Submitted:

22 November 2023

Posted:

23 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

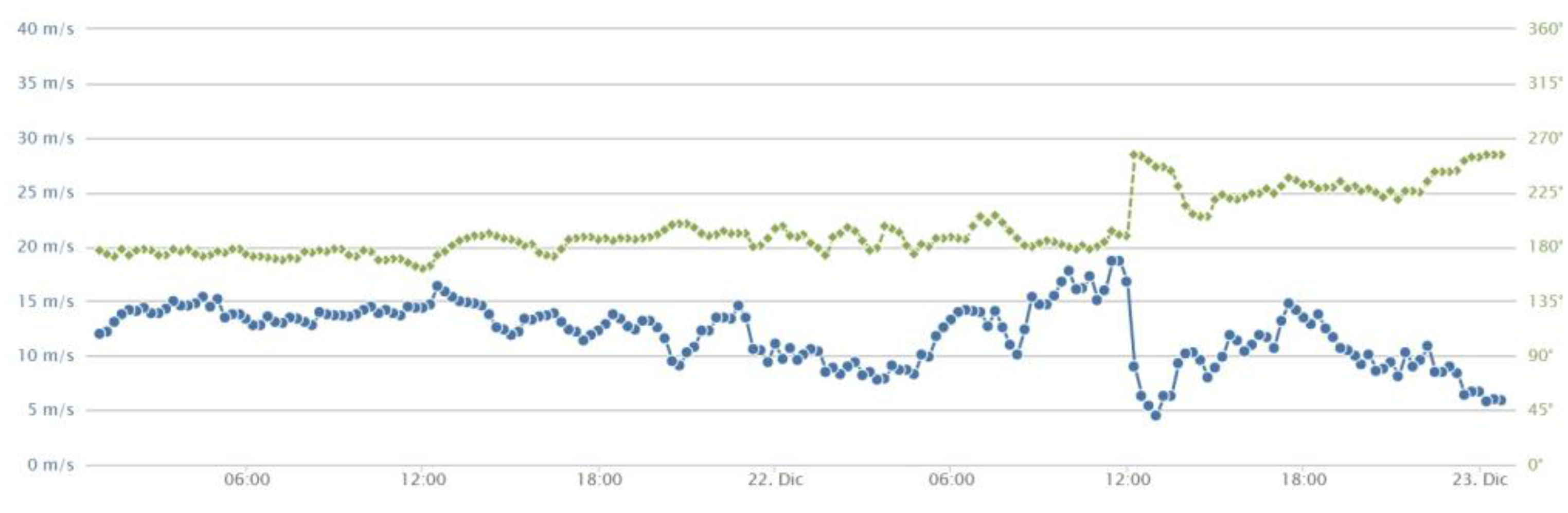

2. Study case

3. Method

3.1. Multi-Temporal (Geographic Object-Based) Analysis

3.2. Evaluation of the Marine Weather Conditions

4. Results

4.1. New Detection of Boulder Displacement

4.2. Check on Previously Detected Displacement

4.3. Storms and Boulder Incipient Motion

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Annual Mobility of Coastal Boulders

5.2. Causal Storm Inferences

5.3. Nearshore Wind Conditions and Wave Energy

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Initial position | Final position | ||||

| ID | latitude | longitude | latitude | longitude | A.I. |

| SCa | 40°08'17.09"N | 17°59'19.21"E | ind. | ind. | 3 |

| SCb | 40°08'18.36"N | 17°59'18.47"E | 40°08'19.03"N | 17°59'18.85"E | 3 |

| ID | ar | br | af | bf | cf | I | xi | xf | TD | Li | Sh | FI | PTS | MT |

| SCa | 3.3 | 1.2 | - | - | - | - | 0.8 | ind. | - | L | - | - | CE | - |

| SCb | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 5° | 18.8 | 21.6 | 15.4 | L | O | 2.5 | SA | OV |

| Initial position | Final position | ||||

| ID | latitude | longitude | latitude | longitude | A.I. |

| PILa | 39°55'22.66"N | 18°03'35.76"E | 39°55'22.72"N | 18°03'35.80"E | 3 |

| PILb | 39°55'22.60"N | 18°03'35.42"E | 39°55'22.68"N | 18°03'35.51"E | 3 |

| PILc | 39°55'22.27"N | 18°03'34.62"E | 39°55'22.35"N | 18°03'34.66"E | 2 or 3 |

| PILd | 39°55'22.24"N | 18°03'34.49"E | 39°55'22.33"N | 18°03'34.50"E | 3 |

| PILe | ind. | ind. | 39°55'23.54"N | 18°03'32.43"E | 3 |

| PILf | 39°55'23.83"N | 18°03'31.60"E | 39°55'23.88"N | 18°03'31.63"E | 3 |

| PILg | 39°55'23.97"N | 18°03'31.61"E | 39°55'24.11"N | 18°03'31.72"E | 3 |

| PILh | ind. | ind. | 39°55'24.08"N | 18°03'30.58"E | 3 |

| PILi | 39°55'24.39"N | 18°03'31.08"E | 39°55'24.49"N | 18°03'31.12"E | 3 |

| PILj | 39°55'25.09"N | 18°03'27.70"E | 39°55'25.10"N | 18°03'27.78"E | 3 |

| PILk | 39°55'25.38"N | 18°03'27.86"E | ind. | ind. | 3 |

| PILl | 39°55'26.41"N | 18°03'27.20"E | 39°55'26.49"N | 18°03'27.26"E | 3 |

| PILm | 39°55'26.86"N | 18°03'26.56"E | 39°55'26.96"N | 18°03'26.64"E | 3 |

| PILn | 39°55'27.29"N | 18°03'26.47"E | 39°55'27.32"N | 18°03'26.54"E | 3 |

| ID | ar | br | af | bf | cf | I | xi | xf | TD | Li | Sh | FI | PTS | MT |

| PILa | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0-5° | 10.8 | 12.4 | 3.6 | C | O | 2.6 | SA | OV |

| PILb | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0-5° | 9.4 | 10.5 | 4.1 | C | B | 3.5 | SA | OV |

| PILc | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.4 | ~20° | 12.4 | 14.7 | 2.5 | C | B | 3 | SA | OV |

| PILd | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0-5° | 13.6 | 15.6 | 2.6 | C | B | 2.4 | SA | OV |

| PILe | 2.3 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.3 | ~15° | ind. | 13.2 | - | C | O | 6.7 | SA,SB | ST,OV |

| PILf | 2.2 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.5 | ~60° | 10.9 | 12.5 | 1.5 | C | B | 3.6 | SA | SL |

| PILg | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.6 | ~10° | 10.6 | 15.5 | 4.8 | C | O | 2.3 | SA | OV |

| PILh | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 5° | ind. | 3.9 | - | L | B | 2.9 | SA,SB | ind. |

| PILi | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 5° | 18.8 | 20.4 | 2.6 | C | B | 4.1 | SA | ST |

| PILj | 3.1 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 5° | 0.7 | 1.9 | 1.6 | C | O | 4 | SB | SL |

| PILk | 2.0 | 1.4 | - | - | - | - | 6.9 | ind. | - | - | - | - | SA | - |

| PILl | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0-5° | 7.0 | 8.9 | 3.3 | L | P | 2 | SA | OV |

| PILm | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0-5° | 1.1 | 3.7 | 3.2 | C | B | 3.7 | SA | OV |

| PILn | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.4 | ~55° | 4.4 | 6.2 | 1.9 | C | O | 4.9 | SA | OV |

| Initial position | Final position | ||||

| ID | latitude | longitude | latitude | longitude | A.I. |

| ROa | 30°54'45.53"N | 18°04'20.88"E | 30°54'47.70"N | 18°04'20.99"E | 3 |

| ROb | 30°54'46.19"N | 18°04'20.51"E | 30°54'46.21"N | 18°04'20.55"E | 3 |

| ROc | 30°54'46.87"N | 18°04'20.58"E | 30°54'46.90"N | 18°04'20.69"E | 3 |

| ROd | 30°54'47.88"N | 18°04'18.76"E | 30°54'48.03"N | 18°04'18.79"E | 3 |

| ROe | ind. | ind. | 30°54'48.30"N | 18°04'17.88"E | 3 |

| ROf | 30°54'48.40"N | 18°04'17.90"E | 30°54'48.45"N | 18°04'17.96"E | 3 |

| ROg | ind. | ind. | 30°54'48.39"N | 18°04'17.57"E | 3 |

| ROh | ind. | ind. | 30°54'48.43"N | 18°04'17.54"E | 3 |

| ROi | 30°54'48.38"N | 18°04'17.34"E | 30°54'48.44"N | 18°04'17.36"E | 3 |

| ROj | 30°54'48.40"N | 18°04'17.44"E | 30°54'48.51"N | 18°04'17.47"E | 3 |

| ROk | 30°54'48.45"N | 18°04'17.59"E | 30°54'48.52"N | 18°04'17.37"E | 3 |

| ROl | ind. | ind. | 30°54'48.79"N | 18°04'17.15"E | 4 |

| ROm | 30°54'49.29"N | 18°04'16.85"E | 30°54'49.40"N | 18°04'16.95"E | 3 |

| ROn | 30°54'49.02"N | 18°04'15.97"E | 30°54'48.48"N | 18°04'16.41"E | 3 |

| ROo | ind. | ind. | 30°54'49.68"N | 18°04'16.38"E | 2 or 3 |

| ROp | ind. | ind. | 30°54'49.71"N | 18°04'16.43"E | 2 or 3 |

| ID | ar | br | af | bf | cf | I | xi | xf | TD | Li | Sh | FI | PTS | MT |

| ROa | 2.7 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0-5° | 12.3 | 18.5 | 5.8 | C | P | 2.5 | SA | OV |

| ROb | 2.8 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0-5° | 5.7 | 6.7 | 1.9 | C | B | 3.6 | SA | SL |

| ROc | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0-5° | 15.9 | 18.2 | 2.5 | C | O | 3.1 | SA | ST |

| ROd | 2.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.7 | ~20° | 10.4 | 14.7 | 4.5 | C | O | 2.8 | SA | OV |

| ROe | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0-5° | ind. | 11.2 | - | C | O | 3.9 | SA,SB | ind. |

| ROf | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0-5° | 13.6 | 15.8 | 2.1 | C | O | 2.2 | SA | ST |

| ROg | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | ~25° | ind. | 14.6 | - | C | B | 2.7 | SA,SB | ST |

| ROh | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0-5° | ind. | 14.4 | - | C | P | 1.8 | SA,SB | ST |

| ROi | 2.8 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 0.7 | ~10° | 11.1 | 12.6 | 1.9 | C | B | 2.9 | SA | ST |

| ROj | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.8 | ~20° | 14.4 | 16.7 | 3.1 | C | B | 2.6 | SA | OV |

| ROk | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | ~15° | 14.2 | 16.1 | 2.1 | C | O | 2.1 | SA | OV |

| ROl | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.3 | ~20° | ind. | 9.3 | - | C | O | 5.2 | SA,SB | OV |

| ROm | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0-5° | 20.3 | 25.2 | 4.8 | C | P | 2.2 | SA | ST |

| ROn | 3.1 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 0.5 | ~20° | 4.2 | 20.7 | 17.1 | C | O | 4.9 | SA | ST |

| ROo | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | ~10° | ind. | 25.3 | - | C | B | 2.3 | SA,SB | ST,OV |

| ROp | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.5 | ~25° | ind. | 26.4 | - | C | O | 2.8 | SA,SB | ST,OV |

| Initial position | Final position | ||||

| ID | latitude | longitude | latitude | longitude | A.I. |

| SGa | ind. | ind. | 39°54'03.86"N | 18°05'09.25"E | 3 |

| SGb | ind. | ind. | 39°54'03.99"N | 18°05'09.47"E | 3 |

| SGc | ind. | ind. | 39°54'04.46"N | 18°05'09.50"E | 3 |

| SGd | 39°54'04.18"N | 18°05'09.34"E | 39°54'04.49"N | 18°05'09.38"E | 3 |

| SGe | 39°54'04.52"N | 18°05'08.72"E | 39°54'04.73"N | 18°05'08.76"E | 3 |

| SGf | 39°54'05.57"N | 18°05'08.45"E | 39°54'05.61"N | 18°05'08.53"E | 3 |

| ID | ar | br | af | bf | cf | I | xi | xf | TD | Li | Sh | FI | PTS | MT |

| SGa | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0-5° | ind. | 14.9 | - | C | O | 3.1 | SA,SB | ST,OV |

| SGb | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0-5° | ind. | 22.3 | - | C | B | 4.7 | SA,SB | ST,OV |

| SGc | 1.9 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0-5° | ind. | 31.4 | - | C | O | 5 | SA,SB | ST,OV |

| SGd | 2.1 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 0.3 | ~45° | 22.8 | 28.6 | 9.5 | C | B | 6 | SA | ST |

| SGe | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0-5° | 13.8 | 18.2 | 6.5 | C | O | 2.8 | SA | ST |

| SGf | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.6 | ~30° | 10.4 | 11.7 | 2.4 | C | O | 2.2 | SA | OV |

| Site | Boulder ID1 |

|---|---|

| Santa Caterina | SCa |

| Pilella | PILa, PILb, PILc, PILd, PILf, PILg, PILi, PILj, PILl, PILm, PILn |

| Posto Rosso | ROa, ROb, ROc, ROd, ROf, ROi, ROj, ROk, ROm, ROn |

| Torre San Giovanni | SGd, SGe, SGf |

| Site | Boulder ID1 |

|---|---|

| Punta Prosciutto | PRa, PRb, PRc, PRd, PRe, PRf, PRi, PRj, PRk, PRl, PRm, PRq, PRr |

| Sant’Isidoro | SIf, SIg |

| Punta Pizzo | PIa, PIb, PIc, PId, PIe, PIg, PIh, PIj, PIn, PIp, PIr |

| Mancaversa | MAa, MAb, MAc, MAf, MAg, MAh, MAi, MAj, MAk, MAl, MAm |

| Torre Suda | SUa, SUe, SUf, SUh, SUi, SUn |

| Capilungo | CAa, CAb, CAc, CAd, CAe, CAf |

| Ciardo | CIa, CIb, CIc, CId |

Appendix B

| 00:00 | 06:00 | 12:00 | 18:00 | |||||||

| Storm | Ua | Um | U30 | D | U30 | D | U30 | D | U30 | D |

| 12/11/20191 | 8.5 | 24.0 | 9.8 | 106° | 18.1 | 107° | 13.4 | 145° | 11.7 | 164° |

| 13/11/20191 | 6.0 | 19.8 | 15.4 | 169° | 12.7 | 167° | 12.1 | 173° | 4.3 | 172° |

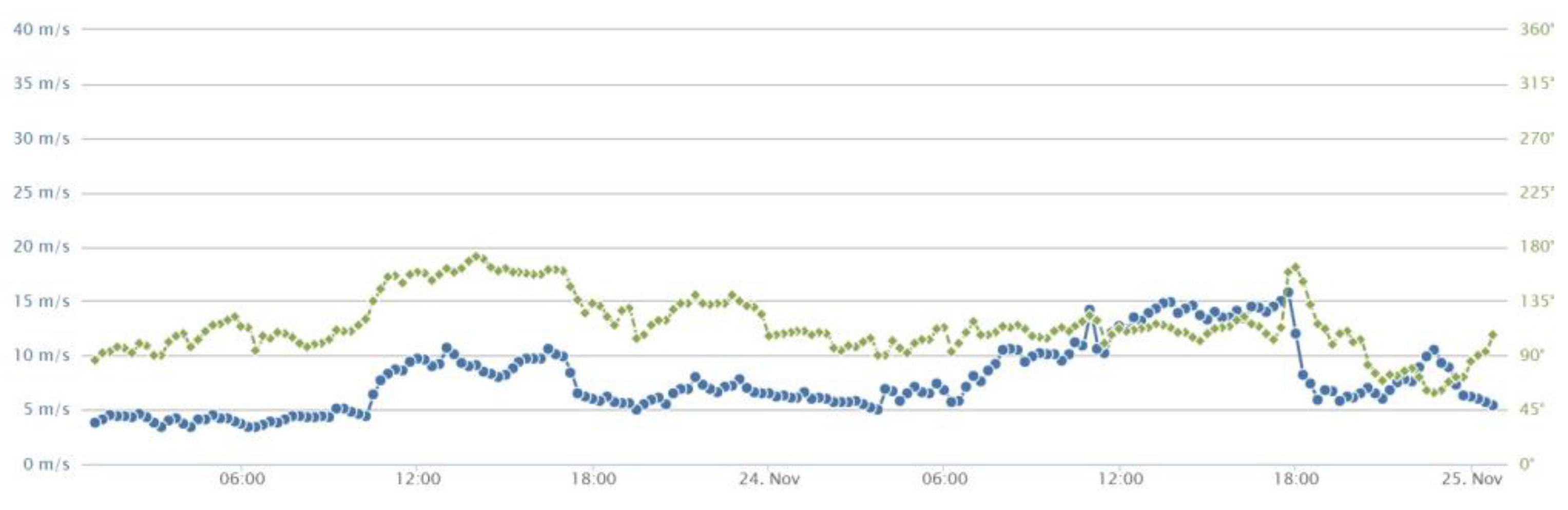

| 24/11/2019 | 5.5 | 19.3 | 4.9 | 145° | 7.4 | 129° | 14.5 | 107° | 16.3 | 112° |

| 22/12/2019 | 4.9 | 18.1 | 8.2 | 191° | 9.4 | 179° | 14.0 | 222° | 7.8 | 259° |

| 02/03/2020 | 3.7 | 12.7 | 7.4 | 153° | 3.0 | 53° | 6.1 | 139° | 8.3 | 146° |

References

- Nandasena, N.A.K.; Paris, R.; Tanaka, N. Reassessment of hydrodynamic equations to initiate boulder transport by high energy events (storms, tsunamis). Mar. Geol. 2011, 281, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.B.; Cox, R.; Dias, F. Storm waves may be the source of some “tsunami” coastal boulder deposits. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL090775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Rose, M.; Martano, P. The Imprint of Recent Meteorological Events on Boulder Deposits along the Mediterranean Rocky Coasts. Climate 2022, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, A.; Etienne, S.; Planes, S. High-energy events, boulder deposits and the use of very high resolution remote sensing in coral reef environments. J. Coastal Res. Special Issue 2013, 65, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, A.; Etienne, S.; Jeanson, M. Three-dimensional structure of coral reef boulders transported by stormy waves using the very high resolution WorldView-2 satellite. J. Coastal Res. Special Issue 2016, 75, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R. Megagravel deposits on the west coast of Ireland show the impacts of severe storms. Weather 2020, 75, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, D.A. Finding Coastal Megaclast Deposits: A Virtual Perspective. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.B.; Mori, N.; Yasuda, T.; Shimozono, T.; Tomiczek, T.; Donahue, A.; Shimura, T.; Imai, Y. Extreme block and boulder transport along a cliffed coastline (Calicoan Island, Philippines) during Super Typhoon Haiyan. Mar. Geol. 2017, 383, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, F.; Mhammdi, N.; Emran, A.; Hakdaoui, S. A case of uplift and transport of a large boulder by the recent winter storms at Dahomey beach (Morocco). In Proceedings of the IX Symposium on the Iberian Atlantic Margin, Coimbra, Portugal, 4-7 September 2018; 2 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Haslett, S.; Wong, B. Reconnaissance survey of coastal boulders in the Moro Gulf (Philippines) using Google Earth imagery: Initial insights into Celebes Sea tsunami events. Bull. Geol. Soc. Malaysia 2019, 68, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Rose, M.; Martano, P.; Orlanducci, L. Coastal Boulder Dynamics Inferred from Multi-Temporal Satellite Imagery, Geological and Meteorological Investigations in Southern Apulia, Italy. Water 2021, 13, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.M.; Woods, J.L.D.; Naylor, L.A.; Hansom, J.D.; Rosser, N.J. Intertidal boulder-based wave hindcasting can underestimate wave size: Evidence from Yorkshire, UK. Mar. Geol. 2019, 411, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastewell, L.J.; Schaefer, M.; Bray, M.; Inkpen, R. Intertidal boulder transport: A proposed methodology adopting Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology to quantify storm induced boulder mobility. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2019, 44, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Pazo, A.; Perez-Alberti, A.; Trenhaile, A. Tracking clast mobility using RFID sensors on a boulder beach in Galicia, NW Spain. Geomorphology 2021, 373, 107514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autret, R.; Dodet, G.; Suanez, S.; Roudaut, G.; Fichaut, B. Long–term variability of supratidal coastal boulder activation in Brittany (France). Geomorphology 2018, 304, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmeister, D.; Curdt, C; Bareth, G. Monitoring the sedimentary budget and dislocated boulders in western Greece—Results since 2008. Sedimentology 2020, 67, 1411–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morucci, S.; Picone, M.; Nardone, G.; Arena, G. Tides and waves in the central Mediterranean Sea. J. Oper. Oceanogr. 2016, 9, s10–s17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentale, F.; Furcolo, P.; Pugliese Carratelli, E.; Reale, F.; Contestabile, P.; Tomasicchio, G.R. Extreme wave analysis by integrating model and wave buoy data. Water 2018, 10, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciricugno, L.; Delle Rose, M.; Fidelibus, C.; Orlanducci, L.; Mangia, M. Sullo spostamento di massi costieri causato da onde “estreme” (costa ionica salentina). Geol. Territ. 2019, 16, 15–23. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Delle Rose, M. , Fidelibus, C.; Martano, P.; Orlanducci, L. Storm-induced boulder displacements: Inferences from field surveys and hydrodynamic equations. Geosciences 2020, 10, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Rose, M.; Ciricugno, L.; Fidelibus, C.; Martano, P.; Marzo. L.; Orlanducci, L. Considerazioni geologiche su processi morfodinamici causati sulla costa ionica salentina da recenti tempeste. Geol. Territ. 2020, 18, 5–15. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Spano, D.; Snyder, R.L.; Cesaraccio, C. Mediterranean Climates. In Phenology: An Integrative Environmental Science; Schwartz, M.D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2003; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lionello, P.; Malanotte-Rizzoli, P.; Boscolo, R.; Alpert, P.; Artale, V.; Li, L.; Luterbacher, J.; May,W. ; Trigo, R.; Tsimplis, M.; et al. The Mediterranean Climate: An Overview of the Main Characteristics and Issues. Dev. Earth Environ. Sci. 2006, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zito, G.; Ruggiero, L.; Zuanni, F. Aspetti meteorologici e climatici della Puglia. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on “Clima, Ambiente e Territorio nel Mezzogiorno”, Taormina, Italy, 11–12 December 1989; CNR: Roma, Italy, 1991; pp. 43–73. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Mastronuzzi, G.; Pignatelli, C. The boulder berm of Punta Saguerra (Taranto, Italy): a morphological imprint of the Rossano Calabro tsunami of April 24, 1836? Earth Planet. Sp. 2012, 64, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarin, C.; Valentini, A.; Vodopivec, M.; Klaric, D.; Massaro, G.; Bajo, M.; De Pascalis, F.; Fadini, A.; Ghezzo, M.; Menegon, S.; et al. Integrated sea storm management strategy: The 29 October 2018 event in the Adriatic Sea. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarin, C.; Bajo, M.; Benetazzo, A.; Cavaleri, L.; Chiggiato, J.; Barbariol, F.; Bastianini, M.; Bertotti, L.; Davolio, S.; Magnusson, L.; et al. Local and large-scale controls of the exceptional Venice floods of November 2019. Prog. Oceanogr. 2021, 197, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Dutykh, D.; Dudley, J.M.; Dias, F. Extreme wave runup on a vertical cliff. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3138–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Burningham, H.; Griffiths, D.; Yao, Yao. Coastal boulder movement on a rocky shoreline in northwest Ireland from repeat UAV surveys using Structure from Motion photogrammetry. Geomorphology 2023, 440, 108883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Puglia - Area Politiche per la mobilita e qualita urbana - Servizio Assetto del Territorio. Available online: http://webapps.sit.puglia.it/freewebapps/Idrogeomorfologia/index.html (accessed on 16 June 2023). (In Italian).

- Hay, G.J.; Castilla, G. Geographic Object-Based Image Analysis (GEOBIA): a new name for a new discipline. In Object-Based Image Analysis: Spatial Concepts for Knowledge-Driven Remote Sensing Applications, Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Blaschke, T., Lang, S., Hay, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke, T.; Hay, G.J.; Kelly, M.; Lang, S.; Hofmann, P.; Addink, E.; Queiroz Feitosa, R.; van der Merr, F.; van der Werff, H.; van Coillie, F.; et al. Geographic Object-Based Image Analysis—Towards a new paradigm. J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 87, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Weng, Q.; Hay, G.J.; He, Y. Geographic object-based image analysis (GEOBIA): Emerging trends and future opportunities. GIScience Remote Sens. 2018, 55, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipson, W. Problem solving with remote sensing. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1980, 46, 1335–1338. [Google Scholar]

- White, A.R. Human expertise in the interpretation of remote sensing data: A cognitive task analysis of forest disturbance attribution. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2019, 74, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Dustdar, S.; Ranjan, R.; Morgan, G.; Dong, Y.; Wang, L. Remote Sensing Image Interpretation With Semantic Graph-Based Methods: A Survey. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 4544–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, S.A. Image Interpretation in Geology; Allen & Unwin: London, Uk, 1987; p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister, D. Mapping of subaerial clasts. In Geological Records of Tsunamis and Other Extreme Waves; Engel, M., Pilarczyk, J., May, S.M., Brill, D., Garrett, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020; pp. 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Walstra, J.; Heyvaert, V.; Verkinderen, Peter. Mapping Late Holocene Landscape Evolution and Human Impact - A Case Study from Lower Khuzestan (SW Iran). In Developments in Earth Surface Processes, Volume 15; Smith, M.J., Paron, P., Griffiths, J.S, Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2011; pp. 551–575.

- Castilla, G.; Hay, G.J. Image objects and geographic objects. In Object-Based Image Analysis: Spatial Concepts for Knowledge-Driven Remote Sensing Applications, Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Blaschke, T., Lang, S., Hay, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, C.; Blaschke, T. A multi-scale segmentation/object relationship modelling methodology for landscape analysis. Ecol. Model. 2003, 168, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shettigara, V.K.; Sumerling, G.M. Height determination of extended objects using shadows in SPOT images. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1998, 64, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dare, P.M. Shadow analysis in high-resolution satellite imagery of urban areas. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2005, 71, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, T.; Feizizadeh, B.; Holbling, D. Object-Based Image Analysis and Digital Terrain Analysis for Locating Landslides in the Urmia Lake Basin, Iran. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 4806–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Pekkan, E. Fault-Based Geological Lineaments Extraction Using Remote Sensing and GIS—A Review. Geosciences 2021, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.-V.; Chou, T.-Y.; Fang, Y.-M.; Wang, C.-T.; Mu, C.-Y.; Tuan, N.Q.; Huong, D.T.V.; Hanh, H.V.; Phong, D.N.N. Robust Extraction of Soil Characteristics Using Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.; Frauenfelder, R.; Ruther, D.; Nava, L.; Rubensdotter, L.; Strout, J.; Nordal, S. Multi-Temporal Satellite Image Composites in Google Earth Engine for Improved Landslide Visibility: A Case Study of a Glacial Landscape. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann,W. ; Kelletat, D.; Scheffers, A. Boulder transport by storms – Extreme-waves in the coastal zone of the Irish west coast. Mar. Geol. 2018, 399, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetjen, J.; Engel, M.; Pudasaini, S.P.; Schuettrumpf, H. Significance of boulder shape, shoreline configuration and pre-transport setting for the transport of boulders by tsunamis. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2020, 45, 2118–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasena, N.A.K.; Scicchitano, G.; Scardino, G.; Milella, M.; Piscitelli, A.; Mastronuzzi, G. Boulder displacements along rocky coasts: A new deterministic and theoretical approach to improve incipient motion formulas. Geomorphology 2022, 407, 108217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blott, S.G.; Pye, K. Particle shape: a review and new methods of characterization and classification. Sedimentology 2008, 55, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, T.C.; Mcpherson, J.G. Grain-size and textural classification of coarse sedimentary particles. J. Sed. Res. 1999, 69, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Burningham, H. Boulder dynamics on an Atlantic-facing rock coastline, northwest Ireland. Mar. Geol. 2011, 283, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causon Deguara, J.; Gauci, R. Evidence of extreme wave events from boulder deposits on the south-east coast of Malta (Central Mediterranean). Nat. Hazards 2017, 86, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noormets, R.; Felton, E.A.; Crook, K.A.W. Sedimentology of rocky shorelines: 2. Shoreline megaclasts on the north shore of Oahu, Hawaii–origins and history. Sediment. Geol. 2002, 150, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottershead, D.N.; Soar, P.J.; Bray, M.J.; Hastewell, L.J. Reconstructing boulder deposition histories: Extreme wave signatures on a complex rocky shoreline of Malta. Geosciences 2020, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccotti, P. Wave Mechanics for Ocean Engineering; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–496. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, M. Coastal Storm Definition. In Coastal Storms; Ciavola, P., Coco, G., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- GLOBO-BOLAM-MOLOCH forecasts. Available online: https://www.isac.cnr.it/dinamica/projects/forecasts/bolam/ (accessed on 10/09/2023).

- Hasselmann, K.; Ross, D.B.; Muller, P.; Sell, W. A parametric wave prediction model. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1975, 6, 200–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.A. (Ed.) Coastal Meteorology; Academic Press, US; 260 pp., 1988.

- Burroughs, L. Wave forecasting by manual methods. In Guide to Wave Analysis and Forecasting; World Meteorological Organization, Ed.; Secretariat of World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, D.K. Wave hindcasting. In Encyclopedia of Coastal Science; Finkl, C.W., Makowski, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1859–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Puglia. Annali Idrologici. 2017. Available online: https://protezionecivile.puglia.it/documents/3171874/3243680/.

- annale2017.pdf/ (accessed on 10/09/2023). (In Italian)

- Regione Puglia. Annali Idrologici. 2018. Available online: https://protezionecivile.puglia.it/documents/3171874/3243680/.

- annale2018.pdf/ (accessed on 10/09/2023). (In Italian)

- Regione Puglia. Annali Idrologici. 2019. Available online: https://protezionecivile.puglia.it/documents/3171874/3243680/.

- annale2019.pdf/ (accessed on 10/09/2023). (In Italian)

- Regione Puglia. Annali Idrologici. 2020. Available online: https://protezionecivile.puglia.it/documents/3171874/3243680/.

- annale2020rev2.pdf/ (accessed on 10/09/2023). (In Italian)

- Regione Puglia. Annali Idrologici. 2021. Available online: https://protezionecivile.puglia.it/documents/3171874/3243680/.

- annale2021.pdf/ (accessed on 10/09/2023). (In Italian)

- SIMOP, Sistema Informativo Meteo Oceanografico delle coste Pugliesi, Autorita di Bacino della Puglia. Available online: http://93.51.158.171/web/simop/home (accessed on 10/09/2023).

- Nott, J. Waves, coastal boulder deposits and the importance of the pre-transport setting. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2003, 210, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noormets, R.; Felton, E.A.; Crook, K.A.W. Sedimentology of rocky shorelines: 3. Hydrodynamics of megaclasts emplacement and transport on a shore platform, Oahu, Hawaii. Sediment. Geol. 2004, 172, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasena, N.A.K.; Tanaka, N.; Sasaki, Y.; Osada, M. Boulder transport by the 2011 Great East Japan tsunami: comprehensive field observations and whither model predictions? Mar. Geol. 2013, 346, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasena, N.A.K. Perspective of incipient motion formulas: boulder transport by high-energy waves. In Geological Records of Tsunamis and Other Extreme Waves; Nandasena, N.A.K., Engel, M., Pilarczyk, J., May, S.M., Brill, D., Garrett, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020; pp. 641–659. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, J.P.; Dunne, K.; Jankaew, K. Prehistorical frequency of high-energy marine inundation events driven by typhoons in the bay of Bangkok (Thailand), interpreted from coastal carbonate boulders. Earth Surf. Process Landforms 2016, 41, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.P.; Karoro, R.; Gienko, G.A.; Wieczorek, M.; Lau, A.Y.A. Giant palaeotsunami in Kiribati: Converging evidence from geology and oral history. Isl. Arc 2021, 30, e12417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.; Ardhuin, F.; Dias, F.; Autret, R.; Beisiegel, N.; Earlie, C.S.; Herterich, J.G.; Kennedy, A.; Paris, R.; Raby, A.; et al. Systematic review shows that work done by storm waves can be misinterpreted as tsunami-related because commonly used hydrodynamic equations are flawed. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathurst, J.C. Field Measurement of Boulder Flow Drag. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1996, 122, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovere, A.; Casella, E.; Harris, D.L.; Lorscheid, T.; Nandasena, N.A.K.; Dyer, B.; Sandstrom, M.R.; Stocchi, P.; D’Andrea, W.J.; Raymo, M.E. Giant boulders and Last Interglacial storm intensity in the North Atlantic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 12144–12149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.; Yen, J.Y.; Wu, B.L.; Shih, N.W. Field observations of sediment transport across the rocky coast of east Taiwan: Impacts of extreme waves on the coastal morphology by Typhoon Soudelor. Mar. Geol. 2020, 421, 106088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganas, A.; Briole, P.; Bozionelos, G.; Barberopoulou, A.; Elias, P. et al. The 25 October 2018 Mw = 6.7 Zakynthos earthquake (Ionian Sea, Greece): A low-angle fault model based on GNSS data, relocated seismicity, small tsunami and implications for the seismic hazard in the west Hellenic Arc. J. Geodyn. 2020, 137, 101731. [CrossRef]

- 12 novembre 2019: scirocco impetuoso, marea eccezionale a Venezia e alluvioni al sud Italia con la depressione "Detlef". Available online: http://www.nimbus.it/eventi/2019/191115MareaEccezionaleVenezia.htm (accessed on 13 June 2023). (In Italian).

- Melet, A.; Buontempo, C.; Mattiuzzi, M.; Salamon, P.; Bahurel, P.; Breyiannis, G.; Burgess, S.; Crosnier, L.; Le Traon, P.Y.; Mentaschi, L.; et al. European Copernicus Services to Inform on Sea-Level Rise Adaptation: Current Status and Perspectives. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 703425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irazoqui Apecechea, M.; Melet, A.; Armaroli, C. Towards a pan-European coastal flood awareness system: Skill of extreme sea-level forecasts from the Copernicus Marine Service. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1091844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEOS Captures Tropical Cyclone-Like System “Trudy” over the Mediterranean Sea. Available online: https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.

- gov/research/science_snapshots/2020/medicane_Trudy.php. (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Segunda borrasca con nombre de la temporada. La borrasca Bernardo afectara especialmente al E de las islas Baleares. Available online: https://twitter.com/AEMET_Esp/status/1193226687611383811 (accessed on 13 June 2023). (In Spanish).

- Medicane “Trudy” (Detlef, Bernardo) makes landfall in Algeria. Available online: https://watchers.news/2019/11/12/medicane/ (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Tropical Cyclone Reports (Mediterranean Sea). Subtropical Storm Detlef (2019). Available online: http://zivipotty.hu/2019 771. 2019.

- _detlef.pdf. (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Miglietta, M.M.; Buscemi, F.; Dafis, S.; Papa, A.; Tiesi, A.; Conte, D.; Davolio, S.; Flaounas, E.; Levizzani, V.; Rotunno, R. A high-impact meso-beta vortex in the Adriatic Sea. Q. J. R. Meteorol. 2023, 149, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, L.; Bajo, M.; Barbariol, F.; Bastianini, M.; Benetazzo, A.; Bertotti, L.; Chiggiato, J.; Ferrarin, C.; Trincardi, F.; Umgiesser, G. The 2019 flooding of Venice and its implications for future predictions. Oceanography 2020, 33, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Davis, E. An intensity scale for Atlantic coast northeast storms. J. Coast. Res. 1992, 8, 840–853. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, E.T.; Trejo-Rangel, M.A.; Salles, P.; Appendini, C.M.; Lopez-Gonzalez, J.; Torres-Freyermuth, A. Storm characterization and coastal hazards in the Yucatan Peninsula. J. Coast. Res. 2013, 65, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfuso, G.; Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Cortes-Useche, C.; Iglesias Castillo, B.; Gracia, F.J. Characterization of storm events along the Gulf of Cadiz (eastern central Atlantic Ocean). Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 3690–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martzikos, N.; Afentoulis, V.; Tsoukala, V. Storm clustering and classification for the port of Rethymno in Greece. Water Util. J. 2018, 20, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Noji, M.; Imamura, F.; Shuto, N. Numerical simulation of movement of large rocks transported by tsunamis. In Proceedings of the IUGG/IOC International Tsunami Symposium, Wakayama, Japan, 23–27 August 1993; pp. 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Imamura, F.; Goto, K.; Ohkubo, S. A numerical model of the transport of a boulder by tsunami. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, C01008 (12 pp.). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.B.; Mori, N.; Zhang, Y.; Yasuda, T.; Chen, S.; Tajima, Y.; Pecor, W.; Toride, K. Observations and Modeling of Coastal Boulder Transport and Loading During Super Typhoon Haiyan. Coast. Eng. J. 2016, 58, 1640004-1–1640004-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwing, F.B.; Blanton, J.O. The use of land and sea based wind data in a simple circulation model. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1984, 14, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.R.; Rees, E.F.; Thomas, T. Winds, sea levels and NAO influences: an evaluation. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2013, 100, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.A.; Gelfenbaum, G.; Jaffe, B.E. Physical criteria for distinguishing sandy tsunami and storm deposits using modern examples. Sediment. Geol. 2007, 200, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S.M.; Engel, M.; Brill, D.; Cuadra, C.; Lagmay, A.M.F.; Santiago, J.; Suarez, J.K.; Reyes, M.; Bruckner, H. Block and boulder transport in Eastern Samar (Philippines) during Supertyphoon Haiyan. Earth Surf. Dynamic. 2015, 3, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.P.; Goff, J. Strongly aligned coastal boulders on Ko Larn Island (Thailand): A proxy for past typhoon-driven high-energy wave events in the Bay of Bangkok. Geogr. Res. 2019, 57, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.P.; Lau, A.Y.A. Magnitudes of nearshore waves generated by Tropical Cyclone Winston, the strongest landfalling cyclone in South Pacific records. Unprecedented or unremarkable? Sediment. Geol. 2018, 364, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herterich, J.G.; Dias, F. Potential flow over a submerged rectangular obstacle: Consequences for initiation of boulder motion. Eur. J. Appl. Math. 2020, 31, 646–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site Name | ID Code | Boulders | No. of TD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Caterina | SC | 2 | 1 |

| Pilella | PIL | 14 | 11 |

| Posto Rosso | RO | 16 | 10 |

| Torre San Giovanni | SG | 6 | 3 |

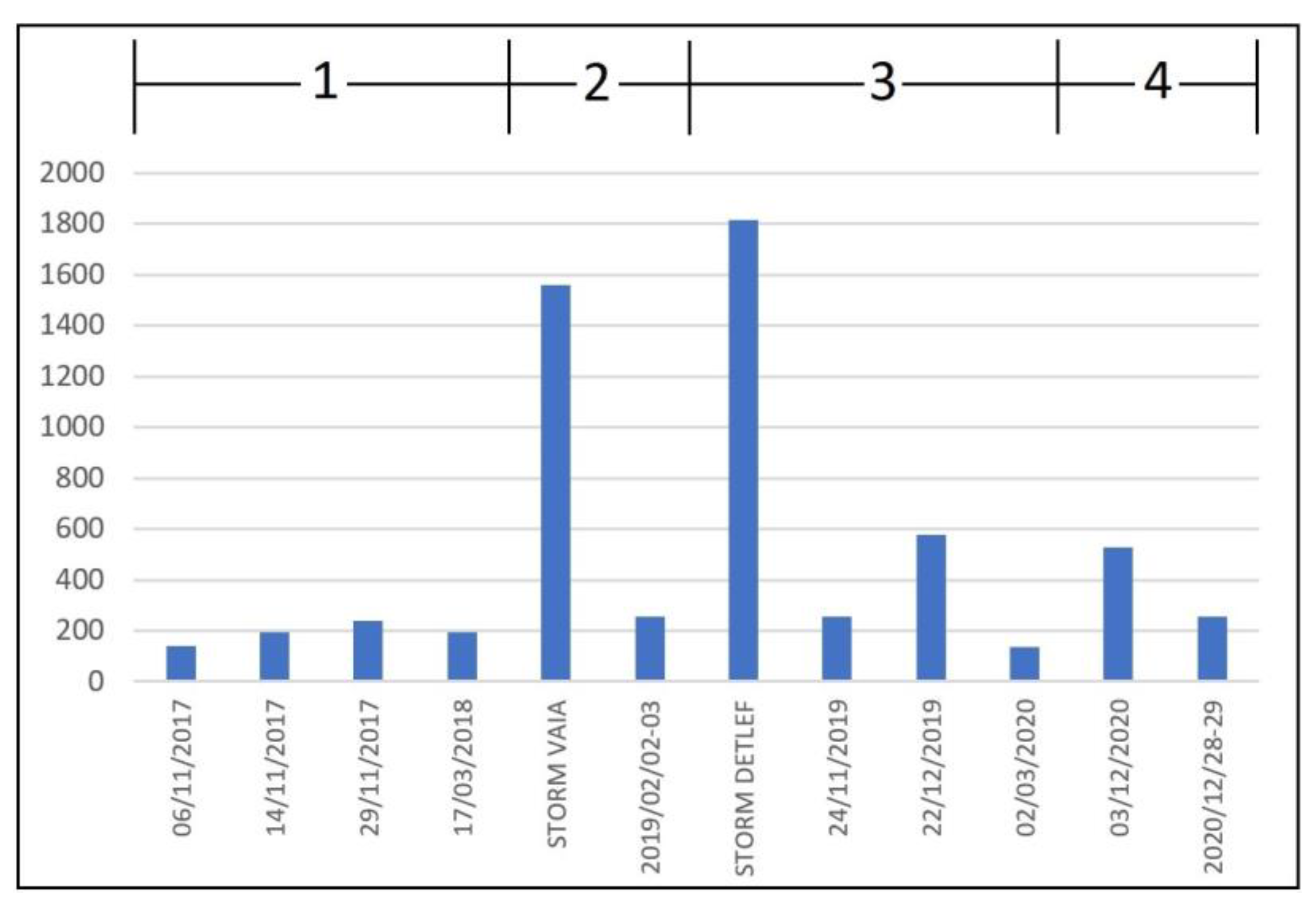

| Days | R [h] | F [km] | U [m/s] | H0 [m] | Sea State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017/11/06 | 12 | 600 | 14-16 | 3.4 | 5, rough |

| 2017/11/14 | 12 | 800 | 16-18 | 4.0 | 5, rough |

| 2017/11/29 | 15 | 900 | 14-16 | 4.0 | 5, rough |

| 2018/03/17 | 12 | 700 | 16-18 | 4.0 | 5, rough |

| 2018/10/28-291 | 48 | 700 | 12-14 | 5.7 | 6, very rough |

| 2019/02/02-03 | 12 | 800 | 18-20 | 4.6 | 6, very rough |

| 2019/11/12-132 | 24 | 900 | 20-22 | 8.7 | 7, high |

| 2019/11/24 | 12 | 800 | 18-20 | 4.6 | 6, very rough |

| 2019/12/22 | 24 | 400 | 14-16 | 4.9 | 6, very rough |

| 2020/03/02 | 12 | 600 | 12-14 | 3.4 | 5, rough |

| 2020/12/03 | 18 | 600 | 16-18 | 5.4 | 6, very rough |

| 2020/12/28-29 | 12 | 600 | 18-20 | 4.6 | 6, very rough |

| Boulder ID | Size (af x bf x cf) | xi | TD | PTS | MT | V | Eq. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRq1 | 2.7 x 1.4 x 0.4 | 1.9 | 11.7 | SA | ST | 5.9 | (4) |

| SIg1 | 1.7 x 1.5 x 0.5 | 9 | 2.4 | SA | OV | 4.4 | (6) |

| SCb | 1.8 x 1.6 x 0.7 | 18.8 | 15.4 | SA | OV | 5.4 | (6) |

| PIh1 | 3.1 x 2.2 x 0.4 | 1.7 | 14.3 | SA | ST | 5.9 | (4) |

| MAa1 | 3.4 x 2.1 x 0.5 | 0.6 | 4.4 | SA | SL | 2.8 | (5) |

| SUa1 | 5.4 x 4.6 x 1.9 | 0 | 8.9 | SB | SL | 4.4 | (5) |

| CAd1 | 2.6 x 2.4 x 0.9 | 3.9 | 2.5 | SA | OV | 5.6 | (6) |

| PILj | 3.0 x 1.8 x 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.6 | SB | SL | 2.7 | (5) |

| ROd | 2.4 x 1.5 x 0.7 | 10.4 | 4.5 | SA | OV | 4.3 | (6) |

| ROn | 2.8 x 2.1 x 0.5 | 4.2 | 17.1 | SA | ST | 6.6 | (4) |

| SGe | 2.2 x 1.7 x 0.7 | 13.8 | 6.5 | SA | ST | 7.8 | (4) |

| CIc1 | 2.2 x 1.4 x 0.5 | 5.2 | 3.3 | SA | ST | 8.1 | (4) |

| CW season | No. of displacements | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | July 2017-July 2018 | 2017-2018 | 0 |

| 2 | July 2018-July 2019 | 2018-2019 | 1 |

| 3 | July 2019-June 2020 | 2019-2020 | 110 |

| 4 | June 2020-September 2021 | 2020-2021 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).