Submitted:

28 March 2023

Posted:

30 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

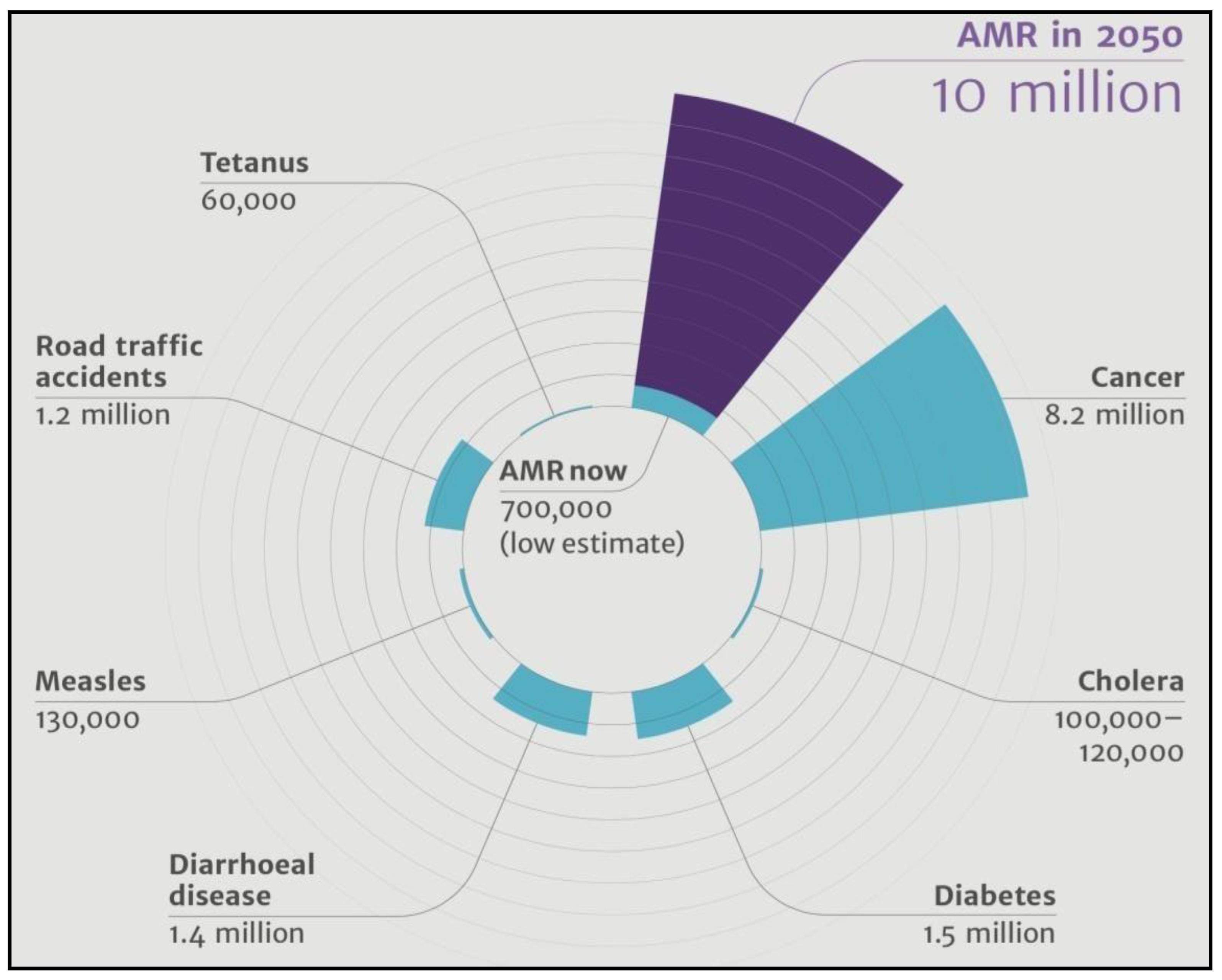

Introduction and Literature Review

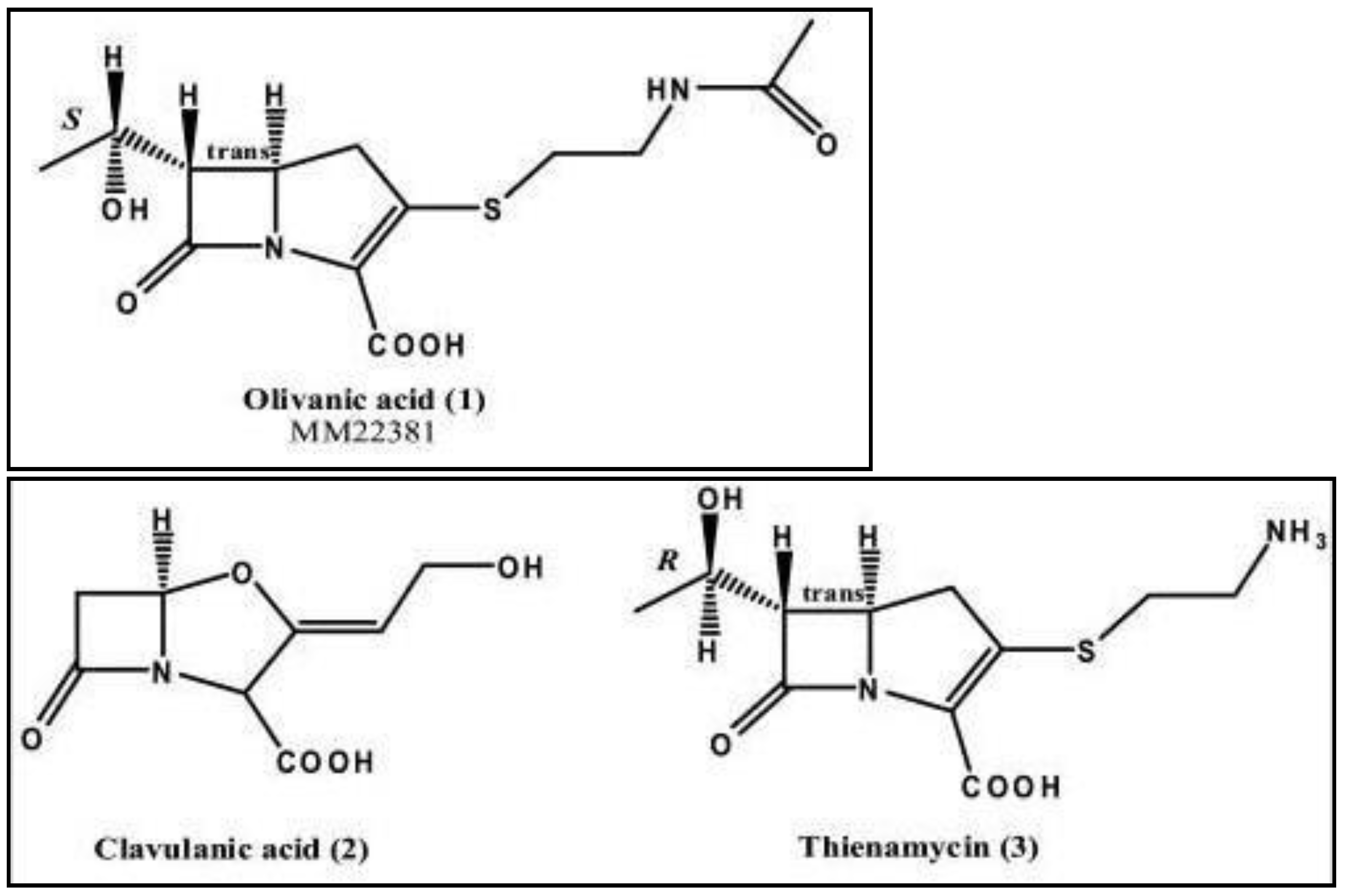

- (i)

- Clavulanic acid from Streptomyces clavuligerus, which was the first clinically available inhibitor,

- (ii)

- Thienamycin from Streptomyces cattleya, which became the parent compound for all carbapenems.

- (i)

- imipenem and doripenem are more potent than meropenem against Acinetobacter baumanii11,

- (ii)

- low Minimum inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of doripenem than imipenem and doripenem against A.baumanii and P.aeruginosa, and doripenem are least susceptible to hydrolysis by carbapenemases12,

- (iii)

- limited spectrum of ertapenem against P.aeruginosa11,

- (iv)

- MDR Mycobacterium tuberculosis can be treated with meropenem in combination with clavulanic acid13.

Materials and Methods

Downloading protein genome sequence from NCBI

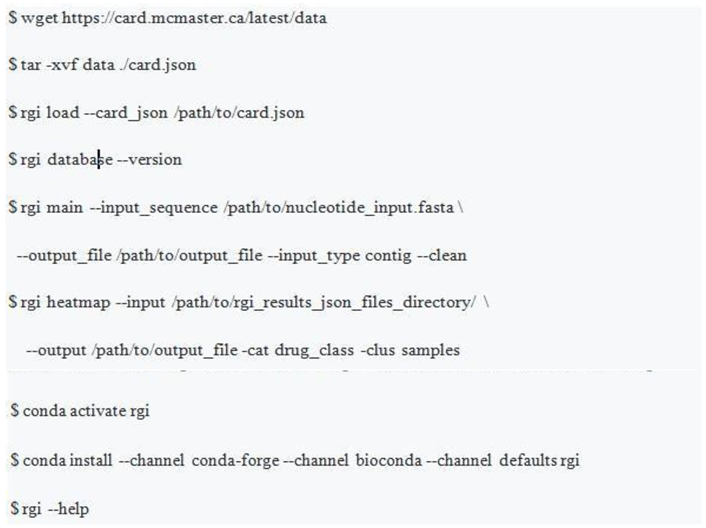

Identification of AMR genes

Co-occurrence study

Genomic context study

Phylogenetic analysis

PLSDB

MLST

Results

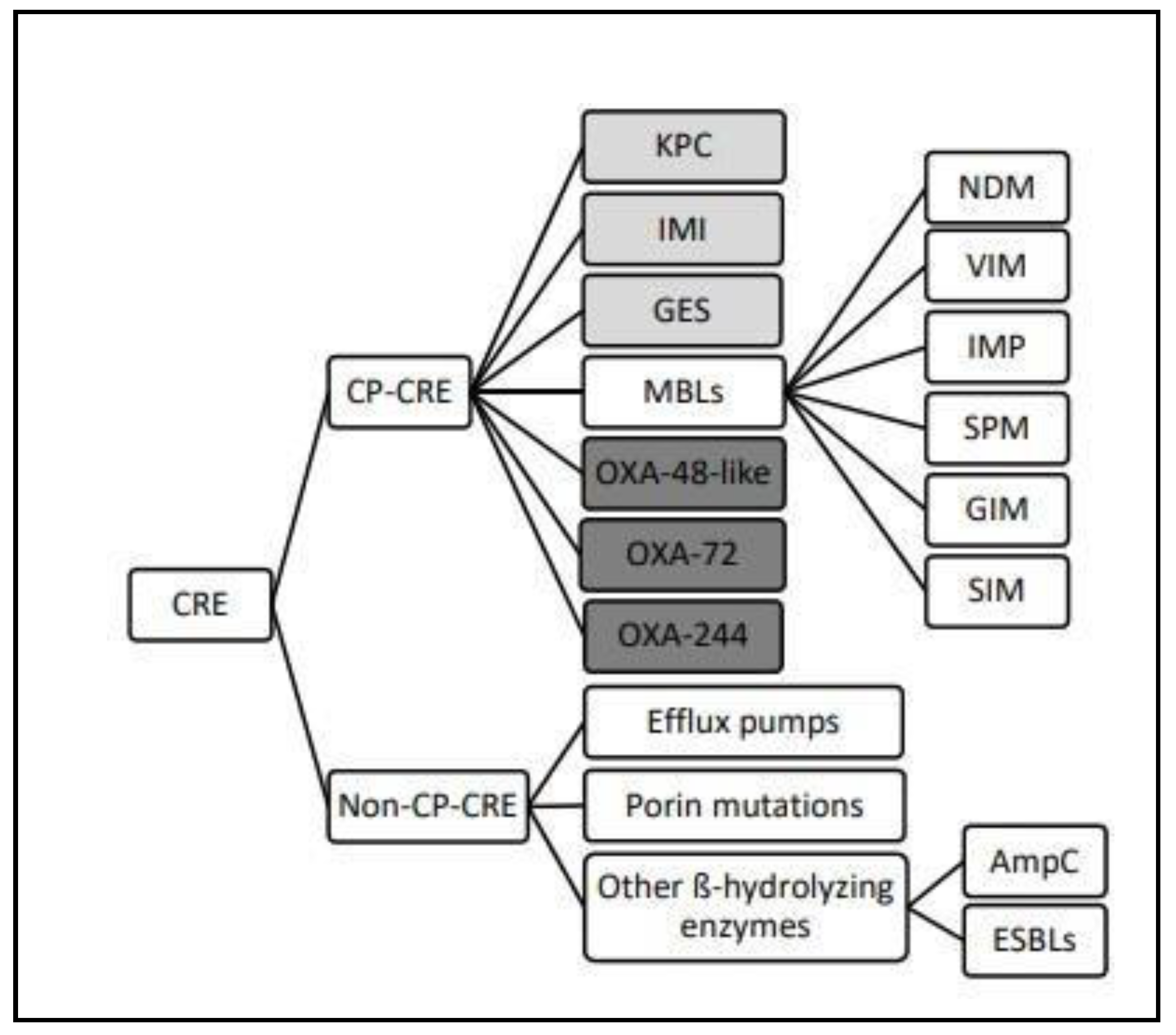

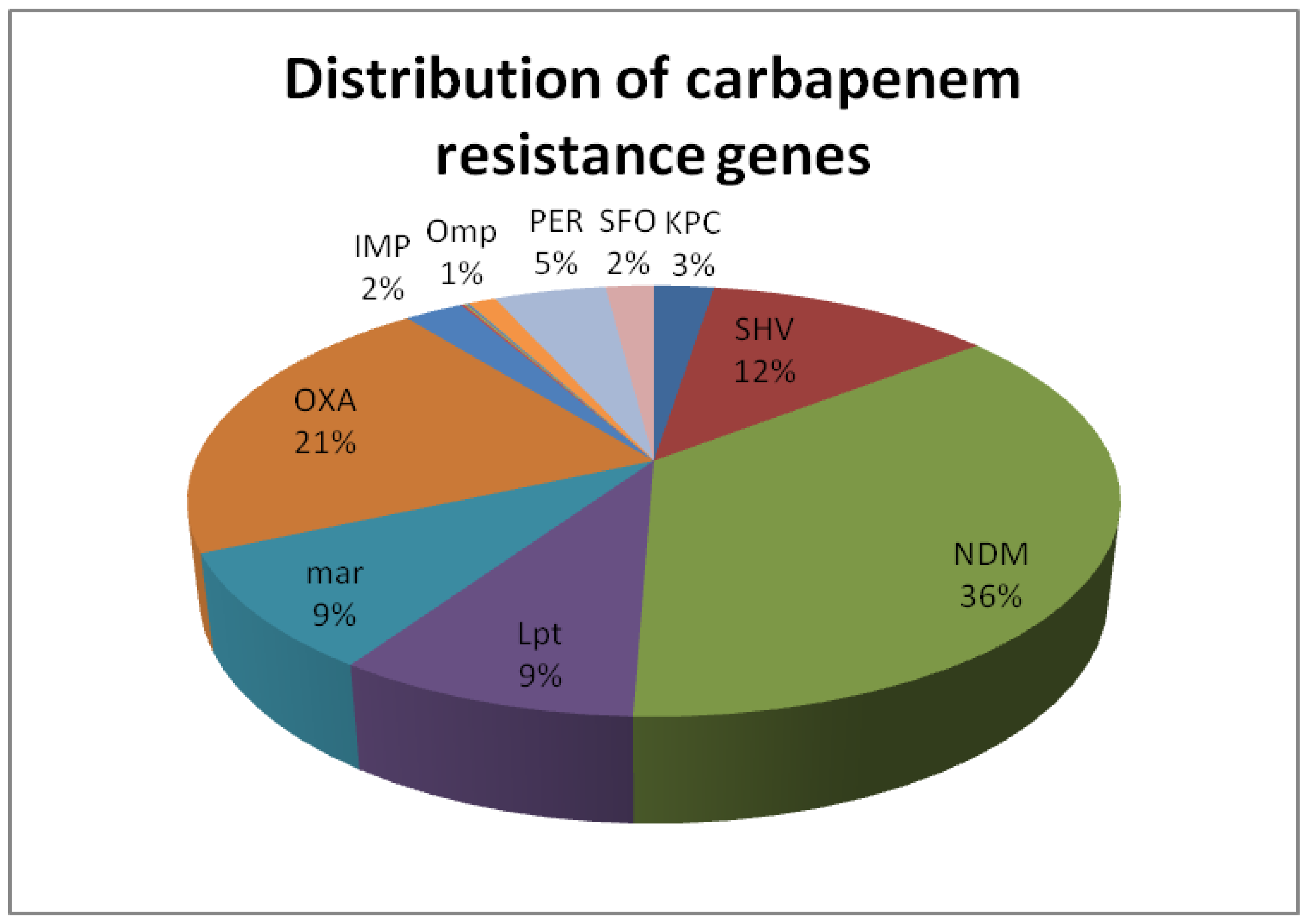

Carbapenem-resistance gene detection

Co-occurrence analysis

Between drug classes

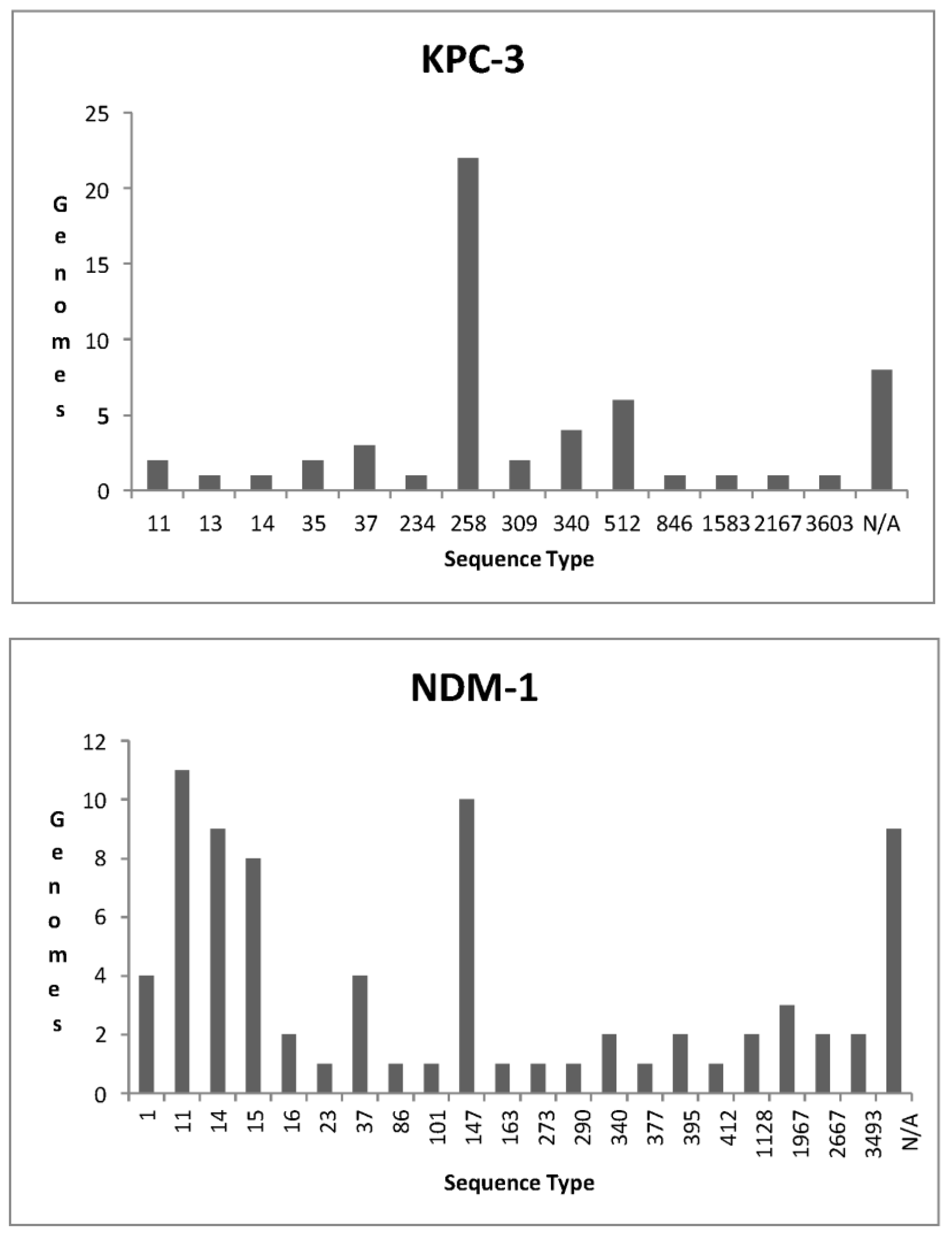

KPC

NDM

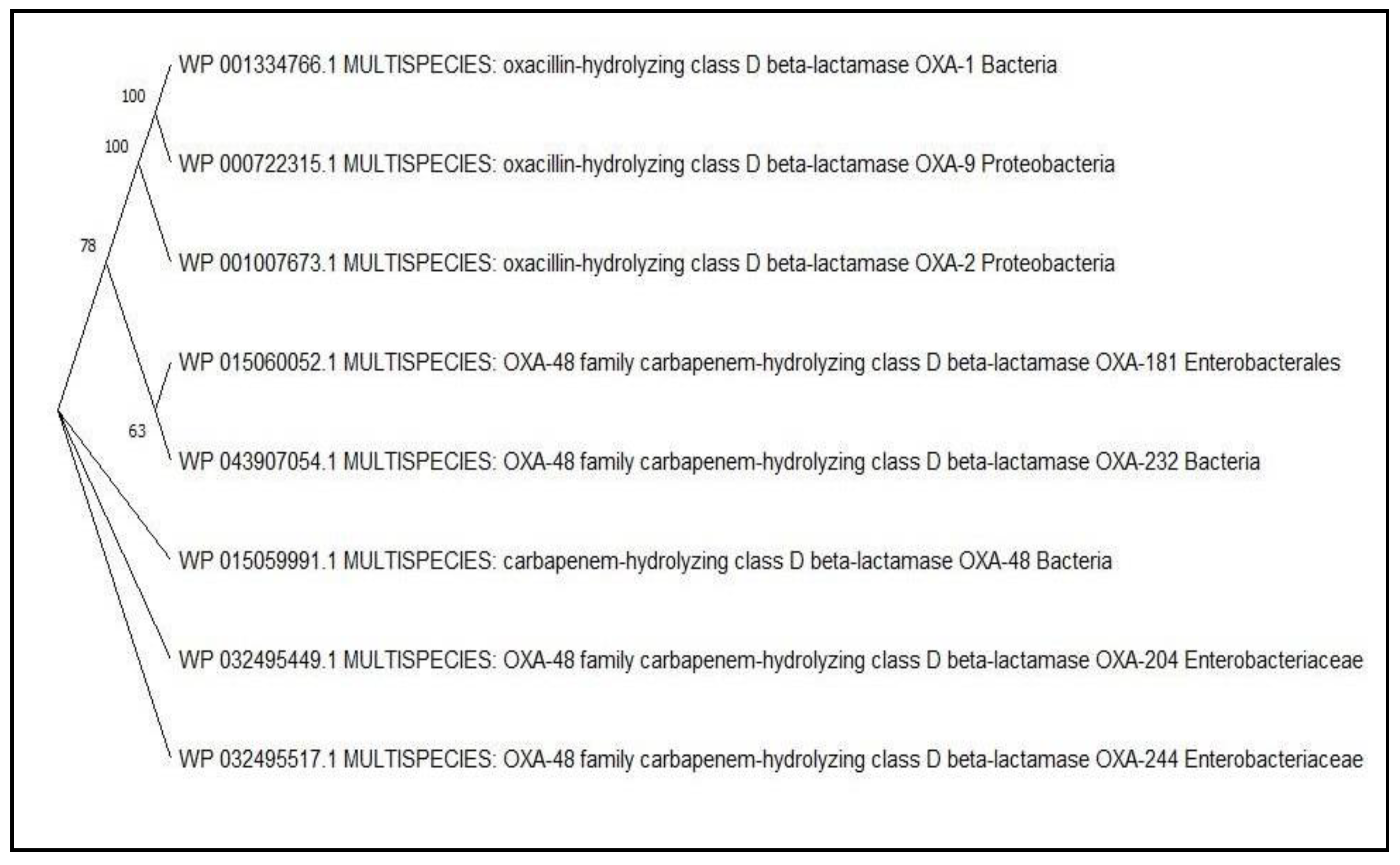

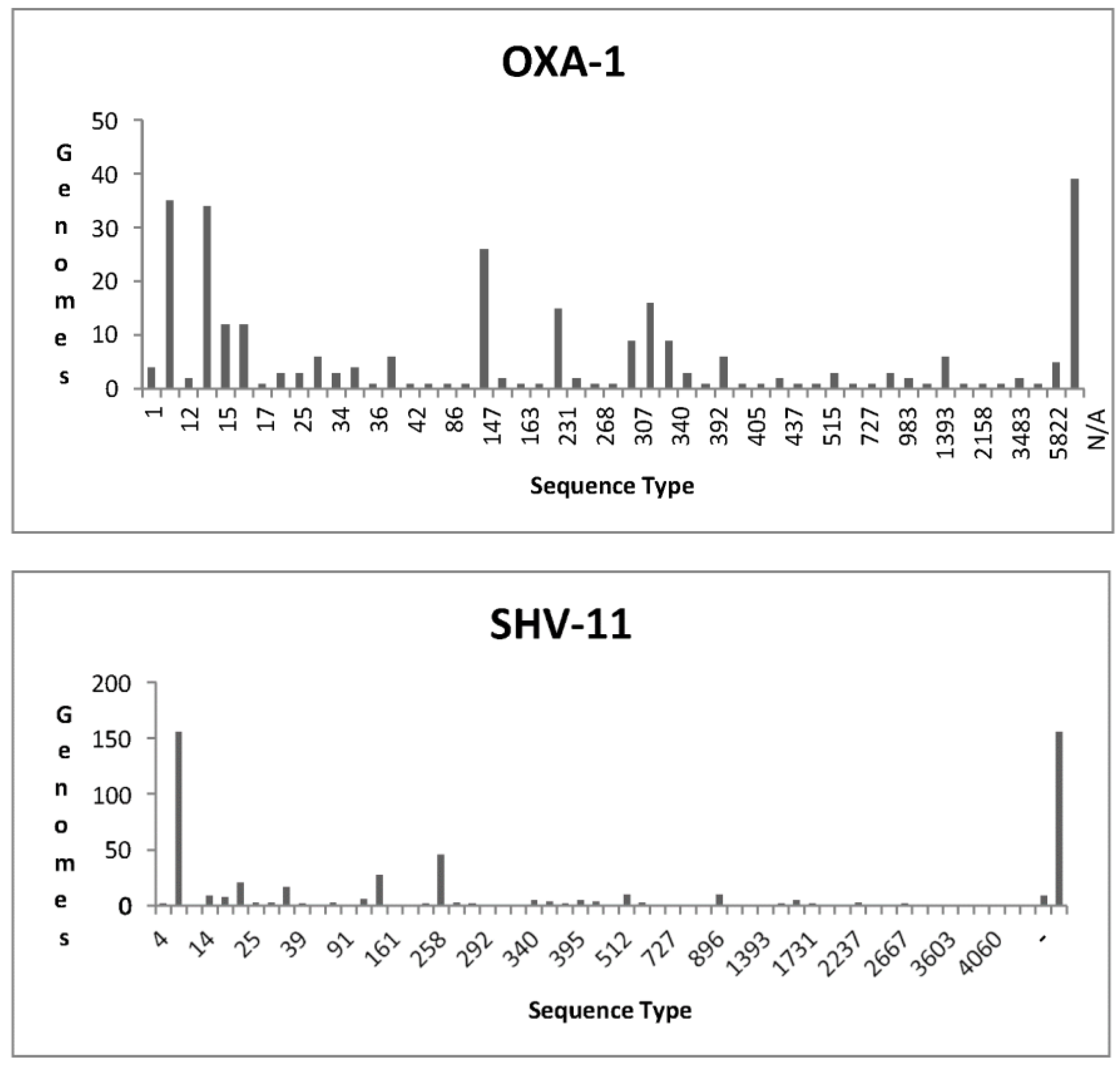

OXA

Within carbapenem drug class

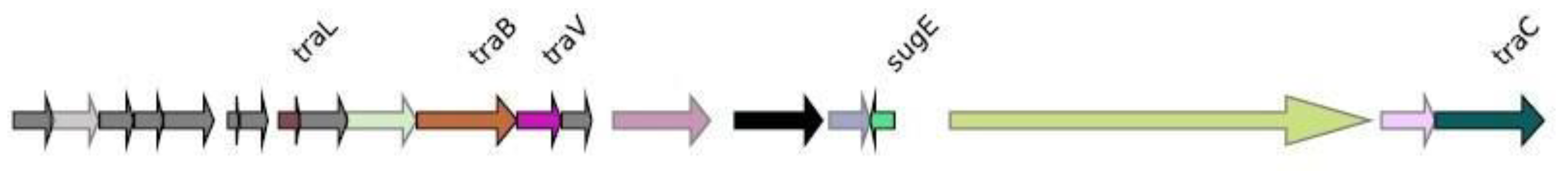

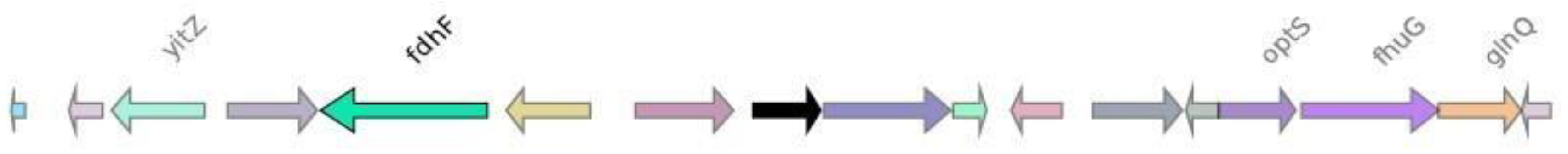

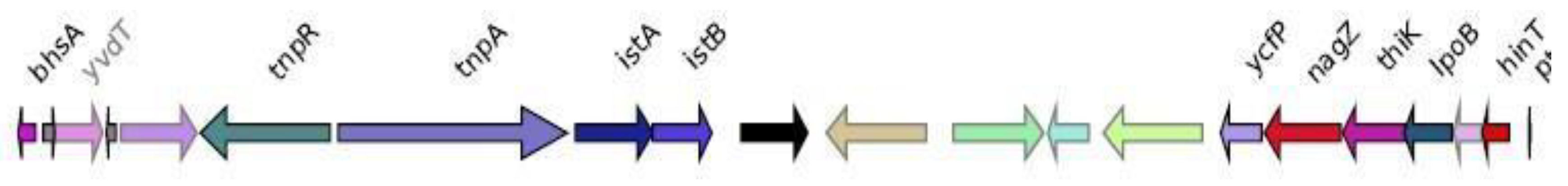

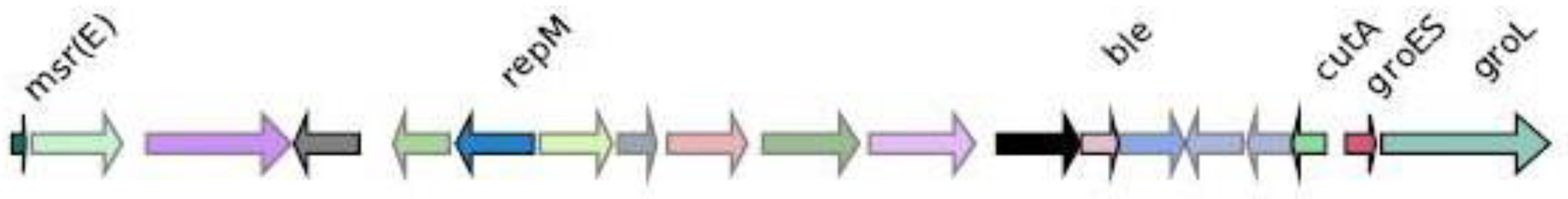

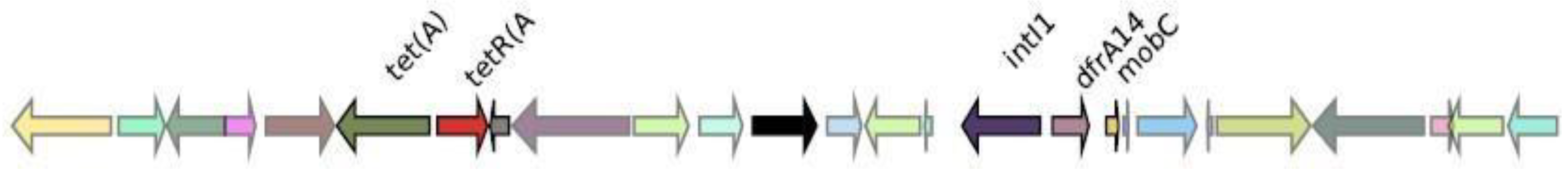

Genomic context analysis

CMY-2

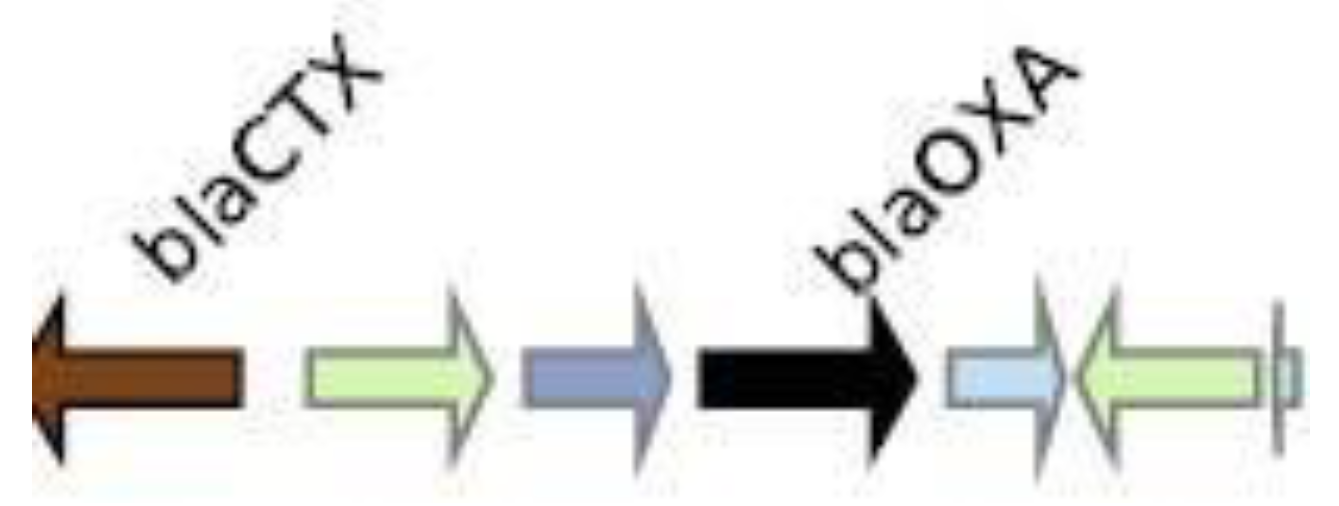

CTX-M-27

IMP-4

KPC-3

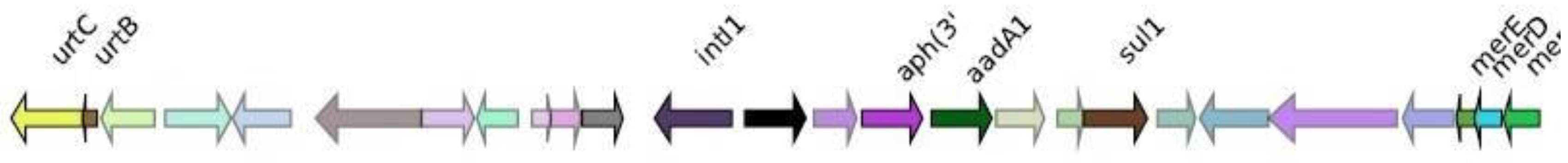

NDM-1

OXA-1

SHV-11

VIM-1

PLSDB

MLST

Discussions

Conclusions

References

- Yang P, Chen Y, Jiang S, Shen P, Lu X, Xiao Y. association between antibiotic consumption and the rate of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria from China based on 153 tertiary hospitals data in 2014. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1):137. [CrossRef]

- Band VI, Satola SW, Burd EM, Farley MM, Jacob JT, Weiss DS. Carbapenem- Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Exhibiting Clinically Undetected Colistin Heteroresistance Leads to Treatment Failure in a Murine Model of Infection. mBio. 9(2):e02448-17. [CrossRef]

- Ma YX, Wang CY, Li Y.Y., et al. Considerations and Caveats in Combating ESKAPE Pathogens against Nosocomial Infections. Adv Sci Weinh Baden-Wurtt Ger. 2020;7(1):1901872. [CrossRef]

- Andrey DO, Pereira Dantas P, Martins WBS, et al. An Emerging Clone, Klebsiellapneumoniae Carbapenemase 2-Producing K. pneumoniae Sequence Type 16, Associated With High Mortality Rates in a CC258-Endemic Setting. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020;71(7):e141-e150. [CrossRef]

- Cole M, Baddiley J, Abraham EP.' β-Lactams' as β-lactamase inhibitors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1980;289(1036):207-223. [CrossRef]

- Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA. Carbapenems: Past, Present, and Future ▿ . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(11):4943- 4960. 4960. [CrossRef]

- Thienamycin, a new A β-lactam antibiotic I. Discovery,taxonomy, isolation and physical properties. Accessed April 7, 2022. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/antibiotics1968/32/1/32_1_1/_article/-char/ja/.

- Synthesis and in vitro activity of a new carbapenem, RS-533. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/antibiotics1968/36/8/36_8_1034/_article/- char/ja/.

- Graham DW, Ashton WT, Barash L, et al. Inhibition of the mammalian .beta.- lactamase renal dipeptidase (dehydropeptidase-I) by Z-2-(acylamino)-3- substituted-propenoic acids. J Med Chem. 1987;30(6):1074-1090. [CrossRef]

- Norrby SR, Alestig K, Björnegård B, et al. Urinary Recovery of N-Formimidoyl Thienamycin (MK0787) as Affected by Coadministration of N-Formimidoyl Thienamycin Dehydropeptidase Inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23(2):300-307. [CrossRef]

- Oliver A, Levin BR, Juan C, Baquero F, Blázquez J. Hypermutation and the Preexistence of Antibiotic-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Mutants: Implications for Susceptibility Testing and Treatment of Chronic Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(11):4226-4233. [CrossRef]

- Mandell L. Doripenem: A New Carbapenem in the Treatment of Nosocomial Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(Supplement_1):S1-S3. [CrossRef]

- Hugonnet JE, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE, Blanchard JS. Meropenem- Clavulanate Is Effective Against Extensively Drug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2009;323(5918):1215-1218. [CrossRef]

- Meletis G. Carbapenem resistance: overview of the problem and future perspectives. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2016;3(1):15-21. [CrossRef]

- Deris ZZ, Yu HH, Davis K, et al. The Combination of Colistin and Doripenem Is Synergistic against Klebsiella pneumoniae at Multiple Inocula and Suppresses Colistin Resistance in an In Vitro Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(10):5103-5112. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martínez L. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases and the permeability barrier. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(s1):82-89. [CrossRef]

- Pitout JDD, Nordmann P, Poirel L. Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a Key Pathogen Set for Global Nosocomial Dominance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(10):5873-5884. [CrossRef]

- Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(4):228-236. [CrossRef]

- Bebrone C. Metallo-β-lactamases (classification, activity, genetic organization, structure, zinc coordination) and their superfamily. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74(12):1686-1701. [CrossRef]

- Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, et al. Characterization of a New Metallo-β- Lactamase Gene, blaNDM-1, and a Novel Erythromycin Esterase Gene Carried on a Unique Genetic Structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae Sequence Type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(12):5046-5054. [CrossRef]

- Poirel L, Potron A, Nordmann P. OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(7):1597-1606. [CrossRef]

- Tsilipounidaki K, Athanasakopoulou Z, Müller E, et al. Plethora of Resistance Genes in Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria in Greece: No End to a Continuous Genetic Evolution. Microorganisms. 2022;10(1):159. [CrossRef]

- van Duin D, Doi Y. The global epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence. 2017;8(4):460-469. [CrossRef]

- Schwaber MJ, Klarfeld-Lidji S, Navon-Venezia S, Schwartz D, Leavitt A, Carmeli Y. Predictors of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Acquisition among Hospitalized Adults and Effect of Acquisition on Mortality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(3):1028-1033. [CrossRef]

- Suay-García B, Pérez-Gracia MT. Present and Future of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Infections. Antibiot Basel Switz. 2019;8(3):E122. [CrossRef]

- Alcock BP, Raphenya AR, Lau TTY, et al. CARD 2020: antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D517-D525. [CrossRef]

- Garcia PS, Jauffrit F, Grangeasse C, Brochier-Armanet C. GeneSpy, a user- friendly and flexible genomic context visualizer. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2019;35(2):329-331. [CrossRef]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(7):3022-3027. [CrossRef]

- Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W293-W296. [CrossRef]

- Galata V, Fehlmann T, Backes C, Keller A. PLSDB: a resource of complete bacterial plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D195-D202. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Shen P, Wei Z, et al. Dissemination of a clone carrying a fosA3- harbouring plasmid mediates high fosfomycin resistance rate of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;45(1):66-70. [CrossRef]

- Chen YC, Chen WY, Hsu WY, et al. Distribution of β-lactamases and emergence of carbapenemases co-occurring Enterobacterales isolates with high- level antibiotic resistance identified from patients with intra-abdominal infection in the Asia–Pacific region, 2015–2018. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. Published online July 21, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Verdet C, Gautier V, Chachaty E, et al. Genetic Context of Plasmid-Carried blaCMY-2-Like Genes in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(9):4002-4006. [CrossRef]

- Espedido BA, Partridge SR, Iredell JR. blaIMP-4 in Different Genetic Contexts in Enterobacteriaceae Isolates from Australia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(8):2984-2987. [CrossRef]

- Liao J, Chen Y. Removal of intl1 and associated antibiotics resistant genes in water, sewage sludge and livestock manure treatments. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2018;17(3):471-500. [CrossRef]

- Vetting MW, Park CH, Hegde SS, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC, Blanchard JS. Mechanistic and Structural Analysis of Aminoglycoside N-Acetyltransferase AAC(6′)-Ib and Its Bifunctional, Fluoroquinolone-Active AAC(6′)-Ib-cr Variant,. Biochemistry. 2008;47(37):9825-9835. [CrossRef]

- Khan AU, Maryam L, Zarrilli R. Structure, Genetics and Worldwide Spread of New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase (NDM): a threat to public health. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):101. [CrossRef]

- Reimmann C, Haas D. The istA gene of insertion sequence IS21 is essential for cleavage at the inner 3' ends of tandemly repeated IS21 elements in vitro. EMBO J. 1990;9(12):4055-4063.

- Masseron A, Poirel L, Falgenhauer L, et al. Ongoing dissemination of OXA-244 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli in Switzerland and their detection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;97(3):115059. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira ÉM, Beltrão EMB, Scavuzzi AML, Barros JF, Lopes ACS. High plasmid variability, and the presence of IncFIB, IncQ, IncA/C, IncHI1B, and IncL/M in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae with bla KPC and bla NDM from patients at a public hospital in Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 53:e20200397. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Liu C, Liu Y, et al. Genomic characteristics of clinically important ST11 Klebsiella pneumoniae strains worldwide. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:519-526. [CrossRef]

- Gondal AJ, Saleem S, Jahan S, Choudhry N, Yasmin N. Novel Carbapenem- Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 Coharboring blaNDM-1, blaOXA-48 and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases from Pakistan. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:2105-2115. [CrossRef]

- Hirakata Y, Kondo A, Hoshino K, et al. Efflux pump inhibitors reduce the invasiveness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34(4):343-346. [CrossRef]

| KPC | OXA | NDM | IMP | VIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPC-1 | OXA-1 | NDM-1 | IMP-1 | VIM-1 |

| KPC-3 | OXA-2 | NDM-3 | IMP-4 | VIM-27 |

| KPC-4 | OXA-9 | NDM-4 | IMP-38 | |

| KPC-12 | OXA-10 | NDM-5 | IMP-68 | |

| KPC-14 | OXA-48 | NDM-6 | ||

| KPC-31 | OXA-181 | NDM-7 | ||

| KPC-33 | OXA-204 | NDM-19 | ||

| KPC-40 | OXA-232 | |||

| KPC-74 | OXA-244 |

| Drug class | Gene/Protein | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | AAC(3')-IIc | 66.66667 |

| Aminoglycosides | AAC(3')-IV | 61.01695 |

| Aminoglycosides | APH(4')-Ia | 61.01695 |

| Aminoglycosides | LAP-2 | 67.12329 |

| Aminoglycosides | aadA3 | 70.16575 |

| Aminoglycosides | rmtB | 77.41935 |

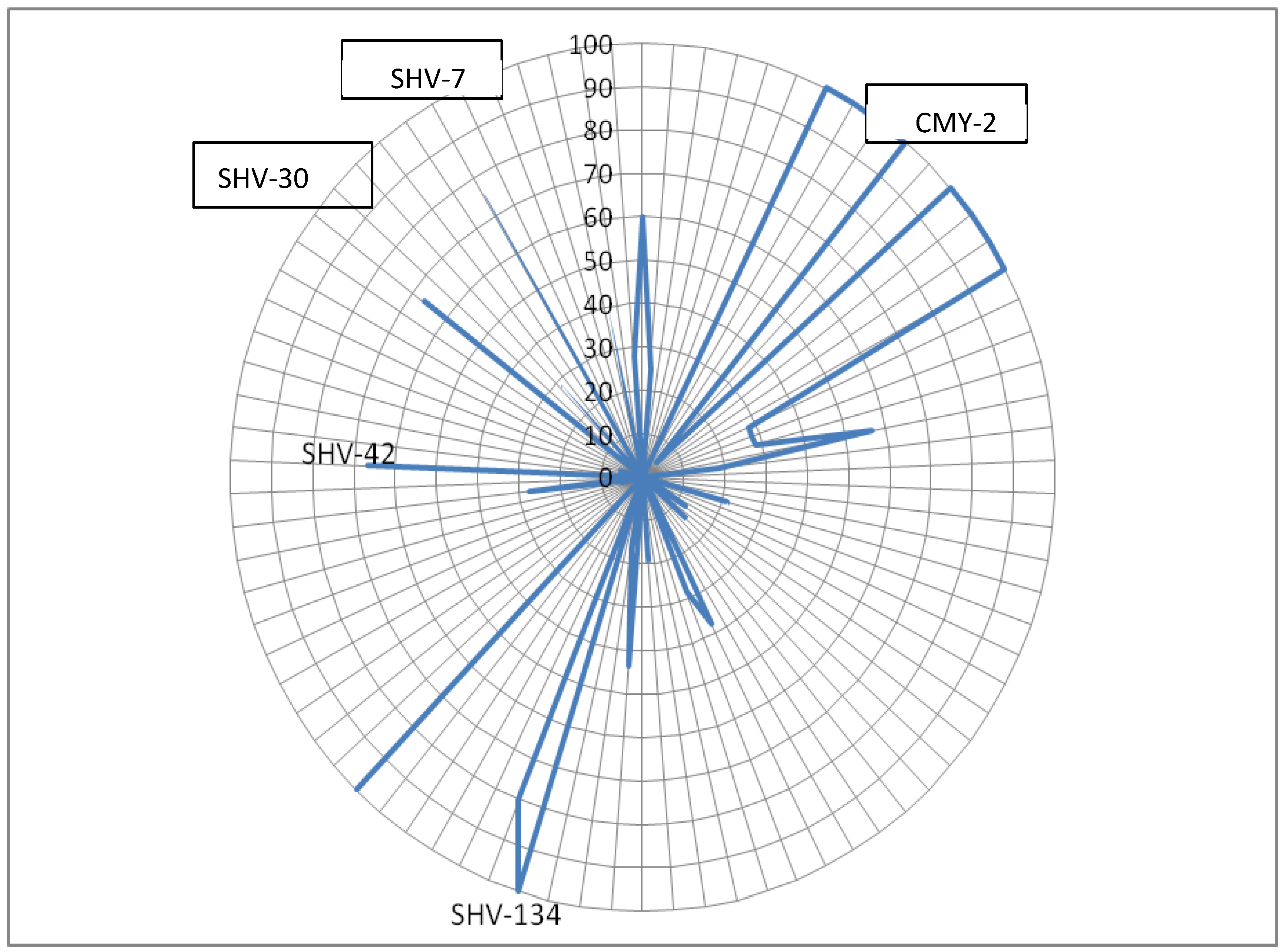

| Carbapenem | SHV-134 | 80.165 |

| Carbapenem | SHV-30 | 66.66667 |

| Diaminopyrimidine | dfrA25 | 66.66667 |

| Diaminopyrimidine | oqxB | 57 |

| Disinfecting agents and intercalating dyes | qacL | 65.15152 |

| Fluoroquinolones | LAP-2 | 67.12329 |

| Fluoroquinolones | Salmonella serovars gyrB conferring resistance to fluoroquinolone | 79.7619 |

| Fosfomycin | fosA3 | 81.03448 |

| Monobactam | TEM-214 | 66.66667 |

| Penem | SHV-134 | 80.16529 |

| Penem | TEM-214 | 66.66667 |

| Phenicol | catII from Escherichia coli K-12 | 75.92593 |

| Phenicol | cmlA1 | 61.81818 |

| Rifamycin | Escherichia coli rpoB mutants conferring resistance to rifampicin | 66.66667 |

| Rifamycin | LAP-2 | 67.12329 |

| Tetracyclin | LAP-2 | 67.12329 |

| Triclosan | Salmonella enterica gyrA with mutation conferring resistance to triclosan | 72.72727 |

| Drug class | Genes/Protein | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| aminoglycoside antibiotic | APH(3')-VI | 92.85714286 |

| diaminopyrimidine antibiotic | dfrA5 | 77.77777778 |

| glycopeptide antibiotic | determinant of bleomycin resistance | 98.11320755 |

| Drug class | Genes/Proteins | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| aminoglycoside antibiotic | AAC(3')-IIe | 90.09901 |

| aminoglycoside antibiotic | AAC(6’)-Ib-cr5 | 80.69498 |

| aminoglycoside antibiotic | APH(3')-VI | 96.42857 |

| aminoglycoside antibiotic | APH(3')-VIb | 83.33333 |

| aminoglycoside antibiotic | aadA | 62.26415 |

| aminoglycoside antibiotic | armA | 65.33333 |

| aminoglycoside antibiotic | rmtF | 84.21053 |

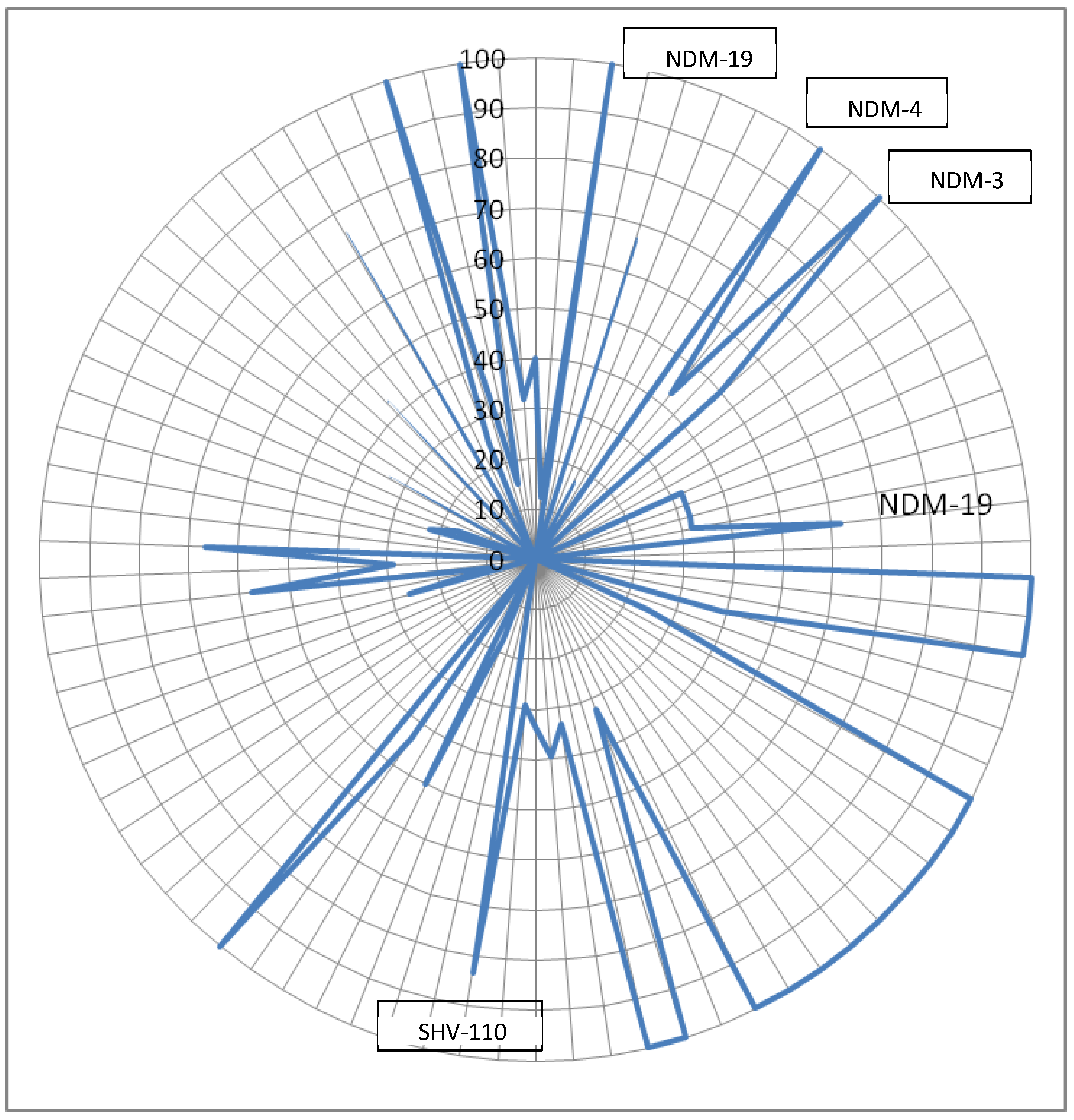

| carbapenem | IMP-4 | 66.66667 |

| carbapenem | NDM-1 | 61.84211 |

| carbapenem | SHV-110 | 83.33333 |

| carbapenem | SHV-30 | 66.66667 |

| cephalosporin | CTX-M-194 | 91.66667 |

| cephalosporin | CTX-M-2 | 100 |

| cephalosporin | CTX-M-55 | 66.66667 |

| cephamycin | CMY-4 | 92.30769 |

| diaminopyrimidine antibiotic | dfrA1 | 67.01031 |

| diaminopyrimidine antibiotic | dfrA14 | 61.39535 |

| diaminopyrimidine antibiotic | dfrA23 | 100 |

| diaminopyrimidine antibiotic | dfrA35 | 100 |

| fluoroquinolone antibiotic | AAC(6’)-Ib-cr5 | 80.69498 |

| fluoroquinolone antibiotic | QnrB1 | 80.4878 |

| fluoroquinolone antibiotic | QnrB9 | 66.66667 |

| lincosamide antibiotic | ErmB | 75.67568 |

| macrolide antibiotic | EreA2 | 94.44444 |

| macrolide antibiotic | ErmB | 75.67568 |

| penam | CTX-M-15 | 77.69784 |

| nucleoside antibiotic | SAT-1 | 96.875 |

| rifamycin antibiotic | arr-2 | 92.20779 |

| tetracycline antibiotic | tet(B) | 66.66667 |

| tetracycline antibiotic | tetR | 71.42857 |

| Plasmid type | Gene |

|---|---|

| IncFIA | blaSHV-11 |

| IncFIB | blaOXA-1, blaCTX-M-27, blaIMP-4, blaKPC-3, blaNDM-1 |

| IncFII | blaOXA-1, blaKPC-3 |

| IncHIB | blaNDM-1, blaSHV-11 |

| IncI2 | blaKPC-3 |

| IncFIA | blaSHV-11, blaCTX-M-27 |

| IncC | blaCMY-2, blaIMP-4, blaVIM-1 |

| IncN | blaIMP-4 |

| IncR | blaVIM-1, blaSHV-11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).