Submitted:

12 January 2024

Posted:

15 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Biological basics

1.2. Former spatial models

1.3. Aims of this study

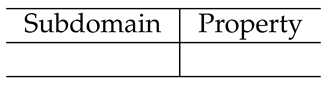

2. Materials, Models and Methods

2.1. Experimental data based unstructured grid geometry

2.2. Laplace Beltrami and tangential space / manifold operators

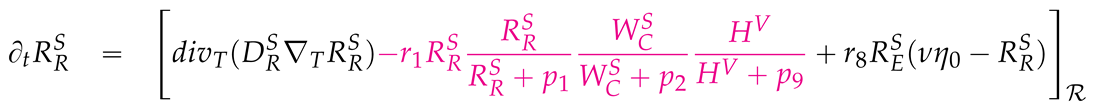

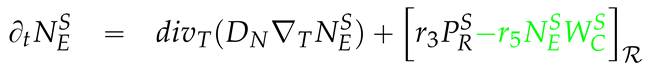

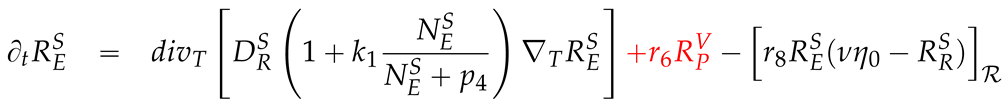

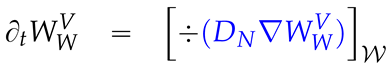

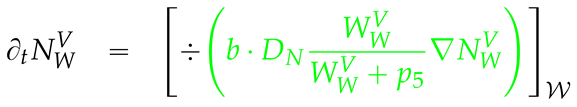

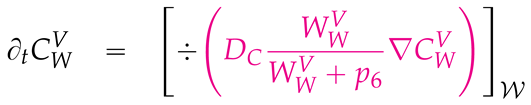

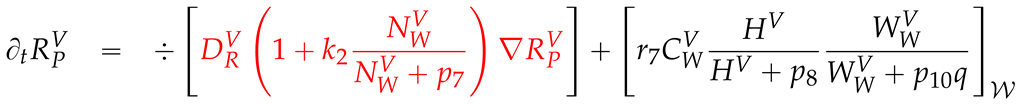

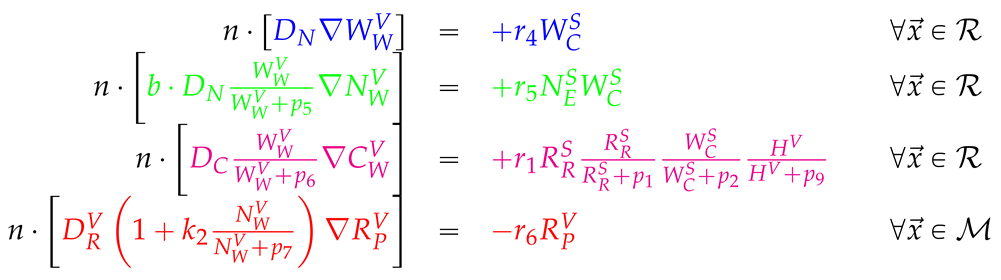

2.3. Mathematical PDE model coupling surface and volume effects

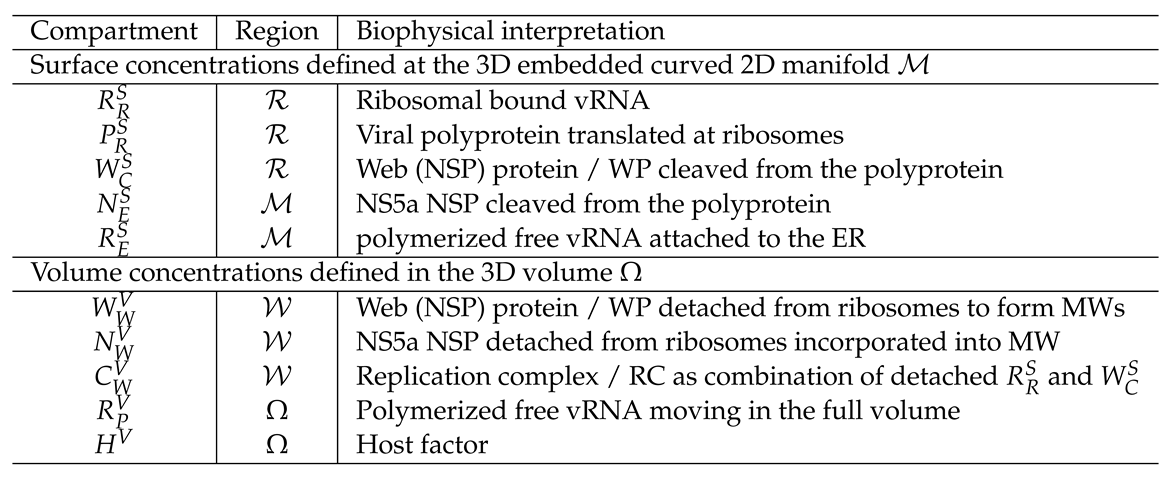

2.4. Numerical values of the model parameters

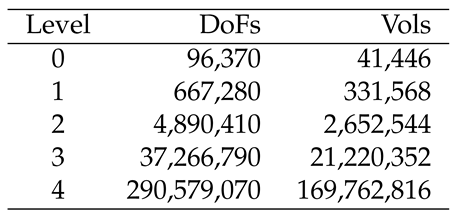

2.5. Numerical solution techniques to solve the sufPDE/PDE system

2.6. Integrals of concentrations over subdomains

2.7. Distinguing between geometrically defined and biophysically active MW zones

3. Results

3.1. Geometric basis and geometric vs. biophysical subdomains

3.2. Spatial simulation data evaluation – simulation movie

3.2.1. Concentrations and their spatial regions

3.2.2. In silico microscope of vRNA cycle

Ordering of all simulation screenshots

- A

- Ribosomal bound vRNA (“vRNA ribo”) on the ribosomal zones of the ER surface and RC in the MWs.

- B

- Polyprotein on the ribosomal zones of the ER surface.

- C

- WP at the ribosomal zones of the ER surface and in the MW zones.

- D

- Free vRNA in the volume and at the ER surface.

- E

- NS5a on the ribosomal zones of the ER surface and in the MWs.

- F

- Host factor overall in the volume.

Initial state - one vRNA attached to one ribosomal zone

Viral protein production, movement, and MW zone activation

vRNA polymerization and propagation

Closing the vRNA cycle

Illumination of MW spots like a domino effect

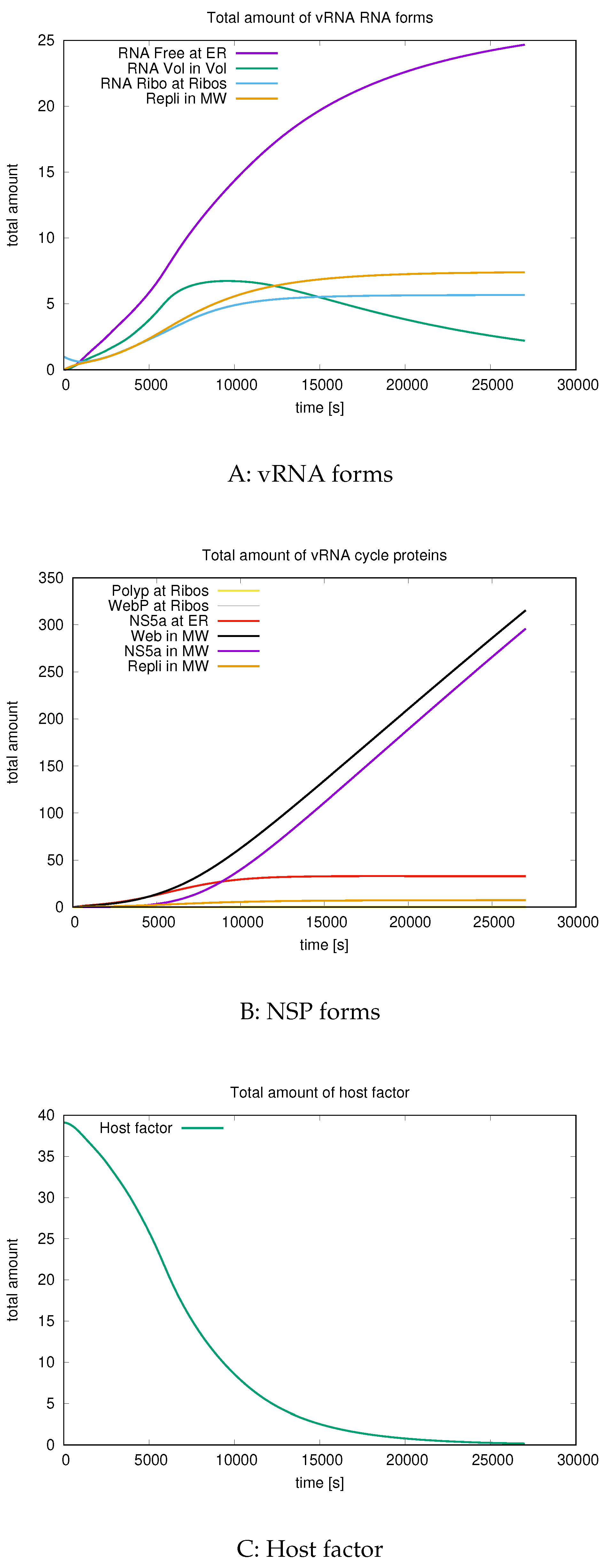

3.3. Quantitative data evaluations

3.4. Mass conservation along exchange between manifold and volume

4. Discussion

4.1. Model components and their respective spatial dynamics

4.2. ER surface remodelling / MW zones establishment

4.3. vRNA movement and location

4.4. Replication complex and cis condition

4.5. Nonlinear diffusion and reaction coefficient structure

4.6. Comparison to quantitative experimental data

4.7. Quantitative model validation

4.8. Relation form and function

4.9. Qualitative model properties

4.9.1. Summary - in silico microscope

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDE | partial differential equation |

| sufPDE | surface PDE |

| GMG | geometric multi grid |

| SLE | system of linear equations |

| ER | endoplasmatic reticulum |

| MW | membranous web |

| FRAP | fluorescence recovery after photobleaching |

| vRNA | viral RNA |

| NSP | non structural protein |

| SP | structural protein |

| WP | Web Protein |

| NS5a | HCV NSP # 5a |

| NS5B | HCV NSP # 5B |

| RC | Replication Complex |

References

- Bakrania, S.; Chavez, C.; Ipince, A.; Rocca, M.; Oliver, S.; Stansfield, C.; Subrahmanian, R. Impacts of Pandemics and Epidemics on Child Protection: Lessons learned from a rapid review in the context of COVID-19. Innocenti Working Paper 2020-05, UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti, Florence. 2020.

- COVID-19 strategic preparedness and response plan: Monitoring and evaluation framework. Geneva: World Health Organization; (WHO/WHE/2021.07), Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2021.

- 2021 Mid-Year Report: WHO Strategic action against COVID-19. Geneva: World Health Organization; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO 2021.

- Scoping review of interventions to maintain essential services for maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and older people during disruptive events. Geneva: World Health Organization; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO 2021.

- Global Hepatitis Report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2017.

- Organization., W.H. WHO Strategic Response Plan: West Africa Ebola Outbreak. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, ISBN 978 92 4 150869 8 2015.

- Vkovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, D.; Bartenschlager, R. Architecture and biogenesis of plus- strand RNA virus replication factories. Wo. J. Vir. 2013, 2, 1-000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, T.; Bühler, S.; Bartenschlager, R. Chronic viral hepatitis and its association with liver cancer. Biol Chem. 2017, 398, 817–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradpour, D.; Penin, F.; Rice, C.M. Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatel-Chaix, L.; Bartenschlager, R. Dengue virus and Hepatitis C virus-induced replication and assembly compartments: The enemy inside - caught in the web. J Virol. 2014, 88, 5907–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Brey, I.; Merz, A.; Chiramel, A.; Lee, J.; Chlanda, P.; Haselman, U.; Santarella-Mellwig, R.; Habermann, A.; Hoppe, S.; Kallis, S. Three-dimensional architecture and biogenesis of membrane structures associated with hepatitis C virus replication. PLoS Path. 2012, 8, e1003056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belda, O.; Targett-Adams, P. Small molecule inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus-encoded NS5A protein. Vir. Res. 2012, 170, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targett-Adams, P.; Graham, E.; Middleton, J.; Palmer, A.; Shaw, S.; Lavender, H.; Brain, P.; Tran, T.; Jones, L.; Wakenhut, F. Small molecules targeting hepatitis C virus-encoded NS5A cause subcellular redistribution of their target: insights into compound modes of action. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 6353–6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.A.; Regal, R.E.; Mohammad, R.A. Daclatasvir: A NS5A Replication Complex Inhibitor for Hepatitis C Infection. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2016, 50, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedj, J.; Rong, L.; Dahari, H.; Perelson, A. A perspective on modelling hepatitis C virus infection. J. Vir. Hep. 2010, 17, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, L.; Guedj, J.; Dahari, H.; Coffield, D.J.; Levi, M.; Smith, P.; Perelson, A. Analysis of hepatitis C virus decline during treatment with the protease inhibitor danoprevir using a multiscale model. PLoS Comp. Biol 2013, 9, e1002959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahari, H.; Guedj, J.; Perelson, A.; Layden, T. Hepatitis C Viral Kinetics in the Era of Direct Acting Antiviral Agents and IL28B. Cu. Hep. Rep. 2011, 10, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahari, H.; Guedj, J.; Perelson, A.; Layden, T. Hepatitis C Viral Kinetics in the Era of Direct Acting Antiviral Agents and IL28B. Curr Hepat Rep. 2011, 10, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churkin, A.; Lewkiewicz, S.; Reinharz, V.; Dahari, H.; Barash, D. Efficient Methods for Parameter Estimation of Ordinary and Partial Differential Equation Models of Viral Hepatitis Kinetics. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahari, H.; Ribeiro, R.; Rice, C.; Perelson, A. Mathematical Modeling of Subgenomic Hepatitis C Virus Replication in Huh-7 Cells. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahari, H.; Sainz, B.; Sainz, J.; Perelson, A.; Uprichard, S. Modeling Subgenomic Hepatitis C Virus RNA Kinetics during Treatment with Alpha Interferon. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6383–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adiwijaya, B.; Herrmann, E.; Hare, B.; Kieffer, T.; C, L. A Multi-Variant, Viral Dynamic Model of Genotype 1 HCV to Assess the in vivo Evolution of Protease-Inhibitor Resistant Variants. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2010, 6, e1000745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, M.; Sulaimanov, N.; Clausznitzer, D.; Schulze, M.; Hüber, C.; Lenz, S.; Schlöder, J.; Trippler, M.; Bartenschlager, R.; Lohmann, V. Replication vesicles are load- and choke-points in the hepatitis C virus lifecycle. PLoS Path. 2013, 9, e1003561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattaf, K.; Yousfi, N. Global stability for reaction-diffusion equations in biology. Computers and Mathematics with Applications 66, 1488–1497. [CrossRef]

- Hattaf, K.; Yousfi, N. A generalized HBV model with diffusion and two delays. Computers and Mathematics with Applications 2015, 69, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattaf, K.; Yousfi, N. A numerical method for delayed partial differential equations describing infectious diseases. Computers and Mathematics with Applications 2016, 72, 2741–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, W. Propagation of HBV with spatial dependence. Math. Biosci. 2007, 210, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Ma, Z. An HBV model with diffusion and time delay, J. Theoret. Biol. 2009, 257, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, N.C.; Avila Vales, E.; Garcia Almeida, G. Analysis of a HBV model with diffusion and time delay. J. Appl. Math. 2012, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z. Dynamics of a diffusive HBV model with delayed Beddington?DeAngelis response. Nonlinear Anal. RWA 2014, 15, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knodel, M.; Reiter, S.; Targett-Adams, P.; Grillo, A.; Herrmann, E.; Wittum, G. 3D Spatially Resolved Models of the Intracellular Dynamics of the Hepatitis C Genome Replication Cycle. Viruses 2017, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knodel, M.M.; Reiter, S.; Targett-Adams, P.; Grillo, A.; Herrmann, E.; Wittum, G. Advanced Hepatitis C Virus Replication PDE Models within a Realistic Intracellular Geometric Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knodel, M.M.; Nägel, A.; Reiter, S.; Rupp, M.; Vogel, A.; Targett-Adams, P.; McLauchlan, J.; Herrmann, E.; Wittum, G. Quantitative analysis of Hepatitis C NS5A viral protein dynamics on the ER surface. Viruses 2018, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiches, G.N.; Eyre, N.S.; Aloia, A.L.; Van Der Hoek, K.; Betz-Stablein, B.; Luciani, F.; Chopra, A.; Beard, M.R. HCV RNA traffic and association with NS5A in living cells. Virology 493, 60–74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targett-Adams, P.; Boulant, S.; McLauchlan, J. Visualization of double-stranded RNA in cells supporting hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Virol. 2008, 82, 2182–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, V. Hepatitis C Virus RNA Replication. In: Bartenschlager R. (eds) Hepatitis C Virus: From Molecular Virology to Antiviral Therapy. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, vol 369. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2013.

- Appel, N.; Herian, U.; Bartenschlager, R. Efficient rescue of hepatitis C virus RNA replication by trans-complementation with nonstructural protein 5A. J Virol, 79, 896–909.

- Knodel, M.M.; Nägel, A.; Reiter, S.; Rupp, M.; Vogel, A.; Targett-Adams, P.; Herrmann, E.; Wittum, G. Multigrid analysis of spatially resolved hepatitis C virus protein simulations. Computing and Visualization in Science 2015, 17, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knodel, M.M.; Nägel, A.; Reiter, S.; Rupp, M.; Vogel, A.; Lampe, M.; Targett-Adams, P.; Herrmann, E.; Wittum, G. High Performance Computing in Science and Engineering 15: Transactions of the High Performance Computing Center, Stuttgart (HLRS) 2015. In High Performance Computing in Science and Engineering 15: Transactions of the High Performance Computing Center, Stuttgart (HLRS) 2015; Nagel, E.W.; Kröner, H.D.; Resch, M.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; chapter On Estimation of a Viral Protein Diffusion Constant on the Curved Intracellular ER Surface, pp. 641–657. [CrossRef]

- Knodel, M.; Nägel, A.; Herrmann, E.; Wittum, G. PDE Models of Virus Replication Coupling 2D Manifold and 3D Volume Effects Evaluated at Realistic Reconstructed Cell Geometries. In: Franck, E., Fuhrmann, J., Michel-Dansac, V., Navoret, L. (eds) Finite Volumes for Complex Applications X Volume 1, Elliptic and Parabolic Problems. FVCA 2023. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, vol 432. Springer, Cham. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Scientific Volume Imaging B.V., Hilversum, N. Huygens comute engine. Software 2014. http://www.svi.nl/HuygensSoftware.

- van der Voort, H.; Brakenhoff, G. 3-D image formation in high-aperture fluorescence confocal microscopy: a numerical analysis. J. Microsc. 1990, 158, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, H.; van der Voort, H.; Schrader, M.; van Kempen, G.; SW, H. Avalanche photodiode detection with object scanning and image restoration provides 2-4 fold resolution increase in two-photon fluorescence microscopy. Bioimag. 1996, 5, 87–197. [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen, G.; van der Voort, H.; van Vliet, L. A quantitative comparison of two restoration methods as applied to confocal microscopy. J. Microsc 1997, 185, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungblut, D.; Queisser, G.; Wittum, G. Inertia Based Filtering of High Resolution Images Using a GPU Cluster. Comp. Vis. Sci. 2011, 14, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, S. Effiziente Algorithmen und Datenstrukturen für die Realisierung von adaptiven, hierarchischen Gittern auf massiv parallelen Systemen. PhD thesis Univ. of Frankfurt 2015.

- Reiter, S.; Wittum, G. Promesh - a flexible interactive meshing software for unstructured hybrid grids in 1, 2 and 3 dimensions. CVS 2028. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, S.; Wittum, G. 2017. http://promesh3d.com/.

- Di Stefano, S.; Carfagna, M.; Knodel, M.; Hashlamoun, K.; Federico, S.; Grillo, A. Anelastic reorganisation of fibre-reinforced biological tissues. Submitted. 2017.

- Si, H. TetGen. A Quality Tetrahedral Mesh Generator and 3D Delaunay Triangulator. WIAS Tech Rep 13, 2013. http://www.tetgen.org.

- Kühnel, W. Differential Geometry: Curves - Surfaces - Manifolds; American Mathematical Society, 2005.

- Bank, R.E.; Rose, D. Some Error Estimates for the Box Method, SIAM J. Nu. Anal 1987, 24, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackbusch, W. On first and second order box schemes. Computing 1989, 41, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, S.; Vogel, A.; Heppner, I.; Rupp, M.; Wittum, G. A massively parallel geometric multigrid solver on hierarchically distributed grids. Comp. Vis. Sci. 16, 151–164. [CrossRef]

- Knodel, M.; Nägel, A.; Herrmann, E.; Wittum, G. Solving nonlinear virus replication PDE models with hierarchical grid distribution based GMG. in preparation 2024.

- Jones, D.; Gretton, S.; McLauchlan, J.; Targett-Adams, P. Mobility analysis of an NS5A-GFP fusion protein in cells actively replicating hepatitis C virus subgenomic RNA. J. Gen. Vir. 2007, 88, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulla, A.; Randall, G. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Hepatitis C Virus Infection. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11, e1004758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, S. A Model of Leptons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 1264–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groote, S.; Knodel, M. Evaluating massive planar two-loop tensor vertex integrals. Eur. Phys. J. C 2006, 46, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatrchyan, S. Observation of a new boson at a mass of 125 GeV with the CMS experiment at the LHC. Physics Letters B 2012, 716, 30–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, J.; Cutts, F. Yellow fever. Global Programme for vaccines and immunization, World Health Organization, Geneva 1998.

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).