1. Introduction

Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents is approximately 0.02%-0.1% of elective pediatric surgeries [

1]. Although aspiration usually occurs anesthesia induction, in patients with comorbidities and/or emergency surgery, it can also be seen tracheal extubation and recovery period [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Hypoxia, pneumonia and prolonged mechanical ventilation may develop after pulmonary aspiration [

9].

Increased gastric content volume, causes regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration, can be evaluated by ultrasound [

10]. Gastric bedside ultrasound (POCUS) is safe, noninvasive, bedside technique allows evaluation of gastric content and volume in patients, recommended by the European Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care [

11,

12]. It can improve our knowledge of gastric emptying in patients, clinical situations and thereby help to identify possible predictive factors for risky gastric content [

1,

13,

14]. The mainstay of aspiration prevention has been standardized nil per os (NPO) guidelines, but the variability of gastric emptying among patients, comorbidities, and uncertain NPO status may constitute a risk [

15]. Current standard of care is based on patient/parent discourse of last oral intake; this is prone to all kinds of inaccuracies and requires a careful and communicative patient/parent. Studies shown that the perception of time is weak, especially in preoperative phase, related to the increased stress of parents [

16,

17]. This raises doubts about the accuracy of the data. In the region we live in, often worried about regurgitation of gastric contents and pulmonary aspiration in pediatric patients, especially since provided health services to patient groups with low socioeconomic status, immigrants, and who are ineffective communicators.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of 'risky stomach' defined by ultrasound imaging of solid contents and/or calculated gastric fluid volume >1.25 mL/kg in elective surgery. We also aimed to compare this definition with the 0-2 qualitative rating scale used to distinguish between "empty" and "risky stomach ".

2. MATERIAL AND METHOD

2.1. Study Design

This prospective study was conducted between February 2020-November 2021 after written informed consent from the parent and/or patient and approval of the SBU Bursa Yüksek İhtisas Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee (2011-KAEK-25 2019/12-09). Age, gender, weight, height, medical/surgical history, medications and expiration times, allergies, and last oral intake time separately for clear and thick liquids and solid foods noted.

2.2. Identification of Patients

One hundred ASA I-II patients aged 2-18 years scheduled for elective surgery under general anesthesia were enrolled. Gastrointestinal disease history and/or functional impairment, previous esophageal or upper abdominal surgery, or those who could not be given the right lateral decubitus (RLD) position to obtain gastric POCUS measurements were excluded from the study.

In our hospital, children who were routinely scheduled for elective surgery were allowed to have clear liquids up to 2 hours prior to the induction of anesthesia, breast milk up to 4 hours before, and to drink milk, formula and eat light meals up to 6 hours before, in accordance with current guidelines [

18].

2.3. Ultrasound Examination of the Gastric Antrum

All ultrasonographic evaluations of the gastric antrum were performed by a single investigator (AD) who was blinded to the clinical history of the patients and had performed at least 100 previous gastric ultrasound examinations before. The examination was performed with an ultrasound (GE

®, Healthcare LOGIQ™ e series, USA) in the operating room just prior to the induction of general anesthesia. The children were first placed in supine and then in the RLD position, and a low frequency (2-5 MHz) convex abdominal probe, or if the antrum was <3 cm from the skin surface, a high frequency linear probe (5-12 MHz) was used. The gastric antrum was scanned in a standard sagittal plane in the epigastrium, including the left lobe of the liver and the aorta or inferior vena cava, as previously described [

19,

20].

Qualitative assessment of gastric antrum content was made using a 3-point qualitative rating scale described by Perlas et al. [

21]. Grade 0 was defined as the absence of any content in a flat antrum in both the supine and right lateral decubitus positions. Grade 1 indicated the appearance of the fluid content in the right lateral decubitus position only, and grade 2 indicated the appearance of the fluid content in both the RLD and the supine position.

The maximum antero-posterior (D1) and longitudinal diameters (D2) of the antrum were measured from serosa to serosa in the RLD position, and the antral cross-sectional area (CSA) calculated with the formula: antral CSA (cm

2) = (π × D1 × D2) /4) [

22]. Gastric volume was then calculated using a mathematical model previously validated in the pediatric population: volume (ml.kg

-1) = -7.8 + (3.5 x CSA (cm

2)) + (0.127 x age {month}) / body weight (kg) [

19]. The R² value for this model was 0.60 [

19]. No examination was performed during peristaltic movements of the antrum. “Risky stomach” indicated the visualization of any solid, echoic content in the antrum and/or gastric fluid volume > 1.25 ml/kg [

19,

23] and “full stomach” indicated any solid, echoic content visualization in the antrum and/or a calculated gastric fluid volume of >1.5 ml.kg

-1 [

24,

25]. The cut-off value of >1.25 ml/kg is recommended in children for the definition of a “risky stomach " [

19,

23]. Calculated gastric content volumes of >0.8, >1, and >1.5 ml/kg were suggested to show “empty,” “risky stomach,” and “full stomach,” respectively [

13,

21,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Since the boundaries between normal, upper normal, and increased gastric volume are unclear, the prevalence of cut-off values was also calculated, and gastric measurements of each child was completed in a maximum of 5 minutes.

Demographic data (age, gender, weight, height, body mass index and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical condition classification), solid food, viscous and clear liquid fasting times, type of surgery (ear, nose and throat surgery, urogenital surgery, orthopedic surgery, pediatric surgery) and complications such as regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration were recorded.

2.4. Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data are presented in numbers and percentages, while categorical data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, interquartile range and minimum-maximum values. The Fisher test was used to compare categorical data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and histogram graphs were used to examine the assumption of normal distribution. Since the data did not show a normal distribution, the Friedman test was used for the comparison of the data and the Kruskal Wallis test was utilized for inter-group analyses. Spearman correlation analysis was used to examine the correlation of data. P<0.05 indicated statistical significance. Bonferroni correction was applied for the p value in Post Hoc analyses. All analyses were performed with the SPSS 20 program.

Although no power analysis was made when the study was planned, a post hoc power analysis was conducted to examine whether the number of samples included in the study was sufficient during analysis. The effect sizes calculated from the mean antral CSA and gastric volume values measured in RLD position are as follows for all three grades: With an effect value of F: 1.49, F:0.93, and a %5 alpha error value, the study power was over 99.9% in all analyses with 97 patients. Analyses were carried out using the G*Power 3.1 Program.

3. RESULTS

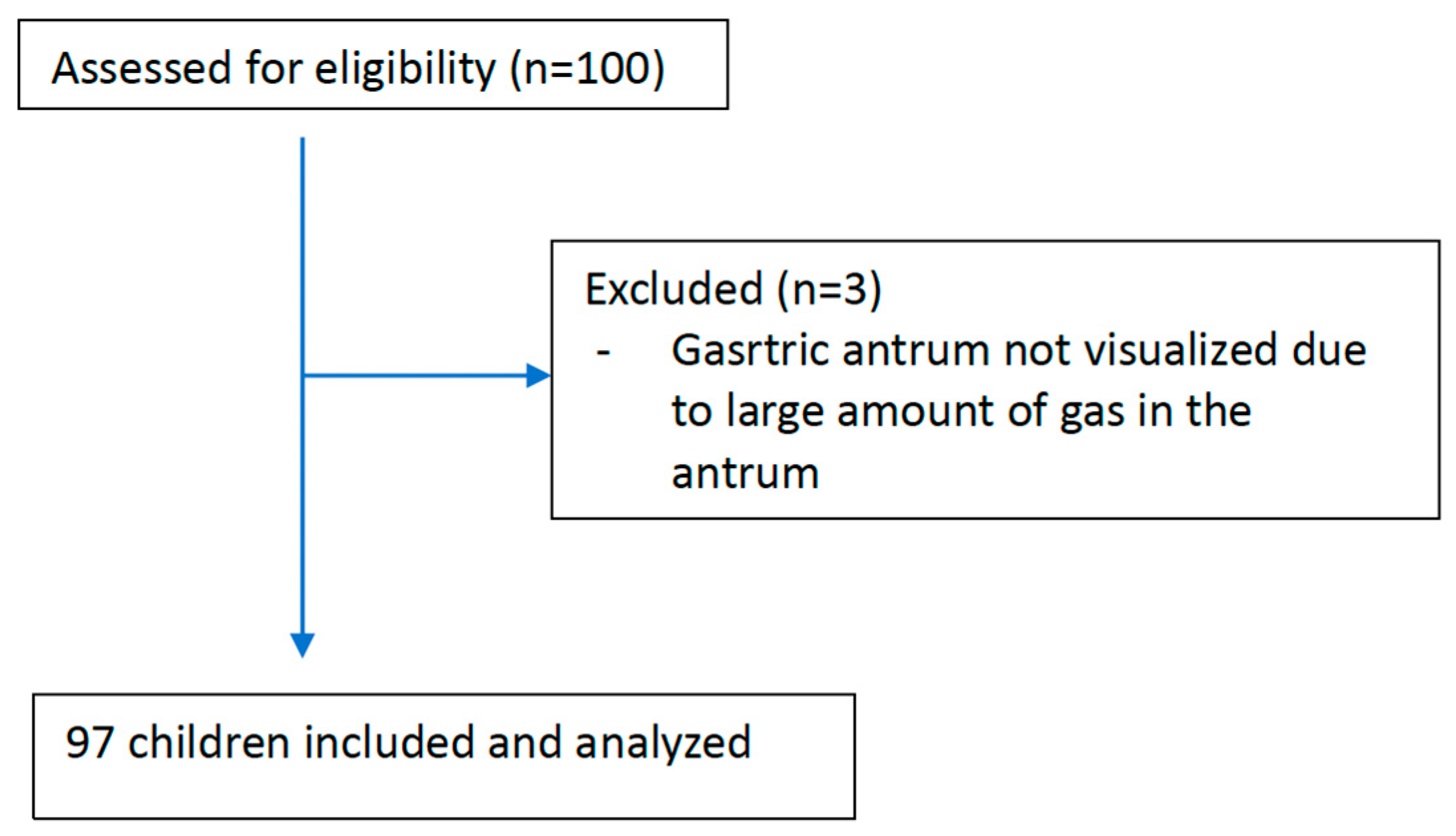

One hundred patients included in the study, and three patients excluded because of insufficient evaluation due to the dense amount of gas in the antrum. Evaluation was performed on 97 children (95% CI: 92.2%-99.1%) (

Figure 1).

In the study, 30 (30.9%) were female and 67 (69.1%) were male; 18 (17.46%) children aged 2 to <3 years, 30 (29.1%) children aged 3 to <6 years, 27 children (26.19%) aged 6 to <12 years, and 22 (21.34%) between 12-18 years of age. Among them, 90.7% ASA I and 9.3% ASA II. Pediatric surgery operations were the most common (85.6%). No echoic, solid, or viscous liquid content was found in any of the patients, and gastric volume was <1.5 ml.kg

-1 in all patients during the ultrasonography of the antrum. Fifty-five children (56.7%) had Grade 0, 37 (38.1%) had Grade 2 and 5 (5.2%) had Grade 2 antrum (

Table 1).

The median (interquartile range) antral CSA was 2.36 (1.44-4.20) cm² in the RLD position. The corresponding median gastric volume was 0.46 (0.33-0.72) mL/kg (

Table 2). The median fasting time was 9 hours for solid thick liquids and 4 hours for clear liquids. Solid food fasting time was prolonged up to 12 hours (

Table 2).

The relationship between the qualitative antrum grade 0-2 and the antral CSA measured in the RLD position, and the corresponding stomach volume is presented in

Table 3. Gastric fluid volume calculated per unit weight was significantly higher in children with Grade 1 and Grade 2 antrums compared to those with Grade 0 antrum (

Table 3).

The distribution of children calculated gastric fluid volume >0.8, >1, >1.25 and >1.5 mL/kg by antral degree is presented in

Table 4. For a child with both antrum grade 0 and gastric fluid volume >0.8 mL/kg, the gastric fluid volume was <1 mL/kg. Gastric fluid volume was >1.25 mL/kg in only one child (

Table 4). This patient was scheduled for ASA I and laparoscopic inguinal hernia operation and had a fasting period of 10 hours for solid food and 2 hours for clear liquids prior to ultrasound measurement. The "risky stomach" fullness rate in the study group was 1% (95% CI: 0.1%-4.7%). The prevalences of children with gastric fluid volume >0.8, >1.0, and >1.5 mL/kg were 19.6% (95% CI: 12.6%-28.3%), %6.2 (%95 CI: %2.6-%12.3), and %0.0 (

Table 4).

In patients with grade 0 antrum, there was a moderate and positive correlation (Rho:0.542 (p<0.001)) between antral RLD CSA and BMI, and a strong and positive correlation between antral RLD CSA and age (Rho:0.796 (p<0.001)) (

Table 5). A strong and positive correlation existed between antral RLD CSA and age in patients with grade 1 antrum (Rho:0.622 (p<0.001)) (

Table 5). No regurgitation or pulmonary aspiration was observed.

4. DISCUSSION

In our study, stomach content and volume were evaluated by ultrasound in 97% of children, of which 5.2% had Grade 2 antrum. In the RLD position, antral CSA was 2.36 (1.44-4.20) cm², and the median calculated gastric volume was 0.46 (0.33-0.72) mL/kg. While the median solid food and thick liquid fasting time was 9 hours, the median clear liquid fasting time was 4 hours, and solid food fasting time extended up to 12 hours. In patients with grade 0 antrum, a moderate and positive correlation was found between antral CSA and BMI, and a strong and positive correlation was seen between antral CSA and age. There was a strong and positive correlation between antral CSA and age in patients with grade 1 antrum. We showed that only 0.1%-4.7% of elective surgery children had gastric fluid volumes of >1.25 mL/kg, implying a "risky stomach" with a potentially increased risk for pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents [

25].

Apart from gastric fluid volume, factors such as gastric distension by insufflation of air to stomach during anesthesia induction, difficulties in airway management, contraction or coughing related to inappropriate anesthesia technique also play a role in pathophysiology of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents [

4]. However, some studies show that the risk of gastric contents aspiration may increase independent of other risks [

2,

3].

In studies, antral CSA measured both supine and RLD positions, but for completing the measurements shortly, we preferred to measure antral CSA in RLD, which is the main determinant according to various mathematical calculations [

19,

29,

30,

31].

A study using the three-position blind aspiration technique; found that the mean gastric fluid volume 0.4 ± 0.45 mL/kg and 95% of these children had <1.25 mL/kg [

23]. However, the volume of gastric contents assessed by nasogastric aspiration increased in 46% of children undergoing emergency surgery [

32]. In our study, the percentage of children with gastric fluid volume >1.25 mL/kg was lower than those with gastric fluid volumes of >0.8 and >1 mL/kg. These results support that gastric fluid volume of >1.25 mL/kg is not common in electively fasted children and can be used as a critical cut-off value to between normal and increased gastric fluid volume in children, like previous studies [

19,

23]. In addition, calculated mean gastric fluid volume was similar with volume aspirated blindly in children scheduled for elective surgery and volume calculated in healthy volunteers using magnetic resonance [

22,

33,

34].

To target the elective pediatric population where preoperative ultrasound of gastric contents would be most effective, further studies should be conducted to identify risk factors that contribute to increased gastric contents volume. In our study, five children (5.2%) had grade 2 antrum, while Desranges et al. reported the incidence of grade 2 antrum as 9.1%, and Spencer et al. reported the incidence of grade 2 antrum in children scheduled for elective upper gastrointestinal endoscopy as 9% [

19,

28]. This high incidence can be explained by inclusion of children with gastrointestinal complaints such as inflammatory bowel disease or gastroesophageal reflux in another study [

19]. Although our results show that use of 0-2 qualitative rating scale may not be precise to distinguish between "risky stomach" and "empty stomach" in children, it supports the incidence of elective patients with grade 2 antrum between 3% and 5% [

13,

21].

In addition, the fasting times in our study were much longer than current guidelines, as in most clinical practices [

19,

35,

36]. The causes of prolonged fasting may be related to the slow change in practice or the inability to perform early in the morning. Shorter fasting periods, if possible, have recently been recommended various pediatric anesthesia societies [

37,

38,

39]. Protocols for fasting time have a good safety record in terms of low aspiration and regurgitation, but often cause excessive fasting times, thirst, and discomfort [

36]. Also, several articles shown that the 2-hour clear liquid fasting rule translates to median fasting times of 6 to 13 hours in the real world [

40,

41]. In our study, the median duration of clear liquid fasting was 4 hours, and the median solid fasting time was 9 hours. Contrary to expected, prolonging the fasting period is not beneficial for reducing gastric fluid volume, but prolonged thirst and fasting may lead to significant preoperative agitation, peroperative hypotension, and ketone body accumulation [

36,

42,

43,

44]. Regardless of the fasting regimen and the actual duration of fasting, keep in mind that the risk of regurgitation or aspiration is present with any sedation/general anesthetic and increased risk in emergencies and child with gastrointestinal obstruction.

5. Limitations

Our study is single-center and needs larger case numbers. Gastric content volume was not measured directly but calculated by ultrasound. In elective surgery children, it is impossible using invasive methods like gastric tube to measure gastric content before anesthesia. In addition, blind aspiration does not ensure all gastric contents removing from the stomach and therefore may give an imprecise measurement. Other noninvasive methods for gastric volume, such as gastric tomodensitometry or magnetic resonance, have also not been very applicable in the elective surgery, for both ethical and practical reasons. These tools have limitations and are not definitive methods for gastric content volume. Another point to consider is that all ultrasound examinations in this study were performed by the same investigator. However, several previous studies have shown that ultrasound and measurement of antral CSA allow accurate assessment of gastric volume and content in healthy individuals, in adult and pediatric patients surgery [

13,

19,

21,

25,

26,

29,

31] with high intra- and inter-rater reliability [

45].

6. CONCLUSION

One of the most feared and mortal complications of general anesthesia, 'risky stomach' and pulmonary aspiration should not be neglected even in the elective pediatric surgery group. We think that the evaluation of gastric contents by ultrasound; is noninvasive, bedside and easy-to-apply method, can be preferred in routine practice to determine the risk in every patient, to take necessary precautions and exclude unknown risk factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and Ş.E.Ö; Data curation, A.D., Ş.E.Ö, Ş.E., M.G.; Formal analysis, A.N.B. and T.O.; Investigation, A.D., Ş.E. and M.G.; Methodology, A.D., Ş.E.Ö, T.O., A.N.B and M.G.; Project administration, A.D., N.K., Ş.E., T.O. and A.N.B.; Software, A.D.; Supervision, Ş.E.Ö.; Validation, A.D., Ş.E.Ö., A.N.B., N.K. and M.G.; Visualization, Ş.E. and T.O.; Writing— original draft, A.D., T.O., Ş.E.Ö., and Ş.E.; Writing—review and editing, A.D., T.O., A.N.B., N.K. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Health Sciences University, Bursa Yüksek İhtisas Research and Training Hospital number 2011-KAEK-25 2019/12-09.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were informed of the proposed study methods; a verbal and an informed written consent document was signed by those who agreed to participate.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express deep gratitude to all families and staff of Health Sciences University, Bursa Yüksek İhtisas Research and Training Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bouvet, L.; Bellier, N.; Gagey-Riegel, A.-C.; Desgranges, F.-P.; Chassard, D.; Siqueira, M.D.Q. Ultrasound assessment of the prevalence of increased gastric contents and volume in elective pediatric patients: A prospective cohort study. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2018, 28, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland LM, Sereika SM, Woelfel SK, et al. Pulmonary aspiration in pediatric patients during general anesthesia: incidence and outcome. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia 1998; 10: 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Lee, S.Y. Pulmonary aspiration under GA: a 13-year audit in a tertiary pediatric unit. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2016, 26, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.W. Pulmonary aspiration in pediatric anesthetic practice in the UK: a prospective survey of specialist pediatric centers over a one-year period. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2013, 23, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Tm, C.; N, W.; C, F.; Project, F.N.A. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 1: anaesthesia.. 2015, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook TM, Frerk C. Chapter 19: aspiration of gastric contents and of blood. In: Cook TM, Woodall N, Frerk C, eds. Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and Difficult Airway Society. Major Complications of airway management in the United Kingdom. Report and Findings. London: Royal College of Anaesthetists, 2011: 155–64.

- Warner, M.A.; Warner, M.E.; Warner, D.O.; Warner, L.O.; Warner, E.J. Perioperative Pulmonary Aspiration in Infants and Children. Surv. Anesthesiol. 1999, 43, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiret, L.; Nivoche, Y.; Hatton, F.; Desmonts, J.M.; Vourc'H, G. Complications related to anaesthesia in infants and children. Br. J. Anaesth. 1988, 61, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habre, W.; Disma, N.; Virág, K.; Becke, K.; Hansen, T.G.; Jöhr, M.; Leva, B.; Morton, N.S.; Vermeulen, P.M.; Zielinska, M.; et al. Incidence of severe critical events in paediatric anaesthesia (APRICOT): a prospective multicentre observational study in 261 hospitals in Europe. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, T.; Webster, N.R. Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents in anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 1999, 83, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlas, A.; Chan, V.W.S.; Lupu, C.M.; Mitsakakis, N.; Hanbidge, A. Ultrasound Assessment of Gastric Content and Volume. Anesthesiology 2009, 111, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frykholm, P.; Disma, N.; Andersson, H.; Beck, C.; Bouvet, L.; Cercueil, E.; Elliott, E.; Hofmann, J.; Isserman, R.; Klaucane, A.; et al. Pre-operative fasting in children. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2022, 39, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvet, L.; Desgranges, F.-P.; Aubergy, C.; Boselli, E.; Dupont, G.; Allaouchiche, B.; Chassard, D. Prevalence and factors predictive of full stomach in elective and emergency surgical patients: a prospective cohort study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017, 118, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evain, J.-N.; Durand, Z.; Dilworth, K.; Sintzel, S.; Courvoisier, A.; Mortamet, G.; Desgranges, F.-P.; Bouvet, L.; Payen, J.-F. Assessing gastric contents in children before general anesthesia for acute extremity fracture: An ultrasound observational cohort study. J. Clin. Anesthesia 2021, 77, 110598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boretsky, K.R.; Perlas, A. Gastric Ultrasound Imaging to Direct Perioperative Care in Pediatric Patients: A Report of 2 Cases. A&A Pr. 2019, 13, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, G.; Berkowitz, C.D.; Lewis, R.J. Parental Recall After a Visit to the Emergency Department. Clin. Pediatr. 1994, 33, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C.; Shulman, V.; Khine, H.; Avner, J.R. Parental Perception of the Passage of Time During a Stressful Event. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2007, 23, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:376-393.

- Spencer, A.O.; Walker, A.M.; Yeung, A.K.; Lardner, D.R.; Yee, K.; Mulvey, J.M.; Perlas, A. Ultrasound assessment of gastric volume in the fasted pediatric patient undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: development of a predictive model using endoscopically suctioned volumes. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2014, 25, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagey, A.-C.; Siqueira, M.d.Q.; Desgranges, F.-P.; Combet, S.; Naulin, C.; Chassard, D.; Bouvet, L. Ultrasound assessment of the gastric contents for the guidance of the anaesthetic strategy in infants with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: a prospective cohort study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 116, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlas A, Davis L, Khan M, et al. Gastric sonography in the fasted surgical patient: a prospective descriptive study. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:93-97. [CrossRef]

- Bouvet L, Miquel A, Chassard D, Boselli E, Allaouiche B, Benhamou D. Could a single standardized ultrasound measurement of antral area be of interest for assessing gastric contents? A preliminary report. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 2009; 26: 1015–9. [CrossRef]

- Cook-Sather, S.D.; Liacouras, C.A.; Previte, J.P.; Markakis, D.A.; Schreiner, M.S. Gastric fluid measurement by blind aspiration in paediatric patients: A gastroscopic evaluation. Can. J. Anaesth. 1997, 44, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Putte, P.; Vernieuwe, L.; Jerjir, A.; Verschueren, L.; Tacken, M.; Perlas, A. When fasted is not empty: a retrospective cohort study of gastric content in fasted surgical patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017, 118, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlas, A.; Van de Putte, P.; Van Houwe, P.; Chan, V.W.S. I-AIM framework for point-of-care gastric ultrasound. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015, 116, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvet, L.; Mazoit, J.-X.; Chassard, D.; Allaouchiche, B.; Boselli, E.; Benhamou, D. Clinical Assessment of the Ultrasonographic Measurement of Antral Area for Estimating Preoperative Gastric Content and Volume. Anesthesiology 2011, 114, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Putte P, Perlas A. The link between gastric volume and aspiration risk. In search of the Holy Grail? Anaesthesia. 2018;73:274- 279.

- Desgranges, F.-P.; Riegel, A.-C.G.; Aubergy, C.; Siqueira, M.D.Q.; Chassard, D.; Bouvet, L. Ultrasound assessment of gastric contents in children undergoing elective ear, nose and throat surgery: a prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia 2017, 72, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz A, Schmidt AR, Buehler PK, et al. Gastric ultrasoundas a preoperative bedside test for residual gastric contents volume in children. Pediatric Anesthesia 2016;26: 1157. [CrossRef]

- Gagey, A.-C.; Siqueira, M.d.Q.; Desgranges, F.-P.; Combet, S.; Naulin, C.; Chassard, D.; Bouvet, L. Ultrasound assessment of the gastric contents for the guidance of the anaesthetic strategy in infants with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: a prospective cohort study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 116, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz A, Thomas S, Melanie F, et al. Ultrasonographic gastricantral area and gastric contents volume in children. Pediatric Anesthesia 2012;22: 144–9. [CrossRef]

- Gagey AC, de Queiroz Siqueira M, Monard C, et al. The effect of pre-operative gastric ultrasound examination on the choice of general anaesthetic induction technique for non-elective paediatric surgery. A prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:304-312.

- Schmitz, A.; Kellenberger, C.J.; Liamlahi, R.; Fruehauf, M.; Klaghofer, R.; Weiss, M. Residual gastric contents volume does not differ following 4 or 6 h fasting after a light breakfast - a magnetic resonance imaging investigation in healthy non-anaesthetised school-age children. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2011, 56, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.; Kellenberger, C.; Lochbuehler, N.; Fruehauf, M.; Klaghofer, R.; Weiss, M. Effect of different quantities of a sugared clear fluid on gastric emptying and residual volume in children: a crossover study using magnetic resonance imaging. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012, 108, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falconer, R.; Skouras, C.; Carter, T.; Greenway, L.; Paisley, A.M. Preoperative fasting: current practice and areas for improvement. Updat. Surg. 2013, 66, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelhardt, T.; Wilson, G.; Horne, L.; Weiss, M.; Schmitz, A. Are you hungry? Are you thirsty? - fasting times in elective outpatient pediatric patients. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2011, 21, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H.; Hellström, P.M.; Frykholm, P. Introducing the 6-4-0 fasting regimen and the incidence of prolonged preoperative fasting in children. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2017, 28, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, R.J.G.; Stuart, G.M.; Willdridge, D.J.; Thomas, M. Using quality improvement methods to reduce clear fluid fasting times in children on a preoperative ward. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2017, 27, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Morrison, C.; Newton, R.; Schindler, E. Consensus statement on clear fluids fasting for elective pediatric general anesthesia. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2018, 28, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.; Johnson, P.A.; Guzzetta, C.E.; Guzzetta, P.C.; Cohen, I.T.; Sill, A.M.; Vezina, G.; Cain, S.; Harris, C.; Murray, J. Pediatric Fasting Times Before Surgical and Radiologic Procedures: Benchmarking Institutional Practices Against National Standards. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2014, 29, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Robeye, A.M.; Barnard, A.N.; Bew, S. Thirsty work: Exploring children's experiences of preoperative fasting. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2019, 30, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.C.; Kinn, S.; Ness, V.; O'Rourke, K.; Randhawa, N.; Stuart, P. Preoperative fasting for preventing perioperative complications in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009, CD005285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennhardt, N.; Beck, C.; Huber, D.; Sander, B.; Boehne, M.; Boethig, D.; Leffler, A.; Sümpelmann, R. Optimized preoperative fasting times decrease ketone body concentration and stabilize mean arterial blood pressure during induction of anesthesia in children younger than 36 months: a prospective observational cohort study. Pediatr. Anesthesia 2016, 26, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpao, A.F.; Wu, L.; Nelson, O.; et al. Preoperative fluid fasting times and postinduction low blood pressure in children: a retrospective analysis. Anesthesiology 2020, 133, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruisselbrink, R.; Arzola, C.; Endersby, R.; Tse, C.; Chan, V.; Perlas, A. Intra- and Interrater Reliability of Ultrasound Assessment of Gastric Volume. Anesthesiology 2014, 121, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).