Submitted:

03 April 2023

Posted:

04 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

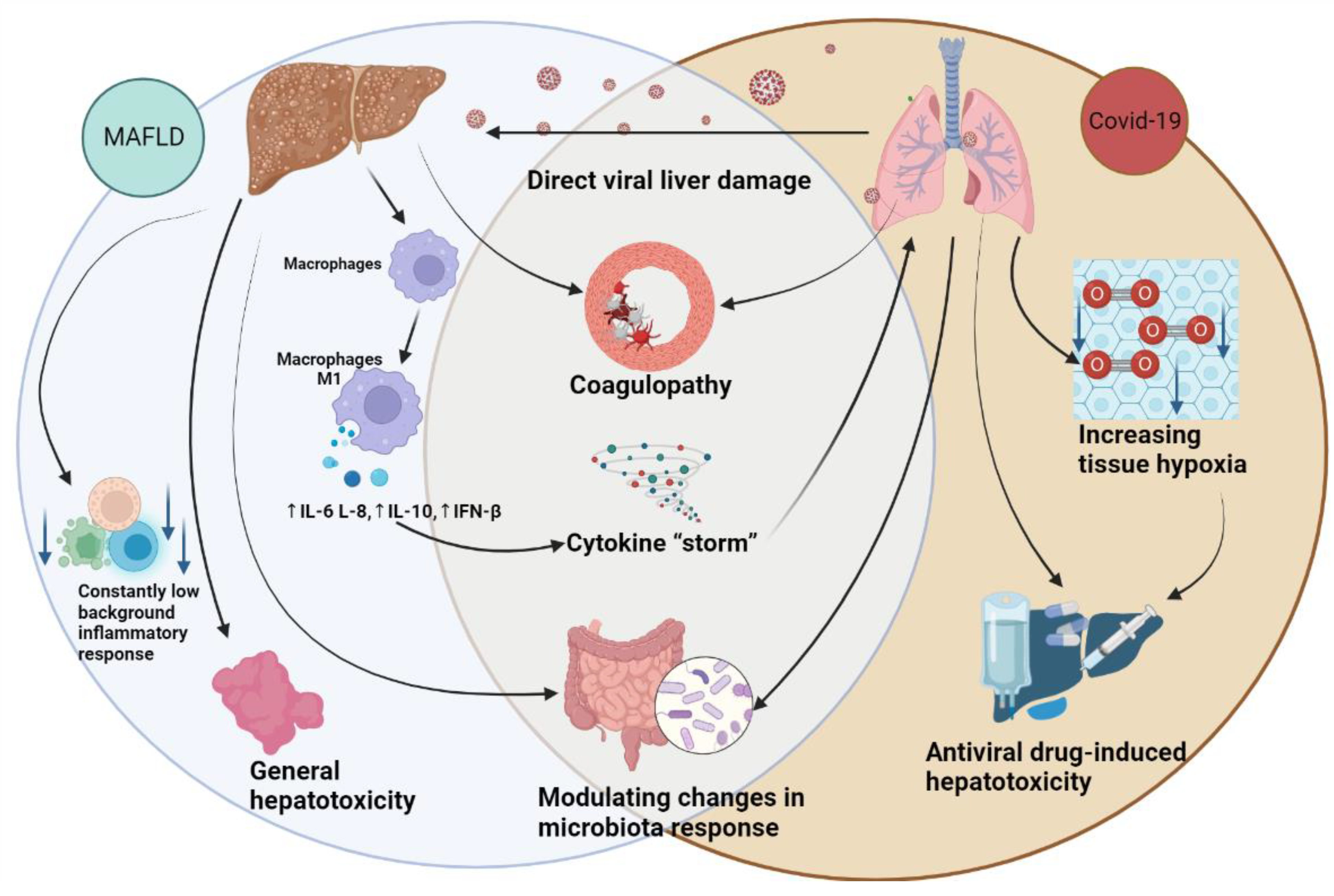

2. The role of MAFLD in the progression of COVID-19

| References | Was used in meta-analysis (total number) | Contry of study | Study design, included patients (total/NAFLD, MAFLD) | Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou et al., 2020 [57] | [72,73,74,75,76](5) | China | Retrospective, matched cohorts, 110/55 | Independent of other confounding factors, the presence of MAFLD among patients below 60 years of age is positively associated with the development of severe or critical COVID-19. | Matching of patients was not performed based on the primary outcome variable. |

| Zhou et al., 2020 [58] | [72,73,74,75,77] (5) | China | Retrospective cohort study, 327/93 | Younger patients with MAFLD have a higher risk for severe COVID progression or mortality. | A minor sample size of the older cohort of patients |

| Zheng et al., 2020 [59] | [73,74,76] (3) | China | Retrospective cohort study, 214/66 | Co-occurring obesity in patients with MAFLD was found to increase the risk of severe illness by over six times. | Patients did not undergo liver biopsy. Waist circumference was not measured in patients. Patients were only of Asian ethnicity |

| Huang et al., 2020 [45] | [72,73,76] (3) | China | Retrospective cohort study, 280/66 | SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients NAFLD is positively associated with an elevated risk of liver injury development. However, no patient with COVID-19 with NAFLD developed severe liver injury. | HSI was employed for the purpose of identifying the presence of NAFLD in the absence of any known liver pathologies. |

| Ji et al., 2020 [46] | [72,73,74,75,76,77] (6) | China | Retrospective cohort study, 202/76 | Injury in patients with COVID-19 was frequent but mild in nature. | Small sample size, the Asian cohort. Very different co-morbidities among groups, definition of NAFLD only through IHS. |

| Targher et al., 2020 [47] | [72,73,74,75,76] (5) |

China | Retrospective cohort study, 310/94 | More severe COVID-19 with higher FIB-4 or NFS. | Small sample size, the Asian ancestry of the cohort and the use of NFS without a histological diagnosis of liver fibrosis. No full paper |

| Gao et al., 2021 [60] | [72,73,74,75,76] (5) |

China | Retrospective case-control study, 130/65 | The presence of MAFLD in nondiabetic patients was associated with a four-fold increased risk of severe COVID-19. | Diagnosing NAFLD only by CT and clinical criteria. Same patients with Zhou et al. 2020 [57] |

| Chen et al., 2021 [48] | [73,76] (2) | USA | Retrospective single-center cohort study, 342/178 | The presence of HS in COVID-19 patients was observed to correlate with augmented disease severity and transaminitis. | Comorbidities were not taken into account. Metabolic status is not balanced. Using the HSI and imaging to define HS. |

| Hashemi et al., 2020 [61] | [72,73,77] (3) | USA | Retrospective cohort study,363/55 | NAFLD significantly associated with ICU admission and with needing mechanical ventilation. | Using both imaging studies and histopathology for diagnosing LCD. Patients with milder courses of COVID-19, potentially over-estimating the effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the liver |

| Bramante et al., 2020 [49] | [72,73,76] (3) | USA | Retrospective cohort study, 6400/373 | Covid-19 hospitalization is significantly associated with the presence of NAFLD/NASH, and this risk appears to be attributable to obesity. | The presence of unmeasured confounders and residual bias may impact the validity of the results. |

| Kim et al., 2021 [50] | [73,75] (2) | USA | Multicenter Observational cohort study, 867/456 | NAFLD does not have any risk factors for severe progression or mortality of COVID-19. | No control cohort wth liver disease, NAFLD ICD diagnosis. |

| Steiner et al., 2020 [62] | [77] (1) | USA | Cross-sectional study, 396/213 | The likelihood of severe COVID-19 manifestation was higher among patients with NAFLD. | NAFLD was defined through imaging. Lack of information about metabolic status, no full paper. |

| Marjot et al., 2021 [78] | [75] (1) | UK, USA | Retrospective cohort study, 932/362 | Patients with AIH were the same risk-averse outcomes as CLD causes (including NAFLD). | No clear NAFLD definition. Comparing only AIH and CLD cohorts. |

| Marjot et al., 2021 [44] | [76] (1) | UK (origin) but data is multinational | Retrospective cohort study, 1345/322 | No increased mortality of patients with NAFLD. | There were no specific cohorts for NAFLD patients. No words about NAFLD definition. |

| Forlano et al., 2020 [63] | [73,75,76,77] (4) | UK | Retrospective cohort study, 193/61 | The presence of NAFLD was not associated with worse outcomes in patients with COVID-19. NAFLD patients were younger on admission. | Study population was small. Only visualization methods were used. |

| Vázquez-Medina et al., 2022 [51] | [75] (1) | Mexico | Retrospective cohort study, 359/ NAFLD – 79, MAFLD – 220. | The MAFLD cohort displayed a higher fatality rate, whereas the NAFLD group did not exhibit any marked distinction. | Using a noninvasive method for defining NAFLD and MAFLD. |

| Moctezuma-Velázquez et al., 2021 [64] | [75] (1) | Mexico | Retrospective cohort study, 470/359 | NAFLD as per the DSI was associated with death and IMV need in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. | Definition NAFLD based on DSI, CT. |

| Lopez-Mendez et al., 2020 [52] | [73,76](2) | Mexico | Retrospective, cross sectional study,155/66 | Prevalence of HS and significant liver fibrosis was high in COVID-19 patients but was not associated with clinical outcomes. | Estimating liver fibrosis through non-invasive models. |

| Mahamid et al., 2021 [65] | [72,73,75,76,77] (5) |

Israel | Retrospective case-control study, 71/22 | The risk of severe COVID-19 is elevated in patients with NAFLD, regardless of gender and irrespective of the presence of metabolic syndrome. | Differences in metabolic status between groups, the small number of COVID-19 patients underwent CT to diagnose NAFLD |

| Mushtaq et al., 2021 [53] | [77] (1) | Qatar | Retrospective cohort study, 269/320 | The presence of NAFLD is a predictor of mild or moderate liver injury, but not for mortality or COVID-19 severity. | Using HSI index for diagnosing. No full paper. |

| Parlak et al., 2021 [66] | [76] (1) | Turkey | Retrospective cohort study, 343/55 | NAFLD was an independent risk factor for COVID-19 severity. | Definition NAFLD based on CT. Missed data comparing NAFLD and non-NAFLD cohorts |

| Yoo et al., 2021 [54] | [75] (1) | South Korea | Retrospective cohort study, 72244/54913 (HIS - 26 041, FLI - 19 945, claims-based - 8 927). |

Patients with pre-existing NAFLD have a higher likelihood severe COVID-19 illness. | Using HIS, FLI and claims-based NAFLD for defining fat liver for the same patients. |

| Vrsaljko et al., 2022 [67] | [75] (1) | Croatia | Prospective cohort study, 216/120 | NAFLD is associated with higher COVID-19 severity, more adverse outcomes, and more frequent pulmonary thrombosis. | Abdominal ultrasound was employed for the diagnosis of NAFLD. |

| Valenti et al., 2020 [79] | N/A | UK | Mendelian randomization, 1460/526 | The predisposition for severe COVID-19 is not directly augmented by a genetic propensity for hepatic fat accumulation. | These results were obtained in an initial set of cases without detailed characterization. No full paper. |

| Liu et al., 2022 [80] | N/A | UK | Mendelian randomization, N = 2 586 691 | No evidence to support a causal relationship between COVID-19 susceptibility/severity and NAFLD. | Potential data errors, limited patient characterization. Missing information about NAFLD cohort. No full paper |

| Roca-Fernández et al., 2021 [81] | N/A | UK | Prospective cohort study (UK Biobank), 1043/327 | Patients with fatty liver disease were at increased risk of infection and hospitalization for COVID-19 | Small proportion of UKB participants. Restriction for blood biomarkers of liver disease. |

| Simon et al., 2021 [68] | N/A | Sweden | Matched cohort study using the ESPRESSO, 182 147/42320-LCD, 6350-NAFLD | Patients with CLD had a higher risk of hospitalization for COVID-19, but did not have an increased risk of severe COVID-19. | There is no comparison for NAFLD cohort. Not every CLD was confirmed though biopsy. The cohort lacked detailed data regarding body mass index or smoking. |

| Chang et al., 2022 [55] | N/A | South Korea | Retrospective cohort study, 3112 – FLI score | An augmented risk of severe COVID-19 complications was observed in patients with high fatty liver index (FLI), reflective of NAFLD. | Using FLI score for determining NAFLD. Dataset did not directly confirm NAFLD through biopsy or ultrasound. The time gap between body measurements in health screening and COVID-19 infection |

| Okuhama et al., 2022 [69] | N/A | Japan | Retrospective cohort study, 222/ 89 – fatty liver | The manifestation of fatty liver on plain CT scan at the time of admission may constitute a risk factor for severe COVID-19. | No determination NAFLD/MAFLD. Using CT scan for screening fat liver disease. |

| Tripon et al., 2022 [56] | N/A | French | Retrospective cohort study, 719/ 311 | Patients with NAFLD disease and liver fibrosis are at higher risk of progressing to severe COVID-19. | Using NFS for determining NAFLD. Missing some important parameters. |

| Campos-Murguía et al., 2021 [70] | N/A | Mexico | Retrospective cohort study, 432/176 | In contrast to the presence of MAFLD, the occurrence of fibrosis is correlated with a heightened risk of severe COVID-19 and mortality. | Liver steatosis was diagnosed by CT scan, and fibrosis by non-invasive scores. |

| Ziaee et al., 2021 [71] | N/A | Iran | Retrospective cohort study, 575/218 | Fatty liver is significantly more prevalent among COVID-19 against non-COVID-19 patients, they develop more severe disease and tend to be hospitalized for more extended periods. | There was no access to each patient's past medical history, so the term “fatty liver patients” was used. The lack of diagnosis data for control group patients |

3. The Hepatic Implications of COVID-19

4. Liver susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection

5. Imbalance of intestinal microbiota

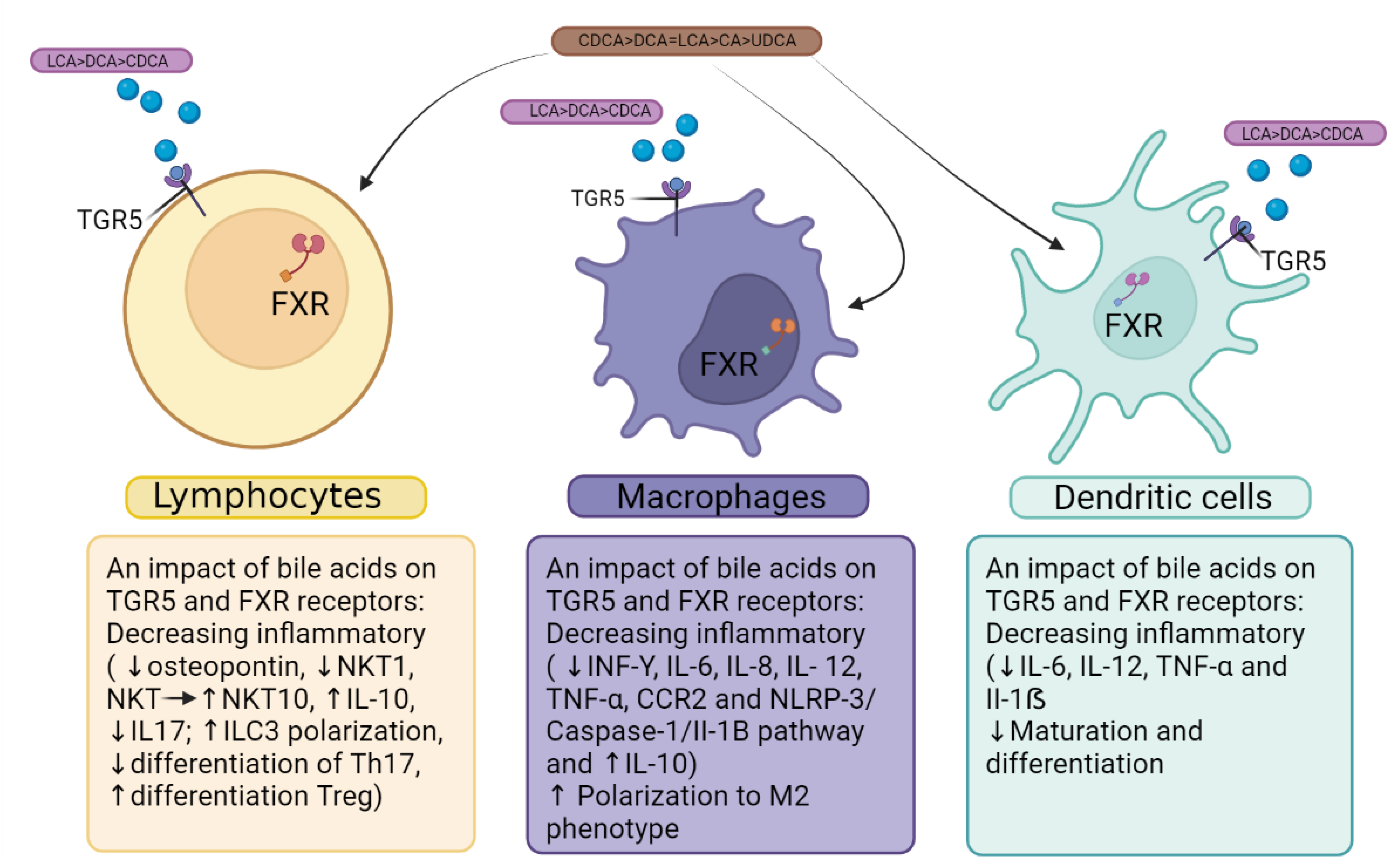

6. Bile acid receptors FXR and TGF5 as a linking factor of the immunopathogenesis of COVID-19 and MAFLD

6. Conclusions and perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Director General’s speeches WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. WHO Dir. Gen. speeches 2020, 4.

- World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data | WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data. World Heal. Organ. 2021, 1–5.

- Tian, W.; Jiang, W.; Yao, J.; Nicholson, C.J.; Li, R.H.; Sigurslid, H.H.; Wooster, L.; Rotter, J.I.; Guo, X.; Malhotra, R. Predictors of Mortality in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1875–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, J.L.; Lieberman-Cribbin, W.; Tuminello, S.; Taioli, E. Male Sex, Severe Obesity, Older Age, and Chronic Kidney Disease Are Associated With COVID-19 Severity and Mortality in New York City. Chest 2021, 159, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. jin; Cao, Y. yuan; Tan, G.; Dong, X.; Wang, B. chen; Lin, J.; Yan, Y. qin; Liu, G. hui; Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A.; et al. Clinical, Radiological, and Laboratory Characteristics and Risk Factors for Severity and Mortality of 289 Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 76, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebinge, J.E.; Achamallah, N.; Ji, H.; Clagget, B.L.; Sun, N.; Botting, P.; Nguyen, T.T.; Luong, E.; Ki, E.H.; Park, E.; et al. Pre-Existing Traits Associated with Covid-19 Illness Severity. PLoS One 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.J.; Walker, A.J.; Bhaskaran, K.; Bacon, S.; Bates, C.; Morton, C.E.; Curtis, H.J.; Mehrkar, A.; Evans, D.; Inglesby, P.; et al. Factors Associated with COVID-19-Related Death Using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020, 584, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, S.; Yu, M.; Wang, K.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhou, M.; Wu, B.; Yang, Z.; et al. Risk Factors for Severity and Mortality in Adult COVID-19 Inpatients in Wuhan. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyshnyi, A.; Krynytska, I.; Matskevych, V.; Marushchak, M.; Lushchak, O. Arterial Hypertension as a Risk Comorbidity Associated with COVID-19 Pathology. Int. J. Hypertens. 2020, 2020, 8019360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zheng, K.I.; Wang, X.B.; Sun, Q.F.; Pan, K.H.; Wang, T.Y.; Chen, Y.P.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; George, J.; et al. Obesity Is a Risk Factor for Greater COVID-19 Severity. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, E72–E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.H.; Lee, S.A.; Chun, S.Y.; Song, S.O.; Lee, B.W.; Kim, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. Clinical Outcomes of COVID-19 Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Population-Based Study in Korea. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 35, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, J.M.; Mateen, B.A.; Sonabend, R.; Thomas, N.J.; Patel, K.A.; Hattersley, A.T.; Denaxas, S.; McGovern, A.P.; Vollmer, S.J. Type 2 Diabetes and Covid-19– Related Mortality in the Critical Care Setting: A National Cohort Study in England, March–July 2020. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Kamyshna, I.; Nykyforuk, A.; Yao, R.; Imbery, J.F.; Oksenych, V.; Korda, M.; Kamyshnyi, A. Immunoregulatory Intestinal Microbiota and COVID-19 in Patients with Type Two Diabetes: A Double-Edged Sword. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyshnyi, O.; Matskevych, V.; Lenchuk, T.; Strilbytska, O.; Storey, K.; Lushchak, O. Metformin to Decrease COVID-19 Severity and Mortality: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenblock, C.; Schwarz, P.E.H.; Ludwig, B.; Linkermann, A.; Zimmet, P.; Kulebyakin, K.; Tkachuk, V.A.; Markov, A.G.; Lehnert, H.; de Angelis, M.H.; et al. COVID-19 and Metabolic Disease: Mechanisms and Clinical Management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, S.; Gillies, C.; Zaccardi, F.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Yates, T.; Singh, A.K.; Davies, M.J.; Khunti, K. The Impact of Obesity on Severe Disease and Mortality in People with SARS-CoV-2: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrinol. diabetes Metab. 2021, 4, e00176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayres, J.S. A Metabolic Handbook for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N. Causes, Consequences, and Treatment of Metabolically Unhealthy Fat Distribution. lancet. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avula, A.; Nalleballe, K.; Narula, N.; Sapozhnikov, S.; Dandu, V.; Toom, S.; Glaser, A.; Elsayegh, D. COVID-19 Presenting as Stroke. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, M.; Campopiano, M.C.; Mantuano, M.; Mazoni, L.; Coppelli, A.; Del Prato, S. COVID-19 in People with Diabetes: Understanding the Reasons for Worse Outcomes. lancet. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Kleinridders, A.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin Receptor Signaling in Normal and Insulin-Resistant States. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Magro, D.O.; Evangelista-Poderoso, R.; Saad, M.J.A. Diabetes, Obesity, and Insulin Resistance in COVID-19: Molecular Interrelationship and Therapeutic Implications. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, S.; Thomas, R.; Shihab, P.; Sriraman, D.; Behbehani, K.; Ahmad, R. Obesity Is a Positive Modulator of IL-6R and IL-6 Expression in the Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue: Significance for Metabolic Inflammation. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0133494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, N.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Piette, J.; Scheen, A.J.; Paquot, N. Inflammation as a Link between Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 105, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Newsome, P.N.; Sarin, S.K.; Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Dufour, J.-F.F.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. A New Definition for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: An International Expert Consensus Statement. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.W.-S.; Wong, G.L.-H.; Woo, J.; Abrigo, J.M.; Chan, C.K.-M.; Shu, S.S.-T.; Leung, J.K.-Y.; Chim, A.M.-L.; Kong, A.P.-S.; Lui, G.C.-Y.; et al. Impact of the New Definition of Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease on the Epidemiology of the Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2021, 19, 2161–2171.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Y.; Byrne, C.D.; Musso, G. A Single-Letter Change in an Acronym: Signals, Reasons, Promises, Challenges, and Steps Ahead for Moving from NAFLD to MAFLD. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 15, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.; Tacke, F.; Arrese, M.; Chander Sharma, B.; Mostafa, I.; Bugianesi, E.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Yilmaz, Y.; George, J.; Fan, J.; et al. Global Perspectives on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2019, 69, 2672–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyelade, T.; Alqahtani, J.; Canciani, G. Prognosis of COVID-19 in Patients with Liver and Kidney Diseases: An Early Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical Course and Risk Factors for Mortality of Adult Inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Lancet (London, England) 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhou, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Du, C.; et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangash, M.N.; Patel, J.; Parekh, D. COVID-19 and the Liver: Little Cause for Concern. lancet. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shi, L.; Wang, F.-S. Liver Injury in COVID-19: Management and Challenges. lancet. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England) 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckmans, J.; Rodrigues, R.M.; Demuyser, T.; Piérard, D.; Vanhaecke, T.; Rogiers, V. COVID-19 and Drug-Induced Liver Injury: A Problem of Plenty or a Petty Point? Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 1367–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquissi, F.C. Immune Imbalances in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From General Biomarkers and Neutrophils to Interleukin-17 Axis Activation and New Therapeutic Targets. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazankov, K.; Jørgensen, S.M.D.; Thomsen, K.L.; Møller, H.J.; Vilstrup, H.; George, J.; Schuppan, D.; Grønbæk, H. The Role of Macrophages in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merad, M.; Martin, J.C. Pathological Inflammation in Patients with COVID-19: A Key Role for Monocytes and Macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zheng, K.I.; Yan, H.-D.; Sun, Q.-F.; Pan, K.-H.; Wang, T.-Y.; Chen, Y.-P.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; George, J.; et al. Association and Interaction Between Serum Interleukin-6 Levels and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Patients With Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2021, 12, 604100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, M.; Chironi, G.; Claessens, Y.-E.; Farhad, R.L.; Rouquette, I.; Serrano, B.; Nataf, V.; Hugonnet, F.; Paulmier, B.; Berthier, F.; et al. COVID-19 Pneumonia: Relationship between Inflammation Assessed by Whole-Body FDG PET/CT and Short-Term Clinical Outcome. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inciardi, R.M.; Solomon, S.D.; Ridker, P.M.; Metra, M. Coronavirus 2019 Disease (COVID-19), Systemic Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e017756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, B.; Mao, J. The Pathogenesis and Treatment of the `Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasques-Monteiro, I.M.L.; Souza-Mello, V. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Severity in Obesity: Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in the Spotlight. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjot, T.; Moon, A.M.; Cook, J.A.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Aloman, C.; Armstrong, M.J.; Pose, E.; Brenner, E.J.; Cargill, T.; Catana, M.-A.; et al. Outcomes Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease: An International Registry Study. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Xue, L.; Liu, L.; Yan, X.; Huang, S.; Li, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhang, B.; et al. Clinical Features of Patients With COVID-19 With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 1758–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Qin, E.; Xu, J.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, G.; Wang, Y.; Lau, G. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases in Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Study. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Mantovani, A.; Byrne, C.D.; Wang, X.-B.; Yan, H.-D.; Sun, Q.-F.; Pan, K.-H.; Zheng, K.I.; Chen, Y.-P.; Eslam, M.; et al. Risk of Severe Illness from COVID-19 in Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Increased Fibrosis Scores. Gut 2020, 69, 1545–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, V.L.; Hawa, F.; Berinstein, J.A.; Reddy, C.A.; Kassab, I.; Platt, K.D.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Steiner, C.A.; Louissaint, J.; Gunaratnam, N.T.; et al. Hepatic Steatosis Is Associated with Increased Disease Severity and Liver Injury in Coronavirus Disease-19. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramante, C.; Tignanelli, C.J.; Dutta, N.; Jones, E.; Tamariz, L.; Clark, J.M.; Usher, M.; Metlon-Meaux, G.; Ikramuddin, S. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Risk of Hospitalization for Covid-19. medRxiv Prepr. Serv. Heal. Sci. 2020, 2020.09.01.20185850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Adeniji, N.; Latt, N.; Kumar, S.; Bloom, P.P.; Aby, E.S.; Perumalswami, P.; Roytman, M.; Li, M.; Vogel, A.S.; et al. Predictors of Outcomes of COVID-19 in Patients With Chronic Liver Disease: US Multi-Center Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1469–1479.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Medina, M.U.; Cerda-Reyes, E.; Galeana-Pavón, A.; López-Luna, C.E.; Ramírez-Portillo, P.M.; Ibañez-Cervantes, G.; Torres-Vázquez, J.; Vargas-De-León, C. Interaction of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Advanced Fibrosis in the Death and Intubation of Patients Hospitalized with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 2000–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Mendez, I.; Aquino-Matus, J.; Gall, S.M.-B.; Prieto-Nava, J.D.; Juarez-Hernandez, E.; Uribe, M.; Castro-Narro, G. Association of Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis with Clinical Outcomes in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection (COVID-19). Ann. Hepatol. 2021, 20, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, K.; Khan, M.U.; Iqbal, F.; Alsoub, D.H.; Chaudhry, H.S.; Ata, F.; Iqbal, P.; Elfert, K.; Balaraju, G.; Almaslamani, M.; et al. NAFLD Is a Predictor of Liver Injury in COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients but Not of Mortality, Disease Severity on the Presentation or Progression – The Debate Continues. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 482–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.W.; Jin, H.Y.; Yon, D.K.; Effenberger, M.; Shin, Y.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Yang, J.M.; Kim, M.S.; Koyanagi, A.; Jacob, L.; et al. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and COVID-19 Susceptibility and Outcomes: A Korean Nationwide Cohort. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Jeon, J.; Song, T.-J.; Kim, J. Association between the Fatty Liver Index and the Risk of Severe Complications in COVID-19 Patients: A Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripon, S.; Bilbault, P.; Fabacher, T.; Lefebvre, N.; Lescuyer, S.; Andres, E.; Schmitt, E.; Garnier-KepKA, S.; Borgne, P. Le; Muller, J.; et al. Abnormal Liver Tests and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Predict Disease Progression and Outcome of Patients with COVID-19. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2022, 46, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.-J.; Zheng, K.I.; Wang, X.-B.; Sun, Q.-F.; Pan, K.-H.; Wang, T.-Y.; Ma, H.-L.; Chen, Y.-P.; George, J.; Zheng, M.-H. Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease Is Associated with Severity of COVID-19. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2020, 40, 2160–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-J.; Zheng, K.I.; Wang, X.-B.; Yan, H.-D.; Sun, Q.-F.; Pan, K.-H.; Wang, T.-Y.; Ma, H.-L.; Chen, Y.-P.; George, J.; et al. Younger Patients with MAFLD Are at Increased Risk of Severe COVID-19 Illness: A Multicenter Preliminary Analysis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.I.; Gao, F.; Wang, X.-B.; Sun, Q.-F.; Pan, K.-H.; Wang, T.-Y.; Ma, H.-L.; Chen, Y.-P.; Liu, W.-Y.; George, J.; et al. Letter to the Editor: Obesity as a Risk Factor for Greater Severity of COVID-19 in Patients with Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Metabolism. 2020, 108, 154244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zheng, K.I.; Wang, X.B.; Yan, H.D.; Sun, Q.F.; Pan, K.H.; Wang, T.Y.; Chen, Y.P.; George, J.; Zheng, M.H. Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease Increases Coronavirus Disease 2019 Disease Severity in Nondiabetic Patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, N.; Viveiros, K.; Redd, W.D.; Zhou, J.C.; McCarty, T.R.; Bazarbashi, A.N.; Hathorn, K.E.; Wong, D.; Njie, C.; Shen, L.; et al. Impact of Chronic Liver Disease on Outcomes of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Multicentre United States Experience. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2020, 40, 2515–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, C.A.; Berinstein, J.A.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Louissaint, J.; Platt, K.D.; Reddy, C.A.; Kassab, I.A.; Hawa, F.; Gunaratnam, N.; Sharma, P.; et al. S1111 Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Associated With Increased Disease Severity in Patients With COVID-19. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, S560–S560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlano, R.; Mullish, B.H.; Mukherjee, S.K.; Nathwani, R.; Harlow, C.; Crook, P.; Judge, R.; Soubieres, A.; Middleton, P.; Daunt, A.; et al. In-Hospital Mortality Is Associated with Inflammatory Response in NAFLD Patients Admitted for COVID-19. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0240400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moctezuma-Velázquez, P.; Miranda-Zazueta, G.; Ortiz-Brizuela, E.; Garay-Mora, J.A.; González-Lara, M.F.; Tamez-Torres, K.M.; Román-Montes, C.M.; Díaz-Mejía, B.A.; Pérez-García, E.; Villanueva-Reza, M.; et al. NAFLD Determined by Dallas Steatosis Index Is Associated with Poor Outcomes in COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Cohort Study. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahamid, M.; Nseir, W.; Khoury, T.; Mahamid, B.; Nubania, A.; Sub-Laban, K.; Schifter, J.; Mari, A.; Sbeit, W.; Goldin, E. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Associated with COVID-19 Severity Independently of Metabolic Syndrome: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 1578–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlak, S.; Çıvgın, E.; Beşler, M.S.; Kayıpmaz, A.E. The Effect of Hepatic Steatosis on COVID-19 Severity: Chest Computed Tomography Findings. Saudi J. Gastroenterol Off. J. Saudi Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2021, 27, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrsaljko, N.; Samadan, L.; Viskovic, K.; Mehmedović, A.; Budimir, J.; Vince, A.; Papic, N. Association of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With COVID-19 Severity and Pulmonary Thrombosis: CovidFAT, a Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. Open forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, T.G.; Hagström, H.; Sharma, R.; Söderling, J.; Roelstraete, B.; Larsson, E.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Risk of Severe COVID-19 and Mortality in Patients with Established Chronic Liver Disease: A Nationwide Matched Cohort Study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuhama, A.; Hotta, M.; Ishikane, M.; Kawashima, A.; Miyazato, Y.; Terada, M.; Yamada, G.; Kanda, K.; Inada, M.; Sato, L.; et al. Fatty Liver on Computed Tomography Scan on Admission Is a Risk Factor for Severe Coronavirus Disease. J. Infect. Chemother. Off. J. Japan Soc. Chemother. 2022, 28, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Murguía, A.; Román-Calleja, B.M.; Toledo-Coronado, I.V.; González-Regueiro, J.A.; Solís-Ortega, A.A.; Kúsulas-Delint, D.; Cruz-Contreras, M.; Cruz-Yedra, N.; Cubero, F.J.; Nevzorova, Y.A.; et al. Liver Fibrosis in Patients with Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease Is a Risk Factor for Adverse Outcomes in COVID-19. Dig. liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2021, 53, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaee, A.; Azarkar, G.; Ziaee, M. Role of Fatty Liver in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients’ Disease Severity and Hospitalization Length: A Case-Control Study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2021, 26, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, P.J.; Váncsa, S.; Ocskay, K.; Dembrovszky, F.; Kiss, S.; Farkas, N.; Erőss, B.; Szakács, Z.; Hegyi, P.; Pár, G. Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Severe COVID-19: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 626425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Hussain, S.; Antony, B. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Huang, P.; Xie, X.; Xu, J.; Guo, D.; Jiang, Y. Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease Increases the Severity of COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Duan, G.; Yang, H. NAFLD Was Independently Associated with Severe COVID-19 among Younger Patients Rather than Older Patients: A Meta-Analysis. J. Hepatol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, U.; Ashfaq, M.Z.; Johnson, L.; Ford, R.; Wuthnow, C.; Kadado, K.; El Jurdi, K.; Okut, H.; Kilgore, W.R.; Assi, M.; et al. The Association of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease with Clinical Outcomes of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Kansas J. Med. 2022, 15, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Li, Y.; Cheng, B.; Zhou, T.; Gao, Y. Risk of Severe COVID-19 Increased by Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 55, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjot, T.; Buescher, G.; Sebode, M.; Barnes, E.; Barritt, A.S. 4th; Armstrong, M.J.; Baldelli, L.; Kennedy, J.; Mercer, C.; Ozga, A.-K.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Patients with Autoimmune Hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenti, L.; Jamialahmadi, O.; Romeo, S. Lack of Genetic Evidence That Fatty Liver Disease Predisposes to COVID-19. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, P.; Zhao, J. Assessing Causal Relationships between COVID-19 and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 740–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Fernández, A.; Dennis, A.; Nicholls, R.; McGonigle, J.; Kelly, M.; Banerjee, R.; Banerjee, A.; Sanyal, A.J. Hepatic Steatosis, Rather Than Underlying Obesity, Increases the Risk of Infection and Hospitalization for COVID-19. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 636637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tian, A.; Zhu, H.; Chen, L.; Wen, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, P. Mendelian Randomization Analysis Reveals No Causal Relationship Between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Severe COVID-19. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1553–1560.e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clift, A.K.; Coupland, C.A.C.; Keogh, R.H.; Diaz-Ordaz, K.; Williamson, E.; Harrison, E.M.; Hayward, A.; Hemingway, H.; Horby, P.; Mehta, N.; et al. Living Risk Prediction Algorithm (QCOVID) for Risk of Hospital Admission and Mortality from Coronavirus 19 in Adults: National Derivation and Validation Cohort Study. BMJ 2020, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, A. Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Fatty Liver Disease Increases Risk of Severe Covid-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, A.; Anikhindi, S.H.; Bansal, N.; Singla, V.; Shivam, K.; Arora, A. Effect of COVID-19 on Pre-Existing Liver Disease: What Hepatologist Should Know? J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2021, 11, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marjot, T.; Eberhardt, C.S.; Boettler, T.; Belli, L.S.; Berenguer, M.; Buti, M.; Jalan, R.; Mondelli, M.U.; Moreau, R.; Shouval, D.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the Liver and on the Care of Patients with Chronic Liver Disease, Hepatobiliary Cancer, and Liver Transplantation: An Updated EASL Position Paper. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1161–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Aghemo, A.; Forner, A.; Valenti, L. COVID-19 and Liver Disease. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 1278–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Lin, F.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Xu, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection of the Liver Directly Contributes to Hepatic Impairment in Patients with COVID-19. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, F.; Zhao, J. Reply to: Correspondence Relating to “SARS-CoV-2 Infection of the Liver Directly Contributes to Hepatic Impairment in Patients with COVID-19”. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharski, A.J.; Russell, T.W.; Diamond, C.; Liu, Y.; Edmunds, J.; Funk, S.; Eggo, R.M. Early Dynamics of Transmission and Control of COVID-19: A Mathematical Modelling Study. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonzogni, A.; Previtali, G.; Seghezzi, M.; Grazia Alessio, M.; Gianatti, A.; Licini, L.; Morotti, D.; Zerbi, P.; Carsana, L.; Rossi, R.; et al. Liver Histopathology in Severe COVID 19 Respiratory Failure Is Suggestive of Vascular Alterations. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 2110–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-X.; Shao, C.; Huang, X.-J.; Sun, L.; Meng, L.-J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.-J.; Li, H.-J.; Lv, F.-D. Histopathological Features of Multiorgan Percutaneous Tissue Core Biopsy in Patients with COVID-19. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 74, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.M.; Cheng, V.C.C.; Hung, I.F.N.; Wong, M.M.L.; Chan, K.H.; Chan, K.S.; Kao, R.Y.T.; Poon, L.L.M.; Wong, C.L.P.; Guan, Y.; et al. Role of Lopinavir/Ritonavir in the Treatment of SARS: Initial Virological and Clinical Findings. Thorax 2004, 59, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Zhan, K.; Gan, L.; Bai, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, G.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, A.; He, S.; Mei, Z. Inflammatory Cytokines, T Lymphocyte Subsets, and Ritonavir Involved in Liver Injury of COVID-19 Patients. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020 51 2020, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.-J.; Ni, Z.-Y.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.-H.; Ou, C.-Q.; He, J.-X.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.-L.; Hui, D.S.C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Dong, X.; Qu, J.; Gong, F.; Han, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 99 Cases of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A Descriptive Study. Lancet (London, England) 2020, 395, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, B.; Hu, C.; Zhu, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Xiang, H.; Cheng, Z.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020, 323, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.P.; Tian, R.H.; Luo, S.; Zu, Z.Y.; Fan, B.; Wang, X.M.; Xu, K.; Wang, J.T.; Zhu, J.; Shi, J.C.; et al. Risk Factors for Adverse Clinical Outcomes with COVID-19 in China: A Multicenter, Retrospective, Observational Study. Theranostics 2020, 10, 6372–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Hu, C.; Tian, F.; Zhou, F.; Lei, Y. Epidemiological and Clinical Features of 200 Hospitalized Patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 Outside Wuhan, China: A Descriptive Study. J. Clin. Virol. Off. Publ. Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 2020, 129, 104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Lin, L.; Lin, Q.; Fang, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhuang, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, T.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of 199 Discharged Patients with COVID-19 in Fujian Province: A Multicenter Retrospective Study between January 22nd and February 27th, 2020. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0242307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hu, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhong, P.; Wen, Y.; Chen, X. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Severity of COVID-19 Outside Wuhan: A Double-Center Retrospective Cohort Study of 213 Cases in Hunan, China. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2020, 14, 1753466620963035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cao, Q.; Qin, L.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Pan, A.; Dai, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, F.; Qu, J.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Imaging Manifestations of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19):A Multi-Center Study in Wenzhou City, Zhejiang, China. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zheng, F.; Sun, D.; Ling, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, F.; Li, T.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; et al. Epidemiology and Clinical Course of COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Lei, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Liu, W. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 1663 Hospitalized Patients Infected with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Single-Center Experience. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, C.; Fei, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, L. Dynamic Changes in Liver Function Tests and Their Correlation with Illness Severity and Mortality in Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Bai, T.; Han, P.; He, Q.; Jing, M.; Xiong, X.; Zhao, X.; Quan, R.; Chen, C.; et al. Clinical Features of Patients Infected With Coronavirus Disease 2019 With Elevated Liver Biochemistries: A Multicenter, Retrospective Study. Hepatology 2021, 73, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ma, C.; Feng, X.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, L.; Han, G.; et al. Abnormal Liver Function Tests Were Associated With Adverse Clinical Outcomes: An Observational Cohort Study of 2,912 Patients With COVID-19. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 639855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Hellmuth, J.C.; Scherer, C.; Muenchhoff, M.; Mayerle, J.; Gerbes, A.L. Liver Function Test Abnormalities at Hospital Admission Are Associated with Severe Course of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Prospective Cohort Study. Gut 2021, 70, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Huang, D.; Yu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Xia, Z.; Su, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, G.; Gou, J.; Qu, J.; et al. COVID-19: Abnormal Liver Function Tests. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.; Hirsch, J.S.; Narasimhan, M.; Crawford, J.M.; McGinn, T.; Davidson, K.W.; the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium; Barnaby, D. P.; Becker, L.B.; Chelico, J.D.; et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 2020, 323, 2052–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Liu, L.; Lin, F.; Shi, J.; Han, L.; Liu, H.; He, L.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Fu, W.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of 116 Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Single-Centered, Retrospective, Observational Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.-Y.; Li, G.-X.; Chen, L.; Shu, C.; Song, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.-W.; Chen, Q.; Jin, G.-N.; Liu, T.-T.; et al. Association of Liver Abnormalities with In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with COVID-19. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedé-Ubieto, R.; Estévez-Vázquez, O.; Flores-Perojo, V.; Macías-Rodríguez, R.U.; Ruiz-Margáin, A.; Martínez-Naves, E.; Regueiro, J.R.; Ávila, M.A.; Trautwein, C.; Bañares, R.; et al. Abnormal Liver Function Test in Patients Infected with Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A Retrospective Single-Center Study from Spain. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Niu, R.; Chen, J.; Tang, Y.; Tang, W.; Xu, L.; Feng, J. Epidemiological and Clinical Features in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outside of Wuhan, China: Special Focus in Asymptomatic Patients. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-J.; Jiang, G.-G.; He, X.; Xu, K.-J.; Yang, H.; Shi, R.; Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.-Y.; Bai, L.; Tang, H.; et al. The Impact of Active Screening and Management on COVID-19 in Plateau Region of Sichuan, China. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 850736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Prichett, L.; Tao, X.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Hamilton, J.P.; Mezey, E.; Strauss, A.T.; Kim, A.; Potter, J.J.; Chen, P.-H.; et al. Abnormal Liver Chemistries as a Predictor of COVID-19 Severity and Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A. V.; Kumar, P.; Tevethia, H.V.; Premkumar, M.; Arab, J.P.; Candia, R.; Talukdar, R.; Sharma, M.; Qi, X.; Rao, P.N.; et al. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: Liver Manifestations and Outcomes in COVID-19. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 52, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasa, S.; Desai, M.; Thoguluva Chandrasekar, V.; Patel, H.K.; Kennedy, K.F.; Roesch, T.; Spadaccini, M.; Colombo, M.; Gabbiadini, R.; Artifon, E.L.A.; et al. Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Fecal Viral Shedding in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. open 2020, 3, e2011335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Liu, J.; Lu, M.; Yang, D.; Zheng, X. Liver Injury during Highly Pathogenic Human Coronavirus Infections. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2020, 40, 998–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Monterde, V.; Casas-Deza, D.; Letona-Giménez, L.; de la Llama-Celis, N.; Calmarza, P.; Sierra-Gabarda, O.; Betoré-Glaria, E.; Martínez-de Lagos, M.; Martínez-Barredo, L.; Espinosa-Pérez, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Induces a Dual Response in Liver Function Tests: Association with Mortality during Hospitalization. Biomedicines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jothimani, D.; Venugopal, R.; Abedin, M.F.; Kaliamoorthy, I.; Rela, M. COVID-19 and the Liver. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjot, T.; Webb, G.J.; Barritt, A.S.; Moon, A.M.; Stamataki, Z.; Wong, V.W.; Barnes, E. COVID-19 and Liver Disease: Mechanistic and Clinical Perspectives. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibbo, G.; Rizzo, G.E.M.; Stornello, C.; Craxì, A. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Patients with a Normal or Abnormal Liver. J. Viral Hepat. 2021, 28, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Yang, H. Cirrhosis Is an Independent Predictor for COVID-19 Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Confounding Cofactors-Controlled Data. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, e28–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonzogni, A.; Previtali, G.; Seghezzi, M.; Grazia Alessio, M.; Gianatti, A.; Licini, L.; Morotti, D.; Zerbi, P.; Carsana, L.; Rossi, R.; et al. Liver Histopathology in Severe COVID 19 Respiratory Failure Is Suggestive of Vascular Alterations. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2020, 40, 2110–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; et al. Pathological Findings of COVID-19 Associated with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Lancet. Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campogiani, L.; Iannetta, M.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Zordan, M.; Pace, P.G.; Coppola, L.; Compagno, M.; Malagnino, V.; Teti, E.; Andreoni, M.; et al. Remdesivir Influence on SARS-CoV-2 RNA Viral Load Kinetics in Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimens of COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients: A Real-Life Experience. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchynskyi, M.; Kamyshna, I.; Lyubomirskaya, K.; Moshynets, O.; Kobyliak, N.; Oksenych, V.; Kamyshnyi, A. Efficacy of Interferon Alpha for the Treatment of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-García, P.; Rodríguez, R.R.; Barata, C.; Gómez-Canela, C. Presence and Toxicity of Drugs Used to Treat SARS-CoV-2 in Llobregat River, Catalonia, Spain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Karataş, Y.; Rahman, H. Anti COVID-19 Drugs: Need for More Clinical Evidence and Global Action. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 2575–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferron, P.-J.; Gicquel, T.; Mégarbane, B.; Clément, B.; Fromenty, B. Treatments in Covid-19 Patients with Pre-Existing Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: A Potential Threat for Drug-Induced Liver Injury? Biochimie 2020, 179, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardo, A.D.; Schneeweiss-Gleixner, M.; Bakail, M.; Dixon, E.D.; Lax, S.F.; Trauner, M. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Liver Injury in COVID-19. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, T.C.-F.; Lui, G.C.-Y.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Chow, V.C.-Y.; Ho, T.H.-Y.; Li, T.C.-M.; Tse, Y.-K.; Hui, D.S.-C.; Chan, H.L.-Y.; Wong, G.L.-H. Liver Injury Is Independently Associated with Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 70, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, A.D.; Schneeweiss-Gleixner, M.; Bakail, M.; Dixon, E.D.; Lax, S.F.; Trauner, M. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Liver Injury in COVID-19; Wiley-Blackwell, 2021; Vol. 41, pp. 20–32; 2021, 41, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Beyerstedt, S.; Casaro, E.B.; Rangel, É.B. COVID-19: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) Expression and Tissue Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 40, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ni, C.; Gao, R.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wei, J.; Lv, T.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, W.; et al. Recapitulation of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Cholangiocyte Damage with Human Liver Ductal Organoids. Protein Cell 2020, 11, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Han, Y.; Nilsson-Payant, B.E.; Gupta, V.; Wang, P.; Duan, X.; Tang, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Jaffré, F.; et al. A Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Platform to Study SARS-CoV-2 Tropism and Model Virus Infection in Human Cells and Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 125–136.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Lin, F.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Xu, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection of the Liver Directly Contributes to Hepatic Impairment in Patients with COVID-19. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangash, M.N.; Patel, J.M.; Parekh, D.; Murphy, N.; Brown, R.M.; Elsharkawy, A.M.; Mehta, G.; Armstrong, M.J.; Neil, D. SARS-CoV-2: Is the Liver Merely a Bystander to Severe Disease? J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 995–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijnikman, A.S.; Bruin, S.; Groen, A.K.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Herrema, H. Increased Expression of Key SARS-CoV-2 Entry Points in Multiple Tissues in Individuals with NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 748–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, F.J.; Rajapaksha, H.; Shackel, N.; Herath, C.B. ACE2: From Protection of Liver Disease to Propagation of COVID-19. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 2020, 134, 3137–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paizis, G.; Tikellis, C.; Cooper, M.E.; Schembri, J.M.; Lew, R.A.; Smith, A.I.; Shaw, T.; Warner, F.J.; Zuilli, A.; Burrell, L.M.; et al. Chronic Liver Injury in Rats and Humans Upregulates the Novel Enzyme Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2. Gut 2005, 54, 1790–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondevila, M.F.; Mercado-Gómez, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Gonzalez-Rellan, M.J.; Iruzubieta, P.; Valentí, V.; Escalada, J.; Schwaninger, M.; Prevot, V.; Dieguez, C.; et al. Obese Patients with NASH Have Increased Hepatic Expression of SARS-CoV-2 Critical Entry Points. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biquard, L.; Valla, D.; Rautou, P.-E. No Evidence for an Increased Liver Uptake of SARS-CoV-2 in Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 717–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenger, K.J.P.; Bolzon, C.M.; Li, C.; Allard, J.P. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Obesity: The Role of the Gut Bacteria. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.Y.; Leung, W.K.; Cheung, K.S. Association between Gut Microbiota and SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Vaccine Immunogenicity. Microorg. 2023, Vol. 11, Page 452 2023, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, M.; Marchianò, S.; Carino, A.; Di Giorgio, C.; Santucci, L.; Distrutti, E.; Fiorucci, S. Bile Acids Activated Receptors in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, T.; Gall, S.D. Le; Sweidan, A.; Tamanai-shacoori, Z.; Jolivet-gougeon, A.; Loréal, O.; Bousarghin, L. Next-generation Probiotics and Their Metabolites in Covid-19. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutz, M.R.; Dylla, N.P.; Pearson, S.D.; Lecompte-Osorio, P.; Nayak, R.; Khalid, M.; Adler, E.; Boissiere, J.; Lin, H.; Leiter, W.; et al. Immunomodulatory Fecal Metabolites Are Associated with Mortality in COVID-19 Patients with Respiratory Failure. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.C.Y.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Li, A.Y.L.; Zhan, H.; Wan, Y.; Chung, A.C.K.; Cheung, C.P.; Chen, N.; et al. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 944–955.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Gao, H.; Lv, L.; Guo, F.; Zhang, X.; Luo, R.; Huang, C.; et al. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 or H1N1 Influenza. Clin. Infect. Dis. an Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2020, 71, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, Y.K.; Zuo, T.; Lui, G.C.-Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Li, A.Y.; Chung, A.C.; Cheung, C.P.; Tso, E.Y.; Fung, K.S.; et al. Gut Microbiota Composition Reflects Disease Severity and Dysfunctional Immune Responses in Patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 70, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhuang, Z.-J.; Bian, D.-X.; Ma, X.-J.; Xun, Y.-H.; Yang, W.-J.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.-L.; Jia, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Toll-like Receptor-4 Signalling in the Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Induced by High-Fat and High-Fructose Diet in Mice. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2014, 41, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, S.; Tovoli, F.; Napoli, L.; Serio, I.; Ferri, S.; Bolondi, L. Current Guidelines for the Management of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review with Comparative Analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 3361–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, C.; Ronaghan, N.; Zaheer, R.; Dicay, M.; Le, T.; MacNaughton, W.K.; Surrette, M.G.; Swain, M.G. Probiotics Improve Inflammation-Associated Sickness Behavior by Altering Communication between the Peripheral Immune System and the Brain. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 10821–10830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.W.F.; Houben, T.; Katiraei, S.; Dijk, W.; Boutens, L.; van der Bolt, N.; Wang, Z.; Brown, J.M.; Hazen, S.L.; Mandard, S.; et al. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota Impacts Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Potential Role for Bile Acids. J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Saha, P.K.; Chan, L.; Moore, D.D. Farnesoid X Receptor Is Essential for Normal Glucose Homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 2006, 116, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, A.; Canbay, A. Why Bile Acids Are So Important in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Progression. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.T.; Campos, P.C.; Pereira, G. de S.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Splitter, G.; Oliveira, S.C. TLR9 Is Required for MAPK/NF-ΚB Activation but Does Not Cooperate with TLR2 or TLR6 to Induce Host Resistance to Brucella Abortus. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016, 99, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, A.; Karasudani, Y.; Otsuka, Y.; Hasegawa, M.; Inohara, N.; Fujimoto, Y.; Fukase, K. Synthesis of Diaminopimelic Acid Containing Peptidoglycan Fragments and Tracheal Cytotoxin (TCT) and Investigation of Their Biological Functions. Chemistry 2008, 14, 10318–10330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividad, J.M.; Agus, A.; Planchais, J.; Lamas, B.; Jarry, A.C.; Martin, R.; Michel, M.-L.; Chong-Nguyen, C.; Roussel, R.; Straube, M.; et al. Impaired Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Ligand Production by the Gut Microbiota Is a Key Factor in Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Vigliotti, C.; Witjes, J.; Le, P.; Holleboom, A.G.; Verheij, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Clément, K. Gut Microbiota and Human NAFLD: Disentangling Microbial Signatures from Metabolic Disorders. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlano, R.; Sivakumar, M.; Mullish, B.H.; Manousou, P. Gut Microbiota-A Future Therapeutic Target for People with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, R.Z.; Barbalho, S.M.; Sloan, K.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Gonzaga, H.F.; Grippa, P.C.; Zutin, T.L.M.; Girio, R.J.S.; Repetti, C.S.F.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; et al. The Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics in Non-Alcoholic Fat Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Seguritan, V.; Li, W.; Long, T.; Klitgord, N.; Bhatt, A.; Dulai, P.S.; Caussy, C.; Bettencourt, R.; Highlander, S.K.; et al. Gut Microbiome-Based Metagenomic Signature for Non-Invasive Detection of Advanced Fibrosis in Human Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1054–1062.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Dai, T.; Qin, Z.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, L. Alterations in Microbiota of Patients with COVID-19: Potential Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SeyedAlinaghi, S.; Afzalian, A.; Pashaei, Z.; Varshochi, S.; Karimi, A.; Mojdeganlou, H.; Mojdeganlou, P.; Razi, A.; Ghanadinezhad, F.; Shojaei, A.; et al. Gut Microbiota and COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Heal. Sci. reports 2023, 6, e1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Kobyliak, N.; Kamyshnyi, A. Gut Microbiota in Patients with COVID-19 and Type 2 Diabetes: A Culture-Based Method. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1142578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Kang, S.G.; Jannasch, A.H.; Cooper, B.; Patterson, J.; Kim, C.H. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Induce Both Effector and Regulatory T Cells by Suppression of Histone Deacetylases and Regulation of the MTOR-S6K Pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gang, J.; Wang, H.; Xue, X.; Zhang, S. Microbiota and COVID-19: Long-Term and Complex Influencing Factors. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.Y.; Leung, W.K.; Cheung, K.S. Association between Gut Microbiota and SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Vaccine Immunogenicity. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iruzubieta, P.; Medina, J.M.; Fernández-López, R.; Crespo, J.; de la Cruz, F. A Role for Gut Microbiome Fermentative Pathways in Fatty Liver Disease Progression. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Q.; El-Serag, H.B.; Loomba, R. Global Epidemiology of NAFLD-Related HCC: Trends, Predictions, Risk Factors and Prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamata, Y.; Fujii, R.; Hosoya, M.; Harada, M.; Yoshida, H.; Miwa, M.; Fukusumi, S.; Habata, Y.; Itoh, T.; Shintani, Y.; et al. A G Protein-Coupled Receptor Responsive to Bile Acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 9435–9440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencarelli, A.; Renga, B.; Migliorati, M.; Cipriani, S.; Distrutti, E.; Santucci, L.; Fiorucci, S. The Bile Acid Sensor Farnesoid X Receptor Is a Modulator of Liver Immunity in a Rodent Model of Acute Hepatitis. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 6657–6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavassori, P.; Mencarelli, A.; Renga, B.; Distrutti, E.; Fiorucci, S. The Bile Acid Receptor FXR Is a Modulator of Intestinal Innate Immunity. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 6251–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, M.; Carino, A.; Fiorucci, C.; Marchianò, S.; Di Giorgio, C.; Bordoni, M.; Roselli, R.; Baldoni, M.; Distrutti, E.; Zampella, A.; et al. The Bile Acid Receptor GPBAR1 Modulates CCL2/CCR2 Signaling at the Liver Sinusoidal/Macrophage Interface and Reverses Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Toxicity. J. Immunol. 2020, 204, 2535–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorucci, S.; Carino, A.; Baldoni, M.; Santucci, L.; Costanzi, E.; Graziosi, L.; Distrutti, E.; Biagioli, M. Bile Acid Signaling in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 674–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorucci, S.; Baldoni, M.; Ricci, P.; Zampella, A.; Distrutti, E.; Biagioli, M. Bile Acid-Activated Receptors and the Regulation of Macrophages Function in Metabolic Disorders. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 53, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorucci, S.; Distrutti, E.; Carino, A.; Zampella, A.; Biagioli, M. Bile Acids and Their Receptors in Metabolic Disorders. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 82, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadaleta, R.M.; Oldenburg, B.; Willemsen, E.C.L.; Spit, M.; Murzilli, S.; Salvatore, L.; Klomp, L.W.J.; Siersema, P.D.; van Erpecum, K.J.; van Mil, S.W.C. Activation of Bile Salt Nuclear Receptor FXR Is Repressed by Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Activating NF-ΚB Signaling in the Intestine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massafra, V.; Ijssennagger, N.; Plantinga, M.; Milona, A.; Ramos Pittol, J.M.; Boes, M.; van Mil, S.W.C. Splenic Dendritic Cell Involvement in FXR-Mediated Amelioration of DSS Colitis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, R.; Takayama, T.; Yoneno, K.; Kamada, N.; Kitazume, M.T.; Higuchi, H.; Matsuoka, K.; Watanabe, M.; Itoh, H.; Kanai, T.; et al. Bile Acids Induce Monocyte Differentiation toward Interleukin-12 Hypo-Producing Dendritic Cells via a TGR5-Dependent Pathway. Immunology 2012, 136, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, M.; Carino, A.; Fiorucci, C.; Marchianò, S.; Di Giorgio, C.; Roselli, R.; Magro, M.; Distrutti, E.; Bereshchenko, O.; Scarpelli, P.; et al. GPBAR1 Functions as Gatekeeper for Liver NKT Cells and Provides Counterregulatory Signals in Mouse Models of Immune-Mediated Hepatitis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 8, 447–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; McKenney, P.T.; Konstantinovsky, D.; Isaeva, O.I.; Schizas, M.; Verter, J.; Mai, C.; Jin, W.-B.; Guo, C.-J.; Violante, S.; et al. Bacterial Metabolism of Bile Acids Promotes Generation of Peripheral Regulatory T Cells. Nature 2020, 581, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Lu, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, T.; Xia, C.; Zhang, T.; Gou, X.-J.; et al. The Role of Gut Microbiota-Bile Acids Axis in the Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 908011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.; Christodoulatos, G.S.; Karampela, I.; Tsilingiris, D.; Magkos, F.; Stratigou, T.; Kounatidis, D.; Dalamaga, M. Understanding the Role of the Gut Microbiome and Microbial Metabolites in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Current Evidence and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Refferences | Number of studies/ included patients | Results | Advantages | Limitations |

| Hegyi et al., 2021 [72] | 9 studies (8202 cases) | A 2.6-fold increased risk of severe COVID-19 is associated with MAFLD, while NAFLD is linked to a five-fold greater susceptibility; however, there was no discernable difference in hospital mortality between COVID-19 patients with MAFLD or NAFLD. | The study was executed with meticulous attention to methodological rigor. | Study involves only nine articles Most of the articles were published in Asian countries Data came mostly from retrospective studies; In-hospital mortality was not analyzed; High risk of bias in included articles. |

| Singh et al., 2021 [73] | 14 studies (1851 cases) | In patients with COVID-19 infection, the presence of NAFLD increased the risk of severe disease and ICU admission; however, there was no discernable difference in mortality between COVID-19 patients with or without NAFLD. | The study's findings were adjusted for several possible confounding factors to provide a more accurate assessment of the relationship between the variables of interest. | The study involved only six articles; There was a lack of a robust and consistent definition of NAFLD in selected articles; Major covariates, such as age, sex, race, and co-morbidities, were adjusted in selected studies. There was a restricted scope for a robust subgroup analysis due to a fewer number of included studies. |

| Tao et al., 2021 [77] | 7 studies (2141 cases) | The presence of MAFLD was linked to an elevated risk of severe COVID-19(odds ratios: 1.80, 95% CI: 1.53-2.13, P<0.00001), but not to an increased likelihood of death due to COVID-19 infection. | The study's robustness was further substantiated by a sensitivity analysis, which validated the initial findings. The inclusion of studies from both Chinese and foreign countries bolstered the generalizability of the results and improved the external validity of the study. | Insufficient representation of studies, notably those from China, limited the robustness of the meta-analysis. The majority of studies included in this analysis were cross-sectional, which may compromise their reliability as compared to more robust cohort studies. The etiology of the variation in the pooled prevalence could not be determined. |

| Pan et al., 2020 [74] | 6 studies (1,293 cases) | The study demonstrated that MAFLD is independently associated with an elevated risk of severe COVID-19 and a higher prevalence of COVID-19 in individuals with MAFLD compared to the general population. | The heterogeneity observed in the studies was reasonably acceptable, thereby ensuring the reliability of the outcomes. | The included studies were limited in number and conducted exclusively within China. There were only six studies included in the final analysis; Only one study had a subgroup analysis; The studies included in the analysis were mainly cross-sectional and case-control studies, which are generally regarded as less robust than prospective cohort studies. |

| Wang et al., 2022 [75] | 18 studies (22,056 cases) | The presence of NAFLD was found to be independently associated with severe COVID-19, particularly in younger patients compared to older ones. | The overall odds ratio was derived by considering the effects sizes adjusted for risk factors, mainly age, sex, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. A sensitivity analysis was conducted (it showed no significant impact on the overall results). | There is no statement regarding protocol and registration Authors used free-text only in their search strategy without including the MeSH approach; Detailed flow diagram that would illustrate the study selection process, sample size, PICOS, follow-up period, and citations of the included studies was not provided. The authors did not report the odds ratio (OR) in a clear and specific manner. There is no corresponding analysis of the risk of bias; No full paper. |

| Li et al., 2022 [82] | 3 genome-wide association study (8267 cases) | The available evidence does not suggest a direct cause-and-effect association between NAFLD and the severity of COVID-19. The correlation between NAFLD and COVID-19 reported in prior studies is likely explained by the interrelatedness of NAFLD and obesity. The impact of comorbid factors associated with NAFLD on severe COVID-19 is largely attributed to body mass index, waist circumference, and hip circumference, based on evidence of causality. | Mendelian Randomization analysis provides a possibility to examine the causal relationship between NAFLD and severe COVID-19; Using COVID-19 genome-wide association study summary statistics. | The findings of the study cannot be generalized to evaluate the relationship between the severity of NAFLD and the risk of severe COVID-19, as the analysis only considered the presence of liver fat as the exposure variable. One of the selected research studies utilized one-sample-based MR analysis, which may be susceptible to bias [79]; The present findings may be subject to limitations arising from the small size of the sample population, as well as potential confounding clinical covariates that remain unidentified. These results somewhat contradict the observational studies of the same authors in other studies [7,83]; |

| Hayat et al., 2022 [76] | 16 studies (11484 cases) | The occurrence of COVID-19 was found to be 0.29 among individuals with MAFLD. A heightened likelihood of COVID-19 severity and higher ICU admission rate were observed among patients with MAFLD. The correlation between MAFLD and COVID-19 mortality did not achieve statistical significance. | This study represents a novel contribution to the field, as it is the first to comprehensively investigate COVID-19-related mortality in a large and diverse cohort of MAFLD patients. Additionally, the study uniquely examines both the prevalence of MAFLD and the associated COVID-19 outcomes in a broad and extensive MAFLD population. | The respective studies included in this meta-analysis did not include a robust and consistent definition of the severity of COVID-19. Some included studies do not account for confounding factors such as age, race, gender and certain other co-morbidities. There were multiple comorbidities in the study population, making it difficult to dissect the contribution of each comorbidity to COVID-19 outcomes.; Fewer studies were included in the subgroup analysis of the effect of MAFLD on the COVID-19 ICU entrance and mortality rate making it difficult to analyze the publication bias (fewer than ten articles). |

| Study | Region | Sample size (n) | Elevated ALT | Elevated AST | Elevated ALP | Elevated GGT | Elevated TBIL | Elevated LDH | Reduced Albumin |

| Guan et al., 2020 [95] | Nationwide, China | 722-757 | 158/741 (21.3%) | 168/757 (22.2%) | N/A | N/A | 76/722 (10.5%) | 277/675 (41,0%) | N/A |

| Xu et al., 2020 [98] | Hubei, Zhejiang, Anhui, Shandong, Jiangsu, China | 430-581 | 95/504 (19%) | 82/460 (18%) | N/A | N/A | 60/430 (14%) | 171/383 (45%) | 260/581 (45%) |

| Yang et al., 2020 [99] |

Hubei Province, China |

200 | 44 (22 %) | 74 (37 %) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 74/189 (38.5 %) | 144 (72%) |

| Cai et al., 2020 [109] | Shenzhen, China | 417 | 54 (12.9%) | 76 (18.2%) | 101 (24.2%) | 68 (16.3%) | 99 (23.7%) | N/A | N/A |

| Richardson et al., 2020 [110] | New York, America | 5700 | 2176 (39.0%) | 3263 (58.4%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wang et al., 2020 [100] | Fujian Province, China | 199 | 22 (11.1%) | 47 (23.6%) | N/A | N/A | 34 (17.%1) | 65 (32.7%) | 26 (13.1%) |

| Hu et al., 2020 [101] | Hunan Province, China | 213 | 33 (15.5%) | 27 (12.7%) | N/A | N/A | 44 (20.7%) | 27 (12.7%) | N/A |

| Xiong et al., 2020 [111] | Wuhan, China | 116 | 23 (19.8) | 46 (39.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 69 (59.5%) | N/A |

| Yang et al., 2020 [102] | Wenzhou, China | 149 | 18 (12.08%) | 27 (18.12%) | N/A | N/A | 4 (2.68%) | 45 (30.20%) | 9 (6.04%) |

| Yu et al., 2020 [104] |

Wuhan, China |

1443-1445 | 298/1445 (20.6%) | 303/1445 (21.0%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1110/1444 (76.9%) | 723/1443 (50.1%) |

| Shen et al., 2020 [103] |

Shanghai, China |

325 | 53 (16.3%) | 54 (16.6%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 125 (38.5%) | N/A |

| Zhang et al., 2021 [5] | Wuhan, China | 267 | 49 (18.4%) | 76 (28.5%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Xu et al., 2021 [105] | Shanghai, China | 1003 | 295 (29.4%) | 176 (17.5%) | 26 (2.6%) | 134 (13.4%) | 40 (4.0%) | N/A | 307 (30.6%) |

| Ding et al., 2021 [112] | Wuhan, China | 2073 | 501 (24.2%) | 545 (26.3%) | 165 (8.0%) | 443 (21.4%) | 71 (3.4%) | N/A | N/A |

| Fu et al., 2021 [106] | Wuhan, China | 482 | 96 (19.9%) | 98 (20.3%) | N/A | N/A | 23 (4.8%) | N/A | 199 (41.3%) |

| Lv et al., 2021 [107] | Wuhan, China | 2912 | 662 (22.7%) | 221 (7.5%) | 135 (4.6%) | 536 (18.4%) | 52 (1.8%) | N/A | 2086 (71.6%) |

| Benedé-Ubieto et al., 2021 [113] | Madrid, Spain | 799 | 204 (25.73%) | 446 (49.17%) | 186 (24.21%) | 270 (34.62%) | N/A | 400 (55.84%) | N/A |

| Weber et al., 2021 [108] | Munich, Germany | 217 | 59 (27.2%) | 91 (41.9%) | 22 (10.1%) | 80 (36.9%) | 10 (4.6%) | N/A | 71 (32.7%) |

| Liu et al., 2021 [114] | Changsha, China. | 209 | 20 (9,6%) | 24 (11,5%) | N/A | N/A | 179 (85,6%) | 30 (14,4%) | N/A |

| Lu et al., 2022 [115] | Sichuan, China | 70 | 32 (45.7%) | 22 (31.4%) | 12 (17.1%) | 32 (45.7%) | 32 (45.7%) | 40/69 (58,0%) | N/A |

| Krishnan et al., 2022 [116] |

Baltimore, MD, United States |

3830 | 2698 (70.4%) | 1637 (44.4%) | 611 (16.1%) | N/A | 221 (5.9%) | N/A | N/A |

| MAFLD | COVID-19 | |||||

| Gut metabolites and inflammatory factors | Gut microbiome changes | Overlap | Gut microbiome changes | Gut metabolites and inflammatory factors | ||

| ↑Endotoxins [153,154]: activating the TLR4; ↑TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12; hepatocyte injury; oxidative stress; hepatocyte apoptosis. ↑Lipopolysaccharides [155]: Activating of TLR4; ↑IL-6,IL-1β, serum LBP TNF-α, chemokines; ↓↑Bile acid metabolites[147,156,157,158]: ↑IL-6,IL-8, IL-12,IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-y; ↓ IL-10. ↑Bacterial DNAs [159]: activating the TLR9; activating of NF-κB/MAPK; macrophages, NK cells, B cells, dendritic cells; ↑IL-12 and TNF-α. ↑Peptidoglycan [160]: activating of NF-κB/MAPK, NOD1, NOD2; ↑pro-inflammatory cytokines. ↓Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) [161]: ↑TNF-α, MCP-1 та IL-1β. |

↓Alistipes ↓Anaerosporobacter ↓Coprobacter ↓Haemophilus ↓Moryella ↓Oscillobacter ↓Pseudobutyrivibrio ↓Subdoligramulum ↓Methanobrevibacter ↓Oscillospira ↓Phascolarctobacterium [162] ↓Rhuminococcaceae ↓Rikenellaceae ↓Prevotella ↓Prevotellaceae ↓Clostridiaceae ↓Clostridium [163] |

↑Acidaminococcus ↑Akkermansia ↑Allisonella ↑Anaerococcus ↑Bradyrhizobium ↑Dorea ↑Eggerthella ↑Escherichia ↑Flavonifractor incertae sedis ↑Parabacteroides ↑Peptoniphilus ↑Porphyromonas ↑Robinsonella ↑Ruminococcus ↑Shigella [162] ↑Proteobacteria ↑Enterobacteria [164] ↑Subdoligranulum ↑Blautia sp ↑Firmicutes ↑Roseburia ↑Oscillibacter [165] ↑Fusobacteria [163] |

↑Bacteroides , ↓Bifidobacterium ↓Eubacterium , ↓Faecalibacterium [166]-COVID-19 [162]-MAFLD ↓Coprococcus [150]- COVID-19 [162]- MAFLD ↑Streptococcus [151]- COVID-19 [165]- MAFLD ↑Enterobacteriaceae [166]- COVID-19 [163]- MAFLD ↓Lactobacillus [167]- COVID-19 [162]- MAFLD |

↓Roseburia, ↓Lachnospiraceae ↓Bacteroidetes ↓Blautia wexlerae, [166] ↓Dorea ↓Ruminococus [150] ↓Ruminococcus bromii [167] |

↑Enterobacteriaceae ↑Enterococcus ↑Actinomyces ↑Clostridium [166] ↑Rothia ↑Veillonella [151] ↑Blautia spp ↑Campylobacter ↑Corynebacterium ↑Enterococcaceae ↑Pseudomonas ↑Staphylococcus [167] ↑Klebsiella [168] |

↓SCFA [169,170]: ↓effector T cells; ↓IL-17, IFN-γ, and/or IL-10. ↑Lipopolysaccharides [155,171]: Activating of TLR4; ↑IL-6,IL-1β, serum LBP TNF-α, chemokines; ↓↑Bile acid metabolites [147,149,156,157,158,171] inhibit NF-Κb ↑IL-6,IL-8, IL-12,IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-y; ↓ IL-10; progression of respiratory failure [149]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).