1. Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most prevalent primary intraocular malignancy in adults [

1]. Within 15 years following diagnosis, between a third and half of all patients succumb to metastatic disease, irrespective of whether they undergo primary treatment with plaque brachytherapy or surgical enucleation [

2,

3,

4]. This may be explained by the early spread of small tumor deposits, known as micrometastases, from the eye to distant organs, primarily the liver[

5]. Once these clusters of tumor cells evolve into larger, radiologically detectable masses, median survival is approximately one year [

6]. Unlike cutaneous melanoma, treatments involving immune checkpoint and BRAF inhibition have shown limited efficacy in extending survival for those with metastasized uveal melanoma [

7]. There is therefore a need for improved treatment options which lower the risk for systemic disease.

Since macrometastases are uncommon at diagnosis, predicting the prognosis for individual patients relies on clinical and histological aspects of the primary tumor. These factors include tumor location, size, and configuration as well as tumor cell type and the presence of genetic mutations or chromosomal abnormalities [

8]. Primary uveal melanomas consist of four cell types; normal; spindle A; spindle B; and epithelioid cells where the last-mentioned has lower expression levels of the BRCA-1 associated protein (BAP-1)[

9]. The BAP-1 gene is located on chromosome 3p21.1 and is involved in epigenetic modulation of chromatin, DNA- and cell repair as well as tumor growth suppression [

10,

11,

12]. It is one of the genes mutated in uveal melanoma, often occurring in later stages of the disease with low nuclear BAP immunoreactivity being significantly associated with a higher incidence of metastasis [

13]. Inactivating mutations of BAP-1 have been associated with monosomy 3 where protein absence requires biallelic changes through the loss of a copy on chromosome 3 and mutations of the remaining copy [

14]. Monosomy 3 is related to poor prognosis of uveal melanoma regarding survival after treatment, suggesting a potential tumor suppressing role of chromosome 3[

15]. Furthermore, there appears to be a correlation between BAP-1 inactivation and the presence of the epithelioid cell type in primary tumors where epithelioid-mixed cell types are associated with worse prognosis [

14].

Melatonin is a hormone that has been found to have therapeutic benefits in patients with cancer [

16]. The indoleamine is primarily produced in the pineal gland and secreted into the bloodstream and cerebrospinal fluid in the evening[

17,

18]. In addition to regulating the circadian rhythm, melatonin impacts several other bodily functions, has been described as a potent free radical scavenger and appears to aid in DNA repair [

19,

20]. Moreover, melatonin contributes to immune system enhancement through promotion of T-helper cells and regulation of the maturation of immune cells including T-, NK-, and B-cells [

21]. When used as an adjuvant treatment for various types of cancer in previous studies, melatonin has been associated with inhibited tumor growth, increased one-year survival, and few side effects. The hormone has been shown to have low toxicity on its own while reducing the toxicity of chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments [

22,

23,

24].

In regard to the potential therapeutic effect in uveal melanoma, however, research is limited. Past studies have demonstrated that melatonin inhibits growth of cultured human uveal melanoma cells, however the mechanism by which this occurs is not fully understood [

25,

26]. In this study, we examine the expression of melatonin receptors in uveal melanoma tumors from two separate cohorts. We identified the presence of four receptors including the two main melatonin receptors MTNR1A and MTNR1B as well as RORα and NQO2. Higher levels of MTNR1A were found in patients who died of UM, however, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed no difference in the survival curves as they related to receptor expression in either cohort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim of the Study

This study aimed to explore expression levels for melatonin receptors in primary uveal melanoma and investigate a potential correlation between receptor expression and the risk for uveal melanoma related mortality as well as other prognostic factors such as BAP1 expression, cell type, and monosomy 3. If melatonin influences the progression of uveal melanoma and slow the onset of macrometastases, one potential mechanism could be through binding melatonin receptors present in primary uveal melanoma cells.

2.2. Patients and Samples

In order to determine expression levels of melatonin receptors in uveal melanoma, data was collected from both The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) as well as from immunohistochemically stained tissues from the ocular pathology archive at St. Erik Eye Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden (

Table 1). Within the Swedish population of 10 million, all uveal melanomas are diagnosed at this hospital, allowing access to extensive clinical and survival data with minimal loss to follow-up. St. Erik Eye Hospital is also the nation’s only laboratory for ocular pathology, with an extensive archive of almost all eyes and periocular tissues that have been surgically removed and examined since the 1960’s.

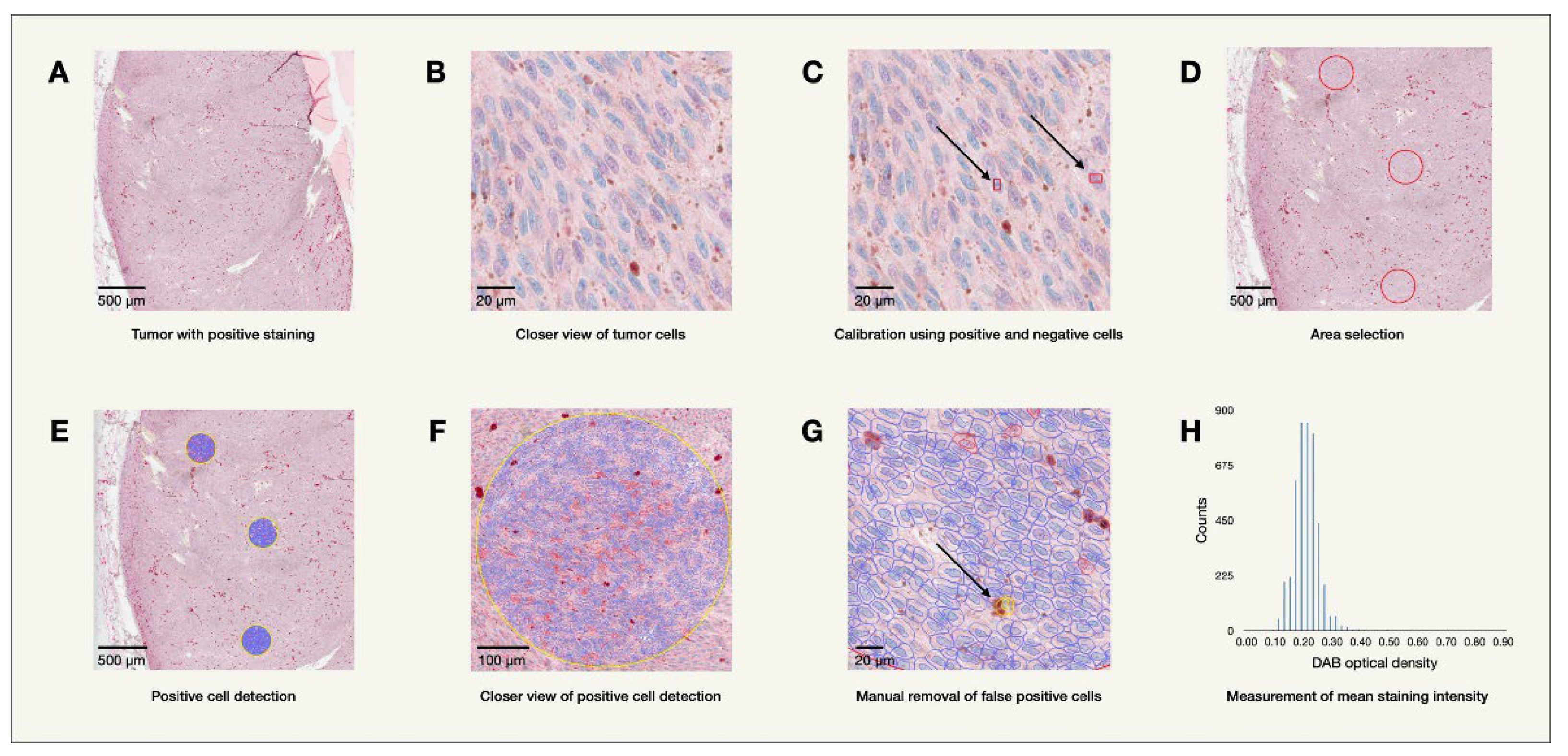

48 enucleated eyes containing primary uveal melanoma tumors from the years 2000-2008 were collected from the archives of the St. Erik Ophthalmic Pathology Laboratory for this study. One eye was later excluded as medical records revealed the tumor originated from the conjunctiva. Formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue from the enucleated eyes were sectioned and stained on a BOND III IHC stainer by biomedical analysts using mouse monoclonal antibodies. The stained tissue sections were then digitally scanned using a Grundium Ocus 40 digital slide scanner (Grundium Oy, Tampere, Finland). Mean levels of immunohistochemical expression of MTNR1A and MTNR1B across all tumor cells, as determined by their optical staining density in bioimage analysis (MTNR1A OD, MTNR1B OD), were analyzed using the program QuPath Bioimage analysis v. 0.4.1 m4 (Bankhead et al., 2017) as illustrated in

Figure 1. Clinicopathological patient follow-up data including information regarding potential metastasis and cause of death was collected from patient charts and treatment registers.

Data was also gathered from a second cohort comprised of 80 uveal melanoma patients from TCGA via the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA. The 2017 publication by Robertson et al. provided anonymized patient and tumor information, including whole exome sequencing results, in the supplementary materials [

27]. This information was downloaded to evaluate RNA sequencing data, measured in transcripts per million (TPM), for the receptors MTNR1A, MTNR1B, RORα, GPR50, and NQO2, and its relation to UM-related death and prognostic factors including tumor cell type, BAP1 mutation, and monosomy 3.

2.3. Melatonin Receptors

2.3.1. MTNR1A (MT1) and MTNR1B (MT2)

Melatonin impacts various processes in the human body primarily through two membrane receptors; melatonin receptor type 1A (MTNR1A) and melatonin receptor type 1B (MTNR1B) [

28]. Both of these receptors are G-coupled receptor proteins widely expressed both centrally and peripherally throughout the human body and play a role in melatonin’s impact on physiological systems such as circadian rhythm, neurodevelopment, blood glucose regulation and the cardiovascular system [

29,

30]. In a study published in 2000, Roberts

et al. identified the MTNR1B subtype, but not the MTNR1A subtype, in reverse-transcribed RNA obtained from normal uveal melanocytes as well as melanoma cell lines [

31]. In the study, receptor agonists for both MTNR1A and MTNR1B as well as melatonin itself inhibited the growth of uveal melanoma cells at physiological concentrations, thereby suggesting a receptor-mediated mechanism for the inhibition of tumor cell growth [

31]. MTNR1B appeared to be expressed to a larger extent in the cancerous cell lines compared to normal uveal melanocytes, though this observation was not specifically verified [

31].

2.3.2. NQO2

N-ribosyldihydronicotinamide:quinone oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2) presents a melatonin binding site known as MT3 and carries out two-electron reductions of primarily quinones [

32,

33]. Despite previously being considered a detoxifying enzyme, some studies suggest that NQO2 activation leads to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the enzyme has been found to be increased in some cancer cell lines [

34,

35]. Of note, the affinity of NQO2 to melatonin seems to be in the nanomolar range, however, melatonin appears to inhibit the enzyme within the micromolar range, where concentrations above 1 μM are considered pharmacological [

33].

2.3.3. GPR50

GPR50 is a G protein-coupled receptor with the ability to heterodimerize with both MTNR1A and MTNR1B [

36]. GPR50 does not seem to modify the function of MTNR1A but rather leads to an inhibition of the functional response of the receptor to stimulation by melatonin [

36].

2.3.4. RORα

The retinoic acid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORα) is a nuclear receptor within the ROR family [

37]. RORα has been found to play a role in the immune system by contributing to Th17 development and the generation of innate lymphoid cells [

38,

39]. It may also aid in the stabilization and transcription of p53 [

40]. Several studies suggest that RORα expression is down-regulated during tumor development and progression, while exogenous RORα inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth in colorectal, prostate and breast cancer [

41,

42,

43]. Whether a correlation between melatonin and the ROR family exists is still debated [

44]. Earlier studies suggested that melatonin acts as a ligand to RORα, though a later study found this does not occur in a high-affinity manner [

45,

46]. One study, using crystallography and molecular modeling, indicated that melatonin is unlikely to function as an ROR ligand [

47]. Despite this, specific intermediate steps enabling melatonin to indirectly regulate ROR expression and function have been confirmed [

44].

2.4. Statistical Methods

To compare potential differences in receptor expression as it correlated to uveal melanoma related death, BAP1 mutation, monosomy 3 as well as tumor cell type, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests were employed using GraphPad Prism, version 10.1.1 (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA). Kaplan-Meier survival probability curves were plotted for patients with expression levels below or above the median value, as well as for those with expression levels below or above 1 TPM (transcript per million), using R, version 4.3.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria), including the survival, survminer, ggplot2 and extrafont packages.

The difference in mean MTNR1A OD and MTNR1B OD in the nuclei and cytoplasm of tumor cells was determined for patients who died a UM related death and those who did not. For the Kaplan-Meier analysis, tumors with a mean MTNR1A OD or MTNR1B OD above the median value were compared with tumors with a mean MTNR1A OD or MTNR1B OD equal to or smaller than the median value.

Tumors from the TCGA cohort were considered to express the respective receptors if the mean value was above 1 TPM. Note, the cutoff of 1 TPM for expression was arbitrarily chosen, as used in previous research [

48]. No analyses in relation to the 1 TPM cutoff were conducted for MTNR1B RNA and GPR50 RNA considering that all tumors had TPM of less than 1. Similarly, the 1 TPM cutoff was not used for NQO2 as all tumors had TPM of more than 1. Median TPM values were used as a cutoff in additional analyses for MTNR1A RNA, NQO2 RNA, and RORα RNA. This was not done for MTNR1B RNA or GPR50 RNA as they had a median value of 0.

Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05 and corrected P values were calculated using the Holm-Bonferroni method to limit error due to multiple comparisons for each cohort and prognostic factor. Note that, in the results tables, P values greater than or equal to 0.05 are labeled non-significant (ns), P values less than 0.05 are labeled with *, P values less than 0.01 are labeled with **, and P values less than 0.001 are labeled with ***.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

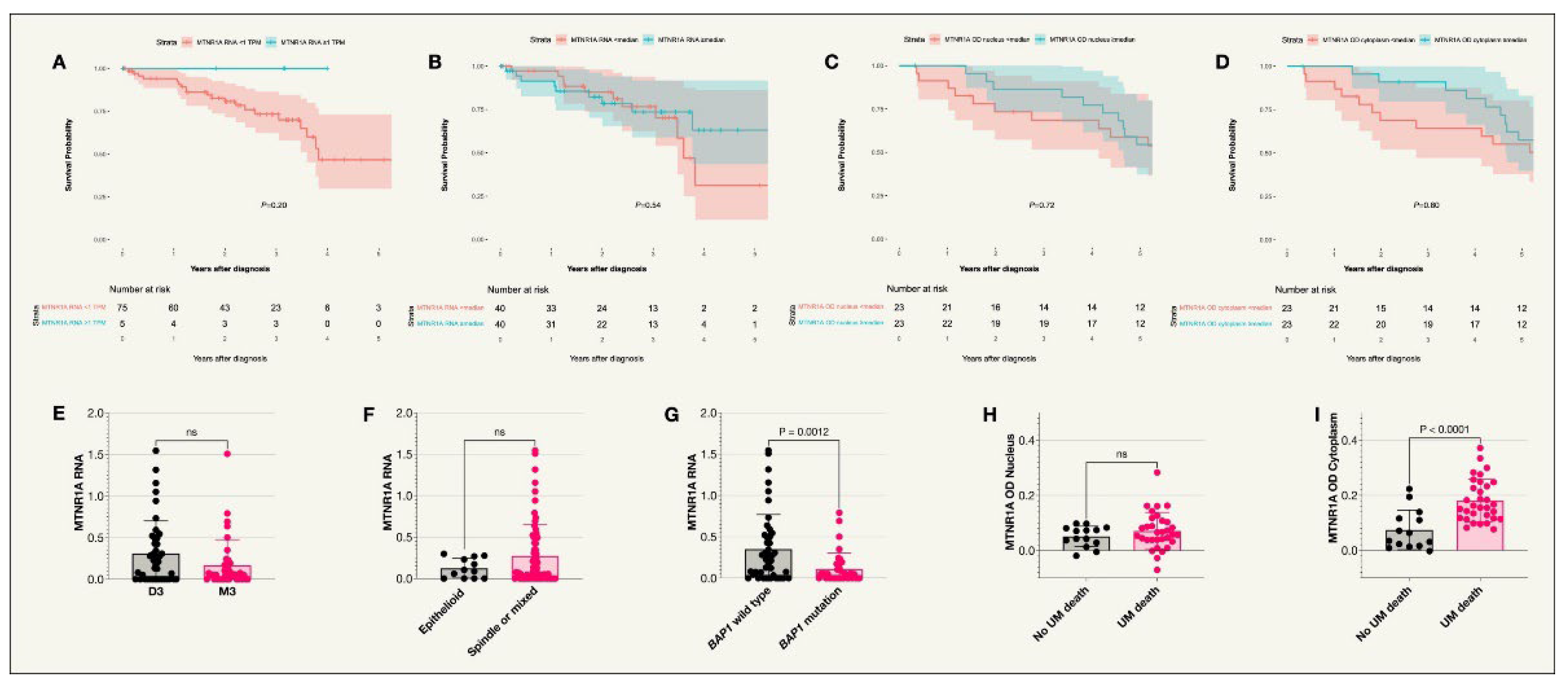

3.2. MTNR1A

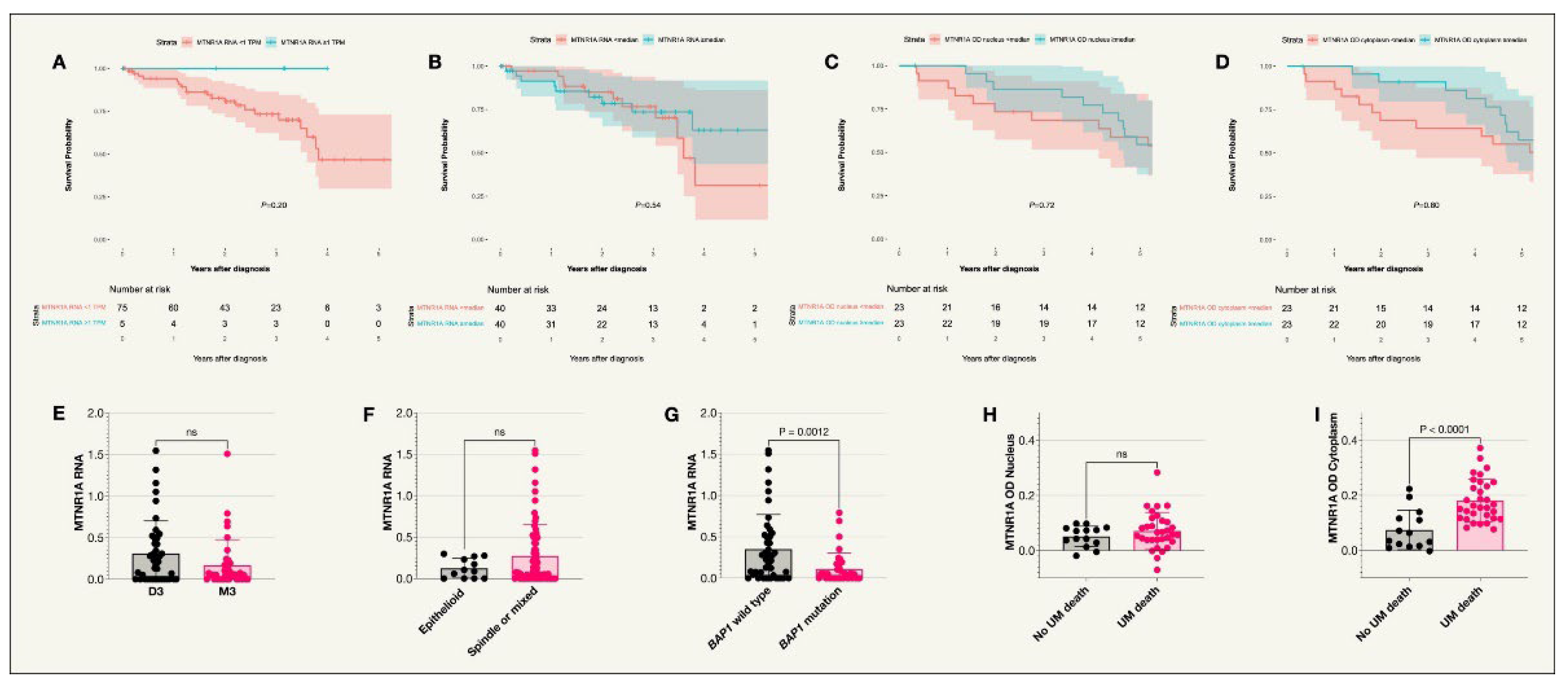

MTNR1A was expressed in uveal melanoma tumors in both the St. Erik and the TCGA cohorts (

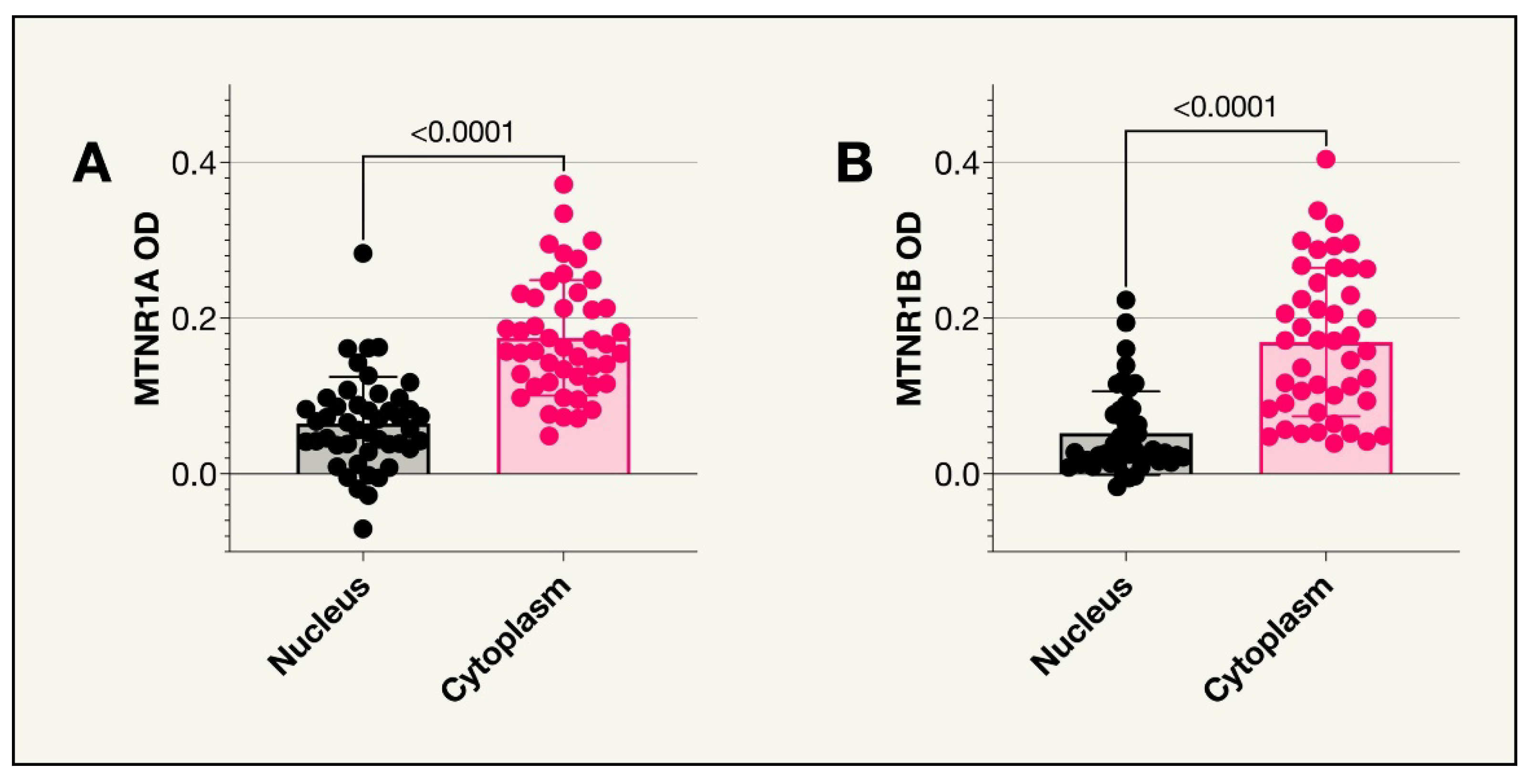

Figure 2). However, no significant difference was seen in survival probability between patients in the TCGA cohort with MTNR1A RNA levels below vs above the median TPM value or below vs above 1 TPM. Similarly, no significant difference was seen in survival probability between patients in the St. Erik cohort with MTNR1A OD values below vs above the median. In the St. Erik cohort, slides were missing for one of the tumors resulting in a total of 46 tumors analyzed. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the median MTNR1A OD was significantly higher in the cytoplasm compared to the nuclei (P<0.001). There was also a higher MTNR1A OD in the cytoplasm of those who died from uveal melanoma compared to those who did not (Holm-Bonferroni corrected P=0.004). No significant difference was seen between UM related death and nuclear MTNR1A OD. In the TCGA cohort, MTNR1A RNA levels were significantly lower in tumors with BAP1 mutations (Holm-Bonferroni corrected P=0.005) while there was no correlation between MTNR1A RNA and Monosomy 3 or cell type (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves and scatter plots for MTNR1A expression. A. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with an MTNR1A RNA expression of less than 1 TPM compared to 1 TPM or above (P=0.20)*, n=80. B. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with an MTNR1A RNA expression less than or equal and above the median value (P=0.54)*, n=80. C. Survival curve comparing the incidence of UM-related death in patients with IHC staining optical densities below or equal to and above the median in the nucleus (P=0.72)+, n=46. D. Survival curve comparing the incidence of UM-related death in patients with IHC staining optical densities below or equal to and above the median in the cytoplasm (P=0.80)+, n=46. E. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A RNA expression in patient tumors with disomy 3 or monosomy 3*. F. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A RNA expression in patients with tumors of an epithelioid cell type compared to other cell types (spindle or mixed)*. G. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A RNA expression in patients with the BAP1 wild type or BAP1 mutation where levels were higher in patients with the BAP1 wildtype (P=0.0012)*. H. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A OD in the nucleus of tumor cells for patients who did or did not die due to uveal melanoma+. I. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A OD in the cytoplasm of tumor cells for patients who did or did not die due to uveal melanoma (P<0.0001)+. Colored fields on the Kaplan-Meier curves indicate 95% confidence intervals. *TCGA cohort, +St Erik cohort.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves and scatter plots for MTNR1A expression. A. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with an MTNR1A RNA expression of less than 1 TPM compared to 1 TPM or above (P=0.20)*, n=80. B. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with an MTNR1A RNA expression less than or equal and above the median value (P=0.54)*, n=80. C. Survival curve comparing the incidence of UM-related death in patients with IHC staining optical densities below or equal to and above the median in the nucleus (P=0.72)+, n=46. D. Survival curve comparing the incidence of UM-related death in patients with IHC staining optical densities below or equal to and above the median in the cytoplasm (P=0.80)+, n=46. E. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A RNA expression in patient tumors with disomy 3 or monosomy 3*. F. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A RNA expression in patients with tumors of an epithelioid cell type compared to other cell types (spindle or mixed)*. G. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A RNA expression in patients with the BAP1 wild type or BAP1 mutation where levels were higher in patients with the BAP1 wildtype (P=0.0012)*. H. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A OD in the nucleus of tumor cells for patients who did or did not die due to uveal melanoma+. I. Scatter plot comparing MTNR1A OD in the cytoplasm of tumor cells for patients who did or did not die due to uveal melanoma (P<0.0001)+. Colored fields on the Kaplan-Meier curves indicate 95% confidence intervals. *TCGA cohort, +St Erik cohort.

Figure 3.

MTNR1A and MTNR1B receptors in the nucleus vs cytoplasm. For both receptors, there were significantly higher mean optical densities in the cytoplasm compared to the nucleus (P<0.0001).

Figure 3.

MTNR1A and MTNR1B receptors in the nucleus vs cytoplasm. For both receptors, there were significantly higher mean optical densities in the cytoplasm compared to the nucleus (P<0.0001).

Table 2A.

Mean RNA expression across cytomorphology.

Table 2A.

Mean RNA expression across cytomorphology.

| Analysis |

Epithelioid,

mean TPM (SD) |

Non-epithelioid,

mean TPM (SD) |

P (Holm-Bonferroni Corrected P Value) |

NQO2 vs epithelioid or non-epithelioid

|

50 (17) |

16) |

* (ns) |

RORA vs epithelioid or non-epithelioid

|

1 (0.8) |

0.9 (1) |

ns (ns) |

GPR50 vs epithelioid or non-epithelioid

|

<0.05 (<0.05) |

<0.05 (<0.05) |

ns (ns) |

MTNR1B vs epithelioid or non-epithelioid

|

0 (0) |

<0.05 (<0.05) |

ns (ns) |

MTNR1A vs epithelioid or non-epithelioid

|

0.1 (0.1) |

0.3 (0.4) |

ns (ns) |

Table 2B.

Mean RNA expression for monosomy 3 vs disomy 3.

Table 2B.

Mean RNA expression for monosomy 3 vs disomy 3.

| Analysis |

Monosomy 3,

mean TPM (SD) |

Disomy 3,

mean TPM (SD) |

P (Holm-Bonferroni Corrected P Value) |

NQO2 vs M3 or D3

|

41 (18) |

36 (15) |

ns (ns) |

RORA vs M3 or D3

|

1 (1) |

0.9 (1) |

ns (ns) |

GPR50 vs M3 or D3

|

<0.05 (<0.05) |

<0.05 (<0.05) |

ns (ns) |

MTNR1B vs M3 or D3

|

<0.05 (<0.05) |

0 (<0.05) |

ns (ns) |

MTNR1A vs M3 or D3

|

0.4 (0.3) |

0.3 (0.2) |

ns (ns)

|

Table 2C.

Mean RNA expression for BAP1 mutation or wildtype.

Table 2C.

Mean RNA expression for BAP1 mutation or wildtype.

| Analysis |

BAP1 mutation,

mean TPM (SD) |

BAP1 wildtype,

mean TPM (SD) |

P (Holm-Bonferroni Corrected P Value) |

NQO2 vs BAP1 mutation or wildtype

|

41 (17) |

36 (16) |

ns (ns) |

RORA vs BAP1 mutation or wildtype

|

1.1 (1.1) |

0.9 (0.9) |

ns (ns) |

GPR50 vs BAP1 mutation or wildtype

|

<0.05 (<0.05) |

<0.05 (<0.05) |

ns (ns) |

MTNR1B vs BAP1 mutation or wildtype

|

<0.05 (<0.05) |

<0.05 (<0.05) |

ns (ns) |

MTNR1A vs BAP1 mutation or wildtype

|

0.1 (0.2) |

0.4 (0.4) |

*** (***) |

Table 3.

Mean DAB Optical Density (OD) for UM-related death or non-UM related death.

Table 3.

Mean DAB Optical Density (OD) for UM-related death or non-UM related death.

| Analysis |

UM-related death,

mean DAB OD (SD) |

No UM-related death,

mean DAB OD (SD) |

P (Holm-Bonferroni Corrected P Value) |

MTNR1A OD in Nucleus and UM death

|

0.07 (0.07) |

0.05 (0.04) |

ns (ns) |

MTNR1A OD in Cytoplasm and UM death

|

0.18 (0.08) |

0.16 (0.07)

|

*** (**) |

| MTNR1B OD in Nucleus and UM death |

0.04 (0.04) |

0.07 (0.07)

|

ns (ns) |

| MTNR1B OD in Cytoplasm and UM death |

0.16 (0.09) |

0.20 (0.11)

|

ns (ns) |

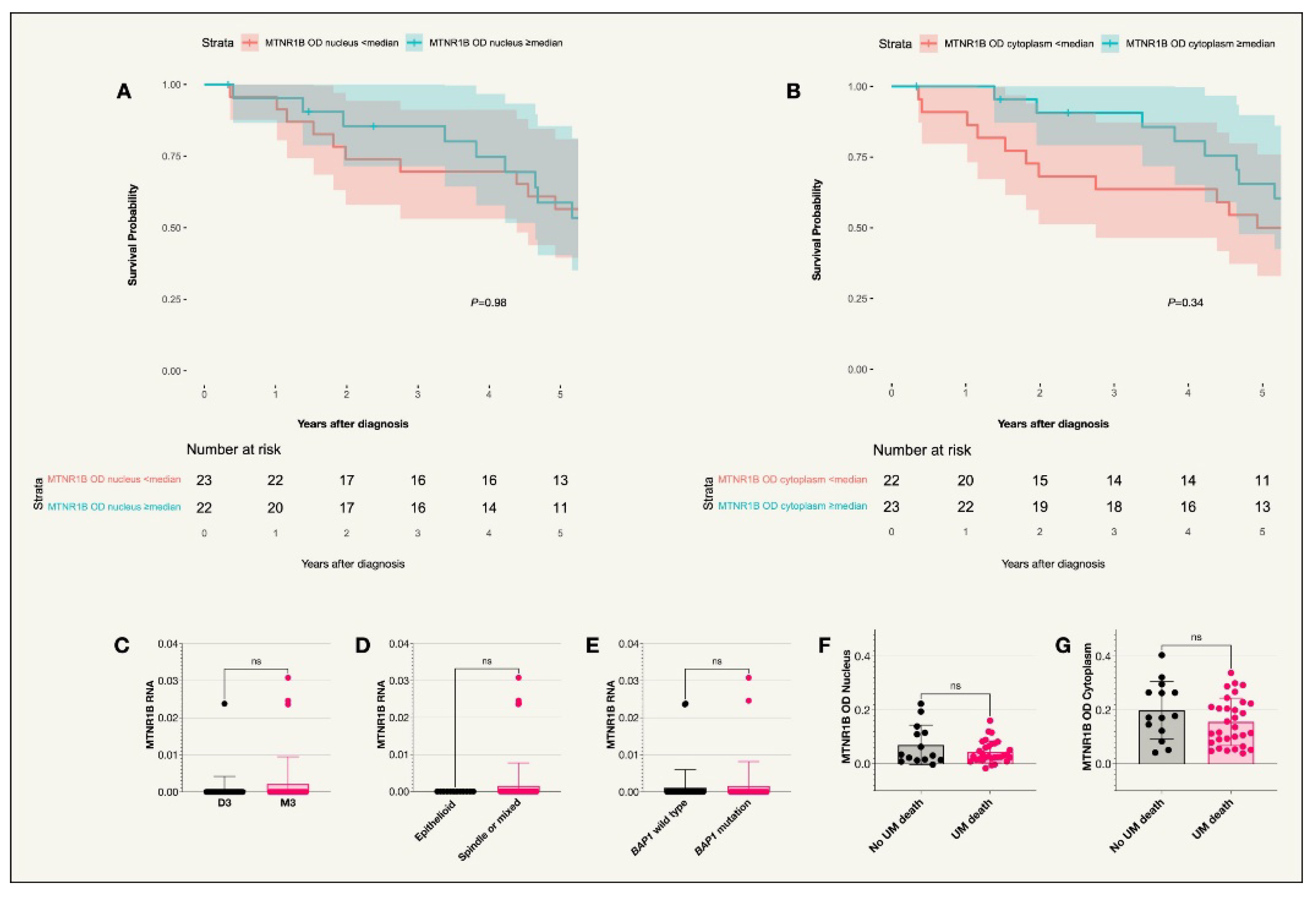

3.3. MTNR1B

No tumors from the TCGA data expressed MTNR1B. In the St. Erik cohort, expression levels were analyzed in the nuclei and cytoplasm of 45 tumors due to missing slides. As in the case of MTNR1A, the median MTNR1B OD was significantly higher in the cytoplasm compared to the nuclei (P<0.001). No significant difference was seen between receptor expression and survival probability. Similarly, no correlation was observed between UM related death and OD levels in the cytoplasm or nucleus (

Figure 4,

Table 2 and

Table 3).

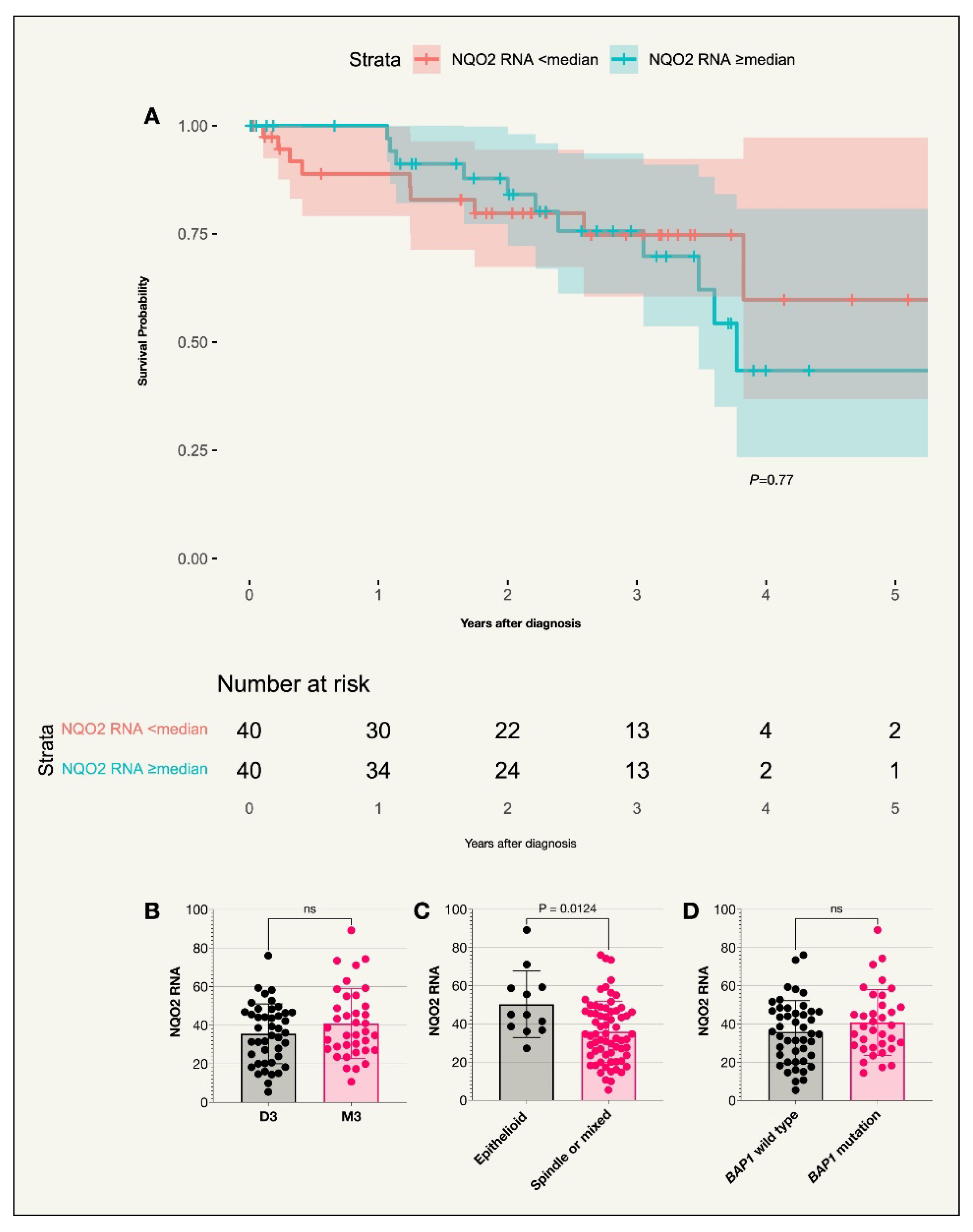

3.4. NQO2

The median NQO2 RNA expression levels for the 80 tumors in the TCGA data was 36.37 TPM. There was no correlation between receptor expression and survival probability (

Figure A1). Interestingly, NQO2 RNA expression was higher in patients with epithelioid tumors compared to those with either spindle or mixed cell types (P=0.01). However, after the Holm-Bonferroni correction, the result was no longer significant (corrected P=0.05). Similarly, when comparing NQO2 RNA expression levels across the three separate cell types, i.e.

, epithelioid, spindle and mixed, using the Kruskal-Wallis test, the original P value was significant (P=0.0468) while the Holm-Bonferroni corrected P value was not (corrected P=0.234). No other correlation was noted for other prognostic factors (

Table 2).

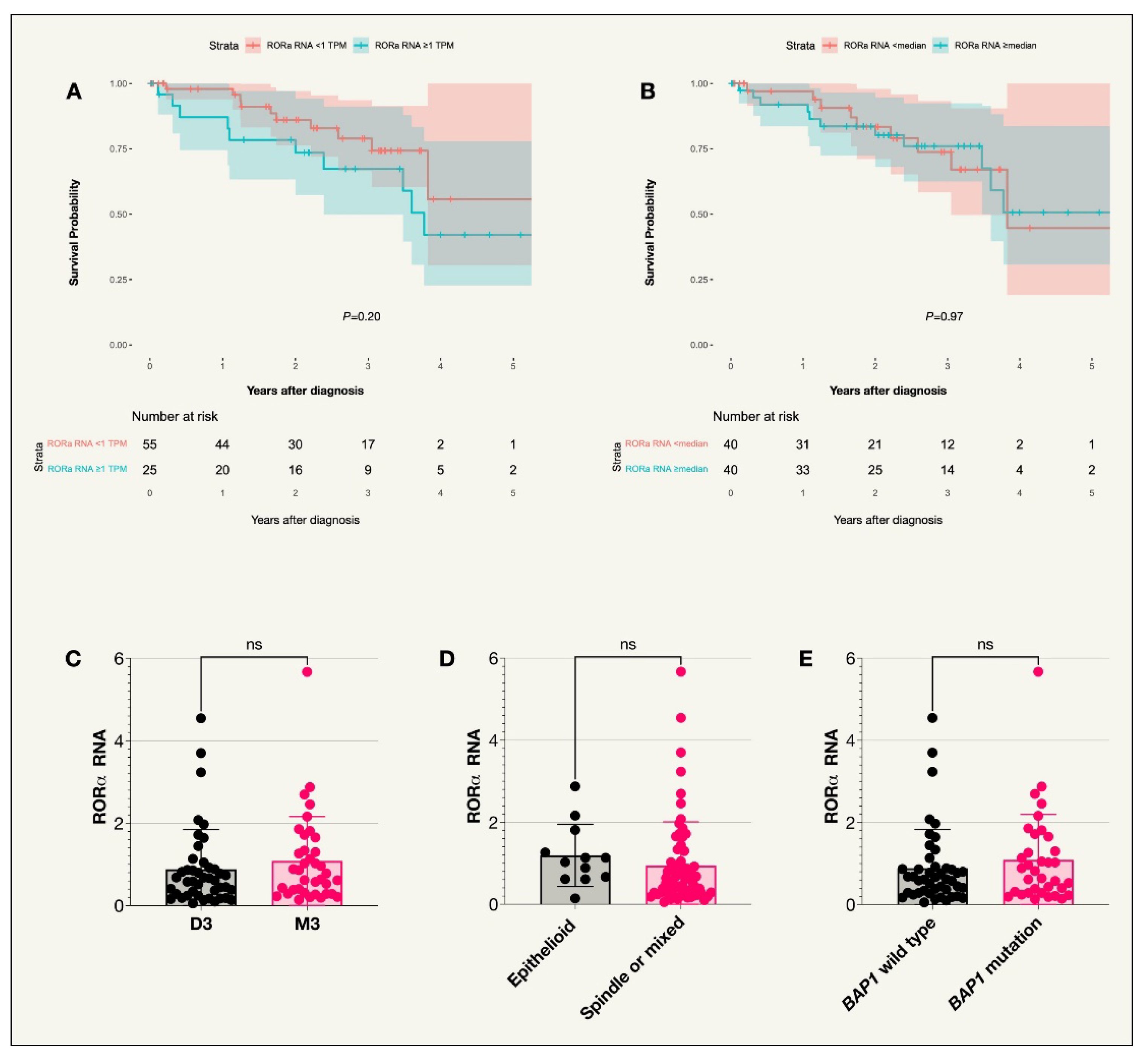

3.5. RORα

The median RNA expression level of RORα among the 80 tumors in the TCGA data was 0.66 TPM. 25 patients had an RNA expression level equal to or above 1 TPM while 55 patients had an expression level below 1 TPM. No correlation between expression and survival probability or prognostic factors was noted (

Figure A2,

Table 2).

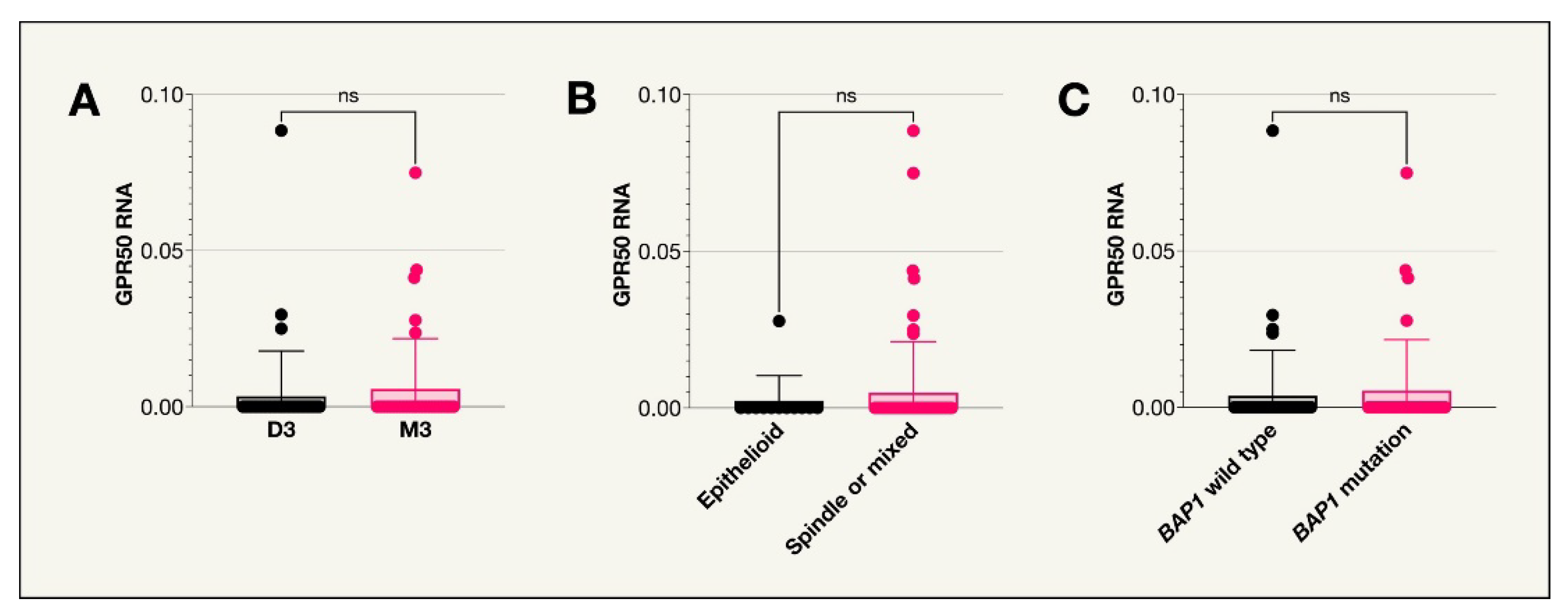

3.6. GPR50

No tumors from the TCGA data expressed GPR50 i.e.

, the median the expression level was 0 TPM with no tumors having a mean RNA expression level over 1 TPM (

Figure A3). There were therefore no observed correlations to UM survival or any of the included prognostic factors (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

The objective of this research was to assess the expression levels of melatonin receptors in primary uveal melanoma and explore potential associations between receptor expression and the likelihood of uveal melanoma-related mortality. A key finding of this study is the presence of MTNR1A expression in uveal melanoma tumors in both the St. Erik and the TCGA cohorts. This, to the knowledge of the authors, is the first investigation of MTNR1A in human uveal melanoma tissue. As mentioned, one previous study has found the expression of MTNR1B in a uveal melanoma cell line [

31]. The current study confirms this earlier finding. In the St. Erik cohort, these main melatonin receptors were minimally expressed, however, the mean value for expression in the cytoplasm was significantly higher than in the nuclei (P<0.0001) for both MTNR1A OD and MTNR1B OD. This likely corresponds to the fact that both receptors are transmembrane receptors and are therefore more likely to be present in the cytoplasm.

MTNR1A OD levels in the cytoplasm of UM cells were significantly higher in patients who died of UM compared to those who did not. Other studies investigating immunohistochemically stained tissues from other cancer types have found similar results with higher levels of MTNR1A in the tumors of patients with more advanced stages and worse prognosis [

49,

50]. One hypothesis for this observation, mentioned by Wang et al., is that melatonin levels appear to be lower in cancer patients compared to healthy individuals and even lower in those with more advanced cancer stages. This may in turn trigger a feedback mechanism where melatonin receptor expression is upregulated leading to increased levels of MTNR1A [

49].

Nevertheless, there was no difference in receptor expression in more aggressive tumors compared to less aggressive tumors as illustrated by the Kaplan-Meier analyses for both the St. Erik and TCGA cohort. Moreover, as the overall expression of MTNR1A in UM cells was relatively low, it is difficult to draw specific conclusions regarding this finding. Furthermore, tumors with the BAP1 mutations in the TCGA cohort had significantly lower MTNR1A RNA expression levels (Holm-Bonferroni corrected P=0.005). This is, however, a preliminary result which should be investigated further.

The current study also confirms the presence of RORα and NQO2 in uveal melanoma cells. While little is known about the physiologic effect of these receptors in uveal melanocyte homeostasis, their very presence in melanoma cells leaves room for potential involvement in the anti-cancer mechanisms of melatonin. NQO2 has been discussed in various models for cancer pathogenesis, and thus, has been considered a potential anti-cancer drug target [

51]. Our study found NQO2 expression to be higher in patients with epithelioid tumors (P=0.01), though the Holm-Bonferroni corrected P value was not significant (P=0.05). Some previous studies have shown that higher levels of NQO2 may be associated with a poorer prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer, where the levels seem to be even higher in patients at a later stage of disease [

52]. Since the epithelioid cell type is associated with worse prognosis, one could speculate that it makes sense for NQO2 to be higher in this group as it is also associated with worse prognosis in other cancers as mentioned above. This is complicated by the ambivalent nature of NQO2 described in the literature. While earlier research highlights NQO2 as a detoxifying molecule, newer findings imply NQO2 as a mediator of increased ROS production and cytotoxicity. It is possible that the degree to which the molecule exerts either role is dependent on tumor stage and polymorphisms [

53]. Melatonin was previously demonstrated to inhibit NQO2 at pharmacological concentrations [

54]. While this study did not find a difference in survival between NQO2 expressing and non-expressing tumors, it is possible to hypothesize that the inhibitory effect is absent in uveal melanoma at endogenous melatonin concentrations. Future studies in patients using melatonin as an adjuvant treatment might shed light on this theory.

As for RORα, despite its role as a nuclear melatonin receptor remaining contested and highly complex, it has been shown that melatonin treatment correlates with increased RORα expression [

44]. While survival was independent of RORα expression in the current study, RORα related anti-tumor mechanisms could potentially be amplified via melatonin at therapeutic doses.

Lastly, while not a direct receptor for melatonin, earlier research suggests that GPR50 modulates the function of MTNR1A which in turn inhibits the response of MTNR1A to binding by melatonin [

36]. No tumors expressed GPR50 in this study, however, considering the potential role of MTNR1A in tumor suppression based on previous research, future studies investigating GPR50 may be of value.

4.2. Context

As previously stated, an earlier study found that MTNR1A and MTNR1B agonists as well as melatonin had a beneficial effect on uveal melanoma cells [

31]. We have shown the presence of these receptors in uveal melanoma, offering a potential mechanism for melatonin’s oncostatic properties. While this study did not show a clear correlation between melatonin receptor expression and survival in uveal melanoma patients, the hormone itself may exert its potential anticancer effects via 1) its receptors at pharmacological doses rather than physiological doses 2) mechanisms independent of direct receptor mediated signaling in tumor cells.

Different mechanisms of how this may be achieved have been proposed. Notably, melatonin has been implicated in altering the tumor microenvironment (TME) in different neoplasms [

55]. TME is characterized by an interplay of immune cells, whereby cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) and natural killer (NK) cells are key mediators of tumor suppression. Other cell types like T regulatory cells (Tregs) or M2 macrophages limit the activity of CTLs and NK cells, thus limiting their anticancer activity [

56].

Melatonin receptor mediated regulation of immune responses has been closely studied, and findings suggest that melatonin increases CTL and NK responses, while limiting Treg activity. Furthermore, the role of melatonin as an antioxidant and as a free radical scavenger has been studied extensively. While the amplitude of these effects in vivo is not known, current evidence largely supports that melatonin has the chemical properties of a scavenger molecule [

57]. Thus, modifying TME immune responses and the chemical properties of melatonin in protection from ROS are promising branches via which melatonin can exert its anticancer effects beyond activation of its designated receptors.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

This research involved data collection from two retrospective cohorts, which could potentially introduce biases associated with patient selection as well as the accuracy of the data. This restricts our capacity to draw conclusions regarding causal relationships. Selection bias could be present as the patients included in the study have undergone enucleation, the primary treatment option for larger and more advanced tumors, therefore, they may have a more aggressive variant compared to the general population of patients with UM. One should also take into consideration the inherent limitations of immunohistochemistry which was used to analyze the uveal melanoma tissue from the St. Erik cohort. While IHC is a commonly used technique worldwide, the method is restricted concerning reproducibility, sensitivity, and specificity. Furthermore, receptor expression in the TCGA cohort was analyzed using RNA sequencing data measured in TPM. While TPM measurements provide insights into gene expression at the transcript level, they have limitations when inferring exact protein expression levels. Lastly, while this study evaluates the expression of melatonin receptors in uveal melanoma tissue, it does not investigate their functional significance or downstream effects following activation or inhibition by melatonin. Additional studies are needed to determine potential biological implications of the observed receptor expression.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings confirm the presence of melatonin receptors in uveal melanoma tumors, potentially providing sites for melatonin’s binding or indirect impact. While these receptors suggest a potential mechanism for melatonin’s anti-cancer effects, our study did not establish a clear association between receptor expression and uveal melanoma-related mortality. Further investigation is warranted to explore alternative mechanisms through which melatonin may exert its anti-cancer properties in uveal melanoma, including its role as an antioxidant and free radical scavenger, as well as its potential for TME and immune system modulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and G.S.; methodology, A.H. and G.S.; validation, R.K.O, H.W. and O.A.; formal analysis, A.H. and G.S.; investigation, A.H. and G.S.; resources, A.H. and G.S.; data curation, O.A., A.H. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H., R.K.O, and H.W.; writing—review and editing, R.K.O, H.W., O.A. and G.S.; visualization, A.H. and G.S.; supervision, G.S.; project administration, G.S.; funding acquisition, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Support for this study was provided to Gustav Stålhammar from: Region Stockholm (RS-2019-1138); The Swedish Cancer Society (20 0798 Fk); The Crown Princess Margareta Foundation for the Visually Impaired (2022-017); Karolinska Institutet (2022-01671); The Swedish Eye Foundation (2022-05-09). The sponsors and funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Reference number 2024-00295-02) and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent from the patients in the St. Erik cohort was waived as all included patients were deceased. Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) are de-identified and openly available in the public domain.

Data Availability Statement

The raw, anonymized data from the St. Erik cohort supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request. Data from the TCGA cohort are openly available at

https://www.cancer.gov/tcga.

Acknowledgments

The findings presented in this article partially rely on information produced by the TCGA Research Network, available at

https://www.cancer.gov/tcga.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicting relationship exists for any of the authors.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve and scatter plots for NQO2 expression (TCGA cohort). A. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with an NQO2 RNA expression above or below the median TPM value (P=0.20), n=80. B. Scatter plot comparing NQO2 RNA expression in patient tumors with disomy 3 or monosomy 3. C. Scatter plot comparing NQO2 RNA expression in patients with tumors of an epithelioid cell type compared to other cell types (P= 0.0124). D. Scatter plot comparing NQO2 RNA expression in patients with the BAP1 wild type or BAP1 mutation. Colored fields on the Kaplan-Meier curve indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure A1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve and scatter plots for NQO2 expression (TCGA cohort). A. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with an NQO2 RNA expression above or below the median TPM value (P=0.20), n=80. B. Scatter plot comparing NQO2 RNA expression in patient tumors with disomy 3 or monosomy 3. C. Scatter plot comparing NQO2 RNA expression in patients with tumors of an epithelioid cell type compared to other cell types (P= 0.0124). D. Scatter plot comparing NQO2 RNA expression in patients with the BAP1 wild type or BAP1 mutation. Colored fields on the Kaplan-Meier curve indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure A2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve and scatter plots for RORα expression (TCGA cohort). A. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with RORα RNA expression above or below 1 TPM (transcripts per million) (P=0.20), n=80. B. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with RORα RNA expression above or below the median value (P=0.97), n=80. C. Scatter plot comparing RORα RNA expression in patient tumors with disomy 3 or monosomy 3. D. Scatter plot comparing RORα RNA expression in patients with tumors of an epithelioid cell type compared to other cell types (spindle or mixed). E. Scatter plot comparing RORα RNA expression in patients with the BAP1 wild type or BAP1 mutation. Colored fields on the Kaplan-Meier curve indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure A2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve and scatter plots for RORα expression (TCGA cohort). A. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with RORα RNA expression above or below 1 TPM (transcripts per million) (P=0.20), n=80. B. Survival curve comparing incidence of UM-related death in those with RORα RNA expression above or below the median value (P=0.97), n=80. C. Scatter plot comparing RORα RNA expression in patient tumors with disomy 3 or monosomy 3. D. Scatter plot comparing RORα RNA expression in patients with tumors of an epithelioid cell type compared to other cell types (spindle or mixed). E. Scatter plot comparing RORα RNA expression in patients with the BAP1 wild type or BAP1 mutation. Colored fields on the Kaplan-Meier curve indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure A3.

Scatter plots for GPR50 expression (TCGA cohort). A. Scatter plot comparing GPR50 RNA expression in patient tumors with disomy 3 or monosomy 3. B. Scatter plot comparing GPR50 RNA expression in patients with tumors of an epithelioid cell type compared to other cell types. C. Scatter plot comparing GPR50 RNA expression in patients with the BAP1 wild type or BAP1 mutation.

Figure A3.

Scatter plots for GPR50 expression (TCGA cohort). A. Scatter plot comparing GPR50 RNA expression in patient tumors with disomy 3 or monosomy 3. B. Scatter plot comparing GPR50 RNA expression in patients with tumors of an epithelioid cell type compared to other cell types. C. Scatter plot comparing GPR50 RNA expression in patients with the BAP1 wild type or BAP1 mutation.

References

- Singh AD, Turell ME, Topham AK. Uveal Melanoma: Trends in Incidence, Treatment, and Survival. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(9):1881–5.

- Stålhammar G. Forty-year prognosis after plaque brachytherapy of uveal melanoma. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):11297.

- Kujala E, Mäkitie T, Kivelä T. Very Long-Term Prognosis of Patients with Malignant Uveal Melanoma. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science. 2003;44(11):4651.

- COMS. The COMS Randomized Trial of Iodine 125 Brachytherapy for Choroidal Melanoma: V. Twelve-Year Mortality Rates and Prognostic Factors: COMS Report No. 28. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2006;124(12):1684–93.

- Eskelin S, Pyrhönen S, Summanen P, Hahka-Kemppinen M, Kivelä T. Tumor doubling times in metastatic malignant melanoma of the uvea: tumor progression before and after treatment. Ophthalmology. 2000 Aug;107(8):1443–9.

- Carvajal RD, Schwartz GK, Tezel T, Marr B, Francis JH, Nathan PD. Metastatic disease from uveal melanoma: treatment options and future prospects. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(1):38–44.

- Heppt M V, Steeb T, Schlager JG, Rosumeck S, Dressler C, Ruzicka T, et al. Immune checkpoint blockade for unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017 Nov;60:44–52.

- Herrspiegel C, See TRO, Mendoza PR, Grossniklaus HE, Stålhammar G. Digital morphometry of tumor nuclei correlates to BAP-1 status, monosomy 3, gene expression class and survival in uveal melanoma. Exp Eye Res. 2020;193:107987.

- Stålhammar G, Gill VT. Digital morphometry and cluster analysis identifies four types of melanocyte during uveal melanoma progression. Commun Med. 2023;3(1):60.

- Scheuermann JC, de Ayala Alonso AG, Oktaba K, Ly-Hartig N, McGinty RK, Fraterman S, et al. Histone H2A deubiquitinase activity of the Polycomb repressive complex. Nature. 2010;465(7295):243–7.

- Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt ANJ, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434(7035):917–21.

- Jensen DE, Proctor M, Marquis ST, Gardner HP, Ha SI, Chodosh LA, et al. BAP1: a novel ubiquitin hydrolase which binds to the BRCA1 RING finger and enhances BRCA1-mediated cell growth suppression. Oncogene. 1998;16(9):1097–112.

- Szalai E, Wells JR, Ward L, Grossniklaus HE. Uveal Melanoma Nuclear BRCA1-Associated Protein-1 Immunoreactivity Is an Indicator of Metastasis. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(2):203–9.

- Koopmans AE, Verdijk RM, Brouwer RWW, van den Bosch TPP, van den Berg MMP, Vaarwater J, et al. Clinical significance of immunohistochemistry for detection of BAP1 mutations in uveal melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(10):1321–30. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.43.

- Prescher G, Bornfeld N, Hirche H, Horsthemke B, Jöckel KH, Becher R. Prognostic implications of monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma. Lancet. 1996;347(9010):1222–5.

- Gonzalez R, Sanchez A, Ferguson JA, Balmer C, Daniel C, Cohn A, et al. Melatonin therapy of advanced human malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1991;1(4):237–44.

- Claustrat B, Leston J. Melatonin: Physiological effects in humans. Neurochirurgie. 2015;61(2–3):77–84.

- Tricoire H, Møller M, Chemineau P, Malpaux B. Origin of cerebrospinal fluid melatonin and possible function in the integration of photoperiod. Reprod Suppl. 2003;61:311–21.

- Majidinia M, Sadeghpour A, Mehrzadi S, Reiter RJ, Khatami N, Yousefi B. Melatonin: A pleiotropic molecule that modulates DNA damage response and repair pathways. J Pineal Res. 2017;63(1).

- Tan D xian, Reiter R, Manchester L, Yan M ting, El-Sawi M, Sainz R, et al. Chemical and Physical Properties and Potential Mechanisms: Melatonin as a Broad Spectrum Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenger. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2(2):181–97.

- Miller SC, Pandi PSR, Esquifino AI, Cardinali DP, Maestroni GJM. The role of melatonin in immuno-enhancement: potential application in cancer. Int J Exp Pathol. 2006;87(2):81–7.

- Lissoni P, Barni S, Mandalà M, Ardizzoia A, Paolorossi F, Vaghi M, et al. Decreased toxicity and increased efficacy of cancer chemotherapy using the pineal hormone melatonin in metastatic solid tumour patients with poor clinical status. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(12):1688–92.

- Lissoni P, Meregalli S, Nosetto L, Barni S, Tancini G, Fossati V, et al. Increased Survival Time in Brain Glioblastomas by a Radioneuroendocrine Strategy with Radiotherapy plus Melatonin Compared to Radiotherapy Alone. Oncology. 1996;53(1):43–6.

- Mills E, Wu P, Seely D, Guyatt G. Melatonin in the treatment of cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. J Pineal Res. 2005;39(4):360–6.

- Hu DN, Roberts JE. Melatonin inhibits growth of cultured human uveal melanoma cells. Melanoma Res. 1997;7(1):27–31.

- Hu DN, McCormick SA, Roberts JE. Effects of melatonin, its precursors and derivatives on the growth of cultured human uveal melanoma cells. Melanoma Res. 1998;8(3):205–10.

- Robertson AG, Shih J, Yau C, Gibb EA, Oba J, Mungall KL, et al. Integrative Analysis Identifies Four Molecular and Clinical Subsets in Uveal Melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2017 Aug;32(2):204-220.e15.

- Zlotos DP. Recent progress in the development of agonists and antagonists for melatonin receptors. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(21):3532–49.

- Hagström A, Kal Omar R, Williams PA, Stålhammar G. The rationale for treating uveal melanoma with adjuvant melatonin: a review of the literature. BMC Cancer. 2022 Apr 13;22(1):398.

- Dubocovich ML, Delagrange P, Krause DN, Sugden D, Cardinali DP, Olcese J. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXV. Nomenclature, classification, and pharmacology of G protein-coupled melatonin receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62(3):343–80.

- Roberts JE, F. Wiechmann A, Hu DN. Melatonin receptors in human uveal melanocytes and melanoma cells. J Pineal Res. 2000;28(3):165–71.

- Zhao Q, Yang XL, Holtzclaw WD, Talalay P. Unexpected genetic and structural relationships of a long-forgotten flavoenzyme to NAD(P)H:quinone reductase (DT-diaphorase). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Mar;94(5):1669–74.

- Calamini B, Santarsiero BD, Boutin JA, Mesecar AD. Kinetic, thermodynamic and X-ray structural insights into the interaction of melatonin and analogues with quinone reductase 2. Biochem J. 2008;413(1):81–91.

- Reybier K, Perio P, Ferry G, Bouajila J, Delagrange P, Boutin JA, et al. Insights into the redox cycle of human quinone reductase 2. Free Radic Res. 2011;45(10):1184–95.

- Lozinskaya NA, Bezsonova EN, Dubar M, Melekhina DD, Bazanov DR, Bunev AS, et al. 3-Arylidene-2-oxindoles as Potent NRH:Quinone Oxidoreductase 2 Inhibitors. Molecules. 2023 Jan;28(3).

- Levoye A, Dam J, Ayoub MA, Guillaume JL, Couturier C, Delagrange P, et al. The orphan GPR50 receptor specifically inhibits MT1 melatonin receptor function through heterodimerization. EMBO J. 2006;25(13):3012–23.

- Giguère V, Tini M, Flock G, Ong E, Evans RM, Otulakowski G. Isoform-specific amino-terminal domains dictate DNA-binding properties of ROR alpha, a novel family of orphan hormone nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 1994;8(5):538–53.

- Jetten AM. Immunology: A helping hand against autoimmunity. Nature. 2011;472(7344):421–2.

- Halim TYF, MacLaren A, Romanish MT, Gold MJ, McNagny KM, Takei F. Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37(3):463–74.

- Wang Y, Solt LA, Kojetin DJ, Burris TP. Regulation of p53 stability and apoptosis by a ROR agonist. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34921.

- Kottorou AE, Antonacopoulou AG, Dimitrakopoulos FID, Tsamandas AC, Scopa CD, Petsas T, et al. Altered expression of NFY-C and RORA in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Acta Histochem. 2012;114(6):553–61.

- Moretti RM, Marelli MM, Motta M, Polizzi D, Monestiroli S, Pratesi G, et al. Activation of the orphan nuclear receptor RORalpha induces growth arrest in androgen-independent DU 145 prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2001;46(4):327–35.

- Du J, Xu R. RORα, a potential tumor suppressor and therapeutic target of breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(12):15755–66.

- Ma H, Kang J, Fan W, He H, Huang F. ROR: Nuclear Receptor for Melatonin or Not? Molecules. 2021;26(9).

- Becker-André M, Wiesenberg I, Schaeren-Wiemers N, André E, Missbach M, Saurat JH, et al. Pineal gland hormone melatonin binds and activates an orphan of the nuclear receptor superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(46):28531–4.

- Slominski AT, Kim TK, Takeda Y, Janjetovic Z, Brozyna AA, Skobowiat C, et al. RORα and ROR γ are expressed in human skin and serve as receptors for endogenously produced noncalcemic 20-hydroxy- and 20,23-dihydroxyvitamin D. FASEB J. 2014;28(7):2775–89.

- Slominski RM, Reiter RJ, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, Ostrom RS, Slominski AT. Melatonin membrane receptors in peripheral tissues: distribution and functions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;351(2):152–66.

- Cockrum C, Kaneshiro KR, Rechtsteiner A, Tabuchi TM, Strome S. A primer for generating and using transcriptome data and gene sets. Development. 2020 Dec 23;147(24).

- Wang XT, Chen CW, Zheng XM, Wang B, Zhang SX, Yao MH, et al. Expression and prognostic significance of melatonin receptor MT1 in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Neoplasma. 2020;67(2):415–20.

- Park HK, Ryu MH, Hwang DS, Kim GC, Jang MA, Kim UK. Effects of melatonin receptor expression on prognosis and survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;51(6):713–23.

- Lozinskaya NA, Bezsonova EN, Dubar M, Melekhina DD, Bazanov DR, Bunev AS, et al. 3-Arylidene-2-oxindoles as Potent NRH:Quinone Oxidoreductase 2 Inhibitors. Molecules. 2023 Jan 25;28(3).

- Zhang J, Zhou Y, Li N, Liu WT, Liang JZ, Sun Y, et al. Curcumol Overcomes TRAIL Resistance of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Targeting NRH:Quinone Oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2). Adv Sci (Weinh). 2020;7(22):2002306.

- Janda E, Boutin JA, De Lorenzo C, Arbitrio M. Polymorphisms and Pharmacogenomics of NQO2: The Past and the Future. Genes (Basel). 2024;15(1).

- Boutin JA. Quinone reductase 2 as a promising target of melatonin therapeutic actions. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016 Mar 3;20(3):303–17.

- Mu Q, Najafi M. Modulation of the tumor microenvironment (TME) by melatonin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021 Sep;907:174365.

- Mortezaee K, Najafi M, Farhood B, Ahmadi A, Potes Y, Shabeeb D, et al. Modulation of apoptosis by melatonin for improving cancer treatment efficiency: An updated review. Life Sci. 2019 Jul 1;228:228–41.

- Boutin JA, Liberelle M, Yous S, Ferry G, Nepveu F. Melatonin facts: Lack of evidence that melatonin is a radical scavenger in living systems. J Pineal Res. 2024 Jan;76(1):e12926.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).