1. Introduction

The sacroiliac (SI) joint connects the spine to the pelvis. Dysfunction of this joint can lead to debilitating pain and significantly impact a patient's quality of life [

1]

. SI dysfunction can be caused by degeneration, inflammation, trauma, pregnancy, lumbar fusions, or hypermobility syndromes. Surgical intervention can be considered when conservative treatment, such as corticosteroid injections and physical/manual therapy, give no sufficient response [

2]

. The most common procedure for SI dysfunction involves stabilization of the SI joint, also known as minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (SIJF). This results in a reduction of joint motion and thereby reduction of pain. In this study three cannulated triangular titanium implants are used for SIJF (iFuse Implant System, SI-Bone, Santa Clara, United States).

Despite the increasing evidence of effectiveness, some controversy exists in using interventional procedures for SIJ pain [

3]. This may be due to the fact that SI joint dysfunction can be challenging to diagnose because the symptoms can mimic those of other conditions, such as herniated discs or hip problems [

2,

4], or due to mixed results from previously used open surgery techniques [

5,

6].

To perform a SIJF, first the surgeon predetermines the implant positions using guide pins. These pins are placed freehandedly through the SI joint using 2D lateral fluoroscopic guidance. The entry point for the guide pins will be selected based on the surgeon's experience and certain landmarks visible on a lateral fluoroscopic image. A safe trajectory needs to be confirmed in inlet and outlet views, and the guide pins will be inserted to an appropriate depth. Subsequently, the implants will be placed over the guide pins, and the guide pins will be removed. Placing the implants to an appropriate depth without damaging surrounding critical structures can be challenging due to the anatomical variations among patients[

7,

8,

9,

10], poor visibility on intraoperative imaging, and lacking 3D spatial information. Damaging structures, including the neural foramina, the sacral canal, or nerves (L4, L5 & obturator nerves), can result in major complications, such as nerve impingement resulting in radiating pain, numbness, or palsy [

11]

. When the trajectory of an implant seems unsafe in an inlet or outlet view (for an example of the views see

Figure 1), the surgeon has to switch back to a lateral view and reposition the guide pin. This can be inefficient, resulting in an extended duration of surgery and increased radiation exposure. Implants sometimes loosen over time, which is another complication that can occur and result in persistent or reoccurring pain after SIJF [

3,

12]

. More bone-implant contact, the use of more stable implant configurations, and the use of three implants instead of two can reduce the chance of implant loosening [

12,

13]

.

To overcome these challenges, navigation-guided techniques can be used [

14,

15]

. These techniques supplement intraoperative imaging of the anatomy and therefore allow for optimal and safe implant positioning. However, these navigation-guided techniques are not commonly available. They are expensive and do not necessarily decrease the duration of the surgery [

16,

17]

. Therefore, another more cost-effective and widely available alternative is desirable.

A suitable method may be virtual surgical planning (VSP). VSP methods are becoming widely adopted as part of standard care as it can result in superior outcome compared to conventional treatment without the use of VSP [

18,

19,

20,

21]

. In SIJF, the lack of 3D spatial information in the intraoperative fluoroscopic images can be overcome by displaying a VSP including 3D anatomical models and simulated fluoroscopic images, both derived from pre-operative CT data. Others have described a method using simulated fluoroscopic images to superimpose the neural foramina on fluoroscopic images [

22] and VSP without actual implants to evaluate the technical variation in SIJF due to varying sacral morphologies in cadaveric CT data [

10]. However, a combination of these techniques has never been described nor introduced in clinical practice to treat SI dysfunction.

Using VSP, the implants can be virtually placed in an optimal patient-specific implant configuration that can be achieved freehandedly while avoiding critical structures. The perioperative use of the VSP may give the surgeon guidance to place the implants safely and accurately in the planned positions, which may reduce the chance of implant malpositioning and loosening [

12,

23]

.

This study introduces and evaluates the use of a developed VSP method using simulated fluoroscopic images in patients with SI dysfunction undergoing SIJF. Conformity of achieved placement to planning was retrospectively evaluated, and it was analyzed whether this improved with an increase in case numbers since there may be an initial learning curve to work with a VSP [

24,

25,

26]

.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study. The first ten patients after the implementation of VSP were included in this study. The workflow was implemented in November 2021 as standard clinical care for SIJF in Medisch Spectrum Twente (MST, Enschede, The Netherlands). The institutional review board of MST approved in July 2022 all clinical evaluation studies where 3D technology, including VSP, was used as standard care. All patients underwent surgery before this date and are therefore exempted from informed consent. Patient characteristics and CT imaging were taken from the electronic health record. Also, survey data that was obtained to assess the added value of the VSP for the surgeon were retrospectively collected. For quality control purposes these surveys have been routinely administered for all applications where 3D technology was used in clinical practice.

The developed workflow includes the use of a preoperatively created VSP based on routine pre-operative CT imaging. The CT scans were made in multiple hospitals with various types of scanners and CT parameters. One experienced surgeon (approximately 100 prior SIJF surgeries) performed all interventions according to the procedure described in section 2.2. The surgeon could examine the 3D models, scroll through the CT scan with virtually inserted implants and observe the simulated fluoroscopy images before and during surgery. After the intervention, a routine postoperative CT was made with the Somatom Force scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Forcheim, Germany) to verify the positioning of the implants.

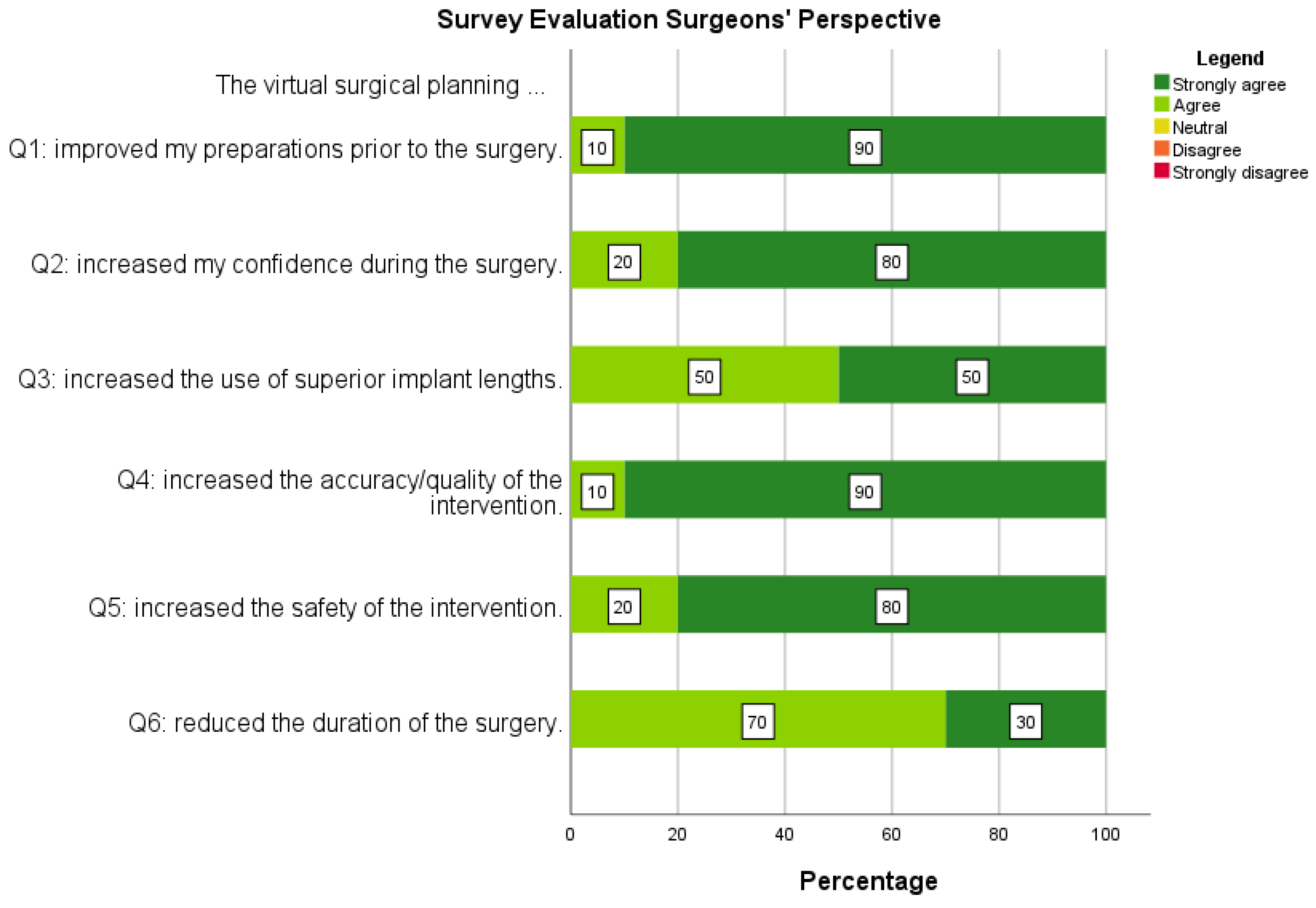

Multiple variables were assessed: implant placement accuracy by apex distance deviation and angular deviation, and the added value of the VSP for the surgeon that had been quantified by routinely collected survey data (six statements on the merit of VSP answered on a 5-point Likert scale).

2.2. Virtual Surgical Planning

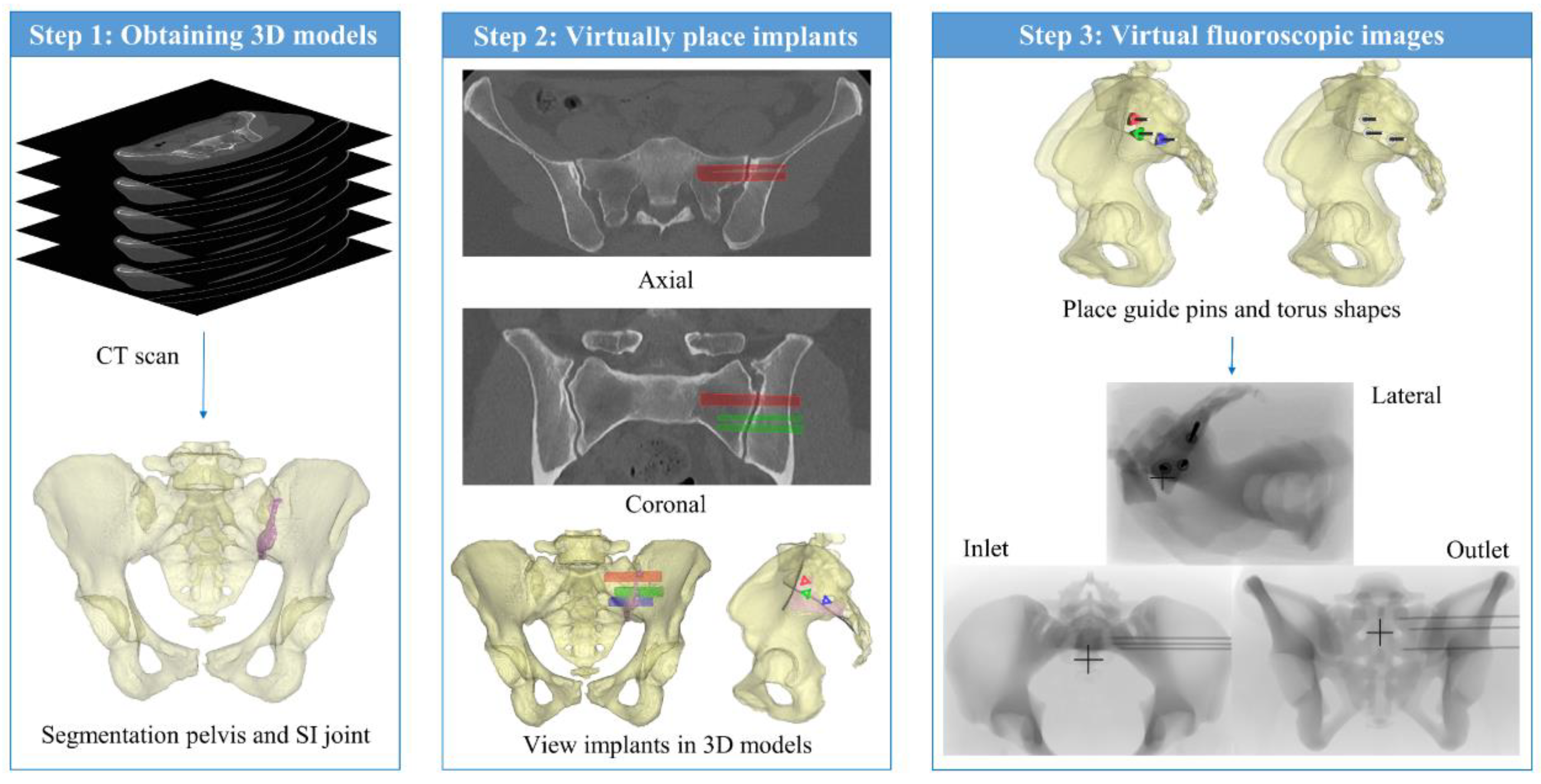

The method for VSP includes three main steps (

Figure 1). First, the 3D models of the pelvis and the SI joint were segmented based on pre-operative CT imaging. Second, the implants were virtually placed inside the CT data. Third, simulated fluoroscopic images of the VSP were constructed to mimic the intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging.

Based on thresholding, the pelvis and SI joint's synovial part were segmented from the CT scan using Mimics 23.0 (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). The pelvis was then filled and a 3D model was created. Filling the pelvis is necessary because the intraoperative landmarks, i.e. the ilial cortical densities (ICDs), become more visible in the lateral view when the 3D model of the pelvis is depicted transparently.

Then, the implants were virtually inserted inside the SI joint in the CT data by a technical physician. Similar to the used implant morphology, 3D models of implants ranging from 30 mm to 90 mm were constructed using 3-Matic 15.0 (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) since no CAD files of the implants were available. Depending on the patient's anatomy, three implants were virtually placed in the SI joint perpendicular to a true lateral view. The final position of the implants was determined based on the axial and coronal planes of the CT data. After virtually placing the implants inside the CT scan, the surgeon critically reviewed the implant positioning and confirmed the VSP.

To achieve an optimal planning for the individual patient, the number of implants, the distance between the implants, the relative position, and the implant depth are considered. Three implants were used since this gives superior outcomes compared to the use of two implants [

12,

13]. A 15 mm center-to-center distance between the parallel implants was generally maintained since this is part of the standard workflow in the used SIJF system. This distance can intraoperatively be obtained using a standard tool called the Parallel Pin Guide (iFuse Implant System). In case of unfavourable anatomy or if a different position allowed for the use of longer implants, other distances varying from 17 to 31 mm were selected. These different center-to-center distances can be achieved using the Variable Pin Guide from the system set. Using this tool, more distance between the implants will be gained, which results in more stable implant configurations [

12]. The SI joint consists of a synovial part and a ligamentous part. Approximately the anterior one-third of the joint is the synovial part and the posterior two-thirds is the ligamentous part [

27]. The implants are generally placed into the synovial part of the joint since this increases bone contact and thereby stability. Generally, the implants are virtually placed as deep as possible, but a safety margin of approximately 3 mm between the implant and the cortex of the sacrum (anterior cortex and cortex around the neural foramina) was maintained.

To translate the VSP to intraoperative imaging, simulated fluoroscopic images were reconstructed. First, using 3-Matic, 3D models of the guide pins and torus shapes, which resemble the entry points in the ilium, were constructed based on the implant positions in the VSP. Subsequently, based on the 3D models of the segmented pelvis, guide pins, and entry points, simulated fluoroscopic images were generated using the fluoroscopy module in Mimics 23.0. To make the actual and simulated fluoroscopic images as comparable as possible regarding divergence of the X-ray beam, care was taken to equalize the position of the X-Ray source with respect to the patient (distance and center of the beam) for the actual and the simulated cases. In case of the simulated lateral fluoroscopic image, the distance from the virtual X-ray source to the median plane of the patient was set to 72 cm and the position of the origin was located at an intersection point with overlapping ICDs at the height of S1. In case of the inlet and outlet views, the distance between the virtual X-ray source and the frontal plane was set to 72 cm. The origin was located around the sacrum. The angles of the virtual X-ray beam are determined by creating the optimal lateral, inlet and outlet views. The virtual fluoroscopic images are then added to a slideshow along with pictures of the 3D models and a video of the CT data containing the virtually inserted implants. Therefore, the images presented comprise: (1) Lateral view 3D model pelvis and implants. (2) Inlet view 3D model pelvis and implants. (3) Outlet view 3D model pelvis and implants. (4) Simulated lateral fluoroscopic image (5) Simulated lateral fluoroscopic image with planned implant positions. (6) Simulated lateral fluoroscopic image with planned guide pins and torus shapes. (7) Simulated inlet fluoroscopic image with planned guide pins. (8) Simulated inlet fluoroscopic image with planned implant positions. (9) Simulated outlet fluoroscopic image with guide pins. (10) Simulated outlet fluoroscopic image with implants. (11) Video of CT data containing planned implant positions.

2.3. SIJF Procedure with VSP

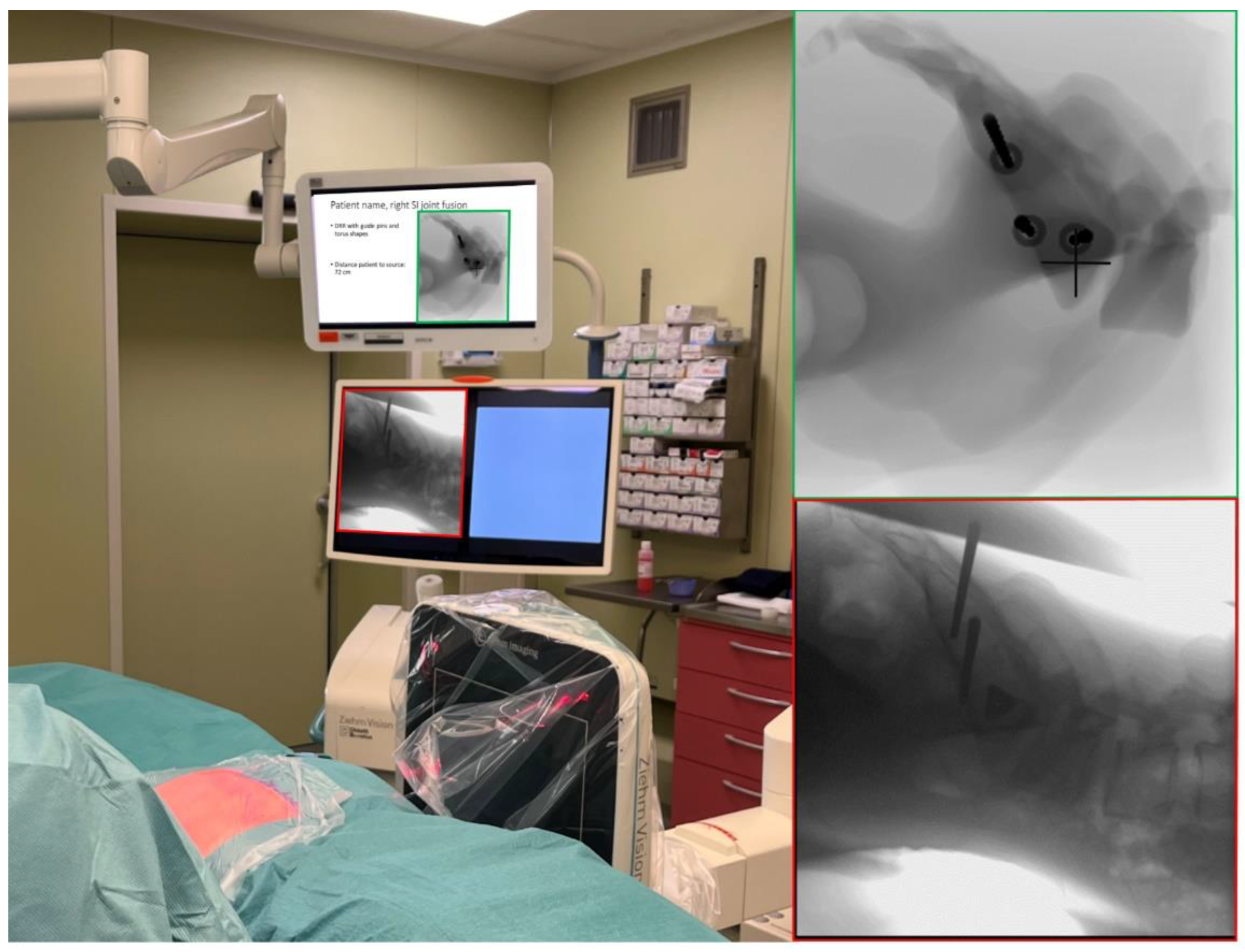

Figure 2.

Overview intraoperative set up with C-arm, C-arm monitor (red), and extra monitor with slides containing virtual fluoroscopic images (green).

Figure 2.

Overview intraoperative set up with C-arm, C-arm monitor (red), and extra monitor with slides containing virtual fluoroscopic images (green).

First, the surgeon reproduced the simulated lateral, inlet, and outlet views using intraoperative fluoroscopic guidance, i.e. a C-arm, while the patient lies in prone position on the OR table. The simulated fluoroscopy images were displayed in a slideshow on a monitor next to the monitor of the C-arm. After selecting the optimal positions for the C-arm, the position of the base of the device was locked and the location of the lasers, incorporated in the device, were marked onto the patient. The base of the device stayed in that position and all C-arm movements were applied to create the views except tilting. To change between the views, the operation table was moved using the remote control instead of moving the base of the fluoroscopy device. By keeping the base in place and not tilting the device, the surgeon can more easily recreate the original views after switching between lateral, inlet, and outlet. When the views are marked onto the patient, the sterile field is created. The incision was made according to standard protocol. Then, the entry point for the first guide pin is determined using lateral fluoroscopic guidance and using the simulated lateral image (

Figure 3, step 3, lateral) as a reference. Subsequently, using the simulated inlet and outlet views and the corresponding intraoperative fluoroscopic views, the guide pin was driven into the pelvis using a surgical hammer. Afterwards, the implant is placed over the guide pin according to standard protocol. Then this process was repeated for the second and third implant. Using the Parallel or Variable Pin Guide, depending on the planned distance between the implants, the guide pins were placed parallel to the first. Occasionally, the surgeon deviated from the planning. For example, change the implant length or the distance between the implants when necessary. The intraoperative fluoroscopy images consistently took precedence over the simulated fluoroscopic images.

2.4. Data Processing and Statistics

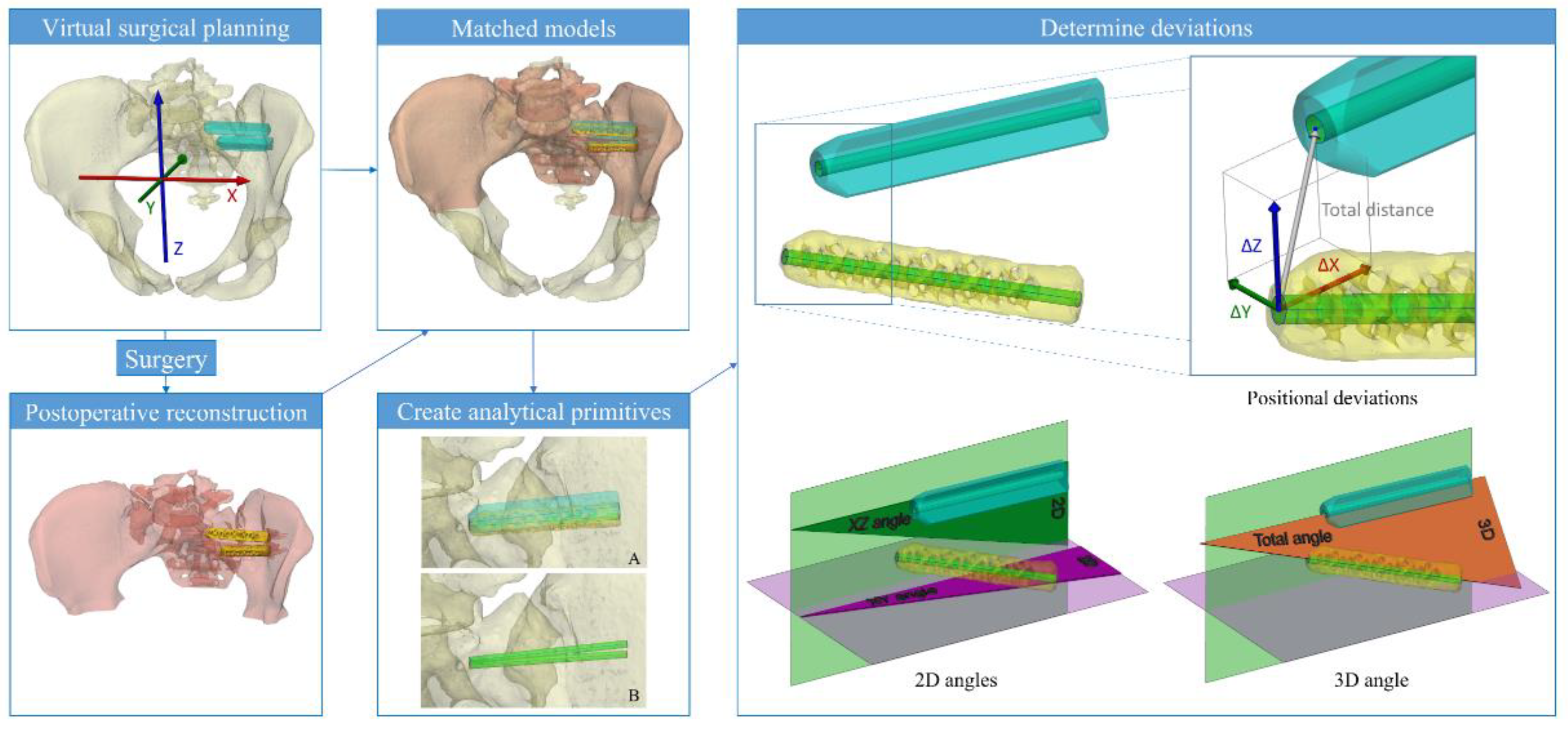

Multiple analyses were performed to evaluate the implant placement accuracy, i.e. conformity of achieved placement, the malpositioning complications, the possible increase in accuracy, and the added value based on the surgeon's perspective. To assess the implant placement accuracy, a method has been developed that compares the implant positioning in routine postoperative CT data to the implant positions in the VSP using Materialise Mimics 23.0 and 3-Matic 15.0. The postoperative pelvis and implants were registered, i.e. that is matched, with the pre-operative 3D model of the pelvis. Per implant seven variables were determined, four positional and three angular deviations. To derive the variables, the coordinate system of the preoperative CT was used. An overview of the method and the definition of the coordinate system is shown in

Figure 3. The positional variables are the deviation of planned and achieved apex positions in the X-, Y-, and Z-direction (ΔX, ΔY, and ΔZ), and the total distance between planned and postoperatively positioned apexes of the implants. For the angular deviations, the angle between the XY-, YZ-plane, and the total 3D angle between the implants were determined. For convenience the right-sided SIJF are mirrored as if they were left-sided, so outcomes of both sides can be compared. To assess the implant placement accuracy, the seven variables of all implants are presented in a boxplot. The 2D angular deviations can both be a negative or positive angle, where a negative angle indicates a clockwise rotation and a positive angle a counterclockwise rotation. Five measures (ΔX, ΔY, ΔZ, XY-, and YZ-angle) are relative measures. This way, when a deviation is more likely to occur in a certain direction, the mean or median deviation of a particular measure will not center around zero. This can be useful in finding flaws in the surgical method. Overall, the five relative and two absolute measures express the implant placement accuracy using a VSP for SIJF.

Furthermore, the number of implants penetrating the neural foramen, the sacral canal, and the anterior cortical wall of the sacrum, i.e. malpositioning complications or nerve root impingement, were monitored by analyzing the postoperative CT data.

Descriptive statistics were performed and normality checks were performed by histogram analysis. Therefore, data is expressed with mean + standard deviation (SD) or median + interquartile range (IQR).

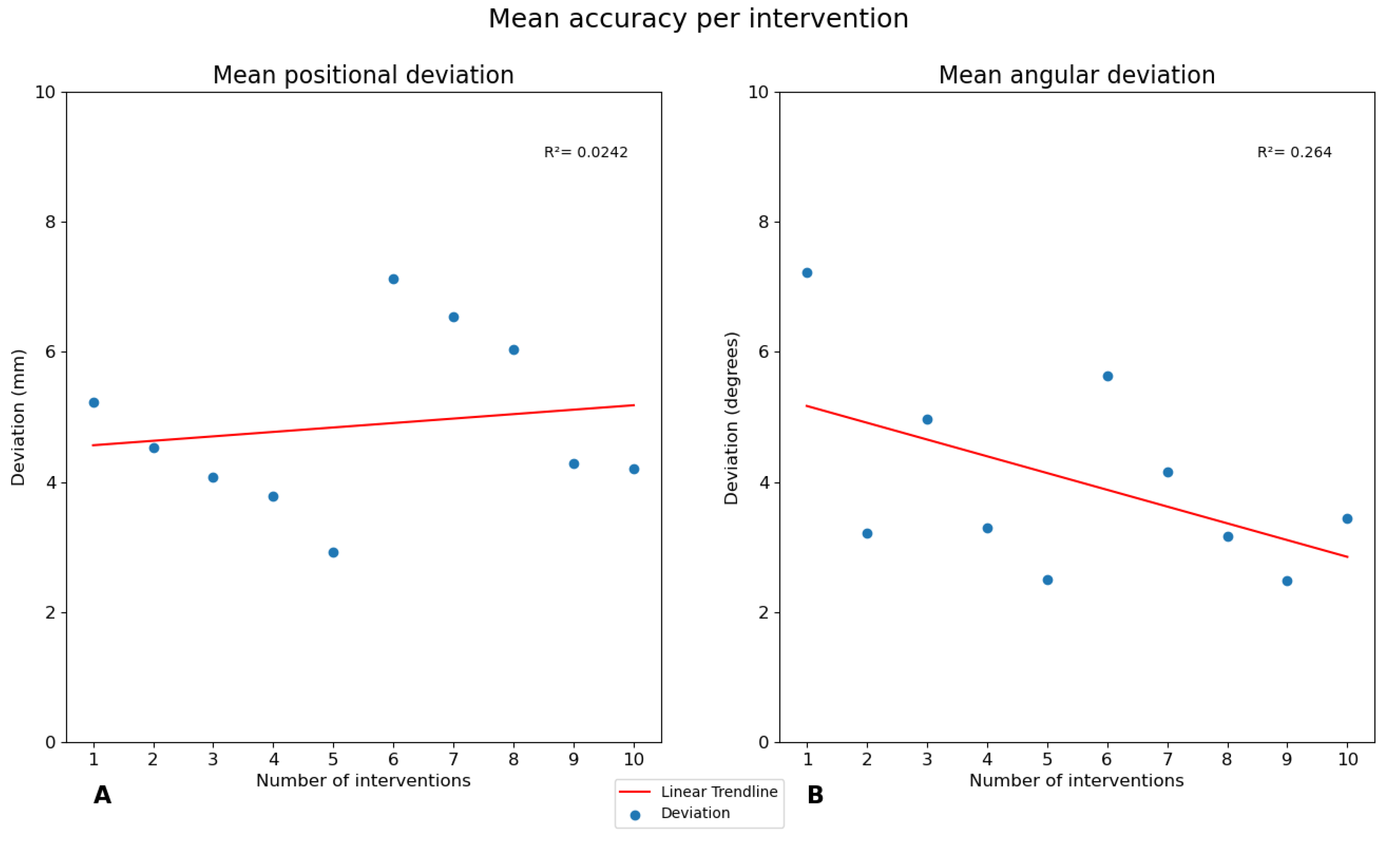

To determine whether the accuracy improved with an increase in case numbers, the average total positional deviation and total angular deviation per intervention was plotted per intervention. A linear trendline and the determination coefficient (R2) were determined for the data.

Routinely collected quality control data was assessed to analyze the added value based on the surgeon's perspective. This routine survey presented various statements to the surgeon after the interventions. The statements were: The virtual surgical planning: (1) improved your preparations before the surgery. (2) increased your confidence during the surgery. (3) increased the use of superior implant lengths. (4) increased the safety of the intervention. (5) increased the quality of the intervention. (6) reduced the duration of the surgery. The surgeon could respond to the statements with strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, or strongly agree.

4. Discussion

This study is the first that combines VSP and simulated fluoroscopic images to improve SIJF for patients suffering from SI dysfunction. Furthermore, this is the first study that assesses implant placement accuracy for SIJF in clinical practice using a quantitative evaluation method.

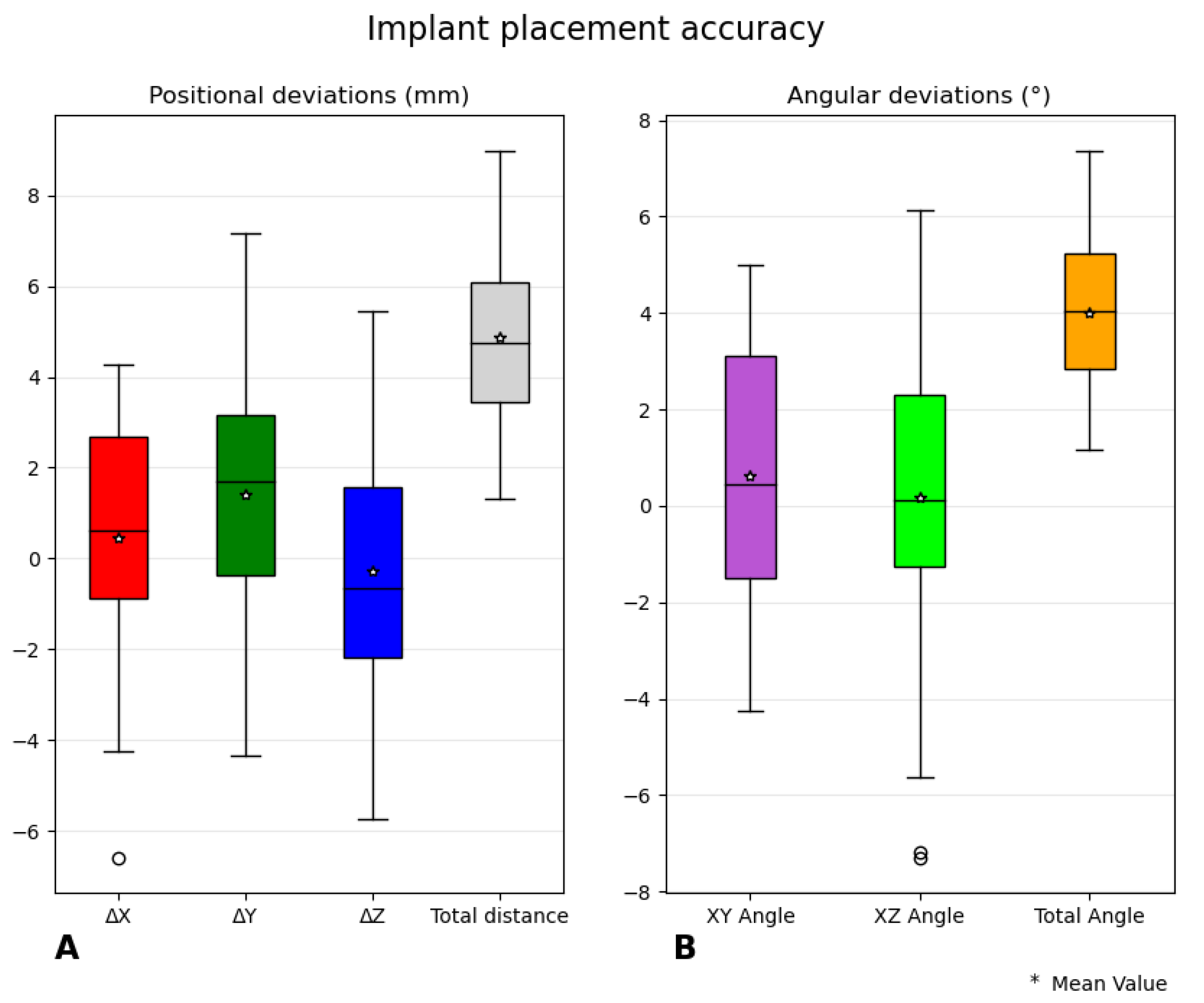

The implant placement accuracy by apex distance deviation and angular deviation was determined by comparing the VSP to the implant position in the postoperative CT. The positional deviation at the apex of the implants had a mean deviation of 4.9 ± 1.26 mm and the angular deviation was 4.0 ± 1.44°. In ten SIJFs, thirty implants were placed without major complications, i.e. nerve root impingement; therefore, no revision was required to retract an implant.

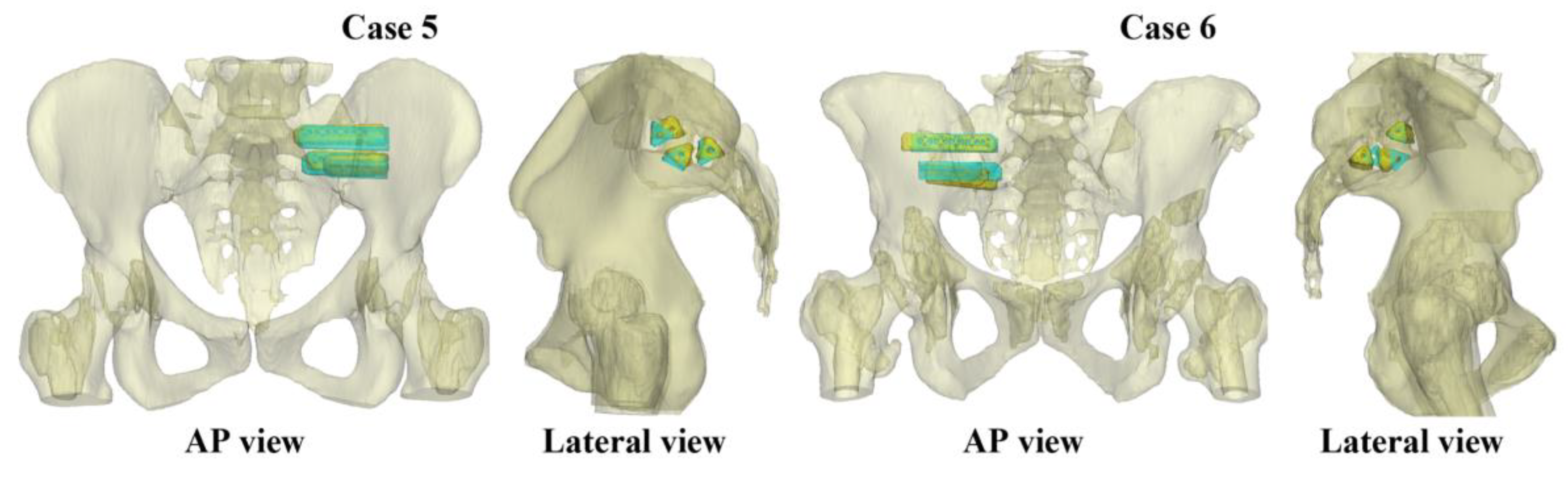

Since this is the first study that determined implant placement accuracy in SIJF there are no other studies as comparison. Furthermore, it's important to note that an accuracy comparison with cases prior to the introduction of VSP for SIJF is not possible, as accuracy cannot be determined when VSP is not used. To interpret the deviation of the achieved implant positioning, the results of two cases are shown in

Figure 7. In this figure, the comparisons between the VSP and achieved implant positions can be seen. Case 5 showed a relatively low mean deviation of 2.9 mm and 2.5°, where case 6 showed a relatively high mean deviation of 7.1 mm and 5.6° for the positional and angular deviation. It can be seen that also this higher deviation did not lead to implant malposition complications. Therefore, it can be stated that the measured deviation is clinically acceptable.

In spine surgery, similar analyses have been performed [

28]. Pijpker et al. evaluated the placement accuracy of pedicle and lateral mass implants using drill guides with an entry point deviation of 1.40 ± 0.81 mm and a 3D angular deviation of 6.70 ± 3.77° (mean ± standard deviation) [

28]. The deviation at the entry point cannot be compared to the deviation at the apex, but considering the higher angular deviation, it is assumed that the deviation at the apex would be similar to our findings. It is important to mention that our study utilized a free-handed surgical approach, which may explain the slightly lower accuracy observed in our cases. Ultimately, similar to spine surgery, the use of patient-specific surgical guides could lead to a more accurate recreation of VSP during SIJF. However, due to the minimally invasive nature of SIJF guide seating directly on the bone is not possible. Besides the accuracy, a surgical guide for SIJF might also enable more stable, trans-articular (non-parallel) implant configurations [

23]. Currently, using solely 2D fluoroscopic guidance, this is not possible.

Furthermore, the total distance, angular deviation, and deviation in X, Y and Z directions were assessed (

Figure 4). The boxplots containing the ΔX, ΔY, & ΔZ are not exactly centered around zero, meaning that the error occurs slightly more in a particular direction. The slope of the ilium can explain the +ΔY since this slope descends mostly in the posterior direction, and it is assumed that this slope can influence the positioning of the guide pins. The +ΔX (lateral direction) can be explained by the surgeon being careful not to place the implants too deeply, resulting in a deviation in implant depth compared to the VSP. For the ΔZ, we cannot think of an explanation, possibly when the number of implants increases the ΔZ will center around zero.

A minor limitation of the quantitative evaluation method is that the coordinates of the CT data were used, and no correction was applied for patients that were slightly tilted in the CT scan. This results in that the pelvises of patients can be slightly rotated in the coordinate system of the CT data, resulting in the differently orientated small directional deviations, i.e. ΔX, ΔY, ΔZ, XY angle, and XZ angle, with respect to the anatomical axes. This error is mainly present in deviations for ΔX and ΔY since this is the plane in which the patients are mostly tilted. This error does not affect the size of the deviation, and it solely affects the direction.

The remaining deviation observed in our study, which can be attributed to the free-handed approach, is likely the primary factor. However, it is worth noting that an alternative explanation could be that the angle of the intraoperative lateral fluoroscopic images might be slightly different from the simulated true lateral image due to that the patient might be slightly tilted or improper positioning of the C-arm, resulting in not obtaining an intraoperative true lateral view. Furthermore, in some cases, it is even more challenging to obtain an intraoperative true lateral view due to the absence of anatomical landmarks, i.e. the ICDs, on fluoroscopic imaging. Not obtaining a true lateral view likely ranks as the second most significant contributor to the remaining deviation in implant placement accuracy. Ideally, displaying the VSP onto the intraoperative images would be even more helpful, also for the inlet and outlet views. Therefore, a method should be developed that is able to superimpose the VSP onto intraoperative fluoroscopic images [

22]. This can replace the simulated fluoroscopic images and most likely increases the implant placement accuracy.

The most serious complication after SIJF is nerve impingement. In a study by Duhon et al., 3 out of 172 patients developed neuropathic pain related to nerve impingement [

29]. Furthermore, a review by Heiney et al. described that 2.1% of the interventions required a revision due to nerve root impingement [

30]. Both of these studies indicate that this serious complication remains prevalent. Presumably, due to the use of VSP the chance of these major complications can be reduced since the surgeon knows the anatomy of each patient and where to place the implants safely. However, to be able to draw firm conclusions on this, more surgeries using VSP should be performed. Ideally, this should be confirmed by comparing the outcomes of SIJF with VSP to the gold standard, the conventional SIJF using 2D fluoroscopic imaging.

The main limitation of this study is that it was an analysis of retrospectively collected data, focusing on the implant placement accuracy compared to the VSP and not comparing clinical outcomes with and without the use of VSP. Further research should be performed to conduct such comparison, including patient related outcome measures (PROMs).

In contrast to other new technologies implemented in clinical practice [

24,

25,

26], VSP for SIJF showed no increase in accuracy when the surgeon gained more experience in using VSP. Despite the increasing accuracy after the first five cases, the scatterplot for all ten cases seems rather random. There are three possible explanations for the absence of this increase in accuracy. First, the supplemented information is self-explanatory and given the experience of the surgeon in reaching the targeted position, little learning is to be expected. Rather, we expect the major gain to be in better implant positioning due to the better (virtual) planning. However, this was not part of the current study. Second, as described earlier, obtaining a true lateral view can be difficult. Therefore, a slight discrepancy of a few degrees between the fluoroscopic true lateral and the intraoperative lateral view can result in lower implant placement accuracy. This may occur randomly and may explain the seeming randomness of the scatterplot in

Figure 5. Third, in this study, the surgeon was asked to review the VSP, and if needed, adaptations were made to the desires of the surgeon. This way, the surgeon was closely involved in determining the optimal position for the implants, resulting in adherence to the pre-operative planning. This also probably increased the surgeon's trust in the VSP. This trust may have resulted in the surgeon feeling confident using the VSP and may have reduced the likelihood of an increase in accuracy when the surgeon became more proficient in using the VSP.

According to the survey data, the surgeon who performed the ten interventions was exceptionally positive about using VSP in SIJF. According to the surgeons' feedback, utilizing VSP led to improved preparedness, increased confidence, facilitated the use of longer implants, enhanced the safety of the intervention, improved the quality of the surgical procedure, and reduced the overall surgical duration. However, it is important to note that the positive experience of one surgeon with VSP may not necessarily generalize to other surgeons. The fact that this surgeon had access to a medical 3D lab in his hospital and was already accustomed to 3D technology may have influenced his positive perception of VSP. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that this surgeon does not want to perform the surgery without VSP anymore since he believes the VSP substantially decreases the risk of implant malpositioning. From an ethical point of view, this makes it difficult to plead for a future RCT. However, to objectively assess the added value, a comparative study involving clinical outcomes, including assessment of radiation dose, implant lengths, duration of the surgery, complications (malposition complications, implant loosening, wound infection, etc.), and PROMs, preferably performed by multiple surgeons, should be performed. Nevertheless, in absence of these outcome data, this study already gives a first impression of the added value and the feasibility of VSP in SIJF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., J.N., E.H., G.T., S.L., M.K. and F.S.; methodology, N.K., J.N., E.H., G.T., S.L., M.K. and F.S.; validation, N.K., J.N., E.H., G.T., S.L., M.K. and F.S.; formal analysis, N.K.; data curation, N.K., J.N. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.K., J.N., E.H., G.T., M.K. and F.S.; visualization, N.K., E.H., G.T., M.K. and F.S.; supervision, J.N., G.T., M.K. and F.S.; project administration, N.K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.