1. Introduction

Video-based Human Action Recognition (HAR) is a field of computer vision that aims to identify human actions in a sequence of videos. HAR is a prominent area of research [

1] that contributes to understanding human behavior. It is challenging due to many actions, varying camera angles, similarities between actions, and changes in environmental conditions. It has applications in various industries, such as surveillance [

2], healthcare [

3], eldercare [

4], sports [

1,

5], entertainment [

6], and beyond [

7].

Videos contain both spatial and temporal features. Spatial features provide pixel information, describing the appearance, posture, and motion of individuals [

8]. In contrast, temporal features provide information about changes over time between each frame during the execution of an action. The main goal of HAR is to extract spatiotemporal patterns from video frames to identify actions. Several studies indicate that 3D CNNs effectively extract spatiotemporal features and accurately identify patterns from publicly available datasets. However, 3D CNN models exhibit increased training complexity and memory demands [

9], while transformers have gained popularity. For instance, the InternVideo-T model [

10], a high-performance model, achieves 84% accuracy on the Kinetics 700 dataset [

11] using 128 GPUs for training the model.

The example above highlights a common challenge in HAR. Although these models can produce accurate results, they require significant computational resources to be successful. In typical training scenarios, when proposing a new model or retraining an existing one with new data, it is necessary to retrain all weights for the new application. However, knowledge transfer enables the leveraging of pretrained models for new applications [

12]. By using transfer learning techniques, new models can reuse pretrained weights, eliminating the need to start from scratch. Several studies have shown that the use of pretrained models can reduce computational costs and achieve high accuracy rates for video applications [

13].

This paper presents a transfer learning HAR pipeline consisting of four stages: human detection and tracking, data preprocessing, feature extraction, and action inference. The study thoroughly analyzes transfer learning with pretrained ImageNet models, including Inception-v3, MobileNet-v3-L, MobileNet-v2, VGG-16, VGG-19, Xception, and ConvNeXt-L. The major contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

A HAR method that integrates human detection and tracking, data preprocessing, feature extraction, and action inference.

This study examines the efficacy of various pretrained models in images for feature extraction in the context HAR video-based.

An approach that uses the pretrained ConvNeXt-L model for spatial and motion feature extraction to detect five classes in an imbalanced dataset.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the related works,

Section 3 describes the proposed method,

Section 4 shows the experimental results obtained during the development of this work,

Section 5 presents a discussion of the results. Finally, in

Section 6, conclusions and future work are presented.

2. Related Work

This section provides an overview of related work on HAR, with a focus on video action recognition and convolutional, recurrent, and hybrid models. The use of 3D CNN for video action recognition is prevalent due to its ability to automatically select features through intelligent algorithms, rather than relying on handcrafted techniques where an expert would manually select features to solve the problem.

Several approaches have utilized 3D neural networks to solve video recognition tasks, with the 3D CNN [

14,

15,

16,

17] being among the most popular. However, it has been shown that the simple use of these networks is not sufficient for achieving efficient training and classifiers, as demonstrated by [

14]. To address this issue, hybrid approaches have emerged. Hybrid models allow for the combination of different classification perspectives to achieve effective classification [

18]. This can be accomplished by fusing the outputs of handcrafted and deep learning features or multiple classifiers. The output of each classifier is fused to produce a corresponding action label.

Different hybrid approaches [

18,

19,

20] have been proposed for action classification in datasets such as UCF and KTH, as well as for custom robotic applications [

21]. For instance, models such as [

18,

19] use a set of CNN or GRNN classifiers to process the input and then apply a fusion function to achieve high classification accuracy, reaching up to 99.7% in the UCF50 dataset. Additionally, the models presented in [

18,

20] demonstrate the use of traditional techniques, such as the Kalman filter, GMM, and SIFT descriptors, fused with a deep learning model to achieve 89.3% accuracy on UCF and 90% accuracy on KTH.

Models such as [

14,

15,

16] have proposed two-stream models that take advantage of multimodal learning. These approaches process spatial and temporal features separately in two streams [

22,

23]. One stream is used for spatial data processing using RGB frames, while the second stream is used for temporal data, commonly extracted from optical flow. [

14] implemented this approach using a stream with a pretrained model for knowledge transfer. The second is formed by 3D CNN layers with a dedicated block for spatial data processing between layers. This achieved 96.5% accuracy in the UCF101 dataset. Other approaches, such as [

15,

16], proposed data extraction using motion data and dedicated a stream for that, while the second processed RGB data, achieving 87.7% [

15] and 90.2% [

16] accuracy in the UCF dataset.

3. Materials and Methods

This work proposes an HAR approach based on human tracking. Studies on video-based HAR typically assume that the video input contains only one human action, using annotated videos with a single action, disregarding the possibility of other actions occurring in the same video. In some cases, researchers use videos under controlled conditions to ensure that only one action is performed in the video. However, while allowing the model to train and infer actions automatically may be more accessible, it may result in the model paying more attention to irrelevant features in the action performance, such as the background or other objects in the scene.

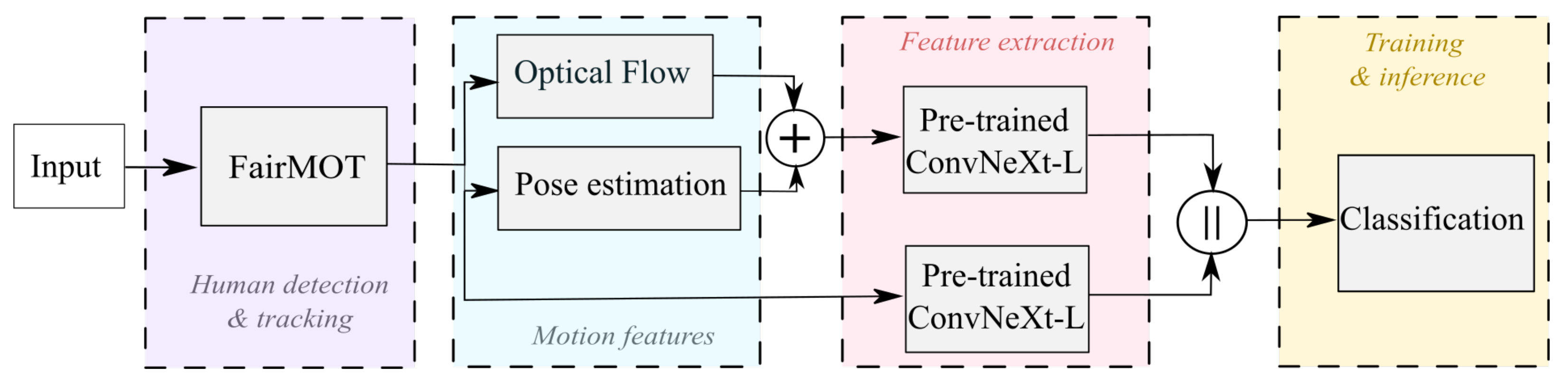

Based on the above considerations, we propose training the model by focusing solely on the subject performing the actions, using human detection and tracking as a fundamental tool to address these issues. Our proposed method consists of a two-stream architecture that takes advantage of spatial and temporal information in videos. One stream processes RGB data, while the second stream exploits temporal information using data from optical flow computation. This section outlines the proposed method, shown in

Figure 1, consisted of four stages: detection and tracking, preprocessing of the frames, feature extraction, and inference.

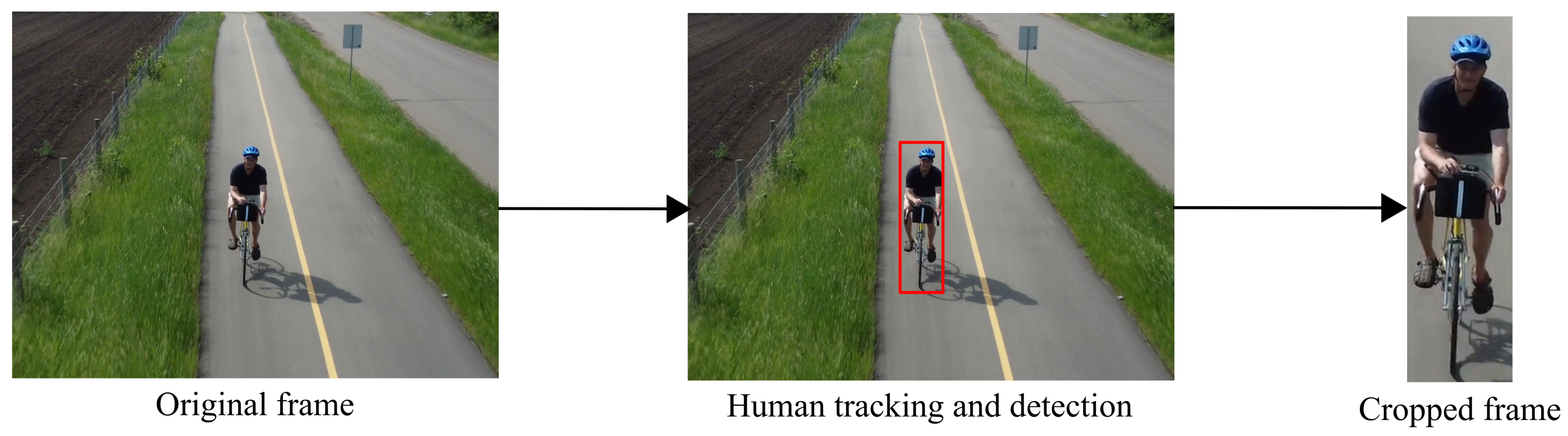

3.1. Human Detection and Tracking

This paper proposes the use of a human tracking-based approach for HAR. The main goal is to identify individuals within each video frame and track them in order to focus on the human movements, while disregarding the image background. The process for human tracking involves detecting people on video, assigning them an identifier, and then tracking their movements throughout the duration of the video. The DeepSort [

24] and FairMOT [

25] algorithms facilitate this process at an average rates of 17.5 and 24.5 frames per second, respectively. In order to achieve this, this subsection will provide a brief description of the human tracking, with a particular focus on the FairMOT model that has been employed for the development of this work.

One of the advantages of FairMOT [

25] icaracterisitcass its ability to perform human detection and re-ID in parallel, which allows for human tracking at a rate of up to 30 frames per second (FPS). The method is based on a two-stream homogeneous network. The first stream is designed to detect humans, while the second stream is used for re-ID. The detection is accomplished through the use of an object centroid estimation technique, which is based on CenterNet. The re-ID process, on the other hand, entails the generation of features that are designed to distinguish the object in question through the use of a convolutional network. Finally, the features from both streams are associated using the Mahalanobis distance and a matching algorithm.

As shown in

Figure 1, for this work we proposed the use FairMOT for tracking people in the RGB videos. Once the subjects are identified, we use the bounding box coordinates to crop the video frames and focus only on the individuals in the images. The main goal of this task is to help the model focus more on individuals rather than the background, as shown in

Figure 2. Since the area where the subject of interest appears was identified in each frame, these frames are used for HAR in subsequent stages, as described in the following subsections.

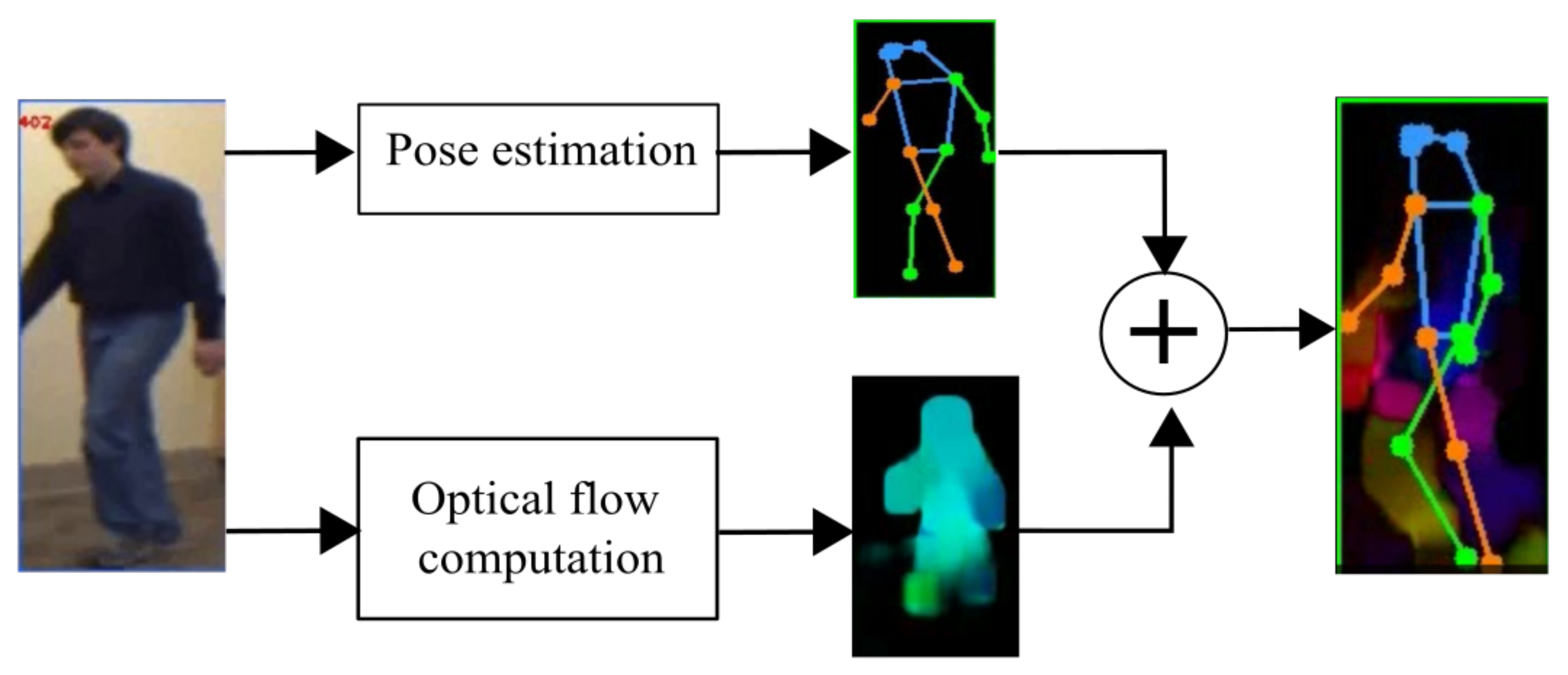

3.2. Motion Features

In the preceding section, the tracking process and the additional step of cropping each frame in the video to focus attention on a single individual and not on the entire scenario were described. The set of cropped frames will be referred to as the RGB data in the following sections. Once the cropped frames (RGB data) of the individuals have been obtained, as previously described, the next step is to preprocess them and calculate the motion features, which are composed of the optical flow and the pose features. The fusion of these features will be referred to as the motion data.

The preprocessing phase aims to improve image classification by enhancing image features, such as the human pose. While some methods avoid feature engineering and rely on deep learning for automated inference, they can be computationally expensive. Different techniques, such as image resizing, noise reduction, and contrast enhancement, can be used to process each frame. This study generated two sets of frames using RGB and motion data. The set containing the RGB data, consisted of the cropped frames obtained in the previous section, are resized to 224×224 pixels to match the input dimensions of the pretrained model used for feature extraction.

For the motion data, optical flow and pose estimation were computed from the RGB data obtained in the previous section. In order to compute the optical flow, we used the Farneback method [

26], while the mmpose framework [

27] was used to estimate the 2D pose. The resulting data was then combined to create a new image containing optical flow and 2D pose for each video frame as it is shown in

Figure 3. Finally, each frame on the set of the RGB and motion data is resized to

pixels.

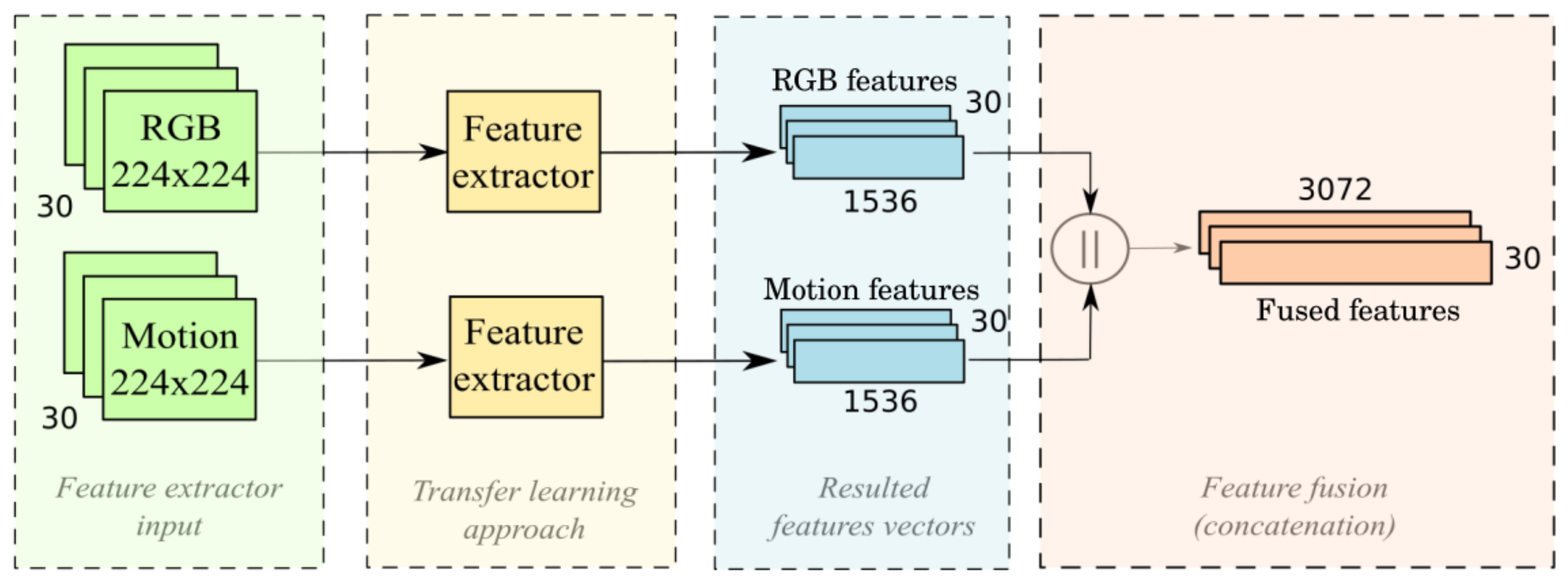

3.3. Feature Extraction

The next stage involves acquiring spatial and temporal features for the first 30 frames from the video. We use a transfer learning approach to leverage a robust model trained with images for this task. That allows us to extract spatial features from each video frame without the need to train a new model from scratch. The ConvNeXt-L model proposed in [

28] is used for this task. The feature extractor produces feature vectors of size 1536 for each frame. This output stage generates an array of 30 × 1536 features for each video, as 30 frames are used per video. This process generates two feature arrays per video: one with RGB features extracted from the RGB data and the other with extracted optical flow and pose features. Finally, we merged the features from RGB and motion data using concatenation as a fusion method. The feature arrays are concatenated per frame to create a single feature array of 30 × 3072 features. This approach utilizes the spatial features of the RGB data and the temporal features of the motion data as a single input for the classification model.

Figure 4.

Feature extraction stage.

Figure 4.

Feature extraction stage.

3.4. Training and Inference

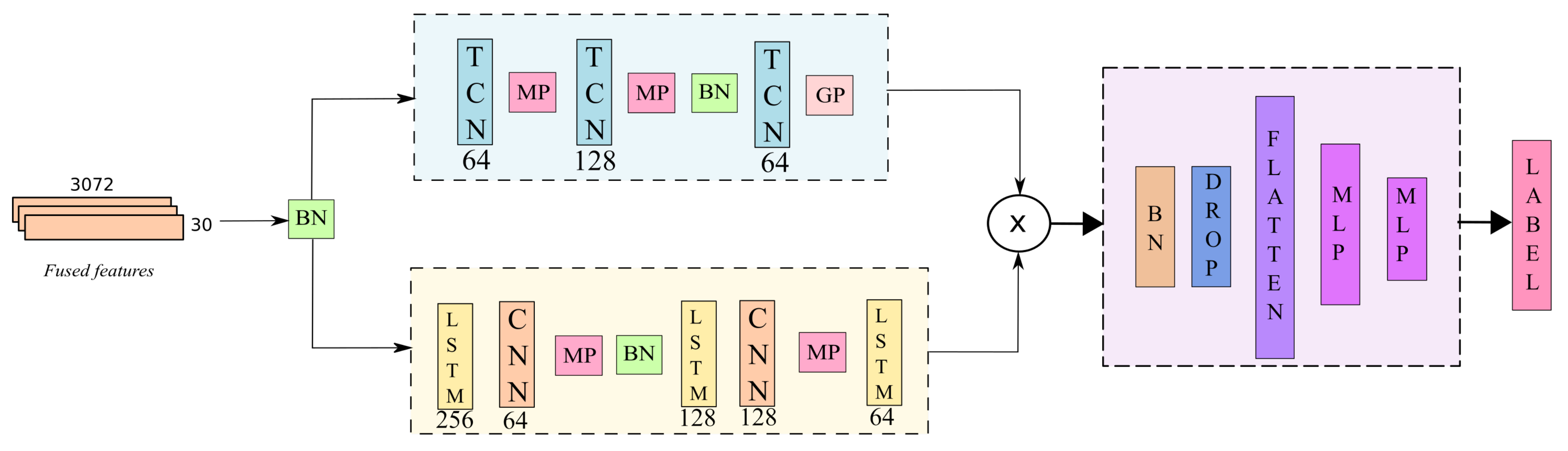

The next steps involve the training and action inference after obtaining the feature vectors. The classification model, as shown in

Figure 5, consists of three main blocks that process spatial and temporal clues for classification and inference.

After the feature fusion described in the sub

Section 3.3, batch normalization is applied to the data as a regularization step to avoid overfitting during training. The data is passed to the classification model shown in

Figure 5. The model implements a two-branch approach that processes the temporal features from the spatial data obtained with the pretrained model.

In reference to the work developed by [

29], Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) offer advantages over recurrent networks, such as a larger history compared to Long-Short Temporal Networks (LSTM). To take advantage of these features, the first stream of the proposed model includes TCN layers to exploit the temporal features between frames. The first stream of the model consists of two TCN layers with 64 and 128 filters, and dilatation factors of 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32, followed by a max pooling of 3. Then, batch normalization is applied, followed by a TCN and a max pooling layer.

The second branch comprises two LSTM layers with 256 and 128 filters, respectively, each followed by a CNN and max pooling layer with 64 and 128 filters. It concludes with an LSTM layer with 64 filters. While TCNs are effective for storing large amounts of data, they do have some drawbacks when they are used for tasks with small amounts of memory. In the second stream of the model, we utilized LSTM layers to fully leverage the temporal features of the data. The outputs are then multiplied and passed to the fully connected stack, which consists of five layers: batch normalization, dropout, linear transformation, and two MLP layers.

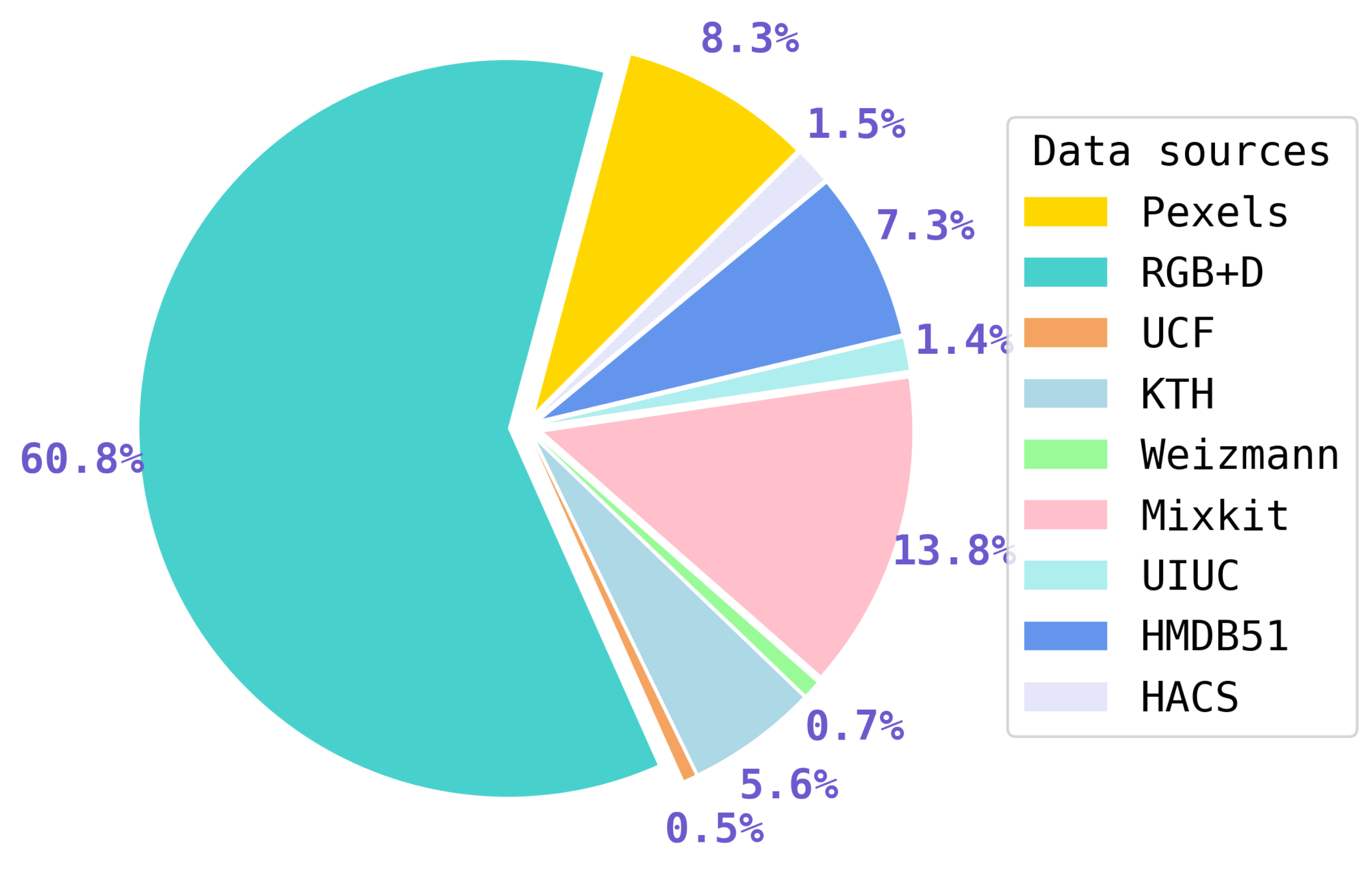

3.5. Data

It is important to note that we used a custom dataset for this work. The dataset consists of videos captured under both controlled and uncontrolled conditions, where the subjects’ bodies may be occluded in some scenarios, as shown in

Figure 6. We obtained some of these videos from Pixels [

30] and Mixkit [

31] websites, while others were selected from public datasets such as NTU RGB+D [

32], HMDB51 [

33], UCF Sports [

34], Weizmann [

35], and KTH [

36], as shown in the

Figure 7. Due to the demand for resources, this study focuses on five categories of actions: walking, running, drinking, cycling, and falling.

The dataset contains 2,813 videos divided into 189, 390, 490, 854, and 890 for cycling, running, walking, drinking, and falling class labels. The model was tested only with these videos due to limited memory resources. The data was split into three sets: 60% for training, 30% for validation, and 10% for testing.

4. Results

In this section we present the results obtained from the experimental setup including the comparison of pretrained models and the performance of the presented method using different classes. For this reason, the section is organized as follows: the first part describes the dataset used and the implementation details, and the second part shows the experimental results.

4.1. Experimental Setup

Evaluation Dataset The experiments were conducted on a custom dataset comprising five class labels. The dataset consisted of videos from public datasets, including NTU+RGBD-60, HMDB51, and KTH, which contained the actions of walking, running, cycling, drinking, or falling. Some videos were downloaded from pexels [

30] to create more variation in the dataset. The dataset has a standard three-split protocol, including training, test, and validation splits. In the end, 1,687 videos were used for training, 844 for testing, and 282 for validation.

Implementation Details For purposes of experimentation, RGB videos were employed for the extraction of RGB and motion features. Feature extraction was performed using a two-stream approach with fine-tuned pretrained models from the ImageNet dataset. In the first RGB stream, the input frames only contain the bounding box area with the detected object, while almost all the background of the image is ignored. The second stream’s input is a frame that combines optical flow with pose. The optical flow was calculated using the Gunnar Farneback method, while the MMPose framework was used for 2D pose estimation. The frames were all 224 × 224 pixels in size. We analyzed several pretrained models for feature extraction, including Inception-v3, MobileNet-v2, MobileNet-v3-L, VGG-16, VGG-19, Xception, and ConvNeXt-L. Each model generated feature vectors with varying numbers of features, ranging from 512 to 2048. The same feature extractor was used in both streams during the experiments. We trained the model using an SGD optimizer with an initial learning rate 1e-2 on a single GPU for all experiments. We implemented the model using TensorFlow and Keras frameworks.

4.2. Experimental Results

In this work, three experimental phases have been developed. In the first phase, there is a performance comparison between different pretrained models for feature extraction in the method proposed in

Section 3.4. The second experimental phase consisted of developing experiments with pretrained models using frozen weights, while the subsequent phase consisted of fine-tuning all the model parameters. For this purpose, the results obtained in each experimental stage are presented in this section.

The first experimental step was to replace the pretrained model used for feature extraction, shown in

Figure 5. For this purpose, Inception-v3, MobileNet-v2, MobileNet-v3-L, VGG16, VGG19, Xception, and ConvNeXt-L were selected. Additionally, it is worth noting that training was done using only four class labels;

Table 1 shows the training and testing results. The table shows that the ConvNeXt-L model provided the best results, followed by MobileNet-v3-L, while VGG16, the lightest model, obtained the worst result.

The ConvNeXt-L model was selected for the following experiments based on previous results. These experiments show the performance of the model using original weights during training and when full fine-tuning is performed. Only RGB data were used for preliminary experiments to feed the proposed model.

Table 2 shows the results obtained when three, four, and five class labels were used during training. Experiments demonstrated that implementing fine-tuning improves performance accuracy of the proposal, increasing it by up to 12%. Additionally, significant improvement was observed during training with five classes. Initial experiments showed accuracy barely surpassing 60%, but with fine tuning, results increased to 90.93% using only RGB data.

One of the goals of this proposal is to use motion information to enrich temporal data and take advantage of appearance and movement information. In the next experimental stage, features from the RGB and Motion data were fused. Results similar to the previous stage were presented in

Table 3, showing the training results when frozen weights were used and when fine-tuning was done. Similar to the previous results, the fine-tuning test results show an average of 91.66% and 92.35% in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively.

5. Discussion

This work presents a method for performing HAR in videos using a transfer learning approach for feature extraction. Two different transfer learning schemes were adopted. The first scheme involved using the original weights of the models to evaluate the performance of the seven models on the proposal shown in

Figure 5. The second scheme involved retraining all weights of the models to improve the resulting accuracy of the proposal.

Regarding the results presented in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 of

Section 4.2, it is encouraging to note that using the original weights of the models leads to accuracies ranging from 86% to 94%, with the ConvNeXt-L model performing the best. As a result, the next set of reported experiments used the ConvNeXt-L model. As part of preliminary experiments, we studied the behavior of the model when using only the RGB data generated in

Section 3.2. Under this scheme, the model achieved 90% accuracy when trained with four class labels, compared to the 63% accuracy obtained when five class labels were included.

To improve the performance of the proposed model, the next set of experiments involved feeding the model with the RGb and motion data. The use of motion features was expected to enhance the model’s performance. As expected, the results, shown in

Table 3, improved up to 10%. The best improvement was observed during the training of five classes, achieving a 73% accuracy while when four classes were trained, the accuracy achieved 94%, an improvement of four percentage points. These results prove that motion features enhance the model’s performance.

The weights of the pretrained models were retrained to increase the accuracy of the proposed model. Training under this scheme and using the RGB data resulted in an improved accuracy from 3.71% to 27.93%. This gave us an average accuracy of 91.8% when training with three, four, and five classes, a considerable improvement compared to the 79.7% achieved when training with the original weights. The results of using both RGB and Motion data were observed to be interesting, as the resulting accuracy average of 92.4% was similar to the case with only RGB data while presenting an improvement of 0.9% to 19.11%. The training was conducted with five class labels, which yielded the best results.

6. Conclusions an Future Work

In this work a method for HAR that utilizes CNN, LSTM, and transfer learning is presented. The workflow involves human detection and tracking, video preprocessing, feature extraction, and action inference. The conclusions derived from this work and possible future directions for work are presented next.

6.1. Conclusions

This paper presents a tracking-based method for the HAR task. The goal of the method is to identify the human movement patterns associated with the execution of these action classes. To achieve this goal, a multiple object tracker, namely FairMOT, was employed to track the humans within the video sequences. Subsequently, the bounding boxes identified by FairMOT were employed to crop the video frames around the detected humans and then, motion data were estimated through the implementation of an optical flow and pose estimation algorithms.

Afterwards, feature extraction is conducted. Using a pretrained model the method exploit the spatial information on the RGB data while temporal features were extracted using a motion data. Seven pretrained models were examinated for feature extraction, and the ConvNeXt-L model demonstrating the most promising performance, as illustrated in

Table 1; however, a lightweight model could be chosen to save time and resources, even at the cost of accuracy. The resulting features from the ConvNeXt-L model were introduced to a two-stream model. While some researchers propose the use of two-stream models with a dedicated stream for spatial and temporal information, in this work, the presented model employs a pretrained model for spatial feature extraction, which feeds a two-stream network for the processing of temporal data with LSTM and TCN layers. The outputs of the two streams are then combined into a single feature vector for the input video.

The resulting model exhibited test accuracy of 90.3%, 94.9%, and 92.11% with three, four, and five classes, respectively improving the results when only RGB data is employed. It was observed that the model exhibited higher accuracy results when trained with four classes. This indicates that the patterns identified by the model during training allow for more effective differentiation between the four classes used during training. However, further investigation is necessary to confirm these findings. In particular, future work should consider training the model with a wider range of classes.

Upon examination of the model’s performance with the imbalanced dataset, it was observed that during training, the results did not exhibit a clear bias towards any specific class. The model exhibited precision of approximately 92.35%, which was calculated by averaging its performance across three, four, and five classes, as detailed in

Table 3. Due to limited resources, specifically in terms of memory, the work was restricted to five action classes: cycling, walking, running, drinking, and falling. This resulted in a dataset with 2,813 videos encompassing a diverse range of scenarios, including both controlled (67.1%) and uncontrolled scenes (32.9%). Although the dataset encompasses a diverse range of scenarios, including both controlled and uncontrolled conditions, the experimental stage could be enhanced for future studies. This could be achieved by increasing the variety of the dataset with respect to uncontrolled scenarios. This would enable the observation of whether the performance of the model is maintained or enhanced.

6.2. Future Work

Based on the work presented in this paper, we have identified some essential points for future development. One crucial aspect for real-world applications is increasing the number of classes the model recognizes. Currently, there are datasets containing up to 700 class labels. However, a significant amount of computational resources is required for training, but with pretrained models as ConvNeXt-L could be help develop deeper models or ensembling different classifiers to achieve the task. Additionally, action recognition serves as a good starting point for automatic human behavior understanding. Therefore, developing models for complex action recognition, action tracking, and even multilabel recognition is essential. Finally, transformers have been gaining attention in computer vision. It would be useful to develop a study to compare transfer learning approaches using transformers and video pretrained models, rather than only using convolutional approaches.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, E.L.-L.; methodology, E.L.-L. and H.S.; software, E.L.-L.; validation, E.L.-L., H.S. and E.R.-E.; formal analysis, E.L.-L; investigation, E.L.-L.; resources, E.R.-E. and H.S.; data curation, E.L.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.-L.; writing—review and editing, H.S. and E.R.-E.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Instituto Politécnico Nacional and Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado (SIP-IPN) under projects 20231622, 20232570, 20242742 and 20240956 for the economical support to undertake this research and the Comisión de Operación y Fomento de Actividades Académicas (COFAA-IPN). E. López thanks CONAHCYT for the scholarship granted to undertake her PhD studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HAR |

Human Action Recognition |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| TCN |

Temporal Convolutional Network |

| SGD |

Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| MOT |

Multi-Object Tracking |

| VGG |

Visual Geometry Group |

| LSTM |

Long Short Term Memory |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

| HMDB |

Human Motion Database |

| RGB |

Red Green Blue |

| BN |

Batch Normalization |

| GP |

Global Pooling |

| MP |

Max Pooling |

| MLP |

Multi Layer Perceptron |

References

- Luo, C.; Kim, S.W.; Park, H.Y.; Lim, K.; Jung, H. Viewpoint-Agnostic Taekwondo Action Recognition Using Synthesized Two-Dimensional Skeletal Datasets. Sensors (Basel) 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen, K.; Liu, J.; Barsopia, V. A Hybrid two-stream approach for Multi-Person Action Recognition in TOP-VIEW 360° Videos. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 2021, pp. 3418–3422. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Lopes, J.M.; Moccia, S.; Berardini, D.; Migliorelli, L.; Santos, C.P. Deep learning-based approaches for human motion decoding in smart walkers for rehabilitation. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 228, 120288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Jang, C.; Park, G.; Cho, J.; Kim, I.J. ElderSim: A Synthetic Data Generation Platform for Human Action Recognition in Eldercare Applications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9279–9294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z. A Lightweight Two-stream Fusion Deep Neural Network Based on ResNet Model for Sports Motion Image Recognition. Sensing and Imaging 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patron-Perez, A.; Marszalek, M.; Zisserman, A.; Reid, I. High Five: Recognising human interactions in TV shows. 2010, pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Ou, L. Human–robot collaborative interaction with human perception and action recognition. Neurocomputing 2024, 563, 126827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Zhang, Y.X.; Zhong, B.; Lei, Q.; Yang, L.; Du, J.X.; Chen, D.S. A Comprehensive Survey of Vision-Based Human Action Recognition Methods. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareek, P.; Thakkar, A. A survey on video-based Human Action Recognition: recent updates, datasets, challenges, and applications. Artificial Intelligence Review 2021, 54, 2259–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Huang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xing, S.; Chen, G.; Pan, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Y. InternVideo: General Video Foundation Models via Generative and Discriminative Learning, 2022. arXiv:cs.CV/2212.03191].

- Smaira, L.; Carreira, J.; Noland, E.; Clancy, E.; Wu, A.; Zisserman, A. A Short Note on the Kinetics-700-2020 Human Action Dataset, 2020. arXiv:cs.CV/2010.10864].

- Tammina, S. Transfer learning using VGG-16 with deep convolutional neural network for classifying images. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, U.; Madhok, R.; Essa, I. Video Jigsaw: Unsupervised Learning of Spatiotemporal Context for Video Action Recognition. 2019 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2019, pp. 179–189. [CrossRef]

- Diba, A.; Fayyaz, M.; Sharma, V.; Arzani, M.M.; Yousefzadeh, R.; Gall, J.; Van Gool, L. Spatio-temporal Channel Correlation Networks for Action Classification. Computer Vision – ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Ye, O.; Zhou, B. An Modified Video Stream Classification Method Which Fuses Three-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network. 2019 International Conference on Machine Learning, Big Data and Business Intelligence (MLBDBI), 2019, pp. 105–108. [CrossRef]

- Diba, A.; Pazandeh, A.M.; Gool, L.V. Efficient Two-Stream Motion and Appearance 3D CNNs for Video Classification, 2016. arXiv:cs.CV/1608.08851].

- Duvvuri, K.; Kanisettypalli, H.; Jaswanth, K.; K., M. Video Classification Using CNN and Ensemble Learning. 2023 9th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS), 2023, Vol. 1, pp. 66–70. [CrossRef]

- Ijjina, E.P.; Krishna Mohan, C. Hybrid deep neural network model for human action recognition. Applied Soft Computing 2016, 46, 936–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouedi, N.; Boujnah, N.; Bouhlel, M.S. A new hybrid deep learning model for human action recognition. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2020, 32, 447–453, Emerging Software Systems. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.C.B.; Mishra, S.R.; Srujan Raju, K.; Narasimha Prasad, L.V. Human action recognition using a hybrid deep learning heuristic. Soft Computing 2021, 25, 13079–13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Gao, R.X. Hybrid machine learning for human action recognition and prediction in assembly. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2021, 72, 102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Silva, V.; de Barros Vidal, F.; Soares Romariz, A.R. Human Action Recognition Based on a Two-stream Convolutional Network Classifier. 2017 16th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), 2017, pp. 774–778. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Ma, Y.; Yang, W.; Ji, W.; Wang, R.; Jiang, P. Spatial-temporal interaction learning based two-stream network for action recognition. Information Sciences 2022, 606, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple Online and Realtime Tracking with a Deep Association Metric. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2017, pp. 3645–3649. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Liu, W. FairMOT: On the Fairness of Detection and Re-identification in Multiple Object Tracking. International Journal of Computer Vision 2021, 129, 3069–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnebäck, G. Two-Frame Motion Estimation Based on Polynomial Expansion. Image Analysis; Bigun, J., Gustavsson, T., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; pp. 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Contributors, M. OpenMMLab Pose Estimation Toolbox and Benchmark. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/open-mmlab/mmpose.

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2022.

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling, 2018. arXiv:cs.LG/1803.01271].

- Available online: https://www.pexels.com (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Mixkit - Awesome free assets for your next video project — mixkit.co. Available online: https://mixkit.co/ (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Liu, J.; Shahroudy, A.; Perez, M.; Wang, G.; Duan, L.Y.; Kot, A.C. NTU RGB+D 120: A Large-Scale Benchmark for 3D Human Activity Understanding. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020, 42, 2684–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehne, H.; Jhuang, H.; Garrote, E.; Poggio, T.; Serre, T. HMDB: A large video database for human motion recognition. 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, 2011, pp. 2556–2563. [CrossRef]

- Soomro, K.; Zamir, A.R.; Shah, M. UCF101: A Dataset of 101 Human Actions Classes From Videos in The Wild, 2012. arXiv:cs.CV/1212.0402].

- Blank, M.; Gorelick, L.; Shechtman, E.; Irani, M.; Basri, R. Actions as Space-Time Shapes. The Tenth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV’05), 2005, pp. 1395–1402.

- Schuldt, C.; Laptev, I.; Caputo, B. Recognizing human actions: a local SVM approach. Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, 2004. ICPR 2004., 2004, Vol. 3, pp. 32–36 Vol.3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).