Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Cellular Senescence

Schizophrenia Outcome Studies

The ”Love Hormone” and The Fat

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor, the New Kid on the Block

Potential Interventions

Senotherapeutics

| Senolytic drugs | Source | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaempferol | Fruits and vegetables | GSK-3 beta inhibitor | [78] |

| Berberine | Oregon grape, phellodendron, and tree turmeric | Ceramide inhibitor | [79]. |

| Lycopene | Grape skin, guava, grapefruit, blueberries, and tomatoes | Scavenging of reactive oxygen species, enhancement of detoxification systems | [80]. |

| Fisetin | Strawberries, onions, apples, mangoes, persimmons, and kiwis | inhibiting the activity of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and MAPK. | [81] |

| Senomorphic drugs | |||

| Rapamycin | bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus | mTOR inhibition | [82]. |

| Acarbose | Soil bacteria | PPARγ upregulation | [83]. |

| SIRT-1 | Grapes, berries, apples, and other fruits | Lowers oxidative stress | [84] |

| Fluvastatin and Valsartan | Synthetic | Increase telomerase activity | [85]. |

| KU-60019 | Synthetic | Improves mitochondrial function | [86]. |

Barrier Enhancers

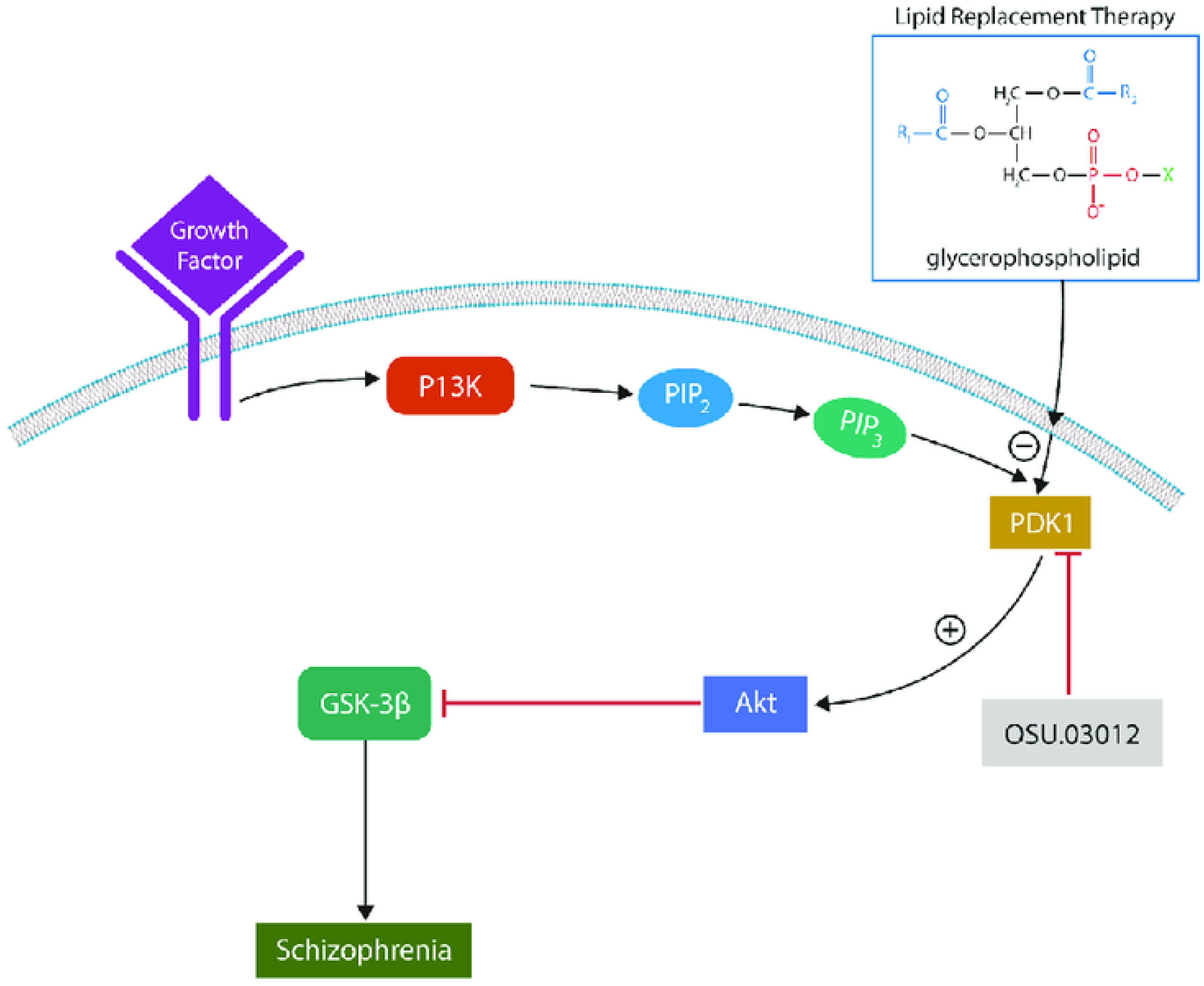

OSU 03012 and Other PDK1 Inhibitors

Conclusions

References

- Simanjuntak Y, Liang JJ, Lee YL, Lin YL. Japanese Encephalitis Virus Exploits Dopamine D2 Receptor-phospholipase C to Target Dopaminergic Human Neuronal Cells. Front Microbiol. 2017 Apr 11;8:651. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Liu Y, Zhang J, Wu X, Li X. Oxytocin increases pregnancy rates after fixed-time artificial insemination in Kazak ewes. Reprod Domest Anim. 2021 Jun;56(6):942-947. [CrossRef]

- KNIGHT, T. W. (1974). THE EFFECT OF OXYTOCIN AND ADRENALINE ON THE SEMEN OUTPUT OF RAMS. Reproduction, 39(2), 329-336. Retrieved Nov 12, 2024, from . [CrossRef]

- Wang SC, Zhang F, Zhu H, Yang H, Liu Y, Wang P, Parpura V, Wang YF. Potential of Endogenous Oxytocin in Endocrine Treatment and Prevention of COVID-19. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 May 3;13:799521. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson JR, McMahon EK, Boner W, Haussmann MF. Oxytocin administration prevents cellular aging caused by social isolation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019 May;103:52-60. [CrossRef]

- Winkler-Dworak M, Zeman K, Sobotka T. Birth rate decline in the later phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of policy interventions, vaccination programmes, and economic uncertainty. Hum Reprod Open. 2024 Sep 10;2024(3):hoae052. [CrossRef]

- Ullah MA, Moin AT, Araf Y, Bhuiyan AR, Griffiths MD, Gozal D. Potential Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Future Birth Rate. Front Public Health. 2020 Dec 10;8:578438. [CrossRef]

- Shuid AN, Jayusman PA, Shuid N, Ismail J, Kamal Nor N, Mohamed IN. Association between Viral Infections and Risk of Autistic Disorder: An Overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Mar 10;18(6):2817. [CrossRef]

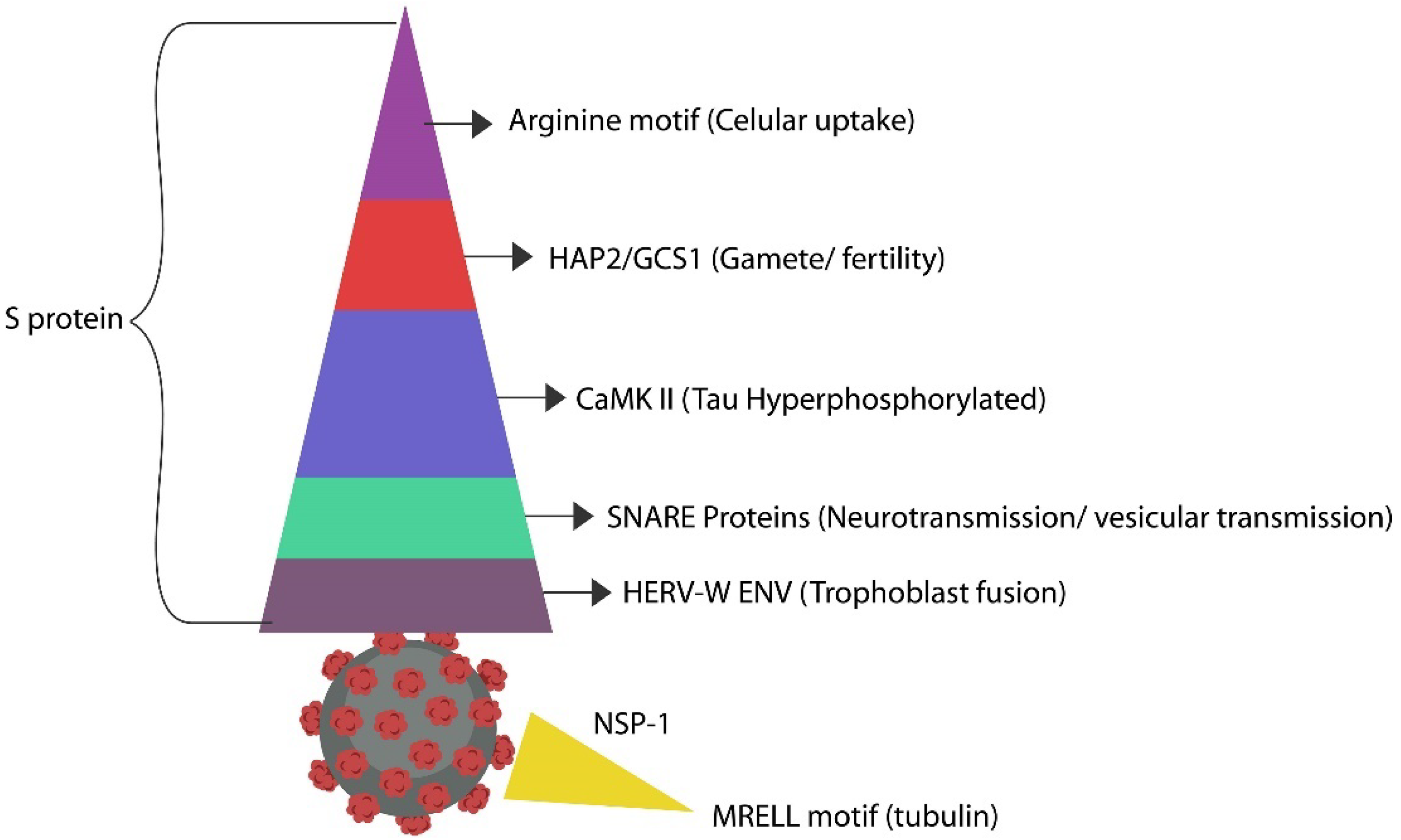

- Leboyer M, Tamouza R, Charron D, Faucard R, Perron H. Human endogenous retrovirus type W (HERV-W) in schizophrenia: A new avenue of research at the gene-environment interface. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013 Mar;14(2):80-90. [CrossRef]

- Kolocouris A, Spearpoint P, Martin SR, Hay AJ, López-Querol M, Sureda FX, Padalko E, Neyts J, De Clercq E. Comparisons of the influenza virus A M2 channel binding affinities, anti-influenza virus potencies and NMDA antagonistic activities of 2-alkyl-2-aminoadamantanes and analogues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008 Dec 1;18(23):6156-60. [CrossRef]

- Vasilevska, V., Guest, P.C., Bernstein, HG. et al. Molecular mimicry of NMDA receptors may contribute to neuropsychiatric symptoms in severe COVID-19 cases. J Neuroinflammation 18, 245 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, Stanton C, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Minireview: Gut microbiota: The neglected endocrine organ. Mol Endocrinol. 2014 Aug;28(8):1221-38. [CrossRef]

- Brown JM, Hazen SL. The gut microbial endocrine organ: Bacterially derived signals driving cardiometabolic diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:343-59. [CrossRef]

- Mu Q, Tavella VJ, Luo XM. Role of Lactobacillus reuteri in Human Health and Diseases. Front Microbiol. 2018 Apr 19;9:757. [CrossRef]

- Du T, Lei A, Zhang N, Zhu C. The Beneficial Role of Probiotic Lactobacillus in Respiratory Diseases. Front Immunol. 2022 May 31;13:908010. [CrossRef]

- Danhof HA, Lee J, Thapa A, Britton RA, Di Rienzi SC. Microbial stimulation of oxytocin release from the intestinal epithelium via secretin signaling. Gut Microbes. 2023 Dec;15(2):2256043. [CrossRef]

- Sheitman BB, Knable MB, Jarskog LF, Chakos M, Boyce LH, Early J, Lieberman JA. Secretin for refractory schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004 Feb 1;66(2-3):177-81. PMID: 15061251. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Rodriguez A, Mani SK, Handa RJ. Oxytocin and Estrogen Receptor β in the Brain: An Overview. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2015 Oct 15;6:160. [CrossRef]

- Wiegand V, Gimpl G. Specification of the cholesterol interaction with the oxytocin receptor using a chimeric receptor approach. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012 Feb 15;676(1-3):12-9. [CrossRef]

- Omolaoye, T.S.; Halabi, M.O.; Mubarak, M.; Cyril, A.C.; Duvuru, R.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Du Plessis, S.S. Statins and Male Fertility: Is There a Cause for Concern? Toxics 2022, 10, 627. [CrossRef]

- Di Stasi SL, MacLeod TD, Winters JD, Binder-Macleod SA. Effects of statins on skeletal muscle: A perspective for physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2010 Oct;90(10):1530-42. [CrossRef]

- Morofuji Y, Nakagawa S, Ujifuku K, Fujimoto T, Otsuka K, Niwa M, Tsutsumi K. Beyond Lipid-Lowering: Effects of Statins on Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases and Cancer. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022 Jan 26;15(2):151. [CrossRef]

- Yuta Aoki, Hidenori Yamasue, Reply: Does imitation act as an oxytocin nebulizer in autism spectrum disorder?, Brain, Volume 138, Issue 7, July 2015, Page e361. [CrossRef]

- Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Aug 26;105(34):12569-74. [CrossRef]

- Svalastog AL, Martinelli L. Representing life as opposed to being: The bio-objectification process of the HeLa cells and its relation to personalized medicine. Croat Med J. 2013 Aug;54(4):397-402. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y., Kim, S.Y. Endothelial senescence in vascular diseases: Current understanding and future opportunities in senotherapeutics. Exp Mol Med 55, 1–12 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Morioka S, Maueröder C, Ravichandran KS. Living on the Edge: Efferocytosis at the Interface of Homeostasis and Pathology. Immunity. 2019 May 21;50(5):1149-1162. [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou E, Gaughran F, Smith S. Schizophrenia as segmental progeria. J R Soc Med. 2011 Nov;104(11):475-84. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson JR, McMahon EK, Boner W, Haussmann MF. Oxytocin administration prevents cellular aging caused by social isolation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019 May;103:52-60. [CrossRef]

- Wang SC, Zhang F, Zhu H, Yang H, Liu Y, Wang P, Parpura V, Wang YF. Potential of Endogenous Oxytocin in Endocrine Treatment and Prevention of COVID-19. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 May 3;13:799521. [CrossRef]

- Welch MG, Margolis KG, Li Z, Gershon MD. Oxytocin regulates mice's gastrointestinal motility, inflammation, macromolecular permeability, and mucosal maintenance. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307(open in a new window)(8(open in a new window)):G848–62. [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Sun X, Wang Z, Song M, Zhang Z. Regulation of social behaviors by p-Stat3 via oxytocin and its receptor in the nucleus accumbens of male Brandt's voles (Lasiopodomys brandtii). Horm Behav. 2020 Mar;119:104638. [CrossRef]

- An, X., Sun, X., Hou, Y. et al. Protective effect of oxytocin on LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice. Sci Rep 9, 2836 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Catts, V., Sheedy, D. et al. Cortical grey matter volume reduction in people with schizophrenia is associated with neuro-inflammation. Transl Psychiatry 6, e982 (2016). [CrossRef]

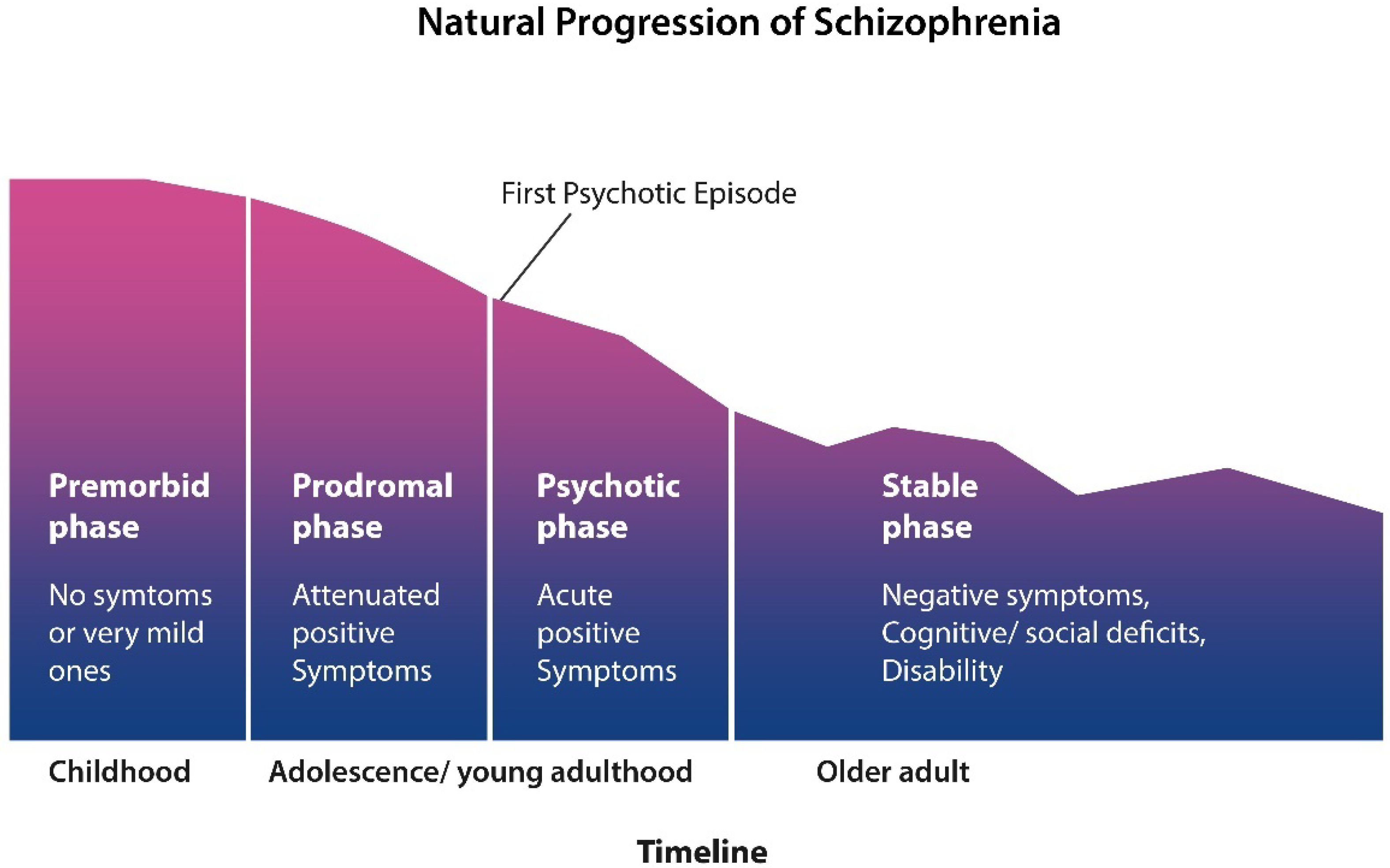

- Lewis DA, Lieberman JA. Catching up on schizophrenia: Natural history and neurobiology. Neuron. 2000 Nov;28(2):325-34. PMID: 11144342. [CrossRef]

- Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS, Haznedar MM, Newmark R, Goldstein KE, Zelmanova Y, Glanton CF, Torosjan Y, New AS, Lo JN, Mitropoulou V, Siever LJ. Cortical gray and white matter volume in unmedicated schizotypal and schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2008 Apr;101(1-3):111-23. [CrossRef]

- Ho B, Andreasen NC, Ziebell S, Pierson R, Magnotta V. Long-term Antipsychotic Treatment and Brain Volumes: A Longitudinal Study of First-Episode Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):128–137. [CrossRef]

- Momenabadi, S., Vafaei, A.A., Bandegi, A.R. et al. Oxytocin Reduces Brain Injury and Maintains Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity After Ischemic Stroke in Mice. Neuromol Med 22, 557–571 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Saffari M, Momenabadi S, Vafaei AA, Vakili A, Zahedi-Khorasani M. Prophylactic effect of intranasal oxytocin on brain damage and neurological disorders in global cerebral ischemia in mice. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2021 Jan;24(1):79-84. PMID: 33643574. [CrossRef]

- Holm, M.; Taipale, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Mitterdorfer-Rutz, E. Employment among people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: A population-based study using nationwide registers. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 143, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed].

- Lévesque, I.S.; Abdel-Baki, A. Homeless youth with first-episode psychosis: A 2-year outcome study. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 216, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

- Davidson, L.; Schmutte, T.; Dinzeo, T.; Andres-Hyman, R. Remission and Recovery in Schizophrenia: Practitioner and Patient Perspectives. Schizophr. Bull. 2007, 34, 5-8.

- Stone WS, Phillips MR, Yang LH, Kegeles LS, Susser ES, Lieberman JA. Neurodegenerative model of schizophrenia: Growing evidence to support a revisit. Schizophr Res. 2022 May;243:154-162. [CrossRef]

- Leucht, S.; Lasser, R. The Concepts of Remission and Recovery in Schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry 2006, 39, 161–170.

- Liberman, R.P.; Kopelowicz, A.; Ventura, J.; Gutkind, D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2002, 14, 256–272.

- Leppien E, Mulcahy K, Demler TL, Trigoboff E, Opler L. Effects of Statins and Cholesterol on Patient Aggression: Is There a Connection? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018 Apr 1;15(3-4):24-27.

- B.A. Golomb, T. Kane, J.E. Dimsdale, Severe irritability associated with statin cholesterol-lowering drugs, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 97, Issue 4, April 2004, Pages 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Albavera L, Domínguez-Pérez M, Medina-Leyte DJ, González-Garrido A, Villarreal-Molina T. The Role of the ATP-Binding Cassette A1 (ABCA1) in Human Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Feb 5;22(4):1593. [CrossRef]

- Every-Palmer S, Souter V. Low vitamin D levels found in 95 % of psychiatric inpatients within a forensic service. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;49(4):391-392. [CrossRef]

- De Berardis D, Marini S, Piersanti M, Cavuto M, Perna G, Valchera A, Mazza M, Fornaro M, Iasevoli F, Martinotti G, Di Giannantonio M. The Relationships between Cholesterol and Suicide: ASen P, Adewusi D, Blakemore AI, Kumari V. How do lipids influence risk of violence, self-harm and suicidality in people with psychosis? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2022 May;56(5):451-488. n Update. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012 Dec 23;2012:387901. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/387901. [CrossRef]

- Buydens-Branchey L, Branchey M, Hudson J, Fergeson P. Low HDL cholesterol, aggression and altered central serotonergic activity. Psychiatry Res. 2000 Mar 6;93(2):93-102. [CrossRef]

- Sahebzamani, Frances M. et al.Relationship among low cholesterol levels, depressive symptoms, aggression, hostility, and cynicism. Journal of Clinical Lipidology, Volume 7, Issue 3, 208 – 216.

- Hofhansel L, Weidler C, Votinov M, Clemens B, Raine A, Habel U. Morphology of the criminal brain: Gray matter reductions are linked to antisocial behavior in offenders. Brain Struct Funct. 2020 Sep;225(7):2017-2028. [CrossRef]

- Cristofori I, Zhong W, Mandoske V, Chau A, Krueger F, Strenziok M, Grafman J. Brain Regions Influencing Implicit Violent Attitudes: A Lesion-Mapping Study. J Neurosci. 2016 Mar 2;36(9):2757-68. [CrossRef]

- Pardini DA, Raine A, Erickson K, Loeber R. Lower amygdala volume in men is associated with childhood aggression, early psychopathic traits, and future violence. Biol Psychiatry. 2014 Jan 1;75(1):73-80. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Jiang X, Chang M, Wei S, Tang Y, Wang F. White matter abnormalities of corpus callosum in patients with bipolar disorder and suicidal ideation. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 10;18:20. [CrossRef]

- Naudts K, Hodgins S. Neurobiological correlates of violent behavior among persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006 Jul;32(3):562-72. [CrossRef]

- Yan R, Wei D, Varshneya A, Shan L, Dai B, Asencio HJ 3rd, Gollamudi A, Lin D. The multi-stage plasticity in the aggression circuit underlying the winner effect. Cell. 2024 Oct 9:S0092-8674(24)01088-2. [CrossRef]

- Popescu ER, Semeniuc S, Hritcu LD, Horhogea CE, Spataru MC, Trus C, Dobrin RP, Chirita V, Chirita R. Cortisol and Oxytocin Could Predict Covert Aggression in Some Psychotic Patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021 Jul 27;57(8):760. [CrossRef]

- Pfundmair M, Reinelt A, DeWall CN, Feldmann L. Oxytocin strengthens the link between provocation and aggression among low anxiety people. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018 Jul;93:124-132. [CrossRef]

- DeWall, C. N., Gillath, O., Pressman, S. D., Black, L. L., Bartz, J. A., Moskovitz, J., & Stetler, D. A. (2014). When the Love Hormone Leads to Violence: Oxytocin Increases Intimate Partner Violence Inclinations Among High Trait Aggressive People. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(6), 691-697. [CrossRef]

- Heitmann A.S.B., Zanjani A.A.H., Klenow M.B., Mularski A., Sønder S.L., Lund F.W., Boye T.L., Dias C., Bendix P.M., Simonsen A.C.; et al. Phenothiazines alter plasma membrane properties and sensitize cancer cells to injury by inhibiting annexin-mediated repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297:101012. [CrossRef]

- Voronova, O.; Zhuravkov, S.; Korotkova, E.; Artamonov, A.; Plotnikov, E. Antioxidant Properties of New Phenothiazine Derivatives. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1371. [CrossRef]

- Keynes RG, Karchevskaya A, Riddall D, Griffiths CH, Bellamy TC, Chan AWE, Selwood DL, Garthwaite J. N10 -carbonyl-substituted phenothiazines inhibiting lipid peroxidation and associated nitric oxide consumption powerfully protect brain tissue against oxidative stress. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2019 Sep;94(3):1680-1693. [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi SF, Elmi S, Nylandsted J. Repurposing phenothiazines for cancer therapy: Compromising membrane integrity in cancer cells. Front Oncol. 2023 Nov 23;13:1320621. [CrossRef]

- Amaral L, Viveiros M, Molnar J. Antimicrobial activity of phenothiazines. In Vivo. 2004 Nov-Dec;18(6):725-31.

- Zhang X., Meng F., Lyu W., He J., Wei R., Du Z., Zhang C. Histone lactylation antagonizes senescence and skeletal muscle aging via facilitating gene expression reprogramming. bioRxiv. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wei L., Yang X., Wang J., Wang Z., Wang Q., Ding Y., Yu A. H3K18 lactylation of senescent microglia potentiates brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease through the NFκB signaling pathway. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023;20:208. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu C, Schwartz B. The relationship between nutrition and the immune system. Front Nutr. 2022 Dec 8;9:1082500. [CrossRef]

- Link C.D. Is There a Brain Microbiome? Neurosci. Insights. 2021;16:26331055211018709. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius L., Kell D.B., Pretorius E. Iron Dysregulation and Dormant Microbes as Causative Agents for Impaired Blood Rheology and Pathological Clotting in Alzheimer’s Type Dementia. Front. Neurosci. 2018;12:851. [CrossRef]

- Mahin Ghorbani, Unveiling the Human Brain Virome in Brodmann Area 46: Novel Insights Into Dysbiosis and Its Association With Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia Bulletin Open, Volume 4, Issue 1, January 2023, sgad029. [CrossRef]

- Safe S, Jin UH, Park H, Chapkin RS, Jayaraman A. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR) Ligands as Selective AHR Modulators (SAhRMs). Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Sep 11;21(18):6654. [CrossRef]

- Sharma R. Emerging Interrelationship between the Gut Microbiome and Cellular Senescence in the Context of Aging and Disease: Perspectives and Therapeutic Opportunities. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 2022;14:648–663. [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Marrero, Cristina, and José R. Lemos. 2024. ‘Modulation of Oxytocin Release by Internal Calcium Stores.’ Oxytocin and Social Function. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Torti MF, Giovannoni F, Quintana FJ, García CC. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor as a Modulator of Anti-viral Immunity. Front Immunol. 2021 Mar 5;12:624293. [CrossRef]

- Kueck T, Cassella E, Holler J, Kim B, Bieniasz PD. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and interferon gamma generate antiviral states via transcriptional repression. Elife. 2018 Aug 22;7:e38867. [CrossRef]

- Ren J, Lu Y, Qian Y, Chen B, Wu T, Ji G. Recent progress regarding kaempferol for treating various diseases. Exp Ther Med. 2019 Oct;18(4):2759-2776. [CrossRef]

- Xia QS, Wu F, Wu WB, Dong H, Huang ZY, Xu L, Lu FE, Gong J. Berberine reduces hepatic ceramide levels to improve insulin resistance in HFD-fed mice by inhibiting HIF-2α. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Jun;150:112955. [CrossRef]

- Imran M, Ghorat F, Ul-Haq I, Ur-Rehman H, Aslam F, Heydari M, Shariati MA, Okuskhanova E, Yessimbekov Z, Thiruvengadam M, Hashempur MH, Rebezov M. Lycopene as a Natural Antioxidant Used to Prevent Human Health Disorders. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020 Aug 4;9(8):706. [CrossRef]

- Kim TW. Fisetin, an Anti-Inflammatory Agent, Overcomes Radioresistance by Activating the PERK-ATF4-CHOP Axis in Liver Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 May 22;24(10):9076. [CrossRef]

- Lamming DW. Inhibition of the Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR)-Rapamycin and Beyond. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016 May 2;6(5):a025924. [CrossRef]

- Zamani M, Nikbaf-Shandiz M, Aali Y, Rasaei N, Zarei M, Shiraseb F, Asbaghi O. The effects of acarbose treatment on cardiovascular risk factors in impaired glucose tolerance and diabetic patients: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Front Nutr. 2023 Aug 1;10:1084084. [CrossRef]

- Singh CK, Chhabra G, Ndiaye MA, Garcia-Peterson LM, Mack NJ, Ahmad N. The Role of Sirtuins in Antioxidant and Redox Signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018 Mar 10;28(8):643-661. [CrossRef]

- Janić M, Lunder M, Cerkovnik P, Prosenc Zmrzljak U, Novaković S, Šabovič M. Low-Dose Fluvastatin and Valsartan Rejuvenate the Arterial Wall Through Telomerase Activity Increase in Middle-Aged Men. Rejuvenation Res. 2016 Apr;19(2):115-9. [CrossRef]

- Kuk MU, Kim JW, Lee YS, Cho KA, Park JT, Park SC. Alleviation of Senescence via ATM Inhibition in Accelerated Aging Models. Mol Cells. 2019 Mar 31;42(3):210-217. [CrossRef]

- S. An, S. Cho, J. Kang, S. Lee, H. Kim, D. Min, E. Son, K. Cho, Inhibition of 3-phosphoinositide–dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) can revert cellular senescence in human dermal fibroblasts, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 (49) 31535-31546. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sheitman BB, Knable MB, Jarskog LF, Chakos M, Boyce LH, Early J, Lieberman JA. Secretin for refractory schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004 Feb 1;66(2-3):177-81. PMID: 15061251. [CrossRef]

- Danhof HA, Lee J, Thapa A, Britton RA, Di Rienzi SC. Microbial stimulation of oxytocin release from the intestinal epithelium via secretin signaling. Gut Microbes. 2023 Dec;15(2):2256043. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Zhang, X., Liu, X. et al. Galactooligosaccharides and Limosilactobacillus reuteri synergistically alleviate gut inflammation and barrier dysfunction by enriching Bacteroides acidifaciens for pentadecanoic acid biosynthesis. Nat Commun 15, 9291 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Okubo R, Koga M, Katsumata N, Odamaki T, Matsuyama S, Oka M, Narita H, Hashimoto N, Kusumi I, Xiao J, Matsuoka YJ. Effect of bifidobacterium breve A-1 on anxiety and depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: A proof-of-concept study. J Affect Disord. 2019 Feb 15;245:377-385. [CrossRef]

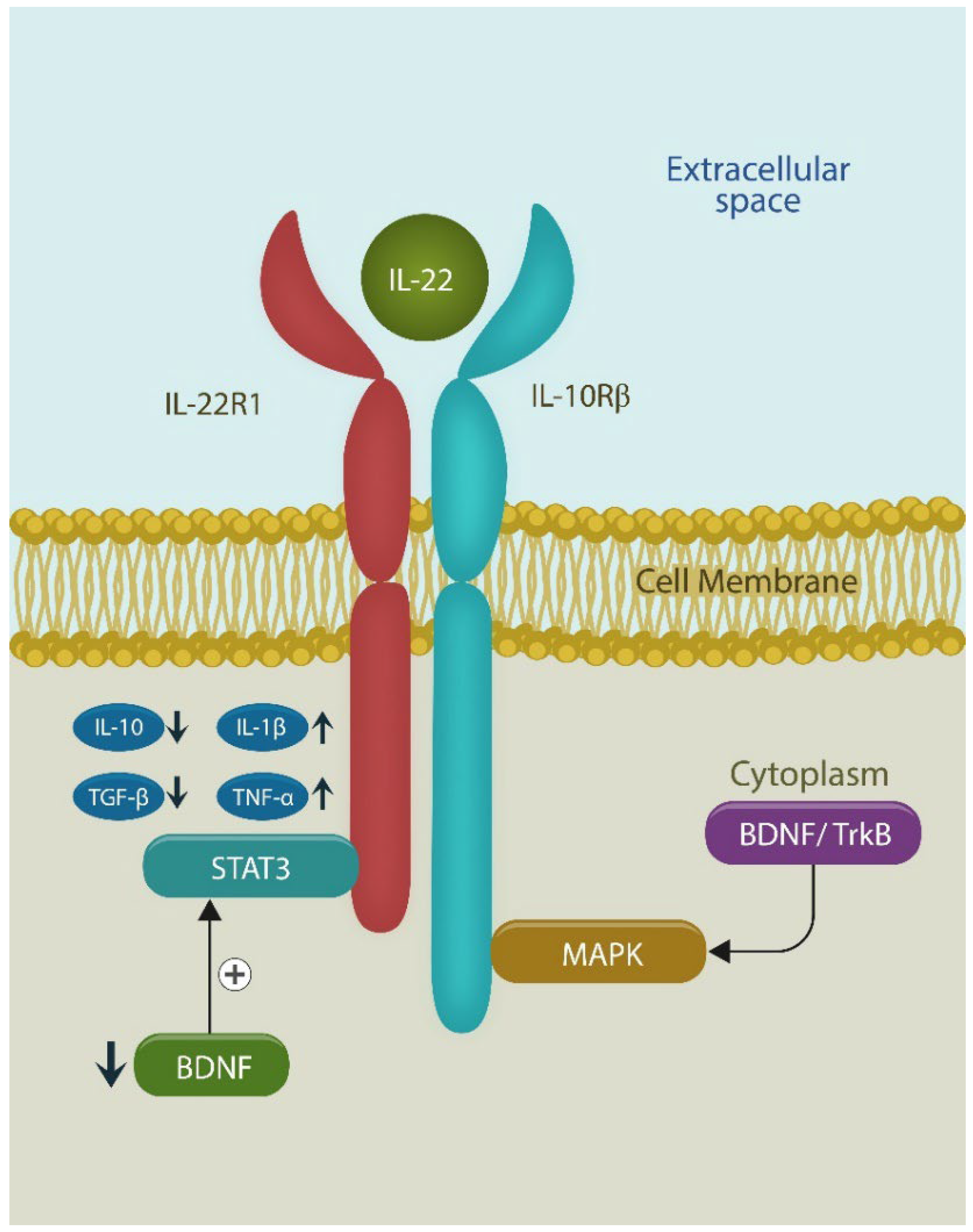

- Sfera, A.; Thomas, K.A.; Anton, J. Cytokines and Madness: A Unifying Hypothesis of Schizophrenia Involving Interleukin-22. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12110. [CrossRef]

- Van Spaendonk H, Ceuleers H, Witters L, Patteet E, Joossens J, Augustyns K, Lambeir AM, De Meester I, De Man JG, De Winter BY. Regulation of intestinal permeability: The role of proteases. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Mar 28;23(12):2106-2123. [CrossRef]

- Paramos-de-Carvalho D, Jacinto A, Saúde L. The right time for senescence. Elife. 2021 Nov 10;10:e72449. [CrossRef]

- 85. Zhang L, Pitcher LE, Prahalad V, Niedernhofer LJ, Robbins PD. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: Senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS J. 2023 Mar;290(5):1362-1383. [CrossRef]

- Yue L, Ren Y, Yue Q, Ding Z, Wang K, Zheng T, Chen G, Chen X, Li M, Fan L. α-Lipoic Acid Targeting PDK1/NRF2 Axis Contributes to the Apoptosis Effect of Lung Cancer Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021 Jun 4;2021:6633419. [CrossRef]

- Rossell SL, Francis PS, Galletly C, Harris A, Siskind D, Berk M, Bozaoglu K, Dark F, Dean O, Liu D, Meyer D, Neill E, Phillipou A, Sarris J, Castle DJ. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in schizophrenia resistant to clozapine: A double blind randomised placebo controlled trial targeting negative symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 15;16(1):320. [CrossRef]

- 89. Sanders LLO, de Souza Menezes CE, Chaves Filho AJM, de Almeida Viana G, Fechine FV, Rodrigues de Queiroz MG, Gonçalvez da Cruz Fonseca S, Mendes Vasconcelos SM, Amaral de Moraes ME, Gama CS, Seybolt S, de Moura Campos E, Macêdo D, Freitas de Lucena D. α-Lipoic Acid as Adjunctive Treatment for Schizophrenia: An Open-Label Trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017 Dec;37(6):697-701. [CrossRef]

- Spellmann I, Rujescu D, Musil R, Meyerwas S, Giegling I, Genius J, Zill P, Dehning S, Cerovecki A, Seemüller F, Schennach R, et al/. Pleckstrin homology domain containing 6 protein (PLEKHA6) polymorphisms are associated with psychopathology and response to treatment in schizophrenic patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014 Jun 3;51:190-5. [CrossRef]

- Feng L, Wong JCM, Mahendran R, Chan ESY, Spencer MD. Intranasal oxytocin for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 20;2017(1): CD010928. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson GL, Ash ME. Membrane Lipid Replacement for chronic illnesses, aging and cancer using oral glycerolphospholipid formulations with fructooligosaccharides to restore phospholipid function in cellular membranes, organelles, cells and tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2017 Sep;1859(9 Pt B):1704-1724. [CrossRef]

- Repetto, Marisa, Jimena Semprine, and Alberto Boveris. 2012. ‘Lipid Peroxidation: Chemical Mechanism, Biological Implications and Analytical Determination’. Lipid Peroxidation. InTech. [CrossRef]

- Tatsuya Sato, Jason Solomon, ShapiroHsiang-Chun, Chang Richard A, Miller Hossein Ardehali (2022) Aging is associated with increased brain iron through cortex-derived hepcidin expression eLife 11:e73456. [CrossRef]

- Lolicato F, Juhola H, Zak A, Postila PA, Saukko A, Rissanen S, Enkavi G, Vattulainen I, Kepczynski M, Róg T. Membrane-Dependent Binding and Entry Mechanism of Dopamine into Its Receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020 Jul 1;11(13):1914-1924. [CrossRef]

- Dichtl S, Demetz E, Haschka D, Tymoszuk P, Petzer V, Nairz M, Seifert M, Hoffmann A, Brigo N, Würzner R, Theurl I, Karlinsey JE, Fang FC, Weiss G. Dopamine Is a Siderophore-Like Iron Chelator That Promotes Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Virulence in Mice. mBio. 2019 Feb 5;10(1):e02624-18. [CrossRef]

- Tao L, Qing Y, Cui Y, Shi D, Liu W, Chen L, Cao Y, Dai Z, Ge X, Zhang L. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization mediated apoptosis involve in perphenazine-induced hepatotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol Lett. 2022 Aug 15;367:76-87. [CrossRef]

- Yacoub A, Park MA, Hanna D, Hong Y, Mitchell C, Pandya AP, Harada H, Powis G, Chen CS, Koumenis C, Grant S, Dent P. OSU-03012 promotes caspase-independent but PERK-, cathepsin B-, BID-, and AIF-dependent killing of transformed cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2006 Aug;70(2):589-603. [CrossRef]

- Varalda M, Antona A, Bettio V, Roy K, Vachamaram A, Yellenki V, Massarotti A, Baldanzi G, Capello D. Psychotropic Drugs Show Anticancer Activity by Disrupting Mitochondrial and Lysosomal Function. Front Oncol. 2020 Oct 19;10:562196. [CrossRef]

- Girgis RR, Lieberman JA. Anti-viral properties of antipsychotic medications in the time of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2021 Jan;295:113626. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Suvannasankha A, Crean CD, White VL, Johnson A, Chen CS, Farag SS. OSU-03012, a novel celecoxib derivative, is cytotoxic to myeloma cells and acts through multiple mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Aug 15;13(16):4750-8. [CrossRef]

- Tsao N, Chang YC, Hsieh SY, Li TC, Chiu CC, Yu HH, Hsu TC, Kuo CF. AR-12 Has a Bactericidal Activity and a Synergistic Effect with Gentamicin against Group A Streptococcus. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Oct 27;22(21):11617. [CrossRef]

- Nehme H, Saulnier P, Ramadan AA, Cassisa V, Guillet C, Eveillard M, Umerska A. Antibacterial activity of antipsychotic agents, their association with lipid nanocapsules and its impact on the properties of the nanocarriers and on antibacterial activity. PLoS ONE. 2018 Jan 3;13(1):e0189950. [CrossRef]

- Girgis RR, Lieberman JA. Anti-viral properties of antipsychotic medications in the time of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2021 Jan;295:113626. [CrossRef]

- Roberts RA, Kim J, Poklepovic A, Roberts JL, Booth L, Dent P. AR12 (OSU-03012) suppresses GRP78 expression and inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020 Dec;182:114227. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Suvannasankha A, Crean CD, White VL, Johnson A, Chen CS, Farag SS. OSU-03012, a novel celecoxib derivative, is cytotoxic to myeloma cells and acts through multiple mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Aug 15;13(16):4750-8. [CrossRef]

| OSU-03012 | Antipsychotic drugs | References |

|---|---|---|

| Lowers ER stress via PERK | Lower ER stress via PERK | 106 |

| Inhibits cathepsins | Inhibits cathepsins | 107; 108 |

| Antineoplastic properties | Antineoplasic properties | 109;110 |

| Antibacterial properties | Antibacterial properties | 111, 112 |

| Antiviral properties | Antiviral properties | 113;114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).