1. Introduction

The use of automated tools like web crawlers, search engines, annotation and editing software, and Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) applications is on the rise among Humanities researchers, particularly among palaeographers, linguists and historians. Of these tools, HTR has emerged as a subject of particular interest and systematic investigation. Scholars such as Nockels et al. (2022), Terras (2022), Aiello and Simeone (2019), Humbel and Nyhan (2019), Houghton (2019), Toselli et al. (2018), Romero et al. (2013), Leiva et al. (2011), and others have examined the challenges and implications of implementing HTR in scholarly editions.

In the universe of Portuguese Humanities, research on the use of automatic manuscript reading for scholarly editions has not been as prolific as for other languages. If we take into consideration the relevance of research into specific languages and scripts for the training and development of HTR methodology (cf.

Transkribus – exceptional projects

1), further research into Portuguese manuscripts is a desirable aim. Some pioneer projects are remarkable – in particular, the project developed by the research group

Memória em Papel since 2021 at the Federal University of Bahia, led by prof. Lívia Borges Souza Magalhães and prof. Lucia Furquim Werneck Xavier with the general coordination of prof. Alícia Duhá Lose, which aimed at the preparation of a reading and research database and a network for the subsequent mass transcription and online editing of archival documents

2 – but the area could still benefit from further research

3.

In order to investigate and explore the challenges presented by the automated recognition of non-contemporary Portuguese manuscripts, this paper presents the results of an experiment using HTR applications for late 16th-century Portuguese Inquisition manuscripts and discussing them in qualitative and quantitative terms, comparing them with human-made full diplomatic transcriptions. The Fond of the Portuguese Inquisition, housed in the Portuguese National Archives at Torre do Tombo (Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo - ANTT), consists of a vast digital repository of 83,294 items. This collection includes 3,004 books and 79,337 records, covering an extensive period from 1536 to 1821 (cf. Portugal, 2011). Recognized as one of the most important collections within the Hispanic sphere, its historical significance is unparalleled (cf. Marcocci, 2010, among others). The Fond serves as a crucial resource for a wide range of research endeavors focusing on the history of Portugal, as well as its Atlantic and Eastern domains during the Early Modern period and on Portuguese Historical Linguistics.

From a Digital Humanities perspective, the present experiment involved an interdisciplinary team, made up of researchers who have been working for many years in Computational Linguistics, Historical Linguistics, Philology and Palaeography, to build a methodology to investigate the HTR technology and how Linguistics, Philology and Palaeography can contribute to its development and, at the same time, benefit from it. The proposal of this experiment is to contribute to the refinement of HTR tools by providing a fine palaeographic analysis of the machine's errors and successes in transcription. To the best of our knowledge, this work perspective is unprecedented for the Portuguese language. Another original contribution of the experiment is to test a Brazilian HTR tool.

In the paper, we observe the behavior of two HTR tools,

Transkribus4 and

Lapelinc Transcriptor5, and find that the automatic recognition of historical manuscript text depends fundamentally on the academic work linked to Palaeography and its techniques that guide and ground the activities and parameters of historical manuscript transcription used in the construction, training and use of an HTR tool, because what the machine learns are the patterns and consistencies of the text interpreted by human reading. The consequences of this observation will also be discussed throughout this paper.

Thus, this paper presents three sections in addition to this introduction: in 2. Challenges in automatic recognition of non-contemporary handwritten texts: an experiment with HTR we present the materials and methods used in the experiment; in 3. The computational and the palaeographical perspectives: evaluating results we show the experiment results; finally in 4. Final Remarks we conclude with some hypotheses about the relation of HTR technology and Philology.

2. Challenges in Automatic Recognition of Non-Contemporary Handwritten Texts: An Experiment with HTR

HTR aims to recognize handwriting and transform handwritten text images into machine-readable text. It is an active research area in computer science, having its emergence in the 1950s (Dimond, 1957). Its origin was initially aligned with the development of optical character recognition (OCR) technology, where scanned images of printed text are converted into pure, machine-readable plain text (Muehlberger et al., 2019). But due to specificities of handwritten texts, such as different penmanships and conservation conditions of archival documents — to give only a couple of examples, the development of HTR tools has become a different avenue of search than OCR becoming an independent area of research.

Advances in the use of statistical calculations, such as the Hidden Markov Model, have brought great and important improvements in terms of accuracy in the construction of handwriting recognition software. However, these techniques were not robust enough for the diversity and complexity of handwriting. Only from the machine learning techniques, the necessary precision for the HTR was reached (Vaidya, Trivedi, Satra, Pimpale, 2018).

Several authors point out that HTR brings important research possibilities, specifically regarding historical manuscripts. (Oliveira, Seguin, Kaplan, 2019). According to Kang et al. (2019):

Transforming images of handwritten text into machine readable format has an important amount of application scenarios, such as historical documents, mail-room processing, administrative documents, etc. But the inherent high variability of handwritten text, the myriad of different writing styles and the amount of different languages and scripts, make HTR an open research problem that is still challenging.

HTR technology can currently be considered a mature machine learning tool and can generate machine-processable texts from historical manuscript images. This allows its use by libraries and archives, reducing transcription time from documentary sources. This decreases the cost of searching on texts as well as scale analysis (Nockels et al. 2022). Terras (2022) states:

The automatic generation of accurate, machine-readable transcriptions of digital images of handwritten material has long been an ideal of both researchers and institutions, and it is understood that with successful Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) the next generation of digitized manuscripts promises to yet again extend and revolutionize the study of historical handwritten documents.

In this regard, we wish to highlight two relevant aspects:

(1) HTR is a complex task from the computational point of view; it has been in development since the 1970s, with a lot of investment due to its wide range of applicabilities; but only recently the progress has been considerable.

(2) HTR via machine learning in general depends on human reading models, aided or not by automatic linguistic analysis, to develop its accuracy.

Several authors have been pointing to the important possibilities opened by HTR for humanities research, in particular as regards historical manuscripts. However, at present, it can be safely said that the potential of HTR for any area interested in historical manuscript is an open question. Our experiment is an investigation into this perspective.

2.1. The Experiment

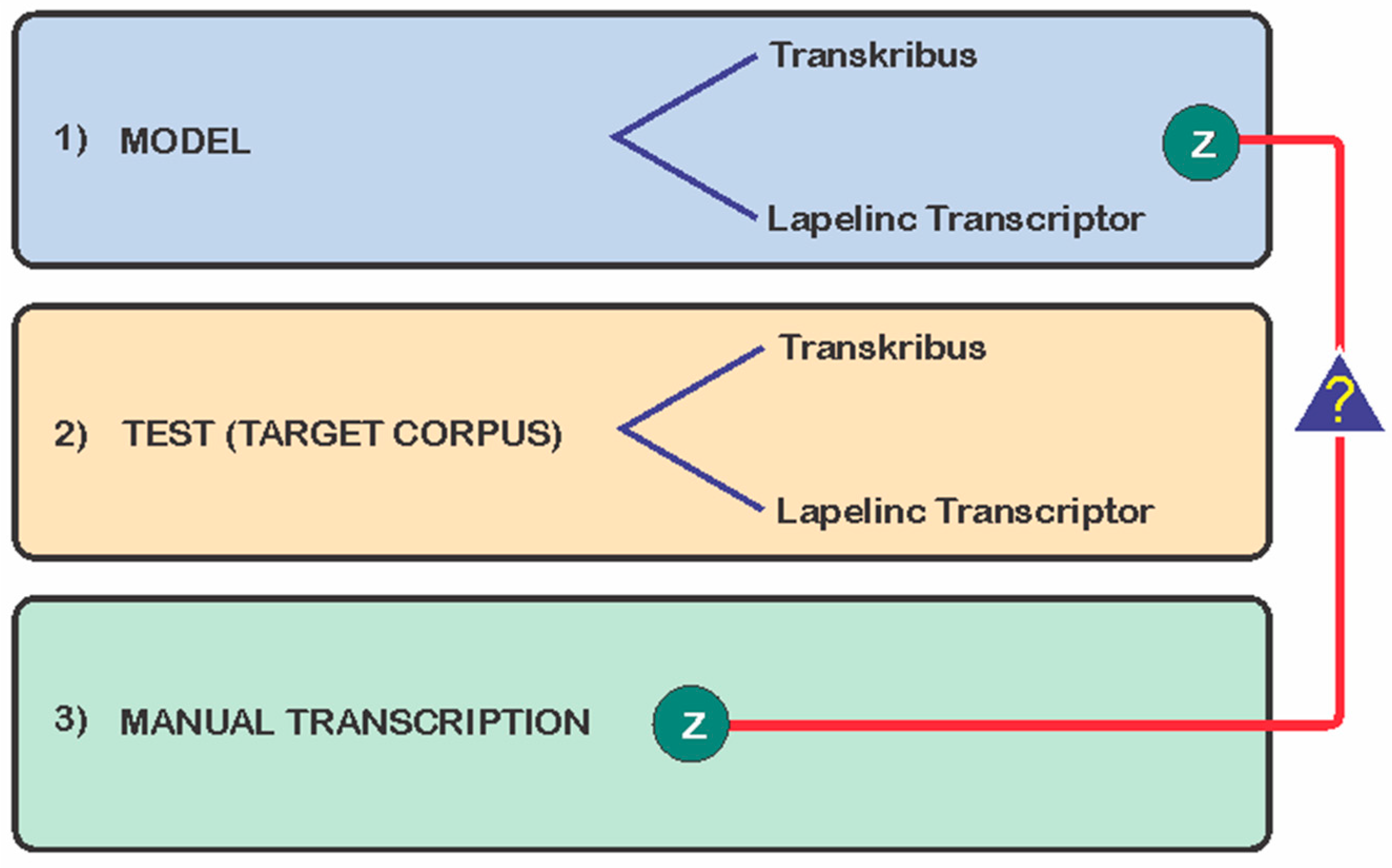

The experiment consists of a in depth comparison between human-made conservative transcriptions of the manuscripts and the outputs of automated text recognition of the same documents, aiming to test the accuracy of automated recognition and, more importantly, to identify the difficulties faced by the selected software applications. Thus, as illustrated in

Figure 1, the experiment involved:

- (1)

the construction of two HTR models (one in the Transkribus tool and the other in the LAPELINC TANSCRIPTOR tool) with the same training base (a model corpus);

- (2)

the application of these models on a target corpus for test, with documents that were not in the model corpus;

- (3)

the manual transcription of the documents to evaluate the result of the automatic recognition performed by each of the tools against the human recognition.

The transcription of the base corpus for training the models (the model corpus) was performed following the same transcription criteria (Z) used in the manual transcription of the evaluation corpus (target corpus) to test the accuracy of automated recognition and, more importantly, to identify the difficulties faced by the selected software applications using a meticulous comparison between human-made conservative transcriptions of the manuscripts and the outputs of automated text recognition of the same documents, indicated in the figure by “?”.

For the purpose of this experiment, we selected a group of manuscripts produced in the late 16th century (1591-1595), during the first ‘

Visitações’ of the Portuguese Inquisition

6 to Brazil. All the documents are in digital facsimile format, available at ANTT (PORTUGAL, 2011) and are part of research project ‘

Mulheres na América Portuguesa’ – MAP (Women in Portuguese America). Since 2017, MAP has created a collection of more than 150 documents authored by or about women in Portuguese America. At present, the research team is compiling a Corpus that will feature the transcription of at least 30 inquisitorial processes from the first ‘

Visitações’ in philological editions. This experiment is a crucial aspect of Project MAP’s study on the palaeographic difficulties associated with the publication of this material.

The documents were written, in their greatest part, by one hand: the notary Manoel Francisco. Despite having minor parts written by other hands, only the folia of the documents produced by Manoel Francisco are used in the experiment, which are: Processo de Antónia de Barros

7, Processo de Guiomar Lopes

8, Denúncias contra Francisca Luís

9, Processo de Guiomar Piçarra

10, Processo de Maria Pinheira

11, Processo de D. Catarina Quaresma

12, Processo de Maria Álvares

13, Processo de Francisco Martins e Isabel de Lamas

14 e Processo de Felícia Tourinha

15. All these documents were edited by the researchers involved with Project MAP during their post-graduate and undergraduate research. Following the same rigorous criteria, all the transcriptions were revised as part of the experiment.

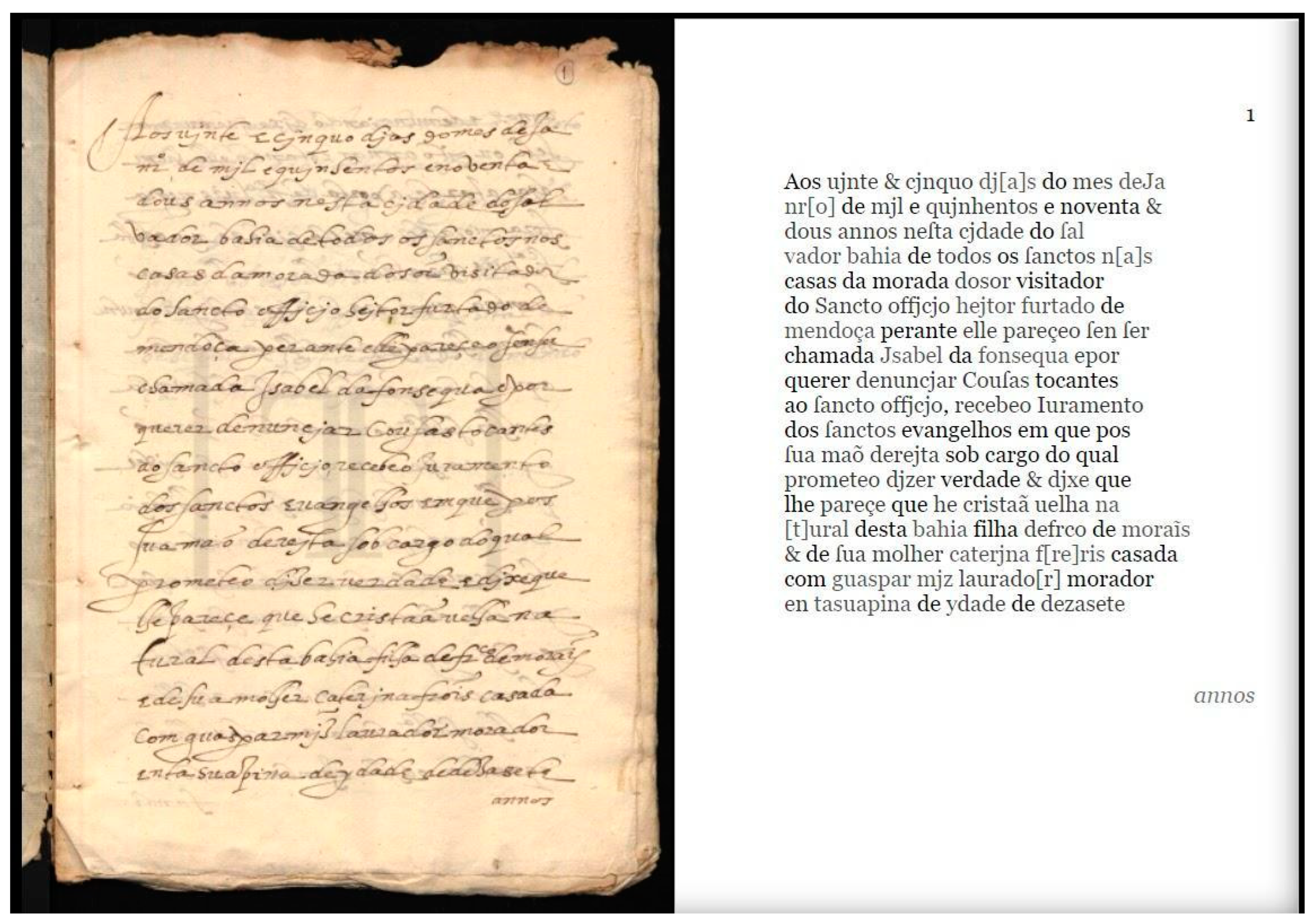

Figure 2 illustrates a digital version of part of the document ‘Denúncias contra Francisca Luís’

16 (on the left) and a digital edition of the same document (on the right), to give us an idea of the materiality of the manuscripts used in the experiment. We can also observe the high quality of this specific digitized image, which allows us to see a regular round letter, from Manoel Francisco’s hand, commonly associated with the italian or humanistic model of letter.

The software applications selected for this experiment are two independently developed HTR applications: Transkribus, and Lapelinc Transcriptor. The basis for our choice was the previous work and familiarity of parts of our team with each tool.

Transkribus is a comprehensive platform for scanning, text recognition and automated transcription of historical documents developed by ‘ReadCoop’, a European Cooperative Society (Muehlberger et al., 2019). It is a widely used software, whose development started in 2016, and is already very stable and well-known. In this platform, there is a base for Portuguese language training, as a result of the pioneering initiative of Lucia Xavier and Livia Magalhães in developing models for the Portuguese language since 2018 (Magalhães and Xavier, 2021; Magalhães, 2021).

Lapelinc Transcriptor is a software for palaeographic transcription in development in the Corpus Linguistics Research Lab (LaPeLinC), at the State University of Southwest Bahia, Brazil. The LaPeLinC team has been developing methods, tools and apparatus for corpus construction since 2009, at the cited university, under coordination of professors Santos and Namiuti (2009). The Transcriptor has been under development since 2019 (Costa et al., 2021) as one of the tools designed for the LaPeLinC framework for corpora building (Costa, Santos and Namiuti, 2022).

Both applications offer interfaces that allow very advanced visualization and manipulation of digital facsimiles. As both tools use machine learning technology, a specific HTR model for Manoel Francisco’s handwriting is produced with each one.

2.2. Procedures

Before running the experiment, it was necessary to prepare the reference corpora. Thus, the edited and revised documents were organized into two basic groups:

The model corpus used 6 inquisitorial processes, which are listed in

Table 1. The amounts of pages, digital images and “words” (or tokens) for each process are detailed in the table. Such documents totalized 72 digital pages/folios, 1.390 lines and 8.349 tokens. The Target corpus comprised 3 documents as shown in

Table 2. Such documents totalized 15 digital pages/folios, 415 lines and 2.645 tokens. As only integrally written folios by Manoel Francisco were considered, not all folia from the processes were used in the experiment.

All documents — the model corpus and the target corpus — were fully edited by our team, manually, with the same rigorous philological criteria, before the automatic part of the experiment took place. This transcription follows the criteria of minimum interference: abbreviations are not expanded and graphic segmentation is preserved (cf. Toledo Neto, 2020). Additionally, all transcriptions were proofread.

Our ‘target corpus’, or the corpus that we selected to evaluate the results in quantitative and qualitative exams, is composed of three manuscripts that were NOT given to the applications when they were building the model, as we mentioned before.

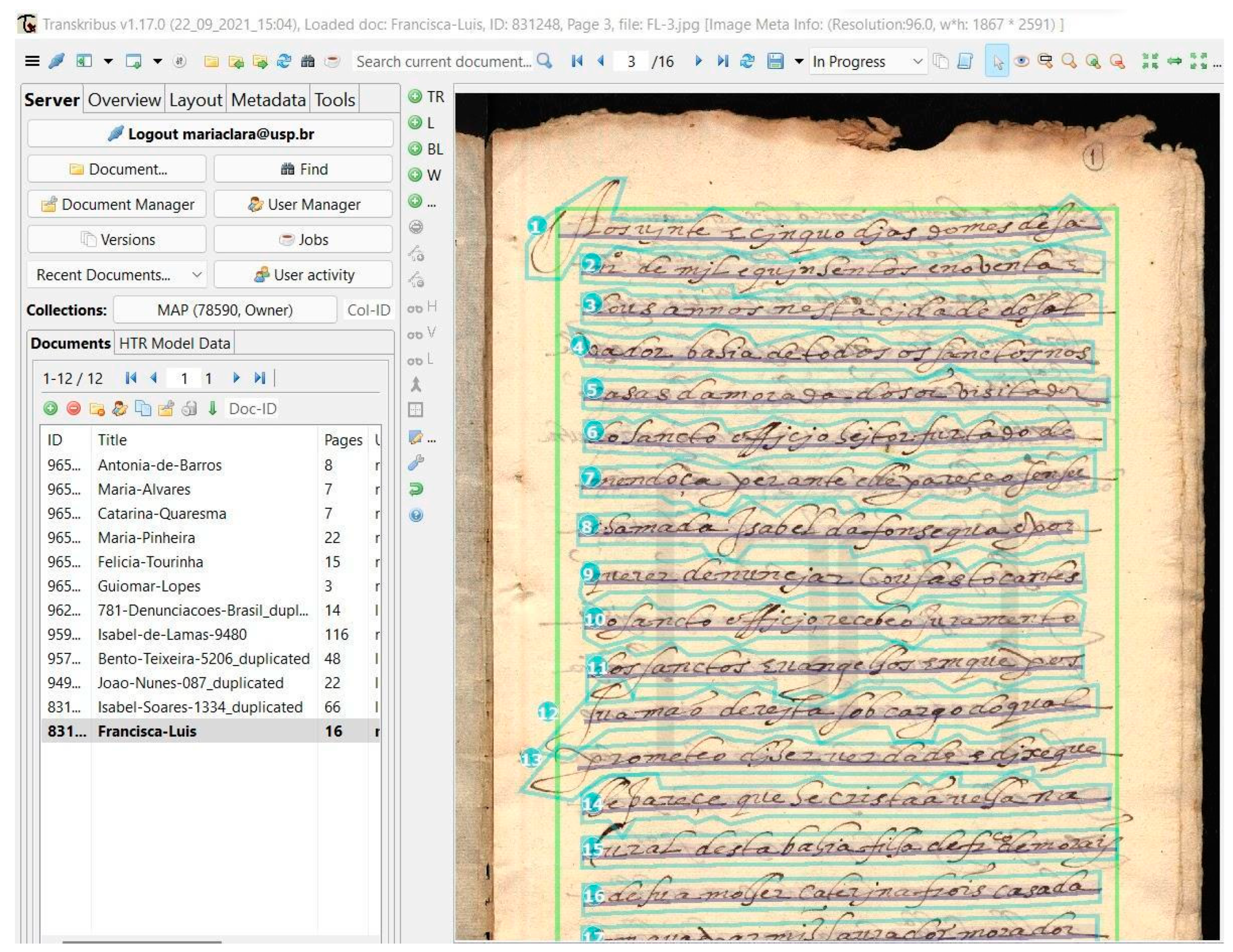

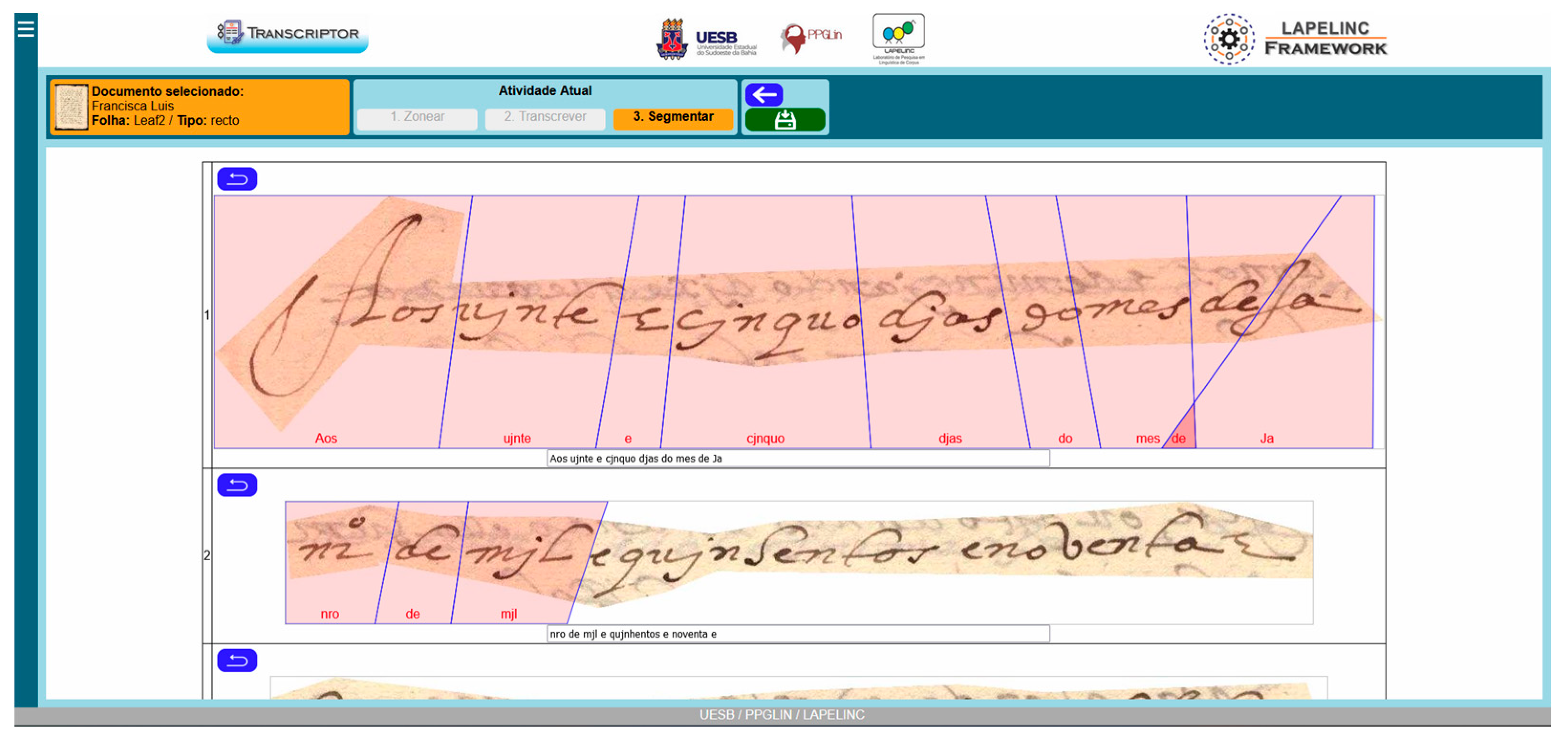

The experiment begins with the modeling phase, which aims to create a database for the Machine Learning strategies used by each software. It is in this phase that parameters are adjusted to allow the recognition of the writing of each hand analyzed, using a set of documents previously transcribed by humans. Both Lapelinc Transcriptor and Transkribus adopted similar paths for the creation of the model, consisting of three major stages:

1. Image mapping – when the image is segmented areas of text to be considered by the model;

2. Provision of reference transcription – a human-made reference transcription is provided for the text zones marked at the previous stage;

3. Training the model – the Machine Learning algorithms of each software are run, reading the image of the handwritten text and the reference transcription to perform internal adjustments.

Figure 3 shows the environment of the

Transkribus software in the image mapping phase and the provision of the reference transcription.

Figure 4 shows the environment of the LaPeLinC Framework Transcriptor software in the segmentation alignment phase.

Transkribus measures the accuracy of the model via Character Error Rate, defined as follows in READ-COOP (2021):

The Character Error Rate (CER) compares, for a given page, the total number of characters (n), including spaces, to the minimum number of insertions (i), substitutions (s) and deletions (d) of characters that are required to obtain the Ground Truth result (READ-COOP, 2021).

The formula to calculate CER

17 is according to Equation 1.

Transkribus also offers a rate for a ‘validation corpus’, which is a subset of the model corpus, that the tool selects randomly, to initially test the model. In our case we set the validation for 5% of the model corpus. The accuracy for the model when reading this validation corpus was 5.15%. We are not very interested in this rate, as we consider the validation set too small and not very well chosen by the software (two pages, each with only half the lines used; two final parts of the manuscripts, with too many abbreviations). We are more interested in the rate we calculated on the target corpus, to follow.

The

Lapelinc Transcriptor internally evaluates the accuracy of the model differently, using Equation 2 to perform this task:

where ∆

char is the number of read errors between the characters of the text read by humans and the one generated by the program and

char the total number of characters.

From Equations 1 and 2, the softwares presented the accuracy data presented in

Table 3, according to the internal calculation of each of them. The CER in

Transkribus, calculated by itself, was 0.97%. In other words, the accuracy rate was 99.03%. The error rate for the modeling in

Lapelinc Transcriptor, reported by the tool, was 7.69%. To rephrase, the accuracy rate was 92.41%, as shown in

Table 3.

After the application of the models, we had the target corpus documents in different versions, which we will examine closer later on:

1) Automatic transcriptions, as immediate results from the application:

-

- a)

The automatic transcription by Transkribus, produced with the model run in the model corpus;

- b)

The automatic transcription by Lapelinc Transcriptor, produced with the model run in the model corpus;

2) Manual transcriptions, previously elaborated by us, following the same criteria used in the model corpus.

The final task of the experiment was to evaluate how well the tools transcribed the target corpus, comparing the automatic transcriptions to our manual transcriptions.

3. The Computational and the Palaeographical Perspectives: Evaluating Results

The results from the experiment will be presented both from the computational and from the palaeographical perspectives. Let’s start with a broad view of the results in numbers.

To measure the accuracy of the results, we compared the ‘readings’ provided by the softwares with our own manual transcriptions of the same manuscripts. The central idea was to compare each of the automatic transcriptions with our human-made transcriptions to identify the sort of difficulties faced by the selected software applications.In order to make this comparison, we had to build an independent method, because the applications do not offer to the same extent comprehensive comparative analyses that could let us clearly see the differences between the human transcription and the machine transcriptions. All the tools give us are numeric rates, which are not our main interest.

Therefore, as an auxiliary tool to compare the results of the two HTR applications, we used an independent tool — DIFFCHECKER, which makes comparisons at character level and counts them, showing them side-by-side in a way that facilitates the exam. DIFFCHECKER is not a free tool, but we used it because it can conduct comparisons on the character level (not only on word level).

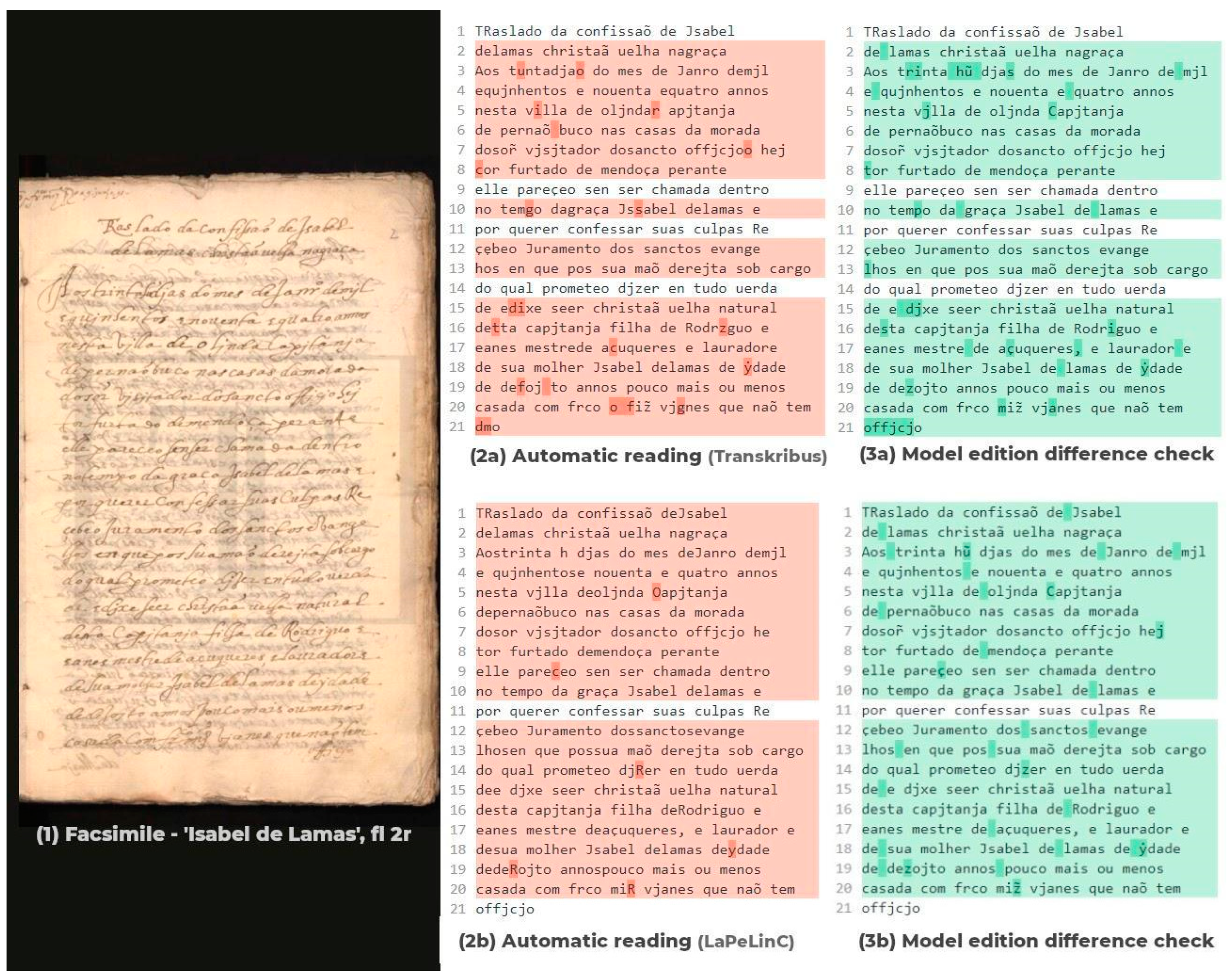

To sum up, the material we had in hand to measure and analyze the differences between the computational and manual transcriptions was, for each of the three processes that constitute our target corpus, (1) the original facsimile; (2) an automatic transcription by (a)

Transkribus and an automatic transcription by (b)

Lapelinc Transcriptor ; (3) a previously prepared manual transcription, compared with each of the automatic transcriptions in DIFFCHECKER.

Figure 5 shows this set of materials for the Process of Isabel de Lamas, to illustrate this part of the experiment.

With this system, the differences were counted and then analyzed by us one by one, with the results described in 3.1 to follow.

The advantage of calculating the rate ourselves in this very primary and simple way was that we can be sure the same parameters were used to evaluate the results of the two independent tools — as the estimations were done outside the environment of the tools, and by ourselves. First we calculated the difference rate from what the tool shows as ‘additions’ and ‘removals’. Whitespace was counted as a character. In this case, for every difference in a character, we counted one mistake. In each case, we subtracted the lower value from the higher value, then subtracted this differential from the higher value. In other words, always the higher value (additions or removals) was considered as the number of differences. We then stipulated a rate of difference formed by the number of differences per number of characters in the human-made reference transcription, times 100:

This is close to what we understand the Transkribus guidelines in the equations (1) and (2) further above, and (3) above. Ours is a simpler version, but is close enough for our purposes (which are mainly having a consistent ruler to measure two different applications). We supplement this heuristic approach with data directly obtained from the softwares.

As we said before, any and all differences between the automatic transcriptions and the manual transcriptions are computed in our experiment — this includes any character change, deletion or addition, remembering that for the computer, a whitespace is interpreted as a character.

This means that the rates we discussed this far reflect three basic types of differences between manual and automatic transcriptions: Different character readings; Different segmentations (be it over- or under-segmentation); Missing or added characters.

It is important to stress that, as with any other assessment of ‘errors’ committed by the automatic ‘readings’, we are not actually measuring ‘mistakes’ by the machine, but actually differences between the machine transcription and the human transcription.

What the machine actually learns are the patterns and consistencies of the text as interpreted by the human reading, i.e. the human-made model transcription, that serves as a reference and as a model to machine learning.

All we can say is how different one is from the other. This is important because, of course, the quality of the automatic transcription is strongly dependent on the quality of the manual transcription. This should be obvious but we don’t see it stressed enough. We will come back to that later.

3.1. Difference Rates Between Computational and Human-Made Transcriptions

The tables bellows show the difference rates between the automatic transcriptions rendered by each of the tools tested in the experiment and the manual transcription prepared by our team, for each of the three manuscripts involved in the experiment and as a general rate for all the manuscripts.

Table 5 shows this for the

Transkribus results, and

Table 6 shows this for

Lapelinc Transcriptor. Both tables will be extensively referred to with detail in what is to follow in 3.2.

3.2. Palaeographic Analysis

The most important part of the evaluation, for us, is our detailed analysis of the blunt automatic results, from a palaeographic perspective. In this case, showing the precise points that challenged the automatic recognition, such as word segmentation, individualized/stylized handwriting, abbreviations, material blotches, and other idiosyncratic or systematic graphic features of the documents. This analysis was focused on the three manuscripts in the examination corpus, in close comparison with their human-made transcriptions (i.e., the editions that were produced manually by us before the experiment, following rigorous philological norms), which we consider as our reference.

Our general aim was to find out: At which points did the automatic transcription find substantial, repetitive challenges, and could those challenges be understood from a palaeographic perspective? We hope these data may contribute to further development of the use of computational methods in the field of Portuguese palaeography.

Palaeographic Analysis: Opening Protocol

We will start by analyzing the first folio, which corresponds to 19 to 23 lines of text from the three processes that constitute our target corpus, i.e., that were automatically transcripted by both softwares after the training phase, compared to the same first 20 to 23 lines of previously human-made transcriptions of the same documents. This choice is made due to the formulaic nature of the starting section of the documents, which favors repetition of some interesting patterns.

Before presenting the transcriptions prepared by our research group, it is fundamental to outline the guidelines followed in the same. According to the terminology in Portuguese philology, the type of edition we carried out can be called a ‘diplomatic’ edition or even a ‘paleographic’ edition (cf. Duarte, 1997), which coincides with the type of edition generated by HTR software. First, we do not expand abbreviations, limiting ourselves to transcribing any signs used to mark them in the original, such as periods. We respect the use of uppercase and lowercase letters, not capitalizing, for example, place names and personal names, which were commonly written with lowercase initials at the time.

Furthermore, we tried to faithfully maintain the segmentation of Manoel Francisco's handwriting, even though it was quite challenging to establish criteria for such a decision. We based ourselves on the morphology of the graphemes to decide whether a final grapheme of a word had its stroke finished independently of the stroke of the initial grapheme of the following word. In cases where the quill was not lifted to start the stroke of the initial grapheme of the next word, it was considered that there was under-segmentation, that is, the absence of a graphic space between morphological words.

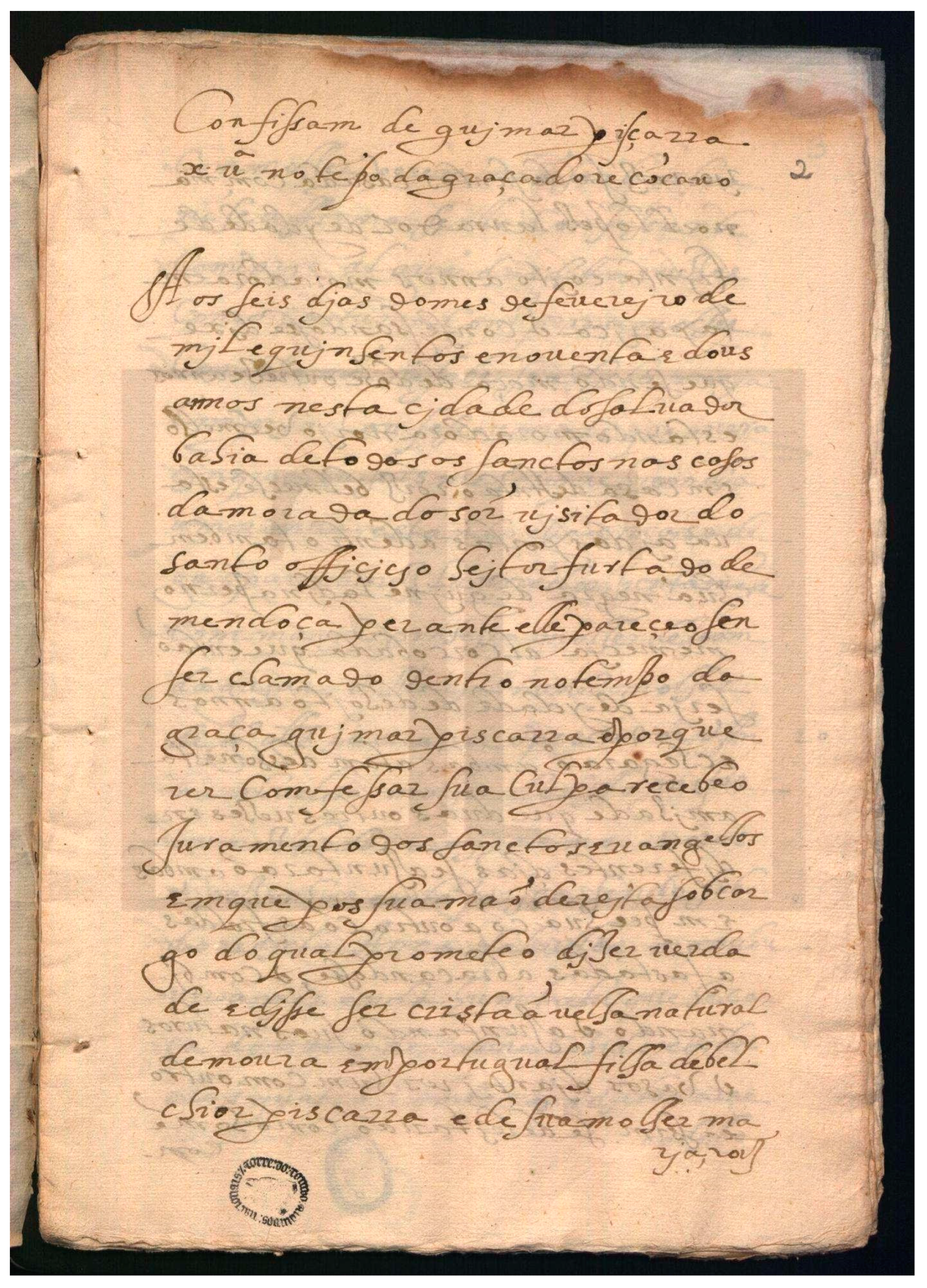

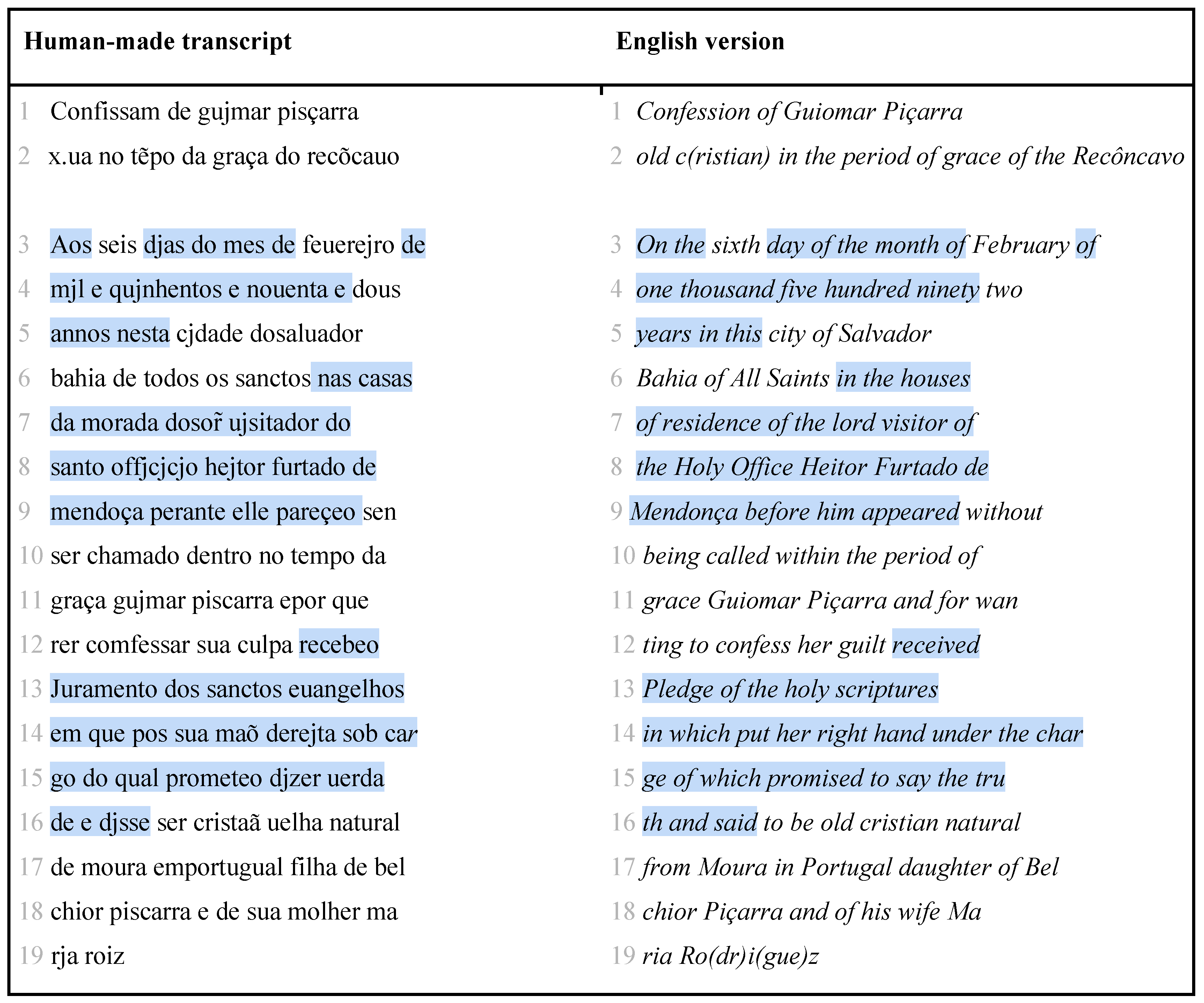

The opening protocol for the documents is illustrated here by the ‘Process of Guiomar Piçarra’;

Figure 6 shows the relevant folio, 2r, and

Figure 7 brings the opening protocol present in lines 1 to 19; our human-made transcription in the first column, and an English translation in the second column, with highlights on the elements that can be considered formulaic, i.e., always present in all manuscripts.

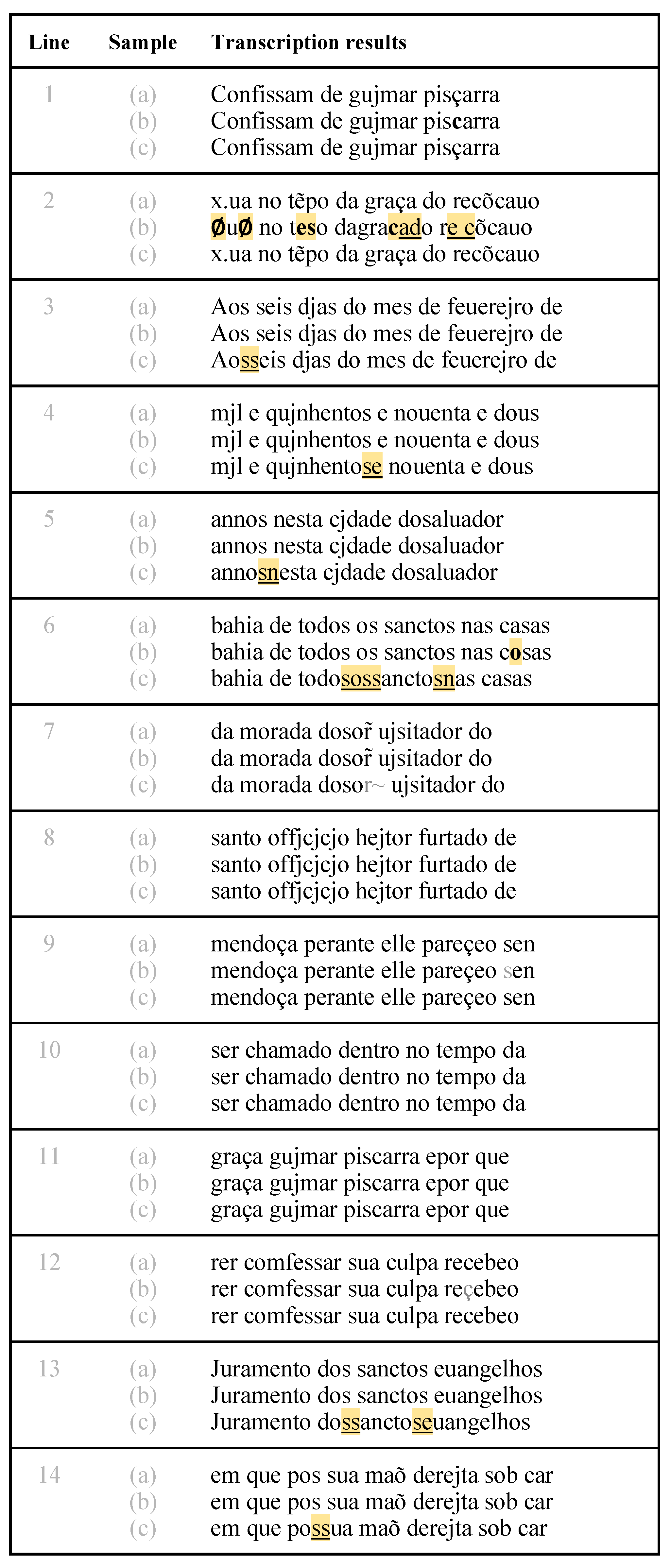

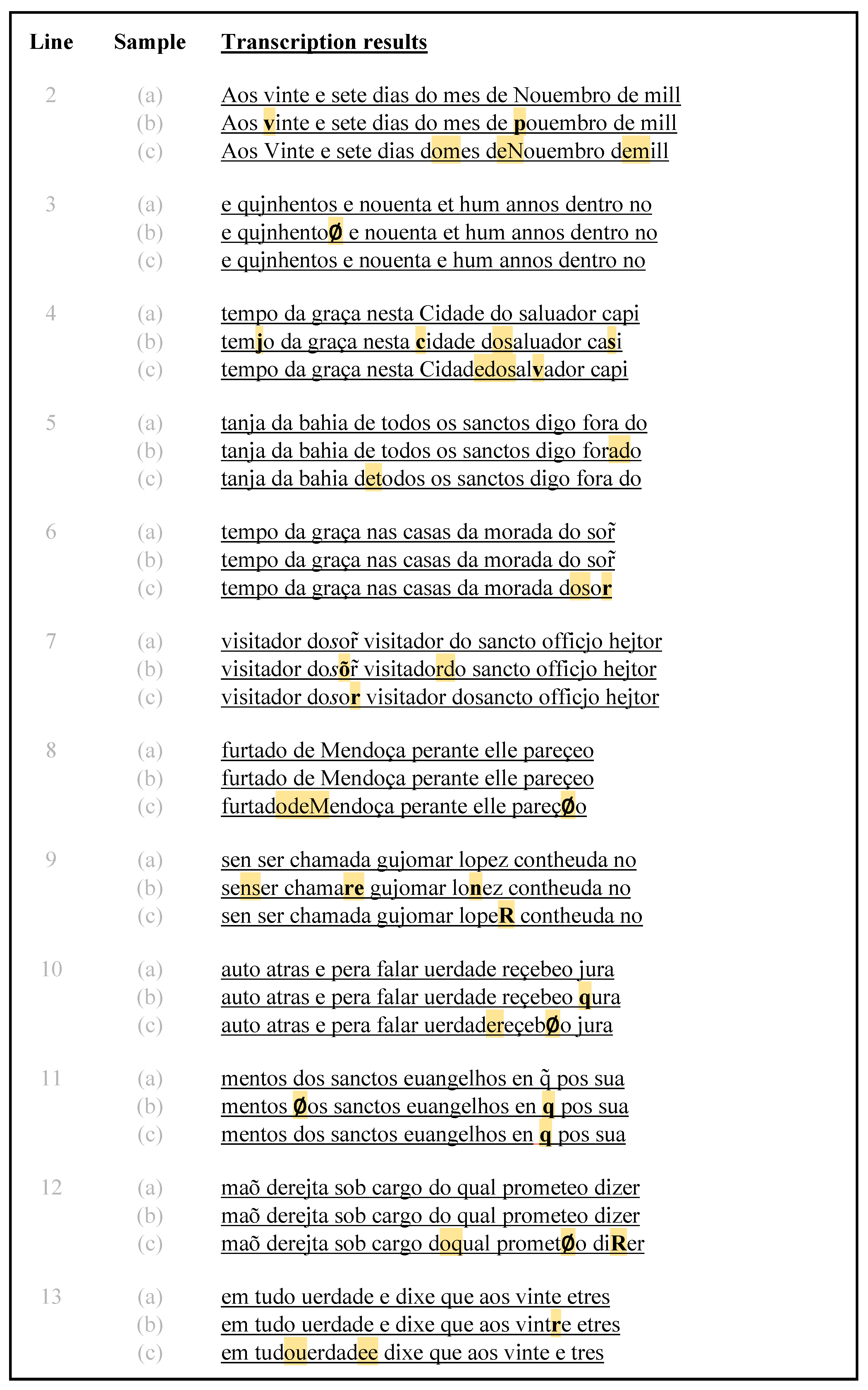

Figure 8 below shows the comparison between the human-made transcriptions and the automatic transcriptions this excerpt. The lines marked as (a) correspond to the human-made transcriptions, of ur reference, (b) to the

Transkribus ones, and (c) to the

Lapelinc Transcriptor ones. The differences are shown in

bold for changed or added characters, in

underline for different segmentation, and with a

∅ signal for missing characters. All differences are also highlighted in the automatic versions.

As shown further above in

Table 5 and

Table 6, the difference rate for the document ‘Guiomar Piçarra’ was

2.65% (97 differences/3,659 characters) in

Transkribus and

2.27% (83/3,659) in

Lapelinc Transcriptor. Considering the general difference rates for either software (

3.48% for

Transkribus, or 474/13,631, and

3.24% for

Lapelinc Transcriptor, or 442/13,631), it is notable that both achieved a very good result for this particular document. The opening protocol excerpt, remarkably, resulted in only 10 differences in

Transkribus (which would mean a 0.019% rate) and 11 differences in

Lapelinc Transcriptor (0.021%). Our hypotheses for this high accuracy will be discussed further on; before that, we show the detailed results for the other two selected manuscripts.

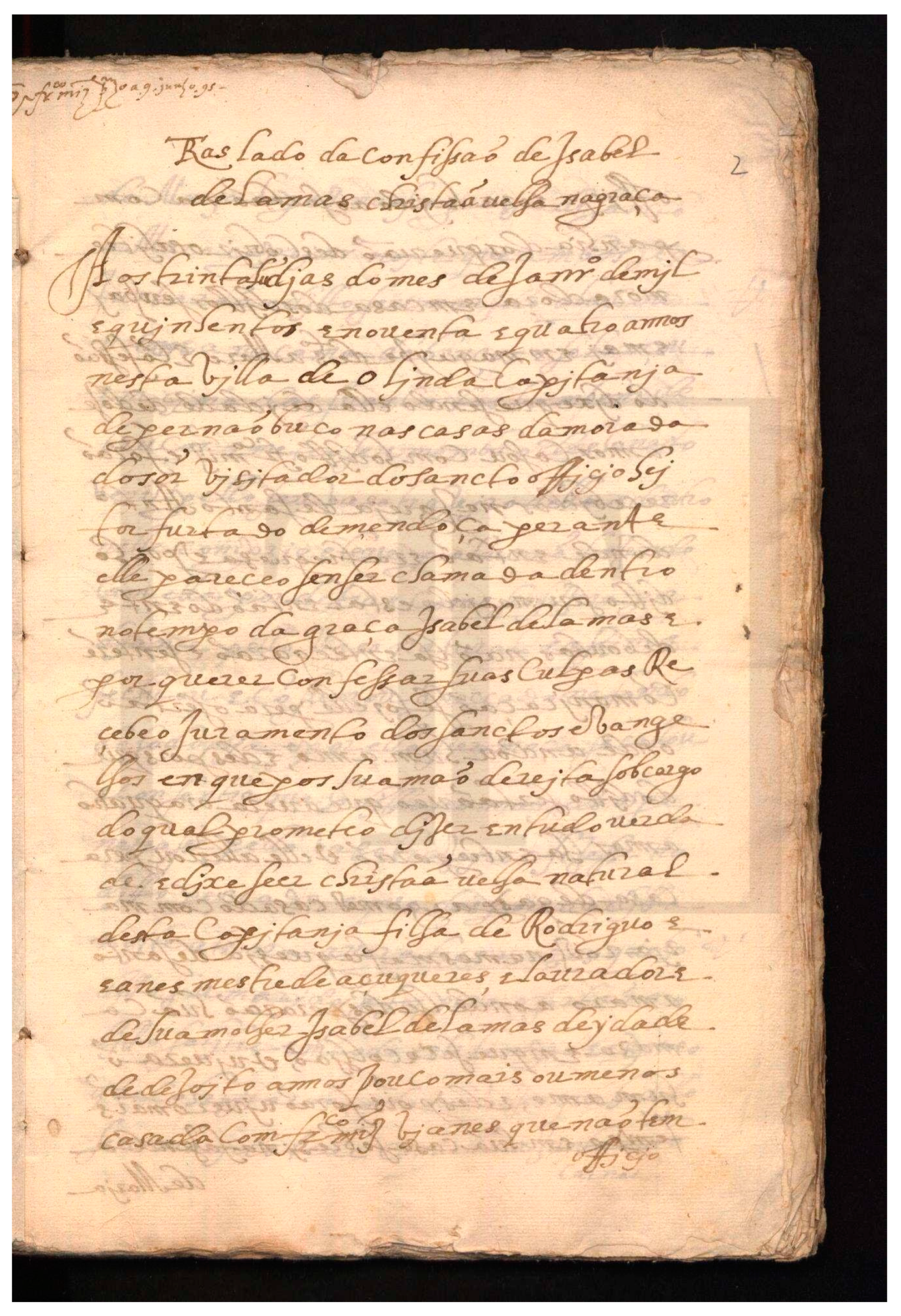

Figure 9 below shows the folio with the opening protocol for ‘Process of Isabel de Lamas’, and

Figure 10 shows the comparison between the automatic transcriptions and the human-made transcription for this excerpt.

As shown further above in

Table 5 and

Table 6, the difference rate for the ‘Process of Isabel de Lamas’ was

3.65% (162 differences/4,472 characters) in

Transkribus and

2.73% (122/4,472) in

Lapelinc Transcriptor, while the general difference rates for each software was

3.48% (474/13,631) for

Transkribus and

3.24% (442/13,631) for

Lapelinc Transcriptor. The opening protocol excerpt resulted in 19 differences in

Transkribus (which would mean a 0.036% rate) and 21 differences in

Lapelinc Transcriptor (0.040%).

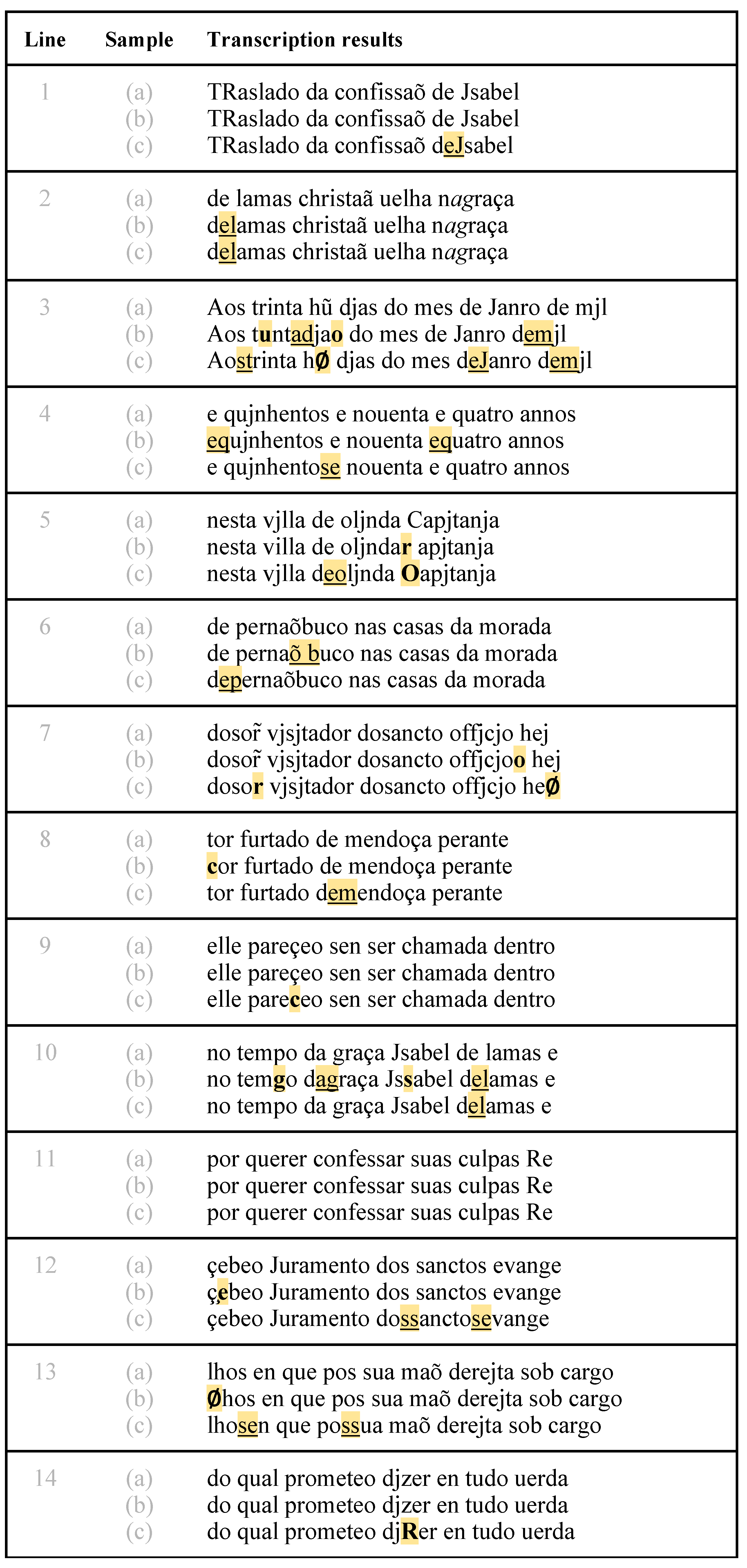

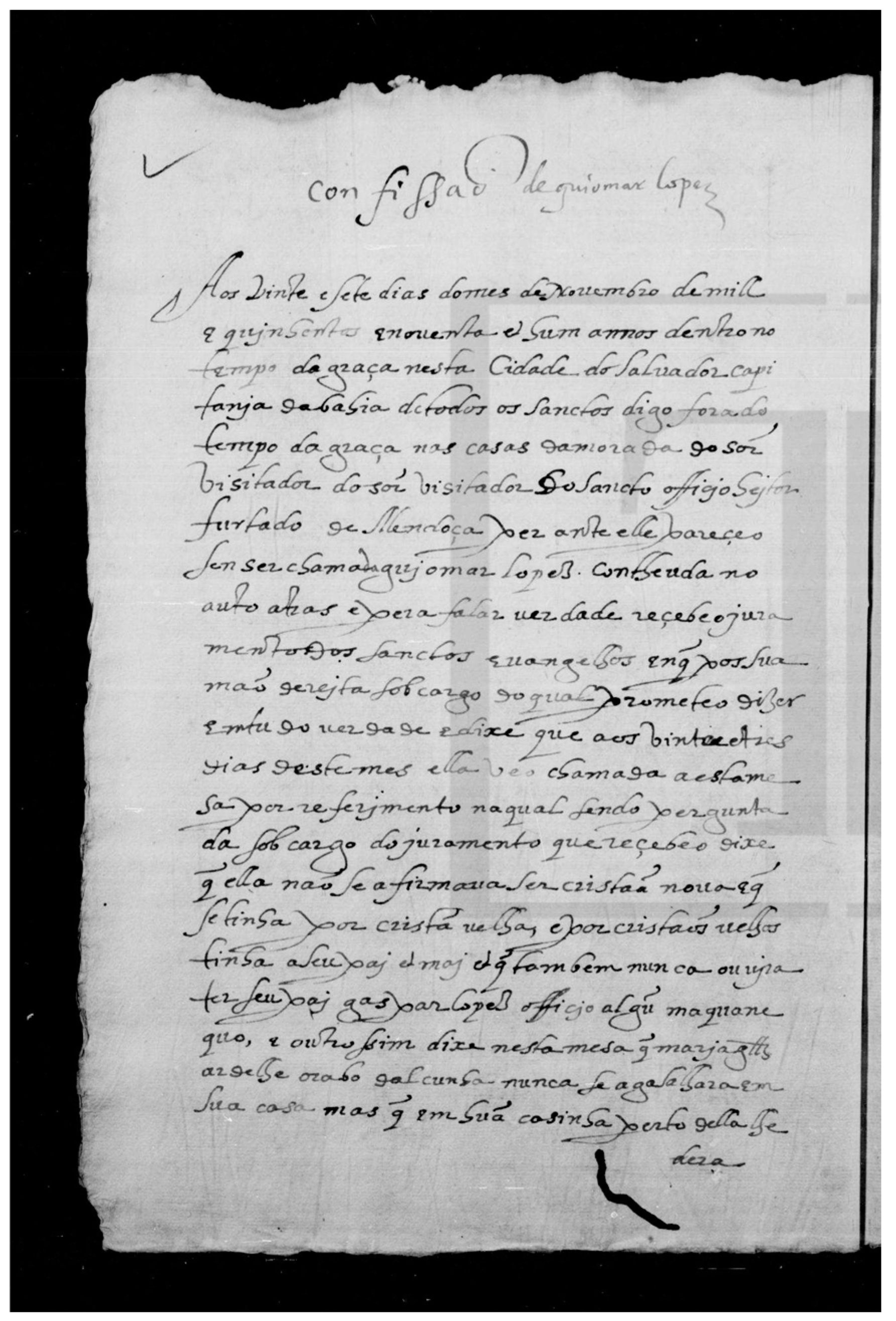

Figure 11 below shows the folio with the opening protocol for ‘Process of Guiomar Lopes’, the last of the three analyzed manuscripts, and

Figure 12 shows the comparison between the (a) human-made transcription and the (b)

Transkribus and (c)

Lapelinc Transcriptor automatic transcriptions for this excerpt.

As shown further above in

Table 5 and

Table 6, the difference rate for the document ‘Guiomar Lopes’ was

3.91% (215 differences/5,500 characters) in

Transkribus and

4.31% (237/5,500) in

Lapelinc Transcriptor, while the general difference rates for each software was

3.48% (474/13,631) for

Transkribus and

3.24% (442/13,631) for

Lapelinc Transcriptor. The opening protocol excerpt resulted in 17 differences in

Transkribus (which would mean a 0.031% rate) and 23 differences in

Lapelinc Transcriptor (0.043%). It is noticeable, therefore, that this document presented a relatively higher challenge for both automatic tools. We provide some hypotheses for this in what follows, guided by palaeographic and computational criteria.

Palaeographic Analysis Meets the Computational Results

As the comprehensive results in

Figure 8,

Figure 10 and

Figure 12 further above show, the most challenging aspect of the manuscript readings for the two tools tested in this experiment was segmentation. This, of course, is to be expected; segmentation is one of the greatest known challenges to HTR - if not the greatest challenge (cf. Sayre, 1973 to Kang et al. 2019). The so-called ‘Sayre's paradox’ is a dilemma encountered since the first designs of automated handwriting recognition systems. The paradox was first articulated in a 1973 publication by Kenneth M. Sayre, after whom it was named - cf. Sayre (1973). A standard statement of the paradox is that

a cursively written word cannot be recognized without being segmented and cannot be segmented without being recognized. If this is true for contemporary cursive writing (and, to this day, is one of the greatest challenges facing HTR technologies), it should not be surprising that segmentation in early-modern cursive manuscripts should present difficulties.

However, we should stress that, because we anticipated segmentation to be a difficulty in the automatic reading, our model transcriptions prepared to train the two applications used in this experiment were particularly careful in the approach to ‘word’ boundaries. As we mentioned in the previous subitem, diplomatic editing standards are quite conservative and their cornerstone is the preservation of word boundaries as faithfully as possible in accordance with the original. We studied Manoel Francisco's handwriting, elaborating a scriptographic chart with various allographs, in order to rigorously decide when the stroke of the final grapheme of a word was simply too close to the stroke of the initial grapheme of the next word, thus indicating segmentation, or when it was actually connected, without lifting the quill, to the stroke of the first grapheme of the contiguous word, indicating under-segmentation. In general, it was much more frequent for the initial and final graphemes to be very close, almost touching, than for them to be actually joined by the same stroke. The fact that the notary's writing style was quite chained and left a narrow graphic space between words undoubtedly posed a great challenge to HTR software. If they represent a point of extreme delicacy for human eyes, which must resort to sophisticated paleographic analyses to make the most accurate editorial decision, it was not to be expected that they would be correctly and easily interpreted by automatic recognition. From a paleographic point of view, it is important to emphasize that the notary's humanistic or italic script is quite cursive and not very calligraphic, presenting ligatures and ascenders and descenders, which represents an even greater challenge in the field of graphic segmentation.

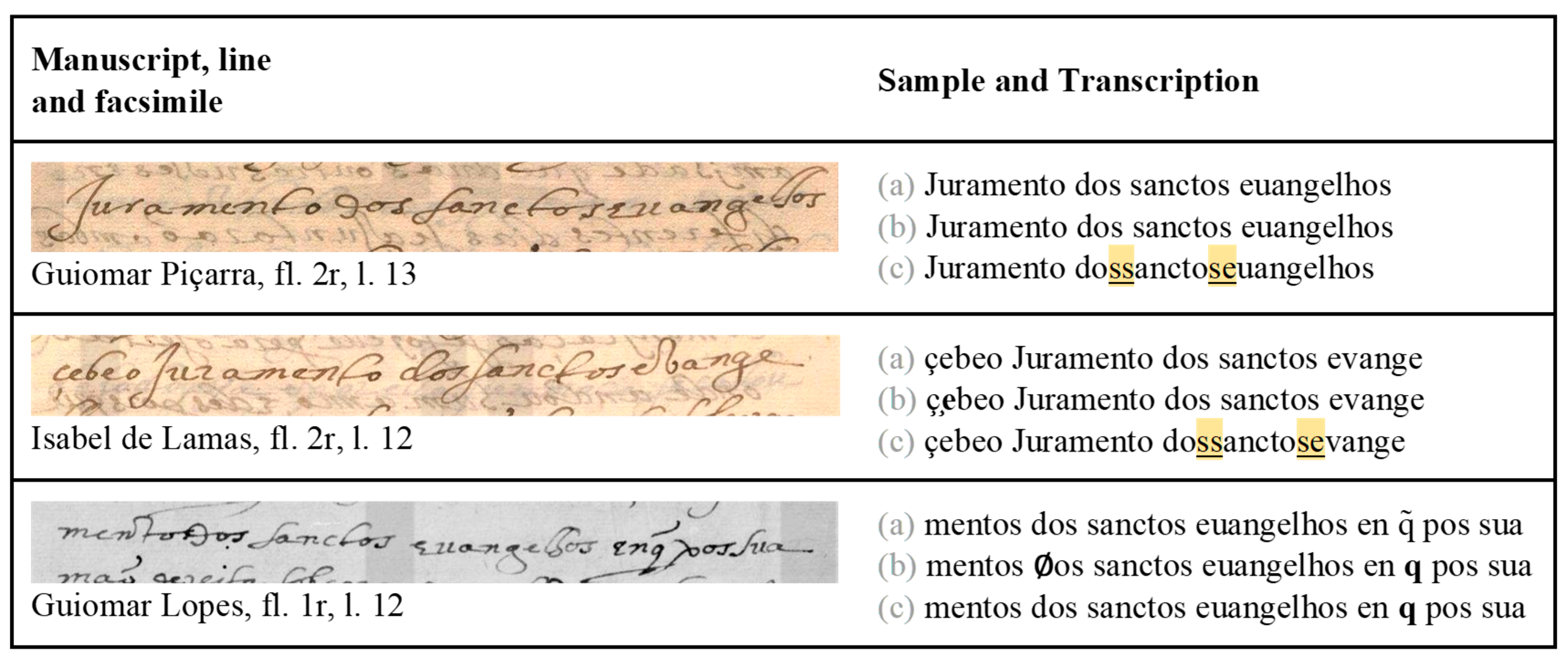

One illustrative example would be the model treatment of the phrase “

dos santos evangelhos” (‘of the holy scriptures’), which is one of the formulaic, repetitive aspects of the manuscripts both in the model and in the target corpus.

Figure 13 shows facsimile clips and the respective transcriptions for this phrase in the target corpus (in each case, with lines (a) representing the manual transcriptions, (b) the

Transkribus results and (c) the

Lapelinc Transcriptor results).

The examples show that the automatic readings were correct for the sequence ‘

dos’, ‘

sanctos’ and ‘

evangelhos’ in all samples for the ‘Process of Guiomar Lopes’, read correctly as three separate words, and wrong readings in two samples for ‘Isabel de Lamas’ and ‘Guiomar Lopes’ (in both cases, sample (c), by

Lapelinc Transcriptor), as a conjoined unit ‘

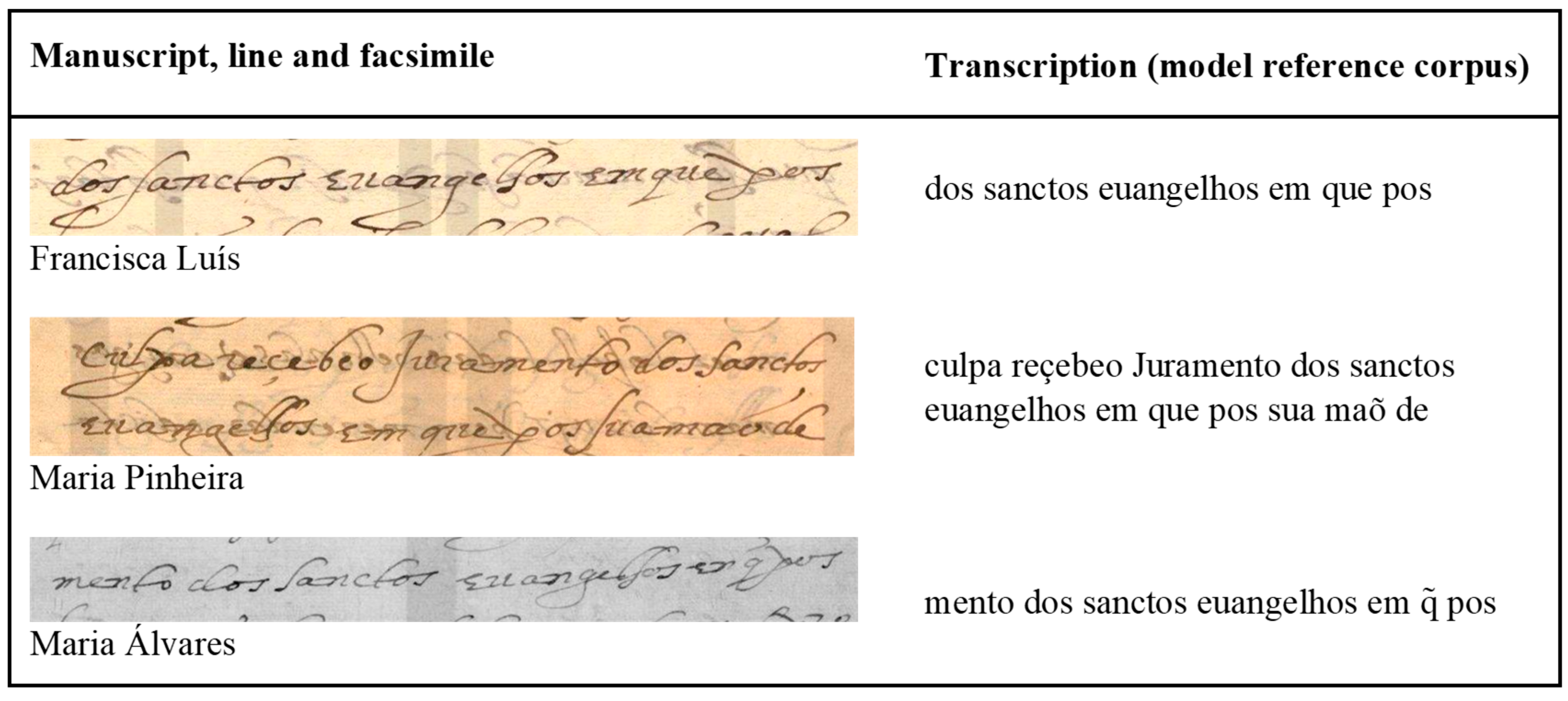

dossanctosevangelhos’, which would not meet the criterion used in our human-made transcriptions. The only segmentation option present in the model corpus, given the properties of the documents and our criteria, was for ‘

dos’, ‘

sanctos’ and ‘

evangelhos’ as three separate words, as shown in the examples in

Figure 14:

As a consequence of reading separate words as a conjoined unit is the reduction of tokens number when we compare the human-made and the automatic transcriptions. The tables below illustrate the amount of reduction in the transcription delivered by

Transkribus (

Table 7) and

Lapelinc (

Table 8).

1

Considering the mentioned typology of differences we observed in the automatic transcriptions when compared to the human-made ones — different character readings; different segmentations (be it over- or under-segmentation); missing or added characters — the most frequent challenge for HTR’s softwares was the segmentation. The tables above demonstrate a consistent pattern: both Tranksribus and Lapelinc Transcriptor tends to reduce, i.e., under-segment the humanistic cursive letter of Manoel Francisco’s hand. In other words, it tended to transcribe as joined many sequences that the human editors had read as separate.

In Transkribus, there was also over-segmenting, but with less frequency (ex. pernaõ buco). The number of ‘words’ in each technique for each text can show that objectively. Overall, the number of tokens in the Transkribus’ automatic transcriptions was around 95% of the number of words in the manual transcriptions, which signifies a reduction of 135 tokens, or 5,10%.

In Lapelinc Transcriptor, the tendency to under-segment on word level — was even greater. Overall, the number of tokens in the automatic transcriptions was around 91% of the number of tokens in the manual transcriptions. The automatic transcriptions overall had 229 less ‘words’ than the human-made transcriptions, which represents a reduction of 9%.

This tendency to reduce the original manuscript by under-segmenting it is related also with, as we are calling, manuscript density. It jumps to the eye that some of those manuscripts are ‘tighter’ than the others. We can calculate objectively this impression, measuring the number of characters of each manuscript versus the number of lines, assuming that the original folia on which the documents were drafted have the same width, or very similar widths.

The

Table 9 below shows the total number of characters and lines of each document on our target corpus. Then, we calculated the rate of characters per line, measuring its density. We decided that Isabel de Lamas should represent the ‘zero’ density, since its rate is almost equidistant from the other two documents, as we can see in the fourth column: 28 - 33 - 37. The last two columns show the difference rate for both

Transkribus and Lapelinc when we compare its automatic generated transcriptions with the human-made ones, as we already have shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6 further above.

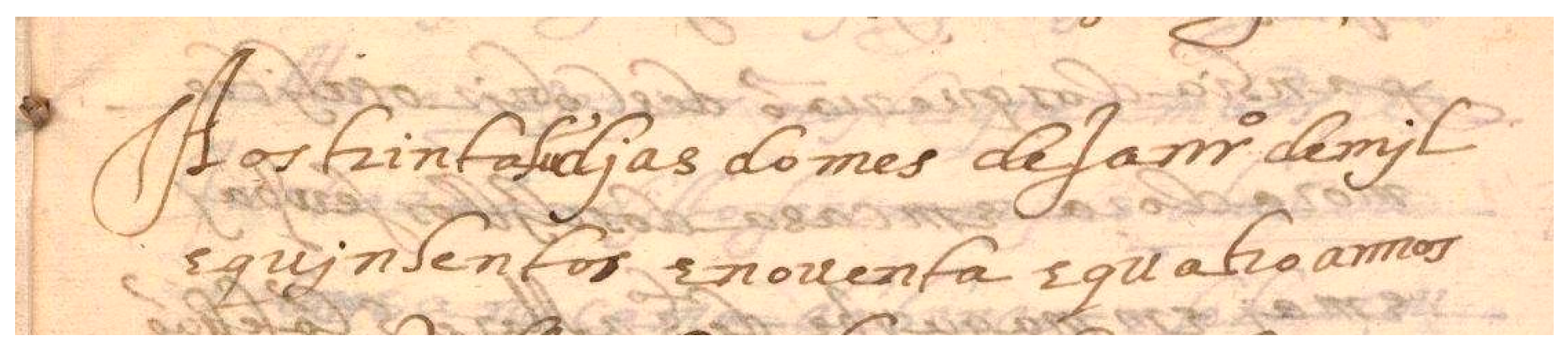

One good example of how density and handwritten recognition difficulty are intertwined is the ‘Process of Isabel de Lamas’, where the notary made a mistake on the day and had to insert the word “hũ”, as shown in

Figure 15:

The transcriptions made by Transkribus and Lapelinc Transcriptor are respectively the follow: “Aos tuntadjao do mes de Janro demjl” and “Aostrinta h djas do mes deJanro demjl”. In terms of character correctness reading, Lapelinc was perfect, but was not able to recognise the grapheme “ũ”. Transkribus, in turn, made gross errors: it didn’t recognize any characters between the words “trinta” and “djas”, and read wrong the characters “r” and the final “s” of these words. The other differences are all related to the under-segmentation.

Because of how segmentation works as a central problem for HTR, the manuscript density may be an important factor to look at when evaluating this typology of errors. Segmentation is one of the greatest challenges to HTR — if not the greatest challenge (cf. Sayre, 1973 to Kang et al. 2019). The dilemma encountered in the design of automated handwriting recognition systems is often referred to as ‘Sayre's paradox’, a standard statement of which is that

The paradox was first articulated in a 1973 publication by Kenneth M. Sayre, after whom it was named (cf. Sayre, 1973). As Gatos et al. (2006, p. 306) state:

Both of the tools used in this experiment follow a combination of the global approach with the segmentation approach. Transkribus uses the global approach combined with some other features, such as optical models – essentially, Hidden Markov Models (HMM) – and language models (cf. Kahle et. al., 2017); Lapelinc Transcriptor uses the segmentation approach to learn a pattern for each character pertaining to each hand, combined with a global approach in other aspects of the reading (cf. Costa et al. 2021).

As we understand it, the so called ‘global approach’ to segmentation is dependent on the definition of a ‘word’. That is: when designing the tools to make them recognize ‘words’, what exactly are the developers considering: a morphological unit or a graphic unit? We could not find references to this specific difference in the technical literature; this leads us to speculate that most of this literature takes the concept of ‘word’ for granted. However, while for contemporary manuscripts it could be argued that the frontiers between morphological words and graphic words tend to coincide, the same is not true for manuscripts produced in the past.

It certainly is not true for Early Modern Portuguese Manuscripts, in which the spacing between ‘words’ is the result of a complex combination between a variety of palaeographic contingencies and the linguistic segmentation. In our view, this may be one of the main factors in the challenge presented by these manuscripts to automatic recognition softwares.

4. Final Remarks

The formulation of the experiment and our interpretation of the results is closely related to our original interest in working with HTR. From a Digital Humanities perspective, the experiment involved an interdisciplinary team, which modeled our perspective on technology. In the paper, we observed the behavior of two HTR tools, Transkribus and Lapelinc Transcriptor, and found that the automatic recognition of historical manuscript text depends fundamentally on the academic work linked to Palaeography and its techniques that guide and ground the activities and parameters of historical manuscript transcription used in the construction, training and use of an HTR tool.

We consider that our experiment revealed that machine recognition of handwritten text, in the context of historical documents, is fundamentally dependent on scholarly work linked to Palaeography and its traditional rigorous techniques. This is true because training the machines to recognize the texts is not a one-step process working between the machine and the imagetic representation of the texts. It is a process with many stages, the most important of which is the interposition of a human interpretation of the text. What the machine actually learns are the patterns and consistencies of the text as interpreted by the human reading.

After the experiment we concluded that scholarly palaeographic work is the indispensable basis for automatic recognition technologies in the realm of historical manuscripts. We want to highlight that when we apply HTR technologies to historical manuscripts, we are not ‘training the machine to read the texts’. We are craftily leading the machine to emulate our own interpretation of the text, as closely as it can, given the same imagetical representation.

Serving both pragmatic and scientific interests, we hope to promote further discussions about the state-of-the-art and the challenges ahead on the road to what many already call ‘digital palaeography’ — in particular, with regard to Early Modern Portuguese manuscripts.

| 1 |

More information on the website: https://readcoop.eu/success-stories/. Some of the languages mentioned on the projects are: English, Swedish, Finnish, Dutch, German, Ottoman Turkish, Spanish and French. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

Developed by ReadCoop, an European Cooperative Society. |

| 5 |

Developed by LaPeLinC, Corpus Linguistic Laboratory of the State University of Southern Bahia, Brazil. |

| 6 |

The Portuguese Inquisition spanned for four centuries, between 1536 and 1821. Over this period and later documents were destroyed and others survived. The collection “Tribunal do Santo Ofício'' housed at Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo consists of 3004 books, 79,337 processes, 624 boxes and 329 bundles. |

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

This digital version (before the revision made for this experiment) is published at http://map.prp.usp.br/Corpus/FL, as part of the Project ‘Mulheres na América Portuguesa’ [5]. |

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

Please note that for this folio, the header (line 1 – ‘confissaõ de guiomar lopez’) was not included in the automatic transcription. |

References

- Aiello, K. D. and Simeone, M. (2019). Triangulation of History Using Textual Data. Isis, volume 110, number 3. Available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/705541 (accessed 7 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Costa, B. S., Costa, A. S., Santos J.V. and Namiuti C. (2021). LaPeLinC Transcriptor: Um software para a transcrição paleográfica de documentos históricos. Presented at V Congresso Internacional de Linguística

Histórica / V International Conference on Philology and Diachronic Linguistics - CILH; Campinas, Brazil.

- Costa, B. S., Santos, J. V. and Namiuti, C. (2022). Uma proposta metodológica para a construção de corpora através de estruturas de trabalho: o Lapelinc Framework. Revista Brasileira em Humanidades Digitais; 1(2). Available at http://abhd.org.br/ojs2/ojs-3.3.0-9/index.php/rbhd/article/view/37 (accessed 7 February 2023).

- Dimond, T. L. (1957) Devices for Reading Handwritten Characters. In: Proceedings of the Eastern Computer Conference, IRE-ACM-AIEE '57. Association for Computing Machinery, New York. Pages 232–237. DOI:

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1457720.1457765. Accessed 20 february 2023. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L. F. (1997) Glossário de Crítica Textual. Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 1997. Available at http://www2.fcsh.unl.pt/invest/glossario/glossario.htm (accessed 17 May 2024).

- Gatos, B., Ntzios, K., Pratikakis, I. et al. (2006). An efficient segmentation-free approach to assist old Greek handwritten manuscript OCR. Pattern Anal Applic 8, 305–320. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, H. A. G. (2019). Electronic Transcriptions of New Testament Manuscripts and their Accuracy, Documentation and Publication. In Hamidović, D., Clivaz, C., Savant, S. B., and Marguerat, A. Ancient

Manuscripts in Digital Culture: Visualisation, Data Mining, Communication. BRILL, 3, 2019, Digital

Biblical Studies. Available at https://hal.science/hal-02477210 (accessed 9 February 2023).

- Humbel, M. and Nyhan, J. (2019). The application of HTR to early-modern museum collections: a case study of Sir Hans Sloane's Miscellanies catalogue. Conference: DH 2019. Available at

https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10072160/ (accessed 9 February 2023).

- Kang, L., Toledo, J. I., Riba, P., Villegas, M., Fornés, A. and Rusiñol, M. (2019). Convolve, Attend and Spell:

An Attention-based Sequence-to-Sequence Model for Handwritten Word Recognition. In Brox, T., Bruhn, A. and Fritz, M. (eds.), Pattern Recognition - 40th German Conference, GCPR 2018, Proceedings. Springer

International Publishing.

- Kahle, P., Colutto, S., Hackl, G., and Mühlberger, G. (2017). Transkribus - A Service Platform for Transcription,

Recognition and Retrieval of Historical Documents. 14th IAPR International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), Kyoto, Japan, 2017, pp. 19-24, doi: 10.1109/ICDAR.2017.307. (accessed

7 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Leiva, L. A., Romero, V., Toselli, A. H., and Vidal, E. (2011). Evaluating an Interactive-Predictive Paradigm on

Handwriting Transcription: A Case Study and Lessons Learned. In Proceedings of Annual IEEE International Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), pp. 610–17.

- Magalhães, L. B. S.; Xavier L. F. W. (2021). Can Machines think? Por uma paleografia digital para textos em

Língua Portuguesa. In: Alícia Duhá Lose, Lívia Borges Souza Magalhães, Vanilda Salignac Mazzon. (Org.).

Paleografia e suas interfaces. 1ed. Salvador': Memória e Arte, p. 259-269.

- Magalhães, L. B. S. (2021). Da 1.0 até a 3.0: a jornada da Paleografia no mundo digital. LaborHistórico, v. 7, p. 279-295.

- Marcocci, G. (2010). Toward a History of the Portuguese Inquisition Trends in Modern Historiography (1974-

2009). Revue de l’histoire des religions [Online], 3. DOI: 10.4000/rhr.7622. Available at

http://journals.openedition.org/rhr/7622. [CrossRef]

- Muehlberger, G., Seaward, L., Terras, M., Ares Oliveira, S., Bosch, V., Bryan, M., et al. (2019). Transforming

scholarship in the archives through handwritten text recognition: Transkribus as a case study. Journal of Documentation [Internet]; 75(5):954-76. Available at https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JD-07-2018-0114/full/html. [CrossRef]

- Nockels, J., Gooding, P., Ames, S., Terras, M. (2022). Understanding the application of handwritten text

recognition technology in heritage contexts: a systematic review of TRANSKRIBUS in published research.

Arch Sci 22, 367–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-022-09397-0 (accessed 7 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S. A., Seguin, B. and Kaplan, F. (2018) dhSegment: A Generic Deep-Learning Approach for

Document Segmentation, 16th International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition (ICFHR), Niagara Falls, NY, 2018, pp. 7-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICFHR-2018.2018.00011. Accessed 20 february 2023. [CrossRef]

- PORTUGAL (2011). Tribunal do Santo Ofício Fond. https://digitarq.arquivos.pt/details?id=2299703.

- READ-COOP (2021). Character Error Rate (CER). TRANSKRIBUS Glossary. Available at https://readcoop.eu/glossary/character-error-rate-cer (accessed 9 February 2023).

- Vaidya, R., Trivedi, D., Satra, S. and Pimpale, P. M. (2018). Handwritten Character Recognition Using Deep-

Learning. In: Proceedings of Second International Conference on Inventive Communication and Computational

Technologies (ICICCT), Coimbatore, India, pp. 772-775. [CrossRef]

- Romero, V. , Fornés, A. , Serrano, N., Sánchez, J. A., Toselli, A. H., Frinken, V., Vidal, E. and Lladós, J. (2013).

The ESPOSALLES Database: An Ancient Marriage License Corpus for Off-line Handwriting Recognition. Pattern Recognition, Volume 46, Issue 6, Pages 1658–1669, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J. V. and Namiuti, C. (2009). Memória Conquistense: recuperação de documentos oitocentistas na

implementação de um corpus digital. Research Project. Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista.

- Sayre, K. M. (1973). Machine recognition of handwritten words: A project report. Pattern Recognition, Pergamon

Press; 5 (3): 213–228. [CrossRef]

- Terras, M. (2022). Inviting AI into the Archives: The Reception of Handwritten Recognition Technology into

Historical Manuscript Transcription. In Jaillant, L. (ed.), Archives, Access and Artificial Intelligence:

Working with Born-Digital and Digitized Archival Collections. Bielefeld: Bielefeld University Press.

- Toledo Neto S. de A. (2020). Um caminho de retorno como base: proposta de normas de transcrição para textos

manuscritos do passado. Travessias Interativas; 10(20):192–208.

https://seer.ufs.br/index.php/Travessias/article/view/13959. [CrossRef]

- Toselli, A. H., Leiva, L. A., Bordes-Cabrera, I., Hernández-Tornero, C., Bosch, V. and Vidal, E. (2018).

Transcribing a 17th-century botanical manuscript: Longitudinal evaluation of document layout detection and interactive transcription, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, Volume 33, Issue 1, April 2018, Pages

173–202. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Synthesis of the experiment.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of the experiment.

Figure 2.

Digital edition of the document ‘Denúncias contra Francisca Luís’, fl. 2r.

Figure 2.

Digital edition of the document ‘Denúncias contra Francisca Luís’, fl. 2r.

Figure 3.

A screenshot of image mapping for the modeling process at Transkribus.

Figure 3.

A screenshot of image mapping for the modeling process at Transkribus.

Figure 4.

A screenshot of image mapping and reference transcription for the modeling process at Lapelinc Tanscriptor.

Figure 4.

A screenshot of image mapping and reference transcription for the modeling process at Lapelinc Tanscriptor.

Figure 5.

Set of materials in the experiment, illustrated by the Process of Isabel de Lamas, fol. 2r.

Figure 5.

Set of materials in the experiment, illustrated by the Process of Isabel de Lamas, fol. 2r.

Figure 6.

Guiomar Piçarra, facsimile, fl 2r.

Figure 6.

Guiomar Piçarra, facsimile, fl 2r.

Figure 7.

Example of an opening protocol: human-made transcription and its translation, Guiomar Piçarra, fl. 2r, lines 1-20.

Figure 7.

Example of an opening protocol: human-made transcription and its translation, Guiomar Piçarra, fl. 2r, lines 1-20.

Figure 8.

Comparison between text clippings generated by Transkribus and Lapelinc Transcriptor software and manual transcription - Guiomar Piçarra, fl. 2r, lines 1-14.

Figure 8.

Comparison between text clippings generated by Transkribus and Lapelinc Transcriptor software and manual transcription - Guiomar Piçarra, fl. 2r, lines 1-14.

Figure 9.

Isabel de Lamas, facsimile, fl. 2r.

Figure 9.

Isabel de Lamas, facsimile, fl. 2r.

Figure 10.

Comparison between text clippings generated by Transkribus and Lapelinc Transcriptor software and manual transcription - Isabel de Lamas, fl. 2r, lines 1-14.

Figure 10.

Comparison between text clippings generated by Transkribus and Lapelinc Transcriptor software and manual transcription - Isabel de Lamas, fl. 2r, lines 1-14.

Figure 11.

Guiomar Lopes, facsimile, fl. 1r.

Figure 11.

Guiomar Lopes, facsimile, fl. 1r.

Figure 12.

Comparison between text clippings generated by

Transkribus and

Lapelinc Transcriptor software and manual transcription - Guiomar Lopes, fl. 1r, lines 2-13

18.

Figure 12.

Comparison between text clippings generated by

Transkribus and

Lapelinc Transcriptor software and manual transcription - Guiomar Lopes, fl. 1r, lines 2-13

18.

Figure 13.

Comparative results for the phrase ‘dos sanctos euangelhos’ in the target corpus.

Figure 13.

Comparative results for the phrase ‘dos sanctos euangelhos’ in the target corpus.

Figure 14.

Example for the phrase ‘dos sanctos euangelhos’ in the model corpus.

Figure 14.

Example for the phrase ‘dos sanctos euangelhos’ in the model corpus.

Figure 15.

Isabel de Lamas, facsimile, fl. 2r.

Figure 15.

Isabel de Lamas, facsimile, fl. 2r.

Table 1.

Model corpus quantitative.

Table 1.

Model corpus quantitative.

| Document Title, Year |

Pages |

Lines |

Tokens |

| Processo de Antónia de Barros, 1591 |

8 |

152 |

712 |

| Denúncias contra Francisca Luís, 1592 |

13 |

255 |

1,406 |

| Processo de Maria Pinheira, 1592 |

22 |

440 |

2,161 |

| Processo de D. Catarina Quaresma, 1593(*) |

7 |

254 |

1,428 |

| Processo de Maria Álvares, 1593(*) |

7 |

177 |

973 |

| Processo de Felícia Tourinha, 1595 |

15 |

296 |

1,753 |

| Total |

72 |

1,390 |

8,349 |

Table 2.

Target corpus quantitative.

Table 2.

Target corpus quantitative.

| Document Title, Year |

Pages |

Lines |

Tokens |

| Processo de Guiomar Lopes, 1591(*) |

3 |

150 |

1.090 |

| Processo de Guiomar Piçarra, 1592 |

6 |

130 |

688 |

| Processo de Fco. Martins e Isabel de Lamas, 1594 |

6 |

135 |

867 |

| Total |

15 |

415 |

2645 |

Table 3.

Error rate and accuracy.

Table 3.

Error rate and accuracy.

| Software |

Error rate |

Accuracy |

| Transkribus |

0.97% |

99.03% |

| Lapelinc Transcriptor |

7.69% |

92.41% |

Table 4.

Types of differences included in the rates.

Table 4.

Types of differences included in the rates.

| Difference type |

Automatic transcription |

Human-made transcription |

| Different characters |

pouembro |

nouembro |

| Different segmentation |

dagraça

pernaõ buco |

da graça

pernaõbuco |

| Missing or added characters |

hos

Jssabel |

lhos

Jsabel |

Table 5.

Automatic transcriptions of target corpus vs. Previous manual transcriptions: rates in Transkribus.

Table 5.

Automatic transcriptions of target corpus vs. Previous manual transcriptions: rates in Transkribus.

| Document |

Differences |

Characters |

Difference rate |

| Guiomar Piçarra |

97 |

3,659 |

2.65% |

| Isabel de Lamas |

162 |

4,472 |

3.65% |

| Guiomar Lopes |

215 |

5,500 |

3.91% |

| Overall |

474 |

13,631 |

3.48% |

Table 6.

Automatic transcriptions of target corpus vs. Previous manual transcriptions: rates in Lapelinc Transcriptor.

Table 6.

Automatic transcriptions of target corpus vs. Previous manual transcriptions: rates in Lapelinc Transcriptor.

| Document |

Differences |

Characters |

Difference rate |

| Guiomar Piçarra |

83 |

3,659 |

2.27% |

| Isabel de Lamas |

122 |

4,472 |

2.73% |

| Guiomar Lopes |

237 |

5,500 |

4.31% |

| Overall |

442 |

13,631 |

3.24% |

Table 7.

Number of ‘tokens’ (i.e., sequences separated by whitespace), Transkribus.

Table 7.

Number of ‘tokens’ (i.e., sequences separated by whitespace), Transkribus.

| Document |

Manual model |

Transkribus automatic transcription |

Reduction |

| Guiomar Piçarra |

688 |

652 |

5.23% |

| Isabel de Lamas |

867 |

821 |

5.30% |

| Guiomar Lopes |

1,090 |

1,037 |

4.86% |

| Overall |

2,645 |

2,510 |

5.10% |

Table 8.

Number of ‘tokens’ (i.e., sequences separated by whitespace), Lapelinc Transcriptor.

Table 8.

Number of ‘tokens’ (i.e., sequences separated by whitespace), Lapelinc Transcriptor.

| Document |

Manual model |

LaPelinC automatic transcription |

Reduction |

| Guiomar Piçarra |

688 |

628 |

8.72% |

| Isabel de Lamas |

867 |

799 |

7.84% |

| Guiomar Lopes |

1,090 |

989 |

9.26% |

| Overall |

2,645 |

2,416 |

8.65% |

Table 9.

Number of ‘tokens’ (i.e., sequences separated by whitespace).

Table 9.

Number of ‘tokens’ (i.e., sequences separated by whitespace).

| Document |

Characters |

Lines |

Characters/lines |

Density |

Transkribus difference rate |

Lapelinc Transcriptor difference rate |

| Guiomar Piçarra |

3.659 |

130 |

28 |

-5 |

2.65% |

2.27% |

| Isabel de Lamas |

4.472 |

135 |

33 |

0 |

3.62% |

2.73% |

| Guiomar Lopes |

5.500 |

150 |

37 |

4 |

3.91% |

4.31% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).