1. Introduction

As the global population lives longer, most people have an average life expectancy of more than 60 years. The global population aged 60 years and older will increase from 1 billion to 1.4 billion between 2020 and 2030, according to the study. However, with aging, the immune system gradually weakens, and the number and function of immune cells decrease, leading to weakened immune responses and reduced resistance to pathogens—collectively referred to as immunosenescence [

1]. Middle-aged and elderly people are often accompanied by chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which also affect the function of the immune system, making them more susceptible to infections and slower to recover [

2]. Therefore, immunosenescence can reduce the quality of life and health of middle-aged and elderly people, making them susceptible to colds, loss of appetite, gastrointestinal discomfort, poor sleep quality, and oral ulcers. In order to promote the development of “healthy aging”, improving the immune function of the elderly is an urgent problem to be solved.

To systematically improve the nutritional and health status and enhance the immunity of middle-aged and elderly people is the key to achieve healthy aging. As a convenient way to supplement, nutritional supplements include various vitamins, minerals, proteins and other bioactive ingredients, which can help to make up for dietary deficiencies in middle-aged and elderly people and support physical health and immune system function. Studies have suggested that oral nutritional supplements, including whole foods (such as butter, cream, eggs, etc.) or specific nutritional preparations (such as milk powder), should be given to the elderly to strengthen the diet in order to increase the energy and protein content of foods, thereby increasing nutrient extraction and improving health status and immune function [

3].

Bovine colostrum (BC) is the earliest milk secreted from the mammary gland after parturition and has a long history of human consumption [

4]. Its unique basic nutrients, immune factors, and oligosaccharides are beneficial for human. Compared with mature milk, BC contains more abundant casein, whey protein (Igs, lactoferrin) and other proteins, among which lactoferrin content is much higher than that of mature milk, about 2-250 times higher [

5]. In addition, BC contains more fat, ash, vitamins and minerals, hormones, growth factors, cytokines, nucleotides, and less lactose [

6]. Except for lactose content, the concentration of these compounds rapidly decreases in the first three days of lactation [

7]. Whey protein has the characteristic of easy digestion and absorption, which is beneficial for the absorption and utilization of protein, and may improve the continuous loss of muscle tissue in the elderly [

8]. It has been found that whey protein concentrate can enhance innate mucosal immunity early in life and has a protective effect in some immune diseases [

9]. There is some evidence that ingestion of BC can affect immune function outside the gastrointestinal tract. For example, BC supplementation may reduce the number of influenza-like episodes [

10]. Supplementation with BC has also been reported to be beneficial in reducing the number of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and diarrhea episodes in children [

11,

12], and BC IgG has been shown to bind to and neutralize human respiratory syncytial virus [

13]. At the same time, athletes who receive training are known to have an increased risk of developing urinary tract infection symptoms, and one meta-analysis reported a significant positive effect of BC supplementation [

14].

Secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) is an important immune defense substance that helps protect the oral mucosa from pathogenic microorganisms [

15,

16]. Due to the contribution of sIgA, the mucosal system can maintain the balance of mucosal immunity among symbiotic microorganisms and defend against pathogens on the mucosal surface [

17]. One study reported a significant effect of bovine colostrum supplementation on IgA in the saliva of distance runners, however the sample size was small, only 35 [

18]. Another 66-person trial looked at the effects of colostrum milk supplement among older adults, but did not measure salivary sIgA [

19]. There are limited studies on the effects of BC powder consumption on sIgA and immunity in middle-aged and elderly people [

20]. Milk powder contains a lot of protein, protein intake may stimulate the immune system, resulting in changes in oral mucosal immunoglobulin secretion level, especially in a short period of time may have a certain degree of change. Assuming that consuming BC supplement may help enhance the immune system and support the health of the middle-aged and elderly. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of BC supplementation on the immune system especially sIgA and health status in middle-aged and elderly people.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

It was a two-armed, parallel, randomized, double-blinded trail designed to evaluate the effects of daily oral intake of BC supplements for 90 days on sIgA and health status in middle-aged and elderly people.

The primary study outcome was the change in saliva sIgA concentration between baseline and day 90 of supplementation. The secondary outcome measures included serum immunoglobulin (IgA, IgG, IgM), C-reactive protein, and changes in the number and proportion of immune cells in blood routine. Additional endpoints included the results of questionnaires and self-reported health status, such as:

Oral ulcers: An ulcerative lesion that occurs on the tip or side of the tongue, the gums, the lips, and the buccal mucosa. The shape of the lesion is mostly round or oval, and the ulcer surface is covered with a yellow pseudomembrane, surrounded by a red halo band, a central depression, and obvious pain.

Sleep quality: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to evaluate sleep quality, with a total of 19 objective scores, including seven dimensions of sleep duration, subjective sleep quality, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disorders, sleep medication use and daytime dysfunction. The total score is 21 points, the higher the score indicates the worse the sleep quality, the total score ≤5 is good sleep quality, 6-10 is average sleep quality, 11-15 is poor sleep quality, and ≥16 is very poor sleep quality.

Cold: A disease limited to the upper respiratory tract, most of which is caused by viral infection, and is self-limited. The course of the disease is usually less than 10 days, and it often has the characteristics of acute rhinosinusitis. The clinical manifestations are mainly catarrhal symptoms such as sneezing, nasal congestion, runny nose, and so on [

21].

Fatigue: Lack of strength, limp and weakness.

Bitter taste: Bad mouth smell.

Diarrhea: Defecation was performed more than 3 times a day with a volume of more than 200 g/day, and stool was thin with a water content of more than 85%.

2.2. Participants

The sample size calculation was performed using Pass software. Based on previous animal experiments and literature, population immune indicators such as NK cells and IgA were obtained, and the sample size was calculated accordingly [

18]. The research power was set at 90%, with the alpha value was 0.05, and the mean difference in sIgA values between groups was 0.26, for which a minimum sample of 164 participants was required. The δ of NK cell value was 2.07, and the minimum sample size was 98. Within this interval, a larger sample size of 164 participants was selected. Considering the 10% dropout rate, a total of 180 participants were required, with 90 participants in each arm. Adults aged between 50-85 years were included in this research.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) permanent residents; (2) sign informed consent; (3) willingness to follow the study protocol.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients with active autoimmune disease; (2) individuals were allergic/intolerant to dairy products and other foods; (3) current or past history of cancer or ongoing chemotherapy regimens, and post-transplant patients; (4) take drugs that affect immunity during follow-up (such as immunosuppressive/immune-potentiating drugs).

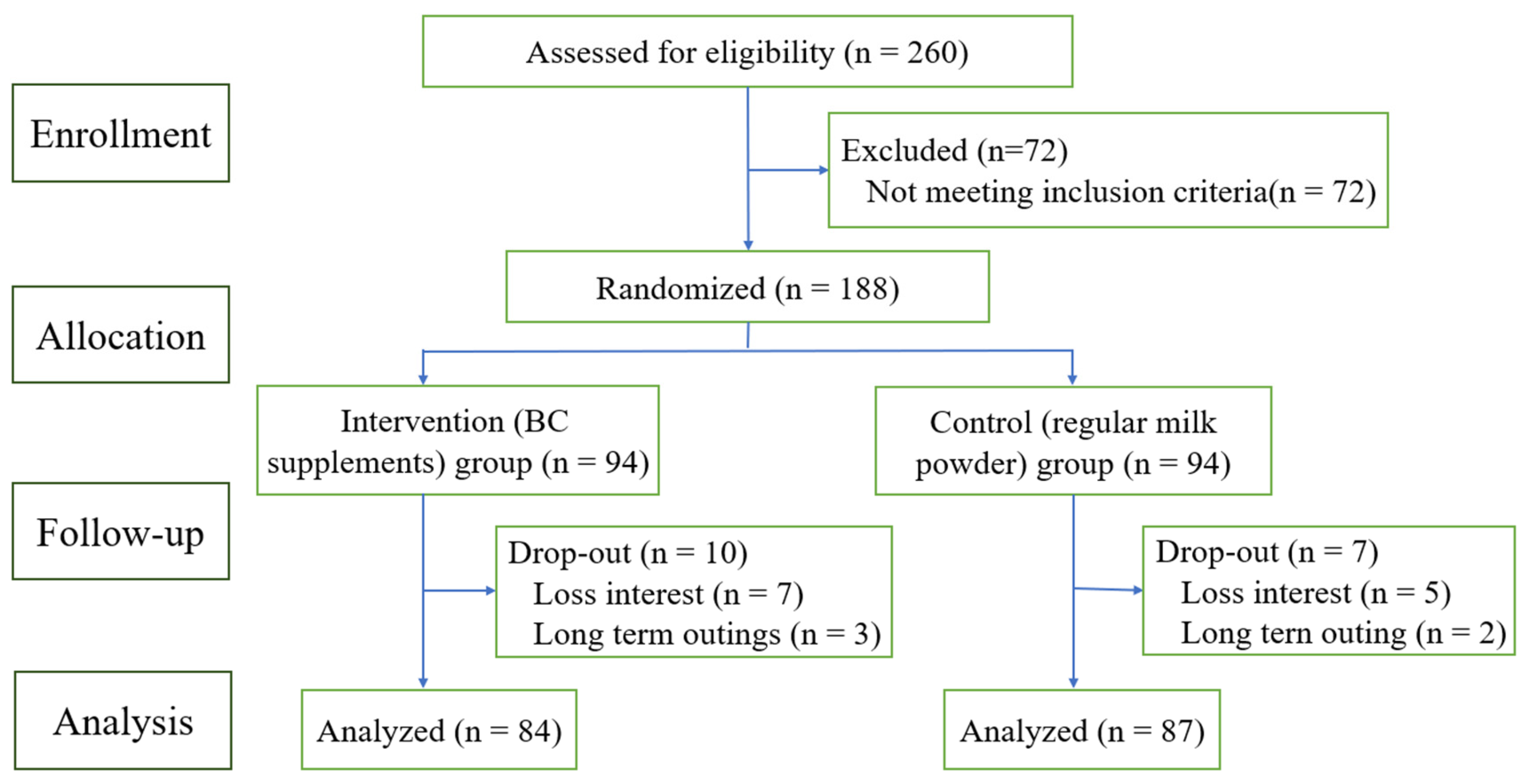

A total of 260 people came from 5 communities/institutions participated in the survey. After screening for eligibility, 188 participants were recruited. At the screening visit, the researchers reviewed the purpose of the study, study activities, and the consent form. Upon receiving written informed consent, the researchers completed questionnaire surveys, physical examinations, and sample collection including saliva and blood for each volunteer.

Simple random group design was adopted. Excel is used to generate random numbers: First, the subjects are sorted, each serial number generates a random number, and the random numbers are arranged by size and divided into two groups according to the median. Put serial numbers and random numbers into envelopes and seal them. This link is completed by the test designer, who does not participate in data collection and field work. The subjects were divided into the intervention group (BC supplement, n = 94) and the positive control group (regular milk powder, n = 94).

The consort flow chart of study is shown in

Figure 1.

2.3. Materials and Procedures

2.3.1. Intervention and Blinding

Table S1 shows the comparison of ingredients between BC supplement powder and regular milk powder. Participants were instructed to ingest the supplements twice daily. The trail was double-blind. The outer packaging of the milk powder is uniformly a white box, only indicating the method of use and the number 1 or 2. Internally, it is uniformly packaged in silver bags, with a box of 16 bags, each bag weighing 28 grams, and a box enough for 8 days. Both the project staff and the participants were unaware of the specific type of milk powder used in 1 and 2. After the trial, the research designer would unblind. The total trial duration was approximately 90 days. Throughout the intervention process, participants were asked to save and submit empty milk powder bags to measure compliance.

2.3.2. Compliance

Empty bags were collected from participants after milk powder administration at all three follow-up visits, and the number was recorded. Everyone should take two bags of milk powder per day, and compliance was calculated by dividing the number of empty bags by the amount of milk powder that should be taken. More than 85% was defined as high compliance, 75%-85% as medium compliance, and less than 75% as low compliance.

2.3.3. Samples Collection

The follow-up timeline and specific items are shown in

Table S2. On day 0, participants went to the study site for baseline measurements: 5ml blood and 1ml saliva samples collected by trained staff. Blood sampling required fasting and water deprivation after 10 p.m. the previous day. Before collecting saliva, participants were required to rinse their mouths thoroughly three times with purified water and collect 1-2 ml of saliva through a saliva collection tube. Once collected, it is placed in a transfer box with an ice pack and transferred to the laboratory. The saliva sample was centrifuged at 4 ℃ for 15 min (3000 rpm/min), the supernatant was collected, and if precipitates formed during storage, centrifuged again. After centrifugation, the supernatant was divided into EP tubes and placed in a low temperature refrigerator at -80℃ for freezing test. Blood samples were transported to professional institutions at 4℃ for testing. After sample collection, participants underwent a physical examination and questionnaire, and started a 90-day supplement/placebo regimen. They were also given an intervention diary to record any illnesses and supplement use during the intervention.

2.3.4. Biomarkers Analysis

After preliminary experiments, it was determined that the dilution ratio of the saliva sample was 10, 000 times. Cayman’s Human IgA ELISA kit was used to detect the concentration of sIgA in saliva. ELISA experiments including the reagent preparation, sample, incubation, elution, test, carried out in accordance with the manual steps.

Blood samples were sent to professional testing institutions to test blood routine (peripheral blood immune cells), immunoglobulin and other indicators.

2.3.5. IPAQ-LF (International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Long Form)

The Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Long Form (IPAQ-LF) was used to investigate the physical activity of the participants in four aspects: (1) work, (2) housework, (3) transportation and (4) leisure and entertainment. Studies have shown that IPAQ is an effective tool for measuring physical activity in adults, including older adults [

22,

23,

24]. Metabolic equivalent of energy (MET) is the multiple of the metabolic rate during exercise over the metabolic rate at rest, and is a unit of exercise intensity. The metabolic equivalent minutes per week (MET-min/wk) = MET assignment corresponding to the physical activity (

Table S3) × weekly frequency (days) × time per day (min), and then the physical activity level was classified into low, moderate and high levels according to the IPAQ physical activity level grouping criteria

Table S4).

2.3.6. FFQ (Food Frequency Questionnaire)

Food Frequency questionnaire is a tool used to assess an individual’s eating habits. It obtains quantitative data on dietary intake by asking respondents how often and how much of various foods they have consumed over a certain period of time, usually in the past month or year. Its main contents include three elements: food list, food frequency and portion size. Then, the daily intake of a nutrient in a food is calculated using the formula “average daily intake frequency of food × each intake × content of a nutrient”, and then the calculated values of all food items are added together to get the average daily intake of a nutrient.

2.4. Quality Control

Some quality control measures were taken in this study. Randomized control can reduce the influence of confounding factors and balance the differences between the two groups. The experimental design ensures double-blind and randomization. Before the start of the field investigation, the project staff were regularly trained, including volunteer recruitment training, sample collection training, questionnaire survey training and other aspects, to ensure the standardization of staff technology and the orderly coordination of the site. Before the start of the trial, we established some wechat groups, communicated with the participants at any time during the intervention, and regularly reminded them to take milk powder on time every day. Empty bags were counted at each follow-up for quality monitoring.

2.5. Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The program was fully approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine (SZEFYIEC-KYPJ-2023013, 06/06/2023). The study protocol was registered at Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (https: //

www.chictr.org.cn; ChiCTR-ID: ChiCTR2400079567). In order to effectively ensure the rights and interests of the subjects, the project team purchased project insurance for all subjects (Sunshine Insurance Group, policy number: 101691372023000006). Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 18.0 software was used for statistical analyzes. Graphpad prism 9.5.0 was used for graphs. Kolmogorov -Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of data. The data of non-normal distribution is expressed as the Median (IQR (Q1, Q3)), and the data of normal distribution is expressed as the Mean (SD). Categorical variables are presented as counts (%). Within group change (change from baseline) based on paired T-test or Wilcoxon singed rank test or Friedman test, and between groups difference based on analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) or Chi-square statistics. The level of significance was set at P = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Compliance Analysis in Following Up

Compliance was measured according to the method in 2.3.2. There was no significant difference in the compliance of the three follow-up visits between the two groups (

P > 0.05). The compliance is shown in

Table S5.

3.2. Participants’ Characteristics

Among the 188 participants, the mean age was 65.25±6.46 years, of which 33.5% were males and 66.5% were females. And 31.4% of the participants had tertiary education or above, 53.7% had secondary/technical secondary education and 14.9% had primary education or below. Most of the participants lived with family members (87.2%). Most of the living environments are buildings with elevators, accounting for 85.6%. There was no statistical difference in the above general demographic characteristics between the two groups. Baseline information for 188 participants is shown in the

Table 1.

3.3. Health-Related Indicators

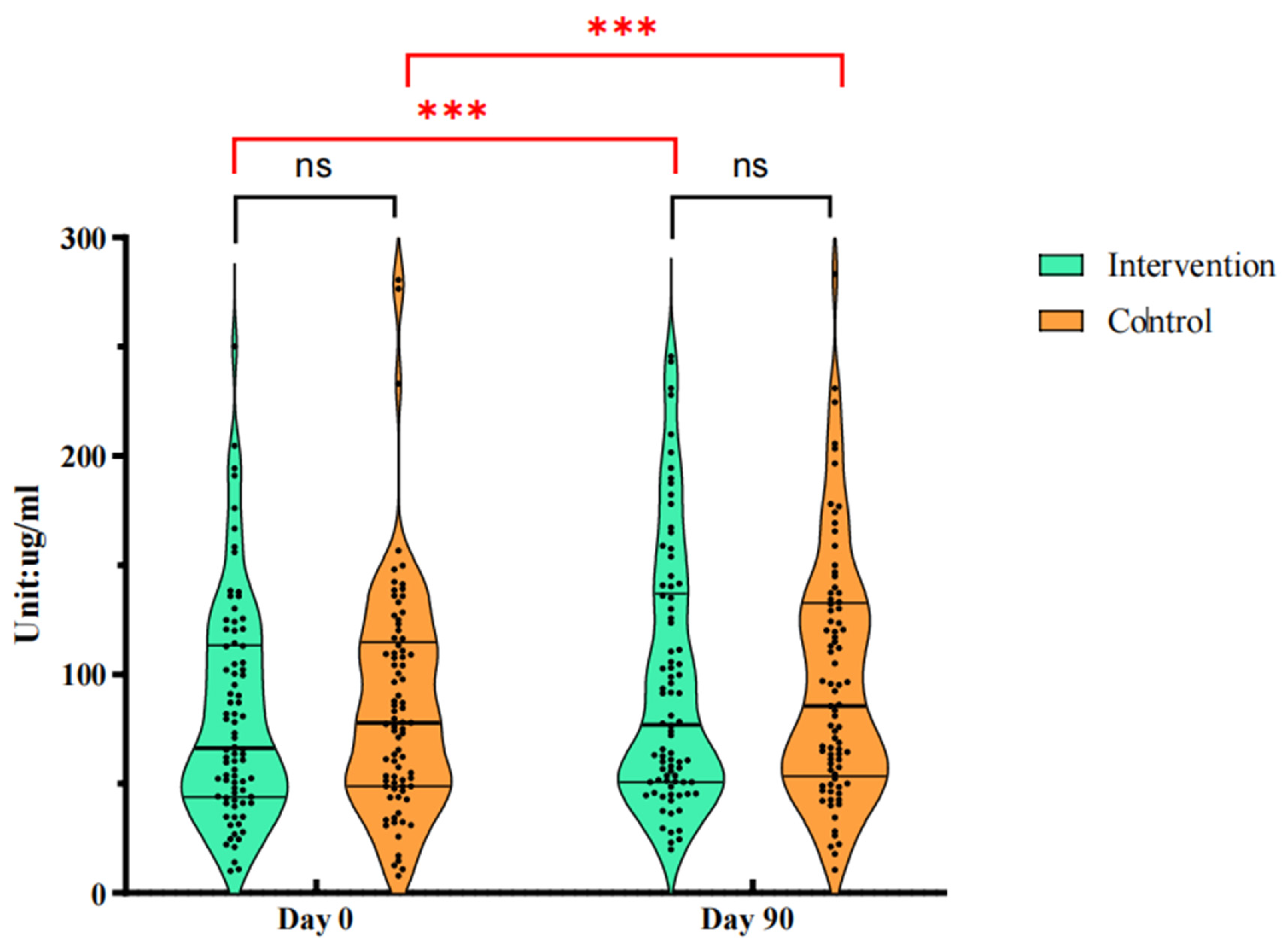

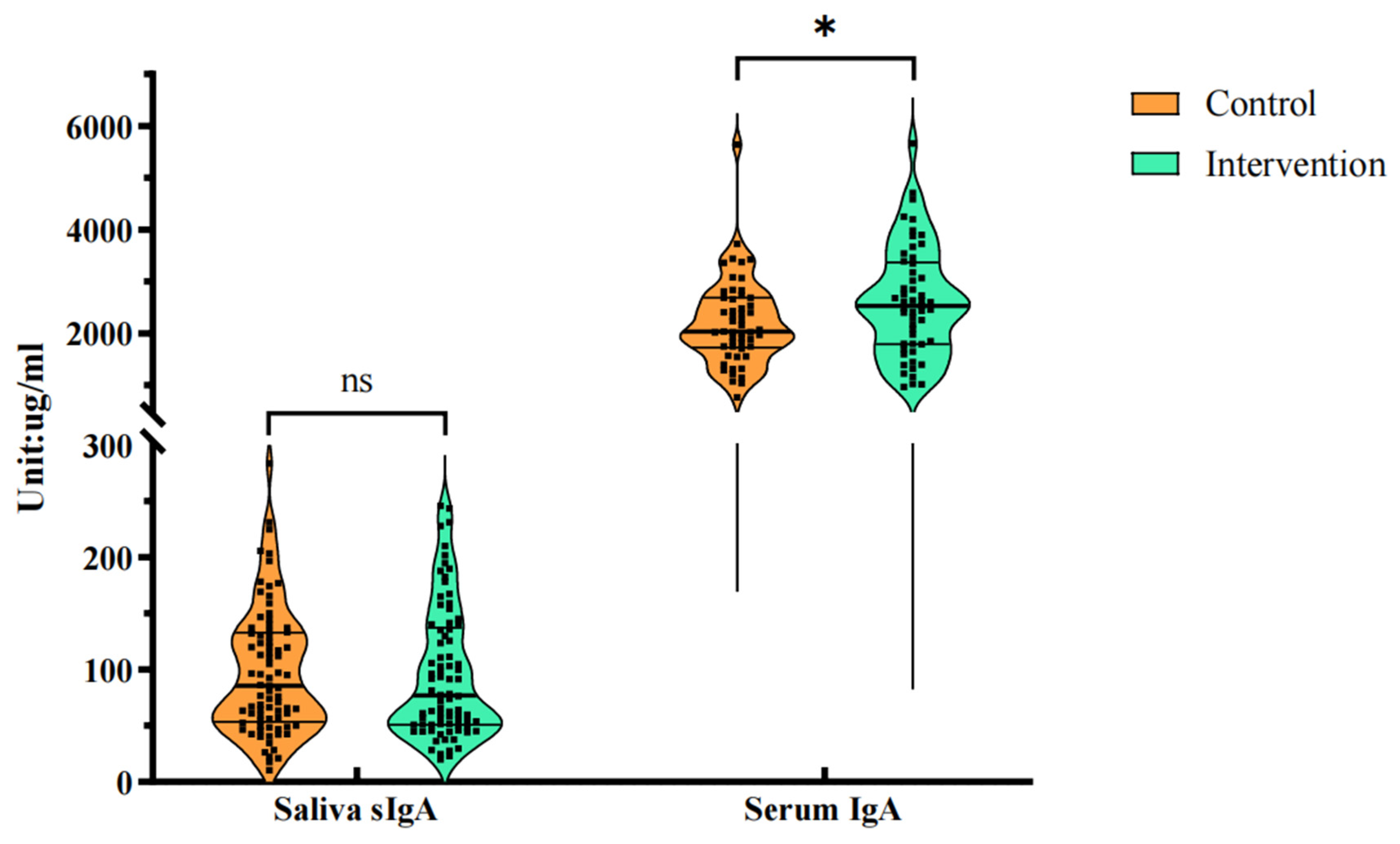

3.3.1. Saliva sIgA Levels

There was no difference in saliva sIgA concentration between the BC supplement group and the control group at baseline (M (Q1, Q3), 66.25 (43.90, 113.32) μg/ml vs. 77.81 (48.78, 114.80) μg/ml,

P = 0.495). On the 90th day of intervention, the saliva sIgA concentration increased in both groups (

P < 0.001). Group analysis showed that the saliva sIgA concentration pair in the BC supplement group increased to 76.88 (50.70, 136.98) μg/ml, and that in the control group increased to 85.54 (53.31, 132.66) μg/ml. The improvement effect of BC supplement group was more obvious, but there was no significant difference between the two groups (

P = 0.442). The changes of saliva sIgA concentration in the two groups were shown in

Figure 2.

When the age of the participants was divided into two groups at the cutoff age of 65 years, saliva sIgA levels were found to be lower in the 65 and older age group but the difference was not significant (

P > 0.05), and increased after the intervention, to a lesser extent than in those under 65 years. This was the case in both groups.

Table 2 shows the results according to age group.

3.3.2. Immune-Related Factors in Serum

The serum samples of some subjects were taken for C-reactive protein (CRP) and immunoglobulin (IgA, IgG, IgM) indicators measurement. The level of serum IgA in the BC supplement group was significantly higher than that in the regular milk powder group (

P = 0.046) after intervention, indicating that BC supplement may have a greater impact on serum IgA than the regular milk powder. The specific values are shown in

Table 3.

Figure 3 is the comparison of saliva sIgA and serum IgA levels after intervention.

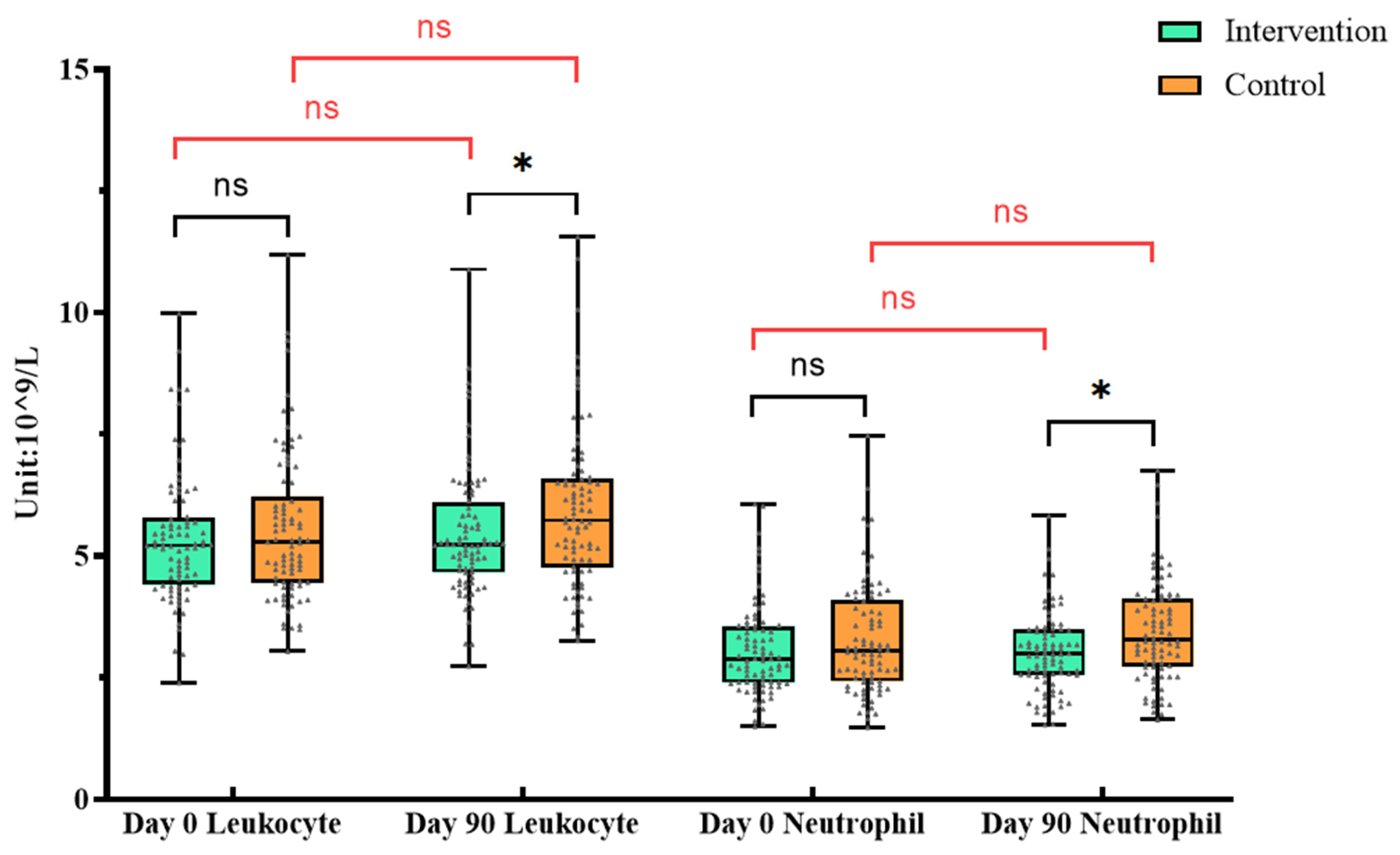

3.3.3. Immune Cells in Peripheral Blood

There was no difference between the BC supplement group and the control group at baseline (

P > 0.05). After the intervention, the two groups were analyzed separately. The results showed that the lymphocytes, monocytes and platelets of the intervention group increased, while the erythrocyte and hemoglobin decreased (

P<0.05). In the control group, leukocyte, monocytes, eosinophils and platelets increased, and the erythrocyte and hemoglobin decreased (

P<0.05) (

Table 4).

ANCOVA was used to compare the two groups after adjusting the baseline levels, and the results showed that there were differences in leukocyte and neutrophil between the two groups after intervention (P < 0.05). These changes may require further research to determine its specific biological significance.

Figure 4.

Changes of leukocyte and neutrophil in routine blood test. * In

Figure 4, orange is the control group and green is the intervention group. “ns”represents

P >0. 05; “*”represents

P <0. 05. The significance in black indicates the difference between the two groups at the same time, and the red indicates the difference within the group at different times.

Figure 4.

Changes of leukocyte and neutrophil in routine blood test. * In

Figure 4, orange is the control group and green is the intervention group. “ns”represents

P >0. 05; “*”represents

P <0. 05. The significance in black indicates the difference between the two groups at the same time, and the red indicates the difference within the group at different times.

3.3.4. Self-Reported Health Status

Chi-square statistics was used to analyze the indicators of self-reported health status. The prevalence of chronic diseases at baseline was analyzed in (

Table S6). There were no significant differences in self-reported health status between the BC supplement group and the control group at baseline (

P > 0.05). The results of the 56th and 90th day follow-up showed that there were no statistical differences in the self-reported health status between two groups (

P > 0.05). Exceptionally, participants in the control group had an increase in the number of colds during the intervention (

P = 0.004), whereas this index did not change in the intervention group (

P > 0.05) (

Table S7). In addition, on day 0, 19.68% of the participants reported oral ulcers. On day 56, the rate of oral ulcers was 14.04%, and on day 90, the rate decreased to 8.78%. Compared with day 0 and day 56, the incidence of oral ulcer in BC supplement group decreased significantly on day 90 (

P < 0.05), while the change in control group was not significant (

P > 0.05), which indicated that BC supplement was beneficial to improve the condition of oral ulcer. The changes of self-reported oral ulcers in each group within 90 days are shown in

Table 5.

3.3.5. FFQ

Participants’ average daily nutrient intake was assessed using FFQ (

Table S8). In general, there was no statistically significant difference in the intake of major nutrients (Protein, Fat, Vitamin (A, C, D, E), Minerals, Folate) between the two groups (

P >0.05), indicating that there were no significant differences in dietary habits and the groups were comparable.

3.3.6. Physical Activity Levels (IPAQ-LF)

Physical activity levels were measured with IPAQ-LF at baseline and after the intervention. There were 149 participants met the inclusion criteria after questionnaire screening. At baseline, the (M, (Q1, Q3)) of total metabolic equivalent minutes per week (MET-min/wk) were 5166.0 (3205.5, 7976.25) in the intervention group and 5097.0 (2822.0, 6552.0) in the control group. After the physical activity level was divided into three levels according to the standard, there was no difference in the physical activity level between the two groups at baseline (

P = 0.239). IPAQ was measured again after the intervention, and the results showed that total MET-min/wk in intervention group vs. control group was 4935.0 (3638.3, 7659.0) vs. 4473.0 (2646.0, 7938.0), and the difference between groups was still not significant (

P = 0.796). IPAQ outcomes are shown in

Table S9.

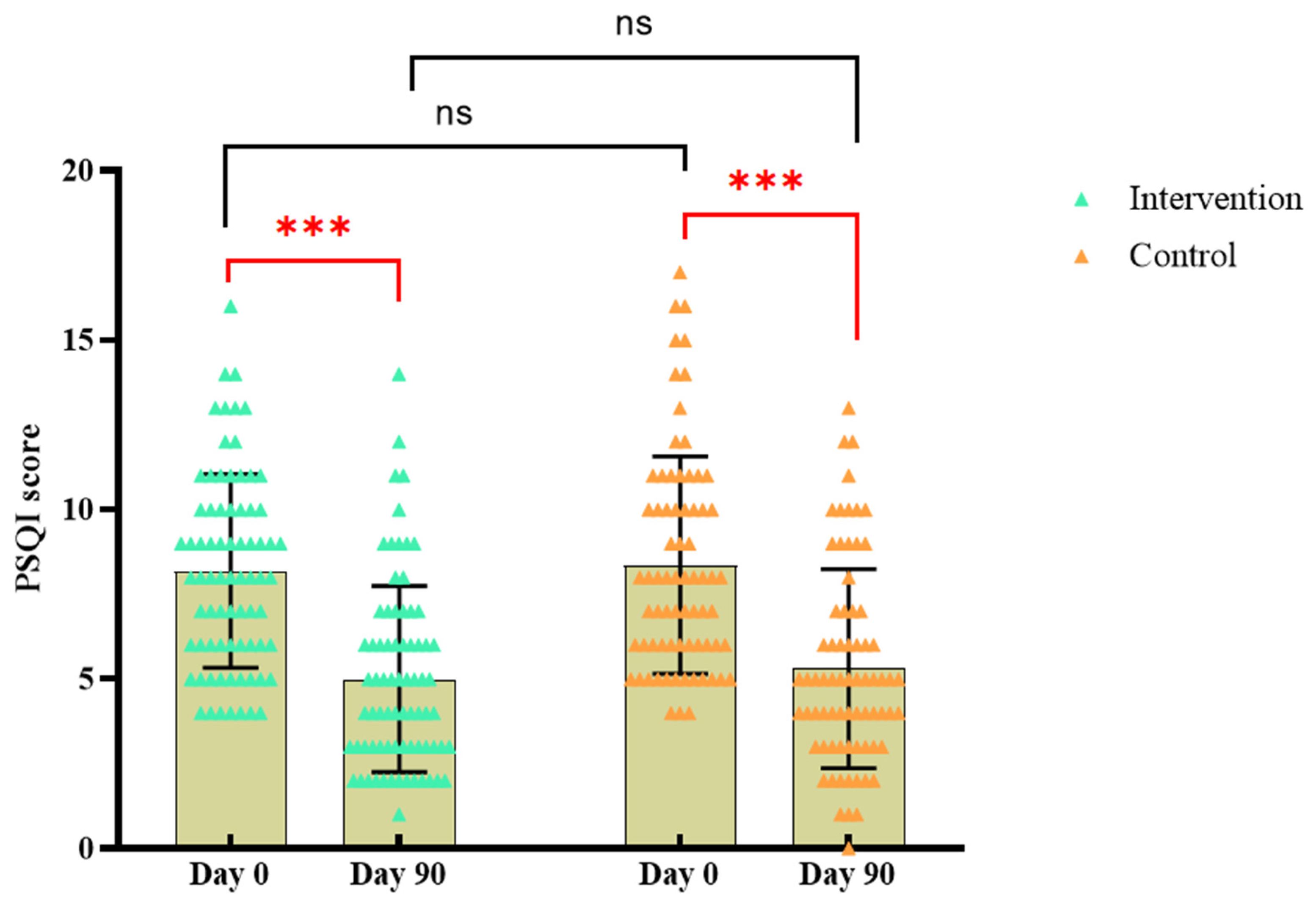

3.3.7. Sleep Quality in PSQI

At baseline, PSQI score was 8.11±2.89 in the BC supplement group while 8.43±3.17 in the control group, and there was no significant difference in sleep quality between the two groups (P > 0.05). After 90 days of intervention, the PSQI sleep quality index score of the BC supplement group was 5.01±2.80, slightly lower than that of the control group (5.28±2.88), but there was no significant difference (P > 0.05). The score of the BC supplement group decreased by 3.10±2.96, while the control group decreased by 3.15±2.47. Compared to baseline, sleep quality improved in both groups after the intervention (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Changes in PSQI scores in each group.* In

Figure 5, orange is the control group and green is the intervention group. “***”represents

P <0. 001; “ns”represents

P >0. 05; The significance in black indicates the difference between the two groups at the same time, and the red indicates the difference within the group at different times.

Figure 5.

Changes in PSQI scores in each group.* In

Figure 5, orange is the control group and green is the intervention group. “***”represents

P <0. 001; “ns”represents

P >0. 05; The significance in black indicates the difference between the two groups at the same time, and the red indicates the difference within the group at different times.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of BC supplementation on sIgA and health status in middle-aged and elderly people. As the first barrier of human immunity, mucosal immunity plays a very important role in preventing exogenous infection. The lack of antibodies on the mucosal surface may make the body more susceptible to viral and bacterial infections. sIgA is the main antibody in mucosal local immunity and is the first line of defense against respiratory infections such as pneumonia and influenza [

25]. Our current results showed that after 90-day of intervention, the concentration of sIgA in the participants’ saliva in both groups was significantly increased, possibly indicating improved immune system activity. Compared with regular milk powder, the improvement trend of saliva sIgA level in BC supplement group was more obvious (the median difference is even larger), although the difference was not statistically significant. This may be due to the abundant bioactive molecules in bovine colostrum, including immunoglobulins, growth factors and cytokines [

19,

26]. A study by Crooks et al. showed that consuming 10 grams of bovine colostrum per day for 12 weeks significantly increased sIgA concentration compared to skimmed milk [

18].The results of the study by Mero et al. showed that compared with the placebo control group supplemented with maltodextrin, the concentration of sIgA in the bovine colostrum supplement group increased by 33% [

27], which was similar to the results in this study, except that the control group in this study was regular milk powder with more nutrients.

In addition to changes in salivary sIgA concentrations, the results showed that serum IgA in the BC supplement group was significantly higher than that in the regular milk powder group after intervention, possibly indicating that BC supplements had a greater effect on IgA in serum than regular milk powder, while the difference between two groups in Saliva sIgA was not significant. This may be because although method teaching and quality control were carried out at the time of saliva collection, individual oral differences and other conditions could not be excluded. For example, the time and conditions of sample collection, the changes of salivary sIgA at different times, and environmental factors such as temperature, humidity and air pressure in the experimental environment may all affect the experimental results. However, compared with saliva, serum may be more stable and objective.

Furthermore, although the incidence of oral ulcers did not differ significantly between groups, the intra-group analysis showed that the incidence of oral ulcers decreased significantly in the BC supplement group, while this trend was not significant in the control group, which may indicate that intake of BC supplements can reduce oral inflammation and improve oral health. Results of previous trials on chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicity of bovine colostrum in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia [

28,

29] suggested that ingestion of bovine colostrum during treatment had a protective effect on the oral mucosa and reduced the severity of oral mucositis, similar to the results of this study. Participants in the control group had more colds with the intervention, possibly because of changes in the weather. Because the trial started in August and ended in November, which happened to be the change from autumn to winter. However, the fact that the number of colds did not change in the BC supplement group, possibly implying increased resistance among participants in this group. In addition, the PSQI scores of the participants were significantly lower after 90 days of intervention, indicating that milk powder supplementation had a significant positive effect on improving sleep quality and could be further studied.

However, it is not clear which components of the milk powder are playing a role. The intervention group in this study was BC supplement powder, while the control group was regular milk powder. BC supplement powder contained specific bovine colostrum, whey protein and probiotics, while regular milk powder did not contain these ingredients. The results of the study showed that both milk powders improved health to varying degrees. So we’re not sure exactly which ingredient is responsible for the positive effect. It may be micronutrients, such as vitamins A, C, D, E, etc. in milk powder. A complex integrated immune system requires a variety of specific micronutrients [

30], including vitamins A, D, C, E, B6 and B12, folate, zinc, iron, copper and selenium, among others, which play a vital role in every stage of the immune response, especially vitamins C and D [

31]. There is evidence that vitamin D may play a role in age-related diseases [

32,

33]. Supplementation of complex combinations of micronutrients in the elderly can increase the number of different types of immune cells [

34], and studies have shown that the intake of multivitamin and mineral supplements has an impact on immune function in healthy elderly people [

35]. Vitamin and mineral supplements can improve the nutrition and health status of the elderly [

36,

37]. Therefore, further research is needed to confirm exactly what components play a key role.

There may be some limitations to this study. First, no significant differences in demographic characteristics were found in the baseline, but due to the natural differences among individual subjects, such as differences in immune system, genes, etc., there may be different responses to milk powder supplementation. When age was taken as a continuous variable, no significant difference was observed between the two groups. When the age was divided into 65 years old and below and 65 years old, it was observed that the participants in the BC supplement group were older, although the difference between two groups was still not significant, which may have some impact on the test results. Second, during the study period, in addition to the intervention of milk powder, there may be other factors affecting immunity and health status, and the interference of these factors may affect the interpretation of the results. In addition, it was not possible to control whether participants had received other health care measures during the trial that might have interfered with the effects of milk powder, although they were required at the time of signing the informed consent. The use of mouthwashes and the like may also have some confounding effects [

38]. Finally, due to the complexity and uncertainty of the intervention trial process, there may be other confounding factors that are not considered.

5. Conclusions

The results of the study suggest that BC supplement powder intervention for 90 days may provide beneficial health effects in middle-aged and elderly people and promote healthy aging. The differences in the effects of BC supplement powder and ordinary milk powder on salivary sIgA levels need to be further studied.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1 Comparison of ingredients between BC supplement powder and regular milk powder; Table S2 Study Site Follow up Schedule; Table S3 MET of different types of physical activity in IPAQ-LF; Table S4 Standards for Grouping Individual Physical Activity Levels; Table S5 Comparison of compliance at three follow-up visits (%); Table S6 Self-reported prevalence of chronic diseases (%); Table S7 Changes in self-reported health status during the intervention period (%); Table S8 Participants’ average daily nutrient intake; Table S9 Physical activity profile of the two groups in IPAQ (%).

Author Contributions

Xufeng Wang: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Resources, and Reviewing Visualization. Jialu Wang: Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Data analysis, Writing—Review & Editing. Xiaobo Zhou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software. Yubo Zhao: Investigation, Data Curation. Xingru Zhang: Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization. Xiaomin Sun: Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Validation. Ruijie Xu: Writing—Review & Editing, Methodology. Tianxiao Zhang: Software, Validation. Sidi Zhao: Data Curation. Tianxiao Chen: Data Curation. Qian Wu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Review & Editing, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Youfa Wang: Conceptualization, Review & Editing, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This research was funded by Heilongjiang Feihe Dairy Co., Ltd. (grant number: 20230533). The sponsor did not play any role in the design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki regarding experiments with human beings. The program was fully approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine (SZEFYIEC-KYPJ-2023013, 06/06/2023), and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (https: //

www.chictr.org.cn; ChiCTR-ID: ChiCTR2400079567).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be requested from the principal author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to China Feihe Co., Ltd. for their support in this work. We extend our appreciation to the Professor Xin Bao’s team from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine for their valuable assistance in data collection. We are also thankful to Ye Liu, Yifan Gou, Haodan Zhang, and Fengshuo Liu et al. colleagues for their diligent efforts in data collection. Thanks to Ronghua Elderly Care Institution for providing support to the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. There is no interest relationship between this research and China Feihe Co., Ltd.

References

- NIKOLICH-ZUGICH, J. The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system [J]. Nat Immunol, 2018, 19 (1): 10-9.

- Connors, J.; Haddad, E.K.; Petrovas, C. Aging alters immune responses to vaccines. Aging 2021, 13, 1568–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.M.; Reginster, J.Y.; Rizzoli, R.; Shaw, S.C.; Kanis, J.A.; Bautmans, I.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; Bruyère, O.; Cesari, M.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; et al. Does nutrition play a role in the prevention and management of sarcopenia? Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathe, M.; Müller, K.; Sangild, P.T.; Husby, S. Clinical applications of bovine colostrum therapy: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Playford, R.J.; Weiser, M.J. Bovine Colostrum: Its Constituents and Uses. Nutrients 2021, 13, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokaev, S.; Krasnova, I.S.; Korobeĭnikova, T.V. [Composition and clinical use of bovine colostrums].. 2012, 81, 35–40.

- MCGRATH B A, FOX P F, MCSWEENEY P L H, et al. Composition and properties of bovine colostrum: a review. Dairy Science & Technology, 2016, 96 (2): 133-58.

- BLAIR M, KELLOW N J, DORDEVIC A L, et al. Health Benefits of Whey or Colostrum Supplementation in Adults >/=35 Years; a Systematic Review. Nutrients, 2020, 12 (2).

- Pérez-Cano, F.J.; Marín-Gallén, S.; Castell, M.; Rodríguez-Palmero, M.; Rivero, M.; Franch. ; Castellote, C. Bovine whey protein concentrate supplementation modulates maturation of immune system in suckling rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, S80–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CESARONE M R, BELCARO G, DI RENZO A, et al. Prevention of influenza episodes with colostrum compared with vaccination in healthy and high-risk cardiovascular subjects: the epidemiologic study in San Valentino. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost, 2007, 13 (2): 130-6.

- Patel, K.; Rana, R. Pedimune in recurrent respiratory infection and diarrhoea—The Indian experience—The PRIDE study. Indian J. Pediatr. 2006, 73, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAAD K, ABO-ELELA M G M, EL-BASEER K A A, et al. Effects of bovine colostrum on recurrent respiratory tract infections and diarrhea in children. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95 (37): e4560.

- Nederend, M.; van Stigt, A.H.; Jansen, J.H.M.; Jacobino, S.R.; Brugman, S.; de Haan, C.A.M.; Bont, L.J.; van Neerven, R.J.J.; Leusen, J.H.W. Bovine IgG Prevents Experimental Infection With RSV and Facilitates Human T Cell Responses to RSV. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.W.; March, D.S.; Curtis, F.; Bridle, C. Bovine colostrum supplementation and upper respiratory symptoms during exercise training: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabilitation 2016, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, L.; Chen, T. The Effects of Secretory IgA in the Mucosal Immune System. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 2032057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantis, N.J.; Rol, N.; Corthésy, B. Secretory IgA's complex roles in immunity and mucosal homeostasis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corthésy, B. Multi-Faceted Functions of Secretory IgA at Mucosal Surfaces. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooks, C.V.; Wall, C.R.; Cross, M.L.; Rutherfurd-Markwick, K.J. The Effect of Bovine Colostrum Supplementation on Salivary IgA in Distance Runners. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2006, 16, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ooi, T.C.; Ahmad, A.; Rajab, N.F.; Sharif, R. The Effects of 12 Weeks Colostrum Milk Supplementation on the Expression Levels of Pro-Inflammatory Mediators and Metabolic Changes among Older Adults: Findings from the Biomarkers and Untargeted Metabolomic Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guberti, M.; Botti, S.; Capuzzo, M.T.; Nardozi, S.; Fusco, A.; Cera, A.; Dugo, L.; Piredda, M.G.; De Marinis, M. Bovine Colostrum Applications in Sick and Healthy People: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FOKKENS W J, LUND V J, HOPKINS C, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology, 2020, 58 (Suppl S29): 1-464.

- Cleland, C.; Ferguson, S.; Ellis, G.; Hunter, R.F. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) for assessing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour of older adults in the United Kingdom. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Barnett, A.; Cheung, M.-C.; Sit, C.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Chan, W.-M. Reliability and Validity of the IPAQ-L in a Sample of Hong Kong Urban Older Adults: Does Neighborhood of Residence Matter? J. Aging Phys. Act. 2012, 20, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Holle, V.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Van Dyck, D. Assessment of physical activity in older Belgian adults: validity and reliability of an adapted interview version of the long International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-L). BMC Public Heal. 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo, A.; Maccari, G.; Camussi, G. mRNA Technology and Mucosal Immunization. Vaccines 2024, 12, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, A.; Kaplan, M.; Duman, H.; Bayraktar, A.; Ertürk, M.; Henrick, B.M.; Frese, S.A.; Karav, S. Bovine Colostrum and Its Potential for Human Health and Nutrition. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mero, A.; Kähkönen, J.; Nykänen, T.; Parviainen, T.; Jokinen, I.; Takala, T.; Nikula, T.; Rasi, S.; Leppäluoto, J. IGF-I, IgA, and IgG responses to bovine colostrum supplementation during training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RATHE M, DE PIETRI S, WEHNER P S, et al. Bovine Colostrum Against Chemotherapy-Induced Gastrointestinal Toxicity in Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2020, 44 (2): 337-47.

- Hajihashemi, P.; Haghighatdoost, F.; Kassaian, N.; Khorasani, M.R.; Hoveida, L.; Nili, H.; Tamizifar, B.; Adibi, P. Therapeutics effects of bovine colostrum applications on gastrointestinal diseases: a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HIGH K, P. Micronutrient supplementation and immune function in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis, 1999, 28 (4): 717-22.

- Maggini, S.; Pierre, A.; Calder, P.C. Immune Function and Micronutrient Requirements Change over the Life Course. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, M.; Penckofer, S. The Role of Vitamin D in the Aging Adult. J. Aging Gerontol. 2014, 2, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HAYES D, P. Vitamin D and ageing. Biogerontology, 2010, 11 (1): 1-16.

- ABIRI B, VAFA M. Micronutrients that Affect Immunosenescence. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2020, 1260: 13-31.

- Fantacone, M.L.; Lowry, M.B.; Uesugi, S.L.; Michels, A.J.; Choi, J.; Leonard, S.W.; Gombart, S.K.; Gombart, J.S.; Bobe, G.; Gombart, A.F. The Effect of a Multivitamin and Mineral Supplement on Immune Function in Healthy Older Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Johnson, M.A.; Fischer, J.G. Vitamin and Mineral Supplements: Barriers and Challenges for Older Adults. J. Nutr. Elder. 2008, 27, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIGH K, P. Nutritional strategies to boost immunity and prevent infection in elderly individuals. Clin Infect Dis, 2001, 33 (11): 1892-900.

- KRUPA N C, THIPPESWAMY H M, CHANDRASHEKAR B R. Antimicrobial efficacy of Xylitol, Probiotic and Chlorhexidine mouth rinses among children and elderly population at high risk for dental caries—A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Prev Med Hyg, 2022, 63 (2): E282-E7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).