Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

03 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Research questions

Databases

Search process

3. Results

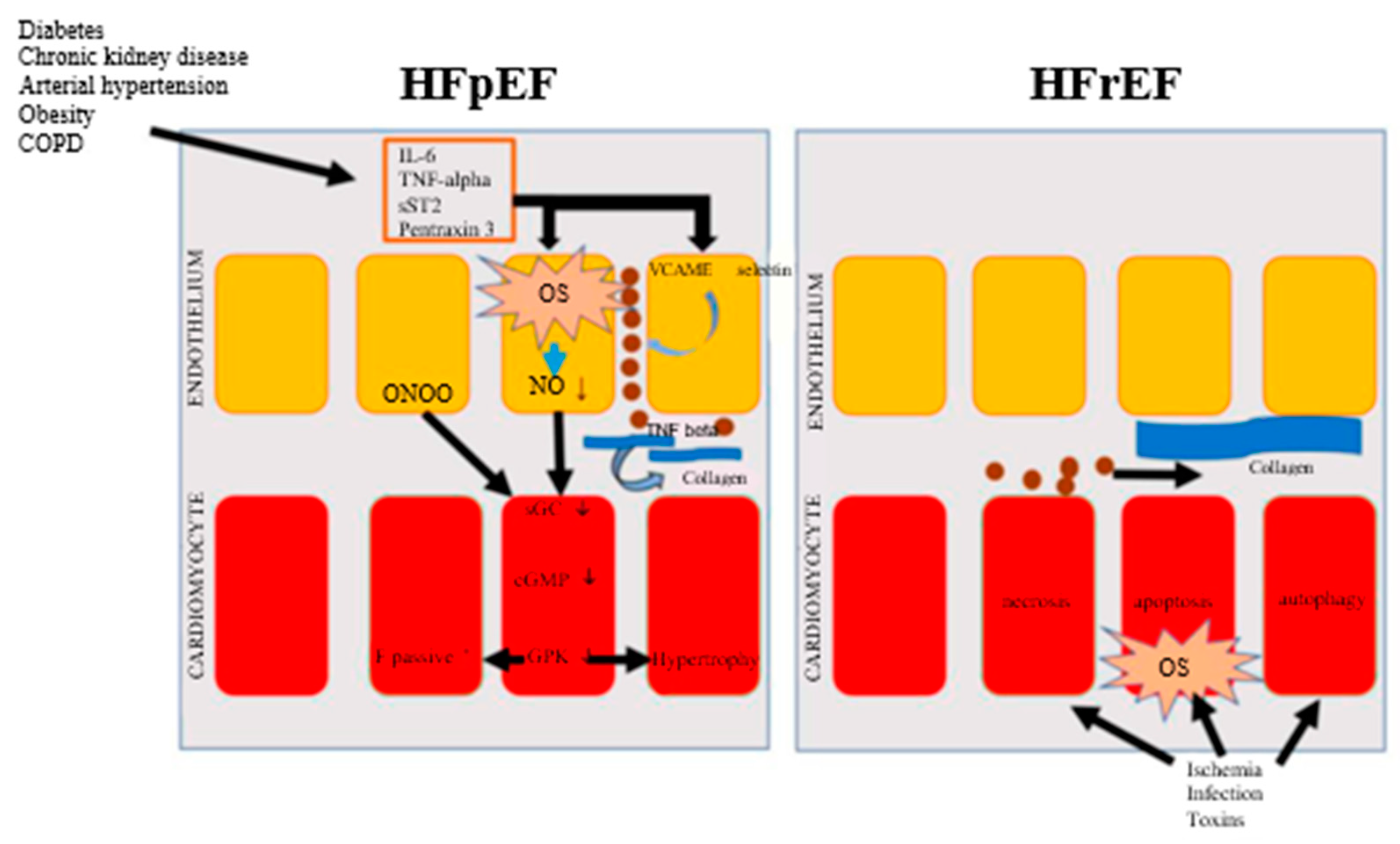

3.1. Fundamental pathophysiological aspects in HFrEF and HFpEF

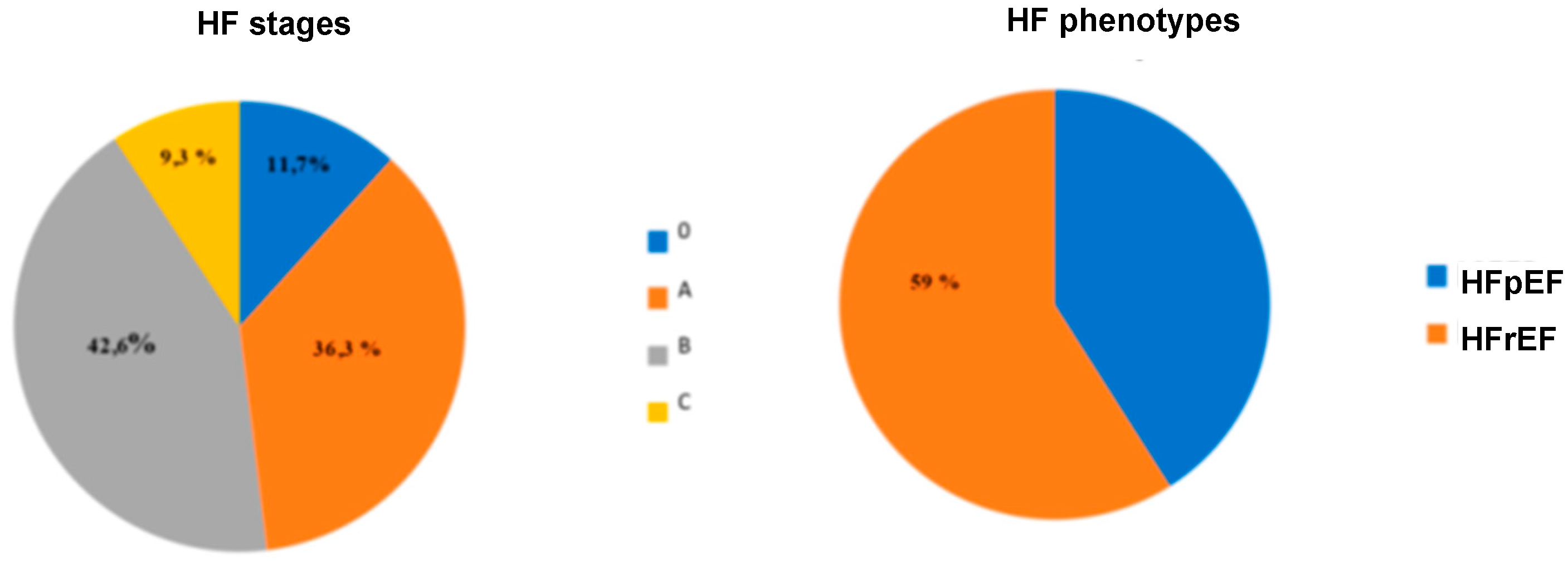

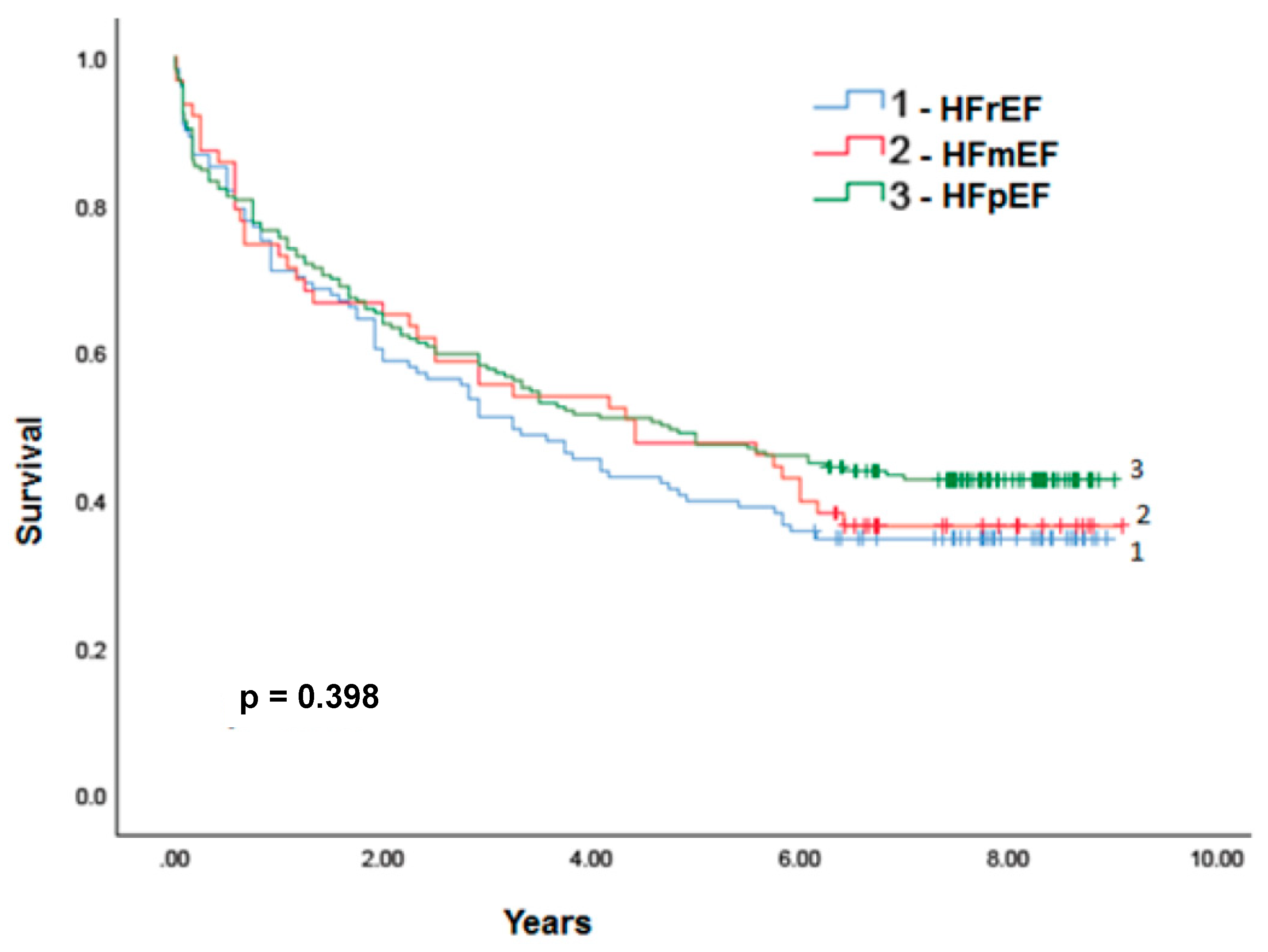

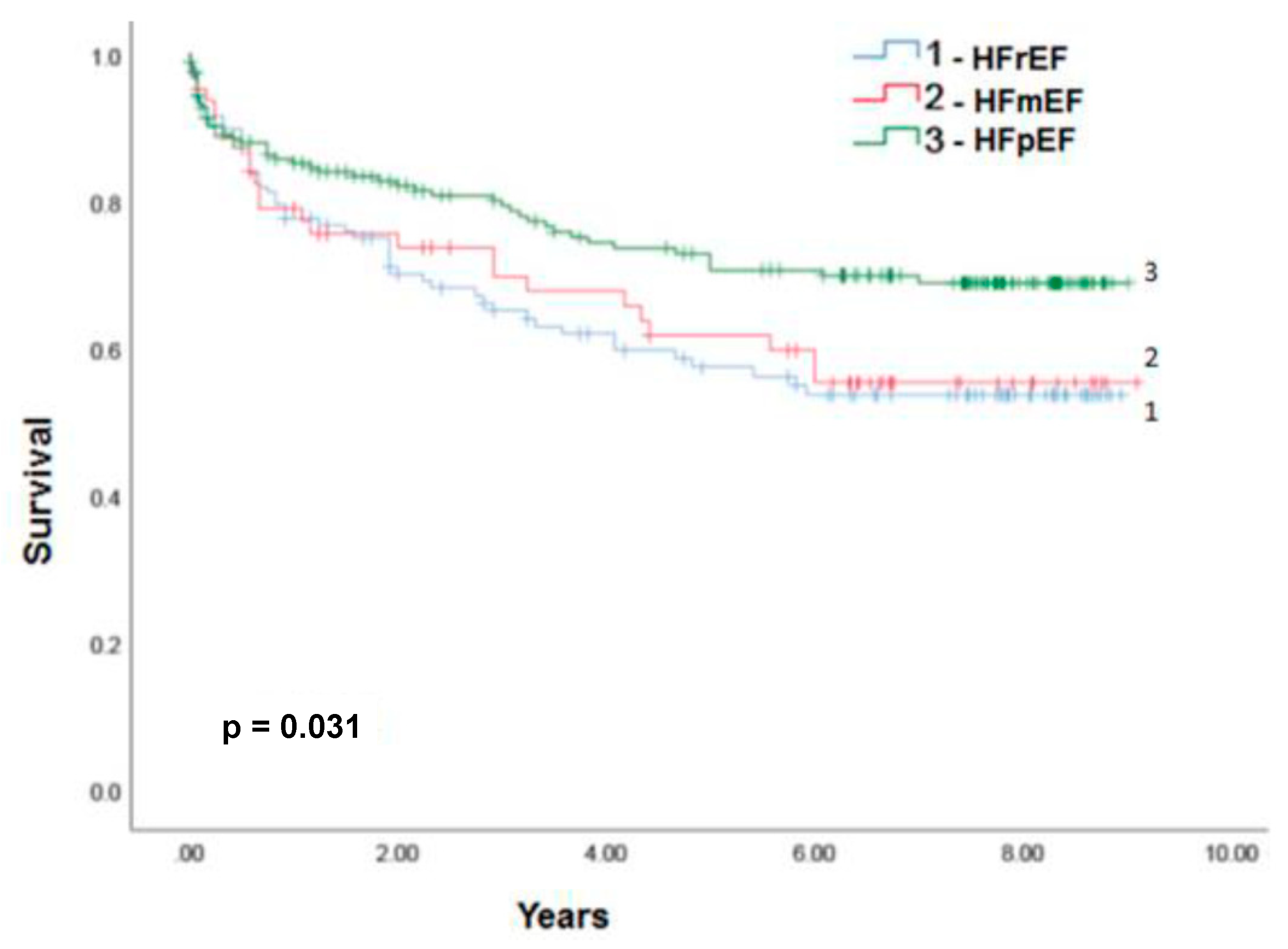

3.2. HFpEF and HFmrEF epidemiology in relation to HFrEF

4. Discussion

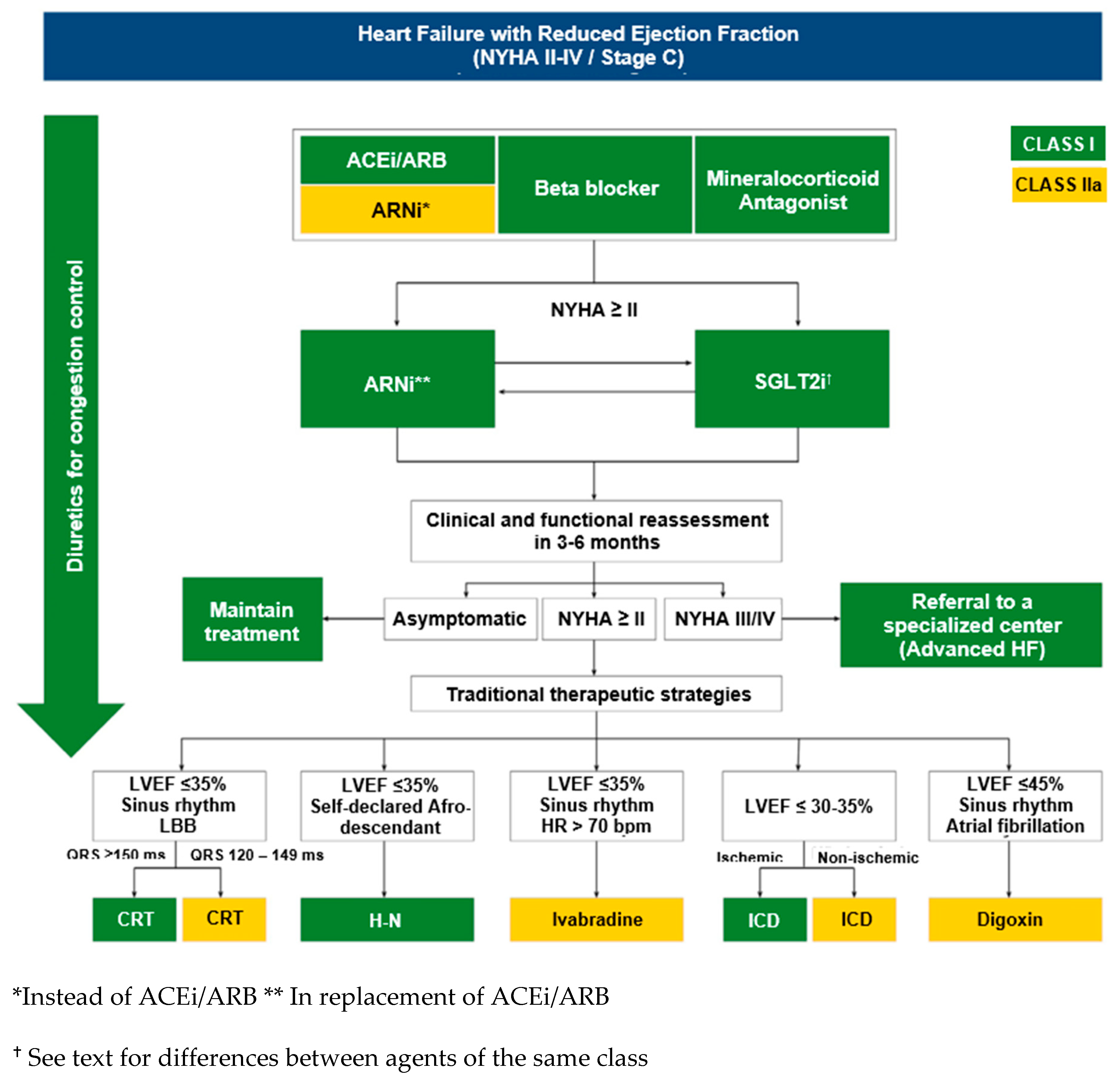

4.1. Contemporary pharmacological management of HF and unmet needs

| Recommendations | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Loop diuretics or thiazides to decrease congestive symptoms | I | B |

| Treatments for comorbidities such as myocardial ischemia, AF and hypertension, according to current guidelines, to reduce symptoms or disease progression | I | C |

| Spironolactone to reduce hospitalizations | IIA | B |

| ARBs to reduce hospitalizations | IIB | B |

4.2. Sacubitril-valsartan for the treatment of HFpEF and HFmrEF: pharmacological principles

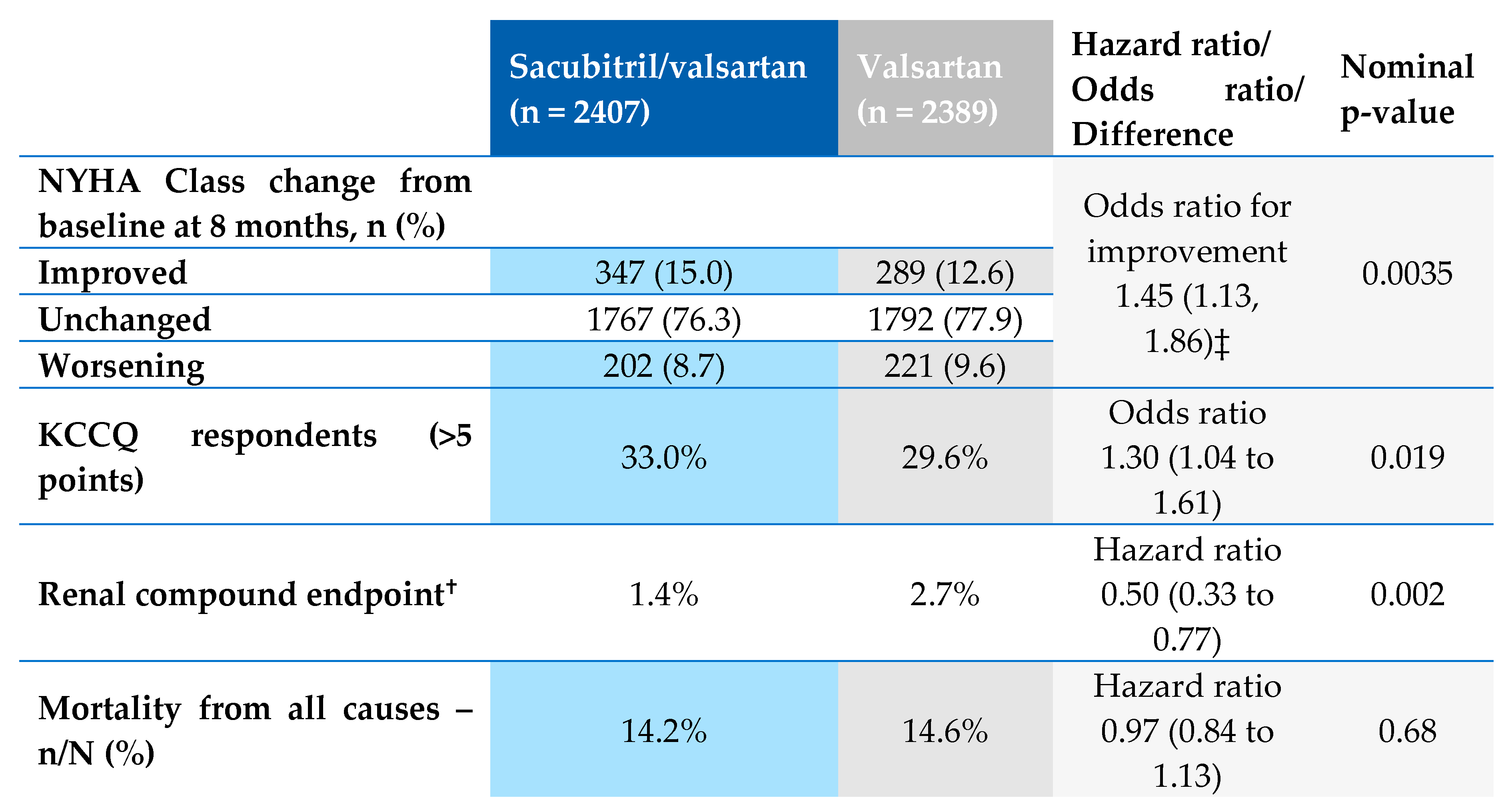

4.3. Sacubitril-valsartan for the treatment of HFpEF and HFmrEF: clinical studies

| LCZ696 (n = 149) | Valsartan (n = 152) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any serious adverse event Deaths Heart failure Acute Coronary Syndrome Arrhythmia Renal Any adverse event Symptomatic hypotension Kidney dysfunction Hyperkalemia Discontinuation due to AE Laboratory abnormalities Potassium >5.5 mmol/l Potassium ≥6.0 mmol/l ≥50% decrease in GFR |

22 (15%) 1 (1%) 4 (3%) 4 (3%) 2 (1%) 2 (1%) 96 (64%) 28 (19%) 3 (2%) 12 (8%) 15 (10%) 24 (16%) 5 (3%) 5 (3%) |

30 (20%) 2 (1%) 6 (4%) 4 (3%) 2 (1%) 3 (2%) 111 (73%) 27 (18%) 7 (5%) 9 (6%) 17 (11%) 16 (11%) 6 (4%) 4 (3%) |

0.32 0.99 0.77 0.74 0.63 0.98 0.14 0.88 0.34 0.50 0.90 0.21 0.97 0.98 |

5. Conclusion

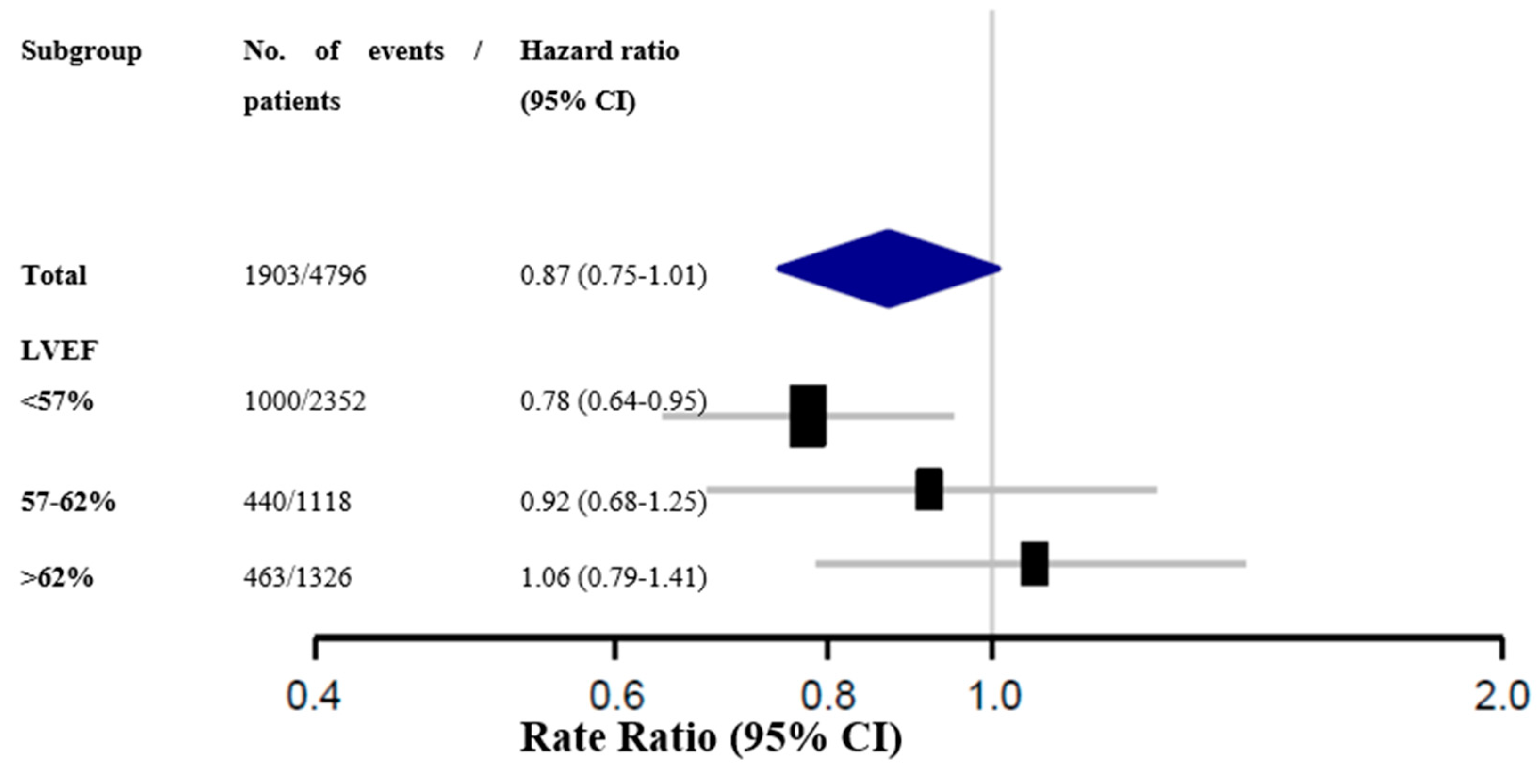

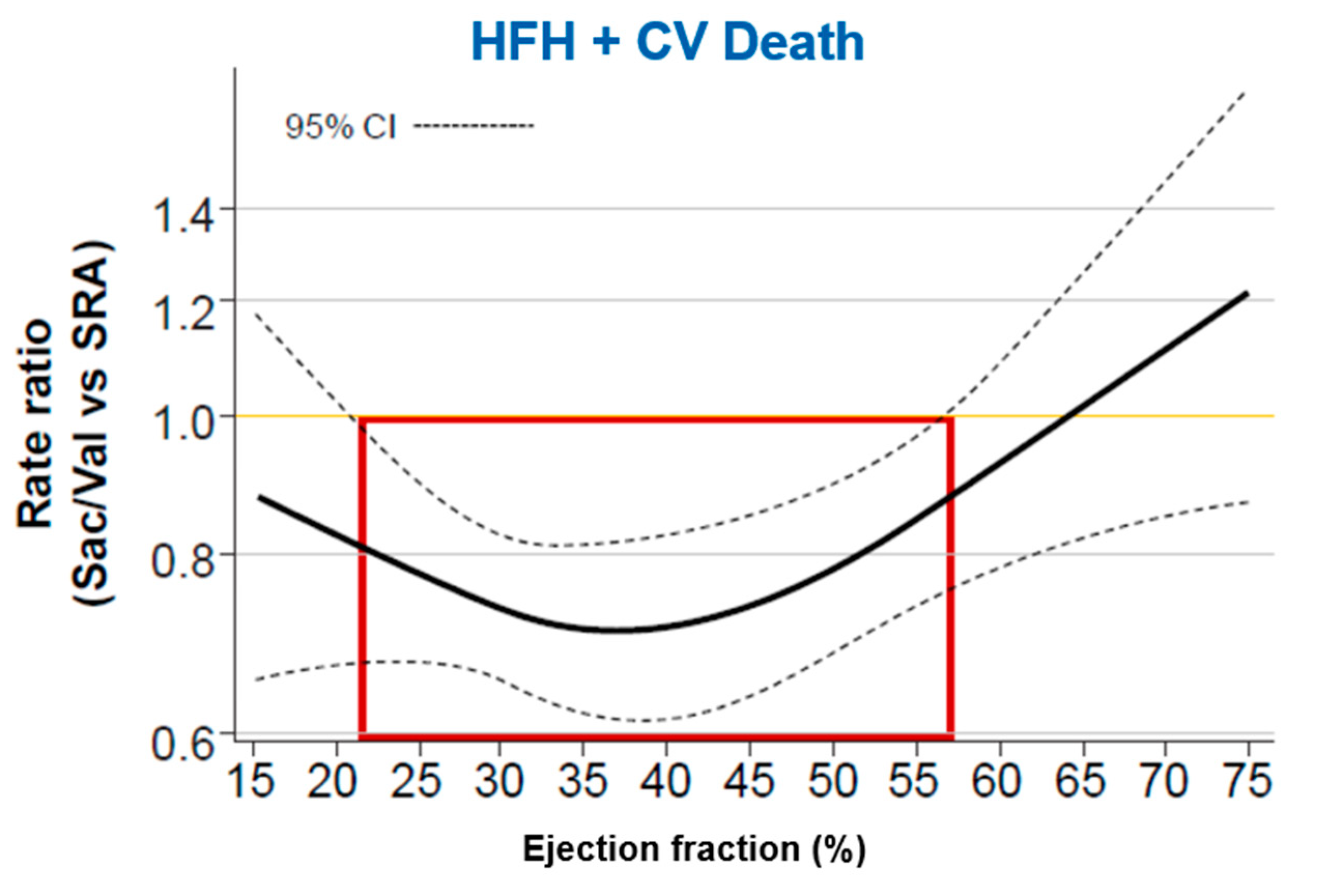

Considerations on the analysis of subgroups of the PARAGON HF study

Final conclusions about Sacubitril-valsartan for HF treatment with below normal LVEF

- -

- HFpEF and HFmrEF are highly prevalent syndromes, causing disabling symptoms and frequent hospitalizations in the elderly, many of whom are females, and for whom there is no approved treatment;A well-designed study with the largest number of participants to date published for this population showed statistically significant results in reducing renal endpoints, improvement of performance status and it was safe;

- -

- In a pre-specified subgroup analysis of the PARAGON-HF study, sacubitril-valsartan showed benefit in the combined primary endpoint in patients with LVEF equal to or less than the 57% median;

- -

- Additional data shows that other drugs act on neurohumoral pathways also seem to be beneficial in patients with HF and lower rates of LVEF in the HFpEF setting, i.e, below the normal;

- -

- The update of the Brazilian Guidelines on HF 2021 already recommends the use of sacubitril-valsartan for patients with HFmrEF;

- -

- The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently approved sacubitril-valsartan as below normal ejection fraction HF treatment;

Declaration of interest

References

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.S.; Tsutsui, H.; et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: A report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail 2021, 23, 352–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galderisi, M.; Cosyns, B.; Edvardsen, T.; et al. 2016–2018 EACVI Scientific Documents Committee. Standardization of adult transthoracic echocardiography reporting in agreement with recent chamber quantification, diastolic function, and heart valve disease recommendations: An expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017, 18, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Roger, V.L.; Redfield, M.M. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017, 14, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, A.L.; Rosa, M.L.; Martins, W.A.; Correia, D.M.; Fernandes, L.C.; Costa, J.A.; Moscavitch, S.D.; Jorge, B.A.; Mesquita, E.T. The Prevalence of Stages of Heart Failure in Primary Care: A Population-Based Study. J Card Fail. 2016, 22, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, L.C.; Danzmann, L.C.; Bartholomay, E.; Bodanese, L.C.; Donay, B.G.; Magedanz, E.H.; Azevedo, A.V.; Porciuncula, G.F.; Miglioranza, M.H. Survival of Patients with Acute Heart Failure and Mid-range Ejection Fraction in a Developing Country - A Cohort Study in South Brazil. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021, 116, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcondes-Braga, F.G.; Moura, L.A.Z.; Issa, V.S.; et al. Emerging Topics Update of the Brazilian Heart Failure Guideline - 2021. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021, 116, 1174–1212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diretriz Brasileira da Insuficiência Cardíaca Crônica e Aguda. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018;Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 2018, 111, 436–539.

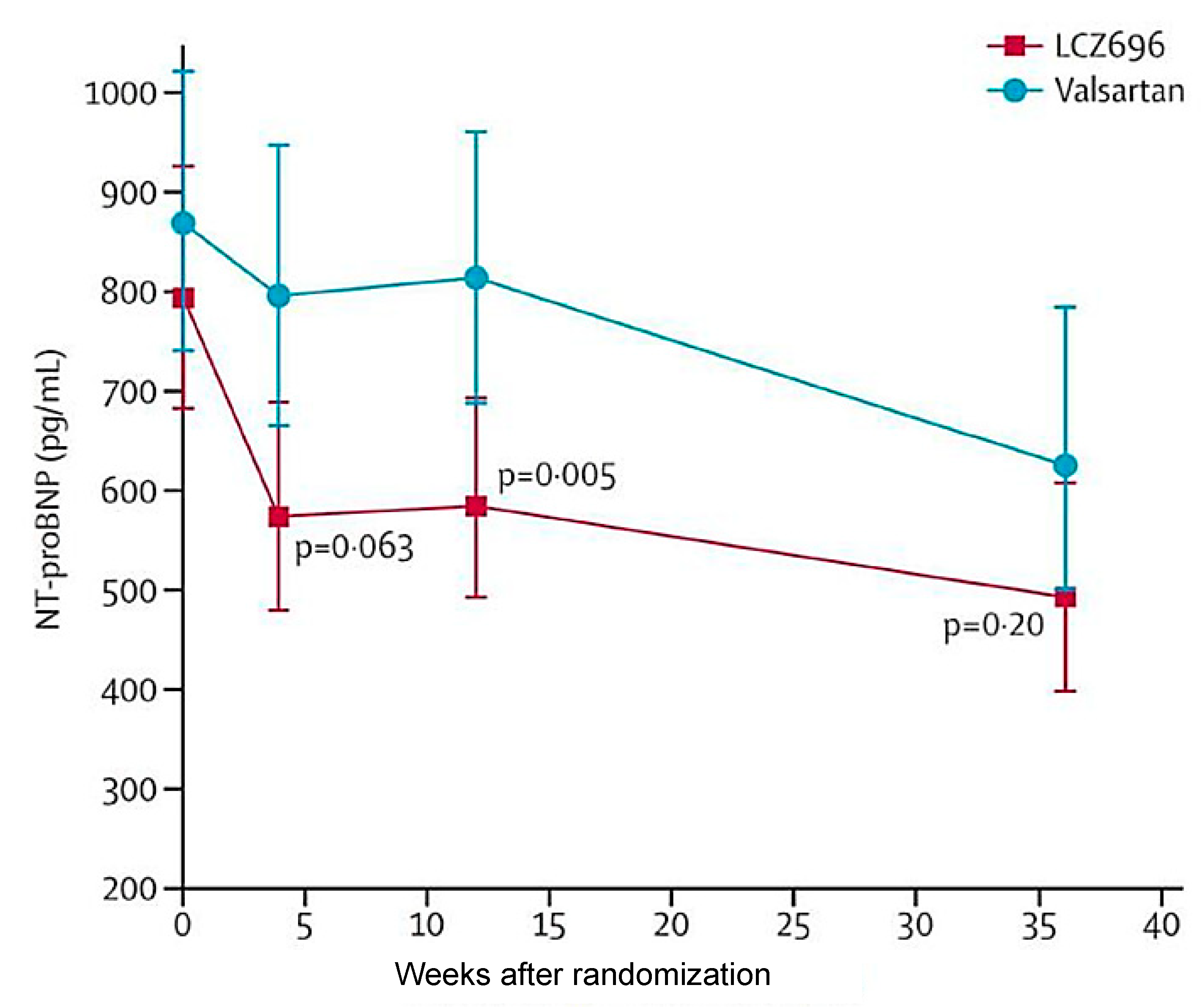

- Solomon, S.D.; Zile, M.; Pieske, B.; et al. Prospective comparison of ARNI with ARB on Management Of heart failUre with preserved ejectioN fracTion (PARAMOUNT) Investigators. The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A phase 2 double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012, 380, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; et al. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl JMed 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

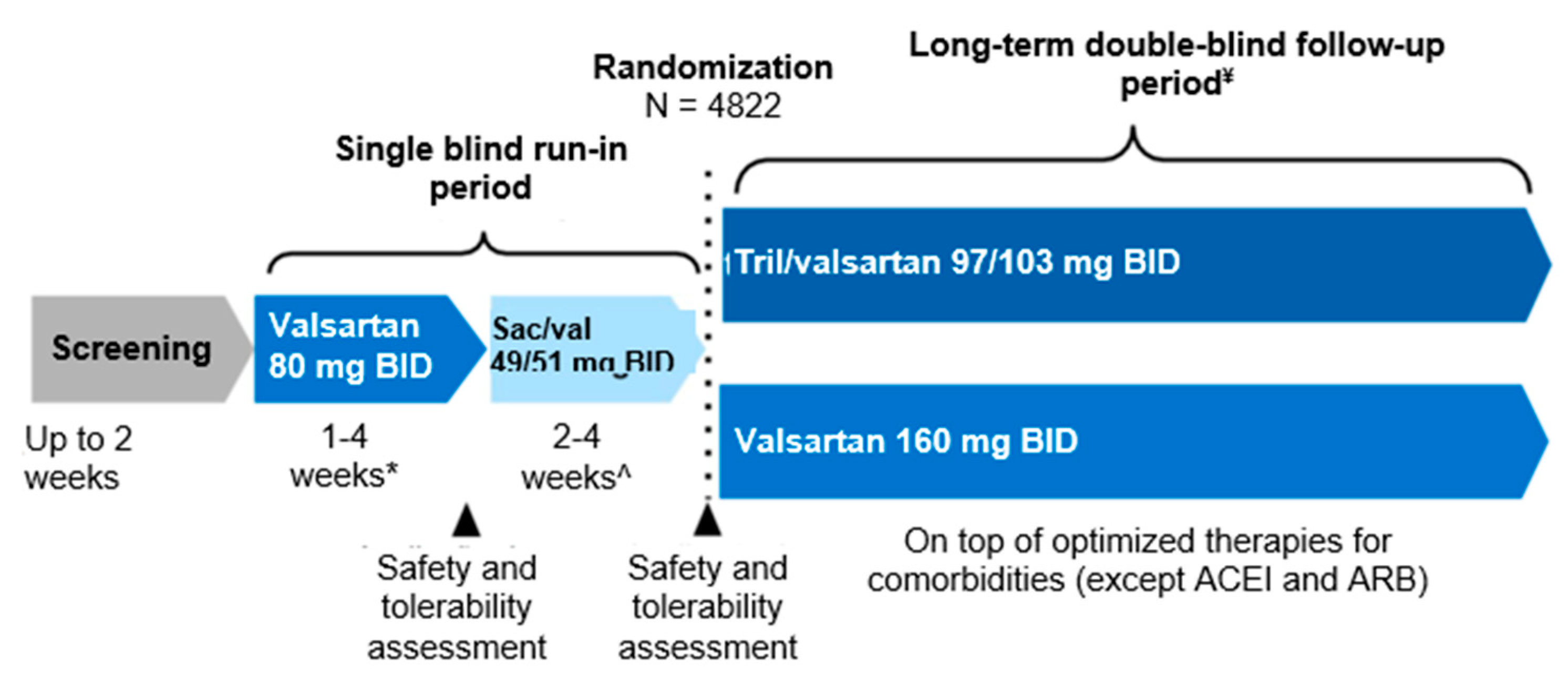

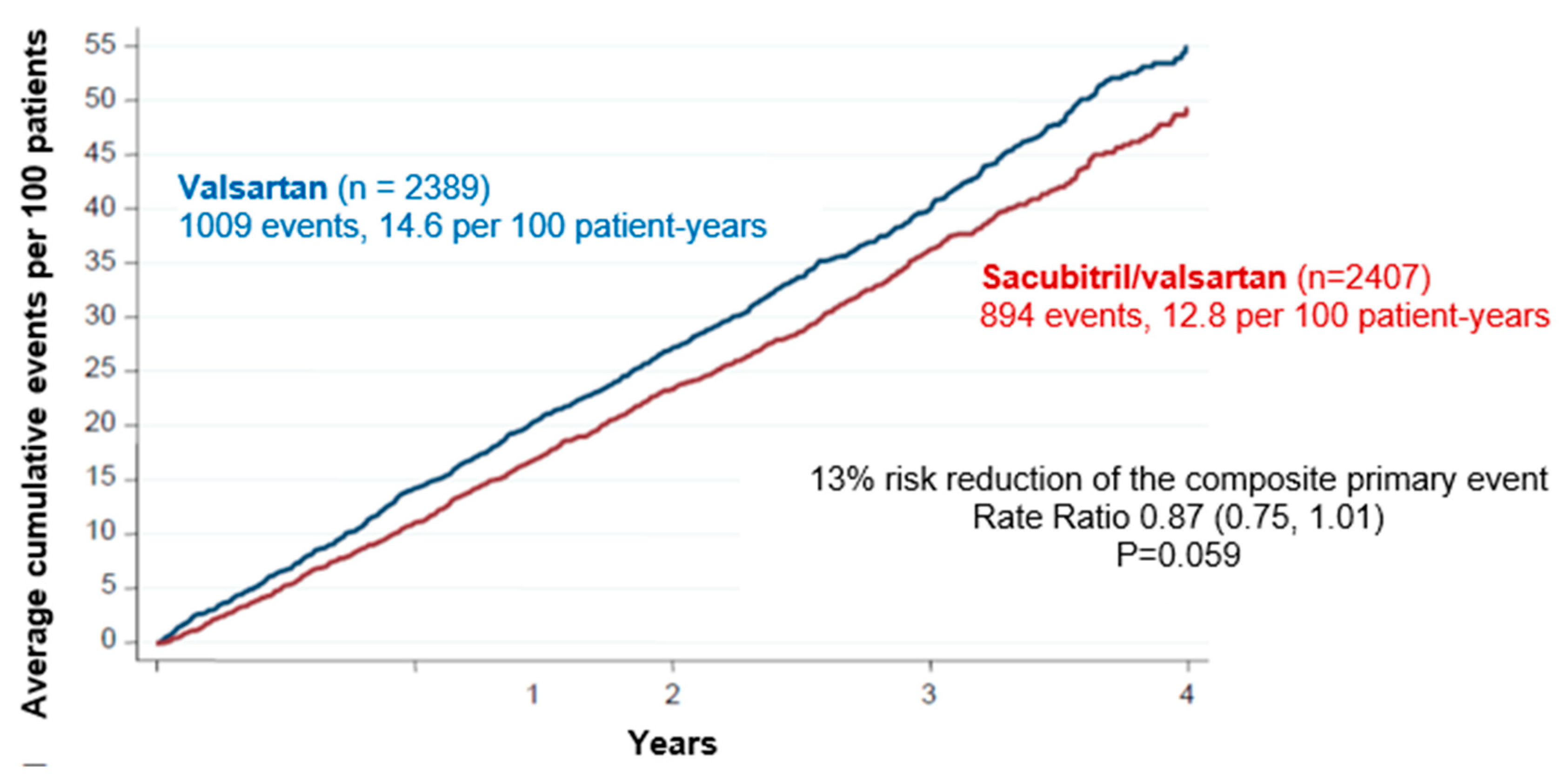

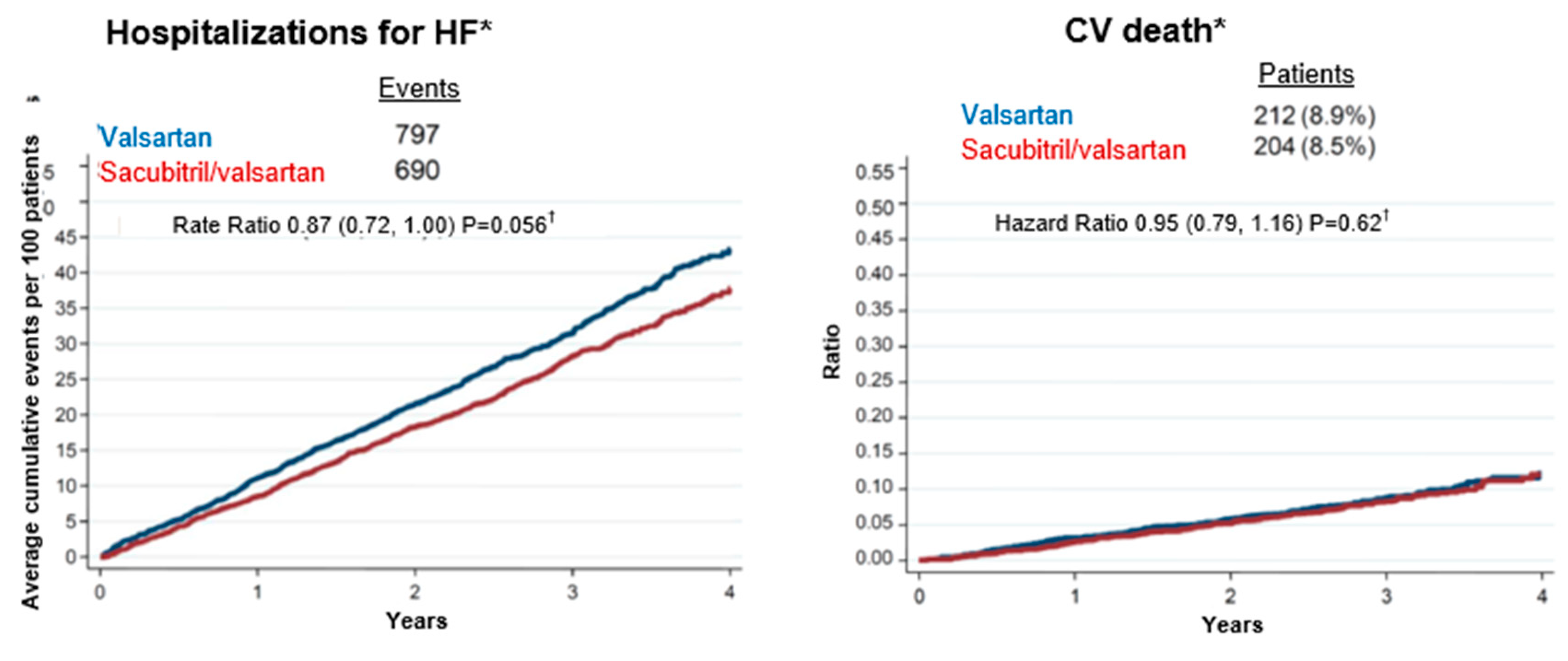

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Anand, I.S.; et al. PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019, 381, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; Claggett, B.; Lewis, E.F.; et al. Influence of ejection fraction on outcomes and efficacy of spironolactone in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, L.H.; Claggett, B.; Liu, J.; et al. Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction in CHARM: Characteristics, outcomes and effect of candesartan across the entire ejection fraction spectrum. Eur J Heart Fail 2018, 20, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; Vaduganathan, M.; LClaggett, B.; Packer, M.; Zile, M.; Swedberg, K.; Rouleau, J.; APfeffer, M.; Desai, A.; Lund, L.H.; Kober, L.; Anand, I.; Sweitzer, N.; Linssen, G.; Merkely, B.; Luis Arango, J.; Vinereanu, D.; Chen, C.H.; Senni, M.; Sibulo, A.; Boytsov, S.; Shi, V.; Rizkala, A.; Lefkowitz, M.; McMurray, J.J.V. Sacubitril/Valsartan Across the Spectrum of Ejection Fraction in Heart Failure. Circulation. 2020, 141, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).