1. Introduction

Knowledge of normal spinal morphology and the incidence of vertebral anomalies is important for distinction of pathologic change from functional anatomic variations [

1]. Vertebral congenital anomalies were defined as any defect in vertebral body formation [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Among these, transitional vertebra is one of the most common anatomical abnormality of the spine. Transitional vertebra is considered a congenital anomaly, which occurs in various species of animals and in humans [

2,

6] and its presence can be clinically significant [

7]. It’s supposed to exist a hereditary predisposition to transitional vertebra [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Transitional vertebrae can appear in any junction of the spine presenting common characteristics of both adjacent vertebral segments. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra (LTV) is considered to be the result of an incomplete homeotic transformation of a lumbar vertebra into a sacral vertebra (sacralisation) or a sacral vertebra into a lumbar vertebra (lumbarisation) [

12]. The prevalence of sacralisation is higher than lumbarisation [

13,

14]. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra is described as a congenital anomaly which could have some effect on spinal biomechanics and consequently could affect degenerative processes in adjacent vertebra in mammals [

12]. Its presence is identified having a higher prevalence in domesticated species compared to wild counterparts, as well as slower-moving species compared to fast and agile mammals [

5].

The morphology of transitional vertebrae is variable, presenting modifications of one or both vertebral arch and body and can have right-to-left asymmetry or lateral cranial-to-caudal gradation in vertebral morphology [

1,

15,

16].

In domestic mammals, the researches on transitional vertebrae are focused especially on dogs and less, in cats, in which, the congenital abnormalities of the spine are frequently identified radiographically [

17]. The largest description of transitional vertebrae regarding the localization, the morphology, clinical significance and prevalence exist in dogs [

8,

18,

19]. Such anomalies, as well as others (hemivertebrae, wedge vertebrae, block vertebrae, atlantoaxial malformations and spina bifida) and their prevalence have been described also in cats, ferrets [

20,

21,

22,

23]. In other domestic mammals the reports regarding the presence and type of transitional vertebrae are even less, for that we proposed to investigate the lumbosacrocaudal spine in as many species as possible, to have a comparative view, not only radiologically, but especially anatomical analysis. We consider it’s the first study in which are included all domestic species for this investigation. Anyway, we intended to highlight the particular morphology of transitional vertebrae in all the species by anatomical examination, not only radiologically as in the most existing researches on this subject.

2. Materials and Methods

The researches of this study were performed on a period of 14 years, between 2009-2023. The studies based on morphologic description realized directly on the bones and skeletons in the anatomy labs of Faculty of Veterinary Medicine from Iasi, Romania, and completed by radiologic exam. In case of some species – ruminants, horses, pigs, rabbits and cats, the specimens represented old or sick animals with various pathologies (metabolic, locomotor and others), but free of risk for humans, which died previously and the owners agreed to donate them for didactic process. After the valorisation of the animals for dissection, their bones were harvested to prepare the skeleton. In this way, along of the years, the bones collected were boiled and cleaned of debris mechanically and then chemically in a hydrogen peroxide solution 3%, a variable interval to obtain clean pieces. After that, the spine of animals was analysed anatomically, respectively the vertebrae were counted and studied their normal or modified characteristics and described in accordance with

Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria [

24].

There were valorised 29 specimens of cows, 32 specimens of sheep, 31 specimens of horses, 26 specimens of pigs and 33 specimens of rabbits (

Table 1). In case of carnivores, for our purpose, it was chosen the x-ray exam as the method, being more facile. The animals were the patients of a veterinary clinic subjected to the x-ray exam of the spine. Totally, the studies involved 89 dogs and 48 cats, from different breeds, both males and females (

Table 1).

The animals were brought to the clinic for various pathologies, presenting especially nervous and locomotor symptoms. The patients were clinically examined and then the x-ray exam of the spine was performed using latero-lateral and ventro-dorsal incidences. The radiographs obtained were analysed to diagnose the pathology, but also for the anatomical conformation of the spine, the number of the vertebra being also counted. Other 9 cats of common breed were examined post-mortem, as in the case of other species.

4. Discussion

For ruminants and pigs exist very few descriptions of transitional vertebra. Unusual transitional vertebra is mentioned between the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in sheep [

27]. The post-mortem CT and MRI scanning of 41 sheep revealed the presence of the lumbosacral transitional vertebrae considered as an anatomic variation of the last lumbar vertebra due to the enlarged transverse process which come in contact with the sacrum or ilium. In this case the fusion was considered congenital due to the lack of other lesions [

28]. In ruminants, our research revealed the lumbosacral transitional vertebrae, but only cases of lumbarisation, very evident in case of big ruminants, but not sacralisation, in contrast with previous investigations.

In pigs is mentioned the presence of the transitional vertebrae at the thoracolumbar junction. In a group of 37 pigs of Landrace and Duroc breeds, the transitional vertebra was identified in a rate of 22% - 8 pigs, four pigs having 5 lumbar vertebrae and the other four with 6 lumbar vertebrae. Transitional vertebrae only occurred at the thoracolumbar junction, represented thoracoisation of lumbar vertebrae/lumbar ribs and were counted with thoracic vertebrae. 7 transitional vertebrae were found in Landrace breed and a single one in Duroc Breed [

29]. Thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae were not associated with abnormal curvature in the examined pigs. In humans, lumbosacral transitional vertebrae have been associated with lower back pain [

30]. In addition to these observations, we identified transitional vertebrae in pigs, in both lumbosacral and sacrocaudal junction, as lumbarisation process of the first sacral vertebra and sacralisation of the first caudal vertebra. Also, in pigs we revealed the tendency of lumbarization of S1, but also the sacralization of Cd1, aspects that reflect the evident predisposition to transitional vertebra in this junctions.

In horses the data regarding the transitional vertebra are less, being difficult to realize such studies on live animals as CT scanning or tomography, other way it’s necessary to perform a post-mortem examination. The observations of Haussler et al., 1997 [

1], revealed thoracholumbar transitional vertebrae on a rate of 22% (8 animals) of examined animals (36 Thoroughed racehorses), and sacrocaudal transitional vertebra on a rate of 36% (13 animals). In 61 % of animals the number of lumbar and sacral vertebrae was normal (6 and 5 vertebrae). Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae were not found, as in case of our research in this species. Other studies reported the sacralisation of L6, characterized by ankyloses and malformation of L6 and the sacrum in two horses with clinical sings of hind limb lameness and possible sacroiliac joint injury [

31]. Regarding the sacrocaudal transitional vertebra has been suggested it appears often as a congenital development anomaly than as acquired ankyloses or pathologic changes. Also, it has been reported that an elongated sacrum is often seen in aged horses, in which the first and sometimes the second caudal vertebrae fuse with the sacrum [

1]. In our findings only the first caudal vertebra was fused with the sacrum. Similarly to the study of Haussler et al., 1997 [

1], this aspect was available in our investigations, by the presence of sacrocaudal transitional vertebrae in older specimens, in a higher rate.

In the descriptive post-mortem study of Spoormakers et al., 2021 [

32], focused on anatomical variations in three breeds, the caudal cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral regions of the vertebral column of 30 Warmblood horses, 29 Shetland ponies and 18 Konik horses were examined using computed tomography. Transitional vertebrae were most frequently encountered in Shetland ponies. Lumbarization of the last thoracic vertebra was encountered in Shetland ponies in a rate of 7%. In one case was associated with a reduction to 17 rib pairs. In the other, the anomaly resulted in 18 ribs and 7 transverse processes on the left side, and 19 ribs with 6 transverse processes on the right side. Thoracoisation of the first lumbar vertebra was seen in one Shetland pony - 3% having 19 ribs bilaterally. Sacralisation of the last lumbar vertebra was seen in one Warmblood – 3%. Sacralization of the first caudal vertebra by fusion to sacrum was encountered in 33% of Shetland ponies, 29% of Warmblood horses and 6% of Konik horses. The incomplete sacralisation of the last lumbar vertebra was reported by Scilamati et al., 2023 [

33], on a study on the last lumbar vertebrae of 40 horses, by CT scanning. In this case, the sacralisation on the last lumbar vertebra was associated with spondilolisthesis. These results, confirm again the higher rate of the sacrocaudal transitional vertebra comparing with others in this species [

32]. The development of the imaging techniques led to the possibility to investigate the variability in the conformation and the abnormalities of the spine in this species.

In rabbits few studies reported that the transitional vertebrae, which are located at the junction of different segments of the spine, are also concerned. Malformations caused by transitional vertebrae were identified especially in the thoracolumbar junction, and less in the lumbosacral junction. Thoracolumbar transitional vertebra was observed in association with awith lordoscoliosis, wedge vertebrae with kyphoscoliosis, or lordoscoliosis with a twisted pelvis [

34]. These aspects have been confirmed by Proks et al., 2018 [

5], in their study, in which the thoracolumbar junction was the most common location of transitional vertebral anomalies, the lumbosacral junction being the second one. Proks et al., 2018 [

5], on 330 rabbits, counted the vertebral formula, but also the presence of vertebral anomalies. There have been identified seven vertebral formulas with normal vertebral morphology in 84.8% of animals. The most common abnormalities were the transitional vertebrae found in 41 animals, in the thoracolumbar segment – 35 rabbits and lumbosacral one – 6 rabbits. In two rabbits the presence of thoracolumbar and lumbosacral transitional vertebrae has been associated to thoracic lordoscoliosis. No difference between sexes in the prevalence of anomalies was observed. Previous investigators have suggested that a vertebral formula with eight lumbar vertebrae could increase susceptibility to lumbar vertebral fractures in rabbits [

35]; however, we observed this variant in only one rabbit. Few rabbits had a rudimentary intervertebral space between S3 and S4, similar to ferrets [

22]. These findings correspond also with our two cases of incomplete fusion of the last sacral vertebrae

In dog, the anatomical variations and morphologic abnormalities along of the spine, including transitional vertebrae, have been investigated more than in other species, due to the possibility to use imagistic methods and techniques and being well known the predisposition of this species to these modifications. In dogs, the presence of a supernumerary vertebra (L8) is often reported and usually has no clinical importance [

36]. Our observations showed that, in general the 8LV is shorter, as the last lumbar vertebra when the lumbar region counts 7 vertebrae. The most of the problems were reported when the supernumerary vertebra (L8) is associated with lumbosacral transitional vertebra (LTV). These variations are affected by gender, developmental factors and race, being observed that the males are affected more than the females [

13]. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra (LTV) is a common congenital anomaly seen in several dog breeds: Pug, Jack Russell Terrier, French Bulldog, etc [

37,

38]. By correlation, our relatively low percentage of transitional vertebrae in dogs can be related to other breeds that have been included in the research and the lower number of animals investigated in this species.

Deepa and John, 2014 [

13], reported that the sacralisation is more common in occurrence than lumbarization, in a rate of 2:1. Also, in our study we can confirm these aspects, transitional vertebrae being found in three males and a single female and no lumbarisation case has been found.

Regarding the shape of transverse processes [

15,

19], our investigations revealed only asymmetrical transitional vertebrae.

The presence of LTV is associated with degenerative lumbosacral stenosis (DLSS) [

39] and can lead to premature degeneration of the lumbosacral junction and cauda equina syndrome, especially in German Shepherds [

2,

40].

In cats, little works have been published relating specifically to the incidence and types of congenital and non-congenital vertebral anomalies. In Manx cat were reported spina bifida and hemivertebrae in the caudal and sacral vertebrae [

20], but the transitional vertebra is described as the most common abnormality at all level of the feline spine, the main site for transitional abnormalities being the sacrocaudal juntion [

20,

41]. This studies concluded that there is no evidence of association with clinical signs. Also in cats, as in dogs, the sacralisation is more prevalent than lumbarisation, all our cases being of strong sacralisation. Harris et al., 2018 [

42], observed in their study that the lumbosacral transitional vertebrae were significantly more prevalent in cats with lumbosacral stenosis compared with the control feline population.

The investigations of Thanaboonnipat et al., 2021 [

43], on 1365 cats, revealed as congenital anomalies, six lumbar vertebrae – 141 animals, sacralisation – 48 animals, lumbarisation - 16 animals, hemivertebrae – 1 animals, and five lumbar vertebrae – 1 animals. Even the number of animals was higher, the percentage of lumbosacral transitional vertebra (sacralisation+lumbarisation) in this study was appropriate to that of our findings. It has been concluded, that cats with abnormal lumbosacral vertebrae are predisposed to have more problems with the large bowel [

43].

In all species investigated, we cannot establish a direct relation between the presence of transitional vertebra and other criteria, especially the breed, the most of the animals being of the common breed. Regarding the age, many cases were observed in relatively old animals, but we can affirm this at most in case of sacralisation of Cd1, where we consider to be an ossification process due to the age and not a congenital malformation. Further investigations can lead to more precise data. Also, for the gender it’s difficult to affirm the predisposition of males or females to transitional vertebra, in the most of the species being included a higher number of males, but the transitional vertebra was found both in males and females, except the dog, in which transitional vertebra occurred predominantly in males

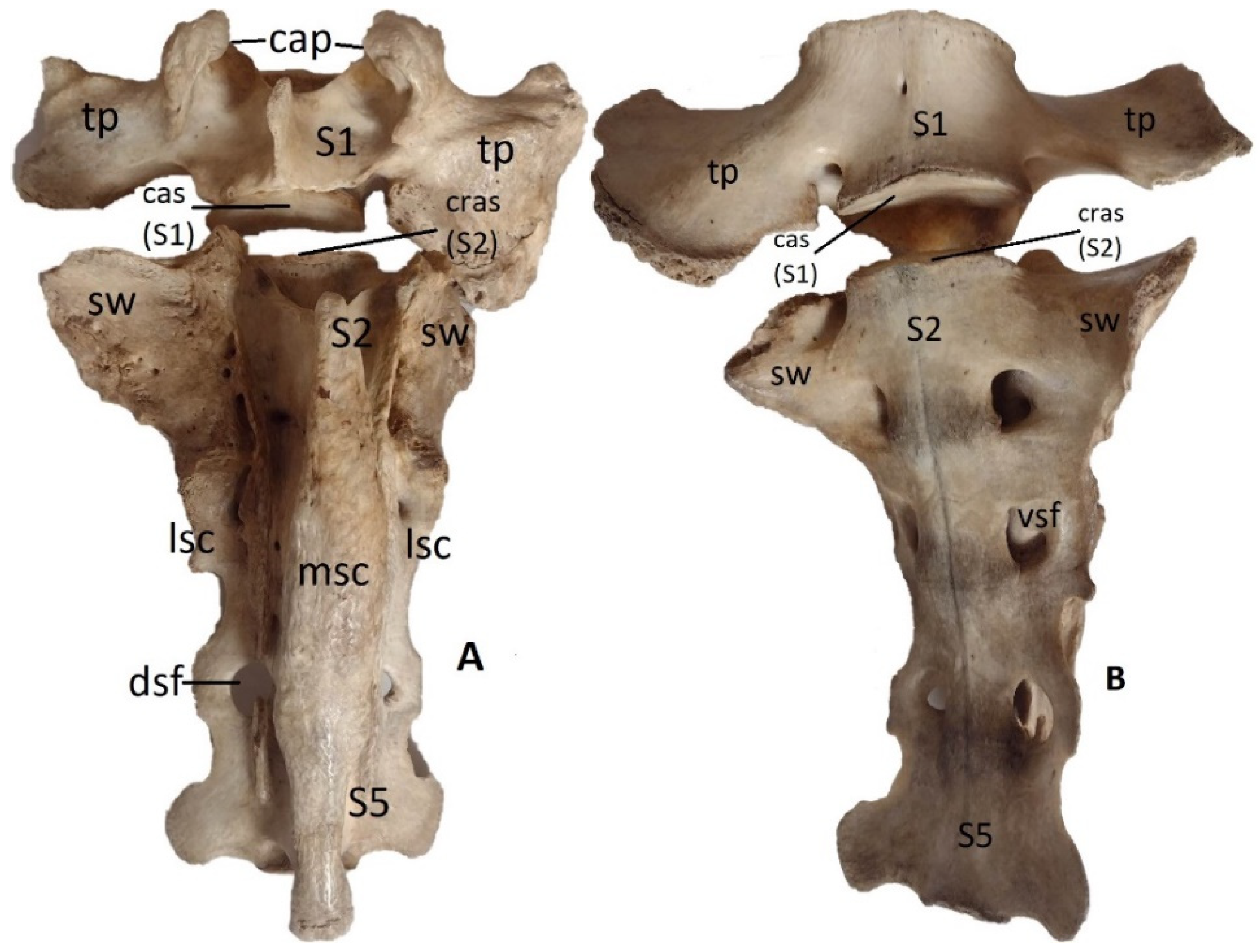

Figure 1.

Cow, female, 9 years – the lumbarization of the first sacral vertebra (S1 – promontorium). A – dorsal view, B – ventral view; tp – transverse processes of S1; cap – cranial articular processes; S2 – the second sacral vertebra; cas – caudal articular surface of S1; cras – cranial articular surface of S2; sw – sacral wing; lsc – lateral sacral crest; msc – median sacral crest; dsf – dorsal sacral foramen; vsf – ventral sacral foramen; S5 – the fifth (last) sacral vertebra.

Figure 1.

Cow, female, 9 years – the lumbarization of the first sacral vertebra (S1 – promontorium). A – dorsal view, B – ventral view; tp – transverse processes of S1; cap – cranial articular processes; S2 – the second sacral vertebra; cas – caudal articular surface of S1; cras – cranial articular surface of S2; sw – sacral wing; lsc – lateral sacral crest; msc – median sacral crest; dsf – dorsal sacral foramen; vsf – ventral sacral foramen; S5 – the fifth (last) sacral vertebra.

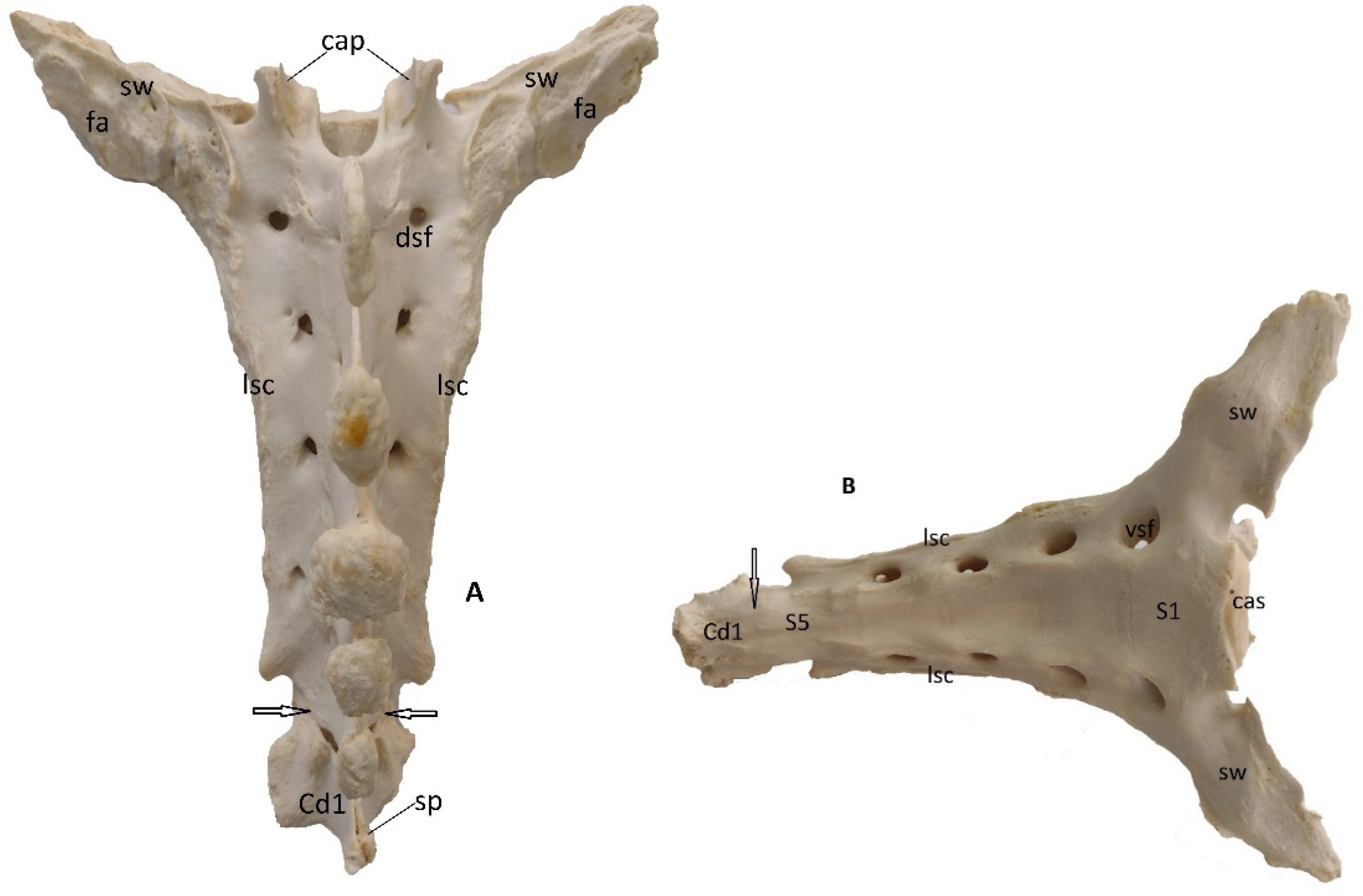

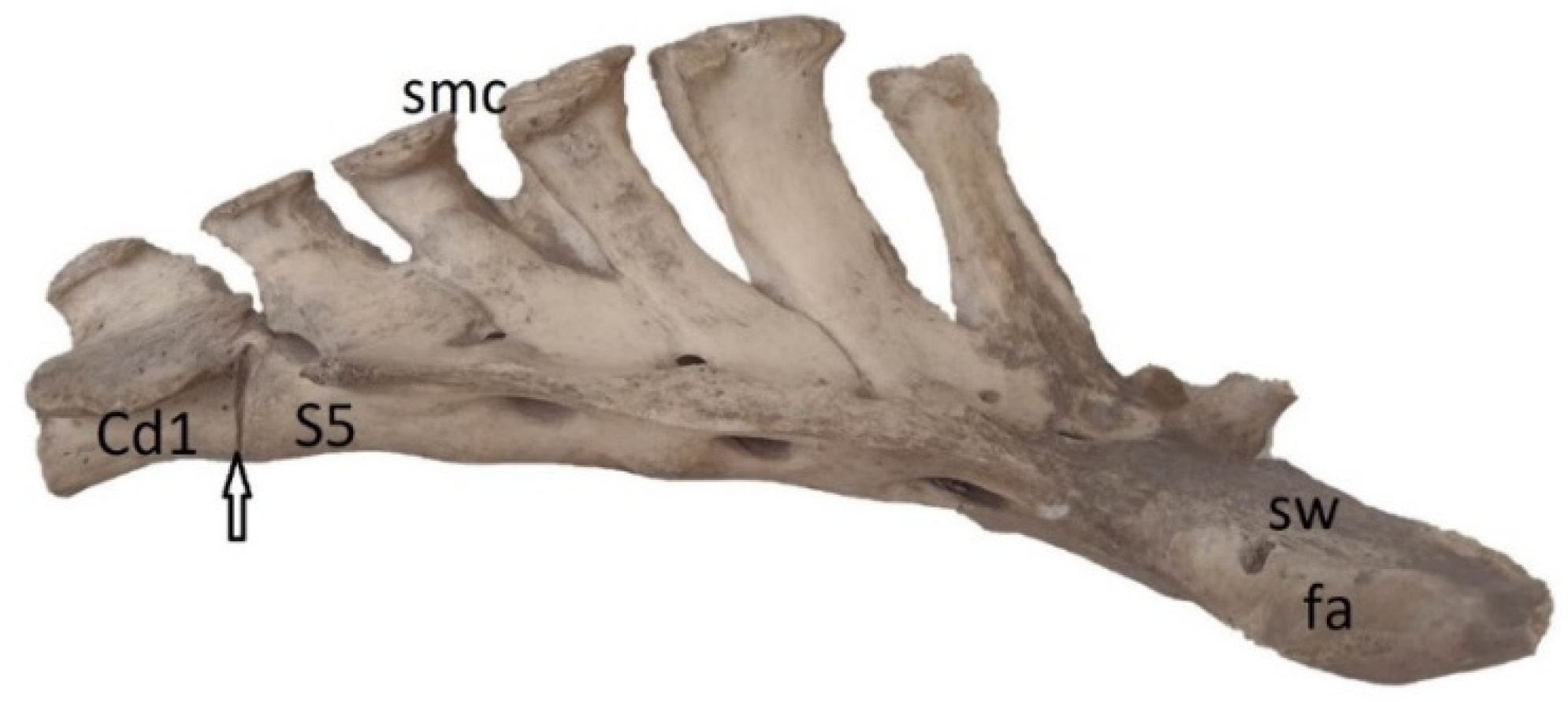

Figure 5.

Horse, male, 15 years, common breed – the fusion of the first caudal (Cd1) vertebra and the last sacral vertebra (S5). A – dorsal view: ossification process between the arches of Cd1 and S5 and the reduction of the interarcuate space between these vertebrae (arrows); sw – sacral wing, fa – facies auricularis (NAV), cap – cranial articular processes, dsf – dorsal sacral foramen, lsc – lateral sacral crest, sp – spinous process of Cd1. B – ventral view: complete fusion of the vertebral bodies of the first caudal vertebra (Cd1) and the last sacral vertebra (S5) – total ossification of the intervertebral disc (arrow); S1 – first sacral vertebra, sw – sacral wing, cas – cranial articular surface, vsf – ventral sacral foramen, lsc – lateral sacral crest.

Figure 5.

Horse, male, 15 years, common breed – the fusion of the first caudal (Cd1) vertebra and the last sacral vertebra (S5). A – dorsal view: ossification process between the arches of Cd1 and S5 and the reduction of the interarcuate space between these vertebrae (arrows); sw – sacral wing, fa – facies auricularis (NAV), cap – cranial articular processes, dsf – dorsal sacral foramen, lsc – lateral sacral crest, sp – spinous process of Cd1. B – ventral view: complete fusion of the vertebral bodies of the first caudal vertebra (Cd1) and the last sacral vertebra (S5) – total ossification of the intervertebral disc (arrow); S1 – first sacral vertebra, sw – sacral wing, cas – cranial articular surface, vsf – ventral sacral foramen, lsc – lateral sacral crest.

Figure 6.

Horse, male, 12 years – the fusion of the first caudal (Cd1) vertebra with the last sacral vertebra (S5), lateral view; the intervertebral disc is ossified but well visible; no contact between the vertebral arches of Cd1 and S5; sw – sacral wing, fa – facies auricularis; smc – sacral median crest (spinous processes).

Figure 6.

Horse, male, 12 years – the fusion of the first caudal (Cd1) vertebra with the last sacral vertebra (S5), lateral view; the intervertebral disc is ossified but well visible; no contact between the vertebral arches of Cd1 and S5; sw – sacral wing, fa – facies auricularis; smc – sacral median crest (spinous processes).

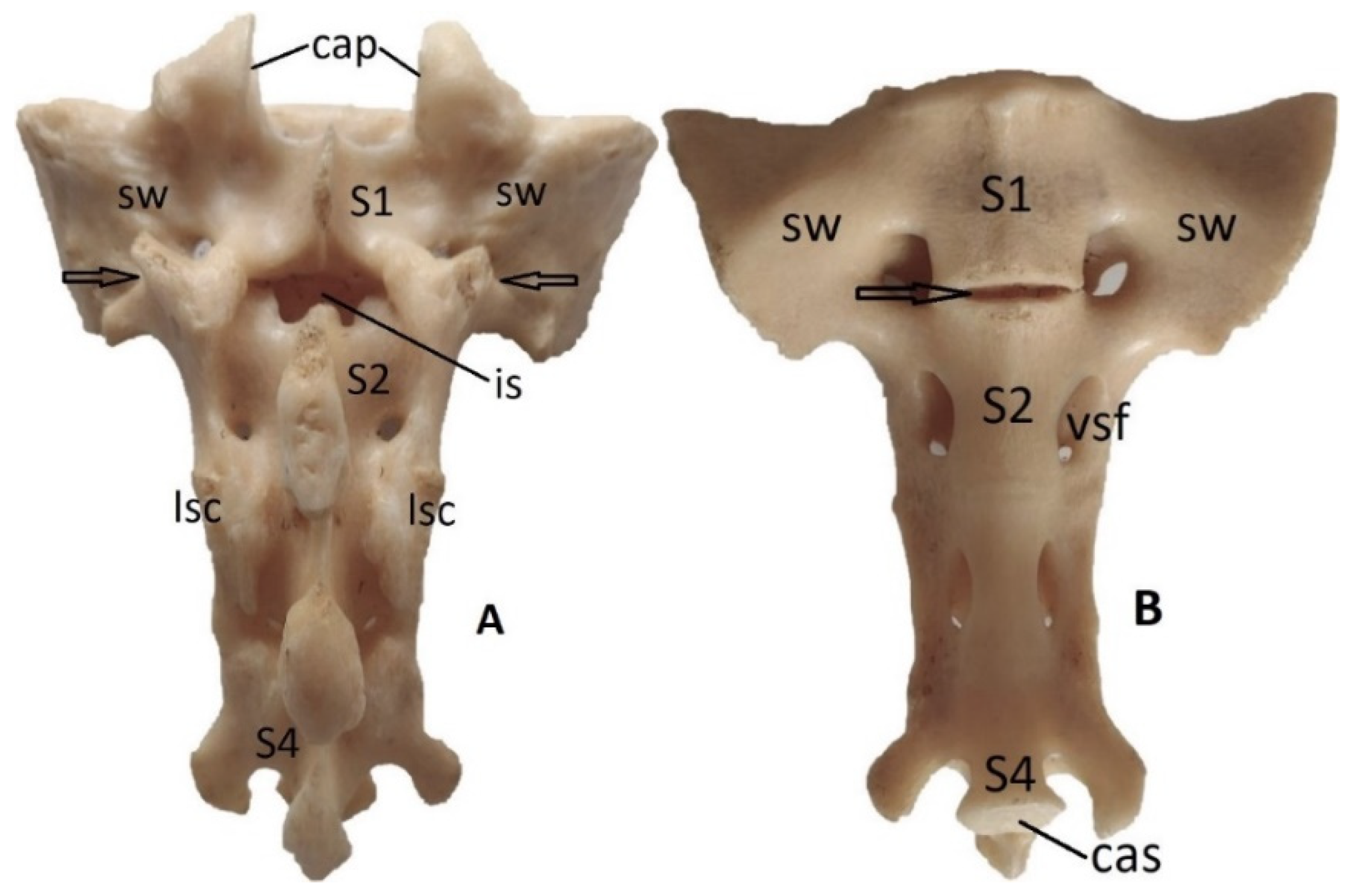

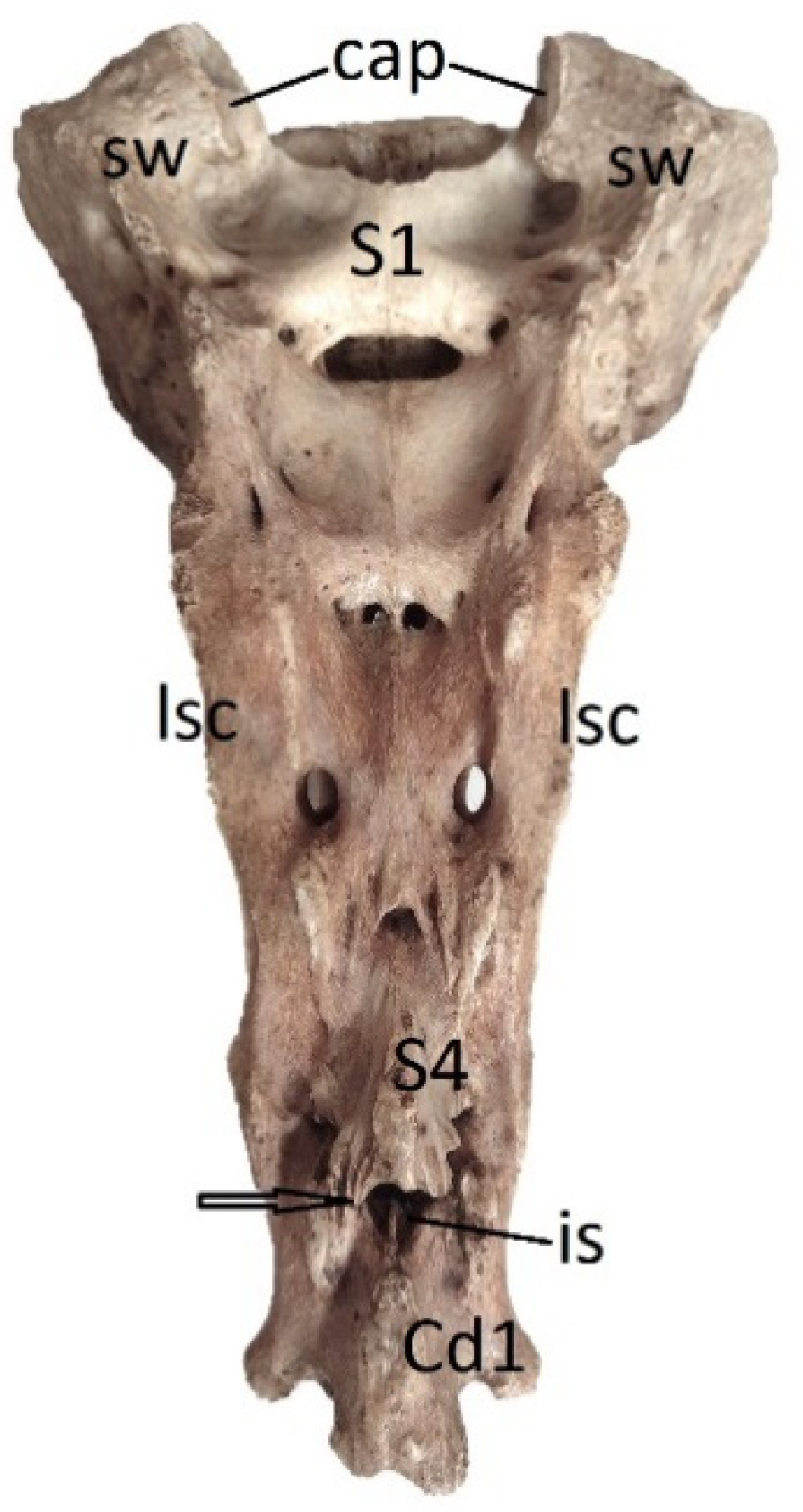

Figure 7.

Pig, male, 4 years – the sacralisation of the first caudal vertebra (Cd1), dorsal view: Cd1 is fused with S4 (last sacral vertebra) by their bodies and arches (arrow) and the interarcuate space (is) is narrower; S1 – first sacral vertebra; cap – cranial articular processes; sw – sacral wing; lsc – lateral sacral crest.

Figure 7.

Pig, male, 4 years – the sacralisation of the first caudal vertebra (Cd1), dorsal view: Cd1 is fused with S4 (last sacral vertebra) by their bodies and arches (arrow) and the interarcuate space (is) is narrower; S1 – first sacral vertebra; cap – cranial articular processes; sw – sacral wing; lsc – lateral sacral crest.

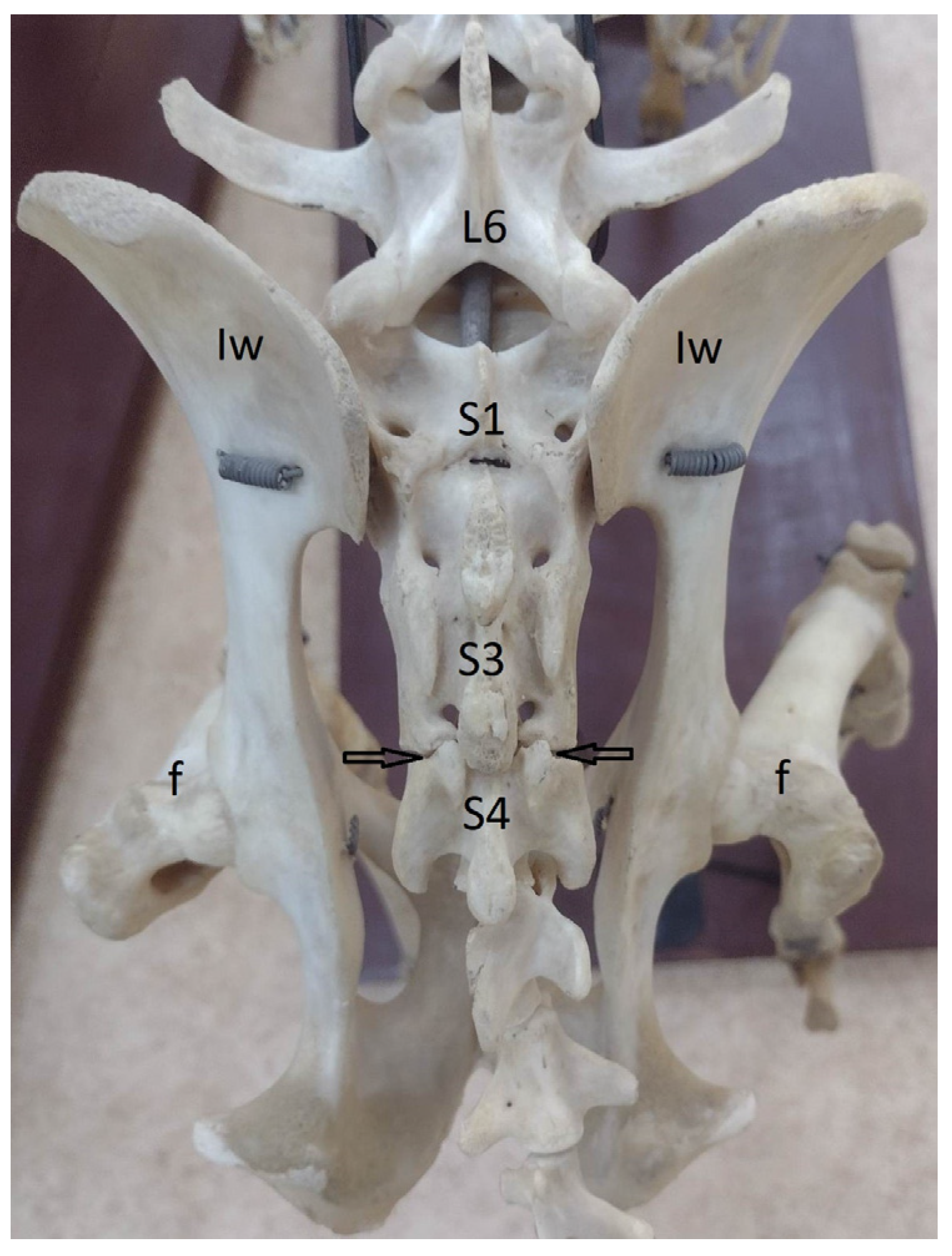

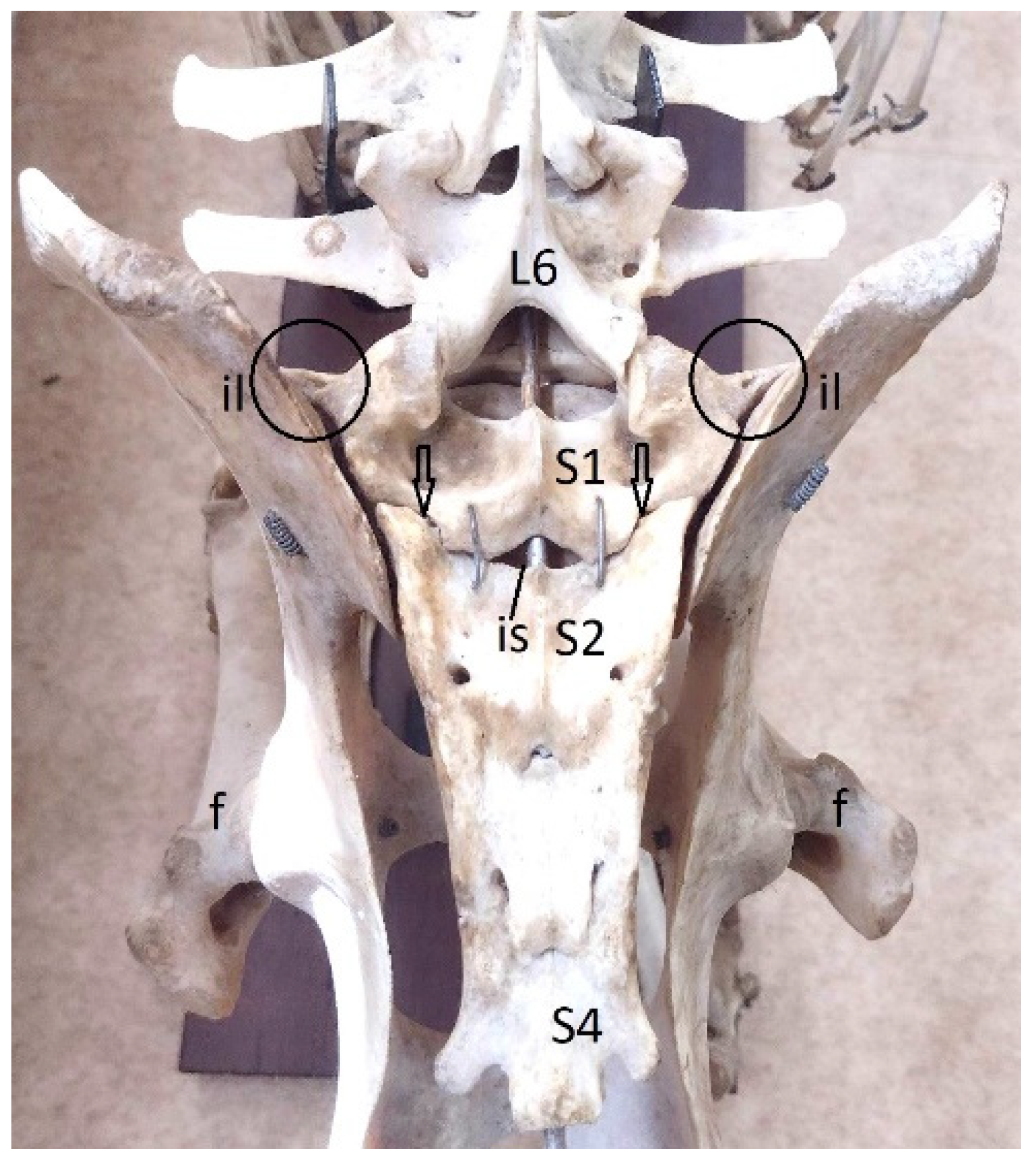

Figure 8.

Pig, F, 3 years, dorsal view – the lumbarisation of the first sacral vertebra (S1), and the detachment by the second one (arrows); the tendency of sacral wings to elongate as the transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae (circles): L6 – the sixth lumbar vertebra; S2 – second sacral vertebra; is – interarcuate space; il – ilium bone; S4 – the last sacral vertebra.

Figure 8.

Pig, F, 3 years, dorsal view – the lumbarisation of the first sacral vertebra (S1), and the detachment by the second one (arrows); the tendency of sacral wings to elongate as the transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae (circles): L6 – the sixth lumbar vertebra; S2 – second sacral vertebra; is – interarcuate space; il – ilium bone; S4 – the last sacral vertebra.

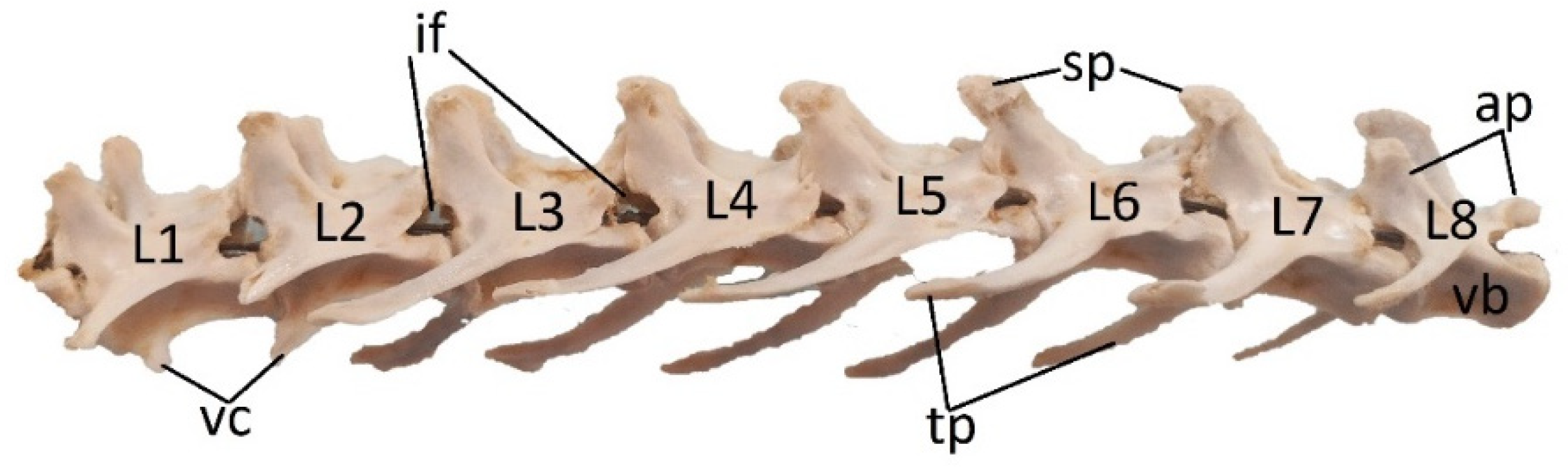

Figure 9.

Rabbit, ale, 5 years – lumbar spine and the presence of the 8th (L8) lumbar vertebra (supernumerary vertebra – lumbosacral transitional vertebra): L1-L7 – lumbar vertebrae 1-7; if – intervertebral foramina; vc – ventral crest; tp – transverse processes; sp – spinous processes; ap – articular processes; vb – vertebral body.

Figure 9.

Rabbit, ale, 5 years – lumbar spine and the presence of the 8th (L8) lumbar vertebra (supernumerary vertebra – lumbosacral transitional vertebra): L1-L7 – lumbar vertebrae 1-7; if – intervertebral foramina; vc – ventral crest; tp – transverse processes; sp – spinous processes; ap – articular processes; vb – vertebral body.

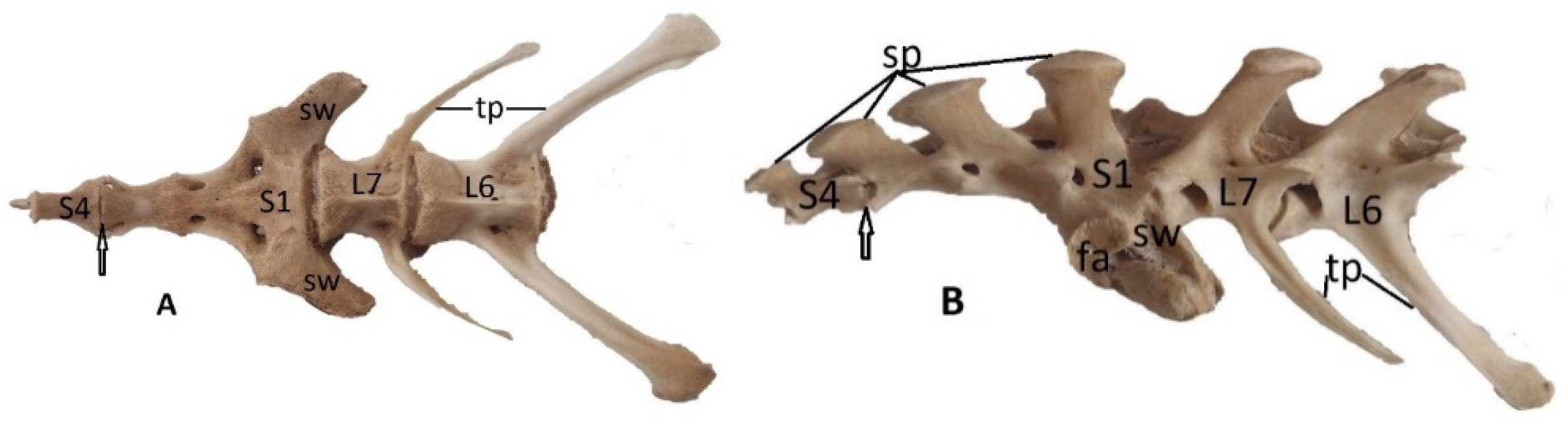

Figure 10.

Rabbit, male, 3 years – the tendency of caudalisation of the last sacral vertebra (S4) and the persistence of intervertebral disc (arrows); A - ventral view, B lateral view: L6 – the sixth lumbar vertebra; L7 – the seventh lumbar vertebra; S1 – first sacral vertebra; sw – sacral wing; fa – facies auricularis; tp – transverse processes; sp – spinous processes; S4 – the last sacral vertebra.

Figure 10.

Rabbit, male, 3 years – the tendency of caudalisation of the last sacral vertebra (S4) and the persistence of intervertebral disc (arrows); A - ventral view, B lateral view: L6 – the sixth lumbar vertebra; L7 – the seventh lumbar vertebra; S1 – first sacral vertebra; sw – sacral wing; fa – facies auricularis; tp – transverse processes; sp – spinous processes; S4 – the last sacral vertebra.

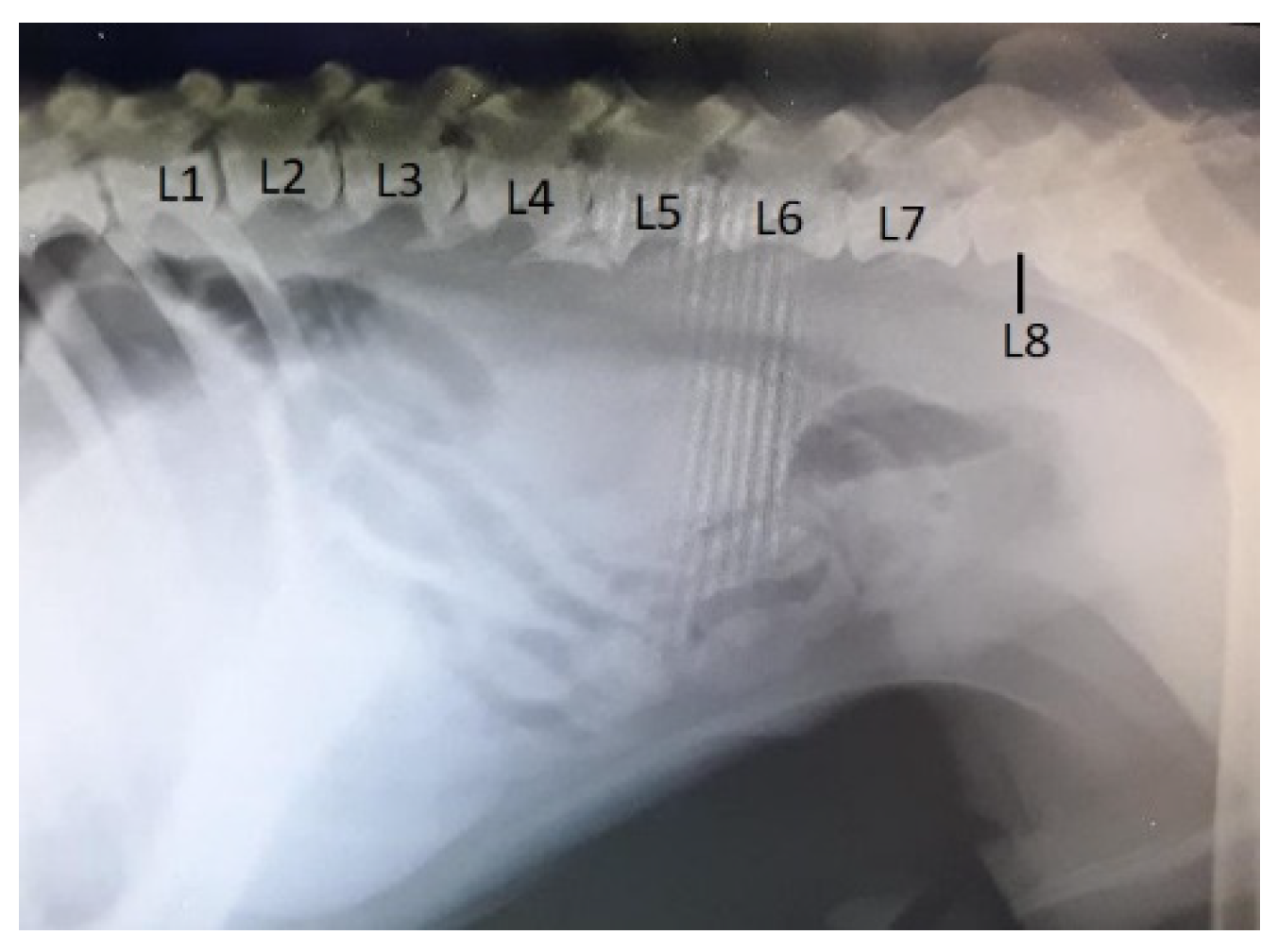

Figure 11.

Boxer dog, male, 6 years – supernumerary and transitional lumbo-sacral vertebra (L8), lateral view: shortening and sacralisation of L8; L1-L7 – lumbar vertebrae 1-7.

Figure 11.

Boxer dog, male, 6 years – supernumerary and transitional lumbo-sacral vertebra (L8), lateral view: shortening and sacralisation of L8; L1-L7 – lumbar vertebrae 1-7.

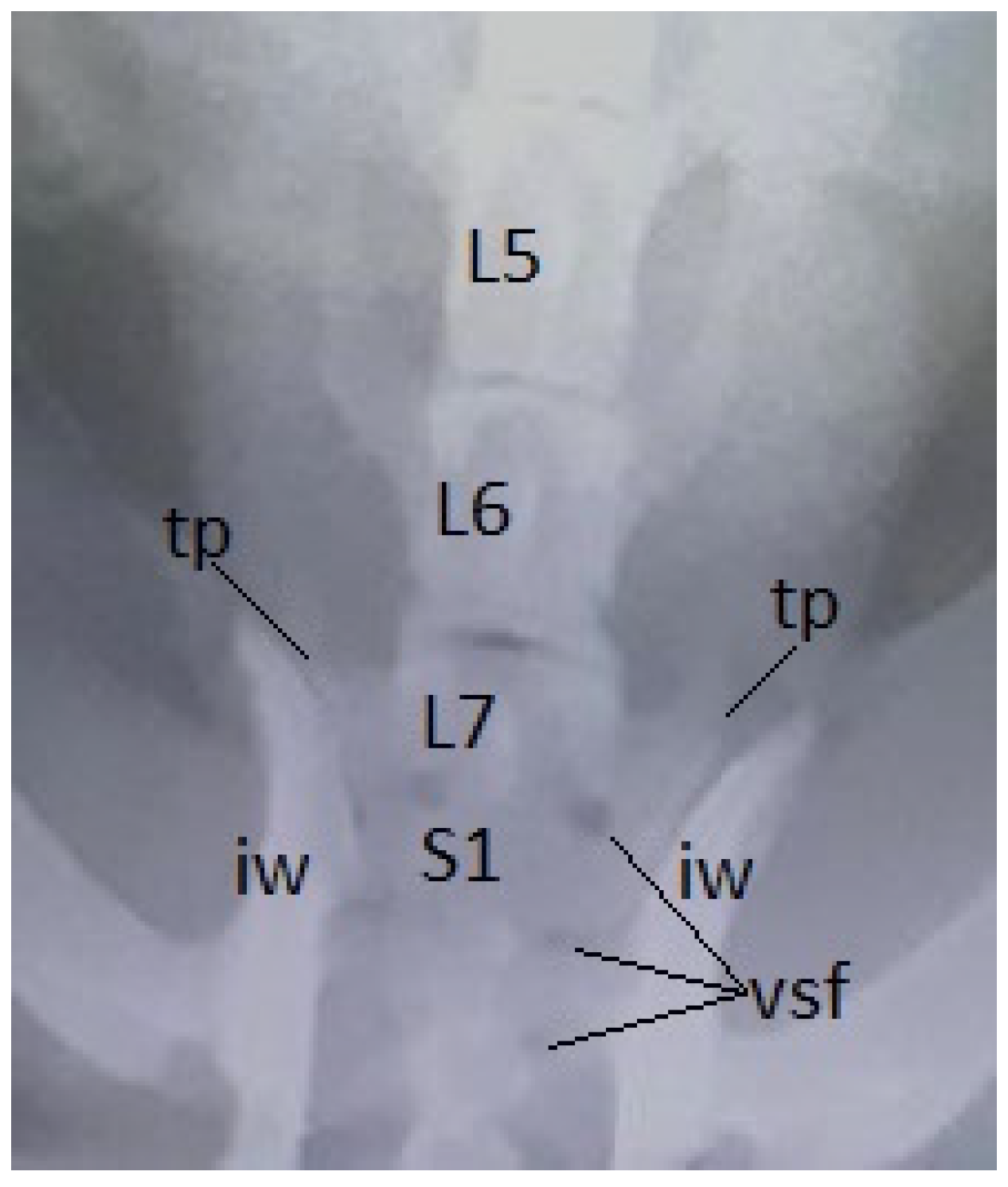

Figure 12.

Common breed dog, female, 14 years – supernumerary and asymmetric transitional lumbosacral vertebra (L8), ventro-dorsal view: shortening and sacralisation of L8; L1-L7 – lumbar vertebrae 1-7; the right transvers process (tp) of L8 is thin and not in contact with the iliac wing (iw), but the left one is fused with that of first sacral vertebra (S1) and takes contact with the iliac wing (arrow).

Figure 12.

Common breed dog, female, 14 years – supernumerary and asymmetric transitional lumbosacral vertebra (L8), ventro-dorsal view: shortening and sacralisation of L8; L1-L7 – lumbar vertebrae 1-7; the right transvers process (tp) of L8 is thin and not in contact with the iliac wing (iw), but the left one is fused with that of first sacral vertebra (S1) and takes contact with the iliac wing (arrow).

Figure 13.

Cat, female, 5 years – transitional lumbosacral vertebra-sacralization of L7 (last lumbar vertebra), ventro-dorsal view: L5 – the fifth lumbar vertebra; L6 – the sixth lumbar vertebra; S1 – the first sacral vertebra; tp – transverse processes of L7 – shortened and transformed in sacral wings; iw – iliac wing; vsf – ventral sacral foramina.

Figure 13.

Cat, female, 5 years – transitional lumbosacral vertebra-sacralization of L7 (last lumbar vertebra), ventro-dorsal view: L5 – the fifth lumbar vertebra; L6 – the sixth lumbar vertebra; S1 – the first sacral vertebra; tp – transverse processes of L7 – shortened and transformed in sacral wings; iw – iliac wing; vsf – ventral sacral foramina.

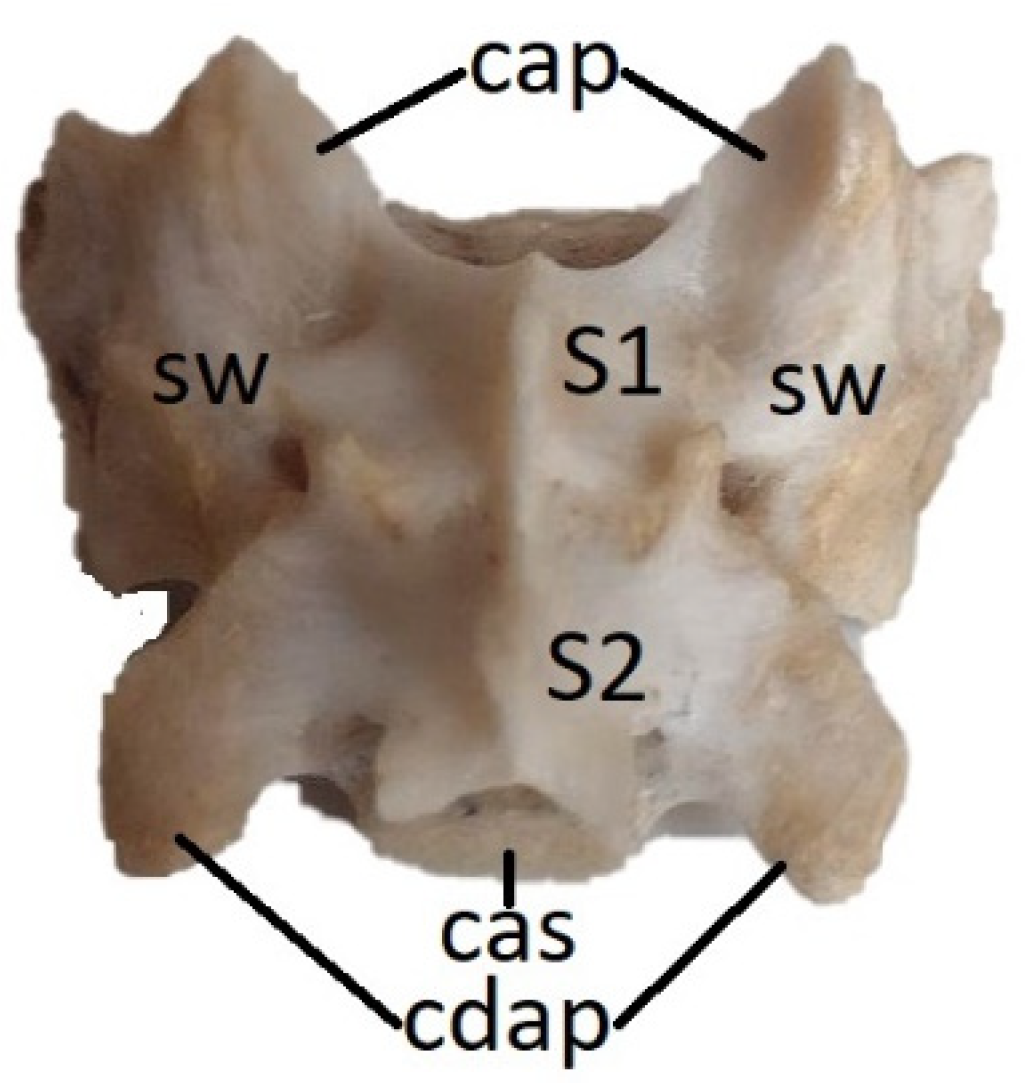

Figure 14.

Cat, female, 3 years – 2 sacral vertebrae-caudalisation of the last sacral vertebra (S3), dorsal view: S1 – first sacral vertebra; S2 – the second sacral vertebra; sw – sacral wing; cap – cranial articular processes; cas – caudal articular surface; cdap – caudal articular processes.

Figure 14.

Cat, female, 3 years – 2 sacral vertebrae-caudalisation of the last sacral vertebra (S3), dorsal view: S1 – first sacral vertebra; S2 – the second sacral vertebra; sw – sacral wing; cap – cranial articular processes; cas – caudal articular surface; cdap – caudal articular processes.

Table 1.

Data of animals of the present research.

Table 1.

Data of animals of the present research.

| Species |

Total number |

Age(years) |

Gender

(number) |

Breed (number) |

| ♀ |

♂ |

| Cow |

29 |

3-17 |

16 |

13 |

Common breed - 19 |

| Romanian Spotted Cattle – 6 |

| Romanian Brown - 3 |

| Sheep |

32 |

2-8 |

19 |

13 |

Common breed – 20 |

| Tigaia – 7 |

| Turcana – 5 |

| Horse |

31 |

5-20 |

24 |

7 |

Common breed - 21 |

| Romanian Saddle Horse – 6 |

| Romanian Half Heavyweight Horse - 4 |

| Pig |

26 |

2-7 |

18 |

8 |

Common breed – 19 |

| Large White Pig - 7 |

| Rabbit |

33 |

1-5 |

25 |

8 |

Common breed - 22 |

| Flemish Giant - 11 |

| Dog |

89 |

6 (months)-12 |

51 |

38 |

Common breed - 39 |

| Pekingese – 15 |

| French Bulldog – 13 |

| Boxer - 11 |

| Terrier breeds - 7 |

| Caniche - 4 |

| Cat |

57 |

1-7 |

27 |

30 |

Common European Breed - 36 |

| Scottish Fold - 8 |

| British Longhair - 7 |

| Russian Blue - 6 |

Table 2.

The prevalence (%) and the type of transitional vertebrae on species.

Table 2.

The prevalence (%) and the type of transitional vertebrae on species.

| Species |

Transitional vertebrae -total number and % |

Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae |

Sacrocaudal transitional vertebrae |

| Sacralisation (L7, L8) |

Lumbarisation (S1) |

Sacralisation

(Cd1) |

Caudalisation

(last sacral vertebra) |

| Cow |

3 (8,7%) |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

| Sheep |

3 (9,37%) |

- |

2 |

- |

1 |

| Horse |

4 (12,9%) |

- |

- |

4 |

- |

| Pig |

3 (11,53%) |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

| Rabbit |

3* (9,09%) |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| Dog |

4* (4,49%) |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

| Cat |

3 (5,26%) |

2 |

- |

- |

1 |