Submitted:

29 April 2023

Posted:

29 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

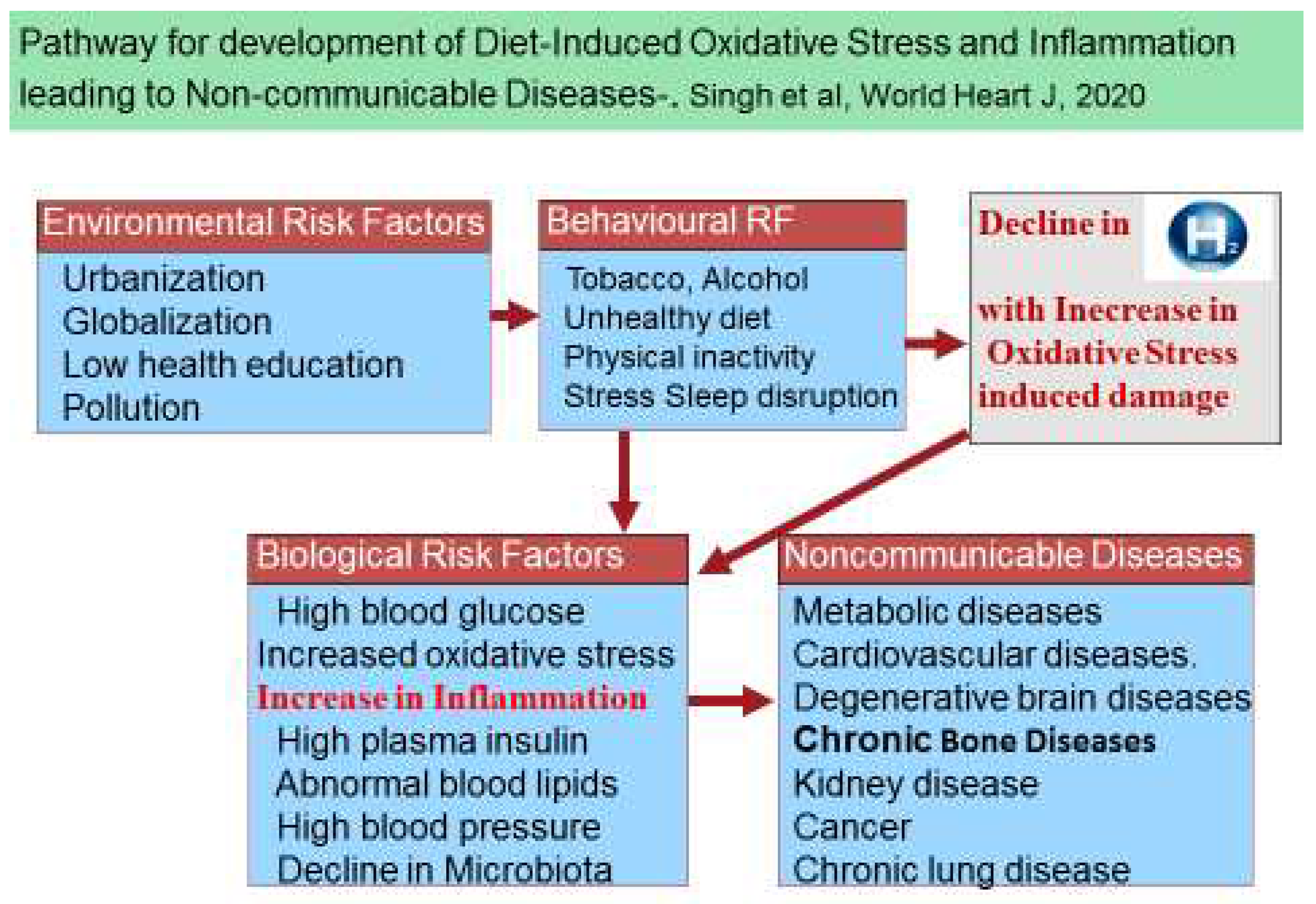

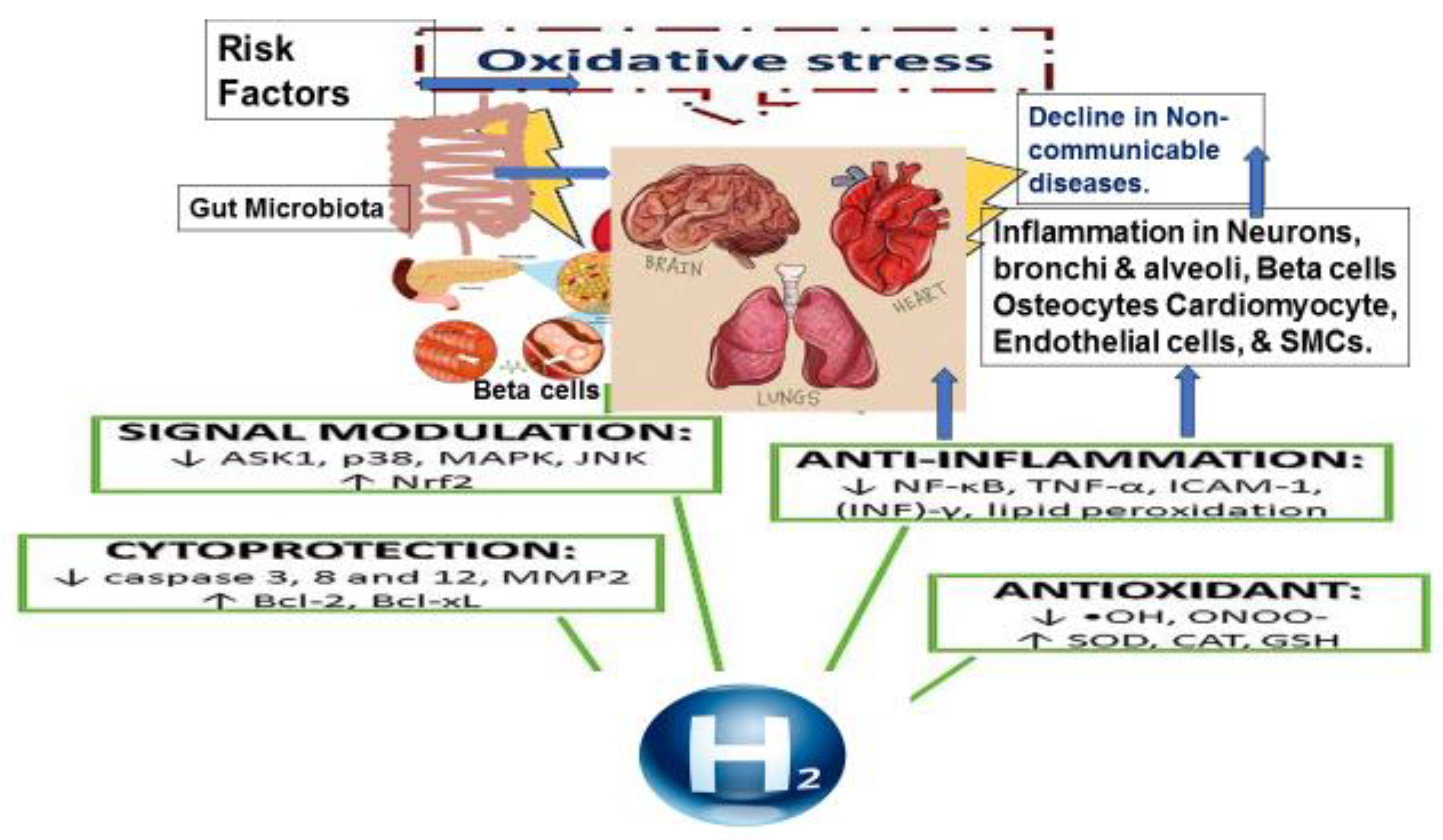

Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Diseases

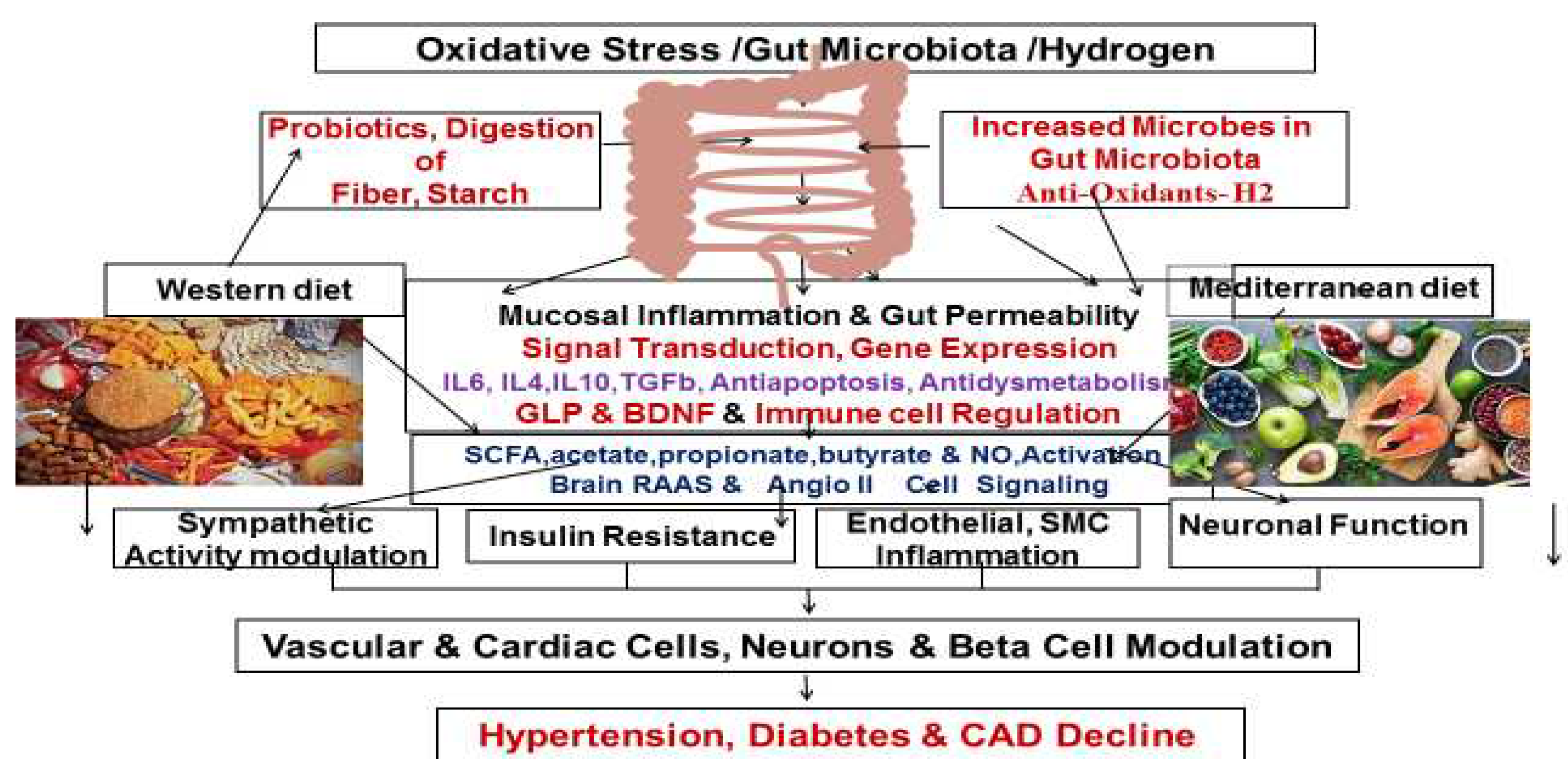

Physiology of Molecular Hydrogen and the Gut Microbiota

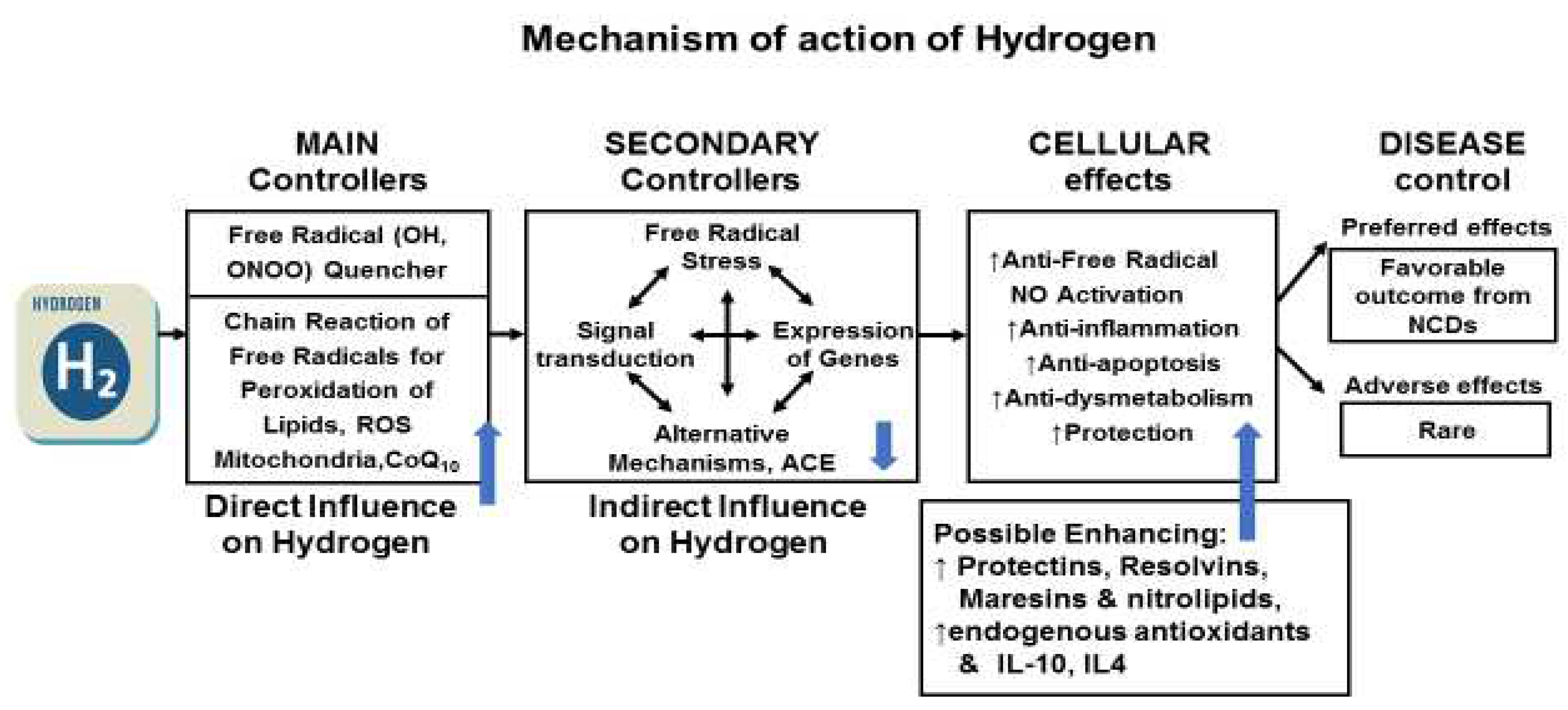

Molecular Hydrogen; A New Therapeutic Agent

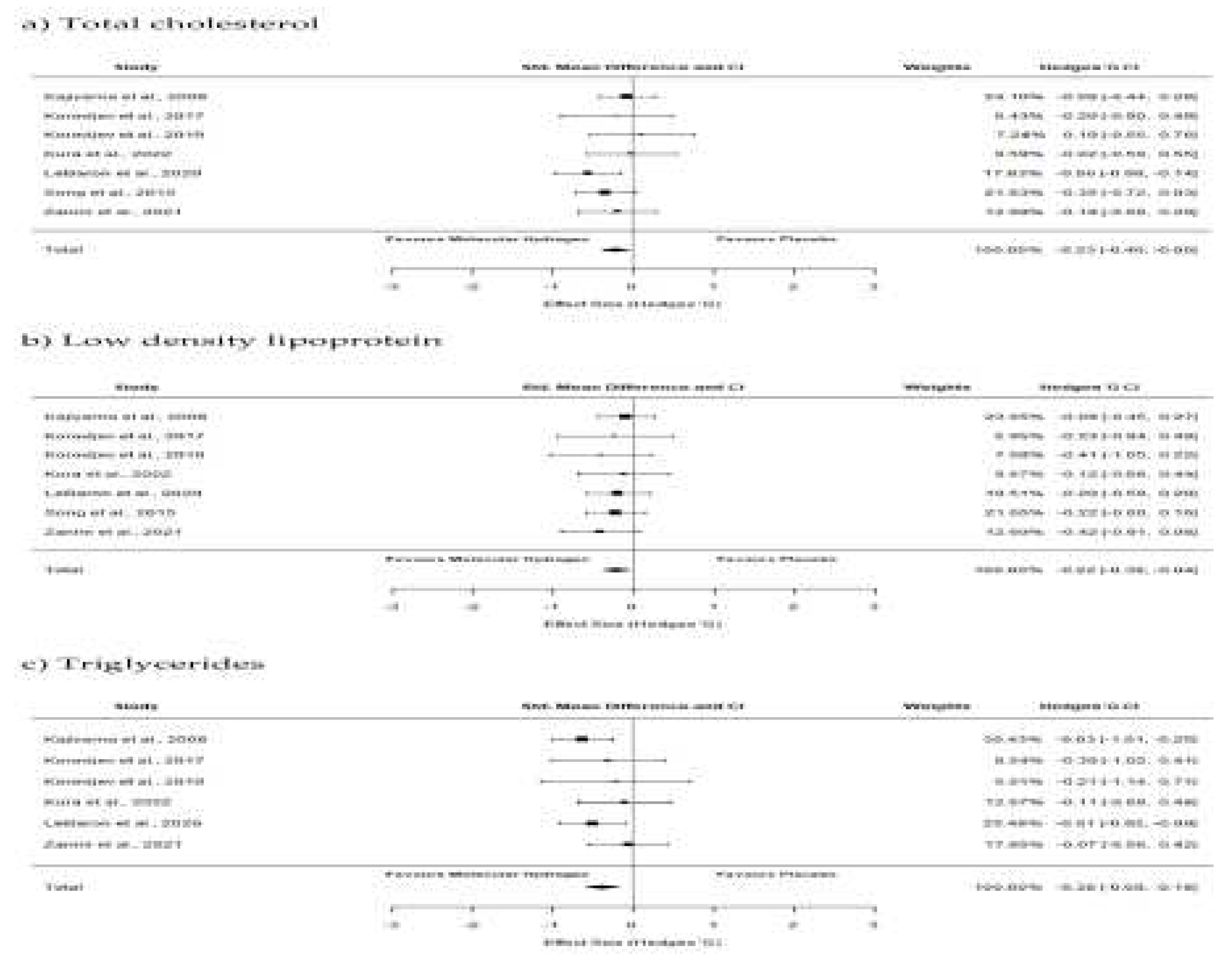

Effects of Hydrogen Therapy on Blood Lipids

Effects of Hydrogen Therapy on Blood Pressures

Effects of Hydrogen Therapy on Endothelial Function

Effects of Molecular Hydrogen in Stroke

Effects of Molecular Hydrogen on Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury

Effects of Hydrogen Therapy in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Effects of Molecular Hydrogen on Bone and Joint Diseases

Effects of Hydrogen on Cancer

Effects of Hydrogen Therapy in Kidney Diseases

Effects of Hydrogen in Chronic Lung Diseases

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:2982–3021. [CrossRef]

- Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392:1736–88. [CrossRef]

- 3. Vaduganathan M, Mensah GA, Varieur Turco J, et al. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk: A Compass for Future Health. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 12 December. [CrossRef]

- Jiang S, Liu H, Li C. Dietary regulation of oxidative stress in chronic metabolic diseases. Foods. 2021 Aug 11;10(8):1854. [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, K.; Koelman, L. Rodrigues CE. Dietary patterns and biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation: A systematic review of observational and intervention studies. Redox Biology 2021, 42, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micha R, Penalyo JL, Cidhea F, Imamura F, Rehm CD, Mozaffarian D. Association between dietary factors and mortality from heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017; 317 (9): 912-924. [CrossRef]

- Sacco RL, Roth GA, Reddy KS, Arnett DK, Bonita R, Gaziano TA, Heidenreich PA, Huffman MD, Mayosi BM, Mendis S, Murray CJL, Perel P, Piñeiro DJ, Smith SC Jr, Taubert KA, Wood DA, Zhao D, Zoghbi WA. The heart of 25 by 25: achieving the goal of reducing global and regional premature deaths from cardiovascular diseases and stroke: a modeling study from the American Heart Association and World Heart Federation. Circulation 2016; 133: e674-e690. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Fedacko, J.; Fatima, G.; Magomedova, A.; Watanabe, S.; Elkilany, G. Why and How the Indo-Mediterranean Diet May Be Superior to Other Diets: The Role of Antioxidants in the Diet. Nutrients 2022; 14, 898. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Fedacko, J.; Pella, D.; Fatima, G.; Elkilany, G.; Moshiri, M.; Hristova, K.; Jakabcin, P.; Vanova, N. High Exogenous Antioxidant, Restorative Treatment (Heart) for Prevention of the Six Stages of Heart Failure: The Heart Diet. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojto, V.; Singh, R.B.; Gvozdjakova, A.; Pella, D.; Fedacko, J.; Pella, D. Molecular hydrogen: a new approach for the management of cardiovascular diseases. World Heart J 2018, 10, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa Y, Yamamoto H, Hirano Si, Sato B, Takefuji Y, Satoh F. The overlooked benefits of hydrogen-producing bacteria. Med Gas Res 2022;12. Available online: https://www.medgasres.com/preprintarticle.asp?id=344977 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Slezák, J.; Kura, B.; Frimmel, K.; Zálešák, M.; Ravingerová, T.; Viczenczová, C.; Okruhlicová, Ľ.; Tribulová, N. Preventive and therapeutic application of molecular hydrogen in situations with excessive production of free radicals. Physiol. Res. 2016, 65 (Suppl. 1), S11–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, T.; Sato, B.; Hara, K.; Hara, Y.; Naritomi, Y.; Koyanagi, S.; Hara, H.; Nagao, T.; Ishibashi, T. Consumption of water containing over 3.5 mg of dissolved hydrogen could improve vascular endothelial function. Vascular Health and Risk Management 2014, 10, 591–597. [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara, M.; Sobue, S.; Ito, M.; Ito, M.; Hirayama, M.; Ohno, K. Beneficial biological effects and the underlying mechanisms of molecular hydrogen- Comprehensive review of 321 original articles. Med. Gas Res. 2015, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A, Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacognosy Reviews 2010; 4 (8): 118-126. [CrossRef]

- Takac, I.; Schroder, K.; Brandes, R.P. The Nox family of NADPH oxidases: friend or foe of the vascular system. Curr Hypertens Rep 2012, 14, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Reactive oxygen species and endothelial function role of nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and Nox family nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2012, 110, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghouleh, I.; Khoo, N.K.; Knaus, U.G. Oxidases and peroxidases in cardiovascular and lung disease: new concepts in reactive oxygen species signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 2011, 51, 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, K.; Krause, K.H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2007, 87, 245–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryugina AV, Danilova DA, Brichkin YD, Taranov EV, Nazarov EI, Pichugin VV, Medvedev AP, Riazanov MV, Fedorov SA, Andrej YS, Makarov EV. Molecular hydrogen exposure improves functional state of red blood cells in the early postoperative period: a randomized clinical study.Med Gas Res. 2023 Apr-Jun;13(2):59-66. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Dong Y, He Q, et al. Hydrogen: a novel option in human disease treatment. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:8384742. /: https. [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa I, Ishikawa M, Takahashi K, et al. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat Med. 2007;13(6):688-694. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Feng J, Lian N, et al. Hydrogen gas alleviates blood-brain barrier impairment and cognitive dysfunction of septic mice in an Nrf2-dependent pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020, 85, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie C, Zou R, Pan S, A R, Gao Y, Yang H, Bai J, Xi S, Wang X, Hong X, Yang W. Hydrogen gas inhalation ameliorates cardiac remodelling and fibrosis by regulating NLRP3 inflammasome in myocardial infarction rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2021 Sep;25(18):8997-9010. [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, T.; Singh, R.B.; Fatima, G.; Kartikey, K.; Sharma, J.P.; Ostojic, S.M.; Gvozdjakova, A.; Kura, B.; Noda, M.; Mojto, V.; Niaz, M.A.; Slezak, J. The Effects of 24-Week, High-Concentration Hydrogen-Rich Water on Body Composition, Blood Lipid Profiles and Inflammation Biomarkers in Men and Women with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. 2020, 13, 889–896. [CrossRef]

- Singh RB, Halabi G, Fatima G, Rai RH, Tarnava AT, LeBaron TW. Molecular hydrogen as an adjuvant therapy may be associated with increased oxygen saturation and improved exercise tolerance in a COVID-19 patient. Clin Case Reports 9: e05039. | 1 of 6. [CrossRef]

- Akita Y, Higashiyama M, Kurihara C, Ito S, Nishii S, Mizoguchi A, Inaba K, Tanemoto R, Sugihara N, Hanawa Y, Wada A, Horiuchi K, Okada Y, Narimatsu K, Komoto S, Tomita K, Takei F, Satoh Y, Saruta M, Hokari R. Ameliorating Role of Hydrogen-Rich Water Against NSAID-Induced Enteropathy via Reduction of ROS and Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids.Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Dec 7:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Koyama Y, Harada S, Sato T, Kobayashi Y, Yanagawa H, Iwahashi T, Tanaka H, Ohata K, Imai T, Ohta Y, Kamakura T, Kobayashi H, Inohara H, Shimada S. Therapeutic strategy for facial paralysis based on the combined application of Si-based agent and methylcobalamin. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2022 Nov 21;32:101388. [CrossRef]

- Hong Y, Dong G, Li Q, Wang V, Liu M, Jiang G, Bao D, Zhou J. Effects of pre-exercise H2 inhalation on physical fatigue and related prefrontal cortex activation during and after high-intensity exercise. Front Physiol. 2022 Sep 2;13:988028. eCollection 2022. [CrossRef]

- Eda, N.; Tsuno, S.; Nakamura, N.; Sone, R.; Akama, T.; Matsumoto, M. Effects of IntestinalBacterial Hydrogen Gas Production on Muscle Recovery following Intense Exercise in Adult Men: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry RJ, Peng L, Barry NA, Cline GW, Zhang D, Cardone RL, Petersen KF, Kibbey RG, Goodman AL, Shulman GI. Acetate mediates a microbiome–brain–β- cell axis to promote metabolic syndrome. Nature 2016; 534: 213-217. [CrossRef]

- De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Goncalves D, Vinera J, Zitoun C, Duchampt A, Bäckhed F, Mithieux G. Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut-brain neural circuits. Cell 2014; 156: 84-96. [CrossRef]

- Levitt, MD. Excretion of hydrogen gas in man. N Engl J Med 1969; 281: 122-127. [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012; 10 (10): 717–725. [CrossRef]

- Lupp, C.; Robertson, M.L.; Wickham, M.E.; Sekirov, I.; Champion, O.L.; Gaynor, E.C.; Finlay, B.B. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe 2007, 2, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, S.M. Introduction to the special focus issue on the impact of diet on gut microbiota composition and function and future opportunities for nutritional modulation of the gut microbiome to improve human health. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBaron TW, Kura B, Kalocayova B, Tribulova N, Slezak J. A New Approach for the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disorders. Molecular Hydrogen Significantly Reduces the Effects of Oxidative Stress. Molecules 2019; 24(11): 276. [CrossRef]

- LeBaron TW, Sharpe R, Ohno K. Electrolyzed-Reduced Water: Review I. Molecular Hydrogen Is the Exclusive Agent Responsible for the Therapeutic Effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Nov 25;23 (23):14750. [CrossRef]

- Baptista LC, Sun Y, Carter CS, Buford TW. Crosstalk Between the Gut Microbiome and Bioactive Lipids: Therapeutic Targets in Cognitive Frailty. Front Nutr. 2020 Mar 11;7:17. [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; McCall, M.R.; Frei, B. Oxidation of LDL by myeloperoxidase and reactive nitrogen species: reaction pathways and antioxidant protection. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000, 20, 1716–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Kisugi, R. Mechanisms of LDL oxidation. Clin Chim Acta 2010, 411, 1875–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic N, Fernández, Landa, J, Santibañez A., Kura, B, Stajer V, Korovljev D, Ostojic, SM. The Effects of Hydrogen-Rich Water on Blood Lipid Profiles in Clinical Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2023;16:142. [CrossRef]

- Ge L, Yang M, Yang NN, Yin XX, Song WG. Molecular hydrogen: a preventive and therapeutic medical gas for various diseases. Oncotarget. 2017;8(60):102653-102673. [CrossRef]

- Christl, S.U.; Murgatroyd, P.R.; Gibson, G.R.; Cummings, J.H. Production, metabolism, and excretion of hydrogen in the large intestine. Gastroenterology 1992, 102 Pt 1, 1269–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki A, Ito M, Hamaguchi T, Mori H, Takeda Y, Baba R, Watanabe T, Kurokawa K, Asakawa S, Hirayama M, Ohno K. Quantification of hydrogen production by intestinal bacteria that are specifically dysregulated in Parkinson's disease. PLoS One. 2018, 13(12):e0208313. [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, T. Therapeutic Efficacy of Molecular Hydrogen: A New Mechanistic Insight. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25(9):946-955. [CrossRef]

- Dole, M.; Wilson, F.R.; Fife, W.P. Hyperbaric hydrogen therapy: A possible treatment for cancer. Science 1975, 190, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, I.; Ishikawa, M.; Takahashi, K.; Watanabe, M, Nishimaki, K, Yamagata, K, Katsura, K. I., Katayama Y, Asoh, S, Ohta S. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao A, Toyoda Y, Sharma P, Evans M, Guthrie N. Effectiveness of hydrogen rich water on antioxidant status of subjects with potential metabolic syndrome—an open label pilot study. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 2010; 46 (2): 140-149. [CrossRef]

- Kajiyama S, Hasegawa G, Asano M, Hosoda H, Fukui M, Nakamura N, Kitawaki J, Imai S, Nakano K, Ohta M, Adachi T, Obayashi H, Yoshikawa T. Supplementation of hydrogen-rich water improves lipid and glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance. Nutr Res 2008; 28 (3): 137-143. [CrossRef]

- Guihua, L.; Tongsu, N. Efficacy and safety of hydrogen inhalation therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with poor response to metformin. Advances in Clinical Medicine 2022, 12, 9605–9612. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Ji H, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Sun R, Li Y and Ni T. Effectiveness and safety of hydrogen inhalation as an adjunct treatment in Chinese type 2 diabetes patients: A retrospective, observational, double-arm, real-life clinical study. Front. Endocrinol. 2023;13:1114221. [CrossRef]

- Korovljev D, Trivic T, Drid P, Ostojic SM. Molecular hydrogen affects body composition, metabolic profiles, and mitochondrial function in middle-aged overweight women. Ir J Med Sci 2018; 187 (1): 85-89. [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Li, M.; Sang, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Yao, S.; Yu, Y.; Zong, C.; Xue, Y.; Qin, S. Hydrogen-rich water decrease serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and improves high density lipoprotein function in patients with potential metabolic syndrome. J Lipid Res 2013, 54, 1884–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song G, Lin Q, Zhao H, Liu M, Ye F, Sun Y, Yu Y, Guo S, Jiao P, Wu Y, Ding G, Xiao Q, Qin S. Hydrogen activates ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-dependent efflux ex vivo and improves high-density lipoprotein function in patients with hypercholesterolemia: A double-blinded, randomized, and placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100 (7): 2724-2733. [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Zhang, G.; Chen, W.; Yang, C.; Xue, Y.; Song, G.; Qin, S. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of hydrogen/oxygen inhalation for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2022, 26, 4113–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kura, B.; Szantova, M.; LeBaron, T.W.; Mojto, V.; Barancik, M.; Szeiffova Bacova, B.; Kalocayova, B.; Sykora, M.; Okruhlicova, L.; Tribulova, N.; et al. Biological Effects of Hydrogen Water on Subjects with NAFLD: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.B.; Nabavizadeh, F.; Fedacko, J.; Pella, D.; Vanova, N.; Jakabcin, P.; Fatima, G.; Horuichi, R.; Takahashi, T.; Mojto, V.; et al. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension via Indo-Mediterranean Foods, May Be Superior to DASH Diet Intervention. Nutrients 2023, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai K, Tamura T, Sano M, Uemura S, Fujisawa M, Katsumata Y, Endo J, Yoshizawa J, Homma K, Suzuki M, Kobayashi E, Sasaki J, Hakamata Y. Daily inhalation of hydrogen gas has a blood pressure-lowering effect in a rat model of hypertension. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 26;10(1):20173. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama M, et al. Novel haemodialysis (HD) treatment employing molecular hydrogen (H2)-enriched dialysis solution improves prognosis of chronic dialysis patients: A prospective observational study. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:254. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Jiang X, Xie Y, Jia X, Zhang J, Xue Y and Qin S. The effect of a low dose hydrogen-oxygen mixture inhalation in midlife/older adults with hypertension: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1025487. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Manaenko, A.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, W.W.; Ostrowki, R.P.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.H. Hydrogen gas reduced acute hyperglycemia-enhanced hemorrhagic transformation in a focal ischemia rat model. Neuroscience 2010, 169, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagatani, K.; Wada, K.; Takeuchi, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Uozumi, Y.; Otani, N.; Fujita, M.; Tachibana, S.; Nawashiro, H. Effect of hydrogen gas on the survival rate of mice following global cerebral ischemia. Shock (Augusta, Ga) 2012, 37, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaenko, A.; Lekic, T.; Ma, Q.; Ostrowski, R.P.; Zhang, J.H.; Tang, J. Hydrogen inhalation is neuroprotective and improves functional outcomes in mice after intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011, 111, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Ono H, Nishijima Y, Adachi N, et al. A basic study on molecular hydrogen (H2) inhalation in acute cerebral ischemia patients for safety check with physiological parameters and measurement of blood H2 level. Med Gas Res, 2 (2012), p. 21. [CrossRef]

- Ono H, Nishijima Y, Ohta S, Sakamoto M, Kinone K, Tohru Horikosi T, et al. Hydrogen Gas Inhalation Treatment in Acute Cerebral Infarction: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Study on Safety and Neuroprotection. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases,2017; 26:2587-94. [CrossRef]

- Yao W, Shen L, Ma Z et al. Efficacy and safety of hydrogen gas versus standard therapy in Chinese patients with cerebral infarction: A pilot study Trop. J Pharm Res 2022, 21, 671. [Google Scholar]

- Gvozdjáková A, Kucharská J, Kura B, Vančová O, Rausová Z, Sumbalová Z, Uličná O, Slezák J. A new insight into the molecular hydrogen effect on coenzyme Q and mitochondrial function of rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2020 Jan;98(1):29-34. [CrossRef]

- Kucharská J, Gvozdjáková A, Kura B, et al. Effect of molecular hydrogen on coenzyme Q in plasma, myocardial tissue and mitochondria of rats. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2018;8(5): 362‒364. [CrossRef]

- Sobue S, Inoue C, Hori F, Qiao S, Murate T, Ichihara M. Molecular hydrogen modulates gene expression via histone modification and induces the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017 Nov 4;493(1):318-324. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; He, B.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X. Anti-inflammatory effect of hydrogen-rich saline in a rat model of regional myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Int J Cardiol 2011, 148, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turer A.T., Hill J.A. Pathogenesis of Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury and Rationale for Therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010;37:761–771. [CrossRef]

- Xia Y., Zweier J.L. Substrate control of free radical generation from xanthine oxidase in the postischemic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:18797–18803. [CrossRef]

- Zorov D.B., Filburn C.R., Klotz L.-O., Zweier J.L., Sollott S.J. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-induced ROS Release: A New Phenomenon Accompanying Induction of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition in Cardiac Myocytes. J. Exp. Med. Bull. 2000;192:1001–1014. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y., Tan S., Xu J., Wang T. Hydrogen Therapy in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases: From Bench to Bedside. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;47:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ichihara, G.; Katsumata, Y.; Moriyama, H.; Kitakata, H.; Hirai, A.; Momoi, M.; Ko, S.; Shinya, Y.; Kinouchi, K.; Kobayashi, E.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of hydrogen after ingesting a hydrogen-rich solution: A study in pigs. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E. , Kloner R.A. Myocardial reperfusion: A double-edged sword? J. Clin. Invest. 1985, 76, 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausenloy, D.J.; Yellon, D.M. Preconditioning and postconditioning: United at reperfusion. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 116, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. L, Weyrich A.S., Lefer D.J., Lefer A.M. Diminished basal nitric oxide release after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion promotes neutrophil adherence to coronary endothelium. Circ. Res. 1993, 72, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Xie, K. Hydrogen-rich saline alleviates inflammation and apoptosis in myocardial I/R injury via PINK-mediated autophagy. Int J Mol Med. 2019, 44, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumata Y, Fumiya Sano F, Takayuki Abe T, et al. The Effects of Hydrogen Gas Inhalation on Adverse Left Ventricular Remodeling After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction― First Pilot Study in Humans. Circulation Journal 2017, 81, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin YT, Shi QQ, Zhang L, Yue CP, He ZJ, Li XX, et al. Hydrogen-rich water ameliorates neuropathological impairments in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease through reducing neuroinflammation and modulating intestinal microbiota. Neural Regeneration Research 2022, 17, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan X, Shen F, Dong WL, Yang Y, Chen G. The role of hydrogen in Alzheimer's disease. Med Gas Res. 2019 Jan 9;8(4):176-180. [CrossRef]

- Wen D, Zhao P, Hui R, et al. Hydrogen-rich saline attenuates anxiety-like behaviors in morphine-withdrawnmice. Neuropharmacology 2017, 118, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshii Y, Inoue T, Uemura Y, et al. Complexity of stomach-brain interaction induced by molecular hydrogen in Parkinson’s disease model mice. Neurochem Res. 2017, 42, 2658–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, D.; Todorovic, N.; Korovljev, D.; Stajer, V.; Ostojic, J.; Purac, J.; Kojic, D.; Vukasinovic, E.; Djordjievski, S.; Sopic, M.; Guzonjic, A.; Ninic, A.; Erceg, S.; Ostojic, S.M. The effects of 6-month hydrogen-rich water intake on molecular and phenotypic biomarkers of aging in older adults aged 70 years and over: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Experimental Gerontology 2021, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo JD, Li L, Shi YM, Wang HD, Hou SX. Hydrogen water consumption prevents osteopenia in ovariectomized rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2013 Mar;168(6):1412-20. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Shuang F, Chen DM, Zhou RB. Treatment of hydrogen molecule abates oxidative stress and alleviates bone loss induced by modeled microgravity in rats. Osteoporos Int. 2013 Mar;24(3):969-78. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ji, G.; Pan, R.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, P. Protective effect of hydrogen-rich water on liver function of colorectal cancer patients treated with mFOLFOX6 chemotherapy. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017, 7, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Noor, MNZ., Alauddin, AS., Wong, YH., Looi, CY., Wong, EH., Madhavan, P., Yeong, CHA Systematic Review of Molecular Hydrogen Therapy in Cancer management Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2023; 24(1): 37-47. ,. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, S.I.; Aoki, Y.; Li, X.K.; Ichimaru, N.; Takahara, S.; Takefuji, Y. Protective effects of hydrogen gas inhalation on radiation-induced bone marrow damage in cancer patients: a retrospective observational study. Med Gas Res. 2021, 11, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dole, M.; Wilson, F.R.; Fife, W.P. Hyperbaric hydrogen therapy: a possible treatment for cancer. Science 1975, 190, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runtuwene, J.; Amitani, H.; Amitani, M.; Asakawa, A.; Cheng, K.C.; Inui, A. Hydrogen-water enhances 5-fluorouracil-induced inhibition of colon cancer. Peer J. 2015, 3, e859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharzadeh, F.; Tarnava, A.; Mostafapour, A.; Khazaei, M.; LeBaron, T.W. Hydrogen-rich water exerts anti-tumor effects comparable to 5-fluorouracil in a colorectal cancer xenograft model. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2022, 14, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa T, Ito M, Hasegawa et al. Molecular Hydrogen Enhances Proliferation of Cancer Cells That Exhibit Potent Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Li Z, Mao L, Zhao M, Yang B, Tao X, Li Y, Yin G. Hydrogen: A Novel Treatment Strategy in Kidney Disease. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2022 Jan 12;8(2):126-136. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y, Li CF, Ping NN, Sun YY, Wang Z, Zhao GX, et al. Hydrogen-rich water alleviates cyclosporine A-induced nephrotoxicity via the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2020, 34, e22467. [Google Scholar]

- Xing Z, Pan W, Zhang J, Xu X, Zhang X, He X, et al. Hydrogen rich water attenuates renal injury and fibrosis by regulation transforming growth factor-β induced Sirt1. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017, 40, 610–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Zhang H, Hu J, Gu Y, Shen Z, Xu L, et al. Hydrogen-rich saline alleviates kidney fibrosis following AKI and retains Klotho expression. Front Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li J, Hong Z, Liu H, Zhou J, Cui L, Yuan S, et al. Hydrogen-rich saline promotes the recovery of renal function after ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats via anti-apoptosis and anti-inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, He X, Liu J, Qin J, Ye J, Fan M. Protective effects of hydrogen-rich saline against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by increased expression of heme oxygenase-1 in aged rats. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019, 12, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Hayashi T, Inamoto T, Kato R, Ibuki N, Takahara K, et al. Dual gas treatment with hydrogen and carbon monoxide attenuates oxidative stress and protects from renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplant Proc. 2018, 50, 250–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu H, Ding J, Liu W, Peng Z, Chen W, Sun X, et al. UPLC/MS-based metabolomics investigation of the protective effect of hydrogen gas inhalation on mice with calcium oxalate-induced renal injury. Biol Pharm Bull. 2018, 41, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng Z, Zheng F. Immune cells and inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 1841690. [Google Scholar]

- Trionfetti F, Marchant V, González-Mateo GT et al. Novel Aspects of the Immune Response Involved in the Peritoneal Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients under Dialysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023; 24(6):5763. [CrossRef]

- Fischer BM, Voynow JA, Ghio AJ. COPD: balancing oxidants and antioxidants. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:261-76. [CrossRef]

- Wang ST, Bao C, He Y, Tian X, Yang Y, Zhang T, Xu KF. Hydrogen gas (XEN) inhalation ameliorates airway inflammation in asthma and COPD patients. QJM. 2020 Dec 1;113(12):870-875. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y. , Sato, T., Sugimoto, M., Baskoro, H., Karasutani, K., Mitsui, A., Nurwidya, F., Arano, N., Kodama, Y., Hirano, S.I. and Ishigami, A.. Hydrogen-rich pure water prevents cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema in SMP30 knockout mice. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2017, 492, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh RB, Halabi G, Fatima G, Rai RH, Tarnava AT, LeBaron TW. Molecular hydrogen as an adjuvant therapy may be associated with increased oxygen saturation and improved exercise tolerance in a COVID-19 patient. Clin Case Reports 9: e05039. | 1 of 6. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, ZG., Sun, WZ., Hu, JY. et al. Hydrogen/oxygen therapy for the treatment of an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group controlled trial. Respir Res 2021;22, 149. [CrossRef]

- Kohama K, Yamashita H, Aoyama-Ishikawa M, Takahashi T, Billiar TR, Nishimura T, Kotani J, Nakao A. Hydrogen inhalation protects against acute lung injury induced by hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. Surgery. 2015;158:399–407. [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Yue R, Luo X, Liu R, Huang X. Hydrogen: A Potential New Adjuvant Therapy for COVID-19 Patients. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:543718. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Peng J, Hui J, Hou D, Li W, Yang J. Hydrogen therapy as an effective and novel adjuvant treatment against COVID-19. QJM. 2021;114(1):74-5. [CrossRef]

- Deryugina, A.V.; Danilova, D.A.; Pichugin, V.V.; Brichkin, Y.D. The Effect of Molecular Hydrogen on Functional States of Erythrocytes in Rats with Simulated Chronic Heart Failure. Life 2023, 13, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. Saturated hydrogen saline attenuates endotoxin-induced lung dysfunction. J Surg Res. 2015, 198, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh RB, Gupta AK, Fatima G, Fedacko J et al. Can molecular hydrogen therapy enhance oxygen saturation among patients with chronic lung disease. Presented and abstracted in the First conference of the European Academy of Molecular Hydrogen Research in Biomedicine. Smolenice Castle, Slovakia, (Abstract Page 69) Oct 17-20,2022.

- Ishibashi, T.; Kawamoto, K.; Matsuno, K.; Ishihara, G.; Baba, T.; Komori, N. Peripheral endothelial function can be improved by daily consumption of water containing over 7 ppm of dissolved hydrogen: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0233484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q. , Liu, B., Xue, J., Zhao, M., Zhang, X., Wang, M., Zhang, M., Xue, Y., Qin, S. (2020). Effects of drinking hydrogen-rich water in men at risk of peripheral arterial disease: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. [CrossRef]

- Asada, R.; Tazawa, K.; Sato, S.; Miwa, N. Effects of hydrogen-rich water prepared by alternating-current-electrolysis on antioxidant activity, DNA oxidative injuries, and diabetes-related markers. Medical Gas Research 2020, 10, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura N, Ichimiya H, Iuchi K, Ohta S. Molecular hydrogen stimulates the gene expression of transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α to enhance fatty acid metabolism. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2016 Apr 28;2:16008. eCollection 2016. [CrossRef]

- Nagatani K, Nawashiro H, Takeuchi S, et al. Safety of intravenous administration of hydrogen-enriched fluid in patients with acute cerebral ischemia: initial clinical studies. Med Gas Res. 2013, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, D.; Stajer, V.; Ostojic, S.M. Hydrogen vs. caffeine for improved alertness in sleep-deprived humans. Neurophysiology 2020, 52, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, W. T. , Kharman, J., McCullough, L. Michael. (2021). An H2-infused, nitric oxide-producing functional beverage as a neuroprotective agent for TBIs and concussions. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience 2021, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, S.; Kumagai, K.; Toyooka, T.; Otani, N.; Wada, K.; Mori, K. Intravenous Hydrogen Therapy With Intracisternal Magnesium Sulfate Infusion in Severe Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Stroke 2021, 52, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano SI, Aoki Y, Li XK, Ichimaru N, Takahara S, Takefuji Y. Protective effects of hydrogen gas inhalation on radiation-induced bone marrow damage in cancer patients: a retrospective observational study. Med Gas Res. 2021 Jul-Sep;11(3):104-109. [CrossRef]

- Chen JB., Kong, XF., Qian, W, Mu, F., Lu, TY., Lu, YY., & Xu, KC. Two weeks of hydrogen inhalation can significantly reverse adaptive and innate immune system senescence patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A self-controlled study. Medical Gas Research, 2020;10(4), 149–154. 127.Akagi J, Baba H. Hydrogen gas activates coenzyme Q10 to restore exhausted CD8+ T cells, especially PD-1+Tim3+terminal CD8+ T cells, leading to better nivolumab outcomes in patients with lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2020 Nov;20(5):258. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.12121.

- Korovljev, D.; Trivic, T.; Stajer, V.; Drid, P.; Sato, B.; Ostojic, S.M. Short-term H2 inhalation improves cognitive function in older women: A pilot study. International Journal of Gerontology 2019, 14, 149–150. [Google Scholar]

- Lv X, Lu Y, Ding G, et al. Hydrogen Intake Relieves Alcohol Consumption and Hangover Symptoms in Healthy Adults: a Randomized and Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study [published online ahead of print, 2022 Sep 16]. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;nqac261. [CrossRef]

- Okada M, Ogawa H, Takagi T, Nishihara E, Yoshida T, Hyodo J, Shinomori Y, Honda N, Fujiwara T, Teraoka M, Yamada H, Hirano S-i and Hato N. A double-blinded, randomized controlled clinical trial of hydrogen inhalation therapy for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Front. Neurosci. 2022;16:1024634. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Suzuki, M.; Hayashida, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yoshizawa, J.; Shibusawa, T.; Sano, M.; Hori, S.; Sasaki, J. Hydrogen gas inhalation alleviates oxidative stress in patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 2020, 67, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Kiuchi, M.; Higashimura, Y.; Naito, Y.; Koyama, K. The effects of ingestion of hydrogen-dissolved alkaline electrolyzed water on stool consistency and gut microbiota: a double-blind randomized trial. Medical Gas Research 2021, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilova DA, Brichkin YD, Medvedev AP, Pichugin VV, Fedorov SA, Taranov EV, Nazarov EI, Ryazanov MV, Bolshukhin GV, Deryugina AV. Application of Molecular Hydrogen in Heart Surgery under Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Sovrem Tekhnologii Med. 2021;13(1):71-75. [CrossRef]

- Increased Sympathetic Cardiac Activity in Healthy Females, Hydrogen Water.

- Botek, M.; Sládečková; B; Krejčí; J; Pluháček, F. ; Najmanová; E Acute hydrogen-rich water ingestion stimulates cardiac autonomic activity in healthy females. Acta Gymnica 2021, 51, e2021–009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yan, M. Clinical assessment of hydrogen-rich water and oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release tablets in the treatment of malignant neuropathic pain. Journal of Chinese Physician 2016, 18, 1329–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Kubota, M.; Kawashima, M.; Inoue, S.; Imada, T.; Nakamura, S.; Kubota, S.; Watanabe, M.; Takemura, R.; Tsubota, K. Randomized, crossover clinical efficacy trial in humans and mice on tear secretion promotion and lacrimal gland protection by molecular hydrogen. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iketani, M.; Sekimoto, K.; Igarashi, T.; Takahashi, M.; Komatsu, M.; Sakane, I.; Takahashi, H.; Kawaguchi, H.; Ohtani-Kaneko, R.; Ohsawa, I. Administration of hydrogen-rich water prevents vascular aging of the aorta in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Sci Rep. 2018 Nov 14;8(1):16822. [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.M.; Kang, Y.N.; Choi, I.B.; Gu, Y.; Kawamura, T.; Toyoda, Y.; Nakao, A. Effects of drinking hydrogen-rich water on the quality of life of patients treated with radiotherapy for liver tumors. Med Gas Res. 2011, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Hydrogen rich water (n-30) | Placebo (n=30) | ||

| Data, mg/dl | Baseline | After 24 weeks | Baseline | After 24 weeks |

| Cholesterol | 187.7 ± 32.4 | 169.2 ± 26.1*** | 184.3 ± 37.4 | 184.4 ± 38.6 |

| LDL-Cholesterol | 109.0 ± 34.4 | 102.5 ± 28.0 | 105.5 ± 42.0 | 106.0 ± 43.3 |

| HDL cholesterol | 41.7 ± 4.2 | 40.4 ± 1.8 | 41.8 ± 2.3 | 42.3 ± 2.4 |

| VLDL cholesterol | 37.3 ± 17.9 | 28.0 ± 11.3** | 36.8 ± 20.6 | 37.3 ± 20.5 |

| Triglycerides | 189.8 ± 93.3 | 142.4 ± 65.0** | 184.4 ± 102.8 | 185.6 ± 101.3 |

| C-reactive proteins | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1* | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 |

| Hydrogen rich water(n=30) | Placebo (n=30) | |||

| Data, mg/dl | Baseline | After 24 weeks | Baseline | After 24 weeks |

| Fasting blood glucose | 121.5 ± 61.0 | 103.1 ± 33.0* | 123.9 ± 43.4 | 126.4 ± 42.3 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 5.1 ± 0.2*** | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 6.1 ± 1.2 |

| TNF-α | 4.8 ± 1.2 | 3.9 ± 0.6*** | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 4.8 ± 1.3 |

| IL-6 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.2** | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.7±0.6 |

| TBARS | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3* | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| Melondialdehyde | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2*** | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| Diene conjugates | 27.8 ± 1.0 | 26.7 ± 0.5*** | 28.3 ± 0.8 | 28.3 ± 0.8 |

| Vitamin E | 23.0 ± 2.3 | 26.8 ± 1.9*** | 23.0 ± 1.5 | 23.1 ± 1.1 |

| Vitamin C | 20.7 ± 2.5 | 24.2 ± 1.8*** | 20.7 ± 2.5 | 20.8 ± 2.4 |

| Nitrite | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 0.68 ± 0.06*** | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.65 ± 0.03 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme | 85.2 ± 7.8 | 80.7 ± 5.8*** | 84.5 ± 8.8 | 83.8 ± 8.7 |

| Alterations due I/R injury | Mechanisms |

| Ion flux | Accumulation of intracellular calcium, a2+-induced “stone-heart”, increased Na influx, Abnormal K flux. Drop in pH followed by normalization upon reperfusion. |

| Loss of myocardial membrane potential. | Opening of myocardial permeability transition pore (mPTP) |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) | Substrate-level induction of xanthine oxidase resulting in more ROS. Impaired mitochondrial function, worsen with Q10 deficiency, Neutrophil infiltration, ROS induced ROS chain. |

| Dysregulation of Nitric Oxide (NO) metaboilism. | Loss of NO vasodilation, Production of Peroxynitrite, Abnormal S-nitrosation, |

| Apoptosis | JNK Pathway, ceramide generation, cytoplasm acidification, caspase activation. |

| Autophagic cell death. | Excessive AMPK activation, Excess of induction of HIF-1α |

| Endothelial dysfunction | Cytokine,myokine, chemokine signaling. Expression of cellular adhesion markers, Impaired vasodilation. |

| Platelet aggregationAuto-immune activation | Innate immunity; complement activation, induction of TLRNeutrophil accumulation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).