Submitted:

05 May 2023

Posted:

06 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cause-related advertising

2.3. Brand Attachment

2.4. Brand Affinity

2.5. Ethical Consumption Propensity

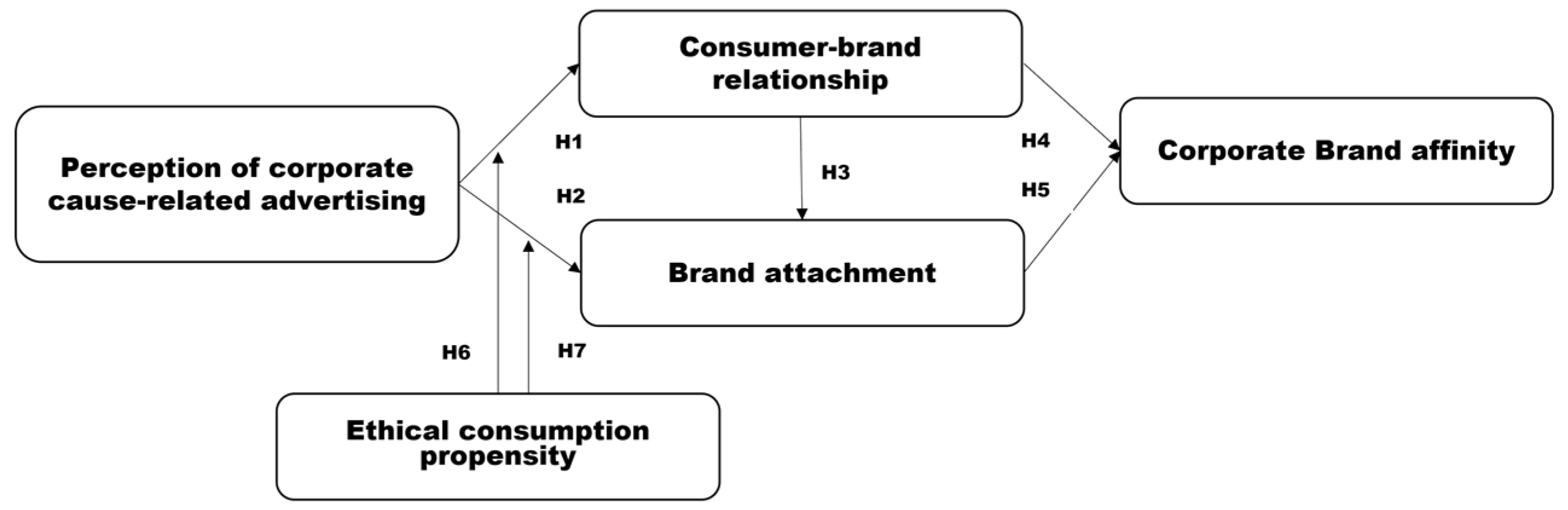

3. Research Model and Hypothesis

3.1. Research model

3.2. Hypotheses

4. Research Methods

4.1. Measures of constructs

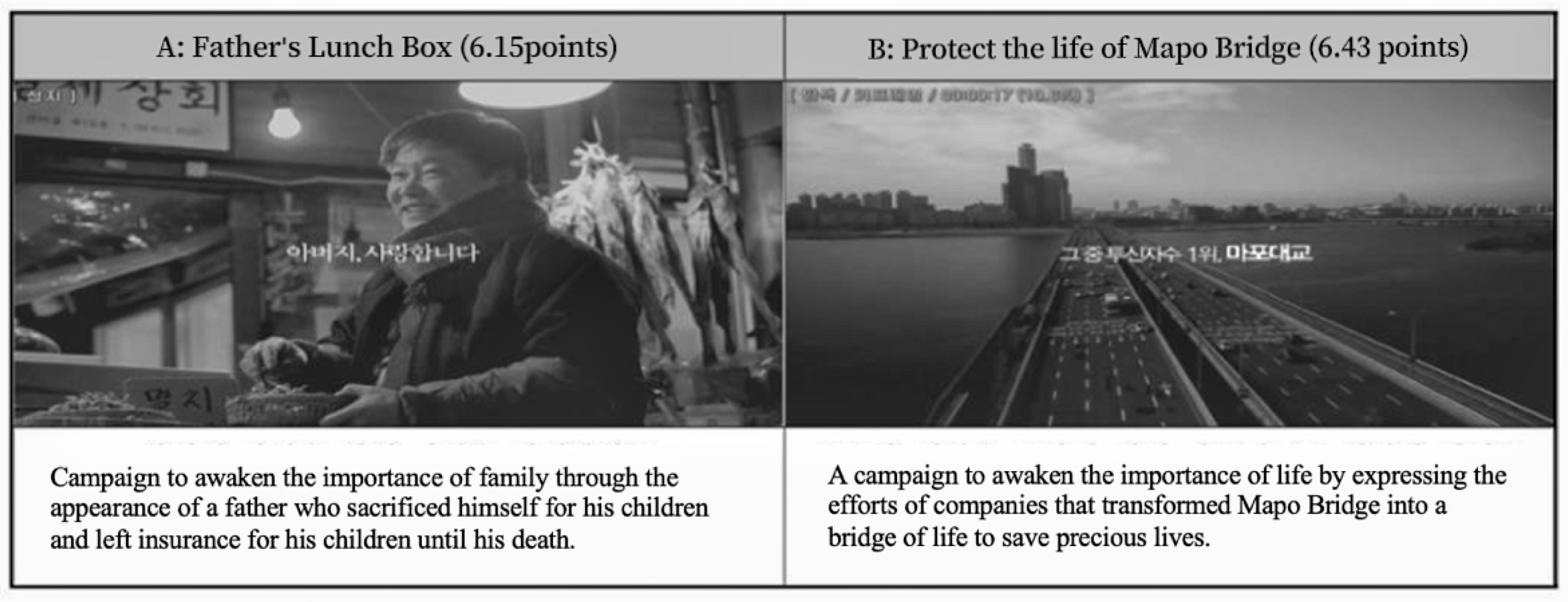

4.2. Research Design

5. Results

5.1. Demographic characteristics of the sample

5.2. Reliability and Validity

5.3. CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis)

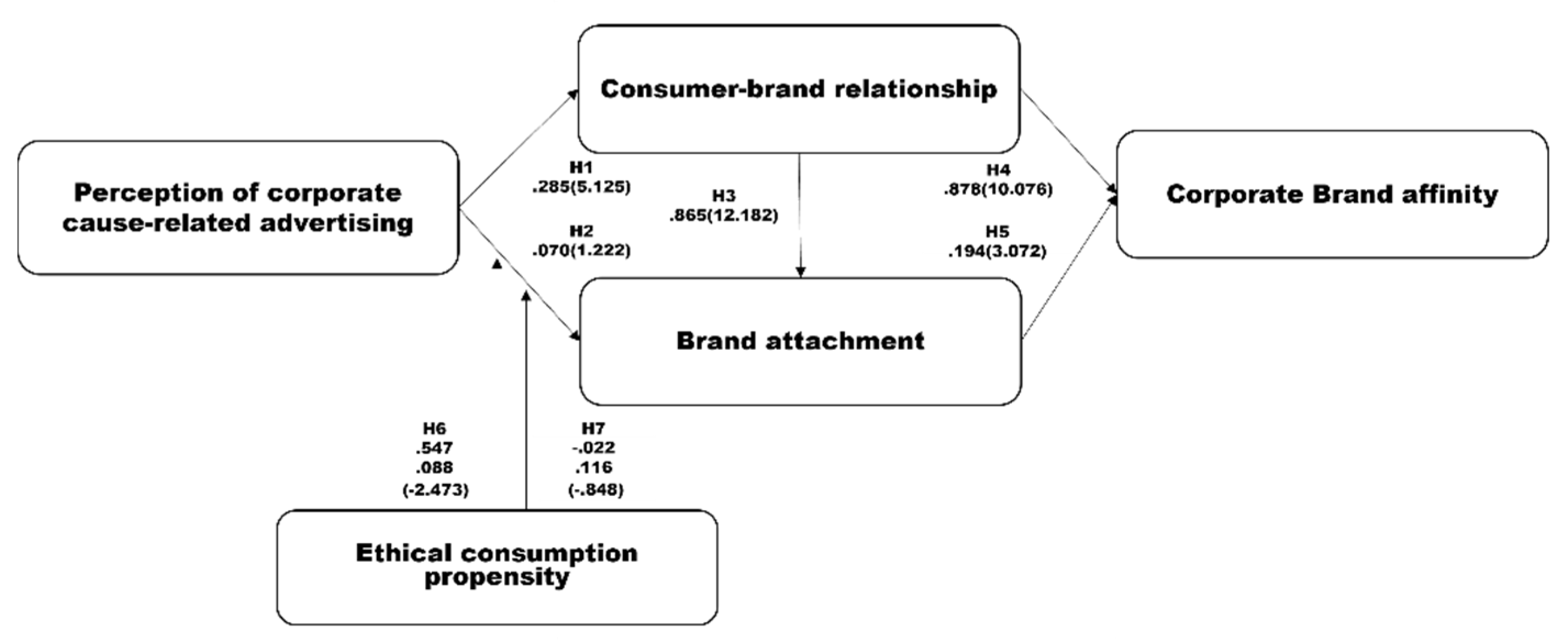

5.4. Structural equation model and hypothesis testing

6. Discussions and Implications

6.1. Discusions

6.2. Implications

Appendix A. Items Used for the Survey Questionnaire

-

Perception of Cause-Related Ads (5 Items)

- I have a good appreciation of cause-related ads.

- I understand the messages conveyed by cause-relate ads

- I appreciate the public consciousness appeal of cause-related ads

- I appreciate the public publc issues raised by cause-related ads

- I appreciate the emotional appeal of cause-related ads

-

Brand Trust (3 Items)

- I believe in the corporate brand implementing cause-related ads

- I take interest in the corporate brand implementing cause-related ads

- I have a faith in the corporate brand implementing cause-related ads

-

Brand Bonding (3 Items)

- I feel intimate about the corporate brand implementing cause-related ads

- I tend to bond with the corporate brand implementing cause-related ads

- I feel pleasant with the corporate brand c

-

Brand Preference (5 Items)

- I want to buy products from a company implementing cause-related ads

- I favor products from a company implementing cause-related ads

- I prefer a company that contributes to public interests.

- I prefer a company that offers good benefits to consumers

- I favor buying products from a company that is socially responsible

-

Brand Attachment (3 Items)

- I have affection for the corporate brand executing cause-related ads

- I feel fascinated by the corporate brand implementing cause-related ads

- I tend to identify well with the corporate brand implementing cause-related ads

-

Brand Affinity (3 Items)

- I intend to continue relationship with the corporate brand

- I feel a certain level of love for the corporate brand

- I intend to make positive word-of-mouth for the corporate brand

-

Ethical Propensity (5 Items)

- I take interests in ethical issues

- I take interests in environmental issues

- I take interests incorporate fairness

- I am interested in taking part in ethical issues

- I have good knowledge of ethical issues

References

- Hajjat, F. M. Using Marketing for Good: An Eexperiential Project on Cause marketing in a Principles Course, Journal of Education for Business 2021, 96, 461-467.

- Tanford, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, E. J. Priming Social Media and Framing Cause marketing to Promote Sustainable Hotel Choice, Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2020, 28, 1762–1781. [CrossRef]

- Rego, M.; Hamilton, M. A.; Rogers, D. Measuring the Impact of Cause marketing: A Meta-Analysis of Nonprofit and For-profit Alliance Campaigns, Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 2021, 33, 434–456. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G. Y.; Liu, H.; Duan, H. W. Cause marketing Strategy in a Supply Chain: A Theoretical Analysis and a Case Study, Advances in Production Engineering & Management 2022, 17, 479–493. [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Dawar, N. Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumers’ Attributions and Brand Evaluations in a Product-Harm Crisis, International Journal of Research in Marketing 2004, 21, 203–217.

- Kim, J. K.; Kim, J. H. Effects of Cause-related Marketing on Consumer Response, The Korean Journal of Advertising 2001, 12, 31–52.

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C. B.; Sen S. Convergence of Interests: Cultivating Consumer Trust through Corporate Social Initiatives, Advances in Consumer Research 2007, 34, 687–692.

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C. B.; Korschun, D. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Strengthening Multiple Stakeholder Relationships, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2006, 34, 158–166.

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management (Millennium ed.), Prentice Hall International, 2010.

- Howie, K. M.; Yang, L.; Vitell, S. J.; Bush, V.; Vorhies, D. Consumer Participation in Cause marketing: An Examination of Effort Demands and Defensive Denial, Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 147, 679 – 692.

- Barone, M. J.; Miyazaki, A. D.; Taylor K. A. The Influence of Cause-related Marketing on Consumer Choice: Does One Good Turn Deserve Another?, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2000, 28, 248–262.

- Sindhu, S. Cause marketing; an Interpretive Structural Model Approach, Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 2022, 34 (1), 102-128.

- Gao, Y.; Wu, L.; Shin, J.; Mattila, A. S. Visual Design, Message Content, and Benefit Type: The Case of a Cause marketing Campaign, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2020, 44, 761–779.

- Choi, J.; Seo, S. When a Stigmatized Brand is Doing Good: The Role of Complementary Fit and Brand Equity in Cause marketing, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2019, 31, 3447-3464.

- Um J. Y.; Jang J. O. Content Analysis of Korean Cause-related marketing Research: Focusing on Content Analysis of Papers Published from 2000 to 2012, Studies of Corporate Business 2013, 20, 155–174.

- Gu J. O.; Lee H. B. The Effect of Cause-related Marketing Activities on Purchase Intention: Focusing on the Mediating Role of Corporate Legitimacy, Journal of the Korean Business Society 2015, 28, 3211–3233.

- Choi J. Y.; Choi Y. S. A Study on the Impact of Cause-related Marketing (CRM) Messages on Product Evaluation: Journal of Consumer Studies 2011, 22, 115–13.

- Yoon J. H. Effect of Cause-Related Advertising Frame on Authenticity and Corporate Attitude. Ph.D. thesis, graduate school of Geumo-gong University 2014.

- Jung E. H. The Influence of Moral Identity on the Attitude of Everland in Cause-related Marketing: Focusing on the Mediating Role of Pride. Master's thesis, Hongik University Graduate School, Seoul 2014.

- Shin H. C. A Study on the Effectiveness of Cause marketing of Restaurant Enterprises, Research on Tourism Management 2018, 86, 541–559.

- Yoo G. H.; Song J. D. A Study on the Effect of the Prominence and Symbolism of Public Interest Attributes on Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention in Cause-related Marketing, Customer Satisfaction Management Research 2018, 20, 127–151.

- Shin H. B. The Effect of How Much Contribution of Cause-related Goods is Revealed on Purchase Intention: Focusing on the Moderating Effect of One's Level of Food and Consumption Tendency. Master's thesis, Sungkyunkwan University Graduate School, Seoul 2019.

- Park J. G.; Lee Y. H.; Yoo W. S.; Hyun H. W. A Corporate Credit Interest-linked Marketing is a Consumer's Evaluation and Purchase Intention, Journal of Commodity Studies 2017, 35, 1–11.

- Brown, T. J.; Dacin, P. A. The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses, Journal of Marketing 1997, 61(January), 68-84.

- Aaker, D.; Schmitt, B. The Influence of Culture on the Self-Expressive Use of Brands, Working Paper, 274, UCLA Anderson Graduate School of Management, 1997.

- Homans, G. C. Social behavior as exchange, American Journal of Sociology 1958, 63, 597–606.

- Emerson, R. Power-dependence relations, American Sociological Review 1962, 27, 31–41.

- Blau, P. M. Exchange and power in social life, New York: Wiley, 1964.

- Lichtenstein, D. R.; Drumwright, M. E.; Braig, B. M. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Donations to Corporate-Supported Nonprofits, Journal of Marketing 2004, 68(October), 16-33.

- Jang, S.H. Corporate Authenticity Management and Its Benefits, I. 2009.

- Giertz, J. N.; Hollebeek, L. D.; Weiger, W. H.; Hammerschmidt, M. The invisible leash: when human brands hijack corporate brands' consumer relationships, Journal of Service Management 2022, 33, 485-495.

- Polat, A. S.; Çetinsöz, B. C. The Mediating Role of Brand Love in the Relationship Between Consumer-Based Brand Equity and Brand Loyalty: a Research on Starbucks, Journal of Tourism & Services 2021, 12, 150-167.

- Quezado, T.C.C.; Fortes, N.; Cavalcante, W.Q.F. The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Ethics on Brand Fidelity: The Importance of Brand Love and Brand Attitude. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2962.

- Lin, Y.; Choe, Y.; Impact of Luxury Hotel Customer Experience on Brand Love and Customer Citizenship Behavior, Sustainability 2022, 14, 13899.

- Fournier, S. Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research, Journal of Consumer Research 1998, 24, 343–373.

- Lee, H. S.; Choi, J. I.; Lim, J. H. Its Role in the Consumer-Brand Relationship: Brand`s Attitude toward Consumer`s Purchasing Behavior, Journal of Consumer Studies 2004, 15, 85–108. Aker, D.; Schmitt, B. The Influence of Culture on the Self-Expressive Use of Brands, Working Paper, 274, UCLA Anderson Graduate School of Management, 1997.

- Papadatos, C. The Art of Storytelling: How Loyalty Marketers can Build Emotional Connections to Their Brands, Journal of Consumer Marketing 2006, 23, 382–384.

- Kim, H. S.; Lee, H. W. A Study on the OPR Measurement Scale Reflecting Korean Culture, Korean Journal of Advertising 2008, 10, 99–139.

- Hon, L. C.; Grunig, J. E. Guidelines for Measuring Relationships in Public Relations, Gainesville, FL: The Institute for Public Relations, 1999.

- Lee, D. G. The Effects of Organization-Public Relationships on the fire authorities Image, Korean policy sciences review 2005, 9, 47-64.

- Lee, S. B.; Shin, S. H.; Choi, W. S. The Effects of Civil Relationships on City Image, Korean Journal of Advertising 2004, 5, 7–31.

- Jung, S. K.; Seo, H. S.; Byun, J. W. The Effects of the Travel Agent Website User`s Organization-Public Relationship on the Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty, International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 2007, 21, 19–37.

- Ball, A. D.; Tasaki L. H. The Role and Measurement of Attachment in Consumer Behavior, Journal of Consumer Psychology 1992, 1, 155–172.

- Sung, Y. S.; Han, M. K.; Park, E. A. Influence of Brand Personality on Brand Attachment, Korean Journal of Consumer and Advertising Psychology 2004, 5, 15–34.

- Margarida A. H.; Sousa, B.; Carvalho, A.; Santos, V.; Lopes D., Á.; Valeri, M. Encouraging brand attachment on consumer behaviour: Pet-friendly tourism segment, Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing 2022, 8, 16-24.

- Lee, C. H.; Kim, H. R. Positive and negative switching barriers: promoting hotel customer citizenship behaviour through brand attachment, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2022, 34, 4288-4311.

- Lee, S. H; Kim, M. Y. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Attachment and Brand Equity, The Research Journal of the Costume Culture 2006, 14, 684–697.

- Thomson, D.; MacInnis, J.; Park, C. W. The Ties That Bind: Measuring the Strength of Consumers’ Attachments to Brands, Journal of Consumer Psychology 2005, 15, 77–91.

- Han, S. S.; Yeom, S. W. A Preliminary Study on the Formative Path of Brand Attachment: With Focus on the Developing a Hypothetical Path Model, Korean Journal of Advertising 2006, 8, 167–200.

- Kim, Y. K.; Yu J. P. An Exploratory Study on Influence Factor of Service Brand Attachment, Journal of the Korea Service Management Society 2007, 8, 185–218.

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M. S. The Different Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Relationships, Journal of Marketing 1999, 63, 70–87.

- Caruana, A. Service Loyalty: The Effects of Service Quality and the Mediating Role of Customer Satisfaction, European Journal of Marketing 2002, 36, 811-828.

- Park, G. j.; Jung, K. H.; Park, S. Y. The Effect of Channel Equity on Private Brand Image and Purchase Intent, Korea Research Academy of Distribution and Management Review 2011, 14, 27–50.

- Bowen, J. T.; Chen S. L. The Relationship Between Customer Loyalty and Customer Satisfaction, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2001, 13, 213–217.

- Dick, A.; Basu, K. Customer Loyalty: Towards an Integrated Framework, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 1994, 22, 99–113.

- Huh, E. J. Determinants of Consumer's Attitude and Purchase Intention on the Ethical Products, Journal of Consumer Studies 2011, 22, 89–111.

- Doane, D. Taking Flight: The Rapid Growth of Ethical Consumerism, New Economics Foundation: London. 2001.

- Langen, N. Are Ethical Consumption and Charitable Giving Substitutes or not? Insights into Consumers’ Coffee Choice, Food quality and preference 2011, 22, 412-421.

- Toms M. M.; Romont, A. I.; Scridon, M. A. Is Sustainable Consumption Translated into Ethical Consumer Behavior?, Sustainability 2021, 13, 3466.

- Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ivan, K. W. L. The Ethical Judgment and Moral Reaction to the Product-Harm Crisis: Theoretical Model and Empirical Research, Sustainability 2016, 8, 626.

- Oh, J.; Yoon, S. Theory-based Approach to Factors Affecting Ethical Consumption, International Journal of Consumer Studies 2014, 38, 278–288.

- Ko, A. R. Ethical Consumer Behavior in Korea: Current Status and Future Prospects, Journal of The Korean Society of clothing and Textiles 2009, 6, 54–62.

- Stem, P. C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value Orientations, Gender, and Environmental Concern, Environment and Behavior 1993, 25, 322–348.

- Yoon, G.; Jo, J. S. Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Multiple Stakeholder Relationships, The Korean Journal of Advertising 2007, 18, 241–255.

- Kim, J. H. Influence of Consistency and Distinction Attribution of Corporate's Cause-related Behavior on Attitude toward Corporate”, Korean Journal of Consumer and Advertising Psychology 2005, 6, 27–44.

- Murray, K.; Vogel, C. Using a Hierarchy-of-Effects Approach to Gauge the Effectiveness of Corporate Social Responsibility to Generate Goodwill Toward the Firm: Financial versus Nonfinancial Impacts, Journal of Business Research 1997, 38, 141–159.

- Ji, S. G. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Equity, The Korean Academic Association of Business Administration 2010, 23, 2251–2269.

- Bhattacharya, C. B.; Sen S. Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why and How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Initiatives, California Management Review 2004, 47, 9–25.

- Mohr, A.; Webb, D. J. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility and Price on Consumer Responses, The Journal of Consumer Affairs 2005, 39, 121–147.

- Kim, S. E.; Jeong, M. S. The Effects of Perceived Internet Fashion Shopping Mall Characteristics on Positive Shopping Emotion and Relationship Quality, The Research Journal of the Costume Culture 2009, 22, 73–85.

- Franz-Rudolf, E.; Tobias, L.; Bernd, H. S.; Patrick, G. “Are Brands Forever? How Brand Knowledge and Relationships Affect Current and Future Purchases, Journal of Product & Brand Management 2006, 15, 98–105.

- Lee, I. S.; Lee, K. H.; Choi, J. W.; Yang, S. H.; Lim, S. T. S.; Jeon, W.; Kim, J. W.; Hong, S. J. Theoretical Integration of User Satisfaction and Emotional Attachment, Korean Management Review 2008, 37, 1171–1203.

- Holbrook, M. B. The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty, Journal of Marketing 2001, 65, 81–93.

- Chatterjee, P. Online Review: Do Consumers Use Them, Advances In Consumer Research 2005, 28, 129–133.

- Kang, J. H.; Joen, I. K. The Effect of Online-Sports Brand Community Characteristics on Commitment, Brand Attitude and Brand Loyalty, Journal of Korean Society for Sports Management 2009, 14, 117–131.

- Kim, G. S. A Study on Satisfaction and Purchasing Behavior of Korean Herbal Cosmetics of City Female Consumers, Journal of Korean Beauty Society 2008, 14, 1443–1459.

- Choi, S. M. The Effect of Shopping Tourists’ Emotional Consumption Tendencies on Luxury Brand Attachment and Loyalty: A Moderating Effect of Brand Benefit, Korean Journal of Industry and Innovation 2008, 27, 197–219.

- Yoo, K. S.; Ha, D. H. The Relationship among Relational Benefits, Brand Attachment, and Brand Loyalty in the Family Restaurant, Korean Journal of Tourism Research 2011, 26, 363–381.

- Kim, H. R.; Hong, S. M.; Lee, M. K. Consumer Evaluations of Convergence Products, Korean Journal of Marketing 2005, 7, 1–20.

- Ahn, K. H.; Lee, J. E.; Jeon, J. E. The Effects of Luxury Brand-Self Identification on Brand Attachment and Brand Commitment-The Moderating Role of Regulatory Focus, Korean Journal of Marketing 2009, 4, 1–33.

- Hofmann, W.; Schmeichel, B. J.; Baddeley, A. D. Executive Functions and Self-Regulation, Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2012, 16, 174–180.

- Matsunaga, M. Item Parceling in Structural Equation Modeling: A Primer, Communication Methods and Measures 2008, 2, 260–293.

- Rogers, W. M.; Schmitt, N. Parameter Recovery and Model Fit Using Multidimensional Composites: A Comparison of Four Empirical Parceling Algorithms, Multivariate Behavioral Research 2004, 39, 379–412.

- Podsakoff, P. M.; MacKenzie, S. B.; Lee, J. Y. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies, Journal of Applied Psychology 2003, 88, 879–903.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error, Journal of marketing research 1981, 18, 39–50.

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C. M.; Sarstedt, M. a New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modeling, Journal of the academy of marketing science 2015, 43, 115–135.. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. On the Maximum Likelihood Estimation for a Normal Distribution under Random Censoring, Communications for Statistical Applications and Methods 2018, 25, 647–658. [CrossRef]

| Ind. variables | Item | Scale items | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of cause-related advertisement | The degree of understanding of advertising, the degree of understanding of advertising messages, the degree of understanding of advertising’s public consciousness, and the degree of public awareness of overall ad | Lichenstein et al. (2004), Kim & Kim (2001) | |

| Consumer brand relationship | Trust | The degree of brand trust, the degree of brand belief, and the degree of understanding of the brand | Kim & Lee (2008), Lee (2005) |

| Bonding | Intimacy of the brand’s experience, the degree of bond with the brand, the degree of pleasant feelings toward the brand | ||

| Preference | The degree of approval for brand purchase, the degree of favorability for the brand, the degree of assessing the brands’ contribution to the public interest, the degree of contribution of the brand’s consumer benefits, and the degree of consumer’s favorability for brand purchase | ||

| Brand attachment | The degree of affection for the brand, the degree of interest in the brand, the degree of brand fascination, the degree of brand-self-identity, the degree of brand affection, the degree of brand need | Han & Um (2006), Kim & Woo (2007) | |

| Corporate brand affinity | The degree of intention to continue the transaction relationship, the degree of love for the company, and the intention for positive word of mouth | Lee et al. (2006), Bowen & Chen (2001) | |

| Ethical consumption propensity | Degree of interest in ethical issues, degree of interest in environmental issues, degree of interest in corporate fairness, degree of participation in ethical issues, degree of knowledge of ethical issues | Heo (2011), Oh & Yoon (2014) | |

| Characteristics | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 94 | 29.0 |

| Woman | 230 | 71.0 | |

| Sum | 324 | 100 | |

|

Previous participation in social activities |

Yes. | 124 | 38.3 |

| No. | 200 | 61.7 | |

| Sum | 324 | 100 | |

| Age | Under 20 | 287 | 88.6 |

| 20 ~ 30 | 13 | 4.0 | |

| 31 ~ 40 | 9 | 2.8 | |

| Over 40 | 15 | 4.6 | |

| Sum | 324 | 100 | |

| Marriage whether | Married | 40 | 12.3 |

| Single | 284 | 87.7 | |

| Sum | 324 | 100 | |

| Factor | Items | Affinity | Preference | Ethical Propensity | Trust | Bonding | Attachment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity | Affinity2 Affinity5 Affinity3 Affinty4 Affinity1 Affinity6 |

.829 .814 .811 .790 .762 .680 |

.282 .189 .230 .002 .344 .236 |

.058 .158 .066 .082 .119 .041 |

.153 .182 .260 .217 .032 .229 |

.150 .157 .155 .244 .187 -.080 |

.100 .173 .136 .137 .123 .175 |

| Preference | Peference1 Preference 2 Relation3 Relation4 Preference 5 |

.221 .200 .285 .320 .252 |

.855 .853 .822 .702 .642 |

.121 .081 .106 .067 .098 |

.212 .178 .215 .300 .068 |

.153 .169 .206 .229 .558 |

.151 .173 .182 .174 .163 |

| Ethical Propensity | Propensity2 Propensity 4 Propensity 3 Propensity 1 Propensity5 |

.074 .098 .070 .063 .049 |

.026 .061 .063 .050 .132 |

.842 .841 .838 .815 .768 |

.011 .029 .036 -.015 .174 |

.033 .154 .073 -.019 -.011 |

-.018 .124 .132 .054 -.089 |

| Trust | Trust10 Trust11 Trust9 |

.313 .289 .278 |

.226 .237 .338 |

.088 .079 .073 |

.823 .777 .748 |

.200 .146 .228 |

.100 .244 .167 |

| Bonding | Bonding7 Bonding8 Bonding6 |

.210 .332 .291 |

.495 .320 .480 |

.077 .113 .111 |

.268 .360 .287 |

.712 .683 .654 |

.175 .162 .191 |

| Attachment | Favorite3 Favorite2 Favorite1 |

.320 .392 .276 |

.326 .247 .525 |

.123 .047 .102 |

.211 .384 .153 |

.203 .159 .168 |

.740 .657 .647 |

| Eigen value | 4.867 | 4.652 | 3.552 | 2.815 | 2.270 | 1.898 | |

| Cumulative variance ratio | 19.470 | 38.078 | 52.284 | 63.546 | 72.626 | 80.218 | |

| Cronbach Alpha | .924 | .942 | .884 | .915 | .933 | .886 | |

| CR | .702 | .756 | .851 | .794 | .859 | .788 | |

| AVE | .434 | .646 | .707 | .526 | .552 | .699 | |

| Perception | Preference | Trust | Bonding | Attach | Affinity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception | .659 | |||||

| Preference | .227** | .804 | ||||

| Trust | .240** | .792** | .841 | |||

| Bonding | .205** | .624** | .661** | .725 | ||

| Attach | .226** | .591** | .609** | .610** | .743 | |

| Affinity | .224** | .701** | .686** | .656** | .655** | .836 |

| Perception | Preference | Trust | Bonding | Attach | Affinity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception | - | |||||

| Preference | .79 | - | ||||

| Trust | .81 | .80 | - | |||

| Bonding | .75 | .84 | .82 | - | ||

| Attach | .78 | .83 | .75 | .82 | - | |

| Affinity | .70 | .79 | .73 | .72 | .83 | - |

| Item | FL | SL | SE | t | Model-Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception2 Perception 3 Perception 4 |

.779 .923 1.000 |

.685 .871 .812 |

.060 .055 |

12.783 16.749 |

X2=172.880, df=59 .155 GFI=.919, AGFI=.875, NFI=.941, CFI=.960, IFI=.961, TLI=.947, SRMR=.069, RMSEA=.077 |

| Relation-Trust Relation-Boding Relation-Preference |

1.000 .957 .906 |

.921 .845 .817 |

.059 .044 |

16.438 20.752 |

|

| Affinity2 Affinity4 Affinity5 Affinity6 |

.892 .863 1.000 .948 |

.858 .794 .933 .916 |

.046 .05 .061 |

19.679 17.869 15.42 |

|

| Attachment3 Attachment 2 Attachment 1 |

.917 1.000 .850 |

.874 .922 .796 |

.049 .047 |

18.848 18.431 |

| Hypo | Path | Estimate | S.E | C.R. | P | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Cause-related ad perception→Consumer brand relationship | .285 | .056 | 5.125 | .000 | Adoption |

| H2 | Cause-related ad perception→Brand Attachment | .070 | .058 | 1.222 | .207 | Rejected |

| H3 | Consumer brand relationship→Brand attachment | .865 | .071 | 12.182 | .000 | Adoption |

| H4 | Consumer brand relationship→Corp brand affinity | .878 | .087 | 10.076 | .000 | Adoption |

| H5 | Brand attachment→Corporate brand affinity | .194 | .063 | 3.072 | .002 | Adoption |

| Path | Group | Estimate | S.E | C.R. | P | z-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of cause-related ad– Consumer brand relationship | High group | .547 | .169 | 3.233* | .001 | -2.473 |

| Low group | .088 | .076 | 1.163 | .245 | ||

| Perception of cause-related ad – Brand attachment | High group | -.022 | .123 | -.175 | .861 | .848 |

| Low group | .116 | .106 | 1.099 | .272 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).