1. Introduction

More than two-thirds of the world's private companies are family-owned, contributing to more than 70% of the global GDP and employing over 60% of the global workforce [

1,

2,

3]. In Portugal, this trend is similar, with 80% of companies being family-owned, accounting for over 50% of the national GDP and employing more than 50% of the workforce [

4]. Family businesses are the dominant form of enterprise globally and are recognized as significant drivers of economic prosperity and stability [

5]. Due to their important role in socioeconomic development, family businesses have increasingly attracted scholarly attention in recent years [

6].

Numerous previous studies have emphasized the importance for companies to strive for employee well-being, as it leads to improved organizational productivity, reduced workplace stress, decreased employee turnover, and increased stakeholder satisfaction [

7]. However, companies can only achieve wellness in the workforce if they provide a positive and healthy workplace environment free from stress, morale issues, harassment, and discriminatory practices [

8]. Family businesses, recognizing that employees are their lifeblood, invest considerable efforts into creating and maintaining a pleasant and positive work environment where employees are valued, appreciated and cherished, often treating them as "part of the family" [

9]. Despite these efforts, organizational traditions and norms, coupled with the family firms' focus on preserving socioemotional wealth, defined as "the non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty" [

10] (p. 106), can sometimes foster an "us-against-them" mentality. This mentality may lead family leaders to prioritize their needs over those of non-family stakeholders, including non-family employees [

11]. Such dynamics can have direct consequences on employees' well-being.

This study aims to address a gap in the literature related to human capital management in family businesses by examining the relationships between formal leaders and their employees. Specifically, it seeks to: (1) explore the differences in perceptions of dark traits in formal leaders and levels of workplace stress among employees in family and non-family businesses; and (2) assess whether the nature of the company (family-owned versus non-family-owned) moderates the relationship between the employees' perceptions of dark triad traits in their formal leaders and their workplace stress levels. Grounded in the principles of socioemotional wealth (i.e., the “affective endowments” of the owning family that derives from the family’s controlling position in a particular firm [

12]) and in the dark triad psychological theory of personality, this study aims to enhance understanding of variables that so far have received less attention in the comparison between family and non-family businesses.

This paper follows a structured approach. It begins by presenting and discussing the theoretical foundations of the main concepts and variables under study, along with the derivation of hypotheses. Next, the sample and methods used in the research are described. Subsequently, the empirical results are presented and thoroughly discussed, with their implications explored. Finally, the paper addresses research limitations, suggests avenues for future investigations, and discusses both theoretical and practical implications as well as the main conclusions.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Dark Triad in Formal Leaders

Effective leadership involves influencing others to achieve common goals and promoting organizational success [

13]. However, it is known that leadership emergence, effectiveness and outcomes are strongly influenced by individual differences and personality traits [

14], including those encompassed within the dark triad. The dark triad psychological theory of personality, adopted in this study, represents a set of three socially averse personality characteristics, namely subclinical narcissism, Machiavellianism and subclinical psychopathy, [

15], that have emerged as significant predictors of leadership emergence, effectiveness and style [

16].

Accordingly, narcissistic individuals exhibit grandiosity, entitlement, and a need for admiration, which can be both advantageous and detrimental to organizational functioning [

17]. While narcissism is often associated with charisma, vision, and confidence, it also entails egocentrism, arrogance and a lack of empathy [

18]. Machiavellian individuals tend to be strategic, manipulative, and adept at navigating complex social dynamics to achieve personal goals [

19]. They tend to prioritize self-interest over ethical considerations, employing deceptive tactics and exploiting others to gain power and control [

20]. Psychopathic individuals are characterized by impulsivity, callousness, and antisocial behavior, posing significant risks to organizational integrity and employee well-being [

21]. Their charm, superficial charm, and fearlessness may initially captivate followers but often lead to exploitation, betrayal and organizational harm [

22]. Below these three manipulative and exploitative traits in formal leaders are briefly discussed:

Narcissism, characterized by grandiosity, entitlement, and a lack of empathy, has received substantial attention due to its implications for individual functioning and social dynamics. Recent studies have highlighted the nature of narcissism, encompassing vulnerable and grandiose subtypes, each with distinct interpersonal behaviors and outcomes [

23]. Grandiose narcissism is often associated with assertiveness and social dominance, facilitating leadership emergence and success in competitive environments [

18]. However, narcissistic individuals often exhibit poor interpersonal relationships and engage in counterproductive work behaviors, driven by their inflated self-image and disregard for others' feelings [

24].

Machiavellianism, characterized by manipulation, cunningness, and strategic thinking, has been linked to various interpersonal and organizational outcomes. Recent research has explored its role in leadership emergence, with Machiavellian individuals often exhibiting assertive and dominant behaviors conducive to leadership positions. However, their leadership style tends to be exploitative and self-serving, undermining organizational cohesion and ethical standards [

20]. Machiavellianism also influences interpersonal relationships, with Machiavellian individuals prioritizing their own interests over others', leading to manipulation and deceitful tactics to achieve personal goals [

25].

Psychopathy, characterized by callousness, impulsivity, and antisocial behavior, remains a focal point of research due to its implications for societal well-being. Recent studies have elucidated the neurobiological underpinnings of psychopathy, highlighting deficits in affective processing and empathy-related brain regions [

26]. Psychopathic traits predict a range of adverse outcomes, including aggression, substance abuse, and recidivism, underscoring the importance of early identification and intervention [

27] . Moreover, research has explored the interaction between psychopathy and environmental factors, such as childhood adversity, in shaping antisocial behavior and treatment outcomes [

28].

In both family and non-family businesses, effective leadership is crucial for achieving organizational objectives and ensuring long-term success. As previously mentioned, the dynamics of leadership in these contexts are influenced by various factors, with individual personality traits being one of the most significant. Within family businesses, leadership often intertwines with familial relationships and dynamics. In such settings, the leadership effectiveness may be influenced not only by individual personality traits but also by family dynamics, inheritance, and expectations. Traits such as extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience (i.e., the Big Five model) remain crucial for effective leadership in both family and non-family businesses. A family business leader high in emotional stability may navigate familial conflicts and business challenges with resilience, maintaining cohesion within the family and the organization. However, the presence of dark triad traits can also manifest within family businesses, potentially impacting leadership effectiveness and organizational outcomes. Machiavellian tendencies might be observed in family business leaders who strategically maneuver through familial power dynamics to further personal agendas, potentially at the expense of family harmony or ethical considerations. Similarly, narcissistic traits could lead to a leader prioritizing personal ambition and recognition over the collective success of the family business, potentially causing rifts within the family or hindering organizational growth. Moreover, psychopathic leaders may disregard ethical norms and interpersonal boundaries, engaging in manipulative or abusive behaviors that disrupt business operations. While the presence of dark triad traits in business leaders has been widely studied and discussed in various contexts [

29], its exploration within the context of family businesses remains notably scarce in the existing literature.

Based on the notion that family firms have unique dynamics such as concentrated ownership, overlapping family and business interests, prioritization of family goals, reduced external scrutiny and cultural and structural informalities [

30,

31] which can create environments where dark triad traits are more prevalent or more easily perceived, we propose that:

H1. Family firms’ employees perceive higher levels of dark triad traits in their leaders than non-family firms’ employees.

2.2. Workplace Stress

The research of stress in the workplace represents an important endeavor within organizational research due to its far-reaching implications for both individuals and organizations [

32]. In recent years workplace stress has emerged as a predominant psychosocial challenge within most enterprises, affecting a substantial portion of the workforce. Recent data suggests that over 75% of employees acknowledge needing support in managing workplace stress [

33]. At its core, workplace stress encompasses a set of factors, including excessive workloads, time pressures, interpersonal conflicts and job insecurity, all of which can significantly impact employee well-being and organizational performance. From an individual perspective, prolonged exposure to stressful work environments can lead to a variety of adverse outcomes, ranging from psychological distress and burnout to physical health problems such as cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, workplace stress has been linked to reduced job satisfaction, diminished engagement and increased turnover intentions, therefore posing challenges not only for employees' well-being but also for organizational stability, continuity and success. Moreover, high levels of workplace stress among employees can undermine organizational culture, erode trust and impede teamwork, thus hindering the achievement of strategic objectives and competitive advantage [

34].

The World Health Organization defines workplace stress as “the response people may have when presented with work demands and pressures that are not matched to their knowledge and abilities and which challenge their ability to cope”, and further elaborates that it can be caused by poor work organization, poor work design (e.g., lack of control over work processes), poor management, unsatisfactory working conditions and lack of support from colleagues and supervisors [

35].

One of the most widely adopted theoretical frameworks for understanding workplace stress is the Job Demands-Resources model [

36], which offers a comprehensive framework used to understand the complex interplay between the various aspects of work and their impact on employee well-being and performance. This model is widely recognized and applied in management and related fields due to its ability to explain both the detrimental and beneficial aspects of work environments. At its core, the Job Demands-Resources model suggests that every job comprises two fundamental categories of characteristics: (1) job demands and (2) job resources.

- (1)

Job demands refer to the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological effort from employees. These demands can include factors such as workload, time pressure, emotional labor, role ambiguity, and interpersonal conflict. Job demands are often associated with increased workplace stress levels and the potential for burnout if they exceed an individual's coping abilities.

- (2)

Job resources are the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that help individuals achieve their work-related goals, reduce job demands, and stimulate personal growth and development (i.e., social support from colleagues and supervisors, autonomy, opportunities for skill development, feedback and a supportive organizational culture). These resources play a crucial role in buffering the negative effects of job demands, enhancing motivation and fostering a positive work environment.

The model also proposes two distinct processes through which job demands and resources influence employee outcomes: (1) health impairment process and (2) motivational process:

- (1)

Health impairment process: In this process, high job demands, if not adequately managed, can lead to negative outcomes such as stress, burnout and health problems. When individuals are exposed to excessive demands without sufficient resources to cope, they may experience emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment, ultimately leading to burnout. This process highlights the importance of managing and reducing harmful job demands to protect employee well-being.

- (2)

Motivational process: In contrast, job resources are crucial for stimulating motivation and engagement among employees. When individuals have access to supportive resources, they are more likely to experience positive emotions, higher levels of job satisfaction, and increased commitment to their work. By providing employees with the necessary resources to perform their jobs effectively and develop their skills, organizations can enhance employee motivation and

Family businesses are often characterized by a blend of family and business roles, leading to role ambiguity and conflict [

37]. Employees may face unclear job expectations and responsibilities, contributing to elevated workplace stress levels. The overlapping personal and professional relationships can blur boundaries, creating tension and pressure that are less common in non-family businesses where roles are more clearly delineated [

38]. The sense of obligation and loyalty that family and non-family members feel towards the business can also increase stress. This is often referred to as "familiness," a unique resource that can either be a strength or a source of strain [

39]. Employees in family firms might feel compelled to prioritize the firm's success over their personal well-being, leading to long working hours, high job demands and limited work-life balance [

40]. Based on these premises, we hypothesize that employees working in family companies exhibit higher levels of workplace stress when compared employees in non-family companies. Thus, our second hypothesis is as follows:

H2. Family firms’ employees show higher levels of workplace stress than non-family firms’ employees.

The intersection of the dark triad traits and workplace stress within the context of family businesses presents a complex and potentially volatile dynamic. Family businesses, which are characterized by the intertwining of family relationships and business operations, can serve as fertile ground for the manifestation and exacerbation of these traits, particularly under conditions of stress [

41]. Firstly, leaders high in narcissism within family businesses may exhibit a strong sense of entitlement, grandiosity and a continuous need for admiration. When faced with stressful situations such as succession planning, financial challenges, or conflicts within the family or business, narcissistic individuals may prioritize their own interests and ego-driven agendas over the collective well-being of the company. This can lead to power struggles, lack of collaboration and an erosion of trust among family members and non-family employees, exacerbating stress levels within the business. Similarly, Machiavellianism, characterized by manipulative behavior, strategic thinking, and a focus on self-interest, can also influence the dynamics of stress within family businesses. Machiavellian leaders may exploit family relationships and organizational resources for personal gain, particularly during times of uncertainty. Their strategic and often deceptive tactics can create a toxic atmosphere of distrust and paranoia, further fueling stress and undermining the cohesion and resilience of the family business system. Psychopathy, with its traits of callousness, impulsivity, and lack of empathy, poses additional challenges in the context of family businesses under stress. Psychopathic individuals may display a disregard for ethical norms and interpersonal boundaries, engaging in manipulative or abusive behaviors that damage familial relationships and disrupt business operations. Their propensity for risk-taking and short-term gratification can also exacerbate financial and operational risks within the business, amplifying stress levels for all involved stakeholders.

Overall, the presence of formal leaders high in the dark triad traits within family businesses can contribute to a toxic organizational culture characterized by power struggles, deceit and interpersonal conflict, particularly when combined with stressors inherent to the business environment. Recognizing and addressing the influence of these traits on family business dynamics is crucial for fostering resilience, maintaining family harmony and ensuring the long-term success and sustainability of the company [

41]. Previous studies have corroborated the notion that leadership behaviors significantly influence employees' psychological well-being [

42]. Both dark leadership and toxic leader-follower relationships are indicative of high psychological and social work demands, leading to elevated workplace stress levels. Therefore, we anticipate that:

H3. The employees’ perception of dark triad traits in their leaders are positively related with their workplace stress levels.

H4. The company nature (family versus non-family) moderates the relationship between the employees’ perception of dark triad traits in their leaders and their workplace stress levels.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

Various methodologies have been employed to define family businesses [

10,

43]. In this study, we adopted the ownership and management control criterion to formulate our operational definition [

44]. Accordingly, a company is classified as a family business if at least 75% of its shares are owned by the family, and if the family exclusively manages the company. This operational framework ensures effective family governance, control and management of the company [

45].

To assess the employees' perceptions of dark triad traits in their formal leaders and their levels of work stress, we employed a cross-sectional research design. This design is well-suited for exploring relatively understudied topics like those addressed in this study [

46]. Cross-sectional designs offer advantages over experimental or longitudinal designs, particularly when achieving a high response rate (i.e., a large sample) is challenging [

46]. Throughout questionnaire development, measures were implemented to diminish common method bias, including refining scale items to eliminate ambiguity and minimizing social desirability bias in item wording [

47].

Participants completed an online questionnaire, incorporating the Portuguese version of the Dark Triad Dirty Dozen scale [

48] and the Work Stress Scale [

49]. These instruments have undergone extensive validation and are widely used in research. Data from family businesses were collected in partnership with the Portuguese Association of Family Businesses, which shared the questionnaire access link with its associate members. For non-family company employees, the questionnaire link was distributed via email using a publicly available mailing list of Portuguese companies.

The final sample consisted of 220 Portuguese employees (

Table 1). Of the 95 employees who participated in this study, 94 were employees of family businesses, and 126 were employees of non-family businesses; 55% were female, with an average age of 37 years and working in the company for approximately 13 years. Most participants hold a bachelor’s degree (40.5%), followed by the ones who have a high school diploma (34.1%), while 24.1% hold a master’s degree and 1.3% a doctoral degree. Regarding the formal employment contracts, 65.4% had a permanent contract, 22.3% a fixed-term contract and 12.3% were on temporary-work contracts. The data were collected between November 2021 and May 2022 and all respondents were employees of privately-owned small and medium-sized companies, with no management responsibilities and under formal hierarchical supervision.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dark Triad Dirty Dozen Scale

The employees’ perceptions of dark triad traits in their formal leaders were assessed using the Dark Triad Dirty Dozen scale [

48], in its Portuguese version [

50]. The scale is a brief 12-item personality inventory test to assess the possible presence of dark triad traits: narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy. Since the original scale is a self-report measure, the instrument was adapted so that employees could respond based on their perception of their formal leaders. The 12 items (e.g., narcissism: “I tend to want others to admire me.”; Machiavellianism: “I tend to manipulate others to get my way.”; and psychopathy: “I tend to lack concern for right or wrong.”) were rated on a 5-point rating scale, ranging from 1 - “Strongly Disagree” to 5 - “Strongly Agree”. Cronbach’s alpha was computed for reliability and its value was found to be 0.79. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed, and the results indicate a good model fit (χ2/df = 1.71; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.057).

3.2.2. Workplace Stress Scale

The employees’ workplace stress levels were assessed using the Workplace Stress Scale [

49]. The scale is composed on 23 items, designed to measure employees’ overall stress levels and identify patterns or trends within the workplace. Considering its practical usefulness, a reduced, faster and more economical version, proposed by the original authors, consisting of 13 items, representing the main organizational stressors was used in this study. The 13 items (e.g., “The lack of autonomy in carrying out my work has been exhausting.”, “I get irritated at being undervalued by my superiors.”, “The few prospects for career growth have left me distressed.”) were classified on a five-point rating scale ranging from 1 - “Strongly disagree” to 5 - “Strongly agree”. Cronbach’s alpha was computed for reliability and its value was found to be 0.78. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed, and the results indicate an acceptable model fit (χ2/df = 2.41; CFI = 0.86; TLI = 0.87; RMSEA = 0.091).

3.2.3. Demographic Data

In order to collect demographic data from the respondents, a short questionnaire was included in the survey. The questionnaire was comprised of five items: gender, age, seniority, education level, and employment-contract type.

4. Results

The data were analyzed through descriptive and inferential statistics (i.e., independent sample t-test and hierarchical regression). Furthermore, the report on the results of the moderation analysis, include details of the statistical method used, the interaction term, and the significance of the moderation effect. SPSS Statistics 29 Software with PROCESS Macro was utilized for data analysis and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To test our first hypothesis, means comparison and t-student test for independent samples were used (

Table 2). Results show that there are significant differences between the employees’ perceived levels dark triad traits in formal leaders’ family (M = 3.34 SD = 0.84) and non-family businesses (M = 2.34, SD = 0.96), t (217) = 8.244, p = 0.001, d = 1.10. Thus, the first hypothesis of the study was confirmed, suggesting that family firms’ employees perceive higher levels dark triad traits in their formal leaders than non-family firms’ employees.

The results for our second hypothesis (

Table 3) reveal that there are significant differences between the employees’ levels of workplace stress between employees of family (M = 3.32 SD = 0.82) and non-family businesses (M = 2.45, SD = 0.71), t (217) = 8.244, p = 0.001, d = 1.13. Thus, the second hypothesis of the study was confirmed, suggesting that family firms’ employees show higher levels of workplace stress than non-family firms’ employees.

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to test hypotheses 3 and 4, exploring if the employees’ perception of dark triad traits in their leaders are significantly and positively related with their workplace stress levels and whether the type of company (family-owned vs. non-family-owned) moderates the relationship between employees’ perception of dark triad traits in their formal leaders and their workplace stress levels. The results of the analysis are presented in

Table 4.

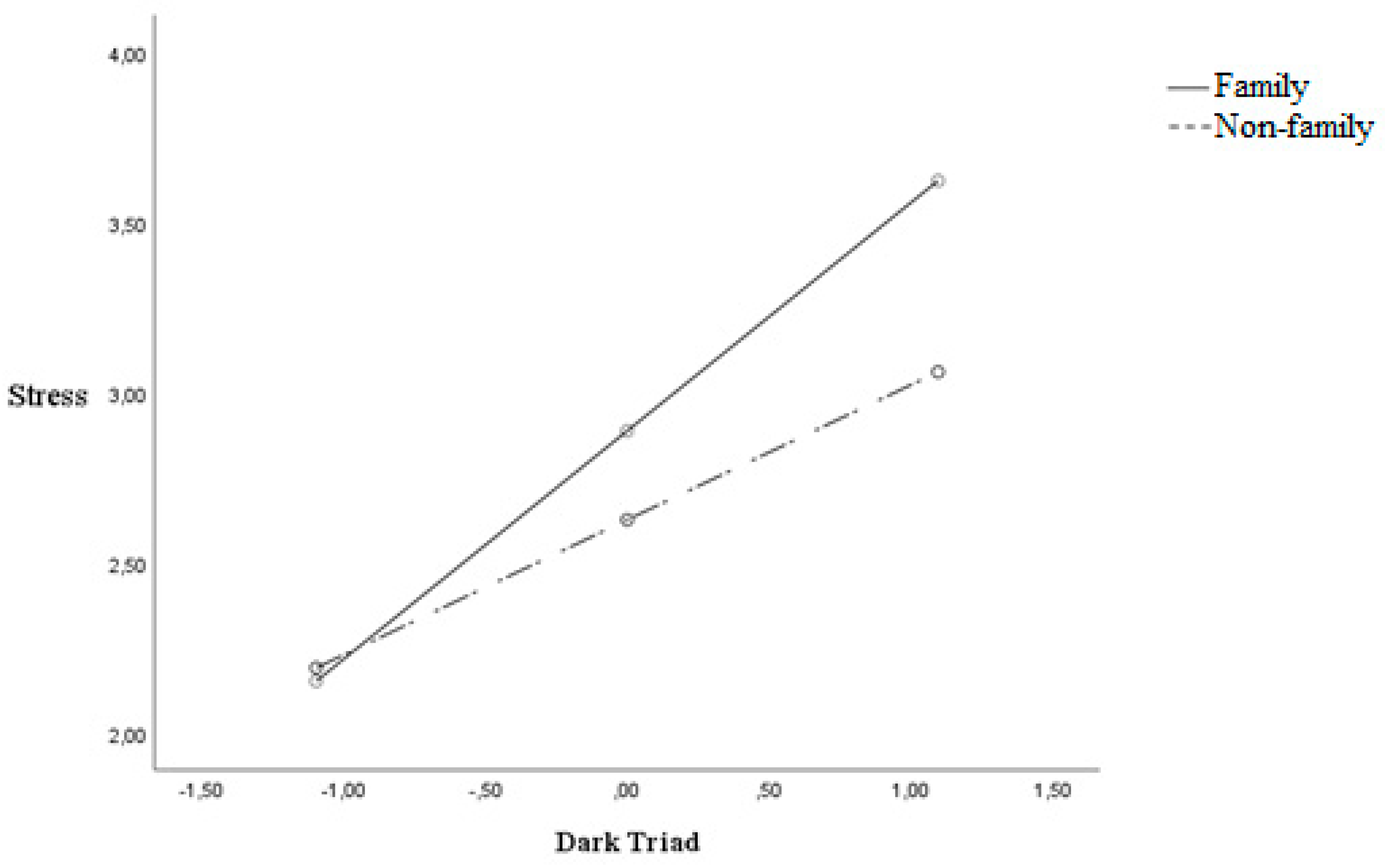

Results show that the main effect of dark triad traits in formal leaders was significant (B = 0.509, SE = 0.041, t = 12.40, p < .001). This positive relationship indicates that the employees’ higher perceptions of dark triad traits in their formal leaders are associated with higher levels of workplace stress. The main effect of company type was also significant (B = -0.262, SE = 0.093, t = -2.81, p = 0.0054), indicating that employees in non-family companies report significantly lower workplace stress levels compared to those in family companies. It is noteworthy, that the interaction term between dark triad traits and company type was significant (B = -0.275, SE = 0.084, t = -3.27, p = 0.0012). This significant interaction indicates that the type of company moderates the relationship between the emplyees’ perception of dark triad traits in their formal leaders and their workplace stress levels. Specifically, the negative coefficient for the interaction term suggests that the positive relationship between dark triad traits and workplace stress is weaker in non-family companies compared to family companies.

To further interpret the interaction effect, a simple slopes analysis was conducted (

Figure 1). The analysis revealed that the relationship between dark triad traits and workplace stress was stronger in family companies compared to non-family companies. In family companies, higher perceptions of dark triad traits in formal leaders were associated with a larger increase in the employees’ workplace stress levels, whereas in non-family companies, the increase in workplace stress levels associated with higher perceptions of dark triad traits in formal leaders was attenuated. These findings suggest that the type of company plays an important role in moderating the impact of dark triad traits in leadership on employee workplace stress levels. Specifically, non-family-owned companies seem to buffer the adverse effects of dark triad traits, resulting in a weaker relationship between these traits in formal leaders and workplace stress levels of employees.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

This study aimed to explore the differences between the perceptions of dark triad traits in formal leaders and levels of workplace stress among employees working in family and non-family businesses. Additionally, an effort was made to access if the company nature (family versus non-family) moderates the relationship between the employees’ perception of dark triad traits in their formal leaders and their workplace stress levels.

The results support the first hypothesis, suggesting that employees of family firms perceive higher levels of dark triad traits in their leaders than non-family firms’ employees. This observation can be understood through several theoretical and empirical perspectives. Family companies often have unique dynamics characterized by concentrated ownership, overlapping family and business interests and a tendency to prioritize family goals over business efficiency [

51]. These dynamics can foster environments where dark triad traits in formal leaders such as owners or managers are more prevalent or more easily perceived. For example, the nepotistic nature of family businesses may result in leaders who exhibit narcissistic behaviors, as family members may feel entitled to leadership positions regardless of merit [

52]. Thus, in family firms, where leaders may be appointed based on lineage rather than competency, these traits can become particularly pronounced and perceived. The leadership style in such companies may thus appear more autocratic and self-serving, aligning with characteristics of narcissism. Moreover, leaders in family firms might display higher levels of Machiavellianism as they navigate complex family dynamics and seek to maintain control over both business and familial spheres. The need to balance these interests could foster a manipulative leadership style perceived negatively by employees [

53]. Also, psychopathy, characterized by impulsivity, lack of empathy and antisocial behavior, is less commonly associated with leadership but can still manifest in subtle ways. In the context of family firms, the nature of the organization might allow psychopathic traits to go unchecked. Family members in leadership positions might be shielded from the typical checks and balances present in non-family firms, leading to higher perceptions of psychopathic behaviors. These findings are supported by recent research which suggests that the structure and culture of family firms create environments where the dark triad traits are more likely to emerge or be noticed [

54]. A study found that the entanglement of family and business can result in leadership styles that are perceived as more authoritarian and controlling, traits commonly associated with the dark triad [

54]. Furthermore, family firms often face less external scrutiny compared to their non-family counterparts. This reduced oversight can allow leaders with dark triad traits to operate with fewer constraints, exacerbating the perception among employees [

31]. Thus, the unique characteristics of family firms such as nepotism, overlapping family and business roles and reduced external scrutiny can create environments where dark triad traits in leaders are more prevalent or more perceptible to employees.

The results also confirm our second hypothesis, indicating that employees in family firms experience higher levels of workplace stress compared to their counterparts in non-family firms. This finding can also be attributed to several unique characteristics and dynamics inherent in family businesses. Research has shown that the high levels of emotional involvement and personal investment in family firms contribute to an intense work atmosphere. Employees often feel a heightened sense of loyalty and commitment, which can lead to longer working hours and difficulty in achieving a work-life balance [

55]. This imbalance is a key factor in increased workplace stress. Furthermore, the presence of nepotism and favoritism in family firms can create perceptions of unfairness and inequality among employees [

56]. Non-family employees, in particular, may feel marginalized or undervalued, leading to job insecurity and stress. The lack of clear meritocratic principles can exacerbate tensions and negatively impact morale. Another contributing factor is the leadership style prevalent in family firms. As discussed in the context of the first hypothesis, family firm leaders may exhibit traits associated with the dark triad. Such leadership styles can foster a toxic work environment, characterized by manipulation, lack of empathy and authoritarian control, further contributing to employee workplace stress [

52]. Additionally, family firms often prioritize long-term stability and preservation of family control over short-term performance, which can lead to conservative business practices and resistance to change [

31]. This risk-averse approach can stifle innovation and professional growth opportunities for employees, leading to frustration and stress. The insular nature of family firms also plays a role in elevated stress levels. Due to the close-knit relationships, employees may find it challenging to express grievances or seek support within the organization. The fear of damaging personal relationships or facing retribution can prevent open communication and conflict resolution, resulting in unresolved tensions [

57]. Recent studies support these observations, reporting that employees in family firms reported higher stress levels due to the dual pressures of family and business demands [

58] and highlighting that the emotional dynamics and role ambiguity in family firms also contribute significantly to workplace stress [

57]. Thus, the higher levels of workplace stress experienced by employees in family firms can be attributed to the blurred boundaries between personal and professional roles, the presence of nepotism and favoritism, toxic leadership styles, conservative business practices, and the nature of these organizations. These factors create a challenging work environment where stress is more likely to manifest and persist.

As to hypothesis 3, suggesting that the employees’ perception of dark triad traits in their leaders are positively related with their workplace stress levels, and hypothesis 4, proposing that the company nature (family versus non-family business) moderates the relationship between the employees’ perception of dark triad traits in their leaders and their workplace stress levels, the results support both hypotheses. This indicates that the company nature significantly moderates the relationship between employees’ perception of dark triad traits in their formal leaders and their workplace stress levels. Specifically, while higher levels of perceived dark triad traits in leaders are associated with increased workplace stress across both types of companies, this relationship is significantly attenuated in non-family companies. These findings contribute to the growing body of literature on the impact of leadership traits on employee well-being and highlight the importance of organizational context in moderating these effects. Previous research has consistently shown that dark triad traits, comprising narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy, are linked to various negative outcomes in the workplace, including higher levels of workplace stress and lower job satisfaction [

59,

60]. Our results extend the literature by demonstrating that the organizational context, specifically whether a company is family-owned or not, plays an important role in influencing the severity of these outcomes. Our finding that non-family companies mitigate the impact of dark triad traits in formal leaders on the employees’ workplace stress levels may be understood through several perspectives. First, non-family companies often have more formalized structures and standardized practices compared to family-owned businesses [

61]. These formal structures may help providing a buffer against the negative behaviors exhibited by leaders with dark triad traits, as employees in these organizations might rely more on established policies and procedures than on individual leaders for guidance and support [

62]. In contrast, family-owned companies tend to have more informal and relationship-based cultures, which might amplify the impact of leaders’ personalities on employees’ experiences [

52]. The strong personal relationships in family businesses can lead to a greater influence of leaders’ dark triad traits on employees, resulting in higher levels of workplace stress [

13]. This is particularly concerning given that family-owned businesses often place a high value on loyalty and long-term relationships, potentially making it more difficult for employees to escape toxic leadership [

57].

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

The study, like any empirical work, presents several limitations that point to opportunities for future research. Firstly, the study exclusively involved employees from privately-owned small and medium-sized companies in Portugal, which may introduce cultural bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. While tentative extrapolations to other Southern European contexts can be made, it is essential to replicate the study in different geographic and socioeconomic settings for comprehensive insights. Secondly, none of the participants held management responsibilities within their respective companies, which limits the overall understanding of organizational dynamics. Future studies should incorporate participants with formal management roles to provide a more holistic view of the topic.

Another aspect worth considering as a limitation is the examination of the dark triad as a unidimensional concept, drawing from literature that amalgamates the triad's concepts and treats them as a single variable. Given that combining the three constituent variables of the triad remains a topic of contention in the scientific community, with some researchers emphasizing empirical distinctions among them while others seek to integrate them, highlighting their conceptual similarities [

50]. Methodologically, the unidimensional model of the dark triad was chosen for this study since the research objective aimed to comprehend leaders' dark traid personality traits as a whole. The focus was on assessing whether, overall, employees perceive their leaders to possess a heightened dark side, detecting dark traid personality traits rather than examining these traits separately. Therefore, from a perspective of greater granularity, it is suggested that future research replicate this investigation while considering each facet of the dark triad separately, rather than treating them as a singular entity.

Furthermore, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to make causal inferences. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to better understand the causal relationships and dynamics over time. Additionally, it would be beneficial to explore other contextual factors that might moderate the relationship between dark triad traits and workplace stress, such as organizational culture, industry type, and geographic location. Finally, future research could investigate the mechanisms through which non-family companies buffer the negative effects of dark triad traits. Understanding these mechanisms could provide deeper insights into effective interventions and support systems that can be implemented across different organizational contexts.

5.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The current study delves into the intricate dynamics between dark traid leadership traits and the workplace stress levels experienced by employees, offering both theoretical insights and practical implications. By examining these factors within the context of family and non-family-owned businesses, it sheds light on nuanced differences that impact workplace dynamics. Our findings reveal a compelling correlation: in family-owned companies, both the prevalence of dark traid leadership traits and the resultant employee workplace stress levels tend to be higher. Moreover, the nature of the company itself acts as a moderator in this relationship, with family-owned businesses employees displaying a heightened sensitivity to the presence of these traits in their formal leaders. Beyond its theoretical contributions, this study holds significant practical relevance for businesses and their workforce. It underscores the critical importance of understanding and addressing the impact of dark traid leadership traits on employee well-being, particularly in family-owned settings where these effects are amplified.

From a practical standpoint, our research underscores the necessity for strategic interventions in both family and non-family companies. For family-owned businesses, proactive measures such as restructuring leadership frameworks and implementing formalized HR practices are imperative. This may involve reevaluating nepotistic practices and investing in leadership development programs aimed at cultivating positive leadership qualities. In non-family companies, maintaining formal structures and support systems is crucial to mitigate the adverse effects of dark triad traits in leadership. Initiatives like leadership training programs focusing on ethical behavior and emotional intelligence can foster healthier workplace environments and alleviate employee stress. Ultimately, this study advocates for a proactive approach to leadership selection and development, emphasizing the importance of integrating personality assessments into recruitment processes. By prioritizing employee well-being and fostering constructive leadership practices, organizations can pave the way for sustainable success and foster a positive work culture.

6. Conclusions

This study explored differences in employees' perceptions of dark triad traits in leaders and workplace stress levels between family and non-family businesses, as well as the moderating role of company nature. The findings indicate that employees in family firms perceive higher levels of dark triad traits in their leaders and experience greater workplace stress compared to those in non-family firms. This heightened perception and stress are linked to unique characteristics of family businesses, such as nepotism, overlapping roles and reduced external scrutiny. Additionally, the relationship between perceived dark triad traits in leaders and workplace stress is moderated by the type of company. While this relationship is significant in both types of businesses, it is stronger in family firms due to their informal and relationship-based cultures. Non-family firms, with their more formal structures and standardized practices, help buffer employees from the negative impacts of leaders with dark triad traits. These findings contribute to the growing body of literature on the impact of leadership traits on employee well-being and underscore the importance of organizational context in moderating these effects. Understanding the dynamics of dark triad traits in leadership within different types of companies can inform strategies to mitigate workplace stress and improve employee well-being, particularly in family-owned businesses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P., S.L. and P.M-Q.; methodology, D.P., S.L. and P.M-Q.; formal analysis, S.L and P.M-Q.; investigation, D.P., S.L. and P.M-Q; resources, D.P.; data curation, S.L.; writing - original draft preparation, D.P.; writing—review and editing, D.P.; supervision, D.P. and P.M-Q.; project administration, D.P. and P. M-Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to Portuguese law and guidelines from the Foundation for Science and Technology.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gómez-Mejía, L.; Patel, P. C.; Zellweger, T. M. In the Horns of the Dilemma: Socioemotional Wealth, Financial Wealth, and Acquisitions in Family Firms. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1369-1397. [CrossRef]

- Neckebrouck, J.; Schulze, W.; Zellweger, T. Are Family Firms Good Employers? Acad. Manage. J. 2018, 61, 553-585. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Almeida, P.; Marques-Quinteiro, P.; Sousa, M. Employer Branding and Psychological Contract in Family and Non-Family Firms. Manag. Res. 2021, 19, 213-230. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Relatório Relativo a Portugal de 2019 que Inclui a Apreciação Aprofundada da Prevenção e Correção dos Desequilíbrios Macroeconómicos. Comissão Europeia, 2019. (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Englisch, P.; Hall, C.; Astrachan, J. Staying Power: How Do Family Business Create Lasting Success? Global Survey of the World's Largest Family Business. Available online: https://www.ey.com/gl/en/services/strategic-growth-markets/family-business/ey-how-do-family-businesses-create-lasting-success (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Sageder, M.; Mitter, C.; Feldbauer-Durstmüller, B. Image and Reputation of Family Firms: A Systematic Literature Review of the State of Research. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 335-377. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D. Non-Family Employees: Levels of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Justice in Small and Medium-Sized Family and Non-Family Firms. Eur. J. Fam. Bus. 2018, 8, 93-102. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, I.; Siddique, I.; Ahmed, A. An Extension of the Socioemotional Wealth Perspective: Insights from an Asian Sample. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2019, 10, 293-312. [CrossRef]

- Suárez, C. Internal Control Systems Leading to Family Business Performance in Mexico: A Framework Analysis. J. Int. Bus. Res. 2017, 16, 1-16.

- Gómez-Mejía, L. R.; Haynes, K. T.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K. J. L.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional Wealth and Business Risks in Family-Controlled Firms: Evidence from Spanish Olive Oil Mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106-137. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Rodrigues, R. Employee Silence and Entrepreneurial Orientation in Small and Medium-Sized Family Firms. *Eur. J. Fam. Bus.* **2022**, *12* (1), 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L. R. Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Approaches, and Agenda for Future Research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258-279. [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. A.; Becker, W. S. Effective Empowerment in Organizations. Organ. Manag. J. 2006, 3 (3), 210-231. [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A.; Ilies, R.; Zhang, Z. Genetic Influences on Core Self-Evaluations, Job Satisfaction, and Work Stress: A Behavioral Genetics Mediated Model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2012, 117 (1), 208-220. [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D. L.; Williams, K. M. The Dark Triad of Personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy. J. Res. Pers. 2002, 36 (6), 556-563. [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K.; Duineveld, J. J.; Middleton, J. P. Pathology, Pseudopathology, and the Dark Triad of Personality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 78, 43-47. [CrossRef]

- Brunell, A. B.; Gentry, W. A.; Campbell, W. K.; Hoffman, B. J.; Kuhnert, K. W.; DeMarree, K. G. Leader Emergence: The Case of the Narcissistic Leader. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34 (12), 1663-1676. [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Aydin, N.; Frey, D.; Peus, C. Leader Narcissism Predicts Malicious Envy and Supervisor-Targeted Counterproductive Work Behavior: Evidence from Field and Experimental Research. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 725-741. [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Richards, S. C.; Paulhus, D. L. The Dark Triad of Personality: A 10 Year Review. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2013, 7 (3), 199-216. [CrossRef]

- Kish-Gephart, J. J.; Harrison, D. A.; Treviño, L. K. Bad Apples, Bad Cases, and Bad Barrels: Meta-Analytic Evidence About Sources of Unethical Decisions at Work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95 (1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Babiak, P.; Neumann, C. S.; Hare, R. D. Corporate Psychopathy: Talking the Walk. Behav. Sci. Law 2010, 28 (2), 174-193. [CrossRef]

- Boddy, C. R. Corporate Psychopaths, Conflict, Employee Affective Well-Being and Counterproductive Work Behaviour. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145 (1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. A.; Eugene, G.; Pribram, K. H. Plans and the Structure of Behaviour. In Systems Research for Behavioral Science; Routledge, 2017; pp 369-382.

- O’Boyle, E. H.; Forsyth, D.; Banks, G. C.; Story, P. A. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Dark Triad–Intelligence Connection. J. Res. Pers. 2013, 47 (6), 789-794. [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K.; Webster, G. D. A Protean Approach to Social Influence: Dark Triad Personalities and Social Influence Tactics. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52 (4), 521-526. [CrossRef]

- Blair, R. J. R. The Neurobiology of Psychopathic Traits in Youths. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14 (11), 786-799. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, C. J.; Venables, N. C.; Yancey, J. R.; Hicks, B. M.; Nelson, L. D.; Kramer, M. D. A Construct-Network Approach to Bridging Diagnostic and Physiological Domains: Application to Assessment of Externalizing Psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 122 (3), 902-917. [CrossRef]

- Fanti, K. A.; Kimonis, E. Heterogeneity in Externalizing Problems at Age 3: Association with Age 15 Biological and Environmental Outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53 (7), 1230. [CrossRef]

- Fodor, O. C.; Curşeu, P. L.; Meslec, N. In Leaders We Trust, or Should We? Supervisors’ Dark Triad Personality Traits and Ratings of Team Performance and Innovation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 650172. [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Chua, J. H.; Chrisman, J. J. Factors Preventing Intra-Family Succession. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21 (2), 183-199. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L. R.; Cruz, C.; Berrone, P.; De Castro, J. The Bind that Ties: Socioemotional Wealth Preservation in Family Firms. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5 (1), 653-707. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. L.; Quick, J. C., Eds. The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2017.

- McKinsey & Company. The State of Organizations 2023. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/people%20and%20organizational%20performance/our%20insights/the%20state%20of%20organizations%202023/the-state-of-organizations-2023.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Pimentel, D.; Pereira, A. Emotion Regulation and Job Satisfaction Levels of Employees Working in Family and Non-Family Firms. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 114. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Occupational Health. Stress at the Workplace. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en. (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22 (3), 309-328. [CrossRef]

- Gibb Dyer, W., Jr. Examining the “Family Effect” on Firm Performance. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19 (4), 253-273. [CrossRef]

- Eddleston, K. A.; Kellermanns, F. W. Destructive and Productive Family Relationships: A Stewardship Theory Perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22 (4), 545-565. [CrossRef]

- Habbershon, T. G.; Williams, M.; MacMillan, I. C. A Unified Systems Perspective of Family Firm Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18 (4), 451-465. [CrossRef]

- Klein, S. B.; Astrachan, J. H.; Smyrnios, K. X. The F–PEC Scale of Family Influence: Construction, Validation, and Further Implication for Theory. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29 (3), 321-339. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Pedra, A. Primary Psychopathy in Formal Leaders and Job Satisfaction Levels of Employees Working in Family and Non-Family Firms. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13 (8), 190. [CrossRef]

- Harms, P. D.; Credé, M.; Tynan, M.; Leon, M.; Jeung, W. Leadership and Stress: A Meta-Analytic Review. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28 (1), 178-194. [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, M.; Kuratko, D. F.; Holt, D. T. Examining the Link Between “Familiness” and Performance: Can the F–PEC Untangle the Family Business Theory Jungle? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 1089-1109. [CrossRef]

- Chua, J. H.; Chrisman, J. J.; Sharma, P. Defining the Family Business by Behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 23, 19-39. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Pires, J.; Almeida, P. Perceptions of Organizational Justice and Commitment of Non-Family Employees in Family and Non-Family Firms. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2020, 23, 141-154. [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. Do Not Cross Me: Optimizing the Use of Cross-Sectional Designs. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 125-137. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M.; MacKenzie, S. B.; Podsakoff, N. P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539-569. [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K.; Webster, G. D. The Dirty Dozen: A Concise Measure of the Dark Triad. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22 (2), 420. [CrossRef]

- Paschoal, T.; Tamayo, Á. Validação da Escala de Estresse no Trabalho. Estud. Psicol. (Natal) 2004, 9, 45-52. [CrossRef]

- Pechorro, P.; Caramelo, V.; Oliveira, J. P.; Nunes, C.; Curtis, S. R.; Jones, D. N. The Short Dark Triad (SD3): Adaptation and Psychometrics Among At-Risk Male and Female Youths. Deviant Behav. 2019, 40 (3), 273-286. [CrossRef]

- Schulze, W. S.; Lubatkin, M. H.; Dino, R. N.; Buchholtz, A. K. Agency Relationships in Family Firms: Theory and Evidence. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12 (2), 99-116. [CrossRef]

- De Vries, M. F. K. The Dynamics of Family Controlled Firms: The Good and the Bad News. Organ. Dyn. 1993, 21 (3), 59-71. [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. A.; Hayton, J. C.; Salvato, C. Entrepreneurship in Family vs. Non-Family Firms: A Resource-Based Analysis of the Effect of Organizational Culture. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2004, 28 (4), 363-381. [CrossRef]

- König, A.; Kammerlander, N.; Enders, A. The Family Innovator's Dilemma: How Family Influence Affects the Adoption of Discontinuous Technologies by Incumbent Firms. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2013, 38 (3), 418-441. [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T. A.; Drexler, J. A.; Faulkner, S. Working in Small Family Businesses: Empirical Comparisons to Non-Family Businesses. J. Organ. Behav. 1997, 18 (3), 297-312. [CrossRef]

- Pazzaglia, F.; Mengoli, S.; Sapienza, E. Earnings in Acquired and Nonacquired Family Firms: A Socioemotional Wealth Perspective. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2013, 26 (4), 374-386. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, T.; Kellermanns, F. W. Are We Family and Are We Treated as Family? Nonfamily Employees’ Perceptions of Justice in the Family Firm. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30 (6), 837-854. [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.; Lindsay, N. J. Incorporating the Family Dynamic into the Entrepreneurship Process. J. Small Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2002, 9 (4), 416-430. [CrossRef]

- O'Boyle, E. H.; Forsyth, D. R.; Banks, G. C.; McDaniel, M. A. A Meta-Analysis of the Dark Triad and Work Behavior: A Social Exchange Perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97 (3), 557-579. [CrossRef]

- Spain, S. M.; Harms, P. D.; LeBreton, J. M. The Dark Side of Personality at Work. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35 (S1), S41-S60. [CrossRef]

- Carney, M. Corporate Governance and Competitive Advantage in Family-Controlled Firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29 (3), 249-265. [CrossRef]

- Huybrechts, J.; Voordeckers, W.; Lybaert, N. Entrepreneurial Risk Taking of Private Family Firms: The Influence of a Nonfamily CEO and the Moderating Effect of CEO Tenure. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2013, 26 (2), 161-179. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).