1. Introduction

Children with developmental coordination disorder (DCD) experience impaired motor skills that interfere with age-related daily activities, which may be in the context of home, school, or play [

1]. Movement difficulties often lead to issues in psychosocial skills, learning abilities, and participation in various forms of daily activities. DCD is typically diagnosed when children are aged between five and eleven years, usually without any other medical or neurologic diagnosis. DCD affects approximately 5% to 6% of children globally, but due to the use of different diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of DCD varies across countries, ranging from 2% to 20% [

2]. For example, studies have reported prevalence rates of 2% in Turkey [

3], 9% in Taiwan [

4], 11% in South Korea [

5], and nearly 20% in Brazil [

6]. In Hong Kong, there is no official published prevalence of DCD in children. Previous studies that screened primary school children for participant recruitment using movement battery tests reported rates ranging from 6% to 21% [

7,

8,

9]. While the education sector has increasingly strengthened programs for children with special educational needs, there continues to be limited awareness of DCD in Hong Kong. This limited awareness and attention is likely due, in part, to the lack of knowledge about the extent to which DCD affects the local population. Therefore, we aimed to estimate the extent to which children in Hong Kong might be affected by probable DCD.

Children are diagnosed with DCD when they meet the criteria set by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - 5th edition (DSM-5) [

1], which includes the following: (i) learning and execution of coordinated motor skills is below the expected level for age, given opportunities for skill learning; (ii) motor skill difficulties significantly interfere with activities of daily living and impact academic/school productivity, prevocational and vocational activities, leisure and play; (iii) onset is in the early developmental period; and (iv) motor skill difficulties are not better explained by intellectual delay, visual impairment or other neurological conditions that affect movement. The first criterion is typically assessed using examiner-administered standardized measures of motor performance, whereas the second criterion may be assessed using parent- or teacher-proxy reports of children’s performance in daily functions related to motor skills [

2]. As the latter two criteria are assessed based on clinical history and other neurological tests, DCD is typically diagnosed in settings where detailed assessments can be conducted.

For the purpose of estimating prevalence, motor coordination test batteries may be impractical because of time and cost constraints. Researchers advocate the use of motor-based questionnaires completed by children, teachers, and parents as a more feasible form of screening. Self-report measures are particularly valuable because they allow for quick and efficient assessment of children’s motor skills without the need for extensive resources or trained professionals. Among these questionnaires, the Developmental Coordination Disorder Parent Questionnaire (DCDQ) has been validated extensively in the literature [

10,

11]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that the DCDQ has acceptable diagnostic accuracy and adequate predictive validity to be a suitable screening tool for identifying children with motor coordination difficulties [

12]. It has also been used as a supplementary tool in clinical settings to diagnose DCD. DCDQ focuses on parent-reported activity levels of the child (e.g., self-care, ball skills) and underlying body functions, highlighting the motor difficulties experienced by children. Although DCDQ may not lead to an accurate DCD diagnosis, it can provide valuable information on the extent to which DCD affects a population. Based on DCDQ scores, children are categorized as either suspect for DCD (sDCD) or probably not DCD (nDCD). For example, it was estimated that 12% of children in mainstream schools in Spain were sDCD [

13]. A child being categorized as sDCD may not lead to a diagnosis, but it reflects the need for specialized support to manage motor difficulties.

In addition to motor difficulties, children with DCD have also been documented to have difficulties in other domains of health and development. In regard to physical health, for example, they tend to be less physically active than peers without DCD [

16]. In a study of children with DCD in Hong Kong, only one out of three children met physical activity guidelines [

9]. In terms of development, children with DCD may also have impaired psychosocial skills, learning difficulties, and short attention span [

17,

18]. These issues tend to have a negative impact on their participation in daily life activities and education outcomes [

2]. Some evidence of this in Hong Kong has been reported, where children with DCD were found to have low emotional and social efficacy and difficulty participating in home- and community-based activities that require motor, communication, or organizational skills [

15]. As such, in estimating the extent to which DCD affects children in Hong Kong, it is also important to assess the associated difficulties in health and daily functioning to inform policies that support children in navigating their social and learning environments [

19].

Currently, knowledge of the extent to which DCDs might affect children in Hong Kong is inadequate to inform the direction of public policy and practice. To address this gap, we conducted a survey study using the DCDQ to estimate the prevalence of children who are sDCD in Hong Kong, with consideration for individual and family characteristics. We also explored the association of motor difficulties with health-related daily functioning. We hypothesized that children who are sDCD will have poorer outcomes in terms of global health, physical activity, positive affect, and cognitive function than children who are nDCD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

While early identification of children with motor difficulties is recommended to allow for early intervention [

20,

21], diagnosing DCD before the age of five is generally discouraged. This is due to several challenges: young children may show delayed motor development that resolves on its own; their cooperation and motivation during assessments can be inconsistent, leading to unreliable results; and there is high variability in the ability to acquire activities of daily living skills [

2,

22]. As such, the current study focused on children aged at least five years.

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional research ethics committee (Ref. 2021--2022--0446). The participants were recruited through Qualtrics online research panels, and data collection took place between October and December 2022. Informed consent was obtained online. We received 656 responses from parents who met the following eligibility criteria: (i) had at least one child aged 5–12 years and (ii) resided in Hong Kong. The final sample (N = 632) includes those who submitted complete responses and represents the population proportions between male and female children across the three major districts of Hong Kong. The sample size exceeded our target based on the global DCD prevalence of 6%, with a confidence interval of 95% and an error of 2%.

2.1. Instruments

The survey included three parts: the Chinese version of the DCDQ [

14,

15]; the short forms on global health, physical activity, positive affect, and cognitive function of the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS

®) parent proxy scale [

23]; and demographic information.

2.1.1. DCDQ

The DCDQ is a parent-report measure used to assist in the identification of children who are likely to have DCD and is suitable for children aged 5-15 years [

11]. Parents are asked to compare their child’s motor performance to that of his/her peers via a five-point Likert scale across 15 items that are grouped into three factors: control during movement (DCDQ-CM, 6 items), fine motor/handwriting (DCDQ-FM, 4 items), and general coordination (DCDQ-GC, 5 items). The total scores range from 15 to 75, where higher scores reflect better motor performance. Age-specific cutoff scores are applied to classify children as “suspect for” (below the 15

th percentile) or “probably not” DCD [

15]. International practice recommendations have noted that the DCDQ has good evidence supporting its psychometric properties [

2]. In this study, we used the version of the questionnaire developed for Chinese-speaking communities [

14], which has been used in Hong Kong and found to have good internal consistency and construct validity [

15].

2.1.2. PROMIS®

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a set of person-centered scales that measure physical, mental, and social health in adults and children, including parent-proxy scales for children aged 5-17 years [

23]. It consists of item banks that have been extensively tested for validity and reliability [

24,

25,

26]. The PROMIS items were evaluated using item response theory, such that any subset of items generates standardized scores on the same scale [

27]. The parent-proxy report scales include five response options that reflect their child's experiences over the past week. Raw scores are calculated on the basis of the sum of the scale items, which are then converted into t-scores where higher scores reflect better health status [

28]. We used parent-proxy report scales for global health, physical activity, positive affect, and cognitive function.

2.1.3. Demographic Information

The demographic information included the child’s age and sex, the responding parent’s age, sex, educational attainment, and the monthly household income.

2.1. Data Processing and Analysis

Each DCDQ item was scored on a 5-point scale, with negatively worded items scored in reverse. Factor scores were calculated, where the highest possible scores were 30 for DCDQ-CM, 20 for DCDQ-FM, and 25 for DCDQ-GC. Children below the 15th percentile within each age group were categorized as sDCD. Following the DCDQ procedures, the three age groups are 5 years to 7 years and 11 months, 8 years to 9 years and 11 months, and 10 to 12 years.

The PROMIS parent-proxy report items are scored on a 5-point scale. The highest possible scores are 35 for global health, 20 for physical activity, 20 for positive affect, and 35 for cognitive function. Raw sum scores were used because the corresponding t scores were based on reference data from the USA, which limits their applicability to the Hong Kong population [

29].

The internal consistency of the respective items in the DCDQ and PROMIS scales was assessed based on Cronbach’s alpha. The Shapiro‒Wilk test revealed that the DCDQ and PROMIS scores were not normally distributed; hence, non-parametric inferential tests were used to test the hypotheses. To test whether motor difficulties are associated with demographic characteristics and health-related daily functioning, we calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients among the DCDQ scores, demographic data, and PROMIS scores.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the participants and the categorization of the children into sDCD and nDCD groups. Logistic regression was used to test the contribution of the child’s age and sex, parental educational attainment and age, and household income to DCDQ categorization.

To test whether children categorized as sDCD have lower outcomes in terms of global health, physical activity, positive affect, and cognitive function, we performed Kruskal‒Wallis tests to compare the PROMIS scores of children categorized as sDCD and those of children categorized as nDCD.

3. Results

The characteristics of the parent respondents and their children are summarized in

Table 1. The mean age of the children was 8.50 ± 2.19 years, and they were grouped into three age groups corresponding to those of the DCDQ cutoff scores (see

Table 1).

Internal consistency is excellent for the DCDQ-CM subscale (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) and good for the DCDQ-FM (Cronbach’s α = 0.88) and DCDQ-GC (Cronbach’s α = 0.88) subscales. Internal consistency is excellent for the PROMIS scales for positive affect (Cronbach’s α = 0.92) and cognitive function (Cronbach’s α = 0.91), good for global health (Cronbach’s α = 0.84), and acceptable for physical activity (Cronbach’s α = 0.67).

3.1. Suspect for DCD (sDCD) Prevalence

Based on the total DCDQ scores, 18.29% (n = 120) of the participants were categorized as sDCD. Logistic regression revealed that household income (OR 0.79, p = 0.001) and the age of the child (OR 1.01, p = 0.002) contributed to children being categorized as sDCD. Those who had a lower household income and were older were more likely to be categorized as sDCD. Child sex, parental sex and educational attainment were not significant predictors of the DCDQ category.

Considering the contribution of age to being categorized as sDCD, we further examined the distribution of participants to sDCD and nDCD in the three age cutoffs in the DCDQ. Among children aged 5 years to 7 years and 11 months, 13.31% (n = 39) were categorized as sDCD. Among children aged 8 years to 9 years and 11 months, 20.52% (n = 32) were categorized as sDCD. Among children aged 10 to 12 years, 23.78% (n = 49) were categorized as sDCD.

3.2. Motor Difficulties and Associated Health-Related Daily Functioning

Significant correlations were found between the total DCDQ score and global health (

r = 0.52,

p < 0.001), positive affect (

r = 0.38,

p < 0.001), and cognitive functioning (

r = 0.34,

p < 0.001). The association between the total DCDQ score and physical activity was not significant (

r = 0.06,

p = 0.15). Only the DCDQ-GC subscale was significantly correlated with physical activity (

r = 0.08,

p = 0.04).

Table 2 summarizes the correlations among the DCDQ total scores and the subscales with the health-related functioning scales.

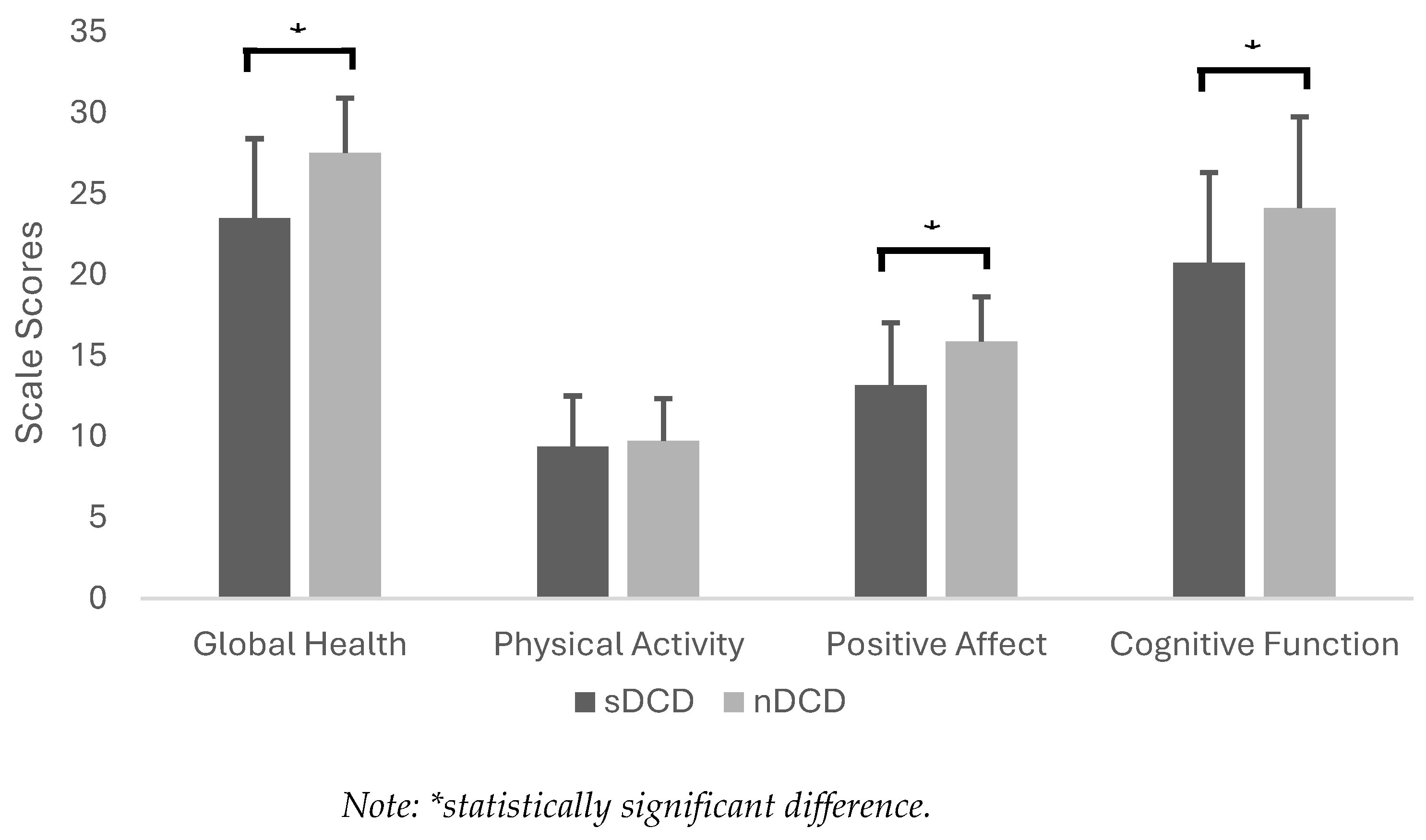

Significant differences were found in global health (

H(1) = 73.95,

p < 0.001), positive affect (

H(1) = 63.79,

p < 0.001), and cognitive function (

H(1) = 30.94,

p < 0.001) between the sDCD and nDCD groups of children (see

Figure 1). Children in the sDCD group had significantly lower scores than those in the nDCD group. There was no statistically significant difference in the physical activity score between the two groups (

H(1) = 0.15,

p = 0.70).

4. Discussion

We aimed to estimate the prevalence of sDCD in a large sample of children in Hong Kong while considering individual and family characteristics. We compared the health-related daily functioning of children categorized as sDCD with that of those categorized as nDCD. Our findings revealed a relatively high prevalence of sDCD in Hong Kong children aged 5 to 12 years. The prevalence of 18.29% is higher than the estimate from a validation study of DCDQ in Hong Kong, which was 13% [

15]. Compared with rates reported by other studies that used the DCDQ, our current estimate of the prevalence of sDCD in Hong Kong is higher than 12% in Spain [

13] but lower than 21% in India [

30] and 30% in Brazil [

31].

The relatively high prevalence of sDCD that we found in this study might be related to the recent COVID-19 pandemic. We note that we gathered data in late 2022, which was a period when school-aged children in Hong Kong were still affected by pandemic-related restrictions. In-person classes fully resumed in November 2022 for secondary schools and in December 2022 for primary schools subject to vaccination requirements [

32]. Masks in schools remained mandatory, and vaccine requirements limited extracurricular activities (e.g., sports and games) until early 2023. Parents’ responses to our survey were likely influenced by the school-related disruptions that children and families experienced during the pandemic. School-aged children also displayed lower physical activity levels and longer screen time during periods of school suspension [

33]. Such changes in movement behaviors likely influenced parents’ perceptions of their children’s motor difficulties and daily functioning as well.

The high prevalence rate we observed can be interpreted in two ways. On one hand, it is important to consider the prevalence rate carefully because of temporal factors. A follow-up investigation is warranted to assess the prevalence of sDCD during periods of unrestricted social conditions and typical school programming, as opposed to the conditions experienced during the pandemic. On the other hand, given the high prevalence rate, programs that support motor development are necessary in schools to address a problem that may have been exacerbated by the recent pandemic. Our findings further revealed that the prevalence rate steadily increased across the three age groups, where a higher prevalence of sDCD was found in older children. Researchers have highlighted that motor problems tend to be heightened in older children because greater demands for motor skills are experienced in both school and social settings [

34]. While this may imply that movement programs are especially important in older children, given the higher prevalence rate of sDCD, we suggest that supportive programs are equally important in younger children. Earlier work has shown that the motor performance of children first identified with DCD at the age of 7 to 9 years tends to vary over time, and interventions potentially move children out of the DCD classification [

35]. We therefore suggest that movement programs in early primary school could mitigate the motor difficulties of children with sDCD, which may otherwise worsen as they grow older. It is also important to consider long-term consequences, especially since motor difficulties in the early primary years tend to contribute to health issues such as insufficient physical activity in adolescence [

36].

Studies have shown that children with DCD aged between 6 and 14 years have significantly lower physical activity levels than their typically developing peers [

37], so we expected that children categorized as sDCD would have lower physical activity levels than those categorized as nDCD. Our findings do not support this, because low physical activity levels were reported across both categories. This finding further highlights the pandemic-related movement behavior changes that children in Hong Kong experienced at the time of data gathering [

33]. Notably, physical activity promotion appears to be needed among Hong Kong children, regardless of their motor proficiency.

With respect to aspects of general health, affective state, and cognitive function, our expectation that children categorized as sDCD would have worse outcomes than those in the nDCD category was supported by our findings. Researchers have previously shown that children with DCD tend to have psychosocial skill impairments and learning difficulties [

17,

18] that subsequently negatively affect their participation in daily life activities [

2]. Our current findings further show that even when children are only suspected for DCD, they are at risk of experiencing difficulties that may lead to long-term life outcomes. We also provide further evidence that motor performance difficulties are not issues that simply relate to sports participation or physical education for school-aged children. It has been argued that the motor difficulties associated with DCD expose children to secondary stressors that could lead to psychological distress [

38,

39]. Poor motor performance, especially in early childhood, negatively affects socialization because the limited ability to participate in games and play contributes to less positive affect [

40], and difficulties with fine motor skills contribute to poor academic outcomes [

41]. In contrast, the ability to move proficiently opens a range of opportunities that contribute to interactive processes that develop social and cognitive skills. It is, therefore, highly important that teachers and parents be more aware that poor motor skills have a negative impact on the overall health and well-being of children categorized as sDCD.

Supportive programs for children categorized as sDCD also need to be holistic to address not only motor difficulties but also self-efficacy and motivation through interventions that are grounded in theory. For example, the Optimizing Performance through Intrinsic Motivation and Attention for Learning (OPTIMAL) theory of motor learning emphasizes that practice of motor skills should enhance learners’ expectations for successful outcomes to motivate children toward increased engagement with the program [

42]. Strategies such as errorless motor learning facilitate successful practice experiences [

43] that could contribute to such enhanced expectancies.

Finally, we note that children from lower-income households tend to have a greater likelihood of being categorized as sDCD. This finding is consistent with previous research that has shown that having higher household income tends to have a protective effect on the risk of children having DCD [

44]. It is generally understood that children from families with low socioeconomic status tend to have less access to resources and opportunities that promote child development [

45]. While Hong Kong is categorized by the World Bank as a high-income territory, there has been a significant rise in wealth and income inequality in recent decades [

46]. The most recent report based on census data revealed that the overall poverty rate reached 20% [

47]. Importantly, the risk of children having developmental disorders, including DCD, increases with worsening poverty in the territory.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study sample represents the proportion of our target population by sex and the distribution across the territory of Hong Kong. It was also sufficiently large to achieve a 95% confidence level and 2% margin of error. Nevertheless, we emphasize that the DCDQ categorizes children as suspect for or probably not DCD and does not equate to a formal diagnosis of DCD. To establish a prevalence rate of children diagnosed with DCD, further studies are needed that consider the DSM-5 criteria [

1] and utilize motor proficiency tests [

5]. Notably, our data were gathered during the last stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong. As such, the issues during the pandemic could have contributed to the relatively high prevalence of sDCD that we found; therefore, a post-pandemic follow-up study is recommended. We also acknowledge that participants' estimates of their children's performance of daily functions may have been biased due to self-reporting. Future investigations should consider collecting more objective data by directly observing how participants complete the survey and assessing their motor skills. Finally, the cross-sectional associations of the sDCD categorization with health and daily functioning inherently limit causal inference. Longitudinal studies are needed to further establish evidence in this respect.

5. Conclusions

We estimate that up to 18.29% of children in Hong Kong may be categorized as sDCD, with the prevalence rate being higher in older children. Children from lower income households may be at greater risk of being categorized as sDCD. Motor difficulties are associated with health-related daily functioning, where children categorized as sDCD have significantly worse global health, less positive affect, and greater cognitive difficulties. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the extent to which DCD might be affecting Hong Kong children and could be used to improve the general awareness of DCD among teachers and parents. Further research is recommended to establish more robust estimates that may be reflective of children diagnosed with DCD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.C., S.K.C., and K.K.H.C.; methodology and formal analysis, C.M.C. and K.F.E.; resources, C.M.C.; writing – original draft preparation, K.F.E. and C.M.C.; writing – revisions, all authors; project administration, C.M.C.; funding acquisition, C.M.C. and K.K.H.C. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hong Kong Dyspraxia Foundation and the Research Matching Grant Scheme of the Research Grants Council in Hong Kong, CB343.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Education University of Hong Kong (Ref. 2021-2022-0446, approved on 9 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available through request to the corresponding author, ccapio@hkmu.edu.hk.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; 5th, Text Revised ed.; 2022;

- Blank, R.; Barnett, A.L.; Cairney, J.; Green, D.; Kirby, A.; Polatajko, H.; Rosenblum, S.; Smits-Engelsman, B.; Sugden, D.; Wilson, P.; et al. International Clinical Practice Recommendations on the Definition, Diagnosis, Assessment, Intervention, and Psychosocial Aspects of Developmental Coordination Disorder. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2019, 61, 242–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabak, M.; Akıncı, M.A.; Yıldırım Demirdöğen, E.; Bozkurt, A. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Developmental Coordination Disorder in Primary School Children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-C.; Tseng, Y.-T.; Hsu, F.-Y.; Chao, H.-C.; Wu, S.K. Developmental Coordination Disorder and Unhealthy Weight Status in Taiwanese Children: The Roles of Sex and Age. Children 2023, 10, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Jung, T.; Lee, D.K.; Lim, J.-C.; Lee, E.; Jung, Y.; Lee, Y. A Comparison of Using the DSM-5 and MABC-2 for Estimating the Developmental Coordination Disorder Prevalence in Korean Children. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2019, 94, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, N.C.; Coutinho, M.T.C.; Pansera, S.M.; Santos, V.A.P. dos; Vieira, J.L.L.; Ramalho, M.H.; Oliveira, M.A. de Prevalence of Motor Deficits and Developmental Coordination Disorders in Children from South Brazil. Rev. paul. pediatr. 2012, 30, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, V.K.L.; Stagnitti, K.; Lo, S.K. Screening Children With Developmental Coordination Disorder: The Development of the Caregiver Assessment of Movement Participation. Children’s Health Care 2010, 39, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, C.H.; Yu, J.J.; Wong, S.H.; Capio, C.M.; Masters, R. A School-Based Physical Activity Intervention for Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2019, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Capio, C.M.; Abernethy, B.; Sit, C.H.P. Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Children with and without Developmental Coordination Disorder: Associations with Fundamental Movement Skills. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2021, 118, 104070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.N.; Kaplan, B.J.; Crawford, S.G.; Campbell, A.; Dewey, D. Reliability and Validity of a Parent Questionnaire on Childhood Motor Skills. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2000, 54, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.N.; Crawford, S.G.; Green, D.; Roberts, G.; Aylott, A.; Kaplan, B.J. Psychometric Properties of the Revised Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics 2009, 29, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Kim, E.Y. Predictive Validity of the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire as a Screening Tool to Identify Motor Skill Problems: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2024, 150, 104748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Lobete, L.; Santos-del-Riego, S.; Pértega-Díaz, S.; Montes-Montes, R. Prevalence of Suspected Developmental Coordination Disorder and Associated Factors in Spanish Classrooms. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2019, 86, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-H.; Fu, C.-P.; Wilson, B.N.; Hu, F.-C. Psychometric Properties of a Chinese Version of the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire in Community-Based Children. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2010, 31, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.Y. Unveiling Issues Limiting Participation of Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder: From Early Identification to Insights for Intervention. J Dev Phys Disabil 2018, 30, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.E.; Furzer, B.J.; Licari, M.K.; Thornton, A.L.; Dimmock, J.A.; Naylor, L.H.; Reid, S.L.; Kwan, S.R.; Jackson, B. Physiological Characteristics, Self-Perceptions, and Parental Support of Physical Activity in Children with, or at Risk of, Developmental Coordination Disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2019, 84, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrowell, I.; Hollén, L.; Lingam, R.; Emond, A. The Impact of Developmental Coordination Disorder on Educational Achievement in Secondary School. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2018, 72, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.; Jijon, A.M.; Leonard, H.C. Research Review: Internalizing Symptoms in Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2019, 60, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, Á.; Stanley, M.; Coote, S.; Robinson, K. Children and Young People’s Experiences of Living with Developmental Coordination Disorder/Dyspraxia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography of Qualitative Research. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0245738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, J.G.; Lee, E.J. Early Intervention for Children with/at Risk of Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Scoping Review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2021, 63, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, D.L. Early Identification and Intervention in Developmental Coordination Disorder: Lessons for and from Cerebral Palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2021, 63, 630–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A.; Sugden, D.; Purcell, C. Diagnosing Developmental Coordination Disorders. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2014, 99, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PROMIS Health Organization PROMIS Instrument Development and Validation Scientific Standards (Version 2. 0) 2013.

- Varni, J.W.; Thissen, D.; Stucky, B.D.; Liu, Y.; Gorder, H.; Irwin, D.E.; DeWitt, E.M.; Lai, J.-S.; Amtmann, D.; DeWalt, D.A. PROMIS® Parent Proxy Report Scales: An Item Response Theory Analysis of the Parent Proxy Report Item Banks. Qual Life Res 2012, 21, 1223–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.E.; Gross, H.E.; Stucky, B.D.; Thissen, D.; DeWitt, E.M.; Lai, J.S.; Amtmann, D.; Khastou, L.; Varni, J.W.; DeWalt, D.A. Development of Six PROMIS Pediatrics Proxy-Report Item Banks. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Walt, D.A.; Gross, H.E.; Gipson, D.S.; Selewski, D.T.; DeWitt, E.M.; Dampier, C.D.; Hinds, P.S.; Huang, I.-C.; Thissen, D.; Varni, J.W. PROMIS® Pediatric Self Report Scales Distinguish Subgroups of Children Within and Across Six Common Pediatric Chronic Health Conditions. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation 2015, 24, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, B.B.; Hays, R.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Cook, K.F.; Crane, P.K.; Teresi, J.A.; Thissen, D.; Revicki, D.A.; Weiss, D.J.; Hambleton, R.K.; et al. Psychometric Evaluation and Calibration of Health-Related Quality of Life Item Banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care 2007, 45, S22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothrock, N.E.; Amtmann, D.; Cook, K.F. Development and Validation of an Interpretive Guide for PROMIS Scores. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes 2020, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, C.B. Common Measures or Common Metrics? The Value of IRT-Based Common Metrics. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes 2023, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komal, K.B.; Sanjay, P. Indication or Suspect of Developmental Coordination Disorder in 5-15 Years of School Going Children in India (Dharwad, Karnataka). -. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research 2014, 4, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Barba, P.C. de S.D.; Luiz, E.M.; Pinheiro, R.C.; Lourenço, G.F. Prevalence of Developmental Coordination Disorder Signs in Children 5 to 14 Years in São Carlos. Motricidade 2017, 13, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, T.K.; Huang, X.; Fong, M.W.; Wang, C.; Lau, E.H.; Wu, P.; Cowling, B.J. Effects of School-Based Preventive Measures on COVID-19 Incidence, Hong Kong, 2022. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2023, 29, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therefore, H.-K.; Chua, G.T.; Yip, K.-M.; Tung, K.T.S.; Wong, R.S.; Louie, L.H.T.; Tso, W.W.Y.; Wong, I.C.K.; Yam, J.C.; Kwan, M.Y.W.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on School-Aged Children’s Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Sleep in Hong Kong: A Cross-Sectional Repeated Measures Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 10539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Su, X.; Yang, S.; Du, Z.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y. New Trends in Developmental Coordination Disorder: Multivariate, Multidimensional and Multimodal. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugden, D.A.; Chambers, M.E. Stability and Change in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder. Child Care Health Dev 2007, 33, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Lingam, R.; Mattocks, C.; Riddoch, C.; Ness, A.; Emond, A. The Risk of Reduced Physical Activity in Children with Probable Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2011, 32, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.-T.; Ho, W.-C.; Chou, L.-W.; Li, Y.-C. Objectively Measured Physical Activity in Children With Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2024, S0003-9993(24)01055-4. [CrossRef]

- Missiuna, C.; Campbell, W.N. Psychological Aspects of Developmental Coordination Disorder: Can We Establish Causality? Curr Dev Disord Rep 2014, 1, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caçola, P. Physical and Mental Health of Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder. Front Public Health 2016, 4, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, H.C. The Impact of Poor Motor Skills on Perceptual, Social and Cognitive Development: The Case of Developmental Coordination Disorder. Frontiers in Psychology 2016, 7, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roebers, C.M.; Röthlisberger, M.; Neuenschwander, R.; Cimeli, P.; Michel, E.; Jäger, K. The Relation between Cognitive and Motor Performance and Their Relevance for Children’s Transition to School: A Latent Variable Approach. Human Movement Science 2014, 33, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, G.; Lewthwaite, R. Optimizing Performance through Intrinsic Motivation and Attention for Learning: The OPTIMAL Theory of Motor Learning. Psychon Bull Rev 2016, 23, 1382–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capio, C.M.; Poolton, J.M.; Sit, C.H.P.; Holmstrom, M.; Masters, R.S.W. Reducing Errors Benefits the Field-Based Learning of a Fundamental Movement Skill in Children. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2013, 23, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.-T.; Tseng, Y.-T.; Chen, S.; Wu, S.K.; Li, Y.-C. Moderation of Parental Socioeconomic Status on the Relationship between Birth Health and Developmental Coordination Disorder at Early Years. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2023, 11, 1020428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks-Gunn, J.; Duncan, G.J. The Effects of Poverty on Children. Future Child 1997, 7, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T.; Yang, L. Income and Wealth Inequality in Hong Kong, 1981–2020: The Rise of Pluto-Communism? The World Bank Economic Review 2022, 36, 803–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Hong Kong Poverty Report 2024: Pathways out of Adversity - Embracing Change through Transformation; Oxfam Hong Kong: Hong Kong SAR, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of the MDPI and/or the editor(s). The MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclose responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).