Submitted:

14 June 2023

Posted:

14 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bedside Examination Tools in AVS

2.1. HINTS/HINTS Plus

2.2. Standing

2.3. TriAGe+ Score and PCI-Score

2.4. ABCD2 Score

2.5. Gait and Truncal Instability (GTI) Rating

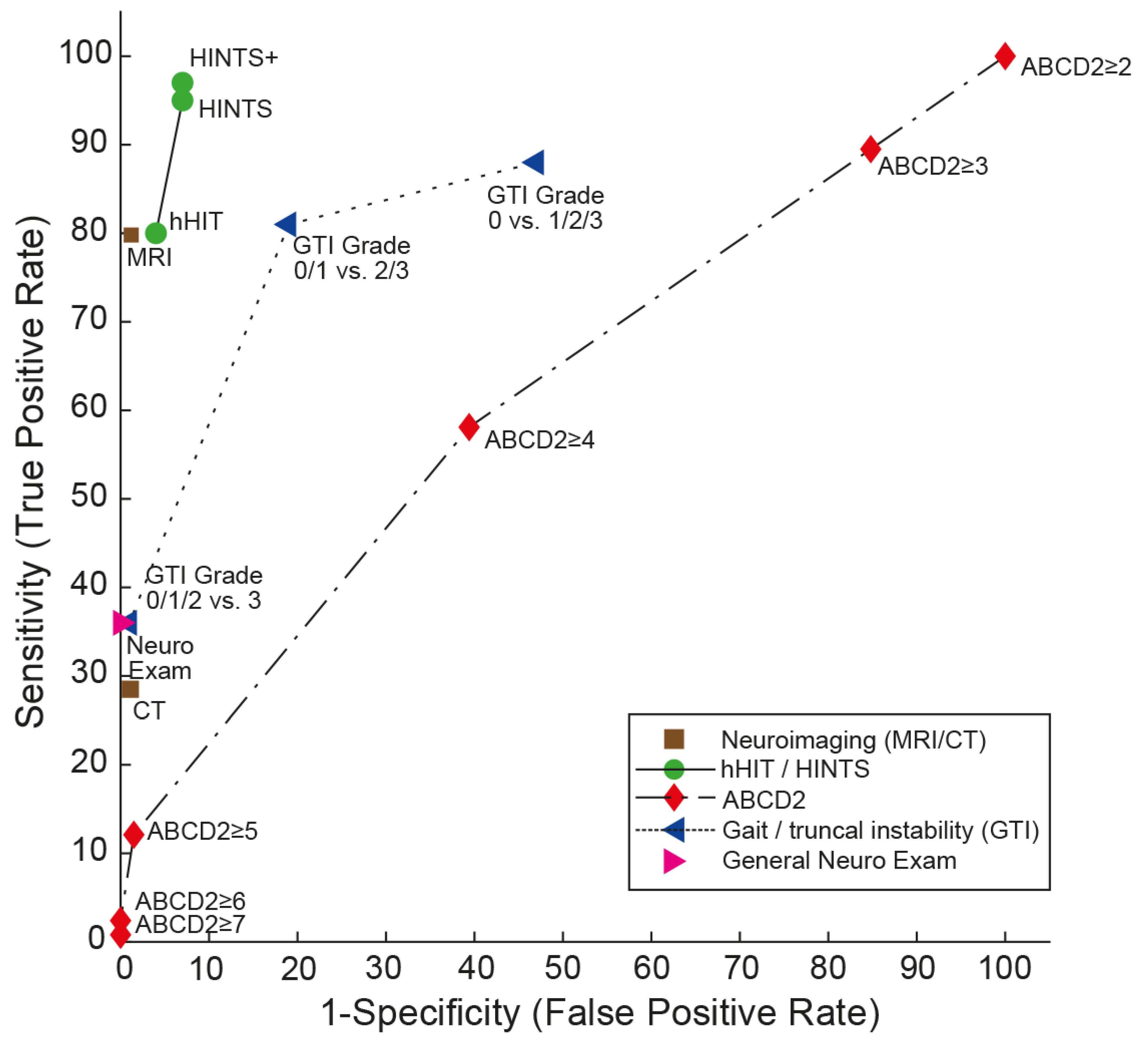

| Score / algorithm | Domains tested | Features | evaluated application | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity / specificity (95% CI)* | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HINTS [18] | Subtle oculomotor signs | Horizontal head-impulse test, horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus, test of skew | AVS with nystagmus | 0.995 (0.985 - 1.000 [19] | 95.3% (92.5 – 98.1%) / 92.6% (88.6 – 96.5%) [14] | Largest number of studies available. Moderate training needed (4-6 hours [23,28]) for successful application. Only patients with at least one vascular risk factor included. |

| HINTS+ [19] | Subtle oculomotor signs | Horizontal head-impulse test, horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus, test of skew, finger rub | AVS with nystagmus | NA | 97.2% (94.0 – 100.0%) / 92.4% (86.9 – 97.9%) [14] | Only patients with at least one vascular risk factor included. |

| STANDING [20,27] | obvious focal neurologic signs and subtle oculomotor signs | Horizontal head-impulse test, horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus, truncal ataxia, provocation maneuvers (Hallpike Dix, Pagnini-McClure) | Acute vertigo or dizziness | NA | 93.4% - 100% / 71.8% - 94.3% [36] | Internal and external validation available. More inclusive than HINTS(+) covering positional vertigo (BPPV) also. Moderate training needed (4-6 hours [23,28]) for successful application. |

| ABCD2 score [31] | Presenting sx, vascular risk factors, obvious focal neurologic signs | age, blood pressure, clinical features (unilateral weakness, speech disturbance), duration of symptoms, diabetes | acute vertigo or dizziness (some studies meeting criteria for AVS) | range: 0.613 to 0.79 (0.61 (0.53 - 0.70) [19]; 0.69 (0.63 - 0.75) [29]; 0.73 (0.68-0.78) [24]; 0.79 (0.73– 0.85) [31]) | for a cut-off value of ≥4: 55.7% (43.3 – 67.5%) / 81.8% (76.4 – 86.2%) [23]; 61.1% (52 – 70%) / 62.3% (51 – 72%) [19] | low diagnostic accuracy in acutely dizzy patients |

| TriAGe+ score [24] | Presenting sx, vascular risk factors, obvious focal neurologic signs, subtle oculomotor signs | triggers, atrial fibrillation, male gender, blood pressure ≥ 140 / 90mm Hg, brainstem or cerebellar dysfunction (incl. skew deviation, truncal ataxia), focal weakness or speech impairment, dizziness, no history of vertigo / dizziness, labyrinth / vestibular disease | acute vertigo or dizziness | 0.82 (0.78-0.86) | for a cut-off value of 10 points: 77.5% (72.8 - 81.8%) / 72.1% (64.1 - 79.2%), | Single center, retrospective study, no prospective validation studies available |

| PCI score [29] | Past history, presenting sx, vascular risk factors, obvious focal neurologic signs | high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, ischemic stroke, rotating and rocking, difficulty in speech, tinnitus, limb and sensory deficit, gait ataxia, and limb ataxia. | acute vertigo or dizziness | 0.82 (0.77 to 0.87) | for a cut-off value of 0 points: 94.1% (NA) / 41.4% (NA) | Single center, retrospective study, no prospective validation studies available |

| GTI rating [21,34,35] | obvious focal neurologic signs | gait and truncal instability (graded rating) | acute vertigo, dizziness or gait imbalance | NA | for a cut-off value of grade 2: 69.7% (43.3 – 87.9% / 83.7% (52.1 – 96.0%) [36] | Lower sensitivity than HINTS(+) or STANDING, but applicable also in patients with isolated truncal instability (without nystagmus) |

3. Discussion

4. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kerber, K.A.; Meurer, W.J.; West, B.T.; Fendrick, A.M. Dizziness presentations in U.S. emergency departments, 1995-2004. Acad Emerg Med 2008, 15, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeldlin, M.; Gaschen, J.; Kammer, C.; Comolli, L.; Bernasconi, C.A.; Spiegel, R.; Bassetti, C.L.; Exadaktylos, A.K.; Lehmann, B.; Mantokoudis, G.; et al. Frequency, aetiology, and impact of vestibular symptoms in the emergency department: a neglected red flag. J Neurol 2019, 266, 3076–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman-Toker, D.E.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Pelletier, A.J.; Butchy, G.T.; Edlow, J.A. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc 2008, 83, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljunggren, M.; Persson, J.; Salzer, J. Dizziness and the Acute Vestibular Syndrome at the Emergency Department: A Population-Based Descriptive Study. Eur Neurol 2018, 79, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman-Toker, D.E.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Pelletier, A.J.; Edlow, J.A. Disconnect between charted vestibular diagnoses and emergency department management decisions: a cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Acad Emerg Med 2009, 16, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman-Toker, D.E.; McDonald, K.M.; Meltzer, D.O. How much diagnostic safety can we afford, and how should we decide? A health economics perspective. BMJ Qual Saf 2013, 22 Suppl 2, ii11–ii20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber Tehrani, A.S.; Coughlan, D.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Mantokoudis, G.; Korley, F.K.; Kerber, K.A.; Frick, K.D.; Newman-Toker, D.E. Rising annual costs of dizziness presentations to U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med 2013, 20, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnutzer, A.A.; Lee, S.H.; Robinson, K.A.; Wang, Z.; Edlow, J.A.; Newman-Toker, D.E. ED misdiagnosis of cerebrovascular events in the era of modern neuroimaging: A meta-analysis. Neurology 2017, 88, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerber, K.A.; Brown, D.L.; Lisabeth, L.D.; Smith, M.A.; Morgenstern, L.B. Stroke among patients with dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance in the emergency department: a population-based study. Stroke 2006, 37, 2484–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICD-11 (Mortality and Morbidity Statistics). Available online: https://icd.who.int/dev11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f1462112221 (accessed on October 18th 2018).

- Tarnutzer, A.A.; Berkowitz, A.L.; Robinson, K.A.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Newman-Toker, D.E. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ 2011, 183, E571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, K.A.; Schweigler, L.; West, B.T.; Fendrick, A.M.; Morgenstern, L.B. Value of computed tomography scans in ED dizziness visits: analysis from a nationally representative sample. Am J Emerg Med 2010, 28, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, S.F.; Syamal, M.N.; Yaremchuk, K.; Peterson, E.; Seidman, M. The costs and utility of imaging in evaluating dizzy patients in the emergency room. Laryngoscope 2013, 123, 2250–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarnutzer, A.A.; Gold, D.; Wang, Z.; Robinson, K.A.; Kattah, J.C.; Mantokoudis, G.; Saber Tehrani, A.S.; Zee, D.S.; Edlow, J.A.; Newman-Toker, D.E. Impact of Clinician Training Background and Stroke Location on Bedside Diagnostic Accuracy in the Acute Vestibular Syndrome - A Meta-Analysis. Ann Neurol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber Tehrani, A.S.; Kattah, J.C.; Mantokoudis, G.; Pula, J.H.; Nair, D.; Blitz, A.; Ying, S.; Hanley, D.F.; Zee, D.S.; Newman-Toker, D.E. Small strokes causing severe vertigo: frequency of false-negative MRIs and nonlacunar mechanisms. Neurology 2014, 83, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber Tehrani, A.S.; Kattah, J.C.; Kerber, K.A.; Gold, D.R.; Zee, D.S.; Urrutia, V.C.; Newman-Toker, D.E. Diagnosing Stroke in Acute Dizziness and Vertigo: Pitfalls and Pearls. Stroke 2018, 49, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Toker, D.E.; Edlow, J.A. TiTrATE: A Novel, Evidence-Based Approach to Diagnosing Acute Dizziness and Vertigo. Neurol Clin 2015, 33, 577–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattah, J.C.; Talkad, A.V.; Wang, D.Z.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Newman-Toker, D.E. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke 2009, 40, 3504–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman-Toker, D.E.; Kerber, K.A.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Pula, J.H.; Omron, R.; Saber Tehrani, A.S.; Mantokoudis, G.; Hanley, D.F.; Zee, D.S.; Kattah, J.C. HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med 2013, 20, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanni, S.; Nazerian, P.; Casati, C.; Moroni, F.; Risso, M.; Ottaviani, M.; Pecci, R.; Pepe, G.; Vannucchi, P.; Grifoni, S. Can emergency physicians accurately and reliably assess acute vertigo in the emergency department? Emerg Med Australas 2015, 27, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, S.; Martinez, C.; Zalazar, G.; Moro, M.; Batuecas-Caletrio, A.; Luis, L.; Gordon, C. The Diagnostic Accuracy of Truncal Ataxia and HINTS as Cardinal Signs for Acute Vestibular Syndrome. Front Neurol 2016, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Tan, G.; Zhan, Q.; Zhou, J. Central nystagmus plus ABCD(2) identifying stroke in acute dizziness presentations. Acad Emerg Med 2021, 28, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlier, C.; Hoarau, M.; Fels, A.; Vitaux, H.; Mousset, C.; Farhat, W.; Firmin, M.; Pouyet, V.; Paoli, A.; Chatellier, G.; et al. Differentiating central from peripheral causes of acute vertigo in an emergency setting with the HINTS, STANDING, and ABCD2 tests: A diagnostic cohort study. Acad Emerg Med 2021, 28, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, R.; Nakada, T.; Ojima, T.; Serizawa, M.; Imai, N.; Yagi, N.; Tasaki, A.; Aoki, M.; Oiwa, T.; Ogane, T.; et al. The TriAGe+ Score for Vertigo or Dizziness: A Diagnostic Model for Stroke in the Emergency Department. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2017, 26, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmagyi, G.M.; Curthoys, I.S. A clinical sign of canal paresis. Arch Neurol 1988, 45, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edlow, J.A.; Carpenter, C.; Akhter, M.; Khoujah, D.; Marcolini, E.; Meurer, W.J.; Morrill, D.; Naples, J.G.; Ohle, R.; Omron, R.; et al. Guidelines for reasonable and appropriate care in the emergency department 3 (GRACE-3): Acute dizziness and vertigo in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2023, 30, 442–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanni, S.; Pecci, R.; Edlow, J.A.; Nazerian, P.; Santimone, R.; Pepe, G.; Moretti, M.; Pavellini, A.; Caviglioli, C.; Casula, C.; et al. Differential Diagnosis of Vertigo in the Emergency Department: A Prospective Validation Study of the STANDING Algorithm. Front Neurol 2017, 8, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlier, C.; Fels, A.; Vitaux, H.; Mousset, C.; Perugini, A.; Chatellier, G.; Ganansia, O. Effectiveness and reliability of the four-step STANDING algorithm performed by interns and senior emergency physicians for predicting central causes of vertigo. Acad Emerg Med 2023, 30, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Su, R.; Deng, M.; Liu, J.; Hu, Q.; Song, Z. A Posterior Circulation Ischemia Risk Score System to Assist the Diagnosis of Dizziness. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2018, 27, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, S.C.; Rothwell, P.M.; Nguyen-Huynh, M.N.; Giles, M.F.; Elkins, J.S.; Bernstein, A.L.; Sidney, S. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2007, 369, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navi, B.B.; Kamel, H.; Shah, M.P.; Grossman, A.W.; Wong, C.; Poisson, S.N.; Whetstone, W.D.; Josephson, S.A.; Johnston, S.C.; Kim, A.S. Application of the ABCD2 score to identify cerebrovascular causes of dizziness in the emergency department. Stroke 2012, 43, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohle, R.; Montpellier, R.A.; Marchadier, V.; Wharton, A.; McIsaac, S.; Anderson, M.; Savage, D. Can Emergency Physicians Accurately Rule Out a Central Cause of Vertigo Using the HINTS Examination? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2020, 27, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriew, C.; Regis, A.; Bodunde, O.; Lepage, R.; Turgeon, Z.; McIsaac, S.; Ohle, R. Diagnostic Accuracy of the HINTS Exam in an Emergency Department: A Retrospective Chart Review. Acad Emerg Med 2021, 28, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Sohn, S.I.; Cho, Y.W.; Lee, S.R.; Ahn, B.H.; Park, B.R.; Baloh, R.W. Cerebellar infarction presenting isolated vertigo: frequency and vascular topographical patterns. Neurology 2006, 67, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, I.S.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, K.D.; Kim, M.J.; Oh, S.Y.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.S.; Park, S.H. Isolated nodular infarction. Stroke 2009, 40, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.P.; Oliveira, J.E.S.L.; Farah, W.; Seisa, M.O.; Balla, A.K.; Christensen, A.; Farah, M.; Hasan, B.; Bellolio, F.; Murad, M.H. Diagnostic accuracy of the physical examination in emergency department patients with acute vertigo or dizziness: A systematic review and meta-analysis for GRACE-3. Acad Emerg Med 2023, 30, 552–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perloff, M.D.; Patel, N.S.; Kase, C.S.; Oza, A.U.; Voetsch, B.; Romero, J.R. Cerebellar stroke presenting with isolated dizziness: Brain MRI in 136 patients. Am J Emerg Med 2017, 35, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, S.; Martinez, C.; Zalazar, G.; Koohi, N.; Kaski, D. Acute truncal ataxia without nystagmus in patients with acute vertigo. Eur J Neurol 2023, 30, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, S.; Inatomi, Y.; Yonehara, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hirano, T.; Ando, Y.; Uchino, M. Discrimination of acute ischemic stroke from nonischemic vertigo in patients presenting with only imbalance. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014, 23, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.P.; Oliveira, J.E.S.L.; Farah, W.; Seisa, M.; Kara Balla, A.; Christensen, A.; Farah, M.; Hasan, B.; Bellolio, F.; Murad, M.H. Diagnostic accuracy of neuroimaging in emergency department patients with acute vertigo or dizziness: A systematic review and meta-analysis for the Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korda, A.; Wimmer, W.; Zamaro, E.; Wagner, F.; Sauter, T.C.; Caversaccio, M.D.; Mantokoudis, G. Videooculography "HINTS" in Acute Vestibular Syndrome: A Prospective Study. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 920357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nham, B.; Reid, N.; Bein, K.; Bradshaw, A.P.; McGarvie, L.A.; Argaet, E.C.; Young, A.S.; Watson, S.R.; Halmagyi, G.M.; Black, D.A.; et al. Capturing vertigo in the emergency room: three tools to double the rate of diagnosis. J Neurol 2022, 269, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman-Toker, D.E.; Curthoys, I.S.; Halmagyi, G.M. Diagnosing Stroke in Acute Vertigo: The HINTS Family of Eye Movement Tests and the Future of the "Eye ECG". Semin Neurol 2015, 35, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).