1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an incurable disease that is associated with a high degree of morbidity and mortality. CKD is characterised by an irreversible progressive reduction in kidney function commonly caused by diabetes or hypertension. Current international guidelines define CKD as decreased kidney function demonstrated with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 60mL/min or laboratory measurements that indicate kidney damage that is present for at least 3 months.[

1] In its early stages CKD is normally asymptomatic. However, as the disease progresses, symptoms will develop and eventually resulting in end-stage kidney disease. At this point, the GFR will be less than 15mL/min and the kidneys will be unable to perform necessary functions resulting in uraemia, anaemia, electrolyte imbalances, fluid overload and acidemia and eventually death.[

2] At this point, renal replacement therapy is required. The options are kidney transplantation or dialysis, the latter being the more common approach[

3]. Even with dialysis, there is a significant reduction in the quality and quantity of life, especially in the first year of commencement.[

4] Chronic kidney disease is a very common condition in older people, and it can have significant impact on adverse health outcomes including functional decline, reduced energy intake and sarcopenia, all of which can lead to frailty.[

5,

6] Chronic inflammation, fluid overload, malnutrition, protein wasting, decreased muscle mass and insulin resistance are all common in CKD and make an individual more likely to progress to frailty.[

7]

Frailty is the loss of physiological reserve as we age, which predisposes those affected to increased morbidity and mortality when subjected to stressors. Frailty is common in people with CKD, with more than 60% of dialysis-dependent CKD patients having this condition.[

6] The highest prevalence of frailty is seen in end-stage kidney disease requiring dialysis up to 81% compared to earlier-stage disease not receiving dialysis, which ranged from 2.8 – 16%.[

1] Frailty has been independently associated with increased all-cause mortality, all-cause hospitalisation and falls in patients with CKD.

In Vietnam, the burden of CKD remains high with over 10000 cases per 100000 and 20.6 deaths per 100000.[

8] Due to the alarmingly fast rate of diabetes development in this country (with approximately 5.8 million people with diabetes currently living in Vietnam),[

9,

10] it is likely that the burden of CKD and the costs associated will continue to rise exponentially.[

11] The number of people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has been consistently increasing, with an annual tally of approximately 90,000 patients with ESRD.[

12] However, there is limited evidence on the relationship between frailty and CKD in older people in Vietnam. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the prevalence of frailty and the impact of frailty on mortality in older patients with end-stage renal disease receiving dialysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and Population

This is a prospective, observational, multi-centre study conducted at the Dialysis Centres of Trung Vuong Hospital and Thong Nhat Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam from November 2020 to June 2021. Inclusion criteria included: (1) aged ≥ 60 years, (2) diagnosed with end-stage renal disease and currently on dialysis. Exclusion criteria included: (1) dementia, (2) having mental illness or visual impairment that can affect their ability to answer the study questionnaires, (3) having acute illnesses that required admission, (4) did not provide consent.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (Reference Number 788/2020/HDDD-DHYD, 2/11/2020). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Data collection

Data were collected from patient interviews and medical records. Information obtained included: demographic characteristics, height, weight, medical history, blood test results, and comorbidities. All participants were followed up for 6 months after being included in the study.

2.3. Outcome variables

All-cause mortality: Mortality data were obtained through medical records (for death during hospitalization) and by making phone calls to the phone numbers provided by participants or their caregivers after 6 months. The date and causes of death were documented.

2.4. Predictive variables

Frailty: The predictive variable of interest is frailty. Participants’ frailty status was defined according to the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS).[

13,

14] The CFS score ranges from 1-9, and a score of 4 or greater indicates a frailty status: [

13,

15]

CFS 1 (very fit): People who are robust, active, energetic and motivated. They tend to exercise regularly and are among the fittest for their age.

CFS 2 (fit): People who have no active disease symptoms but are less fit than category 1. Often, they exercise or are very active occasionally.

CFS 3 (managing well): People whose medical problems are well controlled, even if occasionally symptomatic, but often are not regularly active beyond routine walking.

CFS 4 (living with very mild frailty): Previously “vulnerable”, this category marks early transition from complete independence. While not dependent on others for daily help, often symptoms limit activities. A common complaint is being “slowed up”, and/or being tired during the day.

CFS 5 (living with mild frailty): These people often have more evident slowing, and need help with high order instrumental activities of daily living (finances, transportation, heavy housework). Typically, mild frailty progressively impairs shopping and walking outside alone, meal preparation, medications and begins to restrict light housework.

CFS 6 (living with moderate frailty): People who need help with all outside activities and with keeping house. Inside, they often have problems with stairs and need help with bathing and might need minimal assistance with dressing.

CFS 7 (living with severe frailty): Completely dependent for personal care, from whatever cause (physical or cognitive). Even so, they seem stable and not at high risk of dying within 6 months.

CFS 8 (living with very severe frailty): Completely dependent for personal care and approaching end of life. Typically, they could not recover even from a minor illness.

CFS 9 (terminally ill): Approaching the end of life. This category applies to people with a life expectancy less than 6 months, who are not otherwise living with severe frail.

2.5. Covariates

Demographics and lifestyle factors. Age and sex were used as recorded in medical records. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated based on measured weight (kg) and height (m) and was classified into 4 groups: underweight (BMI<18.5 kg/m2), normal (BMI 18.5-22.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 23-24.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI≥ 25.0 kg/m2). Education status was obtained through interview and included the following categories: illiterate, primary school, secondary school, high school, and higher education (college/university). Smoking status was categorised based on self-report as non-smoking or smoking (including current smokers or ex-smokers who stopped smoking less than 1 year ago).

2.6. Comorbidities.

Comorbidities were recorded based on a pre-defined list. Anemia is defined based on hemoglobin (Hb) levels <12.0 g/dL in women and <13.0 g/dL in men.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage, and continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation. Participants were classified into 4 groups according to their CFS score: Group 1 - CFS ≤3 (non-frail), Group 2 - CFS 4-5 (very mildly to mild frail), Group 3 – CFS 6 (moderately frail), and Group 4 – CFS ≥7 (severely to very severely frail). Comparisons among groups were assessed using Chi-square tests or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, and Student’s t-tests for continuous variables. Two-tailed P values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

To compare the time to death among the frailty groups, the Kaplan–Meier estimator was employed to compute survival curves over the 6-month follow-up period, and differences between frailty groups were assessed using the log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards regression was applied to determine whether frailty severity predicts mortality, with the results presented as hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (Cis), adjusted for other potential confounders that showed a significant association with mortality through univariate analysis (with p<0.05). All variables were checked for multicollinearity and interactions. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Sample size justification: Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis on the impact of frailty on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease [

16] and mortality rate in frail older patients in Vietnam [

17], we estimated that a sample size of at least 150 participants to detect of a significant difference in mortality between frail and non-frail patients (assuming mortality rate 5% in non-frail patients and a 4-fold increase in mortality in patients with frailty, at 80% power, 5% significance level, 1-sided test)

3. Results

3.1. General characteristics

A total of 175 participants were recruited. They had a mean age of 72.4 ± 8.5 years, and 58.9% were female. Participant characteristics were presented in

Table 1.

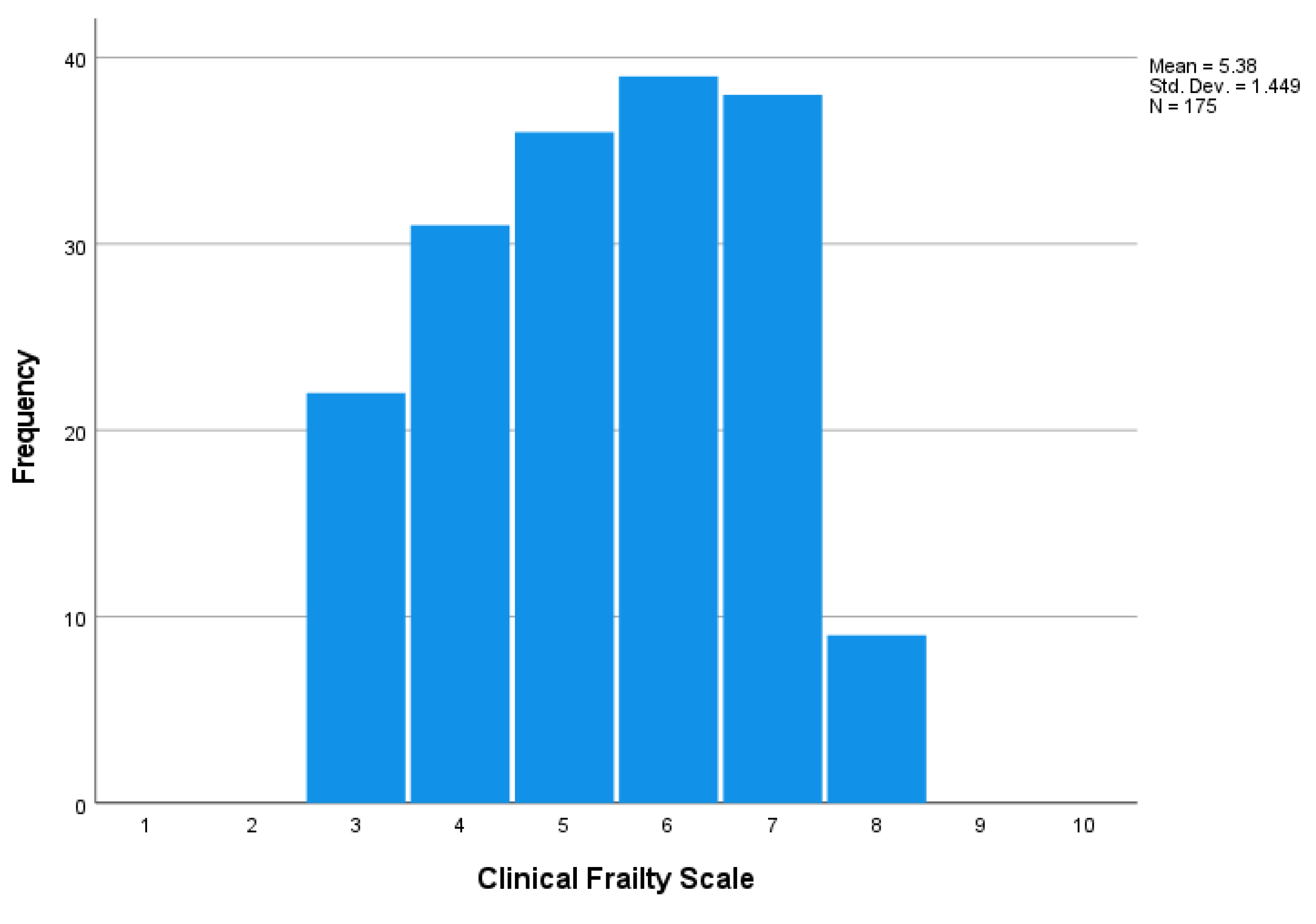

Figure 1 presents the distribution of the CFS score among the study participants. The median CFS score was 5 (range from 3 to 8). Using the cut-point of CFS ≥4, 87.4% of the participants were frail (38.3% were very mildly/mildly frail, 22.3% were moderately frail, and 26.9% were severely/very severely frail).

Compared to the non-frail participants (CFS ≤3), the frailer participants were older and had a higher burden of chronic diseases, particularly diabetes, heart failure, stroke, peripheral artery disease and cancer (

Table 1).

3.2. Mortality rate at the 6th month

After 6 months, 14.9% (26/175) of the participants died. The leading known cause of death was infection (53.8%), followed by acute myocardial infarction (7.7%) and strokes (7.7%).

The mortality rate was significantly higher in the frailer group compared to the non-frail: 31.9% in participants with CFS score≥7, 12.8% in participants with CFS=6, 7.5% in participants with CFS score from 4 to 5, and 4.5% in participants with CFS score ≤3 (p=0.001)

3.3. The impact of frailty on mortality

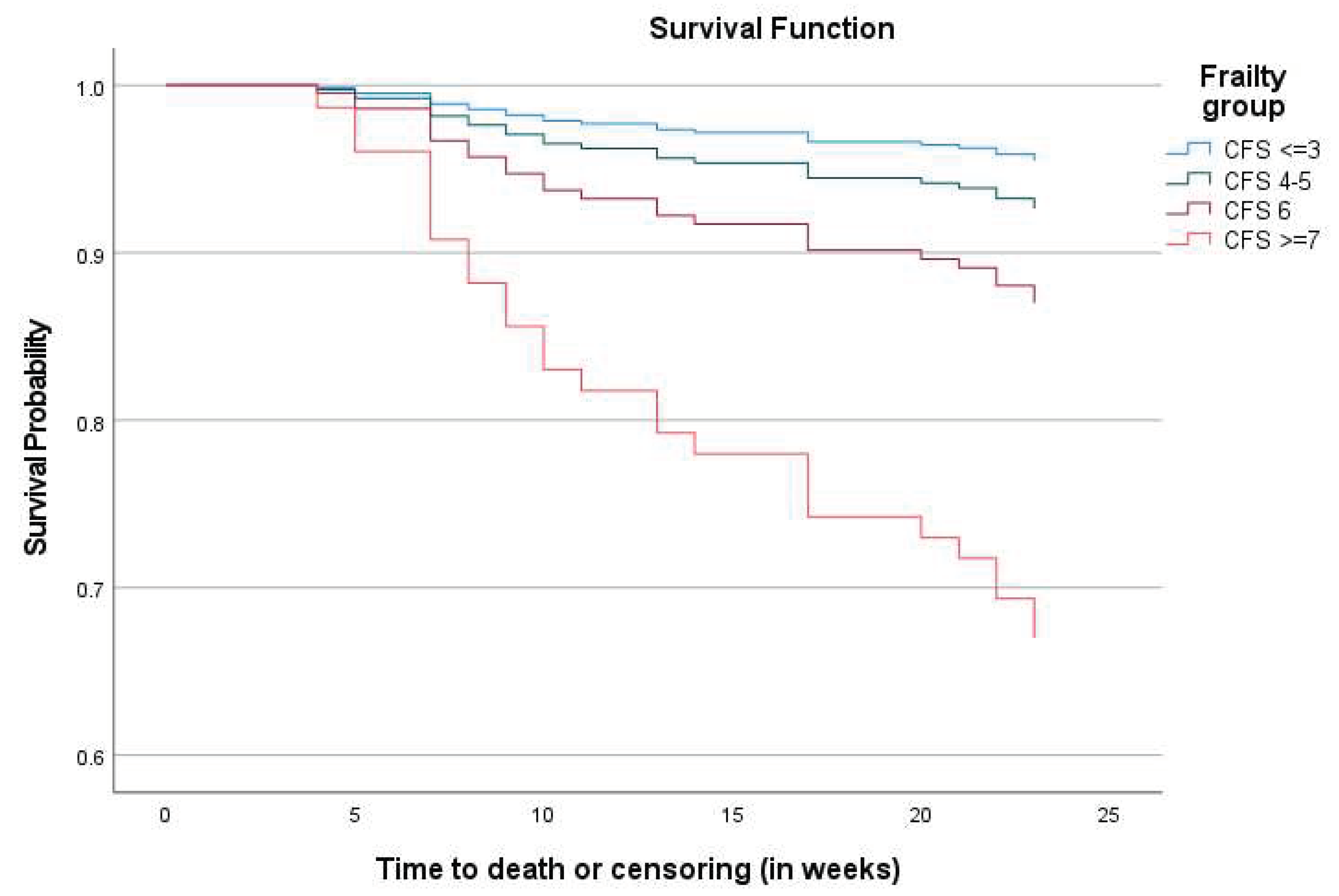

Figure 2 presents the survival curves for all-cause mortality across the frailty groups. The Kaplan-Meier survival function for mortality indicated that at all points during the six-month follow-up, frailer participants had a higher probability of dying than the non-frail. (Log Rank Chi-Square 18.07, 3df, p <0.001 and Breslow Chi-Square 19.16, 3df, p <0.001)

Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that compared to the non-frail participants, the probability of death over 6 months was nearly 2-fold higher in the mildly frail, 3-fold higher in the moderately frail, and 9-fold higher in the severely frail participants. The association between frailty and mortality remained significant after adjusting for the potential confounders (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

In this study in 175 older patients with end-stage renal disease and on chronic dialysis, the prevalence of frailty was very high (87.4%). We found that frailty independently predicted mortality in 6 months after discharge in this population.

Our finding aligned with findings from studies in older patients with chronic dialysis. A recent systematic review of 32 studies (n=36,076, age range: 50-83 years) showed that the prevalence of frailty ranged from 7% in people with CKD Stages 1-4 to 73% in people on haemodialysis.[

18] Other studies showed that frailty was present in 43% of patients with severe CKD, 54% in pre-dialysis patients and ranged from 30% to 82% among dialysis patients depending on the study settings and frailty assessment tools.[

19] In another meta-analysis by Mei and colleagues in 18 cohort studies with 22,788 participants, the median reported prevalence of frailty in people with CKD was 41.8% (range 2.8-81.5%) and frailty increased mortality risk (pooled HR 1.48, 95% CI 1.21-1.81,

P < 0.001).

Several tools are available to screen for frailty in older adults. While the Frailty Phenotype and the Frailty Index were applied in most of the studies, the CFS has been increasingly used recently in patients with CKD.[18-20] In a study conducted by Clark and colleagues in 564 patients with chronic dialysis, frailty was assessed by the CFS. The authors found that compared to participants with CFS ≤3, those with CFS 4-5 had a 60% increased risk of readmission (HR 1.60, 95%CI 1.09-2.35), and those with CFS 6-7 had a 93% increased risk of readmission (HR 1.93, 95%CI 1.16-3.22) [

21]. Yoshida and colleagues used the CFS to evaluate frailty in 310 patients aged 75 plus with CKD who initiated dialysis and found that frailty was present in 33.2% of the cohort, and the HR for mortality in frail participants versus non-frail was 1.59 (95% CI 1.10–2.58, p < 0.001).[

22] In fact, the CFS has been recommended for frailty screening programs within nephrology services, particularly in patients with advanced CKD due to its accuracy in frailty screening.[

20]

4.1. Strengths and limitations of our study

To our best understanding, this is the first study in Vietnam to investigate frailty in older patients with end-stage renal disease and dialysis. The study was conducted at two large dialysis centers in Vietnam. However, our follow-up duration was only 6 months, and information on readmission and other important adverse events such as falls was not well documented. Further studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow up are needed to understand the impact of frailty on adverse outcomes and quality of life in older patients with end-stage renal disease and dialysis. The study was designed and powered to investigate the impact of frailty on mortality, hence we do not have enough data to examine the risk factors associated with frailty. Further studies are needed to identify the risk factors for developing frailty in patients with CKD in Vietnam. Understanding these risk factors is important in clinical practice as it can help clinicians identify those patients at a higher risk of developing frailty, thus enabling early intervention to prevent or delay its onset.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a very high prevalence of frailty in older patients with end-stage renal disease and dialysis and the significant impact of frailty severity on mortality. Our study highlights the need to screen for frailty in older patients with end-stage renal disease and dialysis. Screening for frailty in older patients with end-stage renal disease and dialysis has several implications for clinical practice. First, it can help identify older patients who are at high risk for adverse outcomes, such as mortality, falls and readmission. These high-risk patients can then be targeted for interventions aiming at improving their health outcomes, such as exercise programs, nutritional support, social support and medication review. Second, frailty screening may help healthcare providers and patients make shared decisions about treatment goals and preferences. More research is needed to determine the most effective interventions for frailty in this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tan Nguyen and Tu Nguyen; Data curation, Tan Nguyen and Thu Pham; Formal analysis, Tan Nguyen, Thu Pham, Mason Burns and Tu Nguyen; Investigation, Tan Nguyen, Thu Pham and Tu Nguyen; Methodology, Tan Nguyen, Thu Pham, Mason Burns and Tu Nguyen; Project administration, Tan Nguyen and Thu Pham; Resources, Tan Nguyen and Thu Pham; Software, Tan Nguyen, Thu Pham, Mason Burns and Tu Nguyen; Supervision, Tan Nguyen; Validation, Tan Nguyen and Tu Nguyen; Visualization, Tan Nguyen, Thu Pham, Mason Burns and Tu Nguyen; Writing – original draft, Tan Nguyen, Mason Burns and Tu Nguyen; Writing – review & editing, Tan Nguyen, Thu Pham, Mason Burns and Tu Nguyen.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants for their participation in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Mei, F.; Gao, Q.; Chen, F.; Zhao, L.; Shang, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, B.; Ma, B. Frailty as a Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2021, 22, 535–543.e537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Jafar, T.H.; Nitsch, D.; Neuen, B.L.; Perkovic, V. Chronic kidney disease. The Lancet 2021, 398, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.K.; Levin, A.; Lunney, M.; Osman, M.A.; Ye, F.; Ashuntantang, G.E.; Bellorin-Font, E.; Benghanem Gharbi, M.; Davison, S.N.; Ghnaimat, M.; et al. Status of care for end stage kidney disease in countries and regions worldwide: international cross sectional survey. BMJ 2019, 367, l5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Streja, E.; Rhee, C.M.; Soohoo, M.; Chen, J.L.T.; Molnar, M.Z.; Obi, Y.; Gillen, D.; Nguyen, D.V.; et al. Transition of care from pre-dialysis prelude to renal replacement therapy: the blueprints of emerging research in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2017, 32, ii91–ii98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallappallil, M.; Friedman, E.A.; Delano, B.G.; McFarlane, S.I.; Salifu, M.O. Chronic kidney disease in the elderly: evaluation and management. Clin Pract (Lond) 2014, 11, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, A.C.; Bampouras, T.M.; Pendleton, N.; Woywodt, A.; Mitra, S.; Dhaygude, A. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: current evidence and continuing uncertainties. Clin Kidney J 2018, 11, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.C.; Kennedy, C.C.; Rule, A.D.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Kirkland, J.L.; Hickson, L.J. Frailty in CKD and Transplantation. Kidney International Reports 2021, 6, 2270–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikbov, B.; Purcell, C.A.; Levey, A.S.; Smith, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abebe, M.; Adebayo, O.M.; Afarideh, M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Agudelo-Botero, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc, N.B.; Lin, Z.L.; Ahmed, W. Diabetes: What Challenges Lie Ahead for Vietnam? Ann Glob Health 2020, 86, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khue, N.T. Diabetes in Vietnam. Ann Glob Health 2015, 81, 870–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyodo, T.; Fukagawa, M.; Hirawa, N.; Isaka, Y.; Nakamoto, H.; Van Bui, P.; Thwin, K.T.; Hy, C. Present status of renal replacement therapy in Asian countries as of 2017: Vietnam, Myanmar, and Cambodia. Renal Replacement Therapy 2020, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.Q.; Nguyen, N.T.Y.; Nguyen, B.; Bui, Q.T.H. Quality of life assessment in patients on chronic dialysis: Comparison between haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis at a national hospital in Vietnam. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2022, 27, 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitnitski, A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, E.; Lien, C.; Lim, W.S.; Wong, W.C.; Wong, C.H.; Ng, T.P.; Woo, J.; Dong, B.; de la Vega, S.; Hua Poi, P.J.; et al. The Asia-Pacific Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Frailty. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017, 18, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehlmann, C.A.; Nickel, C.H.; Cino, E.; Al-Najjar, Z.; Langlois, N.; Eagles, D. Frailty assessment in emergency medicine using the Clinical Frailty Scale: a scoping review. Intern Emerg Med 2022, 17, 2407–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, F.; Gao, Q.; Chen, F.; Zhao, L.; Shang, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, B.; Ma, B. Frailty as a Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021, 22, 535–543.e537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, T.X.; Nguyen, T.N.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Pham, T.; Cumming, R.; Hilmer, S.N.; Vu, H.T.T. The impact of frailty on prolonged hospitalization and mortality in elderly inpatients in Vietnam: a comparison between the frailty phenotype and the Reported Edmonton Frail Scale. Clin Interv Aging 2019, 14, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Peel, N.M.; Krosch, M.; Hubbard, R.E. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2017, 68, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennard, A.; Glasgow, N.; Rainsford, S.; Talaulikar, G. Frailty in chronic kidney disease: challenges in nephrology practice. A review of current literature. Internal Medicine Journal 2023, 53, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, A.C.; Bampouras, T.M.; Pendleton, N.; Mitra, S.; Dhaygude, A.P. Diagnostic Accuracy of Frailty Screening Methods in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephron 2019, 141, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.; Matheson, K.; West, B.; Vinson, A.; West, K.; Jain, A.; Rockwood, K.; Tennankore, K. Frailty Severity and Hospitalization After Dialysis Initiation. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2021, 8, 20543581211023330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Takanashi, Y.; Harigai, T.; Sakurai, N.; Kobatake, K.; Yoshida, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Ueki, K. Evaluation of frailty status and prognosis in patients aged over 75 years with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Renal Replacement Therapy 2020, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).