Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Study design and Patients

- DNA extraction and Genome – Wide DNA Methylation

- Data normalisation

- Statistical analysis and bioinformatics

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

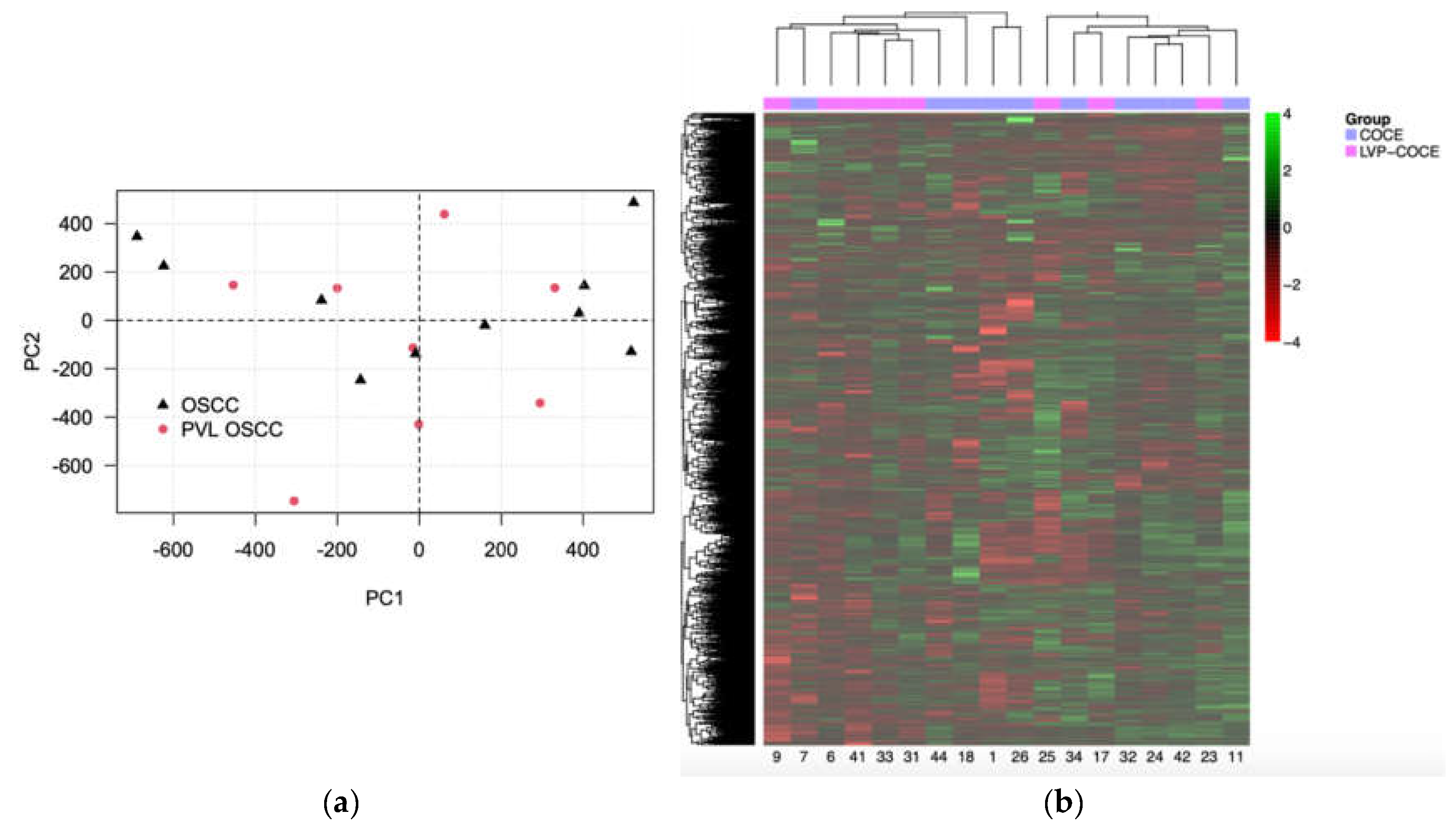

3.2. The Unsupervised Exploratory Analysis did Not Allow to Differentiate Between the Different Oral Cancer Groups

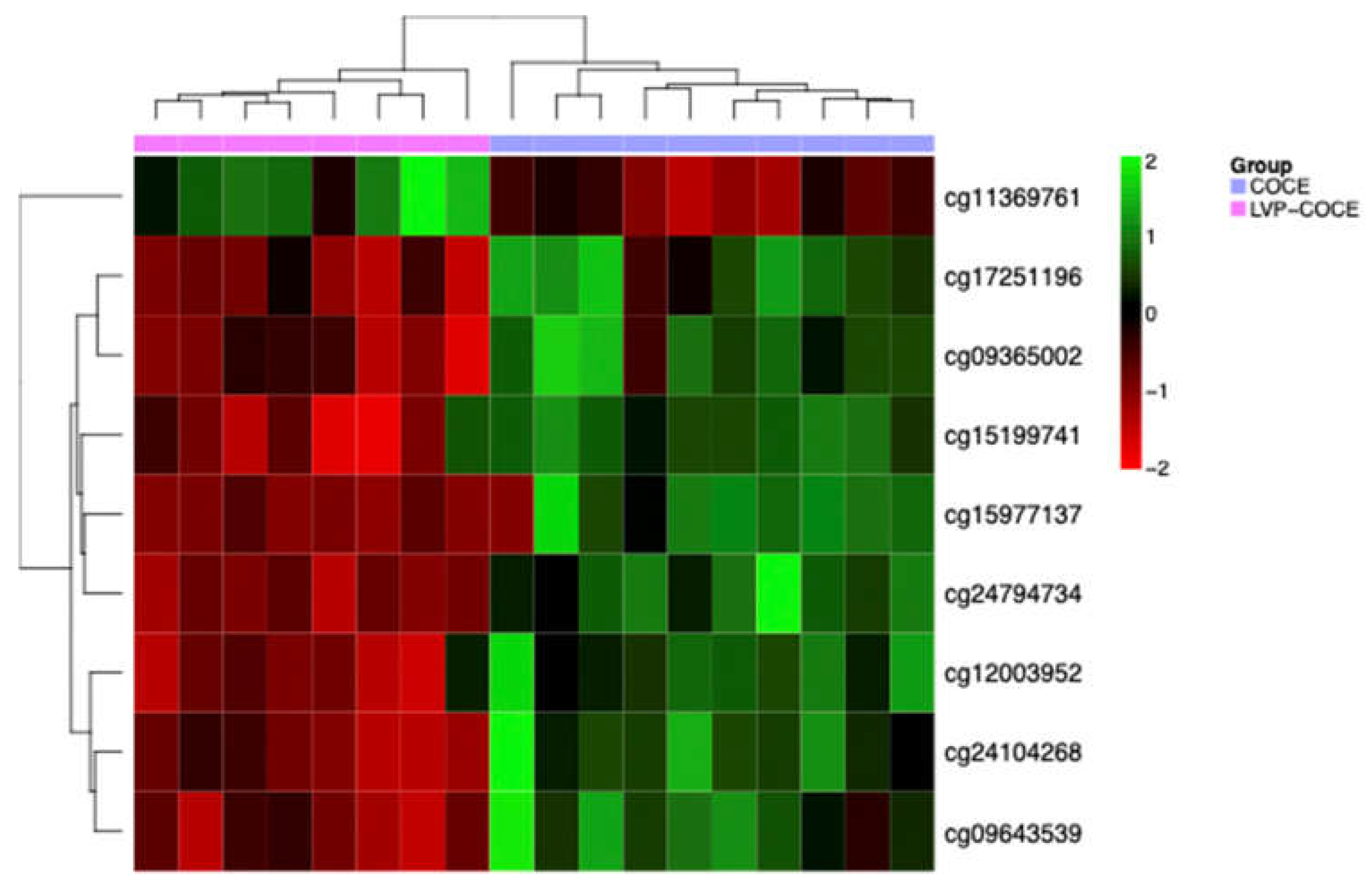

3.3. Identification of Differentially Methylated CpG Sites

| MethylationEPIC probe ID | Gene symbol | Cytoband | ∆β | Relation to CpG island | Regulatory feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg24794734 | AGL | 1p21.2 | -0.007 | Shore | 1st Exon, 5’UTR, TSS1500 |

| cg11369761 | - | 0.12 | Shore | - | |

| cg15199741 | FGD5 | 3p25.1 | -0.09 | Open sea | Body |

| cg09643539 | ARL15 | 5q11.2 | -0.14 | Open sea | Body |

| cg09365002 | DAXX | 6p21.32 | -0.3 | Shore | Body |

| cg17251196 | -0.17 | Shore | Body | ||

| cg24104268 | - | -0.12 | Island | - | |

| cg12003952 | ZNF429 | 19p12 | -0.07 | Shore | TSS1500 |

| cg15977137 | WRB / GET1 | 21q22.2 | -0.16 | Shore | Body, 1st Exon, 5’UTR |

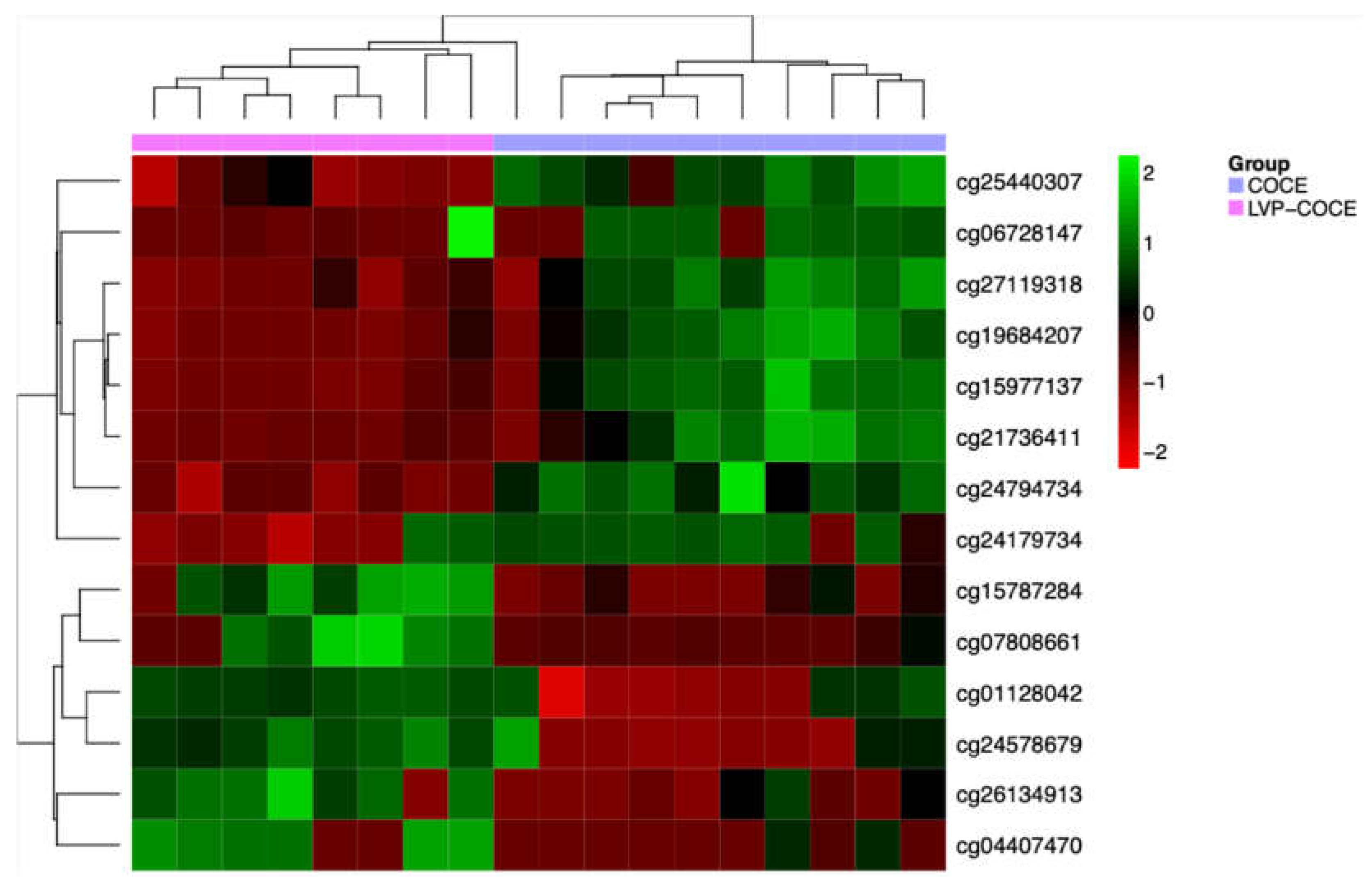

3.4. Identification of Potential DNA Methylation Biomarkers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warnakulasuriya S, Kujan O, Aguirre-Urizar JM, Bagan JV, González-Moles MÁ, Kerr AR, Lodi G, Mello FW, Monteiro L, Ogden GR, Sloan P, Johnson NW. Oral potentially malignant disorders: A consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2020, 00, 1 – 19. [CrossRef]

- Lafuente Ibáñez de Mendoza I, Lorenzo Pouso AI, Aguirre Urízar JM, Barba Montero C, Blanco Carrión A, Gándara Vila P, Pérez Sayáns M. Malignant development of proliferative verrucous/multifocal leukoplakia: A critical systematic review, meta-analysis and proposal of diagnostic criteria. J Oral Pathol Med. 2022, 51, 30 - 8.

- Ramos-García P, González-Moles MÁ, Mello FW, Bagan JV, Warnakulasuriya S. Malignant transformation of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 1896 - 907. [CrossRef]

- McParland H, Warnakulasuriya S. Lichenoid morphology could be an early feature of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021, 50, 229 - 35.

- Alkan U, Bachar G, Nachalon Y, Zlotogorsky A, Gal Levin E, Kaplan I. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a clinicopathological comparative study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022, 51, 1027 – 33. [CrossRef]

- Hansen LS, Olson JA, Silverman S Jr. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. A long-term study of thirty patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985, 60, 285 - 98.

- Villa A, Menon RS, Kerr AR, de Abreu-Alves F, Guollo A, Ojeda D, Woo SB. Proliferative leukoplakia: Proposed new clinical diagnostic criteria. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 749 – 760. [CrossRef]

- Bagan J, Murillo-Cortes J, Leopoldo-Rodado M, Sanchis-Bielsa JM, Bagan L. Oral cancer on the gingiva in patients with proliferative leukoplakia: A study of 30 cases. J Periodontol. 2019, 90, 1142 - 8. [CrossRef]

- Bagan JV, Jiménez-Soriano Y, Diaz-Fernandez JM, Murillo-Cortés J, Sanchis-Bielsa JM, Poveda-Roda R, Bagan L. Malignant transformation of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia to oral squamous cell carcinoma: a series of 55 cases. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 732 - 5. [CrossRef]

- Proaño-Haro A, Bagan L, Bagan JV. Recurrences following treatment of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021, 50, 820 - 8. [CrossRef]

- Leemans CR, Snijders PJF, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular landscape of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018; 18: 269 - 82.

- Chow LQM. Head and Neck Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 60 - 72.

- Supic G, Stefik D, Ivkovic N, Sami A, Zeljic K, Jovic S, Kozomara R, Vojvodic D, Stosic S. Prognostic impact of miR-34b/c DNA methylation, gene expression, and promoter polymorphism in HPV-negative oral squamous cell carcinomas. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 1296. [CrossRef]

- Bagan J, Sarrion G, Jimenez Y. Oral cancer: clinical features. Oral Oncol. 2010, 46, 414 - 7. [CrossRef]

- Sathyan K, Sailasree R, Jayasurya R, et al. Carcinoma of tongue and the buccal mucosa represent different biological subentities of the oral carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006, 132, 601 – 9. [CrossRef]

- Rautava J, Luukkaa M, Heikinheimo K, Alin J, Grenman R, Happonen RP. Squamous cell carcinomas arising from different types of oral epithelia differ in their tumor and patient characteristics and survival. Oral Oncol. 2007, 43, 911 - 9. [CrossRef]

- Hsu PJ, Yan K, Shi H, Izumchenko E, Agrawal N. Molecular biology of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2020, 102, 104552. [CrossRef]

- Okoturo EM, Risk JM, Schache AG, Shaw RJ, Boyd MT. Molecular pathogenesis of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a systematic review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 56, 780 - 5. [CrossRef]

- Llorens C, Soriano B, Trilla-Fuertes L, Bagan L, Ramos-Ruiz R, Gamez-Pozo A, Peña C, Bagan JV. Immune expression profile identification in a group of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia patients: a pre-cancer niche for oral squamous cell carcinoma development. Clin Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 2645 – 57. [CrossRef]

- Farah CS, Shearston K, Turner EC, Vacher M, Fox SA. Global gene expression profile of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and its underlying biological disease mechanisms. Oral Oncol. 2024, 151, 106737. [CrossRef]

- Flausino CS, Daniel FI, Modolo F. DNA methylation in oral squamous cell carcinoma: from its role in carcinogenesis to potential inhibitor drugs. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021, 164, 103399. [CrossRef]

- Soozangar N, SaEGDhi MR, Jeddi F, Somi MH, Shirmohamadi M, Samadi N. Comparison of genome-wide analysis techniques to DNA methylation analysis in human cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 3968 - 81. [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Pomares A, Llorens C, Soriano B, Bagan L, Moreno A, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Differentially methylated genes in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia reveal potential malignant biomarkers for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2021, 116, 105191. [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Pomares A, Hervás D, Bagan-Debon L, Proaño A, Garcia D, Sandoval J, Bagan J. Oral cancers preceded by proliferative verrucous leukoplakia exhibit distinctive molecular features. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 1072-83. [CrossRef]

- Okoturo E, Green D, Clarke K, Liloglou T, Boyd MT, Shaw RJ, Risk JM. Whole genome DNA methylation and mutational profiles identify novel changes in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2023, 135, 893 - 903. [CrossRef]

- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, Sullivan DC, Jessup JM, Brierley JD, Gaspar LE, Schilsky RL, Balch CM, Winchester DP, Asare EA, Madera M, Gress DM, Meyer LR (Eds.). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (8th edition). Springer International Publishing: American Joint Commission on Cancer; 2017.

- Pidsley R, Zotenko E, Peters TJ, Lawrence MG, Risbridger GP, Molloy P, Van Djik S, Muhlhausler B, Stirzaker C, Clark SJ. Critical evaluation of the Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarray for whole-genome DNA methylation profiling. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 208. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Laird PW, Shen H. Comprehensive characterization, annotation and innovative use of Infinium DNA methylation BeadChip probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e22. [CrossRef]

- Jaeckel, L A. Estimating regression coefficients by minimizing the dispersion of residuals. Ann Math Statist. 1972, 43, 1449 – 58. [CrossRef]

- Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010, 33, 1 - 22. [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Pomares A, Hervás D, Bagán L, Proaño A, Bagan J. Proliferative verrucous and homogeneous Leukoplakias exhibit differential methylation patterns. Oral Dis. 2024. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, Ramos-García P. Prognosis parameters of oral carcinomas developed in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Cancers. 2021, 13, 4843. [CrossRef]

- Faustino ISP, de Pauli Paglioni M, de Almeida Mariz BAL, Normando AGC, Pérez-de-Oliveira ME, Georgaki M, Nikitakis NG, Vargas PA, Santos-Silva AR, Lopes MA. Prognostic outcomes of oral squamous cell carcinoma derived from proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2022. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Lee DS, Ramirez RJ, Lee JJ, Valenzuela CV, Zevallos JP, Mazul AL, Puram SV, Doering MM, Pipkorn P, Jackson RS. Survival of young versus old patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: A meta-Analysis. Laryngoscope. 2021, 131, 1310 – 19. [CrossRef]

- Sumioka S, Sawai NY, Kishino M, Ishihama K, Minami M, Okura M. Risk factors for distant metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013, 71, 1291 - 7. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan D. Hallmarks of cancer: New dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31 - 46. [CrossRef]

- Tsai HC, Baylin SB. Cancer epigenetics: linking basic biology to clinical medicine. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 502 – 17. [CrossRef]

- Jithesh PV, Risk JM, Schache AG, Dhanda J, Lane B, Liloglou T, Shaw RJ. The epigenetic landscape of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013, 108, 370 - 9. [CrossRef]

- Milutin Gašperov N, Sabol I, Božinović K, Dediol E, Mravak-Stipetić M, Licastro D, Dal Monego S, Grce M. DNA methylome distinguishes head and neck cancer from potentially malignant oral lesions and healthy oral mucosa. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 6853. [CrossRef]

- Simo-Riudalbas L, Diaz-Lagares A, Gatto S, Gagliardi M, Crujeiras AB, Matarazzo MR, Esteller M, Sandoval J. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis identifies novel hypomethylated non-pericentromeric genes with potential clinical implications in ICF Syndrome. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0132517. [CrossRef]

- Shi TY, He J, Wang MY, Zhu ML, Yu KD, Shao ZM, Sun MH, Wu X, Cheng X, Wei Q. CASP7 variants modify susceptibility to cervical cancer in Chinese women. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 9225.

- Contreras-Romero C, Pérez-Yépez EA, Martinez-Gutierrez AD, Campos-Parra A, Zentella-Dehesa A, Jacobo-Herrera N, López-Camarillo C, Corredor-Alonso G, Martínez-Coronel J, Rodríguez-Dorantes M, de León DC, Pérez-Plasencia C. Gene promoter-methylation signature as biomarker to predict cisplatin-radiotherapy sensitivity in locally advanced cervical cancer. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 773438. [CrossRef]

- Senchenko VN, Kisseljova NP, Ivanova TA, Dmitriev AA, Krasnov GS, Kudryavtseva AV, Panasenko GV, Tsitrin EB, Lerman MI, Kisseljov FL, Kashuba VI, Zabarovsky ER. Novel tumor suppressor candidates on chromosome 3 revealed by NotI-microarrays in cervical cancer. Epigenetics. 2013, 8, 409 - 20.

- Shen J, LeFave C, Sirosh I, Siegel AB, Tycko B, Santella RM. Integrative epigenomic and genomic filtering for methylation markers in hepatocellular carcinomas. BMC Med Genomics. 2015, 8, 28. [CrossRef]

- Brito C, Costa-Silva B, Barral DC, Pojo M. Unraveling the relevance of ARL GTPases in cutaneous melanoma prognosis through integrated bioinformatics analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 9260. [CrossRef]

- Rauch TA, Wang Z, Wu X, Kernstine KH, Riggs AD, Pfeifer GP. DNA methylation biomarkers for lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2012, 33, 287 - 96. [CrossRef]

- Richmond CS, Oldenburg D, Dancik G, Meier DR, Weinhaus B, Theodorescu D, Guin S. Glycogen debranching enzyme (AGL) is a novel regulator of non-small cell lung cancer growth. Oncotarget. 2018, 9, 16718 - 30. [CrossRef]

- Jiang L, Lan L, Qiu Y, Lu W, Wang W, Huang Y. Target genes of N6-methyladenosine regulatory protein ALKBH5 are associated with prognosis of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2023, 15, 3228 - 36. [CrossRef]

- Kong K, Hu S, Yue J, Yang Z, Jabbour SK, Deng Y, Zhao B, Li F. Integrative genomic profiling reveals characteristics of lymph node metastasis in small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 295 - 311. [CrossRef]

- Horning AM, Awe JA, Wang CM, Liu J, Lai Z, Wang VY, Jadhav RR, Louie AD, Lin CL, Kroczak T, Chen Y, Jin VX, Abboud-Werner SL, Leach RJ, Hernandez J, Thompson IM, Saranchuk J, Drachenberg D, Chen CL, Mai S, Huang TH. DNA methylation screening of primary prostate tumors identifies SRD5A2 and CYP11A1 as candidate markers for assessing risk of biochemical recurrence. Prostate. 2015, 75, 1790 - 801.

- Wang L, Shi J, Huang Y, Liu S, Zhang J, Ding H, Yang J, Chen Z. A six-gene prognostic model predicts overall survival in bladder cancer patients. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 229. [CrossRef]

- Heyliger SO, Soliman KFA, Saulsbury MD, Reams RR. The identification of Zinc-Finger Protein 433 as a possible prognostic biomarker for clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Biomolecules. 2021, 11, 1193. [CrossRef]

- Vargas AC, Gray LA, White CL, Maclean FM, Grimison P, Ardakani NM, Bonar F, Algar EM, Cheah AL, Russell P, Mahar A, Gill AJ. Genome wide methylation profiling of selected matched soft tissue sarcomas identifies methylation changes in metastatic and recurrent disease. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 667. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud I, Liao D. DAXX in cancer: phenomena, processes, mechanisms and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47: 7734 - 52. [CrossRef]

- Brunetti D, Catania A, Viscomi C, Deleidi M, Bindoff LA, Ghezzi D, Zeviani M. Role of PITRM1 in mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroEGDeneration. Biomedicines. 2021, 9, 833.

- Endo Y, Horinishi A, Vorgerd M, Aoyama Y, Ebara T, Murase T, Odawara M, Podskarbi T, Shin YS, Okubo M. Molecular analysis of the AGL gene: heterogeneity of mutations in patients with glycogen storage disease type III from Germany, Canada, Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey. J Hum Genet. 2006, 51, 958 - 63. [CrossRef]

- Weinhaus B, Guin S. Involvement of glycogen debranching enzyme in bladder cancer. Biomed Rep. 2017, 6, 595 - 8. [CrossRef]

- Plotnikov D, Pärssinen O, Williams C, Atan D, Guggenheim JA. Commonly occurring genetic polymorphisms with a major impact on the risk of nonsyndromic strabismus: replication in a sample from Finland. J AAPOS. 2021: S1091-8531(21)00617-0. [CrossRef]

- Pandey AK, Saxena A, Dey SK, Kanjilal M, Kumar U, Thelma BK. Correlation between an intronic SNP genotype and ARL15 level in rheumatoid arthritis. J Genet. 2021, 100, 26. [CrossRef]

- Brito C, Costa-Silva B, Barral DC, Pojo M. Unraveling the relevance of ARL GTPases in cutaneous melanoma prognosis through integrated bioinformatics analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 9260. [CrossRef]

| OSCC-PVL | cOSCC | p | ||

| Number of cases (%) | 8 | 10 | ||

| Mean age ± SD (Years) | 80,25 ± 12,42 | 72,8 ± 9,05 | p = 0,062 | |

| Gender (%) | Female | 6 (75) | 6 (60) | p > 0,05 |

| Male | 2 (25) | 4 (40) | ||

| Tobacco (%) | Yes | 1 (12,5) | 4 (40) | p > 0,05 |

| No | 7 (87,5) | 6 (60) | ||

| Alcohol (%) | Yes | 0 | 1 (10) | p > 0,05 |

| No | 8 (100) | 9 (90) | ||

| Tumour site (%) | Gingiva | 5 (62,5) | 3 (30) | p > 0,05 |

| Palate | 2 (25) | 1 (10) | ||

| Floor of the mouth | 1 (10) | |||

| Tongue | 4 (40) | |||

| Buccal mucosa | 1 (12,5) | |||

| Lips | 1 (10) | |||

| Clinical form of the neoplastic lesion (%) | Erythroplastic | 2 (25) | p = 0,022 | |

| Ulceration | 1 (12,5) | 9 (90) | ||

| Exophytic | 3 (37,5) | |||

| Mixed | 2 (25) | 1 (10) | ||

| Tumour grade (%) | G0 | 2 (25) | p > 0,05 | |

| G1 | 4 (50) | 5 (50) | ||

| G2 | 1 (12,5) | 4 (40) | ||

| G3 | 1 (12,5) | 1 (10) | ||

| Cancer infiltration (%) | Bone | 3 (37,5) | 3 (30) | p > 0,05 |

| Perineural | 2 (25) | 7 (70) | p = 0,058 | |

| Lymphovascular | 2 (25) | 2 (20) | p = 0,8 | |

| DOI (mm) | Median (± SD) | 3,62 ± 2,21 | 6,39 ± 2,18 | p = 0,075 |

| Metastasis (%) | Cervical lymph nodes | 1 (12,5) | 3 (30) | p > 0,05 |

| Distant metastases | 0 | 1 (10) | ||

| TNM stage (%) | I | 1 (12,5) | 2 (20) | p > 0,05 |

| II | 3 (37,5) | 2 (20) | ||

| III | 1 (12,5) | |||

| IV | 3 (37,5) | 6 (60) | ||

| Second primary tumours (%) | Yes | 4 (50) | 2 (20) | p = 0,18 |

| No | 4 (50) | 8 (80) | ||

| MethylationEPIC probe ID | Gene symbol | Cytoband | ∆β | Relation to CpG island | Regulatory feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg24794734 | AGL | 1p21.2 | -0.007 | Shore | 1st Exon, 5’UTR, TSS1500 |

| cg24179734 | BRD9 | 5p15.33 | -0.3 | Shore | Body |

| cg04407470 | NR2E1 | 6q21 | 0.49 | Island | Body |

| cg25440307 | ZNF777 | 7q36.1 | -0.019 | Island | Body |

| cg06728147 | PITRM1 | 10p15.2 | -0.47 | Open sea | Body |

| cg01128042 | CASP7 | 10q25.3 | 0.35 | Open sea | Body |

| cg26134913 | - | 0.32 | Shore | - | |

| cg24578679 | CYP11A1 | 15q24.1 | 0.25 | Island | Body, TSS200 |

| cg07808661 | C18orf18 | 18p11.31 | 0.27 | Island | Body, TSS200 |

| cg15787284 | ZNF433 | 19p13.2 | 0.28 | Island | TSS200 |

| cg27119318 | WRB / GET1 | 21q22.2 | -0.19 | Shore | Body, TSS200 |

| cg21736411 | -0.08 | Shore | Body, TSS200 | ||

| cg19684207 | -0.18 | Shore | Body, TSS200 | ||

| cg15977137 | -0.16 | Shore | Body, 1st Exon, 5’UTR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).