1. Introduction

Global consumption of fertilizer urea in 2023 was 59.25 million tons, while in Brazil, the consumption of this input reached 3.46 million tons [

1]. Nitrogen (N) is the nutrient most demanded by crops and, consequently, the most used in agriculture, predominantly in the form of urea. However, it is also one of the least efficient in terms of soil use, mainly due to losses through volatilization and leaching [

2,

3,

4]. These N losses can range from 20% to 70%, depending on the soil's chemical and physical attributes, such as cation exchange capacity and clay content, respectively [

5].

Despite its low efficiency, food production is highly dependent on nitrogen fertilization. This dependence is even greater in semi-arid regions, where organic matter levels – the main natural source of nitrogen in the soil – are low or very low [

6,

7]. The inadequate application of N in agriculture, however, causes negative environmental impacts, directly or indirectly, as a result of leaching and volatilization processes [

4].

After application to the soil, nitrogen is subject to various processes, such as mineralization (in the case of urea and organic fertilizers), nitrification, leaching, immobilization, and denitrification [

6]. The nitrification process, mediated by bacteria, is responsible for generating nitrate (NO₃⁻), the predominant mineral N form in aerated soils [

8]. In acidic or waterlogged soils, the predominant form is ammonium (NH₄⁺) [

6]. In soils with a low degree of weathering, N losses in the form of NO₃⁻ tend to be higher than in more weathered soils [

4]. This occurs because the former have a higher density of negative charges, which disfavors the adsorption of this anion, increasing its concentration in the soil solution and, consequently, its losses through leaching [

6,

9]. Nitrate leaching represents not only a loss of soil nutrients but also pollution of surface and groundwater. Additionally, the nitrate generated in the soil can be lost to the atmosphere as nitrous oxide (N₂O) gas through the denitrification process, which occurs in reducing environments [

10].

One strategy to mitigate N losses through leaching and volatilization is to delay or suppress the generation of NO₃⁻ by inhibiting the nitrification process [

11,

12]. Several effective synthetic nitrification inhibitors are available on the market, such as nitrapyrin, dicyandiamide (DCD), and dimethylpyrazole phosphate (DMPP) [

11,

13]. However, the high cost of these products often makes their use unfeasible, and their effects are not always consistent.

Alternatively, coating urea with metals such as boron, copper, iron, and zinc has shown promise in increasing the efficiency of nitrogen use by plants and increasing crop productivity [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Coating urea with CuO, ZnO, and NiO, with particles of about 44 µm at a rate of 0.8%, resulted in a significant reduction in N losses through volatilization and a higher mineral N content in the soil [

16]. Urea coated (261 kg ha⁻¹) with a combination of 2.0% FeSO₄·7H₂O and 2.9% ZnSO₄·H₂O decreased N losses through volatilization and increased the efficiency of N use in onion bulb production [

18]. It is presumed that these metals act by inhibiting the urease enzyme, responsible for the hydrolysis of urea into ammonium, thus reducing the generation of ammonia and its subsequent volatilization [

18,

19].

Other authors have investigated the potential of zinc oxide nanoparticles as a coating for urea granules, aiming to delay the release of N in the soil and increase its efficiency [

13,

20,

21,

22,

23]. In this context, Thabit [

13] observed that urea coated with 3% zinc oxide nanoparticles reduced mineral N losses by 22% and nitrate levels up to the eighth day of incubation in a clay-sandy soil. Furthermore, coating urea with nanoparticles containing micronutrients can improve crop performance through better utilization of micronutrients such as zinc and iron [

20]. These effects are particularly beneficial in soils with low clay content, where the leaching of nitrate and ammonium promotes significant N losses [

9,

21,

24].

This study sought to address a fundamental gap by investigating the synergistic effects of coating urea with a combination of iron oxide nanoparticles (NPFe₂O₃) and zinc oxide nanoparticles (NPZnO) associated with elemental sulfur, aiming not only to reduce nitrogen leaching in sandy soil but also its impact on the performance and nitrogen use efficiency in corn plants, an aspect still scarcely explored in the literature.

Given the above, the present work aimed to evaluate the influence of coating urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles, associated with elemental sulfur, on the leaching of mineral nitrogen, and on the production of dry mass and accumulation of N in young corn plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Experiments

Two experiments were conducted in a greenhouse belonging to the Center for Technology and Natural Resources at the Federal University of Campina Grande, from March 26 to May 9, 2024, located at coordinates -7.21483°, -35.90653° and an altitude of 551 m.

The first experiment consisted of evaluating the influence of coating fertilizer urea with iron oxide nanoparticles, zinc oxide nanoparticles, and elemental sulfur on the leaching of ammonium and nitrate in a sandy soil. The second experiment evaluated the effect of the coated urea on biomass production and nitrogen accumulation in young corn plants.

2.2. Obtaining the Coated Urea

Commercial granular urea, containing 46% N, was used as the N source. For the urea coating, zinc nanoparticles, iron nanoparticles, elemental sulfur, and a binding agent were used. As the ZnONP source, zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles (product code 544906-10G, batch number MKCP6471, CAS-No 1314-13-2) from Sigma Aldrich® (Sigma-Aldrich®Co Ltd, Darmstadt, Germany) were used, with 97% purity, particle size <100 nm, and a specific surface area of 10.8 m² g⁻¹. As the Fe₂O₃NP source, iron oxide (Fe₂O₃) nanoparticles (product code 544884-5G, batch number MKCS3534, CAS-No 1309-37-1) from Sigma-Aldrich® (Sigma-Aldrich®Co Ltd, Darmstadt, Germany) were used, with 98% purity, particle dimensions <50 nm, and an average specific surface area of 50–245 m² g⁻¹. Commercial elemental sulfur 99S, containing 99% S (Heringer® Fertilizers, Rio Grande, Brazil), and canola vegetable oil as a binding component were used.

The urea coating method was based on Dimkpa et al. [

20] with minor adjustments in the proportion of components used. The urea particle size was standardized by sieving to sizes between 2.5 mm and 3 mm. Before weighing, the NPZnO and NPFe₂O₃ were dried in an oven at 60 °C to 70 °C. Subsequently, a coating paste for the urea granules was prepared by adding into a 200 mL beaker: 0.35 mL of canola vegetable oil (LIZA®, Bunge Foods Co Ltd, São Paulo, Brazil), 1.75g of elemental sulfur, 0.175g of NPZnO, and 0.175g of NPFe₂O₃. The components were mixed manually using a glass rod until a homogeneous paste was formed. Then, 27.17g of standardized granulometry urea was added to the obtained paste to form the coating. For the control urea, a coating was prepared using only 0.35 mL of canola vegetable oil. Both mixtures (urea plus paste) were transferred to a digital orbital shaker at 32 rpm where they remained for 12 hours to cure the formed coating. This resulted in the nanoparticles-coated urea and the control urea. After the curing process, the coated urea was weighed again to obtain the percentage of coating mass (0.26%) compared to the initial urea mass.

2.3. Experiment with Mineral Nitrogen Leaching

2.3.1. Experiment Setup

The test soil for the experimental assay was collected from the 0-20 cm layer, samples of a Regolithic Neosol (Entisol), considering it is a soil with low levels of organic matter and nitrogen and susceptible to mineral nitrogen leaching. After being air-dried, crushed, and passed through a 2.0 mm mesh sieve, the samples were sent for their chemical and physical characterization (

Table 1) according to procedures described in Embrapa [

25].

The experiment consisted of a completely randomized design in a 4 × 6 factorial scheme, comprising four treatments: 0N- No nitrogen as control, T2- 500 mg N dm⁻³ as conventional urea (U), T3: 500 mg N dm⁻³ as urea (Heringer® Fertilizers, Rio Grande, Brazil) coated with elemental sulfur (U+S°), T4-500 mg N dm⁻³ as urea coated with NPZnO + NPFe₂O₃ and elemental sulfur (U+S°+NP), and six evaluation periods (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 days after incubation) with 5 replications. Each experimental unit consisted of a pot containing 5 dm³ of soil.

A drain was inserted at the base of each pot to collect leachate resulting from the irrigation process. The urea granules were placed in the soil of the pots at a depth of 5 cm, distributed in a circle. Subsequently, the soil in the pots was maintained at a moisture level corresponding to 70% of field capacity, according to the water retention curve (

Table 1). This moisture level was maintained through daily weighings using a digital scale with a capacity of 10 kg and appropriate precision (LS10 MARTE, Marte Scales and Weighing Instruments Ltd, São Paulo, Brazil). During the incubation period, air temperature and relative humidity data were recorded (

Figure 1).

2.3.2. Mineral Nitrogen Leaching Analysis

At each evaluation period, a volume of water was applied to achieve a volume corresponding to twice the soil's field capacity. After drainage ceased, the volume of leachate was collected and measured. Subsequently, a 50 mL aliquot of the leachate was taken, to which 5 mL of a 3.0 mol L⁻¹ KCl solution was added, and then stored in a refrigerator.

In the leachate samples collected each period, the levels of ammonium (N-NH₄⁺) and nitrate (N-NO₃⁻) were determined using the Kjeldahl nitrogen micro-distillation method (Marconi Co Ltd., Londrina, Brazil), as described by Tedesco et al. [

26]. According to this method, 0.2g of calcined MgO (Vetec Fine chemistry Co Ltd., Duque de Caxias, Brazil) was initially added to each distillation tube. After distillation, the ammonium levels were obtained by titration with 0.01 mol L⁻¹ HCl, after being collected in flasks containing boric acid indicator. Nitric nitrogen was determined using the same extract (the same tube) used for ammonium distillation, by adding 0.2g of Devarda's alloy (Vetec Fine chemistry Co Ltd., Duque de Caxias, Brazil) and proceeding to a new distillation. The distillate was then titrated with the same acid used for ammonium. Using the concentrations of ammonium and nitrate in the leachate and the leachate volume, the quantities of leached mineral nitrogen (nitrate + ammonium) for each collection period and the ammonium/nitrate ratio were calculated.

2.3.3. Initial Growth and Nitrogen Uptake by Young Corn Plants

To evaluate the fertilizer efficiency in terms of plant nitrogen utilization, an experiment was conducted in a greenhouse using a completely randomized design, comprising four treatments: 0N- No nitrogen as control, T2- 300 mg N dm⁻³ as conventional urea (U), T3: 300 mg N dm⁻³ as urea coated with elemental sulfur (U+S°), T4-300 mg N dm⁻³ as urea coated with NPZnO + NPFe₂O₃ and elemental sulfur (U+S°+NP), with 6 replications totaling 24 experimental units. Each experimental unit consisted of a pot containing 5 dm³ of soil.

Corn was used as the test plant due to its rapid growth and high nutrient extraction capacity. The genotype used was the green corn hybrid with VT PRO 3 technology, BM 3066 (DEKALB/Biomatrix, Bayer® Co Ltd, São Paulo, Brazil), one of the preferred choices of most producers in the Northeast region for green corn and/or silage production. After placing the soil in the pots, the treatments were applied to each pot, followed by irrigation and sowing, placing 3 seeds per pot. After seedling emergence, thinning was performed, leaving one plant per pot.

All pots received a baseline fertilization with macro and micronutrients (except N, Fe, and Zn, which were applied according to the treatments) based on Marcelino et al. [

27] with the following doses in mg dm⁻³: P = 200; K = 300; Ca = 200; Mg = 50; S = 50; B = 0.5; Cu = 1.5; Mn = 4; Mo = 0.15. The following p.a. reagents were used for this fertilization: KH₂PO₄ (monopotassium phosphate), KCl (potassium chloride), calcium phosphate [Ca(H₂PO₄)₂·2H₂O], magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄·7H₂O), boric acid (H₃BO₃), copper sulfate (CuSO₄·5H₂O), manganese sulfate (MnSO₄·4H₂O), and ammonium molybdate [(NH₄)₆Mo₇O₂₄·H₂O]. All sources used were from Vetec (Vetec Fine chemistry Co Ltd., Duque de Caxias, Brazil). Throughout the experimental period, the soil was maintained at 70% of field capacity. Moisture control was performed daily by weighing, using distilled water to replenish water loss. The plants remained in the greenhouse for 45 days after thinning. Subsequently, they were harvested and separated into shoots and roots, which were dried in a forced air circulation oven (SL-102/1575, SOLAB® Co Ltd., Piracicaba, Brazil) at 60 °C to 65 °C to obtain the leaf dry mass (LDM), stem dry mass (CDM), and root dry mass (RDM), and by their sum, the total dry mass (TDM). In the leaf and stem dry mass, the total nitrogen content was determined according to the methodology described in Tedesco et al. (1985). In this analysis, 0.1g of plant tissue was digested in 3 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid in a digestion block at 350ºC, followed by distillation in a Kjeldahl micro-distiller (Marconi Co Ltd., Londrina, Brazil) and subsequent titration. Using the total N content and the produced dry mass, the quantities of this nutrient accumulated in the leaves, stems, and shoots (leaves + stems) were estimated. Based on the N accumulated in the shoots and the respective dry mass production, the nitrogen utilization efficiency (NUE) was calculated using the following expression proposed by Siddiqi and Glass [

28]:

Where SDM corresponds to the shoot dry mass (g/pot) and Nac is the amount of N accumulated in the shoots (stem + leaves) in mg/pot.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

The data were initially subjected to the Shapiro-Wilk normality test [

29]. The obtained data were subjected to analysis of variance, followed by comparison of means using Tukey's test (p ≤ 0.05). These statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software [

30].

3. Results

3.1. Mineral Nitrogen Leaching Experiment

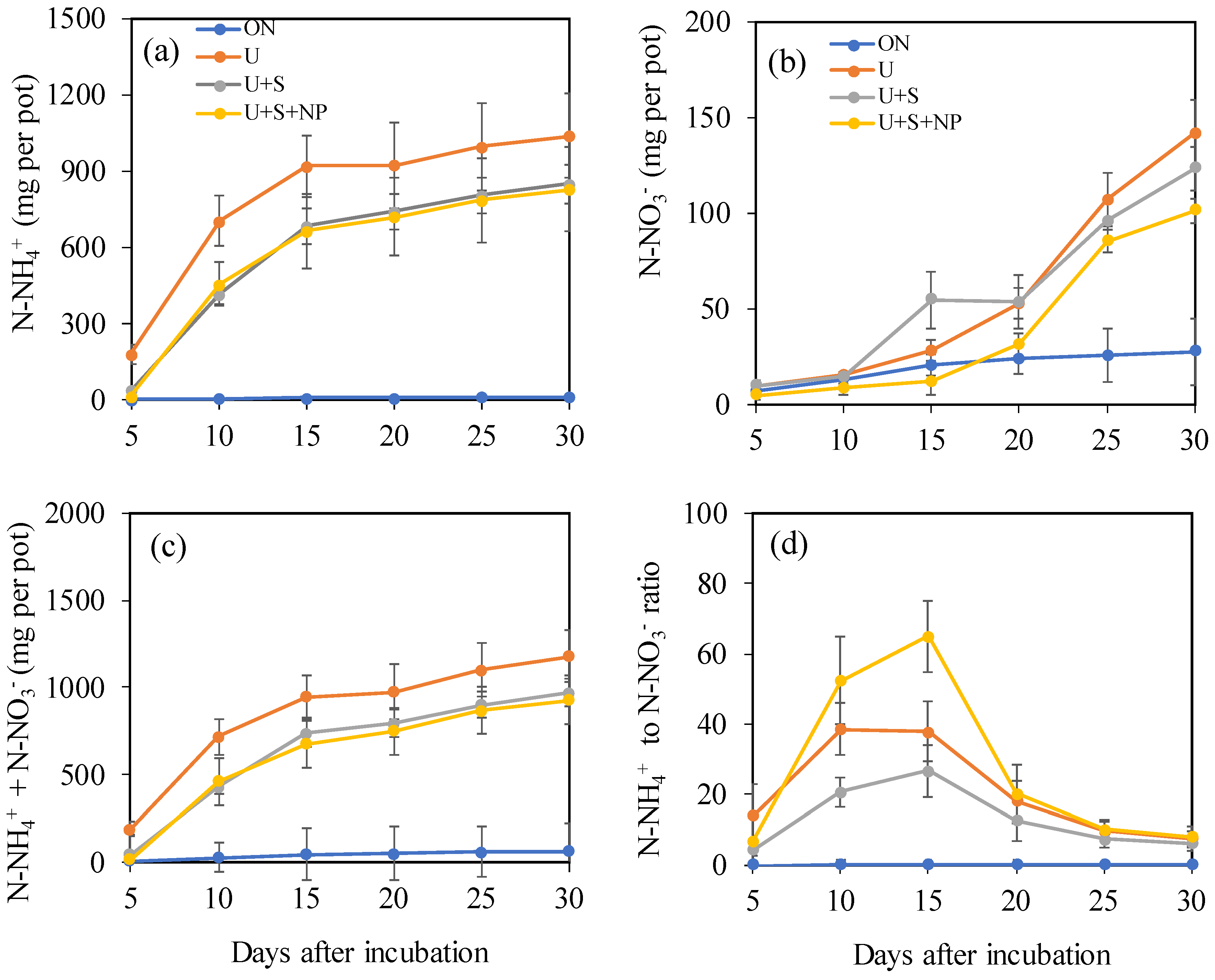

Over the 30-day incubation period, the cumulative amount of ammonium (N-NH₄⁺) in the leachate was practically zero in the control treatment. In contrast, under the application of N at a rate of 500 mg N dm⁻³, the accumulated amounts varied according to the type of urea coating (

Figure 1a).

The leached ammonium quantity tended to stabilize at 30 days after the start of incubation (DAI) and corresponded to 41.5% of the applied N (2,500 mg per pot) for the uncoated urea (U). The lowest values were obtained with urea coated with elemental sulfur (U+S) and urea coated with iron oxide NPs + zinc oxide NPs (U+S+NP). At 10 DAI, the leached N-NH₄⁺ quantities in the U, U+S, and U+S+NP treatments corresponded to 67.8%, 49.0%, and 55.1%, respectively, of the total accumulated by 30 DAI. By the end of the 30 DAI period, coating urea with sulfur (U+S) and with sulfur plus NPs (U+S+NP) reduced ammonium leaching by 18.2% and 20.3%, respectively, compared to uncoated urea.

In contrast to the pattern observed for N-NH₄⁺, the cumulative quantities of nitrate (N-NO₃⁻) were small up to 20 DAI and increased suddenly at 25 and 30 DAI, showing a tendency to increase further from this period onward (

Figure 1b). At 30 DAI, the U+S and U+S+NP treatments reduced N-NO₃⁻ leaching by 12.7% and 28.4%, respectively, compared to conventional urea (

Figure 1c). Consequently, the U+S and U+S+NP treatments decreased total mineral N leaching by 17.6% and 21.3%, respectively.

The N-NH₄⁺/N-NO₃⁻ ratio reached its maximum at 15 DAI and declined sharply by 30 DAI (

Figure 1d). At 15 DAI, the NP-coated urea (U+S+NP) increased the proportion of ammonium in the mineral N by 71.8% compared to conventional urea, indicating a significant retardation of the nitrification process.

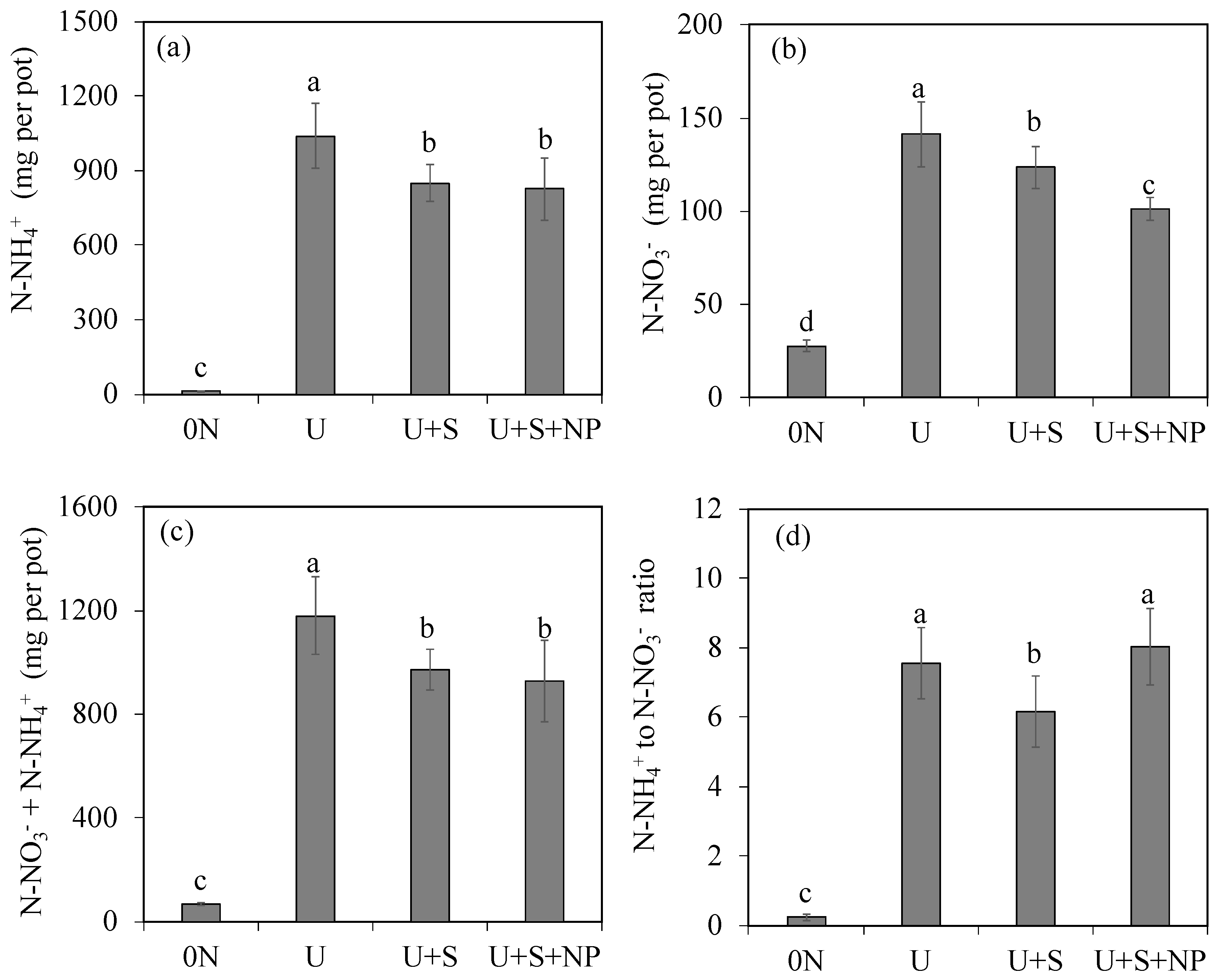

According to the analysis of variance, at the end of 30 days after the start of the nitrogen source incubation, the urea coating treatments differed significantly from each other regarding the accumulated amounts of ammonium (NH₄⁺), nitrate (NO₃⁻), NH₄⁺ + NO₃⁻, and the N-NH₄⁺ to N-NO₃⁻ ratio (

Table 2).

At 30 DAI, the amount of leached N-NH₄⁺ was significantly higher in the treatment containing only conventional urea (41.5%). On the other hand, the U+S (33.9%) and U+S+NP (33.0%) treatments resulted in lower values compared to treatment U, but showed no significant difference between each other (

Figure 2a). For N-NO₃⁻, the urea coating with NPs promoted the lowest proportion of leached N compared to both the U treatment and the U+S treatment (

Figure 2b). The quantities of leached mineral nitrogen (N-NH₄⁺ + N-NO₃⁻) at 30 DAI corresponded to 47.2%, 38.9%, and 37.1% of the total N applied to the soil for the U, U+S, and U+S+NP treatments, respectively (

Figure 2c). The U+S and U+S+NP treatments resulted in a lower percentage of mineral N leaching compared to conventional urea, but showed similar effects to each other. At the end of the incubation period, the N-NH₄⁺/N-NO₃⁻ ratio was lowest in the treatment without N application and in the U+S treatment, while the other treatments did not differ from each other (

Figure 2d).

3.2. Dry Mass Production and Nitrogen Uptake by Corn

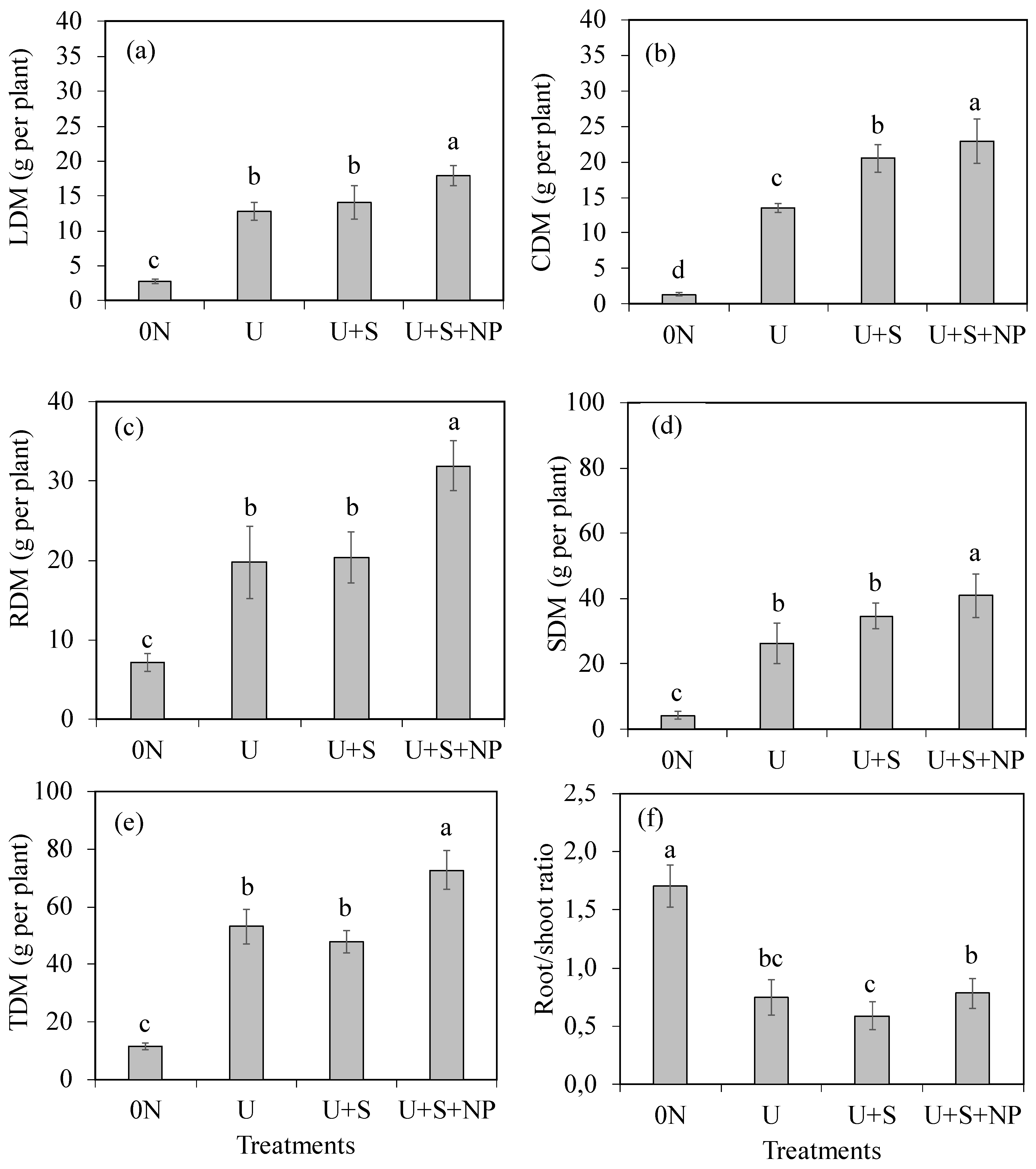

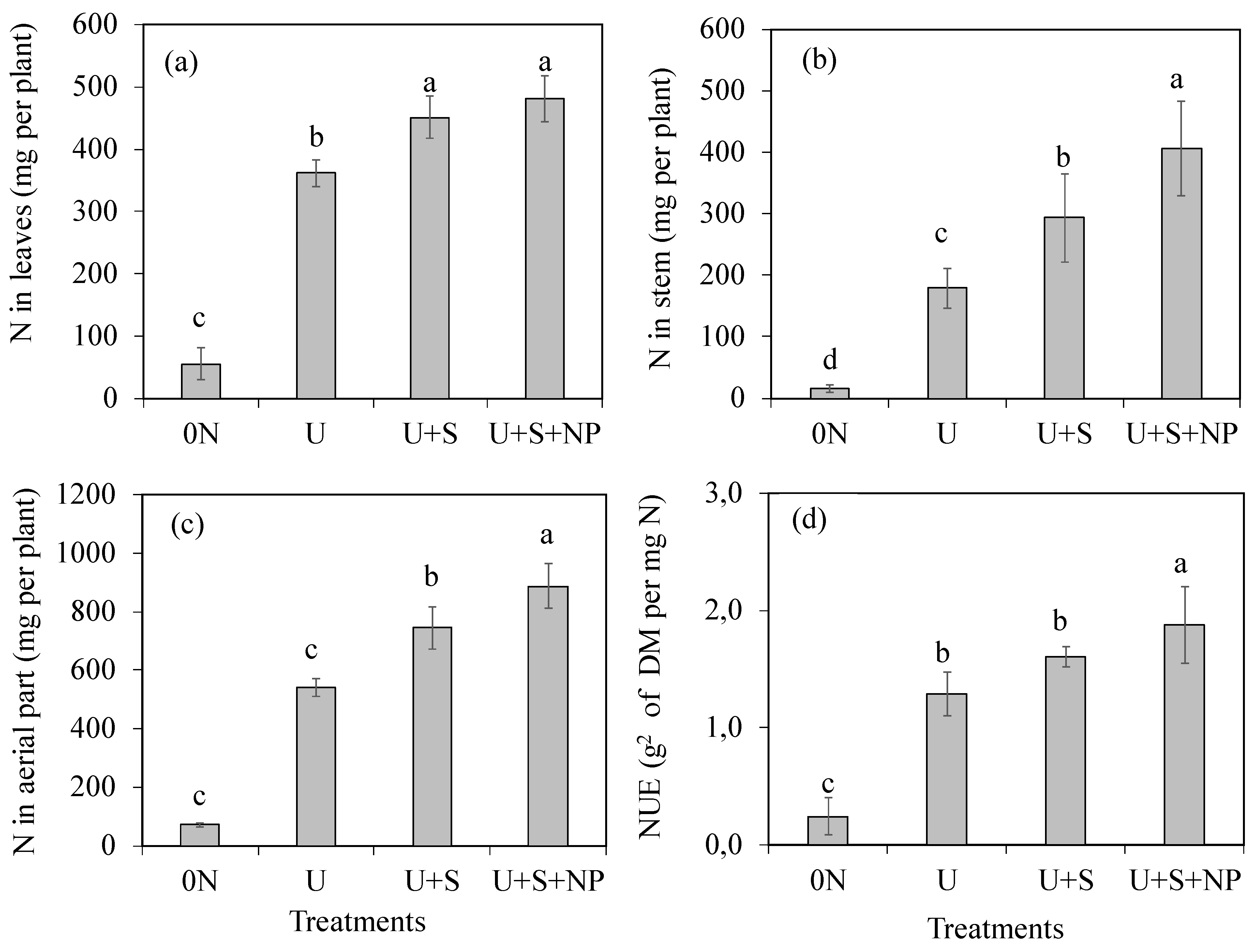

According to the analysis of variance and F-test (

Table 3), the urea coating treatments significantly influenced the production of leaf dry mass (LDM), stem dry mass (SDM), shoot dry mass, and total dry mass (TDM), as well as the root-to-shoot ratio (RDM/SDM). Furthermore, the treatments significantly affected accumulated nitrogen in leaves (N-LDM), stems (N-SDM), shoots (N-SDM), and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE).

The production of leaf dry mass (

Figure 3a), stem dry mass (

Figure 3b), root dry mass (

Figure 3c), shoot dry mass (

Figure 3d), and total dry mass (

Figure 3e) was highest in the U+S+NP treatment. In the 0N treatment, plant growth was severely affected by the lack of soil nitrogen, as demonstrated in the leaching experiment, leading to the lowest dry mass production in all plant parts. Compared to the U treatment, the U+S+NP treatment promoted increases of 39.4%, 68.8%, and 61.6% in leaf, stem, and root dry mass production, respectively. The U and U+S treatments resulted in similar effects on leaf dry mass, root dry mass, shoot dry mass, and total dry mass, but differed in stem dry mass production.

The root-to-shoot ratio (

Figure 3f) was highest in the 0N treatment and lowest in the U+S treatment. The U and U+S+NP treatments showed similar effects on the root-to-shoot ratio, and did not differ significantly from each other in this aspect. The lack of soil nitrogen increased the root-to-shoot ratio by 2.4 times compared to plants that received the 300 mg N dm⁻³ dose.

The accumulated quantities of N in the leaves (

Figure 4a) were higher in the U+S and U+S+NP treatments, which did not differ significantly from each other. These treatments increased nitrogen accumulation in the leaves by 33.2%. The U+S+NP treatment resulted in the highest quantities of accumulated N in the stem dry mass (

Figure 4b) and in the shoots (leaves + stems) (

Figure 4c), with increases of 126.6% and 64.1%, respectively, compared to the uncoated urea treatment. Similarly, the U+S+NP treatment promoted the highest nitrogen use efficiency index (NUE) (

Figure 4d), followed by the U and U+S treatments, which did not differ significantly from each other.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mineral Nitrogen Leaching

Nitrogen (N) losses through volatilization and leaching in sandy soils represent a major constraint on agricultural production, especially for demanding crops like corn. Uncoated urea (U) resulted in the leaching of 41.5% of the applied N. Nitrogen losses exceeding 50% have commonly been reported in the literature [

13,

19], particularly in sandy soils [

31,

32]. Coatings with sulfur (U+S) and sulfur plus NPs (U+S+NP) reduced N-NH₄⁺ losses by 18.2% and 20.3%, respectively, compared to uncoated urea. This indicates that elemental sulfur was probably the main factor responsible for reducing the leaching of this cation, likely by decreasing the urea mineralization rate, leading to a lower rate of ammonium generation in the soil [

33,

34]. Coating urea granules with elemental sulfur acts as a barrier to urease activity – which catalyzes urea hydrolysis – thereby reducing its activity and losses of mineral nitrogen [

35].

Nitrate (N-NO₃⁻) leaching was low until 20 days, increasing suddenly thereafter. Coating urea with S and S+NP decreased nitrate losses by 12.7% and 28.4%, respectively. The oxidation process of elemental sulfur (S) occurs mainly through the action of bacteria of the genus Acidithiobacillus [

36], which oxidize S to SO₄²⁻ and, after reaction with H⁺ from water hydrolysis, produce sulfuric acid, reducing soil pH [

37,

38]. The acidification of the soil solution due to this process certainly inhibited the nitrification of ammonium, reducing its leaching [

39]. The addition of zinc oxide nanoparticles, along with S, contributed to inhibiting the nitrification process of urea-N, thus decreasing its leaching losses, as observed by Jadon et al. [

19]. Reduced N losses from the addition of metals in urea coatings have been observed in other studies [

16,

19,

21]. This result indicates that, contrary to the findings of Yang et al. [

18], the NPs did not act as a urease inhibitor but enhanced the nitrification inhibition process provided by elemental sulfur. In flooded rice soil, urea coated with Zn or Zn+Cu was more effective than sulfur in reducing nitrate generation and consequently N losses through denitrification [

13,

40]. The addition of only 0.5 mg Zn L⁻¹ in drinking water was sufficient to inhibit nitrification [

41]. Indeed, metals like Zn and Cu effectively inhibit the nitrogen nitrification process [

16]; however, the fundamental mechanisms of how these metals affect the activity of enzymes and groups of microorganisms (genera Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter) involved in these processes require further study.

The 21% reduction in leached mineral nitrogen (N-NH₄⁺ + N-NO₃⁻) at 30 DAI, due to coating urea with S+NP compared to conventional urea, although modest, indicates that this coating can effectively contribute to more efficient management of nitrogen fertilization using urea as an N source, helping to increase nitrogen fertilization efficiency [

42].

4.2. Dry Mass Production and Nitrogen Uptake by Young Corn Plants

The growth and development of young corn plants, especially high biomass and grain-yielding varieties like corn, are highly dependent on nitrogen fertilization [

1,

10]. After 45 days of cultivation, there was a drastic reduction (78.5%) in the dry mass production of young corn plants without nitrogen fertilization compared to the treatment receiving 300 mg N dm⁻³ as conventional urea (U). Nitrogen is an essential constituent of proteins, nucleotides, and nucleic acids DNA and RNA [

43,

44]. Low N availability also results in a lower photosynthetic rate due to the breakdown of thylakoid membranes, affecting light energy capture and, consequently, carbon fixation and plant growth and development [

44,

45]. The increase in the root-to-shoot ratio under N deficiency observed in this study is a typical plant response to N stress [

45,

46,

47]. Under N deficiency, both shoots and root systems are negatively affected [

46,

47,

48]. Although the increase in the root-to-shoot ratio is also associated with soil clay content [

48], under N deficiency, plants appear to prioritize root development at the expense of shoots, mediated by increased hormonal flux from shoots to roots [

45,

49].

On the other hand, the U+S+NP treatment promoted increases of 54.5% in shoot dry mass (leaves + stems) and 36% in total dry mass compared to conventional urea. Coating urea with Zn sources has increased the growth and yield of wheat [

20,

22] and rice [

50], and with Zn and Fe sources in onion [

17]. Adding Zn and Fe to urea seems to make fertilization with these micronutrients more efficient than when using conventional sources of these nutrients [

20,

51]. In younger soils under semi-arid climates, these micronutrients become unavailable to plants due to precipitation processes and eventually leaching in sandy soils with low organic matter content [

6,

7,

52]. In this sense, urea and elemental sulfur have acidic reactions that help prevent this precipitation process and keep these nutrients in forms available to plants [

36,

37].

Compared to conventional urea, urea coated with S+NP promoted a significant increase (64.1%) in N accumulation in the shoots of young corn plants, but coating urea with S alone (U+S) had an effect similar to uncoated urea. Coating urea with Zn+Fe, as well as CuO, ZnO, and NiO, decreased N volatilization as NH₃ in other studies [

16,

18]. In the present study, considering that irrigation was controlled to prevent leaching losses in the corn cultivation experiment, this indicates that coating urea with S+NP may have reduced volatilization losses, increasing the efficiency of nitrogen fertilization. Alternatively, it can also be considered that the addition of Zn and Fe in NP form may have increased the N uptake capacity of young corn plants. Iron and Zn are fundamental micronutrients in plant nutrition. The addition of 500 mg N dm⁻³ coated with Fe and Zn corresponded to an application in the soil of 5.7 mg Zn dm⁻³ and 5.0 mg Fe dm⁻³. Iron acts in cellular processes such as respiration, chlorophyll biosynthesis, and photosynthesis, in addition to serving as a cofactor for enzymes related to electron or oxygen transfer processes [

53,

54,

55,

56], while Zn acts in cell division, ribosome stabilization, structural and functional integrity of membranes, and participates in growth regulation processes (tryptophan synthesis) and enzymatic activation [

57,

58,

59].

The findings of this work reveal that coating urea with zinc oxide and iron oxide nanoparticles associated with elemental sulfur constitutes an important strategy for increasing the efficiency of nitrogen fertilization with urea and supplying micronutrients to plants [

60,

61,

62]. The modest yet significant reduction in mineral N leaching losses and the substantial increase in dry mass production and N accumulation in corn shoots demonstrate the potential of this technology for more sustainable nitrogen management, especially in sandy soils. However, there is a need to validate these benefits under diverse field conditions and in the long term, as well as to evaluate the bioavailability of Fe and Zn applied to the soil in this NP form, aiming to consolidate its application on a commercial scale as a robust tool for the sustainable intensification of agriculture.

5. Conclusions

Coating urea with elemental sulfur (S⁰) and zinc oxide nanoparticles (NPZnO) and iron oxide nanoparticles (NPFe₂O₃) decreased nitrogen (N) losses through leaching and delayed the nitrification process of N in the soil. This coating increased the efficiency of nitrogen fertilization in young corn plants, enhancing shoot and root dry mass production and N uptake in the above-ground biomass compared to conventional urea. The use of urea coated with NPZnO and NPFe₂O₃ associated with S⁰ could become a practical and promising solution for supplying N and micronutrients like Fe and Zn in a more efficient and sustainable manner, especially in sandy soils poor in organic matter. Despite the promising results of this study under controlled conditions, validation on a commercial scale requires comprehensive field studies. These future investigations should examine nitrogen dynamics and, crucially, the actual bioavailability of zinc and iron for plants, in the NP form, supplied together with urea, under different edaphoclimatic conditions, soil types, and agricultural cropping systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.A.R. and C.F. de O.; methodology, J.L.A.R and R.H.C.R.A.; software, A.P.S.; validation, J.L.A.R.; formal analysis, R. da S.N.; investigation, R. da S.N and S. dos S.C.; resources, J.L.A.R.; data curation, C.F. de O. and T.F.L.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R. do N.; writing—review and editing, J.L.A.R.; visualization, F.V. da S.S.; supervision, J.L.A.R.; project administration, J.L.A.R.; funding acquisition, J.L.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FAPESQ (Foundation to support research in the state of Paraíba), Fapesq/PB Edital Universal 09/2021 SEECT/Fapesq. grant number 3071/2021.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the Instituto Nacional do Semiárido, INSA/MCT for laboratory support for plant material analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IFA - International Fertilizer Association. Ifastat-Database and charts. 2023. Available at: https://api.ifastat.org/reports/download/12620.

- Kumar, Y.; et al. Nanofertilizers and their role in sustainable agriculture. Ann. Plant Soil Res. 2021, 23, 238-255. [CrossRef]

- Kubar, M.S.; et al. Nitrogen fertilizer application rates and ratios promote the biochemical and physiological attributes of winter wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1011515. [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Sanclemente, W.; Perez-Castillo, A.G.; Monge-Muñoz, M.; Chinchilla-Soto, C.; Chavarría-Pérez, L.; Alpízar-Marín, M.; Zaman, M. Impact of urease inhibitor on greenhouse gas emissions and rice yield in a rainfed transplanting rice system in Costa Rica. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1518802. [CrossRef]

- Wesołowska, M.; et al. New slow-release fertilizers-economic, legal and practical aspects: a Review. Int. Agrophys. 2021, 35, 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafez, A.A.; Abbas, M.H.H.; Attia, T.M.S.; El Bably, W.; Mahrous, S.E. Mineralization of organic carbon and nitrogen in semi-arid soils under organic and inorganic fertilization. Environ. Technol. Innovation, 2018, 9, 243-253. [CrossRef]

- Santos, U.J.; Sampaio, E.V.S.B.; Andrade, E.M. et al. Nitrogen Stocks in Soil Classes Under Different Land Uses in the Brazilian Semiarid Region. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 1621–1630 . [CrossRef]

- Rutting, T.; Aronsson, H.; Delin, S. Efficient use of nitrogen in agriculture. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2018, 110, 1–5. doi.org/10.1007/s10705-017-9900-8.

- Prado, J.; Alvarenga, P.; Ribeiro, H.; Fangueiro, D. Nutrient Potential Leachability in a Sandy Soil Amended with Manure-Based Fertilizers. Agronomy 2023, 13, 990. [CrossRef]

- Udvardi, M.; et al. A research road map for responsible use of agricultural nitrogen. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 660155. [CrossRef]

- Zhou; et al. Effects of commonly used nitrification inhibitors—dicyandiamide (DCD), 3,4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate (DMPP), and nitrapyrin—on soil nitrogen dynamics and nitrifiers in three typical paddy soils. Geoderma 2020, 380, 114637. [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y. The Development of Urease-coated Inhibitor Synergistic Urea and its Effect on Wheat Growth. J Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 4325–4337. [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, I.P.; Cassim, B.M.A.R.; Brasil, P.H.E.; Pereira, F.L.; Prestes, C.V.; Carvalho, H.W.P.; Lavres, J.; Bendassolli, J.A.; Otto, R. J. Soil Sci Plant Nutrition 2024, 24, 6962–6979. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, B.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Jahan, Z.; Khan, O.; Shahid, A.; Shah, G.A.; Azeem, B.; Iqbal, Z.; Mahmood, A. Role of zinc-coated urea fertilizers in improving nitrogen use efficiency, soil nutritional status, and nutrient use efficiency of test crops. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 888865. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; et al. Improving crop productivity and nitrogen use efficiency using sulfur and zinc-coated urea: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 942384. [CrossRef]

- Arachchige, K.V.; McBeath, T.M.; Smernik, R.J.; Hettiarachchi, G.M.; Khalil, R. The effect of metal oxide coating of urea on mineralization in two contrasting soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2023, 87, 1304–1319. [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, S.; Mahmood, R.; Fatima, A.; Nadeem, F.; Ali, S.; Ali, N.; Haider, M.S.; Ma, Q. Iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) coated urea application enhances nitrogen (N) status and bulb yield of onion (A. cepa) through prolonged urea-N stay in alkaline calcareous soil. Sci. Hortic. 2024, *336*, 113421. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Peng, Z.; Wang, G. An overview: metal-based inhibitors of urease. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023, *38*, 361-375. [CrossRef]

- Jadon, P.; Selladurai, R.; Yadav, S.S.; Coumar, M.V.; Dotaniya, M.L.; Singh, A.K.; Bhadouriya, J.; Kundu, S. Volatilization and leaching losses of nitrogen from different coated urea fertilizers. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2018, 18, 1036-1047. [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.O.; et al. Facile coating of urea with low-dose ZnO nanoparticles promotes wheat performance and enhances Zn uptake under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 168. [CrossRef]

- Thabit, F.N. Influence of Nano-Zinc Oxide Coated Urea Fertilizer on Ammonia Volatilization Loss and Inorganic Nitrogen Content in Loamy Sand Soil. J. Soil Sciences Agric. Engin. 2021, 12, 189-193. [CrossRef]

- Beig, B.; et al. Development and testing of zinc sulfate and zinc oxide nanoparticle-coated urea fertilizer to improve N and Zn use efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1058219. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S., Aziz, T., Zia-ur-Rehman, M. et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles coated urea enhances nitrogen efficiency and zinc bioavailability in wheat in alkaline calcareous soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 2023, 30, 70121–70130. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, C.F.S.; Rodrigues, D.R.; Rorato, A.F.S.; Echer, F.R. Cover crops and controlled-release urea decrease nitrogen mobility and improve nitrogen stock in a tropical sandy soil with cotton cultivation. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2022, 46, e0210113. [CrossRef]

- EMBRAPA. Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária. Centro Nacional de Pesquisa em Solo. Manual of soil analysis methods. 2.ed. Rio de Janeiro, 2011. 225p.

- Tedesco, M.J.; et al. Soil, plant and other material analyses. Porto Alegre: UFRGS, 1985. 95p.

- Marcelino, R.M.O.; et al. Vermiculite mining waste enriched with elemental sulfur as a chemical conditioner for alkaline saline soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2022, 54. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, M.Y.; Glass, A.D.M. Utilization index: A modified approach to the estimation and comparison of nutrient utilization efficiency in plants. J. Plant Nutr. 1981, 4, 289-302. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–609.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Viena: Austria, 2023.

- Mendes, W.C.; Alves Junior, J.; Cunha, P.C.R.; Silva, A.R.; Evangelista, A.W.P.; Casalori, D. Nitrate leaching as a function of irrigation depths in clayey and sandy soils. Rev. Irriga 2015, 47-56.

- Laura Côté; Grégoire, G. Reducing nitrate leaching losses from turfgrass fertilization of residential lawns. J. Environ. Qual. 2021, 50, 1145–1155. [CrossRef]

- Haseeb-ur-Rehman; Malik Ghulam Asghar; Rao Muhammad Ikram; Hashim, S.; Hussain, S.; Irfan, M.; Mubeen, K.; Ali, M.; Alam, M.; Ali, M.; Haider, I.; Shakir, M.; Skalicky, M.; Alharbi, S.A.; Alfarraj, S. Sulphur coated urea improves morphological and yield characteristics of transplanted rice (Oryza sativa L.) through enhanced nitrogen uptake. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 34, 101664. [CrossRef]

- Brace, B.E.; Schlossberg, M.J. Field Evaluation of Urea Fertilizers Enhanced by Biological Inhibitors or Dual Coating. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2118. [CrossRef]

- Faraz, A.; Imran, A.; Raza, H.; Iqbal, M. and Rehman, A. Sulfur nanoparticle-coated urea improves growth and nitrogen use efficiency in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 1565608. [CrossRef]

- Stamford, N.P.; et al. Effect of gypsum and sulfur with Acidithiobacillus on soil salinity alleviation and on cowpea biomass and nutrient status as affected by PK rock biofertilizer. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 192, 287-292. [CrossRef]

- Mumbach, G.L.; Brignoli, F.M.; Gatiboni, L.C. Recommendation of elemental sulfur for reducing the pH of soils in southern Brazil. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2022, 26, 212-218. [CrossRef]

- Corbalán, M.; Da Silva, C.; Barahona, A.; Huiliñir, C.; Guerrero, L. Nitrification–Autotrophic Denitrification Using Elemental Sulfur as an Electron Donor in a Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR): Performance and Kinetic Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4269. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, D.; Wu, Z.; Xue, Y.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Y. Effects of nitrification inhibitors on soil nitrification and ammonia volatilization in three soils with different pH. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1674. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, D.C.; Patel, C.M.; Heitz, A.A.H.M.;Anwar, F. Evaluation of zinc and copper for co-inhibition of nitrification in mild nitrified drinking water. J. Environ. CheM. Engineering, 2018, 6, 2939-2943. [CrossRef]

- Khariri, R.b.A.; Yusop, M.K.; Musa, M.H.; et al. Laboratory Evaluation of Metal Elements Urease Inhibitor and DMPP Nitrification Inhibitor on Nitrogenous Gas Losses in Selected Rice Soils. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 232. [CrossRef]

- Ma; I.; M; Irshad, S; Khan, S; Hasnain, Z; Ibrar, D; Khan, A.R.; Saleem, M.F.; Bashir, S; Alotaibi, S.S.; Matloob, A; Farooq, N; Ismail, M.S.; Cheema, M.A. Nitrogenous Fertilizer Coated With Zinc Improves the Productivity and Grain Quality of Rice Grown Under Anaerobic Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 914653. [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2012.

- The, S.V.; Snyder, R.; Tegeder, M. Targeting nitrogen metabolism and transport processes to improve plant nitrogen use efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 628366. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugapriya, D.; Senthil, A.; Raveendran, M.; Djanaguiraman, M.; Anitha, K.; Ravichandran, V.; Pushpam, R.; Marimuthu, S. Responses of cereals to nitrogen deficiency: Adaptations on morphological, physiological, biochemical, hormonal and genetic basis. Plant Sci. Today 2025, 12,1-10, . [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Walk, T.C.; Han, P.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Xie, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Yu, C.; Tian, J.; Shaff, J.E.; Kochian, L.V.; Liao, X.; Liao, H. Adaption of roots to nitrogen deficiency revealed by 3d quantification and proteomic analysis. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 329-347. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Palisaar, J.; Grünhofer, P.; Zeisler-Diehl, V.; Schreiber, L.; Dittert, K.; Kreszies, T. Nitrogen availability affects aerenchyma formation and suberization in early root development of soil-grown maize. Plant Sci. 2025, 362, 112786. [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, F.; Gao, Q.; et al. Effects of nitrogen application on root length and grain yield of rain-fed maize under different soil types. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 1656–1665. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Q.; Davis, K.E.; Patterson, C.; Oo, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Fontana, J.E.; Thornburg, T.E.; Pratt, I.S.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhang, B. Response of Root Growth and Development to Nitrogen and Potassium Deficiency as well as microRNA-Mediated Mechanism in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 695234. [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.; Wahid, M. A.; Farrukh Saleem, F.M., et al. Zinc coated urea enhanced the growth and quality of rice cultivated under aerobic and anaerobic culture. J. Plant Nutrition, 2021, 45, 1198–1213. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.H. Functions and strategies for enhancing zinc availability in plants for sustainable agriculture. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 7;13,1033092. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.L.J.; Valladares, G.S.; Vieira, J.S.; Coelho, R.M. Availability and spatial variability of copper, iron, manganese and zinc in soils of the State of Ceará, Brazil. Rev. Cienc. Agron. 2018, 49, 371-380. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; et. al. Iron transport and its regulation in plants. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 11-20.

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Kang, Y.; Shi, M.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Qin, S. Application of different foliar iron fertilizers for improving the photosynthesis and tuber quality of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and Enhancing Iron Biofortification. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 79. [CrossRef]

- Gao D.; Zhao S.; Huang R.; Geng Y.; Guo L. The Effects of exogenous iron on the photosynthetic performance and transcriptome of rice under salt-alkali stress. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1253. [CrossRef]

- Mahawar, L., Ramasamy, K.P., Pandey, A. et al. Iron deficiency in plants: an update on homeostasis and its regulation by nitric oxide and phytohormones. Plant Growth Regul. 100, 283–299 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sadeghzadeh, B. A review of zinc nutrition and plant breeding. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2013, 13, 905-927. [CrossRef]

- Reshma, Z.; Meenal, K. Foliar application of biosynthesized zinc nanoparticles as a strategy for ferti-fortification by improving yield, zinc content and zinc use efficiency in amaranth. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10912. [CrossRef]

- Jalal, A.; Júnior, E.F.; Teixeira Filho, M.C.M. Interaction of Zinc Mineral Nutrition and Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria in Tropical Agricultural Systems: A Review. Plants 2024, 13, 571. [CrossRef]

- Hams, S.; Mahmood, S; Ishaque, W. Slow Mineral Nitrogen Release from Boron Coated Urea Improves Productivity of Sunflower Grown in Alkaline Soil. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr.2025, 25, 7265–7280. [CrossRef]

- Cassim, B.M.A. R.; Lisboa, I.P.; Prestes, C.V.; Almeida, E.; Carvalho, H.W.P.; Lavres Junior, J., et al. Development and characterization of enhanced urea through micronutrients and established technology addition. Agronomy Journal, 2024, 116, 2573–2587. [CrossRef]

- Mirbolook A, Sadaghiani MR, Keshavarz P, Alikhani M. New Slow-Release Urea Fertilizer Fortified with Zinc for Improving Zinc Availability and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Maize. ACS Omega. 2023, 22, 45715-45728. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Records of maximum (T max) and minimum (T min) air temperature and maximum (RHmax) and minimum (RHmin) air relative humidity on greenhouse during the experimental period.

Figure 1.

Records of maximum (T max) and minimum (T min) air temperature and maximum (RHmax) and minimum (RHmin) air relative humidity on greenhouse during the experimental period.

Figure 1.

Changes in net cumulative leachate of ammonium nitrogen- N-NH4+ (a), nitrate nitrogen -N-NO3- (b), N-NH4+ + N-NO3-, and N-NH4+ to N-NO3- ration in leachate (d), as a function of coating urea treatments and days after soil incubation. 0N: control (no nitrogen application); U: Standard urea (uncoated); U+S: Sulfur-coated urea (elemental sulfur); U+S+NP: Sulfur-coated urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Data represent means ± S.E. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between means at the 5% level by Tukey’s test.

Figure 1.

Changes in net cumulative leachate of ammonium nitrogen- N-NH4+ (a), nitrate nitrogen -N-NO3- (b), N-NH4+ + N-NO3-, and N-NH4+ to N-NO3- ration in leachate (d), as a function of coating urea treatments and days after soil incubation. 0N: control (no nitrogen application); U: Standard urea (uncoated); U+S: Sulfur-coated urea (elemental sulfur); U+S+NP: Sulfur-coated urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Data represent means ± S.E. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between means at the 5% level by Tukey’s test.

Figure 2.

Amounts of leached nitrogen at 30 days from incubation as ammonium nitrogen- N-NH4+ (a), nitrate nitrogen -N-NO3- (b), N-NH4+ + N-NO3-, and N-NH4+ to N-NO3-ration (d), as a function of coating urea treatments. 0N: control (no nitrogen application); U: Standard urea (uncoated); U+S: Sulfur-coated urea (elemental sulfur); U+S+NP: Sulfur-coated urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Data represent means ± S.E. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between means at the 5% level by Tukey’s test.

Figure 2.

Amounts of leached nitrogen at 30 days from incubation as ammonium nitrogen- N-NH4+ (a), nitrate nitrogen -N-NO3- (b), N-NH4+ + N-NO3-, and N-NH4+ to N-NO3-ration (d), as a function of coating urea treatments. 0N: control (no nitrogen application); U: Standard urea (uncoated); U+S: Sulfur-coated urea (elemental sulfur); U+S+NP: Sulfur-coated urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Data represent means ± S.E. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between means at the 5% level by Tukey’s test.

Figure 3.

Leaf dry matter-LDM (a), shoot dry matter-SDM (b), root dry matter-RDM (c), shoot dry matter-SDM (d), aerial dry matter-TDM (e) and total dry matter-TDM (f) as a function of coating urea treatments. 0N: control (no nitrogen application); U: Standard urea (uncoated); U+S: Sulfur-coated urea (elemental sulfur); U+S+NP: Sulfur-coated urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Data represent means ± S.E. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between means at the 5% level by Tukey’s test.

Figure 3.

Leaf dry matter-LDM (a), shoot dry matter-SDM (b), root dry matter-RDM (c), shoot dry matter-SDM (d), aerial dry matter-TDM (e) and total dry matter-TDM (f) as a function of coating urea treatments. 0N: control (no nitrogen application); U: Standard urea (uncoated); U+S: Sulfur-coated urea (elemental sulfur); U+S+NP: Sulfur-coated urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Data represent means ± S.E. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between means at the 5% level by Tukey’s test.

Figure 4.

Nitrogen accumulation in leaves (a), stems (b), aerial part (c), and nitrogen use efficiency NUE (d) as a function of coating urea treatments. 0N: control (no nitrogen application); U: Standard urea (uncoated); U+S: Sulfur-coated urea (elemental sulfur); U+S+NP: Sulfur-coated urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Data represent means ± S.E. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between means at the 5% level by Tukey’s test.

Figure 4.

Nitrogen accumulation in leaves (a), stems (b), aerial part (c), and nitrogen use efficiency NUE (d) as a function of coating urea treatments. 0N: control (no nitrogen application); U: Standard urea (uncoated); U+S: Sulfur-coated urea (elemental sulfur); U+S+NP: Sulfur-coated urea with iron oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Data represent means ± S.E. Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between means at the 5% level by Tukey’s test.

Table 1.

Chemical and physical attributes of the soil used in the experiment.

Table 1.

Chemical and physical attributes of the soil used in the experiment.

| Chemical attibutes |

Value |

Physical attibutes |

Value |

| Ca2+ (cmolc dm-³) |

1.45 |

Sand (g kg-1) |

93.66 |

| Mg2+ (cmolc dm-³) |

1.30 |

Silt (g kg-1) |

5.02 |

| Na+(cmolc dm-³) |

0.04 |

Clay (g kg-1) |

1.33 |

| K+ (cmolc dm-³) |

0.13 |

BD (g cm-3) |

1.56 |

| H+ (cmolc dm-³) |

0.00 |

PD (g cm-3) |

2.71 |

| Al3+(cmolc dm-³) |

0.00 |

TP (%) |

42.43 |

| V (%) |

100.00 |

--------------Soil moisture------------ |

| CO (g kg-1) |

1.33 |

0.10 atm |

16.59 |

| SOM (g kg-1) |

2.30 |

0.33 atm |

12.87 |

| N- total (g kg-1) |

0.07 |

1.00 atm |

9.47 |

| P (mg dm-³) |

8.10 |

5.00 atm |

5.96 |

| pH H2O (1:2.5) |

6.05 |

10.00 atm |

5.64 |

| CE1:5 (µS cm-1) |

0.18 |

15.00 atm |

5.34 |

Table 2.

Summary of analysis of variance for amounts of ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3-), NH4+ + NO3- and N-NH4+ to N-NO3-ration.

Table 2.

Summary of analysis of variance for amounts of ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3-), NH4+ + NO3- and N-NH4+ to N-NO3-ration.

| |

Mean square and F test |

| SV |

DF |

NH4+

|

NO3-

|

NH4+ + NO3-

|

NH4+ / NO3-

|

| Treatments |

3 |

383355.86 ** |

3871.20** |

549686.81** |

64.40** |

| Error |

16 |

4064.72 |

20.02** |

1144,52** |

1.20** |

| CV (%) |

7.55 |

16.18 |

7.55 |

7.22 |

18.86 |

Table 3.

Summary of analysis of variance for leaves dry matter (LDM), stem dry matter (SDM), shoot dry matter (SDM), total dry matter (TDM), RDM-/SDM ratio and accumulated nitrogen in leaves (N-LDM), stems (N-CDM), shoots (N-SDM) and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE).

Table 3.

Summary of analysis of variance for leaves dry matter (LDM), stem dry matter (SDM), shoot dry matter (SDM), total dry matter (TDM), RDM-/SDM ratio and accumulated nitrogen in leaves (N-LDM), stems (N-CDM), shoots (N-SDM) and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE).

| Mean square and F test |

| SV |

DF |

LDM |

CDM |

RDM |

SDM |

TDM |

| Treatments |

3 |

206.189** |

466.609** |

510.660** |

1249.693** |

3276.553** |

| Error |

16 |

2.40 |

3.57 |

10.671 |

6.251 |

24.599 |

| CV (%) |

|

12.99 |

12.96 |

16.51 |

9.43 |

10.71 |

| |

|

RDM/SDM |

N-LDM |

N-CDM |

N-SDM |

NUE |

| Treatments |

3 |

1.284** |

189116.033** |

138763.855** |

598951.640** |

2.648** |

| Error |

16 |

0.024 |

6372.272 |

5018.015 |

10106.729 |

0.0863 |

| CV (%) |

|

16.19 |

23.66 |

31.72 |

17.92 |

22.75 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).