Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Methodologies

3.1. Data Exploration and Preprocessing

3.1.1. Text Cleaning

3.1.2. Feature Enrichment

- Syno_Lower_Mean: This feature quantifies the use of less common synonyms by calculating the mean frequency of synonyms that are less frequently used in the language.

- Syn_Mean: This feature represents the mean frequency of all synonyms for each word in a tweet, providing an aggregate measure of synonym usage.

3.1.3. Feature Selection

3.1.4. Imbalanced Learning

3.1.5. Tokenization and Counting

3.2. Classification

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): A powerful classifier that finds the optimal hyperplane to separate classes in a high-dimensional space [24].

- k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): A simple, yet effective, classifier that assigns a class label based on the majority class of its nearest neighbors in the feature space [25].

- Logistic Regression: A linear model that estimates the probability of a sample belonging to a class using a logistic function [26].

- Decision Trees: A non-parametric model that splits the data into subsets based on feature values, creating a tree-like structure of decisions [27].

- Random Forest: An ensemble method that combines multiple decision trees to improve accuracy and reduce overfitting [11].

- BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers): A deep learning model that captures the context from both directions in a text, providing a rich representation of language [14].

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): A type of recurrent neural network (RNN) that can learn long-term dependencies in sequential data, making it suitable for text classification [16].

3.3. Explainability

- Decision Tree Analysis: We analyse the structure of decision trees to understand the decision rules and the importance of the features.

- Feature Importance Analysis: We calculated feature importance scores for decision trees and SVM to identify the most influential features in the classification tasks [28].

- TREPAN Approximation: We approximated the TREPAN algorithm to explain SVM predictions by extracting decision rules from a trained SVM model [29].

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Classification Task 1: Figurative vs Non-Figurative Language

4.2.1. Support Vector Machines

- Without Class Weights: In this scenario, we trained the SVM model without adjusting the class weights. The model showed moderate performance but was biased towards the majority class.

- With Class Weights 0: 0.85, 1: 0.7: To address class imbalance, we adjusted class weights, assigning higher weights to the minority class. This resulted in an improved F1 score of 0.60, indicating a better performance in the detection of figurative language [24].

- With Class Weights 0: 0.35, 1: 0.4, Using Only Syn_Lower_Mean and Syn_Mean Features: We further refined the model by using only the two novel features and adjusting the class weights. This scenario aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the new features. The performance was comparable to scenario (b), demonstrating the significance of the novel features.

4.2.2. k-Nearest Neighbors

- Baseline Model: The baseline KNN model showed moderate performance with an accuracy of 0.60.

- With SenticNet Information: Incorporating sentiment-related information from SenticNet improved the accuracy to 0.66, highlighting the importance of semantic features [25].

4.2.3. Logistic Regression

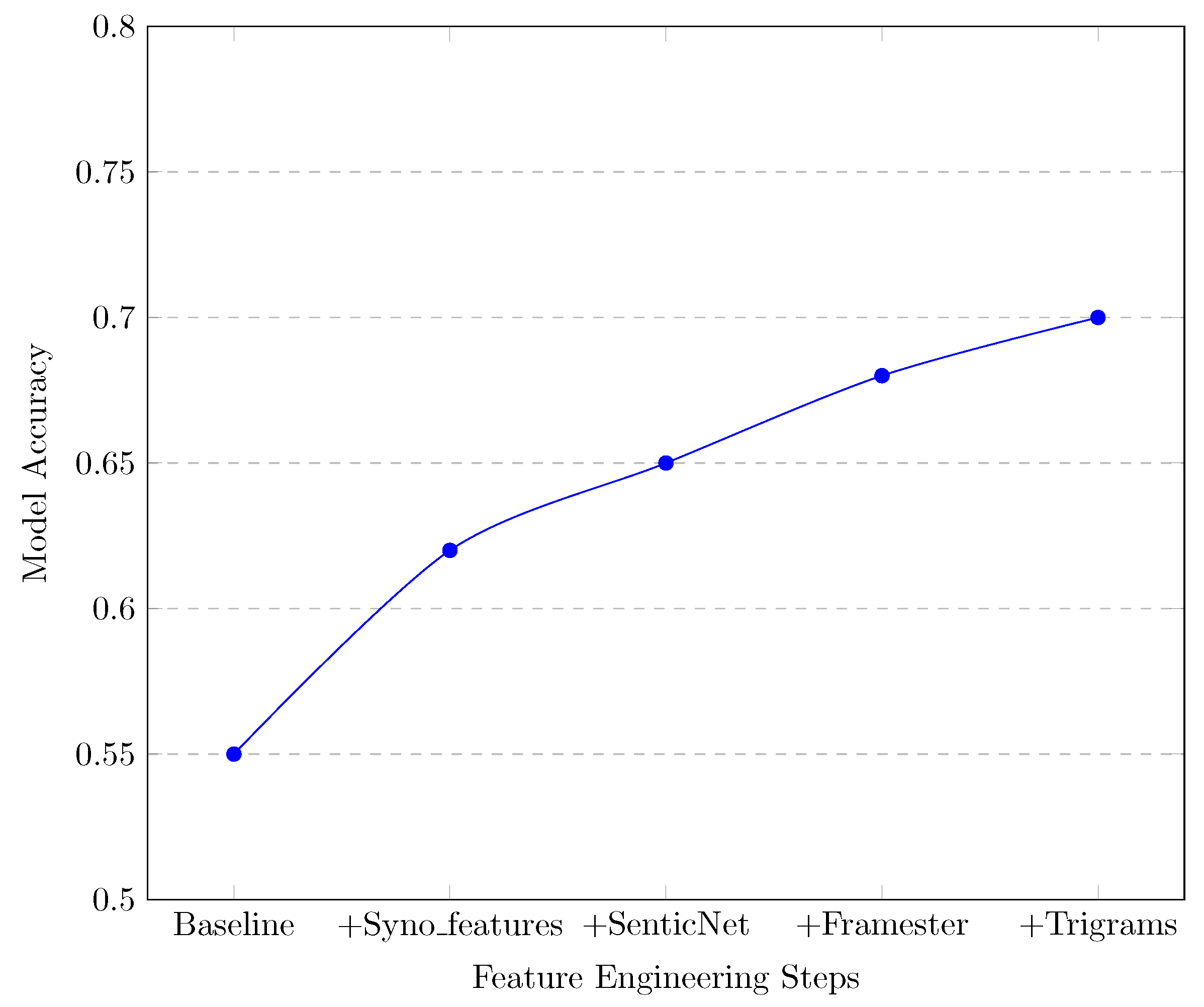

- Baseline Model: The baseline model performed poorly with an accuracy of 55%.

- With Negation Handling: Adding techniques to handle negations, such as reversing the polarity of sentiment-bearing words, significantly improved the accuracy to 65% [26].

4.2.4. Decision Tree Classifier

- All Features: Using all features, the decision tree classifier achieved an accuracy of 64%.

- Novel Features Only: When using only the two novel features, Syno_Lower_Mean and Syn_Mean, the model maintained a similar accuracy, demonstrating the strength of these features [27].

4.2.5. Random Forest

- CountVectorizer without NEG Features: The model achieved the highest accuracy of 70% using CountVectorizer for bag-of-words representation without including negation features [11].

- With Additional Features: Incorporating additional semantic features from SenticNet and Framester resulted in marginal improvements in accuracy.

4.2.6. BERT

- Baseline Model: The baseline BERT model showed signs of overfitting, with performance peaking early and declining in later epochs.

- With Regularization: Implementing regularization techniques, such as dropout and early stopping, mitigated overfitting and improved generalization, achieving an accuracy of 68% [14].

4.2.7. Long Short-Term Memory

- Baseline Model: The baseline LSTM model achieved an accuracy of 61%.

- With Extended Feature Set: Incorporating the extensive feature set, including semantic and sentiment features, improved the accuracy but also introduced challenges in training due to the increased complexity of the feature space [16].

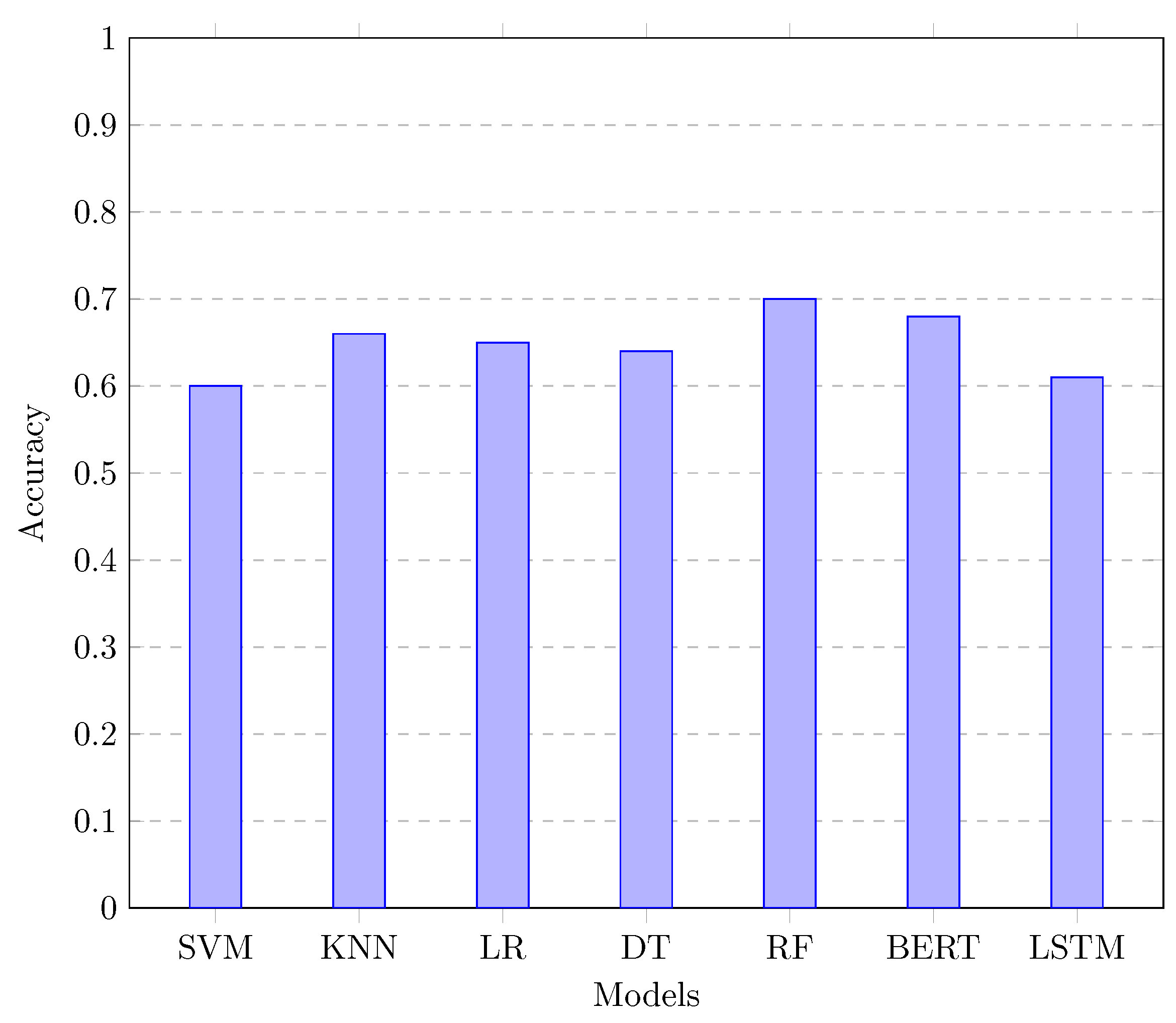

4.2.8. Model Performance Comparison

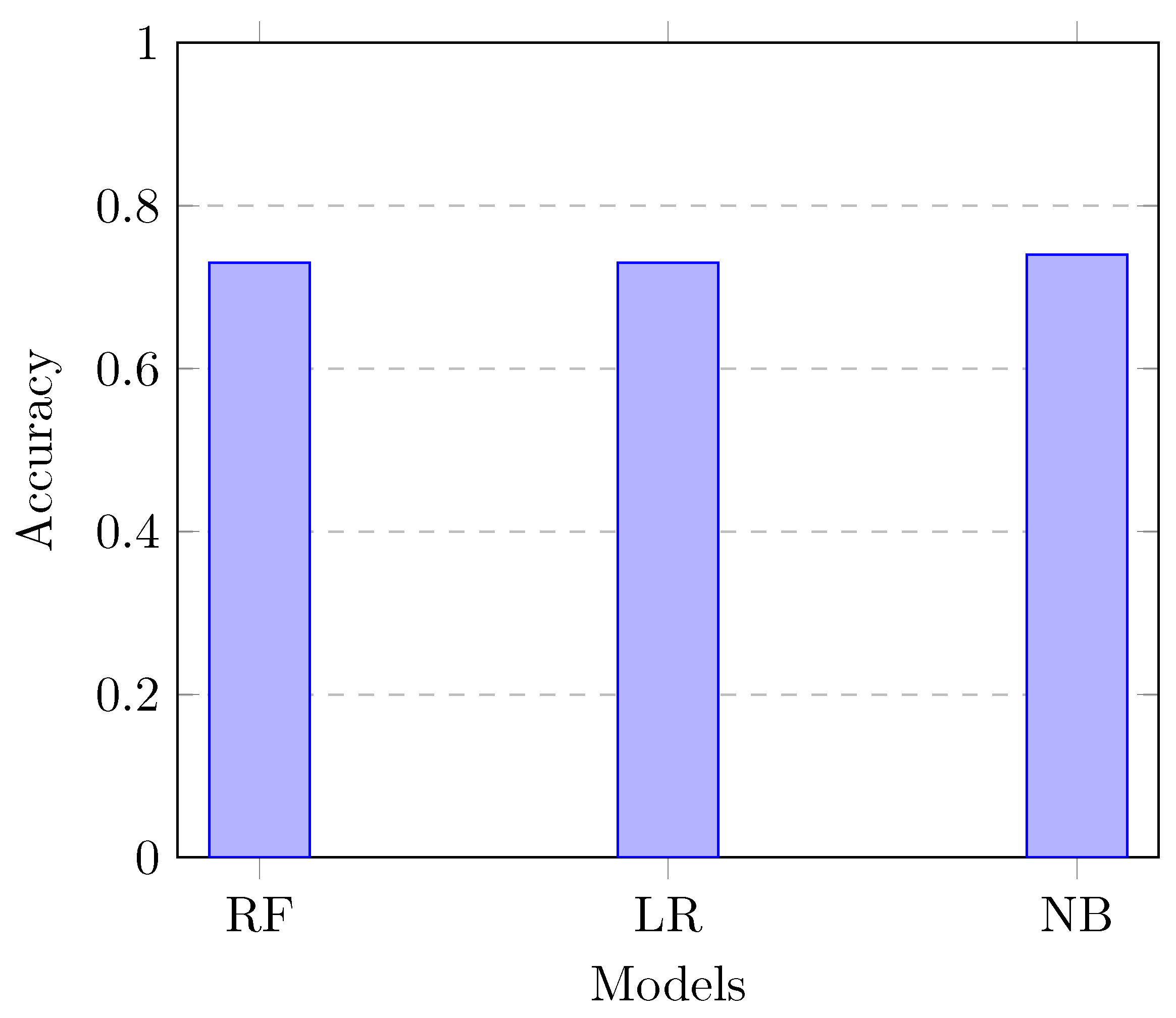

4.3. Classification Task 2: Sarcasm vs Irony

- Random Forest: The model achieved an accuracy of 73% by leveraging ensemble learning to improve robustness and accuracy [11].

- Logistic Regression: With careful feature engineering and negation handling, the logistic regression model also achieved an accuracy of 73% [26].

- Naive Bayes: The Naive Bayes model showed the best performance with an accuracy of 74%, benefiting from its probabilistic approach to text classification [31].

4.3.1. Performance Comparison of Traditional Models

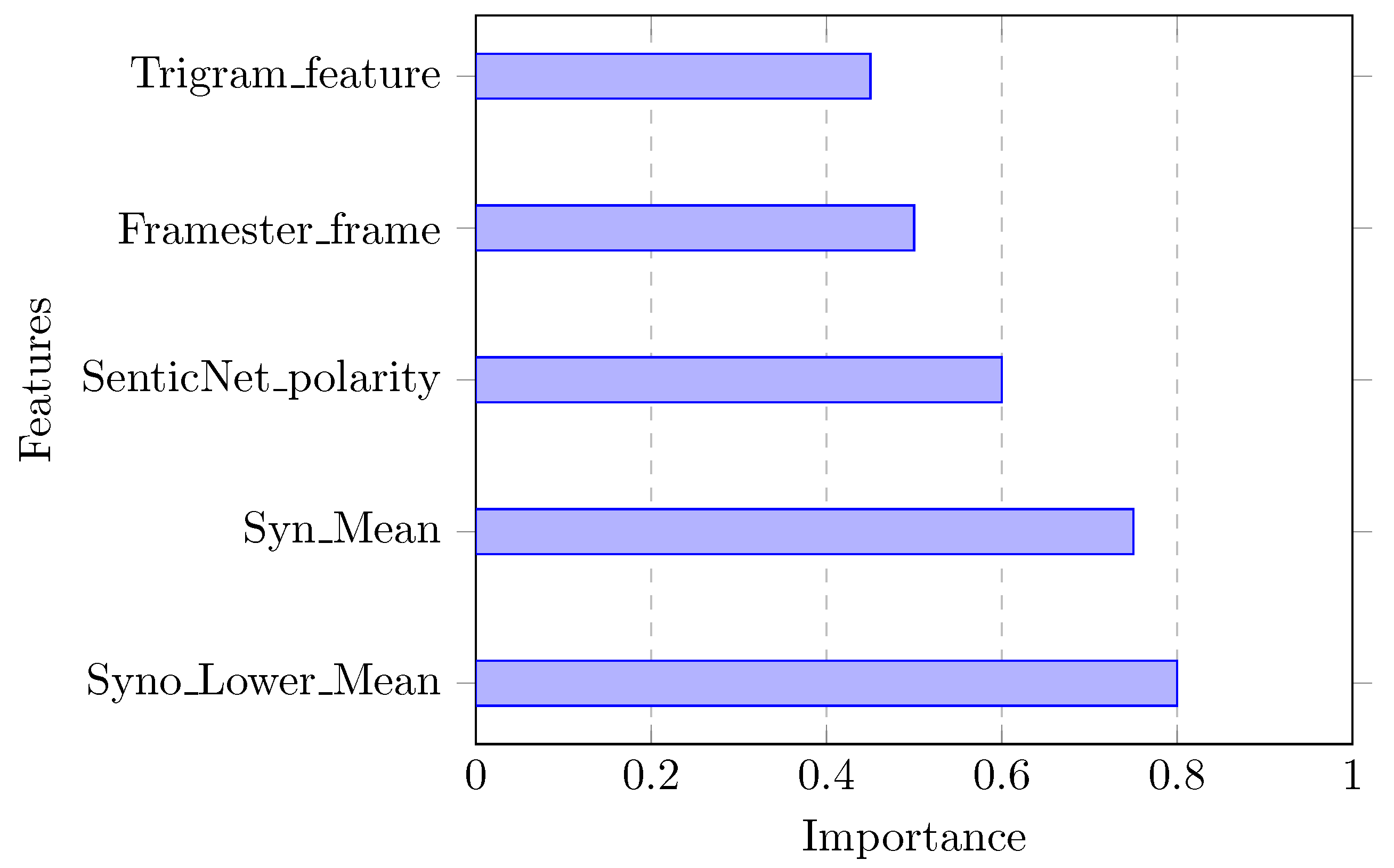

5. Feature Importance Analysis

5.1. Decision Tree Feature Importance

5.2. Support Vector Machines (SVM) Feature Importance

5.3. Implications of Feature Importance Analysis

5.4. Concluding Remarks on Feature Importance Analysis

6. Conclusions and Future Work

- Effectiveness of Novel Features: The introduction of Syno_Lower_Mean and Syn_Mean features had a substantial impact on the model’s performance. These features, which quantify the use of less common synonyms and the mean frequency of synonyms for each word in a tweet, provided valuable semantic insights that enhanced the classification accuracy. The decision tree-based feature selection technique confirmed the high importance of these features.

- Importance of Semantic Enrichment: Leveraging semantic resources like SenticNet and Framester proved to be highly beneficial. SenticNet provided sentiment-related information that helped capture the emotional context of tweets, while Framester offered frame semantics and conceptual relations that enriched the feature set. The integration of these semantic features resulted in better detection of figurative language, as evidenced by the improved performance of models that included these features.

- Handling Class Imbalance: Addressing class imbalance through techniques like random subsampling was crucial for improving model performance. Imbalanced datasets can lead to biased models that favour the majority class, reducing the overall classification accuracy. By implementing random subsampling, we ensured that the models were trained on balanced datasets, which enhanced their ability to detect figurative language accurately.

- Comparison of Classification Models: Among the various classification models tested, Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy for figurative language detection, followed closely by BERT and Logistic Regression. Traditional machine learning models like SVM and KNN also performed well, particularly when semantic features were included. The performance of these models underscores the importance of combining traditional machine learning techniques with advanced feature engineering and deep learning approaches.

6.1. Detailed Analysis of Experimental Results

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): SVM models were evaluated under three scenarios, revealing the critical role of class weighting and feature selection. The scenario with adjusted class weights (0: 0.85, 1: 0.7) showed a marked improvement in F1-Score, demonstrating the effectiveness of addressing class imbalance. Additionally, using only the novel features Syn_Lower_Mean and Syn_Mean with class weights (0: 0.35, 1: 0.4) yielded comparable performance, highlighting the significance of these features in detecting figurative language.

- k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): The KNN model’s performance improved significantly with the inclusion of SenticNet information, achieving an accuracy of 0.66. This result indicates that semantic features play a vital role in enhancing the model’s ability to capture contextual nuances, thereby improving the classification of figurative language.

- Logistic Regression: Logistic Regression showed notable improvements when negation handling techniques were incorporated. The baseline model achieved an accuracy of 55%, which increased to 65% with the addition of negation handling. This finding underscores the importance of addressing linguistic nuances, such as negations, to improve model performance in text classification tasks.

- Decision Tree Classifier: The Decision Tree classifier maintained comparable accuracy when using only the novel features, Syno_Lower_Mean and Syn_Mean. This result demonstrates the robustness of these features in capturing essential semantic information. The model’s performance underscores the potential of innovative feature engineering techniques to enhance text classification.

- Random Forest: Random Forest emerged as the best-performing model, achieving an accuracy of 70% with the CountVectorizer representation. The inclusion of additional semantic features from SenticNet and Framester resulted in marginal improvements, indicating that the model’s robustness and ensemble learning capabilities played a significant role in its high performance.

- BERT: BERT’s performance highlighted the challenges of overfitting in deep learning models. The baseline model showed signs of overfitting, which were mitigated by implementing regularization techniques such as dropout and early stopping. With these adjustments, BERT achieved an accuracy of 68%, demonstrating its potential for capturing complex semantic relationships in text data.

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): The LSTM model faced challenges with the extensive feature set, achieving an accuracy of 61%. Despite these challenges, the model benefited from the semantic features, indicating the importance of further refinement and optimization to fully leverage the potential of LSTM in text classification tasks.

- Sarcasm vs. Irony Classification: For the task of classifying sarcasm versus irony, traditional models like Random Forest, Logistic Regression, and Naive Bayes performed exceptionally well, achieving accuracies of 73%, 73%, and 74%, respectively. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of probabilistic and ensemble learning approaches in handling nuanced language detection tasks.

6.2. Implications and Broader Applications

6.3. Future Research Directions

- Enhanced Feature Engineering: Further exploration of innovative feature engineering techniques is warranted. Future research could focus on developing additional semantic features, such as contextual embeddings and syntactic patterns, to capture more complex language nuances.

- Advanced Semantic Enrichment: The integration of more sophisticated semantic resources, such as knowledge graphs and contextualized word embeddings (e.g., ELMo, GPT-3), could provide richer semantic context and improve classification accuracy. Investigating the use of multi-modal data, such as images and videos, alongside textual data, could also enhance the detection of figurative language.

- Deep Learning Optimization: Optimizing deep learning models like BERT and LSTM through advanced regularization techniques and hyperparameter tuning could mitigate overfitting and improve generalization. Exploring hybrid models that combine traditional machine learning algorithms with deep learning approaches may also yield superior performance.

- Explainability and Interpretability: Enhancing the interpretability of text classification models remains a critical area of research. Developing explainability frameworks that provide clear and intuitive insights into model decisions will facilitate the adoption of these models in real-world applications. Techniques such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) could be explored to improve model transparency.

- Real-World Applications: Applying the methodologies developed in this study to real-world applications, such as social media monitoring, customer feedback analysis, and automated content moderation, will validate their effectiveness and robustness. Collaborations with industry partners could provide valuable data and practical insights, further enhancing the relevance and impact of this research.

6.4. Concluding Remarks

References

- Manning, C.D.; Raghavan, P.; Schütze, H. Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Cambria, E.; Poria, S.; Hazarika, D.; Kwok, K. SenticNet 3: a common and common-sense knowledge base for cognition-driven sentiment analysis. AAAI 2014, 31, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, B. Deep learning for sentiment analysis: A survey. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2018, 8, e1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Feature engineering and selection: A practical approach for predictive models. SAS Institute Inc 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cambria, E.; Poria, S.; Gelbukh, A.; Thelwall, M. SenticNet 6: Ensemble application of symbolic and subsymbolic AI for sentiment analysis. Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (CIKM) 2020.

- Esuli, A.; Sebastiani, F. Sentiwordnet 3.0: an enhanced lexical resource for sentiment analysis and opinion mining. Proceedings of the Seventh conference on International Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’10), 2010.

- Navigli, R. A quick tour of word sense disambiguation, induction and related approaches. Springer-Verlag 2012, 5, 273–309. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, R.W. On the psycholinguistics of sarcasm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 1986, 115, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardo, S. Irony markers and functions: Towards a goal-oriented theory of irony and its processing. Rask 2000, 12, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Joachims, T. Text categorization with support vector machines: Learning with many relevant features. Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Machine Learning (ECML’98), 1998.

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, N. An introduction to kernel and nearest-neighbor nonparametric regression. The American Statistician, 1992.

- Qun, Z.; Zhen, X. A novel approach to combine the predictions of different neural networks. 2008 International Conference on Neural Networks and Signal Processing, 2008, pp. 383–386.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers), 2018, pp. 4171–4186.

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, J.; Wang, Q. Sentiment analysis of Twitter data. International Journal of Computer Applications 2013, 88, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Go, A.; Bhayani, R.; Huang, L. Twitter sentiment classification using distant supervision. CS224N Project Report, Stanford, 2009, Vol. 1, p. 2009.

- Cambria, E.; Poria, S.; Hazarika, D.; Kwok, K. SenticNet 5: Discovering conceptual primitives for sentiment analysis by means of context embeddings. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-16), 2016.

- Gangemi, A.; Presutti, V.; Recupero, D.R.; Nuzzolese, A.G.; Draicchio, F.; Mongiovì, M. Framester: A wide coverage linguistic linked data hub. The Semantic Web. ESWC 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2016, Vol. 9678, pp. 239–254.

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of artificial intelligence research 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Z.S. Distributional structure. Word 1954, 10, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Hart, P.E. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE transactions on information theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer Jr, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied logistic regression; John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Machine learning 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. Journal of machine learning research 2003, 3, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Craven, M.; Shavlik, J.W. Extracting tree-structured representations of trained networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 1996, pp. 24–30.

- Ghosh, D.; Veale, T.; Magnini, B.; Basile, V. SemEval-2015 Task 11: Sentiment Analysis of Figurative Language in Twitter. Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval 2015), 2015, pp. 470–478.

- McCallum, A.; Nigam, K. A comparison of event models for naive bayes text classification. AAAI-98 workshop on learning for text categorization, 1998, Vol. 752, pp. 41–48.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).