Submitted:

25 October 2023

Posted:

26 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Characterization

2.2. Farmer volunteers and ground field mapping of producer fields

2.2. Rice fields mapping

2.3. UAS remote sensing and image processing

2.4. Assessment of crop health areas and rice grain determination

2.5. Soil characterization

2.6. Yield estimation and field yield mapping based on vegetation indices

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Soil characterization

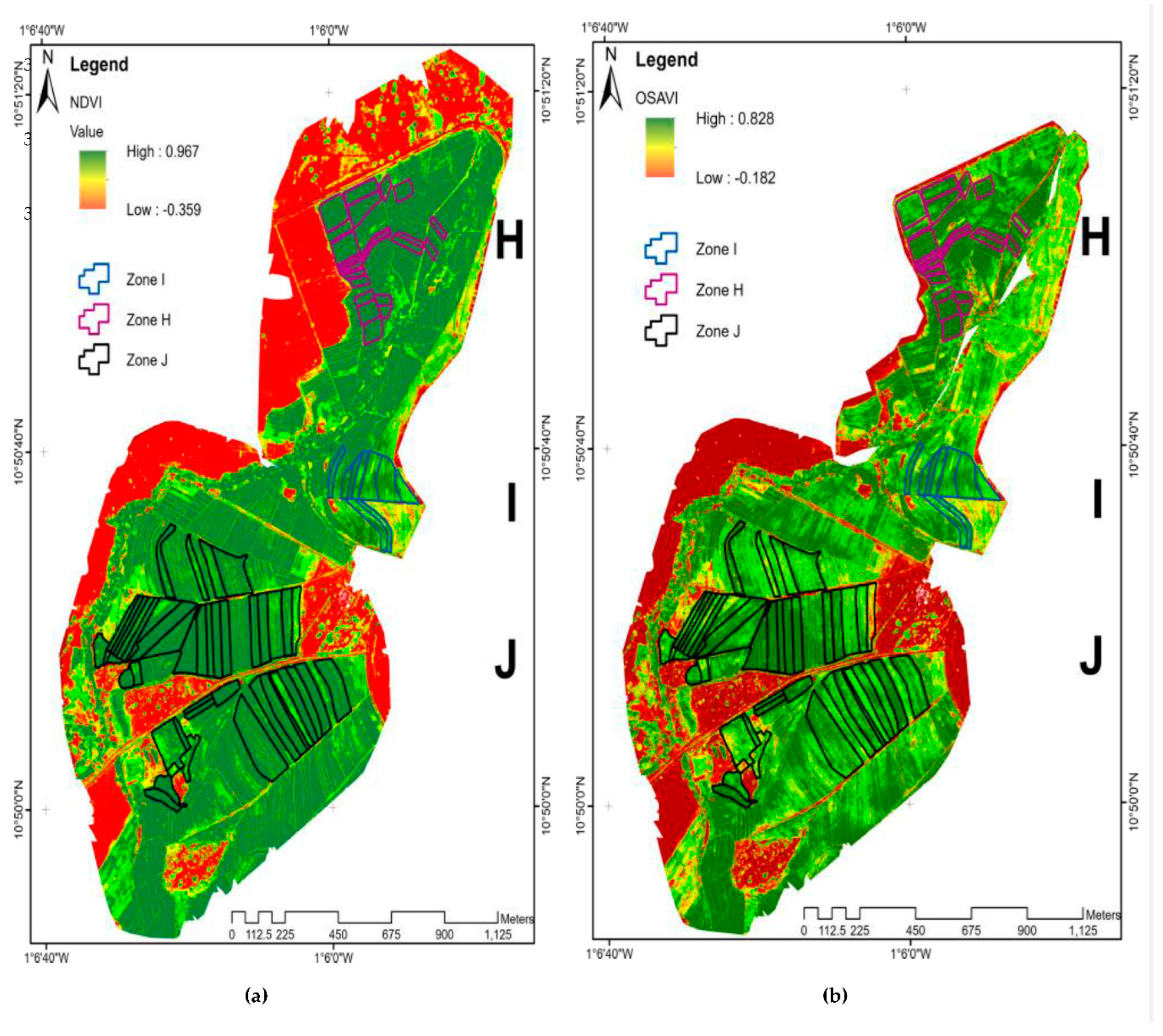

3.2. Orthomosaics and Crop Health Delineation

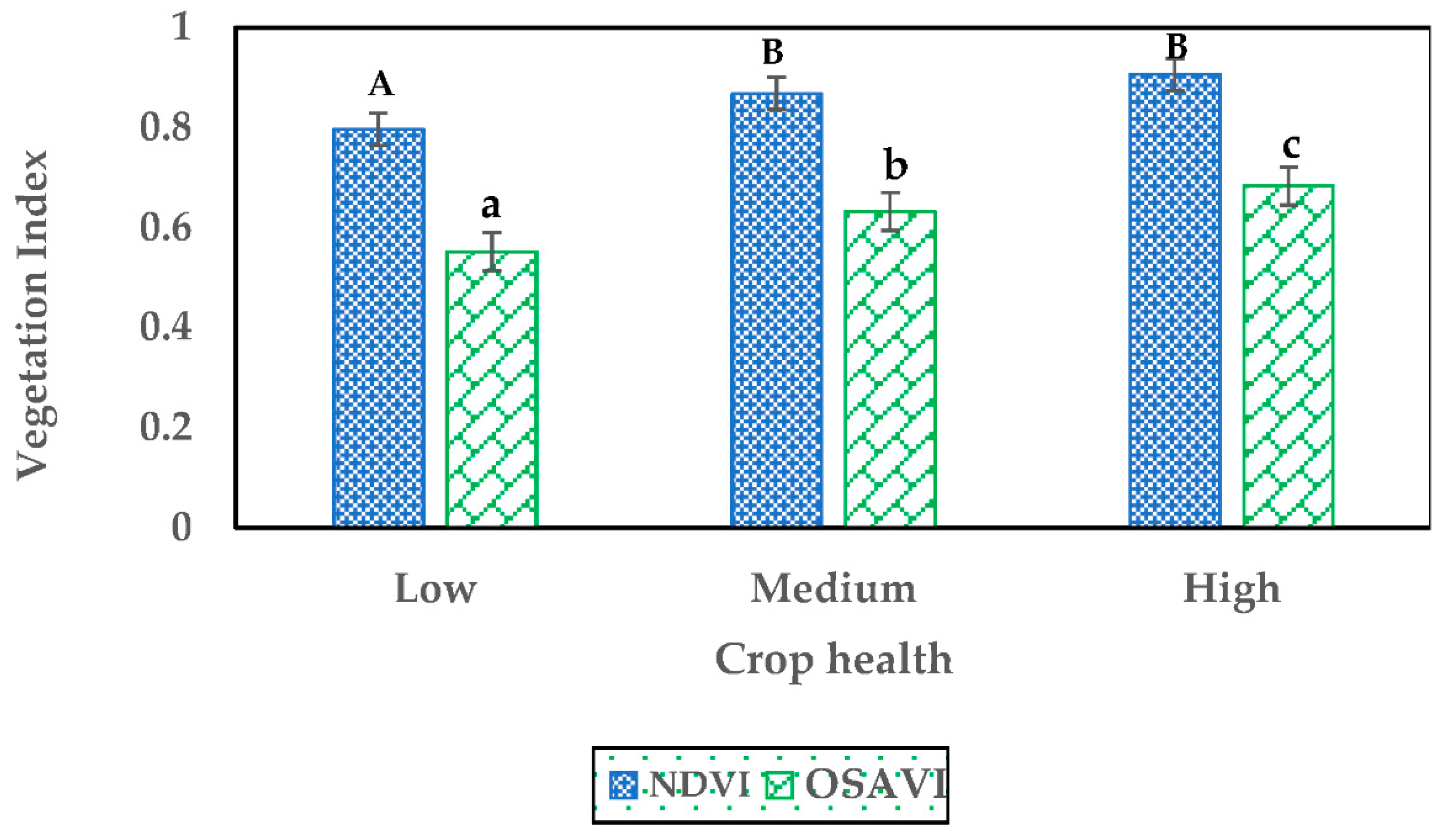

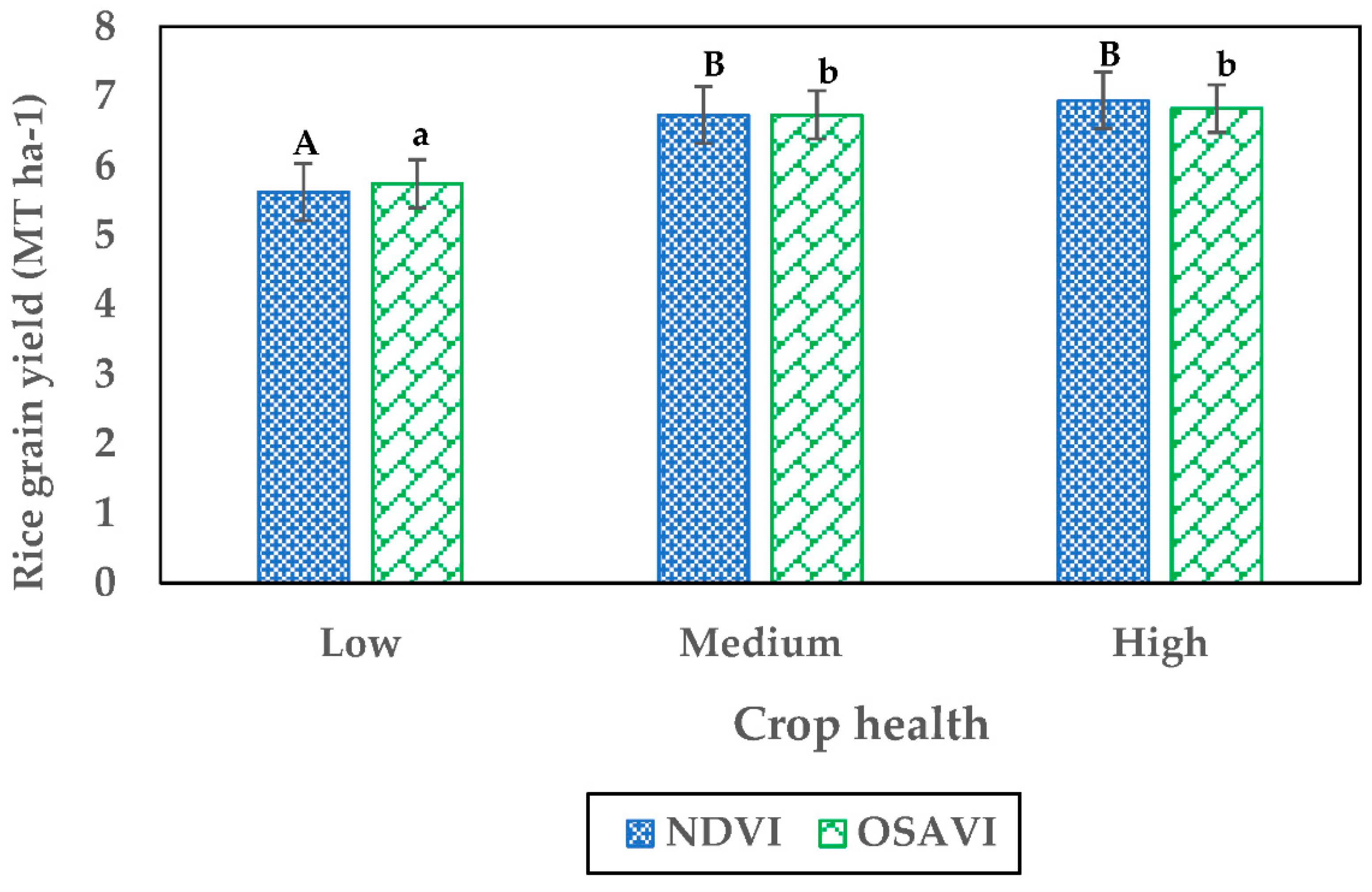

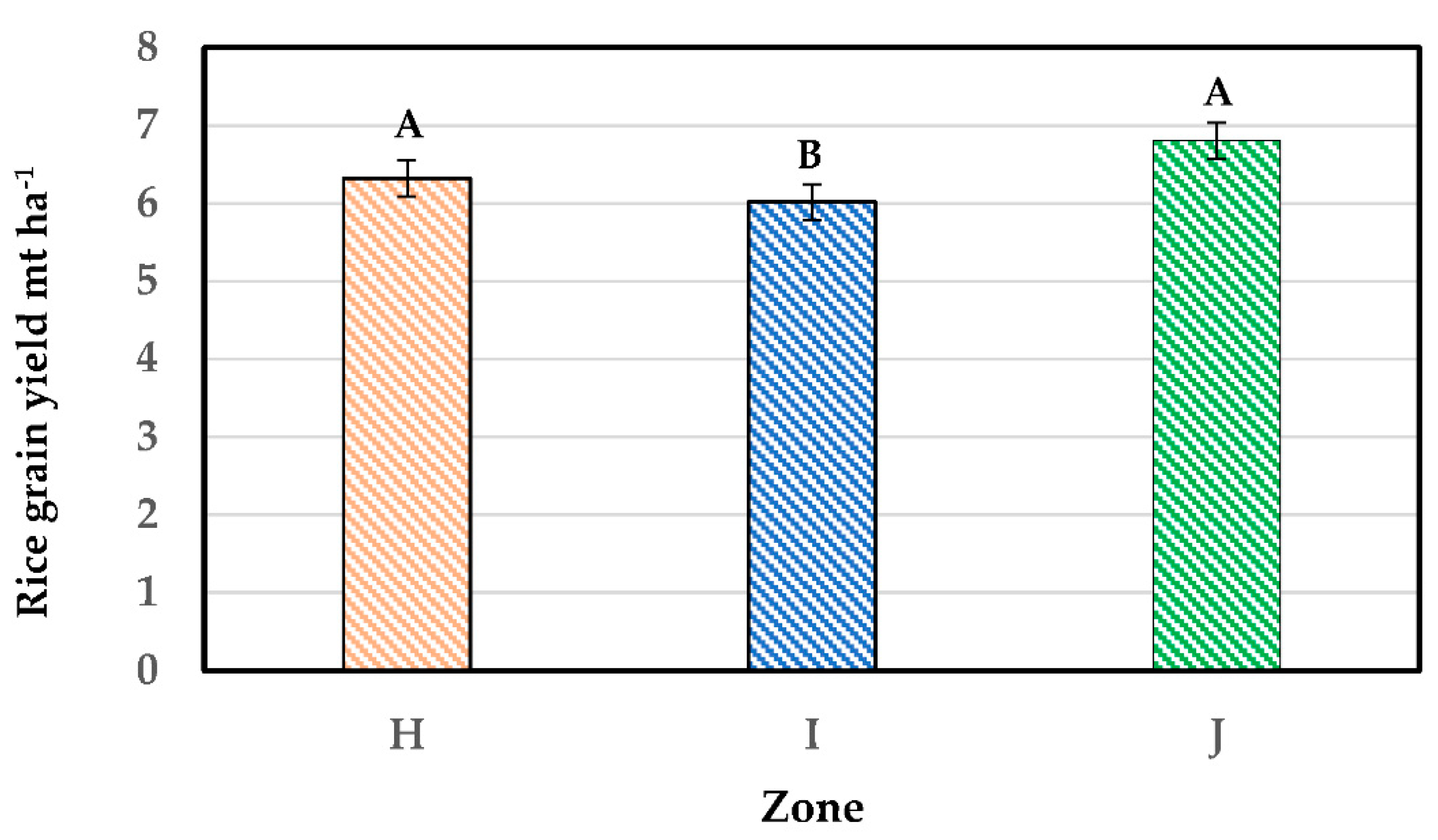

3.3. Midseason crop health and rice grain yield

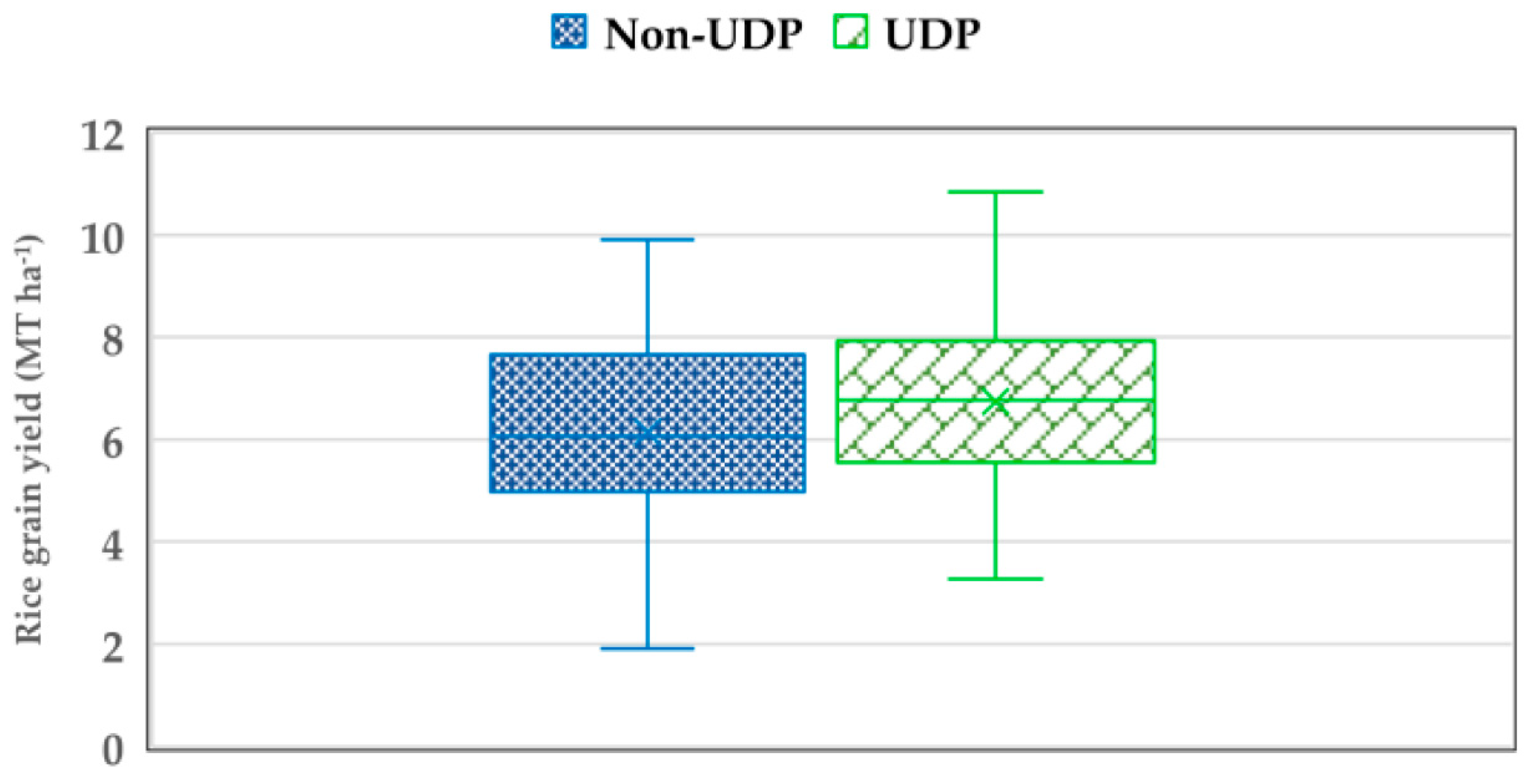

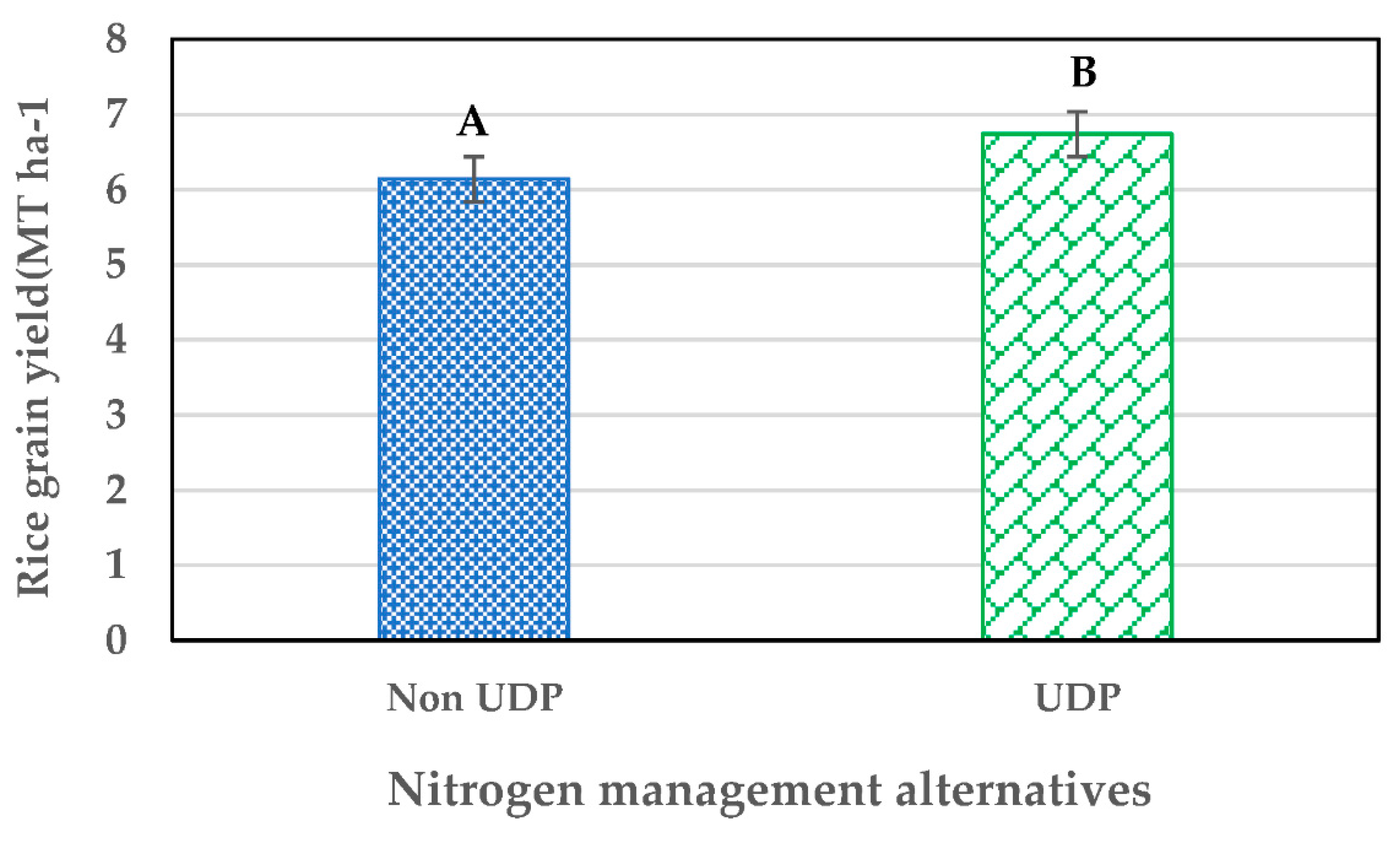

3.4. Nitrogen management systems and rice grain yields

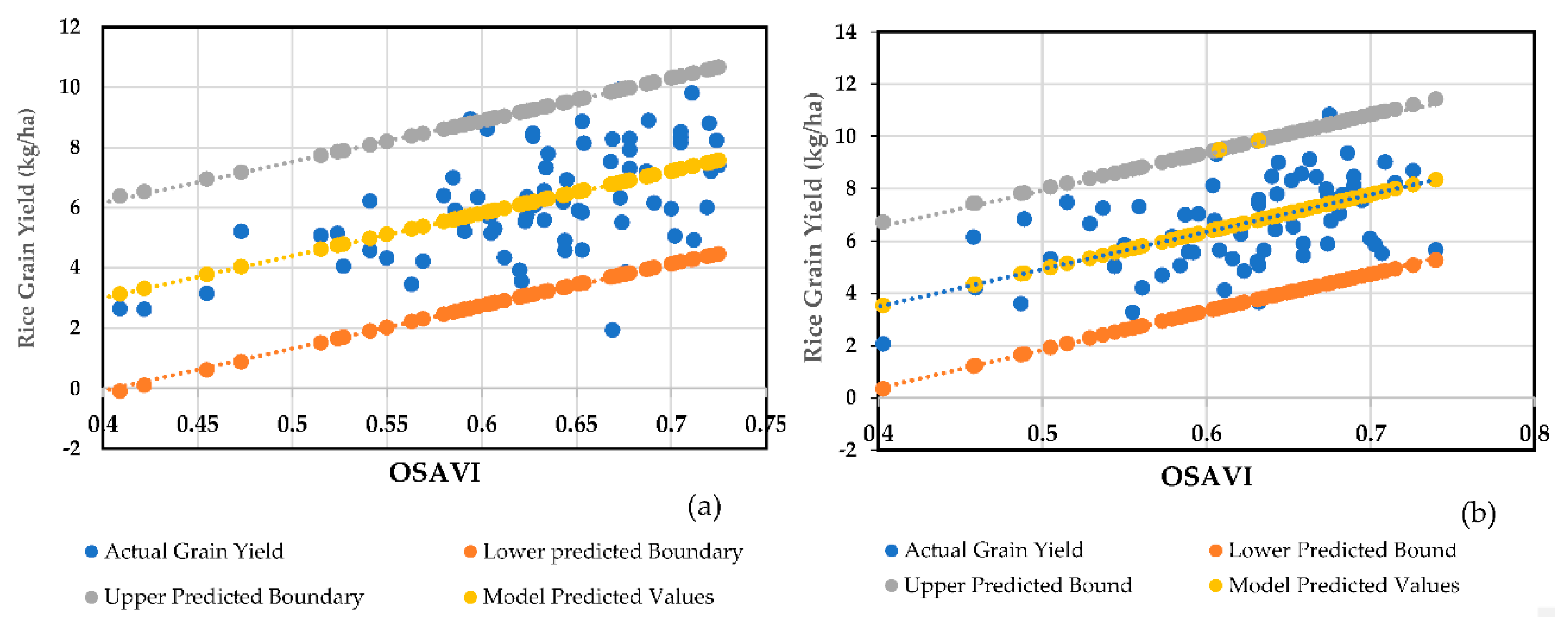

3.5. Extrapolation of yields from plot to farmer field-levels

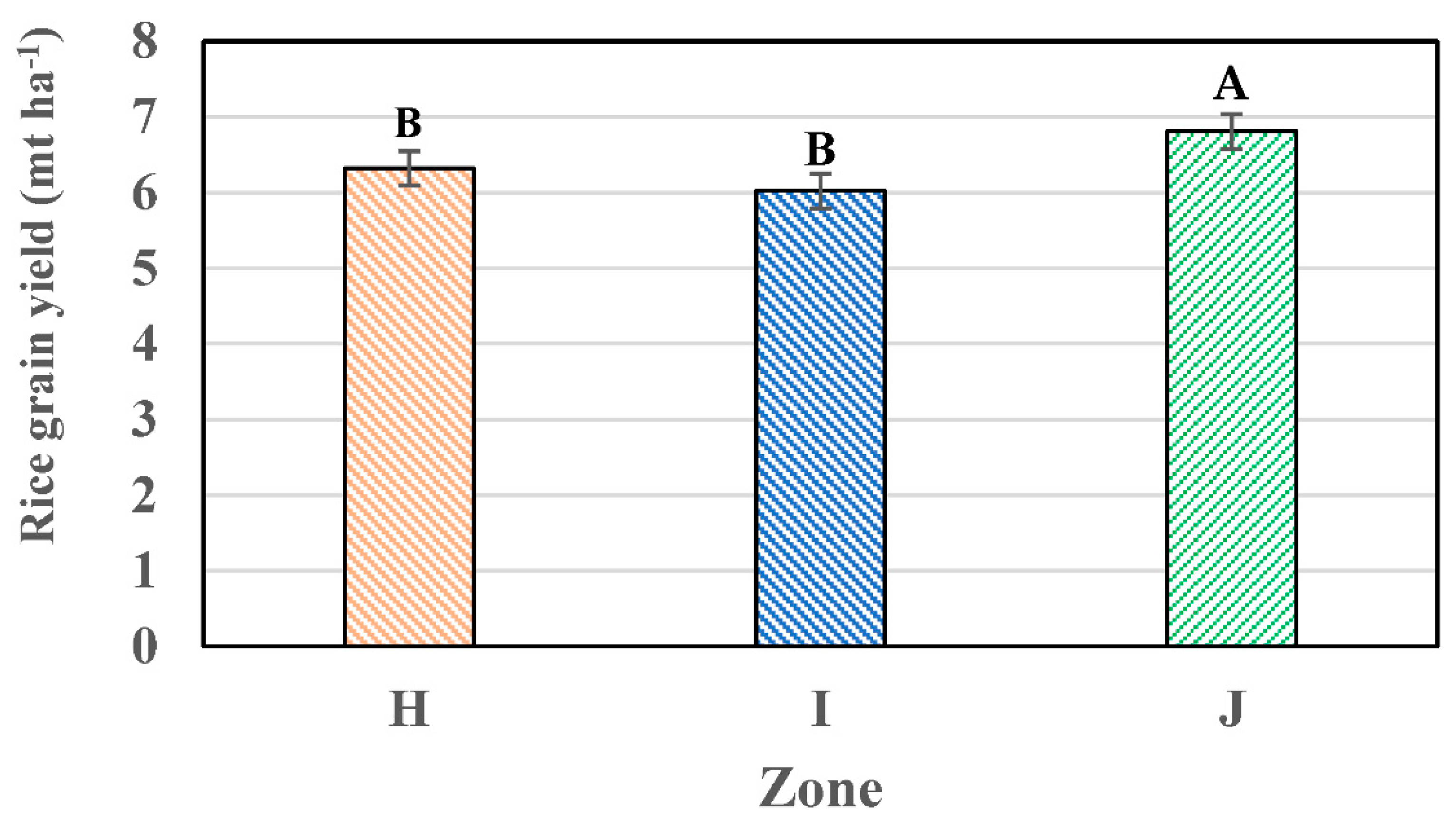

3.7. Comparison of rice yields at plot and field scales

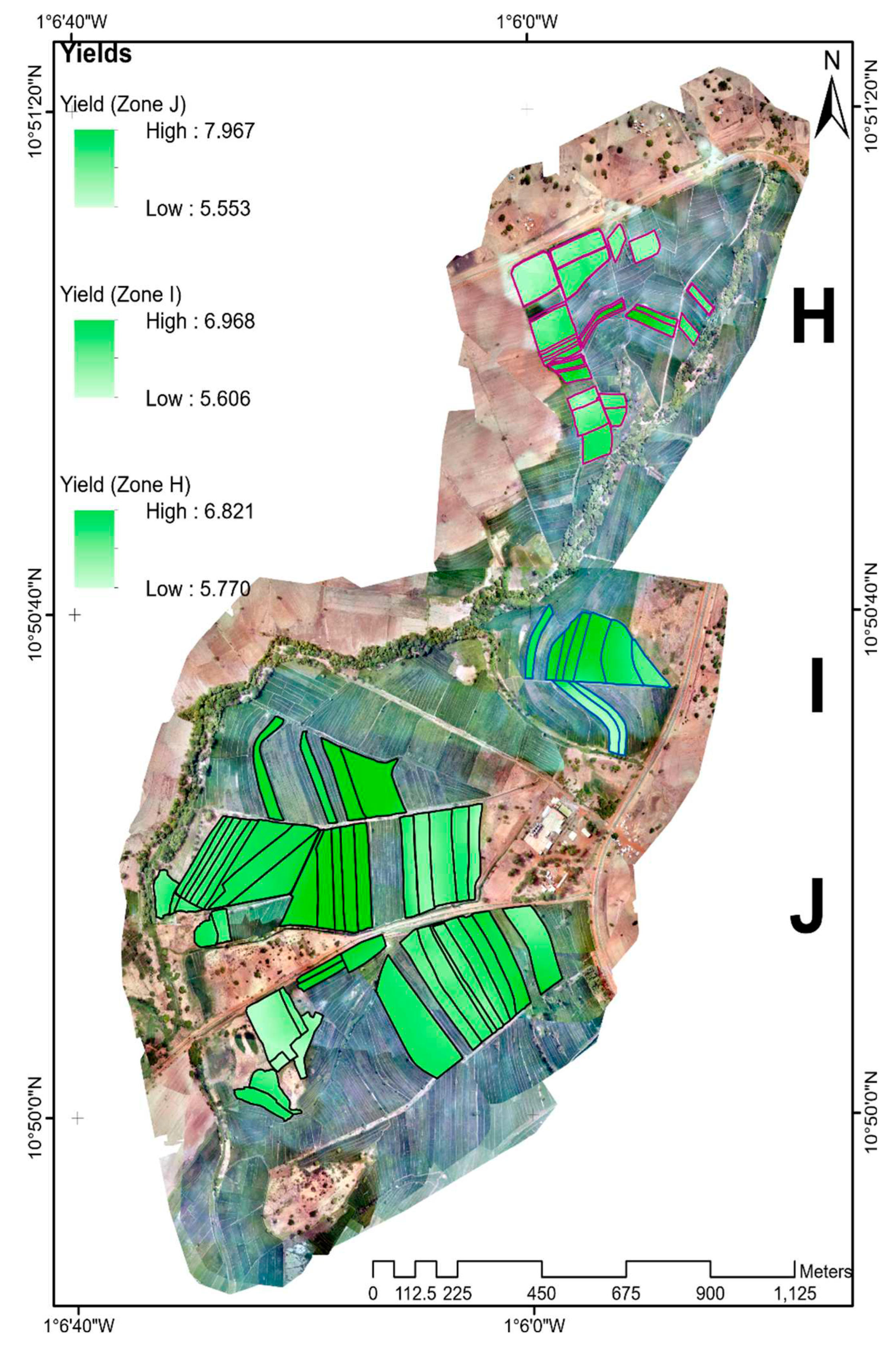

3.8. Rice grain yield mapping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MiDA (Millennium Development Authority) (2010). Investment opportunity in Ghana: Maize, Rice, and Soybean. Accra, Ghana: MiDA.

- Osei-Asare, Y. (2010). Mapping of poverty reduction strategies and policies related to rice development in Ghana. Nairobi, Kenya: Coalition for African Rice Development (CARD).

- Bannor, R.K. Long-run and short-run causality of rice consumption by urbanization and income growth in Ghana. ACADEMICIA: An International Multidisciplinary Research Journal 2015, 5, 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Food Agriculture (MoFA, 2021). Agriculture in Ghana: Facts and Figures (2012). Statistics, Research and Information Directorate (SRID) (pp. 1– 45). Accra.

- Denkyirah, E.K.; Aziz, A.A.; Denkyirah, E.K.; Nketiah, O.O.; Okoffo, E.D. Access to credit and constraint analysis: the case of smallholder rice farmers in Ghana. Journal of Agricultural Studies 2016, 4, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, V.; Sie, M.; Hijmans, R.J.; Otsuka, K. Increasing Rice Production in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and opportunities. Advances in Agronomy 2007, 94, 55–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaf, K.; and Emmanuel, D. (2009). Global food security response: Ghana rice study. Attachment I to the Global Food Security Response West African Rice Value Chain Analysis.

- Aker, J. C.; Block, S.; Ramachandran, V.; and Timmer, C. P. (2010). West African experience with the world rice crisis, 2007-2008. The rice crisis: markets, policies and food security, 143-162.

- Ladha, J.K.; Pathak, H.; Krupnick, T.J.; Six, J.; van Kessel, C. Efficiency of fertilizer nitrogen in cereal production: retrospect and prospects. Adv. Agron. 2005, 87, 85–156. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.M.; Karim, R.; Ladha, J. Integrating best management practices for rice with farmers’ crop management techniques: A potential option for minimizing rice yield gap. Field Crops Research 2013, 144, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.M.; Brandt, K.K.; Sørensen, J.; Hung, N.N.; Hach CVan Tan, P.S.; Dalsgaard, T. Effects of alternating wetting and drying versus continuous flooding on fertilizer nitrogen fate in rice fields in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2012, 47, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFDC (International Fertilizer Development Center). 2013. Fertilizer deep placement. IFDC solutions. IFDC, Muscle Shoals, AL, 6.http://issuu.com/ifdcinfo/docs/fdp_8pg_final_web?e=1773260/1756718.

- Savant, N. K.; and Stangel, P. J. (1990). Deep placement of urea supergranules in transplanted rice: Principles and practices.

- Rochette, P.; Angers, D.A.; Chantigny, M.H.; Gasser, M.-O.; MacDonald, J.D.; Pelster, D.E.; Bertrand, N. Ammonia Volatilization and Nitrogen Retention: How Deep to Incorporate Urea. Journal of Environmental Quality 2013, 42, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, M.; Zeng, K.; Yin, B. Urea deep placement for minimizing NH3 loss in an intensive rice cropping system. Field Crops Research 2018, 218, 254–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Barmon, B.K. Exploring the potential to improve energy saving and energy efficiency using fertilizer deep placement strategy in modern rice production in Bangladesh. Energy Efficiency 2015, 8, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasandaran, E.; Gultom, B.; Adiningsih, J.S.; Apsari, H.; Rochayati, S.R. Government policy support for technology promotion and adoption: a case study of urea tablet technology in Indonesia. Nutrient cycling in Agroecosystems 1998, 53, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbule, A.V.; Purkar, J.K.; Jogdande, N.D. Management of nitrogen for rainfed transplanted rice. Crop Research-Hisar 2002, 23, 440–445. [Google Scholar]

- Shaibu aanni, A.; Adzawla, W. Effect of Urea Deep Placement Technology Adoption on the Production Frontier: Evidence from Irrigation Rice Farmers in the Northern Region of Ghana. International Journal of Biological, Biomolecular, Agricultural, Food, and Biotechnological Engineering 2017, 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liverpool-Tasie LS, O.; Adjognon, S.; Kuku-Shittu, O. Productivity effects of sustainable intensification: The case of Urea deep placement for rice production in Niger State, Nigeria. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2015, 10, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mosleh, M.K.; Hassan, Q.K.; Chowdhury, E.H. Development of a remote sensing-based rice yield forecasting model. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2016, 14, e0907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, J.V. Implementing Precision Agriculture in the 21st Century. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 2000, 76, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Chang, K.W.; Chen, R.K.; Lo, J.C.; Shen, Y. Large-area rice yield forecasting using satellite imageries. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2010, 12, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamori, K.; Ichikawa, D.; Oguri, N. Estimation of rice growth status, protein content and yield prediction using multi-satellite data. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Fort Worth, TX, USA; 2017; pp. 5089–5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuarsa, I.W.; Nishio, F.; Hongo, C. Rice yield estimation using Landsat ETM+ data and field observation. Journal of Agricultural Science 2012, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomiadis, E.; Dercas, N.; Dalezios, N.R.; Spyropoulos, N.V. The role of spatial and spectral resolution on the effectiveness of satellite-based vegetation indices. Proc. SPIE 9998, Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology XVIII, 99981L (25 October 2016). [CrossRef]

- Mulla, D.J. Twenty-five years of remote sensing in precision agriculture: Key advances and remaining knowledge gaps. Biosystems Engineering 2013, 4, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzar, M.; Sheffield, K.; Whitfield, D.; O’Connell, M.; McAllister, A. Comparing inter-sensor NDVI for the analysis of horticulture crops in south-eastern Australia. American Journal of Remote Sensing 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Rahimi-Eichi, V.; Haefele, S.; Garnett, T.; Miklavcic, S.J. Estimation of vegetation indices for high-throughput phenotyping of wheat using aerial imaging. Plant methods 2018, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. H.; Kovacs, J.M. The Application of Small Unmanned Aerial Systems for Precision Agriculture: A Review. Precision Agriculture 2012, 13, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.C.; Merz, T.; Chan, A.; Jakeway, P.; Hrabar, S.; Dreccer, M.F.; Jimenez-Berni, J. Pheno-copter: a low-altitude, autonomous, remote-sensing robotic helicopter for high-throughput field-based phenotyping. Agronomy 2014, 4, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, D.W.; Brown, R.B. P.A.—Precision Agriculture. Remote-Sensing Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 2001, 78, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmann, M.; Giebel, A.; Gleiniger, F.; Pflanz, M.; Lentschke, J.; Dammer, K.H. Monitoring agronomic parameters of winter wheat crops with low-cost UAV imagery. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmer, T.M.; Schepers, J.S.; Varvel, G.E.; Walter-Shea, E.A. Nitrogen deficiency detection using reflected shortwave radiation from irrigated corn canopies. Agron. J. 1996, 88, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.L.; Solie, J.B.; Raun, W.R.; Whitney, R.W.; Taylor, S.L.; Ringer, J.D. Use of spectral radiance for correcting in-season fertilizer nitrogen deficiencies in winter wheat. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1996, 39, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of Soil-adjusted vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107 http://. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 37. SenseFly. (2016). eBee:senseFly S.A. Retrieved From https://www.sensefly.com/drone/ebee-mapping-drone/.

- Mikhail, E.M.; Bethel, J.S.; McGlone, J.C. Introduction to modern photogrammetry. New York.

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. (1974). Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. NASA special publication, 351-30.

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of soil-adjusted vegetation indices. Remote sensing of environment 1996, 55, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.F.; Hallberg, G.R.; Fenton, T.S. Particle size analysis by the Iowa State University Soil Survey Lab. Standard procedures for evaluation of quaternary materials in Iowa. Iowa Geological Survey, Iowa City, 1978, 61-74.

- Combs, S.M.; Nathan, M.V. Soil organic matter. p. 53–58. In. Comun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1998, 22, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Recommended chemical soil test procedures for the north-central Sikora, L.J.; and D.E. Stott. 1996. Soil organic carbon and nitrogen. P. 157–168. In J.W. Doran and A.J. Jones (ed.) Methods for as-region. North Central Regional Res. Publ. No. 221 (revised). Mis sessing soil quality. SSSA Spec. Publ. 49. SSSA, Madison, Missouri Agric. Exp. Sta. SB 1001, Columbia, MO.

- Bray, R.H.; Kurtz, L.T. Determination of Total Organic and Available Forms of Phosphorus in Soils. Soil Science 1945, 59, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warncke, D.; Brown, J. R. Potassium and other basic cations. Recommended chemical soil test procedures for the North Central Region 1998, 1001, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, G.F. The data model concept in statistical mapping. Int. Yearb. Cartogr. 1967, 7, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, G.F.; Caspall, F.C. Error on choroplethic maps: definition, measurement, reduction. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 1971, 61, 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute Inc. 2018. SAS/STAT® 15.1 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc Statistix 9 2019 Tallahassee FL. USA.

- Konja, T.F.; Mabe, F.N.; Alhassan, H. Technical and resource-use-efficiency among smallholder rice farmers in Northern Ghana. Cogent Food& Agriculture 2019, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bationo, A.; Fening, J.O.; Kwaw, A. Assessment of soil fertility status and integrated soil fertility management in Ghana. In: Improving the profitability, sustainability, and efficiency of nutrients through site-specific fertilizer recommendations in West Africa agroecosystems; Springer, Cham. 2018; pp. 93-138. [CrossRef]

- Asrar, G.; Fuchs, M.; Kanemasu, E.T.; Hatfield, J.L. Estimating absorbed photosynthetic radiation and leaf area index from spectral reflectance in wheat. Agron Journal 1984, 76, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, T. The use of NOAA-AVHRR NDVI data to assess herbage production in the arid rangelands of Central Australia. Int. J Remote Sens 1995, 16, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, T.H.; Lundy, M.E.; Linquist, B.A. Comparative Sensitivity of Vegetation Indices Measured via Proximal and Aerial Sensors for Assessing N Status and Predicting Grain Yield in Rice Cropping Systems. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wheeler, D.; Bell, J.; Wilding, L. Assessment of soil spatial variability at multiple scales. Ecological Modelling. 2005, 182, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyin-Birikorang, S.; Tindjina, I.; Boubakary, C.; Dogbe, W. Resilient rice fertilization strategy for submergence In the Savanna agroecological zones of Northern Ghana. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2020, 43, 965–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazid Miah, M.A.; Gaihre, Y.K.; Hunter, G.; Singh, U.; Hossain, S.A. Fertilizer deep placement increases rice production: evidence from farmers’ fields in southern Bangladesh. Agronomy Journal 2016, 108, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Gurmani, A.R.; Gurmani, A.H.; Zia, M. Effect of phosphorus application on wheat and rice yield the rice-wheat system. Sarhad J. Agric. 2007, 23, 851. [Google Scholar]

| Non-UDP | UDP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone | Number of volunteers | Total farm size (ha) | Number of volunteers | Total farm size (ha) |

| H | 4 | 1.5 | 9 | 3.2 |

| I | 5 | 3.2 | 4 | 1.6 |

| J | 16 | 15.7 | 12 | 8.9 |

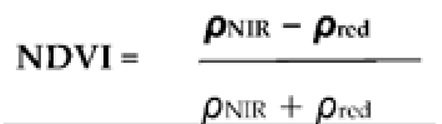

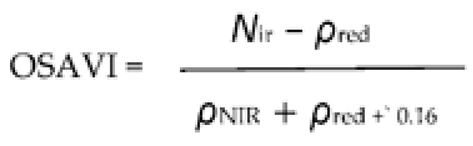

| Vegetation Index | Equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Normal difference vegetation index (NDVI) |  |

[40] |

| Optimized Soil Adjustment Vegetation Index (OSAVI) |  |

[41] |

| Zone | Sand | Silt | Clay | pH | Bray1 P | OM | T N | CEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | mg/kg-1 % | cmol(+) kg-1 | ||||||

| Zones | ||||||||

| H | 54.7b | 27a | 18.76a | 5.4a | 5.08b | 1.94a | 0.11a | 18.38a |

| I | 70.6a | 16.7b | 13.1b | 5.7a | 2.32c | 1.16b | 0.07b | 7.48b |

| J | 56.7b | 28.7a | 14.6b | 5.9a | 6.58a | 1.23b | 0.10b | 7.94b |

| Non-UDP | 55.1a | 27.7a | 17.3a | 5.6a | 4.35a | 1.56a | 0.09a | 10.22a |

| UDP | 65.2b | 21.7b | 13.6b | 5.5a | 5.16a | 1.30a | 0.08a | 8.18b |

| Pearson’s correlation test | ||||||||

| Sand | 1 | -0.844** | -0.717** | -0.047* | 0.249 | -0.489** | -0.419* | -0.614** |

| Silt | 1 | 0.370* | -0.004 | -0.117 | 0.307* | 0.317 | 0.465** | |

| Clay | 1 | 0.136 | -0.451** | 0.677** | 0.414** | 0.829** | ||

| pH | 1 | 0.102 | -0.124 | -0.218 | 0.079 | |||

| Bray1 P | 1 | -0.177 | -0.117 | -0.417** | ||||

| OM | 1 | 0.668** | 0.733** | |||||

| TN | 1 | 0.501** | ||||||

| Statistic | Plot scale | Field-scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-UDP | UDP | Non-UDP | UDP | |

| Average grain yield (mt ha-1) | 6.15 | 6.84** | 6.08 | 6.92** |

| Range | 1.92 – 9.91 | 3.27 – 10.84 | 5.50 – 7.51 | 5.63 – 8.00 |

| Median yield (mt ha-1) | 6.14 | 6.77 | 6.08 | 6.92 |

| Middle 50% yield ((mt ha-1) | 4.94 | 7.71 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| Coefficient of variation | 29 | 24.5 | 9.83 | 9.86 |

| Non-UDP fields | UDP fields | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fields | Field size (ha) | Average grain yield (mt ha-1) | Total grain yield (mt) | Field size (ha) | Average grain yield (mt ha-1) | Total grain yield (mt) | Total zone production (mt) |

| H | 4.30 | 5.95a | 25.59 | 2.70 | 6.7ab | 18.12 | 43.71 |

| I | 2.53 | 5.82a | 14.72 | 4.70 | 6.22b | 29.23 | 43.95 |

| J | 15.52 | 6.42a | 99.64 | 23.87 | 7.17a | 171.15 | 270.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).