1. Introduction

Automated assessment of skills involves quantifying how proficient a person is in the task at hand. Automated skill assessment can be used in many areas, such as physical movement assessment and music education. With the higher cost of manual instruction and space limitations, face-to-face piano instruction between teacher and student has become difficult, which makes automated skill assessment very important.

As we all know that piano performances are made up of visual and auditory aspects, therefore the assessment of piano players can also be done from both visual and auditory aspects. For the visual aspect, a piano performance judge can score the performance by observing the fingering of the player. Similarly, for the aural aspect, the judge scores the performance by judging the rhythm of the music played by the performer.

At present, most studies on piano performance evaluation have been conducted based on a single audio mode [

1,

2,

3], ignoring the information contained in the video mode, such as playing technique and playing posture, resulting in a one-sided assessment of the player’s skill level and an inability to make a comprehensive assessment from multiple aspects.

However, most of the existing studies on multimodal piano skill assessment are based on shallow networks, which are deficient in extracting complex spatio-temporal features and time-frequency features. There is also a large gap between the number of extracted video features and extracted audio features when the feature fusion, leading to models that do not fully utilize feature information from both modalities.

Aiming at addressing the issues, we consider ResNet as the backbone network of the model, which can expand the network to deeper layers through the structure of residual connections to better extract complex features. ResNet-3D [

4] and ResNet-2D [

5] are used to extract video features and audio features, respectively. To fully utilize the video features and the audio features, we exploit ResNet18-3D and ResNet18-2D to deal with the issue of feature extraction, keeping the number of video and audio features uniform.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows.

(1) We present a novel ResNet-based audio-visual fusion model to evaluate piano players’ proficiency by utilizing both video and audio information, which effectively solves the problem that the unimodal approaches fail to utilize video information and the multimodal approaches fail to fully utilize video and audio information. Firstly, we extract video features and audio features by ResNet-3D and ResNet-2D, respectively. Further, the extracted features are fused to form multimodal features that will be used for piano skills evaluation.

(2) We present an effective method that can make full use of video features as well as audio features by keeping the number of video features close to the number of audio features. When the number of features of one modality is much larger than that of the other, it causes the model to tend to place more emphasis on the modality with more features and ignore the modality with fewer features. This can make the performance of the model limited and unable to make full use of the information of all the modes to make more accurate predictions.

(3) We evaluated the proposed audio-visual fusion model on the PISA dataset and compared it with the state-of-the-art methods. The results suggest that our model is superior in evaluating piano players’ skills as well as in computational efficiency.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Skills Assessment

Recently, there have also been significant advances in research in the area of skills assessment. Seode et al. [

6] proposed an autoencoder whose intermediate layer is an LSTM layer to detect runners’ skills such as characteristics and habits, which aimed to improve the runners’ performance. Lid et al. [

7] constructed a novel RNN-based spatial attention model that evaluates human operational skills while performing a task from video, considering accumulated attention state from previous frames as well as high-level information about the progress of an undergoing task. Doughty et al. [

8] proposed a model called Rank-Aware Attention to determine relative skills from long videos by means of a learnable temporal attention module. And presented a method to assess the relative overall level of skills in long videos by focusing on skill-related components. Lee et al. [

9] proposed a novel dual-stream convolutional neural network, combining video and audio, to determine which notes on the piano are being played at any given time and to identify the fingers used to press those notes. Doughty et al. [

10] proposed a pairwise deep ranking model which utilizes both spatial and temporal streams in combination with a novel loss to determine and rank skill.

2.2. Piano Performance in Unimodality

The most widely used method for piano skill evaluation is based on aural mode. Chang et al. [

1] proposed an LSTM-based piano performance evaluation strategy to evaluate piano performance, carried out from the three indicators of overall evaluation, rhythm, and expressiveness. Wang et al. [

11] proposed two different audio-based systems for piano performance evaluation. The first one is a sequential and modularized system that extracts acoustic features by convolutional neural networks, matches them by dynamic time warping, and performs score regression. The second system is an end-to-end system with CNNs and the attention mechanism. It takes two acoustic feature sequences as input and directly predicts a performance score. Varinya et al. [

12] evaluated piano playing by using four different approaches: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Naive Bayes (NB), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM). The evaluated results were classified as "good", "normal" and "bad", and they found that the CNN approach outperformed the other methods. Liao et al. [

13] presented a musical instrument digital interface(MIDI) piano evaluation scheme based on RNN structure and Spark computational engine to compensate for the shortcomings of rule-based evaluation methods, which can not consider the coherence and expressiveness of music.

2.3. Piano Performance in Multimodality

Every source or form of information can be called a modality. For example, humans have the senses of touch, sight, hearing, and smell; the communication media of information are speech, video, text, etc. Multimodal machine learning aims to achieve the ability to process and understand multisource modal information through machine learning methods. Multimodal machine learning has been used in a wide variety of fields. [

14] shows that combining audio and video data can improve the transcription obtained from each modality alone. Parmar et al. [

15] were the first to propose combining video and audio to assess piano skills, using C3D and ResNet18-2D to process video and audio information separately, and achieved good performance on their proposed PISA dataset.

2.4. Transfer Learning

Transfer learning is a method of extending a model trained on a specific task with a large amount of data to another similar task, using the prior knowledge it has learned to extract useful features for the new task. In recent years, transfer learning has demonstrated exceptional performance in a variety of research tasks. Pre-trained models trained on large corpus such as ImageNet have been widely used in various fields, such as graph segmentation [

16,

17], medical image analysis [

18,

19]. In [

20], C3D [

21] trained from scratch on UCF101, achieved 88%. However, using a pre-trained model trained on Kinetics, 98% performance was achieved.

In general, most existing studies on piano skill assessment are based on audio modality, ignoring the video information, while few studies based on multimodality, such as [

15], suffer from the inability to capture complex spatio-temporal features that embody fingering information and pitch information, and fail to make full use of video features and audio features. Therefore, we propose a ResNet-based audio-visual fusion model, which is able to capture complex spatio-temporal features and take full use of extracted features.

3. Methodology

In this section, we detail the audio-visual fusion model for assessing the skill level of piano performers.

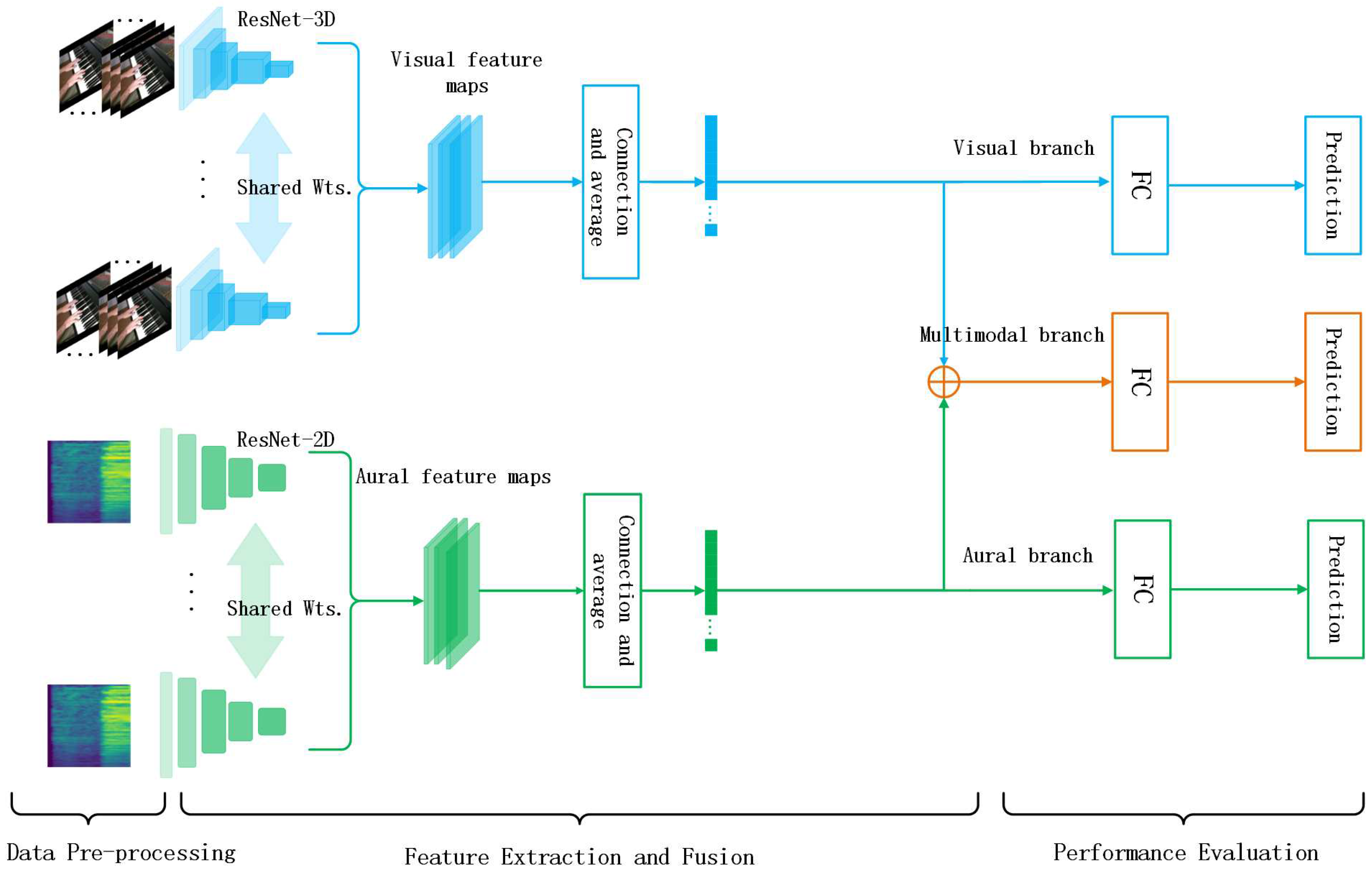

Figure 1 shows the framework of our proposal. It consists of three main parts: data pre-processing, feature extraction and fusion, and performance evaluation. First, the video data is framed and cropped to serve as the input for the visual branch. The raw audio is converted to the corresponding Mel-spectrogram by signal processing techniques and spectral analysis methods. Secondly, we feed the processed video and audio data into the audio-visual fusion model to extract the respective features, and fuse the extracted features to form multimodal representations. Finally, we pass the multimodal features as input to the fully connected layer and then perform prediction.

Figure 1.

Framework of audio-visual fusion model for piano skill evaluation.

Figure 1.

Framework of audio-visual fusion model for piano skill evaluation.

3.1. Data Pre-Processing

For the visual input, the background, face, and other information contained in the video is useless. So we crop the video data before feeding it into the model. In the end, the visual information includes the forearm, hand, and piano of the player, as shown in

Figure 2.

For the auditory input, we convert the raw audio into the corresponding Mel-spectrogram, which helps us to better extract the information such as the pitch that is embedded in the audio data. Firstly, we convert the raw audio into the corresponding spectrogram by STFT(Short Time Fourier Transform):

where

represents the outcome of the STFT,

means the window function,

refers to the time-domain waveform of the original signal,

f represents the frequency,

t indicates the time, and

j is the imaginary unit, which satisfies

. Then, the obtained spectrogram is mapped to the corresponding Mel-spectrogram by Mel-scale [

22]:

where

m represents the Mel frequency and

f means the original frequency. Finally, the Mel-spectrogram information is expressed in decibels.

Figure 2.

Examples of samples from the dataset. Images after cropping (only a part of the complete sample is shown).

Figure 2.

Examples of samples from the dataset. Images after cropping (only a part of the complete sample is shown).

3.2. Feature Extraction and Fusion

Visual branch: There are some skills of the performers that can only be observed and judged by sight rather than by hearing. Such as the fingering skills of the performer. For example, a professional pianist playing a piece at high speed might use his index and ring fingers to play 8 intervals, which is difficult for an average pianist. For a pianist, the lack of such skills would not give any indication as to the level of one. However, if a pianist possesses these skills, it can prove that he has achieved a high level of technical achievement.

The movements of fingers from videos involve both appearance and temporal dynamics of the video sequences. Efficient modeling of the spatio-temporal dynamics of the video sequences plays a crucial role in extracting robust features, which in-turn improves the performance of the model. 3D-CNNs are found to be efficient in capturing the spatio-temporal dynamics in videos. Specifically, we consider ResNet-3D [

4] to extract spatiotemporal features of the performance clips from a video sequence. Compared with conventional 3D-CNNs, ResNet-3D can effectively capture the spatio-temporal dynamics of video modality with higher computational efficiency. In addition, it can utilize the trained pre-trained model to improve the model performance as shown in Algorithm 1. Finally, we consider the averaging method as our aggregation scheme (see

Section 3.2).

|

Algorithm 1 Model Initialization Algorithm |

Input: :the dictionary of model parameters; :the dictionary of pre-trained model parameters;

Output: :the model dictionary after completing the update;

- 1:

functionMODELINIT(, ) - 2:

for each do

- 3:

if then

- 4:

- 5:

end if

- 6:

end for

- 7:

return

- 8:

end function

|

Aural branch: We can also get a lot of information about the piano from the audio. The rhythm, notes, and pitches of the piano can be perceived through listening, and this is a common, simple, and practical way to evaluate a piano piece. In fact, different scores differ greatly in terms of style, rhythm, etc. This requires the judges to have great proficiency in the piece that the performer is playing in a piano competition or performance, making some judges who are not familiar with the piece somewhat deficient in judging the skills of the performers.

Information such as the pitch and rhythm of a piano performance is contained in the audio data, and both raw audio waveform [

23,

24] and spectrograms [

25,

26] can be used to extract auditory features. However, the spectrogram can provide more detailed and accurate audio features. Specifically, we consider converting the raw audio data into the corresponding Mel-spectrogram, which can be regarded as image data for it is in the form of a two-dimensional matrix. Further, compared to the traditional 2D-CNN, ResNet-2D [

5] outperforms in terms of computational efficiency and feature extraction. Also, it can utilize the pre-trained model to improve performance. Therefore, we prefer ResNet-2D to extract auditory features. Finally, we consider the averaging method as our aggregation scheme (see

Section 3.2).

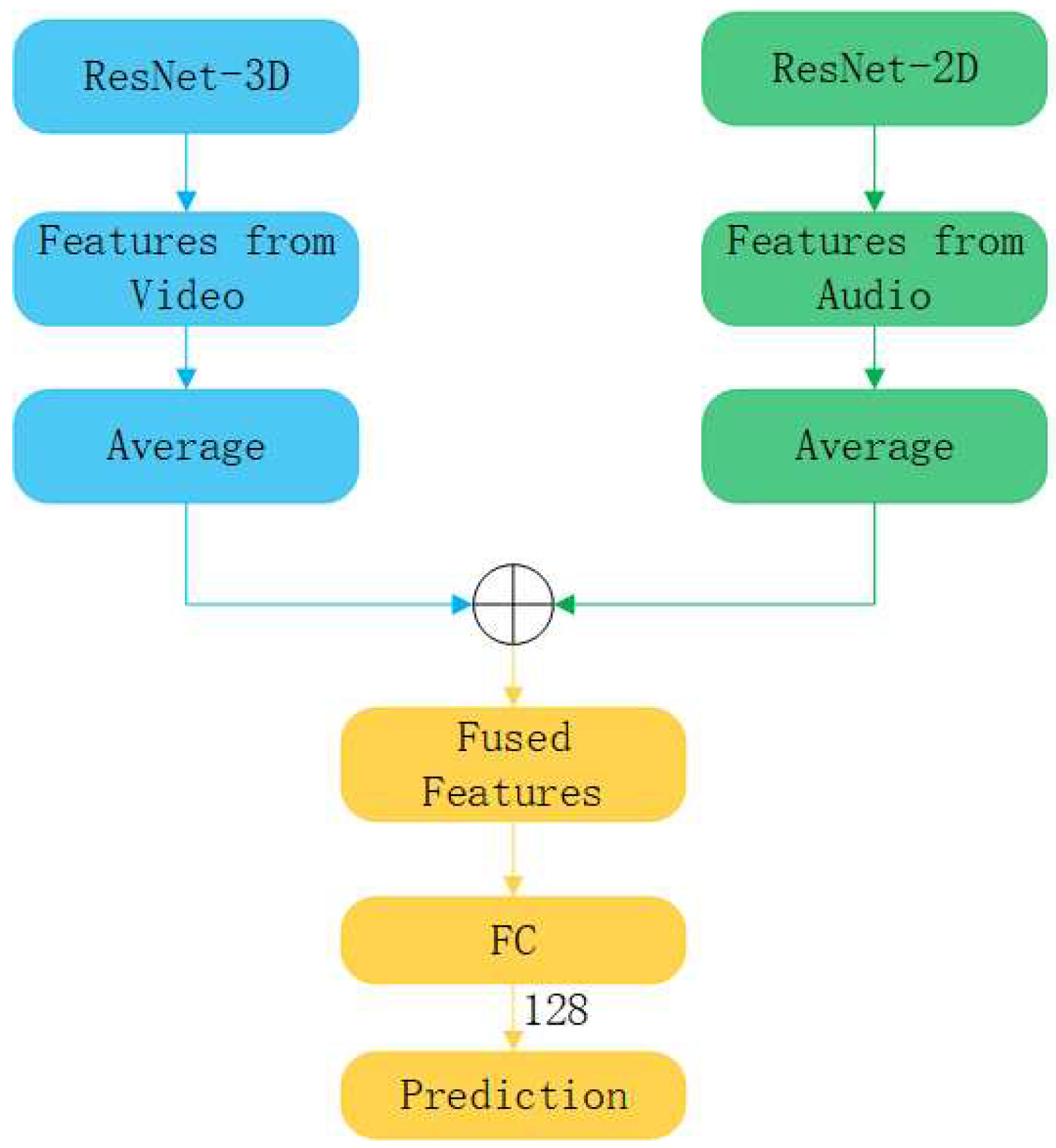

Multimodal branch: Let

and

represent two sets of deep feature vectors extracted for the visual and aural modalities, where

, and

. The

d represents the dimension of the visual and aural feature representations, and

M and

N denote the number of extracted visual and aural features respectively. The multimodal features,

, are obtained by splicing

with

through the Algorithm 2:

where

L =

M +

N denotes the number of the fused features, as shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The structure of feature fusion.

Figure 3.

The structure of feature fusion.

|

Algorithm 2 Feature Fusion Algorithm |

Input: : the video features extracted by ResNet-3D; : the audio features extracted by ResNet-2D;

Output: : multimodal features;

- 1:

function FeatureFusion (, ) - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

if then

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

- 9:

- 10:

end if

- 11:

return

- 12:

end function

|

Aggregation option: During the piano performance, the score obtained by the players can be perceived as an additive operation. It is often advantageous to perform linear operations on the learned features, which enhances the interpretability and expressiveness of the learned features. Linear operations can also be utilized to reduce the dimensionality of the features, which enhances the efficiency and generalization capabilities of the model. Consequently, we propose the utilization of linear averaging as the preferred aggregation scheme. The application of linear averaging is detailed in Algorithm 3 and

Figure 4 below.

|

Algorithm 3 Feature Average Algorithm |

Input: : The list of features obtained from the network;

Output: : Features after averaging process;

- 1:

Initialize to Tensor format; - 2:

for each in do

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

end for - 8:

- 9:

return

|

Figure 4.

Feature average option.

Figure 4.

Feature average option.

3.3. Performance Evaluation

In the visual and aural branches, to reduce the dimensionality of the features to 128, we pass them through a linear layer, as shown in

Figure 3, and finally input them into the prediction layer. In the multimodal branch, our operations are similar to others, except that we do not back-propagate from the multimodal branch to a separate modal backbone to avoid cross-modal contamination.

4. Experiments

In the paper, we conduct the experiment on the real dataset and evaluate the performance of our proposal. In

Section 4.1, we introduce the details of the PISA dataset. In

Section 4.2, we show the evaluation metric that we used. Implementation Details are presented in

Section 4.3. And in

Section 4.4 and 4.5, we discuss the experimental results and the ablation study, respectively.

4.1. Multimodal PISA Dataset

PISA: Piano Skills Assessment (PISA) dataset. It consisted of 61 videos of piano performances collected from YouTube and rated the performers’ skill level on a scale of 1-10, as shown in

Figure 5(a). Non-overlapping samples were obtained by uniform sampling as shown in

Figure 5(b). And there is no overlap between the training set and the test set. The details are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the dataset.

Table 1.

Overview of the dataset.

| |

Total samples |

Training samples |

Test samples |

| PISA Dataset |

992 |

516 |

476 |

Figure 5.

(a)Histograms of player-levels. (b)Sampling scheme:Time along the x-axis. Each sample consists of squares with the same color, and each square represents a clip of 16 frames.

Figure 5.

(a)Histograms of player-levels. (b)Sampling scheme:Time along the x-axis. Each sample consists of squares with the same color, and each square represents a clip of 16 frames.

4.2. Evaluation Metric

Aiming to evaluate the performance of the proposed model, we use accuracy (in %) as the performance metric.

where

represents the number of samples that are labeled as positive samples and also classified as positive samples;

refers to the number of samples labeled as negative samples but classified as positive samples.

4.3. Implementation Details

The entire model is built by pytorch [

27]. For regularizing the network, dropout is used with p = 0.5 on the linear layers. The initial learning rate of the network is set to be 1e - 4 and the ADAM [

28] is used as the optimizer for all experiments. Also, weight decay of 1e - 1 is used. Due to hardware limitations and memory constraints, the batch size of the model is set to 4. The number of epochs is set to 100, while the training time of each epoch is recorded.

Visual branch: The finger images are resized to 112 × 112 and a horizontal flip is applied to them in the training, which are finally fed into the ResNet-3D model. In order to generate more samples, the videos of the dataset are converted to sequences of 160 frames with a subsequence length of 16, resulting in 516 training samples and 476 validation samples. The structure of ResNet-3D is shown in

Table 2, which is pre-trained on the KM dataset [

4] (merged Kinetics-700 [

29] and MiT [

30]). Finally, to explore the effect of different layers for ResNet-3D on the multimodal fusion model, we consider networks with 18, 34, and 50 layers for our experiments.

Table 2.

ResNet-3D for visual branch. All conv. layers are followed by Batch Normalization (BN) and Rectified Linear Units (ReLu). "[ ] x m" means repeat this block m times.

Table 2.

ResNet-3D for visual branch. All conv. layers are followed by Batch Normalization (BN) and Rectified Linear Units (ReLu). "[ ] x m" means repeat this block m times.

| Stage |

18-layer |

34-layer |

50-layer |

| Block1 |

Conv: 64, 7×7×7, 2×2×2

Max pool: 3×3×3, 2×2×2 |

| Block2_x |

|

|

|

| Block3_x |

|

|

|

| Block4_x |

|

|

|

| Block5_x |

|

|

|

| Block6 |

Adaptive average pool:1×1×1 |

| Block7 |

Linear:in = 512, out = 128 |

Linear:in = 2048, out = 128 |

| Block8 |

Linear:in = 128, out = 10 |

Aural branch: The audio signal is extracted from the corresponding video sequence and re-sampled to 44.1KHz, which is further segmented into short audio segments. Firstly, we split the extracted audio signal into sub-audio segments, the shortest of which is 5.33 seconds and the longest is 6.67 seconds, corresponding to a sequence of 160 frames in the visual branch. The spectrogram is first obtained by short-time Fourier transform (STFT) of each sub-audio segment, and then the spectrogram is filtered to obtain the Mel-spectrogram, where the window length is considered to be 2048, the step size is 512, and the number of Mel-bands generated is 128. Then the obtained Mel-spectrogram is converted to decibels, expressed in dB, and resized to 224 x 224. These Mel-spectrograms are then fed into ResNet-2D described in

Table 3, where the initial weights of the network are initialized with values from the ImageNet [

31] pre-trained model. To match the pre-trained model with our model, we change the input channels of the first convolutional layer of the pre-trained network from 3 to 1. As with the visual branch, to explore the effect of different layers for ResNet-2D on the multimodal fusion model, we consider networks with 18, 34, and 50 layers for our experiments.

Table 3.

ResNet-2D for aural branch. All conv. layers are followed by Batch Normalization (BN) and Rectified Linear Units (ReLu). "[ ] x m" means repeat this block m times.

Table 3.

ResNet-2D for aural branch. All conv. layers are followed by Batch Normalization (BN) and Rectified Linear Units (ReLu). "[ ] x m" means repeat this block m times.

| Stage |

18-layer |

34-layer |

50-layer |

| Block1 |

Conv:64, 7×7, 2×2

Max pool:3×3, 2×2 |

| Block2_x |

|

|

|

| Block3_x |

|

|

|

| Block4_x |

|

|

|

| Block5_x |

|

|

|

| Block6 |

Average pool:7×7, 1×1 |

| Block7 |

Linear:in = 512, out = 128 |

Linear:in = 2048, out = 128 |

| Block8 |

Linear:in = 128, out = 10 |

4.4. Results of Experiments

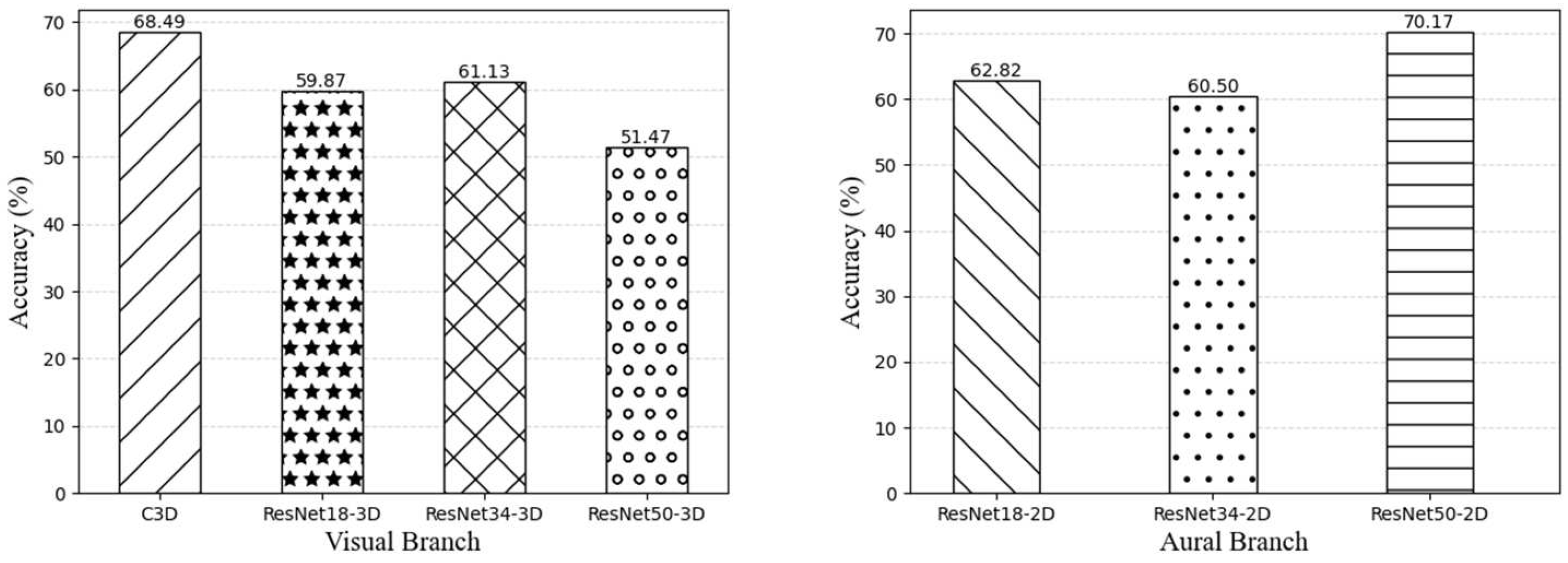

Table 4 and

Figure 6 show the results of unimodal models and the audio-visual fusion models on the PISA dataset. Basically, both the unimodal model and the audio-visual fusion model can achieve good results. Moreover, the audio-visual fusion model can obtain better results than the unimodal model, which indicates that the multimodal method can well compensate for the inability of the audio model alone to utilize visual information and provide more accurate and comprehensive evaluation results. And our audio-visual fusion model obtained the best experimental results, achieving an accuracy rate of 70.80%.

Table 4.

Performance (% accuracy) of multimodal evaluation. V : A: the ratio of the number of video features to the number of audio features.

Table 4.

Performance (% accuracy) of multimodal evaluation. V : A: the ratio of the number of video features to the number of audio features.

| Model |

V : A |

Accuracy (%) |

| C3D + ResNet18-2D [15] |

8:1 |

68.70 |

| ResNet18-3D + ResNet34-2D |

1:1 |

66.39 |

| ResNet34-3D + ResNet18-2D |

1:1 |

66.81 |

| ResNet34-3D + ResNet34-2D |

1:1 |

65.97 |

| ResNet50-3D + ResNet50-2D |

1:1 |

59.45 |

| ResNet18-3D + ResNet18-2D (Ours) |

1:1 |

70.80 |

Figure 6.

Performance (% accuracy) of unimodal evaluation.

Figure 6.

Performance (% accuracy) of unimodal evaluation.

As shown in

Table 5, our audio-visual fusion model outperforms in computational efficiency compared to the other models. This is due to the residual structure that accelerates the convergence speed of the network and the small convolutional kernel that reduces the complexity of the convolutional operation, thus achieving the result of accelerating the computational efficiency of the model.

Table 5.

Average time to train 100 epochs per model.

Table 5.

Average time to train 100 epochs per model.

| Model |

Calculation time (s) |

| C3D + ResNet18-2D |

111.08 |

| ResNet18-3D + ResNet34-2D |

87.91 |

| ResNet18-3D + ResNet50-2D |

96.75 |

| ResNet34-3D + ResNet18-2D |

97.95 |

| ResNet34-3D + ResNet34-2D |

110.33 |

| ResNet34-3D + ResNet50-3D |

118.79 |

| ResNet50-3D + ResNet18-2D |

96.71 |

| ResNet50-3D + ResNet34-2D |

109.79 |

| ResNet50-3D + ResNet50-2D |

119.93 |

| ResNet18-3D + ResNet18-2D (Ours) |

74.02 |

The results in

Table 6 show that the accuracy improvement of the audio-visual fusion model is smaller when the ratio of the number of video features to the number of audio features is relatively large. However, when the number of features of both is close to each other, the accuracy improvement is relatively larger. The reason may be that the number of features of one modality is much larger than that of the other, which causes the model to tend to place more emphasis on the modality with more features and ignore the modality with fewer features.

Table 6.

Performance (% accuracy). V : A: the ratio of the number of video features to the number of audio features.

Table 6.

Performance (% accuracy). V : A: the ratio of the number of video features to the number of audio features.

| Model |

V : A |

Accuracy (%) |

| C3D + ResNet18-2D |

8:1 |

68.70 |

| ResNet18-3D + ResNet50-2D |

1:4 |

65.55 |

| ResNet34-3D + ResNet50-2D |

1:4 |

67.02 |

| ResNet50-3D + ResNet18-2D |

4:1 |

64.50 |

| ResNet50-3D + ResNet34-2D |

4:1 |

61.34 |

| RsetNet18-3D + ResNet18-2D (Ours) |

1:1 |

70.80 |

4.5. Ablation Study

Impact of Pretraining. We compare the experimental results of the randomly initialized audio-visual fusion model with the audio-visual fusion model initialized by the KM and ImageNet pre-trained models. As shown in

Table 7, the audio-visual fusion model using the pre-trained model significantly outperforms the randomly initialized audio-visual fusion model on the PISA dataset and the time consumed by the two methods is similar. Transferring the pre-trained model trained on a large dataset to our model can effectively improve the accuracy of the model.

Table 7.

Performance impact due to pretraining. KM: the merged Kinetics-700 and Moments in Time (MiT).

Table 7.

Performance impact due to pretraining. KM: the merged Kinetics-700 and Moments in Time (MiT).

| |

Accuracy (%) |

Calculation time (s) |

| Without Pretrain |

57.98 |

73.99 |

| KM + ImageNet Pretrain(Used) |

70.80 |

74.02 |

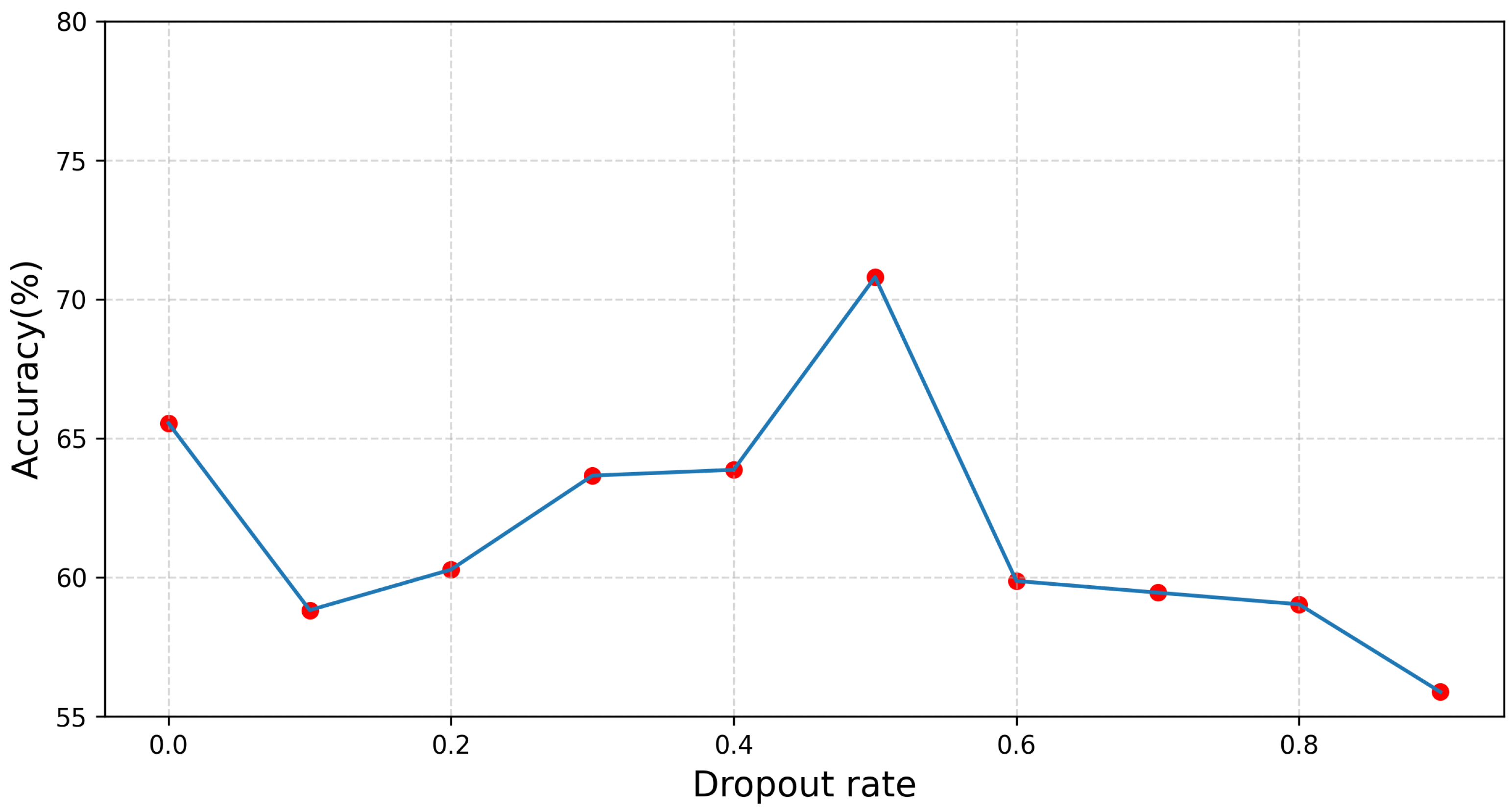

Impact of Dropout Rate. After extracting the multimodal features, we used Dropout on them and also investigated the effect of different drop rates on the performance of the audio-visual fusion model. The results are shown in

Figure 7. When we trained the audio-visual fusion model without Dropout, the accuracy is only 65.55%. As the dropout rate increases, the model accuracy gradually increases and reaches its highest at 0.5, and then gradually decreases.

Figure 7.

Performance impact due to dropout rate.

Figure 7.

Performance impact due to dropout rate.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we propose a ResNet-based audio-visual fusion model for piano skill evaluation, which compensates for the inability of the audio model alone to use visual information. Also, the proposed model can effectively utilize feature information from both video and audio modalities to evaluate players’ skill levels in a more accurate and multifaceted manner. We investigate the effect of combining different layers with ResNet on the performance and find that the best performance is achieved by combining 18 layers. With a similar number of video and audio features, the model can take advantage of both to achieve better performance. Compared with the previous models, our model is better in computational efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and Y.W.; methodology, Y.W.; validation, X.Z., Y.W.; resources, Y.W.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and X.C.; supervision, X.Z. and X.C.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education (17YJCZH260), the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020YFS0057)

References

- Chang, X.; Peng, L. Evaluation strategy of the piano performance by the deep learning long short-term memory network. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. An Empirical Analysis of Piano Performance Skill Evaluation Based on Big Data. Mobile Information Systems 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Pan, J.; Yi, H.; Song, Z.; Li, M. Audio-based piano performance evaluation for beginners with convolutional neural network and attention mechanism. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 2021, 29, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Kataoka, H.; Satoh, Y. Can spatiotemporal 3d cnns retrace the history of 2d cnns and imagenet? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018; pp. 6546–6555. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp.; pp. 770–778.

- Seo, C.; Sabanai, M.; Ogata, H.; Ohya, J. Understanding sprinting motion skills using unsupervised learning for stepwise skill improvements of running motion. International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Cai, M.; Sato, Y. Manipulation-skill Assessment from Videos with Spatial Attention Network. Cornell University - arXiv 2019.

- Doughty, H.; Mayol-Cuevas, W.W.; Damen, D. The Pros and Cons: Rank-Aware Temporal Attention for Skill Determination in Long Videos. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Doosti, B.; Gu, Y.; Cartledge, D.; Crandall, D.J.; Raphael, C. Observing Pianist Accuracy and Form with Computer Vision. Workshop on Applications of Computer Vision 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty, H.; Damen, D.; Mayol-Cuevas, W.W. Who’s Better? Who’s Best? Pairwise Deep Ranking for Skill Determination. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Pan, J.; Yi, H.; Song, Z.; Li, M. Audio-Based Piano Performance Evaluation for Beginners With Convolutional Neural Network and Attention Mechanism. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 2021, 29, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanichraksaphong, V.; Tsai, W.H. Automatic Evaluation of Piano Performances for STEAM Education. Applied sciences 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. Educational Evaluation of Piano Performance by the Deep Learning Neural Network Model. Mobile Information Systems 2022, p. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Koepke, A.S.; Wiles, O.; Moses, Y.; Zisserman, A. Sight to Sound: An End-to-End Approach for Visual Piano Transcription. International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing 2020.

- Parmar, P.; Reddy, J.; Morris, B. Piano skills assessment. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 23rd international workshop on multimedia signal processing (MMSP). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–5.

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglovikov, V.; Shvets, A. Ternausnet: U-net with vgg11 encoder pre-trained on imagenet for image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.05746 2018. arXiv:1801.05746 2018.

- Majkowska, A.; Mittal, S.; Steiner, D.F.; Reicher, J.J.; McKinney, S.M.; Duggan, G.E.; Eswaran, K.; Cameron Chen, P.H.; Liu, Y.; Kalidindi, S.R.; et al. Chest radiograph interpretation with deep learning models: assessment with radiologist-adjudicated reference standards and population-adjusted evaluation. Radiology 2020, 294, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulshan, V.; Peng, L.; Coram, M.; Stumpe, M.C.; Wu, D.; Narayanaswamy, A.; Venugopalan, S.; Widner, K.; Madams, T.; Cuadros, J.; et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. Jama 2016, 316, 2402–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo vadis, action recognition? a new model and the kinetics dataset. In Proceedings of the proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017, pp. 6299–6308.

- Tran, D.; Bourdev, L.; Fergus, R.; Torresani, L.; Paluri, M. Learning spatiotemporal features with 3d convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2015, pp. 4489–4497.

- O’Shaughnessy, D. Speech Communication: Human and Machine; Addison-Wesley series in electrical engineering, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1987.

- Lee, J.; Park, J.; Kim, K.L.; Nam, J. Sample-level deep convolutional neural networks for music auto-tagging using raw waveforms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.01789 2017. arXiv:1703.01789 2017.

- Zhu, Z.; Engel, J.H.; Hannun, A. Learning multiscale features directly from waveforms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.09509 2016. arXiv:1603.09509 2016.

- Choi, K.; Fazekas, G.; Sandler, M. Automatic tagging using deep convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.00298 2016. arXiv:1606.00298 2016.

- Nasrullah, Z.; Zhao, Y. Music artist classification with convolutional recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–8.

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. Neural Information Processing Systems 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv: Learning 2014.

- Carreira, J.; Noland, E.; Hillier, C.; Zisserman, A. A short note on the kinetics-700 human action dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.06987 2019. arXiv:1907.06987 2019.

- Abu-El-Haija, S.; Kothari, N.; Lee, J.; Natsev, P.; Toderici, G.; Varadarajan, B.; Vijayanarasimhan, S. Youtube-8m: A large-scale video classification benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.08675 2016. arXiv:1609.08675 2016.

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. Ieee, 2009, pp. 248–255.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).