Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

29 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Main Contributions

- We introduce a new regularization method to apply flexible interaction of features on autoencoder. Unlike current autoencoder-based regularization methods which just deactivate the node of low activation probability, two guiding layers of our PGSAE method are complementarily trained to reduce the noise using the results of reconstruction.

- We propose a method based on Wasserstein distance. Wasserstein limits the relative distance of two guiding layers to improve the regularization performance. This offers a highly flexible regularization because it tunes the distributions of two guiding layers as a proper similarity and thus reduces information loss. Therefore, it can be a supplementary solution to the autoencoder-based feature learning method.

- We design a parallel network form. The parallel guiding process is quite a new concept. It can be extended to many neural network fields, where two different networks can be reasonably fused in terms of the probabilistic distribution.

- We develop the partially focused learning method by guiding the layer. It is the basic study to be applied to any other kind of neural network field and extended to be used in complex structures.

- The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the related work, including the basic theory and advanced theory of the autoencoder which is related to the proposed method. Section 3 describes the details of the proposed PGSAE method and shows its framework. Section 4 illustrates the experiment environment, evaluation metrics, information on datasets, and experimental results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Background and Related works

2.1. Sparse Autoencoder (SAE)

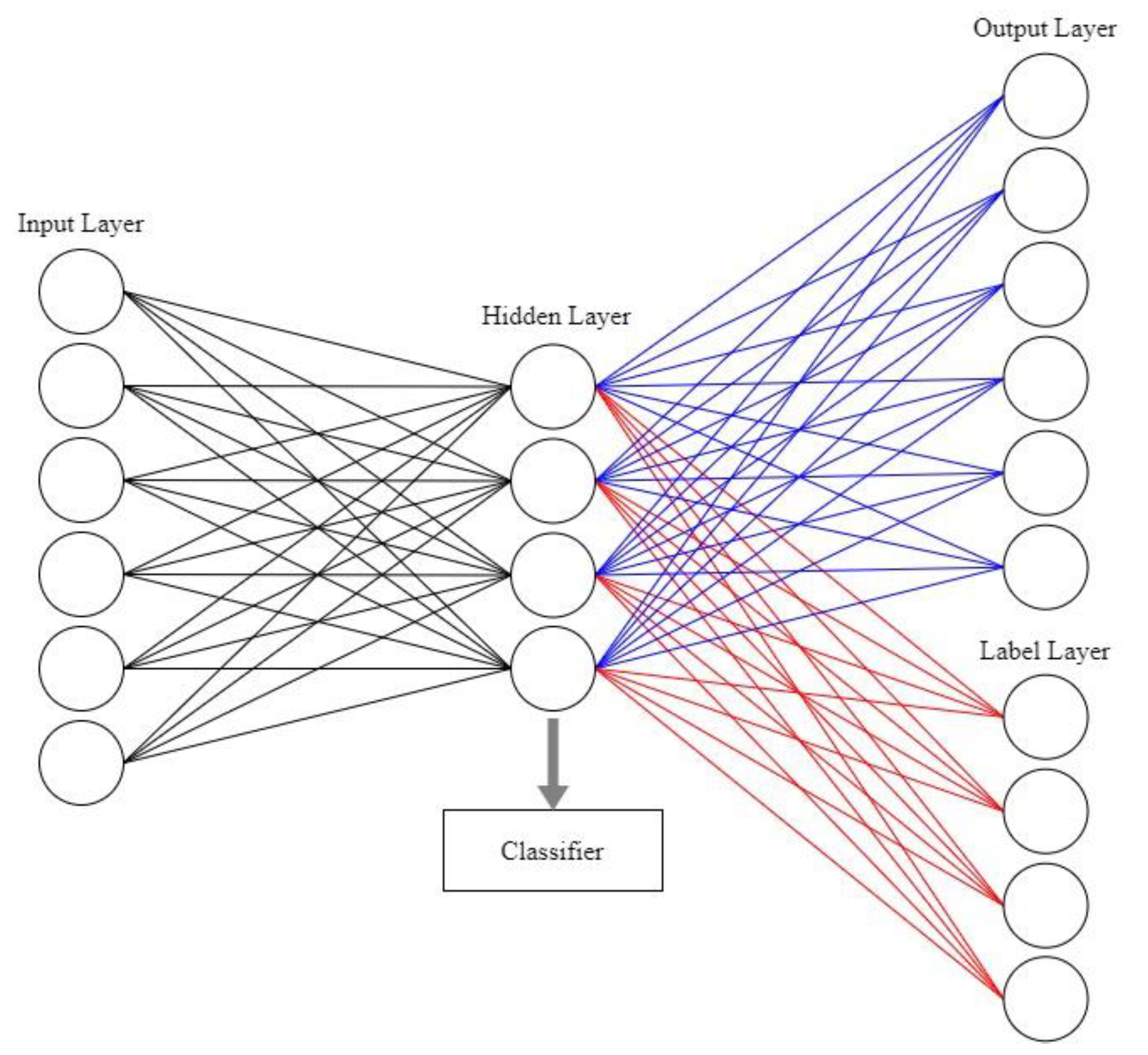

2.2. Label and sparse regularization autoencoder (LSRAE)

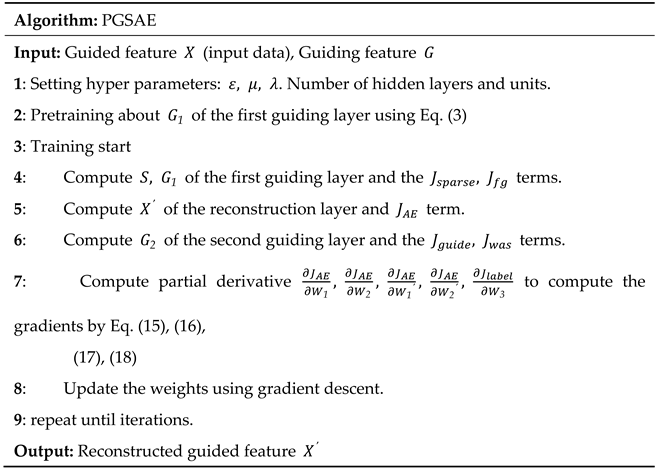

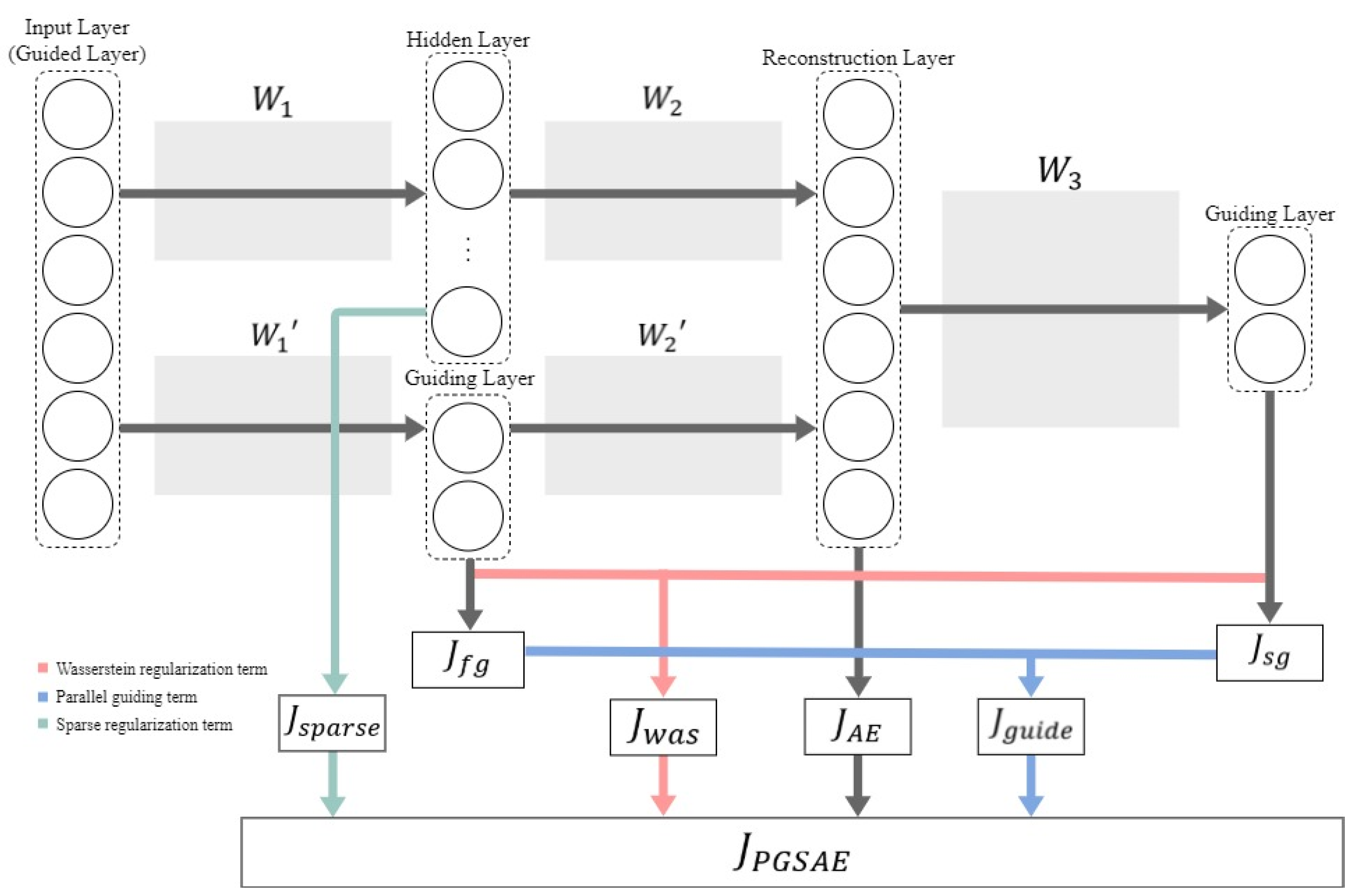

3. Parallel guiding sparse autoencoder

|

4. Experimental result of PGSAE

4.1. Datasets and experimental setups

4.2. Authentication of main innovation

4.3. Comparison of the benchmark datasets

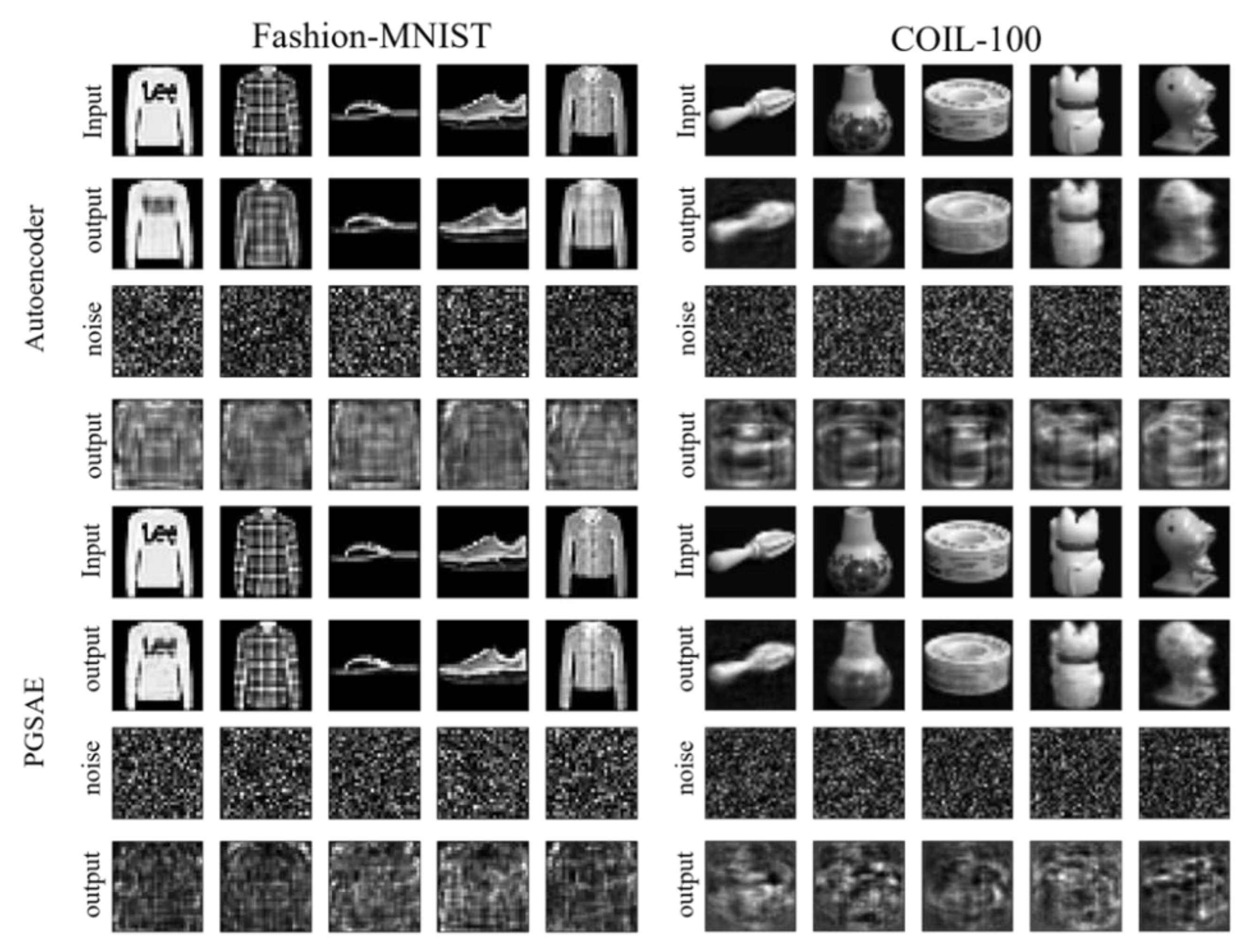

4.4. Prevention of transforming irrelevant data as like training data

4.5. Effect of the coefficients and classifiers

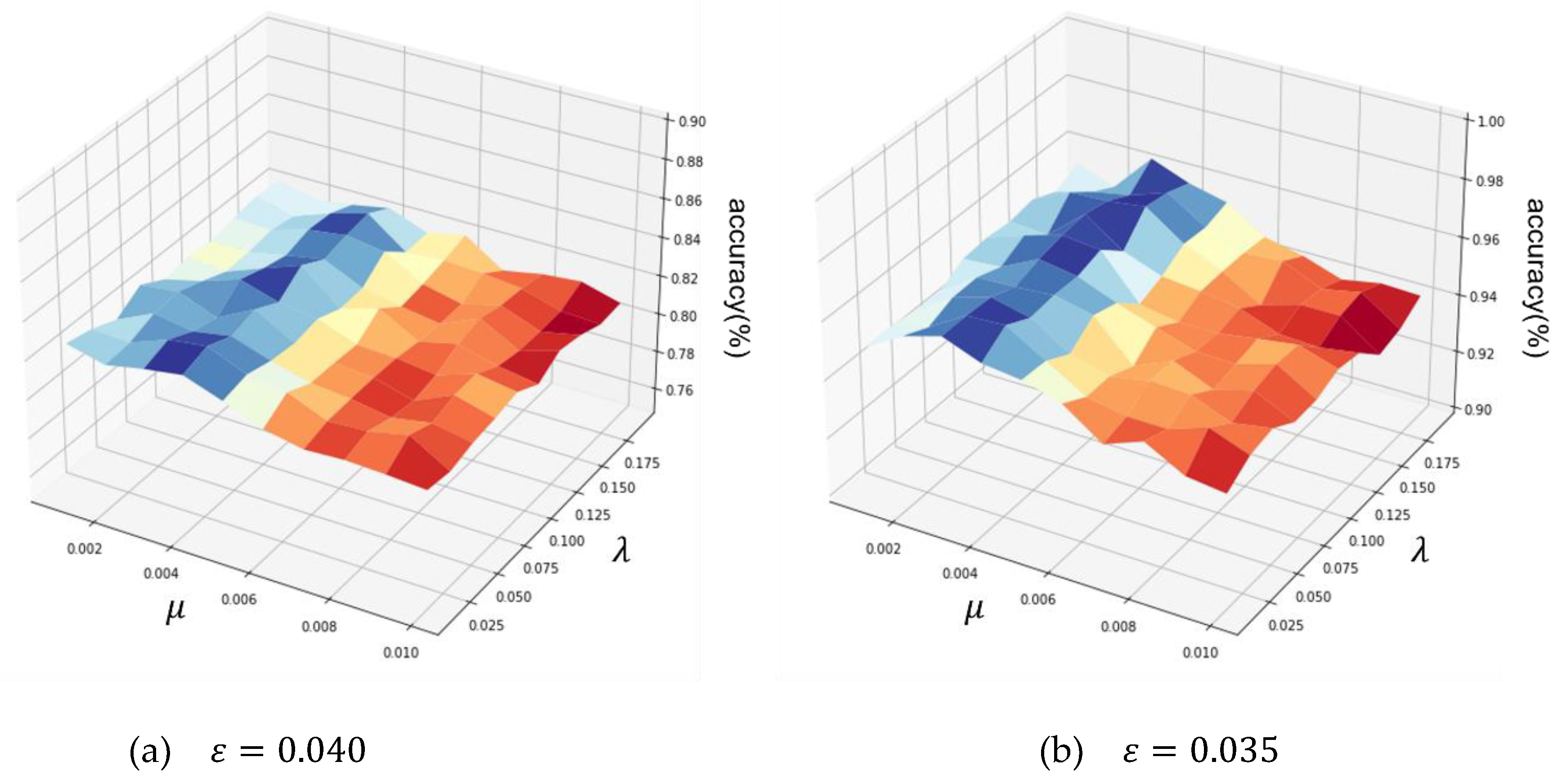

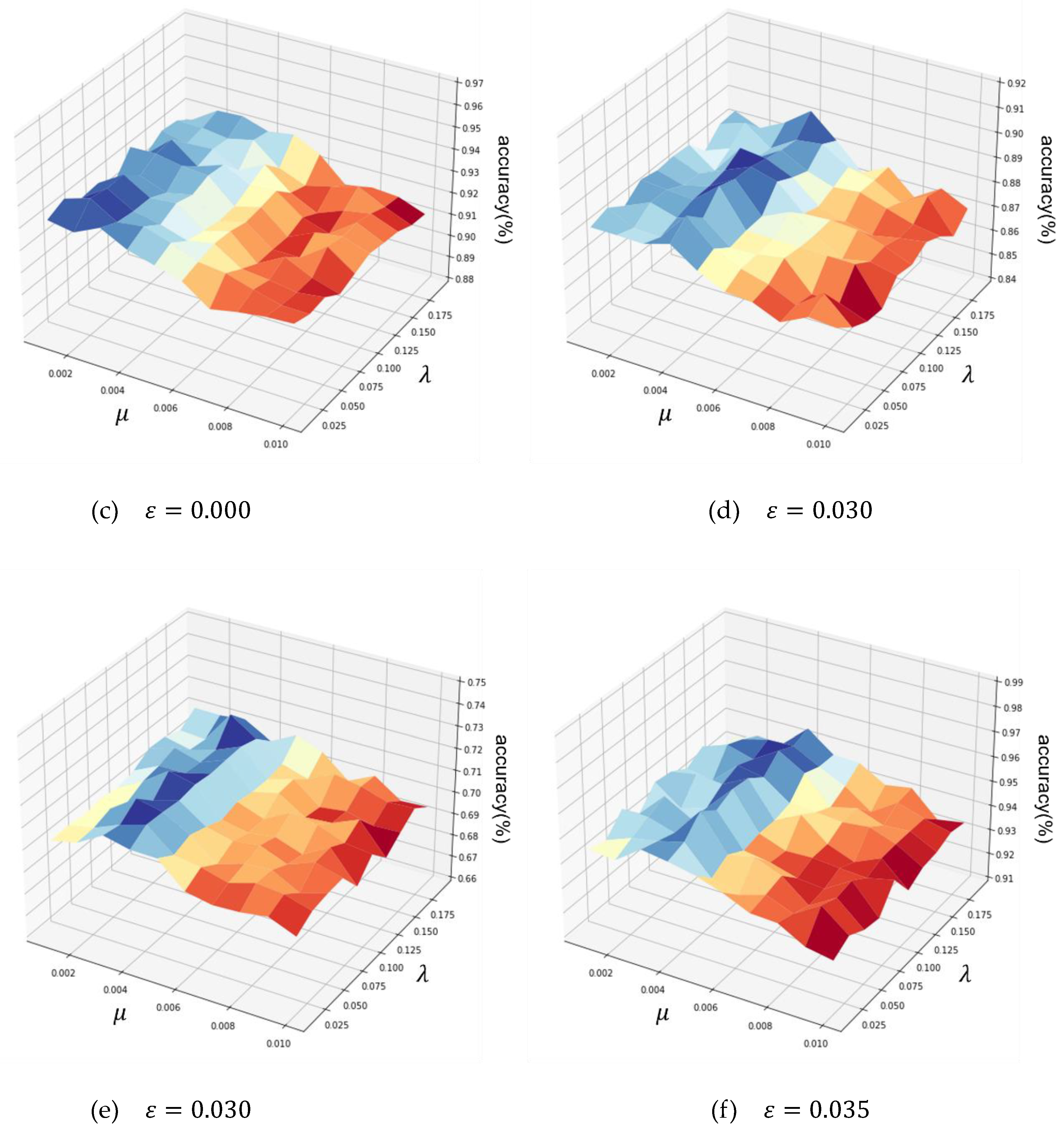

4.5.1. Coefficients Optimization on the six datasets

4.5.2. Effects of classifier

5. Conclusion and future work

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Storcheus, A. Rostamizadeh, S. Kumar, A survey of modern questions and challenges in feature extraction, Feature Extraction: Modern Questions and Challenges, (PMLR2015), pp. 1-18.

- Wang, Y.; Yao, H.; Zhao, S. Auto-encoder based dimensionality reduction. Neurocomputing 2016, 184, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, C.-Y.; Cheng, W.-C.; Liou, J.-W.; Liou, D.-R. Autoencoder for words. Neurocomputing 2014, 139, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luong, M.-T.; Jurafsky, D. A hierarchical neural autoencoder for paragraphs and documents. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.01057, 2015.

- Tschannen, M.; Bachem, O.; Lucic, M. Recent advances in autoencoder-based representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.05069, 2018.

- Li, J.; Cheng, K.; Wang, S.; Morstatter, F.; Trevino, R.P.; Tang, J.; Liu, H. Feature selection: A data perspective. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2017, 50, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, A.; Brkić, K.; Bogunović, N. A review of feature selection methods with applications, 2015 38th international convention on information and communication technology, electronics and microelectronics (MIPRO), (Ieee2015), pp. 1200-1205.

- Chandrashekar, G.; Sahin, F. A survey on feature selection methods. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2014, 40, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Osia, S.A.; Taheri, A.; Shamsabadi, A.S.; Katevas, K.; Haddadi, H.; Rabiee, H.R. Deep private-feature extraction. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2018, 32, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghojogh, B.; Samad, M.N.; Mashhadi, S.A.; Kapoor, T.; Ali, W.; Karray, F.; Crowley, M. Feature selection and feature extraction in pattern analysis: A literature review. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1905.02845. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M.; Fung, G.; Rosales, R. Fast optimization methods for l1 regularization: A comparative study and two new approaches, European Conference on Machine Learning, (Springer2007), pp. 286-297.

- Van Laarhoven, T. L2 regularization versus batch and weight normalization. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1706.05350. [Google Scholar]

- Azhagusundari, B.; Thanamani, A.S. Feature selection based on information gain. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) 2013, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, F.B.; Satorra, A. Principles and practice of scaled difference chi-square testing. Structural equation modeling: A multidisciplinary journal 2012, 19, 372–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, S.; Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.J.; Müller, K.-R.; Scholz, M.; Rätsch, G. Kernel PCA and De-noising in feature spaces, NIPS1998), pp. 536-542.

- Ding, C.; Zhou, D.; He, X.; Zha, H. R 1-pca: rotational invariant l 1-norm principal component analysis for robust subspace factorization, Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning2006), pp. 281-288.

- Andrew, G.; Arora, R.; Bilmes, J.; Livescu, K. Deep canonical correlation analysis, International conference on machine learning, (PMLR2013), pp. 1247-1255.

- Yu, H.; Yang, J. A direct LDA algorithm for high-dimensional data—with application to face recognition. Pattern recognition 2001, 34, 2067–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.M.; Kak, A.C. Pca versus lda. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2001, 23, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Han, J.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, B. Learning compact and discriminative stacked autoencoder for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 4823–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, P.; Huang, S.; Fan, P. A sparse stacked denoising autoencoder with optimized transfer learning applied to the fault diagnosis of rolling bearings. Measurement 2019, 146, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, M.G.; Torquato, M.F.; Fernandes, M.A. Deep neural network hardware implementation based on stacked sparse autoencoder. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 40674–40694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Lei, J.; Yin, Y.; Cao, K.; Li, Y.; Chang, C.-I. Discriminative feature learning with distance constrained stacked sparse autoencoder for hyperspectral target detection. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2019, 16, 1462–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, X. A semi-supervised deep learning method based on stacked sparse auto-encoder for cancer prediction using RNA-seq data. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2018, 166, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, A.; Vatsa, M.; Singh, R. A. Majumdar, Group sparse autoencoder. Image and Vision Computing 2017, 60, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Song, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, F. A semi-supervised auto-encoder using label and sparse regularizations for classification. Applied Soft Computing 2019, 77, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Luo, D.; Henao, R.; Shah, S.; Carin, L. Learning autoencoders with relational regularization, International Conference on Machine Learning, (PMLR2020), pp. 1 0576–10586.

- Vayer, T.; Chapel, L.; Flamary, R.; Tavenard, R.; Courty, N. Fused Gromov-Wasserstein distance for structured objects. Algorithms 2020, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, R. Stacked denoising autoencoder and dropout together to prevent overfitting in deep neural network, 2015 8th international congress on image and signal processing (CISP), (IEEE2015), pp. 697-701.

- Goldberger, J.; Gordon, S.; Greenspan, H. An Efficient Image Similarity Measure Based on Approximations of KL-Divergence Between Two Gaussian Mixtures, ICCV2003), pp. 487-493.

- Huang, G.-B.; Zhu, Q.-Y.; Siew, C.-K. Extreme learning machine: a new learning scheme of feedforward neural networks, 2004 IEEE international joint conference on neural networks (IEEE Cat. No. 04CH37541), (Ieee2004), pp. 985-990.

- Steck, H. Autoencoders that don't overfit towards the Identity. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 19598–19608. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, M.; Rothlauf, F. Harmless Overfitting: Using Denoising Autoencoders in Estimation of Distribution Algorithms. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 78:71–78:31. [Google Scholar]

- Kunin, D.; Bloom, J.; Goeva, A.; Seed, C. Loss landscapes of regularized linear autoencoders, International Conference on Machine Learning, (PMLR2019), pp. 3560-3569.

- Pretorius, A.; Kroon, S.; Kamper, H. Learning dynamics of linear denoising autoencoders, International Conference on Machine Learning, (PMLR2018), pp. 4141-4150.

- Bunte, K.; Haase, S.; Biehl, M.; Villmann, T. Stochastic neighbor embedding (SNE) for dimension reduction and visualization using arbitrary divergences. Neurocomputing 2012, 90, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction, (2020).

- Wang, H.; van Stein, B.; Emmerich, M.; Back, T. A new acquisition function for Bayesian optimization based on the moment-generating function, 2017 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), (IEEE2017), pp. 507-512.

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical bayesian optimization of machine learning algorithms. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Audet, C.; Denni, J.; Moore, D.; Booker, A.; Frank, P. A surrogate-model-based method for constrained optimization, 8th symposium on multidisciplinary analysis and optimization2000), pp. 4891.

- Lin, W.; Wu, Z.; Lin, L.; Wen, A.; Li, J. An ensemble random forest algorithm for insurance big data analysis. Ieee access 2017, 5, 16568–16575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | # Classes | # Features | # Training | # Testing | # Dimensionality after feature extraction | |

| Low dimension | Heart | 2 | 13 | 240 | 63 | 9 |

| Wine | 2 | 12 | 4873 | 1624 | 8 | |

| Medium dimension | USPS | 10 | 256 | 7291 | 2007 | 180 |

| Fashion-MNIST | 10 | 784 | 60000 | 10000 | 549 | |

| High dimension | Yale | 15 | 1024 | 130 | 35 | 717 |

| COIL-100 | 100 | 1024 | 1080 | 360 | 717 | |

| Dataset | # Guiding units of PGSAE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | 64 – 32 – 64 | 0.040 | 0.119 | 0.004 |

| Wine | 64 – 32 – 64 | 0.035 | 0.166 | 0.003 |

| USPS | 256 – 128 – 256 | 0 | 0.025 | 0.001 |

| Fashion-MNIST | 256 – 128 – 256 | 0.030 | 0.115 | 0.003 |

| Yale | 512 – 256 – 512 | 0.030 | 0.171 | 0.002 |

| COIL-100 | 512 – 256 – 512 | 0.035 | 0.172 | 0.003 |

| Dataset | RF (%) | DF (%) | DF & WR (%) | DF & WR & SR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | 82.47 2.1 | 81.24 1.3 | 82.44 1.8 | 82.642.0 |

| Wine | 96.84 0.5 | 94.62 2.0 | 96.12 0.6 | 96.25 1.1 |

| USPS | 94.92 3.4 | 93.15 1.6 | 93.50 2.4 | 93.24 2.3 |

| Fashion-MNIST | 90.60 0.4 | 86.76 2.3 | 88.46 2.1 | 88.87 1.8 |

| Yale | 74.56 2.1 | 70.51 5.7 | 71.08 4.2 | 71.35 5.5 |

| COIL-100 | 96.19 0.2 | 93.87 1.1 | 94.56 1.2 | 95.33 0.5 |

| Dataset | RF (%) |

Kernel PCA (%) |

LDA (%) |

SAE (%) |

SSAE (%) |

UMAP (%) |

t-SNE (%) |

PGSAE (%) |

Hybrid PGSAE (%) |

| Heart | 82.47 2.1 |

81.82 1.1 |

76.86 4.5 |

82.23 2.8 |

81.82 2.7 |

74.38 5.2 |

60.33 9.2 |

82.64 2.0 |

83.22 1.7 |

| Wine | 96.84 0.5 |

96.00 1.2 |

93.15 1.4 |

95.98 1.5 |

96.87 1.1 |

95.54 2.2 |

95.52 2.9 |

96.25 1.1 |

97.93 0.8 |

| USPS | 94.92 3.4 |

91.46 5.6 |

92.78 5.7 |

93.47 3.9 |

93.23 4.5 |

89.23 9.9 |

86.36 8.4 |

93.50 2.4 |

95.37 3.1 |

| Fashion-MNIST | 90.60 0.4 |

87.07 3.5 |

87.27 3.2 |

87.98 2.7 |

88.65 1.8 |

81.28 6.4 |

81.38 4.7 |

88.87 1.8 |

91.08 1.0 |

| Yale | 74.56 2.1 |

71.48 6.8 |

68.26 3.6 |

67.44 7.4 |

70.78 4.1 |

69.33 5.5 |

61.45 8.5 |

71.35 5.5 |

76.58 4.2 |

| COIL-100 | 96.19 0.2 |

94.55 1.3 |

92.95 1.5 |

95.01 0.9 |

95.12 1.1 |

90.03 4.6 |

89.85 4.2 |

95.33 0.5 |

96.76 0.8 |

| Dataset | Basic AE (%) |

SAE (%) |

SSAE (%) |

PGSAE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | 0.3521 | 0.3213 | 0.3494 | 0.3132 |

| Wine | 0.4560 | 0.4651 | 0.4476 | 0.4242 |

| USPS | 0.1757 | 0.1634 | 0.1654 | 0.1537 |

| Fashion-MNIST | 0.2463 | 0.2578 | 0.2563 | 0.2487 |

| Yale | 0.8754 | 0.8743 | 0.8864 | 0.8435 |

| COIL-100 | 0.4749 | 0.4836 | 0.4798 | 0.4803 |

| Heart | Wine | USPS | Fashion-MNIST | Yale | COIL-100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM (%) | 82.64 2.0 | 96.25±1.1 | 93.50±2.4 | 88.87±1.8 | 71.35±5.5 | 95.33±0.5 |

| KNN (%) | 77.486.3 | 92.783.2 | 89.754.7 | 83.792.9 | 69.954.1 | 86.464.6 |

| Random Forest (%) | 81.721.8 | 94.552.1 | 90.562.2 | 86.782.7 | 72.174.8 | 94.811.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).