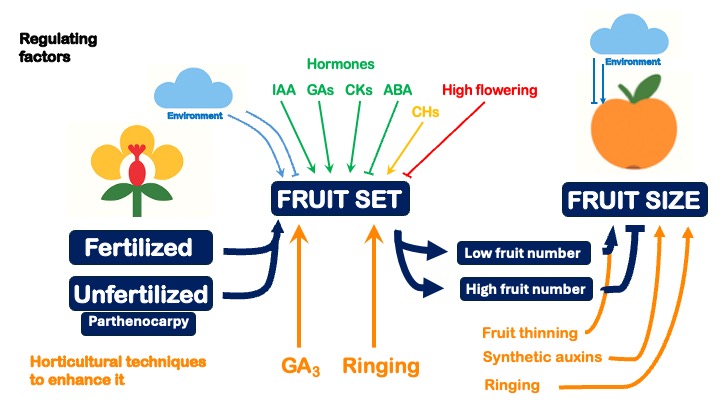

1. Introduction

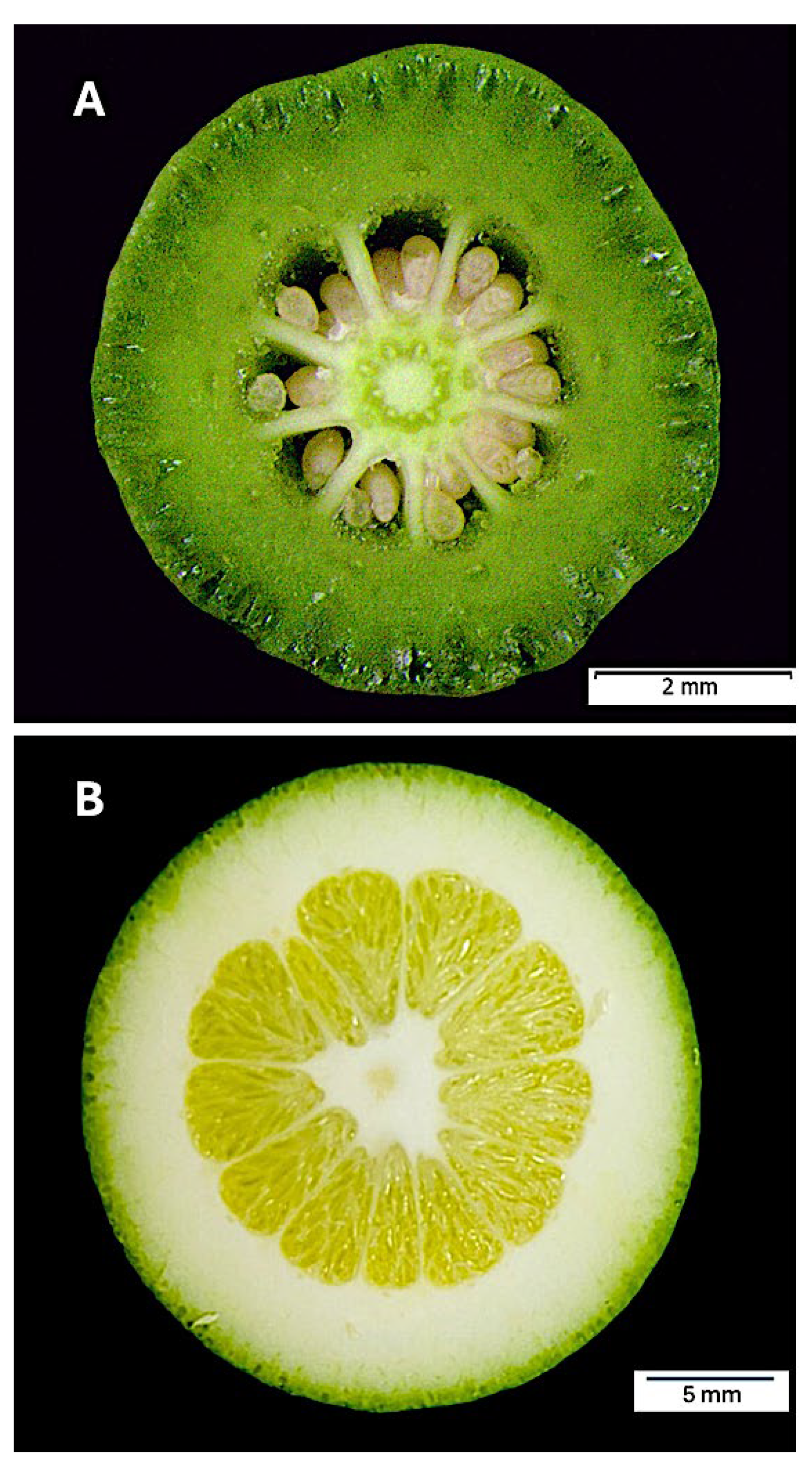

Citrus fruit is classified as a modified berry known as

hesperidium. It is composed of 9 to 14 carpels fused around the floral axis, forming

locules where

juice vesicles, or

juice sacs, and seeds develop (

Figure 1). The

pericarp is structurally differentiated into three distinct layers. The exocarp, or

flavedo, constitutes the outermost region of the fruit and comprises an epidermal layer and several layers of hypodermal cells forming a compact parenchyma. It is enveloped by a cuticle composed of crystalline-structured epicuticular waxes. The

mesocarp, or

albedo, consists of parenchymatous tissue characterized by multiple cell layers, large intercellular spaces, and a spongy texture. The

endocarp, the innermost layer of the pericarp, forms part of the locular membrane. It includes an epidermis (the layer directly adjacent to the locule) and several layers of compact parenchymatous cells. As the fruit ripens, the rind—comprising both the mesocarp and exocarp—may progressively detach from the endocarp. The flavedo is responsible for the fruit’s characteristic coloration, which varies among different citrus species and varieties.

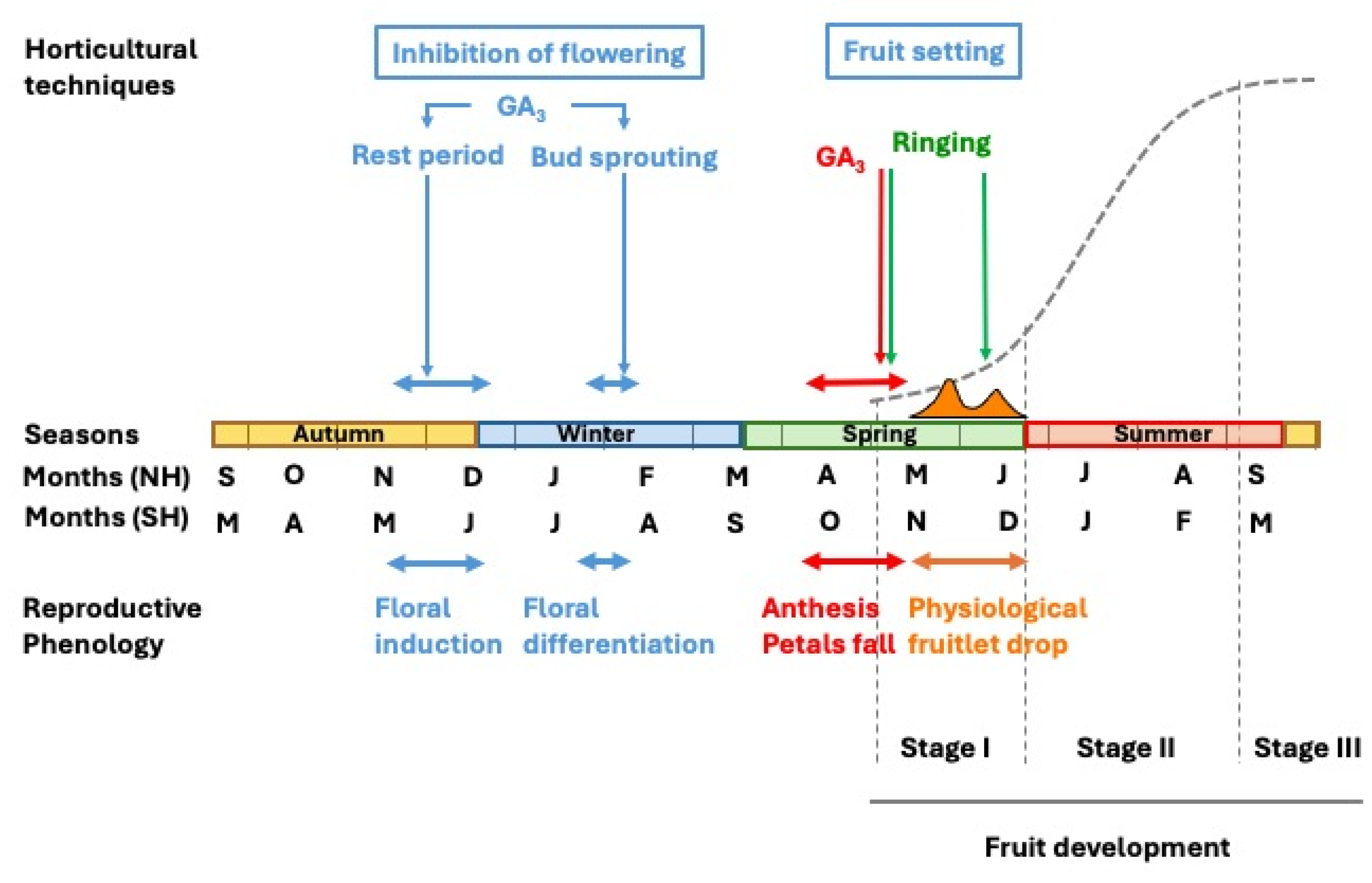

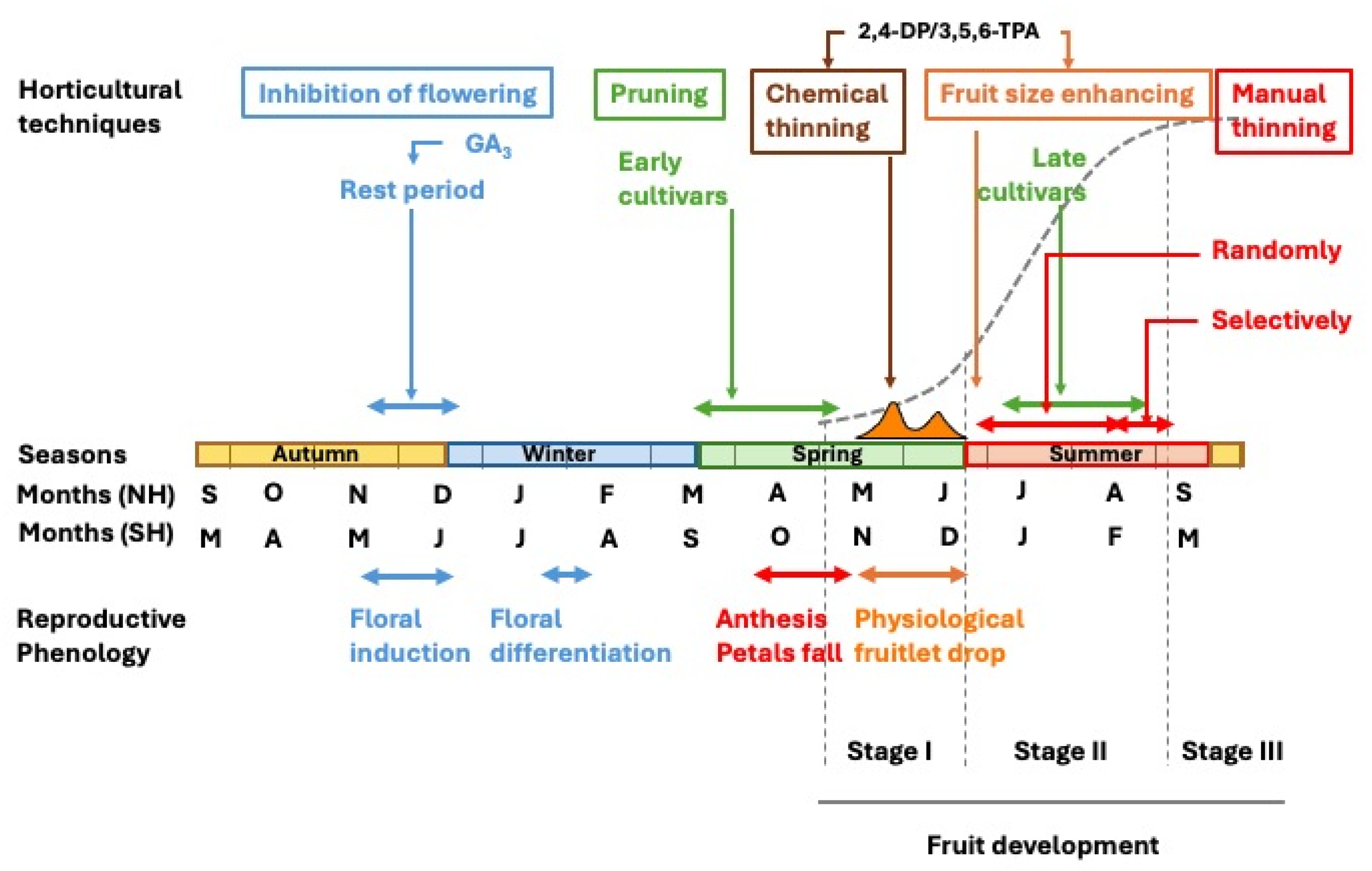

The growth and developmental pattern of citrus fruit undergoes the ovary growth and differentiation, ultimately maturing into a fully developed fruit. This process initiates after anthesis in spring and extends over a period of 6 to 9 months, depending on species and cultivars. In temperate regions with a Mediterranean climate, early-maturing varieties ripen in early autumn, whereas late-maturing cultivars may continue their development into winter. In subtropical regions, the fruiting period is typically 1 to 2 months shorter, and in tropical climates, it is further reduced. Measured in terms of size (diameter, length, or volume) or weight, fruit development follows a sigmoidal curve over time and can be divided into three distinct stages (Bain, 1958).

Stage I represents an initial phase of moderate growth, extending from anthesis to the completion of physiological fruitlet abscission, lasting slightly over two months. During this period, cell division is the predominant process, leading to an increase in the number of cells across all developing tissues. Fruit enlargement primarily results from the growth of ovary wall tissues (pericarp), which later differentiate into the fruit peel, and differentiation of the juice vesicles from the endocarp, which later form the pulp. By the end of this stage, the pericarp attains its maximum thickness (

Figure 2). This phase is commonly referred to as the fruit-setting stage.

The mesocarp constitutes the pericarp region that undergoes the most significant expansion during Stage I of fruit development (

Figure 2), driven by ovary growth. The highest rate of cell division occurs in the outer mesocarp, where a narrow layer of cells retains meristematic characteristics. These cells are small, possess thin walls, and are densely packed. As development progresses, these cells are displaced into deeper tissue layers, where they enlarge, their walls thicken, and intercellular spaces expand. The transition from the outer to the inner mesocarp is particularly evident at the organelle level (Schneider, 1968). Notably, plastids undergo substantial transformations: in the outer mesocarp, chloroplasts remain photosynthetically active but gradually degrade as the cells migrate inward, ultimately differentiating into amyloplasts. Throughout fruit development, both chloroplasts and amyloplasts progressively lose their starch reserves (Mehouachi et al., 1995; Mesejo et al., 2019).

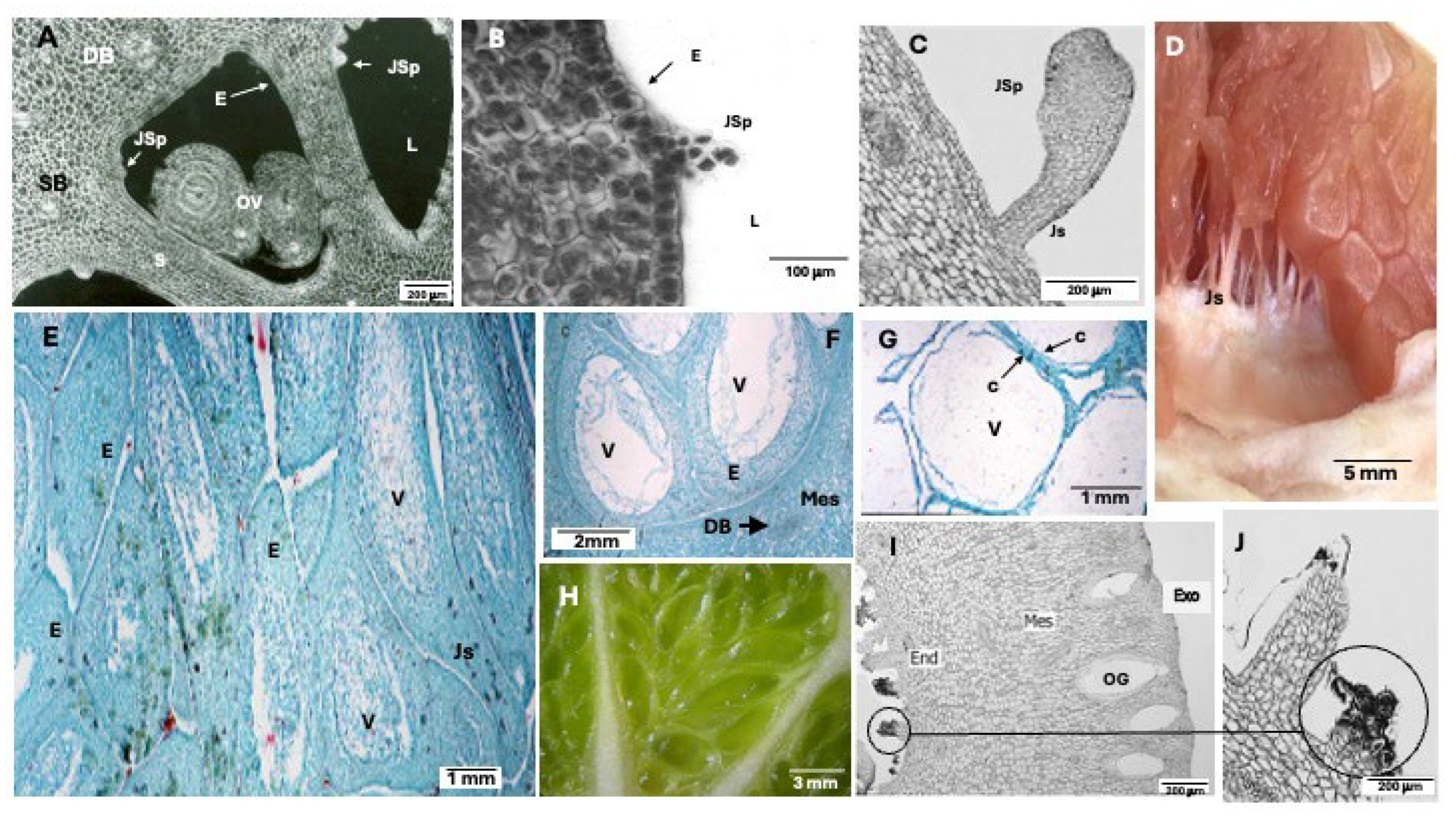

The innermost pericarp layer, the endocarp, exhibits minimal growth during Stage I, significantly less than that of the mesocarp (

Figure 2). Consequently, the locule volume increases only moderately, primarily through cell division in the septa and tangential walls of the locules. In the septa, divisions occur periclinally, whereas in the tangential walls, they follow an anticlinal pattern. The septa correspond to the walls of the carpels. Within the endocarp, and extending laterally from it, each carpel contains two locular membranes composed of endocarp-like tissue, which converge at the floral axis. Between the membranes of adjacent locules, a parenchymatous mesocarp-like tissue forms the

septum (

Figure 3 A). This tissue degrades readily, facilitating the natural separation of locules or segments in ripe fruits.

Juice vesicles are delicate, filamentous structures that originate at anthesis from cells in the innermost layers of the endocarp. These cells subsequently differentiate into the epidermis and subepidermis of the locule, a process that concludes following the abscission of the style. The epidermal cells of the endocarp primarily undergo anticlinal divisions; however, for reasons not yet fully understood, they occasionally shift to oblique and periclinal planes. This shift gives rise to a protrusion, or vesicular primordium (Fiure 3 A), which extends inward toward the locule while its daughter cells retain meristematic activity (

Figure 3 B, C). The terminal cells within the primordium undergo thickening to form the

vesicle, whereas the basal cells differentiate into the

stalk, which establishes a permanent structural connection between the vesicle and the endocarp (

Figure 3D) (Schneider, 1968).

The vesicle is enclosed by a robust epidermis covered with a waxy cuticle and contains large, highly vacuolated cells that store juice (

Figure 3 E, F, G), primarily composed of sugars, organic acids, and water. The stalk consists of an epidermis with a thin cuticle and parenchymal cells interconnected by plasmodesmata and plasmalemma invaginations, which facilitate the transport of substances. Notably, the stalk lacks vascular bundles. As juice vesicles grow and expand, they progressively fill the locular cavity (

Figure 3 H) (Schneider, 1968).

Shortly before anthesis,

carpel emergences begin to develop alongside the vesicles from initial cells distinct from the surrounding tissue lining the interior of the locular cavity (

Figure 3 I, J). These emergences comprise clusters of globular cells that actively proliferate and grow in a disordered manner toward the locule interior. Typically, the terminal cells enlarge, and their middle lamellae undergo softening, ultimately leading to their detachment. The initial development of carpel emergences progresses more rapidly than that of juice vesicles; however, their growth rate decreases considerably shortly thereafter and ceases entirely before the completion of Stage I. The cytoplasm of these globular cells is characterized by the presence of numerous Golgi vesicles and lipid bodies. Carpel emergences are hypothesized to function as secretory structures (Schneider, 1968).

During Stage II, the fruit grows linearly as a result of the enlargement of its cells, which no longer divide (see section “Fruit development”). By the end of this stage, the fruit attains its maximum size (Bain, 1958).

In Stage III, fruit growth ceases, and instead, significant metabolic changes occur, leading to ripening, subsequent senescence, and eventual abscission (Bain, 1958). At this point, the fruit must be harvested for consumption. The study of this stage falls beyond the scope of this review.

This work addresses fruit setting and fruit development separately. The first section emphasizes current knowledge on the endogenous regulation, particularly carbohydrate availability and hormonal control, of the transition from ovary to developing fruit, with a special focus on the mechanisms underlying parthenocarpy. The second section reviews the role of auxins in cell enlargement as a prerequisite for water and solute uptake. Agronomic practices derived from these insights are also updated in both sections.

2. Fruit Setting

Orange and mandarin trees bloom profusely, with the number of flowers far exceeding the final fruit yield. Most of flowers abscise at various developmental stages, with an increasing trend as flowering intensity increases (Goldschmidt and Monselise, 1977; Agustí et al., 1982b). After anthesis, some ovaries exhibit slow or arrested development, turning completely yellow, while others grow more rapidly and maintain a dark green, glossy appearance. The former are destined to abscise, whereas the latter typically continue development until ripening. Consequently, from petals fall until late June or early July in the Northern Hemisphere (NH), a massive abscission of ovaries and fruitlets occurs, a phenomenon known as physiological fruitlet abscission.

This entire process is referred to as fruit set in citrus. For an individual flower, fruit set can be divided into two phases: the transition from ovary’s slow developmental stage to the rapid growth phase of the young fruit, and the subsequent abscission process. Although these phases are governed by distinct regulatory mechanisms, they are primarily influenced by competition among developing fruitlets (Zucconi et al., 1978; Guardiola et al., 1984) and between fruitlets and concurrently growing vegetative shoots (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2015). This competitive interaction ultimately determines the number of fruits that reach maturity (Goldschmidt and Monselise, 1977). Therefore, fruit set is the main limiting factor in the productivity of cultivated citrus varieties.

2.1. Fertilization vs. Parthenocarpy

In general, citrus varieties require successful pollination, which involves the fertilization of ovules after anthesis to ensure proper ovary development and ultimately seed formation. This process requires the pollen grains to reach the stigma, their subsequent germination, and the elongation of the pollen tube through the style to reach the ovary and fertilize the ovules.

In citrus, the stigma is relatively large compared to the style diameter and is covered with papillae, whose cell number and size vary. These papillae play a crucial role in pollen hydration and germination. Upon germination, the pollen tube grows through the stylar canal, eventually reaching the ovule to facilitate fertilization.

The ovary and ovule emit signaling cues that guide and regulate the pollen tube as it navigates through the locule, ensuring its proper trajectory (Herrero, 2001). Three lines of evidence support this regulatory mechanism.

First, physiological changes in female tissues influence pollen tube growth. In fruit trees, the obturator, located at the base of the style, has been shown to modulate the trajectory of the pollen tube as it approaches the ovule. In citrus species, this role is fulfilled by papillary hairs (Distefano et al., 2011). Furthermore, pollen tube entry into the ovule is governed by a chemotropic response; in this process, the initial cells of the micropyle secrete specific compounds that facilitate pollen tube penetration (Tilton et al., 1984).

Second, the embryo sac exerts control over pollen tube guidance. Synergid cells play a crucial role in attracting the pollen tube by synthesizing peptide signals (Okuda et al., 2009).

Third, certain biochemical factors present in the pistil are implicated in pollen tube development (see review by Shi and Yang, 2010). Among these: (1) Ca²⁺ plays a key role in regulating pollen tube growth, with concentrations in ovules and placenta found to be four times higher than in the rest of the style; moreover, Ca²⁺ is actively consumed in pollinated ovaries but remains unutilized in unpollinated ones; (2) specific molecules in the stigma and style, including kinases, enzymes associated with floral incompatibility systems, have been implicated in pollen tube regulation; and (3) adhesion-related molecules, as well as glycoproteins involved in pollen tube nutrition, have been identified.

However, the pollen tube must reach the ovule and accomplish fertilization within a restricted timeframe, as ovule receptivity persists for only a few days. This window is referred to as the effective pollination period (EPP), which varies across species and cultivars. EPP is defined as the difference between ovule longevity and the time required for the pollen tube to reach the embryo sac, further constrained by the duration of stigma receptivity to pollen germination.

In `Clemenules’ mandarin and `Valencia’ sweet orange, pollen tubes remain capable of fertilizing ovules up to 8 days after anthesis (DAA) (Mesejo et al., 2007). This time to reach the ovary is significantly reduced by 2-3 days at high temperatures (20-30ºC) and increased at low temperatures (10ºC) (Distefano et al., 2018; Montant et al., 2019). However, in flowers pollinated at 10 DAA, pollen tubes fail to reach the ovary, as evidenced by the absence of seed development. This is because a physical barrier forms at the base of the stigma papillae at 10 DAA, preventing pollen tube progression into the stylar canals in these cultivars. This indicates how the stigma receptivity constrains the EPP. Conversely, in Satsuma mandarin this limitation occurs earlier and although fertilization fails at 4 DAA, no such barrier is observed at the stigma, suggesting that ovule longevity is the primary limiting factor in this species (Mesejo et al., 2007). Accordingly, in citrus flowers, receptivity varies by species.

In addition, since callose is a carbohydrate that impairs sugar transport to the ovule, its deposition at the chalazal end has been used as an early indicator of impending ovule abortion. In emasculated flowers of `Clemenules’ mandarin and `Valencia’ sweet orange, callose accumulation in unfertilized ovules occurs at 12 DAA. In contrast, in ‘Owari’ Satsuma mandarin, 100% of ovules exhibit signs of degeneration 4 days earlier (Mesejo et al., 2007).

Typically, successful pollination and fertilization reactivate cellular division, which slows during anthesis. This process is crucial for ovary development, ultimately leading to fruit and seed formation (Mesejo et al., 2016). However, many Citrus varieties do not require ovule fertilization for ovary development. This phenomenon, known as parthenocarpy, is defined as the ability of a flower to set fruit without ovule fertilization, thereby preventing seed formation.

In citrus, parthenocarpy arises from homogenetic sterility, in which pollen is incapable of fertilizing flowers of the same or a different variety—referred to as self-incompatibility and cross-incompatibility, respectively—or from gametic sterility. The latter includes androsterility or gynosterility, characterized by the absence or defective development of pollen or ovules, respectively (Vardi et al., 2008). The Clementine mandarin and its mutations, along with certain hybrids, provide a representative example of self-incompatibility. In contrast, gametic sterility, marked by extensive degeneration of embryo sacs, is observed in sweet orange cultivars of the navel group, Satsuma mandarins, and ‘Marsh seedless’ grapefruit. However, a few sacs may fully develop and produce seeds, albeit in very limited numbers (Frost and Soost, 1968). Interestingly, the presence of pollen tube growth inhibitors in the stigma or style can prevent fertilization, which can also be induced by environmental factors that cause asynchronous development of the pollen tube and the ovule. The complete absence of seeds occurs almost exclusively in triploid varieties.

Homogenetic sterility also induces facultative parthenocarpy in Citrus (Ollitrault et al., 2021). In this context, the incompatibility between pollen grains and the receptive stigma is governed by a self-sterility gene with multiple alleles. Only pollen grains carrying self-sterility alleles that do not match those of the stigma or style tissues are able to penetrate the ovule. Conversely, when alleles match, various immune responses, such as errors in pollen-stigma protein recognition, synthesis of pollen tube growth inhibitors in the stigma and style, and other biochemical barriers, restrict or entirely prevent pollen tube development. This mechanism ultimately leads to self-incompatibility, inhibiting autogamy.

In Citrus, the polymorphic locus controlling the gametophytic self-incompatibility system, known as the S gene, has been estimated to have several alleles (Ngo et al., 2011). To date, eighteen S-RNases have been reported in pummelo (S1-S9, S16), mandarin (S10-S11), sweet orange, clementine mandarin (S7 and S11) and in other citrus species (S12-S15, S17) (Honsho, 2023; Bennici et al., 2024). The gametophytic S-RNase system associated with the self-incompatibility locus has been mapped to the proximal region of chromosome 7 in the clementine reference genome (Ollitrault et al., 2021).

Facultative parthenocarpy occurs in varieties incapable of self-pollination when cross-pollination is absent. This phenomenon is observed in hybrid mandarins such as ‘Ellendale,’ ‘Nova,’ ‘Fortune,’ and ‘Nadorcott’ (Vardi et al., 2000; Distefano et al., 2009; Gambetta et al., 2013), as well as in highly parthenocarpic clementine cultivars such us ‘Marisol’ (Mesejo et al., 2013). On the other hand, the term obligatory parthenocarpy is used for those varieties that always produce seedless fruits.

The mere deposition of pollen grains on the stigma, their germination, or the development of the pollen tube, in the absence of fertilization, can provide sufficient stimuli to initiate ovary development in the absence of seeds. These cases, which require some form of external stimulus, are classified as stimulated parthenocarpy. In contrast, ovary development occurring without any external stimulus is termed autonomous or vegetative parthenocarpy.

In both scenarios, tissue growth is governed by a genetic factor that sustains relatively high levels of hormones in the ovary during anthesis and immediately thereafter, regardless of pollination and fertilization of the ovules. This has been demonstrated in studies of citrus varieties with different parthenocarpic ability (Mesejo et al., 2013; 2016). Certain self-incompatible varieties with low parthenocarpic ability exhibit reduced productivity unless fertilized with compatible pollen. When pollination occurs, these varieties produce a high proportion of seeded fruits (Frost and Soost, 1968). This phenomenon has been documented in some clementine cultivars arising from bud mutations. The hormonal basis of the stimulus that triggers fruit set is further supported by the ability to artificially induce parthenocarpic development through the application of specific phytohormones.

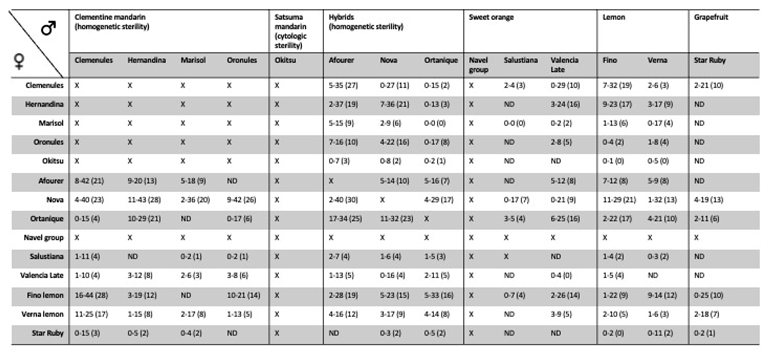

Parthenocarpy is of considerable agronomic importance in cultivated citrus varieties for fresh consumption, particularly mandarins, as seedlessness is widely regarded as a key quality attribute. However, cross-compatibility in

Citrus species is generally high, and most cultivars produce functional pollen capable of fertilising flowers of other varieties, often resulting in seeded fruit (

Table 1).

To solve the problem of cross-pollination, the application of gibberellic acid (GA3) (10 mg l⁻¹) prior to anthesis significantly increases the rate of ovule abortion, with earlier application resulting in greater efficacy. Specifically, seed reduction of 26% and 52% is achieved when applied 2 and 7 days before anthesis, respectively. When applied at anthesis, GA3 completely arrests pollen tube growth, preventing fertilization and seed formation (Mesejo et al., 2008). Similarly, CuSO₄·5H₂O also induces seedless fruit. When applied locally to the flower before pollination, it reduces pollen germination and/or disrupts pollen tube development, thereby preventing the pollen tubes from reaching the embryo sac. However, due to the prolonged flowering period, it is recommended to apply CuSO₄·5H₂O to the entire tree when 60% of the flowers are at anthesis. This treatment reduces the number of seeds per fruit by 55-80% and increases the number of seedless fruits by 150-400%, depending on the year (Mesejo et al., 2006).

2.2. Transition from Ovary to Developing Fruit

During the week following anthesis petal abscission takes place, and approximately two weeks later, the style and stigma also abscise, marking the transition from the ovary to the developing fruit.

The senescence and subsequent abscission of petals are closely associated with their endogenous ethylene production, which serves as the primary regulator of these processes (Ma et al., 2018). Ethylene biosynthesis is strongly induced by indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) through the activation of ACC synthase, leading to the accumulation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), the precursor of ethylene. The application of amino-oxyacetic acid (AOA) or silver thiosulfate (STS) to the petals, inhibitors of ethylene biosynthesis and signaling, respectively, significantly delayed petal wilting, supporting the role of ethylene in this process. It is plausible that endogenous IAA in petals, which is hypothesized to contribute to their curvature at anthesis, triggers ethylene production, thereby promoting petal senescence and abscission (Zacarías et al., 1991).

The earliest external symptom of stigma-style senescence is the emergence of a bright ring above the junction between the style and the ovary. This ring gradually darkens to brown, while the style transitions from light green to yellowish before ultimately detaching from the ovary. Prior to abscission, the stigma papillae become highly vacuolated, with their cytoplasm reduced to a narrow band adjacent to the cell wall. The plastids lose their starch reserves, although dictyosomes remain apparently active. As senescence progresses, lignin deposition occurs progressively in the cell walls of the papillae, as well as in the epidermal cells and the outermost cortical layers (Cresti et al., 1982). Despite this, in some cultivars, a substantial proportion of fruit remain the style attached until ripening.

2.3. Abscission of Developing Fruitlets

Due to the plant’s limited capacity to sustain an excessive number of fruits, a substantial abscission of ovaries and developing fruits typically occurs after petal fall. Prior to this, a variable proportion of flower buds and open flowers may also undergo abscission (Zucconi et al., 1978; Agustí et al., 1982b). Consequently, fruitlet abscission exhibits two waves that generally overlap to varying degrees, although their peaks are usually well-defined. In most cases, the proportion of flowers that successfully develop into mature fruits does not exceed 10%, with typical fruit set rates ranging between 5% and 1%. Under conditions of excessive flowering, fruit set can decline to as low as 0.1% or even lower (Erickson and Brannaman, 1960; Monselise, 1977).

Both waves correspond to characteristic developmental stages. The first wave primarily occurs within 3–4 weeks after petal fall, predominantly affecting ovaries and early-stage fruitlets (approximately 5–10 mm in diameter), although some entire flowers may also abscise. The second wave, commonly referred to as ‘June drop’ in the NH, and more precisely known as physiological fruitlet abscission, begins approximately two weeks after the first abscission period and extends from late May to late June (NH). Generally, a higher flower density results in more pronounced abscission peaks (Agustí et al., 1982b), although climatic conditions can modify the abscission wave by altering peak intensity, shifting their timing, or causing partial overlap. During this period, small developing fruits are shed until they reach a critical size threshold (1–2 cm in oranges or 0.75–1 cm in mandarins), beyond which the likelihood of abscission is significantly reduced. In general, most fruits that survive this second abscission phase remain on the tree until harvest.

The pattern of fruit set varies depending on the cultivar, climatic conditions, and flowering intensity. Regarding cultivar differences, seeded varieties generally exhibit a higher fruit-setting capacity than seedless varieties (García-Papí and García-Martínez, 1984a; 1984b; Bermejo et al., 2015; 2016). Within seedless varieties, there is substantial variation in parthenocarpic ability (Agustí et al., 1982b).

The underlying cause of reproductive organ abscission is the formation of an abscission layer, where tissue weakening occurs (Goren, 1993). During the first wave of fruit drop, shortly after anthesis, the abscission layer forms at the junction between the peduncle and the stem (abscission zone A, AZ-A). In a subsequent phase, as fruits reach a more advanced developmental stage, the second wave of abscission takes place, leading to separation at the junction between the ovary and the floral disc (abscission zone C, AZ-C).

The anatomical, ultrastructural, and biochemical modifications associated with the abscission of young and mature fruits at the AZ, as well as the regulatory effects of IAA and ethylene on this process (Goren, 1993; Estornell et al., 2013), closely resemble those occurring in the abscission zone of leaves (Agustí et al., 2008; 2009). Within the AZ-A, multiple layers of small cortical cells exhibit substantial starch deposits. In contrast, the cortical cells adjacent to the abscission zone are largely devoid of starch accumulation. At the onset of abscission, the cells within the AZ undergo division, starch granules are depleted, and the cytoplasm becomes increasingly electron-dense, accompanied by the emergence of numerous lysosomes (Shiraishi and Yanagisawa, 1988). As the process advances, vesicle production from the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus increases, leading to a release of hydrolytic enzymes, including cellulase and polygalacturonase. These vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane, facilitating the secretion of enzymatic contents into the cell wall. The degradation cascade initiates at the middle lamella, progressively dismantling the primary cell wall until structural disintegration is complete. Ultimately, as the separation zone tissue deteriorates, the ovaries abscise from the tree (Huberman and Goren, 1979). Ethylene enhances the enzymatic activity within the AZ-A by modulating auxin levels (Taylor and Whitelaw, 2001). Moreover, exogenous auxin application at the distal end of the AZ delays abscission, whereas its application at the proximal end accelerates the process (Addicott and Lynch, 1951). These findings suggest that spatiotemporal alterations in auxin gradients may serve as key regulatory signals triggering senescence and abscission (Addicott et al., 1955; Kućko et al., 2019).

Recent studies have begun to elucidate the gene networks regulating abscission in citrus, particularly within the AZ-C. Ethylene plays a central role in modulating gene expression in AZ-C cells, especially those involved in zone activation, cell wall modification, and lignin biosynthesis. In response to 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) treatments, several genes encoding cell wall–degrading enzymes are upregulated, including polygalacturonases (CitPG16, CitPG20, CitPG41, CitPG42, CitPG43), pectate lyases (CitPL5), and cellulases (CitCEL3, CitCEL6, CitCEL10, CitCEL22) (Merelo et al., 2017). Following cell wall loosening, genes associated with lignin biosynthesis, such as CitPAL5 (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase), CitC3H1 (p-coumarate-3-hydroxylase), CitCAD3 (cinnamoyl alcohol dehydrogenase), and CitCASPs (Casparian strip membrane proteins), contribute to monolignol production and lignin polymerization (Merelo et al., 2017).

In addition to transcriptional regulators, components of the RNA silencing machinery have been implicated in ethylene-mediated abscission responses. Small RNAs and their associated gene families—DICER-LIKE (CsDCL1), ARGONAUTE(CsAGO4a), and RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE (CsRDR1a)—show significant downregulation within 12–24 hours of ethylene treatment. These genes are core components of the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway, an epigenetic mechanism involved in gene silencing in plants (Sabbione et al., 2019).

Notably, abscission regulation in citrus is not exclusively governed by ethylene. The INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION–HAESA/HAESA-LIKE2 (IDA–HAE/HSL2) signaling pathway, well characterized in model species, acts independently of ethylene. The Citrus clementina IDA ortholog CitIDA3 can complement the ida mutant phenotype in Arabidopsis (Estornell et al., 2015). Furthermore, CitIDA3 expression is upregulated in Citrus cultivars prone to abscission when ripening and is suppressed by 2,4-D treatment without affecting ethylene biosynthesis (Mesejo et al., 2021). This highlights the presence of both ethylene-dependent and -independent regulatory modules in citrus abscission.

As developing fruits reach the second wave of abscission, the cells of the AZ-A lose their capacity to respond to hydrolytic enzymes, preventing fruit detachment in this zone. During ovary maturation into a fruit, the pedicel diameter increases, and its initial structure, composed of primary vascular bundles arranged in a circular pattern, transitions into a vascular cylinder with secondary growth (Schneider, 1968). In this structure, the phloem forms an external ring, separated from the xylem by the cambium, which develops concentrically inward. The central region is occupied by medullary parenchyma cells, whose walls thicken and undergo lignification. Meanwhile, the AZ-A, located at the base of the peduncle, progressively disappears as secondary phloem and xylem fibers develop within the growing fruit, traversing the former abscission zone. Consequently, during the second abscission wave, fruit detachment occurs through the AZ-C, as also observed in mature fruits.

At the onset of the initial cellular activation of this abscission layer, the AZ-C splits into two groups, representing early and late stages of cell separation. In the early stage, an accumulation of amorphous material, resulting from the partial dissolution of the middle lamella and cell wall of AZ-C cells, makes the AZ-C clearly distinguishable. In the late stage, cell separation becomes evident in the central core of the AZ-C. Once the degradation of the cell wall and middle lamella is complete, large quantities of amorphous material accumulate in the central region (Merelo et al., 2017).

Cells located on the distal side of the AZ-C accumulate starch grains, forming the starch-rich cell area (SA) (Wilson and Hendershott, 1968; Huberman et al., 1983; Shiraishi and Yanagisawa, 1988; Goren, 1993). Additionally, another distinct cellular region is present on the proximal side of the AZ-C (facing the pith), which consists of actively dividing cells (DA). The AZ-C is composed of 10–15 cell layers, encompassing different cellular regions characterized by two distinct cell morphologies and organellar compositions (e.g., SA cells contain amyloplasts). Cell wall degradation and cell degeneration primarily occur within the SA layers at the fracture plane, adjacent to the albedo, whereas cell expansion is predominant in the DA. Lignin deposition occurs in the central core of the AZ-C, between the axial vascular bundles distributed throughout the AZ-C, delineating the separation line between the calyx button and the fruit rind. The timing of lignin deposition is positively correlated with abscission kinetics (Merelo et al., 2017). As for the AZ-A, ethylene enhances the enzymatic activity involved in the activation of the AZ-C.

The pericarp cells of ovaries exhibiting signs of abscission are characterized by the presence of plasma membrane and tonoplast invaginations (van Doorn and Stead, 1997). Mitochondria display a reduced number of cristae, while plastids undergo degradation of their endomembrane system. A key visual distinction between ovaries and developing fruitlets destined for abscission, compared to those that will persist on the tree, is the loss of chlorophyll.

2.4. Endogenous Regulation of Fruit Set

The regulation of fruit set is a critical physiological process, as it determines the final number of fruits that reach maturity and, consequently, has a significant impact on the yield.

This regulation involves both endogenous hormonal levels within the ovary and metabolic control mechanisms, particularly the capacity to allocate photoassimilates to developing fruitlets (Gillaspy et al., 1993).

2.4.1. The Influence of Hormone Levels

A comprehensive review of the available literature on endogenous plant growth regulators and other endogenous compounds with analogous roles in fruit growth regulation was published by El-Otmani, Lovatt, Coggins, and Agustí in 1995. Since then, substantial advancements have been made, with a growing body of research published in recent years. This review synthesizes the latest findings on their role in fruit set regulation.

Pollination and subsequent fertilization of the ovules initiate the hormonal signaling cascade necessary for the transition from ovary to developing fruit (Ben-Cheikh et al., 1997). Studies on fruit set regulation have established that key phytohormones, including gibberellins, auxins, cytokinins, abscisic acid, and ethylene, are intricately involved in this process (Bermejo et al., 2018; Talón et al., 1990a; 1990b; 1992; Zacarías et al., 1995). Their endogenous levels are tightly regulated by genes encoding enzymes responsible for biosynthesis and catabolism (Mesejo et al., 2016). Typically, these hormones exhibit peak activity shortly after anthesis, underscoring their crucial role in the hormonal signaling network that governs fruit set.

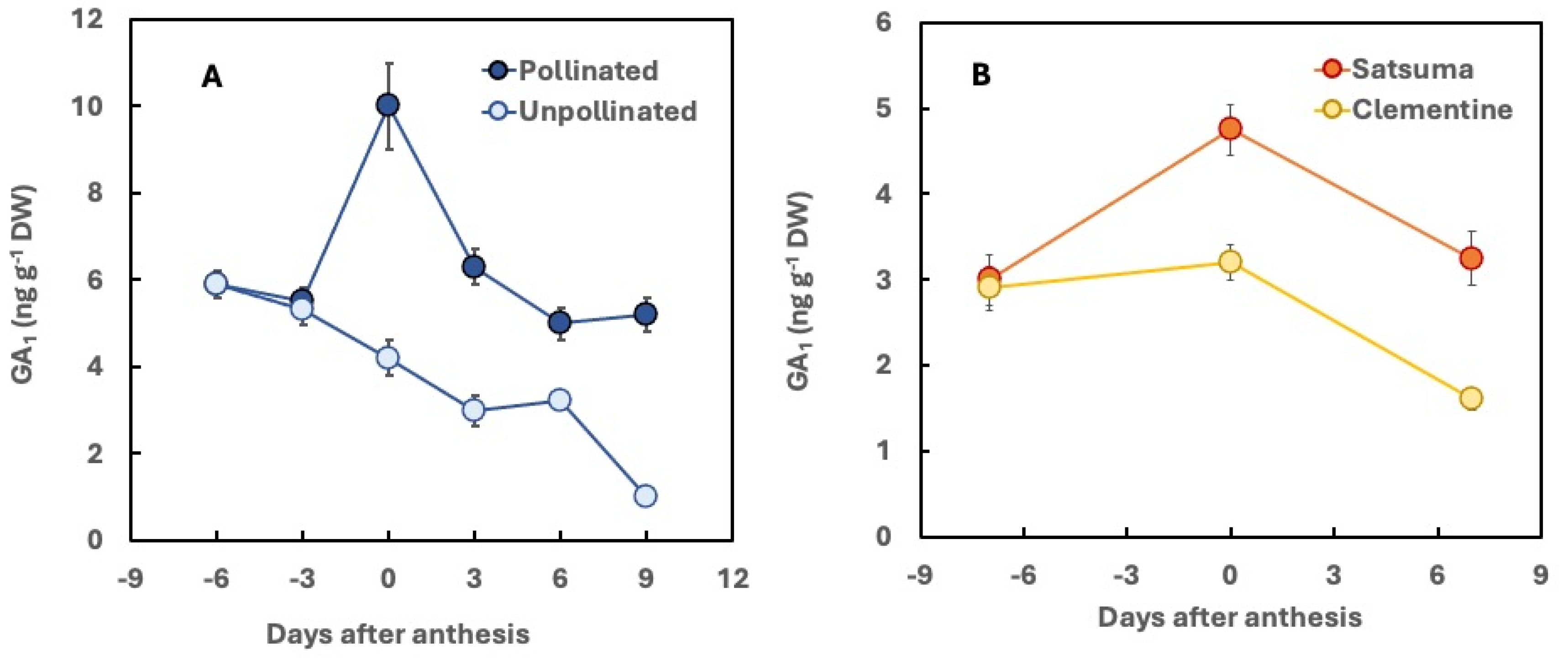

In ovaries and developing fruit, gibberellins (GA) synthesized via two distinct biosynthetic pathways have been identified. In Citrus, the predominant pathway is the 13-hydroxylation route, whereas the non-hydroxylation pathway is less prevalent. This suggests that the former plays a key role in fruit development (Poling, 1991; Talón et al., 1992). Within this pathway, gibberellin GA53 undergoes a series of metabolic steps to yield GA19, which is subsequently converted to GA20 by GA20-oxidase and further metabolized into GA1 by GA3-oxidase (Yamaguchi, 2008; Talón et al., 1992; 1994). In Citrus, two paralogous genes encoding GA20-oxidases have been identified (Huerta et al., 2009). Gibberellin GA1 and its precursor GA20 are catabolized by GA2-oxidases, leading to the formation of GA8 and GA29, respectively, both of which are considered inactive forms.

GA₁ is recognized as the biologically active GA and plays a pivotal role in fruit set and early citrus fruit development (Talón et al., 1990a). In both seedless and seed-bearing parthenocarpic varieties, a peak in GA₁ concentration is observed in the ovary during anthesis. In seeded cultivars, such as the sweet orange ‘Pineapple’ and the mandarin ‘Murcott’, pollination induces GA₁ biosynthesis in the ovaries. Conversely, when pollination is prevented through flower emasculation, GA₁ levels decline (

Figure 4 A), leading to increased ovary abscission (Ben-Cheikh et al., 1997; Bermejo et al., 2015).

In ‘Pineapple’ sweet orange, exogenous application of gibberellic acid (GA₃) enhances fruit set in unpollinated ovaries, whereas treatment of pollinated ovaries with paclobutrazol, a GA biosynthesis inhibitor, reduces GA content and promotes abscission (Ben-Cheikh et al., 1997). In this cultivar, GA biosynthesis is most pronounced in ovules following pollination, coinciding with peak expression of GA20ox2, GA3ox1, and GA2ox1 genes (Bermejo et al., 2016).

In the parthenocarpic and therefore seedless cultivar ‘Washington’ navel, GA levels in both ovules and ovary walls are lower than in ‘Pineapple’ (Bermejo et al., 2016), and their synthesis appears to be constitutively regulated. The higher GA₁ concentration observed in the seeded cultivar correlates with a reduced ovary and fruitlet abscission rate during the post-flowering period. Subsequently, during physiological fruitlet abscission, GA₁ levels in the pericarp of developing fruits remain relatively high in both cultivars, reaching comparable levels despite an overall decline relative to those in the ovary wall after anthesis (Bermejo et al., 2016). In seedless cultivars, the ability to sustain GA₁ concentration in the fruit pericarp during physiological drop is associated with reduced abscission, supporting their parthenocarpic ability.

Similarly, the sterility induced in the ‘Moncalina’ mandarin by γ-ray irradiation of the ‘Moncada’ mandarin disrupts GA biosynthesis via the 13-hydroxylation pathway, as evidenced by the lower levels of GA₁ and its precursor GA₁₉ in the ovaries compared to ‘Moncada’. This effect has been linked to the reduced expression of GA20ox2 and GA3ox1 genes in ‘Moncalina’, resulting in a significant decrease in GA production (Bermejo et al., 2015).

A comparative analysis of two seedless mandarin cultivars with differing parthenocarpic ability indicates that Satsuma mandarin, which exhibits high parthenocarpic ability, contains higher concentrations of GA from the 13-hydroxylation pathway (excluding the inactive GA

8) compared to the clementine ‘Oroval,’ which has low parthenocarpic ability. At anthesis, GA

1 levels in Satsuma ovaries were found to be considerably higher than those in clementine ovaries (

Figure 4 B) (Talón et al., 1990b; 1992). Similarly, in the clementine cultivars ‘Marisol’ and ‘Clemenules,’ which lack seed development in the absence of cross-pollination and exhibit high and low parthenocarpic ability, respectively, GA

1 levels in the ovaries are significantly higher in the former than in the latter (Mesejo et al., 2013).

These findings suggest that GA1 plays a role in promoting ovary growth rather than repressing abscission during the ovary-to-fruit transition (Gómez-Cadenas et al., 2000). In line with this, GA biosynthesis genes GA20ox2 and GA3ox2 are upregulated in Satsuma ovaries during anthesis, whereas their expression remains low in Clemenules mandarin. The activity of GA3ox2 correlates positively with GA1 concentration and CYCA1.1 gene expression in the ovary, with the latter gene being associated with the rate of cell division in the pericarp (Mesejo et al., 2016). Notably, in Satsuma, the upregulation of CYCA1.1 following anthesis occurs after the peak expression of GA20ox2 at anthesis and precedes its second activation 10 days post-anthesis, which coincides with a renewed overexpression of GA3ox2. This temporal pattern suggests that the cell division process itself may reactivate GA biosynthesis to sustain an adequate rate of cell proliferation (Mesejo et al., 2016).

The link between cell division activation and GA is further supported by studies investigating the effects of GA₃ treatments on GA metabolism and cell division activation. In Satsuma mandarin, increased expression of the CYCA1.1 gene closely parallels an increase in endogenous GA₁ concentration following exogenous GA₃ application, leading to an increased rate of cell division. This effect is transient due to its intrinsic capacity for GA₁ biosynthesis (Mesejo et al., 2016). However, in Clementine ovaries, which lack the ability to synthesize GA₁ at anthesis, GA₃ application not only stimulates GA₁ biosynthesis but also upregulates CYCA1.1 expression, promotes cell division, and significantly enhances fruit set (up to 95%). These findings provide evidence of the relationship between GAs, cell division, and fruit set (Mesejo et al., 2016).

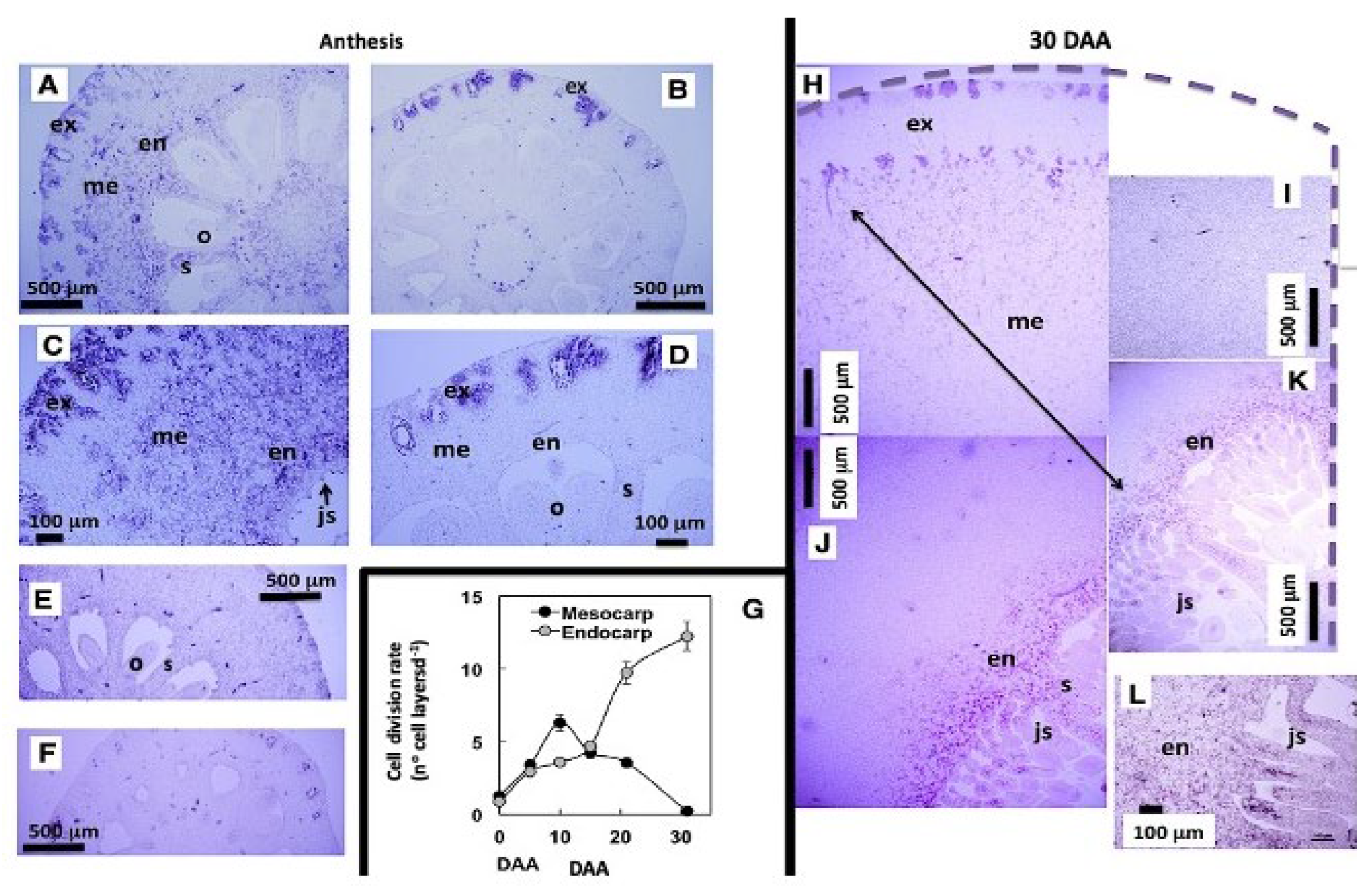

This relationship is further reinforced by the spatiotemporal correlation between the accumulation of

GA20ox2 transcripts and the temporal progression of cell division in the mesocarp and endocarp. In the ovary of the Satsuma mandarin, in situ hybridization analysis of

GA20ox2 transcripts revealed a strong signal throughout the pericarp at anthesis, with the most intense cell division occurring in the mesocarp. In contrast, the Clementine ovary exhibited weak

GA20ox2 expression, mainly in the exocarp, correlating with its lower mitotic activity. Thirty days later, in the Satsuma ovary the

GA20ox2 hybridization signal shifts and becomes restricted to the endocarp and its emerging vesicles, where cell division remains active. At this stage, mesocarp cells have ceased dividing and are instead enlarging, resulting in the absence of a detectable hybridization signal (

Figure 5; Mesejo et al., 2016). Consequently, GA₁ is identified as the active GA regulating fruit set in citrus.

Following petal abscission, the IAA content in the ovary increases sharply, reaching its peak shortly thereafter (Talón et al., 1990b). This pattern is observed in both seeded and seedless varieties, although the latter exhibit slightly higher concentrations, as demonstrated in the seeded ‘Duncan’ and seedless ‘Marsh’ grapefruit (Ali-Dinar et al., 1988). However, within seedless mandarin cultivars, no significant differences are detected regardless of their parthenocarpic ability (Talón et al., 1990b). This suggests that in these varieties, the IAA content of the ovary is not a limiting factor for fruit set and early fruit development. Conversely, in the seeded ‘Murcott’ mandarin, when pollination is experimentally prevented, IAA concentration remains at a minimal level, indicating that the substantial post-anthesis increase in IAA biosynthesis is pollination- and fertilization-dependent (Bermejo et al., 2015).

Similarly, the absence of pollination in the seeded ‘Pineapple’ orange leads to a reduction in IAA levels in both the ovule and pericarp but is also accompanied by a decline in GA precursors GA₁ and GA₂₀. However, exogenous IAA application to unpollinated ovaries upregulates GA20ox2 and GA3ox1 expression, restoring GA₁ and GA₂₀ levels, albeit exclusively in the ovules. This response is not detected in the pericarp, suggesting that the latter exhibits reduced sensitivity to IAA, at least in this variety (Bermejo et al., 2018). These findings imply that IAA likely induces GA biosynthesis within the ovules, from where GA are subsequently transported to the pericarp (Dorcey et al., 2009). Supporting this hypothesis, treatment of pollinated ovaries with tri-iodobenzoic acid (TIBA), an inhibitor of IAA transport, results in decreased GA concentrations. This indicates that when IAA translocation from egg cells—where its biosynthesis occurs—is restricted, GA synthesis in the ovary is disrupted. Additionally, GA2ox, a gene encoding an enzyme involved in GA20 and GA1 catabolism, is upregulated in unpollinated ovaries and downregulated by exogenous IAA application (Bermejo et al., 2018). Consequently, fruit set in seed-bearing (non-parthenocarpic) cultivars is contingent upon successful pollination and fertilization, which in turn enhances GA biosynthesis via upregulation of GA20ox2 and GA3ox1, while repressing GA2ox1-mediated GA degradation. These regulatory effects are driven by IAA, whose post-pollination accumulation in the ovary promotes GA₁ biosynthesis, thereby initiating the fruit developmental program (Bermejo et al., 2018). Following petal abscission, IAA levels decline rapidly as the ovary develops, reaching minimal levels at the onset of physiological fruitlet abscission. This reduction coincides with increased conjugated IAA and enhanced auxin oxidase activity, which facilitates IAA catabolism (Talón et al., 1990b).

In both seeded- and seedless-bearing cultivars exhibiting high parthenocarpic ability, GA₁ levels increase in the ovary immediately after anthesis, while abscisic acid (ABA) concentration remains low. However, in self-incompatible cultivars with limited natural parthenocarpy, the absence of pollination results in negligible GA₁ accumulation. Instead, ABA levels transiently rise after a few days, leading to pronounced reproductive organ abscission. The failure of these cultivars to set fruit via parthenocarpy is attributed not only to the insufficient GA₁ concentration but also to their limited capacity to inactivate ABA via conjugation (Talón et al., 1990b). Exogenous GA₃ application suppresses the post-anthesis ABA surge in ovaries of low-parthenocarpy varieties and mitigates their abscission. Conversely, inhibiting GA biosynthesis with paclobutrazol in parthenocarpic varieties increases both ABA accumulation and abscission rates. Furthermore, treatment with fluridone—an inhibitor of carotenoid biosynthesis and thus ABA synthesis—delays ovary and fruitlet abscission (Zacarías et al., 1995).

In unpollinated ovaries of seed-bearing cultivars, ABA levels rise post-anthesis due to insufficient level of GA₁, ultimately resulting in complete reproductive organ abscission. Elevated ABA concentrations promote the synthesis of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), a precursor to ethylene, which serves as a key effector of abscission (Goren, 1993; Iglesias et al., 2006). In contrast, pollination and fertilization inhibit ABA accumulation in the ovary, thereby preventing its abscission (Bermejo et al., 2015).

In citrus, trans-zeatin (tZ) and 2-isopentenyl adenine (2-IP) have been identified as the predominant cytokinins in flower buds and ovaries, with zeatin riboside and isopentenyl adenosine present in lower concentrations (Hernández-Miñana et al., 1989). The activity of these cytokinins increases markedly in the ovaries at anthesis, peaking around petal abscission, followed by a sharp decline over the subsequent two weeks of development. This temporal pattern is consistent across both seeded and seedless cultivars, albeit with quantitative variations among cultivars (Hernández-Miñana and Primo-Millo, 1990). In seed-bearing cultivars, tZ and 2-IP levels are similar in pollinated and unpollinated ovaries, suggesting that the biosynthesis of these hormones is constitutive and independent of pollination or ovule fertilization (Bermejo et al., 2015).

2.4.2. Competition for Photoassimilates

Following petal abscission, a substantial number of ovaries remaining on the tree cannot fully develop into mature fruit due to limitations in carbon (C) availability, as their cumulative C demand would surpass the tree’s metabolic capacity (Guardiola et al., 1984). Consequently, the net CO₂ assimilation capacity of the leaves as a whole, particularly during critical periods of elevated C demand, is considered a key limiting factor in fruit set. In this context, the plant’s photosynthetic efficiency, and thus the availability of photoassimilates, is a primary determinant of the proportion of flowers that successfully set. The hypothesis that trees selectively retain only those fruits they can sustain, discarding those in poorer condition to receive the available nutrient, is highly suggestive and has been widely accepted. This suggests that citrus trees have an endogenous self-regulatory mechanism that modulates fruit production in accordance with their metabolic synthesis capacity (Goldschmidt and Monselise, 1977; Guardiola et al., 1984).

In citrus, once mineral and water requirements are met, competition for carbohydrate becomes the primary factor driving fruitlet abscission (Moss et al., 1972; Powell and Krezdorn, 1977; Goldschmidt and Koch, 1996). During the fruit set period, ovaries or fruitlets that fail to sustain a high growth rate due to insufficient nutrient allocation are eventually shed. Consequently, peak competition for carbohydrates coincides with the highest rates of reproductive organ abscission. However, this competition is not limited to fruits alone; vegetative development also competes for C resources (Moss et al., 1972). Studies on alternate bearing have shown that fruits accumulate substantial amounts of C at the expense of shoot development, with an inverse correlation between monthly C accumulation in fruits and shoot dry weight gain. The presence of a strong C sink, such as developing fruit, restricts C availability to other competing sinks, including growing shoots. Consequently, as the C demand of the fruit increases, vegetative growth correspondingly declines (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2015). Experiments using ¹³C labeling indicate that ¹³CO₂ uptake is influenced by fruit presence. Young shoots on fruit-bearing branches assimilate less isotope compared to those on non-fruiting branches. Moreover, within the same branch, growing fruit exhibits a higher ¹³C uptake than shoots (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2015).

This competition is partially mitigated by the ability of the ovaries to accumulate starch during floral ontogeny through a dual mechanism: (1) an autotrophic pathway, wherein source organs activate the expression of Rubisco small subunit (RbcS) genes (Hiratsuka et al., 2015; Mesejo et al., 2019), and (2) a heterotrophic pathway, involving the mobilization of stored reserves via sink organs that hydrolyze sucrose in the cytosol (Baroja-Fernández et al., 2003; Sadka et al., 2019; Agustí et al., 2024). Throughout floral development, both the energy depletion signaling system, mediated by the expression of the SnRK1 (SNF1-related kinase 1) gene, a sensor of sugar deficiency, and carbon fixation via Rubisco are activated (Mesejo et al., 2019). SnRK1 is induced under various energy-depleting stresses and plays a central role in maintaining energy homeostasis by modulating the activity of key metabolic enzymes (Hulsmans et al., 2016), as well as regulating starch and sucrose synthesis and hydrolysis in relation to ovary abscission. Consequently, starch accumulation during ovary ontogeny is critical for fruit set, facilitating the ovary-to-fruit transition independently of leaf presence and maintaining sufficient glucose levels (Mehouachi et al., 1995). This temporary glucose supply alleviates competition between the ovary and young leaves until the latter become photosynthetically active and function as source organs (Mesejo et al., 2019).

However, the limited external surface area of the ovaries suggests a low capacity for CO₂ uptake. Furthermore, at the onset of the first wave of reproductive organ abscission, many ovaries undergo a phase of intense cell division, accompanied by maximum respiratory activity per unit of tissue weight. Consequently, during this initial stage, ovary development is not solely dependent on starch accumulation but also on the supply of photoassimilates, mainly from the mature leaves of the previous year rather than from the leaves of the newly emerged spring shoots (Moss et al., 1972; Mehouachi et al., 1995). The latter, which are still developing, function as C-consuming organs with a limited capacity for photoassimilate export and compete with the ovaries for C resources derived from the previous year’s leaves, which have a reduced capacity for CO₂ assimilation and must also fulfill carbohydrate demands from other sink organs, particularly the roots (Moss et al., 1972).

Accordingly, at anthesis, the ovary marks a peak in soluble sugar concentration (glucose, fructose, and sucrose), which subsequently declines to low levels over the following two weeks. This transient increase in sugar concentration is attributed to elevated hormonal activity in the ovaries, which enhances their sink strength and promotes sucrose transport (see section “The influence of hormone levels”). Enzymes involved in sucrose metabolism, such as invertases, play a pivotal role in cleaving imported sucrose, thereby regulating C import rates into the developing fruit (Sadka et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2021). Comparative analysis of the expression of the sucrose synthase gene SUS1 and the cell wall invertase gene CWIN suggests that sugar unloading in the fruit occurs predominantly via a symplastic pathway (Agustí et al., 2024).

These results suggest that during the early stages of development, reproductive organs rely mainly on their own carbohydrate reserves. However, as development progresses, they enter into intense competition for leaf-derived photosynthates. Consequently, a deficiency of these assimilates triggers the abscission of a significant proportion of ovaries and smaller fruitlets within the first month after petal fall (Agustí et al., 1982b; see section “Abscission of developing fruitlets”).

After that, during the second wave of reproductive organ abscission, termed physiological fruitlet abscission, there is a marked decline in the number of fruitlets retained on the tree relative to the initial ovary count. The remaining fruits enter a phase of accelerated growth, resulting in an increased carbohydrate demand per fruit compared to that of the initial ovaries. This process occurs coinciding with peak competition for carbohydrate resources and thus, when flowering is abundant, starch concentrations in mature leaves decline during the fruit set period, reaching a minimum towards the end of the fruit drop period. The mobilization of carbohydrate reserves stored in the leaves to support the developing fruitlets suggests that the carbohydrate demand during physiological fruitlet abscission exceeds the supply capacity of photosynthesis. Concurrently, young leaves emerging during the spring flush transition from acting as carbohydrate sinks to becoming sources of photoassimilates. This shift is evidenced by the efflux of ¹⁴C-labeled compounds and associated metabolic changes in the leaves (Powell and Krezdorn, 1977). Therefore, by the onset of fruit drop, newly developed leaves are sufficiently mature to supply photoassimilates to other organs. This function is particularly relevant in mixed inflorescences, where young leaves directly support the fruitlets they bear. Consequently, fruitlets on mixed shoots are at an advantage for fruit set compared to those on leafless inflorescences, which rely solely on assimilates from older leaves (Lenz, 1966; Moss et al., 1972; Zucconi et al., 1978). The second wave of abscission thus represents a fine-tuning mechanism by which the tree adjusts fruit load to match its CO₂ assimilation potential. Hence, the availability of photoassimilates emerges as the primary limiting factor for fruit set during this period.

Multiple lines of evidence indirectly indicate that carbohydrates play a crucial role in fruit set: 1) Defoliation leads to ovary and small fruitlet abscission, whereas plants with a high leaf-to-flower ratio achieve significantly higher fruit set percentages, provided other factors remain constant (Ruan, 1993; Gómez-Cadenas et al., 2000). Total defoliation, whether at anthesis or during the onset of physiological fruitlet abscission, results in the abscission of 100% of developing fruitlets. In contrast, removing 50% of the leaves leads to an intermediate level of abscission between fully defoliated and intact trees (Mehouachi et al., 1995). Furthermore, in fruits from defoliated branches, the expression of SnRK1 and RbcS genes is upregulated compared to fruits from non-defoliated branches and is activated earlier, suggesting that these genes detect the absence of carbohydrate sources and respond by mobilizing stored carbohydrates and enhancing their own biosynthesis (Mesejo et al., 2019). 2) The presence of young leaves in close proximity to the ovary increases the likelihood of fruit set. Ovaries on inflorescences with young leaves (mixed shoots) exhibit a higher fruit set rate than those on leafless inflorescences (flower clusters) (Zucconi et al., 1978); moreover, the highest fruit set rates are observed in solitary ovaries located at the tip of a newly developed shoot, emphasising the ovary’s dependence on nearby young leaves for successful development (Moss et al., 1972). 3) The application of photosynthesis inhibitors during the fruit set period induces substantial fruitlet drop (Mesejo et al., 2012; Agustí et al., 2024). 4) Reducing photosynthetic activity through tree shading significantly decreases fruit set rates and overall yield (Berüter and Droz, 1991). 5) Continuous injection of sucrose solution into the trunk starting 30 days before anthesis enhances ovary retention (Iglesias et al., 2003). 6) Girdling branches or scoring trunks or branches at petal fall markedly improves fruit set (Mesejo et al., 2022). Scoring disrupts the phloem, reducing sucrose translocation to the roots, which act as strong sinks for photoassimilates (Wallerstein et al., 1974). Additionally, girdling has been shown to increase photosynthetic activity in leaves adjacent to the developing fruit (Rivas et al., 2007) (see section “Ringing branches”).

Lastly, deficiencies in certain mineral elements, particularly nitrogen (Lenz, 1966; Legaz et al., 1995), as well as phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and iron (González-Ferrer et al., 1984; García-Marí et al., 1980), significantly reduce the plant’s photosynthetic capacity and negatively impact fruit set.

2.4.3. Hormone-Photoassimilate Interactions

Endogenous hormones and available carbohydrates in the ovaries and developing fruitlets interact during fruit set. It has been proposed that the gradient of photoassimilate concentration between the source (leaf) and the sink (fruit) may be the primary regulator of transport and partitioning patterns, while hormones act as modulators of multiple rate-limiting steps in this process (Brenner and Cheikh, 1995). In this context, studies using ¹⁴C-labeled carbohydrates have demonstrated that hormone application enhances carbohydrate mobilization towards the ovaries (Kriedemann, 1970; Mauk et al., 1986). Moreover, GA3 application has been shown to increase the photosynthetic rate by stimulating Rubisco activity (Yuan and Xu, 2001) and facilitating carbon allocation to the ovary (Jahnke et al., 1989), reinforcing the necessity of a source-sink carbohydrate concentration gradient. This mechanism may partially explain why fruit set requires relatively high levels of GA₁ in the ovary, as observed in seeded varieties that have undergone successful pollination and fertilization, or in cultivars with high parthenocarpic ability.

On the other hand, restricting carbohydrate supply to the ovaries and developing fruitlets during the fruit set period enhances ethylene release, which ultimately drives the abscission of reproductive organs. This process occurs in both the ZA-A and ZA-C abscission zones without distinction (Gómez-Cadenas et al., 2000) (see section “Abscission of Developing Fruitlets”). Evidence supporting this effect includes the observation that defoliation reduces sucrose and starch concentrations in developing fruitlets, leading to increased abscission rates correlated with elevated levels of ABA and ACC (

Table 2). The sequence of events is as follows: a reduction in sucrose availability from the leaves increases ABA concentrations, which in turn induces ACC synthesis and subsequent ethylene release, which is the ultimate effector of abscission. Experimental studies using exogenous applications of these compounds to developing fruitlets successfully replicate and confirm this process. Under normal conditions, competition for available photoassimilates results in many ovaries and fruitlets receiving insufficient carbohydrate supply, triggering a hormonal cascade that leads to widespread abscission (Agustí et al., 1982b). In this self-regulatory mechanism, sucrose, ABA, ACC, and ethylene act as key components, orchestrating fruit retention in accordance with the plant’s resource availability (Gómez-Cadenas et al., 2000).

In summary, the evidence indicates that following petal fall, a high endogenous concentration of GA₁ in the ovary, along with an adequate supply of photoassimilates, primarily sucrose, is essential to initiate and sustain fruit growth. A deficiency in either of these compounds leads to fruitlet abscission during the fruit set phase.

2.5. Factors Affecting Fruit Set

Adverse environmental conditions, including elevated temperatures, water stress, and shading, disrupt CO₂ assimilation and/or respiration, leading to energy deprivation (Baena-González and Sheen, 2008) and triggering organ abscission. Other factors such as rootstock, mineral elements and flowering intensity also affect fruit set.

2.5.1. Temperature

Elevated temperatures (>38ºC) during the fruit set period, particularly when accompanied by dry winds and low soil mositure, significantly enhance fruitlet abscission rates (Koo, 1967; Moss, 1973). A sudden rise in temperature, especially abrupt fluctuations, coupled with low atmospheric humidity, intensifies leaf transpiration, leading to water loss, and consequently a transient decline in leaf water potential occurs, inducing temporary stomatal closure. The resulting decrease in stomatal conductance restricts gas exchange, ultimately reducing net CO₂ assimilation (Syvertsen et al., 2003), the process being species dependent (Guo et al., 2006). This limitation exacerbates fruitlet abscission rates during periods of high photoassimilate demand by developing fruit, as previously noted. Moderate tree shading significantly enhances fruit set by lowering leaf temperature and increasing stomatal conductance (Borges et al., 2009).

2.5.2. Water Deficit

A pronounced soil water deficit during the fruit set period significantly increases fruitlet abscission. Water scarcity induces the expression of ABA biosynthetic genes, such as 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (CcNCED3), leading to elevated ABA levels (Agustí et al., 2007b; Gómez-Cadenas et al., 1996). This, in turn, stimulates ACC synthase activity in roots (Tudela and Primo-Millo, 1992) and promotes ACC biosynthesis and accumulation. The latter is further facilitated by xylem flow blockage due to water stress (Gómez-Cadenas et al., 1996). Upon tree rehydration, xylem flow is restored, allowing ACC to be transported via the xylem stream from the roots to the leaves and fruitlets, where it is metabolized into ethylene, ultimately triggering leaf and fruitlet abscission. ABA accumulated in water-stressed roots can also be actively transported through the xylem to the leaves and fruits upon rehydration (Gómez-Cadenas et al., 1996; Tudela and Primo-Millo, 1992). Once in the leaves, ABA induces stomatal closure, thereby reducing transpirational water loss. This response also limits net CO₂ assimilation, consequently decreasing the supply of photoassimilates from the leaves to the developing fruitlets, which further promotes abscission.

Therefore, maintaining soil moisture above a critical threshold through appropriate irrigation frequency and water volume favours fruit set. In this context, high-frequency drip irrigation provides significant advantages, as it enables the maintenance of a consistently elevated moisture level in localized soil areas where the root system is concentrated.

2.5.3. Rootstock

Numerous studies have demonstrated substantial rootstock effects on fruit yield. These effects are typically the result of complex interactions among multiple factors, most notably the degree of rootstock adaptation to specific environmental and edaphic conditions. A strong positive correlation between tree size and yield per tree has also been consistently reported, underscoring the need to account for tree vigor when evaluating yield potential on a per-area basis. Poncirus trifoliata, Carrizo citrange (C. sinensis × P. trifoliata), Rough lemon (C. jambhiri), FA-5 (C. reshni × P. trifoliata), and C. macrophylla bear a good crop of fruit (Bowman and Joubert, 2020).

Tree spacing also influences fruit yield. In general, for oranges and mandarins, yield per hectare increases with higher tree density, although yield per tree tends to decrease or remain unaffected (Haque and Sakimin, 2022).Dwarfing rootstocks play a pivotal role in enabling high-density orchard systems

2.5.4. Nitrogen

In addition to carbohydrates, the ovary and developing fruitlet require nitrogen (N) for protein synthesis from anthesis onwards. Under N-deficient conditions, when the availability of N to the fruitlet is inadequate, a pronounced fruitlet abscission occurs, leading to a significant reduction in yield. Consequently, enhancing N fertilization up to the optimal foliar N concentration results in an increased fruit set rate (Embleton et al., 1973). Specifically, the late winter application of low-biuret urea has been shown to enhance fruit setting potential, an effect attributed to an increase in the synthesis of polyamines, such as putrescine, spermidine, and spermine (Lovatt et al., 1992).

During the ovary and fruitlet drop period, N concentrations in mature leaves reach their lowest levels, a condition that is subsequently reversed by the end of spring (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2015). This seasonal N deficiency is primarily attributed to the export of N reserves from the old leaves to support the high N demand associated with spring bud break, flowering, and fruitlet development (Legaz et al., 1995; Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2011). The significant role of stored N during the early stages of fruit set is a consequence of the limited N uptake by the roots in late winter and early spring, which results from reduced root growth and low soil temperatures (Mooney and Richardson, 1992). However, towards the end of spring, root N uptake increases markedly, effectively compensating for the earlier seasonal N deficit (Legaz et al., 1981; Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2011). In this context, young leaves play a crucial role in N redistribution (Legaz et al., 1982), as they initially assimilate the majority of the absorbed N, which is then retranslocated to support fruitlet development (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2011). These processes suggest that a N deficiency during the post-flowering period, when ovary development is accelerated, can trigger fruit drop (Agustí and Primo-Millo, 2020). Moreover, N deficiency impairs N uptake and decreases N concentrations in leaves, stems, and roots, disrupting nutrient balance. This disruption negatively affects thylakoid structure, reducing levels of photosynthetic pigments and impairing photosynthetic electron transport, thereby decreasing CO2 assimilation, photosynthesis, and fruit set (Huang et al., 2021).

During the first half of spring, N uptake is primarily directed towards the young leaves, with a secondary allocation to the ovaries (Akao et al., 1978). However, no competitive interaction has been observed between the N demands of the ovaries and shoot growth. In the fruit, N uptake increases until June, reaching a peak, and subsequently declines to very low levels, remaining relatively stable until ripening. Despite the low N utilization by the fruit during this period, shoot growth in summer and autumn is almost entirely suppressed, suggesting that N competition is not a critical factor limiting vegetative development (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2015). In alternate bearing studies, trees supplemented with 15N demonstrated no significant differences in N enrichment between young shoots and fruit in ON and OFF trees, indicating that the presence of fruit does not affect the N availability for young shoots (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2015). Moreover, the temporal evolution of N content (total N and protein N) in mature leaves and shoot bark did not support the hypothesis that fruit reduces the availability of reserve N for growing shoots. In fact, from late winter to early spring, N concentrations in mature leaves and shoot bark gradually decreased, which primarily reflected N consumption associated with spring sprouting, flowering, and freshly fruit set (Legaz et al., 1995). On the other hand, leaf N levels were consistently lower in OFF trees compared to ON trees, suggesting that vegetative growth represents a more substantial sink for N than reproductive organs, as evidenced by the higher N concentrations in young shoots compared to fruitlets (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2015). Finally, in the shoot bark of OFF trees, the minimum N concentration was observed in April (NH), coinciding with peak N demand by the shoots, whereas in ON trees, this minimum occurred in June (NH), coinciding with the highest N demand by fruitlets. This temporal mismatch further supports the notion that new vegetative and reproductive organs do not compete for N reserves (Martínez-Alcántara et al., 2015).

2.5.5. Mineral Deficiencies

Mineral nutrient deficiencies generally reduce fruit set, mainly by disrupting the photosynthetic process (Huang et al., 2021). Comparative analyses of persisting and abscising fruitlets suggest that mineral nutrient availability is closely related to abscission rate, particularly under conditions of high competition (Sanz et al., 1987; Guardiola et al., 1984). In terms of crop load, treatments to correct these deficiencies have proven highly effective when applied during the petal-fall period (Agustí and Primo-Millo, 2020).

In ‘Navelate’ sweet orange, a cultivar characterized by low parthenocarpic ability (Agustí et al., 1982a), the retranslocation rate of mineral elements is particularly low (González-Ferrer et al., 1984). This is especially evident for potassium, which shows minimal accumulation in fruitlets undergoing physiological abscission (García-Marí et al., 1980). Although the application of potassium nitrate during the spring flush promotes initial fruit set, this effect is transient and does not significantly impact final yield, primarily due to the inherently high rate of natural fruitlet abscission characteristic of this variety. This finding underscores the sensitivity of the fruit set process to deficiencies in specific mineral nutrients (Ogaki et al., 1966).

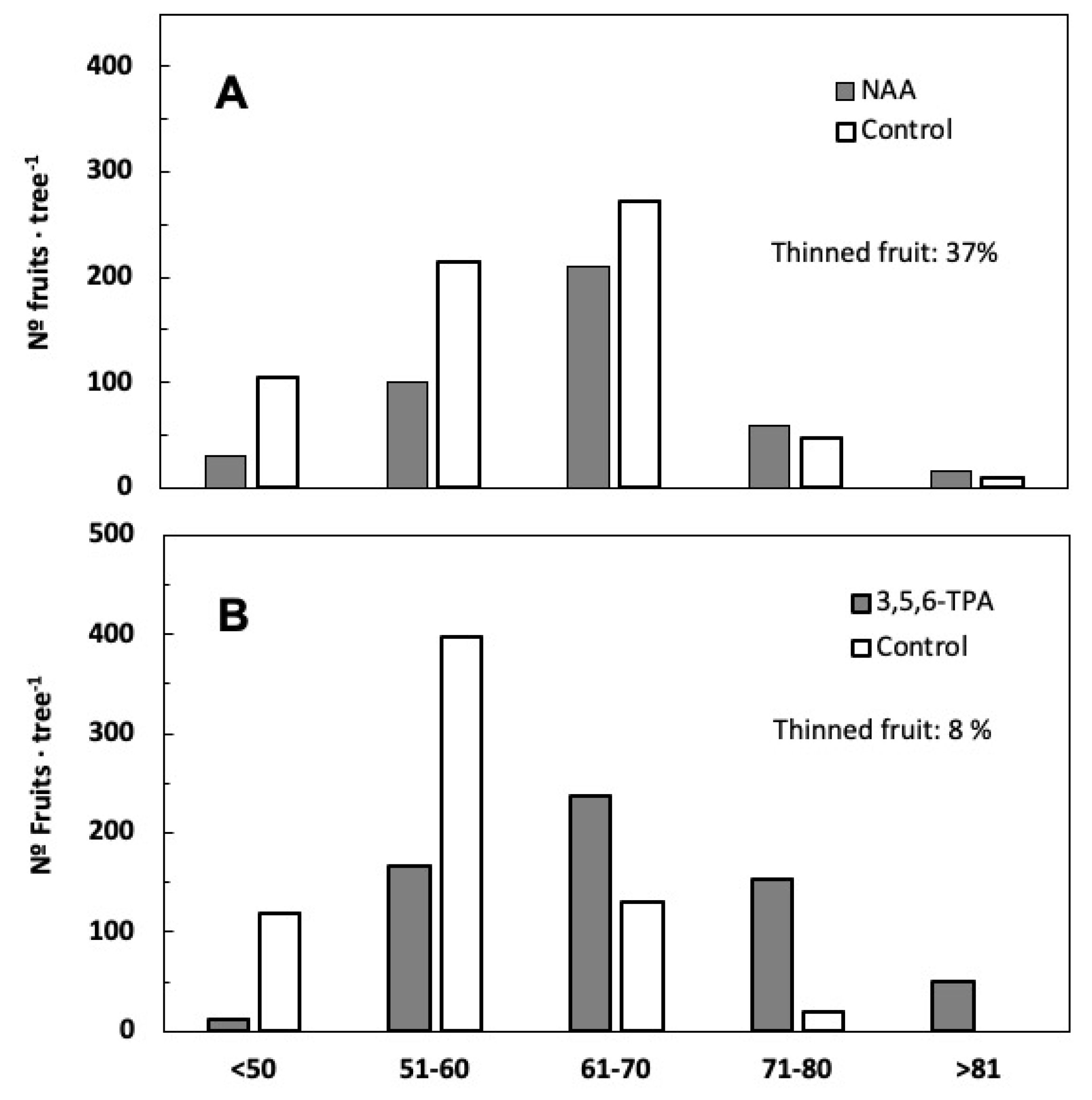

2.5.6. Flowering Intensity

The percentage of flowers that set fruit decreases as flowering intensity increases (Goldschmidt and Monselise, 1977; Agustí et al., 1982b). Across a broad range of flowering densities, the final yield remains independent of the total number of flowers produced. Consequently, when the same number of fruits is harvested, a higher flower count results in a lower fruit set percentage. When flowering is so limited that it constrains the potential yield, the fruit set percentage is typically high, even if the absolute number of harvested fruits is lower than average. This ratio tends to decline as normal flowering levels are reached (Guardiola et al., 1984). However, excessive flowering can lead to a reduction in yield due to the overconsumption of nutrients by developing reproductive structures, intensifying competition and resulting in extensive abscission (Zucconi et al., 1978). Additionally, in cases of extreme flowering, most inflorescences lack leaves, further contributing to a markedly low fruit set percentage (García-Luis et al., 1986) (

Figure 5).

In these cases, the abscission of reproductive structures—including buds, flowers, and ovaries—is predominantly advanced to the initial fruit set phase. Conversely, under low flowering conditions, reproductive organs are mainly shed as developing fruitlets, during the second wave of abscission (Agustí et al., 1982b) (see section “Abscission of developing fruitlets”).

Gibberellic acid (GA₃), at concentrations ranging from 25 to 100 mg L⁻¹, reduces flowering by 45–75% when applied during the floral bud inductive period (Monselise and Halevy, 1964) or at the onset of bud differentiation (Guardiola et al., 1982; García-Luis et al., 1986). This effect has led to its widespread use in mitigating the adverse consequences of excessive flowering on fruit set (El-Otmani et al.; 2000; Agustí et al., 2022). GA₃ has demonstrated efficacy in sweet oranges, Satsuma and Clementine mandarins, as well as in hybrid cultivars.

The molecular mechanism underlying the GA₃-induced reduction in flowering has been linked to the repression of the genes CiFT3 in the leaf and CsAP1, CsAP2, CcPI, and CcSEP3 in the bud (Muñoz-Fambuena et al., 2012; Goldberg-Moeller et al., 2013; Tang and Lovatt, 2019), thereby explaining its role in disrupting flower induction, differentiation, and organogenesis.

Notably, this reduction in flowering can also enhance the effectiveness of specific techniques aimed at increasing fruit set (Agustí et al., 1982a, 2020) (see section “Fruit setting treatments”).

2.5.7. Type of Inflorescence

The likelihood of ovary set is largely influenced by the type of shoot on which it develops and the number of young leaves supporting its growth (Moss et al., 1972; Agustí et al., 2022), as these factors determine the accessibility of nutrients. Consequently, ovaries from single-flowered leafy shoots have the highest setting rate, followed by those from axillary flowers in mixed inflorescences. In contrast, nearly all ovaries from leafless inflorescences, whether bearing one or multiple flowers, undergo abscission (Agustí and Primo-Millo, 2020).

Furthermore, ovaries from inflorescences formed on vigorous, erect shoots set at lower rates than those on more horizontally oriented shoots. This phenomenon has been attributed to the slower phloem transport rate in horizontal shoots, which favours setting at the expense of vegetative growth (Agustí and Primo-Millo, 2020).

2.6. Fruit Setting Treatments

2.6.1. Application of Gibberellic Acid

In several citrus species and cultivars, the application of GA₃ enhances fruit set (Moss, 1972). Thus, when applied to small branches, GA₃ significantly increases fruit set in the associated ovaries, although with variable efficacy. For instance, Soost and Burnett (1961) reported only a 10% increase in fruit set in Clementine mandarins following the application of GA₃ (potassium gibberellate) at concentrations ranging from 100 to 500 mg L-1. In contrast, García-Martínez and García-Papí (1979) observed a 90% increase with applications at 50 mg L-1, at which the response plateaued. This discrepancy has been attributed to a potential phytotoxic effect induced by the higher concentrations used in the former study.

Additionally, several authors have demonstrated that localized application of GA₃ to ovaries and leaves promotes fruit set in mandarins (Krezdorn, 1969; Feinstein et al., 1975; García-Papí and García-Martínez, 1984a), hybrids (Krezdorn, 1969), and oranges (Krezdorn, 1969; Moss, 1972; Hield et al., 1958; Krezdorn and Cohen, 1962). The efficacy of GA₃ treatment varies depending on the concentration applied and the timing of application.

However, applying GA₃ to the entire tree immediately after anthesis does not enhance fruit set at the same rate, resulting in significantly lower fruit set. This suggests that selective treatment of localized canopy areas increases the competitiveness of treated ovaries compared to untreated ones, thereby promoting a higher fruit set rate. Nevertheless, post-flowering application of GA₃ to the whole tree has been demonstrated as an effective strategy for improving fruit yield in mandarins (Coggins et al., 1966; Rivero et al., 1969; Damigella et al., 1970; Blondel, 1977) and hybrids (Brosh and Monselise, 1977). In contrast, results in oranges have been largely ineffective (Hield et al., 1965; Krezdorn, 1969; Moss, 1972), although some exceptions have been reported (Agustí et al., 1982a; El-Otmani et al., 2000).

In the Mediterranean Basin, GA₃ at concentrations ranging from 5 to 25 mg L⁻¹ is employed to enhance fruit set in self-incompatible cultivars with low parthenocarpic ability, such as certain Clementine varieties. The optimal application timing is immediately after petal fall, as indicated by Moss (1972). However, due to the asynchronous nature of citrus flowering, it is practically recommended when approximately 80% of flowers have shed their petals (Agustí et al., 2020).

The often-underestimated technical aspects of application play a crucial role in influencing outcomes. Specifically, factors such as pH, surfactant type, relative humidity, temperature, and wind significantly affect GA₃ uptake, with variations ranging from 2.2% to 28% of the applied quantity (Greenberg and Goldschmidt, 1988; Henning and Coggins, 1988).

When applied to the entire tree, GA₃ delays the abscission of reproductive organs by increasing the proportion that progress to the fruit development stage. However, this effect becomes significant only in trees with moderate flowering intensity, while trees with abundant flowering do not exhibit a comparable response (Agustí et al., 1982a). This suggests that the aforementioned interactions between carbohydrates and hormones influence not only endogenous hormone activity but also the response to exogenously applied hormones.

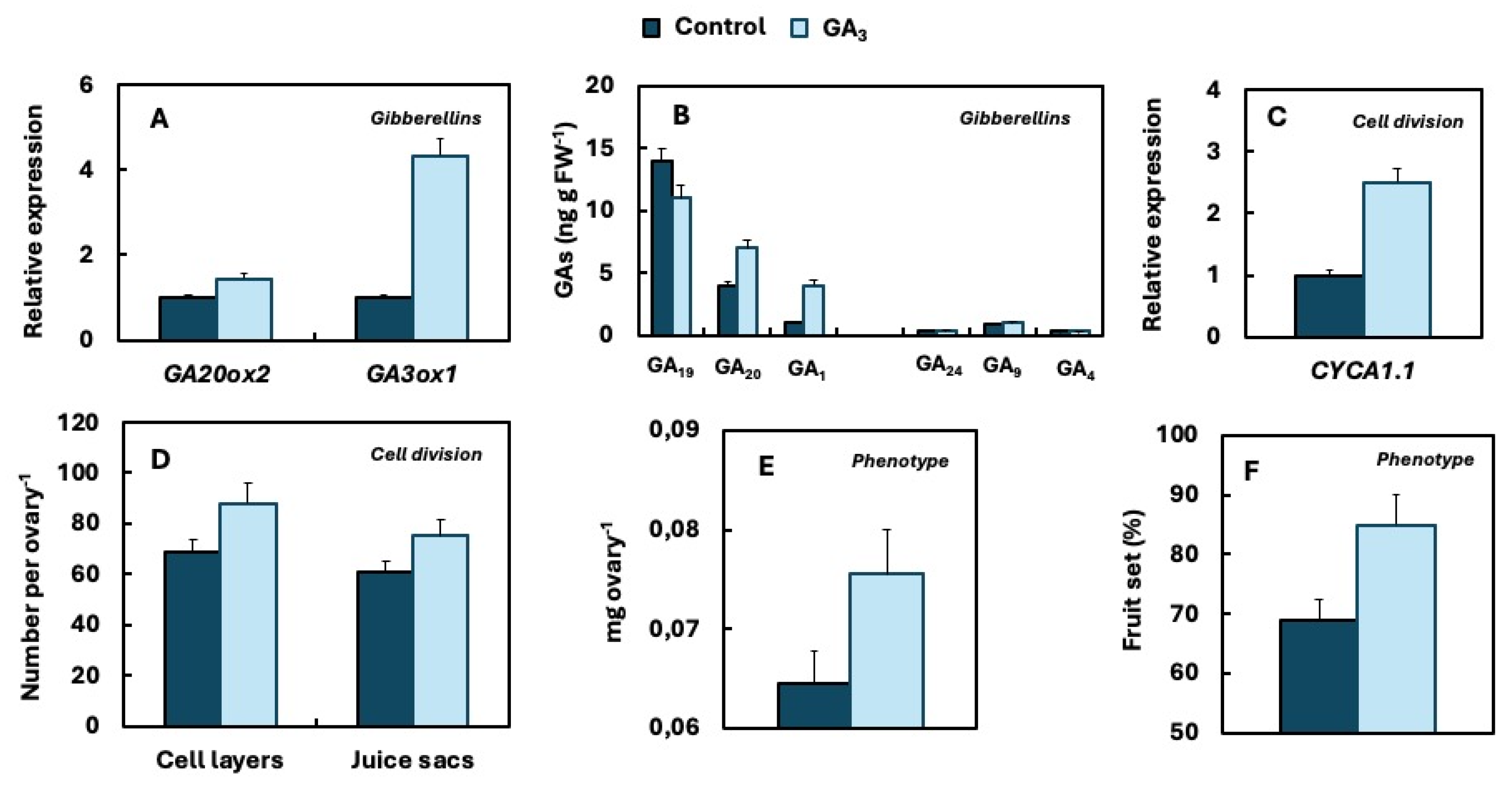

The mechanism by which GA₃ enhances fruit set was investigated by applying it to individual flowers at anthesis. GA₃ treatment upregulates the expression of

GA20ox2 and

GA3ox1 in the ovary, leading to an increase concentration of GA₂₀ and GA₁. This, in turn, induces the expression of

CcCYCA1.1, thereby enhancing the rate of cell division, which promotes ovary growth and ultimately facilitates fruit set (Mesejo et al., 2016). A summary of this process is provided in

Figure 6.

The conclusion derived from the combined analysis of endogenous GA content data and the results from exogenous GA

3 applications is that the fruit set process, particularly during its initial stages, necessitates a high concentration of GA in the ovary. This can be sourced from endogenous biosynthesis or compensated by exogenous application. However, in certain cultivars, despite an increase in the expression of

CcGA3ox2 and even

CcCYCA1.1 during anthesis, the relative expression remains low. This results in a reduced sink capacity of the ovary and an insufficient growth rate, which impedes successful fruit set. Generally, these cultivars require exogenous GA

3 application to achieve optimal fruit set. The variability in responses observed with foliar GA

3 applications across different cultivars suggests that the effectiveness of the treatment is influenced by the endogenous GA

1 concentration in the ovaries of each cultivar. Other factors, such as the availability of photoassimilates, competition for these resources, and specific crop management practices (e.g., irrigation, fertilization, pruning, striping, etc.), may also modulate the response to GA

3 treatments. In trials conducted under the climatic conditions of the Mediterranean Basin, the response to GA

3 application is not consistent across all cultivars (Talón et al., 1999; Agustí et al., 2020;

Table 3).

In addition to gibberellic acid, several lesser-known plant hormones have recently begun to be tested. For instance, salicilic acid applied at 10μM concentration, has shown effective in reducing fruitlet abscission and improving fruit yield of ‘Kinnow’ mandarin (C. reticulata) (Ashraf et al., 2012). Likewise, strigolactone GR24 at 200 μmol L-1 increased fruit setting of ‘Hamlin’ sweet orange (C. sinensis), by efficient partitioning of photoassimilates facilitating the development of young fruits (Zheng et al., 2018), and also epibrasinolide, a form of brassinosteroid, at 0.04 – 0.06 mg L-1, increased fruit setting rate of pummelo (C. grandis) (Wang et al., 2019). In contrast, in ‘Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ oranges, MeJA (>10 mM) induces mature fruit abscission, associated with ethylene production, indicating its potential for mechanical harvesting (Hartmond et al., 2000). To the best of our knowledge, studies involving this class of hormones remain scarce in citrus.