1. Introduction

Acute diarrhea (AD) is frequent [

1]. In developed countries, AD is usually a mild condition that is only rarely associated with mortality; however, even in industrialized countries AD leads to a substantial number of hospitalizations and high direct and indirect healthcare costs [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. On the other hand, AD can be a serious problem for children, particularly in the age group of 5 years and younger, and the disease burden of AD in children is even greater in developing areas and countries [

7]. Thus, AD is estimated to globally cause 1.9 million fatalities per year in children, i.e., about 18% of all deaths in children under the age of 5 years [

1]. This is largely attributable to fatalities occurring in developing countries, particularly in Africa and Southeast Asia [

7].

Except for some bacterial infections, no causal treatment exists, and current therapeutic strategies are mainly supportive. The cornerstone of treatment of AD is oral rehydration treatment (ORT), and its widespread adoption has considerably improved the prognosis of the condition [

1]. Several medications are available that reduce symptom severity and/or shorten duration of a diarrheic episode. This includes zinc, adsorptive agents such as charcoal and smectite, anti-bacterial and anti-viral drugs, the neutral endopeptidase inhibitor racecadotril, and the opioid receptor agonist loperamide [

2,

8]; use of the latter is contra-indicated in infants younger than 24 months [

9] and no longer guideline recommended [

2].

Except for some bacterial infections, no causal treatment exists, and current therapeutic strategies are mainly supportive. The cornerstone of treatment of AD is oral rehydration treatment (ORT), and its widespread adoption has considerably improved the prognosis of the condition [

1]. Several medications are available that reduce symptom severity and/or shorten duration of a diarrheic episode. This includes zinc, adsorptive agents such as charcoal and smectite, anti-bacterial and anti-viral drugs, the neutral endopeptidase inhibitor racecadotril, and the opioid receptor agonist loperamide [

2,

8]; use of the latter is contra-indicated in infants younger than 24 months [

9] and no longer guideline recommended [

2].

In addition to these medication groups, probiotics have gained attention in the treatment of AD, particularly in children, based on their excellent safety profile [

10]. The special interest group on gut microbiota and modifications of the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition recommends probiotics including Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Saccharomyces boulardii, and Limosilactobacillus reuteri for the management of acute gastroenteritis [

10,

11]. In contrast, this working group found the certainty of evidence for Bacillus clausii strains O/C, SIN, N/R and T to be very low. Against this background, we have performed a comprehensive review and meta-analysis of the available evidence on B. clausii in acute gastroenteritis in children including more recent data.

B. clausii is a spore-forming bacterium resistant to common antibiotics. It is a non-pathogenic bacterium [

12,

13], and its spores can survive harsh environmental conditions, including the acidic environment of the stomach [

13,

14], which enables it to effectively colonize the gut. B. clausii is thought to exert its beneficial effects by enhancing the gut barrier function, modulating the immune response, and competing with pathogenic bacteria for nutrients and adhesion sites [

13]. Several commercially available probiotic preparations contain B. clausii strains. Therefore, clinical evidence generated with one preparation cannot necessarily be extrapolated to others because strains have been reported to display different resistance to different antibiotics [

15].

The B. clausii strains O/C, N/R, SIN, and T exhibit varying degrees of resistance to different antibiotics: All four strains are fully resistant to erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, spiramycin, clindamycin, lincomycin, and metronidazole [

16], while each strain displays a slightly different resistance profile to some of the other tested antibiotics [

16]. Several studies have shown a low risk of subsequent transfer of antibiotic resistance from B. clausii to pathogenic microorganisms. The N/R strain of B. clausii contains a chromosomally-encoded β-lactamase gene, blaBCL-1, which confers resistance to penicillins [

17]. The gene conferring resistance to macrolides (erm) is also chromosomally located [

18], as is the gene conferring resistance to aminoglycosides (aadD2) [

19]. The chloramphenicol resistance gene, catBcl, has been acquired by B. clausii and is present as a chromosomal copy [

20]. Attempts to transfer this gene to other bacterial species, such as E. faecalis JH202, E. faecium HM107, and B. subtilis UCN19, by conjugation have been unsuccessful [

20], suggesting that the antibiotic resistance genes of B. clausii are confined to this species. Therefore, this combination of several strains is a viable option to enlarge antibiotic resistance spectrum. Accordingly, w

e will focus on a homogeneous preparation of O/C, SIN, N/R and T

strains of B. clausii that is the best characterized preparation containing B. clausii strains and has been widely used as a probiotic for several decades and is available in several countries under the brand name Enterogermina® (EG) [

12]

. A previous meta-analysis had identified 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comprising a total of 441 and 457 children in the control and EG group, respectively, and concluded that EG shortened the mean duration of diarrhea [

21]

. As our searches identified 7 additional controlled trials bringing total sample sizes to 1017 and 1040 children in the control and EG group, respectively, we aimed to provide an updated meta-analysis of the efficacy of EG using duration of diarrhea in children as the main outcome parameter.

2. Materials and Methods

Sanofi-Aventis is the marketing authorization holder of EG and maintains a comprehensive, regularly updated database on all clinical studies using EG. This includes some studies not published as full articles in scientific journals. In some cases, study reports on file with Sanofi could be used that provided more detailed information than the published articles or abstracts. Therefore, no systematic additional searches were performed. However, an initial search of the PubMed database (completed on 12.10.2024) using the key word combination of “Bacillus clausii”, “diarrhea” and “children” confirmed that the Sanofi-Aventis database did not miss any studies.

Risk of bias was classified based on the guidelines from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [

22]. Meta-analysis was performed using the validated Meta-Essentials Workbook [

23] applying a random effects model. This meta-analysis package calculates Hedge’s g as the effect size indicator (also known as Cohen’s d

s), which is similar to Cohen’s d but corrected by pooled standard deviation (SD). Our analyses are in line with current recommendations for meta-analyses for probiotics [

24].

3. Results

We have identified 14 controlled clinical trials that are summarized in

Table 1; this includes 11 RCTs and three controlled but non-randomized studies. While most were reported in scientific journals, one was published as abstract only [

25] but a study report was available to the authors, one was a MSc thesis [

26], and one was available as study report [

27]. Key features and findings will be summarized hereunder in chronological order of publication, first for the RCTs and then for the non-randomized controlled studies.

The technical quality of the retrieved clinical trials was heterogeneous (

Table 1). Five studies [

25,

28,

29,

30,

31] were rated as adequate for both generation of the allocation sequence and allocation concealment for the children and parents. The three non-randomized trials did not include allocation concealment [

26,

32,

33], and the method used for allocation sequence and allocation concealment was unclear the remaining five studies [

27,

34,

35,

36,

37]. In only two studies care providers, participants, and outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation [

29,

31]. The analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis in three studies [

27,

28,

32]. The other studies did not report on this. Loss to follow-up was adequately described in four studies [

27,

28,

29,

32]and was unclear in the remaining studies. In the overall assessment of bias, four studies [

28,

29,

30,

31] were rated as ‘good’ (low risk for bias), five studies [

25,

27,

36,

37,

38] were susceptible to some bias rated as ‘fair’; two additional studies were rated as ‘poor’ based on the information in the published articles [

34,

35] but the authors of the previous meta-analysis reported to have communicated with the investigators and based on the information provided to them upgraded their status to ‘fair’ [

21]. The three non-randomized studies also had no allocation concealment and were rated as ‘poor’ (high risk for bias) [

26,

32,

33].

3.1. Description of Randomized Controlled Trials

The first single-blind RCT assigned 571 out-patients aged 3-36 months visiting a family pediatrician for acute diarrhea in Italy to one of six treatments [

28]. While all children received ORT, some groups additionally received various probiotics for 7 days including one group receiving EG (10

9 colony forming units (CFU) given b.i.d.). Co-primary endpoints were median duration of AD and number and consistency of daily stool outputs from the first day of probiotic administration. Median duration of AD was 119 hours (IQR 95.2; 127.0) in the control and 118.0 (95.2; 128.7) hours in the EG group, respectively. The median number of stools declined from 5 (4; 6) on day 1 over 7 days to e.g., 4 (3; 5) on day 4 in the control group and from 6 (4; 6) to 4 (3; 5) in the EG group. Among secondary endpoints, stool consistency was not affected, 4.2% and 4.0% in the control and EG groups, respectively, were secondarily admitted to the hospital, 34.8% and 29.0% developed a fever, and 37.0% and 32.0% were vomiting in the treatment period. No adverse events (AEs) were reported in any group.

An open label study from India randomized 255 out-patients aged 6 months to 5 years to receive ORT + zinc or additionally EG (2x10

9 CFU b.i.d.) for 5 days [

27]. The primary outcome parameter was duration of diarrhea (56.1 vs. 48.6 h in the control and the EG group, respectively). Secondary endpoints included mean number of stools per day (8.6 vs. 7.4), consistency of stools, and vomiting episodes as observed on each day of treatment, and secondary admission to the hospital. AEs occurred in 41 and 46 children, respectively.

A group from the Philippines randomized 70 children (both in- and out-patients) to received ORT or additionally EG 1-2x10

9 CFU b.i.d.) for a 3-day treatment [

25]. The duration of diarrhea (primary endpoint) was shorter in the B. clausii than in control group (69.8 vs. 83.8 h). The mean duration of hospital stay was also shorter favoring EG group (59.0 h vs. 76.8 h). The number of stools per day was lower from day 2 of treatment onward, e.g. 0.46 ± 0.52 vs. 1 ± 0.56.

An Indian proof-of-concept study assigned 131 in-patients to receive ORT + zinc or additionally EG (2x10

9 CFU b.i.d.) for 5 days [

35]. Outcome parameters included duration of diarrhea (47.05 vs. 22.64 h), stool frequency (from 3.56 per day at baseline to 1.70 at study end in the control and from 6.30 to 1.15 in the EG group), time to discharge (5 vs. 3 days) in the control and EG group, respectively. While dehydration was observed in 26% of children in the control group, it occurred in 5% I the EG group. The report did not include tolerability information. The same group conducted a follow-up study in which 160 children were randomized to either ORT + zinc or additionally EG treatment (2x10

9 CFU b.i.d.) for 5 days [

34]. Endpoints included duration of diarrhea (34.16 vs. 22.26 h), change of stool frequency (3.56 to 1.70 vs. 6.30 to 1.15), respectively.

Another Indian group randomized 120 hospitalized children to three groups including ORT + zinc or additionally EG treatment (2x10

9 CFU b.i.d.) [

38]. The co-primary outcome measures were duration of diarrhea after admission (57.65 vs. 53.33 h) and mean number (e.g., on day 4 1.28 vs. 0.35) and median consistency of stools per day (e.g. on day 3 semiliquid vs. loose). Secondary parameters were duration of vomiting, duration of fever (23.30 vs. 12.15 h) and duration of hospital stay (80.85 vs. 78.15 h).

A third group from India randomized 105 hospitalized children to standard treatment, additional EG, or additional different probiotics [

30]. The median duration of diarrhea was 108 and 96 h and of hospital stay 3.34 vs. 3.06 days in the control and EG group, respectively. The daily number of stools was lower on days 3 and 4 in the EG than in the control group.

Investigators from Bangladesh reported on two studies. The first RCT randomized 310 hospitalized infants and children to receive standard care or additionally EG [

37]. Duration of diarrhea was 3.3 vs. 3.2 days and of hospital stay 3.8 vs. 3.8 days in the control and EG group, respectively. The frequency of diarrhea was similar in both groups during the 5 days after the start of treatment. Stool consistency was graded better with EG than with control treatment on days 3 and 4. No information on tolerability was provided. The second RCT assigned 300 infants and children to receive standard treatment, the same plus EG, or a multi bacteria product [

36]. Duration of diarrhea was 3.26 vs. 3.22 days and of hospital stay 3.84 vs. 3.22 days in the control and EG group, respectively. The frequency of diarrhea was smaller on each of the 5 days in the EG group, but median stool consistency was similar on each day.

A study from Kenya randomized 90 hospitalized children to receive standard treatment or additionally EG [

29]. In contrast to the above trials, this was double-blind, but only the per-protocol population was analyzed, i.e., excluding 5 and 7 children, respectively in the control and EG group who were lost to follow-up or non-compliance, leaving 46 and 44 participants for analysis. The duration of diarrhea, the primary outcome parameter of the study, was 86.7 vs. 77.6 hours in the control and EG group. A similar shortening was found in a sub-analysis of those infants being younger than 12 months, whereas a similar duration was found in those 12 months or older. The frequency of diarrhea was smaller in the EG group on each of the 7 days of follow-up. The duration of the hospital stay was longer in the control than the EG group (4.50 vs. 4.14 days).

One of the above groups from India reported on the largest RCT, which was a placebo-controlled, multi-center trial under Good Clinical Practice conditions (including standard treatment in both group) and included a total of 457 in-patients [

31]. The primary endpoint was duration of AD in the intention-to-treat population and was 42.1 and 42.8 h in the control and EG group. The incidence of recovery as well as number of stools on each of the 5 treatment days was similar across groups. Dehydration abated slower with control than with EG (e.g., day 4 29% vs. 26% and day 5 25% vs. 14%). The incidence of treatment-emerging AEs was similar in the control and EG groups (9.7% vs. 12.3%) and mostly consisted of vomiting, pyrexia and nasopharyngitis. No deaths or serious AEs occurred in either group, but three and two patients in the control and EG group did not complete the study due to AEs.

3.2. Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials by Outcome Parameter Including Meta-Analysis

The data from some studies were technically unsuitable for inclusion in the meta-analysis, for instance because SD was not reported. In line with the previous meta-analysis of early studies with EG [

21]

, we converted IQR to SD using the equation: SD = IQR/1.35 if reported data included IQR. For some parameters, such as stool frequency, time courses were reported; as AD typically is a self-limiting condition abating in 7-10 days, we analyzed data on day 4 for the parameters where a time course was reported; this choice was made based on large previous studies with other probiotics indicating it to be discriminating treatment vs. control [

39]

. Where intention-to-treat, per-protocol and/or safety population data were reported, we have used the intention-to-treat data for the analysis.

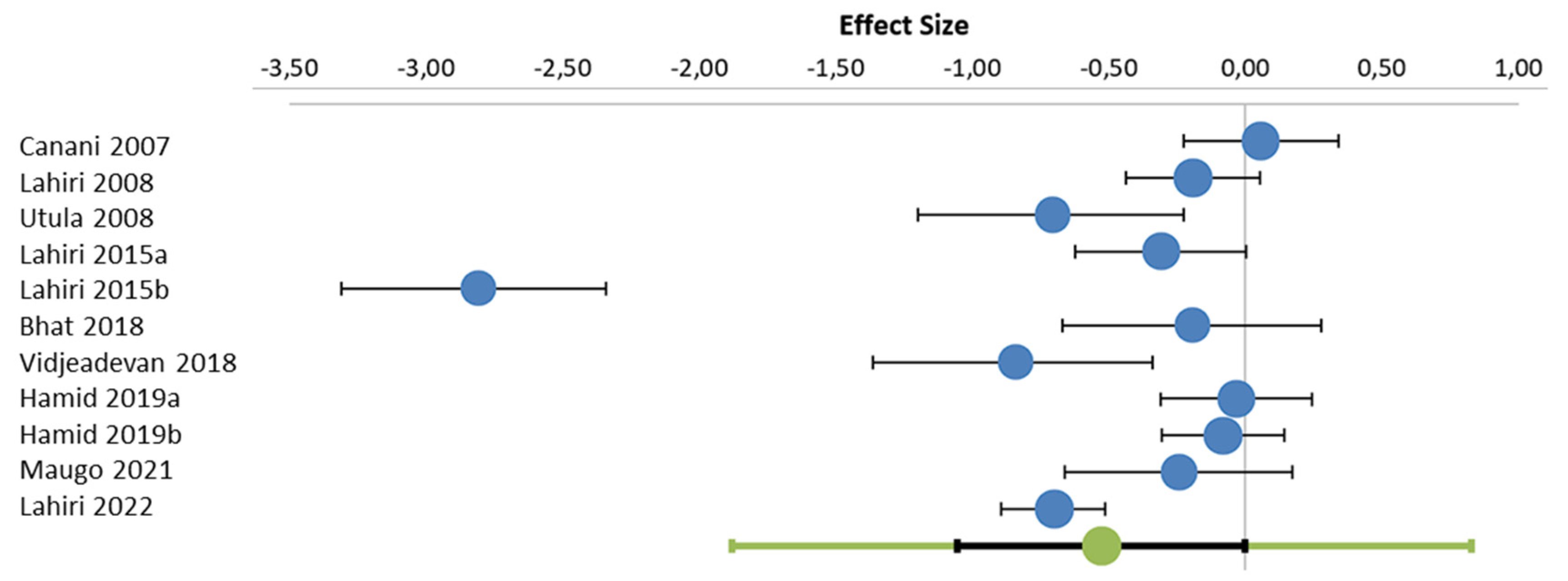

All 11 RCTs report on duration of diarrhea, most often as the primary endpoint. They differed considerably in duration of diarrhea (ranging from 34.2 to 117.5 h) and within-study variability (SD ranging from 8.6 to 40.2 h) in the control group. Addition of EG on top of standard treatment shortened the duration of diarrhea (

Figure 1). The yielded a Hedge’s g of -0.60 standard deviations (95% confidence interval -1.05; 0.00; two-tailed p-value 0.026).

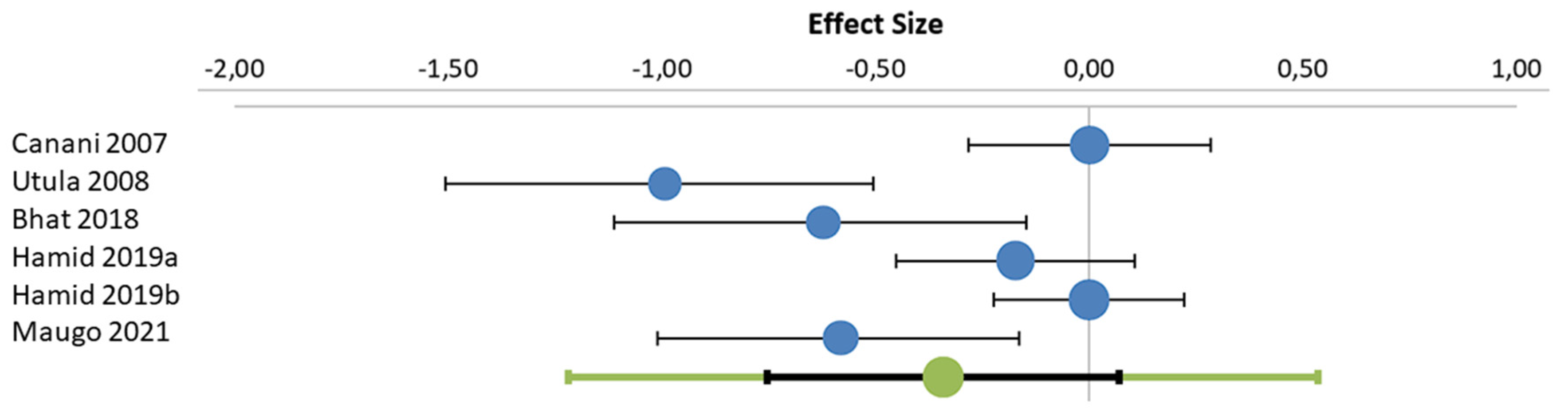

Data on number of stools was reported in 10 RCTs of which seven could be included in a meta-analysis [

25,

26,

28,

29,

36,

37,

38]. The addition of EG on top of standard treatment reduced the number of stools on day 4 (

Figure 2). The yielded a Hedge’s g of -0.34 standard deviations (95% confidence interval -0.75; 0.07; two-tailed p-value 0.033). The three studies that could not be included in the meta-analysis confirmed this tendency: One trial reported on total number of stools until recovery, which was 8.6 ± 6.5 in the control and 7.4 ± 6.5 in the EG group (within study p-value >0.05) [

27]. Another trial found that frequency of stools declined from 3.56 at baseline to 1.70 at study end in the control and from 6.30 to 1.15 in the EG group (within study p-value <0.05) [

35]. A third study reported that the frequency of stools within 24 and 60 hours was reduced in the EG as compared to the control group (within study p<0.01) but did not disclose quantitative data [

34]. A fourth study also found a lower number of stools on days 3 and 4 as compared to the control group but did not provide error bars [

30]. While these four studies could not be included in the meta-analysis for technical reasons, they strengthen the robustness of the conclusion that EG reduces number of stools.

Data on stool consistency on a day-by-day basis were reported from five studies but these were not suitable for meta-analysis on technical grounds. One study reported median stool consistency as assessed on a 4-grade scale to be grade 2 in both groups [

28]. Another trial applied a 3-grade scale and observed a numeric shift in the EG group for a favorable outcome that did not reach within study statistical significance [

27]. The third study also applied a 4-grade scale with a median grade 1 in both groups day 3 (within study p-value 0.625); on day 3 it was grade 3 in the control and grade 2 in the EG group (within study p-value 0.023) [

38]. One group also a applied a 4-grade scale and reported a median value of 1 in both groups on day 4 (within study p-value 0.032) in one study [

37] but no difference in the other [

36]. While there was a trend for improved consistency that reached a low p-value in two of the four studies, effect sizes appear to be limited.

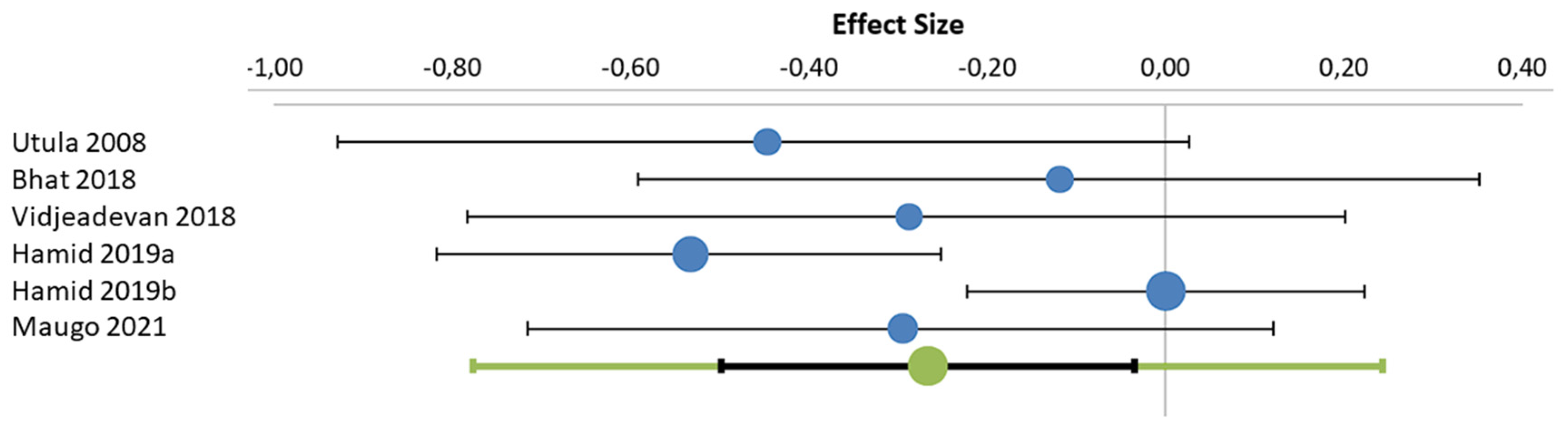

The duration of hospital stay was reported in seven studies of which six with a total of 806 subjects could be used for the meta-analysis [

25,

29,

30,

36,

37,

38]. The addition of EG on top of standard treatment shortened the duration of the hospital stay with a Hedge’s g of -0.27 standard deviations (95% confidence interval -0.50; -0.04; two-tailed p-value 0.003;

Figure 3). One other study reported a clinically relevant shortening (4.30 vs. 2.78 days, reported intra-study p-value <0.01) but could not be included in the meta-analysis because it did not provide variability information [

34]; however, it further strengthens the conclusion that EG shortens the duration of the hospital stay. The conclusion is in line with the earlier meta-analysis based on three studies [

21]

, confirming the overall robustness of the finding.

Three studies reported on the effect of EG on vomiting. The median duration of vomiting was 2 days (IQR 1; 2) in the control vs. 1.5 (1; 2) in the EG group in one study [

28]. A second study analyzed the number of vomiting episodes on each of the 5 days after initiation and treatment [

27]. This declined from 0.4 episodes prior to the start of treatment to 0.1 on day 5 in both groups. While this reached a p-value <0.05 on day 4 in the control group, this was achieved on day 2 in the EG group, i.e., reaching a reduction faster. A third study claimed a lack of difference between the two groups but did not disclose quantitative data [

38]. Due to the heterogeneity in reporting, a formal meta-analysis was not possible for vomiting, but three of the four studies reported EG to be superior to standard treatment.

The presence of fever was reported as a secondary parameter in two RCTs. One reported that it occurred in 34.8% of children in the control group vs. 29.7 in the EG group (p = 0.61); in those developing fever it lasted for a median duration of 2 days in both groups [

28]. Another trial claimed that EG reduced the duration of fever as compared to control but did not provide quantitative data or statistical analysis [

38]. While these data are too limited for a robust conclusion, they point to a favorable effect of EG.

Dehydration abated faster with EG than control treatment in both studies reporting on this parameter [

31,

35]. In a study on outpatients, secondary admission to a hospital occurred with similar frequency in both groups [

28].

3.3. Description of Non-Randomized Controlled Trials

A study from Pakistan assigned 160 hospitalized children with acute watery diarrhea of more than 3 times daily for 1-7 days aged 6-60 months of age to one of four treatments: ORT alone, ORT plus EG (2x10

9 CFU q.d.), and ORT plus one of two multicomponent probiotics for 7 days [

26]. The duration of diarrhea was shorter with EG than ORT alone (84 vs. 114 h). The number of daily stool outputs declined over time in all groups but was greater in the EG than the ORT group, e.g., 2-3 vs. 5-6 on day 7.

A single-center case series from Ukraine focused on children with confirmed rotavirus infection who underwent treatment with EG (n = 20) or other probiotics (not specified; n = 18) [

33]. Mean treatment time was 4.5 ± 1.2 days in the EG and 6.5 ± 0.9 days. Clinical recovery defined by normalization of the stool and the general condition) occurred within 5 days in 75% of the EG group vs. 12% in children receiving other probiotics. On day 9, the recovery was 98% vs. 50%. No AEs were observed.

Finally, another Ukrainian group assigned 65 infants and children with rotavirus-induced AD to receive standard treatment or additional EG [

32]. The main interest of this exploratory study was assessment of immunological parameters such as immunoglobulin A, G, or M levels, which were improved by treatment with EG, including increased immunoglobulin A levels. Outcomes related to diarrhea were reported only as group differences with p-values. This included a shorter duration of diarrhea (by 1.13 days), of vomiting (by 0.6 days), of abdominal swelling and pain (by 0.72 days), and of raised body temperature (by 0.52 days; all p < 0.05); an absence of general weakness occurred 1.17 days earlier in the EG group.

3.4. Tolerability

Three RCTs [

27,

28,

31] and one non-randomized study [

33] included information on the occurrence of AEs in the treatment groups. One RCT with a total of 192 children reported absence of AEs across the control and EG group [

28]. Another RCT reported 41 (31.1%) and 46 (34.9%) in 132 patients each in the control and the EG group, respectively [

27]. Most AEs were of gastrointestinal origin and documented as unrelated to study medication. No serious AE was observed. A third RCT also found the incidence of AEs to be similar in both groups with 28 (12.3%) in the control and 22 (9.7%) in the EG group [

31]. The most frequently reported AEs in both groups were vomiting, pyrexia, and nasopharyngitis. While most AEs were of mild severity, moderate vomiting and pyrexia as well as severe dehydration were observed in 1-2 cases each. No deaths or serious AEs were reported. Three and two AEs in the control and EG group, respectively, led to study discontinuation. None of them was rated as related to study medication by the investigator. Finally, the observational study comparing EG to other (unspecified) probiotics reported absence of AEs in both groups [

33]. While the absence of AEs reporting in several studies is unfortunate, the available data point to a low risk of AEs at a similar level as observed with control treatment with no reports of AEs judged as treatment related by the investigators.

4. Discussion

A previous review and meta-analysis of RCTs on the use of EG in the treatment of AD covered six trials [

21]. Meanwhile, the number of RCTs in this field has almost doubled allowing us to analyze findings from 11 RCTs, including all from the previous meta-analysis. This brings the total sample sizes in the control and EG groups to 1017 and 1040 children, respectively, i.e., more than doubles the sample size on which the previous meta-analysis was built. It was our primary intention to focus on duration of diarrhea, which was the primary endpoint in most studies (some did not define a primary endpoint). Based on the availability of multiple studies, we additionally performed a meta-analysis for number of stools (10 studies) and duration of hospital stay (7 studies).

The RCTs included in our analysis represent different geographic regions including Africa (Kenya; one trial), Southeast Asia (Bangladesh, India, Philippines; nine trials), and Europe (Italy; one trial). One non-randomized controlled trial was from Pakistan and two were from Ukraine. This is of clinical relevance because most are based on trials performed in Africa and Southeast Asia, i.e., areas where AD remains a major cause of death [

1,

7] and which contribute in a major way to the estimated 1.9 million of fatalities among children with AD. The wide geographic distribution of studies across seven countries on three continents with their differences in nutrition status, access to clean drinking water and healthcare systems impacted baseline values between studies (e.g., duration of diarrhea ranging from 34.2 to 117.5 h) as did the inclusion of studies on outpatients and hospitalized patients.

The meta-analysis for duration of diarrhea, the primary endpoint of most studies and the primary focus of our analyses, based on 11 RCTs found a statistically significant shortening by 0.53 SD, and one additional trial that could not be included in the meta-analysis for formal reasons reported a shortening by 27.1 hours (within study p-value < 0.0001). The daily number of stools was typically reported as time courses. The meta-analysis based on six RCTs also detected a statistically significant reduction as assessed on day 4 of treatment by 0.34 SD. Four additional RCTs could not be included in the meta-analysis but each reported a reduction reaching within study p-values < 0.05. Time courses of development of stool consistency also show a trend for improvement in favor of EG.

The duration of hospital stay has no direct medical relevance but is important for two reasons. Firstly, it reflects time to recovery. Secondly, particularly in low-income countries, it is highly relevant for the parents who most often have to pay for hospital stay without reimbursement. The meta-analysis based on six trials showed a statistically significant shortening by 0.27 SD. A seventh study reported a shortening from 4.30 to 2.78 days (within study p-value < 0.01), thereby demonstrating a highly robust effect of EG on this parameter. Among four trials reporting on vomiting, three had data in favor of EG.

The RCTs reporting on the above parameters in a format technically not suitable for inclusion in the meta-analyses generally confirmed the meta-analysis findings, very often with intra-study statistical significance. Moreover, the three controlled but non-randomized studies confirmed the observed beneficial effects of EG for various parameters and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.