7 (30%) | <0.001 |

| Thyroidectomy | 5 (1.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (3.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.006 |

| Baseline TRAb (IU/L) | 8.98 (8.00) | 6.80 (5.42) | 20.39 (10.21) | 8.21 (6.36) | 12.57 (9.93) | <0.001 |

| 10-year average of TRAb (IU/L) | 4.76 (6.38) | 1.81 (1.36) | 7.72 (3.05) | 10.61 (3.47) | 25.88 (4.12) | <0.001 |

| 10-year SD of TRAb (IU/L) | 4.10 (3.74) | 2.36 (1.74) | 8.86 (2.49) | 6.00 (3.44) | 12.36 (3.40) | <0.001 |

| Change rate of TRAb (IU/L/year) | -0.29 (1.26) | -0.41 (0.41) | -1.98 (0.77) | 0.88 (1.28) | 2.95 (1.65) | <0.001 |

| Normalization rate of TRAb (N (%)) | 333 (83%) | 278 (96%) | 41 (80%) | 11 (29%) | 3 (13%) | <0.001 |

| Period to normalization (year) | 2.60 (1.87) | 2.39 (1.64) | 5.85 (2.03) | 1.56 (0.88) | 2.50 (1.73) | <0.001 |

| Overall | A | BCD | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 403 | 291 (72.2) | 112 (27.7) | |

| Follow up duration (year) | 4.88 (2.33) | 4.68 (2.30) | 5.40 (2.32) | 0.002 |

| Age (year) | 47.65 (15.58) | 47.96 (15.10) | 46.84 (16.81) | 0.592 |

| Sex (male : female) | 111 : 292 | 78 : 213 | 33 : 79 | 0.592 |

| Disease duration (year) | 0.49 (0.86) | 0.39 (0.69) | 0.73 (1.16) | 0.004 |

| Graves' orbitopathy comorbidity (N (%)) | 63 (16%) | 47 (16%) | 16 (14%) | 0.644 |

| Methimazole | 359 (89%) | 257 (88%) | 102 (91%) | 0.427 |

| Methimazole prescription duration (day) | 1,320 (993) | 1,118 (910) | 1,830 (1,013) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 40 (9.9%) | 32 (11%) | 8 (7.1%) | 0.246 |

| Radioactive iodine treatment | 47 (12%) | 16 (5.5%) | 31 (28%) | <0.001 |

| Thyroidectomy | 5 (1.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (3.6%) | 0.022 |

| Baseline TRAb (IU/L) | 8.98 (8.00) | 6.80 (5.42) | 14.65 (10.50) | <0.001 |

| 10-year average of TRAb (IU/L) | 4.76 (6.38) | 1.81 (1.36) | 12.43 (7.77) | <0.001 |

| 10-year SD of TRAb (IU/L) | 4.10 (3.74) | 2.36 (1.74) | 8.61 (3.78) | <0.001 |

| Change rate of TRAb (IU/L/year) | -0.29 (1.26) | -0.41 (0.41) | 0.00 (2.28) | <0.001 |

| Normalization rate of TRAb (N (%)) | 333 (83%) | 278 (96%) | 55 (49%) | <0.001 |

| Period to normalization (year) | 2.60 (1.87) | 2.39 (1.64) | 4.27 (2.64) | <0.001 |

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

| Characteristic | Survival ratio | 95%Confidence interval | p-value | Survival ratio | 95%Confidence interval | p-value |

| TRAb pattern | ||||||

| D | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

| A | 8.873 | 3.285, 23.97 | <0.001 | 8.391 | 3.087, 22.81 | <0.001 |

| B | 1.860 | 0.635, 5.445 | 0.258 | 1.858 | 0.632, 5.461 | 0.260 |

| C | 1.422 | 0.437, 4.626 | 0.559 | 1.218 | 0.373, 3.981 | 0.744 |

| Sex | ||||||

| M | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

| F | 1.227 | 0.942, 1.598 | 0.129 | 1.317 | 1.007, 1.723 | 0.044 |

| Age (year) | ||||||

| 19≤ and <49 | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

| 49≤ | 1.065 | 0.846, 1.341 | 0.590 | 1.096 | 0.864, 1.391 | 0.449 |

| GO comorbidity | ||||||

| No | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

| Yes | 1.056 | 0.760, 1.466 | 0.747 | 1.135 | 0.805, 1.601 | 0.470 |

| Methimazole | ||||||

| No | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

| Yes | 0.866 | 0.608, 1.233 | 0.424 | 1.096 | 0.763, 1.575 | 0.618 |

| Statin | ||||||

| No | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

| Yes | 1.188 | 0.823, 1.715 | 0.358 | 1.1 | 0.747, 1.620 | 0.630 |

| RAI treatment | ||||||

| No | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

| Yes | 0.415 | 0.272, 0.632 | <0.001 | 0.715 | 0.459, 1.113 | 0.138 |

| Thyroidectomy | ||||||

| No | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

| Yes | 1.896 | 0.266, 13.53 | 0.523 | — | — | |

| Baseline TRAb (IU/L) | ||||||

| 6.14≤ | 2.104 | 1.660, 2.666 | <0.001 | 1.746 | 1.363, 2.235 | <0.001 |

| 1.5≤ and <6.14 | 1 | Ref. | — | — | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).