1. Introduction

Root canal irrigation aims to completely clean the complex root canal system of remaining vital or necrotic pulp tissue, bacterial biofilms, infected debris, and smear layers [

1] to provide conditions for initiating the healing of periapical lesions [

2]. The efficacy of irrigation depends on the antimicrobial properties of the irrigant, its ability to safely reach the deepest part of the root canal, and the intracanal complexities in which bacterial biofilms are firmly attached to dentinal walls. Therefore, ensuring a sufficient irrigant flow rate and dynamic irrigant exchange in the deepest part of the root canal is essential [

3].

Syringe needle irrigation (SNI) is the most common technique in which a needle is positioned stationary in the root canal during irrigant delivery. The efficacy of SNI depends on the depth of the needle placed in the root canal, the available space in the apical third, and the irrigant flow rate [

3,

4,

5]. Although SNI is generally effective for simple root canal morphologies [

3], it faces significant limitations in complex intracanal anatomies. The primary issues are inadequate hydrodynamic turbulence, which impede the effective penetration of the irrigant and fails to provide sufficient chemo-mechanical cleaning [

5,

6]. As a result, bacteria and infected debris may persist in challenging areas such as isthmuses, lateral canals, and apical thirds [

7,

8]. Therefore, various activated irrigation techniques have been recommended and studied.

Laser-activated irrigation (LAI) is an excellent choice for improving root canal cleaning and disinfection, showing excellent results in debris and smear layer removal [

9], vital pulp removal [

10], and biofilm removal [

11,

12]. Irrigants within the root canal system absorb Er:YAG laser wavelengths, producing powerful interactions at very low energies. The cleaning mechanism of LAI is based on optic cavitation and high fluid speed in the irrigant caused by the expansion and implosion of laser-induced bubbles created at the tip of the laser fiber [

13,

14]. In the conventional LAI approach, the laser fiber tip (FT) is positioned inside the canal approximately 5 mm from the apical foramen, and the pulse energies are >30 mJ and up to 250 mJ [

14]. On the other hand, photon-induced photoacoustic streaming (PIPS), is characterized by a conical laser tip positioned in the pulp chamber, a lower pulse energy of 20 mJ, and a super short pulse (SSP) duration (50 µs). This approach creates fast vertical fluid movement throughout the root canal, especially in the apical region, resulting in biofilm detachment and coronal displacement [

15,

16,

17].

The shock wave-enhanced emission photoacoustic streaming (SWEEPS) modality of the Er:YAG laser has been introduced to enhance the cavitation effect in the constrained space of the root canal. The specificity of the SWEEPS modality is that the Er:YAG laser emits pairs of pulses, accelerating the primary bubble’s collapse by forming a second bubble. As the second bubble grows, the additional pressure causes the first bubble to collapse, emitting primary and secondary shock waves deeper within the endodontic space [

18]. Furthermore, the pulse duration in the SWEEPS modality is twice that of the SSP modality (25 µs), doubling the peak power of the pulse. Given the much stronger pulses, the safety of SWEEPS regarding irrigant extrusion has been justifiably questioned. The SSP mode of Er:YAG LAI is safer than SNI [

19] and causes less postoperative pain after primary root canal treatment compared with ultrasonic-activated irrigation [

20]. Furthermore, Jezeršek et al. [22] reported that the SSP and AutoSWEEPS modes caused less extrusion, regardless of the laser energy than open-ended SNI. However, the pressure along the depth of the root canal appears to depend on the laser modality and FT design [23]. FTs for SSP and AutoSWEEPS LAI are rigid and can be conical, radial, or flat-ended, resulting in different laser energy emission patterns [

17,24]. Burklein et al. [24] concluded that FT design might influence the cleaning efficacy of LAI, and their effectiveness in root canal treatment is still being investigated [

10,

17]. However, it is still unclear which FT should be used for SSP and SWEEPS modes, considering the safety of application without irrigant extrusion.

The present study aimed to evaluate and compare apical irrigant extrusion during the SSP and AutoSWEEPS modes of Er:YAG LAI using three different FTs: PIPS FT, radial conical FT, and SWEEPS sapphire conical FT. The null hypotheses were that there were no differences (a) in the amount of extruded irrigant between the SSP and AutoSWEEPS modes of Er:YAF LAI and (b) between different FTs regardless of the mode used.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection and Preparation

Vidas et al. [

19] described the model used in this study for measuring irrigant extrusion.

Twenty human maxillary central incisors, extracted for periodontal reasons, were collected and stored in 3% NaOCl until the time of the experiment. The root canal morphology was verified radiographically and with cone beam computed tomography scanning (Cranex 3DX; Soredex, Tuusula, Finland) using the following parameters: field of view, 5 9 5 (5.0 mm) mm; ENDO, 85 µm; 6.3 mA; 90 kV; and 8.7 s. Samples with any of the following parameters were excluded: root fracture, incomplete apexogenesis, signs of internal or external resorption, calcification, or lateral canals.

After creating the access cavities, the working length was standardized to 20 mm by decoronating the excess tooth structure while maintaining a fully accessible cavity. Root canal instrumentation was performed using a reciprocating instrument, Reciproc® R40 (0.06/variable taper; VDW Dental, München, Germany). During instrumentation, 5 ml of 3% NaOCl was used. The patency of the root canal was checked with an ISO K-file #10. After root canal preparation, the prepared samples were sterilized in an autoclave (15 min, 121°C, 20 psi).

Each sample was embedded in an acrylic mold in the middle part of the root, and the root tip was attached to a 10 mm-long drainage tube (Discofix Cluer lock, B. Braun Melsungen AG 34209 Melsungen, Germany). This attachment was double sealed with flowable composite (Gaenial Universal Injectable, GC, Tokyo, Japan) and wax to prevent premature leakage of the irrigant. The prepared teeth were positioned horizontally on the system. A supplier needle (27 G open-notched, DiaDent; Netherland) was connected to the syringe mounted on a precision syringe pump (Aladdin, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) to ensure accurate irrigant volumetric flow (IVF). The apically extruded irrigant was collected and weighed (g) using a microbalance (TW423L, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan), after which the mass of the measuring cup was subtracted [

19].

2.2. Irrigation Protocols and Extruded Irrigant Measurements

In group 1 (control group), root canal irrigation was performed using SNI with a 27-G needle (Appli-Vac; Vista Dental, WI, USA) placed in the access cavity at the previously determined level, and 3% NaOCl was used at an IVF rate of 0.05 ml/s. The protruded irrigant was collected into a mensure and weighed (g), subtracting the weight of the mensure using a microbalance (TW423L, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). Before each sampling, the mensure was completely dried.

The sequence of irrigation procedures for each sample was assigned using randomization software (random.org). Each tooth served as its own negative control by measuring the irrigant extrusion during passive irrigation with the supplier needle placed in the access cavity. The samples were positioned horizontally so that the influence of gravitation on extrusion could be avoided.

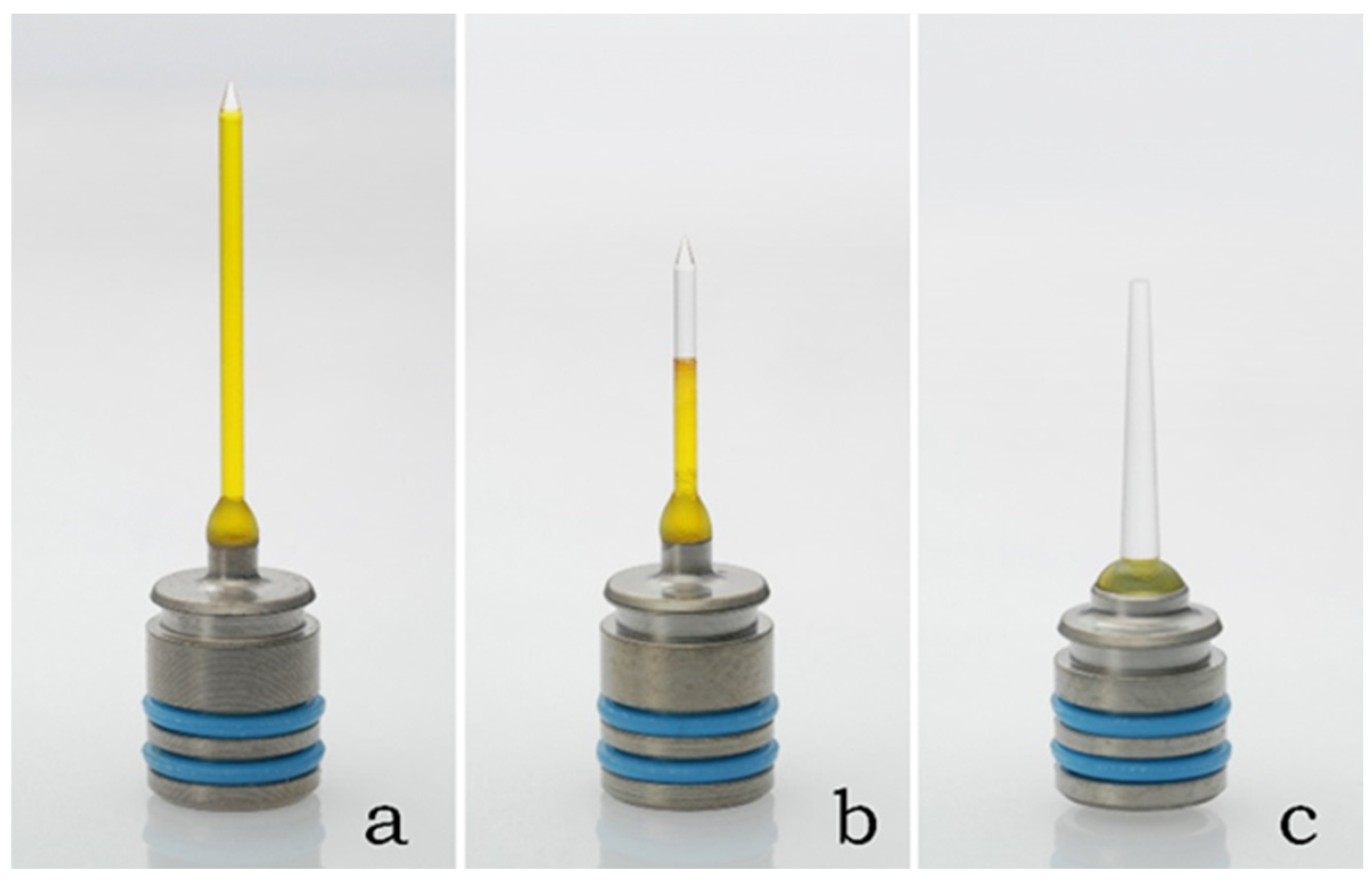

In six other groups (G2-G7) (

Table 1), LAI was performed using the Er:YAG laser with a wavelength of 2940 nm (Lightwalker AT, Fotona, Ljubljana, Slovenia) in two laser modes: in G2-G4, the SSP mode (20 mJ, 15 Hz, pulse duration 50 μs); in G5-G7, the Auto SWEEPS mode (20 mJ, 15 Hz, pulse duration 25 μs, temporal separation between pulses varied from 300–600 μs with 10 μs steps). Three different laser tips were used for each laser mode: a radial SWEEPS (600/14, Fotona) (

Figure 1) (G2 and G5), a PIPS (600/9, Fotona) (

Figure 1) (G3 and G6), and a SWEEPS sapphire tip (

Figure 1) (600/8, Fotona) (G4 and G7). FTs were mounted on an H14-N handpiece with 90° angulation and an integrated air/water spray nozzle. During the measurement of the extruded irrigant, the water spray and air were turned off.

IVF, irrigant volumetric flow; SSP, super short pulse; SWEEPS, shock wave-enhanced emission photoacoustic streaming; PIPS, photon-induced photoacoustic streaming.

During LAI, FTs were placed in the access cavity above the root canal orifices, which had been filled with NaOCl. The central position of the FTs during LAI was controlled under magnification of 16× (M320 microscope; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), although with the AutoSWEEPS mode, the FT did not have to be positioned in the middle of the access cavity. Each irrigation procedure lasted 60 s and was repeated 10 times per tooth and procedure. A 30-s pause was made between each measurement. Before each test, the entire system was filled with the irrigant solution so that the entrapped air bubbles could be eliminated.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS 26 statistical software. The data were analyzed using Friedman’s two-way analysis of variance and Dunn’s pairwise test to identify the differences in individual groups. A significance level of 0.05 was used.

3. Results

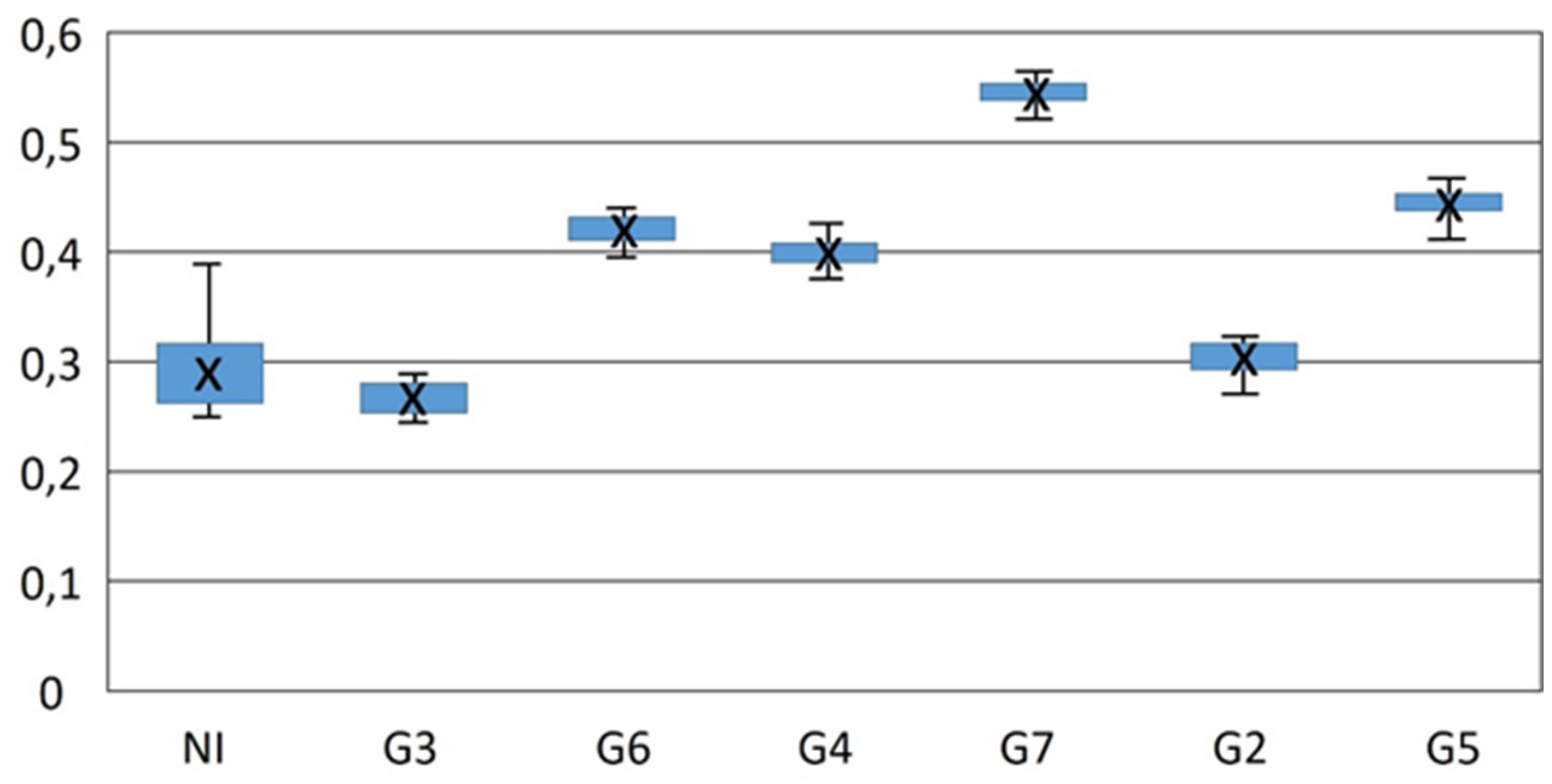

The amount of extruded irrigant is shown in

Figure 2. The volume of extruded irrigant was significantly lower in the G1 and two SSP groups (G2 and G3), than in the G4–G7 groups (p<0.05). There were no significant differences between G1 (SNI), G2 (SSP/SWEEPS radial), and G3 (SSP/PIPS) (p=0.2, p=0.464). SSP/SWEEPS FT (G4) caused NaOCl extrusion similar to AutoSWEEPS/PIPS FT (G6) (p=0.289). In the AutoSWEEPS group, all the FTs caused similar extrusion of NaOCl (p>0.05).

In the SSP groups, the greatest extrusion was found with the SWEEPS sapphire tip (0.39±0.01) (p<0.05) followed by the PIPS FT(0.26±0.01) and radial SWEEPS tips (0.30±0.01), which did not differ significantly (p>0.05). In the AutoSWEEPS group, the PIPS FT caused the least extrusion (0.41±0.01), and the SWEEPS sapphire FT caused the highest extrusion (0.54±0.01); however, no significant differences among the FTs were observed (p=0.002).

When comparing the extrusion of NaOCl with different modes but the same FTs, the SSP mode generally produced significantly less irrigant extrusion (p<0.05). Group G7 (AutoSWEEPS/SWEEPS FT) had the highest irrigant extrusion (0.54±0.01), whereas group G3 (SSP/PIPS FT) had the lowest extrusion rate (0.26±0.01).

4. Discussion

This study’s findings showed that the apical extrusion of NaOCl differed among different LAI protocols and FTs; hence, the null hypotheses (a) and (b) can be rejected. The research clearly illustrates the dependency between the type of FT used and the laser modality on the extent of irrigation extrusion on ex vivo model. The shape and size of the FT play a crucial role in influencing bubble formation during LAI [26]. Regardless of the specific LAI mode used in this research, whether SSP or AutoSWEEPS, the lowest level of extrusion was observed with the PIPS FT, while the highest extrusion was recorded with the SWEEPS sapphire FT. Although all FTs used had the same diameter, the PIPS FT (600/9) differs with its conical shape and 5 mm-long cleavage from the tip. This unique construction facilitates the formation of spherical cavitation bubbles that predominantly expand laterally rather than apically, thereby potentially reducing apical extrusion. In contrast, the gradually conical design of sapphire SWEEPS and flat FTs tends to generate channel-like bubbles that are more likely to extend apically, increasing the risk of greater apical extrusion [27]. These differences in bubble dynamics significantly influence the amount of extruded irrigant, as they directly relate to the pressure generated within the root canal during LAI.

Jezeršek et al. [23] found that the AutoSWEEPS mode generated 20–40% higher pressure in the upper two-thirds of the root canal compared to the SSP mode, while both protocols exhibited similar pressure levels in the apical third. In another study, Jezeršek et al. [22] reported that the AutoSWEEPS modality resulted in the lowest irrigant extrusion in simulated root canals compared to SSP and SNI, regardless of the laser energy used. Notably, both LAI modes, AutoSWEEPS and SSP, consistently demonstrated less irrigant extrusion than SNI. Bolhari et al. [

21] observed comparable amounts of dye extrusion when using SSP and SWEEPS during photodynamic therapy.

In the present study, the SSP mode showed a lower potential for apical extrusion compared to the AutoSWEEPS mode. Notably, both the SNI and SSP modes (when using radial SWEEPS and PIPS FT) resulted in similar levels of irrigant extrusion (

Figure 2).

The difference in mentioned findings of studies focusing on apical extrusion emphasize the importance of using human teeth samples, as the frictional resistance and fluid dynamics in biological tissues differ significantly from those in acrylic blocks. Furthermore, the access cavities in human teeth serve as a reservoir for irrigants, directly affecting extrusion of irrigant [

22,28,29]. These factors may be responsible for the discrepancies observed when comparing our results with those of other studies and emphasize the importance of realistic models for a better understanding of irrigant dynamics under clinical conditions [30]. To ensure consistency between samples and minimize variations in root canal anatomy that could influence the study results, maxillary central incisors were selected due to their straight root canals.

In the study conducted by Vatanpour et al. [29], it was observed that the SSP and AutoSWEEPS modes exhibited less extrusion compared to SNI. On contrary, in Abat et al.‘s [31] research on immature extracted teeth, SWEEPS resulted in a greater amount of apical extrusion compared to the NSI method and ultrasonic irrigation. Present research showed similar amounts of extruded irrigant among NSI (0,05 ml/s IVF) and SSP mode with PIPS and radial SWEEPS FTs while all other tested groups exhibited statistically significant greater amount of extruded irrigant. As demonstrated, the apical extrusion of an irrigant is influenced by multiple factors, including the periapical pressure (PP), the size and shape of the instrumented root canal (e.g. mature or immature teeth), patency size, canal curvature, irrigation technique, and location of the root apex [

23].

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The free volumetric extrusion of NaOCl was measured. Methodological protocol was constrained by the lack of an accurate PP value. Although the central venous pressure (5.88 mmHg) could be used instead of the PP, inflammatory altered apical tissue (e.g., granuloma, cyst) and a systemic human disease (cardiovascular disease, valvular abnormalities, cardiac arrhythmias, etc.) may influence a change in the PP [32,33]. Furthermore, the obtained results have limited clinical significance because no information is available about the amount of extruded irrigant to be dangerous and cause NaOCl accidents. However, the present study aimed to demonstrate the difference in irrigant extrusion potential among same FTs when used in different LAI modes. Therefore, they provide a valuable guidance for the choice of a particular FT during Er:YAG LAI.

As shown, the literature review reveals significant discrepancies in the protocols used across studies, resulting in varying levels of irrigant extrusion when comparing SSP and Auto SWEEPS modes. Although the advantages of LAI are well-recognized, the observed variations in irrigation outcomes emphasize the need for further research essential to achieve precise and reproducible methodologies, which will facilitate more accurate comparisons of results across different studies and clinical settings. This approach will not only improve the reliability of findings but also enhance the overall understanding and application of LAI techniques in clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, the AutoSWEEPS mode of Er:YAG LAI resulted in greater extrusion of NaOCl compared to the SSP mode. The use of different FTs had a significant effect on the amount of extruded irrigant: The PIPS FT caused the least extrusion and the SWEEPS FT caused the highest extrusion of NaOCl, regardless of the LAI modality used.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, D.Š. and J.V.H.; validation, D.Š. and I.B.P.; formal analysis, I.B.P.; investigation, D.Š.; resources, I.B.; data curation, D.Š. and J.V.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.V.H.; writing—review and editing, I.B. and J.V.H.; visualization, D.Š. and R.D.; supervision, R.D.; project administration, I.B..; funding acquisition I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the research project Croatian Science Foundation “Experimental and clinical evaluation of laser- activated photoacoustic streaming and photoactivated disinfection in endodontic treatment,” grant number: N0 5303.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the research project Croatian Science Foundation “Experimental and clinical evaluation of laser- activated photoacoustic streaming and photoactivated disinfection in endodontic treatment,” grant number: N0 5303.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Haapasalo, M.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Y. Irrigation in endodontics. Br Dent J 2014, 216, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulabivala, K.; Ng, Y.L. Factors that affect the outcomes of root canal treatment and retreatment-A reframing of the principles. Int Endod J 2023, 56, Suppl 2, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutsioukis, C.; Arias-Moliz, M.T. Present status and future directions – irrigants and irrigation methods. Int Endod J 2022, 55, Suppl 3, 588–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutsioukis, C.; Lambrianidis, T.; Verhaagen, B.; Versluis, M.; Kastrinakis, E.; Wesselink, P.R.; van der Sluis, L.W.M. The effect of needle-insertion depth on the irrigant flow in the root canal: evaluation using an unsteady computational fluid dynamics model. J Endod 2010, 36, 1664–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutsioukis, C.; Gutierrez Nova, P. Syringe irrigation in minimally shaped root canals using 3 endodontic needles: a computational fluid dynamics study. J Endod 2021, 47, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutsioukis, C.; Verhaagen, B.; Versluis, M.; Kastrinakis, E.; Wesselink, P.R.; van der Sluis, L.W.M. Evaluation of irrigant flow in the root canal using different needle types by an unsteady Computational Fluid Dynamics model. J Endod 2010, 36, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.R.; Ricucci, D.; Vieira, G.C.S.; Provenzano, J.C.; Alves, F.R.F.; Marceliano-Alves, M.F.; Rôças, I.N.; Siqueira, J.F. Jr. Cleaning, shaping, and disinfecting abilities of 2 instrument systems as evaluated by a correlative micro-computed tomographic and Histobacteriologic approach. J Endod 2020, 46, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaneo, I.; Amoroso-Silva, P.; Pacheco-Yanes, J.; Alves, F.R.F.; Marceliano-Alves, M.; Olivares, P.; Meto, A.; Mdala, I.; Siqueira, J.F. Jr.; Rôças, I.N. Disinfecting and shaping Type I C-shaped root canals: A correlative micro-computed tomographic and molecular microbiology study. J Endod 2021, 47, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, H.; Özlek, E. The effects of laser and ultrasonic irrigation activation methods on smear and debris removal in traditional and conservative endodontic access cavities. Lasers Med Sci 2023, 38, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, I.; Đurin, A.; Kanižaj, D.; Vuletić, L.B.; Zdrilić, I.V.; Anić, I. The efficacy of a novel SWEEPS laser-activated irrigation compared to ultrasonic activation in the removal of pulp tissue from an isthmus area in the apical third of the root canal. Lasers Med Sci 2023, 38, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnermeyer, D.; Averkorn, C.; Bürklein, S.; Schäfer, E. Cleaning efficiency of different irrigation techniques in simulated severely curved complex root canal systems. J Endod 2023, 49, 1548–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robberecht, L.; Delattre, J.; Meire, M. Isthmus morphology influences debridement efficacy of activated irrigation: A laboratory study involving biofilm mimicking hydrogel removal and high-speed imaging. Int Endod J 2023, 56, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, S.D.; Verhaagen, B.; Versluis, M.; Wu, M.K.; Wesselink, P.R.; van der Sluis, L.W. Laser-activated irrigation within root canals: cleaning efficacy and flow visualization. Int Endod J 2009, 42, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swimberghe, R.C.D.; Tzourmanas, R.; De Moor, R.J.G.; Braeckmans, K.; Coenye, T.; Meire, M.A. Explaining the working mechanism of laser-activated irrigation and its action on microbial biofilms: A high-speed imaging study. Int Endod J 2022, 55, 1372–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.D.; Jaramillo, D.E.; DiVito, E.; Peters, O.A. Irrigant flow during photon-induced photoacoustic streaming (PIPS) using particle image velocimetry (PIV). Clin Oral Investig 2016, 20, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, D.; Kustarci, A. Efficacy of photon-initiated photoacoustic streaming on apically extruded debris with different preparation systems in curved canals. Int Endod J 2018, 51, Suppl 1, e65–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meire, M.; De Moor, R.J.G. Principle and antimicrobial efficacy of laser-activated irrigation: A narrative review. Int Endod J 2024, 57, 841–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukač, N.; Jezeršek, M. Amplification of pressure waves in laser-assisted endodontics with synchronized delivery of Er:YAG laser pulses. Lasers Med Sci 2018, 33, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidas, J.; Snjaric, D.; Braut, A.; Carija, Z.; Persic Bukmir, R.; De Moor, R.J.G.; Brekalo Prso, I. Comparison of apical irrigant solution extrusion among conventional and laser-activated endodontic irrigation. Lasers Med Sci 2020, 35, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liapis, D.; De Bruyne, M.A.A.; De Moor, R.J.G.; Meire, M.A. Postoperative pain after ultrasonically and laser-activated irrigation during root canal treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Int Endod J 2021, 54, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolhari, B.; Meraji, N.; Seddighi, R.; Ebrahimi, N.; Chiniforush, N. Effect of SWEEPS and PIPS techniques on dye extrusion in photodynamic therapy procedure after root canal preparation. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2023, 42, 103345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezeršek, M.; Jereb, T.; Lukač, N.; Tenyi, A.; Lukač, M.; Fidler, A. Evaluation of apical extrusion during novel Er:YAG laser-activated irrigation modality. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg 2019, 37, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezeršek, M.; Lukač, N.; Lukač, M.; Tenyi, A.; Olivi, G.; Fidler, A. Measurement of pressures generated in root canal during Er:YAG laser-activated irrigation. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg 2020, 38, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürklein, S.; Abdi, I.; Schäfer, E.; Appel, C.; Donnermeyer, D. Influence of pulse energy, tip design and insertion depth during Er:YAG-activated irrigation on cleaning efficacy in simulated severely curved complex root canal systems in vitro. Int Endod J 2024, 57, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meire, M.; De Moor, R.J.G. Principle and antimicrobial efficacy of laser-activated irrigation: A narrative review. Int Endod J 2024, 57(7):841-60. [CrossRef]

- Gregorcic, P.; Jezersek, M.; Mozina, J. Optodynamic energy-conversion efficiency during an Er:YAG-laser-pulse delivery into a liquid through different fiber-tip geometries. J Biomed Opt 2012, 17(7):075006. [CrossRef]

- Mrochen, M.; Riedel; Donitzky, C.; Seiler, T. Erbium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser induced vapor bubbles as a function of the quartz fiber tip geometry. J Biomed Opt 2001, 6(3):344–350. [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Satake, K.; Watanabe, S.; Ebihara, A.; Kobayashi, C.; Okiji, T. Effect of laser energy and tip insertion depth on the pressure generated outside the apical foramen during Er:YAG laser-activated root canal irrigation. Photomed Laser Surg 2017, 35(12):682–687. [CrossRef]

- Vatanpour, M.; Fazlyab, M.; Nikzad, M. Comparative effects of erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser, the shock wave-enhanced emission photoacoustic streaming, and the conventional needle irrigation on apical extrusion of irrigants. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2022, 39, 102878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, G.; Singh., I; Shetty, S.; et al. Evaluation of apical extrusion of debris and irrigant using two new reciprocating and one continuous rotation single file systems. J Dent(Tehran) 2014,11.302–9.

- Abat, V.H.; Bayrak, G.D.; Gündoğar, M. Assessment of apical extrusion in regenerative endodontics: a comparative study of different irrigation methods using three-dimensional immature tooth models. Odontology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Niu, L.N.; Eid, A.A.; Looney, S.W.; et al. Periapical pressures developed by nonbinding irrigation needles at various irrigation delivery rates. J Endod 2013. 39(4):529–533. [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Louis, M.A. Physiology, central venous pressure. StatPearls. Internet. In: StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519493/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).