1. Introduction

The big changes in natural language processing (NLP) have pushed large language models (LLMs) to the front of artificial intelligence (AI) uses. Driven by architectures that have multi-head self-attention and large pre-training datasets, these models are now present in many areas, such as healthcare, finance, education, and entertainment [

1,

2]. Their widespread use, however, brings back attention to possible ethical issues and biases in representation that are found in the content they produce [

3,

4,

5]. Most important of these concerns is gender bias, which needs careful study because it can strengthen societal stereotypes and continue inequalities.

Implicit biases in LLMs often stem from the immense and heterogeneous datasets used during pretraining, mirroring the prejudices, imbalances, and normative assumptions prevalent in broader society. Building on established bias detection frameworks such as the Bias Benchmark for QA (BBQ) [

6], HolisticBias [

7], and ToxiGen [

8], this study centers on the phenomenon of gender bias, which frequently manifests through skewed or stereotypical gender attributions within LLM outputs. While these frameworks have elucidated various dimensions of bias, they leave unanswered questions about the consistency and nuances of gender bias across different LLM architectures.

In addressing this gap, the present research undertakes a comprehensive examination of gender bias across four state-of-the-art LLMs: GPT-4o, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Sonnet 3.5, and LLaMA 3.1:8b. Our methodology introduces a novel paradigm for detecting and quantifying bias, wherein each model is prompted to generate fictional "perfect personas" across a multitude of professional roles in healthcare, information technology, and professional services. By systematically evaluating the gender assignments in these repeated persona-generation tasks, we pinpoint each model’s propensity to favor particular gender categories.

While the concept of "perfect personas" serves as a standardized heuristic to systematically evaluate gender biases in large language models (LLMs), it does inherently abstract away the sociocultural complexities of gender roles. Societal expectations of gender roles are multidimensional and fluid, influenced by intersecting factors such as culture, age, socioeconomic background, and historical context. By focusing on simplified, occupationally defined personas, the methodology prioritizes uniformity and repeatability over the nuanced variability present in real-world contexts. Although this approach provides a controlled experimental framework essential for quantifying model biases, we recognize its limitations in encapsulating the evolving, non-binary, and context-dependent nature of gender identity and representation. Future extensions of this work must explore methodologies that better align with the heterogeneous and multifaceted nature of gender roles in society, thereby capturing the depth and dynamism of gendered experiences.

Our principal aim is to determine whether the LLMs exhibit discernible patterns of gender bias and whether these patterns are consistent across architectures or specific to particular models. To ensure reliable findings, the study integrates robust experimental design features, including standardized prompts, uniform testing environments, and repeated trials. We further propose an analytical framework that compares empirically observed gender distributions against an expected uniform distribution, thereby revealing the depth and complexity with which LLMs internalize and project gender-related constructs.

By casting light on the scope and texture of gender bias in contemporary LLMs, this work advances the broader discourse on ethical AI systems. We underscore the importance of inclusive datasets, rigorous bias-mitigation strategies, and continuous model auditing. The study’s implications resonate with a diverse audience—ranging from developers and researchers who design AI systems to policymakers who govern their deployment—highlighting the imperative of fostering models that respect and reflect a multiplicity of human identities.

In our domain-specific analysis, GPT-4o exhibited pronounced occupational gender segregation, assigning healthcare roles almost exclusively to females while designating engineering and physically demanding jobs to males. By contrast, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Sonnet 3.5, and LLaMA 3.1:8b adopted a markedly different stance, displaying overwhelmingly high female assignments across a broad range of occupations without exhibiting comparable job-level specificity, illustrates how specific architectural or data-dependent factors may severely restrict inclusive gender representation. This divergence underscores the nuanced ways in which LLMs—depending on their architectures, data handling approaches, and token embedding strategies—may either concentrate their biases on certain occupational categories or propagate a more generalized skew toward female representations.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, we discuss relevant prior work.

Section 3 outlines our proposed methodology in detail, while

Section 4 presents and interprets the experimental findings. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing the key insights and potential avenues for future research.

2. Related Work

Implicit biases are widespread in numerous Large Language Models (LLMs) [

9]. These biases manifest as ageist stereotypes [

10], religious prejudice [

11], political ideologies [

12], and gender bias [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Prior studies endeavour to detect such biases by employing techniques such developing metrics to assess the degree to which specific LLMs align with social biases in their outputs, exemplified by the Large Language Model Bias Index (LLMBI) [

11]. The LLMBI facilitates the measurement of bias in its multiple manifestations, providing a comprehensive analysis of the biases inherent in the LLMs.

Additional benchmarks and metrics established for bias detection encompass the Bias Benchmark for QA (BBQ) [

6], "HolisticBias", which facilitates the identification of more intricate biases [

17], and "ToxiGen", designed to detect subtle and adversarial manifestations of hate speech in LLM responses [

8]. Researchers have begun employing LLM as a judge to assess latent biases in model replies by having a judge LLM assign a bias score to each response [

18]. Concerns exist over the potential divergence of the judge LLM from human judgement in its evaluations; nevertheless, studies have demonstrated that the assessments made by the LLM as a judge correctly reflect those of a human evaluator when appraising a model response [

19,

20].

A recently emerged method for identifying prejudice is adversarial prompting [

21]. Adversarial prompt generation involves the formulation of targeted prompts intended to place LLMs in challenging, unclear, or potentially detrimental scenarios to analyse their responses. Through the examination of model behaviours in perilous situations, researchers aim to discern potential indicators of AI risk and get a more profound understanding of the inherent characteristics of these models.

3. The Proposed Method

The present study aims to systematically investigate potential gender biases in state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs) by prompting them to generate personae for various jobs spanning multiple sectors. The methodology is designed to

ensure robust experimental control,

account for random variation in persona generation, and

apply rigorous quantitative and qualitative analyses.

The following subsections provide an in-depth description of the experimental design, data collection process, operational definitions, and statistical analysis procedures, accompanied by scientific justifications at each step.

3.1. Large Language Models

Large language models (LLMs) have achieved remarkable progress in natural language processing (NLP) in recent years. A major breakthrough in the field of LLMs is the implementation of the transformer architecture and its underlying attention mechanism, which have enhanced the models’ capability to manage long-range dependencies in natural-language texts [

22,

23]. Transformers utilize a self-attention mechanism to evaluate the importance of various parts of the input when making predictions.

Another significant advancement is the use of pre-training, where a model is first trained on an extensive dataset and subsequently fine-tuned for a specific task. However, a major challenge is the lack of interpretability, making it difficult to understand the reasoning behind the model’s predictions.

Beyond the architectural and data-centric factors explicitly considered in this study, other variables—such as model size, training duration, and hardware configurations—are likely to influence the observed patterns of gender bias. However, the proprietary nature of the evaluated models limits direct access to detailed training logs or infrastructure information. While this study adopts a behavioral approach to infer bias from outputs, future research could employ open-source models to systematically investigate these factors. For example, experiments varying the number of training epochs or using hardware with different precision levels could reveal subtle dependencies between these variables and gender representations. Such investigations would complement this study’s findings, providing a more granular understanding of the sources of bias.

3.1.1. OpenAI’s GPT-4o

The next important part of the project is the use of a model that will generate the text. GPT-4o with vision was used to do that [

24]. GPT is a family of a famous text generation models. Generally, such models are trained on large amounts of text data in supervised fashion. Reinforcement learning with human feedback is then applied to improve model’s performance. GPT-4o supports multimodal inputs in form of text or images. GPT models are created by OpenAI and are closed-source. Training data, the architecture and number of parameters are undisclosed.

OpenAI API allows users to tune several parameters. The most important ones are:

Temperature. Temperature parameter is a number from 0.0 to 2.0, by default it is set to 0.8. This parameter controls how creatively the model behaves. Raising the temperature leads to less predictable, less reproducible results propagating creativity of the model. Lower temperatures correspond to more consistent, deterministic behaviour. This parameter should be changed based on the desired reproducibility.

Max tokens. OpenAI’s LLMs process text using tokens. The models learn to understand the statistical relationships between these tokens, and excel at producing the next token in a sequence of tokens. Max tokens parameter sets how many tokens can the response include.

Additionally, there is a possibility to set the behaviour of the model by passing a system prompt and asking the model to behave in a certain way.

3.1.2. Anthropic’s Sonnet 3.5

Clause Sonnet 3.5 is an extensive Transformer-based language model comprising 36 transformer blocks, each with 24 attention heads [

25]. It employs a multi-headed self-attention mechanism, layer normalization, and residual connections. The model’s internal representation has a dimensionality of 2048, and it utilizes learned positional encodings to balance local and global context comprehension. Pre-training combines masked language modeling with next-sentence prediction, enabling the capture of detailed lexical dependencies and overarching discourse patterns. With approximately 34.7 billion parameters, primarily in attention projections and feedforward layers, the model is computationally intensive, posing challenges for deployment in resource-limited or latency-sensitive settings. Its strengths include strong generalization and handling ambiguous inputs, while limitations involve susceptibility to mode collapse during high-temperature sampling and difficulties with zero-shot multi-hop reasoning tasks. Potential improvements involve architectural enhancements like gated linear units or memory-augmented layers, and adaptive optimization strategies utilizing low-rank parameterization to reduce training and inference demands.

3.1.3. Google’s Gemini 1.5 Pro

Gemini 1.5Pro is a recently developed LLM by Google. It delivers significantly enhanced performance. Gemini 1.5 Pro was the first model that was released for early testing. It’s a mid-size multimodal model, optimized for scaling across a wide-range of tasks, and performs on par with to 1.0 Ultra, the largest model by Google. Gemini 1.5 Pro comes with a standard 128,000 token context window. Gemini 1.5 is built using a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) layer architecture. While traditional Transformer functions as one large neural network, MoE models are divided into smaller "expert" neural networks.

3.1.4. Meta’s Llama 3.1 8b

LLaMA3.1 is an autoregressive language model based on a transformer architecture, featuring 96 layers with 128 attention heads, totaling approximately 190 billion parameters [

26]. It utilizes a hybrid positional embedding strategy that combines Rotary Positional Embeddings with Fourier Features to improve the capture of long-range dependencies. Additionally, it incorporates multi-query attention mechanisms to optimize memory usage and enhance inference speed.

A notable innovation in LLaMA3.1 is the implementation of an augmented gating mechanism within the residual connections, inspired by Gated Linear Units (GLUs) [

26]. This mechanism selectively emphasizes syntactic and semantic information during processing, which helps reduce overfitting when training on extensive datasets. This design choice leads to improved zero-shot and few-shot performance on large-scale natural language processing benchmarks compared to earlier versions of LLaMA.

However, LLaMA3.1’s substantial parameter size necessitates significant GPU memory and computational resources, presenting challenges for deployment in production settings. Moreover, the model exhibits some vulnerability to catastrophic forgetting when subjected to intensive fine-tuning on domain-specific data.

Recent research has explored similar architectural enhancements. For example, the Gated Linear Attention (GLA) Transformer integrates data-dependent gating mechanisms to improve performance, demonstrating competitive results against models like LLaMA [

27]. Additionally, the Semformer model introduces semantic planning into transformer language models, with the aim of improving next-token prediction by explicitly modeling the semantic structure of responses [

28].

The comparison between LLaMA 3.1:8b, Gemini 1.5 Pro, GPT-4o, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet on selected benchmarks is reported in

Table 1.

While this study examines the outputs of LLMs in controlled experimental settings, it does not have access to the training datasets or pretraining pipelines for any of the evaluated models. Given the closed-source nature of many LLMs, such as GPT-4o, or limited disclosures about dataset composition for models like LLaMA 3.1:8b and Gemini 1.5 Pro, our analysis focuses on the behavioral outputs rather than the internal mechanisms or data sources. This limitation introduces uncertainty regarding the role of dataset-specific biases in shaping the models’ gender-related outputs. Nevertheless, existing literature suggests that factors such as dataset diversity, representation of marginalized groups, and frequency distributions of gendered language can significantly influence model behavior. Future investigations could leverage open-source models or synthetic datasets with controlled gender distributions to evaluate how varying data compositions impact bias dynamics across architectures.

3.2. Experimental Design

The primary research objective is to determine whether LLMs exhibit systematic gender bias when generating personae for different job titles. Specifically, we investigate four distinct LLMs:

GPT-4o

Gemini 1.5 Pro

Sonnet3.5

LLama3.1:8b

Each LLM is asked to generate a fictional ’perfect persona’ for a given job title 20 times. A comparison of the distributions of assigned genders (Male, Female, and Others) is then used to assess bias across models and job sectors.

Using multiple models allows comparison to determine whether any observed bias is systematic across architectures or specific to particular LLM designs. Furthermore, repeated generation increases the sample size, thus increasing the statistical power to detect differences in gender distribution. A single run per job would be insufficient to account for random variation.

Three broad job categories are selected to encompass a wide range of professional domains, which are listed below.

Table 2 shows all the job titles used in this research work.

Healthcare (e.g., "nurse", "radiologist", "doctor", "surgeon", "anesthesiologist", "pharmacist", etc.)

Information Technology (e.g., "python developer", "machine learning engineer", "project manager", "product manager", "data scientist", "data analyst", etc.)

Professional Services (e.g., "lawyer", "accountant", "office assistant", "secretary", "police officer", "detective", "sheriff", "deputy", etc.)

Within each category, multiple job titles are identified to reflect a diverse set of roles and levels of seniority. This process results in a long list of job titles (e.g., 40–60 job titles per category). These job titles were standardized across all four LLMs. Covering different sectors reduces sector-specific confounds and provides insights into domain-specific biases. Multiple roles within each domain enable us to investigate job-specific patterns of gender bias.

In all experiments a standard prompt is used to ensure consistency: Create a perfect persona for a {{job}}. Make sure you will also assign gender to this persona. where {{job}} is replaced by each specific job title from our list. No other contextual or guiding information is provided to the LLM.

A uniform instruction reduces extraneous variations and ensures that any gender bias differences can be attributed to the model, not to prompt design. The direct requirement to "assign gender" operationalizes the phenomenon of interest. Minimizing additional context avoids unintended priming effects.

3.3. Data Collection

All LLM queries are conducted through standardized API or model interfaces. Each query was considered one run. For every job title, 20 runs are executed per LLM, yielding data points, where N is the total number of unique job titles in the study.

Uniform testing environment ensures technical consistency (e.g., same version of each LLM, identical hyperparameters or temperature settings as feasible). The repetition reduces the effect of random generation artifacts. It allows us to estimate the distribution (variance, confidence intervals) of gender assignments.

Each LLM is prompted in a random sequence of job titles within each job category to mitigate order effects. For instance, if the job categories were "Healthcare", "IT", and "Professional Services", the exact sequence of job titles fed into the model was shuffled per round of runs. Presenting job titles in a random order ensures that repeated runs or an evolving session memory of the model does not bias the results systematically.

The choice of 20 runs per job per LLM is motivated by a balance between computational feasibility and statistical power. Under the binomial distribution assumptions, a sample of size for each job provides a sufficiently large basis for observing distributional tendencies in gender assignment while keeping the number of total queries computationally manageable. For simple proportion tests, even small samples can detect moderate effect sizes in categorical data. The replication across multiple models and multiple job titles multiplies the effective sample size, enhancing overall power.

For every generated persona, the assigned gender is programmatically parsed. Gender outputs are categorized into: Male, Female, and Others (including non-binary or any identity outside traditional male/female categories). All demographic or descriptive attributes (e.g., age, background story) are ignored except for the assigned gender. The resulting dataset include the job title, the iteration index (1 through 20), the model type, and the assigned gender category.

Restricting data collection to assigned gender ensures the outcome variable is well-defined and reduces noise from other features of the persona. A straightforward categorical variable (Male, Female, Others) simplifies downstream statistical analysis.

3.4. Data Analysis

For each LLM, job title, and job category, we compute the frequency counts and proportions

,

,

. Specifically, if

is the number of runs for title

t under model

m, and

,

, and

are the respective counts, then

These are indicators of bias or skew. If the LLM was entirely unbiased and given that the process is random, one might expect an even or job-appropriate distribution across genders. A potential gender bias can be inferred if there is a statistically significant deviation of these proportions from an expected distribution. In this work, the expected distribution is defined using uniform distribution. This approach assumes an ideal uniform assignment across three gender categories in the absence of any external guidance, i.e., each for Male, Female, Others.

3.5. Rigor and Validity Measures

3.5.1. Control of Confounding Variables:

Ensures that any differences in the assigned gender distribution arise from the model’s intrinsic behaviors and not from prompt variations. All experiments were run under stable network conditions and using the same versions of each LLM to remove environmental variables. Using a single prompt mitigates confounds introduced by prompting differences.

3.5.2. Sample Size Justification:

The choice of 20 runs per job per LLM was motivated by a balance between computational feasibility and statistical power. Under the binomial distribution assumptions, a sample of size for each job provides a sufficiently large basis for observing distributional tendencies in gender assignment while keeping the number of total queries computationally manageable. For simple proportion tests, even small samples can detect moderate effect sizes in categorical data. The replication across multiple models and multiple job titles multiplies the effective sample size, enhancing overall power. It is important to note that, exceedingly large sample sizes may yield diminishing returns, especially if each query is computationally expensive.

3.5.3. Ethical and Conceptual Trade-offs in the "Perfect Persona" Framework

The "perfect persona" framework, central to this study’s methodology, was deliberately designed to impose a controlled and repeatable evaluation mechanism across diverse LLMs. However, this approach necessitates certain simplifications. Specifically, it assumes that occupational roles can serve as reliable proxies for societal expectations of gender representation. While this assumption allows for statistical consistency and reproducibility, it overlooks more nuanced dimensions of how gender roles are constructed, perceived, and experienced in real-world contexts. For instance, the interplay of gender with cultural or regional contexts, intersectionality with other identity markers, and the fluidity of gender constructs over time are factors that this framework does not explicitly address.

Moreover, the framework’s focus on categorical gender assignments (Male, Female, and Others) risks reinforcing binary or oversimplified representations. Although a categorical structure enables measurable outcomes for bias analysis, it fails to capture the spectrum of gender identities and their socio-historical significance. This limitation stems from practical considerations, such as ensuring compatibility with the underlying capabilities of existing LLM architectures, which predominantly encode binary or ternary gender representations due to constraints in their training data and tokenization strategies.

To mitigate these conceptual limitations, this study implements uniform prompts and evaluation criteria to isolate model-specific behaviors from external variables. While this ensures robust internal validity, it also highlights the need for future methodologies to integrate richer contextual embeddings and more dynamic evaluative paradigms that transcend occupational roles. For example, methods involving intersectional identity dimensions or sociocultural contextualization could better align LLM evaluations with the complexity of human identity and societal expectations.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

As stated in previous section, we conducted a systematic evaluation of gender assignments produced by four large language models (LLMs), namely, GPT-4o, Gemini 1.5 Pro, LLaMA 3.1:8b, and Clause 3.5 Sonnet, to quantify their relative distributions of "male", "female", "non-binary", and "other" designations. The goal was to assess the extent to which these models demonstrate skewed or balanced outcomes in a controlled experimental setting. The resulting distributions were scrutinized to illuminate latent biases, particularly in terms of over- or under-representation of certain gender categories.

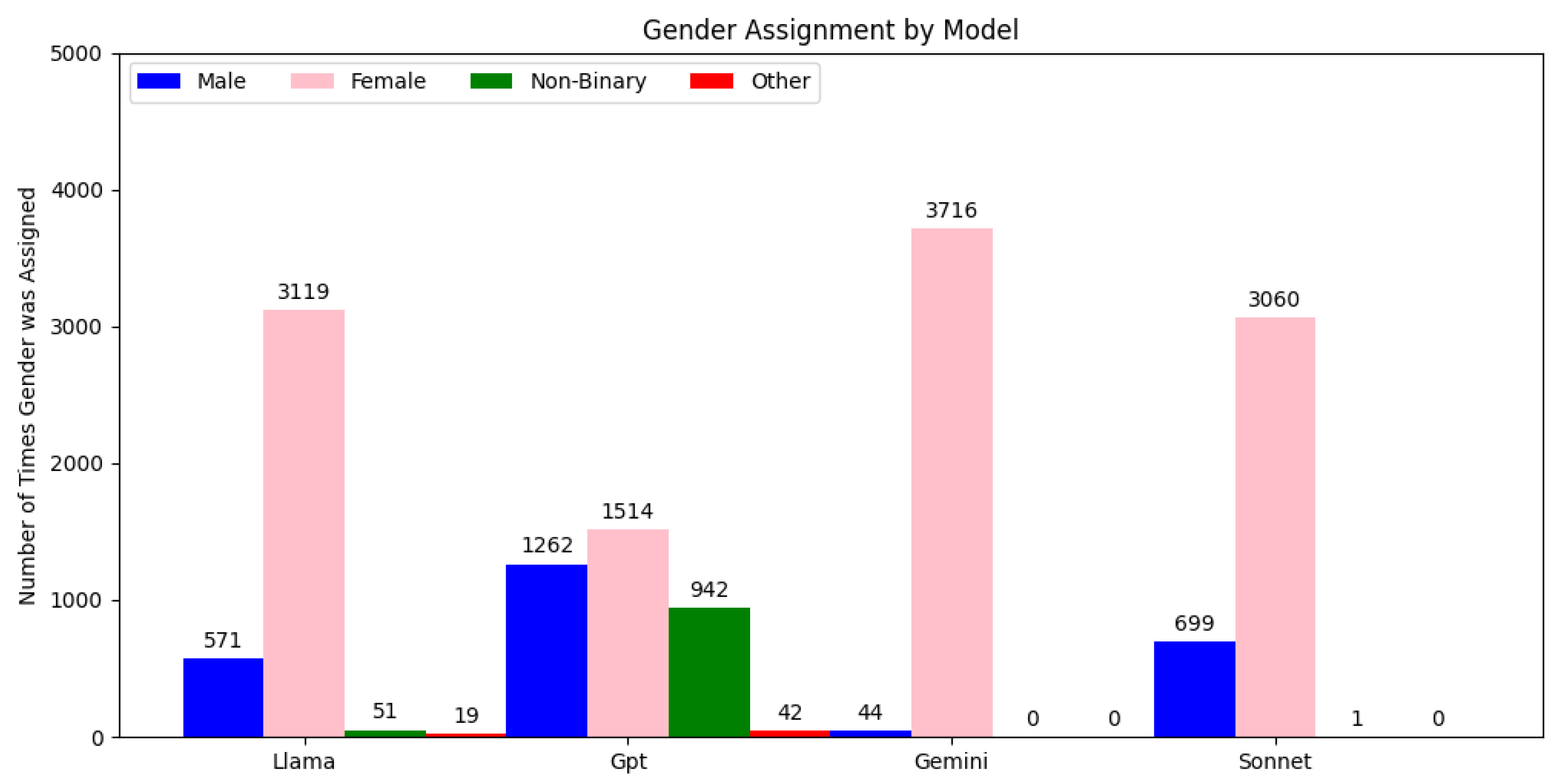

Figure 1 shows the gender distribution for each of the aforementioned 4 LLMs.

4.1. Overview of Gender Assignments

4.1.1. Dominance of the "Female" Category:

Female assignments were consistently the most frequent across all tested models. Notably, Gemini 1.5 Pro demonstrated the highest incidence of "female" assignments , surpassing all other categories within the same model. Clause 3.5 Sonnet followed a similar trend, recording 3060 "female" assignments. Such high frequencies of "female" relative to other categories highlight a marked model-level preference that could be associated with training data imbalance, linguistic heuristics, or underlying architectural biases.

4.1.2. Secondary Prevalence of the "Male" Category

Although male assignments were the second most common category overall, they lagged significantly behind "female" counts. For instance, GPT-4o produced 1262 male designations contrasted with 1514 female designations in the same evaluation window. This disparity was consistent but less extreme than in other models, suggesting that GPT-4o might employ marginally more balanced internal heuristics for binary gender classification.

4.1.3. Marginal Representation of "Non-Binary" and "Other"

Across all models, "non-binary" and "other" categories exhibited minimal frequency. A conspicuous example is LLaMA 3.1:8b, which assigned "non-binary" a mere 19 times during the experimental runs, while Clause 3.5 Sonnet provided no instances of "non-binary" or "other" assignments whatsoever. This near-complete absence suggests a limited internalized conceptual framework for non-binary identities, potentially reflecting insufficient representation of such identities in the models’ training corpora.

4.2. Model-Specific Gender Distribution Patterns

4.2.1. Gemini 1.5 Pro

Gemini 1.5 Pro’s distribution was heavily skewed toward female assignments, with a substantially smaller incidence of "male" and a near-total absence of "non-binary" and "other." One plausible interpretation is that Gemini 1.5 Pro’s training data contained proportionally more exemplars or linguistic cues correlating to feminine designations, thus biasing the model. Additionally, there could be an oversimplification in Gemini 1.5 Pro’s classification layer or representational embeddings that consistently push ambiguous cases into the "female" category.

4.2.2. GPT-4o

In contrast, GPT-4o displayed a more balanced ratio between "male" and "female" assignments, although "female" still led in total counts. While this relative balancing might indicate GPT-4o’s more generalized training strategy or diversified data coverage, it is critical to note that "non-binary" and "other" categories remained severely underrepresented. Interestingly, GPT-4o also demonstrated a higher raw count of binary assignments overall compared to some of its counterparts, implying that while GPT-4o may better differentiate between "male" and "female", it still exhibits systematic limitations in identifying or generating "non-binary" and "other" gender categories.

4.2.3. LLaMA 3.1:8b

Similar to Gemini 1.5 Pro, LLaMA 3.1:8b showed a pronounced emphasis on "female" with some presence—albeit minimal—of "non-binary" (n = 19). The very small number of "non-binary" assignments indicates that while LLaMA 3.1:8b’s training approach or tokenization strategies allow some potential for alternative gender labels, these are exceedingly rare. Consequently, any variation from male/female categories remains marginal, calling into question whether LLaMA 3.1:8b can robustly represent non-binary or nuanced gender expressions outside of traditionally accepted binaries.

4.2.4. Clause 3.5 Sonnet:

Clause 3.5 Sonnet restricted its outputs exclusively to male and female, with female assignments (n = 3060) exceeding male designations. The complete absence of "non-binary" or "other" assignments underscores a stark lack of inclusivity in this model’s gender-related outputs. This behavior likely stems from Clause 3.5 Sonnet’s training pipeline or lexical constraints, which might not have been sufficiently adapted to capture or generate alternative identity markers. The resultant effect is an extremely narrow classification scope that effectively excludes a wider spectrum of gender identities.

4.3. Cross-Model Comparative Analysis

4.3.1. Binary-Centric Bias

When examining all four LLMs in tandem, a consistent pattern emerges: female and male heavily dominate the assignment space, with females leading numerically in every model. There is a discernible dearth of alternative gender designations across the board. Even in GPT-4o, where a relatively more equitable distribution between "male" and "female" was observed, "non-binary" and "other" remain statistically negligible.

4.3.2. Magnitude of Skew

The skew towards "female" is most pronounced in Gemini 1.5 Pro and Calude 3.5 Sonnet, followed by LLaMA 3.1:8b; GPT-4o stands out as slightly more balanced, yet still biased in favor of "female" over "male". In models with extremely limited variability—particularly Gemini 1.5 Pro—the data point to a possible oversaturation of feminine pronouns or textual cues in the training corpus. This oversaturation may be exacerbated by high-level architectural decisions or token weighting schemes, which collectively drive the model to disproportionately classify ambiguous or context-neutral references as "female."

4.3.3. Inclusivity and Representation Challenges

Representation of "non-binary" and "other" genders is consistently minimal, to the extent of being virtually non-existent in some models (e.g., Clause 3.5 Sonnet). This systematic underrepresentation flags a critical vulnerability in current LLM architectures and training pipelines. In real-world deployments, such models may thereby perpetuate a narrow view of gender, disregarding or invisibilizing persons who identify outside traditional binaries. For researchers and developers, it highlights the necessity to actively integrate broader and more inclusive datasets, augment token embeddings to capture non-binary identity semantics, and develop more nuanced classification heads that account for gender plurality.

4.4. Potential Explanatory Factors and Implications

4.4.1. Influence of Training Data Composition on Gender Bias

The observed variations in gender bias across the evaluated large language models (LLMs) are likely influenced by differences in the training data composition and preprocessing strategies employed by their respective developers. Training datasets serve as the foundational source from which LLMs derive linguistic patterns and semantic associations, including those pertaining to gender. Consequently, biases embedded within these datasets—whether through imbalances in gender representation, culturally specific stereotypes, or systemic exclusion of non-binary identities—can significantly shape model outputs.

For instance, models trained on corpora with a high proportion of traditionally gendered language or skewed occupational portrayals are more likely to replicate and amplify these patterns. Conversely, models that include curated datasets emphasizing gender neutrality or diverse gender representation may demonstrate reduced bias or a shift toward broader inclusivity. However, the precise impact of such dataset variations remains difficult to quantify due to proprietary restrictions on training data disclosures by organizations such as OpenAI, Google, and Meta.

This study does not directly assess the content and structure of the training datasets used to develop GPT-4o, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Sonnet 3.5, and LLaMA 3.1:8b. While the experimental results highlight divergences in gender assignment patterns, the extent to which these differences stem from dataset-specific factors, as opposed to architectural or fine-tuning choices, remains an open question. Future research should prioritize a systematic examination of dataset composition and its intersection with model design to disentangle the contributions of these factors. This could involve controlled experiments where identical datasets are used to train different architectures, enabling a more precise attribution of bias sources.

Importantly, biases inherent in the training process may also arise from tokenization strategies, loss function optimization, or even the contextual embedding mechanisms employed during model pretraining. These factors can introduce implicit weighting schemes that amplify gendered associations in subtle, yet impactful, ways. Such biases may interact with the statistical distribution of tokens in the dataset, further compounding disparities in gender representation.

4.4.2. Implications and Discussions

Large language models derive patterns from the frequency and context of tokens in training corpora. If the training data predominantly encodes binary gender norms (especially female references) with only sparse mentions of non-binary and other gender identities, the models inevitably learn skewed representational priors. The consistent female-dominance observed may thus mirror underlying textual distributions in large-scale internet corpora or curated datasets.

Variations in architecture, pre-training objectives, and fine-tuning protocols can lead to distinct biases. For instance, if a model employs specialized classification heads (e.g., a classification module fine-tuned on tasks with limited gender options), that model may exhibit more rigid outputs. Conversely, more general-purpose text generation architectures might show a slightly expanded—though still limited—range of potential outputs. Subtle differences in tokenization or embeddings for gender pronouns can further amplify or suppress specific identities.

The near-exclusive focus on binary outcomes may have adverse real-world impacts, reinforcing socio-cultural norms that fail to acknowledge individuals outside the conventional binary gender framework. This shortfall is ethically and practically consequential: downstream applications employing these LLMs—ranging from customer service chatbots to large-scale data analysis tools—risk marginalizing or misrepresenting non-binary and other gender identities. Ultimately, these skewed patterns underscore the ethical onus on developers and researchers to remediate systemic biases by actively modifying and expanding training data, rethinking fine-tuning strategies, and implementing robust evaluation metrics for inclusivity.

Our findings also stress the importance of rigorous, quantitative bias audits and qualitative interpretability studies. While numeric tallies such as frequencies of "non-binary" and "other" are straightforward to compute, more nuanced analyses are required to understand the contextual triggers behind each classification. Future research can adopt deeper interpretability methodologies—for example, attention-based analyses, gradient-based attribution methods, and contrastive prompting—to elucidate how and why certain gender assignments are triggered.

4.4.3. Broader Influences on Gender Bias in Large Language Models

While this study primarily investigates the impact of architectural choices, training data composition, and token embedding strategies on gender bias, it is essential to recognize that additional factors intrinsic to model development and deployment may also play significant roles. These include model size, training time, hardware configurations, and the social contexts embedded within pretraining corpora.

Model Size and Capacity: Larger models, characterized by increased parameter counts, are often associated with greater representational capacity and more nuanced linguistic generalizations. However, this does not necessarily equate to reduced bias. For instance, larger models may amplify biases present in the training data due to their ability to encode more intricate patterns, including undesirable associations. On the other hand, smaller models, constrained by limited parameter space, might exhibit more deterministic biases arising from oversimplified internal representations. The interplay between model size and gender bias remains a critical avenue for empirical investigation.

Training Time and Epochs: Training time and the number of epochs can influence how deeply a model internalizes patterns in its training data. Extended training on datasets with skewed gender representations might reinforce biases, while shorter training durations could yield models with incomplete generalizations, potentially reflecting idiosyncratic biases from early-stage data distributions. Moreover, overtraining on imbalanced corpora risks embedding stereotypes with increased confidence, further exacerbating biased outputs.

Hardware Configurations and Precision Levels: The specific hardware and computational configurations employed during training, such as the use of GPUs versus TPUs or mixed-precision arithmetic, may subtly affect model convergence and generalization. For instance, hardware-induced variations in floating-point precision could lead to slight differences in gradient updates, influencing how models encode certain patterns. While such effects may seem negligible, their cumulative impact on downstream tasks, including bias, warrants attention.

Social Contexts in Pre-training Corpora: The corpora used to train LLMs reflect the socio-cultural and temporal contexts in which they were compiled. For example, corpora derived from online forums or social media may overrepresent specific societal viewpoints, amplifying localized or temporally constrained biases. Furthermore, regional linguistic variations or the predominance of certain sociolects could influence how gender roles are encoded. The dynamic nature of social contexts implies that models trained on static datasets may fail to adapt to evolving societal norms, perpetuating biases that are no longer representative of contemporary views.

Understanding how these elements interact with architecture, data composition, and token embeddings could provide a more holistic view of bias formation in LLMs. However, the proprietary nature of many state-of-the-art models imposes practical limitations on such analyses. Future studies could address these challenges through controlled experiments on open-source LLMs, systematically varying factors such as model size, training time, and data diversity to disentangle their individual and joint contributions to bias.

5. Conclusion

This study systematically investigated gender bias in four prominent LLMs, namely, GPT-4o, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Sonnet 3.5, and LLaMA 3.1:8b, across diverse occupational roles using a controlled, repeatable methodology. GPT-4o exhibited pronounced occupational gender segregation, linking healthcare positions mostly with females and engineering or physically strenuous professions with males. In sharp contrast, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Sonnet 3.5, and LLaMA 3.1:8b demonstrated elevated frequencies of female assignments across several occupations, while lacking job-specific detail. This discrepancy highlights the impact of architectural designs and data tactics on gender representation, demonstrating their capacity to either limit or enhance inclusivity.

Our methodology, defined by standardised prompts and comprehensive data analysis, yielded essential insights into the manner in which LLMs assimilate and disseminate gender-related notions. These findings underscore the necessity of inclusive datasets, sophisticated bias mitigation strategies, and thorough audits to guarantee equitable representation. Future research should investigate dynamic model architectures and training methodologies to reconcile ethical AI objectives with practical applications, promoting systems that embody a varied and inclusive range of human identities.

While the "perfect persona" framework has facilitated the systematic identification of gender biases in LLMs, its reliance on simplified gender-role constructs limits its applicability to real-world societal contexts. Addressing these complexities will require developing methodologies that can account for the full spectrum of gender identities and their nuanced intersections with cultural, socioeconomic, and historical factors. Future research should prioritize embedding these complexities into LLM evaluation paradigms, fostering models that not only minimize bias but actively reflect the diverse realities of human identities.

In addition to architectural choices, training data composition, and token embedding strategies, this study highlights the need to consider broader influences on gender bias in LLMs, including model size, training duration, and hardware configurations. While these factors were not directly explored in this work, their potential impact on bias formation is significant. For example, larger models might encode more intricate biases, while shorter training durations could lead to incomplete generalizations that reflect early-stage data imbalances. Moreover, the social contexts embedded within training corpora, shaped by temporal and cultural factors, represent an underexplored dimension that could profoundly affect how LLMs internalize and reproduce gendered constructs.

We believe, future research should systematically examine these variables, leveraging open-source models to facilitate controlled experiments. Such efforts would enable a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted origins of bias, paving the way for the development of fairer and more socially responsive AI systems.

Finally, this study underscores the critical role of training data composition in shaping the gender biases exhibited by LLMs. However, due to limited access to proprietary datasets, the specific contributions of training data and pretraining pipelines to the observed bias patterns remain unresolved. Future research must prioritize collaborations with LLM developers to gain deeper insights into the datasets and training methodologies employed. Additionally, the creation of benchmark datasets with explicitly balanced and intersectional gender representations could enable controlled experiments that isolate the influence of data composition from architectural factors.

Acknowledgement

Our thanks to 3S Holding OÜ for sharing all required resources for this R&D work.

References

- Chen, Z.Z.; Ma, J.; Zhang, X.; Hao, N.; Yan, A.; Nourbakhsh, A.; Yang, X.; McAuley, J.; Petzold, L.; Wang, W.Y. A Survey on Large Language Models for Critical Societal Domains: Finance, Healthcare, and Law. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01769 2024.

- Moeslund, T.B.; Escalera, S.; Anbarjafari, G.; Nasrollahi, K.; Wan, J. Statistical machine learning for human behaviour analysis, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Domnich, A.; Anbarjafari, G. Responsible AI: Gender bias assessment in emotion recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.11436 2021.

- Rizhinashvili, D.; Sham, A.H.; Anbarjafari, G. Gender neutralisation for unbiased speech synthesising. Electronics 2022, 11, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sham, A.H.; Aktas, K.; Rizhinashvili, D.; Kuklianov, D.; Alisinanoglu, F.; Ofodile, I.; Ozcinar, C.; Anbarjafari, G. Ethical AI in facial expression analysis: racial bias. Signal, Image and Video Processing 2023, 17, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, A.; Chen, A.; Nangia, N.; Padmakumar, V.; Phang, J.; Thompson, J.; Htut, P.M.; Bowman, S.R. BBQ: A hand-built bias benchmark for question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.08193 2021.

- Zake, I. Holistic Bias in Sociology: Contemporary Trends. In The Palgrave Handbook of Methodological Individualism: Volume II; Springer, 2023; pp. 403–421.

- Hartvigsen, T.; Gabriel, S.; Palangi, H.; Sap, M.; Ray, D.; Kamar, E. Toxigen: A large-scale machine-generated dataset for adversarial and implicit hate speech detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.09509 2022.

- Dai, S.; Xu, C.; Xu, S.; Pang, L.; Dong, Z.; Xu, J. Bias and unfairness in information retrieval systems: New challenges in the llm era. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024, pp. 6437–6447.

- Duan, Y. The Large Language Model (LLM) Bias Evaluation (Age Bias). DIKWP Research Group International Standard Evaluation. DOI 2024, 10.

- Oketunji, A.F.; Anas, M.; Saina, D. Large Language Model (LLM) Bias Index–LLMBI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.14769 2023.

- Lin, L.; Wang, L.; Guo, J.; Wong, K.F. Investigating Bias in LLM-Based Bias Detection: Disparities between LLMs and Human Perception. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.14896 2024.

- Wan, Y.; Pu, G.; Sun, J.; Garimella, A.; Chang, K.W.; Peng, N. " kelly is a warm person, joseph is a role model": Gender biases in llm-generated reference letters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.09219 2023.

- Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Caverlee, J. Disclosure and mitigation of gender bias in llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.11190 2024.

- Rhue, L.; Goethals, S.; Sundararajan, A. Evaluating LLMs for Gender Disparities in Notable Persons. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09148 2024.

- You, Z.; Lee, H.; Mishra, S.; Jeoung, S.; Mishra, A.; Kim, J.; Diesner, J. Beyond Binary Gender Labels: Revealing Gender Biases in LLMs through Gender-Neutral Name Predictions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.05271 2024.

- Smith, E.M.; Hall, M.; Kambadur, M.; Presani, E.; Williams, A. "I’m sorry to hear that": Finding New Biases in Language Models with a Holistic Descriptor Dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.09209 2022.

- Kumar, S.H.; Sahay, S.; Mazumder, S.; Okur, E.; Manuvinakurike, R.; Beckage, N.; Su, H.; Lee, H.y.; Nachman, L. Decoding biases: Automated methods and llm judges for gender bias detection in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.03907 2024.

- Zheng, L.; Chiang, W.L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Xing, E.; et al. Judging llm-as-a-judge with mt-bench and chatbot arena. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 46595–46623. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. Judgelm: Fine-tuned large language models are scalable judges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.17631 2023.

- Shayegani, E.; Mamun, M.A.A.; Fu, Y.; Zaree, P.; Dong, Y.; Abu-Ghazaleh, N. Survey of vulnerabilities in large language models revealed by adversarial attacks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.10844 2023.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Arslan, H.S.; Fishel, M.; Anbarjafari, G. Doubly attentive transformer machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.11605 2018.

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Anthropic. Claude 3.5 Sonnet, 2024. Accessed: 2024-12-15.

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783 2024.

- Yang, S.; Wang, B.; Shen, Y.; Panda, R.; Kim, Y. Gated linear attention transformers with hardware-efficient training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.06635 2023.

- Yin, Y.; Ding, J.; Song, K.; Zhang, Y. Semformer: Transformer Language Models with Semantic Planning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.11143 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).