Submitted:

03 February 2023

Posted:

07 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

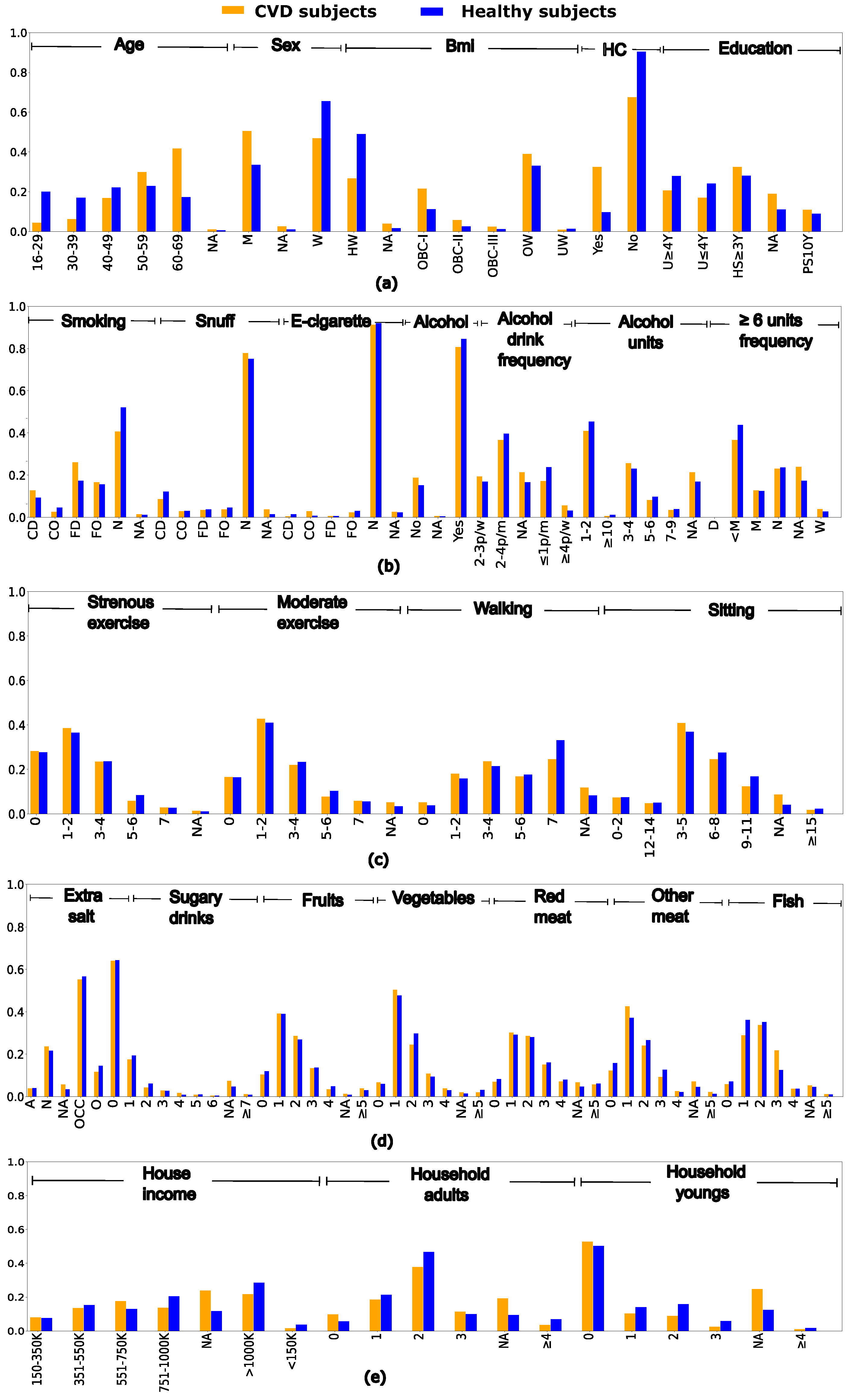

2.1. Dataset description and pre-processing

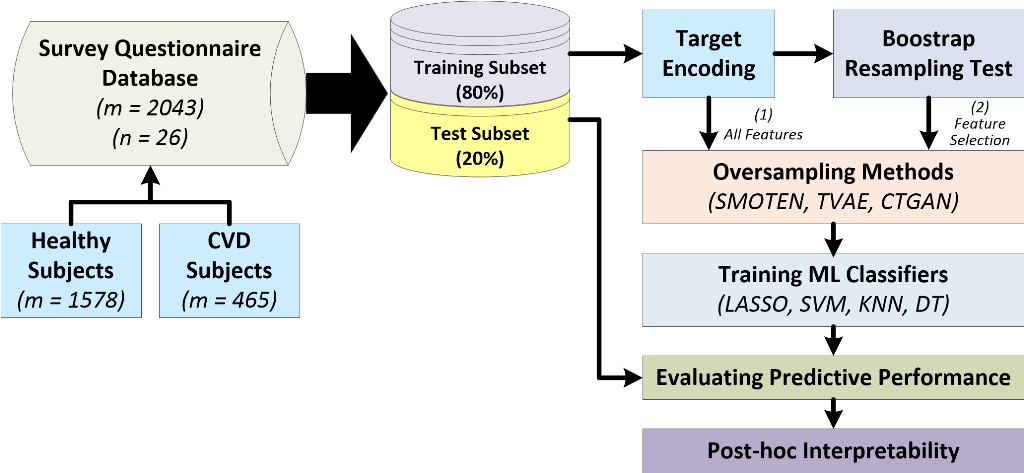

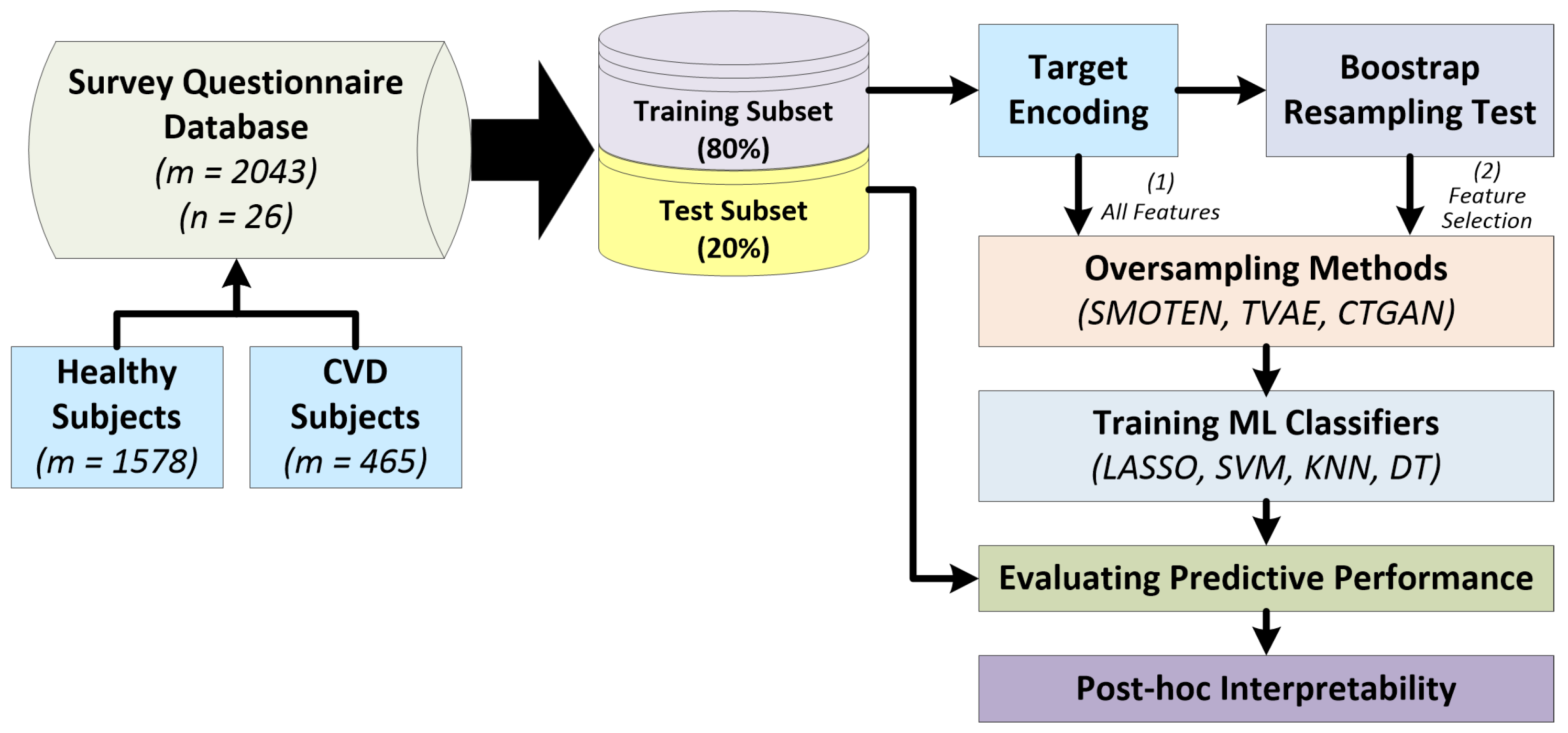

2.2. Workflow for predicting cardiovascular diseases

2.2.1. Encoding categorical data

2.2.2. Feature selection using bootstrap resampling test

2.2.3. Resampling techniques for imbalance learning

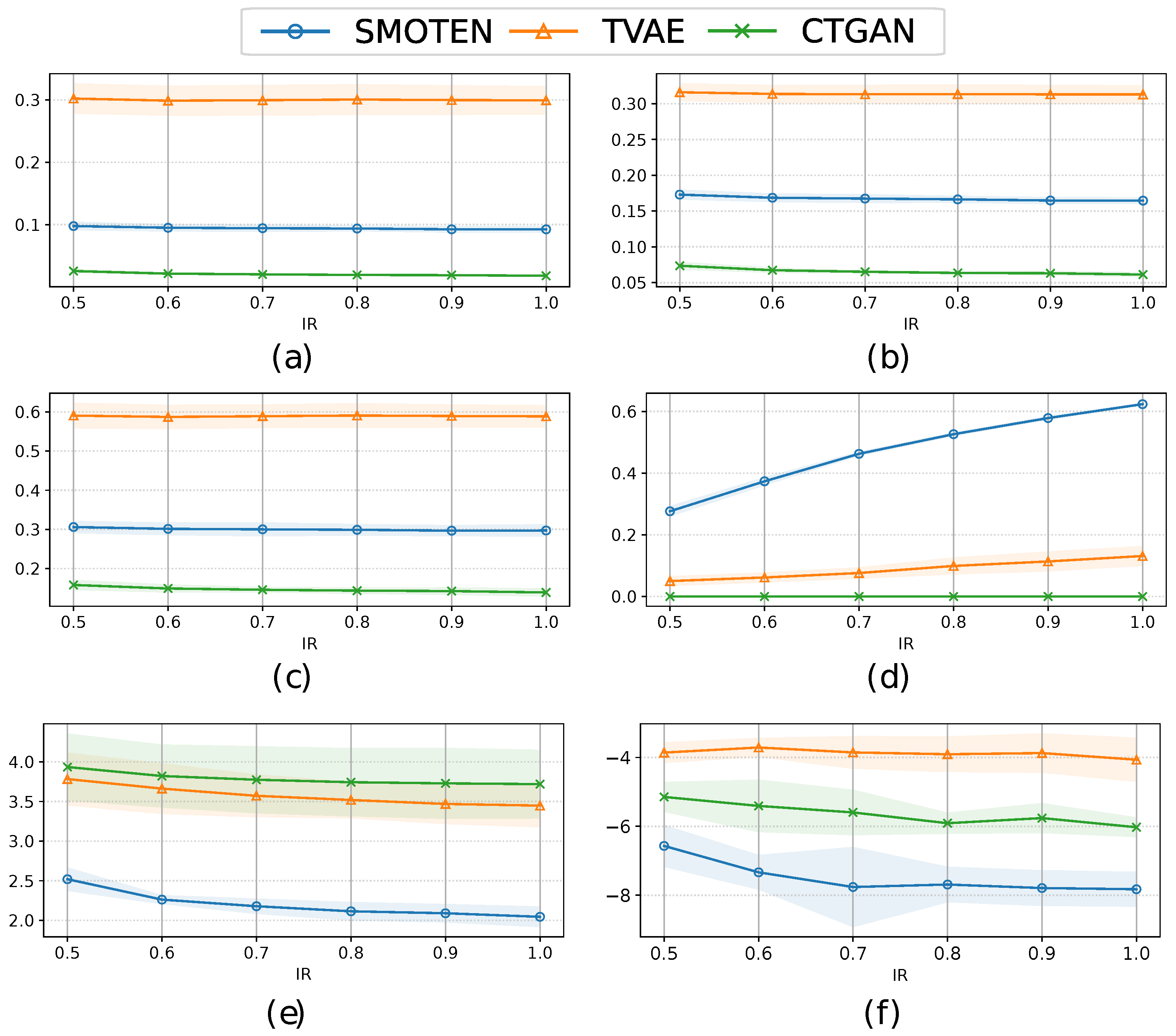

2.2.4. Quality metrics for synthetic data

- KLD [48] measures the similarity of the two PMFs, and is computed over a pair of real and synthetic marginal PMFs for a given feature. It is defined as:Note that denotes the nonsymmetric KLD. When both distributions are identical the symmetric KLD is zero, while larger values indicate a larger discrepancy between the two PMFs.

- HD [49] quantifies the similarity between two probability distributions for a specific feature, and it is calculated as:

- MAEP measures the absolute difference between the PMFs associated with each category of a common feature in and . For a given feature, MAEP is defined as:where is the number of categories for a given feature, and are the common categories of a feature, and and are the probabilities assigned in the corresponding PMF for such category. Note that KLD, HD and MAEP allow assessing univariate attribute fidelity, determining that all marginal distributions of and are properly matching.

- RSVR indicates the rate of repeated sample vectors in the synthetic data , denoting how well the oversampling methods create unique vectors. It is worth noting that this metric is directly related to the number of samples generated, as the IR increases, the likelihood of the onset of repeated vectors is high and consequently, RSVR could augment. It is important to remark that KLD, HD, and MAEP are defined at the feature level, i.e., they are computed for a single feature. To calculate an overall metric, the average value across all features is computed, adding the contribution of each feature.

- PCD [50] quantifies the difference, in terms of the Frobennius norm, of the Pearson correlation matrices of and . PCD is defined as:

- LCM [51] measures the similarity of the underlying latent structure of and in terms of clustering. This metric relies on two steps. Firstly, and are merged into one single dataset, and then, a cluster analysis using the k-means algorithm [52] is performed on this dataset with a fixed number of clusters k [50]. LCM is defined as follows:being the number of samples in the j-th cluster, the number of samples from the real dataset in the j-th cluster, and (where and are the numbers of real and synthetic samples, respectively) [50]. High values of LCM denote disparities in the cluster memberships, indicating high differences in the distribution of and [50].

2.2.5. ML classifiers and figures of merit

3. Results

3.1. Experimental setup

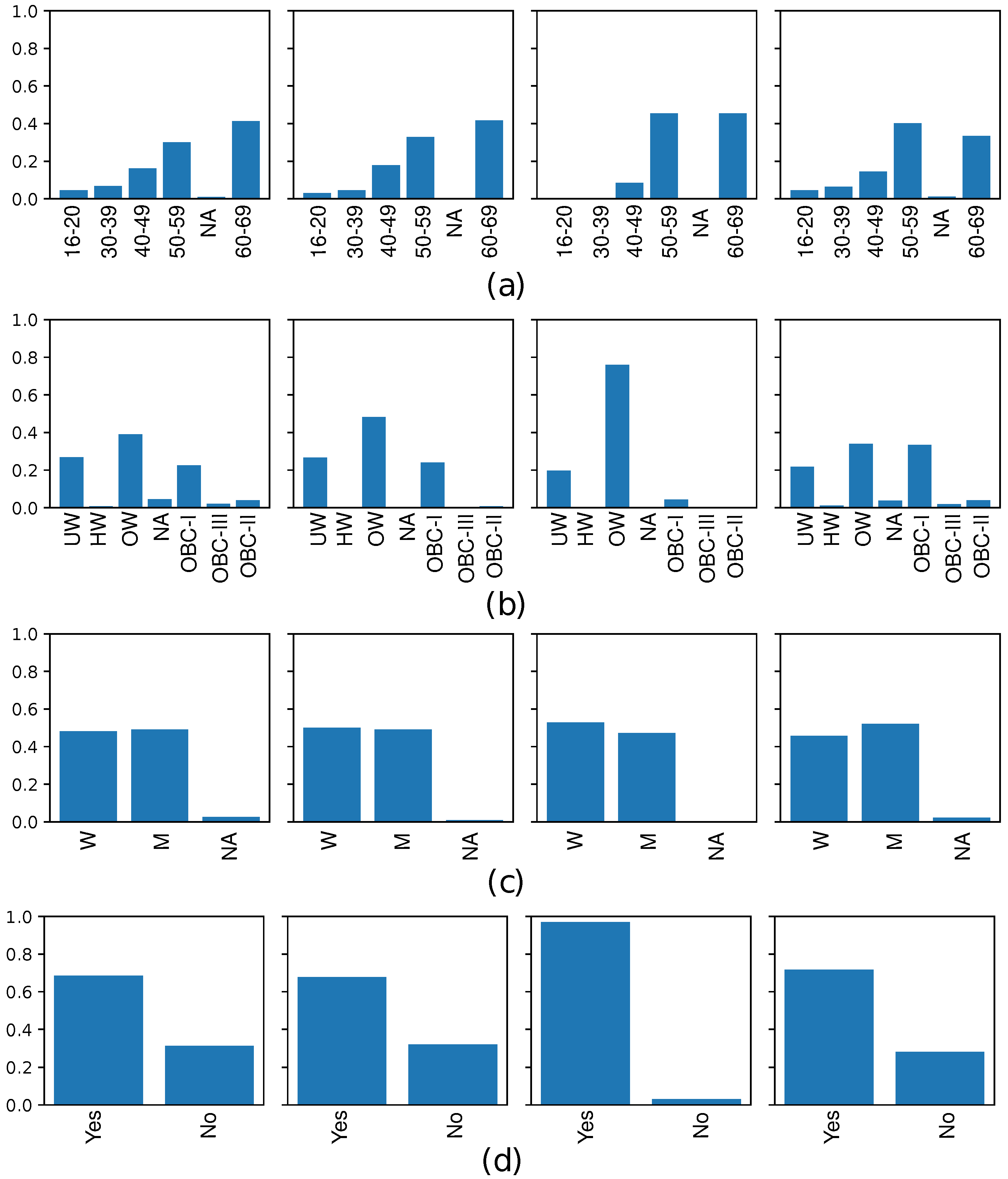

3.2. Quality evaluation of synthetic clinical data

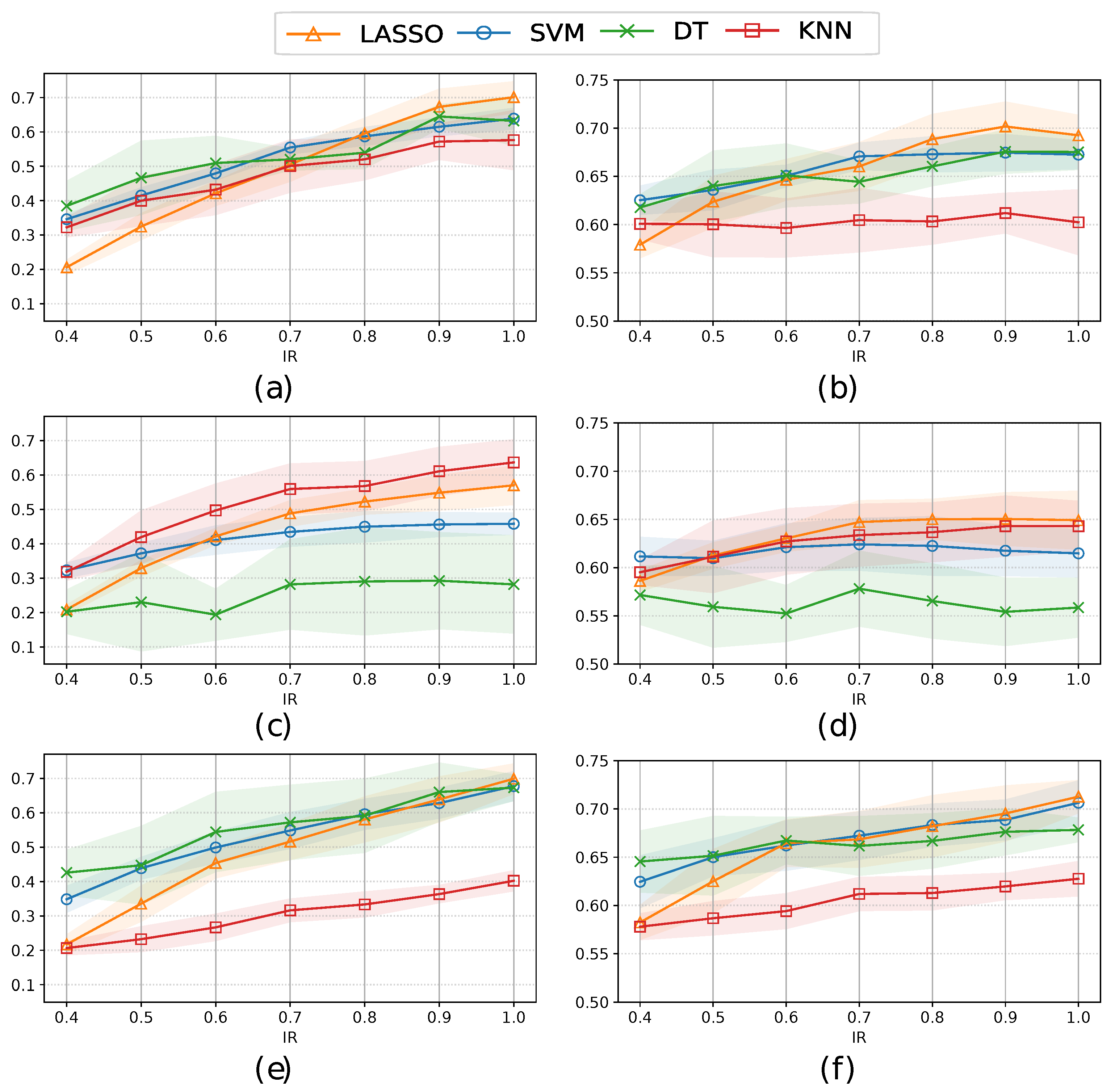

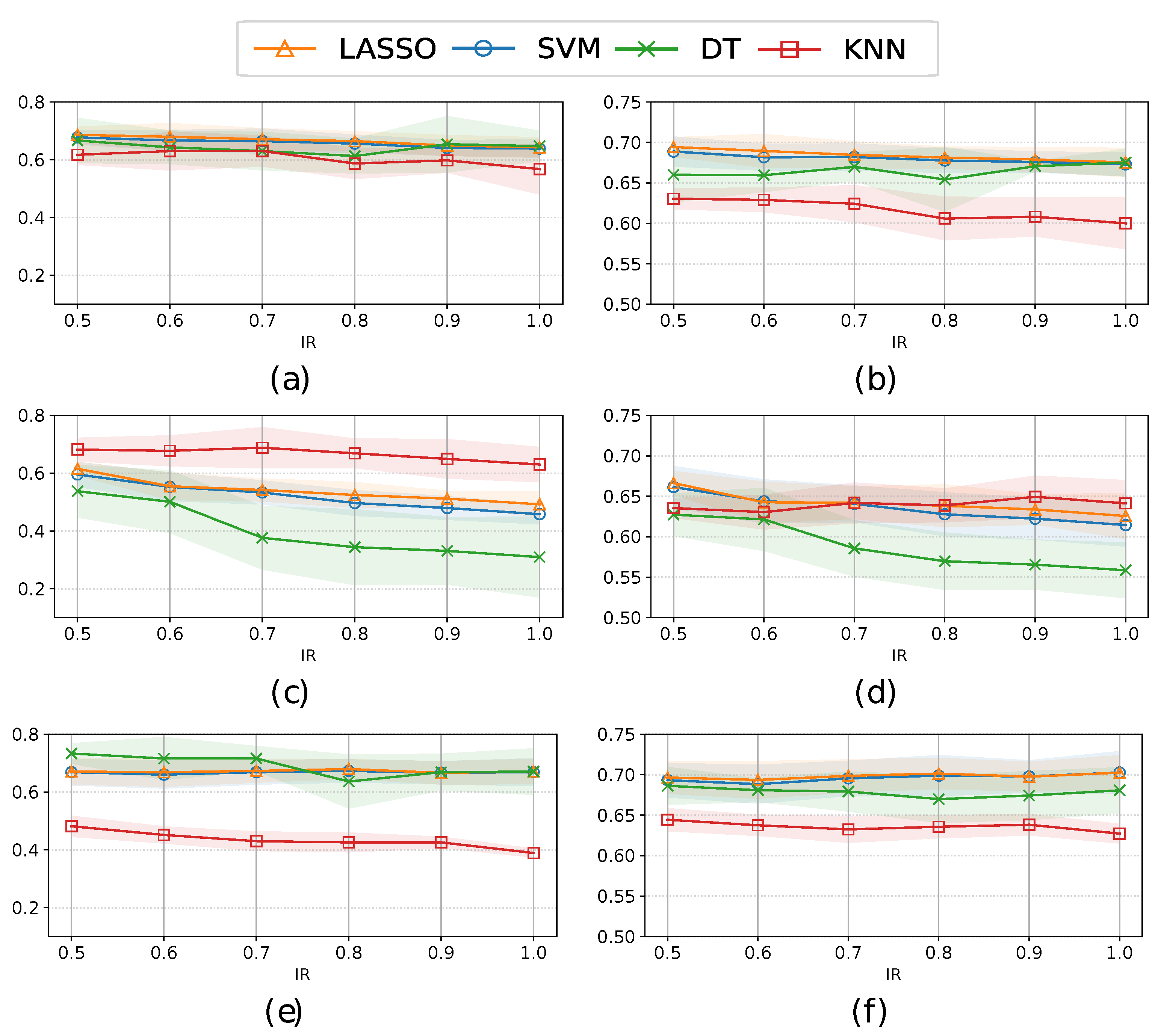

3.3. Classification performance

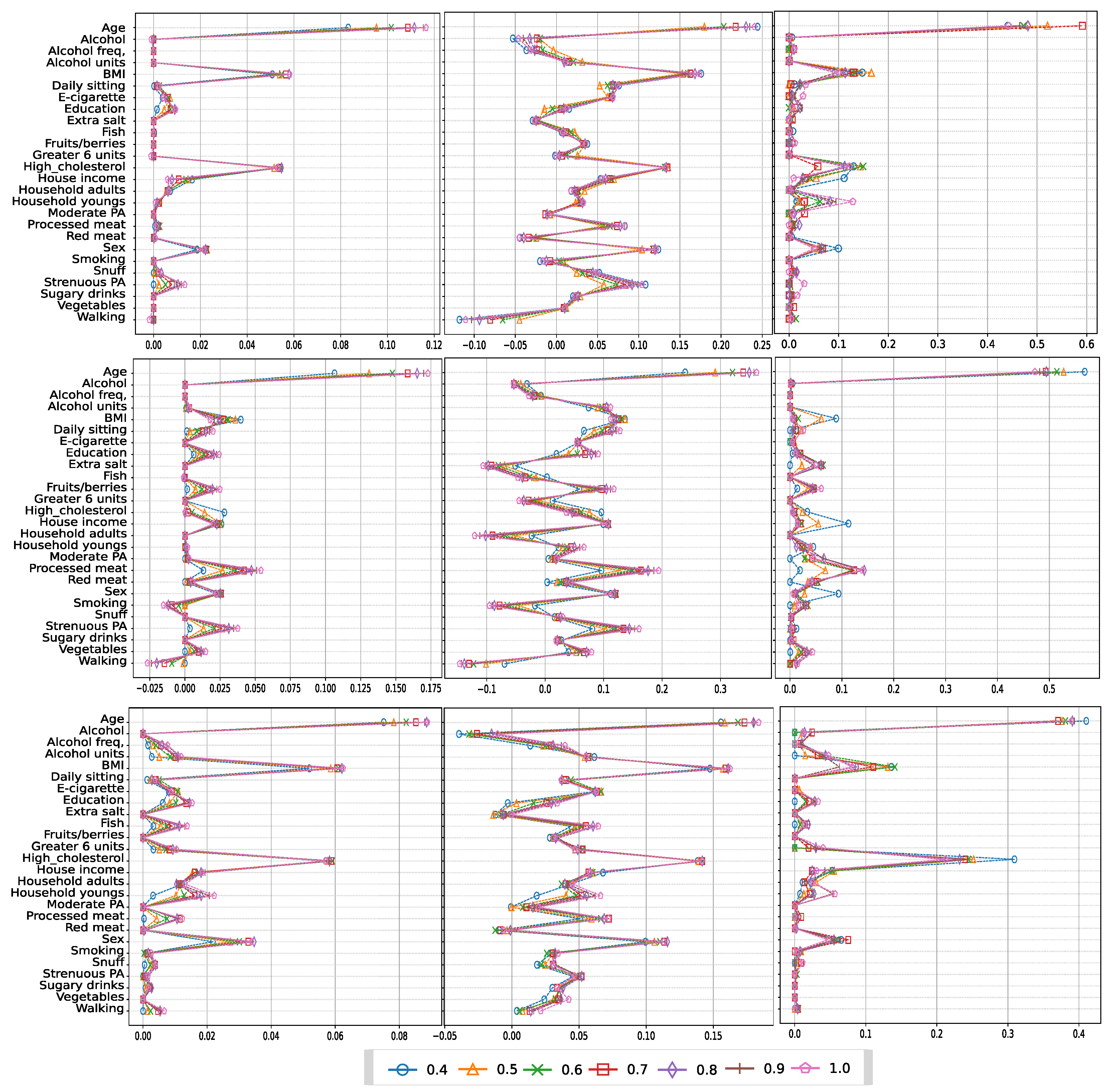

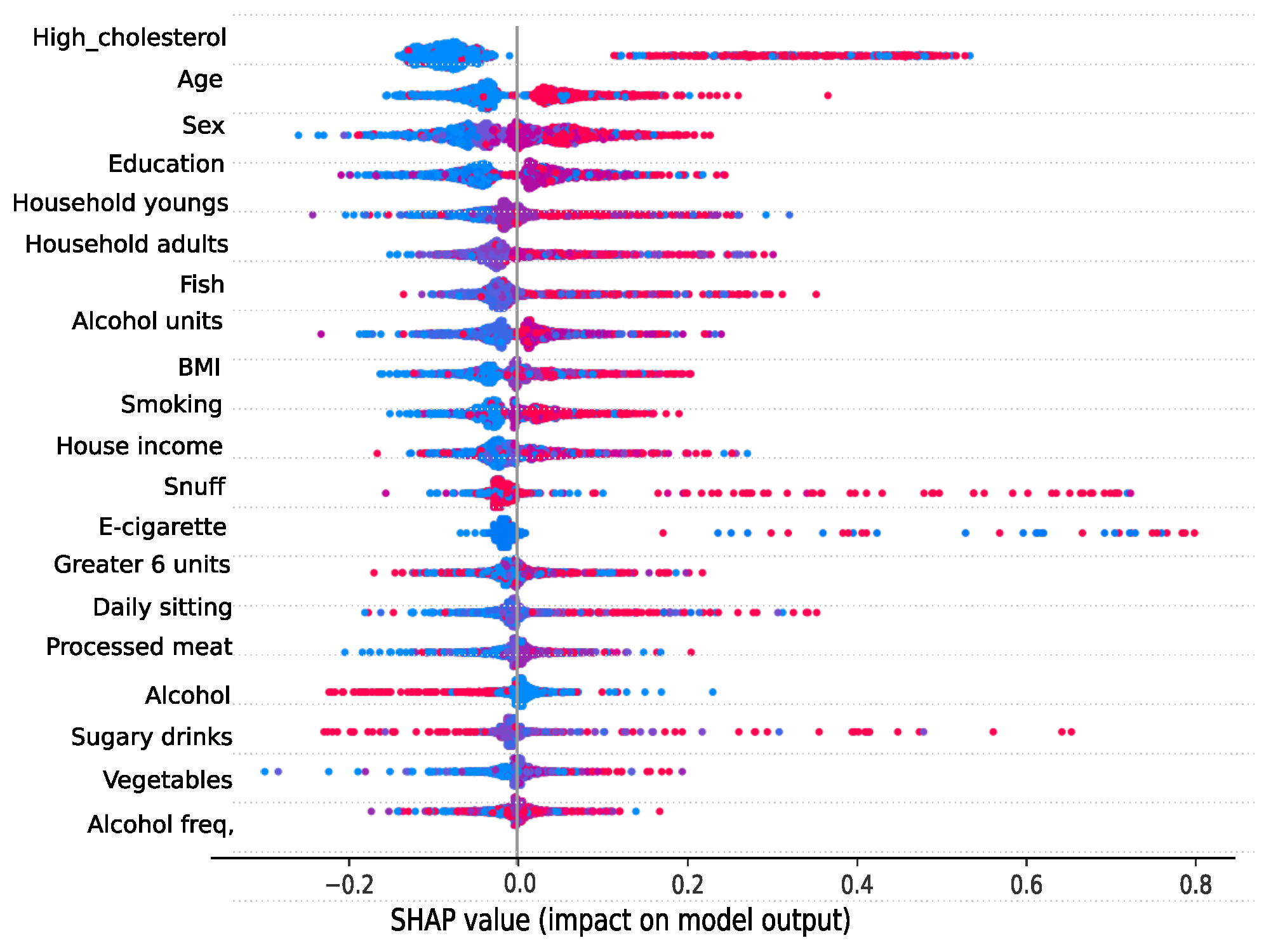

3.4. Analyzing risk factors using interpretability methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CTGAN | Conditional Tabular Generative Adversarial Network |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| FS | Feature Selection |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| HD | Hellinger Distance |

| IR | Imbalance Ratio |

| KLD | Kullback-Leibler Divergence |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| LCM | Log-Cluster Metric |

| MAEP | Mean Absolute Error Probability |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| PCD | Pairwise Correlation Difference |

| RSVR | Repeated Sample Vector Rate |

| RUS | Random Under Sampling |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

Abbreviations

| SMOTEN | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique Nominal |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TVAE | Tabular Variational Autoencoder |

References

- Raghupathi, W.; Raghupathi, V. Big data analytics in healthcare: promise and potential. Health Information Science and Systems 2014, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengio, Y.; Lecun, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning for AI. Communications of the ACM 2021, 64, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lin, T.; Xia, X.; Xu, H.; Ding, S. A synthetic neighborhood generation based ensemble learning for the imbalanced data classification. Applied Intelligence 2018, 48, 2441–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeira Marques, M.; Moraes Villela, S.; Hasenclever Borges, C.C. Large margin classifiers to generate synthetic data for imbalanced datasets. Applied Intelligence 2020, 50, 3678–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. A novel synthetic minority oversampling technique based on relative and absolute densities for imbalanced classification. Applied Intelligence 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.; Arroba, P.; Moya, J.M. Data augmentation through multivariate scenario forecasting in Data Centers using Generative Adversarial Networks. Applied Intelligence 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Luo, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Ren, S.; Zeng, Y. Minority oversampling for imbalanced time series classification. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 247, 108764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.; Kamal, S. An empirical study to investigate oversampling methods for improving software defect prediction using imbalanced data. Neurocomputing 2019, 343, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Garcia, S.; Herrera, F.; Chawla, N.V. SMOTE for learning from imbalanced data: progress and challenges, marking the 15-year anniversary. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2018, 61, 863–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Jiang, A.; Li, T.; Xue, Y.; Wang, G. LR-SMOTE–An improved unbalanced data set oversampling based on K-means and SVM. Knowledge-Based Systems 2020, 196, 105845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, L.; Evans, R.S.; Shyu, C.; Egger, M.; Chawla, N.; Mitchell, J.; Thornton, S.N.; Bray, B.; Varner, M. Countering imbalanced datasets to improve adverse drug event predictive models in labor and delivery. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2009, 42, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelmann, J.; Lessmann, S. Conditional Wasserstein GAN-based oversampling of tabular data for imbalanced learning. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 174, 114582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Khushi, M. SMOTE-ENC: A novel SMOTE-based method to generate synthetic data for nominal and continuous features. Applied System Innovation 2021, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vicente, C.; Chushig-Muzo, D.; Mora-Jiménez, I.; Fabelo, H.; Gram, I.T.; Løchen, M.L.; Granja, C.; Soguero-Ruiz, C. Clinical Synthetic Data Generation to Predict and Identify Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Diseases. Heterogeneous Data Management, Polystores, and Analytics for Healthcare: VLDB Workshops, Poly 2022 and DMAH 2022, Virtual Event, September 9, 2022, Revised Selected Papers. Springer, 2023, pp. 75–91.

- Gui, J.; Sun, Z.; Wen, Y.; Tao, D.; Ye, J. A review on generative adversarial networks: Algorithms, theory, and applications. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Skoularidou, M.; Cuesta-Infante, A.; Veeramachaneni, K. Modeling tabular data using conditional gan. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, 7335–7345. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Biswal, S.; Malin, B.; Duke, J.; Stewart, W.F.; Sun, J. Generating multi-label discrete patient records using generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, 2017, pp. 286–305.

- Meijers, W.C.; Maglione, M.; Bakker, S.J.; Oberhuber, R.; Kieneker, L.M.; de Jong, S.; Haubner, B.J.; Nagengast, W.B.; Lyon, A.R.; van der Vegt, B.; others. Heart failure stimulates tumor growth by circulating factors. Circulation 2018, 138, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gram, I.T.; Skeie, G.; Oyeyemi, S.O.; Borch, K.B.; Hopstock, L.A.; Løchen, M.L. A Smartphone-Based Information Communication Technology Solution for Primary Modifiable Risk Factors for Noncommunicable Diseases: Pilot and Feasibility Study in Norway. JMIR Formative Research 2022, 6, e33636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargent, F.; Pfisterer, F.; Thomas, J.; Bischl, B. Regularized target encoding outperforms traditional methods in supervised machine learning with high cardinality features. Computational Statistics 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, V.; Krantsevich, C.; Hahn, P.R.; Hahn, S.; Dasarathy, G.; Turaga, P.; Liss, J. Digital medicine and the curse of dimensionality. NPJ Digital Medicine 2021, 4, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montavon, G.; Samek, W.; Müller, K.R. Methods for interpreting and understanding deep neural networks. Digital Signal Processing 2018, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chushig-Muzo, D.; Soguero-Ruiz, C.; de Miguel-Bohoyo, P.; Mora-Jiménez, I. Interpreting clinical latent representations using autoencoders and probabilistic models. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2021, 122, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, G.; Kocbek, P.; Fijacko, N.; Zitnik, M.; Verbert, K.; Cilar, L. Interpretability of machine learning-based prediction models in healthcare. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2020, 10, e1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese Robinson, R.L.; Palczewska, A.; Palczewski, J.; Kidley, N. Comparison of the predictive performance and interpretability of random forest and linear models on benchmark data sets. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2017, 57, 1773–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, D.V.; Pereira, E.M.; Cardoso, J.S. Machine learning interpretability: A survey on methods and metrics. Electronics 2019, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Nowak, R.; Cox, C.; Rogers, T. Classification with the sparse group lasso. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2015, 64, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Safavian, S.R.; Landgrebe, D. A survey of decision tree classifier methodology. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1991, 21, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Zhou, Z.H. ML-KNN: A lazy learning approach to multi-label learning. Pattern Recognition 2007, 40, 2038–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, pp. 4768––4777.

- Bush, K.; Kivlahan, D.R.; McDonell, M.B.; Fihn, S.D.; Bradley, K.A.; (ACQUIP, A.C.Q.I.P.; others. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine 1998, 158, 1789–1795. [CrossRef]

- Hagströmer, M.; Oja, P.; Sjöström, M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutrition 2006, 9, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chushig-Muzo, D.; Soguero-Ruiz, C.; Engelbrecht, A.P.; Bohoyo, P.D.M.; Mora-Jiménez, I. Data-driven visual characterization of patient health-status using electronic health records and self-organizing maps. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 137019–137031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, P.; Varoquaux, G.; Kégl, B. Similarity encoding for learning with dirty categorical variables. Machine Learning 2018, 107, 1477–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micci-Barreca, D. A preprocessing scheme for high-cardinality categorical attributes in classification and prediction problems. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter 2001, 3, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, S. Feature selection in machine learning: A new perspective. Neurocomputing 2018, 300, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Jiménez, Inmaculada and Tarancón-Rey, Jorge and Álvarez-Rodríguez, Joaquín and Soguero-Ruiz, Cristina. Artificial Intelligence to Get Insights of Multi-Drug Resistance Risk Factors during the First 48 Hours from ICU Admission. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 239.

- Martínez-Agüero, S.; Soguero-Ruiz, C.; Alonso-Moral, J.M.; Mora-Jiménez, I.; Álvarez Rodríguez, J.; Marques, A.G. Interpretable clinical time-series modeling with intelligent feature selection for early prediction of antimicrobial multidrug resistance. Future Generation Computer Systems 2022, 133, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haixiang, G.; Yijing, L.; Shang, J.; Mingyun, G.; Yuanyue, H.; Bing, G. Learning from class-imbalanced data: Review of methods and applications. Expert Systems with Applications 2017, 73, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Z.H. Exploratory undersampling for class-imbalance learning. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 2008, 39, 539–550. [Google Scholar]

- Elreedy, D.; Atiya, A.F. A comprehensive analysis of synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) for handling class imbalance. Information Sciences 2019, 505, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2014.

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Zavrak, S.; İskefiyeli, M. Anomaly-based intrusion detection from network flow features using variational autoencoder. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108346–108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullback, S.; Leibler, R.A. On information and sufficiency. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1951, 22, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cam, L.; LeCam, L.M.; Yang, G.L. Asymptotics in statistics: some basic concepts; Springer Science & Business Media, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves, A.; Ray, P.; Soper, B.; Stevens, J.; Coyle, L.; Sales, A.P. Generation and evaluation of synthetic patient data. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2020, 20, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, M.J.; Reiter, J.P.; Oganian, A.; Karr, A.F. Global measures of data utility for microdata masked for disclosure limitation. Journal of Privacy and Confidentiality 2009, 1, 111–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J.; others. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, Oakland, CA, USA, 1967; 1, pp. 281–297.

- Malik, V.S.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Global obesity: trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2013, 9, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlöf, B. Cardiovascular disease risk factors: epidemiology and risk assessment. The American Journal of Cardiology 2010, 105, 3A–9A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, K.H.; Brath, H. A global view on the development of non communicable diseases. Preventive Medicine 2012, 54, S38–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayen, A.L.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Paccaud, F.; Bovet, P.; Stringhini, S. Socioeconomic determinants of dietary patterns in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2014, 100, 1520–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Bell, R. Social determinants and non-communicable diseases: time for integrated action. Bmj 2019, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaim, A.R.; Almog, R.; Gorelik, Y.; Hochberg, I.; Nassar, L.; Mashiach, T.; Khamaisi, M.; Lurie, Y.; Azzam, Z.S.; Khoury, J.; others. Analyzing Medical Research Results Based on Synthetic Data and Their Relation to Real Data Results: Systematic Comparison From Five Observational Studies. JMIR Medical Informatics 2020, 8, e16492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yale, A.; Dash, S.; Dutta, R.; Guyon, I.; Pavao, A.; Bennett, K.P. Generation and evaluation of privacy preserving synthetic health data. Neurocomputing 2020, 416, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Description | Categories | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background | Age | Indiviual’s age | 16-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, NA |

| Sex | Indiviual’s sex | Woman (W), Man (M), NA | |

| BMI | Body mass index | HW, OBC-I, OBC-II, | |

| OBC-III, OW, UW, NA | |||

| Education | Education level achieved | U<4Y, U≥4Y, PS10Y, HS≥3Y, NA | |

| HC | Have cholesterol | Yes, No | |

| Substance use | Smoking | Cigarette use | CD, FO, FD, CO, N, NA |

| Snuff | Snuff use | CD, FO, FD, CO, N, NA | |

| E-cigarette | E-cigarette use | CD, FO, FD, CO, N, NA | |

| Alcohol | Alcohol consumption | Yes, No | |

| Alcohol freq. | Alcohol drink frequency | 2-3 p/w, 4 p/w, ≤ 1 p/m, 2-4 p/m, NA | |

| Alcohol units | # units consumed | 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7-9, ≥ 10, NA | |

| ≥ 6 units | ≥ 6 units of consumed alcohol | D, W, <M, M, N, NA | |

| PA | Strenuous PA | # days of strenuous PA | 0, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7, NA |

| Moderate PA | # days of moderate PA | 0, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7, NA | |

| Walking | # days of walking ≥10 minutes | 0, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7, NA | |

| Daily sitting | # hours sitting on a weekday | 0-2, 3-5, 6-8, 9-11, 12-14, ≥15, NA | |

| Dietary intake | Extra salt | Freq. extra salt added to food | N, OCC, O, A, NA |

| Sugary drinks | # sweetened drinks | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ≥ 7, NA | |

| Fruits/Berries | Fruit servings and berries | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5, NA | |

| Vegetables | Lettuce and vegetable servings | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5, NA | |

| Red meat | # consumed red meat | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5, NA | |

| Other meat | # consumed processed meat | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5, NA | |

| Fish | # consumed fish products | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5, NA | |

| Income | House income | Gross household income | ≤ 150K, 150-350K, 351-550K, |

| 551-750K, 751-1000K, ≥ 1000K, NA | |||

| Household adult | # household members ≥ 18 years | 0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4, NA | |

| Household young | # household members ≤ 18 years | 0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4, NA |

| Method | KLD | HD | MAEP | RSVR | PCD | LCM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMOTEN | 0.092±0.004 | 0.168±0.006 | 0.298±0.014 | 0.609±0.011 | 2.011±0.135 | -8.116±0.407 |

| TVAE | 0.299±0.022 | 0.313±0.013 | 0.590±0.032 | 0.177±0.020 | 3.487±0.320 | -3.926±0.517 |

| CTGAN | 0.017±0.002 | 0.061±0.003 | 0.145±0.006 | 0.001±0.001 | 3.724±0.423 | -6.110±0.235 |

| Method | Balancing Strategy |

Sensitivity (All) | Sensitivity (FS) | AUC (All) | AUC (FS) |

| RUS | Under | 0.711±0.059 | 0.707±0.041 | 0.697±0.025 | 0.706±0.021 |

| SMOTEN | Over | 0.701±0.046 | 0.708±0.054 | 0.701±0.025 | 0.700±0.012 |

| Hybrid | 0.686±0.028 | 0.707±0.014 | 0.694±0.012 | 0.709±0.020 | |

| TVAE | Over | 0.636±0.067 | 0.640±0.013 | 0.650±0.027 | 0.668±0.024 |

| Hybrid | 0.615±0.023 | 0.694±0.041 | 0.661±0.026 | 0.704±0.016 | |

| CTGAN | Over | 0.699±0.044 | 0.695±0.021 | 0.702±0.026 | 0.707±0.017 |

| Hybrid | 0.716±0.043 | 0.709±0.036 | 0.712±0.017 | 0.711±0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).