Submitted:

07 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Reference | Sensor | Period | Algorithm | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belkin and Cornillon 2003 | AVHRR | 1985-1996 | CCA1992 | SCS |

| Belkin and Cornillon 2007 | AVHRR | 1985-1996 | CCA1992 | SCS |

| Belkin et al. 2009 | AVHRR | 1985-1996 | CCA1992 | SCS |

| Belkin et al. 2024 (this study) | AHI | 2015-2021 | BOA2009 | NSCS, including TS |

| Chang et al. 2006 | AVHRR | 1996-2005 | S2005 | TS |

| Chang et al. 2008 | AVHRR | 1996-2005 | S2005 | TS (north of 24°N) |

| Chang et al. 2010 | AVHRR | 2001-2007 | S2005 | NSCS, including TS |

| Dong and Zhong 2020 | AVHRR MODIS |

2009-2012 | GM | NSCS, including TS |

| Jing et al. 2015 | OSTIA | 2006-2013 | GM | NSCS |

| Jing et al. 2016 | GHRSST | 2006-2014 | GM | NSCS |

| Lee et al. 2015 | AVHRR | 1996-2009 | S2005 | TS (north of 24°N) |

| Pi and Hu 2010 | Misc.* | 2002-2008 | PH2010 | NSCS, including TS |

| Ping et al. 2016 | MODIS | 2000-2013 | CCA1992 | TS (north of 22°N) |

| Ren et al. 2021 | Model | 2005-2018 | Canny (1986) | SCS |

| Shi et al. 2015 | OSTIA | 2006-2011 | GM | NSCS |

| Wang DX et al. 2001 | AVHRR | 1991-1998 | GM | NSCS, including TS |

| Wang YC et al. 2013 | AVHRR | 2006-2009 | S2005 | TS |

| Wang YC et al. 2018 | AVHRR | 2005-2015 | S2005 | TS (north of 24°N) |

| Wang YT et al. 2020 | MODIS | 2002-2017 | W2020 | NSCS, including TS |

| Xing QW et al. 2023 | AVHRR | 1982-2021 | CCA1992 | China Seas |

| Yu et al. 2019 | MODIS | 2002-2017 | GM | SCS |

| Zeng et al. 2014 | MODIS | 2002-2011 | BOA2009 | East Hainan |

| Zhang L and Dong J 2021 | MODIS | 2016-2017 | GM | NSCS, 250-m L2 data |

| Zhang Y et al. 2021 | OSTIA | 2006-2015 | GM | NSCS, 3D structure |

| Zhao et al. 2022 | DOISST | 1982-2021 | CCA1992 | China Seas |

2. Data and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Introduction

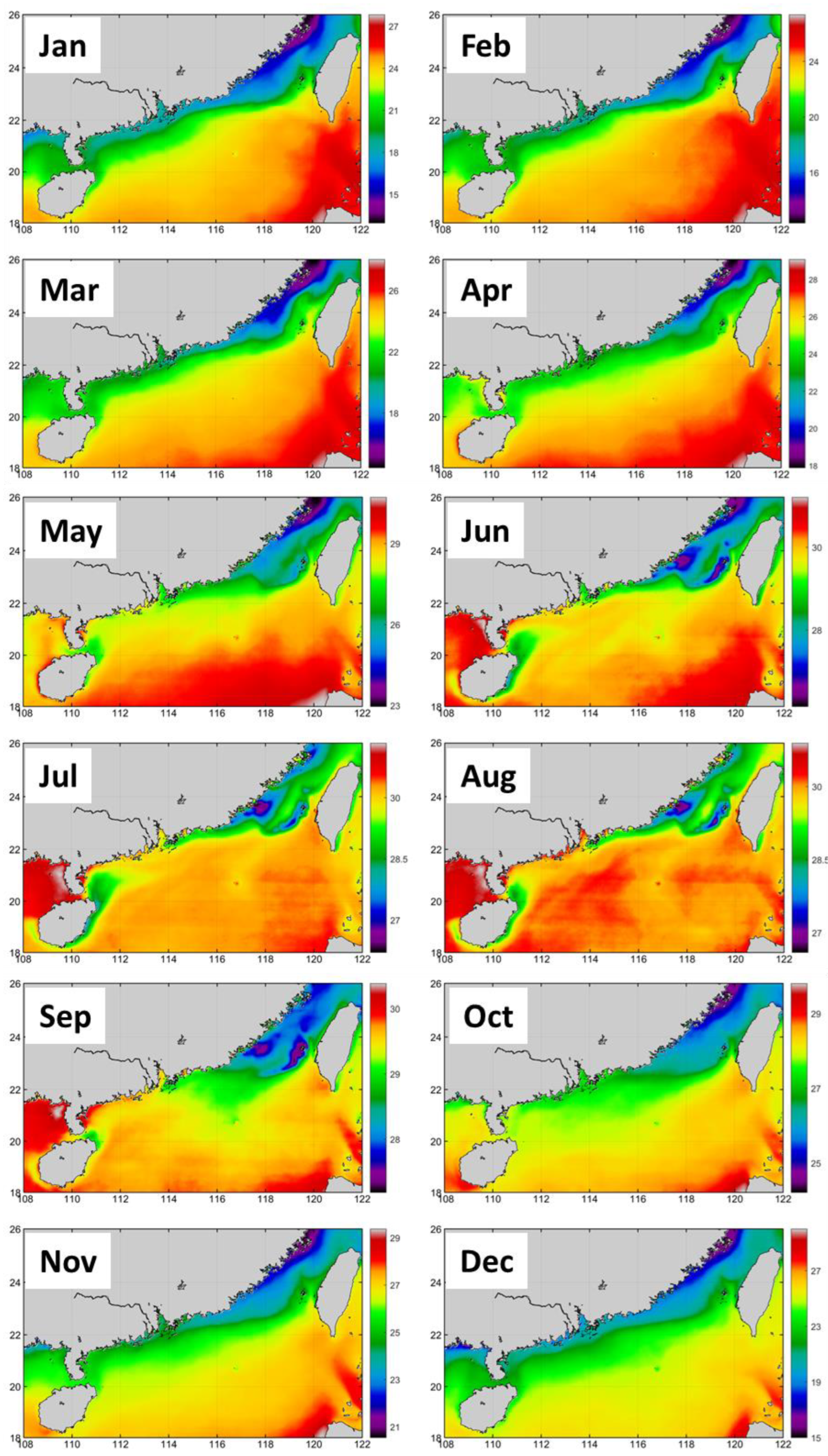

3.2. Sea Surface Temperature

3.2.1. Winter

3.2.2. Summer

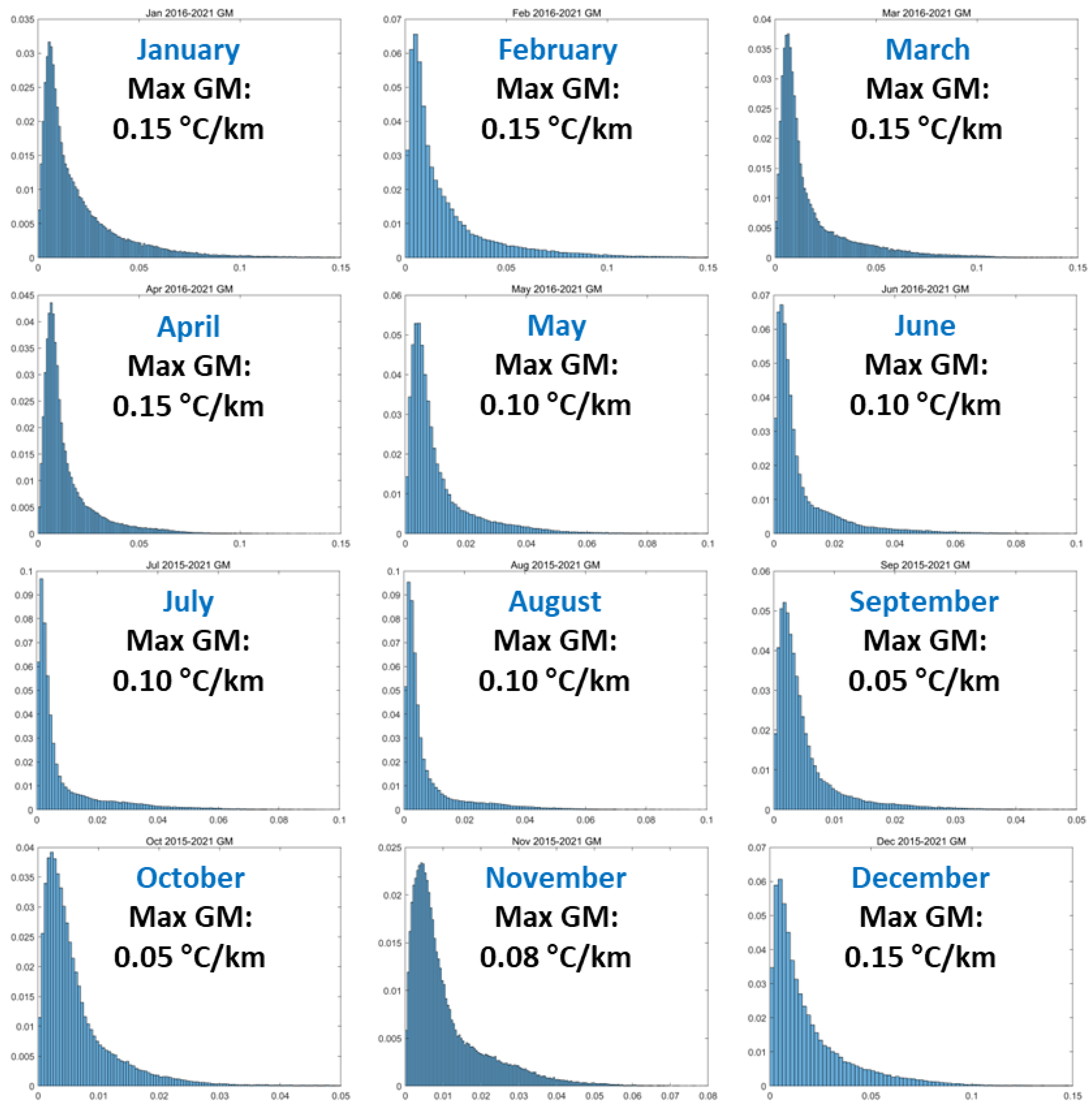

3.2. SST Gradient Magnitude GM

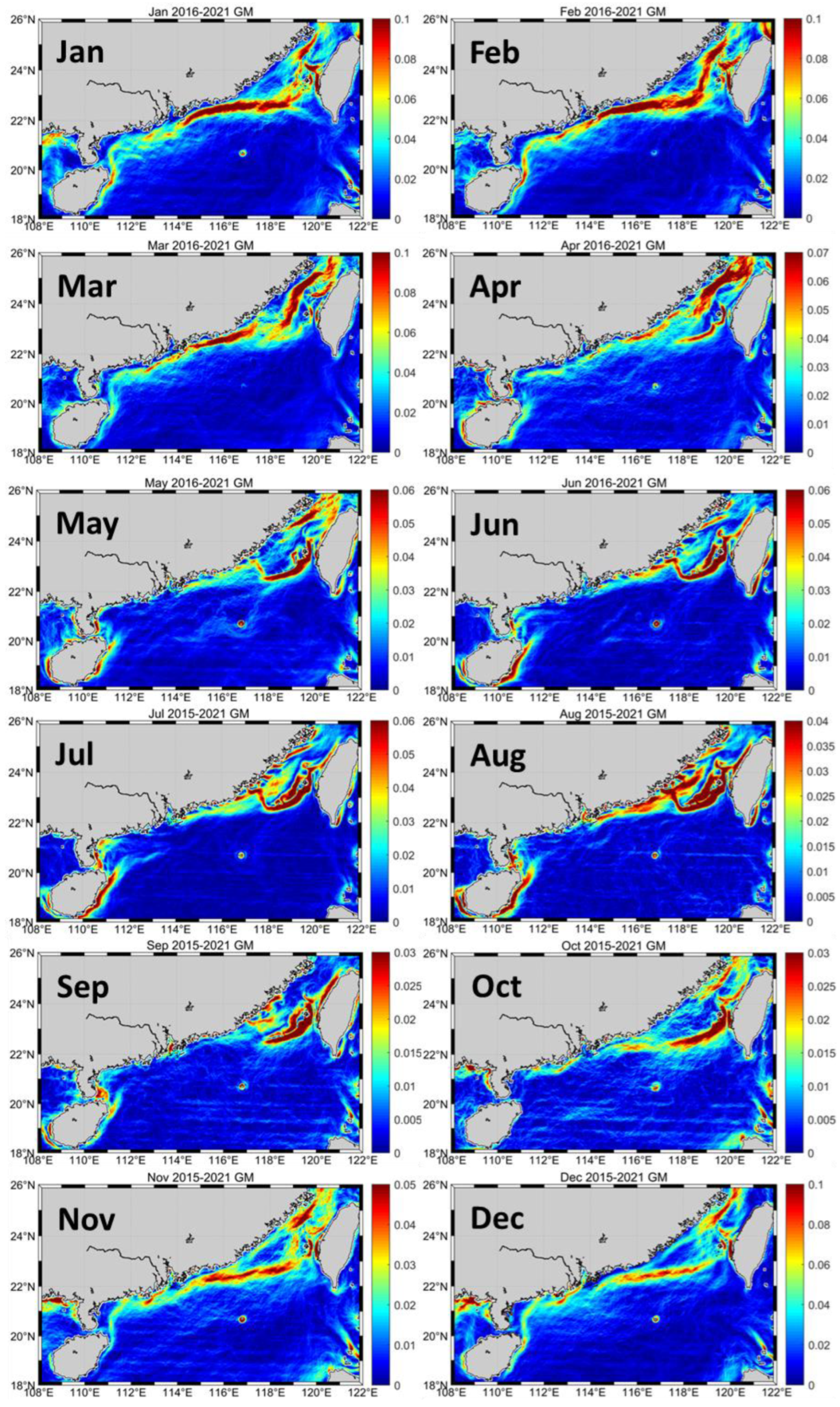

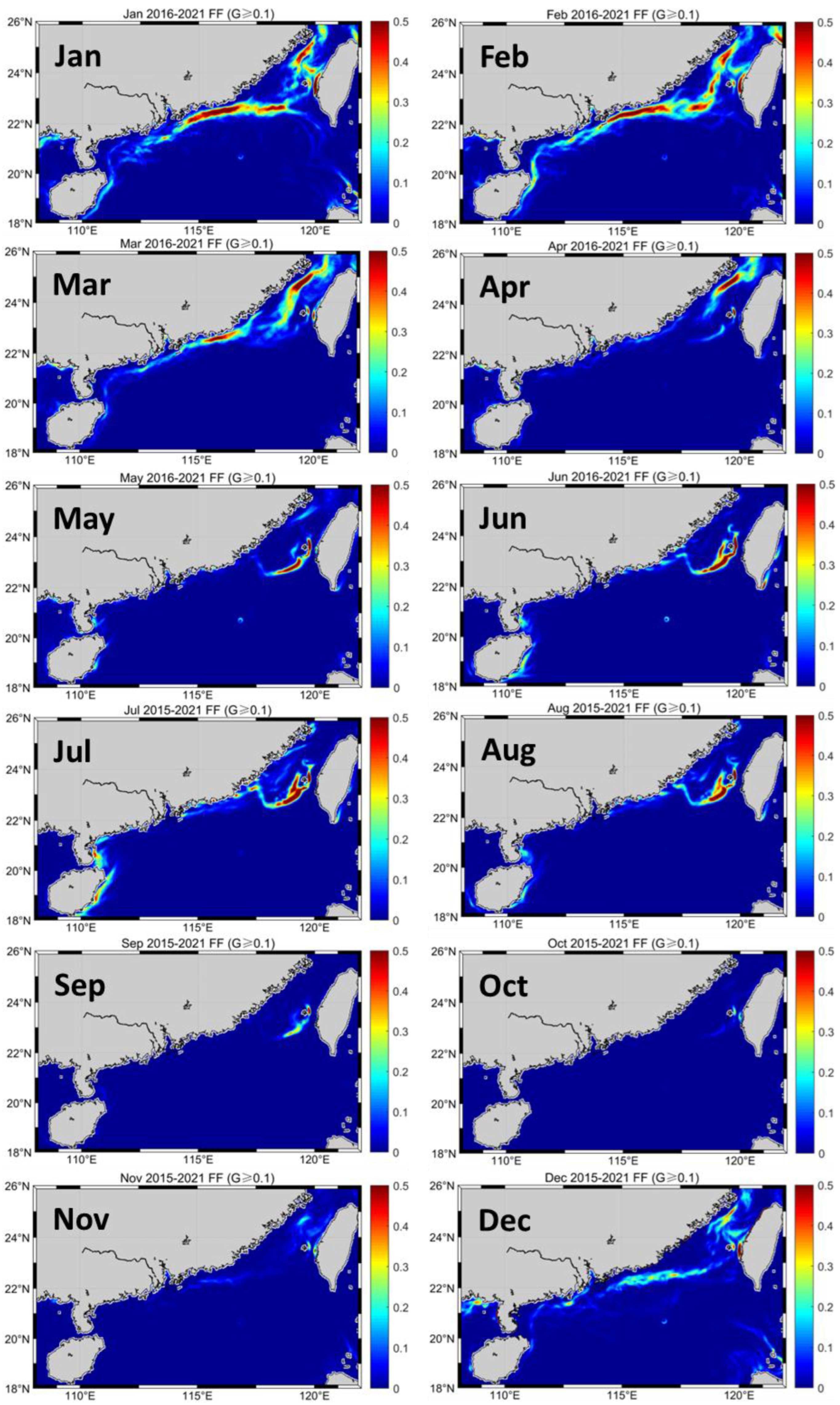

3.3. Statistics of SST Fronts: Frontal Frequency Maps

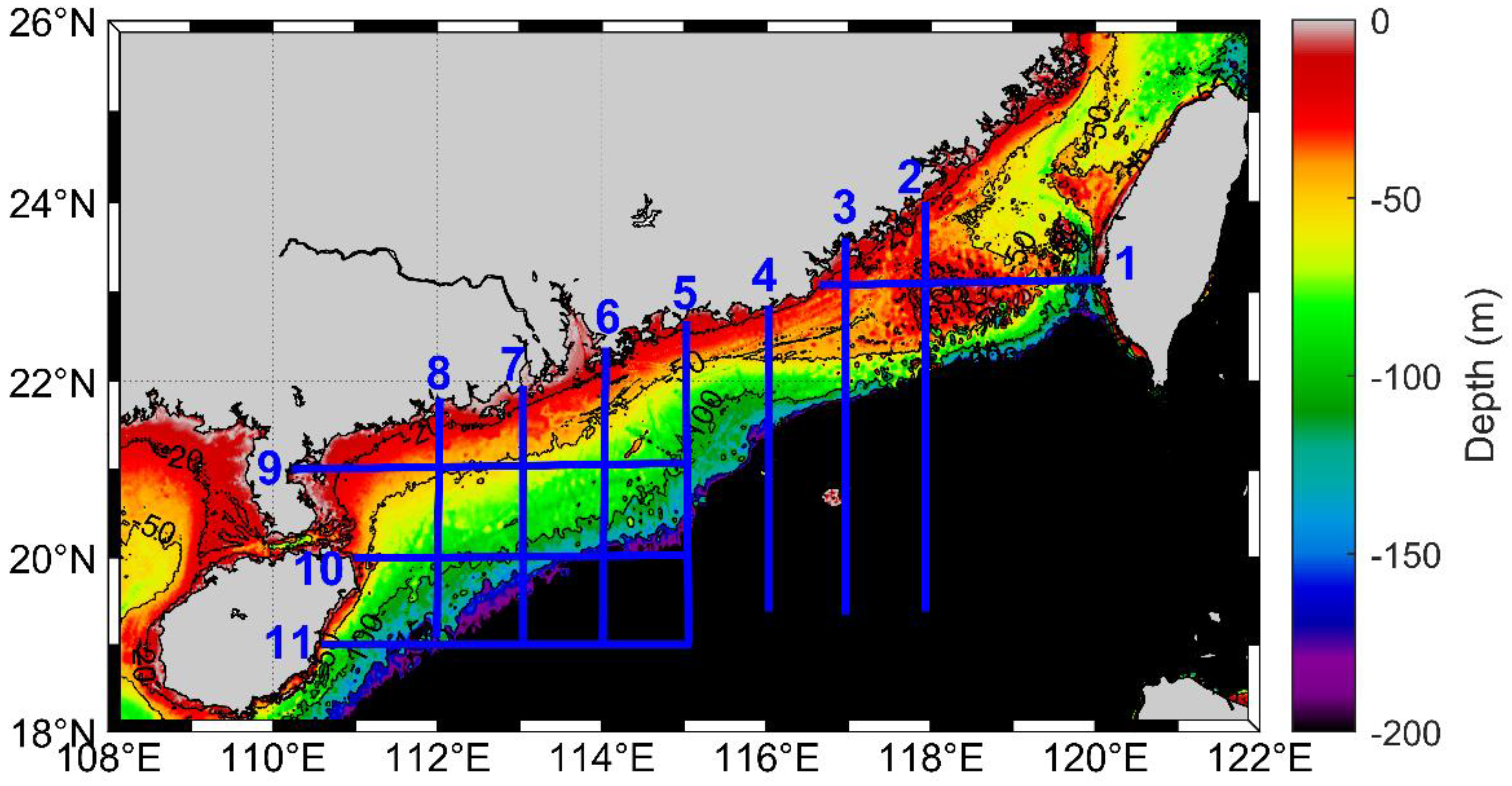

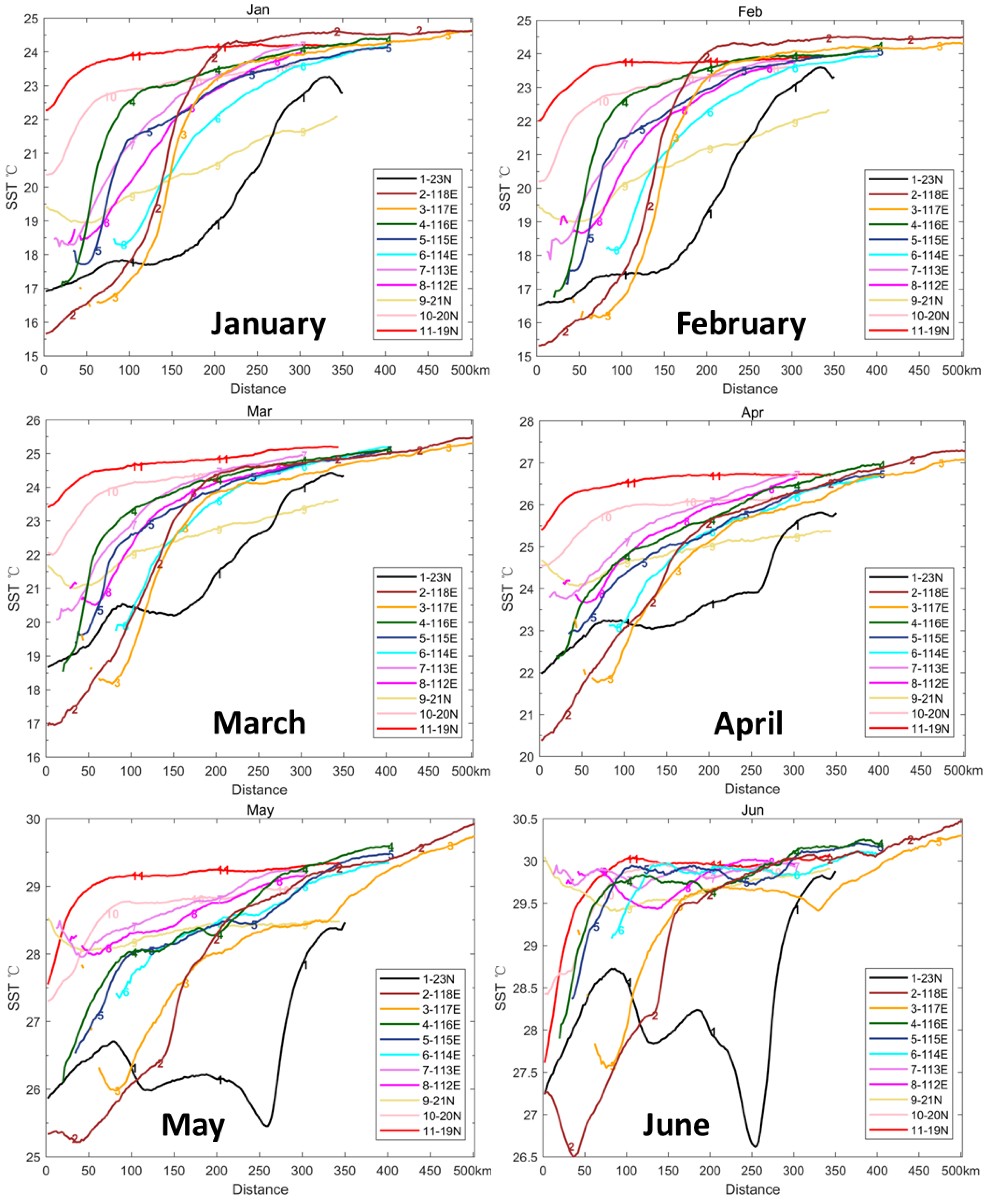

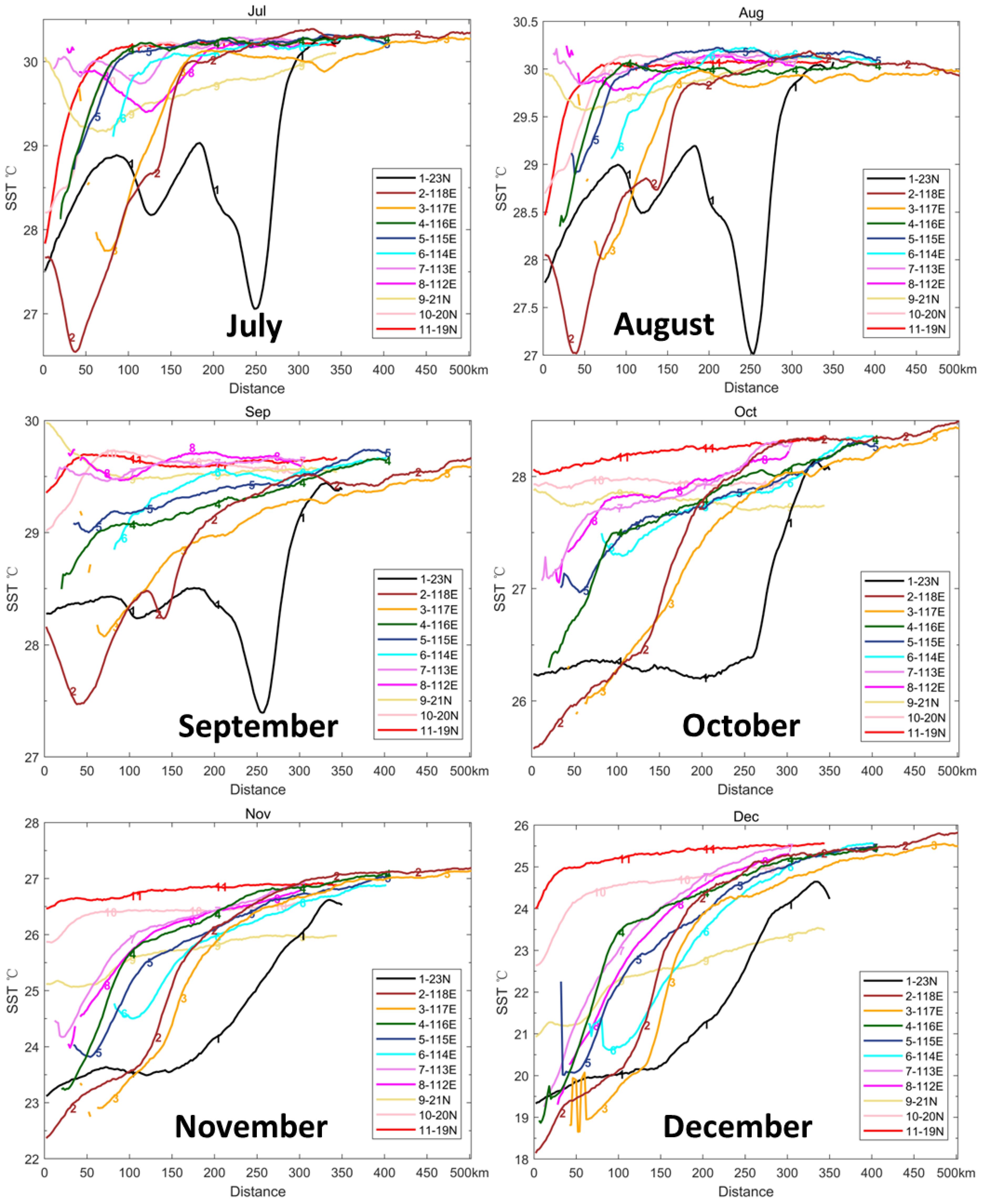

3.4. Cross-Frontal Distributions of SST along Fixed Lines across the Northern SCS

3.5. Analysis of SST Distributions along 11 Fixed Lines across the Northern SCS

| Line No. | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lon/Lat | 19N | 20N | 21N | 112E | 113E | 114E | 115E | 116E | 117E | 23N | 118E |

| Nov | 26.5-26.7* | 25.9-26.4 | 25.1-26.0 | 24.0-26.0 | 24.2-26.0 | 24.5-25.8 | 23.8-25.5 | 23.2-25.8 | 22.8-27.0 | 23.6-26.7 | 22.4-27.2 |

| Dec | 24.0-25.0 | 22.6-24.7 | 21.2-23.5* | 20.3-25.3* | 19.6-25.5* | 20.6-25.7* | 20.1-22.9* | 19.7-23.7 | 20.2-24.3 | 20.1-24.7 | 18.2-25.1 |

| Jan | 22.3-23.8* | 20.4-22.9 | 19.0-22.0* | 18.5-24.0* | 18.3-24.2* | 18.3-24.2* | 17.7-21.4! | 17.2-23.0! | 16.5- 24.2* |

17.7-23.3! | 15.7-24.3! |

| Feb | 22.0-23.7 | 20.2-22.8* | 19.0-22.2* | 18.7-23.7* | 18.4-23.8* | 18.2-24.0* | 17.5-21.5 | 16.8-22.7* | 16.2-23.7 | 17.5-23.6 | 15.3-24.3 |

| Mar | 23.5-24.5 | 22.0-24.2 | 21.0-23.6* | 20.5-24.5* | 20.3-24.9* | 19.9-25.3* | 19.6-22.3 | 18.5-23.4* | 18.2-23.8 | 20.2-24.5 | 17.0-24.6 |

| Apr | 25.4-26.4* | 24.5-26.0 | 24.1-25.3* | 23.6-26.6* | 23.7-26.7* | 23.1-26.7* | 23.0-26.7* | 22.3-27.0 | 21.8-27.1* | 23.9*-25.8 | 20.4-25.7 |

4. Discussion

4.1. China Coastal Front as a Major Link between the ECS and NSCS:

4.2. Guangdong Coastal Current and China Coastal Front

4.3. Westernmost extension of the China Coastal Current

4.4. East Hainan Front

4.5. Fujian and Guangdong Coastal Upwelling Fronts

4.6. Taiwan Bank Fronts

4.7. Pearl River Plume Front

4.8. Fronts and Climate Change

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belkin IM, 2021. Remote sensing of ocean fronts in marine ecology and fisheries. Remote Sensing 13(5), Article 883. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Cornillon PC, 2003. SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas. Pacific Oceanography 1(2), 90-113.

- Belkin IM, Cornillon PC, 2005. Bering Sea thermal fronts from Pathfinder data: Seasonal and interannual variability. Pacific Oceanography 3(1), 6-20.

- Belkin IM, Cornillon PC, 2007. Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007/D:21, 33 pp. https://www.ices.dk/sites/pub/CM%20Doccuments/CM-2007/D/D2107.

- Belkin IM, Gordon AL, 1996. Southern Ocean fronts from the Greenwich meridian to Tasmania. Journal of Geophysical Research 101(C2), 3675-3696. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Lee MA, 2014. Long-term variability of sea surface temperature in Taiwan Strait. Climatic Change 124(4), 821-834. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, O’Reilly JE, 2009. An algorithm for oceanic front detection in chlorophyll and SST satellite imagery. Journal of Marine Systems 78(3), 317-326. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Shan Z, Cornillon P, 1998. Global survey of oceanic fronts from Pathfinder SST and in-situ data. Eos Transactions AGU 79(45, Suppl.), F475.

- Belkin IM, Cornillon PC, Sherman K, 2009. Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems. Progress in Oceanography 81(1-4), 223-236. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Krishfield R, Honjo S, 2002. Decadal variability of the North Pacific Polar Front: Subsurface warming versus surface cooling. Geophysical Research Letters 29(9), pp. 65.1-65.4. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Lou SS, Yin WB, 2023. The China Coastal Front from Himawari-8 AHI SST Data—Part 1: East China Sea. Remote Sensing 15(8), Article 2123. [CrossRef]

- Bessho K, Date K, Hayashi M, Ikeda A, Imai T, Inoue H, Kumagai Y, Miyakawa T, Murata H, Ohno T, Okuyama A, Oyama R, 2016. An introduction to Himawari-8/9 — Japan’s new-generation geostationary meteorological satellites. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan 94(2), 151-183. [CrossRef]

- Canny J, 1986. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 8(6), 679-698. [CrossRef]

- Castelao RM, Wang YT, 2014. Wind-driven variability in sea surface temperature front distribution in the California Current System. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 119(3), 1861-1875. [CrossRef]

- Cayula JF, Cornillon P, 1992. Edge detection algorithm for SST images. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 9(1), 67-80. [CrossRef]

- Cayula JF, Cornillon P, 1995. Multi-image edge detection for SST images. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 12(4), 821-829. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y, Shimada T, Lee MA, Lu HJ, Sakaida F, Kawamura H, 2006. Wintertime sea surface temperature fronts in the Taiwan Strait. Geophysical Research Letters 33(23), L23603. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y, Lee MA, Shimada T, Sakaida F, Kawamura H, Chan JW, Lu HJ, 2008. Wintertime high-resolution features of sea surface temperature and chlorophyll-a fields associated with oceanic fronts in the southern East China Sea. International Journal of Remote Sensing 29(21), 6249-6261. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y, Shieh WJ, Lee MA, Chan JW, Lan KW, Weng JS, 2010. Fine-scale sea surface temperature fronts in wintertime in the northern South China Sea. International Journal of Remote Sensing 31(17), 4807-4818. [CrossRef]

- Chen CTA, 2009. Chemical and physical fronts in the Bohai, Yellow and East China seas. Journal of Marine Systems 78(3), 394-410. [CrossRef]

- Dong J, Zhong Y, 2020. Submesoscale fronts observed by satellites over the Northern South China Sea shelf. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans 91, Article 101161. [CrossRef]

- Dong LX, Su JL, Wong LA, Cao ZY, Chen JC, 2004. Seasonal variation and dynamics of the Pearl River plume. Continental Shelf Research 24(16), 1761-1777. [CrossRef]

- Hickox R, Belkin I, Cornillon P, Shan Z, 2000. Climatology and seasonal variability of ocean fronts in the East China, Yellow and Bohai Seas from satellite SST data. Geophysical Research Letters 27(18), 2945-2948. [CrossRef]

- Hu JY, Wang XH, 2016. Progress on upwelling studies in the China seas. Review of Geophysics 54(3), 653-673. [CrossRef]

- Hu JY, San Liang X, Lin HY, 2018. Coastal upwelling off the China coasts. In: X. San Liang and Yuanzhi Zhang (editors), Coastal Environment, Disaster, and Infrastructure: A Case Study of China’s Coastline, pp. 3-25. IntechOpen, London, UK. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.80738.

- Hu ZF, Xie GH, Zhao J, Lei YP, Xie JC, Pang WH, 2022. Mapping diurnal variability of the wintertime Pearl River plume front from Himawari-8 geostationary satellite observations. Water 14(1), Article 43. [CrossRef]

- Huang TH, Chen CTA, Bai Y, He XQ, 2020. Elevated primary productivity triggered by mixing in the quasi-cul-de-sac Taiwan Strait during the NE monsoon. Scientific Reports 10(1), Article 7846. [CrossRef]

- Jing ZY, Qi YQ, Du Y, Zhang SW, Xie LL, 2015. Summer upwelling and thermal fronts in the northwestern South China Sea: Observational analysis of two mesoscale mapping surveys. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 120(3), 1993-2006. [CrossRef]

- Jing ZY, Qi YQ, Fox-Kemper B, Du Y, Lian SM, 2016. Seasonal thermal fronts on the northern South China Sea shelf: Satellite measurements and three repeated field surveys. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 121(3), 1914-1930. [CrossRef]

- Kuo YC, Chan JW, Wang YC, Shen YL, Chang Y, Lee MA, 2018. Long-term observation on sea surface temperature variability in the Taiwan Strait during the northeast monsoon season. International Journal of Remote Sensing 39(13), 4330-4342. [CrossRef]

- Lan KW, Kawamura H, Lee MA, Chang Y, Chan JW, Liao CH, 2009. Summertime sea surface temperature fronts associated with upwelling around the Taiwan Bank. Continental Shelf Research 29(7), 903-910. [CrossRef]

- Lao QB, Zhang SW, Li ZY, Chen FJ, Zhou X, Jin GZ, Huang P, Deng ZY, Chen CQ, Zhu QM, Lu X, 2022. Quantification of the seasonal intrusion of water masses and their impact on nutrients in the Beibu Gulf using dual water isotopes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 127(7), Article e2021JC018065. [CrossRef]

- Lee MA, Chang Y, Shimada T, 2015. Seasonal evolution of fine-scale sea surface temperature fronts in the East China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part II 119, 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Lee MA, Huang WP, Shen YL, Weng JS, Bambang S, Wang YC, Chan JW, 2021. Long-term observations of interannual and decadal variation of sea surface temperature in the Taiwan Strait. Journal of Marine Science and Technology (Taiwan) 29(4), 525-536. [CrossRef]

- Li JY, Li M, Wang C, Zheng QA, Xu Y, Zhang TY, Xie LL, 2023. Multiple mechanisms for chlorophyll a concentration variations in coastal upwelling regions: a case study east of Hainan Island in the South China Sea. Ocean Science, 19(2), 469-484. [CrossRef]

- Li YN, Curchitser EN, Wang J, Peng SQ, 2020. Tidal effects on the surface water cooling northeast of Hainan Island, South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 125(10), Article e2019JC016016. [CrossRef]

- Lin PG, Cheng P, Gan JP, Hu JY, 2016. Dynamics of wind-driven upwelling off the northeastern coast of Hainan Island. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 121(2), 1160-1173, . [CrossRef]

- Liu ZZ, Fagherazzi S, Liu XH, Shao DD, Miao CY, Cai YZ, Hou CY, Liu YL, Li Xia, Cui BS, 2022. Long-term variations in water discharge and sediment load of the Pearl River Estuary: Implications for sustainable development of the Greater Bay Area. Frontiers in Marine Science 9, Article number 983517. [CrossRef]

- Ou SY, Zhang H, Wang DX, 2009. Dynamics of the buoyant plume off the Pearl River Estuary in summer. Environmental Fluid Mechanics 9(5), 471-492. [CrossRef]

- Pi QL, Hu JY, 2010. Analysis of sea surface temperature fronts in the Taiwan Strait and its adjacent area using an advanced edge detection method. Science China Earth Sciences 53 (7), 1008-1016. [CrossRef]

- Ping B, Su FZ, Meng YS, Du YY, Fang SH, 2016. Application of a sea surface temperature front composite algorithm in the Bohai, Yellow, and East China Seas. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology 34 (3), 597-607. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Y, Li L, Chen CTA, Guo XG, Jing CS, 2011. Currents in the Taiwan Strait as observed by surface drifters. Journal of Oceanography 67 (4), 395-404. [CrossRef]

- Ren SH, Zhu XM, Drevillon A, Wang H, Zhang YF, Zu ZQ, Li A, 2021. Detection of SST fronts from a high-resolution model and its preliminary results in the South China Sea. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 38 (2), 387-403. [CrossRef]

- Roberts JJ, Best BD, Dunn DC, Treml EA, Halpin PN, 2010. Marine Geospatial Ecology Tools: An integrated framework for ecological geoprocessing with ArcGIS, Python, R, MATLAB, and C++. Environmental Modelling & Software 25 (10), 1197-1207. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.T., Belkin, I.M., 2023. Observational studies of ocean fronts: A systematic review of Chinese-language literature. Water, under review.

- Shi MC, Chen CS, Xu QC, Lin HC, Liu GM, Wang H, Wang F, Yan JH, 2002. The role of Qiongzhou Strait in the seasonal variation of the South China Sea circulation. Journal of Physical Oceanography 32 (1), 103-121. [CrossRef]

- Shi R, Guo XY, Wang DX, Zeng LL, Chen J, 2015. Seasonal variability in coastal fronts and its influence on sea surface wind in the Northern South China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part II 119, 30-39. [CrossRef]

- Shi R, Chen J, Guo XY, Zeng LL, Li J, Xie Q, Wang X, Wang DX, 2017. Ship observations and numerical simulation of the marine atmospheric boundary layer over the spring oceanic front in the northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 122 (7), 3733-3753, . [CrossRef]

- Shi R, Guo XY, Chen J, Zeng LL, Wu B, Wang DX, 2022. Effects of spatial scale modification on the responses of surface wind stress to the thermal front in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Climate 35 (1), 179-194. [CrossRef]

- Shi WA, Huang Z, Hu JY, 2021. Using TPI to map spatial and temporal variations of significant coastal upwelling in the northern South China Sea. Remote Sensing 13, Article 1065. [CrossRef]

- Shimada T, Sakaida F, Kawamura H, Okumura T, 2005. Application of an edge detection method to satellite images for distinguishing sea surface temperature fronts near the Japanese coast. Remote Sensing of Environment 98 (1), 21-34. [CrossRef]

- Shu YQ, Wang Q, Zu TT, 2018. Progress on shelf and slope circulation in the northern South China Sea. Science China (Earth Sciences) 61 (5), 560-571. [CrossRef]

- Su JL, 2004. Overview of the South China Sea circulation and its influence on the coastal physical oceanography outside the Pearl River Estuary. Continental Shelf Research 24 (16), 1745-1760. [CrossRef]

- Wang DX, Liu Y, Qi YQ, Shi P, 2001. Seasonal variability of thermal fronts in the Northern South China Sea from satellite data. Geophysical Research Letters 28 (20), 3963-3966. [CrossRef]

- Wang YC, Chen WY, Chang Y, Lee MA, 2013. Ichthyoplankton community associated with oceanic fronts in early winter on the continental shelf of the southern East China Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Technology 21 (Suppl.), 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Wang YC, Chan JW, Lan YC, Yang WC, Lee MA, 2018. Satellite observation of the winter variation of sea surface temperature fronts in relation to the spatial distribution of ichthyoplankton in the continental shelf of the southern East China Sea. International Journal of Remote Sensing 39 (13), 4550-4564. [CrossRef]

- Wang YT, Castelao RM, Yuan YP, 2015. Seasonal variability of alongshore winds and sea surface temperature fronts in Eastern Boundary Current Systems. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 120 (3), 2385-2400. [CrossRef]

- Wang YT, Yu Y, Zhang Y, Zhang HR, Chai F, 2020. Distribution and variability of sea surface temperature fronts in the South China Sea. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 240, 106793. [CrossRef]

- Xing QW, Yu HQ, Wang H, Ito SI, 2023. An improved algorithm for detecting mesoscale ocean fronts from satellite observations: Detailed mapping of persistent fronts around the China Seas and their long-term trends. Remote Sensing of Environment 294, Article 113627. [CrossRef]

- Yang LQ, Huang ZD, Sun ZY, Hu JY, 2021. Surface currents along the coast of the Chinese Mainland observed by coastal drifters in autumn and winter. Marine Technology Society Journal 55 (5), 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Yang LQ, Sun ZY, Hu ZY, Huang ZD, Chen ZZ, Zhu J, Hu JY, 2023. Surface currents along the coast of the Chinese Mainland observed by coastal drifters during April-May 2019. Marine Technology Society Journal 57 (1), 156-167. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Zhang HR, Jin JB, Wang YT, 2019. Trends of sea surface temperature and sea surface temperature fronts in the South China Sea during 2003–2017. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 38 (4), 106-115. [CrossRef]

- Zeng XZ, Belkin IM, Peng SQ, Li YN, 2014. East Hainan upwelling fronts detected by remote sensing and modelled in summer. International Journal of Remote Sensing 35 (11-12), 4441-4451. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Li XF, Hu JY, Sun ZY, Zhu J, Chen ZZ, 2014. Summertime sea surface temperature and salinity fronts in the southern Taiwan Strait. International Journal of Remote Sensing 35 (11-12), 4452-4466. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Dong J, 2021. Dynamic characteristics of a submesoscale front and associated heat fluxes over the northeastern South China Sea shelf. Atmosphere-Ocean 59 (3), 190-200. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Zeng LL, Wang Q, Geng BX, Liu CJ, Shi R, Liu N, Wang WP, Wang DX, 2021. Seasonal variation in the three-dimensional structures of coastal thermal front off western Guangdong. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 40 (7), 88-99. [CrossRef]

- Zhao LH, Yang DT, Zhong R, Yin XQ, 2022. Interannual, seasonal, and monthly variability of sea surface temperature fronts in offshore China from 1982–2021. Remote Sensing 14 (21), Article 5336. [CrossRef]

- Zhu XM, Wang H, Liu GM, Régnier C, Kuang XD, Wang DK, Ren SH, Jing ZY, Drévillon M, 2016. Comparison and validation of global and regional ocean forecasting systems for the South China Sea. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 16 (7), 1639-1655. [CrossRef]

- Zu TT, Wang DX, Gan JP, Guan WB, 2014. On the role of wind and tide in generating variability of Pearl River plume during summer in a coupled wide estuary and shelf system. Journal of Marine Systems 136 (1), 65-79. [CrossRef]

- Zu TT, Gan JP, 2015. A numerical study of coupled estuary–shelf circulation around the Pearl River Estuary during summer: Responses to variable winds, tides and river discharge. Deep-Sea Research Part II 117, 53-64. [CrossRef]

| Line | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 (20°N) | 25.9-26.4 | 22.6-24.5 | 20.4-22.8 | 20.2-22.7 | 22.0-24.0 | 24.5-26.0 | 27.3-28.8 | 28.4-29.9 | 28.2- 30.2 |

28.7-30.2 | 29.0-29.7 | 27.9-27.9 |

| 11 (19°N) | 26.5-26.6 | 24.0-25.0 | 22.3-23.8 | 22.0-23.7 | 23.5-24.5 | 25.5-26.3 | 27.5-29.2 | 27.6-30.0 | 27.8-30.2 | 28.5-30.0 | 29.4-29.7 | 28.0-28.1 |

| Line | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (23°N) | 26.1-25.5-28.3 | 28.3-26.6-29.8 | 29.1-27.1-30.3 | 29.2-27.0-30.1 | 28.5-27.4-29.5 |

| 2 (118°E) | No upwelling | 27.3-26.5-29.5 | 27.7-26.5-30.0 | 28.0-27.0-29.8 | 28.2-27.5-29.5 |

| Line | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (23°N) | 23.1-23.6 | 19.4-20.0 | 17.0-17.8 | 16.5-17.4 | 18.7-20.5 | 22.0-23.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).