Submitted:

07 December 2023

Posted:

08 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

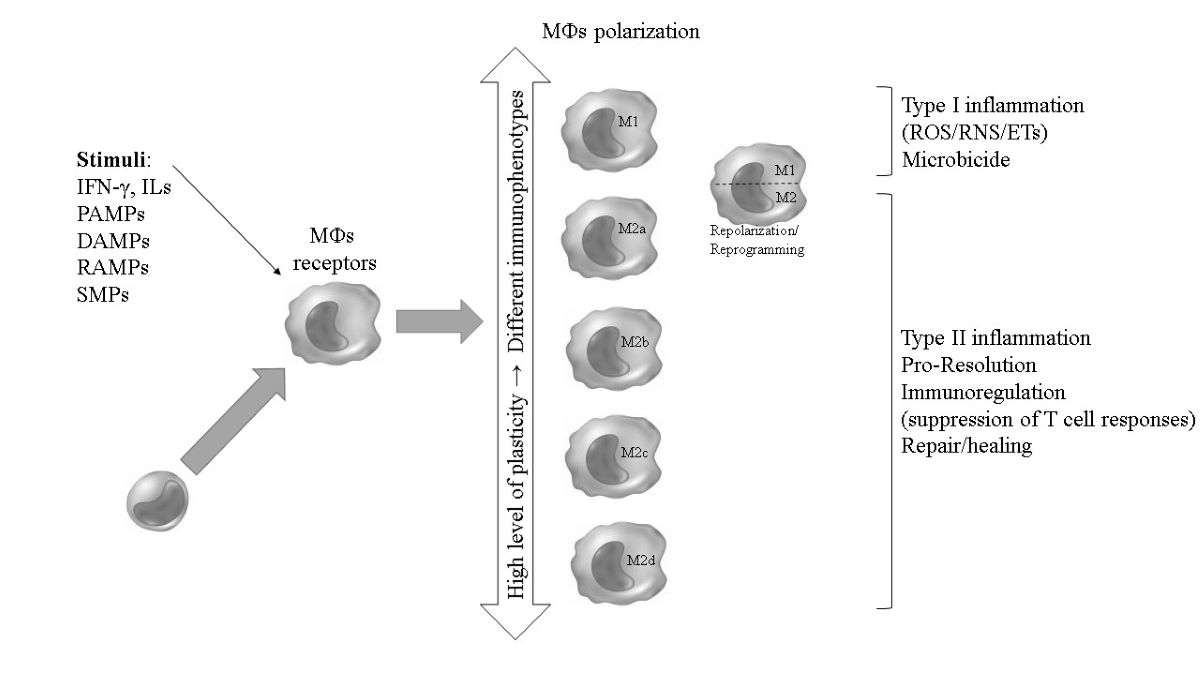

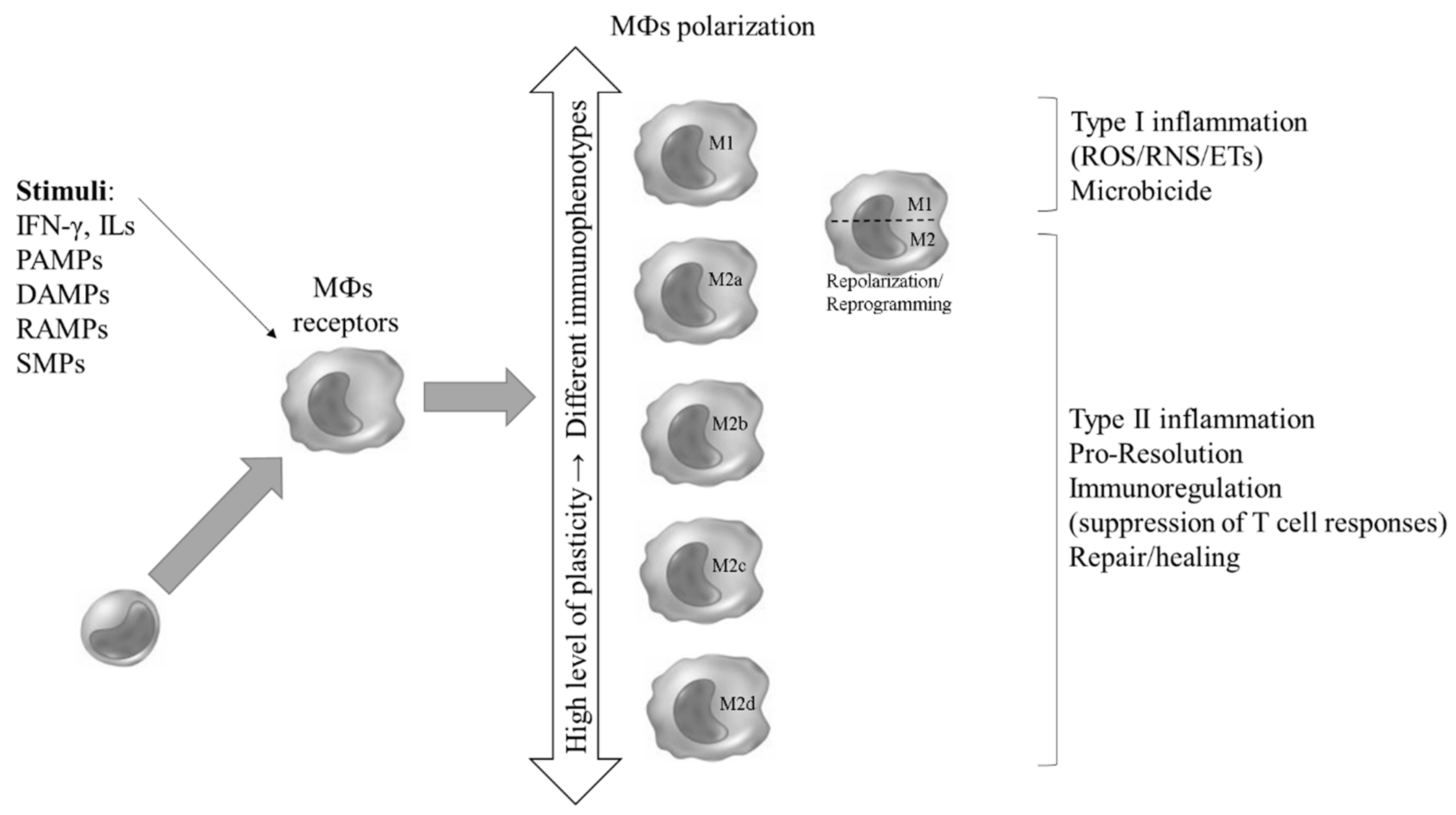

2. MOs, MФs and polarization: an overview

| Location* | Resident cells | Main microorganisms (stimuli/tropism) that activate the response |

| CNS (brain) | Microglia** |

Toxoplasma gondii, Schistosoma spp., Cryptococcus neoformans, virus, and bacteria |

| Bones | Osteoclasts*** | Anaerobic microorganisms, S. aureus |

| Heart/vessels | Resident cardiac MФs | Trypanosoma cruzi, Streptococcus spp., Candida albicans, Staphylooccus aureus |

| Liver | Kupffer cells | Plasmodium spp., Trypanosoma spp., Schistosoma spp., HAV, HBV, HCV, S. aureus |

| Lungs | Alveolar MФs | Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), Aspergillus fumigatus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, C. neoformans, Streptococcus spp., SARS-CoV e SARS-CoV-2, other viruses |

| Adipose tissue**** | Adipose tissue MФs | Brucella spp., parasites, SARS-CoV-2 |

| Connective tissue | Histiocytes | Pathogens in general |

| Intestine/ Peritoneum | MФs associated with the intestine/Peritoneal MФs | Enterobacteriacae, some viruses, parasites in general; immunotolerance to commensals |

| Kidneys | Mesenchymal cells | Virus and bacteria |

| Spleen | Red pulp MФs (RPMs) | Plasmodium spp., parasites, and microbes of blood origin |

| Skin/Epidermis | Langerhans cells/ Dendritic cells (DCs-MOs) |

Staphylooccus spp., Mycobacterium leprae, Leishmania spp., Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Candida spp. |

2.1. Stimuli for the activation of polarization

| PAMP/DAMP RAMP/SPM |

Origin | Macrophage receptors/location | Macrophage action |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPS, spike, formyl peptides, flagellin, high mannose, chitin, β-glucans, ss/dsRNA, cpg dna | Lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids from microorganisms | PRRs: TRLs (2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11) and CLRs (membrane-bound) and NLRs/RLRs (cytoplasmic); Dectin-1 | Proinflammatory PAMPs. |

| DNA, RNA, IL-1A/B, histones, HSPS, uric acid, oxidized phospholipids, decorin, fibronectin | Nucleus, cytoplasm, plasma membrane and extracellular matrix of the dying cell | PRRs (TLRs 2, 4, 7, 8, and 9), RAGE, NLRP, CDs, P2X7, ↑IL1RLI, IL1RLII | DAMPs with inflammation-inducing activities. |

| HSP10, HSP27 | Dying cell, tissue-resident cells | TLR4, CD36, MSR, MERTK, PTGERE | Pro-resolution RAMPs. |

| lipoxins, resolvins, protectins, maresins | Efferocytes, tissue resident mesenchymal stromal cells | LGR, GPRs (18, 32, and 37), ALX, ERV | SPMs with resolution-inducing activities. |

| HMGB1, ↑[ATP], IL-33, PGE2, annexin1 | Dying cell |

TLR 2, 4, 5, RAGE, TREM-1, EP2, 4, ST2, FPR2 | DAMPs and RAMPs acting in the transition from inflammation to resolution |

| Phenotype | Activation/ Stimulus |

Markers | Immune signaling and molecules/functionally: Transcriptional profile and cytokine/chemokine production | Profile functional of the phenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| M1 | IFN-γ;a PAMPs/LPS; GM-CSF; other TLR ligands |

CDs 68, 80, 86; MHC II; |

↑iNOS; TLR2, TLR4; ILs-1β, 6, 8, 12, and 23; TNF-α, IFN-γ; CXCL 8, 9, 10, 11, and 16; CCL 2, 3, and 5; |

Microbicide Type I inflammation Inflammasome ↑Oxidative burst (ROS/RNS) ↑ETs M1/Th 1,17 responses |

|

| M2a | ILs-4 and -13; Fungi/ Helminths |

CDs 23, 163 e 200R | ↑ARG1; IGF1; DecoyR; ILs-1r, and10; TGF-β; IL-CCL17, 22, and 24; |

Resolution of infection Killing and encapsulation of parasites Allergy M2/Th2 responses Type II inflammation |

|

| M2b | IC+TLR/ (Ac-Ag); IL-1R IL-1β LPS |

CD86 MHC II |

↑eNOS; CCL1; ILs- 1, 6, 10 , and 16; TNF-α |

Resolution of infection/inflammation Immunoregulation M2/Th2 responses |

|

| M2c | IL- 10; TGF-β; Glucocorticoids | CD163 TLR1, R8 |

ILs-1β and 10; TGF-β; CCR2; MMP9; ↑ARG1 |

Immunoregulation (suppression of T cell responses) ↑Repair/healing |

|

| M2d | IL-5; LIF; Adenosine |

VEGF | ILs-10 and 12; TNF-α; TGF-β; CCL5; CXCL10 and 16 | ---- | |

| M4 | ---- | CDs 86 and 206 | TNFα; CCL18 and 20 | ---- | |

| Mhem | ---- | CD 163 | HO-1; IL-10 | ---- | |

| MOx | ---- | ---- | HO-1, SD-1, TR-reductase | ---- | |

2.2. Profile of polarized MФs: development and ramifications in programming and reprogramming sub-populations

2.3. Metabolic programming and transcriptional profile during the differentiation of MOs into MФs and polarization

2.3.1. Differential gene expression and metabolism

2.3.2. Cytokine and chemokine profile during polarization

2.3.3. Reprogramming of the transcriptional and metabolic system and repolarization

2.4. Polarization of tissue MФs

2.5. Functional profile of polarized MФs

2.5.1. Phenotypic subpopulations of M1 MФs: phagocytosis and microbicidal activity (intra- and extracellular killing)

2.5.1.1. Microbicidal activity

2.5.1.1.1. Phagocytosis

2.5.1.1.2. The NADPH oxidase complex: microbicidal profile of oxidants, activation of enzymes with antimicrobial activity and formation of extracellular traps, as well as signaling in the immune system

2.5.1.1.3. Induced nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)

2.5.2. Phenotypic subpopulations of M2 MФs: cytoplasmic and extracellular components and reparative action (resolution of infection and healing)

2.5.2.1. MФs repertoire during tissue repair and regeneration/remodeling

2.5.2.2. Role of extracellular matrix and adjacent cells

3. Immune response via polarized MФs against pathogens in general

3.1. MФs polarization in infectious diseases

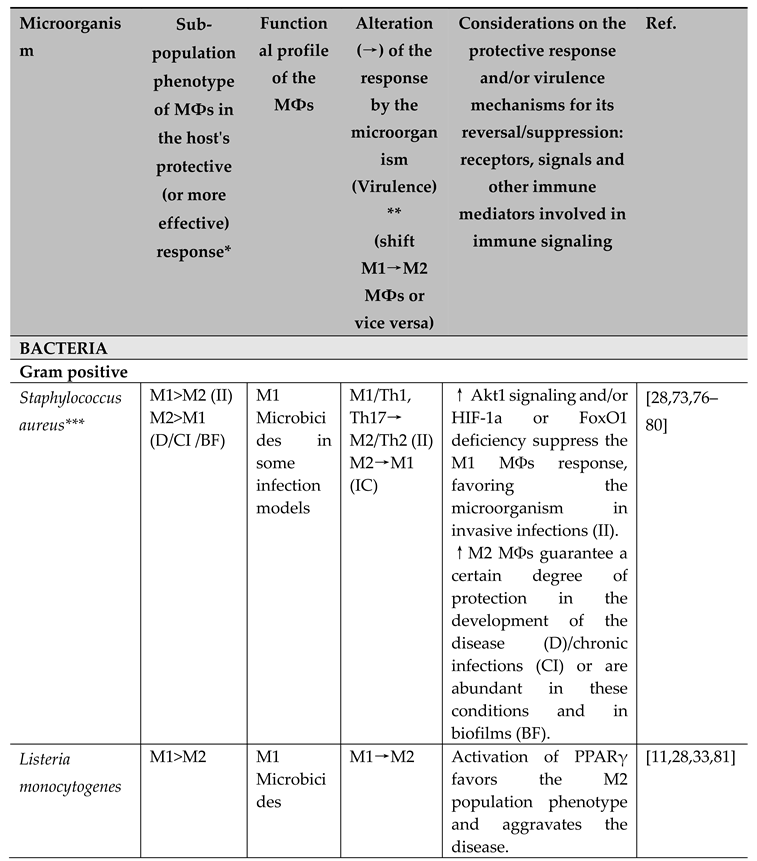

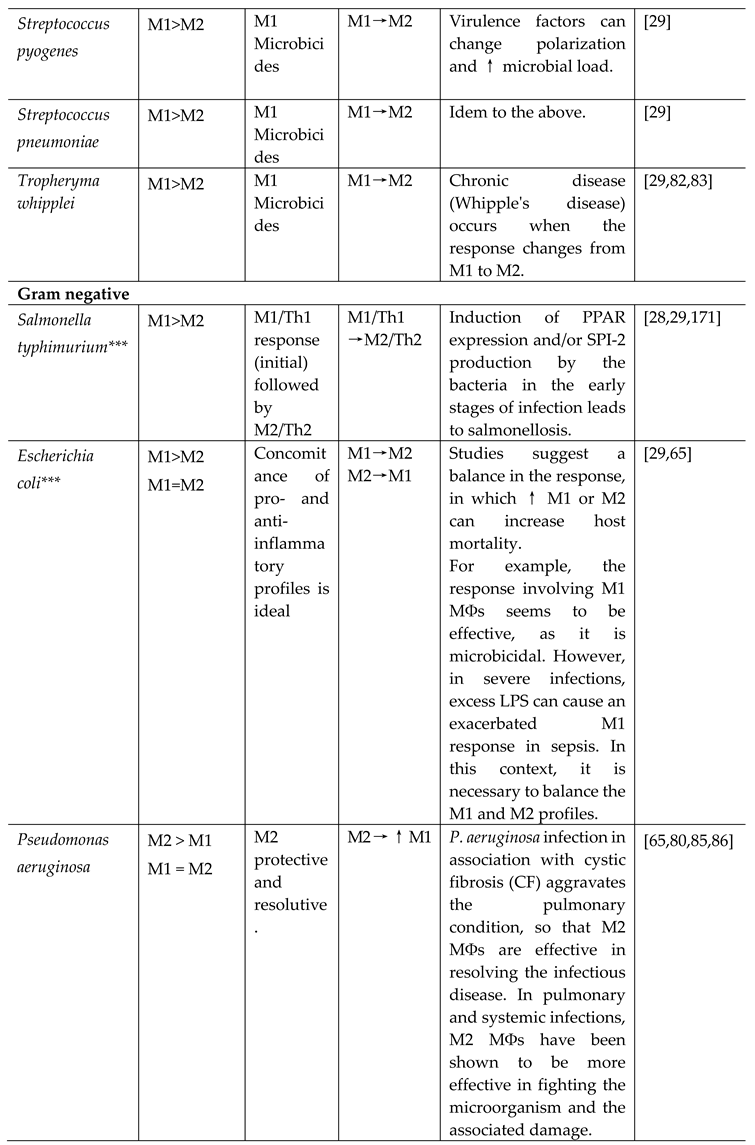

3.1.1. Polarization of MФs in response to infectious diseases caused by bacteria

3.1.1.1. Gram positive bacteria

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Listeria monocytogenes

- Streptococcus spp.

- Tropheryma whipplei

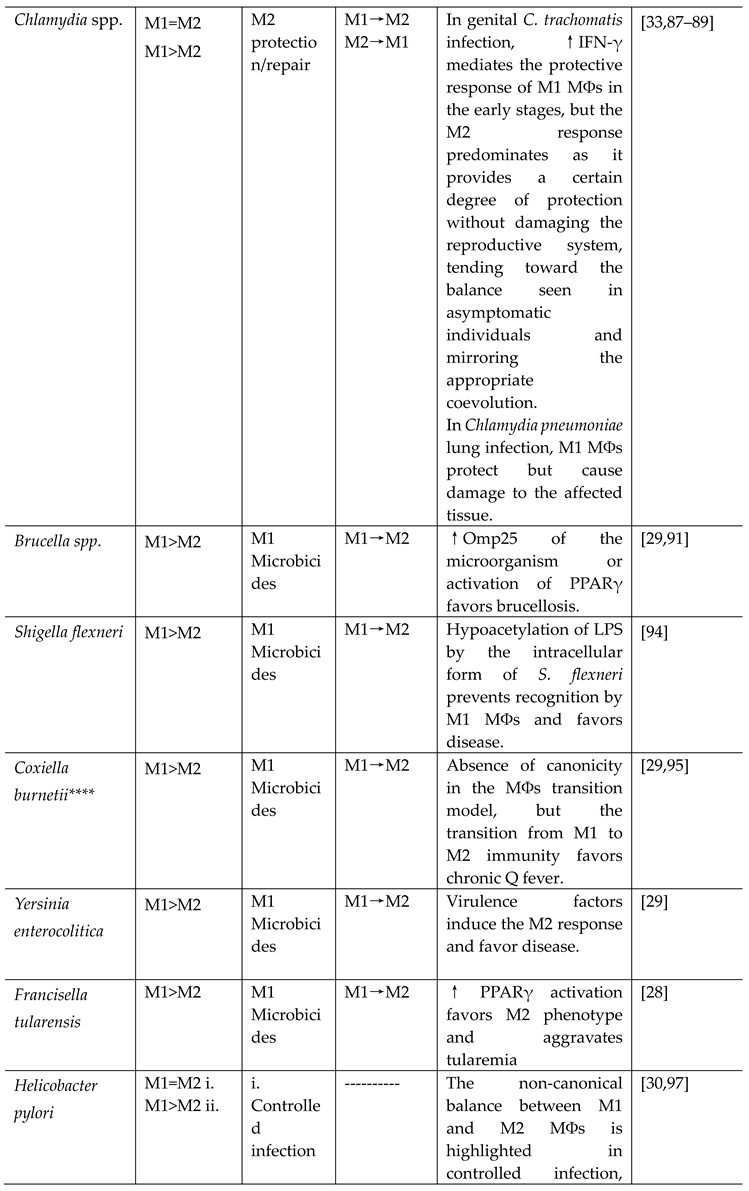

3.1.1.2. Gram negative bacteria

- Salmonella typhimurium

- Escherichia coli

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Chlamydia spp.

- Brucella spp.

- Shigella flexneri

- Coxiella burnetii

- Yersinia enterocolitica

- Francisella spp.

- Helicobacter pylori

- Vibrio cholerae

- Haemophilus spp.

- Borrelia burgdorferi

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

3.1.1.3. Potentially pathogenic microorganisms in the oral cavity (Gram positive or negative)

- Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

- Porphyromonas gingivalis

- Fusobacterium nucleatum

- Prevotella intermedia

- Streptococcus spp.

3.1.1.4. Mycobacteria

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Mycobacterium leprae

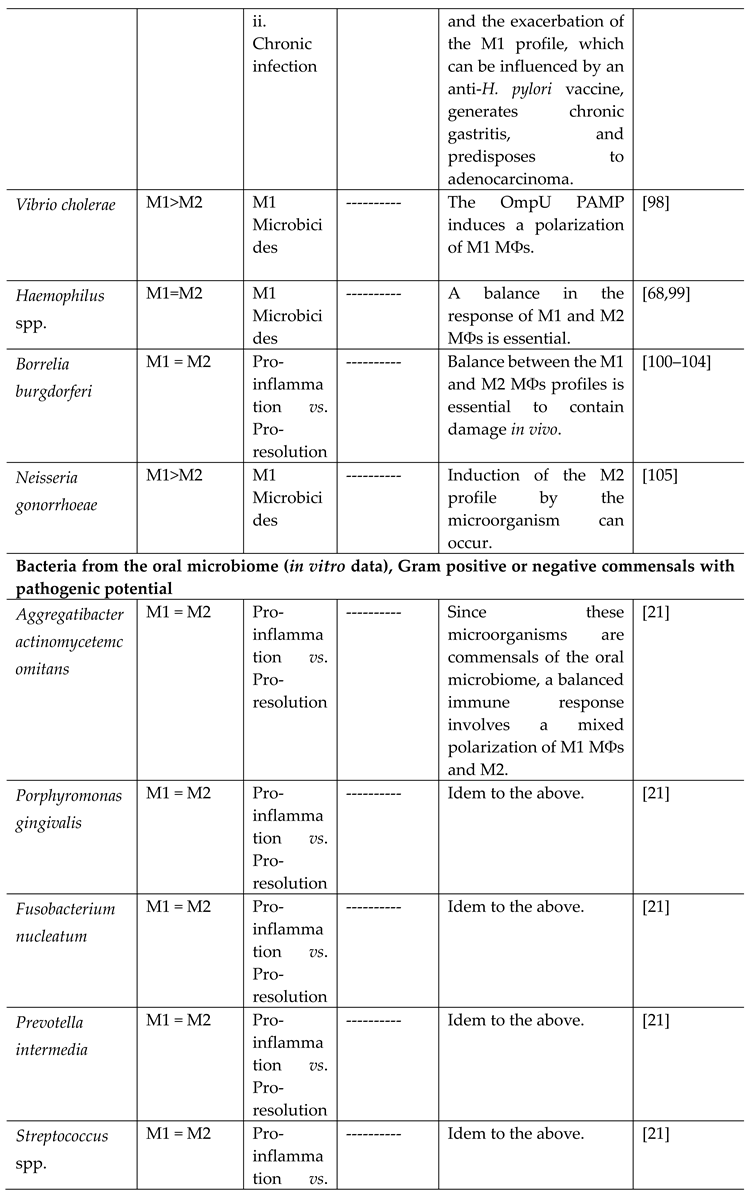

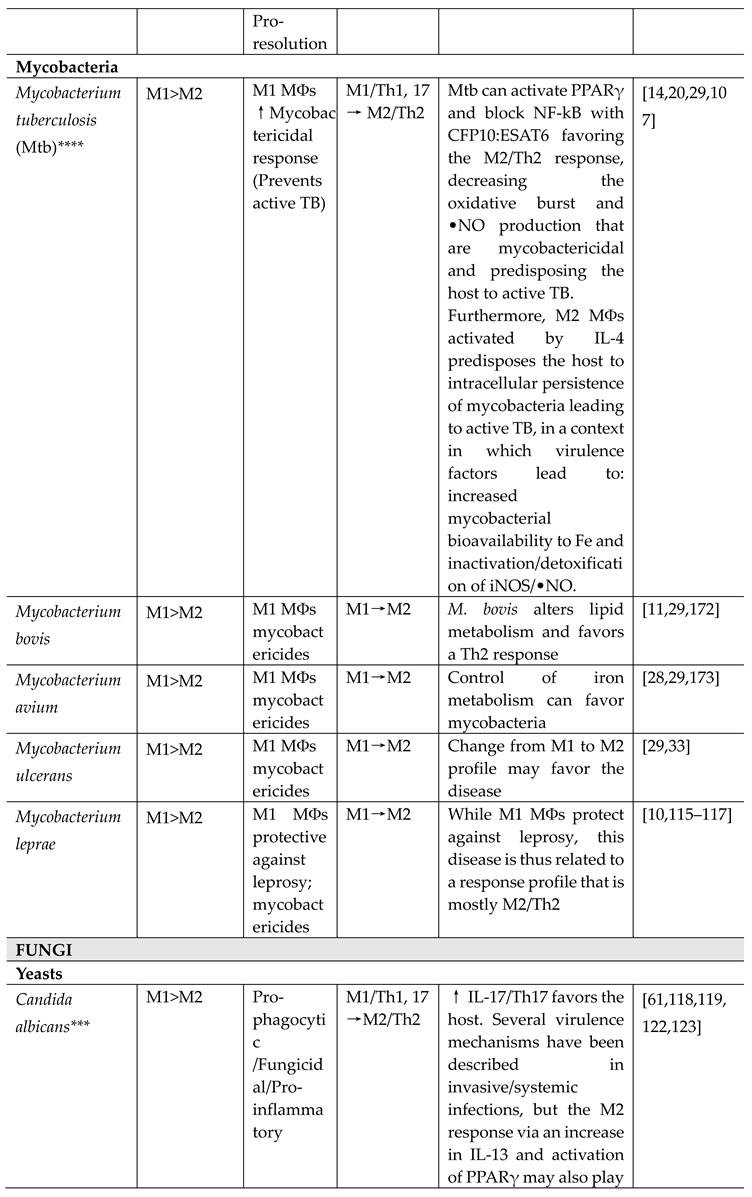

3.1.2. MФs polarization in infectious diseases caused by fungi

- Candida albicans

- Pneumocystis jirovecii

- Cryptococcus neoformans

- Aspergillus fumigatus

- Paracoccidioides brasiliensis

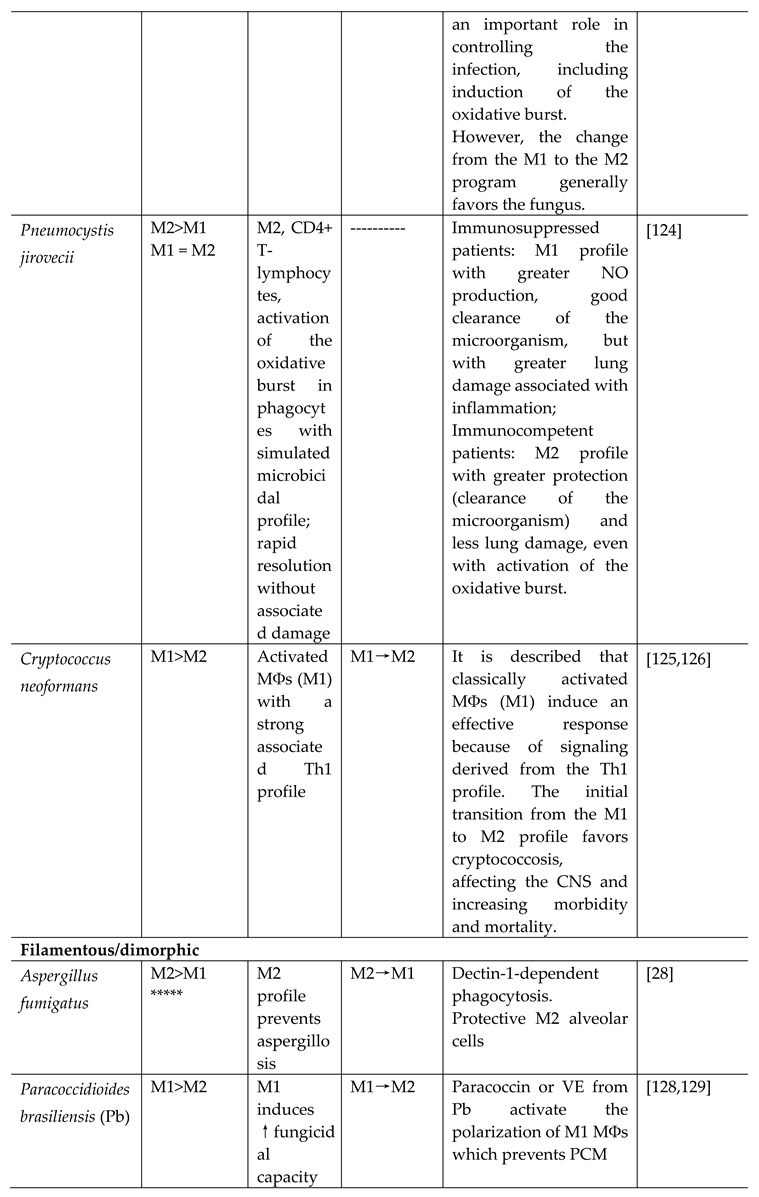

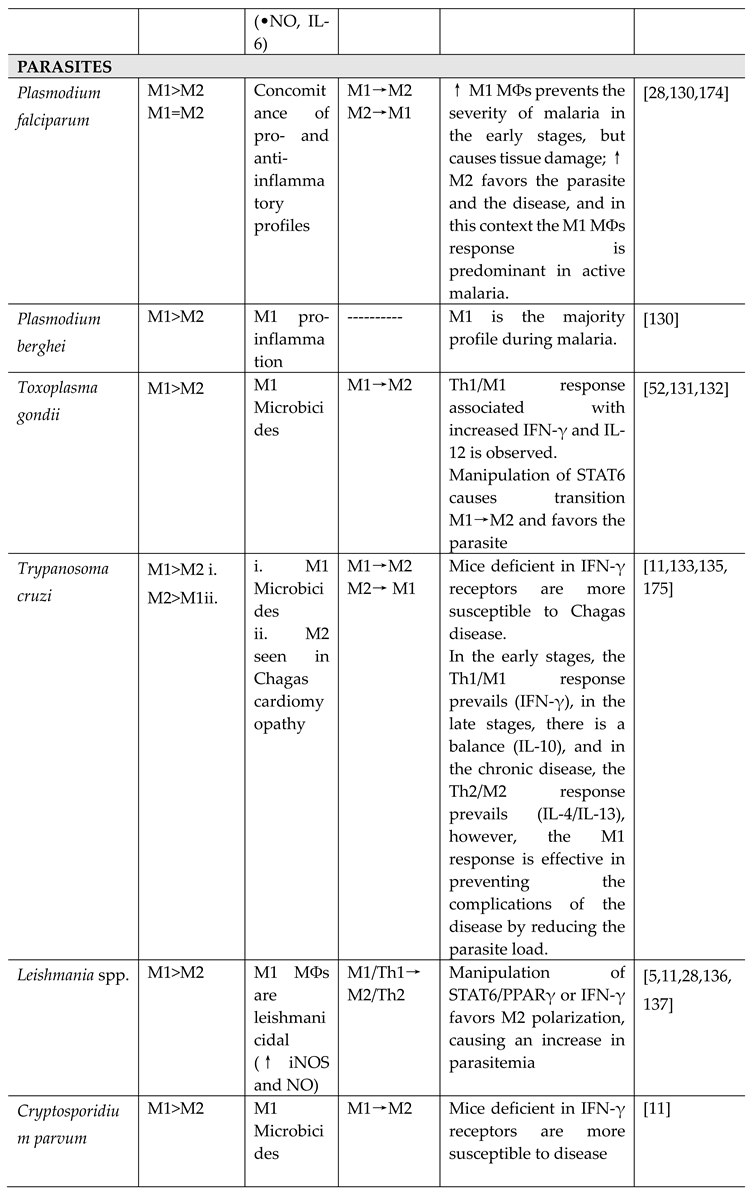

3.1.3. MФs polarization in infectious diseases caused by parasites

- Plasmodium spp.

- Toxoplasma gondii

- Trypanosoma cruzi

- Leishmania spp.

- Cryptosporidium parvum

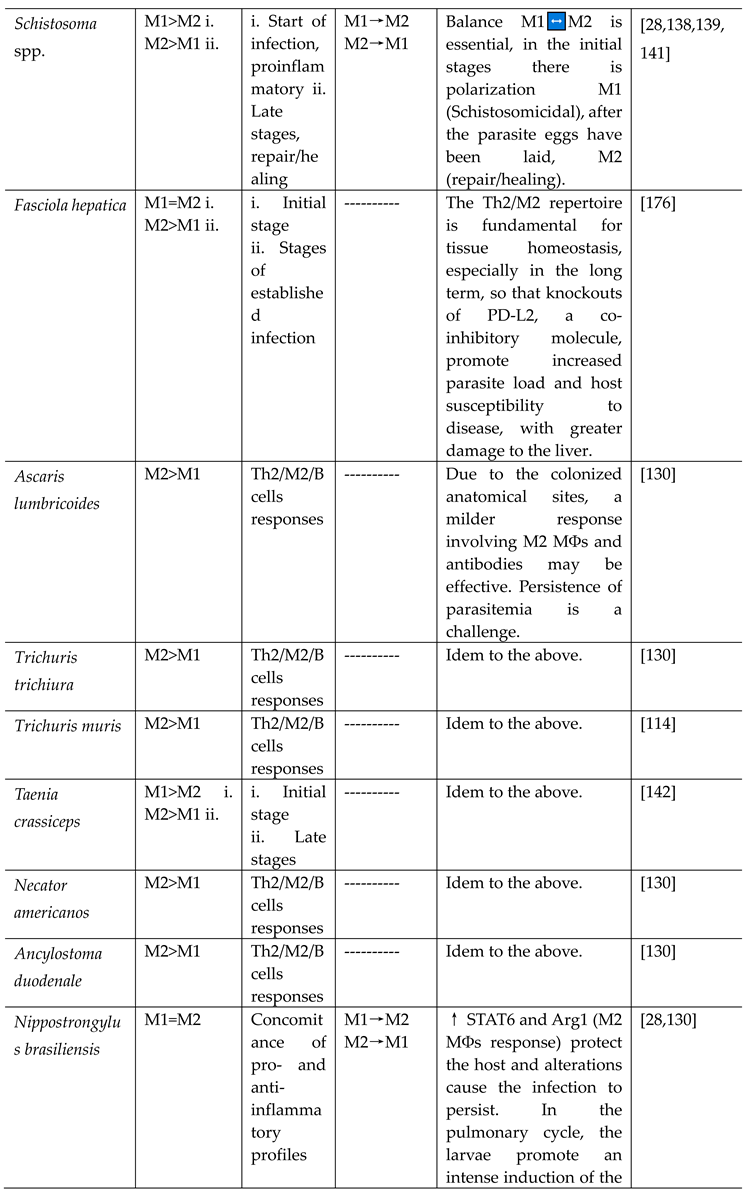

- Schistosoma spp.

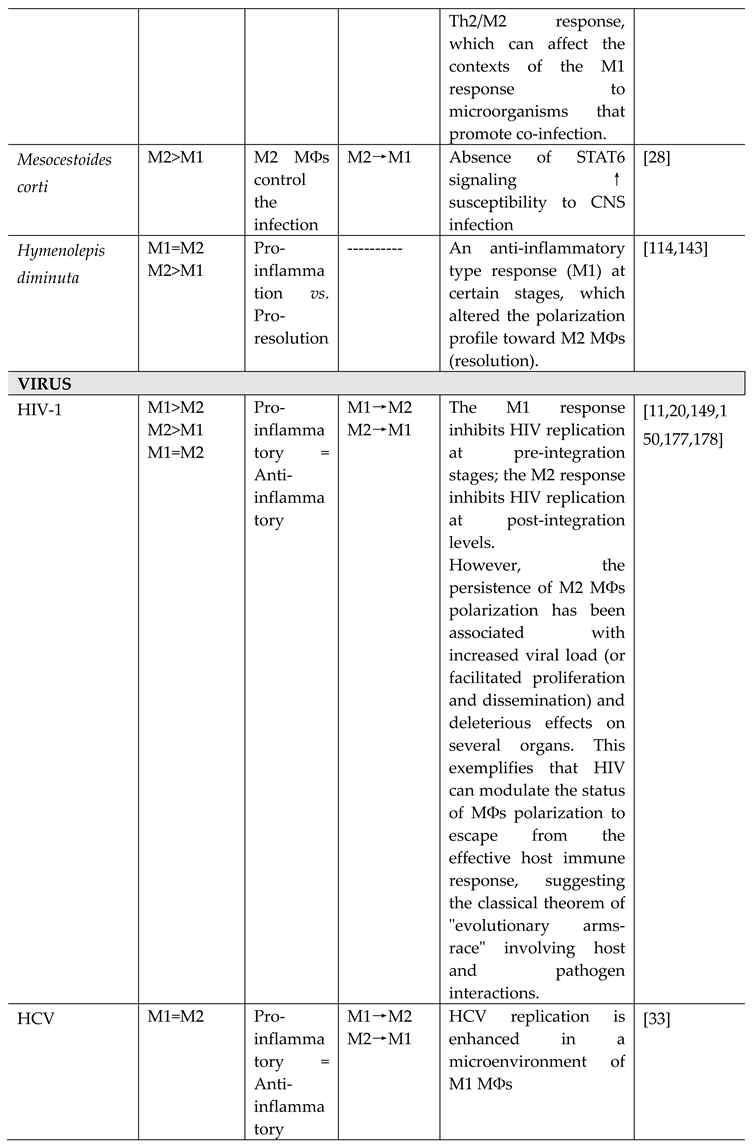

- Other helminths

3.1.4. Polarization of MФs in response to infectious diseases caused by viroses

- HIV-1

- HTLV-1

- HCV

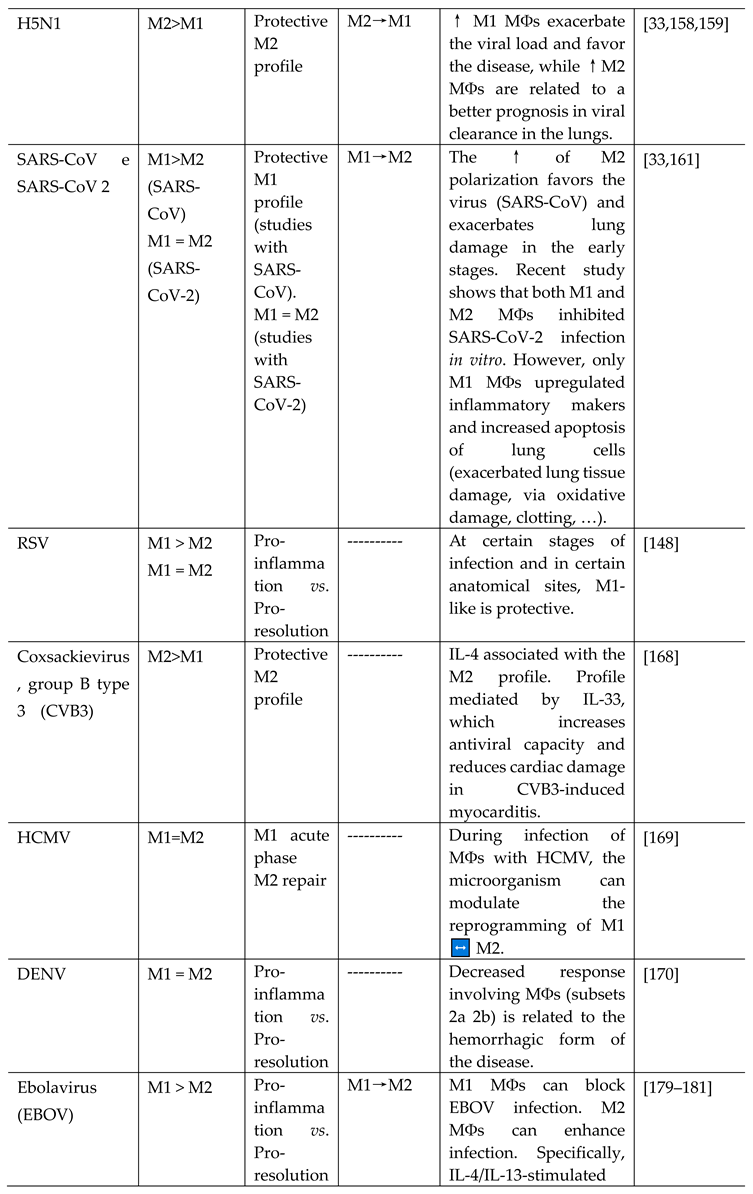

- H5N1

- SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2

- RSV

- Coxsackievirus, group B type 3 (CVB3)

- HCMV

- DENV

|

4. Virulence factors of microorganisms modulating the polarization patterns of MФs

5. Clinical implications of polarization: perspectives for research, diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy of inflammatory and/or infectious diseases

6. Final considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cerdeira, C.D. Complicações e sequelas neurológicas e psiquiátricas da COVID-19: uma revisão sistemática. Vittalle – Revista de Ciências da Saúde 2022, 34, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdeira, C.D.; Pereira de Araújo, M.; Jorge-Ferreira, C.B.R.; Dias, A.L.T.; Brigagão, M.R.P.L. Explorando os estresses oxidativo e nitrosativo contra fungos: um mecanismo subjacente à ação de tradicionais antifúngicos e um potencial novo alvo terapêutico na busca por indutores oriundos de fontes naturais. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Quím. Farm. 2021, 50, 100–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdeira, C.D.; Chavasco, J.K.; Brigagão, M.R.P.L. Tempol decreases the levels of reactive oxygen species in human neutrophils and impairs their response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Quím. Farm. 2022, 51, 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdeira, C.D.; da Silva, J.J.; Netto, M.F.R.; Boriollo, M.F.G.; Santos, G.B.; dos Reis, L.F.C.; Brigagão, M.R.P.L. Talinum paniculatum leaves with in vitro antimicrobial activity against reference and clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus interfere with oxacillin action. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Quím. Farm. 2020, 49, 432–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, C.F.; Souza, A.S.; Diniz, A.G.; Carvalho, N.B.; Santos, S.B.; Carvalho, E.M. Functional Activity of Monocytes and Macrophages in HTLV-1 Infected Subjects. Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, B.; Ardavín, C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells in innate and adaptive immunity. Immunology and Cell Biology 2008, 86, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koncz, G.; Jenei, V.; Tóth, M.; Váradi, E.; Kardos, B.; Bácsi, A.; Mázló, A. Damage-mediated macrophage polarization in sterile inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1169560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro, M.S.; Miyazawa, M.; Nogueira, E.S.C.; Chavasco, J.K.; Brancaglion, G.A.; Cerdeira, C.D.; et al. Photobiomodulation enhances the Th1 immune response of human monocytes. Lasers in Medical Science 2022, 37, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka, M.B.; Daumas, A.; Textoris, J.; Mege, J.L. Phenotypic diversity and emerging new tools to study macrophage activation in bacterial infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Reports 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T.R.; Cherwinski, H.; Bond, M.W.; Giedlin, M.A.; Coffman, R.L. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J. Immunol. 1986, 136, 2348–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, F.L.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Becher, B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nature, 2016, 16, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatano, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Tomioka, H. Unique Macrophages Different from M1/M2 Macrophages Inhibit T Cell Mitogenesis while Upregulating Th17 Polarization. Scientific Reports 2014, 4, 4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, C.D.; Kincaid, K.; Alt, J.M.; Hill, A. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 6166–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, J.Y.; Michaeli, J.; Assi, S.; et al. Phenotypic diversity and plasticity in circulating neutrophil subpopulations in cancer. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Ma, L.; Deng, D.; Zhang, T.; Han, L.; Xu, F.; Huang, S.; Ding, Y.; Chen, X. M2 macrophage polarization: a potential target in pain relief. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1243149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Galán, L.; Olleros, M.L.; Vesin, D.; Garcia, I. Much more than M1 and M2 macrophages, there are also CD169+ and TCR+ macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiani, P.; Boraschi, D. From monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Frontiers in Immunology 2014, 5, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Villarino, G.; Vérollet, C.; Maridonneau-Parini, I.; Neyrolles, O. Macrophage polarization: convergence point targeted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and HIV. Frontiers in Immunology. 2011, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.B.; Alimova, Y.; Ebersole, J.L. Macrophage polarization in response to oral commensals and pathogens. Pathogens and Disease 2016, 74, ftw011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, C.F. Metchnikoff’s legacy in 2008. Nature Immunol 2008, 9, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ransohoff, R.M. A polarizing question: do M1 and M2 microglia exist? Nature Neuroscience 2016, 19, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; Martinez, F.O. Alternative Activation of Macrophages: Mechanism and Functions. Immunity 2010, 32, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montenegro-Burke, J.F.; Sutton, J.A.; Rogers, L.M.; et al. Lipid profiling of polarized human monocyte-derived macrophages. Prostaglandins & other Lipid Mediators 2016, 127, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Fernando, O.; Siamon, G.; Mantovani, A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte- to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.:1950) 2006, 177, 7303–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K.; Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nature Immunology 2010, 11, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraille, E.; Leo, O.; Moser, M. Th1/Th2 paradigm extended: macrophage polarization as an unappreciated pathogen-driven escape mechanism? Frontiers in Immunology 2014, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, M.; Desnues, B. ; Mege, J-L. Macrophage Polarization in Bacterial Infections. J Immunol, 2008; 181, 3733–3739. [Google Scholar]

- Quiding-Järbrink, M.; Raghavan, S.; Sundquist, M. Enhanced M1 Macrophage Polarization in Human Helicobacter pylori-Associated Atrophic Gastritis and in Vaccinated Mice. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Li, Q.; Ma, J.; et al. IRAK-M alters the polarity of macrophages to facilitate the survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Microbiology 2017, 17, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Sinha, M.; Datta, S.; et al. Monocyte and Macrophage Plasticity in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. The American Journal of Pathology 2015, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labonte, A.C.; Tosello-Trampont, A.-C.; Hahn, Y.S. The Role of Macrophage Polarization in Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases. Mol. Cells. 2014, 37, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galván-Peña, S.; O’Neill, L.A.J. Metabolic reprograming in macrophage polarization. Frontiers in Immunology 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhas, U.; Ryba-Stanisławowska, M.; Szargiej, P.; et al. Different pathways of macrophage activation and polarization. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. (online) 2015, 69, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.A. Arginine metabolism: boundaries of our knowledge. J Nutr 2007, Suppl 2, 1602S–1609S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.L.; O’Neill, L.A. Reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism in macrophages as an anti-inflammatory signal. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016, 46, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajahn, J.; Franz, S.; Rueckert, E.; et al. Artificial extracellular matrices composed of collagen I and high sulfated hyaluronan modulate monocyte to macrophage differentiation under conditions of sterile inflammation. Biomatter 2012, 2, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogle, M.E.; Segar, C.E.; Sridhar, S.; Botchwey, E.A. Monocytes and macrophages in tissue repair: Implications for immunoregenerative biomaterial design. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2016, 241, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzolla, A.; Hultqvist, M.; Nilson, B.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Produced by the NOX2 Complex in Monocytes Protect Mice from Bacterial Infections. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 5003–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, C.; Röllinghoff, M.; Diefenbach, A. Reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen intermediates in innate and specific immunity. Current Opinion in Immunology 2000, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.-W.; Jacobs Jr, W.R. Mycobacterium tuberculosis exploits human interferon γ to stimulate macrophage extracellular trap formation and necrosis. JID 2013, 208, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Junior, E.B.; Bustamante, J.; Newburger, P.E.; et al. The Human NADPH Oxidase: Primary and Secondary Defects Impairing the Respiratory Burst Function and the Microbicidal Ability of Phagocytes. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 2011, 73, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, H.; Araki, A.; Watanabe, H.; Ichinose, A.; Sendo, F. Rapid killing of human neutrophils by the potent activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) accompanied by changes different from typical apoptosis or necrosis. J Leukoc Biol. 1996, 59, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röhm, M.; Grimm, M.J.; D'Auria, A.C.; et al. NADPH oxidase promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation in pulmonary aspergillosis. Infect Immun. 2014, 82, 1766–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoiber, W.; Obermayer, A.; Steinbacher, P.; Krautgartner, W.D. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the Formation of Extracellular Traps (ETs) in Humans. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 702–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, O.A.; Von Kockritz-Blickwede, M.; Bright, A.T.; Hensler, M.E.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Cogen, A.L.; et al. Statins enhance formation of phagocyte extracellular traps. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartneck, M.; Keul, H.A.; Zwadlo-Klarwasser, G.; Groll, J. Phagocytosis independent extracellular nanoparticle clearance by human immune cells. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulik, N.A.; Hellenbrand, K.M.; Czuprynsk, C.J. Mannheimia haemolytica and Its Leukotoxin Cause Macrophage Extracellular Trap Formation by Bovine Macrophages. Infection and Immunity 2012, 80, 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, X.; Liao, C.; Liu, X.; Du, J.; et al. Escherichia coli and Candida albicans Induced Macrophage Extracellular Trap-Like Structures with Limited Microbicidal Activity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Zou, X.-B.; Chai, Y.-F.; Yao, Y-M. Macrophage Polarization in Inflammatory Diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 10, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boe, D.M.; Curtis, B.J.; Chen, M.M.; et al. Extracellular traps and macrophages: new roles for the versatile phagocyte. J Leukoc Biol. 2015, 97, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doster, R.; Rogers, L.; Aronoff, D.; et al. Macrophages Produce Extracellular Traps in Response to Streptococcus agalactiae Infection. OFID 2015, 2 (Suppl 1), S235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Je, S.; Quan, H.; Yoon, Y.; et al. Mycobacterium massiliense Induces Macrophage Extracellular Traps with Facilitating Bacterial Growth. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldmann, O.; Medina, E. The expanding world of extracellular traps: not only neutrophils but much more. Frontiers in Immunology 2013, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Espinosa, O.; Rojas-Espinosa, O.; Moreno-Altamirano, M.M.; et al. Metabolic requirements for neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Immunology 2015, 145, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Does, A.M.; Beekhuizen, H.; Ravensbergen, B. LL 37 directs macrophage differentiation toward macrophages with a proinflammatory signature. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães-Costa, A.B.; Rochael, N.C.; Oliveira, F.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular Traps reprogram IL-4/GM-CSF-induced Monocyte Differentiation to anti-inflammatory Macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology 2017, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, A.S.; O’Brien, X.M.; Johnson, C.M.; et al. An extracellular matrix-based mechanism of rapid neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to C. albicans. J Immunol. 2013, 190, 4136–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.-Y.; Wang, N.; Li, S.; et al. The Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophage Polarization: Reflecting Its Dual Role in Progression and Treatment of Human Diseases. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016, 2016, 2795090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil,S. ; Huh, J.; Baronas, V.; et al. Oral administration of the nitroxide radical TEMPOL exhibits immunomodulatory and therapeutic properties in multiple sclerosis models. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2017, 62, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillack, K.; Breiden, P.; Martin, R.; et al. T Lymphocyte Priming by Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Links Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. The Journal of Immunology 2012, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csillag, A.; Boldogh, I.; Pazmandi, K.; et al. , Pollen-Induced Oxidative Stress Influences Both Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses via Altering Dendritic Cell Functions. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 2377–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mège, J.-L.; Mehraj, V.; Capo, C. Macrophage polarization and bacterial infections. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2011, 24, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgachev, V.A.; Yu, B.; Sun, L.; et al. IL-10 Overexpression Alters Survival in the Setting of Gram Negative Pneumonia Following Lung Contusion. Shock 2014, 41, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, L.; Munoz-Planillo, R.; Nunez, G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat Immunol. 2012, 13, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Katz, B.P.; Spinola, S.M. Haemophilus ducreyi-Induced Interleukin-10 Promotes a Mixed M1 and M2 Activation Program in Human Macrophages. Infection and Immunity 2012, 80, 4426–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogston, A. Report upon Micro-Organisms in Surgical Diseases. Br Med J. 1881, 1, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, F.; Philpott, D.J. Recognition of Staphylococcus aureus by the innate immune system. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2005, 18, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.F.; Leech, J.M.; Rogers, T.R.; McLoughlin, R.M. Staphylococcus aureus colonization: modulation of host immune response and impact on human vaccine design. Frontiers in Immunology 2014, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.J.; Cerdeira, C.D.; Chavasco, J.M.; et al. In vitro screening antibacterial activity of Bidens pilosa Linné and Annona crassiflora Mart. against oxacillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ORSA) from the aerial environment at the dental clinic. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2014, 56, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Ma, H.-D.; Yin, X-Y.; et al. ; et al. Forkhead Box O1 Regulates Macrophage Polarization Following Staphylococcus aureus Infection: Experimental Murine Data and Review of the Literature. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2016, 51, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Akt1-mediated regulation of macrophage polarization in a murine model of Staphylococcus aureus pulmonary infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 208, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasraie, S.; Niebuhr, M.; Kopfnagel, V.; et al. , Macrophages from patients with atopic dermatitis show a reduced CXCL10 expression in response to staphylococcal a-toxin. Allergy 2012, 67, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakara, R.; Harro, J.M.; Leid, J.G.; et al. Suppression of the Inflammatory Immune Response Prevents the Development of Chronic Biofilm Infection Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infection and Immunity 2011, 79, 5010–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannagan, R.S.; Heit, B.; Heinrichs, D.E. Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Macrophages and the Immune Evasion Strategies of Staphylococcus aureus. Pathogens 2015, 4, 826–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlow, L.R.; Hanke, M.L.; Fritz, T.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms prevent macrophage phagocytosis and attenuate inflammation in vivo. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 6585–6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysko, O.; Holtappels, G.; Zhang, N.; et al. Alternatively activated macrophages and impaired phagocytosis of S. aureus in chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy 2011, 66, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanke, M.L.; Angle, A.; Kielian, T. MyD88-Dependent Signaling Influences Fibrosis and Alternative Macrophage Activation during Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Infection. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, L.M.; Swanson, J.A. The role of the activated macrophage in clearing Listeria monocytogenes infection. Front. Biosci 2007, 12, 2683–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnues, B.; Raoult, D.J.; Mege, L. IL-16 is critical for Tropheryma whipplei replication in Whipple’s disease. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 4575–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnues, B.; Lepidi, H.; Raoult, D.J.; Mege, L. Whipple disease: intestinal infiltrating cells exhibit a transcriptional pattern of M2/alternatively activated macrophages. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, 1642–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, A.; Erreni, M.; Allavena, P.; et al. Macrophage polarization in pathology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 4111–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielen, K.; ‘S Jongers, B.; Boddaert, J.; et al. Biofilm-Induced Type 2 Innate Immunity in a Cystic Fibrosis Model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazlett, L.D.; McClellan, S.A.; Barrett, R.P.; et al. IL-33 shifts macrophage polarization, promoting resistance against Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicetti Miguel, R.D.; Harvey, S.A.K.; LaFramboise, W.A.; et al. Human Female Genital Tract Infection by the Obligate Intracellular Bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis Elicits Robust Type 2 Immunity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenberg, M.E.; Gigliotti-Rothfuchs, A.; Wigzell, H. The role of IFN-γ in the outcome of chlamydial infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2002, 14, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupelli, M.; Shimada, K.; Chiba, N.; et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae Infection in Mice Induces Chronic Lung Inflammation, iBALT Formation, and Fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesta, M.C.; Zippoli, M.; Marsiglia, C.; Gavioli, E.M.; Cremonesi, G.; Khan, A.; Mantelli, F.; Allegretti, M.; Balk, R. Neutrophil activation and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in COVID-19 ARDS and immunothrombosis. Eur J Immunol. 2023, 53, e2250010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.N.; Winter, M.G.; Spees, A.M.; et al. PPARγ-mediated increase in glucose availability sustains chronic Brucella abortus infection in alternatively activated macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Lin, Y.-W.; Burton, F.H.; Wei, L.-N. M1-M2 balancing act in white adipose tissue browning – a new role for RIP140. Adipocyte 2015, 4, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.-H.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.-M.; et al. , Macrophage cell death upon intracellular bacterial infection. Macrophage (Houst) 2015, 26, e779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciello, I.; Silipo, A.; Lembo-Fazio, L.; et al. Intracellular Shigella remodels its LPS to dampen the innate immune recognition and evade inflammasome activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E4345–E4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehraj, V.; Textoris, J.; Amara, A.B.; et al. Monocyte Responses in the Context of Q Fever: From a Static Polarized Model to a Kinetic Model of Activation. JID 2013, 208, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mares, C.A.; Sharma, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Defect in efferocytosis leads to alternative activation of macrophages in Francisella infections. Immunology and Cell Biology 2011, 89, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobert, A.P.; Verriere, T.; Assim, M.; et al. Heme Oxygenase-1 Dysregulates Macrophage Polarization and the Immune Response to Helicobacter pylori. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3013–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, J.; Sharma, P.K.; Mukhopadhaya, A. Vibrio cholerae porin OmpU mediates M1-polarization of macrophages/monocytes via TLR1/TLR2 activation. Immunobiology 2015, 220, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Xia, J.; Li, T.; et al. Shp2 Deficiency Impairs the Inflammatory Response Against Haemophilus influenzae by Regulating Macrophage Polarization. JID 2016, 214, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasky, E.C.; Olson, R.M.; Brown, C.R. Macrophage Polarization during Murine Lyme Borreliosis. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 2627–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radolf, J.D.; Arndt, L.L.; Akins, D.R.; et al. Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and synthetic lipopeptides activate monocytes/macrophages. J. Immunol. 1995, 154, 2866–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, K.P.; Vavrin, Z.; Eichwald, E.; et al. Nitric oxide production during murine Lyme disease: lack of involvement in host resistance or pathology. Infect. Immun. 1995, 63, 3886–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.P.; Zachary, J.F.; Teuscher, C.; et al. Dual role of interleukin-10 in murine Lyme disease: regulation of arthritis severity and host defense. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 5142–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wooten, R.M. Borrelia burgdorferi elicited-IL-10 suppresses the production of inflammatory mediators, phagocytosis, and expression of co-stimulatory receptors by murine macrophages and/or dendritic cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, M.C.; Lefimil, C.; Rodas, P.I.; et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae Modulates Immunity by Polarizing Human Macrophages to a M2 Profile. PLoS ONE, 2015, 10, e0130713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, G.; Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb, Y.B.; Huang, N.; et al. Immunologic environment influences macrophage response to Porphyromonas gingivalis. Molecular Oral Microbiology, 2017, 32, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahnert, A.; Seiler, P.; Stein, M.; et al. Alternative activation deprives macrophages of a coordinated defense program to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 36, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Dados sobre a Turbeculose no Brasil. 2023.

- Forrellad, M.A.; Klepp, L.I.; Gioffré, A.; et al. Virulence factors of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Virulence 2013, 4, 3–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, E.T.; Shukla, S.; Sweet, D.R.; et al. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages drives antiinflammatory responses and inhibits Th1 polarization of responding T cells. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 2242–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Guler, R.; Parihar, S.P.; et al. Batf2/Irf1 Induces Inflammatory Responses in Classically Activated Macrophages, Lipopolysaccharides, and Mycobacterial Infection. The Journal of Immunology 2015, 194, 6035–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, T.; Ehlers, S.; Heitmann, L.; et al. Autocrine IL-10 induces hallmarks of alternative activation in macrophages and suppresses antituberculosis effector mechanisms without compromising T cell immunity. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaram, M.V.; Brooks, M.N.; Morris, J.D.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis activates human macrophage peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma linking mannose receptor recognition to regulation of immune responses. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aira, N.; Andersson, A.-M.; Singh, S.K.; et al. Species dependent impact of helminth-derived antigens on human macrophages infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Direct effect on the innate antimycobacterial response. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallows, D.; Peixoto, B.; Kaplan, G.; et al. Mycobacterium leprae alters classical activation of human monocytes in vitro. Journal of Inflammation 2016, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.J.; Barbosa, M.G.M.; Andrade, P.R.; et al. Autophagy Is an Innate Mechanism Associated with Leprosy Polarization. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006103. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.P.; Bittencourt, T.L.; de Oliveira, A.L.; et al. Macrophage Polarization in Leprosy–HIV Co-infected Patients. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.-F.; Hong, Y.-X.; Feng, G-J.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced M2 to M1 Macrophage Transformation for IL-12p70 Production Is Blocked by Candida albicans Mediated Up-Regulation of EBI3 Expression. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Moyes, D.L. Adaptive immune responses to Candida albicans infection. Virulence 2015, 6, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerdeira, C.D.; da Silva, J.J.; Netto, M.F.R.; et al. Talinum paniculatum: a plant with antifungal potential mitigates fluconazole-induced oxidative damage-mediated growth inhibition of Candida albicans. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Quím. Farm. 2020, 49, 401–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdeira, C.D.; Brigagão, M.R.P.L.; Carli, M.L.; et al. Low-level laser therapy stimulates the oxidative burst in human neutrophils and increases their fungicidal capacity. J. Biophotonics 2016, 9, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, L.; Authier, H.; Stein, S.; et al. LRH-1 mediates anti-inflammatory and antifungal phenotype of IL-13-activated macrophages through the PPARγ ligand synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reales-Calderón, J.A.; Aguilera-Montilla, N.; Corbí, A.L.; et al. Proteomic characterization of human proinflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages and their response to Candida albicans. Proteomics 2014, 14, 1503–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandakumar, V.; Hebrink, D.; Jenson, P.; et al. Differential Macrophage Polarization from Pneumocystis in Immunocompetent and Immunosuppressed Hosts: Potential Adjunctive Therapy during Pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2017, 85, e00939–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. , Wang, F.; Bhan, U.; et al. TLR9 Signaling Is Required for Generation of the Adaptive Immune Protection in Cryptococcus neoformans-Infected Lungs. The American Journal of Pathology 2010, 177, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, A.J.; He, X.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Cryptococcal HSP70 homologue Ssa1 contributes to pulmonar expansion of C. neoformans during the afferent phase of the immune response by promoting macrophage M2 polarization. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 5999–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, D. Chronic granulomatous disease. Br Med Bull 2016, 118, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, M.S.; Oliveira, A.F.; da Silva, T.A.; et al. Paracoccin Induces M1 Polarization of Macrophages via Interaction with TLR4. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, T.A.; Roque-Barreira, M.C.; Casadevall, A.; Almeida, F. Extracellular vesicles from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis induced M1 polarization in vitro. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 35867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, J.M.; Scott, A.L. Antecedent Nippostrongylus infection alters the lung immune response to Plasmodium berghei. Parasite Immunol. 2017, 39, e12441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirelli, P.M.; Angeloni, M.B.; Barbosa, B.F.; et al. Trophoblast-macrophage crosstalk on human extravillous under Toxoplasma gondii infection. Placenta 2015, 36, 1106e1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chao, J.; et al. Polarization of macrophages induced by Toxoplasma gondii and its impact on abnormal pregnancy in rats. Acta Trop. 2015, 143, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponce, N.E.; Sanmarco, L.M.; Eberhardt, N.; et al. CD73 Inhibition Shifts Cardiac Macrophage Polarization toward a Microbicidal Phenotype and Ameliorates the Outcome of Experimental Chagas Cardiomyopathy. The Journal of Immunology, 2016, 197, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, C.F.; Cerdeira, C.D. Eventos tromboembólicos associados à cardiopatia chagásica: revisão de literature. Revista da Universidade Vale do Rio Verde, Três Corações 2015, 13, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalén, M.E.; Cabral, M.F.; Sanmarco, L.M.; et al. Chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection potentiates adipose tissue macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and contributes to diabetes progression in a diet induced obesity model. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 13400–13415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCartney Francis, N.; Jin, W.; Belkaid, Y.; et al. Aberrant host defense against Leishmania major in the absence of SLPI. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014, 96, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Saldarriaga, O.A.; Spratt, H.; et al. Transcriptional Profiling in Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis Reveals a Broad Splenic Inflammatory Environment that Conditions Macrophages toward a Disease-Promoting Phenotype. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, R.; Jordan, M.B.; Divanovic, S.; et al. IFN-γ–Driven IDO Production from Macrophages Protects IL-4R–Deficient Mice against Lethality during Schistosoma mansoni Infection. The American Journal of Pathology 2012, 180, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; et al. Schistosoma japonicum infection induces macrophage polarization. The Journal of Biomedical Research 2014, 28, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, L.F.C.; Cerdeira, C.D.; Gagliano, G.S.; et al. Alternate-day fasting, a high-sucrose/caloric diet and praziquantel treatment influence biochemical and behavioral parameters during Schistosoma mansoni infection in male BALB/c mice. Experimental Parasitology 2022, 240, 108316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; et al. Inhibition of Notch Signaling Attenuates Schistosomiasis Hepatic Fibrosis via Blocking Macrophage M2 Polarization. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11, e0166808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peon, A.N.; Espinoza-Jimenez, A.; Terrazas, L.I. Immunoregulation by Taenia crassiceps and its antigens. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 498583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawistowska-Deniziak, A.; Basałaj, K.; Strojny, B.; et al. New Data on human Macrophages Polarization by Hymenolepis diminuta Tapeworm—an In Vitro study. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundup, S.; Srivastava, L.; Harn, D.A., Jr. Polarization of host immune responses by helminth-expressed glycans. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1253, E1–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawill, S.; Le Goff, L.; Ali, F. Both free-living and parasitic nematodes induce a characteristic Th2 response that is dependent on the presence of intact glycans. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, C.F.; Cerdeira, C.D.; Prado, A.C.; Dias, R.P.C.S.; Silva, R.B.V.; Vertêlo, P.C.; Silvério, A.C.P. ; Profile of people living with HIV at a reference center in contagious and infectious diseases in Belo Horizonte (MG, Brazil). Revista de Medicina e Saúde de Brasília 2020, 9, 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Boletim Epidemiológico AIDS e DST. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, PN de DST e AIDS, 2017, 48.

- Sang, Y.; Miller, L.C.; Blecha, F. Macrophage Polarization in Virus-Host Interactions. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão-Lima, L.J.; Espíndola, M.S.; Soares, L.S.; et al. Classical and alternative macrophages have impaired function during acute and chronic HIV-1 infection. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 21, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassol, E.; Cassetta, L.; Rizzi, C.; Alfano, M.; Poli, G. M1 and M2a polarization of human monocyte-derived macrophages inhibits HIV-1 replication by distinct mechanisms. J Immunol. 2009, 182, 6237–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertêlo, P.C.; Miranda, A.B.; Labanca, L.; Borges-Starling, A.L.; Cerdeira, C.D.; et al. Prevalence of VIH-1/HTLV-1 co-infection and behavioral risk among people living with HIV in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Revista de Salud Pública 2022, 28, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pedral-Sampaio, D.B.; Martins Netto, E.; Pedrosa, C.; et al. Co-Infection of tuberculosis and HIV/HTLV retroviruses: frequency and prognosis among patients admitted in a Brazilian hospital. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 1, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Porto, A.F.; Neva, F.A.; Bittencourt, H. HTLV-1 decreases Th2 type of immune response in patients with strongyloidiasis. Parasite Immunol 2001, 23, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, J.; Galvão-Castro, B.; Rodrigues, L.C.; et al. Increased risk of tuberculosis with human T lymphotropic virus I infection: A case-control study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2005, 40, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porto, A.F.; Santos, S.B.; Alcantara, L.; et al. HTLV-1 modifies the clinical and immunological response to schistosomiasis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004, 137, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M.L.; Santos, S.B.; Souza, A.; et al. Influence of HTLV-1 on the clinical, microbiologic and immunologic presentation of tuberculosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, N.; et al. HCV core protein inhibits polarization and activity of both M1 and M2 macrophages through the TLR2 signaling pathway. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Pu, J.; et al. Comparative virus replication and host innate responses in human cells infected with three prevalent clades (2.3.4, 2.3.2, and 7) of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 viruses. J Virol. 2014, 88, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.H.; Toapanta, F.R.; Shirey, K.A.; et al. Potential role for alternatively activated macrophages in the secondary bacterial infection during recovery from influenza. Immunol Lett. 2012, 141, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.; Morris, P.; Dickman, M.J.; et al. The therapeutic potential of epigenetic manipulation during infectious diseases. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2016, 167, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Q.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Differential effects of macrophages subtypes on SARS-CoV-2 infection in a human pluripotent stem cell-derived model. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Amorim, A.F.; Jesus Coimbra, M.; Podestá, M.H.M.C.; da Silva, A.O.; Cerdeira, C.D.; et al. Critical Factors Associated with Morbimortality in COVID-19 Patients Attended at a Brazilian Public Hospital: a Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Health Sciences 2023, 25, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, P. Tempol treatment of COVID-19. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020, 159, S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodin, P.; Davis, M.M. Human immune system variation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017, 17, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaume, M.; Yip, M.S.; Cheung, C.Y.; et al. Anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike antibodies trigger infection of human immune cells via a pH- and cysteine protease-independent FcγR pathway. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 10582–10597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, M.S.; Leung, N.H.; Cheung, C.Y.; et al. Antibody-dependent infection of human macrophages by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, J.; Van Rooijen, N.; et al. Evasion by stealth: inefficient immune activation underlies poor T cell response and severe disease in SARS-CoV-infected mice. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Dong, C.; Xiong, S. IL-33 enhances macrophage M2 polarization and protects mice from CVB3-induced viral myocarditis. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2017, 103, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.; Bivins-Smith, E.R.; Smith, M.S. NF-κB and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Activity Mediates the HCMV-Induced Atypical M1/M2 Polarization of Monocytes. Virus Res. 2009, 144, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-S.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Chen, Y-C.; et al. M2 macrophage subset decrement is an indicator of bleeding tendency in pediatric dengue disease. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2018, 51, 829e838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, N.A.; Ruby, T.; Jacobson, A.; et al. Salmonella require the fatty acid regulator PPAR for the establishment of a metabolic environment essential for long-term persistence. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.E.; Roque, N.R.; Magalhães, K.G.; et al. Differential TLR2 downstream signaling regulates lipid metabolism and cytokine production triggered by Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1841, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.S.; Boelaert, J.R.; Appelberg, R. Role of iron in experimental Mycobacterium avium infection. J Clin Virol. 2001, 20, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, J.B.; Volkheimer, A.D.; Rubach, M.P. Monocyte polarization in children with falciparum malaria: relationship to nitric oxide insufficiency and disease severity. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 29151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stijlemans, B.; Guilliams, M.; Raes, G.; et al. African trypanosomosis: From immune escape and immunopathology to immune intervention. Veterinary Parasitology 2007, 148, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stempin, C.C.; Motrán, C.C.; Aoki, M.P.; et al. PD-L2 negatively regulates Th1-mediated immunopathology during Fasciola hepatica infection. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 77721–77731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerngross, L.; Lehmicke, G.; Belkadi, A.; et al. Role for cFMS in maintaining alternative macrophage polarization in SIV infection: implications for HIV neuropathogenesis. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.W.; Engle, E.L.; Shirk, E.N.; et al. Splenic Damage during SIV Infection Role of T-Cell Depletion and Macrophage Polarization and Infection. The American Journal of Pathology 2016, 186, 2068–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, K.J.; Maury, W. The role of mononuclear phagocytes in Ebola virus infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2018, 104, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

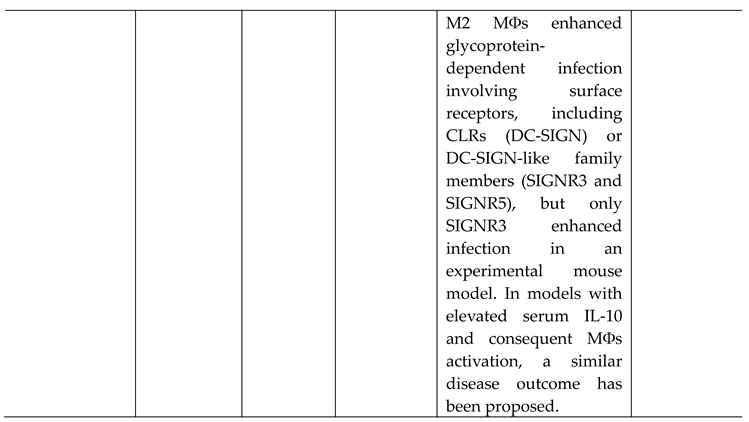

- Rogers, K.J.; Brunton, B.; Mallinger, L.; Bohan, D.; Sevcik, K.M.; Chen, J.; et al. IL-4/IL-13 polarization of macrophages enhances Ebola virus glycoprotein-dependent infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13, e0007819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stantchev, T.S.; Zack-Taylor, A.; Mattson, N.; et al. Cytokine Effects on the Entry of Filovirus Envelope Pseudotyped Virus-Like Particles into Primary Human Macrophages. Viruses 2019, 11, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, N.; Giang, P.H.; Gupta, C.; Basu, C.K.; Siddiqui, I.; Salunke, D.M.; Sharma, P. Mycobacterium tuberculosis secretory proteins CFP-10, ESAT-6 and the CFP10:ESAT6 complex inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kB transactivation by downregulation of reactive oxidative species (ROS) production. Immunology and Cell Biology 2008, 86, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Manjunatha, U.; Boshoff, H.I.; Há, Y.H.; Niyomrattanakit, P.; Ledwidge, R.; Dowd, C.S.; Lee, I.Y.; Kim, P.; Zhang, L.; Kang, S.; Keller, T.H.; Jiricek, J.; Barry, C. E 3rd. PA-824 Kills Nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Intracellular NO Release. Science 2008, 322, 1392–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénard, A.; Sakwa, I.; Schierloh, P.; et al. B Cells Producing Type I Interferon Modulate Macrophage Polarization in Tuberculosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.J.; Tsang, T.M.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization dynamically adapts to changes in cytokine microenvironments in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. mBio 2013, 4, e00264–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, C.; Yang, X.-F.; Wang, H. Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomarker Research 2014, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalish, S.V.; Lyamina, S.V.; Usanova, E.A.; et al. Macrophages Reprogrammed In Vitro Towards the M1 Phenotype and Activated with LPS Extend Lifespan of Mice with Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2015, 21, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahrendorf, M.; Swirski, F.K. Abandoning M1/M2 for a Network Model of Macrophage Function. Circ Res. 2016, 119, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyamina, S.V.; Kruglov, S.V.; Vedenikin, T.Y.; et al. Alternative reprogramming of M1/M2 phenotype of mouse peritoneal macrophages in vitro with interferon γ and interleukin 4. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2012, 152, 548–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundu, S.; Palma, L.; Picceri, G.G.; et al. Glutathione Depletion Is Linked with Th2 Polarization in Mice with a Retrovirus-Induced Immunodeficiency Syndrome, Murine AIDS: Role of Proglutathione Molecules as Immunotherapeutics. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 7118–7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Dou, H.; Gong, W.; et al. Bis N norgliovictin, a small molecule compound from marine fungus, inhibits LPS induced inflammation in macrophages and improves survival in sepsis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 705, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos, B.T.L.; Buchaim, D.V.; Pomini, K.T.; et al. Photobiomodulation therapy as a possible new approach in COVID-19: a systematic review. Life (Basel) 2021, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).