1. Introduction

Language plays a crucial role in human communication and has contributed significantly to the development of human civilization. It serves as a means for people to interact socially and emotionally, as well as to express various emotions such as kindness, love, rage, and suffering in public [

1]. There are over 2000 distnict languages and 200 dialects in Africa belonging to four major linguistic super-families (Niger-Congo, Afro-Asiatic, Nilo-Saharan and Khoisan)[1] [1]

https://bit.ly/lingustic. Ethiopia is a multilingual African country and a home to over 86 languages that can be grouped into Semitic, Cushitic, Omotic, and Nilo-Saharan [

2,

3], which share a genetic affinity despite being divided into widely disparate subgroups of the same family.

The internet has had a significant impact on language since its inception, with the rise of instant communication through email, social networking such as Twitter, Linked in users increasing [

4], blogs, and the World Wide Web as a whole [

5,

6]. This has led to a dramatic increase in the number of digital and paper documents in various languages, requiring automatic processing for language identification. Two broad categories of languages exist in the language identification challenge: (i) different languages with similar scripts and (ii) the same language with different scripts. The automatic analysis and recognition of scripts is known as script recognition [

7,

8,

9]. For example, in Ethiopia, languages such as Amharic, Tigrigna, Awigna, and Geez use the Ethiopic alphabet, while Afaan Oromo, Somali, and Afar use the Roman alphabet. The second challenge involves looking into languages written in different scripts at different times, such as Afaan Oromo. This paper focuses on the identification of low-resource languages written in a similar script, such as Amharic, Tigrigna, Awigna, and Geez.

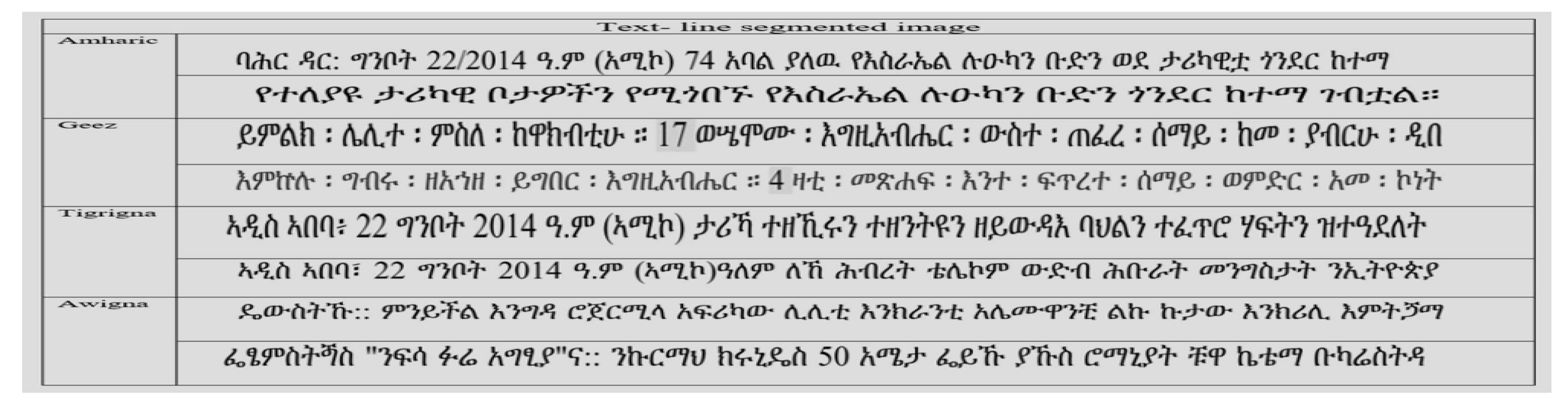

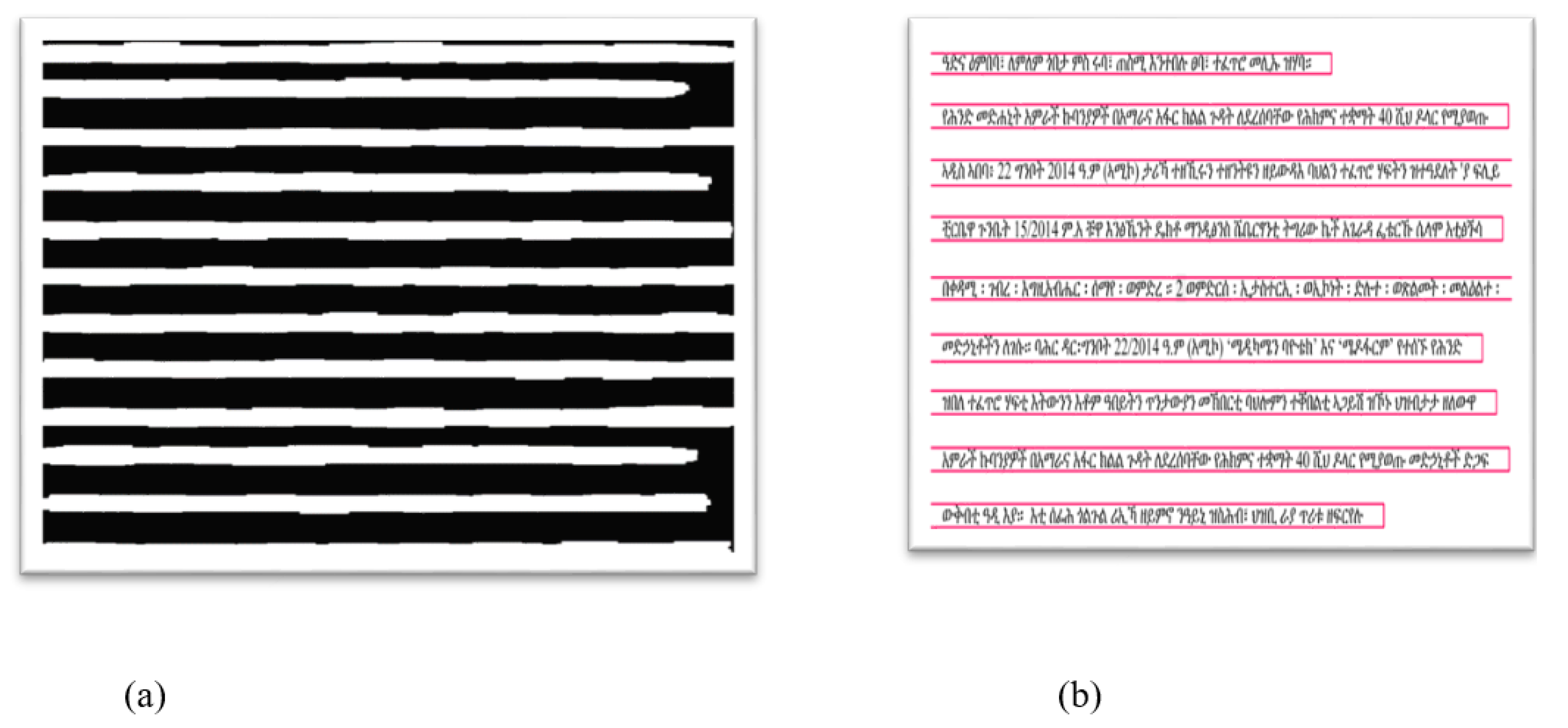

Figure 1.

Sample Multilingual Document Image

Figure 1.

Sample Multilingual Document Image

Language identification (LID) plays a crucial role in natural language processing (NLP) problems, as it involves determining the language of a document or a part of it [

2,

10,

11]. This step is necessary for many NLP applications, such as machine translation, sentiment analysis, document summarization, document image classification, and retrieval. For instance, Google’s free translation service[2] [2]

https://translate.google.com attempts to detect the language of the text before translating it into another language [

12]. However, when dealing with Ethiopian languages with similar scripts but different languages, they are often translated as Amharic by default instead of considering each individual case.

OCR systems are commonly used for tasks like character segmentation and recognition [

13,

14,

15]. However, integrating Language Identification (LID) beforehand is crucial to employ language-specific OCR models, improving accuracy and enhancing data accessibility across diverse applications [

12]. It is essential for document image analysis tasks, such as document image classification, document image retrieval, OCR, and search engines. Search engines crawl web pages and need to identify the language for each web page to determine whether they should appear in search results. Similarly, search engines must determine the language of the user’s search query. When employing text processing techniques for information retrieval, it is assumed that the language of the text is known, and many techniques assume that all documents are written in the same language.

Language identification on document images is challenging, as highlighted in [

16], and also for handwritten recognition, as highlighted in [

17]. Nonetheless, LID is essential in machine translation and document image analysis tasks [

18]. Identifying a language in a document image can be considered a pre-OCR, document image retrieval, and classification task. In pre-OCR cases, language identification serves as the foundation for correct transcription of a document into an editable document in a multilingual setting. Therefore, the addition of language identification to OCR would simplify OCR’s role in converting hardcopy documents to editable text, allowing for the preservation of more historical documents written in multiple languages. LID in document images is necessary not only for OCR but also for text translation, sentiment analysis, document and information retrieval.

deep learning-based methods have been shown to perform better than traditional methods and have produced promising results in various applications [

19,

20]. In this paper, we apply deep learning-based methods to tackle the problem of language identification from document images written in Ethiopic script. We explore different state-of-the-art deep learning methods and select suitable techniques to develop multilingual language identification in the context of Ethiopian languages. Specifically, we implement a custom-CNN and pre-trained strategies for feature extraction and model tuning, given their wide application in the field and pivotal role in image processing [

21].

This study focuses on identifying languages from printed and synthetic document images written in Amharic, Tigrigna, Awigna, and Geez, which are all written in Ethiopic script. Our aim is to investigate the identification of low-resource languages written in a similar script. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to address language identification from multilingual document images with similar script in the context of Ethiopian languages. Our research makes two key contributions: (i) investigation of various deep learning techniques to accurately predict the language from a low-resources document images written in Ethiopic script and provide a generic solution for the task and (ii) we present a multilingual Ethiopic script language dataset, which was manually annotated and generated from various websites and social media sites for four low-resourced Ethiopic languages.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows.

Section 2 presents a review of related literature.

Section 3 outlines the methodology used to address the language identification problem, along with the process model employed. In

Section 4, we present the experimental results of our study, which are based on the dataset we have created. Finally, in

Section 5, we conclude the paper by summarizing our findings and discussing future research directions.

2. Related Work

Language identification is the examination of different types of languages from a collection of documents. It is away to figure out what kind of natural language is present in the document. LID, can be performed in document images [

16,

22,

23,

24,

25] as well as text documents [

16,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Language identification can be performed on any language format, including speech, sign language, and handwritten text, handwritten text images [

31] and it is applicable to all types of data storage media, including digital as stated in [

10].

In today’s multilingual world, using documents in multiple languages is commonplace. To comprehend a document and use it in other automatic analyses, it is necessary to determine the language of the document. In multilingual settings, languages may have similar script but different writing styles, or similar language but different script, making differentiation difficult. As a result, language identification is receiving attention from researchers in order to address such issues. Language identification analyzes the extracted text of each document to determine the language in which it was written. It allows you to see how many languages are contained in each document as well as the percentages of each language. Language identification is the first step in subsequent steps of automatic document analysis in various areas, such as machine translation [

27], natural language preprocessing [

34], sentiment analysis, and OCR [

35]. Language identification from text documents and document images has piqued the interest of a number of researchers in this regard.

Managing multilingual documents presents a number of challenges, including script identification, language determination, text with varying character sets, reading direction, and the majority of document image noise. To this end, language based document image analysis is required in a multilingual environment. It facilitates browsing, searching, and accessing documents related to a specific language. Automatic language identification is critical in processing large volumes of document images, particularly when using for a multilingual OCR system and document image retrieval to obtain sorted document images, select specific OCRs, and search online collections of document images for those containing a specific language [

36].

The authors in [

28] have studied language identification on multilingual character window of textual document. Accordingly, language identification has to be performed in multilingual short and long textual document language identification. As part of their contribution, the authors gathered numerous documents from six datasets containing 131 languages, including HTML markup syntax, and prepared a dataset. In [

37], CNN and RNN are combined for language detection in such a way that CNN is followed by RNN. The authors were inspired by the difficulty of identifying language in social media texts, where casual styles, closely related language pairs, and code-switching are common. As a result, issues are investigated in a shared task for Language Identification in Code-Switched Data by employing a hierarchical neural network to learn character and contextualized word-level representations in order to make word-level language predictions. The author submitted labels for both Spanish-English and Arabic-MSA language pairs that were available (distinguishing Modern Standard Arabic from Arabic dialects).

The authors in [

26] developed a suitable technique for effective text-based language identification, focusing on seven Ethiopian languages: Afar, Amharic, Nuer, Oromo, Sidamo, Somali, and Tigrigna. They attempted to address the identification of languages in multilingual documents that contained this seven language per document. To accomplish this, they have chosen classic machine learning techniques such as the Nave Bayes classifier, SVM classifier, and Dictionary method. The authors demonstrate that there is no a standard corpus for research purposes, thus they created a document corpus with those seven languages per document. Then the data have separated to training and testing module. Then, they use n-gram of size 3 as a feature set for Nave Bayes classifier, SVM classifier algorithm training and stop word for dictionary based approach.

The experimental accuracy shows that the Nave Bayes classifier is 98.37% accurate, the SVM classifier is 99.53% accurate, and the Dictionary method is 90.53% accurate. However, the author demonstrates that incorrect categorization occurs during homogeneous document evaluation using a 3-n gram document corpus because the languages have similar script, making differentiation impossible. Textual or electronic based language identification is nearly complete in foreign-based linked jobs[3] [3]

https://bit.ly/3BAYgqr, such as [

16]. However, there are some challenging issues in document image language recognition. Aside from language recognition, OCR document inscription has proven difficult when the document is written in multiple languages. Because OCR converts document images into text that is understandable in a specific language, the document image language should have been recognized before any work was done. Though much research has been done on the recognition of well-known languages, little focus has been placed on automatic language identification for low-resourced languages.

The identification of languages from document images has been the focus of various researchers for different reasons. For example, language identification from document images has been implemented for OCR and NLP purposes [

34]. Similarly, [

25] attempts to determine the language on a document image using character shape coding analysis and bi-gram analysis after OCR is used. The author constructs word shape codes based on character extreme points and the quantity of horizontal word runs. After shape codes have been extracted, the degree of similarity between the document vector and the language templates is measured. However, language type detection and identification on multilingual document images is an addressed issue in the context of low-resourced language, especially Ethiopian languages.

In recent years, several researchers, including [

10,

25] and [

16], have attempted to identify languages from document images and texts. These researchers have used recognition based on script and transcribe to text, and then language identification is performed due to their language script being different. However, this method is generally not more effective as it is recognition-based identification.

While the detection of languages can be done on textual or electronic documents, it has become necessary to detect languages from document images in order to handle documents that are in the form of images. This is important for successive tasks such as document image retrieval, OCR, machine translation, and sentiment analysis. In order to detect languages on multilingual document images, researchers have used various approaches such as character, word, and text-line segmentation methods [

22,

38]. Among these approaches, text-line segmentation[

38] has been recommended as it requires less preprocessing steps.

In this paper, we have employed the text-line segmentation approach for multilingual document image language segmentation and detection. We have explored various pre-trained CNN models and compared them with versions trained from scratch.

3. Methodology

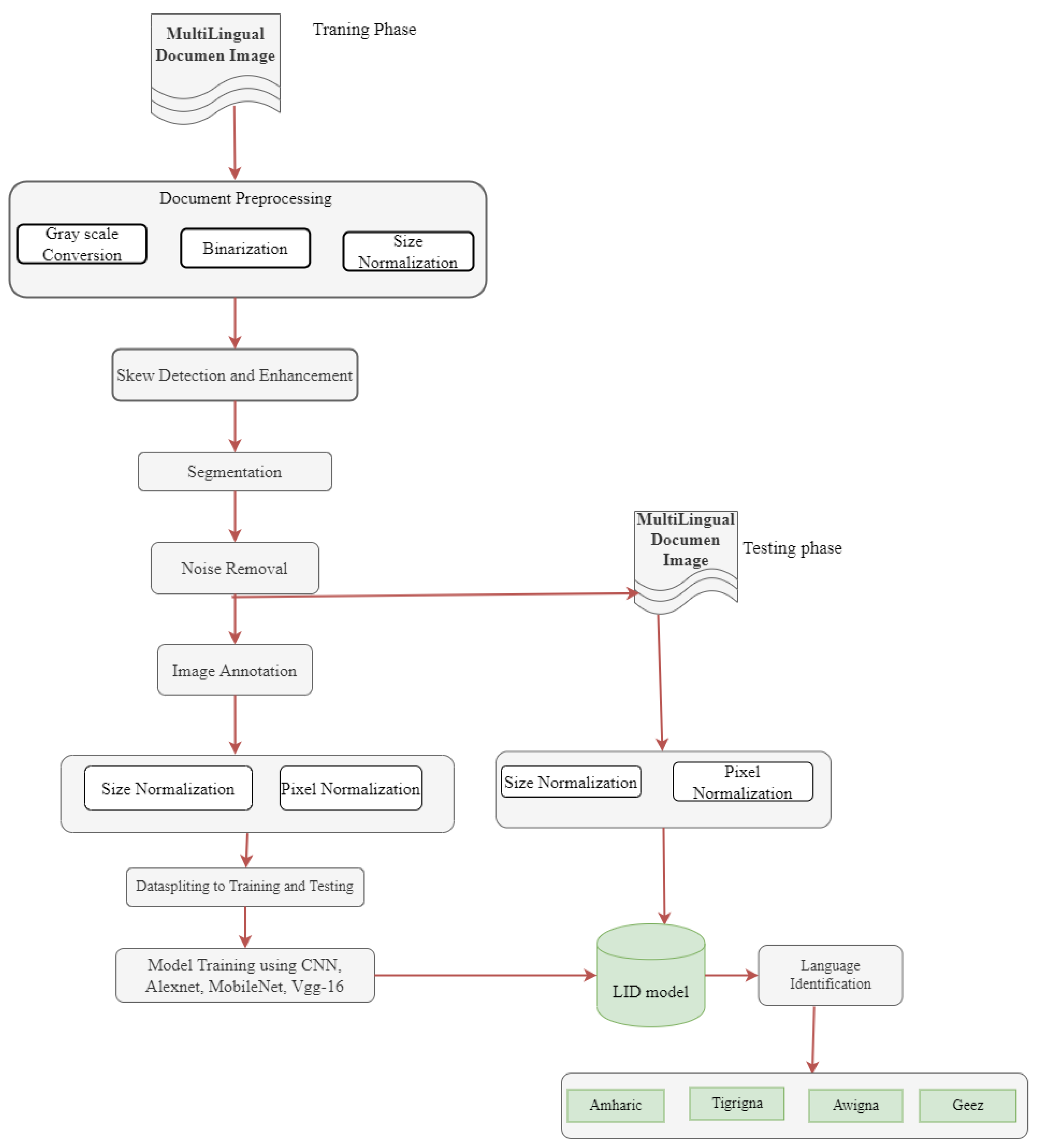

This section presents the development of our deep learning-based language identification model for Ethiopic scripts, including dataset preparation and model development, as outlined in

Figure 3

3.1. Dataset for Language Identification

The first step of the study was to gather data from various sources since there were limited standard datasets available for the intended objective. For collecting multilingual document images written in Ethiopic script, two settings were employed: (i) printed documents were gathered and scanned, and (ii) Ethiopic script texts were collected and converted into PNG format. The former dataset enables us to test our model in realistic settings, while the latter is a synthetic dataset created from several sources, such as Amhara Mass Media (AMICO) and BBC social media pages, and used for training our model.

This research utilized two data sets, namely printed and synthetic data sets, as listed below.

We used the printed document data set because our objective was to solve the challenge of languages that have similar scripts. For example, we used Ethiopian spiritual books, as depicted in

Figure 2, which allowed our system to perform language detection for two, three, or even four languages that have similar scripts.

The reason we used the synthetic data set is that electronic documents are becoming increasingly common, which poses a challenge for language detection. We segmented this data set based on text-line segmentation, where one page produced an average of 30-line images depending on the number of lines in the document. Overall, we preprocessed 24,444 printed segmented datasets and 97,012 synthetic segmented datasets for our model. From this collected document images, we used only 24,444 line segmented datasets in the first phase and balanced it with the printed dataset.

To enhance the quality of document images and improve overall performance in downstream tasks, we employed various preprocessing techniques, including size normalization, grayscale conversion, skew detection, binarization, and segmentation.

3.1.1. Document image size normalization:

Document images are collected in various settings, including devices and physical documents. In order to display document content in a clear format, the image size is rescaled to 2000 by 2000 after some adjustments.

3.1.2. Grayscale Normalization:

For language identification, document images should be in grayscale format. However, the collected document images are often in RGB format. These colored images are larger in size and have a higher chance of losing information during image processing. The cv2.cvtColor() method in OpenCV is used to convert the images to grayscale.

3.1.3. Skew Detection and Enhancement:

Printed document images may not be properly aligned, so image correction is required to obtain appropriate lines from document images. Canny edge detection is used to obtain the edges of text lines followed by Hough Transformation for skew detection and enhancement techniques. These methods are essential for proper document skew detection and angle selection.

3.1.4. Noise Removal:

Printed document images may contain various types of noise that compromise image quality. Filtering approaches, such as Median, Gaussian, Max, and Min filters, are employed to reduce noise in the image. Median filtering is selected for image preprocessing based on criteria for filtering methods that produce minimum Mean Square Error (MSE) and maximum Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR).

3.1.5. Document Binarization:

Document images are typically represented in a printed format with a white background and black text. Binary representation of documents is achieved by automatically selecting a threshold that distinguishes between foreground and background data. Simple thresholding values are implemented for document image binarization.

3.1.6. Segmentation:

Line-based segmentation is used to extract each individual language from the document. Horizontal projection profiles are used to divide lines in a document, and line-based segmentation is suitable for document image transcription and recognition problems. Active contour and morphological dilation are used to achieve text line segmentation.

3.2. Proposed System Architecture

The proposed system architecture outlines the development of a language identification model for four Ethiopic script languages using deep learning-based approaches.

Figure 3 depicts the proposed model architecture, which consists of several steps. The process starts with collecting multilingual document images of Ethiopic script from various sources, including synthetic and scanned or printed data, which are structured to form the dataset. The synthetic document images are manually preprocessed by removing superfluous words or quotations, as well as symbols and other language symbols. Then, automatic preprocessing techniques such as document skew detection, grayscale conversion, binarization, and normalizing are applied. The document images are then segmented using line segmentation methods and feed to the CNN models for classification.

Figure 3.

General Flow Diagram of the Proposed Model

Figure 3.

General Flow Diagram of the Proposed Model

To extract basic features and minimize storage consumption and feature engineering efforts for multilingual document image language identification, we used CNN layers. Classification was accomplished using a supervised machine learning technique, which categorizes document images based on training instances. This paper compares and evaluates the effectiveness of various pretrained deep learning models such as MobileNetV2, Vgg16, and AlexNet for detecting the four Ethiopian languages from their language script and shape. In addition, we employed CNN models trained from scratch for language identification.

3.3. Dataset Split and Model Evaluation Metrics

We compute the assessment result of a 70–30 % split following all preprocessing, as specified in the experiment; we noted good accuracy and a low loss score. As a result, the dataset was divided into a training set (70%) and testing set (30 %) for all trials conducted as part of this project. The test set was supplied to the model after the model had been trained using the four deep learning algorithms Mobile Net V2, Vgg16, CNN, and Alex Net. Finally, accuracy, recall, F-measure, and precision evaluation methodologies were used to assess the performance of our model prediction and also confusion matrix, a n x n matrix used to assess the effectiveness of a classification model, where N is the number of target classes, has been utilized. The deep learning model’s predictions are contrasted with the actual target values in the matrix to have a comprehensive understanding of the performance and types of faults of our identification model. To this end, we have used 4*4 matrix in four measurements i.e., true positive, true negative, false positive, false negative and consecutively to measure the accuracy, precession of developed prediction model performance. As we have stated the languages selected share the same script and this may make challenging to check their similarity or confusion and hence confusion matrix has a great role.

Accuracy: is defined as the ratio of the correctly recognized (either positive or negative) to the total number of samples.

Precision: (or Positive predictive value) proportion of predicted positives that are positive.

Recall: the proportion of actual positives that are predicted as positive

F1 score: conveys the balance between the precision and the recall.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

This section describes the experimental evaluation of the proposed method for the task of language identification from document images. The experiment is carried out in accordance with the architecture depicted in

Figure 3. To this end, the experiment goes through several stages, including data collection, preprocessing, dataset splitting, feature extraction via CNN, model building, training, testing and evaluation. Moreover, the experiments were conducted using two types of datasets: printed and synthetic.

4.1. Data Preparation

Once the required imgage documents acquired, the next step is to prepare the dataset so as to facilitate the overall process. The common data preparation techniques employed in this study are skew detection and enhancement for printed documents, segmentation,

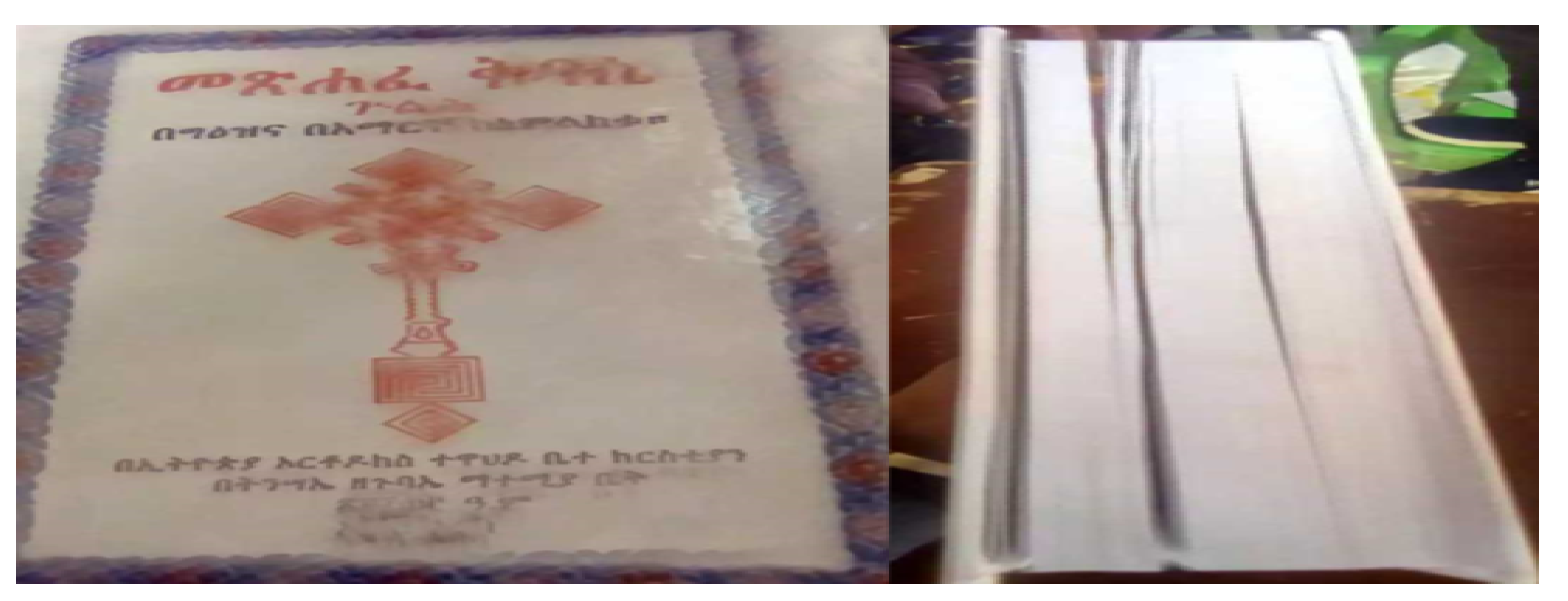

Skew Detection and Enhancement: Grayscale convergence, binarization, canny edge detection, and size normalization are all required steps in order to detect and improve skew. In addition, the Hough transformation was used to detect and improve skew in our document image dataset preparation. To extract characteristics from the same images, all characters are brought into a similar size platform via the normalization process, which transforms an image of random size such as (2339, 1654), (1654, 2339), and (2286, 2000), among others. The image size (2000,2000) was discovered to be the best size for detecting line edges easily. The chosen size image was then normalized and converted to grayscale. A grayscale image, also known as a two-level or bi-level image, is one in which the only colors are black and white. To accomplish this, we used thresholding techniques for binarization of multilingual document images. The first step in binarization is determining the grayscale threshold value and whether or not a pixel has a specific gray value. Simple thresholding piques our interest because it is used in a black background with white writing format and is also simple to use, as shown in Figure.

Figure 4.

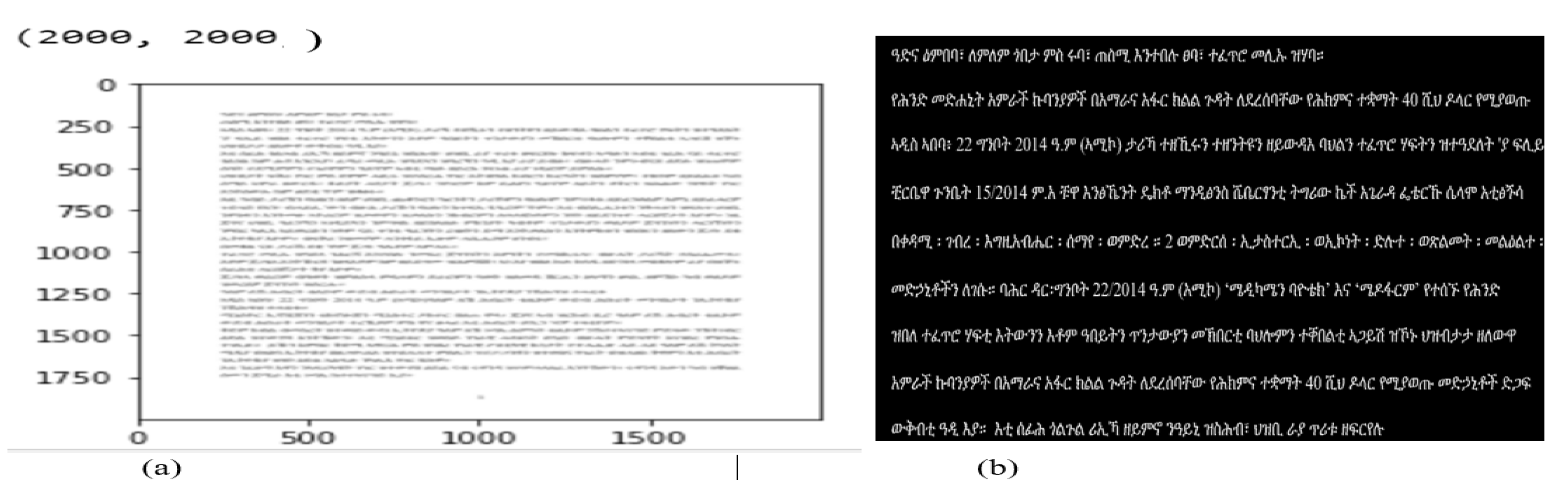

Segmentation We used text line segmentation approaches from among the various available image segmentation approaches because they produce better results than other segmentation techniques, such as text line, word, and character segmentation for document image analysis, as indicated in [

39].

Dilationis one of morphological image enhancement techniques which is applied to enlarge or thicken the foreground object [

40]. We used to join two disparate line flows on document image. We create a kernel matrix, which is composed only of ones, then move the kernel through the picture to dilate it. A kernel is more than a tiny matrix used for edge detection, sharpening, and bluring. Therefore, we have dilated intended text line from binarized image document.

Active contour: A curve connecting all continuous points (along the boundary) of the same hue or intensity. The contours in this situation serve as an effective tool for identifying and locating lines from document. Following grayscale, applying a threshold or clever edge detection to the black on white document image is the step before selecting the proper region of interest or line from the document. For the target object’s portions intended for segmentation, the active contour defines a distinct boundary or curvature. With the use of other related concepts, we were able to segment the multilingual document image for our study using Canny edge detection with the help of active contour. With the given edge detection operators applied to the same image, it is intended to identify glass surface defects [

41]. By using this technique, we have segmented number of multilingual document images in to number of line images. Both data set which are preprocessed before i.e., 880 printed document and 3360 synthetic or synthetic document image is become segmented based on text-line segmentation, one-page produce around 30-line image depending on lines exist in document than totally we have get preprocessed 24, 444 printed segmented dataset and 97, 012 synthetic segmented datasets for our model. Such techniques was adopted from [

31].

Figure 6.

Line-Based Segmented-Image

Figure 6.

Line-Based Segmented-Image

Due to computer storage constraints and to balance with printed datasets, we used only 24,444 line segmented and preprocessed datasets from such a large collection of datasets. Even with two computers and Google Collaborator via four email addresses, it cannot process more than this dataset. Finally, all manual preprocessing and segmentation resulted in a line-segmented image document for a study strategy. Because these segmented line images from the multilingual document will be used in our study, they must be divided into four categories. Furthermore, we used additional preprocessing approaches under the assumption that fabricated data documents are noise-free. However, after reading the entire data set, we applied several noise removal techniques to the image.

Noise Removal Images contain a variety of noises, and camera captured images frequently contain salt and pepper noise. To this end, removing image noise is a critical step in improving document image quality. Noise reduction algorithms should have been used to smooth the entire image away from areas of high contrast in order to reduce or eliminate blare visibility. To achieve this goal, we used median noise reduction methods.

Table 1.

Filtering Experiment

Table 1.

Filtering Experiment

| |

Noise Level |

|

|

| |

Low |

Medium |

High |

Average Value |

| Filtering technique |

MSE |

PSNR |

MSE |

PSNR |

MSE |

PSNR |

MSE |

PSNR |

| Median |

0.0055 |

22.5884 |

0.0062 |

22.0194 |

0.00629 |

22.0133 |

0.00602 |

22.2070 |

| Max |

0.00471 |

16.2310 |

0.0003 |

8.0905 |

0.0700 |

6.54609 |

0.0250 |

10.28921 |

| Min |

0.00055 |

12.3451 |

0.0005 |

8.9000 |

0.02882 |

21.7893 |

0.0099 |

16.31037 |

| Gaussian |

0.01536 |

18.1357 |

0.0153 |

18.1274 |

0.01579 |

18.0147 |

0.0155 |

18.09265 |

| Pick point= Minimum MSE and Maximum PSNR |

0.00602727 |

22.20704346 |

The experimental result revealed that median filter filtering technique has the lowest MSE and maximum PSNR values, which leads to the conclusion that it is the optimum filtering strategy for the remainder of the preprocessing steps in our research. The average MSE value in all noise levels is assessed to be 0.0060273 and the maximum PSNR value to be 22.2070435. Because median filtering has the lowest MSE value, the error density between the original grayscale image and the denoised image is the lowest between the picture indicated and the image origin. In addition, the PSNR number between the two images shows the peak signal-to-noise ratio in decibels (dB). Adaptive filtering produces better-quality reconstructed images since it has the highest PSNR value. Based on these, median filtering performs better in terms of noise reduction than other filtering approaches.

Size Normalization: Although documents are resized before segmentation, specific line segmented images size normalization are necessary pre-processing step that must happen after in order to prevent biased results and inaccurate predictions. The image resolution threshold value in this stage is the same for every picture data collection. Segmented line images have to be normalized in to appropriate size and pixel value. To this end, before going to normalize the image resizing, checking the size (width, height and channel) of image is requiring what type of images do we have after manually labeled all in line segmented data and stuffed to appropriate folder. We have experiment variety of size to get proper size for our segmented line.

4.2. Model Building Specification

After splitting the dataset into training and testing sets, we build the models using deep learning algorithms, namely Alex Net, Mobile Net, Vgg-16-CNN and custom. A number of hyper parameter tuning is performed for the purpose of regulating the order in which data enters, stored on, and leaves the network in sequenced manner. To implement these algorithms, we import several packages on to the Jupiter Notebook such as fit() method training and model evaluation parameters. The error or loss is computer using the categorical crossentropy, and the learning rate for each parameter is calculated using the Adam optimizer. Max pooling is applied for the purpose of down sampling of features during learning phase of model because, each language is founded from similar script. So max pooling is preferred pooling technique for the purpose of selecting the maximum feature map from dataset. As we are working on multinomial class labels, we have employed the Softmax function in the output layer. By using integer values ranging from 0 to 3, we labeled the four Ethiopic scripts classes in array format.

We employ the most popular model type, the sequential type, which enables us to build models layer by layer. In addition, the first layer demands that conv2d accept the input shape parameter to a custom-CNN and 3-pre-trained model, which is the input image’s size and channel; hence, in this study, we have passed the input image’s size, parameter (width, height, channel) (250, 50, 1). Furthermore, dropout (0.2) has been used after maxpooling in each algorithm chosen to prevent the overfitting and under fitting issues that are most frequently useful in machine learning. For the four deep learning algorithms, dense layer has been come with number of class units which means to what amount of class is classified these convolved and pooled features are to in annotated image. Therefore, we have declared the dense value with 4 class label or number of nodes in the layer.

4.3. Results

The experimental results obtained by applying deep learning models to two datasets, namely a dataset of synthetic document images and a dataset of printed documents. Typically, the batch size, epoch, and learning rate hyperparameters were tuned. To that end, we present three epochs (10, 16, 32), two learning rates (0.001, 0.0001), and two batch sizes (16, 32).

4.4. Experimentation on Printed Document Image Dataset

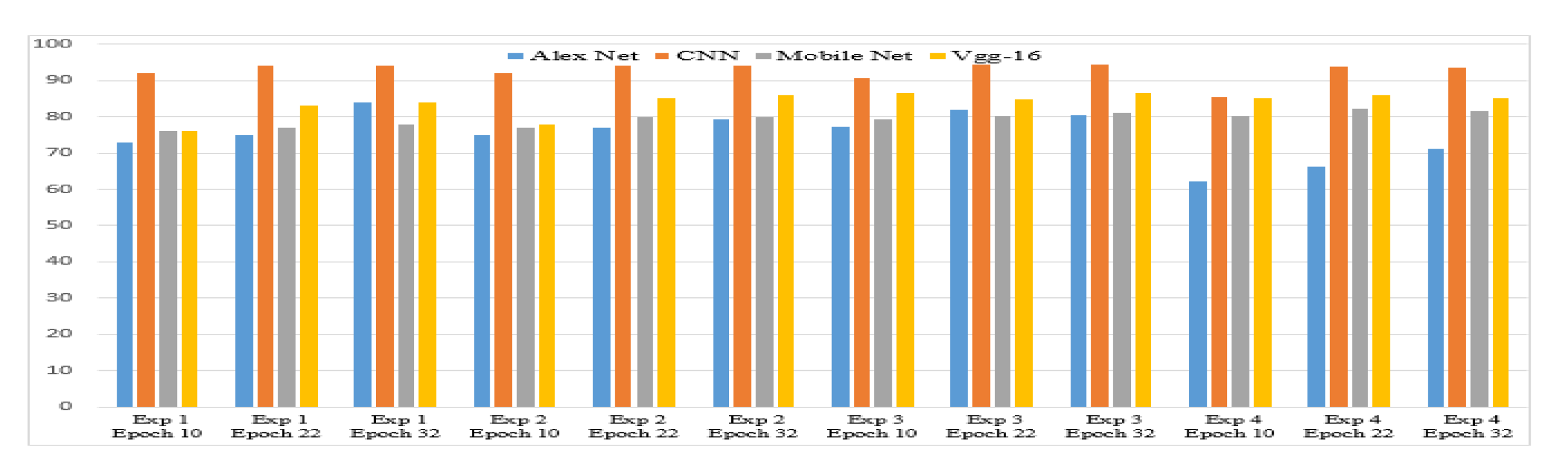

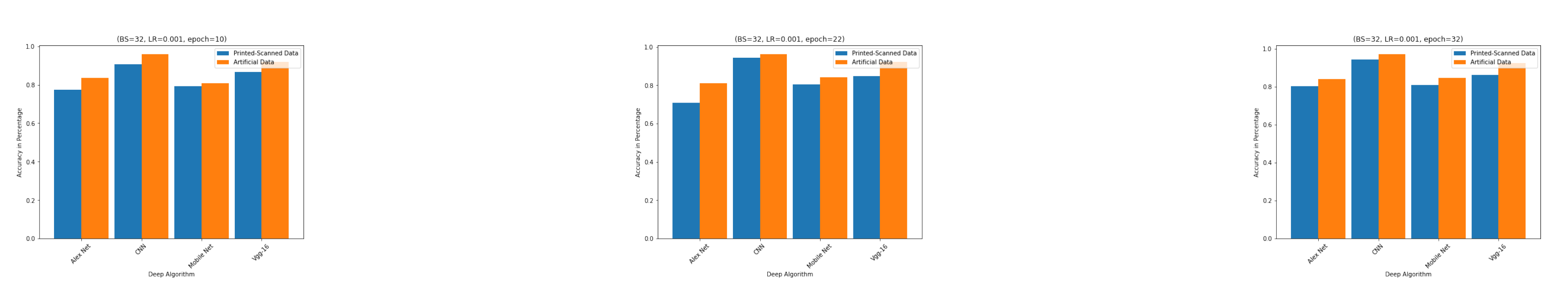

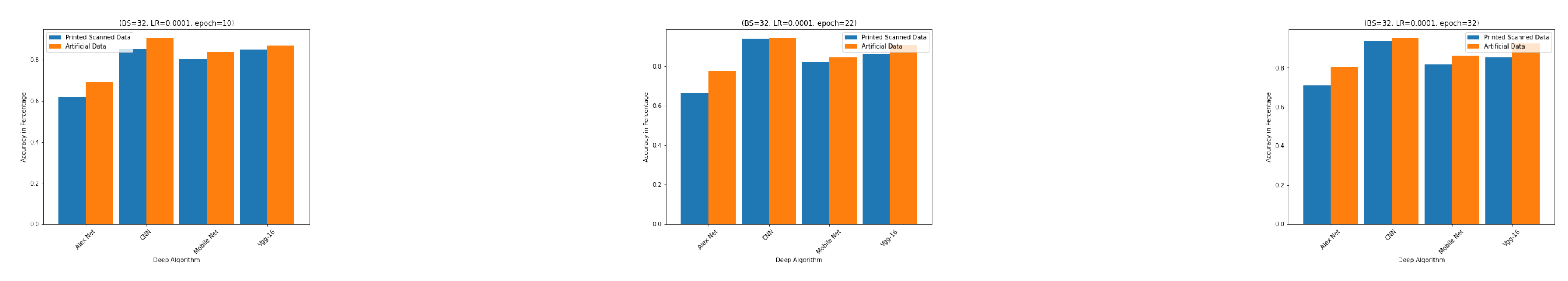

The main points observed from the four experimental settings on a data set of printed documents are as follows: (i) accuracy increases noticeably when the epoch is changed from 10 to 22, and (ii) accuracy generally decreases when the epoch is changed from 22 to 32, with the exception of Alex Net, the algorithm with the lowest performance.

Figure 7 provide a summary of the results from experiments 1-4. As a result, custom-CNN is the most effective algorithm, followed by Vgg-16, Mobile Net, and Alex Net. In all cases, custom-CNN has an accuracy rate of more than 90%, while the Vgg-16 has an accuracy of about 85%. The accuracy of Mobile Net and Alex Net algorithms oscillate between 76% and 82%, and 62% and 81% respectively. Experiment 3 has the highest accuracy for the best performer algorithm, with an epoch of 22, a batch size of 32, and a learning rate of 0.001. The custom-CNN also performed well in the same experiment using epoch 32. These are the two points where all the algorithms showed improved accuracies. More specifically, Alex Net had its best accuracy at epoch 22 while Vgg-16 and Mobile Net score its best accuracies at epoch 32 as compared to other experiments.

4.5. Experimentation on Synthetic Dataset

We evaluate the performance of the algorithms employed in this study using synthetic dataset. The rationale for using synthetic datasets is that we can generate large amounts of such data in a short period of time, allowing us to evaluate the performance of the algorithms with large amounts of data.

We used the same parameters as in previous experiments on a Printed document image dataset. In the first experiment (experiment 5), the batch size is set to 16, the learning rate is set to 0.001, the dropout is set to 0.02 and the epochs are 10, 22, and 32. Then the learning rate is reduced to 0.0001 on top of the first experiment in this section for the second experiment, in the third experimental setup the batch size is increased to 32 on top of experiment 1, and the learning rate is reduced to 0.0001 on top of experiment 3 in the final experimental setup. The results of these experiments are discussed below. In experiment 5, cusotm-CNN and Vgg-16 show higher accuracy than other algorithms in general. Mobile Net has the third most accurate prediction at epoch 10, and Alex Net has the third most accurate prediction at epoch 32. With the exception of the Mobile Net algorithm, which does not hold when moving from epoch 22 to 32, we can see an increase in accuracy as the epoch increases.

In experiment 6, we show the algorithms’ accuracy at epochs 10, 22, and 32 with a batch size of 16, a learning rate of 0.001, and a dropout of 0.02. We observe that custom-CNN outperforms other algorithms across all epochs, followed by Vgg-16 and Mobile Net. Except for epoch 32, Alex Net has the lowest accuracy across all epochs. All the algorithms show improvement when epoch is changed from 10 to 22. When compared to the trend on the previous epochs, only Alex Net indicates an increase for the highest epoch (i.e., epoch 32).

In experiment 7, we see that custom-CNN performs the best across all epochs, while Alex Net has the lowest prediction accuracy. Furthermore, we can notice that the accuracy of all the algorithms improved as epoch values increase except Alex Net. Alex Net exhibited unusual behavior, with its accuracy performance oscillating (moving up and down) as epoch values increased.

In general, our custom-CNN exhibits the better performance prediction overall for experiment 8. Vgg-16 has the second best prediction accuracy, followed by Mobile Net and Alex Net. Alex Net shows the lowest prediction accuracy. This experiment taught us the following lessons: (i) As epoch size increases, so does the performance of all algorithms; and (ii) the increment value from epoch 22 to epoch 32 is smaller for the best performer algorithm, whereas the others show a significant increment. In addition, we present experimental results comparison for a printed data document images and synthetic document image datasets on the different hyperparameters tuning such as the batch size, learning rate and epoch differences. For sake of comprehension, we have combined the parameters in four different ways ( hp1: BS=16, LR=0.001, hp2: BS=16, LR=0.0001, hp3: BS=32, LR=0.001 and hp4: BS=32, LR=0.0001).

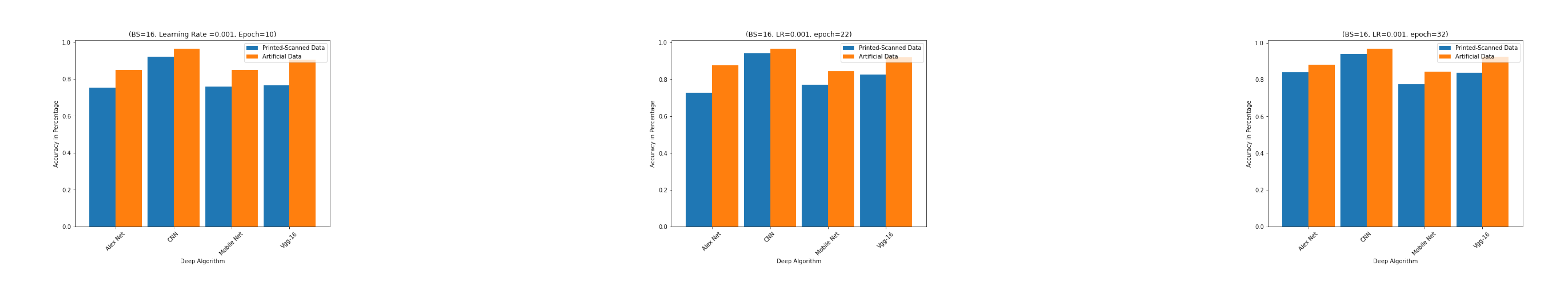

First we note that our custom-CNN outperforms other algorithms across all epochs for both datasets, followed by Vgg-16 and Alex Net for hp1 as indicated in

Figure 8. Mobile Net has the lowest accuracy for synthetic datasets across all epochs. It is similar to the printed datasets except at epoch 22, where Mobile Net outperforms Alext Net. It is also clear that all algorithms perform better on a synthetic dataset than on a dataset of printed document images across all images.

We can observe a similar result on hp2 depicted in

Figure 9 for both datasets. Custom-CNN and Vgg-16 show higher accuracy than other algorithms in general. Mobile Net and Alex Net show the third and the fourth most accurate predictions. However, Mobile Net and Alex Net behave differently. For example, Mobile Net outperforms Alex Net at epochs 10 and 22, but Alex Net outperforms at epoch 32.

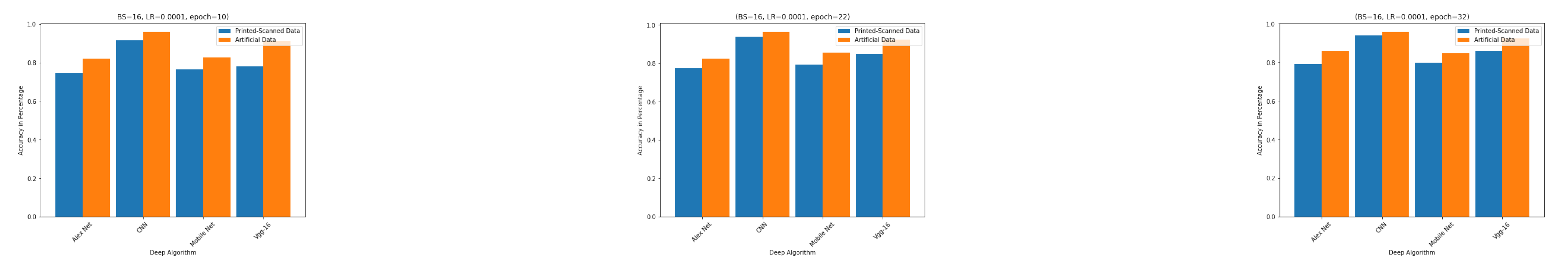

When both printed and synthetic datasets are used for hp3, as shown in

Figure 10, the algorithms perform better on the synthetic datasets. CNN outperforms all algorithms, with Vgg-16 coming in second. On average, Mobile Net and Alex Net have similar prediction accuracy. As compared to hp1, all algorithms show increase in prediction accuracy as the batch size increases for both datasets except Alex Net. Alex Net increases for printed datasets but decreases for artificial datasets.

hp4 exhibits similar behavior to the previous settings, i.e., all algorithms perform better on synthetic datasets. On both datasets, custom-CNN continues to perform better than Vgg-16 as the top algorithm. Mobile Net is the third best performer algorithm. Alex Net has typically the worst prediction performance in this setup. When the performance results obtained in this setup are compared to hp2, all algorithms show a decrease in prediction performance.

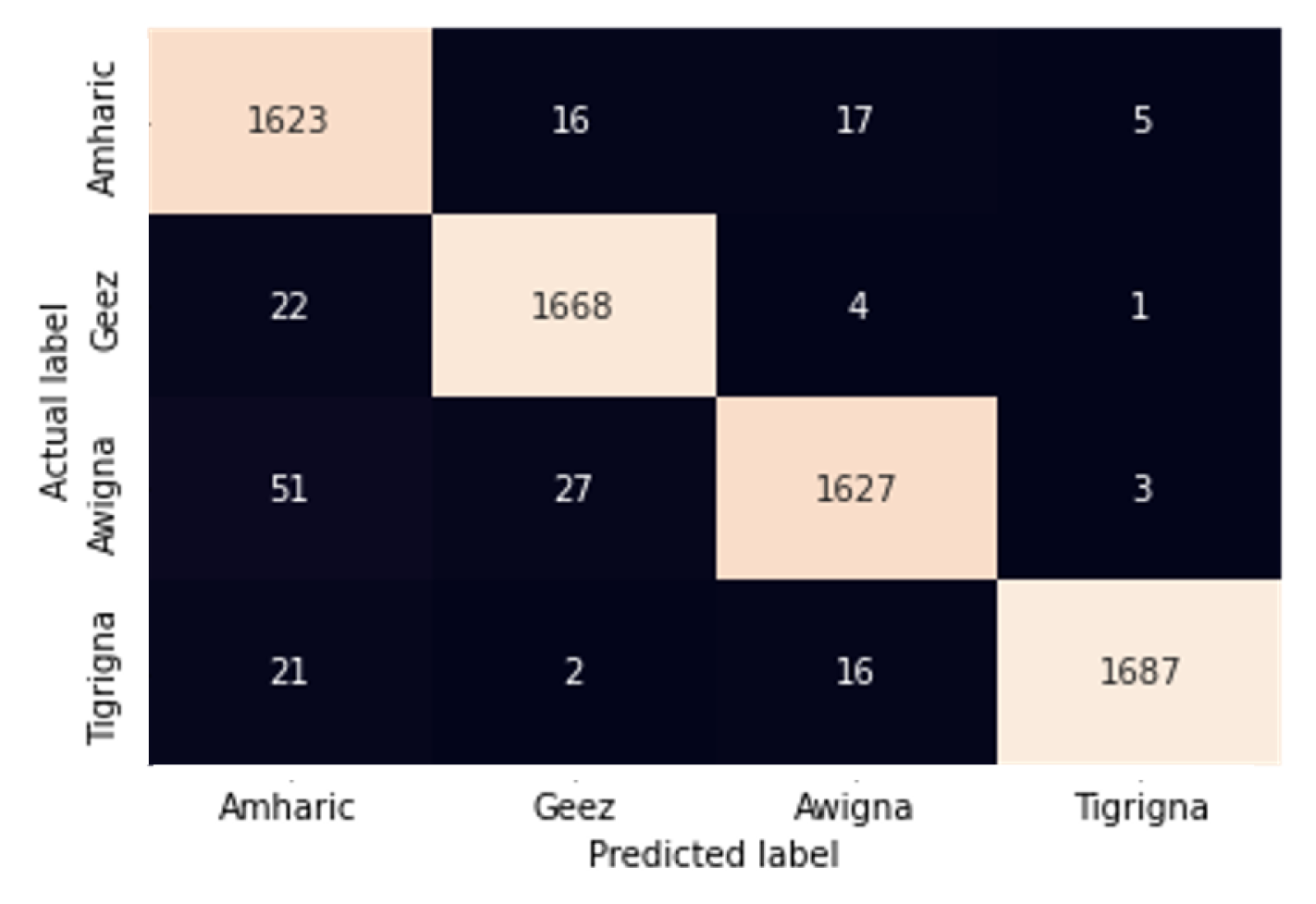

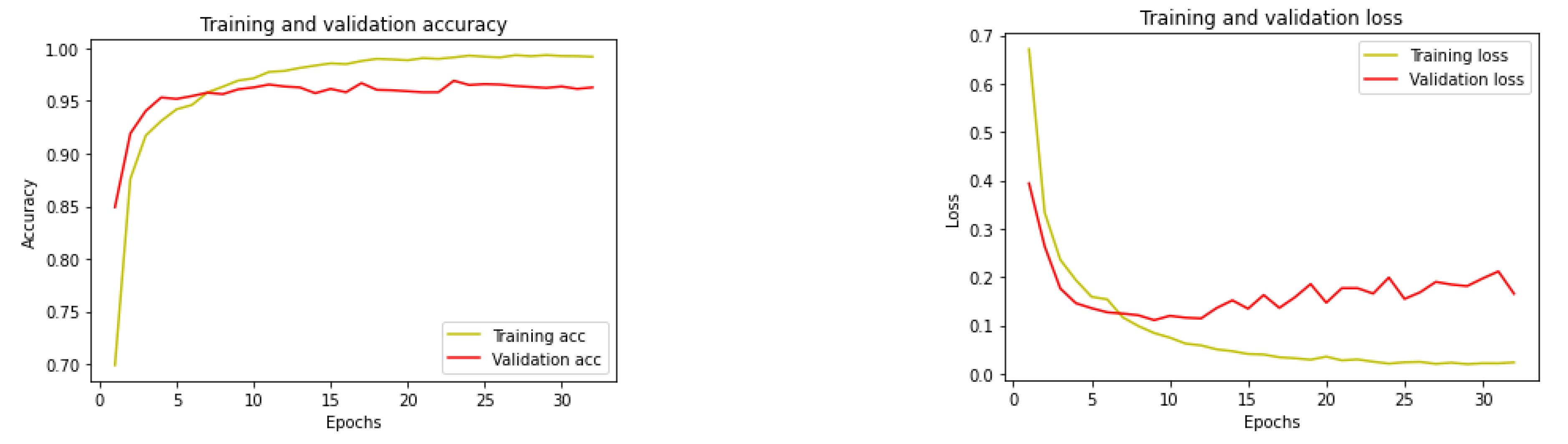

4.5.1. Experiment with the Best Model

To evaluate the effect of dataset quantity on the performance of the selected model, we examined further experiment. To this end, an experiment was conducted on a dataset of 32,000 using custom-CNN with the experimental parameters of batch size 32, learning rate 0.001 and epoch 32 on a dataset size of 32,000 document images. Accordingly, an accuracy of 97.27% on the synthetic document images dataset is registered. More specifically, the model was tested with 4480 sample images and correctly classified 4458 of them, i.e., 1077, 1078, 1058, and 1110 were correctly classified as Amharic, Geez, Awigna, and Tigrigna, respectively, as depicted in the confusion matrix in

Figure 12. As the number of epochs increases, training accuracy outperforms validation accuracy. Similarly, as the number of epochs increases, validation loss grows larger and exceeds training loss.

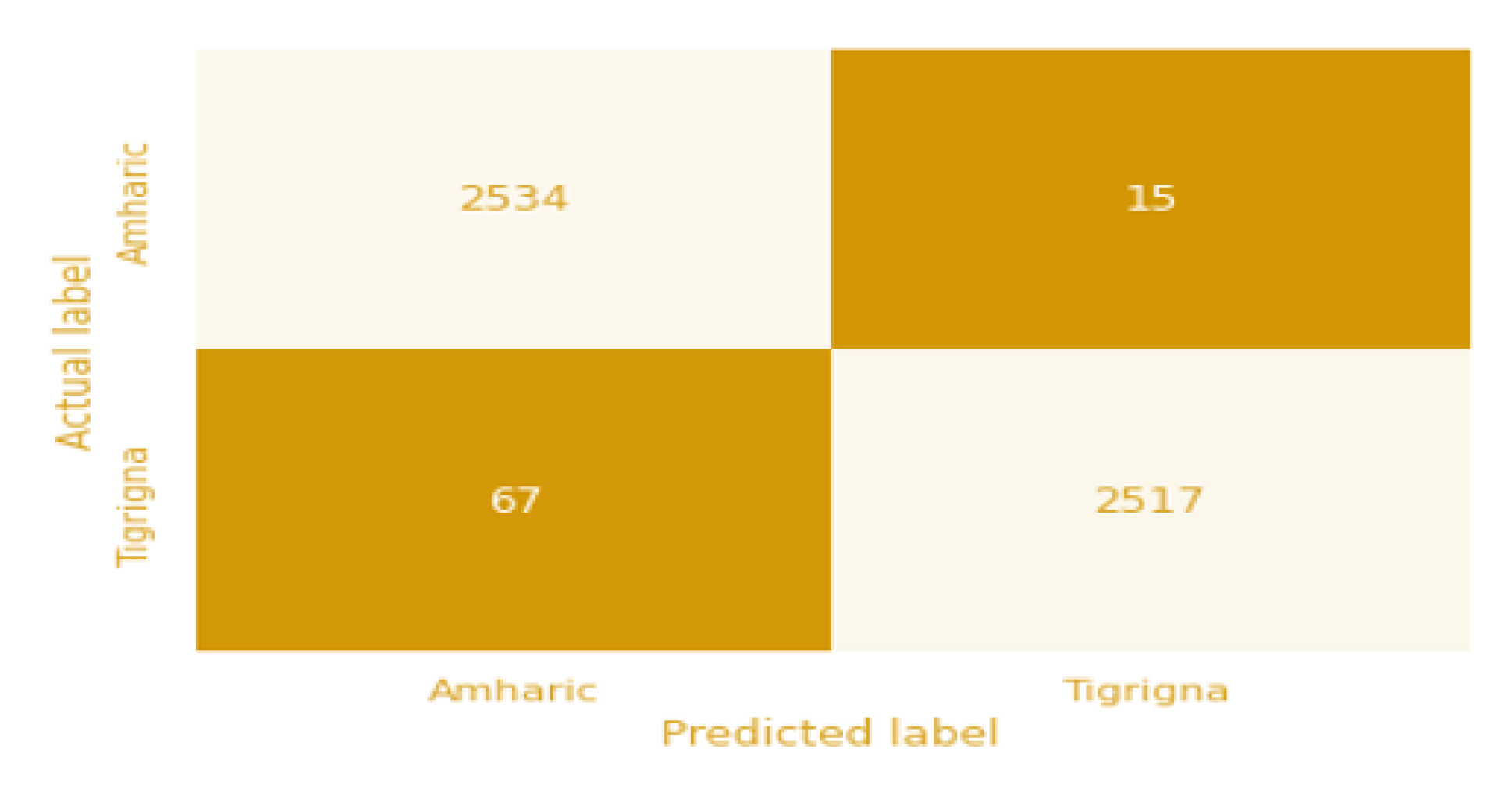

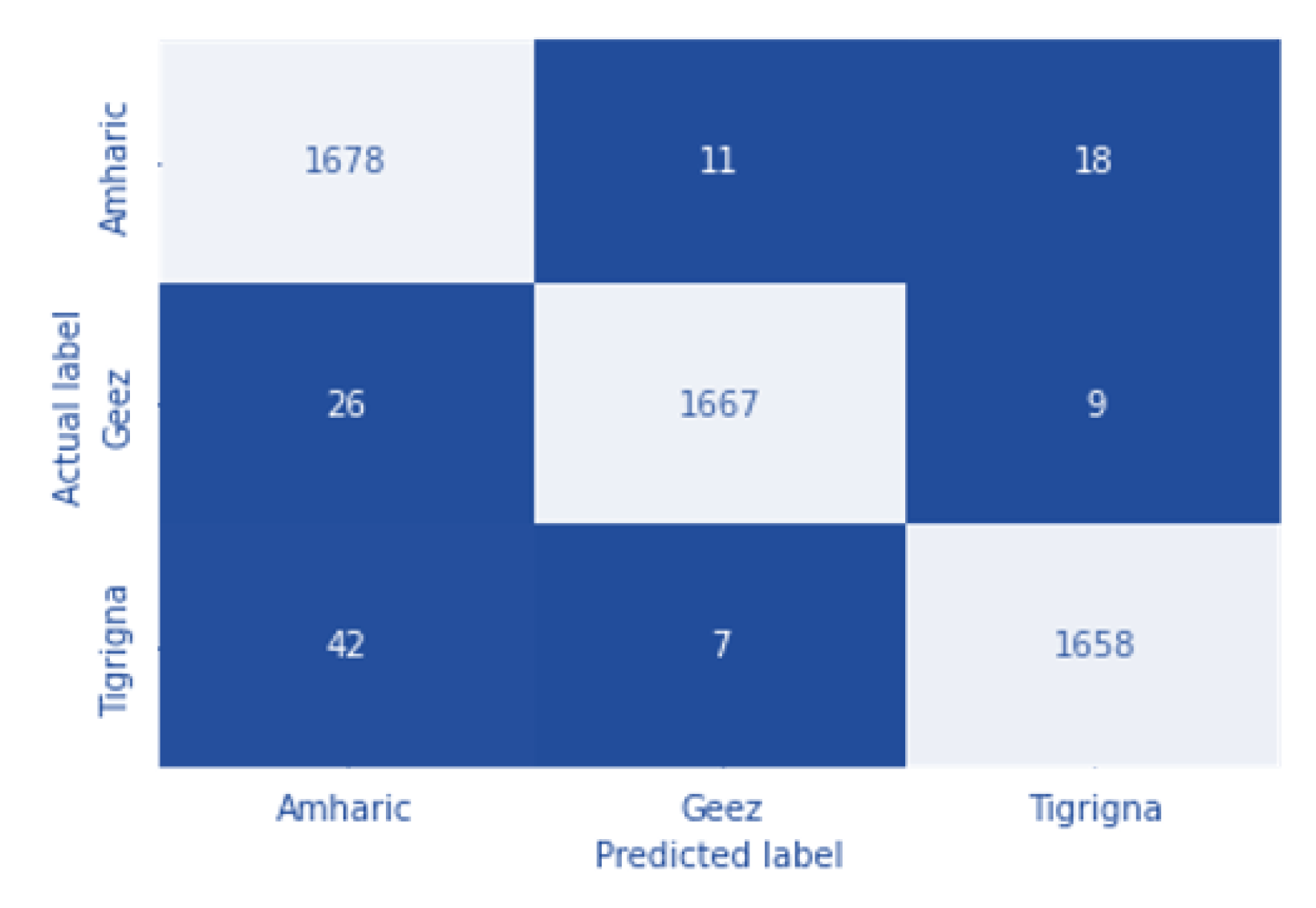

We further conducted an experiment to asses the performance of the chosen model by examining the effect of language distribution. To this end, we conducted experiments on two and three-language datasets. The languages were selected on the basis of the individual accuracy of the algorithm measured in previous experiments. The document images of the Ethiopic scripts Amharic, Tigrigna, and Geez are chosen for this purpose.

As shown in

Figure 13, the algorithm correctly predicts 2534 Amharic document images as Amharic and 2517 Tigrigna document images as Tigrigna. However, 15 Amharic document images and 67 Tigrigna document images were misclassified. As a result, the overall accuracy of the algorithm on this dataset is 98.4%. The validation and training accuracy, as well as the training and validation losses. Accordingly, the training accuracy shows increment as the the number of epochs increase whereas the validation accuracy sometimes increases and sometimes decreases. Training loss decreases significantly as epoch increases, whereas validation loss exhibits inconsistent behavior.

We performed experiment on a three-language document images consisting of Amharic, Tigrigna and Geez. The result of this experiment shows an accuracy of 97.79%. The confusion matrix as well as the training and validation accuracy and losses are depicted in

Figure 14. Similarly, we conducted experiments on Amharic, Tigrigna and Geez language documents. This experiment produces a result of result of 97.8% accuracy. The confusion matrix, as well as the training and validation accuracy and losses are depicted in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, respectively. As the epoch size increases, the algorithm’s training and validation accuracy improves while its loss decreases.

Testing the effect of language distribution on the performance of the chosen algorithm is one of the focus of the experiments in this section. The experimental result reveals that language distribution and performance of prediction performance correlated in such a way that accuracy decreases as the number of languages addressed increases. The stated behavior of the result is shown in

Table 2. The algorithm performs better when fewer languages are used rather than a combination of more languages, as shown in the table.

4.6. Discussion

We conducted extensive experiments on printed and synthetic document images using a custom-CNN and pretrained models across diverse experimental settings. In general, custom-CNN has been found the best performer model, as shown in Table 3. The experimental parameters that produce the best results are batch size 32, learning rate 0.001, and epoch 32 on the synthetic dataset. The pre-trained models perform lower as compared to custom-CNN and achieve their respective best results in different experimental settings. Vgg-16, for example, performs best when the batch size is 16, the learning rate is 0.001, and the epoch is 32. The Mobile Net and Alex Net models perform best with batch sizes of 16 and 32, learning rates of 0.001 and 0.0001, and epoch 32, respectively. To this end, the batch size 32, learning rate 0.001, and epoch 32 settings allow the majority of algorithms to perform optimally.

Custom-CNN is the best model for detecting the language of Ethiopic script document images. We achieved an accuracy of 97.11% on synthetic and 94.45% accuracy on printed document images. Both results were obtained by employing CNN at batch sizes of 32, learning rates of 0.001, and epochs of 32 and 22, respectively.

We investigated the effect of dataset size on performance using the best performer algorithm, i.e., CNN. To this end, we increased the document image sizes from 24, 444 to 32,000, and we discovered that an improved accuracy of 97.27%. Even though more data leads to higher accuracy, we only saw a minor improvement in our case. We wanted to experiment on more datasets, but due to limited resources, we could not process more than 32, 000 datasets. The quality of the document images has a clear impact on the performance of the algorithms, as all of them perform better in synthetic document image datasets. we have explored the effect of language distribution. To this end, we conducted experiments with various combinations of the four languages, such as a 2-language set (Amharic-Tigrigna), a 3-language set (Amharic-Tigrigna-Geez), and a 4-language set. As a result, better results are obtained with fewer language combinations. In this regard, the 2-language experiment outperforms the 3- and 4-language experiments. Similarly, the 3-language experiment outperforms the 4-language experiment in similar settings.

In general, we have also compared the outcomes of our work’s language identification to earlier language identification performed in Ethiopic script by Biruk Tadesse [

26]. Accordingly, we obtained a testing accuracy score of 97.11% percent, compared to Birku Tadesse’s score of 99.53% on the textual data set. Biruk’s success can be attributed to the textual dataset’s which are simpler nature to identify. In addition, more than half of the languages that he has identified lack a script that is similar, making it simple to identify them. Contrarily, in our work, LID is carried out using document photos, and the language also has a comparable script, making detection difficult.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we addressed the problem of language identification in low-resource multilingual document images written in the same script, and introduced a dataset for training and testing such models. We scanned, preprocessed, and segmented document images in Ethiopic script using various

techniques, including text-line based segmentation and CNN-based feature extraction. To find the best model for this task, we conducted extensive experiments using CNN and pre-trained deep learning techniques such as AlexNet, MobileNet, and VGG-1. The results showed that CNN outperformed the pre-trained deep learning models employed in this study, while the Vgg-16 pretrained model performs better than other pretrained models. The best performing model was able to identify languages in mixed document images with an accuracy of 97.27% on 9,600 test images. It is important to note that the document images considered in this study consisted of line texts written with one language, and our model cannot identify if languages are mixed in a single line, nor can it segment and detect properly if documents contain mixed-up formulas, graphs, and other items. Therefore, as part of future research, we will leverage CNN for language identification from document images as a step towards fully automated downstream tasks such as OCRs, document image retrievals, and machine translation. Moreover, we will consider developing a language identification module in different scripts and languages, as well as including handwritten document images to achieve full-fledged language identification from document images.