1. Introduction

Machine learning (ML) has revolutionized various fields, particularly healthcare, where accurate disease diagnosis is critical. In recent years, ML models have become capable of diagnosing and classifying diseases as good or better than healthcare experts [

1]. However, many large models require large amounts of data to be effective. This makes training these large models exceptionally difficult, leading to state-of-the-art models to train collaboratively (due to scarcity of data) [

2]. This practice of training in collaboration often relies on these large volumes of data being stored in a single (centralized) location to be trained on—this practice is known as centralized learning [

3].

However, in almost all commercial fields/industries, using Centralized Learning (CA) is often impossible because of the many privacy regulations regarding personal data [

4]. Some of these regulations include the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in the United States (HIPAA), the General Data Protection Regulation in the European Union (GDPR), and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act in Canada (PIPEDA) [

5,

6,

7]. These regulations restrict personal health data’s free flow, making CL often unfeasible. Additionally, the computational overhead when using CL can be prohibitively expensive, as all training would typically be done on a singular server. This centralized approach strains resources, making it less practical in healthcare scenarios where large-scale data needs to be processed efficiently and securely to develop effective, high-performing ML models [

8,

9].

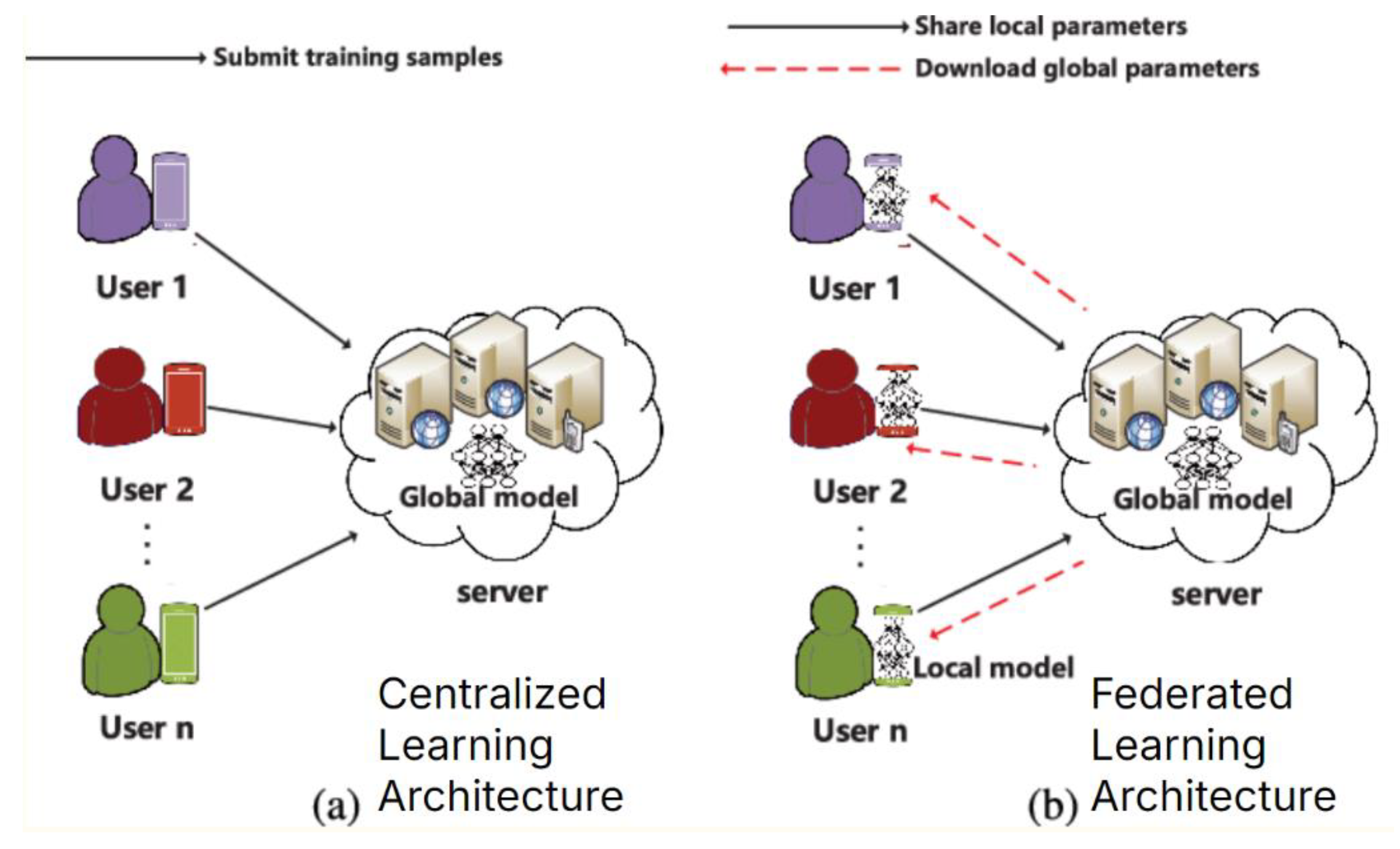

Figure 1 demonstrates the differences between CL and Federated Learning (FL).

As can be seen from

Figure 1, CL gathers all training data in one place, a central server, where a single model is trained and then distributed. In contrast, FL distributes the training process by allowing users to train models locally on their own devices without sharing their raw data. Only model updates are sent to a central server, aggregating them to improve a global model that is then shared with the users. This approach enhances privacy, reduces communication overhead, and allows for more personalized models compared to the centralized approach [

10,

11].

FL is a relatively new collaborative ML technique that can sidestep almost all the mentioned issues with ease [

12,

13]:

FL trains local models on each user’s data and aggregates models together to create a global model (without directly seeing any data).

This ensures privacy when training models through techniques such as differential privacy.

FL often adds random noise to datasets to prevent revealing sensitive information about any individual patient used in the data (often using the differential privacy method) [

14].

Computing power can become distributed (computations for training are split across the different clients participating in FL instead of just a singular centralized server).

To address the healthcare dataset-sharing and collaborative model training challenges posed by privacy laws and regulations, this study developed a novel FL architecture. Unlike traditional FL approaches, which often suffer from up to a 55% loss in model accuracy, the methods utilized in this architecture achieve only an average of 1.25% loss in accuracy (nearly 54% accuracy improvement) when applied to ophthalmology [

15].

The following research questions guided this study:

(R1) How can FL be leveraged for efficient collaboration in the eye healthcare space?

(R2) How can FL maintain high accuracy and minimize performance loss compared to CL?

(R3) In FL, how can the computational power of training models be effectively distributed to the clients without sacrificing the training time/speed required for an effective global model?

This research hopes to comprehensively analyze FL’s potential within the eye healthcare space by answering these research questions, allowing for security/privacy and effective collaboration. While the architecture developed in this study has potential application to any healthcare domain (where data privacy is of utmost concern), it specifically focused on applying FL for ocular health.

2. Related Work

Many studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of applying ML to improving disease diagnosis in healthcare, especially within ophthalmology and the eye healthcare space.

Vepula et al. examined the detection of multi-stage glaucoma, including its many early stages [

16]. The researchers did so by leveraging standard, centralized-learning-based, pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and voting-based classifier fusion. In doing so, they achieved an 84.53% accuracy on the Harvard Dataverse dataset. Sigit et al. proposed a practical method for detecting cataracts, one of the leading causes of visual impairment and blindness worldwide [

17]. They applied a single-layer perceptron method and smartphones to classify the results of normal eyes, immature cataracts, and mature cataracts with an accuracy of 85%. Saqib et al. also demonstrated an effective system for cataracts and glaucoma detection [

18]. It was accomplished by leveraging Transfer Learning (TL) using the MobileNetV1 and MobileNetV2 models, achieving a detection accuracy of 89%. All three of these studies show how ML and CL have been proven effective in transforming the effectiveness and precision of disease diagnosis, especially within the eye healthcare space. However, these models do not allow for secure, collaborative model training. Therefore, these proposed systems are ineffective in environments with data privacy restrictions or regulations, where FL offers plenty of advantages.

The application of FL in other fields has gained significant momentum in recent years. Several comprehensive surveys have provided overviews of FL and its challenges and applications within various domains. Liu et al. presented a systematic study of recent advances in FL, discussing challenges such as data heterogeneity, communication overhead, and privacy concerns [

19]. This highlights the idea that utilizing FL in any discipline has advantages and disadvantages that must be balanced. Similarly, Wenet al. offered an extensive review of FL, highlighting its potential applications and the challenges faced in practical implementations [

20].

Work has also begun to discuss the application of FL in many fields, including healthcare and medical imaging. For instance, in medical imaging (particularly brain tumor detection), Islam et al. showcased FL’s effectiveness when combined with CNN ensemble architectures in classifying brain tumors from MRI images [

21]. Their work demonstrated the potential of FL in healthcare, providing concrete evidence of how FL can facilitate and allow for collaborative learning without compromising the privacy of Personal Information (PI) patient data. However, as mentioned earlier, FL faces issues regarding accuracy reductions—in this study, the base ensemble model (non-FL approach) had an accuracy of 96.68%, while the FL achieved 91.05% accuracy. Although accuracy only had a slight decline, maintaining accuracy in a field as critical and crucial as healthcare is still of utmost importance.

Observations can also be made based on the work completed by Li et al., which leveraged FL to address the medical data privacy regulations when training models for brain tumor segmentation specifically [

22]. Based on their work, it was noted that there was a trade-off between model performance and level of privacy protection. It was found that when more of the models are shared, the amount of noise that must be added to the data (through the differential-privacy methods) must also increase, causing the model performance to decrease due to increased noise. Their work argues that sharing a smaller percentage of the models (e.g., 10% instead of 40%) can often yield a more favorable trade-off between having an optimal amount of privacy and the performance of the models in FL systems. This is especially important because it emphasizes how the optimal FL architecture must consider these drawbacks and advantages to effectively balance facets such as accuracy, training time, and privacy cost.

In summary, significant research progress and work have been made to improve the drawbacks found in FL, to apply FL for the healthcare space, and to leverage its benefit for private model collaboration. The work found in this study aims to build upon these foundations by developing a more accurate and more resource-efficient FL architecture tailored specifically for private, collaborative training in the eye healthcare space.

3. Methodology

The detailed methodology of this study is outlined below.

3.1. Project Dataset

This study utilized the Ocular Disease Intelligent Recognition (ODIR) dataset from Li et al., which consists of 10,000 colored fundus photographs taken from patients’ left and right eyes [

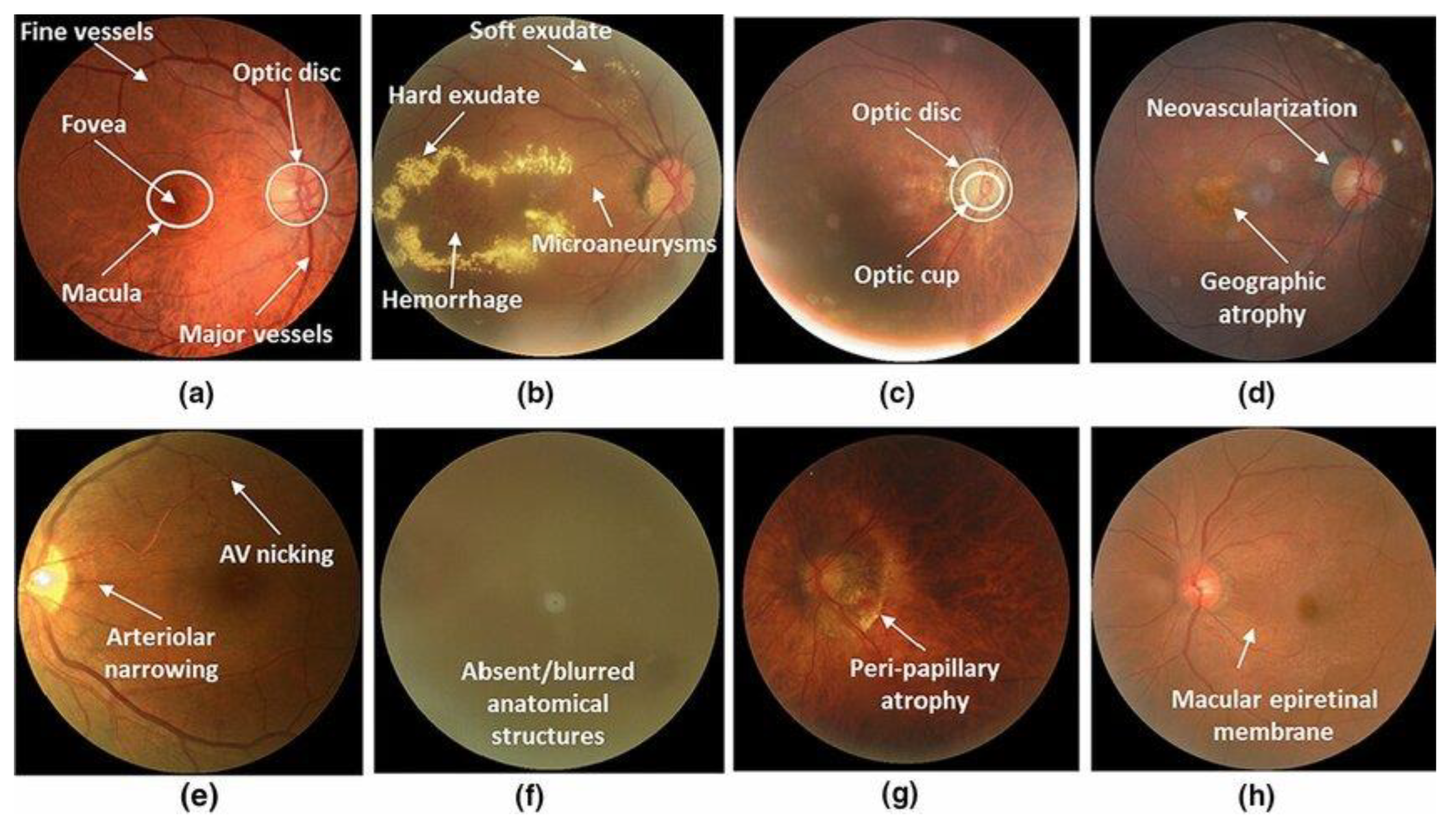

23]. The dataset is designed to simulate real-world data, containing non-independent and Identically Distributed (non-IID) images captured using various types of cameras, resulting in different image resolutions and quality. The diversity of images in this data will accurately reflect the challenges faced when collaborating with data from various locations (e.g., hospitals). The dataset is divided into eight different fundus disease categories: normal, diabetes, hypertension, glaucoma, cataract, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), myopia, and other abnormalities, as depicted in

Figure 2:

3.2. Data Preprocessing

For this study, three classes were used: normal (N), glaucoma (G), and cataract (C). The dataset size has 3,402 images with a 64:16:20 train-validation-test split. As explained in more detail later in the paper, FL architecture had several clients, and the dataset was evenly (and randomly) split across these clients to ensure consistency.

Data preprocessing is an ML technique that transforms raw data into an understandable and desired form [

24]. Since the data is non-IID and varies throughout, the dataset must be preprocessed before any model training. This would allow for improved accuracy, reliability, and overall robustness of the ML models when trained in this study [

25].

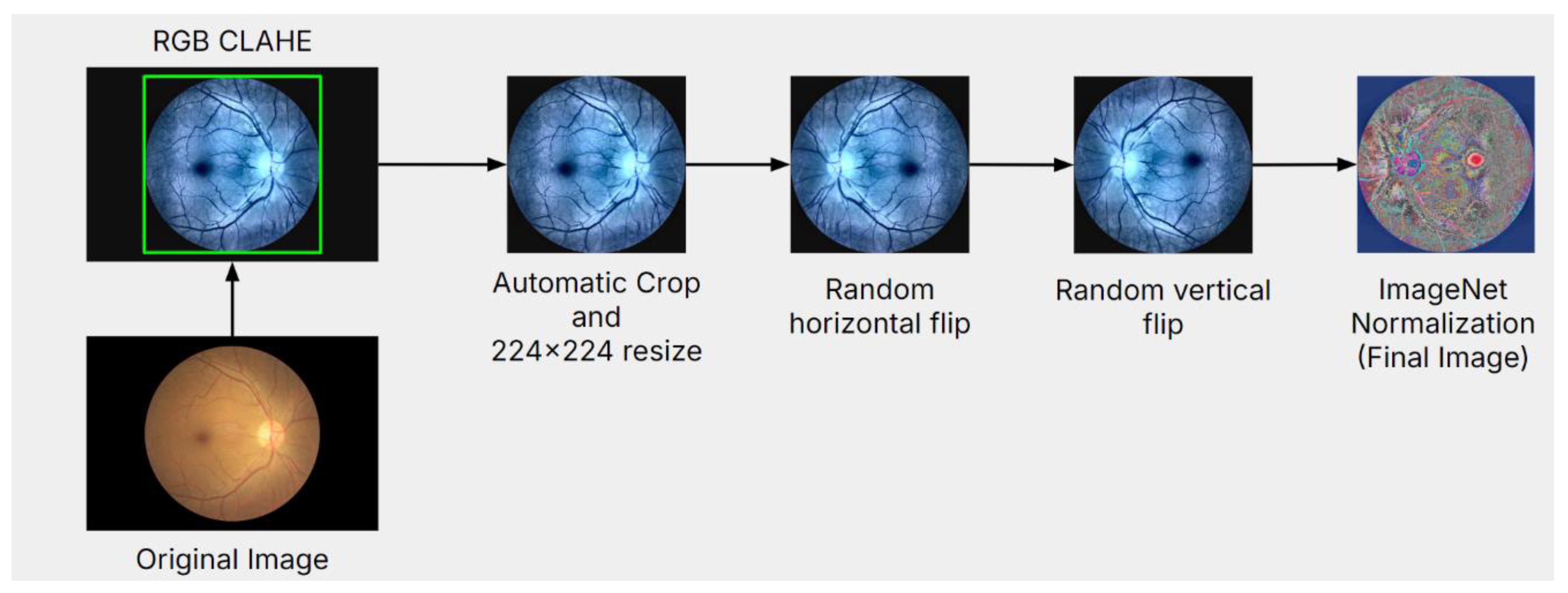

Figure 3 demonstrates the data preprocessing steps.

Images were first augmented using RGB Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) Transform [

26]. RGB CLAHE enhanced the ocular images by improving image contrast and overall luminance, emphasizing the blood vessels/veins for more efficient model training.

After feature augmentation, all images were applied using a simple “bounding box” image extraction algorithm (crops out an outermost, square-shaped border based on the colored pixels of the fundus images, removing any white space outside the square border). After the edges of the eye were extracted correctly, all images were cropped to remove the blank space to prevent models from analyzing anything besides the ocular image.

Afterward, several general transformations were applied to the entire dataset. First, the images were resized to 224x224 pixels to ensure all data was consistent for the models to train on. Then, the data was augmented using random horizontal and vertical flipping to improve overall model robustness. There was a 50% probability of the data being mirrored. Studies have shown that performing data augmentation like this will reduce the chances of model covering and improve the model’s generalization ability.

Due to TL being implemented in this study’s proposed architecture, the data was normalized using the ImageNet Dataset’s Mean and Standard Deviation. Normalizing the data to match what the VGG-19 neural network was trained on ensured that the TL used in this architecture remains efficient.

3.3. Transfer Learning and CNN Architectures

TL is an ML method that allows a model to use knowledge gained from one dataset/task to improve its performance on a related task [

27]. This study will leverage TL to help reduce overall model training time, using the VGG-19 CNN Model—trained on the ImageNet dataset with nearly 1.2 million photos and 1000 classes [

28].

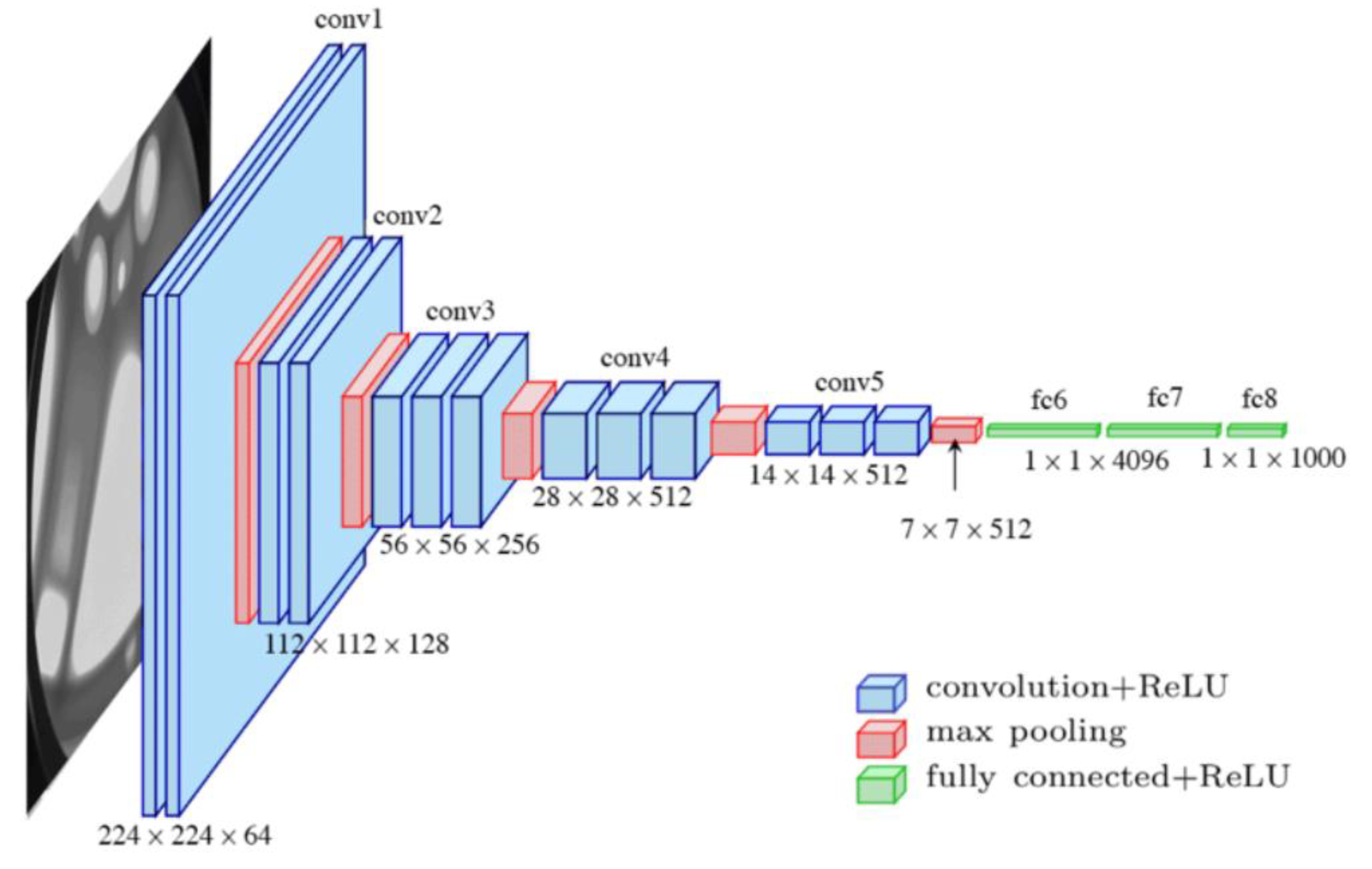

Figure 4 represents the VGG-19 model used in this study and its architecture.

The weights of the model’s feature layers were frozen (not trained on). This allows for faster training convergence and effective TL. In

Figure 4, the classier layer is shown in green. The classifier layers are as follows: following the feature layers, a dense layer consisting of 4096 neurons, a ReLU activation layer, and a 50% dropout layer were added (to prevent model overfitting by randomly removing half of the neuron connection from our model during each training iteration). This group of the three layers was added twice. The CNN architecture used in this study combines multiple layers of convolution, max-pooling, and fully connected layers to extract and consolidate features progressively. It is optimized for image classification tasks and can be fine-tuned for other medical imaging tasks.

3.4. Model Training and Experimental Setup

The models trained in this study were built using PyTorch 2.2.0 and an NVIDIA RTX 3070 GPU for this experimental setup. The Flower framework was used to construct the FL simulation. Computer resources were distributed evenly across each FL client for training (done through customization of the Flower framework). One epoch per client selection was chosen to limit overfitting on local data and keep each client from diverging excessively from the global model. The experimental setup also consists of a batch size of sixteen and a learning rate of 0.001, working best with the Adam optimizer. The researchers conducted five rounds of FL, which worked well enough with the project dataset. More rounds are often needed for more extensive or more diverse datasets. Finally, restricting the experiment to four clients kept the setup manageable despite real-world deployments frequently involving many more clients. These parameters were chosen through intense simulations.

3.5. Proposed DataWeightedFed Approach

3.5.1. Hypothesis

The proposed DataWeightedFed approach with dynamically weighted FedAvg (wFedAvg) and k client selection training will improve global model accuracy while maintaining efficiency compared to standard centralized learning.

3.5.2. Proof

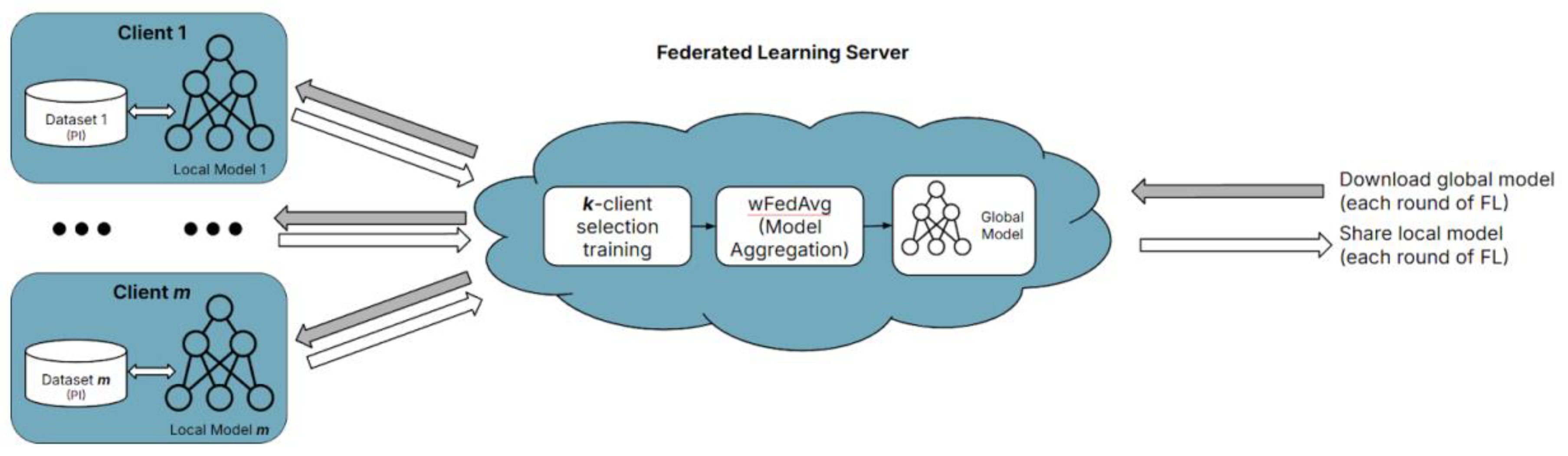

The study proposes a novel collaborative FL architecture found in

Figure 5.

As shown in

Figure 5, the architecture contains an arbitrary

m number of clients. Each client houses their dataset (private, PI data compiled independently) and a local model. All models used in this study leverage TL with the VGG-19 model. The novelty of this study’s proposed architecture comprises two main components:

k-client selection training and the

wFedAvg (custom, dynamically weighted

FedAvg) client model aggregation method.

In any FL environment, the clients are collectively working together to train a global model. This means all clients have the same end goal, with all clients contributing their datasets, consisting of data from the same feature space. This study’s feature space comprises fundus images; however, each client has different data samples, making each client’s data considered non-IID. The proposed architecture can increase training speed and reduce the required computations by leveraging this. This is especially beneficial because FL environments primarily involve many clients, so many resources must be expended, and many resources must be spent to train these models collectively—before they aggregate together for the global model.

Therefore, this study randomly selected k number of clients to train locally for n epochs each round of FL (n and k are hyperparameters, where n=1 and k=2). This can be done because the data from each client is from the same feature space, so model training is consistent and comparable across all clients. Thus, the aggregated global model will also capture shared patterns across all clients because the k number of clients is selected randomly. The principle be translated into a formula representation.

Let Gt be a global model at round t, C a total number of clients, k – the number of randomly selected clients per round, n - the number of local training epochs per round, Di - the dataset of client i, wi(t) - the local model weights for client i at round t, ηi - the contribution weight of client i to the aggregation (based on dataset size).

The FL process for each round t can be expressed as:

- a)

Client Selection:

where

St is the subset of

k randomly selected clients for round

t.

- b)

Local Training for Selected Clients: each selected client

i ∈

St updates its local model by minimizing its local loss function over

n epochs:

where

Train is the local training procedure using the client’s data

Di.

- c)

Global Aggregation: the global model

Gt is updated as a weighted average of the local models:

where

ηi = ∣

Di∣ / (∑∣

Dj∣) with

j∈

St, the aggregation is proportional to dataset sizes.

In the proposed simplified example, since n=1 and k=2, each client trains locally for only one epoch; two clients are randomly selected per round, and consistent feature space guarantees efficient FL training and aggregation.

The most popular model aggregation method in the FL space is

FedAvg [

29].

FedAvg takes the average of local model weights and updates the global model with that average for each round of FL. However,

FedAvg is prone to drawbacks, especially if there is data distribution heterogeneity between devices (eg. different size datasets per client). In that case,

FedAvg won’t consider the amount of data and won’t correctly “weigh” each client’s effect on the global model based on their data distribution proportions.

Therefore, this study aimed to address FedAvg’s drawbacks by developing and using a custom, dynamically weighted FedAvg aggregation method (wFedAvg). wFedAvg improves FedAvg by calculating the average using weights based on the dataset size of each client and will dynamically update as more clients are added. Doing so will improve the overall accuracy of the trained models because wFedAvg will provide a more accurate representation of the client models (collectively) so that the global model can be updated. This can help offset the accuracy loss due to FL and differential privacy. This wFedAvg aggregation method was created through customizations with the Flower framework when designing the FL setup for this study.

The principle is encapsulated in the formulas.

a) FedAvg Formula:

FedAvg updates the global model by averaging the local model weights of selected clients without considering dataset size:

Where Gt is a global model at round t, k is the number of selected clients (∣St∣=k),

St is a subset of clients chosen at round t, wi(t) is a local model weight for client i

at round t.

b) Weighted FedAvg (wFedAvg) Formula:

To address

FedAvg’s drawbacks,

wFedAvg incorporates weights proportional to the dataset sizes of clients. The global model is updated as a weighted average (3), and the weights are normalized such that

Where Snew represents newly added clients in subsequent rounds.

Regardless of dataset size, FedAvg assigns equal weight to all selected clients. wFedAvg assigns a higher weight to clients with larger datasets, ensuring their contributions are proportional to the data they provide. As more clients join the FL system, the weight calculation dynamically updates to account for the new clients’ dataset sizes. The aggregation remains according to (5). This dynamically weighted approach improves model accuracy by better reflecting the data distribution among clients in the global model updates.

4. Results

To evaluate the performance of the proposed FL architecture, a singular, centralized VGG-19 model was trained for comparison purposes. This model was trained on all the data from all FL clients pooled together, resulting in a singular dataset. It used the same applicable hyperparameters as the models used in the FL architecture (1 training epoch, batch size of 16, learning rate of 0.001, etc.). This model was used to compare the effectiveness of the proposed FL architecture to standard centralized learning, as shown below.

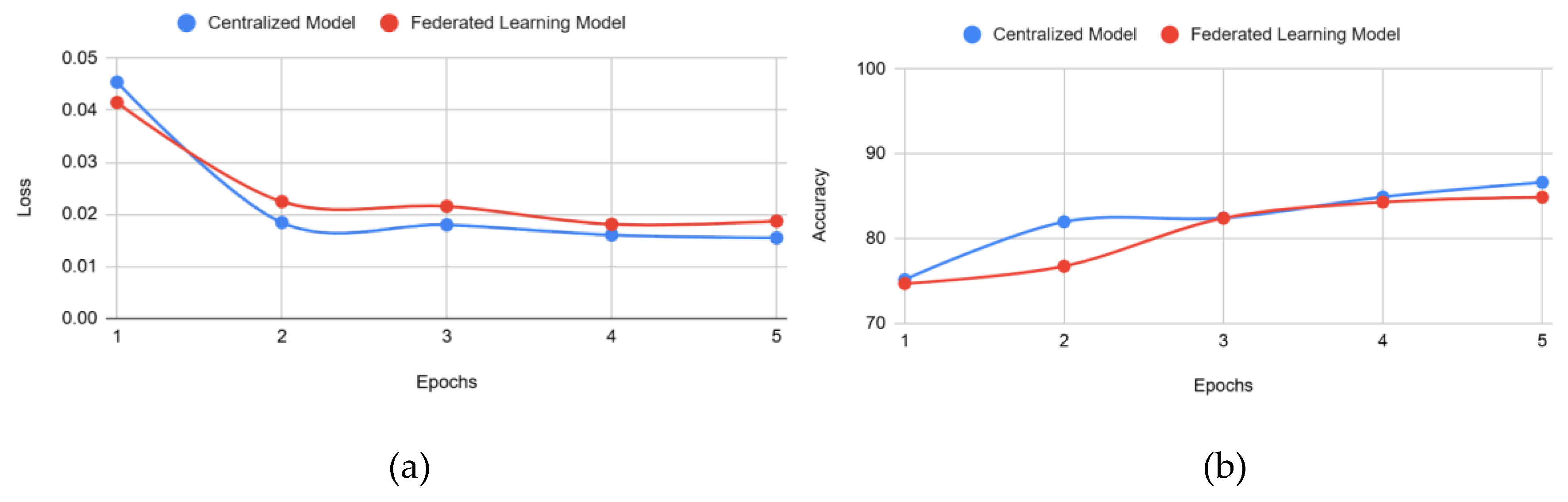

Figure 6 represents the training loss and accuracy in both approaches.

Figure 6 shows the convergence of the FL model compared to centralized learning. Both accuracy and loss reached similar values in the same training time. This means the FL architecture had little to no disadvantage in model performance and training efficiency compared to the centralized model counterpart. It is important to note that although the FL architecture uses both rounds of FL and epochs to conduct client training, rounds, and epochs are almost synonymous for this study. This is because FL architecture had clients trained for 1 epoch in each round of FL, and there were only 5 rounds of FL. Since each client is only trained for 1 epoch and the k-clients selected are all

trained in parallel, the FL simulation theoretically trains the same amount as the centralized models. This means that the amount of training completed on the FL global model is equivalent to the training conducted on the centralized model, which trained for 5 epochs while leveraging centralized learning with just a singular dataset.

Accuracy and accuracy reduction comparison between existing centralized models and this study’s proposed FL architecture approach can be seen in

Table 1.

As can be seen from

Table 1, the results outperform [

16,

17] findings and slightly below [

18], which uses significantly less complex ML models MobileNetV1 & MobileNetV2, suitable only for a tiny dataset. As a result, the proposed novel FL architecture is effective. As shown in Figure 8 above, the accuracy reduction was minuscule compared to regular centralized learning models/architectures. The proposed FL approach of VGG-19 TL with

wFedAvg aggregator had only an average 1.85% accuracy decrease, compared to the conventional FL average of up to about a 55% accuracy decrease. It is important to note that although the FL architecture uses both rounds of FL and epochs to conduct client training, they are almost synonymous with this study. This is because FL architecture had clients trained for 1 epoch in each round of FL, and there were only 5 rounds of FL. Since each client is only trained for 1 epoch & the k-clients selected are all trained

in parallel, the FL simulation theoretically trains the same amount as the centralized models. This means that the amount of training completed on the FL global model is equivalent to the training conducted on the centralized model, which trained for 5 epochs while leveraging centralized learning with just a singular dataset. The architecture can dynamically scale to accommodate many clients and a bigger dataset.

Thus, the hypothesis is validated. The proposed FL architecture achieves competitive accuracy with centralized learning while preserving client data privacy and computational efficiency.

5. Discussion

During the study, the researchers addressed all research questions stated in the beginning. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed FL architecture.

(R1) The proposed FL architecture leverages collaborative learning across multiple clients while preserving data privacy and addressing the sensitive nature of medical datasets like fundus images. By utilizing the VGG-19 model with TL the architecture ensures high compatibility with the feature space common across clients. The k-client selection method further enhances efficiency by enabling only a subset of clients (randomly selected k=2) to train locally per round, reducing resource requirements while maintaining the consistency of global model updates. This approach ensures the collaborative training process captures shared patterns across all clients, even with non-IID data distributions. The architecture thus effectively demonstrates FL’s potential for enabling secure and efficient collaboration in eye healthcare without requiring data centralization.

(R2) The results indicate that the proposed FL architecture achieves a high level of accuracy comparable to centralized learning. The

DataWeightedFed approach achieved 84.88% accuracy, just a 1.85% reduction compared to the centralized VGG-19 model’s accuracy of 86.63%. Conventional FL approaches often lose up to 55% accuracy due to non-IID data and insufficient aggregation strategies. By incorporating the dynamically weighted

wFedAvg method, the proposed

DataWeightedFed approach minimizes this loss by accounting for dataset size in aggregation, improving the representation of client models in the global update. The convergence of the training loss and accuracy for both FL and CL models (

Figure 6) further highlights that the FL architecture maintains competitive performance while adhering to FL principles of privacy and decentralization.

(R3) The computational efficiency of the proposed FL architecture is a direct result of the following design choices: k-client selection method ensures that only k=2 clients are trained per round, reducing computational overhead while allowing clients to train in parallel. Each client trains for just one epoch per round (n=1), and the global model is updated after every round. This design makes rounds and epochs nearly synonymous, ensuring that the FL training time matches the centralized training time. For example, the FL architecture completed 5 training rounds with k-client selection, equivalent to 5 epochs of centralized training. The architecture dynamically updates the weights (ηi) in the wFedAvg aggregation as new clients join the system, making it scalable to larger datasets and more clients without sacrificing speed or accuracy. These features demonstrate that the computational load is effectively distributed across clients while maintaining an overall training speed equivalent to centralized models.

6. Conclusions

Due to the many privacy restrictions and regulations regarding sharing PI/patient data, obtaining enough medical data for sufficient ML model training is often challenging. This research addressed these difficulties, especially in the eye healthcare/ophthalmology space, by proposing a novel FL architecture explicitly designed to allow for private, collaborative ML model training within this field. In doing so, this research leveraged TL with the VGG-19 model and horizontal FL training. Additionally, this study developed and applied k-client selection training and a custom, dynamically weighted FedAvg model aggregation method (wFedAvg).

Overall, this study’s proposed FL architecture keeps data private, yet is scalable and ready to be deployed in an industrial/commercial eye healthcare environment. Firstly, although only 4 clients were used in this study, this architecture was designed to take advantage of FL’s ability to create collaborative models securely using an arbitrary number of clients (m). Secondly, the novel wFedAvg aggregation algorithm was designed to be scalable, as although it takes a weighted average of the client’s local models, it will dynamically adjust the weights as more clients are added on the fly to the FL architecture. Lastly, differential privacy was utilized throughout the architecture to ensure patient PI stays secure. By adding noise, this architecture prevents outside attackers from tracing published model weight updates back to the patients & their PI.

Compared to centralized learning models, this study’s proposed architecture maintained most of the model accuracy and model training time efficiency while ensuring all data remains private. As shown in Figure 8, the proposed DataWeightedFed approach with wFedAvg aggregation had only an average 1.85% accuracy decrease, compared to the conventional FL average of up to about a 55% accuracy decrease. This meant that this study’s proposed architecture improved how FL can be efficiently applied to the eye healthcare space and allowed for collaborative ML model training.

7. Study Limitations and Future Work

Even though this study’s proposed FL architecture, methods, and results look optimistic, there is still room for improvement. Currently, this study is only used by 4 clients due to technological and resource restrictions. However, when using FL in a real-life healthcare setting, the number of clients will rise dramatically to hundreds or even thousands, so testing this proposed architecture and evaluating the results when involving more clients will be essential. Although this study used a novel FedAvg modification with dynamically adjusted weights, many other robust global model aggregation methods may also be effective when dealing with fundus disease image data. These other aggregation methods may reduce the accuracy trade-off that comes with privacy-preserving FL and differential privacy, so in the future, this study aims to employ other methods to evaluate if the architecture performance will increase. Finally, although this study focused on applying FL to the eye healthcare space, the study’s proposed architecture could be flexible enough to be applied to any domain where data privacy is of utmost concern. Therefore, in the future, we aim to evaluate this study’s proposed architecture’s performance within other fields and domains.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The code will be released with the study and available in a public GitHub repo.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, R.J.; methodology, R.J.; software, R.J.; validation, Y.K., and D.K.; formal analysis, R.J.; investigation, R.J.; resources, R.J.; data curation, R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J. and Y.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.K. and D.K.; visualization, R.J.; supervision, Y.K. and D.K.; project administration, Y.K. and D.K.; funding, Y.K.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMD |

Age-related Macular Degeneration |

| CLAHE |

Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization |

| CNN(s) |

convolutional neural network(s) |

| FL |

Federated Learning |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| HIPAA |

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| non-IID |

non-Independent and Identically Distributed |

| ODIR |

Ocular Disease Intelligent Recognition |

| PI |

Personal Information |

| PIPEDA |

Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act |

| TL |

Transfer Learning |

References

- Alowais, S. A., Alghamdi, S. S., Alsuhebany, N., Alqahtani, T., Alshaya, A. I., Almohareb, S. N., ... & Albekairy, A. M. (2023). Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC medical education, 23(1), 689. [CrossRef]

- Hemn Barzan Abdalla, Kumar Y, Marchena J, Guzman S, Gheisari M, Awlla A, Cheraghy M. The Future of AI in the Face of Data Scarcity. Submitted to CMC-Computers, Materials & Continua. Manuscript ID: 63551. ISSN: 1546-2226.

- Drainakis, G., Pantazopoulos, P., Katsaros, K. V., Sourlas, V., Amditis, A., & Kaklamani, D. I. (2023). From centralized to Federated Learning: Exploring performance and end-to-end resource consumption. Computer Networks, 225, 109657. [CrossRef]

- Adjerid, I., Acquisti, A., Telang, R., Padman, R., & Adler-Milstein, J. (2016). The impact of privacy regulation and technology incentives: The case of health information exchanges. Management Science, 62(4), 1042-1063. [CrossRef]

- Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html (accessed on September 9, 2024).

- General Data Protection Regulation. Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/ (accessed on September 9, 2024).

- Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/P-8.6/ (accessed on September 9, 2024).

- Nugroho, K. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Federated and Centralized Learning Systems in Predicting Cellular Downlink Throughput Using CNN. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- AbdulRahman, S., Tout, H., Ould-Slimane, H., Mourad, A., Talhi, C., & Guizani, M. (2020). A survey on federated learning: The journey from centralized to distributed on-site learning and beyond. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 8(7), 5476-5497. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. C., Goetz, J., Sen, S., & Tewari, A. (2021). Learning from others without sacrificing privacy: simulation comparing centralized and federated machine learning on mobile health data. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(3), e23728. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Wang, H., & Ma, M. (2024). Federated Learning with Efficient Aggregation via Markov Decision Process in Edge Networks. Mathematics, 12(6), 920. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Gao, L., He, C., Zhang, M., Krishnamachari, B., & Avestimehr, A. S. (2022). Federated learning for the internet of things: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Internet of Things Magazine, 5(1), 24-29. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, A., Attoh-Okine, N., & Sakurai, T. Risk and advantages of federated learning for health care data collaboration. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertainty Eng. Syst. Part A: Civil Eng. 6, 04020031 (2020). [CrossRef]

- El Ouadrhiri, A., & Abdelhadi, A. (2022). Differential privacy for deep and federated learning: A survey. IEEE access, 10, 22359-22380. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Li, M., Lai, L., Suda, N., Civin, D., & Chandra, V. (2018). Federated learning with non-iid data. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.00582.

- Velpula, V. K., & Sharma, L. D. (2023). Multi-stage glaucoma classification using pre-trained convolutional neural networks and voting-based classifier fusion. Frontiers in Physiology, 14, 1175881. [CrossRef]

- Sigit, R., Triyana, E., & Rochmad, M. (2019, October). Cataract detection using single layer perceptron based on smartphone. In 2019 3rd International Conference on Informatics and Computational Sciences (ICICoS) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Saqib, S. M., Iqbal, M., Asghar, M. Z., Mazhar, T., Almogren, A., Rehman, A. U., & Hamam, H. (2024). Cataract and glaucoma detection based on Transfer Learning using MobileNet. Heliyon, 10(17). [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Lv, N., Guo, Y., & Li, Y. (2024). Recent advances on federated learning: A systematic survey. Neurocomputing, 128019. [CrossRef]

- Wen, J., Zhang, Z., Lan, Y., Cui, Z., Cai, J., & Zhang, W. (2023). A survey on federated learning: challenges and applications. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics, 14(2), 513-535. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M., Reza, M. T., Kaosar, M., & Parvez, M. Z. (2023). Effectiveness of federated learning and CNN ensemble architectures for identifying brain tumors using MRI images. Neural Processing Letters, 55(4), 3779-3809. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Milletarì, F., Xu, D., Rieke, N., Hancox, J., Zhu, W., ... & Feng, A. (2019). Privacy-preserving federated brain tumour segmentation. In Machine Learning in Medical Imaging: 10th International Workshop, MLMI 2019, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2019, Shenzhen, China, October 13, 2019, Proceedings 10 (pp. 133-141). Springer International Publishing.

- Li, N., Li, T., Hu, C., Wang, K., & Kang, H. (2021). A benchmark of ocular disease intelligent recognition: One shot for multi-disease detection. In Benchmarking, Measuring, and Optimizing: Third BenchCouncil International Symposium, Bench 2020, Virtual Event, November 15–16, 2020, Revised Selected Papers 3 (pp. 177-193). Springer International Publishing.

- Hosna, A., Merry, E., Gyalmo, J., Alom, Z., Aung, Z., & Azim, M. A. (2022). Transfer learning: a friendly introduction. Journal of Big Data, 9(1), 102. [CrossRef]

- Shijie, J., Ping, W., Peiyi, J., & Siping, H. (2017, October). Research on data augmentation for image classification based on convolution neural networks. In 2017 Chinese automation congress (CAC) (pp. 4165-4170). IEEE.

- Hitam, M. S., Awalludin, E. A., Yussof, W. N. J. H. W., & Bachok, Z. (2013, January). Mixture contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization for underwater image enhancement. In 2013 International conference on computer applications technology (ICCAT) (pp. 1-5). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Hosna, A., Merry, E., Gyalmo, J., Alom, Z., Aung, Z., & Azim, M. A. (2022). Transfer learning: a friendly introduction. Journal of Big Data, 9(1), 102. [CrossRef]

- Karen, S. (2014). Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1409.1556.

- Mansour, A. B., Carenini, G., Duplessis, A., & Naccache, D. (2022, December). Federated learning aggregation: New robust algorithms with guarantees. In 2022 21st IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA) (pp. 721-726). IEEE.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).