Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Contribution and Paper Organization

3. Literature Review

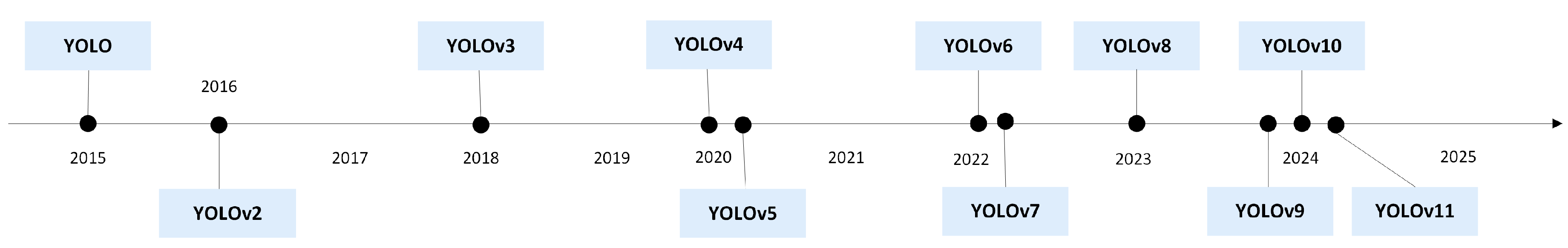

4. Yolo Background

5. Methodology

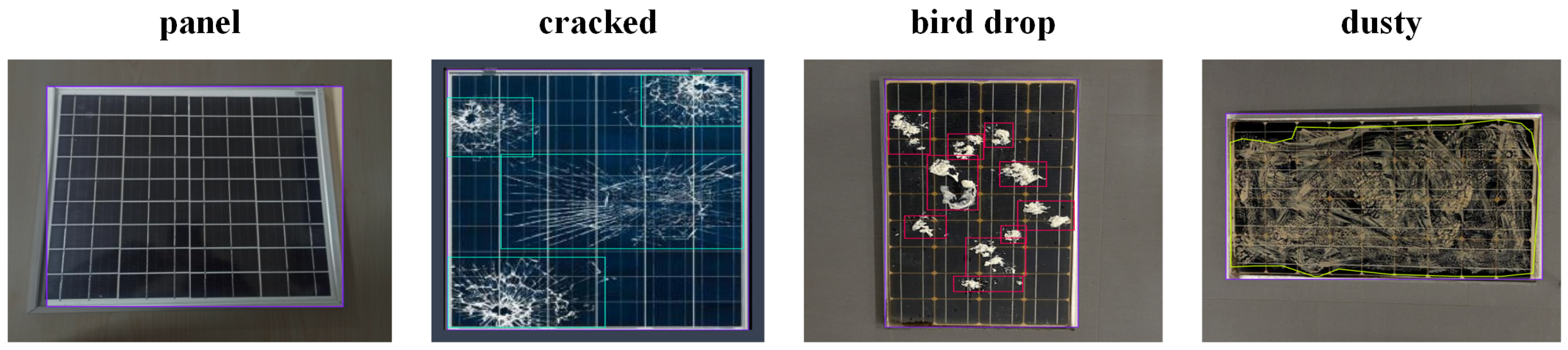

5.1. Dataset

5.2. Model Training

5.3. Evaluation Metrics

6. Results and Discussion

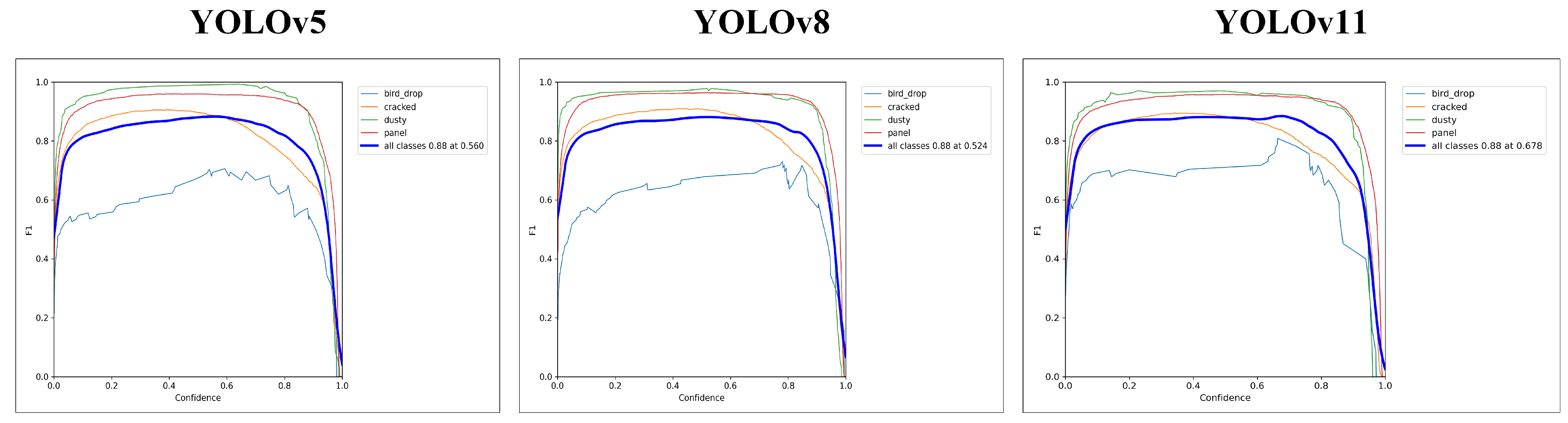

6.1. Detection Accuracy Assessment: Precision, Recall, and F1-Confidence Analysis

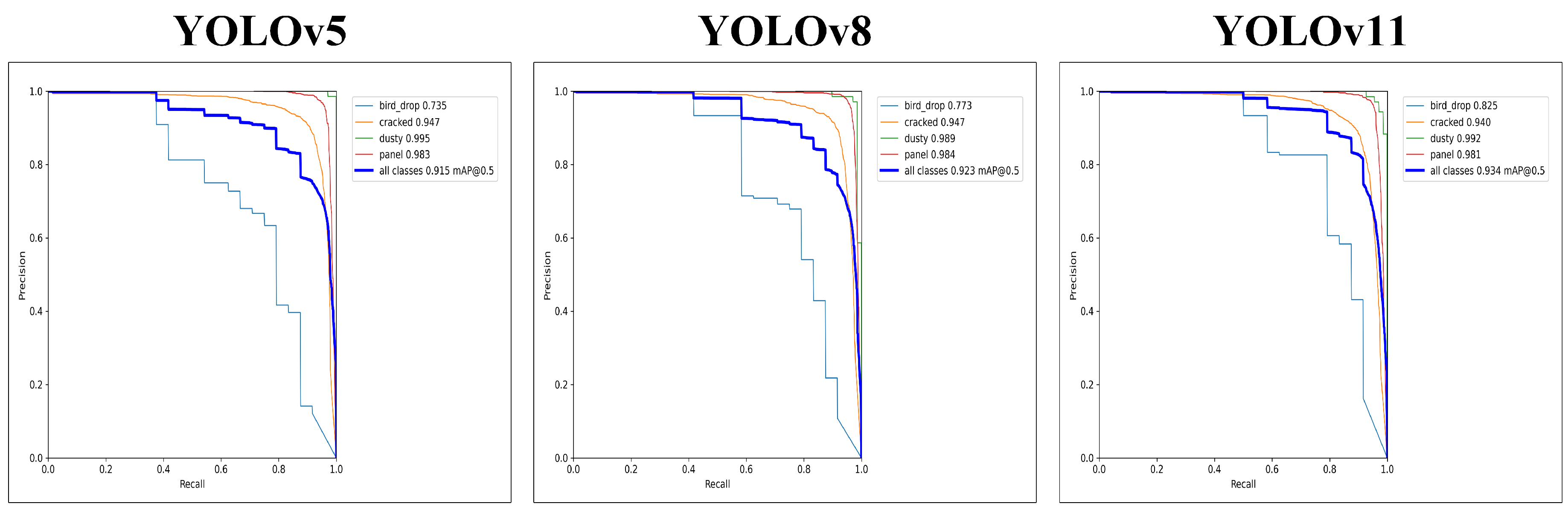

6.2. Detection Consistency Evaluation: mAP at IoU 0.50 and Precision-Recall Analysis

6.3. Computational Efficiency Analysis: Image Processing Speed

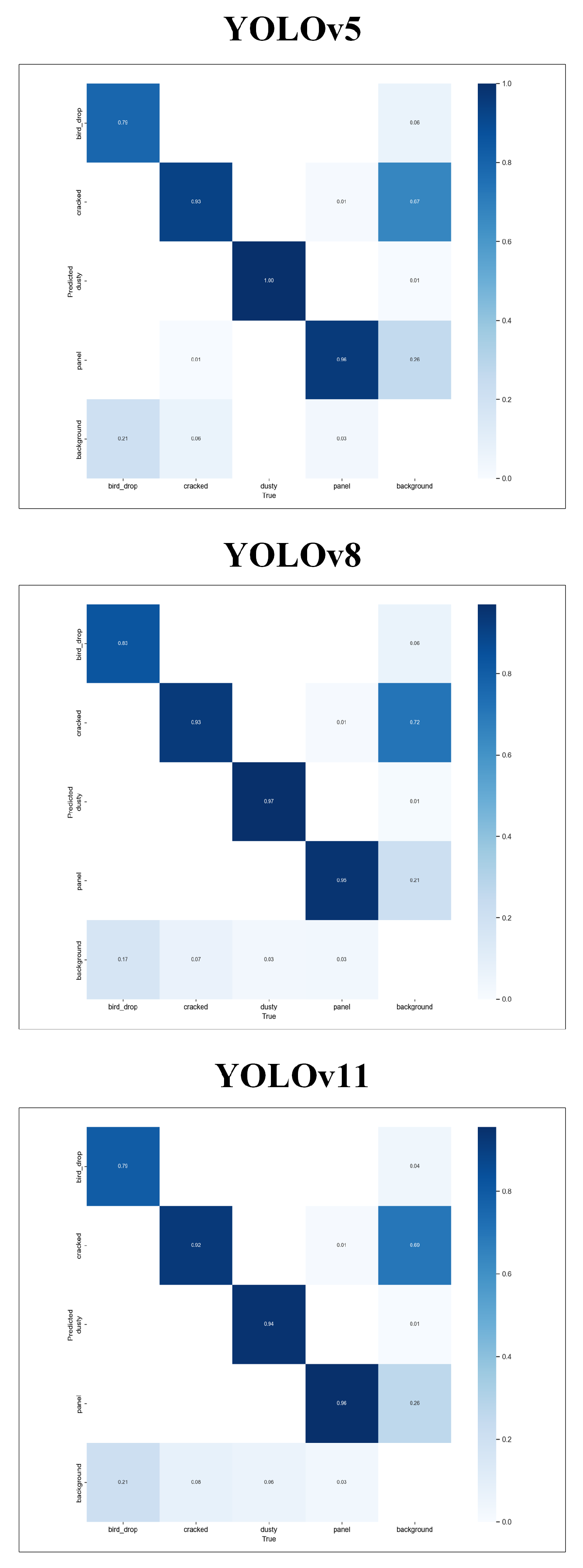

6.4. Error Patterns and Classification Performance: Confusion Matrix Analysis

7. Future Directions

- Dataset Expansion and Diversity:Expanding the dataset to address the underrepresentation of rare defect types, such as bird drops, is crucial for improving model robustness. Additionally, incorporating images captured under diverse environmental conditions, such as varying lighting, weather, and panel orientations, could enhance the adaptability of the models to real-world scenarios. Synthetic data augmentation techniques, such as those based on GANs or other advanced generative models, could help mitigate data imbalances by simulating rare or difficult-to-capture defects.

- Architectural Optimizations: Advancements in model architecture could significantly improve computational efficiency and detection accuracy. Lightweight model designs, achieved through techniques such as pruning, quantization, or knowledge distillation, would reduce computational complexity, enabling deployment on resource-constrained devices. Incorporating attention mechanisms like SE blocks or transformer-based enhancements could improve the models’ ability to detect subtle or complex defects. Additionally, hybrid approaches that combine YOLO’s strengths with anchor-free methods or segmentation frameworks may provide better precision and localization accuracy.

- Integration with Multi-Sensor Systems: Multi-sensor integration offers an avenue for improving defect detection performance. Combining visible light images with thermal or infrared imagery can help identify defects, such as hotspots or micro-cracks, that are not evident in standard RGB imagery. Similarly, leveraging depth information from RGB-D sensors or stereo imaging could aid in capturing three-dimensional structural details of solar panels, further enhancing detection capabilities.

- Real-Time Deployment and Automation: Real-time deployment of YOLO-based models in automated inspection systems holds immense potential for improving maintenance workflows. For instance, integrating these models into drone-based platforms can facilitate large-scale, autonomous solar panel inspections. Furthermore, optimizing models for edge devices, such as IoT systems or embedded processors, could enable localized data processing, reducing reliance on centralized servers and improving operational efficiency. Developing intelligent feedback mechanisms to provide actionable insights, such as severity ratings or repair recommendations, would further enhance their utility in real-world applications.

- Cross-Domain Applications: The methodologies and insights from this study can be extended to other domains [51]. In industrial defect detection, YOLO-based models could be adapted for tasks such as quality control and structural health monitoring. In agriculture, they could be employed for precision farming tasks, including pest detection and crop health assessment [47]. Additionally, integrating these models into smart grid systems could optimize predictive maintenance and improve energy efficiency across renewable energy infrastructure [76].

8. Conclusion

References

- Hernández-Callejo, L.; Gallardo-Saavedra, S.; Alonso-Gómez, V. A review of photovoltaic systems: Design, operation and maintenance. Solar Energy 2019, 188, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, T.M.; Mahdy, A.M.; Abass, K.I.; Chaichan, M.T.; Kazem, H.A. Impact of dust ingredient on photovoltaic performance: An experimental study. Solar Energy 2020, 195, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zereg, K.; Gama, A.; Aksas, M.; Rathore, N.; Yettou, F.; Panwar, N.L. Dust impact on concentrated solar power: A review. Environmental Engineering Research 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Sharma, M.; Pachauri, R.K.; Babu, K.D. Comprehensive review on effect of dust on solar photovoltaic system and mitigation techniques. Solar Energy 2019, 191, 596–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijjawi, U.; Lakshminarayana, S.; Xu, T.; Fierro, G.P.M.; Rahman, M. A review of automated solar photovoltaic defect detection systems: Approaches, challenges, and future orientations. Solar Energy 2023, 266, 112186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeliski, R. Computer vision: algorithms and applications; Springer Nature, 2022.

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sahoo, D.; Hoi, S.C. Recent advances in deep learning for object detection. Neurocomputing 2020, 396, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics Detection Tasks Documentation. https://docs.ultralytics.com/tasks/detect/. Accessed: 2024-12-31.

- Hussain, M.; Khanam, R. In-depth review of yolov1 to yolov10 variants for enhanced photovoltaic defect detection. In Proceedings of the Solar. MDPI, Vol. 4; 2024; pp. 351–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, P.; Bahadir Kocer, B.; Kovac, M. Drone-Based Solar Cell Inspection With Autonomous Deep Learning. Infrastructure Robotics: Methodologies, Robotic Systems and Applications 2024, pp. 337–365.

- Ultralytics. Ultralytics Official Website. https://www.ultralytics.com/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-01-01.

- Prajapati, N.; Aiyar, R.; Raj, A.; Paraye, M. Detection and Identification of faults in a PV Module using CNN based Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tajwar, T.; Mobin, O.H.; Khan, F.R.; Hossain, S.F.; Islam, M.; Rahman, M.M. Infrared thermography based hotspot detection of photovoltaic module using YOLO. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 12th Energy Conversion Congress &, 2021, Exposition-Asia (ECCE-Asia). IEEE; pp. 1542–1547.

- Greco, A.; Pironti, C.; Saggese, A.; Vento, M.; Vigilante, V. A.; Pironti, C.; Saggese, A.; Vento, M.; Vigilante, V. A deep learning based approach for detecting panels in photovoltaic plants. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Applications of Intelligent Systems, 2020, pp.; Vento, M.

- Shinde, S.; Kothari, A.; Gupta, V. YOLO based human action recognition and localization. Procedia computer science 2018, 133, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletti, V.; Greco, A.; Saggese, A.; Vento, M. An intelligent flying system for automatic detection of faults in photovoltaic plants. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2020, 11, 2027–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, F.; Mo, W.; Tao, P.; Shen, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, F. Novel Cloud-Edge Collaborative Detection Technique for Detecting Defects in PV Components, Based on Transfer Learning. Energies 2022, 15, 7924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, A.; Betti, A.; Fontanelli, G.; Michelozzi, B. A multi-stage model based on YOLOv3 for defect detection in PV panels based on IR and visible imaging by unmanned aerial vehicle. Renewable energy 2022, 193, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imenes, A.G.; Noori, N.S.; Uthaug, O.A.N.; Kröni, R.; Bianchi, F.; Belbachir, N. A deep learning approach for automated fault detection on solar modules using image composites. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 48th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC). IEEE; 2021; pp. 1925–1930. [Google Scholar]

- Teke, M.; Başeski, E.; Ok, A.Ö.; Yüksel, B.; Şenaras, Ç. Multi-spectral false color shadow detection. In Proceedings of the ISPRS Conference on Photogrammetric Image Analysis. Springer; 2011; pp. 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J.T.; Rajveer, G. Drone-based solar panel inspection with 5G and AI Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Applied System Innovation (ICASI). IEEE; 2022; pp. 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Z.; Xu, S.; Wang, L.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. Defect object detection algorithm for electroluminescence image defects of photovoltaic modules based on deep learning. Energy Science & Engineering 2022, 10, 800–813. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T. Photovoltaic panel defect detection based on ghost convolution with BottleneckCSP and tiny target prediction head incorporating YOLOv5. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.00886 2023.

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. arXiv 2015. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1504.08083 2015.

- Hong, F.; Song, J.; Meng, H.; Wang, R.; Fang, F.; Zhang, G. A novel framework on intelligent detection for module defects of PV plant combining the visible and infrared images. Solar Energy 2022, 236, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, L. Solar cell surface defect detection based on improved YOLO v5. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 80804–80815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Ma, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, G. Lightweight hot-spot fault detection model of photovoltaic panels in UAV remote-sensing image. Sensors 2022, 22, 4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zou, P.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, Z. Inspection and classification system of photovoltaic module defects based on UAV and thermal imaging. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Power and Renewable Energy (ICPRE). IEEE; 2022; pp. 905–909. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, F. A Photovoltaic Panel Defect Detection Method Based on the Improved Yolov7. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Mechatronics Technology and Intelligent Manufacturing (ICMTIM); 2024; pp. 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, Q.B.; Nguyen, T.T. A Novel Approach for PV Cell Fault Detection using YOLOv8 and Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 66th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS). IEEE; 2023; pp. 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks. ieee, 1995, Vol. 4, pp. 1942–1948.

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE international conference on evolutionary computation proceedings. IEEE world congress on computational intelligence (Cat. No. 98TH8360). IEEE; 1998; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, P.; Saxena, V.; Raj, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, S.; et al. Fault Detection of the Solar Photovoltaic Modules Using YOLO Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Lang, Y.; Qian, Y. Enhanced photovoltaic panel defect detection via adaptive complementary fusion in YOLO-ACF. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 26425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, F.A.; Albraikan, A.A.; Soufiene, B.O.; Ali, O. Utilizing artificial intelligence and lotus effect in an emerging intelligent drone for persevering solar panel efficiency. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2022, 2022, 7741535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Hamid, M.Z.; Daud, K.; Soh, Z.H.C.; Osman, M.K.; Isa, I.S.; Jadin, M.S. YOLOv9-Based Hotspots Recognition in Solar Photovoltaic Panels: Integrating Image Processing Techniques for Targeted Region Identification. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 14th International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE). IEEE; 2024; pp. 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Droguett, S.E.; Sanchez, C.N. Solar Panel Detection on Satellite Images: From Faster R-CNN to YOLOv10.

- Faster, R. Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 9199, 2969239–2969250. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2025; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv preprint , arXiv:2405.14458 2024.

- Jiang, H.; Yao, L.; Lu, N.; Qin, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C. Multi-resolution dataset for photovoltaic panel segmentation from satellite and aerial imagery. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2021, 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terven, J.; Córdova-Esparza, D.M.; Romero-González, J.A. A comprehensive review of yolo architectures in computer vision: From yolov1 to yolov8 and yolo-nas. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yeh, I.; Liao, H. YOLOv9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. arXiv 2024. arXiv preprint , arXiv:2402.13616.

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016, Proceedings, Part I October 11–14. Springer, 2016, October 11–14; pp. 21–37.

- Redmon, J. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Badgujar, C.M.; Poulose, A.; Gan, H. Agricultural object detection with You Only Look Once (YOLO) Algorithm: A bibliometric and systematic literature review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 223, 109090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M.G.; Abdulkader, S.J.; Muneer, A.; Alqushaibi, A.; Sumiea, E.H.; Qureshi, R.; Al-Selwi, S.M.; Alhussian, H. A Comprehensive Systematic Review of YOLO for Medical Object Detection (2018 to 2023). IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DAZLEE, N.M.A.A.; Khalil, S.A.; RAHMAN, S.A.; Mutalib, S. Object detection for autonomous vehicles with sensor-based technology using yolo. International journal of intelligent systems and applications in engineering 2022, 10, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, A.; Vairavasundaram, S. Yolo-based object detection models: A review and its applications. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, pp. 1–40.

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M.; Hill, R.; Allen, P. A comprehensive review of convolutional neural networks for defect detection in industrial applications. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahara, H.; Yonekawa, H.; Fujii, T.; Sato, S. A lightweight YOLOv2: A binarized CNN with a parallel support vector regression for an FPGA. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on field-programmable gate arrays, 2018, pp.31–40.

- Li, R.; Yang, J. Improved YOLOv2 object detection model. In Proceedings of the 2018 6th international conference on multimedia computing and systems (ICMCS). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.J.; Kim, P.K.; Chung, Y.S.; Choi, D.H. Performance enhancement of YOLOv3 by adding prediction layers with spatial pyramid pooling for vehicle detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th IEEE international conference on advanced video and signal based surveillance (AVSS). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal, U.; Eslamiat, H. Comparing YOLOv3, YOLOv4 and YOLOv5 for autonomous landing spot detection in faulty UAVs. Sensors 2022, 22, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohod, N.; Agrawal, P.; Madaan, V. Yolov4 vs yolov5: Object detection on surveillance videos. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Network Technologies and Intelligent Computing. Springer; 2022; pp. 654–665. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, R.; Qureshi, R.; Flores-Calero, M.; Badgujar, C.; Nepal, U.; Poulose, A.; Zeno, P.; Bhanu Prakash Vaddevolu, U.; Yan, P.; Karkee, M.; et al. Yolov10 to its genesis: A decadal and comprehensive review of the you only look once series. Available at SSRN 4874098 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G. Ultralytics YOLOv5, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv preprint , arXiv:2209.02976 2022.

- Xu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Damo-yolo: A report on real-time object detection design. arXiv preprint , arXiv:2211.15444 2022.

- Roboflow. What is YOLOv8? https://blog.roboflow.com/what-is-yolov8/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-01-01.

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO11, 2024.

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv preprint , arXiv:2410.17725 2024.

- Susan. panel solar Dataset. https://universe.roboflow.com/susan-ifblr/panel-solar-bw945, 2024. visited on 2024-11-22.

- Roboflow. Roboflow Universe, 2024. Accessed: 2024-11-22.

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. What is YOLOv5: A deep look into the internal features of the popular object detector. arXiv preprint , arXiv:2407.20892 2024.

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLOv8, 2023.

- Padilla, R.; Netto, S.L.; Da Silva, E.A. A survey on performance metrics for object-detection algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2020 international conference on systems, signals and image processing (IWSSIP). IEEE; 2020; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, R.; Passos, W.L.; Dias, T.L.; Netto, S.L.; Da Silva, E.A. A comparative analysis of object detection metrics with a companion open-source toolkit. Electronics 2021, 10, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacouby, R.; Axman, D. Probabilistic extension of precision, recall, and f1 score for more thorough evaluation of classification models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first workshop on evaluation and comparison of NLP systems, 2020, pp.

- Henderson, P.; Ferrari, V. End-to-end training of object class detectors for mean average precision. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ACCV 2016: 13th Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Taipei, Taiwan, 2016, Revised Selected Papers, Part V 13. Springer, 2017, November 20-24; pp. 198–213.

- Jeong, H.J.; Park, K.S.; Ha, Y.G. Image preprocessing for efficient training of YOLO deep learning networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp). IEEE; 2018; pp. 635–637. [Google Scholar]

- Diwan, T.; Anirudh, G.; Tembhurne, J.V. Object detection using YOLO: Challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 9243–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, D.; Nagori, S.; Mathew, M.; Poddar, D. Yolo-pose: Enhancing yolo for multi person pose estimation using object keypoint similarity loss. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp.2637–2646.

- Zheng, C. Stack-YOLO: A friendly-hardware real-time object detection algorithm. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 62522–62534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihavuddin, A.; Rashid, M.R.A.; Maruf, M.H.; Hasan, M.A.; ul Haq, M.A.; Ashique, R.H.; Al Mansur, A. Image based surface damage detection of renewable energy installations using a unified deep learning approach. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 4566–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | YOLO Models | Contributions | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prajapati et al.[13] | YOLO | Detection and classification of faults in PV modules through thermal image analysis | 83.86% |

| Tahmid Tajwar et al.[14] | YOLOv3 | Hotspot detection through YOLO model with IRT imaging and improved detection accuracy with more diverse training data | - |

| Antonio Greco et al.[15] | YOLOv3 | Segmentation of modules in PV plants through plug-and-play deep learning-based YOLO method, eliminating the need for plant-dependent configurations | 95% |

| H. Wang et al. [18] | YOLOv3 | Proposed a cloud-edge collaborative technique and introduced an improved YOLO v3-tiny algorithm with a third prediction layer and a residual module. | 95.5% |

| A.D. Tommaso et al.[19] | YOLOv3 | Proposed a multi-stage architecture consisting of panel detector, defect detector and False Alarm for the detection of anomalies in images of PV panels | 68.5% |

| A.Gerd Imenes et al.[20] | YOLOv3 | Acquired multiwavelength composite images(thermal and visible) to improve fault detection and classification. | 75% |

| J.-T. Zou et al.[22] | YOLOv4 | AI-driven method using YOLOv4, CNN, and 5G drones for efficient PV module defect detection via thermal images. | 100% |

| Z. Meng et al.[23] | YOLOv4 | Introduced YOLO-PV, a YOLOv4-based framework optimized for EL image detection in PV modules, with innovative techniques like SPAN and data augmentation. | 94.55% |

| L.Li et al.[24] | YOLOv5 | Incorporated Ghost convolution, BottleneckCSP, and a tiny target prediction head in YOLOv5 for improved accuracy, speed, and detection of tiny defects | 97.8% |

| F. Hong et al.[26] | YOLOv5 | Introduced a intelligent end-to-end detection framework for module defects in PV power plants, integrating visible and infrared images | 95% |

| M.Zhang et al.[27] | YOLOv5 | Incorporated with deformable convolutional CSP module, ECA-Net attention mechanism, prediction head and improved network structure was proposed | 89.64% |

| Q. Zheng[28] | YOLOv5 | To improve both speed and accuracy, the feature extraction component of YOLOv5 is modified by integrating the Focus structure and the core unit of ShuffleNetV2, while simplifying the original feature fusion method. | 98.1% |

| X. Zhang et al.[29] | YOLOv5 | Acquired UAV and thermal camera for collecting thermal images of PV modules in power plants and detected areas with abnormal temperatures. | 80.88% |

| Liu et al. [30] | YOLOv7 | Enhanced YOLOv7 by integrating FReLU, PwConv, and SEAM attention | 97.7% |

| Q. B. Phan et al.[31] | YOLOv8 | Presented a novel fault detection method for photovoltaic cells by integrating YOLOv8 with Particle Swarm Optimization | 94% |

| P. Malik et al.[34] | YOLOv5 & YOLOv9 | Presented an advanced object detection approach using YOLOv5 through YOLOv9 models, with the GELANc model. | 70.4% |

| W. Pan et al.[35] | YOLOv5 | Proposed an Adaptive Complementary Fusion (ACF) module that combines spatial and channel information and integrates it into YOLOv5, resulting in the YOLO-ACF model. | 80% |

| MZ. Ab. Hamid et al. [37] | YOLOv9 | Presented a YOLOv9-based method integrated with advanced image processing techniques for precise hotspot detection and localization in solar PV panels | 96% |

| S.E. Droguett et al.[38] | YOLOv9 & YOLOv10 | Implemented Mask RCNN and CNN architecture in YOLO models to identify solar panels in satellite images | YOLOv9e = 74%, YOLOv10 = 73% |

| Dataset | Number of Images | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Training | 4546 | 70% |

| Validation | 1299 | 20% |

| Testing | 648 | 10% |

| Total | 6493 | 100% |

| Hyperparameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Epochs | 100 | Total number of complete passes through the training dataset. |

| Batch Size | 17 | Number of samples processed before the model updates its parameters. |

| Image Size (imgsz) | 640 | The dimension to which all input images are resized for training, balancing accuracy and computational cost. |

| Initial Learning Rate (lr0) | 0.01 | The starting learning rate, determining the step size for optimizer updates. |

| Final Learning Rate (lrf) | 0.01 | The learning rate applied at the final epoch to ensure gradual convergence. |

| Warmup Epochs | 3.0 | Number of initial epochs during which the learning rate is incrementally increased to stabilize training. |

| Momentum | 0.937 | Hyperparameter for the optimizer that smoothens weight updates and accelerates convergence. |

| Weight Decay | 0.0005 | Regularization parameter added to reduce model overfitting. |

| Box Loss Gain (box) | 7.5 | Multiplier applied to the bounding box regression loss to prioritize localization accuracy. |

| Class Loss Gain (cls) | 0.5 | Multiplier applied to the classification loss to adjust its contribution during training. |

| Definition Loss Gain (dfl) | 1.5 | Scaling factor for the focal loss, enhancing the precision of bounding box predictions. |

| Class | Images | Instances | Model | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| all | 1299 | 3167 | YOLOv5m | 88.4 | 88.3 | 91.5 |

| YOLOv8 | 86.9 | 89.9 | 92.3 | |||

| YOLOv11m | 87.6 | 89.0 | 93.4 | |||

| bird_drop | 3 | 24 | YOLOv5m | 64.0 | 75.0 | 73.5 |

| YOLOv8 | 59.5 | 79.2 | 77.3 | |||

| YOLOv11m | 63.9 | 79 | 82.5 | |||

| cracked | 718 | 1796 | YOLOv5m | 94.1 | 83.9 | 94.7 |

| YOLOv8 | 93.3 | 87.9 | 94.7 | |||

| YOLOv11m | 91.7 | 86.6 | 94.0 | |||

| dusty | 27 | 68 | YOLOv5m | 98.1 | 100.0 | 99.5 |

| YOLOv8 | 97.1 | 97.5 | 98.9 | |||

| YOLOv11m | 98.2 | 95.6 | 99.2 | |||

| panel | 1055 | 1279 | YOLOv5m | 97.5 | 94.1 | 98.3 |

| YOLOv8 | 97.8 | 94.9 | 98.4 | |||

| YOLOv11m | 96.6 | 94.7 | 98.1 |

| Model | Layers | Parameters | GFLOPs | Speed (ms/image) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5m | 248 | 25,047,532 | 64.0 | Preprocess: 0.3 |

| Inference: 7.1 | ||||

| Loss: 0.0 | ||||

| Postprocess: 1.0 | ||||

| YOLOv8 | 218 | 25,842,076 | 78.7 | Preprocess: 0.4 |

| Inference: 15.9 | ||||

| Loss: 0.0 | ||||

| Postprocess: 0.7 | ||||

| YOLOv11m | 303 | 20,033,116 | 67.7 | Preprocess: 0.3 |

| Inference: 7.7 | ||||

| Loss: 0.0 | ||||

| Postprocess: 0.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).