1. Introduction

The history of medicine regulation in Iraq dates back to ancient times [

1]. Medicinal prescriptions were documented in cuneiform writing on clay tablets by specialists in the south of Iraq as early as the 4th millennium BC [

1]. The first state-regulated pharmacies were established in Baghdad during the Golden Islamic Age of the 9th century AD [

2,

3]. In contemporary history, Iraq had the most organised pharmaceutical regulatory affairs system in the region, until the Gulf Wars [

4].

Currently, Iraq is a war-ravaged country with a population exceeding 42 million and is estimated to reach 50 million by 2030 [

5]. Iraq witnessed fundamental changes following the US-led invasion in 2003, and many actors, both domestic and international, participated in the establishment of a new state [

6]. An open economic policy and increased oil revenue led to significant growth in the Iraqi economy [

7,

8]. In 2023, Iraq is considered an upper middle-income country, placed amongst the top 50 global economies, with a total GDP of 254.99 billion US-dollars [

7,

8].

Despite the economic growth and the State’s health strategies after 2003, Iraqi health indicators are still lower than other countries of similar geographic and socioeconomic status [

9]. The healthcare system is highly fragmented and faces many challenges at different operational levels [

4,

10,

11,

12]. A particularly concerning fact is that very little funding, only 4.5% (about 5 billions US-dollar) of the total GDP in 2019 was allocated to healthcare, and despite a quarter of the funds distributed for purchasing medicines and overdue payments, large gaps in the pharmaceutical supply still exist [

10].

The current epidemiological landscape of Iraq is consistent with an upper middle-income country, with the predominant burden of disease originating from non-communicable diseases [

13,

14]. Such diseases of concern include obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cancers [

13,

15]. All these conditions have been increasing since 2003 [

15]. These diseases, along with a high prevalence of smoking and inadequate physical activity, as well as high levels of air pollution, contribute to more fatal conditions such as stroke and ischemic heart disease. The latter are reflected in the epidemiological landscape with these two conditions being the two of the leading causes of death in Iraq [

9,

13,

14,

16,

17]. The effective management of these rampant and prevalent diseases require timely pharmaceutical support to alleviate the physiological complications that may arise, which relies on a structurally sound healthcare system [

16,

17,

18]. As the rates of non-communicable diseases are increasing dramatically, non-action will only result in further healthcare inadequacies [

10,

13,

14]. These are even more concerning due to the young age of Iraq’s population (median age is 20.2 years old) as, in the absence of effective interventions, these issues will only continue exacerbating as the population ages [

5,

16]. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has already demonstrated that an increased burden on the constrained healthcare system can threaten Iraq’s capacity to effectively respond to a health crisis [

19].

Since its establishment in 1920, the Ministry of Health (MoH) has been considered the backbone of the healthcare system. It is represented by a Directorate of Health at each province and prefecture in the State [

20]. The MoH owns all the public healthcare facilities and governs the entire pharmaceutical sector. It also provides primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare services to the population at a subsidised rate [

21]. However, the demand for such services far outweighs its supply, with public healthcare facilities hindered by population growth, dilapidated capabilities still suffering the aftereffects of turmoil, and a lack of healthcare sector investments [

10]. Concerningly, this has led to out-of-pocket expenses accounting for more than half of Iraq’s healthcare expenditure [

7]. This is further exacerbated by lack of any national health financing scheme, and health insurance is only available through a limited number of private corporate insurance programs targeted to the socioeconomically wealthy [

7]. All of which creates issues with healthcare access and equity in Iraq, thereby negatively influencing health outcomes of the population.

The MoH is guided by the National Health Policy with the current iteration from 2013 to 2023, a document published by the Ministry that highlights areas of priority within the health sector [

22]. The overarching goal of the most recent iteration of the policy aims to improve universal healthcare coverage. This can be done through strengthening health governance, maximising available resources, building an effective workforce, ensuring availability of pharmaceutical products, reducing burden of disease, ensuring provision of essential healthcare, improving quality of care, improving health promotion, enhancing mental health, supporting the private healthcare sector, and encouraging community participation [

22]. Although pharmaceutical security is acknowledged in the policy, it must be addressed through the structures and systems within the sector. Additionally, the integrations and interactions that the pharmaceutical aspect of healthcare has on other priorities warrant further consideration and analysis [

22].

On the other hand, the pharmaceutical market of Iraq has seen rapid growth over the last few years, with it being worth approximately 4.6 billion US-dollars in 2020 and on an increasing trend [

23,

24]. It had been estimated that the growth will continue at a rate of 10–15 percent per annum over the period 2018-2022 [

25,

26]. Therefore, the Iraqi pharmaceutical market appears to be an attractive opportunity to invest, not only for local stakeholders but also international enterprises [

26].

This review provides an overview of the structures and processes within the pharmaceutical system in Iraq, its strengths, limitations, and contribution to the current healthcare system. It will serve as a guide for domestic and international stakeholders to capitalise on the opportunity for growth and provide additional considerations for the upcoming iteration of the National Health Policy. Moreover, the information will provide a platform for further research as well as facilitate more informed decision-making which will not only benefit and maximise healthcare efficiency and outcomes, but also strengthen the economy through diversification away from a reliance on the oil industry and increase productivity through maintenance of good health and social stability [

27,

28].

2. Methods

This narrative review article was conducted to identify and map studies’ findings that discussed Iraq's healthcare system and pharmaceutical system. The following search terms were applied in Google, PubMed, and Scopus to locate relevant articles and sources: medicine policies, healthcare system, Iraq, pharmaceutical system, pharmacy education, pharmaceutical industry, medicine regulatory framework, 2003. Digital sources were also retrieved from official websites. Sources were included if they were published within the last 25 years to ensure the research is up to date but still ensure there were sufficient resources, given that it is an understudied field which included, but were not limited to, government and non-government publications both digital and in paper (in English and Arabic language). Eligibility was also restricted to articles and resources that discussed Iraqi’s healthcare system and specifically analysed pharmaceutical system and pharmaceutical education along with pharmaceutical system. Data were scrutinised and critically analysed for details pertaining to the pharmaceutical environment of Iraq. The information was then synthesised into figures illustrating structures and processes within the pharmaceutical industry, and visualising the interactions and relationships between each identified factor.

3. Structure of the Pharmaceutical Sector

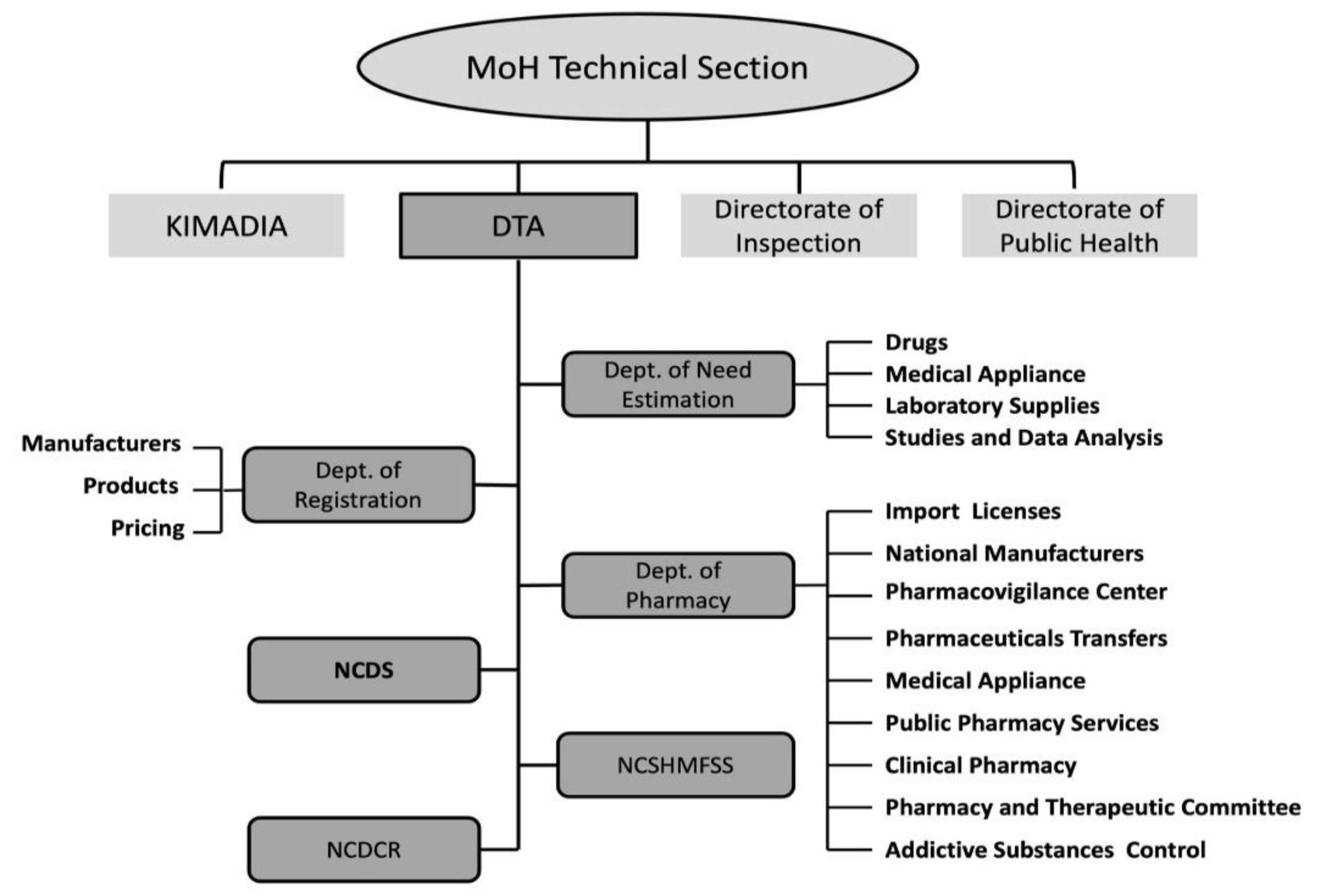

Public Sector Structure

The pharmaceutical sector in Iraq is centrally controlled by the MoH. It is divided into two main segments: public and private [

4,

20]. The Ministry acts through several technical units, including the Directorate of Inspection, the Directorate of Public Health, the State Company for Marketing Drugs and Medical Appliances (KIMADIA), and the Directorate of Technical Affairs (DTA) to administer the entire pharmaceutical regulatory process (

Figure 1) [

20,

29,

30]. KIMADIA is a state-owned enterprise that is part of the MoH that is exclusively responsible for importing, purchasing, storing, and distributing medicines and medical supplies, medical equipment, laboratory materials and medical spare parts, chemical materials and preparation of serums and vaccines, in the public sector [

31,

32]. It operates via a commercial tender procurement system. KIMADIA’s annual purchases was estimated to be more than 600 million US-dollars in 2013 [

25].

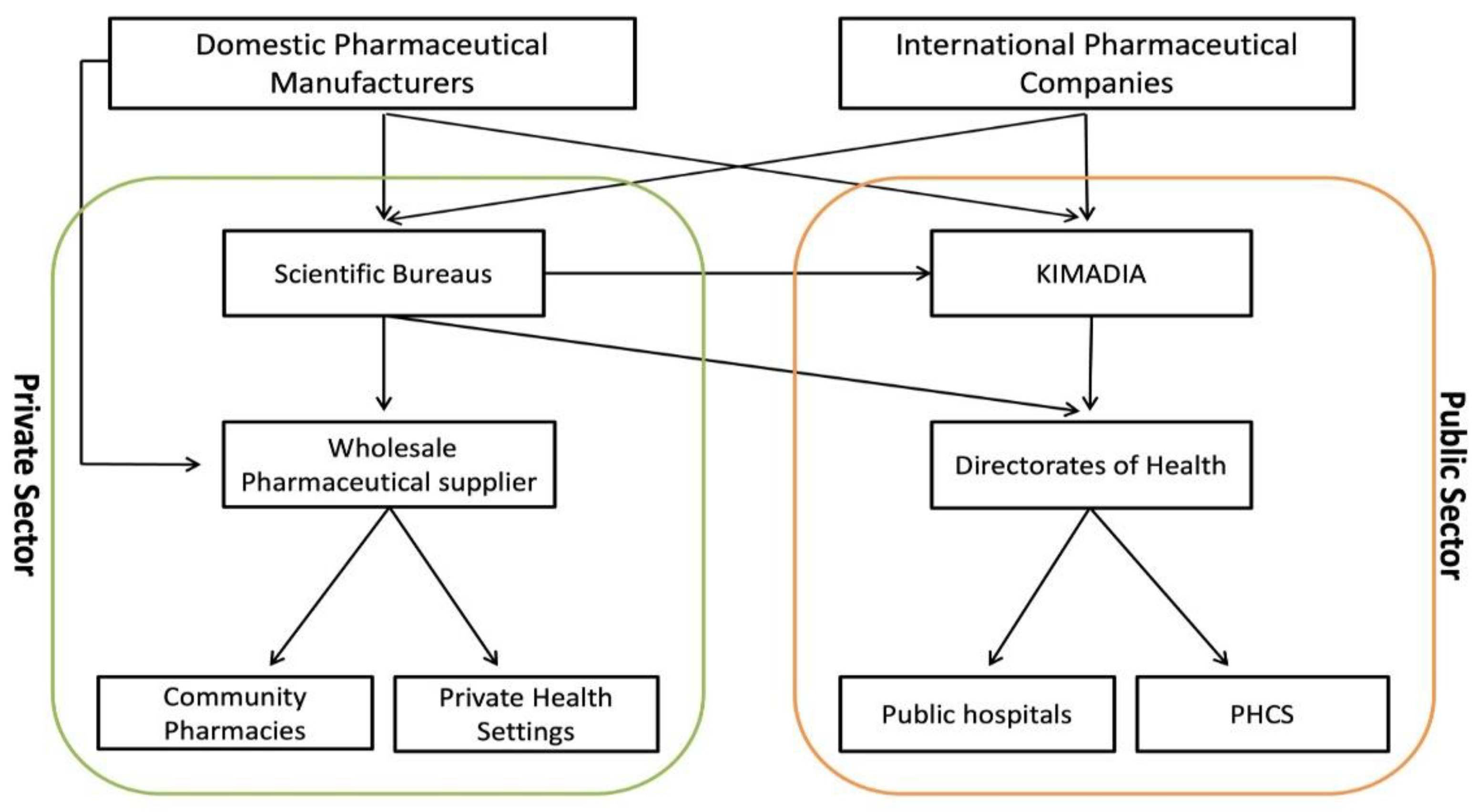

In theory, the MoH procures and supplies public pharmaceutical dispensaries with the entirety of the medicines and medical appliances it requires through KIMADIA [

29,

33]. However, in practice, this is often not the case due to challenges within the pharmaceutical sector as the Directorate of Health can still directly procure medicines and medical appliances from private enterprises within the larger healthcare market (

Figure 2). The annual purchase from these private enterprises has been estimated to be 150–250 million US-dollars [

25].

The DTA is considered the backbone unit for regulating the pharmaceutical and health products in the State, including medicines, vaccines, blood and blood components, biological materials, narcotics and addictive materials, diagnostics, medical devices, herbal/traditional medicines, and food supplements [

29,

31]. It provides licensing establishments, issuance of marketing authorization, regulatory inspection, laboratory testing (quality control and assurance), batch issuance, and pharmacovigilance. DTA includes several technical committees, departments, and centres ran by specialist physicians and pharmacists (

Figure 1) [

29,

31,

34].

Private Sector Structure

The private pharmaceutical sector differs from the public sector in terms of structure, role, size, and procurement model (

Figure 2) [

4,

20]. It encompasses three main entities, which differ in role and size (scientific bureaus, wholesale pharmaceutical suppliers and community pharmacies), that are responsible for distribution of medicines and medical appliances in the private market (

Figure 2) [

25,

29,

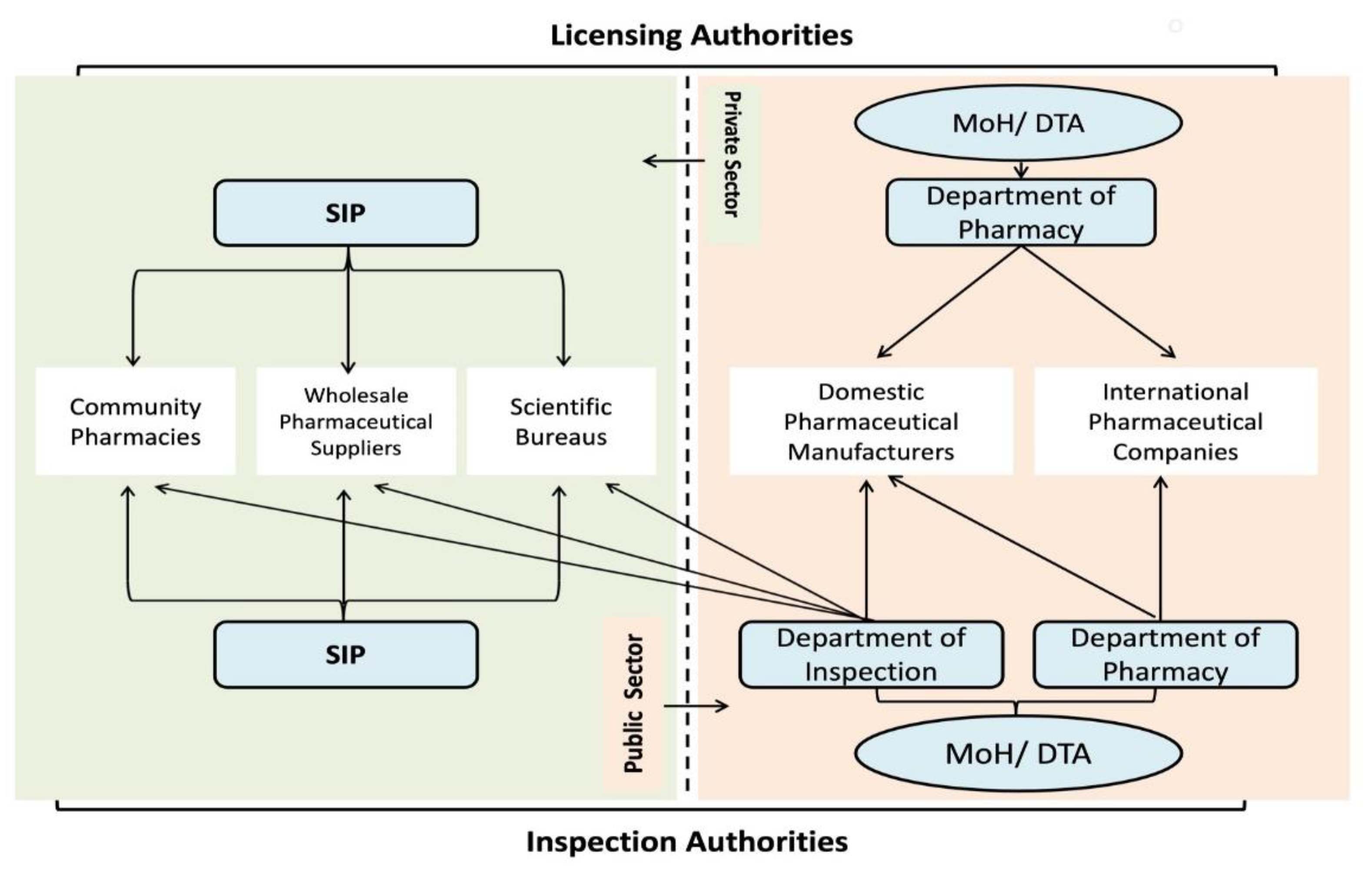

32]. The Syndicate of Iraqi Pharmacists (SIP) is authorised to set the rules and regulations for licensure and inspection of private distributors [

29,

35]. Although MoH, through the Inspection Department/DTA, is responsible for monitoring the private sector (

Figure 3).

Scientific bureaus are private enterprises registered with the SIP that are responsible for promotion and trading of pharmaceuticals across the State and are often local representatives for foreign pharmaceutical companies. It directly procures the pharmaceutical products from domestic and international manufacturers and sells to public (e.g., KIMADIA, Directorates of Health, public hospitals) or wholesale pharmaceutical suppliers, and even sometimes through ‘irregular’ pathways to community pharmacies (

Figure 2) [

29,

36]. Although it is not imperative to have a local agent or representative for a foreign company to participate in KIMADIA tenders, KIMADIA favours the companies with local representatives who work under a scientific bureau [

33,

36]. The customer portfolio of the scientific bureaus can be public or private (

Figure 2) [

37].

Wholesale pharmaceutical suppliers are private enterprises that procures mainly from scientific bureaus or domestic pharmaceutical manufacturers, and directly sells to private dispensaries (community pharmacies, private healthcare facilities) [

25,

29]. However, wholesale pharmaceutical suppliers can also supply public hospitals in certain situations [

25,

29]. Any private pharmaceutical distributors must be licensed by relevant regulations and laws for practicing in the State.

As the community pharmacy market is not dominated by specific players and no pharmacy chains exist in Iraq, such pharmacies are private enterprises of the practicing pharmacist who are supplied by the wholesale pharmaceutical suppliers, and dispensing and compounding the medicine directly to patients [

29]. In 2023, the ratio of community pharmacies per individual was 1:2950, unevenly distributed, and mainly found in the larger cities [

35]. However, between 2011 and 2023, the number of private distributors has increased nearly three-fold for scientific bureaus (296 to 710) and community pharmacies (5336 to 15424), whilst wholesale pharmaceutical suppliers increased 46% (311 to 454) [

29,

35,

38,

39,

40].

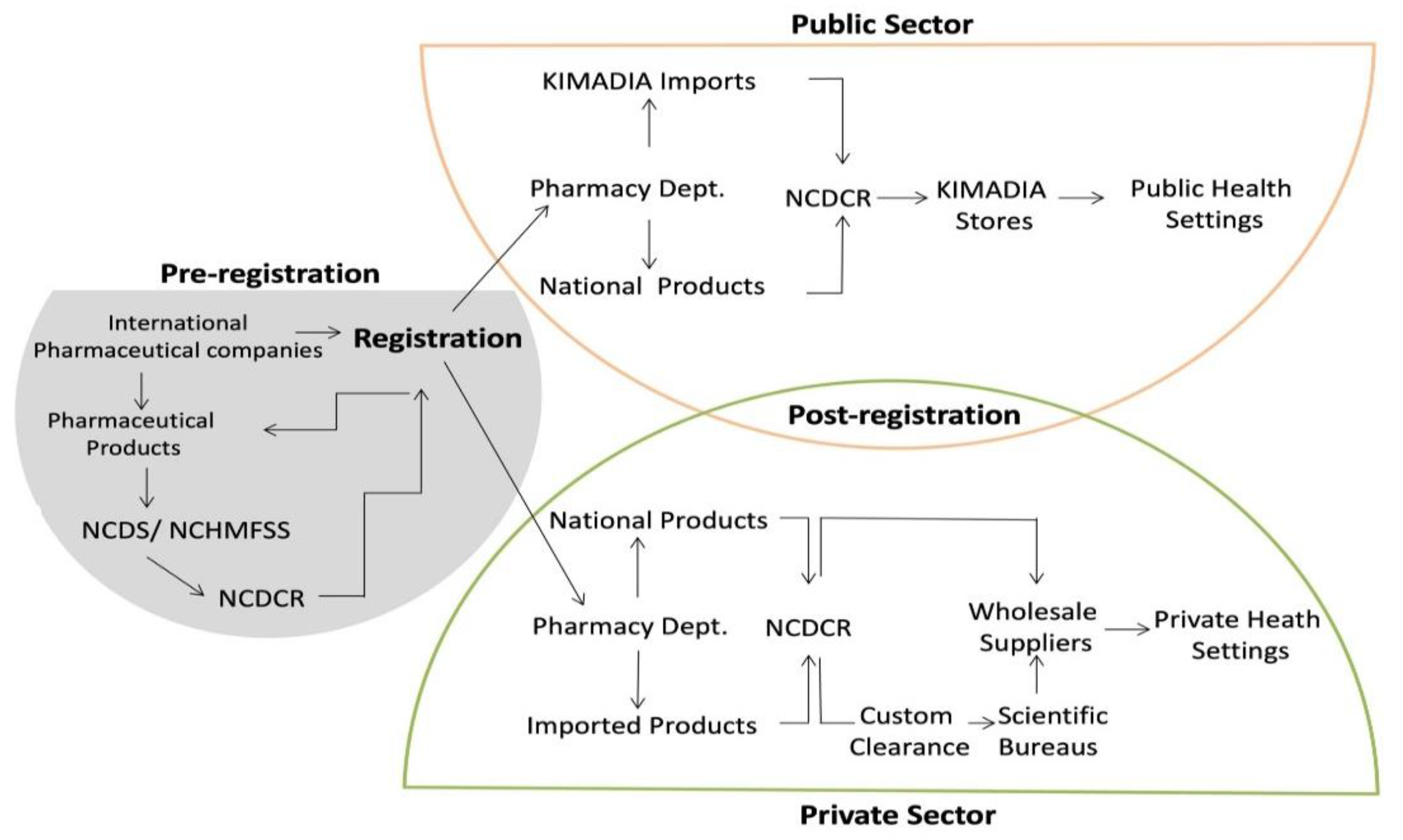

4. Processes Within the Pharmaceutical Sector

4.1. Medicine Selection and Listing

The National Committee for Drug Selection is responsible for approving and listing new medicines and vaccines in the Essential Drug List (EDL) and Comprehensive Drug List (CDL), of which there are currently 5098 registered medicines and 1014 registered supplements [

41,

42].

The EDL includes medicines and vaccines used in any public healthcare setting [

41]. It is sub-classified into three volumes, numbered in order of priority for availability and procurement policies. Volume I includes the most cost-effective medicines and products [

41]. The MoH, through KIMADIA, is exclusively responsible for securing these medicines in the public sector [

33,

41]. In contrast, volumes II and III can be procured by health facilities through negotiation on the market according to their own demands [

41]. New expensive medicines are reviewed by the National Committee for Drug Selection in collaboration with the Department of Need Estimation after conducting socioeconomic studies for their suitability in the market [

41]. The EDL includes 1105 items, half of which are listed under Volume I; only 60% of those medicines were provided by KIMADIA [

37,

42]. This lack of public supply has been attributed to the long bureaucratic system along with a lack of inter-departmental communication within the government that has allowed the private sector to outcompete KIMADIA in terms of procurement, which has been exacerbated by a lack of funding [

43].

4.1.1. Medicine Approval and Listing

The DTA is responsible for the regulation of medicine and pharmaceutical product licensing in the public and private sectors (

Figure 3) [

42]. The licensing process includes a product review by seven technical committees (

Figure 3). DTA takes into consideration the decisions of foreign regulatory agencies when certifying medicines. A Certificate of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and a Certificate of Pharmaceutical Product (CPP) from at least one of the approved foreign regulatory agencies are essential requirements by DTA for international producers [

37]. For local manufacturers, the DTA does not require an additional foreign certification but rather it scrutinises the medicine quality and reliability by carrying out on-site inspections (

Figure 3) [

42].

In an attempt to mitigate shortages in medicines, a fast-track registration scheme has been implemented by DTA [

42]. This scheme allows any pharmaceutical product that has a certification from at least one of the accredited international foreign regulatory agencies to be granted temporary registration and importing license for one month after application [

37,

42]. This scheme was successful in significantly increasing the number of registered medicines and vaccines available within Iraq [

37].

4.1.2. Medicine Pricing

In the public sector, DTA is responsible for determining the price of medicines. It generates the prices based on the brand and the geographical location of the manufacturers. KIMADIA then has the authority to independently procure medicines on the open market, subject to the requirements of the public system.

In the private sector, the government does not intervene in the market to ensure reasonable pricing. However, the MoH, in collaboration with the SIP, encourages compliance with the prices recommended by DTA [

44]. Nevertheless, MoH reported a high percentage of medicines in the private market are out of the SIP pricing system (only 20% of the distributed products in the private market met the standards of the pricing system) [

10]. The lack of price compliance can be attributed to monopolistic and non-competitive oligopolistic behaviours in the private sector which has seen certain enterprises gain majority control over the supply and distribution of certain medicines [

10,

43]. These behaviours were facilitated by outcompeting the public sector in procurement [

10,

43]. Thus, without enforceable government intervention, the market environment has made private distribution enterprises price-setters, to the detriment of healthcare equity and access. Moreover, a large number of unregistered and substandard/falsified (S/F) pharmaceutical products are available through the private market, due to poor control over points-of-entry into the State [

45].

4.1.3. Quality Assurance

DTA, through the National Centre for Drug Control & Research, tests all imported and nationally produced pharmaceutical products for quality assurance (

Figure 1). It follows the US, UK, and European pharmacopoeia requirements for compendial products and the manufacturer’s validated methods for non-compendial products. While there is no protocol for routine testing of pharmaceutical products in the private sector, the National Centre for Drug Control and Research is entitled to test any product that raises suspicions. Furthermore, products with a valid registration by an accredited foreign regulatory agencies are exempt from quality testing [

37,

43].

4.1.4. Pharmacovigilance

All adverse reactions from medicines, biopharmaceuticals, vaccines, supplements, and herbal products are monitored by the National Pharmacovigilance Centre. The Centre also monitors and reports on any S/F medicines found in the public and private sectors. Pharmaceutical companies and scientific bureaus are obliged by a law to monitor and report any existing S/F medicines to the National Pharmacovigilance Centre. Accordingly, information are disseminated via the SIP and Directorate of Inspections channels, and the Directorate of Inspection has the authority to withdraw and confiscate any S/F products [

44]. In 2013, the MoH joined the Global Surveillance and Monitoring System, which is a global rapid warning system for S/F medicines [

46].

5. Challenges in the Pharmaceutical Sector

5.1. Medicine Availability

It is evident that the MoH, through KIMADIA, is facing a number of challenges in providing sufficient medications and pharmaceutical products to fulfil public sector demand [

10,

47]. In 2018 and 2019, 50% and 40% of essential medicines were missing respectively. This was mainly attributed to insufficient financial allocation and long processes to acquire medications [

10].

5.2. Ministry of Health Capabilities

Additionally, the MoH has limited expertise in health economics, epidemiology, statistics, and public policy, which has resulted in suboptimal populational health outcomes [

10]. It has been reported that the links between the MoH economic policies and national health priorities are poor in Iraq, which again highlights the lack of inter-departmental cooperation that is required to deal with modern systemic healthcare issues [

48]. Both factors lead to delayed response times to health situations which further exacerbates issues of medicine availability as the private sector capitalises on the delay to the detriment of health equity and populational health outcomes [

10,

29].

5.3. Rational Use of Medicines

MoH, through the Department of Pharmacy/DTA, started a national program to enhance and observe the rational use of medicines in public healthcare facilities in 2008. Nonetheless, MoH has reported no adherence to the guidelines for prescribing and dispensing medicines and rational use of antibiotics and biological medicines (diabetes, autoimmune, chronic diseases, cancer, and rare diseases), a fact that negatively affects medicine availability and therapeutic outcomes in both the public and private sectors. Furthermore, the private sector remains largely uncontrolled in this regard [

10].

Of note, there is no consistent awareness among physicians regarding generic and biosimilar medicines [

49]. No specific formulary or guidelines exist from the relevant regulatory authorities about such medicines in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy. Additionally, there has been poor awareness of prescribing generic medicine and cost-effective prescribing due to a notable absence in the medical curricula [

47]. A qualitative study has suggested that there is a need for more education and further reassurance about the quality, safety, and efficacy of generic medicines in Iraq [

47]. The study also showed some physicians object to the involvement of pharmacists in therapeutic decisions, specifically with brand-substitution of medicines [

47]. This was attributed to a lack of trust between physicians and pharmacists, specifically regarding the evaluation of therapeutic efficacy [

47].

.WHO has suggested that Iraq needs to implement and enforce rational use of medicines to achieve its stated healthcare goals [

21]. Clinical pharmacists aim to minimise the medications prescribed in error and review the prescribed medicines for any inappropriately prescribed medicines [

50]. Thus, development of efficient processes to optimise prescriptions should be an urgent priority.

5.4. Health Information Systems

Reliable and up-to-date information are essential for key decisions in any healthcare setting [

51]. The current health information system in Iraq largely relies on paper documentation, and no electronic health information system exists [

43]. This has resulted in a lack of information integration across healthcare facilities and government departments which ultimately is detrimental to care continuity [

43]. WHO has reported that the lack of an integrated information system that brings data from across different information subsystems in Iraq is considered one of the foremost healthcare system challenges in the state [

21]. MoH highlighted a shortage in health economists, epidemiologists and statistics experts [

10] that impacted the MoH capacity for analysis, monitoring, dissemination, and rapid response [

4].

Moreover, the lack of modernization in record-keeping extends to the prescription scheme as well. This may be further exacerbated by the private sector being largely out of the public health information systems [

4]. The community pharmacy in Iraq has been described as being like the Swedish system during 1960s where all dispensed medicines to patients occurred manually, without computers, or electronic prescriptions [

52]. Therefore, it is questionable how the pharmacists in modern Iraq remain vigilant against medicine misappropriation.

Although this subject is beyond the scope of the article, the health information system should adopt an efficient national electronic information system. An integrated health information system is important to build resilience beyond the pharmaceutical sector and support the healthcare sector as a whole in terms of management and dealing with problems in a timely manner but also to help in the development of policies, to encourage cooperation from international partners, and to support the development of a healthcare finance system and social insurance.

Furthermore, the private pharmaceutical sector lacks reliable data sources for both health and economic information [

25]. Near total absence of electronic point-of-sale systems has made the collection and processing of sales information extremely difficult [

25]. A major point of contention for many international pharmaceutical companies to up-scale their activities in Iraq as no dependable market statistics are readily available [

25]. To enhance international pharmaceutical companies’ commitment and participation in the market, it is essential to adopt a reliable data system for sales through regular distributor audits, which will be a crucial component in creating the necessary transparency of private market in the State [

25]. Inaccessible data and information, poor documentation, and a lack of access to available knowledge impede the delivery of high-quality health care services in Iraq by limiting capabilities to readily react and adjust to changes in pharmaceutical demand [

20,

53,

54].

Additionally, Iraq lacks an active national health research system which has further increased the vulnerability of the healthcare system [

20]. Although pharmaceutical research and clinical studies are limited in Iraq, in 2014, the MoH established the

Iraqi New Medical Journal, a peer-reviewed official medical journal that has been included in multiple indexing systems, to promote this area [

20,

55]. In addition, many Iraqi universities have their own medical and scientific journals supporting research [

4]. Therefore, the fact that both universities and the MoH can construct active partnerships in targeting and pursuing areas of importance, identifying areas of poor quality and proposing methods to address these deficiencies could be a first step. Iraq could learn much more from international health publications but could also contribute more to the growing global literature.

5.5. Domestic Medicine Production and Supply

Despite many pharmaceutical companies being situated in Iraq, multiple articles have reported that the domestic pharmaceutical industry has been in decline and has been largely neglected by policy makers [

4,

56,

57]. The State Company for Drugs Industry & Medical Appliances (SDI) is one of the largest pharmaceutical manufacturers both domestically and regionally [

57]. SDI was established in the 1960s and is currently operated by the Ministry of Industry [

48]. After the turmoil faced by Iraq in the early 2000s, the company recommenced operations and was granted approval by the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) in 2008 and 2013 and it is currently striving to get additional ISO certifications [

58]. SDI has several accredited factories across the State that produce over 350 different brand-new and generic medicines meeting international standards [

57]. Although SDI’s share of market production was more than 30% before Gulf War II, in 2021, it was only producing 16% of domestic market needs, the rest of the market was mainly shared with the public sector [

12,

58]. However, it must be acknowledged that SDI has taken action to increase production [

58].

At the same time, Iraq tries to expand and modernise the domestic pharmaceutical industry, the State is also trying to move away from the centralised state-based regime towards a de-centralised regime, giving more of a role to the private sector [

10,

43]. In this regard, various international pharmaceutical companies are marketing and trading products in the State [

10,

29]. At the end of 2020, there were 23 domestic pharmaceutical manufacturers (two public and 21 private) which accounted for 47.8% of the total volume of the public sector [

30,

59]. Although they produce medicines, they are neither producing active pharmaceutical ingredients nor biopharmaceuticals or WHO prequalified products [

37,

59]. MoH licenses and inspects the national manufacturers through the Pharmacy Department/DTA and Directorate of Inspection (

Figure 4).

Domestic medicines are the most demanded and trusted among Iraqi population due to their technical and scientific standards and their good medicinal efficiency in comparison to some imported medicines [

60]. The demand can also be attributed to the prices and risk of S/F being exceptionally low for domestically manufactured medicines compared to imported medicines [

29,

30,

58,

60]. In an effort to cope with the pandemic health crises of COVID-19, the domestic pharmaceutical producers attempted to scale up and expand their portfolio with regard to some COVID-19 medicines and consumables [

19]. However, it was considered insufficient in reaction speed and quantity, which meant the State still depended largely on imports [

19].

On the other hand, a cross-sectional study has reported some challenges of the domestic pharmaceutical industry, including: a) lengthy bureaucratic processes to obtain an importing license for materials, b) delays in payment especially in the governmental sector (KIMADIA), c) barriers in importing active ingredients, and d) the negative role of physicians and pharmacists toward promoting the domestic pharmaceutical products [

59]. In addition, the scarcity of studies for bioequivalence conducted each year negatively impacts the domestic industry’s ability to produce more medicines [

10,

29]. Furthermore, adopted policies regarding the temporary registration (fast-track medicine registration) of imported medicines that provided tremendous business opportunities for foreign companies have been at the expense of domestic products [

36]. The establishment of an advance pharmaceutical industry has been identified to have a positive effect on health outcomes in Iraq as well as to meet the Sustainable Development Goals [

61]. Nevertheless, it has been reported that the Iraqi pharmaceutical industry was significantly underregulated after 2003 [

4,

21,

62].

Eventually, the pharmaceutical industry needs to regain the lost momentum and upgrade its contribution to the domestic market. Particularly, the revenues of such industry are high compared to other industrial branches that participate in boosting the state’s economy [

30]. The existing policies and conditions of the domestic pharmaceutical industry seem to be stagnant and sluggish [

30]. By taking advantage of investment policies and regulations, it has been suggested that there are opportunities to invest in the establishment of complete projects for the pharmaceutical industry, increase investment in domestic pharmaceutical capital through improving the quality and quantity of factories, introduce new manufacturing technologies, and increase international cooperation in the industry [

30].

5.6. Education and Training of Pharmacists

The number of registered pharmacists by the SIP has significantly increased since 2003 [

29,

35]. In May 2012, there were only 11,347 SIP-registered pharmacists in Iraq 29 while in October 2020, there were 24,282 [

35]. The increase is attributed to a steady increase in the number of pharmacy schools and frequently modified admission policies by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research [

31]. Currently, there are 60 (17 public and 43 private) schools teaching pharmacy programs in Iraq, but no one awards a bachelor Pharma D program (Supplementary Table 1) [

63].

There is a need to upgrade the entire pharmacy curriculum to direct the pharmacy profession towards the more responsible and effective provision of direct patient care in Iraq [

64]

.

At the same time, the SIP expressed concerns about the Ministry of Higher Education’s policies for new pharmaceutical programs as well as the progressive increase in the number of graduated pharmacists under the limited MoH capacity for further training [

24,

65]. Graduate opportunities have been limited in practicing scope within the public sector due to the increase in graduate supply which is at the detriment of professional competency [

65]. Therefore, expanding post-graduate training and providing clear pathways to the domestic pharmaceutical industry and private sector are warranted to maintain labour demands and prevent human capital flight.

5.7. Oversight in the Private Sector

MoH has reported that the situation in the private pharmaceutical market is ‘out of control’ as 60–70% of products in community pharmacies and wholesale pharmaceutical suppliers do not meet the requirements of circulation, either being: not registered or not subjected to pricing and inspection system (many medicines do not apply the SIP stickers), less than 20% of distributors adhere to the pricing system in the private market, irregular practicing distributors, many non-specialists supply medicines by non-regular pathways, or presence of the S/F [

10,

45]. These irregularities were attributed to weak inspection and control at the borders, weak measures of monitoring and enforcement in the private health sector, complex procedures adopted by the MoH regarding the registration of products and companies and granting import licenses under a sharp shortage with growing demand in the State [

10,

45]. Furthermore, medicinal promotion practices by foreign pharmaceutical companies are largely irregular in the State and need more oversight to prevent any wrongdoing [

29].

Unlike international trends, the private sector has a long distribution chain which increases prices and compromises populational health by increasing barriers to accessing healthcare services, particularly for the most vulnerable. The issue of equity is further exacerbated by a reliance on regressive markups in private pharmaceutical distributors which is uncommon in developed countries [

66]. Furthermore, the lack of policies and education for using cost-effective therapies also contributes to the increase in out-of-pocket costs [

47].

Consequently, the long-term deterioration of public healthcare services and lack of medicinal products led to a massive issue in terms of the population’s trust in their public healthcare system [

67]. This lack of trust has been capitalised by the private sector for profits in Iraq during the last decades [

29]. Thus, people rely, to a high extent, on the private sector for treatment and providing medicines which are at a high cost and may exceed their financial capabilities since there is no subsidy program for the patients who are dispensing their medications from the private market [

10,

11,

68,

69]. WHO has reported more than 70% of out-of-pocket individual payments on health in Iraq, whereas the recommended percentage should not exceed 30% to avoid poverty and to ensure financial protection, and health equity [

7,

10]. Limited public healthcare services remain an important source of healthcare, particularly for people who are poor or unemployed which accounts for more than 20% of the population [

70,

71].

6. Recommendations

Despite its importance in healthcare system reform, Iraqi pharmaceutical sector has shown limited advances under current and historic health policies since 2003 [

45]. Although the modest advances still resulted in positive impacts on health system vulnerabilities, the sector is not up to the norms and standards of a modern pharmaceutical sector [

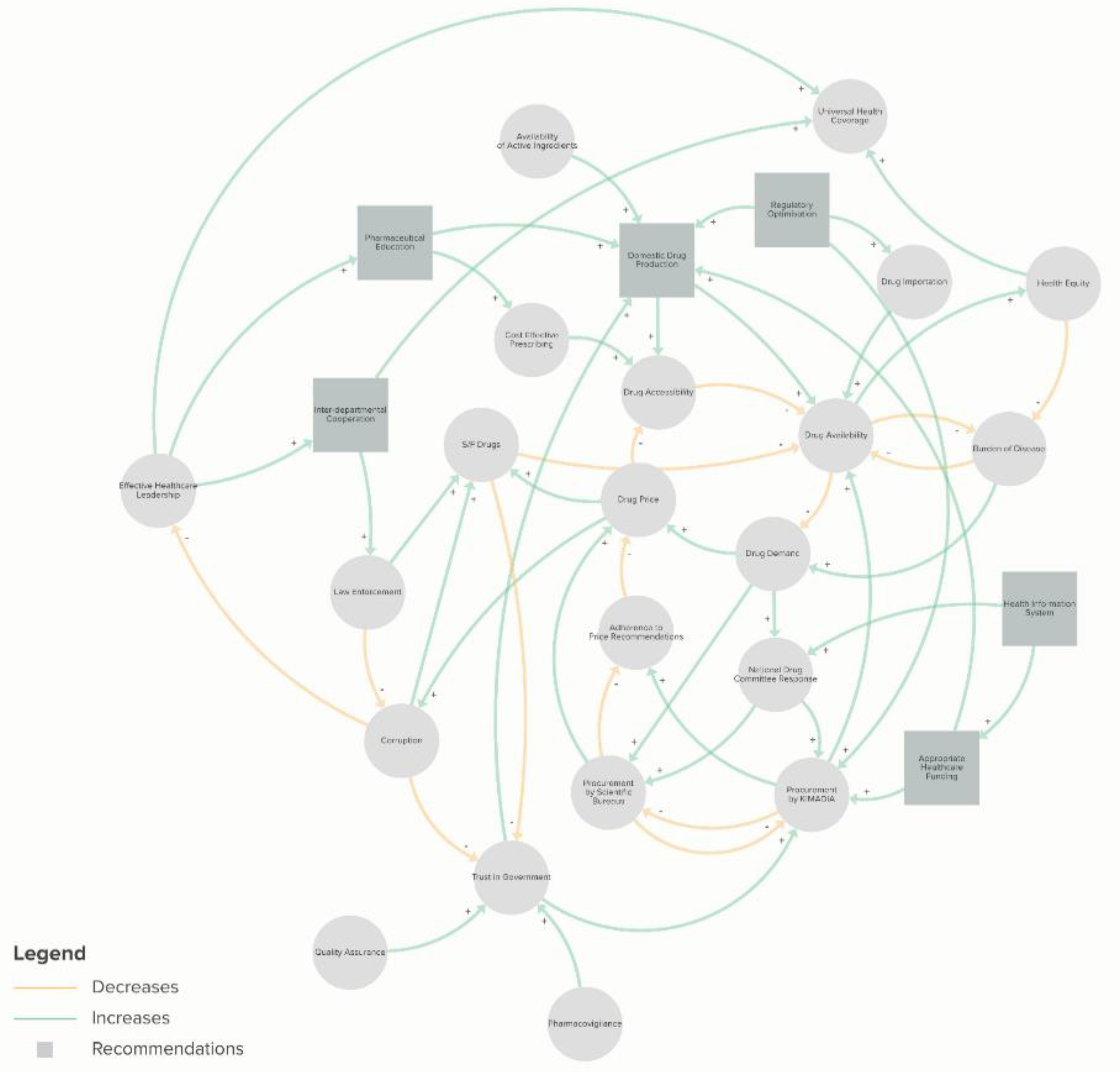

29]. As the pharmaceutical sector suffers from systematic challenges and external constraints, no single solution would alleviate all issues, but a range of multidimensional initiatives is required to holistically address these concerns (

Figure 5). Furthermore, the modernization of the pharmaceutical sector will not only help in the reform of the healthcare sector, but it will also help in growing the State’s economy and legitimacy [

27].

Based on the most up-to-date review of the pharmaceutical sector in Iraq, the authors raise the following recommendations and considerations:

I) Healthcare system including the pharmaceutical sector urgently needs to be prioritised through an increase in funding to fill the gaps in medicine availability and quality of care. This will also alleviate the financial burden on individuals which would improve health equity, social stability, and access, and thereby also improve universal health coverage in a meaningful manner [

72]. In parallel, it is imperative to invest further in understanding the unique health economic landscape of Iraq and scrutinise the management of available financial resources to cover the scarcity of medicines and the lack of availability of most essential and life-saving medicines to reduce the reliance on grey market and S/F medicines;

II) Since the regulatory frameworks of medicines and other pharmaceutical products are complex, lengthy and lack independent regulators, it is important to streamline the process. An adaptive and efficient system would require: a) a more flexible and efficient framework to enhance the registration process and marketing authorization to facilitate timely responses to changes in epidemiological conditions; b) implementation of a fast and practical mechanism for both registration and issuance of import licenses and adoption of laboratory examination certificates; c) prevention of temporary import approvals for non-renewable approved medicines in order to remove the obstacles to the regular import of approved medicines; d) adoption of a policy of supply and purchase tailored to medicines and health supplies to keep pace with the market of modern pharmaceuticals;

III) Increased oversight and regulation in the private sector and enhancement of the government’s monitoring and inspection at points of entry to prevent import of S/F medicines is required. This must be done in conjunction with fighting the related corruption to improve health outcomes and trust in the healthcare sector. In addition, improved interdepartmental cooperation on matters of health to strengthen regulatory policies that have suffered due to disintegration across different departments and ministries should also be prioritised;

IV) Support for the domestic pharmaceutical industry through capital investment and regulatory affairs to facilitate the smooth importation of active ingredients. In parallel, promotion of domestic pharmaceutical products by encouraging both public and private healthcare providers to prioritise locally produced medicines, especially for medicines granted temporary import licenses should also be considered. The capacity of bioequivalence study centres should also be increased to perform more than five studies annually to facilitate an increase in domestic production;

V) Adopt a universal and integrated information system to encompass both public and private sectors to reflect the values of timeliness and completeness of reporting data. This would facilitate regulatory bodies in monitoring medicine demands as well as support public health surveillance efforts and continuity of care [

51]. Such actions will also enhance the transparency of healthcare providers and assist in scientific research; and

VI) Update pharmacy teaching curricula and training to reflect modern market needs in both academia and practice. This will allow graduates to have a more modern appreciation of holistic healthcare. Educational initiatives should not only focus on improving quality of graduates but also consist of improving access to such training and certification. This would allow for better supply and improved quality of practitioners in pharmaceutical settings and further improve health outcomes and trust in the healthcare system. Additionally, leadership at these institutions must be appointed based on merit to ensure the quality and consistency of the training and accreditation provided [

43].

7. Study Limitations

This review lacks reliable quantitative and qualitative data, thus making it more exploratory in nature and hence limited in its generalizability. Furthermore, the synthesis lacked specific analysis of the pharmaceutical sector in Kurdistan province which has autonomy in healthcare settings in Iraq since 1993, although the region does share the same structure, regulations, supply, and distribution models as the rest of Iraq.

8. Conclusions

Despite the advances, reformation of the pharmaceutical sector in Iraq is essential to improve healthcare system functionality and keep up the current challenges and global advances. Enhancement of the pharmaceutical sector will improve health indices and equity, facilitate better medicinal procurement and management, and ensure the health system can adapt and evolve with changes associated with a young upper middle-income country. All in all, the recommendations should be urgently considered by decision makers to improve universal health coverage and to contribute to multiple goals stated in the National Health Policy (

Figure 5). While the need for healthcare reform in Iraq remains an urgent priority, the value of quality qualitative and quantitative research to inform specific determinants and solutions in the Iraqi pharmaceutical sector must not be overlooked.

Author Contributions

AWA: conceived and designed the study, AWA: wrote the main draft of the manuscript and performed the structure, analysis and figures. AWA, WA, R-MD: critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Syndicate of Iraqi Pharmacists. (2024). Syndicate of Iraqi Pharmacist. [online] Available at: https://iraqipharm.org/ [Accessed 10 Mar. 2024].

- Ahmed, K.K., Al-Jumaili, A.A., Mutlak, S.H. and Hadi, M.K. (2020). Determinants of national drug products acceptance across patients, pharmacists, and manufacturers: A mixed method study. Journal of Generic Medicines: The Business Journal for the Generic Medicines Sector, 17(3), pp.139–53. [CrossRef]

- Al Hasnawi, S.M., Al khuzaie, A. and Al Mosawi, A.J. (2009). Iraq health care system: An overview . The New Iraqi Journal of Medicine, 5(3), pp.5–13.

- Al Hilfi, T.K., Lafta, R. and Burnham, G. (2013). Health services in Iraq. The Lancet, 381(9870), pp.939–948. [CrossRef]

- Al Humadi, A. (2019). Challenges of Iraq Pharmaceutical Market Post-2003. Pharmaceutical Drug Regulatory Affairs Journal, 2(2). [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazal, S.K. (2003). The Valuable Contributions of Al-Razi (Rhazes) in the History of Pharmacy during the Middle Ages. International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine, 2(4), pp.9–11.

- Al-Hiti, M. (2019). Iraqi Pharmaceutical Industry Obstacles and Solutions. Athens, Greece.: 4th Iraqi-European Business & Investment Forum.

- Al-Jumaili, A.A., Hussain, S.A. and Sorofman, B. (2013). Pharmacy in Iraq: History, current status, and future directions. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 70(4), pp.368–372. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jumaili, A.A., Sami, S.G. and Al-Rekabi, M.D. (2021). The Preparedness of Public Healthcare Settings and Providers to Face the COVID-19 Pandemic. Latin American Journal of Pharmacy, 40(special issue), pp.15–22.

- Al-Jumaili, A.A., Younus, M.M., Kannan, Y.J.A., Nooruldeen, Z.E. and Al-Nuseirat, A. (2021). Pharmaceutical regulations in Iraq: from medicine approval to postmarketing. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 27(10), pp.1007–1015. [CrossRef]

- AL-JUMAILI, A.A.A., Jabri, A.M., Al-Rekabi, M.D., Abbood, S.K. and Hussein, A.H. (2016). Physician Acceptance of Pharmacist Recommendations about Medication Prescribing Errors in Iraqi Hospitals. Innovations in Pharmacy, 7(3). [CrossRef]

- Al-Kinani, K.K., Ibrahim, M.J., Al-Zubaidi, R.F., Younus, M.M., Ramadhan, S.H., Kadhim, H.J. and Challand, R. (2020). Iraqi regulatory authority current system and experience with biosimilars. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 117, p.104768. [CrossRef]

- Al-lela, O.Q.B., BaderAldeen, S.K., Elkalmi, R.M. and Jawad Awadh, A.I. (2012). Pharmacy Education in Iraq. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 76(9), p.183. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mosawi, A. (2020). Iraq healthcare system: An update. Lupine Online Journal of Medical Sciences, [online] 4(2), pp.404–11.

- Anmar Al-Taie (2020). Insights into Clinical Pharmacy Program in Iraq: Current Trends and Upgrading Plans. Jordan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 13(3), pp.265–71.

- Boehme, A.K., Esenwa, C. and Elkind, M.S.V. (2017). Stroke Risk Factors, Genetics, and Prevention. Circulation Research, [online] 120(3), pp.472–495. [CrossRef]

- Borchardt, J.K. (2002). The beginnings of drug therapy: Ancient mesopotamian medicine. Drug News & Perspectives, 15(3), p.187. [CrossRef]

- Burnham, G., Hoe, C., Hung, Y.W., Ferati, A., Dyer, A., Hifi, T.A., Aboud, R. and Hasoon, T. (2011). Perceptions and utilization of primary health care services in Iraq: findings from a national household survey. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Cetorelli, V. and Shabila, N.P. (2014). Expansion of health facilities in Iraq a decade after the US-led invasion, 2003–2012. Conflict and Health, 8(16). [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, B., Wang, J., Wu, S., Maglione, M., Mojica, W., Roth, E., Morton, S.C. and Shekelle, P.G. (2006). Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Annals of internal medicine, [online] 144(10), pp.742–52. [CrossRef]

- Frost & Sullivan (2018). Assessment of Opportunities in Iraq, an Untapped Market, 2018. Frost & Sullivan.

- Hadzović S (1997). [Pharmacy and the great contribution of Arab-Islamic science to its development]. PubMed, 51(1-2), pp.47–50.

- Hayder, A., Saman Zartab, Jaberidoost, M., Alireza Yektadoost, Shekoufeh Nikfar and Abbas Kebriaeezadeh (2017). Iranian Pharmaceutical Industry Opportunities in Iraq. Journal of Pharmacoeconomics & Pharmaceutical Management, 3(3/4), pp.35–40.

- Hussain, A. and Lafta, R. (2019). Burden of non-communicable diseases in Iraq after the 2003 war. Saudi Medical Journal, 40(1), pp.72–78. [CrossRef]

- I. Rasheed, J. and M. Abbas, H. (2017). Implementation of a Clinical Pharmacy Training Program in Iraqi Teaching Hospitals : Review Article. Iraqi Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences ( P-ISSN 1683 - 3597 E-ISSN 2521 - 3512), 21(1), pp.1–5. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S., Al-Dahir, S., Al Mulla, T., Lami, F., Hossain, S.M.M., Baqui, A. and Burnham, G. (2021). Resilience of health systems in conflict affected governorates of Iraq, 2014–2018. Conflict and Health, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (2000). To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. [online] Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (2001). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund (2023). World Economic Outlook: Navigating Global Divergences. Washington D.C., USA: International Monetary Fund.

- Lane, R. (2013). Thamer Kadum Al Hilfi: looking ahead to a healthier Iraq. The Lancet, 381(9870), p.897. [CrossRef]

- Management Partners (2013). Iraq Pharmaceuticals Market Opportunities. [online] Management Partners. Management Partners. Available at: https://www.m-partners.biz/files/6414/2062/5670/Iraq_Pharmaceuticals_Market_Opportunities.pdf [Accessed 28 May 2024].

- Matsunaga, H. (2019). The Reconstruction of Iraq after 2003 : Learning from Its Successes and Failures. Washington, D.C., USA: The World Bank.

- Moore, M., Anthony, C.R., Lim, Y.-W., Jones, S.S., Overton, A. and Young, J.K. (2014). The Future of Health Care in the Kurdistan Region - Iraq: Toward an Effective, High-Quality System with an Emphasis on Primary Care. Rand Health Q, 4(2), p.1.

- Mosawi, A. (2020). Iraq: Stabilizing a Growing Market. [online] PharmExec. Available at: https://www.pharmexec.com/view/iraq-stabilizing-growing-market [Accessed 27 May 2024].

- Ondere, L. and Garfield, S. (2015). Role of Economics, Health, And Social And Political Stability In Determining Health Outcomes. Value in Health, 18(7), p.A564. [CrossRef]

- Pi-Sunyer, F.X. (2006). Use of Lifestyle Changes Treatment Plans and Drug Therapy in Controlling Cardiovascular and Metabolic Risk Factors. Obesity (Silver Spring), 14(Suppl 3), pp.135S142S. [CrossRef]

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (n.d.). State Company for Drugs Industry & Medical Appliances . [online] Available at: https://www.sdisamarra.com/index.php [Accessed 11 June. 2024].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (n.d.). State Company for Marketing Drugs and Medical Appliances (KIMADIA) . [online] Baghdad, Iraq: Ministry of Health. Available at: https://kimadia.iq/en [Accessed 20 Mar. 2024].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (2012). Technical Affairs Directorate: National Board for Drug Selection. [online] Baghdad, Iraq: Ministry of Health. Available at: http://www.tecmoh.com/mfollow.php [Accessed 11 June. 2024].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (2015). National Health Policy 2014-2023. [online] Baghdad, Iraq: Ministry of Health. Available at: https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/iraq/iraqs_national_health_policy_2014-2023.pdf [Accessed 10 Aug. 2024].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (2019a). Health Situation in Iraq: Challenges and priorities for action . [online] Baghdad, Iraq: Ministry of Health . Available at: https://moh.gov.iq/upload/upfile/ar/1001.pdf [Accessed 2 Oct. 2024].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (2019b). Samarra Drug Company: Plans Report. [online] Available at: https://www.sdisamarra.com/plan.pdf [Accessed 11 Aug. 2023].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (2020a). Pharmacetuical country profile. [online] Baghdad, Iraq: Ministry of Health. Available at: https://moh.gov.iq/upload/upfile/ar/1375.pdf [Accessed 20 Aug. 2023].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (2020b). Pharmaceuticals. [online] Baghdad, Iraq: Ministry of Health. Available at: http://www.tec-moh.com/herbals.php. [Accessed 10 Aug. 2024].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Health (2023). Iraqi New Medical Journal. [online] www.iraqinmj.com. Available at: http://www.iraqinmj.com/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2024].

- Republic of Iraq Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (2017). Iraqi Private and Public Schools of Pharmacy . [online] Available at: https://mohesr.gov.iq/ar/ministry_uploads/2017/10/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%87%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A9.pdf. [Accessed 15 Aug. 2024].

- Sharrad, A., Hassali, M. and Shafie, A. (2008). Generic medicines: Perceptions of Physicians in Basrah, Iraq. Australas Medical Journal, pp.58–64. [CrossRef]

- Suhrcke, M., McKee, M. and Rocco, L. (2007). Health investment benefits economic development. The Lancet, 370(9597), pp.1467–1468. [CrossRef]

- Summan, A., Stacey, N., Birckmayer, J., Blecher, E., Chaloupka, F.J. and Laxminarayan, R. (2020). The potential global gains in health and revenue from increased taxation of tobacco, alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages: a modelling analysis. BMJ Global Health, [online] 5(3), p.e002143. [CrossRef]

- Syndicate of Iraqi Phamacists (2023a). Drug Stores. [online] Baghdad, Iraq. Available at: https://iraqipharm.org/IDManagement/Display/DrugStore [Accessed 10 June. 2024].

- Syndicate of Iraqi Phamacists (2023b). Pharmacies. [online] Syndicate of Iraqi Phamacists. Available at: https://iraqipharm.org/IDManagement/Display/pharmacy [Accessed 10 June 2023].

- Syndicate of Iraqi Phamacists (2023c). Scientific Bureaus. [online] Available at: https://iraqipharm.org/IDManagement/Display/scientificbureau [Accessed 10 June 2024].

- Syndicate of Iraqi Phamacists (n.d.). Statement of the General Assembly’s decision. [online] www.iraqipharm.com. Available at: http://www.iraqipharm.com/?p=6462. [Accessed 10 June. 2024].

- Syndicate of Iraqi Pharmacists (2021). Drug Pricing. [online] www.iraqipharm.com. Available at: http://www.iraqipharm.com/?page_id=2254 [Accessed 20 Mar. 2024].

- Tawfik-Shukor, A. and Khoshnaw, H. (2010). The impact of health system governance and policy processes on health services in Iraqi Kurdistan. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 10(14). [CrossRef]

- Torpy, J.M. (2009). Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors. JAMA, [online] 302(21), p.2388. [CrossRef]

- Underwood, G. (2020). Country focus: Iraq’s pharma industry sees upward trajectory. [online] pharmaphorum. Available at: https://pharmaphorum.com/views-analysis-market-access/country-focus-iraq-pharma-industry [Accessed 3 Oct. 2024].

- UNICEF and World Bank (2020). Assessment of COVID-19 Impact on Poverty and Vulnerability in Iraq. [online] Available at: https://www.unicef.org/iraq/media/1181/file/Assessment%20of%20COVID-19%20Impact%20on%20Poverty%20and%20Vulnerability%20in%20Iraq.pd.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2022). World Population Prospects 2022. [online] United Nations. Available at: https://population.un.org/wpp/. [Accessed 10 Oct. 2024].

- United States of America Department of Commerce (2018). Healthcare Resource Guide: Iraq. [online] Washington D.C., USA: United States of America Department of Commerce. Available at: https://2016.export.gov/industry/health/healthcareresourceguide/eg_main_116238.asp [Accessed 20 Sept. 2024].

- USAID (2006). Iraq Competitiveness Analysis: Final Report. [online] Washington D.C., USA: USAID. Available at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadh732.pdf.

- Vandoros, S. and Stargardt, T. (2013). Reforms in the Greek pharmaceutical market during the financial crisis. Health Policy, 109(1), pp.1–6. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (2010). Strengthening the Pharmaceutical Industry and Utilization of Local Grown Medical Plants in Iraq. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation.

- World Health Organisation (2021). Noncommunicable diseases in Iraq. [online] World Health Organisation - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation. Available at: https://www.emro.who.int/iraq/priority-areas/noncommunicable-diseases.html [Accessed 10 Oct. 2024].

- World Health Organisation (2023). Global Health Expenditure Database. [online] World Health Organisation Global Health Expenditure Database . Available at: https://apps.who.int/nha/database. [Accessed 10 June. 2024].

- World Health Organisation (2024). Iraq data | World Health Organisation. [online] World Health Organisation Data. Available at: https://data.who.int/countries/368 [Accessed 10 Sept. 2024].

- World Health Organisation (2013). Country cooperation strategy for WHO and Iraq: 2012 - 2017 1 January 2013. Cairo, Egypt: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) (2020). Global health estimates: Leading causes of DALYs. [online] World Health Organisation. Available at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/global-health-estimates-leading-causes-of-dalys.

- World Health Organisation and Alwan, A. (2004). The Current Situation, Our Vision for the Future and Areas of Work, Second Edition. [online] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation. Available at: https://www.who.int/hac/crises/irq/background/Iraq_Health_in_Iraq_second_edition.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 20 Sept. 2024].

- World Health Organisation and Government of Iraq (2009). The Government of Iraq and WHO Joint Program Review Mission (JPRM),the first round discussions held inside Iraq since 2001. [online] World Health Organisation - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Available at: https://www.emro.who.int/iraq-press-releases/2010/thegovernmentofiraqandwhojointprogramreviewmissionjprm.html [Accessed 20 Sept. 2024].

- World Health Organisation (2013). WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring System. [online] www.who.int. Available at: https://www.who.int/who-global-surveillance-and-monitoring-system [Accessed 11 Oct. 2024].

- Zebari, A. (2013). Modernization of drug distribution in Kurdistan : Is it possible to implement the Swedish drug distribution system in Kurdistan?

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).