Submitted:

13 May 2024

Posted:

13 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

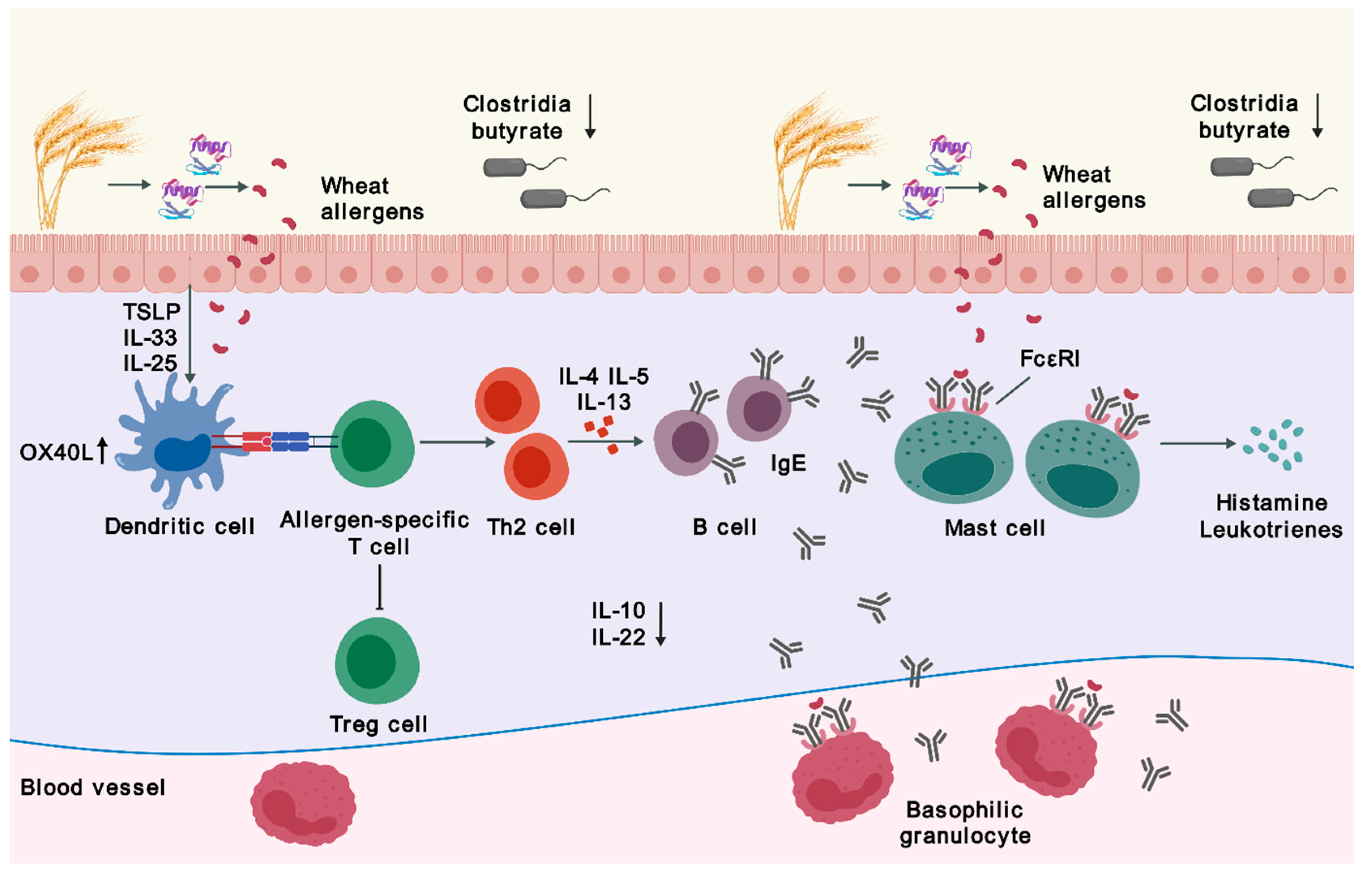

2. Immune Mechanism and Interaction with Microbiota

2.1. Sensitization

2.2. Desensitization by Immunotherapy

2.3. Microbiota

3. Clinical Features and Related Disorders

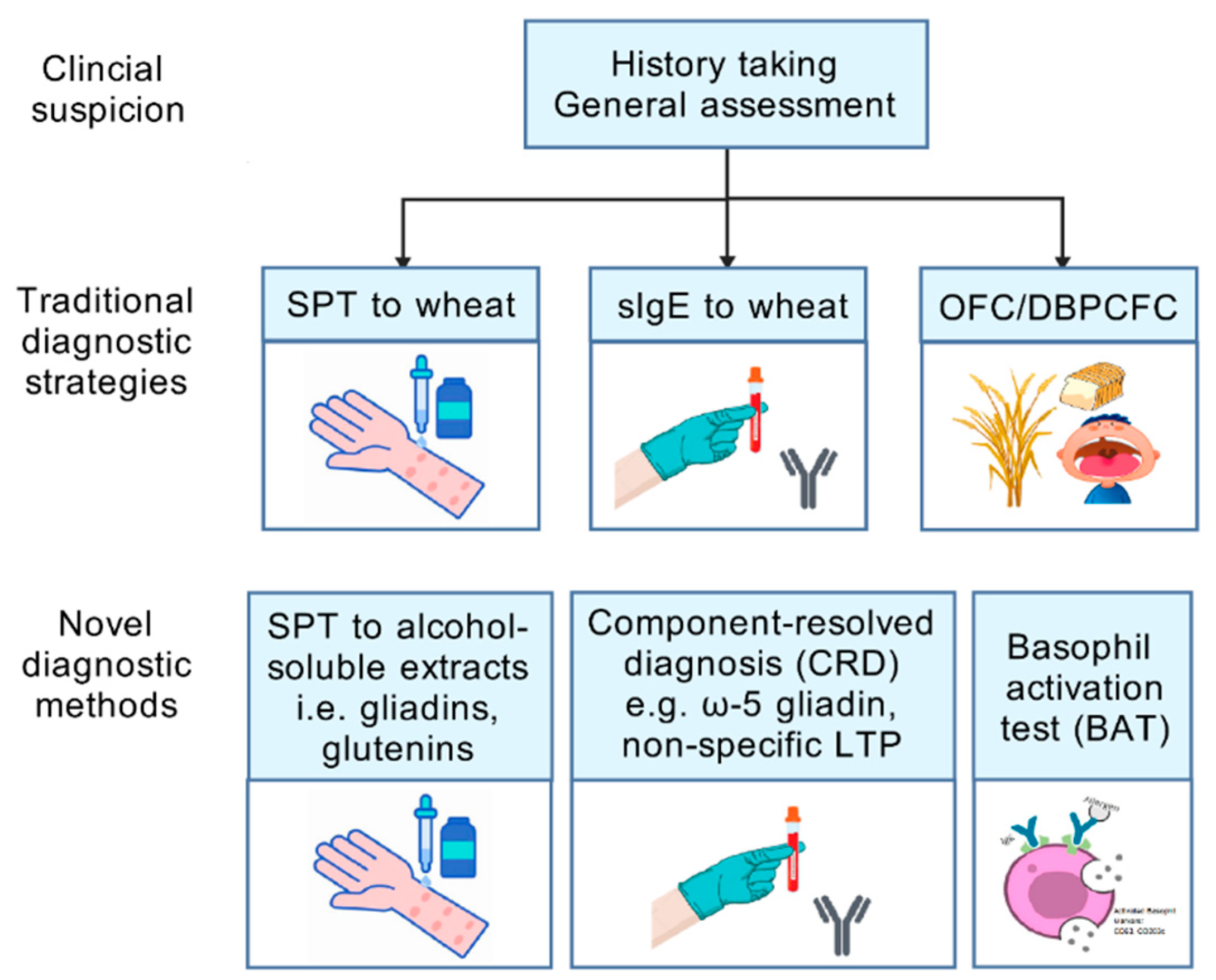

4. Diagnosis

4.1. Conventional Diagnostic Strategies

4.2. Wheat Allergens and Component-Resolved Diagnosis

4.3. Cell-Based Diagnosis

5. Management

5.1. Natural History of Wheat Allergy

5.2. Therapeutic Strategies

5.3. Immunotherapy

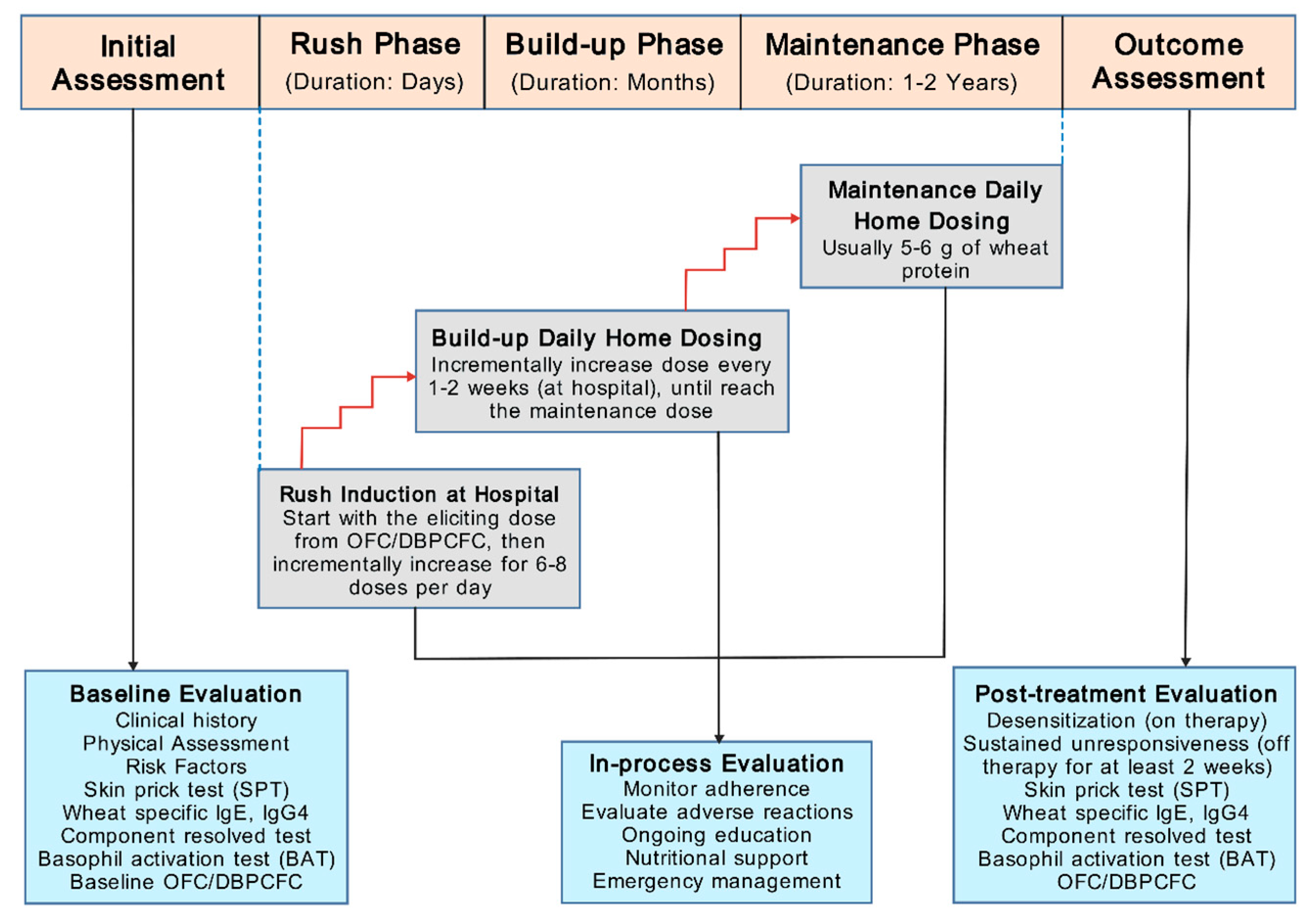

5.3.1. OIT Protocol

5.3.2. Clinical Trials

5.3.3. Precautions for OIT

5.4. Other Therapeutic Approaches

6. Conclusions and Future Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Longo G, Berti I, Burks AW, et al. IgE-mediated food allergy in children. Lancet. 2013, 382, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu W, Freeland DMH, Nadeau KC. Food allergy: immune mechanisms, diagnosis and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016, 16, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolidoro GC, Ali MM, Amera YT, et al. Prevalence estimates of eight big food allergies in Europe: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2023, 78, 2361–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Huang J, Ma S, et al. Allergenicity of wheat protein in diet: mechanisms, modifications and challenges. Food Res Int. 2023, 169, 112913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, B. Gluten-related disorders: Celiac disease, wheat allergy, and nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020, 60, 2606–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berin MC, Sampson HA. Mucosal immunology of food allergy. Curr Biol. 2013, 23, R389–R400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordesillas L, Berin MC, Sampson HA. Immunology of food allergy. Immunity. 2017, 47, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchongkittiphon W, Nopnipa S, Mathuranyanon R, et al. Characterization of gut microbiome profile in children with confirmed wheat allergy. Characterization of gut microbiome profile in children with confirmed wheat allergy. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cianferoni, A. Wheat allergy: diagnosis and management. J Asthma Allergy. 2016, 9, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacharn P, Vichyanond P. Immunotherapy for IgE-mediated wheat allergy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017, 13, 2462–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul WE, Zhu J. How are T(H)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010, 10, 225–235.

- Lamiable O, Mayer JU, Munoz-Erazo L, et al. Dendritic cells in Th2 immune responses and allergic sensitization. Immunol Cell Biol. 2020, 98, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito T, Wang YH, Duramad O, et al. TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J Exp Med. 2005, 202, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt EB, Munitz A, Orekov T, et al. Targeting IL-4/IL-13 signaling to alleviate oral allergen-induced diarrhea. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009, 123, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A. Mucosal dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol.

- de Jong NW, Wichers HJ. Update on nutrition and food allergy. Nutrients. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Eiwegger T, Hung L, San Diego KE, et al. Recent developments and highlights in food allergy. Allergy. 2019, 74, 2355–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone KD, Prussin C, Metcalfe DD. IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010, 125 (Suppl 2), S73–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli SJ, Tsai M. IgE and mast cells in allergic disease. Nat Med. 2012, 18, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyoshi MK, Oettgen HC, Chatila TA, et al. Food allergy: insights into etiology, prevention, and treatment provided by murine models. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014, 133, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekabi M, Arshi S, Bemanian MH, et al. Evaluation of a new protocol for wheat desensitization in patients with wheat-induced anaphylaxis. Immunotherapy. 2017, 9, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaie D, Ebisawa M, Soheili H, et al. Oral wheat immunotherapy: long-term follow-up in children with wheat anaphylaxis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2022, 183, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagakura KI, Yanagida N, Sato S, et al. Low-dose-oral immunotherapy for children with wheat-induced anaphylaxis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton OT, Logsdon SL, Zhou JS, et al. Oral immunotherapy induces IgG antibodies that act through FcγRIIb to suppress IgE-mediated hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014, 134, 1310–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Veen W, Stanic B, Yaman G, et al. IgG4 production is confined to human IL-10-producing regulatory B cells that suppress antigen-specific immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013, 131, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri-Aria KT, Wachholz PA, Francis JN, et al. Grass pollen immunotherapy induces mucosal and peripheral IL-10 responses and blocking IgG activity. J Immunol. 2004, 172, 3252–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gri G, Piconese S, Frossi B, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress mast cell degranulation and allergic responses through OX40-OX40L interaction. Immunity. 2008, 29, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua X, Goedert JJ, Pu A, et al. Allergy associations with the adult fecal microbiota: Analysis of the American Gut Project. EBioMedicine. 2016, 3, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling Z, Li Z, Liu X, et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition associated with food allergy in infants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2546–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubeldia-Varela E, Barker-Tejeda TC, Obeso D, et al. Microbiome and allergy: new insights and perspectives. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2022, 32, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweala OI, Nagler CR. The microbiome and food allergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019, 37, 377–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunyavanich S, Berin MC. Food allergy and the microbiome: current understandings and future directions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019, 144, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka M, Korenori Y, Washio M, et al. Signatures in the gut microbiota of Japanese infants who developed food allergies in early childhood. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2017, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Ojalvo D, Berin C, Tordesillas L. Immune basis of allergic reactions to food. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2019, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni Canani R, Sangwan N, Stefka AT, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-supplemented formula expands butyrate-producing bacterial strains in food allergic infants. Isme j. 2016, 10, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja-Bulsa G, Bulsa M. What do we know now about IgE-mediated wheat allergy in children? Nutrients. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Pasha I, Saeed F, Sultan MT, et al. Wheat allergy and intolerence: recent updates and perspectives. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016, 56, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo H, Dahlström J, Tanaka A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of recombinant omega-5 gliadin-specific IgE measurement for the diagnosis of wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Allergy. 2008, 63, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricardi PM, Kleine-Tebbe J, Hoffmann HJ, et al. EAACI molecular allergology user's guide. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27 (Suppl 23), 1–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faihs V, Kugler C, Schmalhofer V, et al. Wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis: subtypes, diagnosis, and management. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023, 21, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo H, Morimoto K, Akaki T, et al. Exercise and aspirin increase levels of circulating gliadin peptides in patients with wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005, 35, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno O, Nomura T, Ohguchi Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin underlie a Japanese family with food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015, 29, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen MJ, Eller E, Mortz CG, et al. Wheat-dependent cofactor-augmented anaphylaxis: a prospective study of exercise, aspirin, and alcohol efficacy as cofactors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019, 7, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Z, Gao X, Li J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis: a retrospective study. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2022, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos AF, Riggioni C, Agache I, et al. EAACI guidelines on the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy. 2023, 78, 3057–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito K, Futamura M, Borres MP, et al. IgE antibodies to omega-5 gliadin associate with immediate symptoms on oral wheat challenge in Japanese children. Allergy. 2008, 63, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scibilia J, Pastorello EA, Zisa G, et al. Wheat allergy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006, 117, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä MJ, Eriksson C, Kotaniemi-Syrjänen A, et al. Wheat allergy in children - new tools for diagnostics. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014, 44, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palosuo K, Varjonen E, Kekki OM, et al. Wheat omega-5 gliadin is a major allergen in children with immediate allergy to ingested wheat. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001, 108, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulmala P, Pelkonen AS, Kuitunen M, et al. Wheat oral immunotherapy was moderately successful but was associated with very frequent adverse events in children aged 6-18 years. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 107, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phisitbuntoon T, Jirapongsananuruk O, Pacharn P, et al. A potential role of gliadin extract skin prick test in IgE-mediated wheat allergy. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2023, 41, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pacharn P, Siripipattanamongkol N, Pannakapitak N, et al. Accuracy of in-house alcohol-dissolved wheat extract for diagnosing IgE-mediated wheat allergy. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2020, 38, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pacharn P, Kumjim S, Tattiyapong P, et al. Identification of wheat sensitization using an in-house wheat extract in Coca-10% alcohol solution in children with wheat anaphylaxis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2016, 34, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Constantin C, Quirce S, Poorafshar M, et al. Micro-arrayed wheat seed and grass pollen allergens for component-resolved diagnosis. Allergy. 2009, 64, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson N, Nilsson C, Ekoff H, et al. Grass-allergic children frequently show asymptomatic low-level IgE co-sensitization and cross-reactivity to wheat. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018, 177, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keet CA, Matsui EC, Dhillon G, et al. The natural history of wheat allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009, 102, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja-Bulsa G, Bulsa M. The natural history of IgE mediated wheat allergy in children with dominant gastrointestinal symptoms. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2014, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatham AS, Shewry PR. Allergens to wheat and related cereals. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008, 38, 1712–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park HJ, Kim JH, Kim JE, et al. Diagnostic value of the serum-specific IgE ratio of ω-5 gliadin to wheat in adult patients with wheat-induced anaphylaxis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012, 157, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherf KA, Brockow K, Biedermann T, et al. Wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016, 46, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita E, Matsuo H, Mihara S, et al. Fast omega-gliadin is a major allergen in wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. J Dermatol Sci. 2003, 33, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daengsuwan T, Palosuo K, Phankingthongkum S, et al. IgE antibodies to omega-5 gliadin in children with wheat-induced anaphylaxis. Allergy. 2005, 60, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson N, Sjölander S, Baar A, et al. Wheat allergy in children evaluated with challenge and IgE antibodies to wheat components. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015, 26, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi H, Matsuo H, Chinuki Y, et al. Recombinant high molecular weight-glutenin subunit-specific IgE detection is useful in identifying wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis complementary to recombinant omega-5 gliadin-specific IgE test. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012, 42, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabler AM, Gebhard J, Eberlein B, et al. The basophil activation test differentiates between patients with wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis and control subjects using gluten and isolated gluten protein types. Clin Transl Allergy. 2021, 11, e12050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinuki Y, Yagami A, Adachi A, et al. In vitro basophil activation is reduced by short-term omalizumab treatment in hydrolyzed wheat protein allergy. Allergol Int. 2020, 69, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinuki Y, Kohno K, Hide M, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in adult patients with wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis: Reduction of in vitro basophil activation and allergic reaction to wheat. Allergol Int. 2023, 72, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindher SB, Long A, Chin AR, et al. Food allergy, mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment: Innovation through a multi-targeted approach. Allergy. 2022, 77, 2937–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuda R, Nagao M, Hiraguchi Y, et al. Antigen-induced expression of CD203c on basophils predicts IgE-mediated wheat allergy. Allergol Int. 2009, 58, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinuki Y, Kaneko S, Dekio I, et al. CD203c expression-based basophil activation test for diagnosis of wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012, 129, 1404–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahri R, Custovic A, Korosec P, et al. Mast cell activation test in the diagnosis of allergic disease and anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018, 142, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds S, Liu EG, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Wheat oral immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021, 21, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsitz D, Biedermann T, Brockow K. Sublingual immunotherapy reduces reaction threshold in three patients with wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Allergy. 2021, 76, 3804–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke P, Orsini F, Lozinsky AC, et al. Probiotic peanut oral immunotherapy versus oral immunotherapy and placebo in children with peanut allergy in Australia (PPOIT-003): a multicentre, randomised, phase 2b trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022, 6, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez del Río P, Díaz-Perales A, Sanchez-García S, et al. Oral immunotherapy in children with IgE-mediated wheat allergy: outcome and molecular changes. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014, 24, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Utsunomiya T, Imai T, et al. Wheat oral immunotherapy for wheat-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015, 136, 1131–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayatzadeh A, Gharaghozlou M, Ebisawa M, et al. A Safe and Effective Method for Wheat Oral Immunotherapy. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 15, 525–535. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Wood RA, Nadeau KC, et al. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of vital wheat gluten oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019, 143, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura K, Yanagida N, Sato S, et al. Evaluation of oral immunotherapy efficacy and safety by maintenance dose dependency: A multicenter randomized study. World Allergy Organ J. 2020, 13, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagakura KI, Yanagida N, Miura Y, et al. Long-term follow-up of fixed low-dose oral immunotherapy for children with wheat-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022, 10, 1117–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura S, Kitamura K, Makino A, et al. Slow low-dose oral immunotherapy: threshold and immunological change. Allergol Int. 2020, 69, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafian S, Amirzargar A, Gharagozlou M, et al. The efficacy of a new protocol of oral immunotherapy to wheat for desensitization and induction of tolerance. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022, 21, 232–240. [Google Scholar]

- Pourvali A, Arshi S, Nabavi M, et al. Sustained unresponsiveness development in wheat oral immunotherapy: predictive factors and flexible regimen in the maintenance phase. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023, 55, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 84. Christensen MJ, Eller E, Mortz CG, et al. Clinical and serological follow-up of patients with WDEIA. Clin Transl Allergy.

- Makita E, Yanagida N, Sato S, et al. Long-term prognosis after wheat oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020, 8, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta T, Tanaka K, Tagami K, et al. Exercise-induced allergic reactions on desensitization to wheat after rush oral immunotherapy. Allergy. 2020, 75, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota S, Kitamura K, Matsui T, et al. Exercise-induced allergic reactions after achievement of desensitization to cow's milk and wheat. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021, 32, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacharn P, Siripipattanamongkol N, Veskitkul J, et al. Successful wheat-specific oral immunotherapy in highly sensitive individuals with a novel multirush/maintenance regimen. Asia Pac Allergy. 2014, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Design | Patients treated with OIT, n | Age, mean (range) | Form ofwheat use | Up-dosing phase | Maintenance phase | Target dose | Changes in SPT scores(mean/median) | Changes in sIgE (mean/median) | Changes in sIgG(mean/median) | Efficacy after OIT, %desensitization | Efficacy after OIT, %sustained unresponsiveness | Adverse reaction (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez del Río (2014) [75] | Open-label,nonrandomized, no control | 6 | 5.5 (5-11) years | Semolina porridge andboiled semolina pasta | 3-24 days | 6 months | 13 g of WP | No significant changes but showed a trend (6 mm vs 2 mm) after 6 months | No significant changes in sIgE to wheat but showed a trend of increase after up-dosing, followed by a decrease after 6-month follow-up (47.5 vs 84.55 vs 28.75 kUA/L) | Increased sIgG4 and sIgG1 to wheat and a panel of wheat proteins in all patients after 6 months | 83% | Not assessed | 6.25% of doses during up-dosing, none treated with IM epi | |

| Sato (2015) [76] | Open-label,nonrandomized, historical control | 18 | 9.0 (5.9-13.6) years | Boiled udon noodles | 5 days | >3 months | 5.2 g of WP | Not assessed | Decreased sIgE to wheat (>100 vs 43.5 kU/L) after 2 years | Not assessed | 88.9% | OIT: 61.1%Historical control: 9.1% | 26.4% of inpatient doses, 6.8% of outpatient doses with 1 treated with IM epi | |

| Khayatzadeh (2016) [77] | Open-label,nonrandomizednon-placebo control | Rush method: n=8Outpatient method: n=5 | 7 (5.5-19) years | Bread | Rush method: 3-6 daysOutpatient method: 66-87 days | 3 months | 5.2 g of WP | Rush method: decreased (9 mm vs 6.6 mm) after 3 months;Outpatient method: decreased (9 mm vs 6.8 mm) after 5 months | Not available | Not assessed | 92.3% | Not assessed | Rush method: 29.6% of doses during up-dosing, with 5.6% treated with IM epiOutpatient method: 2.5% of doses during up-dosing, none treated with IM epi | |

| Rekabi (2017) [21] | Open-label,nonrandomized, no control | 12 | 2.25 (2-10) years | Semolina flour andspaghetti (containing pasta) | 6.5 months | 18 months | 70 g of pasta | Decreased (10 mm vs 3 mm) after 2 years | Decreased total IgE (490 vs 338.5 IU/mL) after 2 years.sIgE to wheat increased after desensitization, followed by a decrease after follow-up phase (55.9 vs 65.1 vs 4.6 IU/mL) | Not assessed | 100% | Not assessed | 0.06% of doses during up-dosing | |

| Kulmala (2018) [50] | Multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized, no control | 100 | 11.6 (6.1-18.6) years | Boiled wheat spaghetti | 4.3 months | 12 months | 2 g of WP | Not assessed | Three samples available showed decreased sIgE to wheat, gluten, and ω-5 gliadin after OIT | Not assessed | 57% | Not assessed | 94% of patients, 11 patients used 12 doses of IM epi | |

| Nowak-Węgrzyn (2019) [78] | Multicenter,double-blind,randomized,placebo-control | Low dose group: n=23Placebo group: n=23, then crossed-over to high dose after 1 year | 8.7 (4.2-22.3) years | Vital wheat gluten | 11 months | 2-14 months | Low dose: 1445 mg of WPHigh dose: 2748 mg of WP | No significant differences in SPT scores between groups at year 1 | No significant differences in sIgE to wheat and ω-5 gliadin between groups at year 1 | Increased sIgG4 to wheat and ω-5 gliadin in OIT group at year 1 | Placebo group: 0% after 1 year Low dose: 30.4% after 2 years;High dose: 57.1% after 1 year | Low dose: 13.0% after 2 years | Low dose: 15.4% of doses at year 1 with 0.08% treated with IM epi, 3.1% at year 2 and none treated with IM epi;High dose: 13.4% of doses after 1 year with 0.07% treated with IM epi | |

| Nagakura (2020) [23] | Open-label,nonrandomized,historical control | 16 | 6.7 (5.8-10.7) years | Boiled udon noodles | 1 month | 11 months | 53 mg of WP | Not assessed | Decreased sIgE to wheat (293 vs 153.5 kUA/L) and ω-5 gliadin (7.5 vs 4.1 kUA/L) after 1 year | Increased sIgG to wheat (19.8 vs 24.1 mgA/L) and ω-5 gliadin (6.0 vs 7.3 mgA/L) after 1 month. Increased sIgG4 to wheat (2.07 vs 4.7 mgA/L) and ω-5 gliadin (0.07 vs 0.09 mgA/L) after 1 month | 88% | OIT: 69%Historical control: 9% | 32.1% of inpatient doses and 4.1% of outpatient doses, none treated with IM epi | |

| Ogura (2020) [79] | Multicenter, open-label,randomized,non-placebo control | Low dose group: n=12High dose group: n=12 | Low dose group: 5.5 (4.5-5.8) yearsHigh dose group: 5.0 (3.7-5.5) years | Boiled udon noodles, boiled pasta and bread | 24 months | Low dose: 650 mg of WP; High dose: 2.6 g of WP | Not assessed | Decreased sIgE to wheat after 1 year in both groups and decreased sIgE to ω-5 gliadin in low dose group | No changes in sIgG and sIgG4 to wheat or ω-5 gliadin in both groups | Low dose group: 66.7%;High dose group: 33.3% at year 1 | Low dose group: 16.7% at year 1, 58.3% at year 2;High dose group: 50.0% at year 1, 58.3% at year 2 | Low dose group: 4.76% of doses with 0.02% treated with IM epi;High dose group: 8.82% of doses, none treated with IM epi | ||

| Sugiura (2020) [81] | Open-label,nonrandomized,non-placebo control | 35 | 5 (4-6) years | Boiled udon and somen noodles | 12 months | 10 times greater than the initial dose | Not assessed | Decreased sIgE to wheat (97.0 vs 51.9 UA/mL) and ω-5 gliadin (4.8 vs 1.4 UA/mL) after 12-15 months | Not assessed | OIT: 37.5%Control (wheat avoidance): 10.0% | Not assessed | 0.64% of doses, none treated with IM epi | ||

| Babaie (2022) [22] | Open-label,nonrandomized, no control | 20 | 6 (2-17) years | Cake and bread | Not mentioned | 3-27 months | 5.28 g of WP | Decreased (9.8 mm vs 4.3 mm) after 3-month maintenance phase | sIgE to wheat increased after up-dosing, followed by a decrease after 3-month maintenance phase | Not assessed | Not mentioned | 47.1% after 3 months, 82.4% after 15 months, 100% after 27 months | 7.2% of doses during up-dosing, with 0.4% treated with IM epi | |

| Nagakura (2022) [80] | Open-label,nonrandomized, historical control | 29 | 6.7 (6.3-7.9) years | Boiled udon noodles | 1 month | 35 months | 53 mg of WP | Not assessed | Decreased sIgE to wheat (278 vs 89.3 kUA/L), gluten (358 vs 86.9 kUA/L), and ω-5 gliadin (12.7 vs 3.5 kUA/L) after 3 years | Not assessed | 100% | OIT: 7% at year 1, 28% at year 2, 41% at year 3;Historical control: 0% | 7.7% of doses at year 1, 3.9% at year 2, 2.4% at year 3, and 0.03% treated with IM epi at year 1 | |

| Sharafian (2022) [82] | Open-label,nonrandomized, no control | 26 | 6.2 (4-11) years | Bread | 6 days | 12 months | 5.2 g of WP | Not assessed | Decreased sIgE to wheat (90.4 vs 66.5 IU/mL) after 1 year | Not assessed | 100% | 93.3% | 21.4% of doses, 23.8% of reactions treated with IM epi | |

| Pourvali (2023) [83] | Open-label,nonrandomized, no control | 19 | 6.6 (2.4-16.6) years | Bread and boiled spaghetti | 6-7.5 months | 7-9 months | 5-10 g of WP | No changes after OIT | Decreased sIgE to wheat (108 vs 24.6 kU/L) after OIT | No changes in sIgG4 to wheat after OIT | 68.4% | 68.4% | Not mentioned | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).