1. Introduction

Corrosive injuries still become medical problems in acute phase and also delayed complications include esophageal, pyloric stricture and squamous cell carcinoma [

1], impair social, physical, emotional, and quality of life [

2]. About 13.5% - 22% of the patients will develop strictures [

5,

6]. Stricture on esophagus and pylorus are the most prevalent delayed sequelae and endoscopic dilatation is primary therapy [

7].

In the last 4 years (2018-2022) there were 36 corrosive injuries at Endoscopy unit Dr. Soetomo General Hospital Surabaya with 15 (41,6%) strictures on esophagus, pylorus or both.

Esophageal strictures related corrosive injury frequently long, tight [

8,

9] and multiple sites, which required endoscopic or surgery intervention [

2,

10]. Endoscopic dilatation is the first-line therapy for stricture related corrosive injury [

2]. However, due to tight, long or tortuous stricture and insufficient visualization of the distal side of the lesion, endoscopic management is not always possible [

4] and require fluoroscopy to ensure proper guidewire placement before dilatation. Because radiologic facilities are not available in every endoscopy units, the initial assessment and treatment may be delayed [

11]. One of the most important steps in dilatation is the proper placement of the guide wire beyond the stricture [

4]. The ultrathin endoscope (≤ 6mm) could pass through the stricture easier than conventional endoscope, allowing the guide wire to be inserted, evaluate distal side of the lesion and measure the length and characteristics of the stenosis [

4].

This study will describe the clinical outcome of endoscopic dilatation with Ultrathin Endoscope Assisted Method including clinical improvement, success rate, refractory rate, recurrent rate, and complications during and after procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

Retrospective study of patients with esophageal and/or pyloric stricture after corrosive injury who underwent endoscopic dilatation at Soetomo General Hospital from July 2018 – July 2022. Data such as age, gender, caustic agent, type of stricture, number of dilatations, increasing of body weight and outcome of endoscopic therapy were recorded.

Anatomical type of stricture was classified into simple and complex. Simple strictures are symmetric or concentric, short, diameter 12mm or more and easily passed by endoscope. Complex strictures are asymmetry, diameter <12 mm or inability to pass an endoscope [

12].

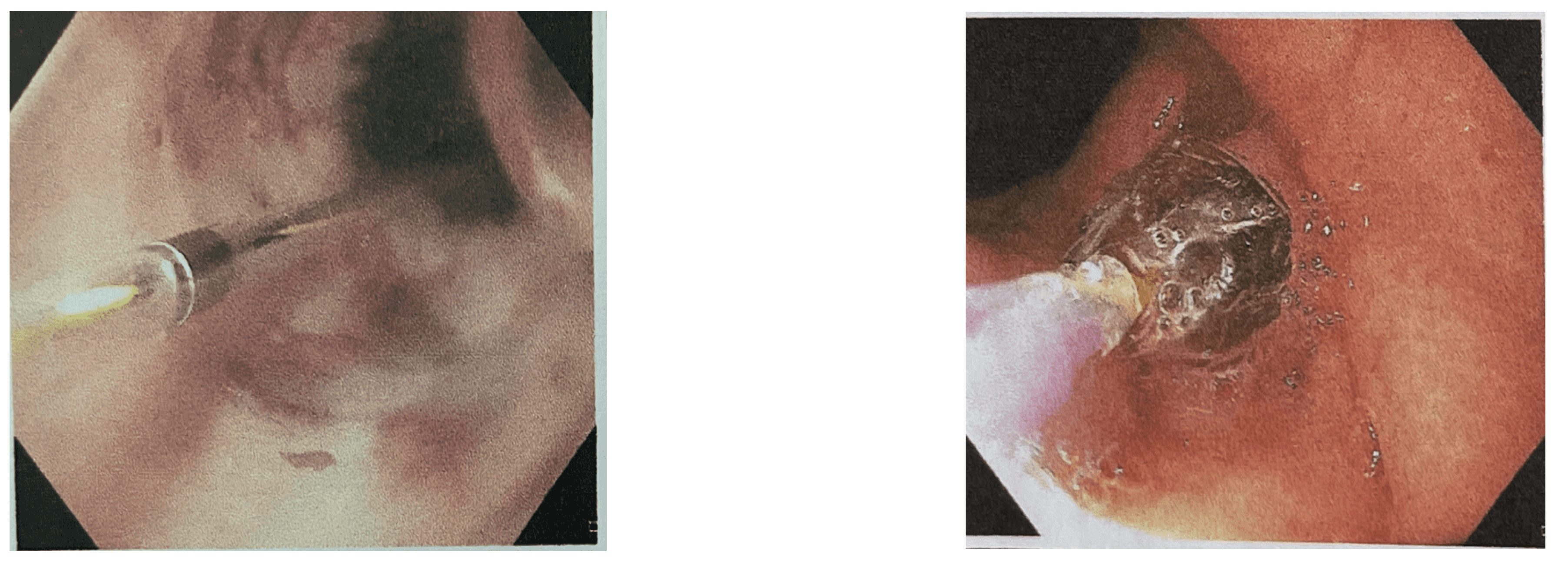

All procedures were performed under general anaesthesia. First, conventional gastroscope (GIF-HQ190, Olympus) was inserted to the stricture area. If conventional endoscope guide wire insertion failed, an ultrathin endoscope (GIF XP260; Olympus) was traversted and approached directly in front of the stenotic lesion orifice. The guidewire was inserted through the working channel of the ultrathin endoscope and then removed completely, leaving the guide wire in place. The opposite side of the guide wire was grabbed and retrieved through the working channel of the conventional scope [

4].

Endoscopic dilatation was performed using Through The Scope (TTS) balloon dilator or Endoscopic bougie dilatation. Endoscopic TTS balloon dilator was inserted using guidewire through accessory channel with a minimum of 5 mm to a maximum 18 mm diameter. The dilator was slowly inflated with liquid to certain pressures, usually 1, 2, and 3 atmosphere and maintained for 2–3 min and then deflated. The procedure will be repeated two or three times with a stepwise larger pressure to achieved target diameter gradually from gradual stepwise dilatation from a diameter of 5 mm to 7, 9, 11-, 12.8-, 14, and 15-mm [

13].

Endoscopic bougie dilatation was performed using Wire-guided Polyvinyl dilator Savary-Gilliard/SG. The scope was introduced to evaluate the anatomy, and then bougie dilator was passed over the metal guidewire. The first dilator was chosen based on the estimated diameter of the esophageal stricture. Sensation of resistance during dilatation on this dilator protecting from over-dilatation [

10]. In order to prevent adverse event particularly perforation we use “Rule of Three” which means that the stricture is dilated no more than 3 mm per session using three consecutive bougies once moderate resistance is encountered [

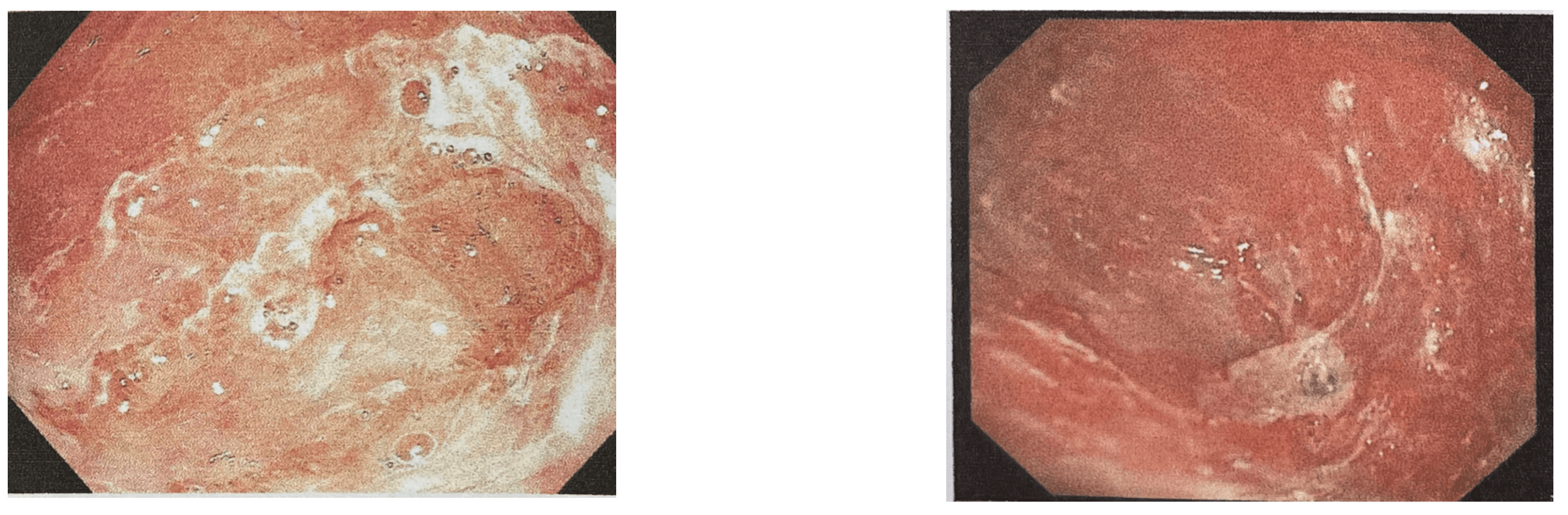

14]. After dilation the endoscope was inserted to evaluate the dilatation and complications such as bleeding or perforation. Bougie dilation was the first choice to stretch the simple esophageal stricture. The tortuous, long esophageal stricture or pyloric stricture were dilated with balloon dilator. One week after the first dilation, patients were advised to return to the hospital for endoscopic evaluation and re-dilatation until the target diameter of 14mm was achieved. Triamcinolone acetonide was injected on surrounding stricture area (4 quadrants, 20mg each) [

8]. All patients had written informed consent before endoscopic dilatation.

We followed the Kochman criteria definitions for refractory and recurrent strictures. Refractory stricture was classified if the diameter of the stricture could not reach 14 mm over four sessions of dilatation. Recurrent stricture happened if it could not maintained a luminal diameter for 4 weeks once the target diameter of 14 mm had been achieved [

15]. Successful Outcome was defined as relief in dysphagia, increasing of body weight or achieving a diameter for 15 mm after endoscopic dilatation without requiring endoscopic procedure or surgical intervention for at least 6 months [

2]. Esophageal dilatation can be performed under the combination endoscopy and fluoroscopy or endoscopy alone [

10].

4. Discussion

The corrosive injury occurred when a wide range of chemicals substance with pH<2 or pH>12 are swallowed accidently or suicide attempt and cause tissue damage and destruction. Adults between the ages of 30 and 40 typically ingest strong corrosives with suicide attempt and present with severe, life-threatening injuries [

6].

Due to the 'liquefaction necrosis' of alkaline substances, corrosive injury from alkali can be more damaging to the gastrointestinal tract than 'coagulation necrosis' from acid ingestion. Previous reports suggest that alkali usually destroys the esophagus, while acid primarily damages the stomach. But in case of massive ingestion, both acids and alkalis may cause extensive necrosis of the gastrointestinal tract. Strong acids resulted coagulation necrosis that protect esophagus from damage and penetration to the deep layer. The epithelial layer and the alkaline pH on esophageal wall had protective effect. But this study showed that acid substance had destruction effect on both esophagus and gaster in almost similar proportion. Gastroesophageal reflux of corrosive agent due to impaired lower esophageal sphincter and motility dysfunction resulted corrosive injury and stricture at esophagus as well as gastric injury. Pyloric spasm prolonged gastric contact time and this explained the pyloric involvement in 8 (72.7%) patients in this study [

6,

16]. Corrosive injury located at duodenum appeared to be rare and less severe because of pyloric spasm [

10].

In this study the dominant causative agents are strong acid substance (Hydrogen Chloride 8,3% -20%) from household cleaning that easily accessible. Acid ingestion is more common in Asian countries while alkali account for most severe caustic injuries in western Europe and South America [

6,

10].

After strong corrosive agent ingestion of the esophagus can be divided into 3 stages as follows:

Acute necrosis and thrombosis occurs 1-4 days after ingestion

Ulceration and granulation phase occurs 3-12 days. During this stage, mucosal shedding, bacterial colonization, and granulation formation are evident. The esophagus is in its most fragile stage. All operations such as laparoscopy or dilatation must be performed very carefully

Healing period begins 3 weeks after the injury. It usually takes 1-6 months for the wound to heal completely. Any surgical attempt for non-dilatable stenosis should wait after this period [

10]. During the third week, scar retraction leading to stricture formation and progresses over several months. Esophageal dysfunction due to scarring combined with gastroesophageal reflux will accelerate scarring [

6].

The severity of injury depends on the acidity of the agent, contact time, amount, and purpose of ingestion. The purpose has important predictor and intentional ingestion (suicide); which is the most mode of ingestion in this study is correlated with severe injury and stricture [

6,

13]. Patients at risk for stricture had a high endoscopic grade, consumed strong acid or alkali, leukocytosis, and a low thrombin ratio [

10]. The severity of esophageal wall stricture is determined by the depth of necrosis. Full-thickness necrosis causes strictures and even perforation within 2 to 4 weeks [

16]. The likelihood of developing a stricture after an esophageal burn of grade 2B and grade 3 may be 71% and 100%, respectively [

17].

Corrosive strictures can involve all oesophageal segments, multiple, long, irregular and frequent refractory to dilatation compared to other causes of benign stricture. Dysphagia and decreasing of body weight are the most common symptoms related esophageal stricture or gastric outlet obstruction related pyloric stricture. The most relevant symptom is progressive dysphagia to solid food, and this sometimes progresses to involve semisolid and liquid foods [

14]. Some patients may present with nutritional deficiencies and weight loss in addition to persistent dysphagia or odynophagia [

18].

Endoscopic dilation is the first-line management option. Early endoscopic dilatation effectively prevents surgery. The best time for dilatation is after the acute injury has healed, which is usually around the third week. Late management is associated with significant fibrosis and collagen deposition in the esophageal wall, necessitating more endoscopic sessions for adequate dilatation and resulting in a significantly higher number of refractory and recurrent strictures. The practice is supported by the majority of evidence-based guidelines [

2,

7,

19]. Other endoscopic modalities for esophageal strictures currently include needle knife dissection, argon plasma coagulation (APC), temporary stent placement, laser cannulation, and self-dilation. But treatment options are limited if complete luminal occlusion occurred [

20].

In this study 6 (54,6%) patients admitted to hospital and underwent endoscopic dilatation 1-6 months after injury. The improvement of symptoms and nutritional status are the main goal of treatment rather than conserving large oesophageal lumen patency [

6].

Study by Tharavej et al. reported that majority of patients with acid-induced corrosive esophageal stricture required more sessions and were frequently refracter to dilatation. Esophageal dilatations were successful in one-fourth of the patients. Concomitant cricopharyngeal stricture, long stricture, requiring frequent dilatation, and refractory to >11 mm dilatation were factors associated with failed dilatation [

13].

The type of dilator used will be determined by availability and experience with the particular device. There is no agreement on how these patients should be followed up. We do dilatation program for short intervals (weekly or biweekly) until the ultimate goal of elimination of dysphagia is achieved than extended three weekly, one month, two months or three months until persistent improvement and are already asymptomatic.

Esophageal dilatation using Savary bougies are preferred to balloon dilators although studies have shown no clear advantage of one method over the other [

6]. Systematic review and meta-analysis showed that there was no difference in symptomatic relief, recurrence rate at 12 months, bleeding, or perforation between bougie and balloon dilation of benign esophageal stricture [

21].

Balloon dilators delivered a radial and simultaneous dilating force across the entire length of the stricture, whereas bougie dilators delivered both a radial and a longitudinal force from the most proximal to the most distal portion of the stricture [

5].

Joshi et al. reported endoscopic dilatation with SG dilators was successful in 71.8% of patients whereas refractory and recurrent strictures were 1.5% and 7.8% respectively. Endoscopic dilatation outcome was associated with increasing stricture length (more than 6 cm) [

2].

The ability to traverse any esophageal stricture is determined by the stricture's complexity. Endoscopically, the presence of a patent lumen within the stricture and the diameter of the lumen are two important factors that determine the methods and success of traversing the stricture. As a result, the preferred techniques for traversing esophageal strictures will differ depending on whether the strictures are simple, complex with patent lumen, or complex with complete occlusion [

9]. In this study there were 6 complex esophageal stricture and 5 (83%) patients were successfully dilated.

Recurrent esophageal stricture in 2 patients happened 3 - 4 weeks after target diameter was achieved. The strictures were complex, long and multisite. Recurrent pyloric stricture was earlier and more frequent than esophageal stricture due to ongoing inflammation and fibrotic process (

Table 2).

Although endoscopic balloon dilatation has been shown to be effective in treating gastric outlet obstruction in patients with short strictures but perforation and failure are common [

6]. We recorded 1 patient with retrosternal pain without any sign of perforation.

Recurrent and refractory stricture after endoscopic dilatation need further investigation and treatment. The response to dilatation can be predicted using CT or endoscopic ultrasound wall thickness. Patients with an esophageal wall thickness greater than 9 mm on CT scan required significantly more dilatations than those with a wall thickness less than 9 mm [

22]. There are no established guidelines for the treatment of refractory strictures [

8].

It has been suggested that dilatations should be stopped, and reconstructive surgery should be considered after five to seven unsuccessful sessions. However, additional patient-related considerations like age, malnutrition, and operative risks, as well as the surgeon's experience and the availability of other surgical choices [

6]. In this study 2 patients with recurrent and refractory stricture refused to perform digestive surgery and continued dilatation procedures. In the 15

th sessions the target dilatation was achieved.

The emergence of interventional endoscopy has renewed interest in intraluminal stenting to prevent stricture recurrence after dilation. Although silicone rubber, polyflex, and biodegradable stents have shown promising results, their widespread clinical use is currently inhibited by issues such as hyperplastic tissue growth, removal difficulties, a high migration rate (25%), a high recurrence rate (50%), low availability, and high costs [

6].

Endoscopic stent placement can improve the duration of time without symptoms, dilate the stricture segment repeatedly, and reduce the suffering caused by repeated dilations. Most medical professionals believe that 4 to 8 weeks is the right amount of time for the esophageal stent to remain in place. If the duration is too short, the cicatricial tissue in the stricture segment cannot be organized completely, which increases the risk of recurrent strictures, and if the duration is too long, serious connective tissue proliferation is inevitable and stent removal becomes challenging [

2]. Recurrence rates of refractory strictures after stent removal are as high as 69%, particularly in patients with long strictures (>7cm) [

19]. Intralesional steroid injections enhance the effects of endoscopic dilation, and topical mitomycin can be effective in the treatment of complex strictures; such combined approaches should be discussed before deciding on surgery [

6]. Steroid had inhibitory effect on the inflammatory response to reduce stricture formation, collagen synthesis, fibrosis and chronic scarring [

14].

Patients with dilatation failure can undergo esophageal replacement surgery using stomach, jejunum, or colonic conduits. In patients requiring esophageal replacement surgery, the timing of surgery, resection or bypass, type of conduit and route of placement, as well as the site of proximal anastomosis as determined by the extent of caustic injury to the hypopharynx and proximal esophagus, should all be carefully considered. A gastric pull-up is usually preferred in patients with isolated esophageal involvement, low stricture, and a normal stomach, whereas patients with pharyngo-esophageal strictures or combined esophageal and stomach involvement require a colonic conduit [

2].

Regarding the adverse event, there was 1 patient with retrosternal chest pain and relieved with pain killer drug. No perforation nor mediastinitis recorded.