1. Introduction

1.1. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) is defined as an idiopathic, chronic and progressive interstitial pneumonia. It affects mainly adult males and it’s characterized by functional progression and chronic cough. An IPF diagnosis can be made if clinical parameters are compatible and if other causes are excluded. Without treatment, the mean life expectancy is between 3 and 5 years [

1,

2]; unfortunately, the prognosis is unpredictable, although the introduction of antifibrotic drugs has led to a significant reduction in mortality [

3,

4]. IPF is characterized by a UIP (Usual Interstitial Pneumonia) pattern both regarding radiology and histopathology [

5]. IPF incidence in Europe and North America vary between 2,8 -18 cases per 100.000/year [

1,

6]; in Italy, incidence is approximately around 9,3 cases per 100.000 and prevalence around 31,6 per 100.000 [

7]. The etiopathogenesis is not fully defined yet: in the past, IPF was considered a chronic inflammatory disease with a gradual progression toward fibrosis. Nowadays, this theory has been reformulated due to studies suggesting that inflammation does not play a fundamental role and epithelial damage in the absence of ongoing inflammation is sufficient to stimulate fibrosis development [

8]. In healthy lungs, type 1 alveolar epithelial cells (AEC1) are the primary mediators of gas exchange. Type 2 alveolar epithelial cells (AEC2) produce surfactant and serve as primary progenitors for damaged AEC1 cells. In IPF patients, there are higher levels of apoptosis, senescence, and abnormal differentiation of AEC2 cells. These facts, paired with a combination of extrinsic and intrinsic factors (including aging, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, telomere shortening) lead to the inability of AEC2 cells to repair the damaged epithelium [

9]. According to the most widely accepted hypothesis, this lung disease is a result of repeated stimuli acting on AEC2 cells, leading to aberrant communication between epithelial cells and fibroblasts. This miscommunication leads to abnormal extracellular matrix deposition in so-called fibroblastic foci (aggregates of mesenchymal cells within a myxoid matrix) and interstitial remodelling [

10].

Clinically, IPF manifests with nonspecific symptoms; the most important are dyspnoea (initially on exercise-related and then resting) and non-productive cough. Chest physical examination is characterized by inspiratory “velcro-like” crackles. Most patients experience a slow and progressive worsening of dyspnoea and respiratory function, some patients remain stable, while others develop a rapid progression of the disease [

5,

11,

12]. The 2018 ATS guidelines [

5] made a strong recommendation on the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in diagnosing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). High-resolution chest CT (HRCT) is performed, and in selected cases, surgical lung biopsy (SLB) or transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLC). If a radiologic diagnosis of UIP (definite or probable pattern) is made with HRCT in a compatible clinical context, it is already possible to diagnose IPF without the need for a lung biopsy [

13].

About IPF treatment, since June 2013, AIFA has approved the distribution of Pirfenidone by the National Health System at a dose of 2403 mg/day for patients with mild-to-moderate IPF. The most frequent side effects include gastrointestinal problems (nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhoea), weight loss, increased transaminase levels, and photosensitivity. Nintedanib, on the other hand, was approved by AIFA in Italy in 2016. Both drugs have shown a slowing in disease progression and, in the case of Nintedanib, a reduction in exacerbations as well. According to AIFA criteria, both drugs are prescribed based on functional characteristics: for both, FVC values must be greater than 50%; DLCO must exceed 35% for Pirfenidone and 30% for Nintedanib. The choice of drug should therefore be weighed according to the level of respiratory impairment as well as patient compliance, comorbidities and associated therapies. Despite the approval of these drugs, lung transplantation remains the only therapeutic procedure that modifies the natural course of the disease [

14].

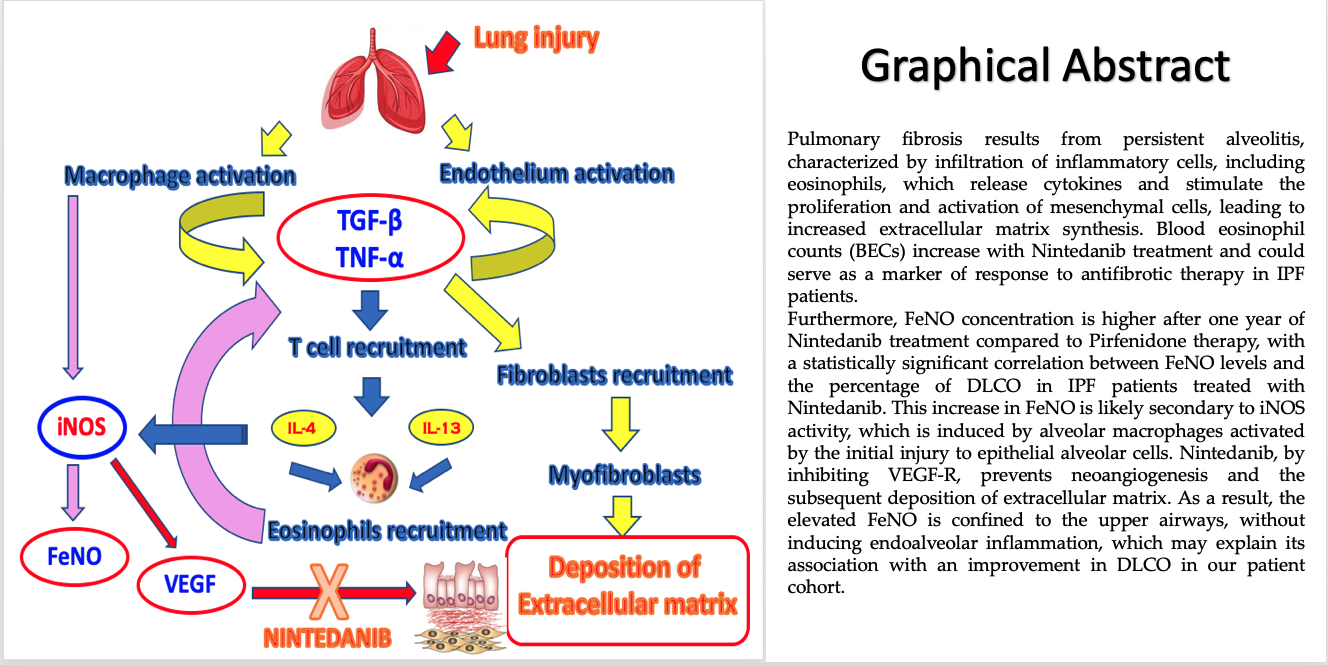

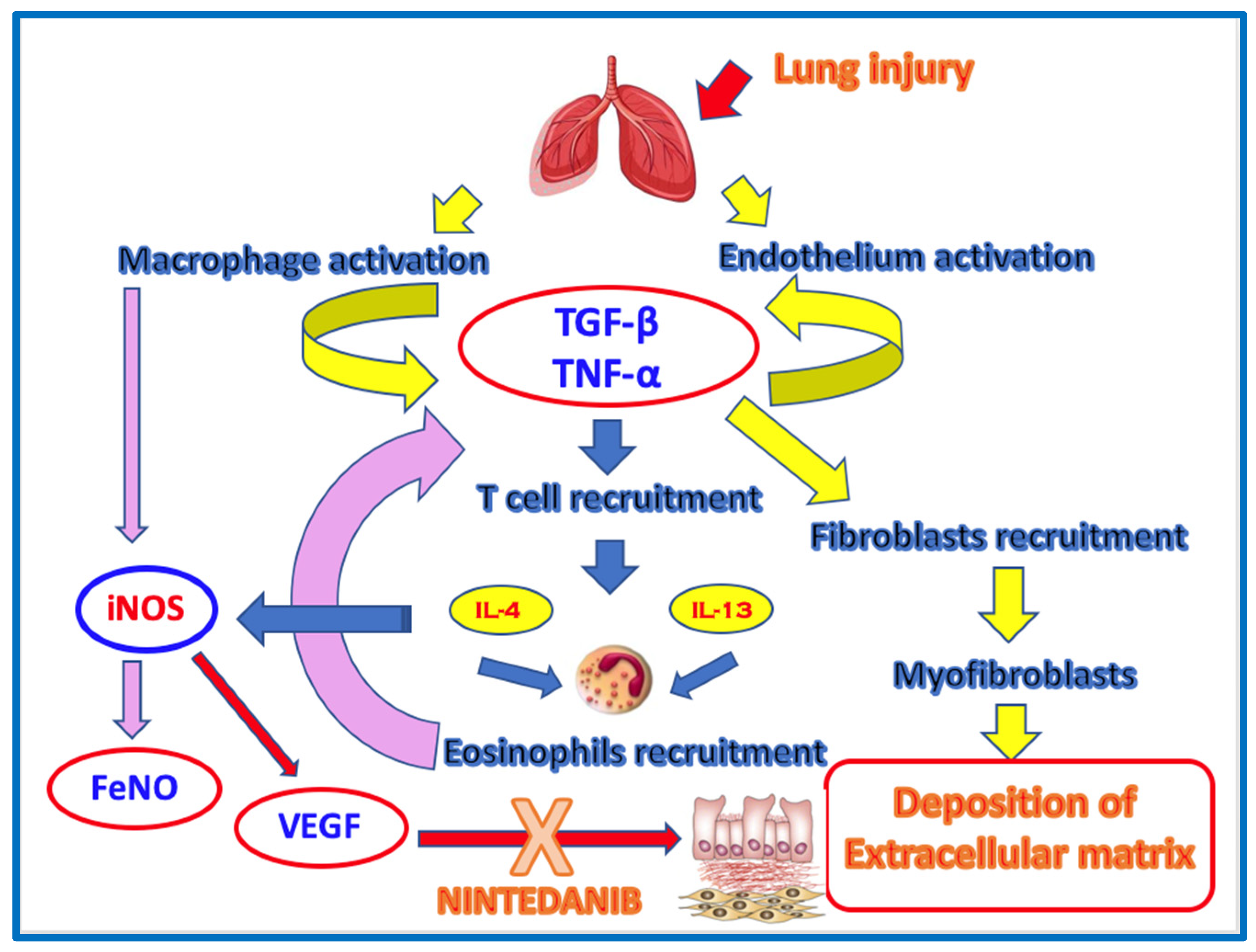

1.2. Eosinophils and Th2-inflammation in IPF

Eosinophils are bone marrow-derived granulocytes and are found in low numbers in the peripheral blood of healthy subjects. In type 2 inflammatory diseases, eosinopoiesis in the bone marrow is increased, resulting in a rise in the number of mature eosinophils released in the circulation. From the blood, eosinophils can migrate in multiple tissues and organs under both physiological and pathological conditions. Eosinophils exert their various functions through the synthesis and release of a variety of granule proteins and pro-inflammatory mediators [

15]. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) pathogenesis involves an unknown exogenous injury (cigarette smoke, pollution, dust), or genetic change or ageing related predisposal mediated alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) dysfunction. This leads to an activation of oxidative stress (DNA damage response), inflammatory response (eosinophil and neutrophil proteins) and downregulation of anti-apoptotic responses. These processes result in the activation of apoptotic pathway in AEC; AEC apoptosis is accompanied by activation of profibrotic pathways [transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)] leading to the recruitment and proliferation of resident lung fibroblasts and formation of fibroblast foci. Fibroblasts further differentiate into myofibroblasts with support of profibrotic mediators [TGF-β, matrix metallopeptidase 7 (MMP7), Th2 cytokines [interleukin 4, interleukin 13 (IL-4, IL-13)] and mitogenesis mediators (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor2 (VEGFsR2)]. In the context of pulmonary fibrosis in general, the profibrotic role of Th-2 inflammation, in particular of the cytokines IL-4 and IL-13, is well known from the literature. The key cellular mediator of fibrosis is the myofibroblast, which when activated serves as the primary collagen-producing cell. Myofibroblasts are generated from a variety of sources including resident mesenchymal cells, epithelial and endothelial cells in processes termed epithelial/endothelial-mesenchymal (EMT/EndMT) transition, as well as from circulating fibroblast-like cells called fibrocytes that are derived from bone-marrow stem cells. The immune system uses distinct populations of T cells to respond to inflammation and fibrosis. Some studies demonstrate that T helper 2 (Th2) cytokines promote fibrosis, whereas Th1 cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-12) promote inflammation. Th2 cytokines include IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13 and are important for fibrosis across multiple disease states. These cytokines promote eosinophils recruitment and activation; eosinophils, in turn, induce TGF-β to recruit fibroblasts, which then differentiate into myofibroblasts responsible for the deposition of extracellular matrix [

16,

17,

18,

19].

1.3. FeNO

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gaseous molecule that acts as a key mediator in numerous physiological processes [

20]. In particular, within the respiratory system, NO functions at low concentrations as a mediator in important physiological responses necessary for lung development (such as smooth muscle dilation, protection against bronchoconstrictive stimuli and ciliary motility) and as a neurotransmitter in the inhibitory non-adrenergic-non-cholinergic nervous system; at high concentrations, it acts as a mediator of inflammation and plays a role in the cytotoxic/cytostatic mechanisms against pathogens and cancer cells. The presence of nitric oxide in exhaled air was first demonstrated by chemiluminescence analysis and mass spectrometry by Gustafsson in 1991. Over the past two decades, FeNO has particularly emerged as one of the most important biomarkers in the management of bronchial asthma, and the procedure for its measurement was standardized for the first time in 2005 by the ATS and the ERS [

21]. Threshold values for FeNO have been identified for asthmatic adults and children, which can indicate a lack of adherence to treatment, a possible positive response to inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) therapy, and suggest the need to initiate ICS treatment. Additionally, as FeNO is a marker of T-helper 2-driven inflammation, it can predict a positive response to treatment with biological drugs for bronchial asthma [

22]. The reliability of FeNO in detecting NO-driven inflammation is limited to the proximal airways, and therefore, it does not appear reliable for assessing NO production and inflammatory processes involving distal airways or alveolar spaces. In the lung, nitric oxide is produced by various types of cells, including epithelial cells, mast cells and vascular endothelial cells. It is synthesized through the conversion of L-arginine into L-citrulline by the action of the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS). Three different isoforms have been cloned so far: endothelial (eNOS) and neuronal (nNOS), together referred to as constitutive forms (cNOS), and the inducible form (iNOS). The increase in NO levels in the exhaled air of asthmatic patients is attributed to the “over-expression” of the enzyme iNOS; iNOS is present in cells only after activation by endotoxins and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 1β (IL-1β), interferon γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). The concentrations of NO in exhaled air, expressed in parts per billion (ppb), are flow-dependent, as the diffusion of NO in the bronchial lumen depends on the transit time of the exhaled air in the airways. For this reason, ERS and ATS recommend performing at least 3 reproducible measurements (with a variability of about 5%) [

21]. The subject must inspire to total lung capacity with purified air to avoid contaminating the sample with potentially high levels of environmental NO. The subject then performs a 10-second exhalation at a pressure of 5-20 cmH2O, which ensures the closure of the soft palate, minimizing the risk of contamination with NO from the paranasal sinuses. An exhalation is considered adequate if a stable eNO concentration is reached at a flow of 50 ml/s [

21]. When measuring NO concentrations in exhaled air from the lower airways, it is important to exclude the contribution of nitric oxide produced in the nasal cavities, as the concentrations of nasal NO are much higher than those found in bronchial exhaled air. To minimize nasal “contamination,” the exhalation is performed at a constant flow against an expiratory resistance. Nitric oxide is quantified in “parts per billion” (ppb), with values under 12 ppb considered normal in young, non-asthmatic individuals. Values up to about 25 ppb in adults and around 20 ppb in children are still considered normal, while values between 25 and 50 ppb in adults and between 20 and 35 ppb in children are regarded as moderately elevated. Values above 50 ppb in adults and above 35 ppb in children are considered indicative of significant inflammation. The major advantage in the case of bronchial asthma is that it enables measurement of the level of inflammation in the airways and allows for the modulation of treatment with inhaled corticosteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, personalizing the dosage and using them only when truly necessary, i.e., when FeNO values are elevated [

22].

1.4. FeNO and IPF

The role of nitric oxide (NO) in the pathogenesis of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) is not fully understood, although oxidative stress is widely recognized as an essential component in the development of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). There are many enzymatic and immunological pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of IPF. However, to date, the primary driving force is considered to be an aberrant repair process of alveolar damage, genetically and epigenetically influenced, in response to epithelial injury, leading to irreversible and progressive lung remodelling. NO is considered a key mediator in the processes of healing and repair of epithelial damage, as most of the cells involved in these mechanisms (platelets, fibroblasts, epithelial cells and inflammatory cells) can produce NO. Enzymatic inhibition or gene deletion of NOS isoforms significantly impairs cell proliferation and angiogenesis, which are crucial in the epithelial repair process. The first study related to increased production of NO and its derivatives in the lungs of IPF patients was published in 1997, when Saleh and colleagues reported significant overexpression of iNOS in inflammatory cells and alveolar epithelium, associated with a marked production of nitrotyrosine compared to healthy subjects. A higher amount of NO derivatives was also confirmed in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples. Extended evaluation of exhaled NO was first described in IPF patients in 2011 by Schildge, who observed significant variations in alveolar NO concentrations across many ILD subgroups. Finally, some studies have indicated that NO plays a crucial role in the aberrant angiogenesis process in fibrotic lungs. Regarding this aspect, Iyer and colleagues demonstrated that NO is the key molecule in VEGF upregulated expression, through the PI3k/Akt pathway. These findings were also confirmed by proteomic studies and are particularly interesting since Nintedanib is a non-specific competitive antagonist of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF), and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) receptors. Despite these studies, the role of NO in pulmonary fibrogenesis remains, to date, controversial [

21].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

A total of 38 IPF patients (34 males, 29 former smokers; mean age 75.5 ± 6.7 years) followed at the Respiratory Department of the Saint Anna Hospital of Ferrara University were enrolled in the study (

Table 1).

The diagnosis of IPF was made according to the ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT 2022 guidelines, in a multidisciplinary setting. For all patients we collected: demographic data, smoking history (pack/year), clinical data, radiological data, laboratory tests (complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate-ESR, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, D-dimer, lactate dehydrogenase-LDH, creatinine, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein-HDL- cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein -LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides). We also collected pulmonary function tests (PFTs) including: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1), Forced Vital Capacity (FVC), Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second / Vital Capacity ratio (Tiffeneau index), Intrathoracic Gas Volume, Total Lung Capacity (TLC), Residual Volume, Diffusion Capacity for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO), and Carbon Monoxide Transfer Coefficient (values presented in milliliters and as a percentage of the predicted values). All patients underwent clinical and functional follow-up with PFTs every 6 months according to the study protocol. The study also recorded the main comorbidities across the entire population under study (hypertension, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, multidistrict atherosclerosis (ATS), hepatic steatosis, mild obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS), type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM), atrial fibrillation (AF), visceral obesity, bronchial asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) The incidence of these comorbidities in each patient group is shown in

Table 2.

The study was approved by the ethics committee (protocol lung-biomarkers, CE: 303/2023/Oss/AOUFE) of the University of Ferrara. All patients were Caucasian and signed informed consent for participation in the study, which was approved by the above-mentioned ethics committee. Data were entered into a specific database along with survival data. Patients enrolled in the study were invited to undergo the procedure for the detection of nitric oxide (NO) in exhaled air using the Medisoft device from SensorMedics, exactly 12 months after starting antifibrotic therapy. They were specifically encouraged to perform a maximal exhalation, and once the residual volume was reached, they were instructed to take a maximal inspiration, placing the mouthpiece of the device in their mouths until the residual volume was reached. Following this, a normal controlled exhalation monitored by the device allowed the assessment of the NO concentration in the exhaled air. During their exhalation, a tachometer appeared on the monitor, with a needle indicating the intensity at which the patient needed to exhale in order to maintain a stable exhalation flow (50 ml/sec), allowing for as precise a measurement as possible. Currently, FeNO is not used in the diagnosis or follow-up of IPF. However, the study examined the FeNO progression in two patient groups: IPF patients treated with Pirfenidone and IPF patients treated with Nintedanib, exploring whether its utilization could become a useful biomarker both regarding survival and response-to-therapy approaches. In this study, the blood eosinophil counts (BECs) was considered for the patients with IPF at baseline (T0 = time of diagnosis and initiation of antifibrotic therapy) and after 12 months (T12) of antifibrotic treatment. The aim was to assess the changes in BECs during antifibrotic therapy in IPF patients and to evaluate potential differences between the Pirfenidone and Nintedanib groups, to understand whether blood eosinophil counts (BECs) could serve as a marker of therapy response and whether it correlates with functional progression. The patients with IPF were categorized based on their antifibrotic therapy (Pirfenidone or Nintedanib), and their responses to therapy were evaluated at baseline (T0) and after 6 and 12 months (T6 and T12) in terms of survival, functional progression and side effects. Furthermore, the patients were subdivided according to their radiological patterns (UIP or probable UIP) to assess whether there was a difference in disease progression between these two patterns. This approach allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the role of BECs in response to antifibrotic treatments, the impact of treatment on functional status and any potential radiological differences that could influence the progression of IPF.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as means ± standard deviations. Since the data were not normally distributed, the one-way Kruskal-Wallis’s analysis of variance and the Dunn test were used for multiple comparisons. The Mann-Whitney test was used for pairwise comparisons of variables. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve areas were also calculated, and the Youden index was used to obtain cut-off values with the best sensitivity and specificity. The Spearman test was used to search for correlations between variables. A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis and data graphing were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software.

3. Results

The results obtained from the study are as follows: 18 patients on Pirfenidone therapy (IPF-Pirf), 13 patients on Nintedanib therapy (IPF-Nint), 7 patients not on antifibrotic therapy due to significant comorbidities (IPF).

In the IPF-Pirf group (18 patients), we observed: one patient died due to disease progression; the measurement of FeNO after 12 months of therapy (T12) was 20.8 ± 20.5 ppb; 4 patients (22%) experienced gastrointestinal side effects (diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, weight loss), but these were not severe enough to discontinue therapy; 3 patients (17%) had an acute exacerbation of the disease after 12 months of Pirfenidone treatment; 12 patients (66%) had a definite UIP pattern on HRCT chest scan at baseline (T0); 6 patients (33%) had a probable UIP pattern on HRCT chest scan at baseline (T0); of these, 2 had concomitant apical pulmonary emphysema. Blood eosinophil counts (BECs) at baseline (T0) was 0.16 ± 0.15 x10³/mcrl; BECs after 12 months of therapy (T12) was 0.13 ± 0.10 x10³/mcrl.

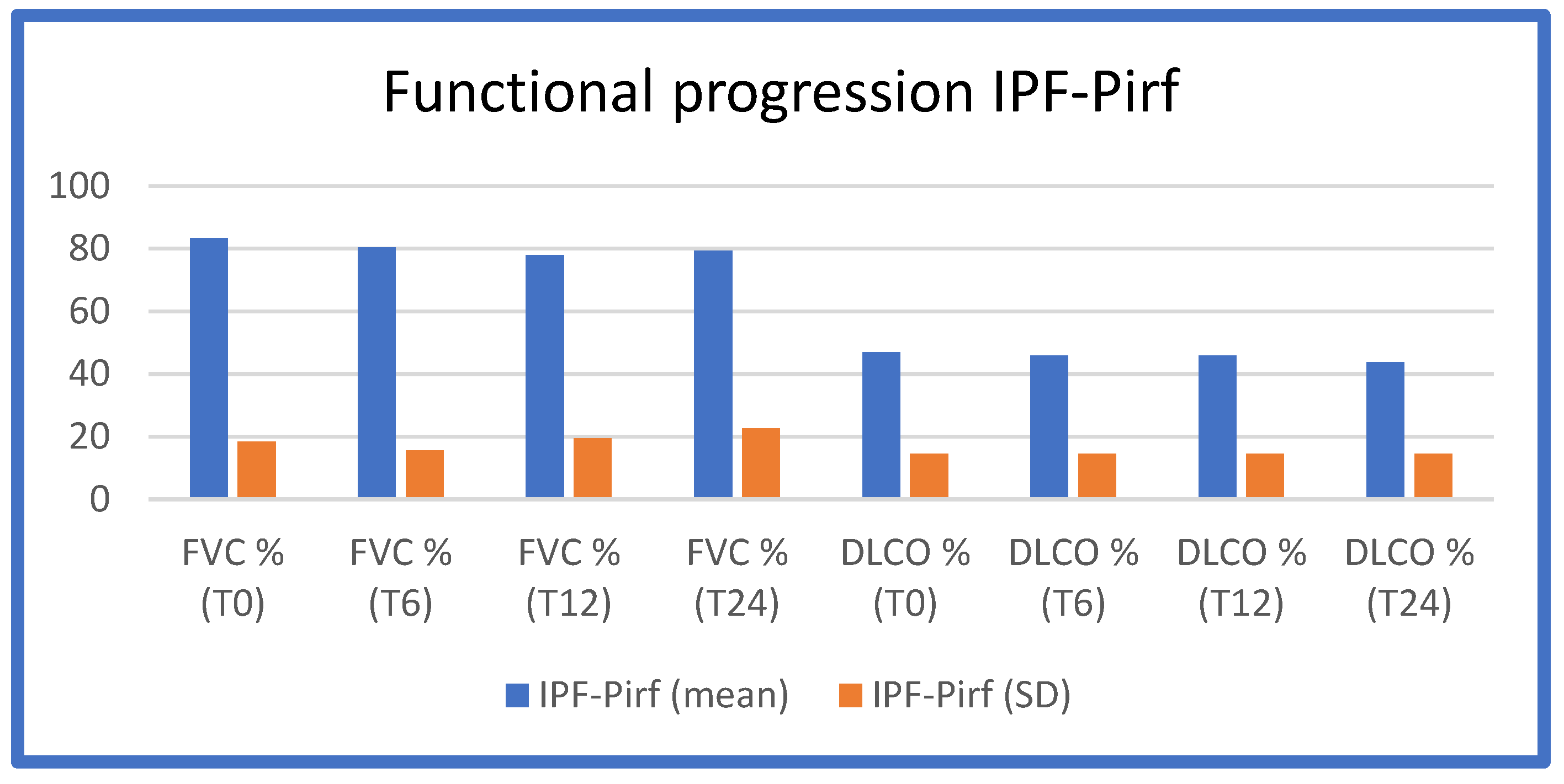

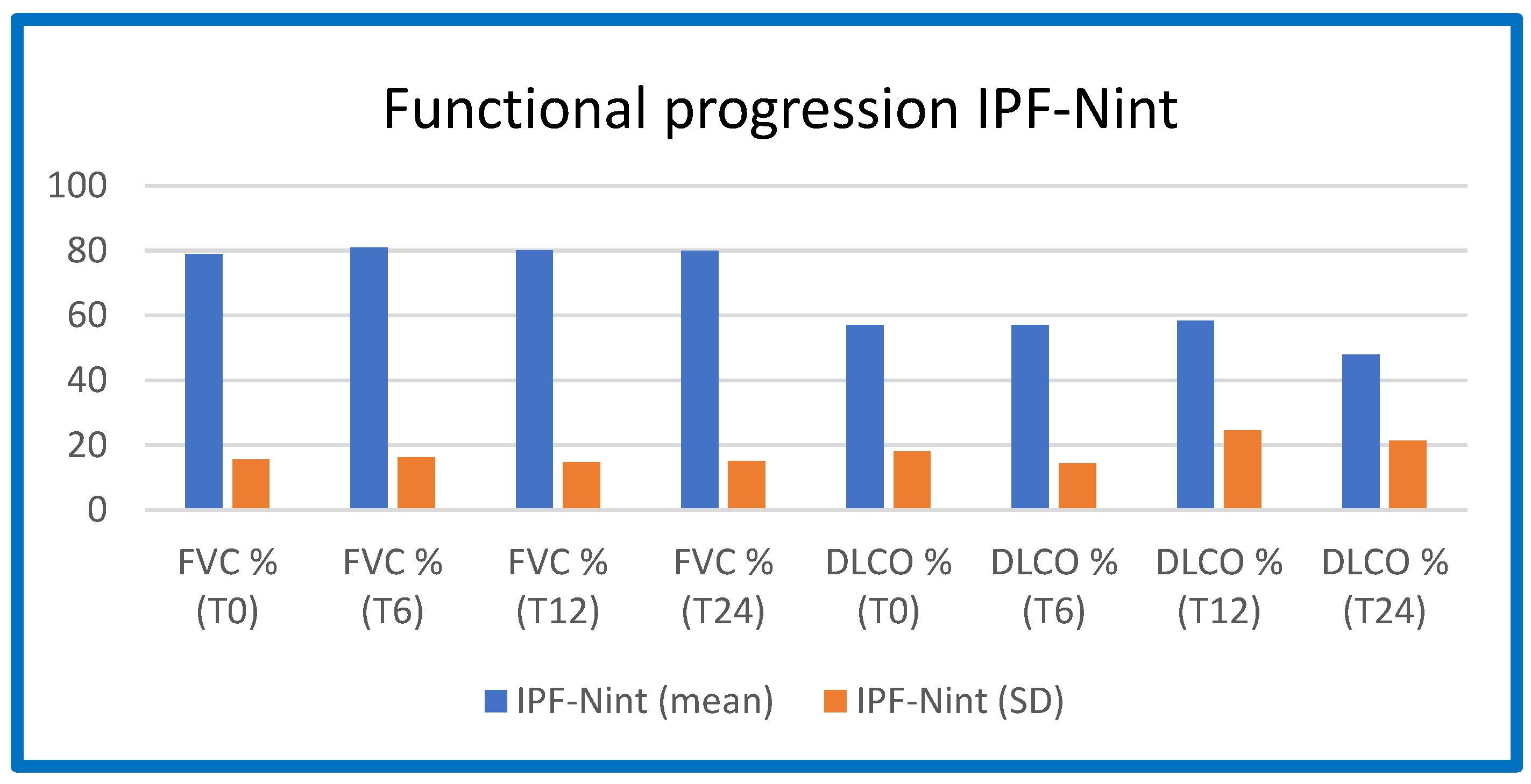

The functional worsening (FVC and DLCO as a percentage of predicted values) at T0, T6, T12, and T24 in the three IPF groups (Pirfenidone/Nintedanib/no therapy) is shown in

Table 3,

Figure 1,

Figure 2.

From these figures and tables, it is evident that IPF patients on Pirfenidone and Nintedanib treatment, enrolled in our study population, maintained functional stability over the 12-month treatment period, which is consistent with the data in the literature.

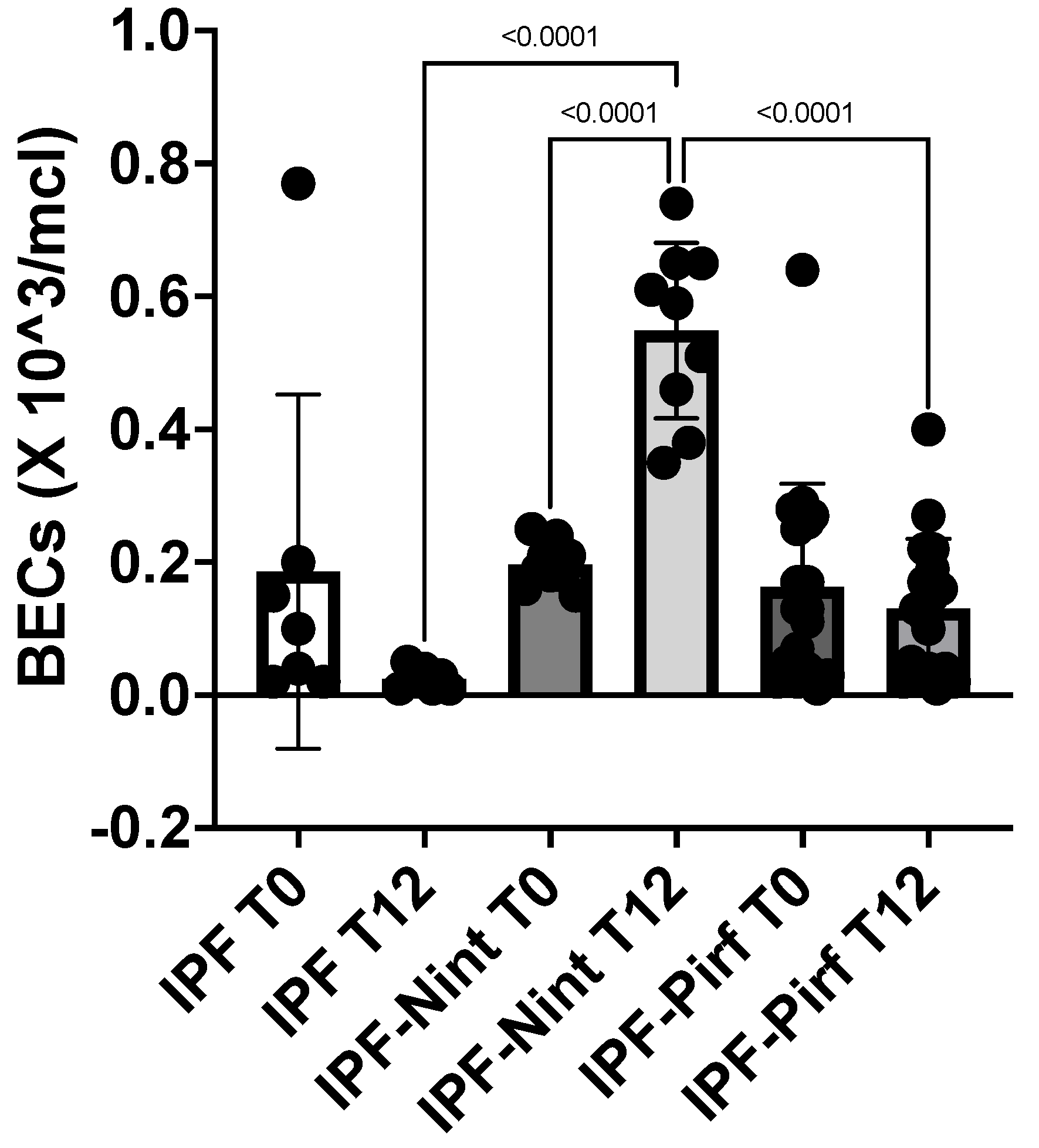

In the IPF-Nint group (13 patients), we observed: 2 patients died due to disease progression (after approximately 1 year of therapy; these patients were not candidates for Pirfenidone therapy due to functional criteria). The measurement of FeNO after 12 months of therapy (T12) was 29.42 ± 2.99 ppb; 8 patients (62%) experienced gastrointestinal side effects (diarrhea, weight loss, renal failure), but these were not severe enough to discontinue therapy. No patients experienced an acute exacerbation of the disease after starting Nintedanib therapy; 11 patients (85%) had a definite UIP pattern on HRCT chest scan at baseline (T0); 2 patients (15%) had a probable UIP pattern on HRCT chest scan at baseline (T0); BECs at baseline (T0) was 0.19 ± 0.03 x10³/mcrl; BECs after 12 months (T12) of Nintedanib treatment was 0.54 ± 0.13 x10³/mcrl.

In the IPF group not on antifibrotic therapy (7 patients), we observed: 2 patients died due to disease progression approximately one year after diagnosis; one patient had an acute exacerbation of the disease approximately one year after diagnosis; 6 patients (85%) had a definite UIP pattern on HRCT chest scan at baseline (T0); one patient (14%) had a probable UIP pattern on HRCT chest scan at baseline (T0). BECs at baseline (T0) was 0.08 ± 0.07 x10³/mcrl; BECs after 12 months without antifibrotic therapy (T12) was 0.02 ± 0.01 x10³/mcrl.

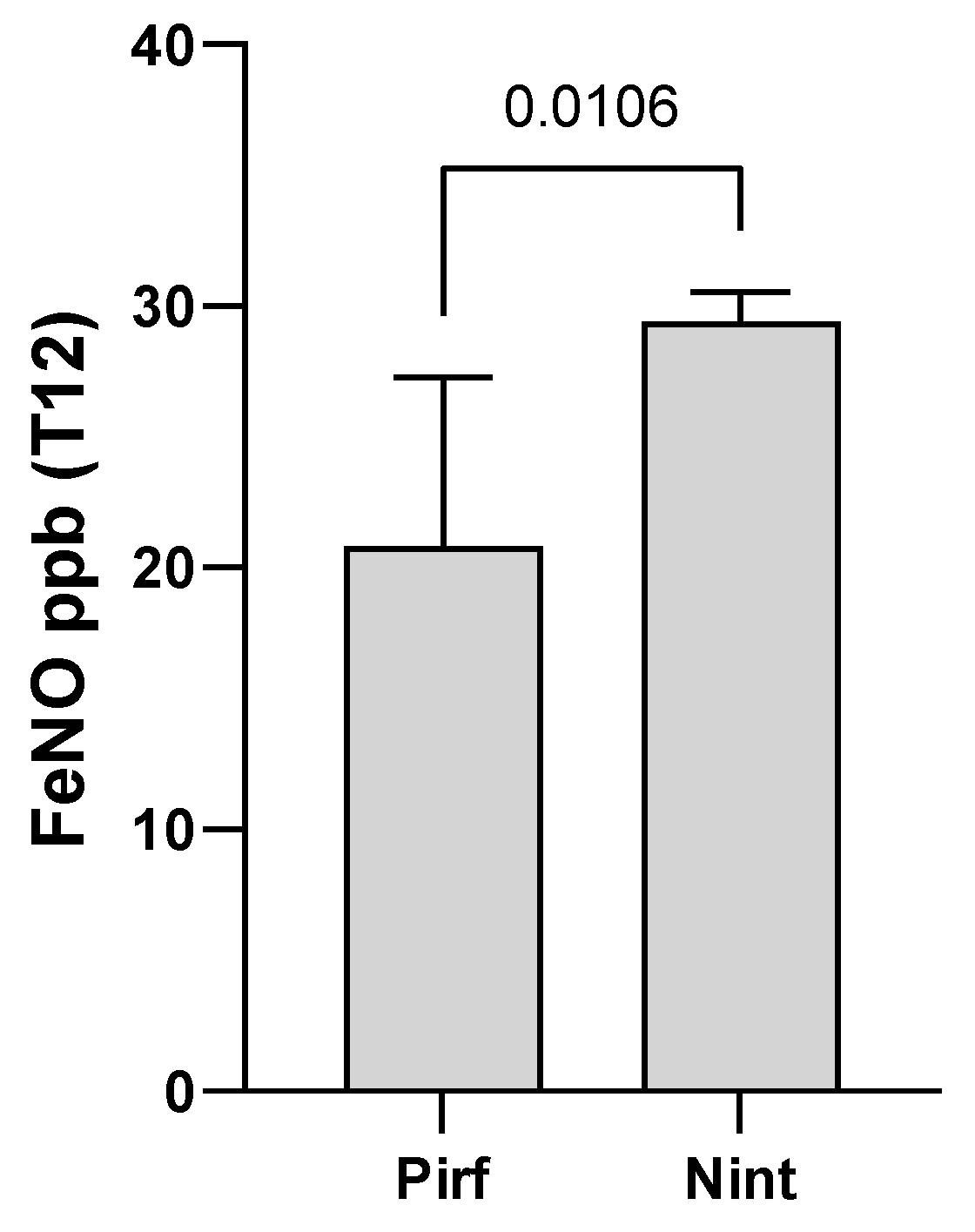

Our results show that analyzing the complete blood count in IPF patients at baseline (T0) and after 12 months (T12) of antifibrotic treatment, we found higher BECs in patients on Nintedanib treatment compared to those on Pirfenidone or not on treatment. Furthermore, after one year of antifibrotic treatment, we observed a higher concentration of FeNO in patients treated with Nintedanib compared to the Pirfenidone group (

Table 4).

Moreover, the increase in BECs after one year of treatment with Nintedanib (IPF-Nint T12) was statistically significant (p < 0,0001) compared to eosinophilia at the time of diagnosis (IPF-Nint T0). The difference in BECs after one year of Nintedanib treatment was also statistically significant compared to the IPF-Pirf group at T12 and to the IPF patients not receiving treatment at T12 (p < 0,0001) (

Figure 3).

We also measured exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy and we observed a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0106) in concentration between the IPF-Pirf and IPF-Nint groups, with a higher FeNO concentration in patients treated with Nintedanib (

Figure 4). The FeNO data in the IPF group one year after diagnosis was not available due to the insufficient number of patients.

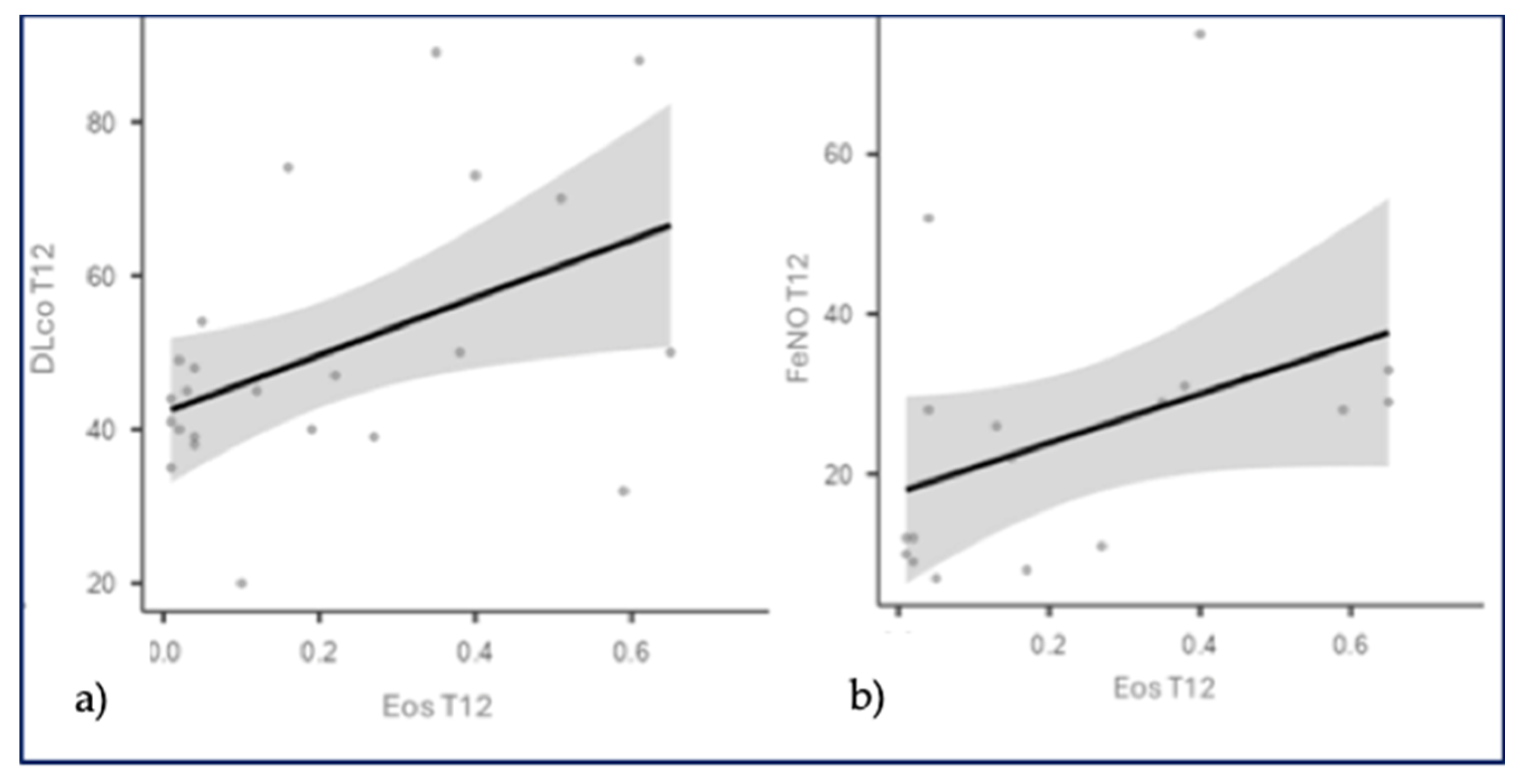

Considering the IPF-Nint group, we found statistically significant correlations between: BECs (T12) and DLCO as a percentage (T12): r=0.430, p=0.0406; BECs (T12) and FeNO (T12): r=0.575, p=0.0126. These statistical correlations suggest that as BECs increases after 12 months of treatment, there is also an increase in FeNO, as well as an improvement in DLCO function, supporting our hypothesis that eosinophils, when confined to the bloodstream, do not act at the site of extracellular matrix remodeling, leading to radiological and functional stability (probably due to the endothelial action mechanism of Nintedanib). Therefore, we could hypothesize that blood eosinophilia and FeNO could be considered potential biomarkers of response to antifibrotic treatment with Nintedanib (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

It is well known in the literature that pulmonary fibrosis is the result of persistent alveolitis with abnormal deposition of extracellular matrix. Alveolitis consists of infiltration by inflammatory cells, including eosinophils, which release cytokines and stimulate the proliferation, migration, and activation of mesenchymal cells, increasing extracellular matrix synthesis. The results of our study show that patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), either on Pirfenidone therapy or untreated, have a very low blood eosinophil counts (both at diagnosis and after one year of therapy). This low BECs in IPF is likely a consequence of alveolar tissue eosinophilia, which is the site where the fibrogenic process involving eosinophils occurs. The interesting results of our study, for the first time in literature, show that BECs increases during antifibrotic therapy with Nintedanib. This finding may be interpreted as an effect of the antifibrotic drug on the endothelial side. We could hypothesize that Nintedanib induces a shift of eosinophils from the alveolar tissue to the vascular compartment, leading to functional stability of the disease. It is known from the literature that eosinophilic alveolitis (>10%) has been found in the BAL (bronchoalveolar lavage) of IPF patients, suggesting that these inflammatory cells may be involved in the fibrogenic process. Furthermore, in the group of IPF patients on Nintedanib treatment, we observed a higher FeNO concentration compared to the Pirfenidone-group, after one year of treatment. We know that FeNO reflects the degree of inflammation in the proximal airways rather than in the alveolar space; however, it is well established that oxidative stress plays a role in the fibrogenic process in IPF, as well as the pro-angiogenic aspects of NO in the fibrotic lung. NO increases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), inducing neoangiogenesis in the fibrogenic process. Moreover, the VEGF receptor is a target of Nintedanib. It appears that endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is protective against vascular remodeling, whereas inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), overexpressed by inflammatory cells such as alveolar macrophages, contributes to the development of interstitial fibrosis. Therefore, FeNO could be considered a potential marker of response to Nintedanib antifibrotic therapy in IPF. Additionally, since 2017, attention has been drawn to CaNO (alveolar nitric oxide concentration), measured by multiple exhalations of FeNO (at least three exhalations at a flow rate of 50 ml/sec) in the context of pulmonary interstitial diseases, as a marker reflecting the degree of alveolar inflammation. CaNO may help differentiate between idiopathic and secondary fibrosis (due to connective tissue diseases), indicating whether antifibrotic or immunosuppressive therapy is warranted. This was confirmed in a study conducted in 2002 on pulmonary interstitial disease in systemic sclerosis, where elevated CaNO levels were inversely correlated with DLCO, reflecting high alveolar inflammation with elevated iNOS expression [

21].

In our study, however, we observed a statistically significant correlation after one year of treatment with Nintedanib between FeNO levels and the percentage of DLCO. Our hypothesis is that the increase in FeNO is secondary to the activity of iNOS, which is stimulated by alveolar macrophages activated by the initial damage on epithelial alveolar cells. Nintedanib, by inhibiting VEGF-R, prevents the process of neoangiogenesis and thus the deposition of extracellular matrix. Therefore, this elevated FeNO is concentrated in the upper airways, without leading to endoalveolar inflammation, which is why it is associated with an improvement in DLCO in our patients. Furthermore, an increase in BECs after 12 months of therapy and an improvement in DLCO, supporting our hypothesis that eosinophils, when confined to the bloodstream, do not act at the site of extracellular matrix remodeling, resulting in radiological and functional stability (likely due to the endothelial action mechanism of Nintedanib). We could hypothesize that blood eosinophilia and FeNO might be considered potential biomarkers of response to antifibrotic therapy with Nintedanib (

Figure 6).

In our study we also observed functional stability after one year of antifibrotic treatment in both the Pirfenidone and Nintedanib groups. In the IPF-Pirf group, there was a lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects but more episodes of acute exacerbation of the disease, while in the IPF-Nint group, no exacerbations of IPF were observed. Among patients with definite and probable UIP radiological patterns, we found the same degree of radiological and functional progression after one year of antifibrotic therapy, confirming what is known in the literature that the probable UIP pattern warrants early antifibrotic therapy, as the definite UIP pattern.

5. Conclusions

The results of our research project on biomarkers in IPF are particularly interesting, especially the role of eosinophils and FeNO as potential biomarkers of response to antifibrotic therapy (Nintedanib), on which there are currently no data in the literature. This needs to be further demonstrated in a larger population of patients. Monitoring FeNO and blood eosinophilia in patients treated with Nintedanib could be a valuable tool to determine whether the patient is a responder to therapy or if alternative treatment options (such as experimental protocols) should be considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Lucia Vietri and Mariano Reginato; methodology, Lucia Vietri and Mariano Reginato; software, Miriana d’Alessandro and Mariano Reginato; validation, Lucia Vietri and Alberto Papi; formal analysis, Lucia Vietri and Alberto Papi; investigation, Lucia Vietri and Mariano Reginato; resources, Lucia Vietri, Mariano Reginato and Aldo Carnevale; data curation, Lucia Vietri and Mariano Reginato; writing—original draft preparation, Lucia Vietri; writing—review and editing, Lucia Vietri and Alberto Papi; visualization, Lucia Vietri; supervision, Lucia Vietri, Mariano Reginato, Miriana d’Alessandro, Aldo Carnevale and Alberto Papi; project administration, Lucia Vietri; funding acquisition, Lucia Vietri and Alberto Papi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethics committee of University of Ferrara (Lung-Biomarkers protocol, CE: 303/2023/Oss/AOUFE, 05/09/2023), for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IPF |

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| BECs |

Blood eosinophil counts |

| FeNO |

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide |

| BAL |

Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| AEC |

Alveolar epithelial cell |

| VEFG-R |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor |

| NO |

Nitric oxide |

| eNOS |

endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| cNOS |

constitutive nitric oxide synthase |

| iNOS |

inducible nitric oxide synthase |

References

- Raghu, G; Weycker, D; Edelsberg, J; et al. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006,174, (7):810–6. [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G; Chen, S-Y; Yeh, W-S; et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001-11. Lancet Respir Med 2014, 2, (7):566–72. [CrossRef]

- Ley, B; Collard, HR; King, TE. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183, (4):431–40. [CrossRef]

- King, TE; Pardo, A; Selman, M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet Lond Engl 2011, 378, (9807):1949–61.

- Raghu, G; Remy-Jardin, M; Myers, JL; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 198, (5):e44-e68.

- Hopkins, RB; Burke, N; Fell, C; et al. Epidemiology and survival of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from national data in Canada. Eur Respir J 2016, 48, (1):187–95. [CrossRef]

- Agabiti, N; Porretta, MA; Bauleo, L; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) incidence and prevalence in Italy. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis Off J WASOG 2014, 31, (3):191–7.

- Selman, M; King, TE; Pardo, A; et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med 2001, 134, (2):136–51. [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G; Collard, HR; Egan, JJ; et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 2011, 183, 788–824. [CrossRef]

- Chilosi, M; Doglioni, C; Murer, B; et al. Epithelial stem cell exhaustion in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis Off J WASOG 2010, 27(1), 7– 18.

- Richeldi, L; Collard, HR; Jones, MG. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 2017, 389, 1941-1952.

- Meyer, KC. Pulmonary fibrosis, part I: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis. Expert Rev Respir Med 2017,11(5), 343–59.

- Raghu, G; Remy-Jardin, M; Richeldi, L; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022, 205(9), e18-e47. [CrossRef]

- Polastri, M; Dell’Amore, A; Zagnoni, G; et al. Preoperative physiotherapy in subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis qualified for lung transplantation: implications on hospital length of stay and clinical outcomes. J Thorac Dis 2016,8(5), E264-268. [CrossRef]

- Gigon, L; Fettrelet, T; Yousefi, S; Simon, D; Hans-Uwe, S. Eosinophils from A to Z. Allergy 2023, 78,1810-1846. [CrossRef]

- Khan, T; Dasgupta, S; Ghosh, N; Chaudhury, K. Proteomics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the quest for biomarkers. Molecular Omics- The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Richard, LG 3rd; Wilson, M; Wynn, T; et al. Type 2 immunity in tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat Rev Immunol 2018, 18 (1),62-76.

- Nuovo, GJ; Hagood, JS; Magro, CM; Chin, N; Kapil, R; et al. The distribution of immunomodulatory cells in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Mod. Pathol 2012, 25,416–33. [CrossRef]

- T A Wynn. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 2008, 214 (2), 199-210. [CrossRef]

- Nagase H. The role of fractional nitric oxide in exhaled breath (FeNO) in clinical practice of asthma. Rinsho Byori 2014 ,62(12),1226-33.

-

Cameli, P; Bargagli, E; Bergantini, L; et al. Extended Exhaled Nitric Oxide Analysis in Interstitial Lung Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (17):6187; 21. Cameli, P; Bargagli, E; Bergantini, L; et al. Extended Exhaled Nitric Oxide Analysis in Interstitial Lung Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2020,21, (17):6187. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardolo, FLM; Stufano, S; Carriero, V; et al. Utilizzo della misura di ossido nitrico nell’aria espirata: un update, Rassegna di Patologia dell’Apparato Respiratorio 2021,36, fascicolo 2.

Figure 1.

The progression of respiratory function at baseline (T0 = time of diagnosis and initiation of antifibrotic therapy), after 6 months of treatment (T6), after 12 months of treatment (T12), and after 24 months of treatment (T24) in the IPF-Pirf group (patients treated with Pirfenidone).

Figure 1.

The progression of respiratory function at baseline (T0 = time of diagnosis and initiation of antifibrotic therapy), after 6 months of treatment (T6), after 12 months of treatment (T12), and after 24 months of treatment (T24) in the IPF-Pirf group (patients treated with Pirfenidone).

Figure 2.

The progression of respiratory function at baseline (T0 = time of diagnosis and initiation of antifibrotic therapy), after 6 months of treatment (T6), after 12 months of treatment (T12), and after 24 months of treatment (T24) in the IPF-Nint group (patients treated with Nintedanib).

Figure 2.

The progression of respiratory function at baseline (T0 = time of diagnosis and initiation of antifibrotic therapy), after 6 months of treatment (T6), after 12 months of treatment (T12), and after 24 months of treatment (T24) in the IPF-Nint group (patients treated with Nintedanib).

Figure 3.

The graphical representation of blood eosinophil counts (BECs) in IPF patients on antifibrotic treatment (IPF-Nint- IPF-Pirf) and those without treatment (IPF) at baseline (T0) and after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy (T12).

Figure 3.

The graphical representation of blood eosinophil counts (BECs) in IPF patients on antifibrotic treatment (IPF-Nint- IPF-Pirf) and those without treatment (IPF) at baseline (T0) and after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy (T12).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) concentration after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy, both Pirfenidone and Nintedanib.

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) concentration after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy, both Pirfenidone and Nintedanib.

Figure 5.

a) Correlation between DLCO percentage and blood eosinophil counts at T12 (after 12 months of Nintedanib therapy). b) Correlation between FeNO and blood eosinophil counts at T12 (after 12 months of Nintedanib therapy).

Figure 5.

a) Correlation between DLCO percentage and blood eosinophil counts at T12 (after 12 months of Nintedanib therapy). b) Correlation between FeNO and blood eosinophil counts at T12 (after 12 months of Nintedanib therapy).

Figure 6.

Possible mechanism of action of eosinophils and FeNO in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Figure 6.

Possible mechanism of action of eosinophils and FeNO in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Table 1.

demographic characteristics of study population.

Table 1.

demographic characteristics of study population.

| |

IPF (38) |

| Age (mean ± SD) |

75,5 ± 6,7 |

| Male (%) |

34 (89%) |

| Smokers former/current |

29/0 |

Table 2.

Main comorbidities in the study population.

Table 2.

Main comorbidities in the study population.

| |

IPF |

| Hypertension |

21 (55%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia |

10 (26%) |

| Ischemic heart disease |

8 (21%) |

| ATS |

4 (11%) |

| Hepatic steatosis |

1 (3%) |

| Mild OSAS |

1 (3%) |

| Diabetes mellitus type II |

7 (18%) |

| Atrial Fibrillation |

8 (21%) |

| Visceral obesity |

2 (5%) |

| Bronchial Asthma |

1 (3%) |

| GER |

3 (8%) |

Table 3.

Functional worsening in the study population at baseline (T0 = time of diagnosis and starting antifibrotic therapy), after 6 months of treatment (T6), after 12 months of treatment (T12), and after 24 months of treatment (T24).

Table 3.

Functional worsening in the study population at baseline (T0 = time of diagnosis and starting antifibrotic therapy), after 6 months of treatment (T6), after 12 months of treatment (T12), and after 24 months of treatment (T24).

| |

IPF- Pirf |

IPF-Nint |

IPF |

| FVC % del pred T0 |

83,4 ± 18,49 |

79 ± 15,6 |

58 ± 7,93 |

| FVC % del pred T6 |

80,33 ± 15,61 |

81 ± 16,3 |

// |

| FVC % del pred T12 |

77,9 ± 19,47 |

80,17 ± 14,8 |

65,5 ± 10,6 |

| FVC % del pred T24 |

79,3 ± 22,7 |

80 ± 15,17 |

// |

| DLCO % del pred T0 |

46,92 ± 14,5 |

57,1 ± 18,03 |

56 ± 8,10 |

| DLCO % del pred T6 |

45,76 ± 14,47 |

57 ± 14,48 |

// |

| DLCO % del pred T12 |

45,76 ± 14,47 |

58,3 ± 24,51 |

44 ± 6,37 |

| DLCO % del pred T24 |

43,76 ± 14,53 |

48 ± 21,4 |

// |

Table 4.

Blood eosinophil counts (BECs) in IPF patients on antifibrotic treatment (IPF-Pirf, IPF-Nint) and not on treatment (IPF) at baseline (T0) and after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy; exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) concentration after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy (T12).

Table 4.

Blood eosinophil counts (BECs) in IPF patients on antifibrotic treatment (IPF-Pirf, IPF-Nint) and not on treatment (IPF) at baseline (T0) and after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy; exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) concentration after 12 months of antifibrotic therapy (T12).

| |

BECs x10^3/mcrl

(T0) |

BECs x10^3/mcrl

(T12) |

FeNO ppb

(T12) |

IPF

|

0,08 ± 0,07

|

0,02 ± 0,01

|

//

|

IPF-Pirf

|

0,16 ± 0,15

|

0,13 ± 0,10

|

20,8 ± 20,5

|

IPF-Nint

|

0,19 ± 0,03

|

0,54 ± 0,13

|

29,4 ± 2,99

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).